Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Issues and Sustainable Development in the Context of Education

2.2. Educational Research and Applications on Environmental Issues

2.3. Learning Dimensions of Environmental Issues

2.4. Applying Environmental Issues in General Education: A Pedagogical Reflection

- Transmission of philosophy and concepts (e.g., environmental ethics, ecological worldview);

- Instruction of knowledge and skills (e.g., scientific understanding, practical competencies);

- Facilitation of reflection and value clarification (e.g., resolving value-based environmental dilemmas).

- Environmental awareness and sensitivity

- Environmental conceptual knowledge

- Environmental ethics and values

- Skills for environmental action

- Experience with environmental engagement

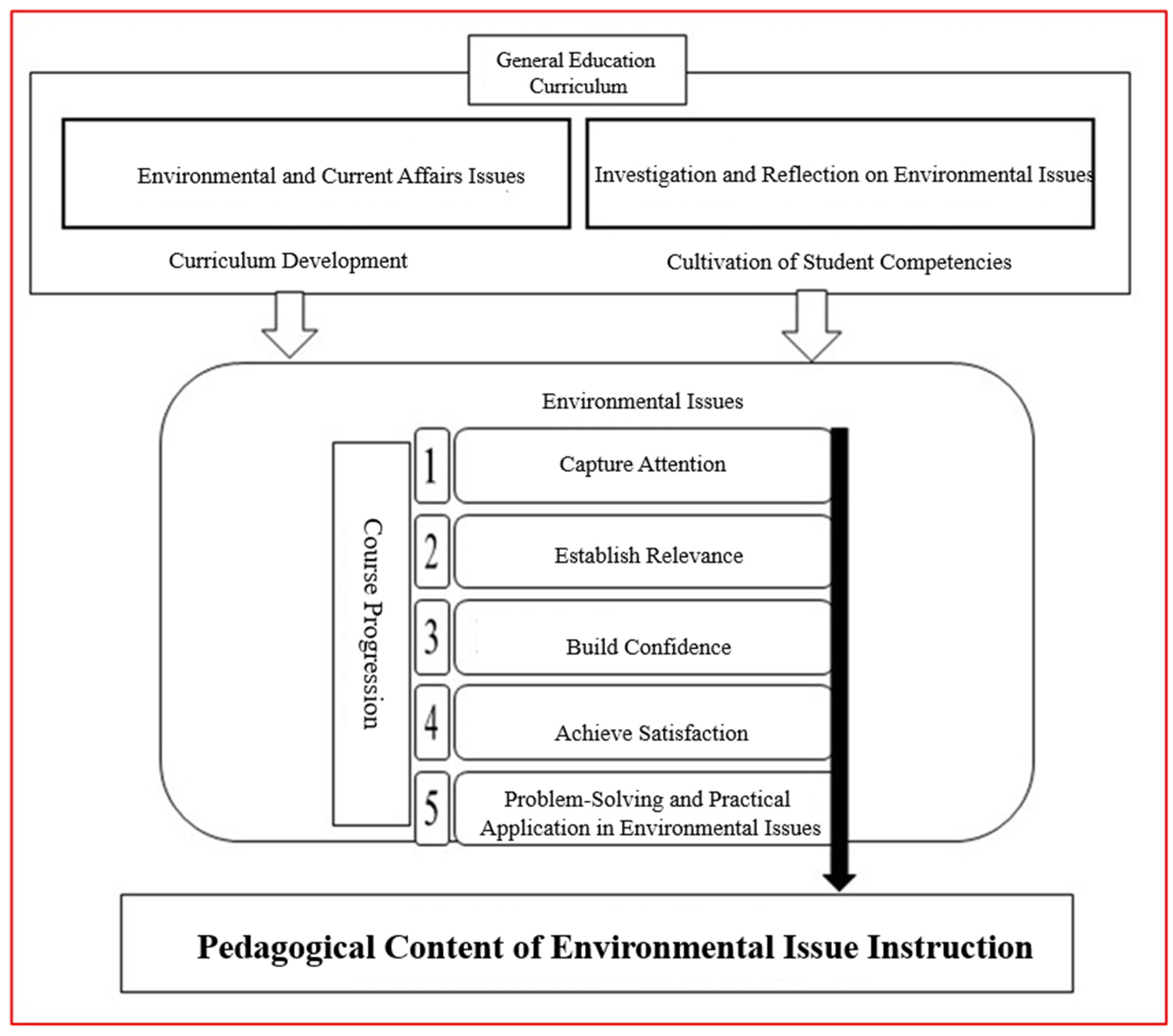

2.5. Integrating the ARCS Motivational Model into General Education on Environmental Issues

- a.

- Define: Categorize the problem, analyze student motivation, and set motivational goals. Instructional designers should begin by assessing students’ current motivational levels and then establish criteria to elevate and evaluate motivation appropriately.

- b.

- Design: Develop and select appropriate motivational strategies. This involves identifying feasible strategies and filtering them according to learner characteristics, teaching context, and instructor expertise. This is the most time-consuming and challenging step.

- c.

- Develop: Prepare teaching materials and integrate motivational strategies. This phase includes refining existing materials, developing new instructional tools, and constructing evaluation instruments.

- d.

- Evaluate: Conduct formative assessments and evaluate motivational outcomes. This final phase involves predicting, assessing, validating, and revising instructional practices as necessary.

- a.

- Stimulate awareness and sensitivity, with an emphasis on multicultural understanding;

- b.

- Deepen conceptual knowledge and encourage meaningful dialogue;

- c.

- Promote moral, ethical, and value-based reasoning;

- d.

- Develop practical skills for action;

- e.

- Provide opportunities for experiential learning.

3. Methods

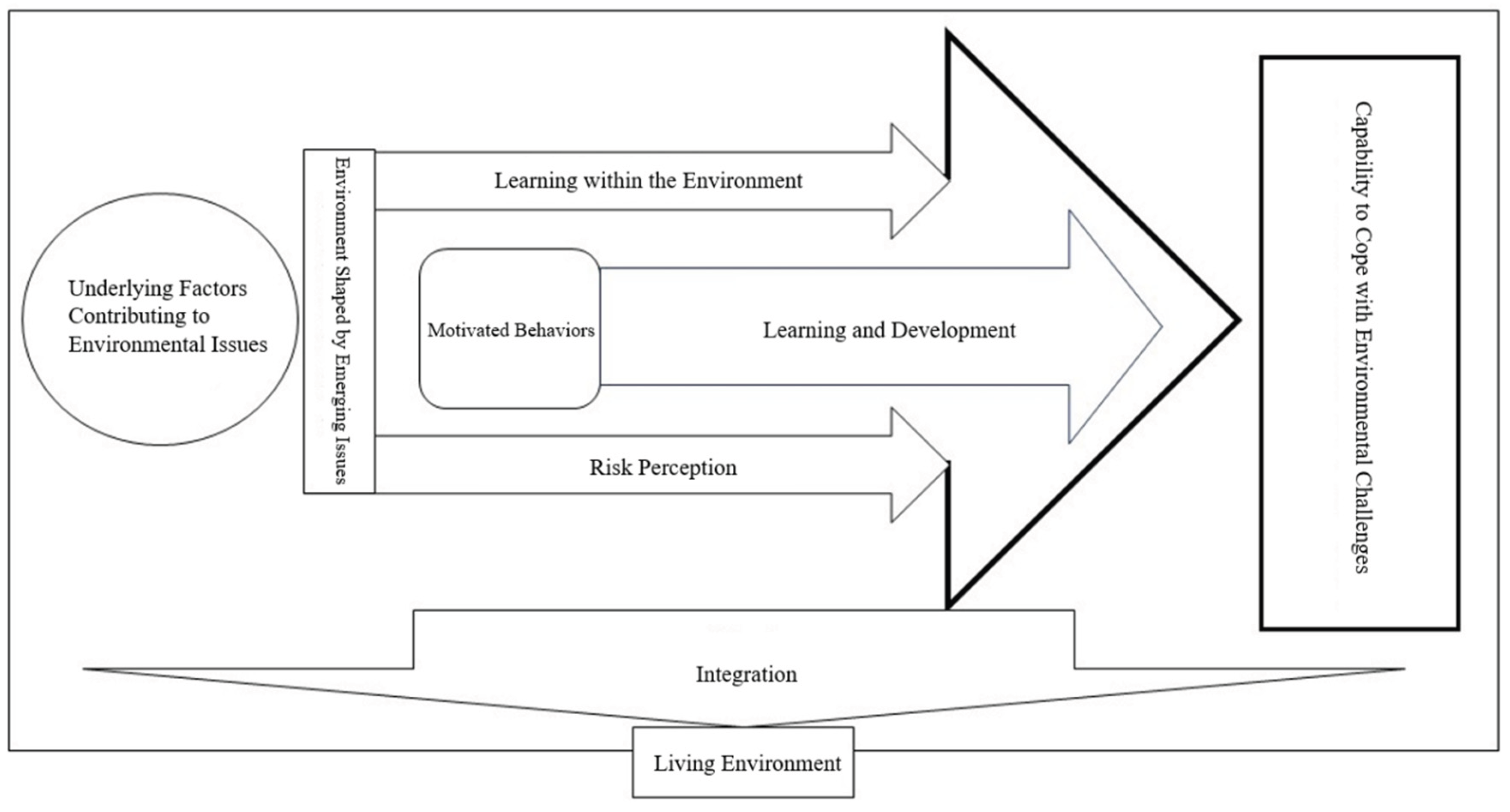

3.1. Research Framework and Questions

- To use the development of environmental issues as a thematic core, guiding learners to reflect on their personal positioning and responsibilities within the broader context of global environmental challenges.

- To engage students with real-world environmental scenarios, helping them synthesize multi-layered causal relationships and construct future-oriented solutions for environmental problems.

- To employ the ARCS motivational model to stimulate students’ interest in environmental issues and support them in planning actionable strategies and advocacy initiatives addressing these challenges.

3.2. Research Subjects and Limitations

3.3. Curriculum Intervention: Course Development on Environmental Issues Utilizing the ARCS Motivational Model

- Course Review and Reflection: Field observations and student feedback were used to continuously refine course content.

- Curriculum Planning: Literature, media, interviews, and surveys informed the integration of environmental issues into students’ everyday contexts.

- ARCS Model Application: The ARCS framework guided motivational strategies and reflective teaching practices.

- Curriculum Development: Content was adjusted to sustain student engagement and align with evolving learning needs.

- Student Engagement and Dissemination: Activities such as poster sessions and thematic discussions encouraged students to apply knowledge through advocacy and awareness-building.

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

- How were environmental issues integrated into curriculum design using the ARCS model?

- How was the ARCS model applied at each stage of curriculum development?

- How did students formulate future solutions to environmental challenges?

- What learning outcomes emerged under the ARCS model?

- Was student motivation to engage with environmental issues enhanced?

4. Results

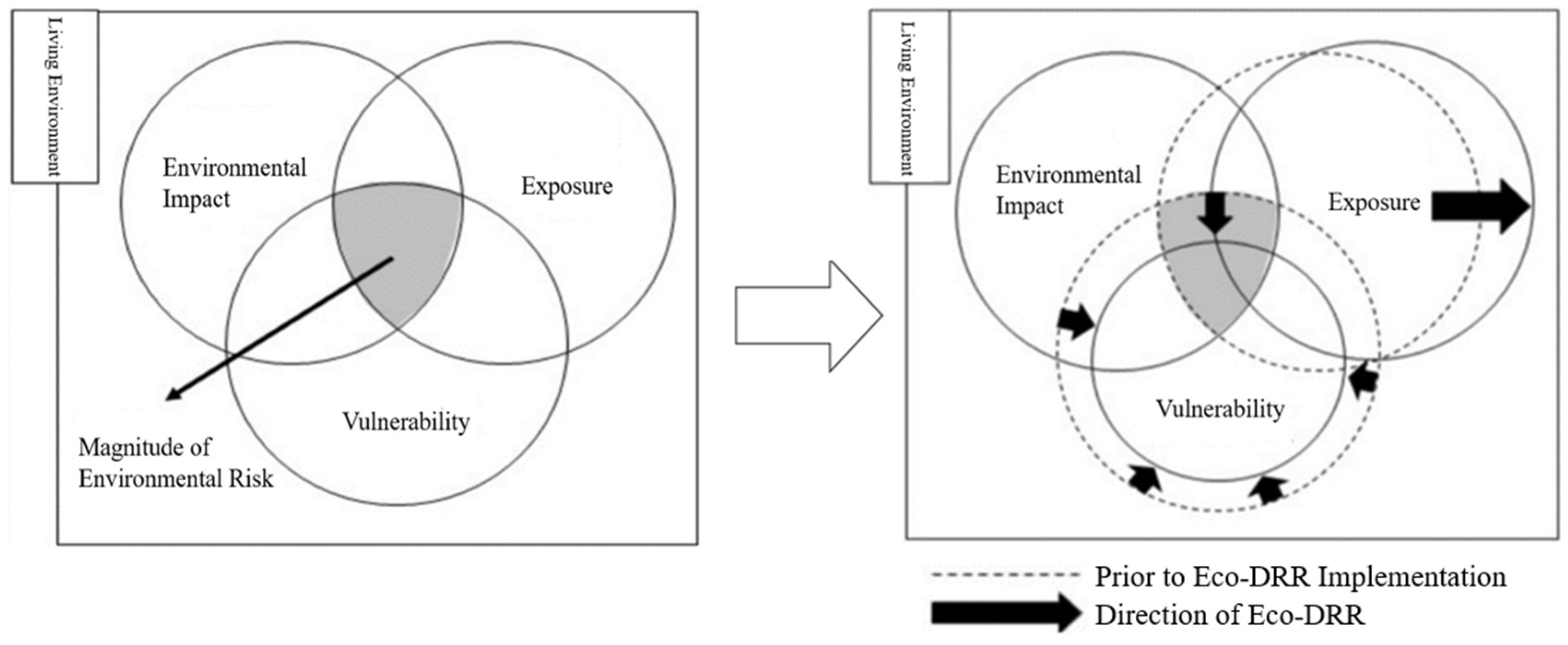

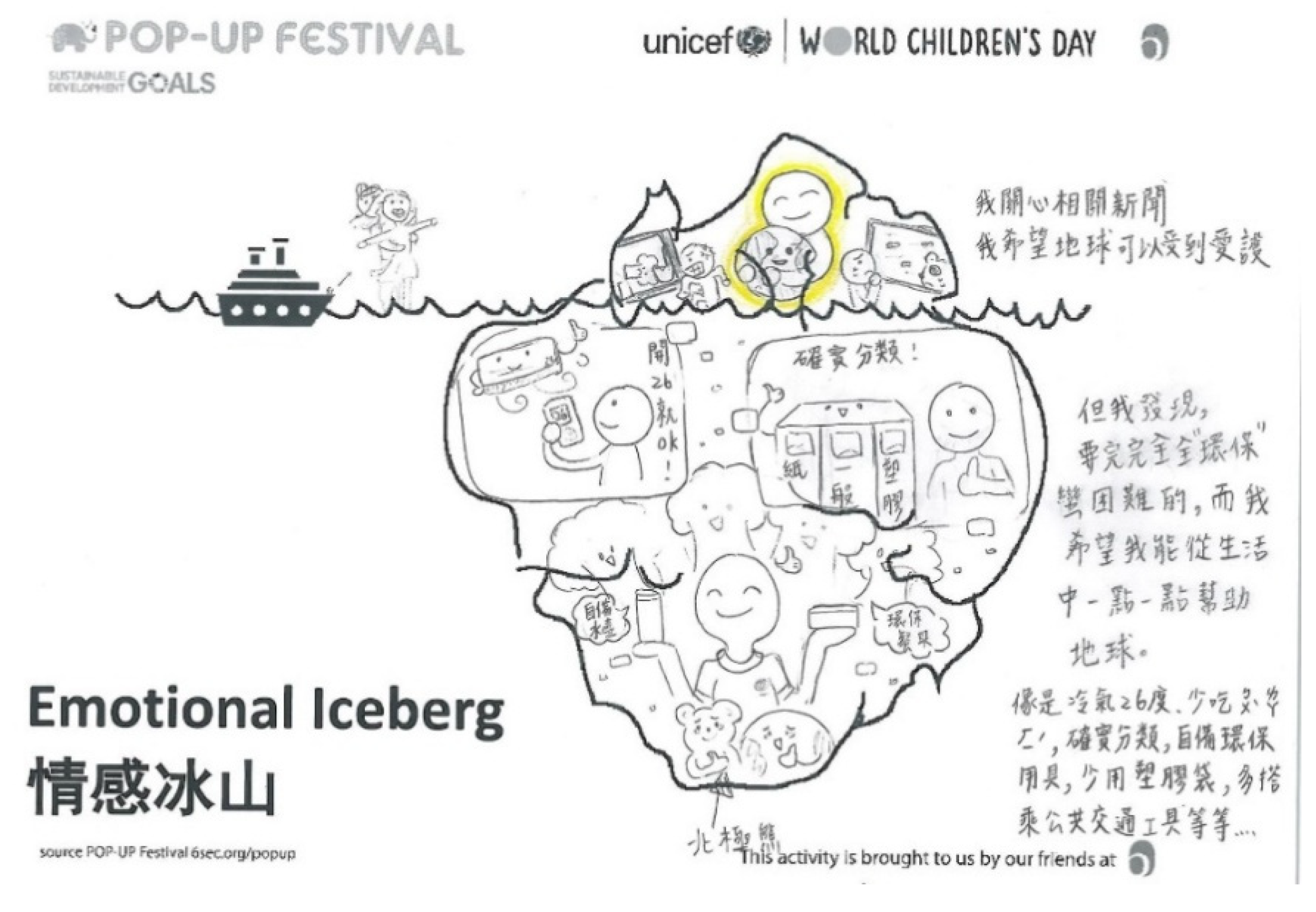

4.1. Environmental Perspectives in Environmental Issue-Based Education

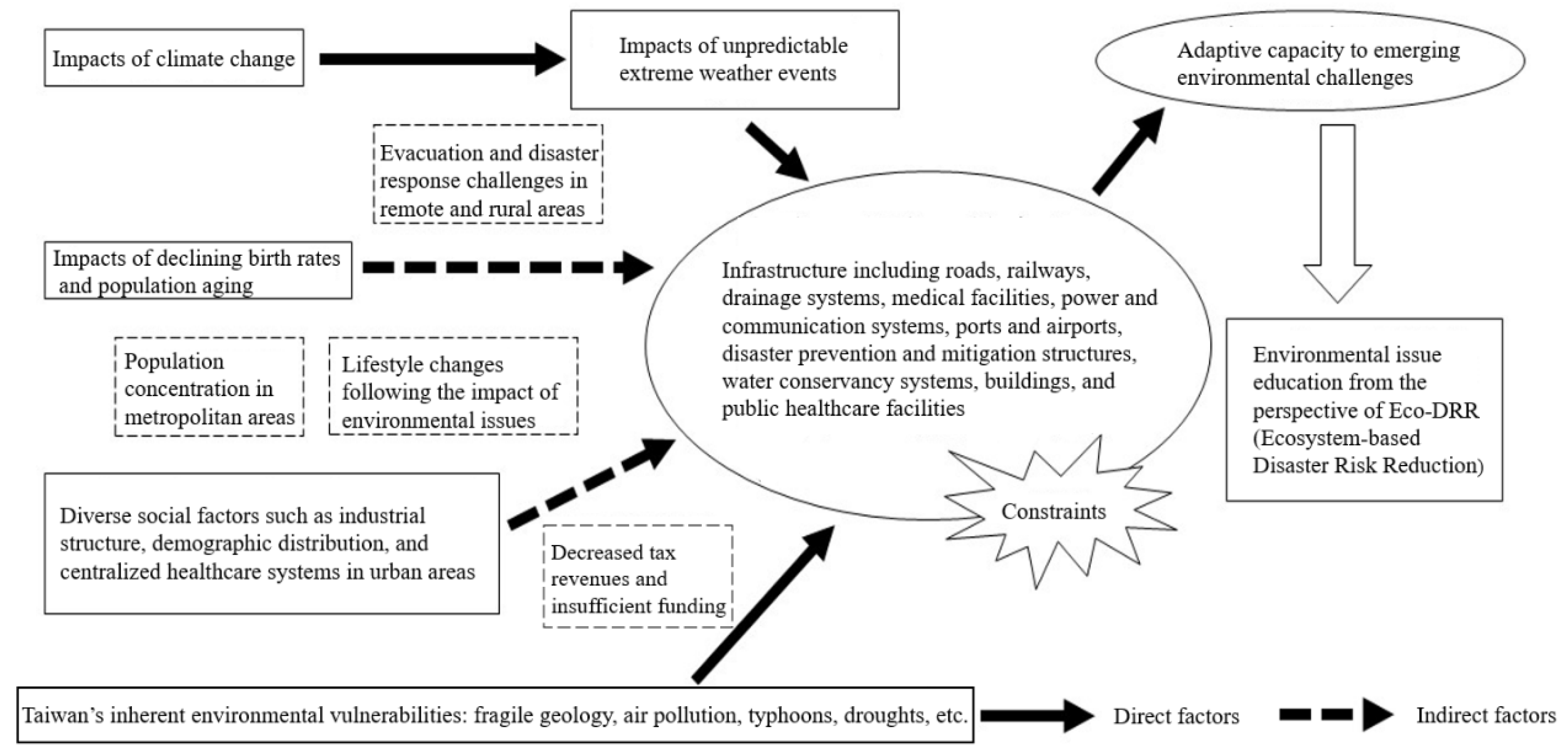

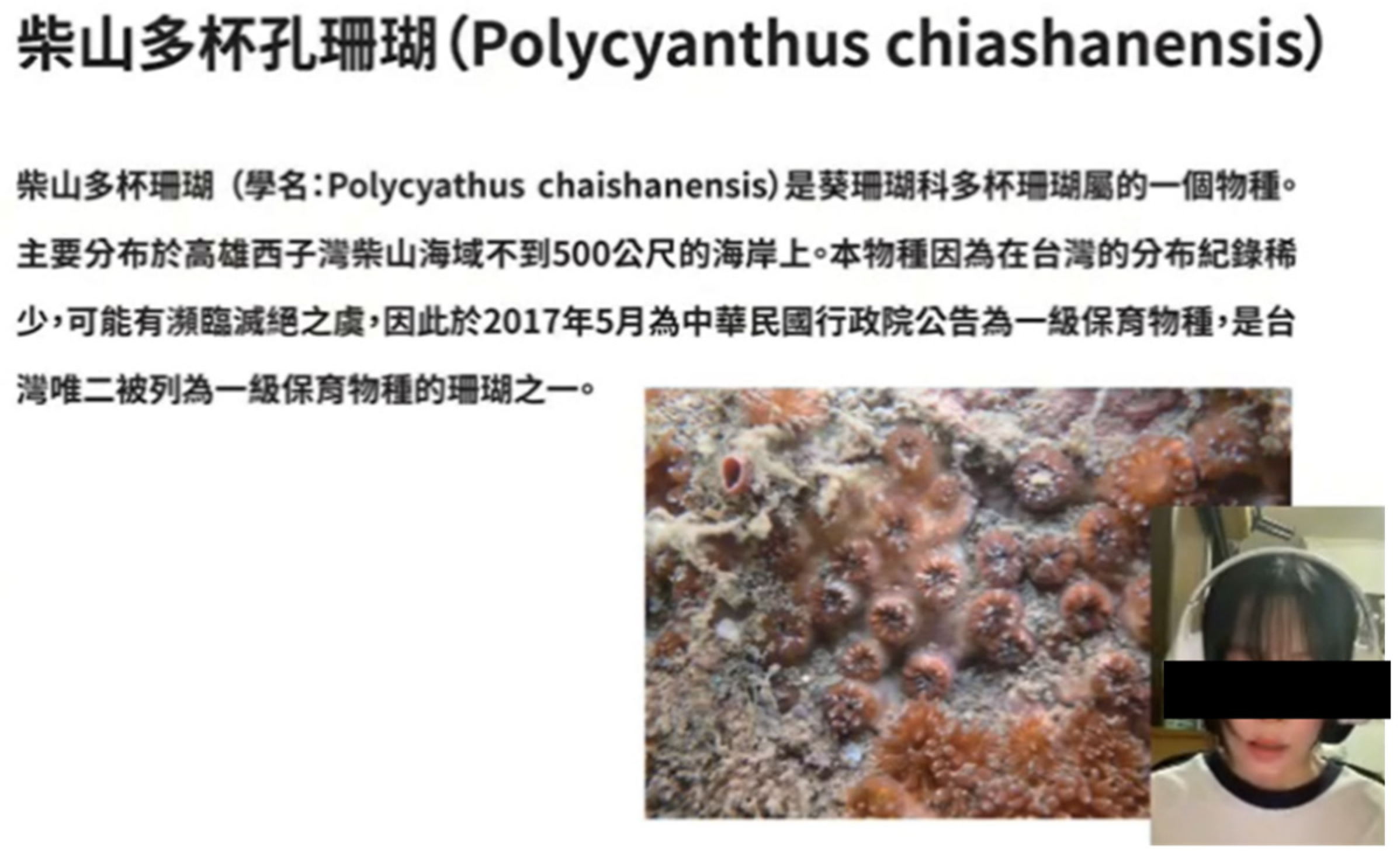

4.2. From Local Environmental Scales to Broader Environmental Issues

4.3. Development of a Curriculum Framework for Environmental Issues Education

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Understanding the Local Environment Should be the Foundational Step When Applying the ARCS Motivational Model to Environmental Issues Education

5.2. Environmental Education Should Emphasize Risk Perception and Coexistence

5.3. Ethical Dimensions of Human–Environment Interactions in Environmental Education

5.4. Environmental Issues as Dynamic, Evolving Educational Content

References

- Yang, G.-Z. (1997). Huanjing jiaoyu. Taipei, Taiwan: Ming Wen.

- UNESCO. UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014): Final Report; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows, H.H. Geography as Human Ecology. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 1923, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, T.W.; Johnston, R.J. Geography and Geographers: Anglo-American Human Geography Since 1945. Geogr. J. 1980, 146, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.-N.; Tseng, Y.-C. An Evaluation Research on Hope-Oriented Climate Change Curriculum at Senior-High School. Chinese Journal of Science Education 2020, 28, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-N. (1995). Environmental issues and analysis. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Geography at National Taiwan Normal University.

- White, G.F. Human adjustment to flood: A geographical approach to the flood problem in the United States; niversity of Chicago Geography Research Paper, No.29; Department of Geography, University of Chicago: Chicago, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima, Y. Case studies on school disaster prevention and mitigation from natural disasters from the perspective of Eco-DRR and science curriculum. JSSE Research Report 2020, 35, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka, T. Material development for environment education concerning with 1978 Miyagi-ken oki Earthquake and 1995 Hyogo-ken nanbu Earthquake. Japanese journal of environmental education, 1998, 7, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, S.; Suzuki, Z. Reconsideration of “learning through nature”; understanding of “sense of wonder” from viewpoint of 3.11 great earthquake. Japanese journal of environmental education 2013, 23, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, T.; Sasaki, T. , & Furihata, S. Transition from learning by experiencing nature to disaster education: How nature school educators applied their knowledge and skills for the 1995 great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake and the 2011 great east Japan earthquake. Japanese journal of environmental education 2013, 22, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, K.; Kumotaki, N. & Hirose, T. Searches for the point of contact of nature conservation education, nature-based experiential learning and disaster education - The Utatsu District, South Sanriku-cho, Miyagi Pref.; to the Case-. Japanese journal of environmental education 2013, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, N. Process of residents’ participation in disaster recovery: A case study of local practices confronting the tide embankment issue in a tsunami disaster area. Japanese journal of environmental education 2015, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T. Analysis of dialog processes at a development meeting for an environmental education program to emphasize the forest–river–ocean relationship in tsunami disaster areas. Japanese journal of environmental education 2016, 24, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai, N.; Tanaka, M.; Nakamura, H. The verification of “Jimoto-gaku of climate change”, and consideration of the formative process for climate change adaptation community. Japanese journal of environmental education 2017, 27, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, N.; Tanaka, M.; Aoki, E. Analysis of the structure of consciousness of mitigation and adaptation behavior to climate change - For regional education on climate change. Japanese journal of environmental education 2015, 25, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Hijiok, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Hanasaki, N. Study on climate change education aimed at fostering regional leaders - based on a comparative analysis between climate change education in Japan and Germany-. Japanese journal of environmental education 2016, 26, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, S.; Shirai, N.; Changgu, K. How can environmental education respond to the climate crisis? Japanese journal of environmental education 2023, 32(3), 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, T. What can metropolitan area’s children learn from the experience of East-Japan earthquake disaster and Minamata disease? Japanese Journal of environmental education 2013, 22(2), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M. Pollution education as “calling human beings and modern education into question”-examining pollution education from the perspective of educational anthropology-. Japanese journal of environmental education 2015, 25, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M. Significance of learning about Kogai in Japan today- environmental pollution education and the Kogai Museum network-. Japanese journal of environmental education, 2015, 25, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furihata, S. Learning by experiencing nature in pollution education - exploring the time of establishment of learning by experiencing nature in the history of Minamata pollution education-. Japanese journal of environmental education, 2015, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOMOZAWA, Y. Sharing the experiences from multiple anti-pollution movements - contribution of the jishu-koza KOGAI genron as a telephone switchboard of experiences -. Japanese journal of environmental education 2015, 25, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osawa, H.; Semba, T. & Makino, H. Communication regarding the risk to health resulting from radiation exposure - An illustration of environmental education material based on experience of telephone counseling following the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant -. Japanese journal of environmental education 2015, 24, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tanno, H. Koichi Yanagida and passing down activities on Minamata disease - focusing on the fundamental struc ture of his ideas -. Japanese Journal of environmental education 2015, 25, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoko, I.; Kae, I.; Masatoshi, T. Faculty challenges during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the results of student questionnaires for the implementation of online and face-to-face classes. Japanese journal of pharmaceutical education 2021, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshikazu, S. Exploratory study of stress management education during the coronavirus pandemic. Hokkaido psychological research 2021, 43, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y. Clinical psychological support for school-aged children darling COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Japanese association of health consultation activity 2020, 15, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima, Y. (2020). Consideration of the science curriculum “immunity” in elementary and junior high schools after the spread of COVID-19 infection. Proceedings of the 44th Annual Meeting of the JSSE, 281-284.

- Zhang, T.-C. (2017). The significance and curriculum shell of seawater education - taking environmental education as an example. Pulse of education 2017, 11, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D.W. Ecological Literacy; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenbrink, E.A.; Pintrich, P.R. Motivation as an enabler for academic success. School Psychology Review 2002, 31, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.M. Development and use of the ARCS Model of instructional Design. Journal of Instructional Development, 1987; 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin, R.M.; Milheim, W.D.; Viechnicki, K.J. The development of a model for the design of motivational adult instruction in higher education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems 1993, 22(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.M.; Koop, T. (1987). An application of the ARCS model of motivation design, In C. Regality (Ed.), Instructional theories in action: Lessons illustrating selected theories and models. (pp. 289–320) Hillsdale, SJ: Lawerence Erlbaum.

- Agrawal, A. Dismantling the Divide Between Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge. Development and Change, 1995, 20, 413–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxnevski, M.L. Understanding our Differences: Performance in Decision-Making with Diverse Groups. Human Relations 1994, 47, 531–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalland, A. (2000). Indigenous Knowledge: Prospects and Limitations. Indigenous environmental Knowledge and its Transformations: Critical Anthropological Perspectives, eds. R. Ellan, P. Parkes, and A. Bicker, 319–331. New Jersey: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Dudgeon, R.C.; Berkes, F. Local Understanding of the Land: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Indigenous Knowledge. Nature Across Cultures 2003, 4, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, M.R. (2000). The Life-cycle of Indigenous Knowledge, and the Case of Natural Rubber Production. Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and its Transformations: Critical Anthropological Perspectives, eds. R. Ellan, P. Parkes, and A. Bicker, 213–252. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic.

- Kuan, D.-W. Indigenous ecological knowledge and watershed governance a case study of the human-river relations in mrqwang, Taiwan. Journal of geographical science 2013, 70, 69–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ARCS Component | Goals of General Education | Learning Objectives of Environmental Education | Learning Outcomes | Instructional Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention (Gaining Attention) | To develop students’ core competencies in communication, critical thinking, and reasoning, and to equip them with foundational skills for advanced academic study. | Conceptual Knowledge of Environmental Issues, Environmental Action, and Skills. | Engaging Students’ Interests and Fostering Their Curiosity. | How to Make Students Perceive the Subject as Worthy of Their Effort and to Inspire Their Willingness to Learn. |

| To cultivate a comprehensive understanding of key disciplinary fields among students. | Interdisciplinary Conceptual Knowledge of Environmental Issues. | |||

| Relevance (Establishing Relevance) | To promote self-understanding, inspire humanistic values, improve individual quality of life, and nurture a well-rounded conception of life’s meaning and purpose. | Environmental Ethical Values | Meeting Students’ Individual Needs and Goals to Foster a Positive Learning Attitude. | |

| To foster a sense of social responsibility, empowering students to become engaged citizens committed to addressing and resolving contemporary social challenges. | Environmental Action Experience | |||

| Confidence (Building Confidence) | To cultivate globally minded citizens who not only understand the society in which they live, but also embrace and explore other cultures, while recognizing their relationship with others, the universe, and the natural world. | Environmental Ethical Values | Assist students in creating positive success and expectations, fostering the belief that success is within their own control. | How can teaching be utilized to assist students in their learning process, establish confidence and self-assessment skills for future learning, and simultaneously foster the belief that success is within their own control? |

| To enhance students’ understanding of human history and civilizations, enabling them to learn from the past, anticipate the future, and acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for future challenges. | Conceptual Knowledge of Environmental Issues, Environmental Action, and Skills. | |||

|

Satisfaction (Providing Satisfaction) |

To emphasize ethical and moral reasoning, enabling students to make discerning judgments and appropriate choices when confronted with moral.dilemmas. | Environmental Ethical Values | Receiving external or internal encouragement driven by achievement, thereby generating a desire to continue learning. |

| Item | Code Description |

|---|---|

| Participants Department Interview Progress DataZSource In-class Discussion Assignment Report |

SA: Department of Fine Arts; SB: Department of Business Administration; SC: Department of Chinese Literature; SD: Department of Visual Communication Design; SE: Department of Education; SF: Arts Class; SP: Department of Physical Education; SS: Special Education; SU: Department of English; SZ: Department of Physics QA: Mid-term interview; QB: Final interview CD HR |

| Case Records (Examples) |

SU-QB03-20231222: Final interview conducted on December 22, 2023, Special Education Department (SU), Student ID: 03 SU-HR03-20231120: Assignment submitted on November 20, 2023, Special Education Department, Student ID: 03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).