1. Introduction

There are many implications when discussing sustainability in learning. These implications generally include learning interests, motivation to learn, and learning and development [

31,

57]. Sustainability in learning contribute to effective classroom practices, regardless of students’ background and other matters such as location and reputation of schools. Sustainability in learning also focuses on learning skills which are the foundation for employability and long-term career development in current business environment and landscape.

Thus, how students can sustain their learning interests and behaviour is a critical issue today whether the focus is on either classroom or workplace [

3,

45]. Note that classroom learning relates to students while workplace learning is closely associated with learners (or workers). This is because learning is now regarded as part of working and has become a common skill for all [

15,

51]. For classroom learning, student-teacher relationships have been the foundation for learning within curriculum’ settings [

56]. Lesson plan development, assessment and evaluation, activities during and after a session, and students’ engagement and communication are the backbone of these relationships. Trust and feeling of psychological safety reflect the relationships’ outcomes.

In addition, effective student engagement should increase the level of intention and motivation (to learn) which subsequently enhances learning skills [

17]. Motivated students can further strengthen their adaptive skills, critical thinking, systems thinking, and problem-solving skills which are essential in tackling complex global issues today [

9,

15]. Failing to establish and maintain effective student-teacher relationships can lead to several adverse effects such as academic disengagement, increased anxiety and stress, behavioural issues and lower academic achievement [

11,

16,

59]. As a result, the success of learning in the primary level (e.g., feeling confident to think critically and work collaboratively with others) usually relies on these relationships [

21,

52,

55].

Despite the student-teacher relationships’ positive impacts, the concern has emerged for secondary students. The reason is that secondary students need to decide (at Year 9) whether to continue their education at the upper secondary level or to pursue vocational education. In addition, students who are in the upper secondary level (from Year 10-12) will likely attend higher education institutes which often require more than academic performance. Nowadays, many universities require the applicants from the upper secondary schools to submit a portfolio which consists of both academic and non-academic performance and activities [

37,

51]. Therefore, these secondary students need to embrace significant changes in university admission which requires more exposure to the environment outside their schools.

For the secondary level, current practices for in-service teacher training need to maintain and balance professional responsibilities while building and sustaining positive relationships with students [

5,

26]. Teachers are expected to have in-depth understanding of subject matters, to command communication skills for effective delivery of lessons and their contents, to become innovative in developing activities that enhance students’ knowledge. Thus, student engagement has not received as much attention as teachers’ actions on academic knowledge [

26,

40].

To ensure effective learning for secondary students, a classroom should no longer be treated as a closed system. A closed system indicates a lack of active and continuous participation from outside. The reason is that, for secondary students, there is a gap between classroom learning at school and their future (i.e., a workplace if they decide to work, a vocational college if they decide to acquire a vocational/professional degree, and a university if they decide to pursue an academic degree). Apparently, this gap cannot be addressed entirely by classroom teachers and student-teacher relationships [

10,

11]. In addition, due to the roles of digital technology, students’ learning cannot be confined primarily in a classroom [

18,

22,

27,

48,

55]. Furthermore, instead of focusing on academic performance, students at the secondary level also need to have feedback for their development (e.g., behavior, maturity, and skills). This feedback should involve with people more from outside and cannot be part of a formal evaluation.

Feedback is information provided to a student directly and indirectly about his or her behavior (e.g., efforts, decision and action, etc.) with respect to the specific expectations, goals, and/or outcomes [

4,

54]. Feedback helps a student refocus his or her behavior to achieve these expectations, goals, and outcomes [

57]. On the other hand, evaluation represents information from formalized assessment of a student’s academic performance relative to a curriculum [

39]. Thus, evaluation illustrates academic performance while feedback points to an area where a student can or need to improve. Thus, feedback can be direct (e.g., verbal conversations and joint activities) and indirect (e.g., listening and other gestures) while evaluation often results in the value which demonstrates excellent or poor performance.

Feedback has long been considered as a stimulus for students’ learning [

54]. Feedback can contribute to a change in students’ behavior- what they do and why they do it. Not only should feedback relate to desirable behaviors but also entice learning interests and lead to a higher level of learning motivation [

1,

4]. Thus, feedback can add to classroom dynamics and result in more positive learning outcomes. Thus, examining the impacts from feedback from the outside on student’s mindset and behavior relating to learning potentially helps sustain learning and development of students, especially at the secondary level (i.e., Year 7-17 as the lower secondary level indicates Year 7-9 while the upper secondary level indicates Year 10-12.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Double- loop Learning and Feedback

Feedback reflects not only how well students perform but can also point to an area which they can improve. Feedback is generally constructive and can be individualized to help entice learning interest and improve learning behavior [

12]. In addition, constructive feedback, which is often indirect in nature (to help students avoid any confusion with evaluation), should challenge students to think about and correct their mistakes. This is part of developing students’ learning skills [

19]. In addition, feedback, unlike evaluation, can come from teachers, peers, and people from outside. Feedback can focus on behavior (e.g., decision and action), mindset and paradigm, etc. (instead of academic performance like evaluation). Feedback also represents continuous attention and active engagement with students. People from outside can bring their experiences and provide feedback to help prepare students after their high-school graduation.

In general, feedback loop is an integral part of a long-term learning strategy for students [

2,

4,

7,

14]. This strategy consists of the first loop which involves changing actions to meet expectations and requirements relating to a task, and the second loop which focuses on beliefs and assumptions that result in a decision and an action taken by students. Thus, indirect feedback can potentially address both loops [

35,

36]. For instance, when a student feels that he or she cannot succeed in class due to family’s economic background and school’s reputation, indirect feedback can involve a visit by people from outside classroom or school who can provide direct conversations about their school’s work and give recognition of students’ success. Outside people can include business operators, entrepreneurs, scholars, experts, community leaders, etc. The visit itself can be regarded as indirect feedback about the attention and support that this student needs. Finally, the Double-loop Learning concept focuses on how a student learns, which is fundamental for sustainable learning.

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior and Learning Process

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is an important psychological framework that helps describe how an individual behaves and how this behavior is influenced (e.g., what factors influence an individual’s behavior) [

1,

44]. This behavior can include learning, performing a task, interacting with colleagues, communicating with customers, etc. [

56]. Within the context of behavior, it is important to first examine an individual’s intention. This intention represents the first step prior to an individual’s decision and action [

3]. Often, this intention, based on personal interests, is influenced by a learner’s paradigm or mindset about a specific circumstance (e.g., I believe I can succeed in this surrounding environment). In other words, this paradigm or mindset contributes to an intention of an individual which leads to his or her decision or an action (or behavior) [

1,

23]. Based on the TPB, an individual’s paradigm or mindset is influenced by three key factors: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

1,

23]. The presumption is that these three factors can predict whether an individual will show specific behaviors.

The term attitude refers to the individual's positive or negative evaluations when he or she is faced with a circumstance or a situation such as a need to perform and/or complete a specific task [

29,

34,

58]. If a person believes that the behavior will lead to favorable outcomes (e.g., task completion), then he or she is more likely to have a positive attitude and will be inclined to take appropriate action [

53]. Subjective norms reflect the influences that peers, outsiders, and others have on a student’s mindset and paradigm, intention, decision, and action [

38]. In other words, subjective norms represent a condition in a classroom that the expectation from peers and others from outside can be influential to a student [

23,

38] This is often referred to as social expectation in a classroom.

In addition, perceived behavior control describes whether a student feels that he or she can control, handle, and complete a given task (for task completion). To be able to control a given task, a student needs both capability and opportunity for his or her performance. In this study, the perceived behavior control factor is excluded. The reason is that, in a classroom environment, the roles of a teacher remain in control of content delivery and classroom management, which minimizes the effect or influence from this perceived-behavior-control factor [

21,

39,

42]. In summary, the Double-loop Learning concept and the TPB illustrate that learning behavior depends on learning intention, feedback, paradigm and mindset, awareness of expectation from others, and capability [

1,

21,

24,

36,

46,

58].

3. Objective

Given the importance of learning skills for secondary students, the study aims to examine and understand their past experiences with the effects from indirect feedback, attitude and subjective norms on their paradigm and mindset about learning. Understanding their experiences is important for sustainability in learning which includes issues such as classroom openness to outside and teachers’ roles in fostering learning. Note that the schools regularly engaged with business and surrounding communities, especially local business owners and entrepreneurs. Their roles are to observe students’ work and assignments through a series of visits as well as school activities such as contests and national/regional-related events (e.g., environmental awareness). Their interests in engaging with students and schools are part of social responsibility.

4. Materials and Methods

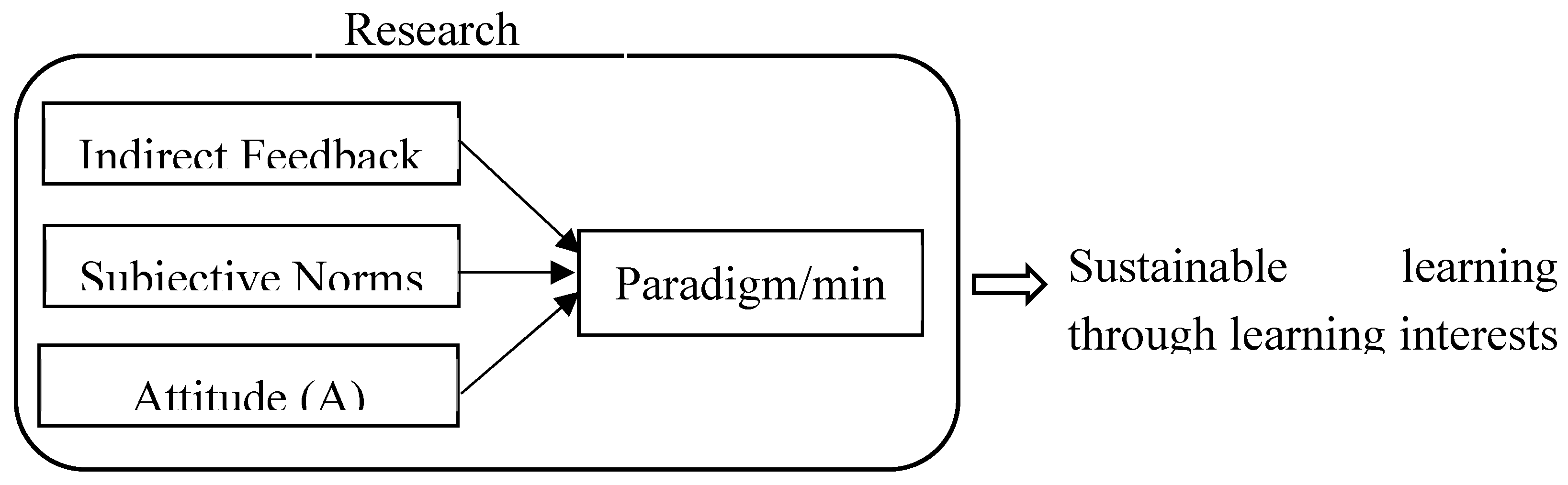

This data of this case study was collected from secondary student enrolled in Indonesian schools (from the central Java region). Focusing on secondary students allows better understanding of the impacts from indirect feedback as well as other factors (i.e., attitude and subjective norms). The involvement of people from outside for indirect feedback is not commonly practiced in primary schools. The data was collected in early 2024 with the emphasis on the past experiences that these students have had with indirect feedback, attitude, and subjective norms. The research utilizes both Google Forms and direct online distribution methods. Data analysis focuses on evaluating the possible influence from the following three factors on students’ learning behavior. These factors are: (1) indirect feedback from teachers and external collaborators, (2) subjective norms reflecting the level of influence social expectations from peers and teachers, and (3) students’ attitude. The development of this survey is based on the Double-loop Learning concept for indirect feedback and TPB for attitude and subjective norms. See

Figure 1. Also, there are three hypotheses for this study, based on

Figure 1. They are as follows.

H1: Indirect feedback (IF) influences paradigm/mindset

H2: Subjective norm (S) influences paradigm/mindset

H3: Attitude (A) influences paradigm/mindset

There are three sections in the survey: (1) introduction, (2) information of the participants, (3) survey items relating to attitude, subjective norms, indirect feedback, and paradigm/mindset. The survey adapts the 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree and 5 = Strongly agree) to gain the opinions of participants on the factors in the research model. See

Appendix A. Data analyses include SPSS and Smart PLS. Firstly, the reliability of the results will be evaluated. Then, the Factor loading analysis will be used for this analysis. Additionally, based on [

25], indexes such as p-values, ꭕ

2/df, RMSEA, SRMR, GFI and CFI will also be applied to help assess the results. Using these indexes values will allow a possible improvement to the research model and the interrelationships among the four key factors. Furthermore, structural equation modeling (SEM) will be applied as part of data analyses [

58]

5. Results

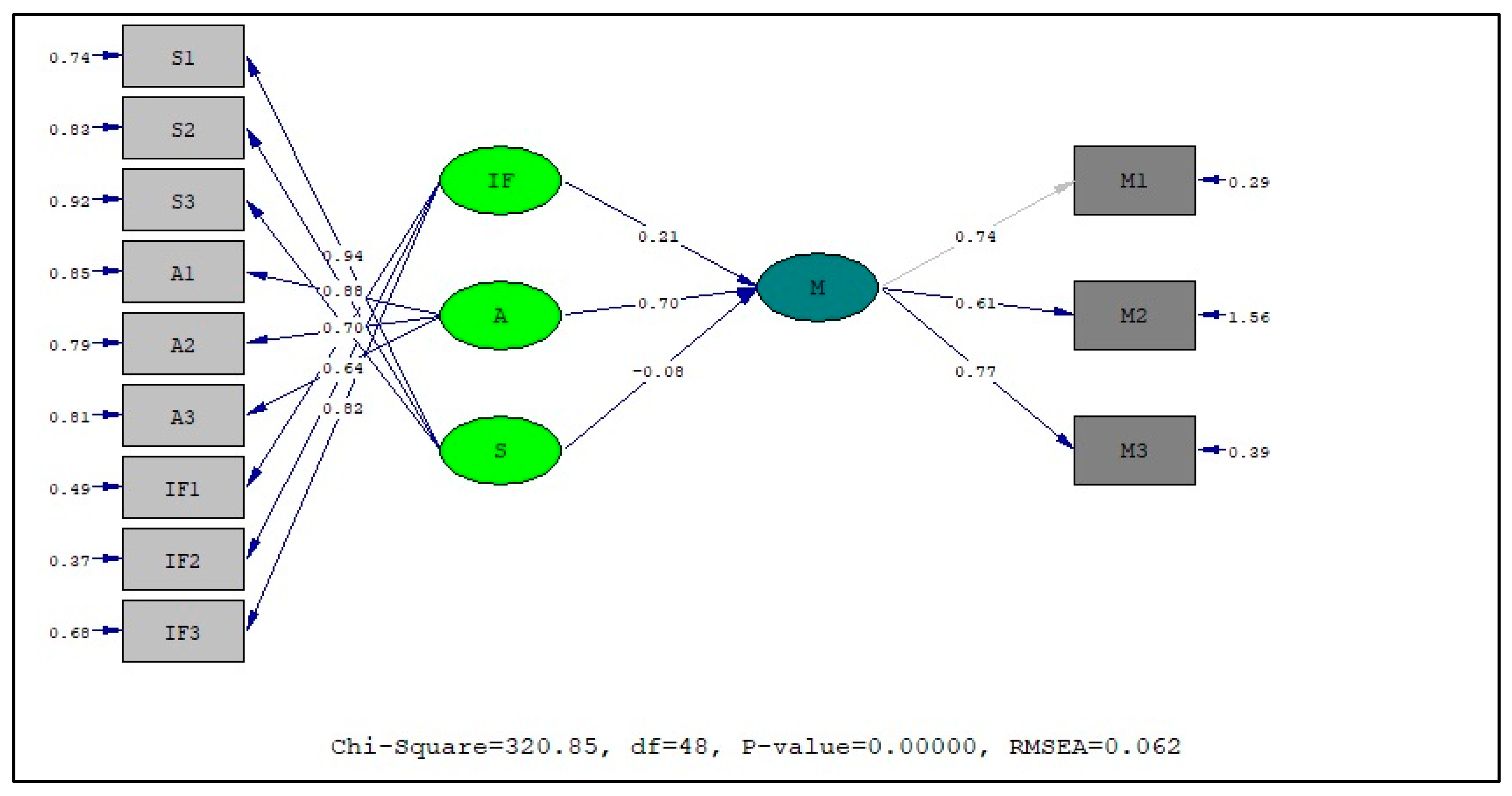

A total of 1,473 students from eight secondary schools participated in the survey, representing about 50% of registered secondary students. These eight schools have consistently involved people from outside for students’ engagement, especially local business operators and entrepreneurs. The students are diverse in terms of family background, especially financial well-being. An analysis is conducted to examine the significance of individual questions within each of the four factors (i.e., Indirect Feedback or IF, Subjective Norms or S, and Attitude or A, and Paradigm/mindset or M. This examination uses the Linear Structural Relationships (LISREL) method which is appropriate for this type of study [

25,

32,

43]. Based on the Factor Loading Analysis, all questions within each factor have significant influence due to the correlation between the item and the factor of more than 0.60 [

20]. Then, the next step involves the use of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Initially, the overall result shows that the model is not acceptable since its p-value is 0 while it needs to be greater than 0.05 [

43,

49,

50]. In addition, the initial model shows a lack of significant influence from S to M as its beta value is negative (Beta = - 0.08) [

33]. This initial model only shows the positive influences from IF and A on M. As a result, the S factor is removed. See

Figure 2.

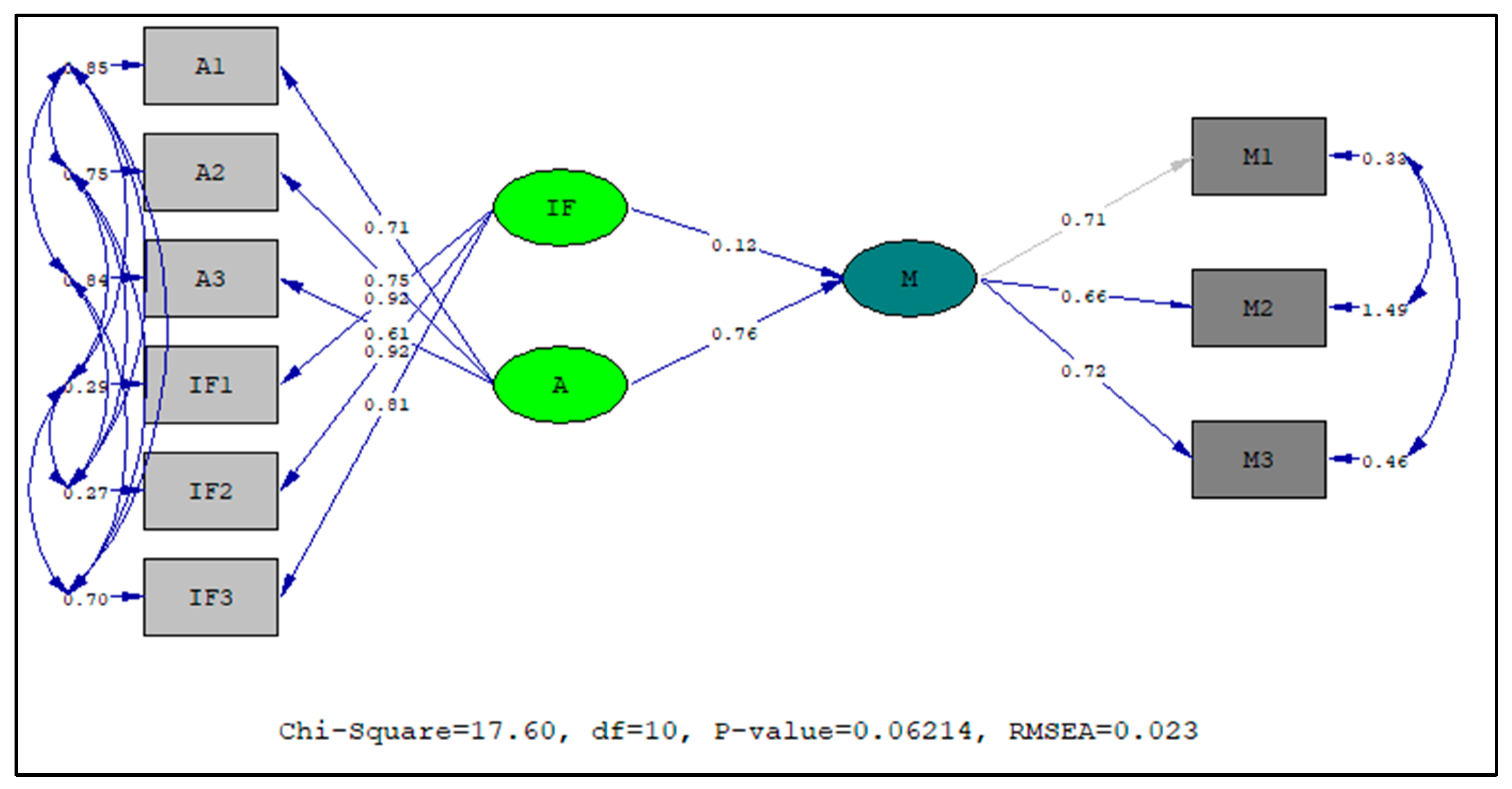

The second model (after the S removal) passes all criteria, including Chi square/DF or CMIN, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation or RMSEA, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual or SRMR, Goodness of Fit Index or GFI, Comparative Fit Index or CFI, and Normal Fit Index or NFI. The improved model shows that IF and A positively contribute to M. See

Figure 3, and

Table 1 and

Table 2.

To help gain more insights into the specific impacts from individual items of IF and A on M, the Factor Loading analysis is applied. The results from all individual questions from IF and A have had a significant influence due to the correlation value of more than 0.60 with the p-value < 0.01. See

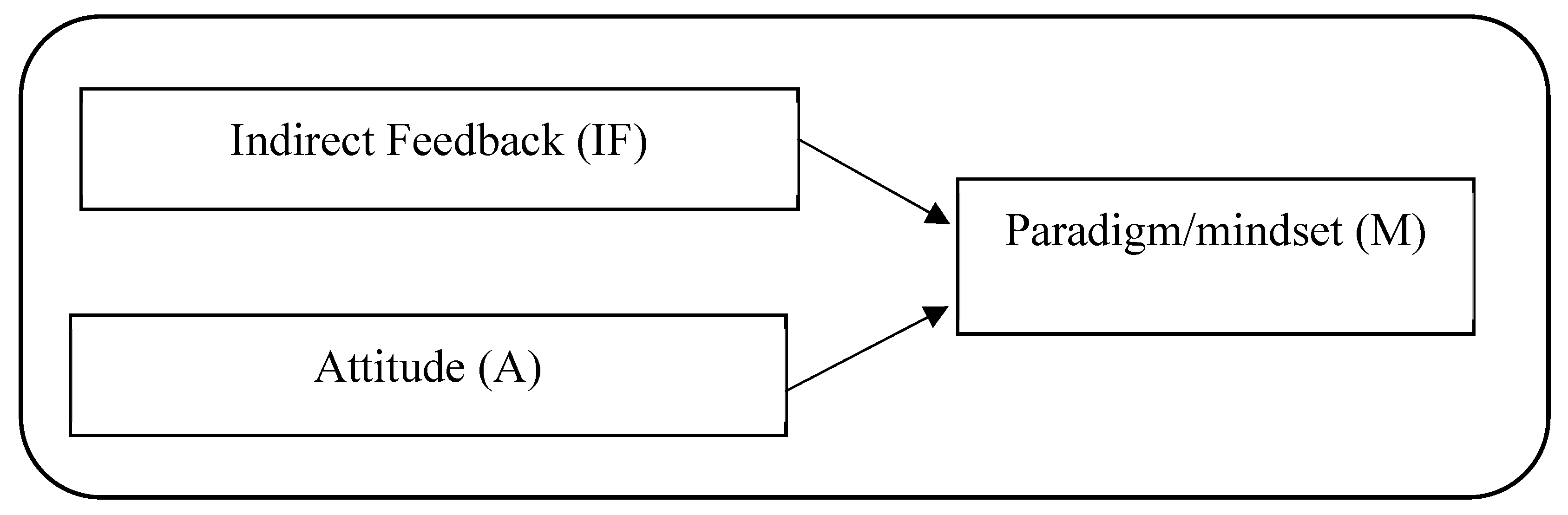

Table 3. Also, based on the statistical analyses, the following conclusion can be made regarding the three hypotheses. H1 (Indirect feedback influences paradigm/mindset.) and H3 (Attitude influences paradigm/mindset.) are accepted while H2 (Subjective norms influence paradigm/mindset.) is rejected. This highlights the continued importance of teachers in shaping students’ attitude. Moreover, these results underline the significance of people from outside as part of indirect feedback.

Based on the results from

Table 3, A2 (I believe that the mistake that I have made during school is part of learning and development.) plays the most significant impact on learning. This attitude stems from effective student-teacher relationships (e.g., trust, care, attention, and continuity). Also, IF1 (An opportunity to interact with people outside school can motivate me to learn and work harder.) and IF 2 (An opportunity to share my ideas with people outside school helps improve my weaknesses and increase my knowledge and skills to succeed.) contribute positively to students’ paradigm and mindset. This indicates the importance of viewing a classroom (e.g., its learning environment) as an open system. Thus, after the statistical analyses, the research model shows the positive influence on students’ paradigm and mindset from indirect feedback and attitude. See

Figure 4.

6. Discussion

The findings provide good insights into potential improvements to help sustain student’s learning, especially at the secondary level. Firstly, the findings reinforces the importance of teachers, despite availability of digital technology for studying and exploring different sources of information and knowledge [

30,

56]. Teachers still play a role in inspiring self- confidence and -belief among students on a continuous basis. Item A1 (I feel that I can always learn more while I am at school.) shows positive impacts from these confidence and belief on paradigm and mindset about learning. In addition, teachers need to ensure the feeling of psychological safety among students (based on item A3 (I feel that I can openly discuss work and problems with anyone at school). This issue becomes critical because sustainability in learning includes informal learning [

45,

57]. Informal learning represents an unstructured way of learning- without learning objectives, lesson plans, and formalized assessment outside a classroom. Informal learning encourages an ability to learn by mistake, from observation, and based on conversations with peers and people from outside which can be significantly influenced by teachers.

The findings also point to the importance of having indirect feedback as part of students’ learning experiences [

6,

54]. All three IF items show the significant impact on students’ paradigm and mindset about learning. In addition to both IF1 and IF2, IF3 (An opportunity for people outside school to engage with work and to interact with me is helpful for my belief and confidence.) underlines students’ positive experiences with people from outside (e.g., business operators, entrepreneurs, scholars, experts, community leaders, etc.). In other words, having an opportunity to interact and engage with people outside school has strong potential to further enhance students’ paradigm and mindset about learning [

39,

57]. The reasons are that indirect feedback can help increase the level of learning motivation for secondary students (in accordance to IF1), improve many future employability issues for secondary students such as preparing a presentation to people outside, listening to comments, assessing ways to improve their school work, practicing teambuilding and communication skills (as described by IF2), and provide learning experiences, confidence, and belief needed for life-long learning (shown in IF3).

Dealing with secondary students who come from a challenging family background (especially poverty or a broken family) has been a major concern for teaching and learning at school [

15,

17,

30]. Building and maintaining positive attitude are essential for the paradigm and mindset of disadvantaged students on learning [

44]. To strengthen positive paradigm and mindset, the consideration into an open-system approach for classroom management (i.e., bringing and collaborating more with people from outside) should be made. Secondary students, who probably look at their future after completing their school, show strong learning interests in external interactions. This approach can also address some underlying assumptions of students who are from a less affluent family [

4,

17]. Often, they believe that their future is determined by a family status and privilege. Having people from outside shows that, regardless of their background, students should be given attention and useful feedback for their school’s work. Thus, positive paradigm and mindset are important for enticing learning interests [

37].

It is also important to discuss about the impacts from the subjective norms. Although this term is removed from the first model so that the final model can pass the criteria of all key indexes, the insignificant impact from the subjective norms (e.g., social expectation from peers) needs to be examined. Past studies have shown subjective norms to be more impactful with younger students [

10,

42]. On the other hand, the impacts from subjective norms on learning intention (through paradigm and mindset) become less for students who are often concerned about their future such as less-affluent secondary schools [

6,

39,

42,

45]. Thus, for participating secondary students with diverse backgrounds (family background- affluent and disadvantaged, career intention- work, vocational education, or higher education, etc.), the impacts from subjective norms can possibly be insignificant or minimum. As a result, the influences from classroom’s peers are not viewed as significance for paradigm and mindset.

7. Implications

The results from the survey support the continuous roles of teachers (through effective student-teacher relationships) in fostering learning and development of students [

8,

13,

21]. Students’ attitude is generally affected by teachers’ engagement and learning experiences [

47]. The need to balance between academic excellence (through a standardized assessment and examination) and building student-teacher relationships (with trust, empathy, and consistency) remains essential for students’ paradigm and mindset. These paradigm and mindset are essential for learning interests, intention to learn, and learning behaviour which help sustain development and strengthen learning skills of students. In other words, effective student- teacher relationships help create the feeling of psychological safety, leading to stronger social-emotional development, interpersonal interactions, learning from observations and conversations, collaboration, experience sharing, and challenging ideas [

19,

28]. More importantly, these relationships are fundamental for creating a thriving learning environment and positive learning experiences which are considered as an enable for the sustainability in learning.

The use of indirect feedback in a classroom is proven to be positive. As indicated in the Double-loop Learning concept, indirect feedback can give students a sense of recognition, belief, and confidence [

35,

41]. The reason is that, based on the first loop, students feel they have made a right decision or have taken an appropriate action for their academic work. An opportunity to engage and interact with people from outside helps reassure about their learning activities (e.g., knowing that their ideas and work are valuable to people from outside). Based on the second loop, attention and time that participating students have received represent indirect (and non-verbal) feedback. Indirect feedback shows that regardless of students’ background, they deserve to receive appropriate attention and time from people outside school. This recognition can be considered as a meaningful message, especially from disadvantaged students. It is important that feedback needs to challenge student’s prevailing assumptions about learning [

39,

54]. These assumptions often include the following- no matter how hard I work; I will not succeed. Because of my family background, I will have less opportunity than others. Based on the findings, indirect feedback seems to be reasonable and achievable without any drastic change in classroom management.

From the conceptual viewpoint, these implications help reaffirm the importance of both the Double-loop Learning and TPB for understanding a learning process and identifying critical factors to strengthen positive paradigm and mindset about learning. Based on the past experiences of participating students, effective student-teacher relationships clearly illustrate the roles of teachers in building positive attitude towards learning [

47,

48,

56,

59]. On the other hand, indirect feedback, can provide meaningful information that can influence decisions and actions of students (whether they are doing things right) and address their prevailing assumptions that could prevent them from learning- a lack of learning interests, learning intention, and learning motivation [

45,

51,

57]. In other words, feedback enhances a learning process of students.

Finally, from the practical standpoint, sustainability in learning involves the critical issues which entice learning interests and intentions from students (as the foundation for life-long learning). Developing students’ learning skills should begin not only with teachers but also understands the roles of people from outside school, especially for secondary students. As indicated by the findings, involving these people can potentially contribute to higher learning interests of students, increase their intention to learn, improve their learning experiences, and raise their motivation to learn. It is important to point out that sustainability in learning is not about what students learn. This term emphasizes how students learn- highlighting the significance of student-teacher relationships and indirect feedback.

8. Limitations and Future Research

There are three important issues for the research’s limitation. Firstly, this research attempts to capture the perspectives and perceptions of students, based on their past experiences at school. Each of the eight schools uses different practices when involving people outside school for students’ engagement. Secondly, students from these eight schools are diverse, especially their family background. This diversity may affect the strengths of the interrelationship from each survey question and the level of impacts from indirect feedback, attitude, and subjective norms on students’ paradigm and mindset about learning. Thirdly, the data is based on secondary students from Indonesia which can be unique and likely differ in other countries and regions.

To overcome these limitations, future research should extend the findings by specifically evaluating the impacts from the following issues- age group of students (e.g., lower vs. upper secondary groups), size of family (e.g., one vs. two or more siblings), family status (e.g., living with parents and/or relatives vs. living with others), etc. Comparing the findings between the two groups can increase more confidence to the previous findings and discussion. An extensive comparison with other countries and regions is also recommended. This comparison can provide more confidence into the roles of indirect feedback and how it can be integrated into classroom management and pedagogical practices as part of students’ learning experiences.

9. Conclusions

Embracing learning skills which has become an important part of their professional development in the future is an integral part of sustainability in learning. Thus, study aims to examine and understand their past experiences of secondary students with indirect feedback, attitude and subjective norms and how their experiences impact these three factors on their paradigm and mindset about learning. The research is a case-study with the use of a survey. The survey is based on the Double-loop Learning concept and TPB. A total of 1,473 students from eight secondary schools located in the central Java region (Indonesia) participated in the survey. After extensive statistical analyses, two factors (i.e., attitude and indirect feedback) significantly and directly influence students’ paradigm and mindset about learning. However, the impacts from subjective norms are not significant. Key implications include the continuous importance of student-teacher relationships (for creating and sustaining students’ positive attitude) and the potential roles of people outside school to engage with students who are mostly from a less-affluent family, especially at the secondary level. In other words, both indirect feedback and attitude contribute to higher learning interests and positive learning experience which stem from these positive paradigm and mindset. Understanding students’ viewpoints is important for pedagogical practices, classroom openness to outside, and teachers’ roles in fostering learning. Finally, the limitations and future studies are discussed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P. and A.Y; methodology, K.P. and P.R; software, P.R. and W.I; validation, K.P. and A.Y.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, K.P and A.Y.; resources, A.Y and W.I.; data curation, K.P and P.R; writing—original draft preparation, K.P; writing—review and editing, K.P.; visualization, A.Y and P.R; supervision, K.P; project administration, K.P.; funding acquisition, K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) through Kasetsart University (N42A660996).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IF |

Indirect Feedback |

| A |

Attitude |

| M |

Paradigm/mindset |

| S |

Subjective Norms |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Illustration of Survey Questions.

Table A1.

Illustration of Survey Questions.

| Item |

Description |

Level of Agreement

(Based on Past Experiences) |

| Never |

Seldom |

Sometimes |

Often |

Always |

| Subjective Norms |

| S1 |

Expectations and attention within school have significantly influenced how I approach my work. |

|

|

|

|

|

| S2 |

I feel that my work should be aligned with friends and colleagues in class. |

|

|

|

|

|

| S3 |

I have continuously tried to become aware of the classroom’s expectation. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Attitude |

| A1 |

I feel that I can always learn more while I am at school. |

|

|

|

|

|

| A2 |

I believe that the mistake that I have made during school is part of learning and development. |

|

|

|

|

|

| A3 |

I feel that I can openly discuss work and problems with anyone at school |

|

|

|

|

|

| Indirect Feedback |

| IF1 |

An opportunity to interact with people outside school can motivate me to learn and work harder. |

|

|

|

|

|

| IF2 |

An opportunity to share my ideas with people outside school helps improve my weaknesses and increase my knowledge and skills to succeed. |

|

|

|

|

|

| IF3 |

An opportunity for people outside school to engage with work and to interact with me is helpful for my belief and confidence. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Paradigm/Mindset |

| M1 |

I believe that if I continue to learn and work hard, I will succeed. |

|

|

|

|

|

| M2 |

My family background should not determine my success at school and in the future. |

|

|

|

|

|

| M3 |

Success should come from continuous learning and improvement. |

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Ajzen, I. Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akınoğlu, O.; Tandoğan, R.Ö. The Effects of Problem-Based Active Learning in Science Education on Students’ Academic Achievement, Attitude, and Concept Learning. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 2007, 3, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus, M.; McDonald, T.; Ormond, C.; Rybarcyk, R.; Taylor, A.; Winterton, A. Trajectories of Classroom Behaviour and Academic Progress: A Study of Student Engagement with Learning. Edith Cowan University, Western Australia: Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review 1991, 69, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ayvaz-Tuncel, Z.; Çobanoğlu, F. In-Service Teacher Training: Problems of the Teachers as Learners. International Journal of Instruction 2018, 11, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biisova, G.; Amirov, A.; Duisenbayev, A.; Baltymova, M. Modelling the Process of Moral Socialisation for High School Students. International Journal of Innovation and Learning 2023, 34, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, M. Pushing the Limits of Adaptiveness Through Double Loop Learning: Organizational Dilemmas in Delivering Sexual Reproductive Health Rights Education in Uganda. Educational Action Research 2023, 31, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.M.; Rodríguez, C.; Aparicio, J.L. Sustainability in Teaching: An Evaluation of University Teachers and Students. Sustainability 2018, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; Losch, K.; Michel, J.; Mochizuki, Y.; Rieckmann, M.; Parnell, R.; Walker, P.; Zint, M. Key Competencies in Sustainability in Higher Education—Toward an Agreed-Upon Reference Framework. Sustainability Science 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkiewicz, A.; Widen, J.; Yasukawa, K. Making Connections to Re-Engage Young People in Learning: Dimensions of Practice. Literacy & Numeracy Studies 2010, 18, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Han, H. Understanding the Influence of Teacher-Student Relationship on Mathematics Achievement: Evidence from Korean Students. SAGE Open 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.W. The Role of Feedback Literacy in Written Corrective Feedback Research: From Feedback Information to Feedback Ecology. Cogent Education 2022, 9, 2082120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, A. The Role of Student Services in the Improving of Student Experience in Higher Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2013, 92, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. Double-Loop Learning and Productive Reasoning: Chris Argyris’s Contributions to a Framework for Lifelong Learning and Inquiry. Midwest Social Sciences Journal 2021, 24, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovini, C. How to Foster Student Engagement with Technology and the Mediating Role of the Teacher's Strategy: Lessons Learned in a Problem-Based Learning University. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2024, 35, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, C. The Relationship Between Teacher-Student Relationship, Self-Confidence, and Academic Achievement in the Chinese Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H.; Bovaird, S.; Mueller, M. The Impact of Poverty on Educational Outcomes for Children. Pediatrics & Child Health 2007, 12, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; Román-Graván, P.; Reyes-Rebollo, M.M.; Montenegro-Rueda, M. Impact of Educational Technology on Teacher Stress and Anxiety: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoorchaei, B.; Mamashloo, F.; Ayatollahi, M.A.; Mohammadzadeh, A. Effect of Direct and Indirect Corrective Feedback on Iranian EFL Writers’ Short- and Long-Term Retention of Subject-Verb Agreement. Cogent Education 2022, 9, 2014022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt, J.; de Bronstein, A.A.; Greyling, J.; Bissett, S. Transforming Entrepreneurship Education: Interdisciplinary Insights on Innovative Methods and Formats. In Transforming Entrepreneurship Education: Interdisciplinary Insights on Innovative Methods and Formats; Springer International Publishing: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.K. The Reciprocal and Correlative Relationship Between Learning Culture and Online Education: A Case from Saudi Arabia. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2014, 15, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, S.A. The Theory of Planned Behavior and Financial Literacy to Analyze Intention in Mutual Fund Product Investment. 2021, 187, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- Hewavitharana, T.; Nanayakkara, S.; Perera, A.; Perera, P. Modifying the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Model for the Digital Transformation of the Construction Industry from the User Perspective. Informatics 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, A.; Vesalainen, M. Challenges in Developing In-Service Teacher Training: Lessons Learnt from Two Projects for Teachers of Swedish in Finland. Journal of Applied Language Studies 2017, 11, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, W. Wisdom from Experience Paradox: Organizational Learning, Mistakes, Hierarchy, and Maturity Issues. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 19, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankshear, C.; Knobel, M. New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Social Learning; Open University Press: 2011.http://www.wired.comlmagazineI2010/08/fLwebrip/.

- Latorre-Cosculluela, L.; Sin-Torres, E.; Anzano-Oto, S. Links between Innovation and Inclusive Education: A Qualitative Analysis of Teachers' and Leaders' Perceptions. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2024, 36, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llin, G. Sustainability in Lifelong Learning: Learners’ Perceptions from a Turkish Distance Language Education Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, R.G. A Guide to LISREL-Type Structural Equation Modeling. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. 1982, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Mahmoodi, F. Factors Affecting Acceptance and Use of Educational Wikis: Using Technology Acceptance Model (3). Interdiscip. J. Virtual Learn. Med. Sci. 2019, 10, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, R.; Jayavelu, R. Testing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Business, Engineering and Arts and Science Students Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Comparative Study. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 7, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutter, E.R.; Liu, Z.; Gollwitzer, P.M.; Oettingen, G. More Direction but Less Freedom? How Task Rules Affect Intrinsic Motivation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2023, 152, 1484–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandini, W.; Gustomo, A.; Sushandoyo, D. The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance. Economies 2022, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngah, A.; Kamalrulzaman, N.; Abdullah, N.; Ariffin, N.; Din, R. Undergraduate Student Performance During the Pandemic: A Sequential Mediation Effect of Grit and Student Motivation. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2024, 36, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norisnita, M.; Indriati, F. Application of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in Cryptocurrency Investment Prediction: A Literature Review. J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 5, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.; Abdularhim, M. The Criteria of Constructive Feedback: The Feedback That Counts. Journal of Health Specialties. 2017, 5, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamwonyi, E. In-Service Education of Teachers: Overview, Problems, and Way Forward. Journal of Education and Practice. 2016, 7, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, M.A.; Mendoza, G.; Velarde, C.M.; Tus, J. The Relationship Between Social Support and Depression Among Senior High School Students in the Midst of Online Learning Modality. Zenodo 2022, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyarini, A.; Anif, S.; Harsono; Narimo, S.; Nugroho, M. Peer Collaboration in P5: Students' Perspective of Project-Based Learning in Multicultural School Setting. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2025, 37, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudon, P. Confirmatory Factor Analysis as a Tool in Research Using Questionnaires: A Critique. Comprehensive Psychology 2015, 4, 03.CP–4.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.; Courneya, K. Modelling the Theory of Planned Behavior and Past Behavior. Psychol. Health & Medicine. 2003, 8, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, L.; Alves, J.; Soares, D. Mapping Innovation in Educational Contexts: Drivers and Barriers. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2024, 35, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, P.R.; Pai, Y.P.; Kidiyoor, G.; Prabhu, N. Development and Initial Validation of a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire: Assessment of Purchase Intentions Towards Products Associated with CRM Campaigns. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2229528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofroniou, A.; Premnath, B.; Poutos, K. Capturing Student Satisfaction: A Case Study on the National Student Survey Results to Identify the Needs of Students in STEM-Related Courses for a Better Learning Experience. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R. Classroom Digital Teaching and College Students’ Academic Burnout in the Post COVID-19 Era: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchishrava, D.; Prashant, K.C.; Sahu, M. Development and Validation of Physical Education Awareness Instrument (PEA-I). J. Adv. Zool. 2023, 44, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Veiga, R.; Veiga, L.; Malhotra, N.K. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL: An Initial Vision. Braz. J. Mark.-BJM Rev. Bras. Mark.-ReMark Edição Especial 2014, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Mai, T.; Luu, T. The Influence of Work Environment on Employees' Innovative Work Behaviours in Vietnam Construction Companies. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2025, 37, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmar, U.; Sismiati, S.; Sulaiman, S. Implementation Student Learning Achievement for Student: Literature Review. DIJDBM 2024, 5, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakola, M. Multilevel Readiness to Organizational Change: A Conceptual Approach. J. Change Manag. 2013, 13, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmeyer, R.; Rheinberg, F. A Surprising Effect of Feedback on Learning. Learning and Instruction. 2005, 15, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshe, N.; Sund, L. Developing (Transformative) Environmental and Sustainability Education in Classroom Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J. Good Teacher-Student Relationships: Perspectives of Teachers in Urban High Schools. American Secondary Education 2023, 4391, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, B.; Li, K.; Chan, T. A Survey of Smart Learning Practices: Contexts, Benefits, and Challenges. International Journal of Innovation and Learning. 2023, 34, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanabazar, A.; Jambal, T. The Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Mindset and Entrepreneurial Intention: An Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behavior. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2023, 13, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Toward the Positive Consequences of Teacher-Student Rapport for Students’ Academic Engagement in the Practical Instruction Classrooms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 759785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).