Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

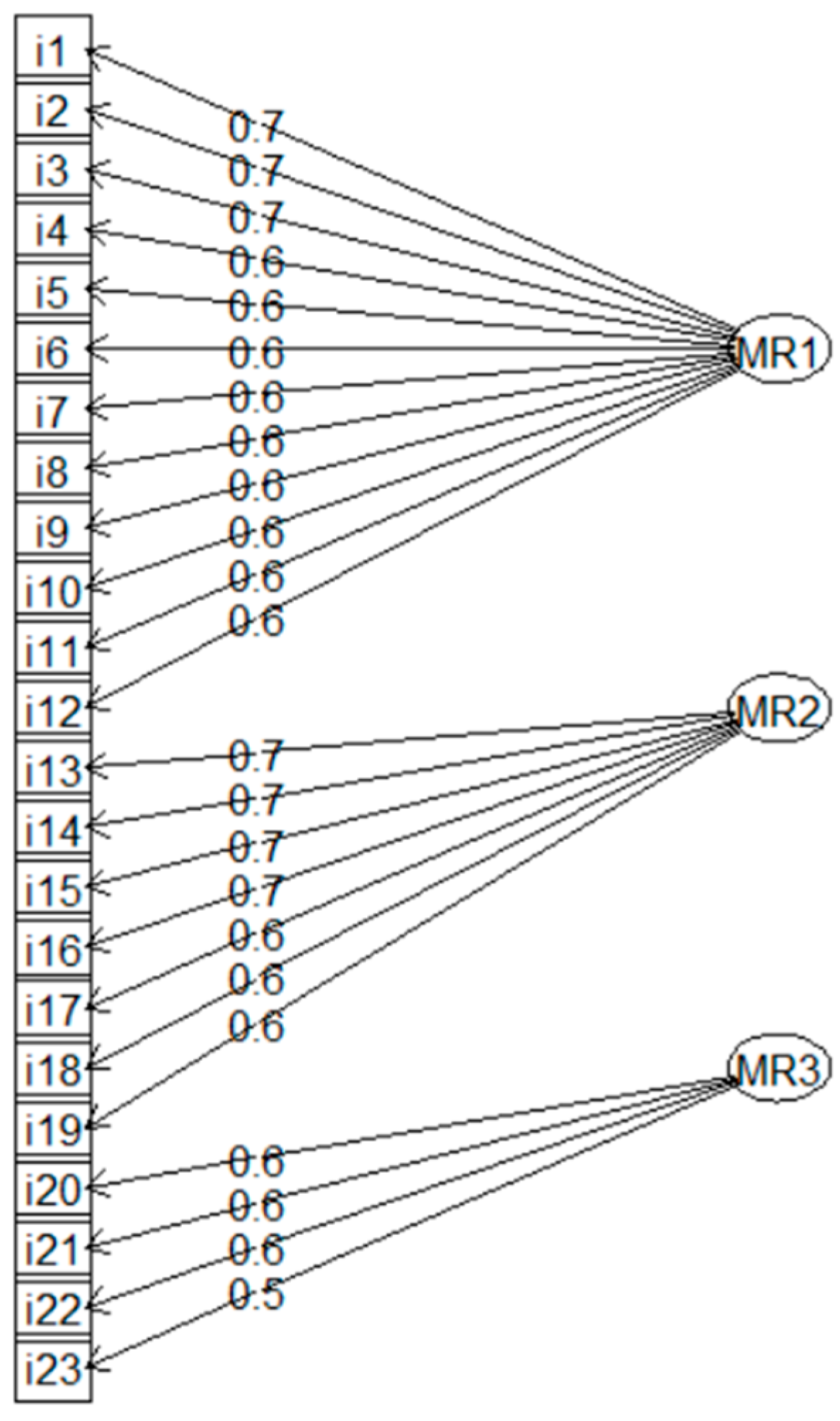

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

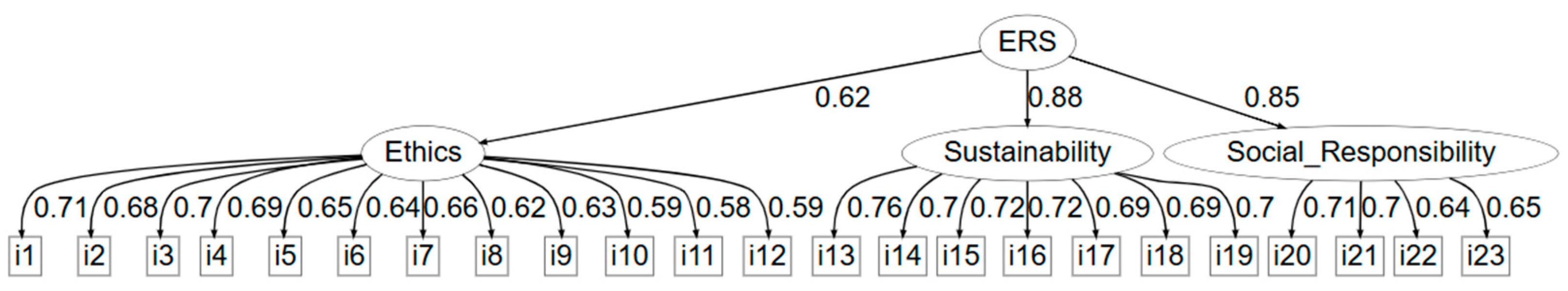

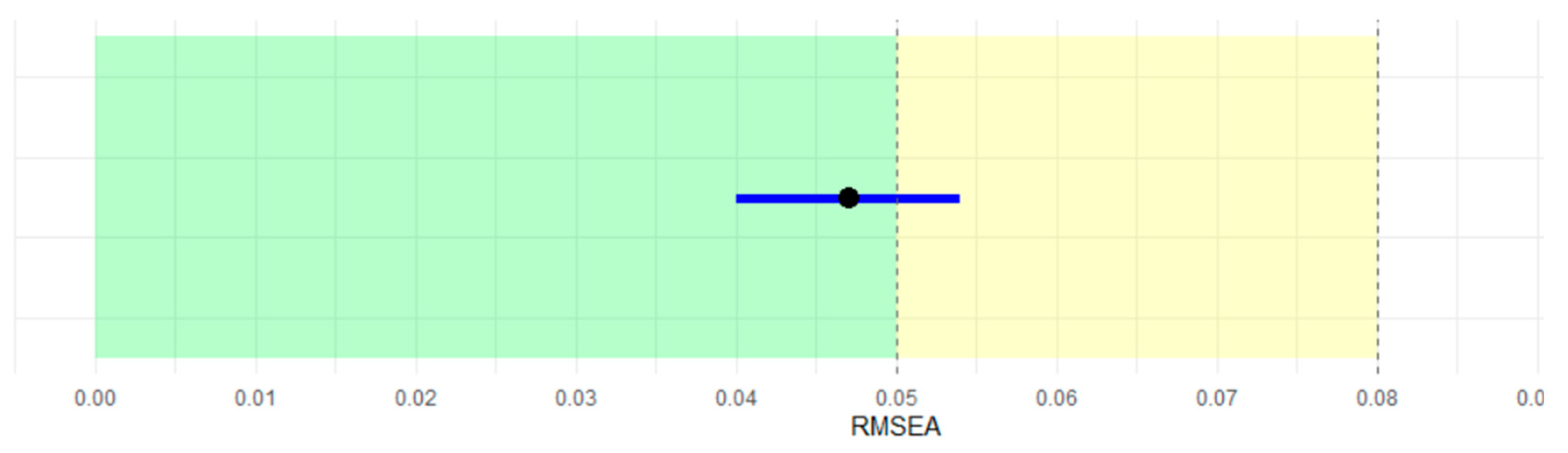

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3. Reliability

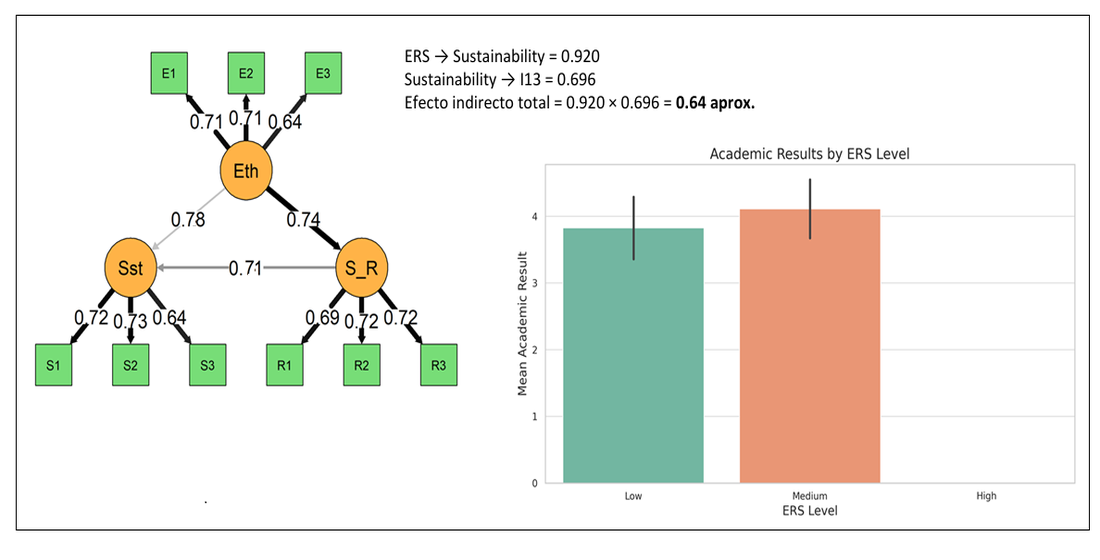

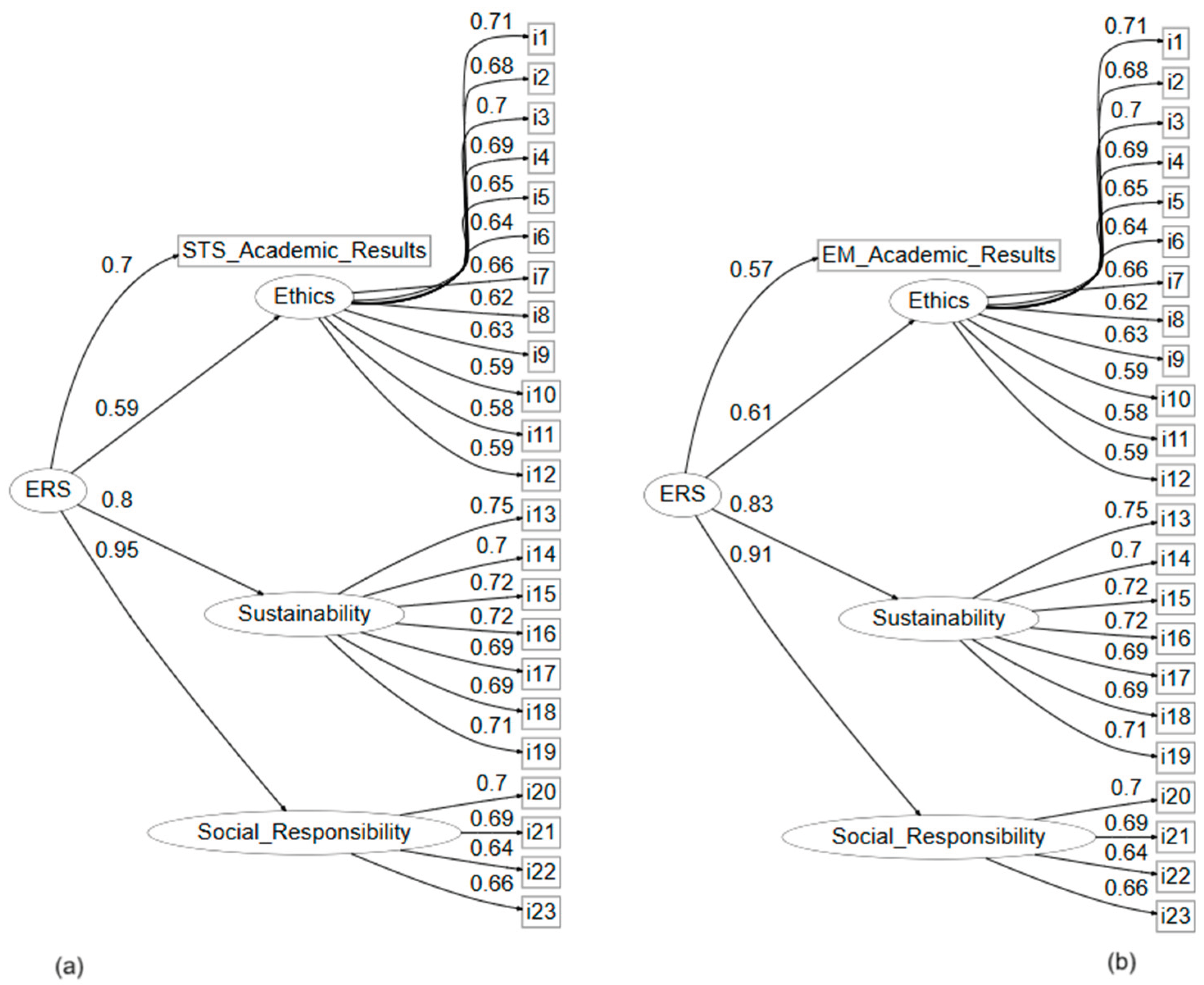

3.4. Integration of Academic Performance into the Structural Model

| Model | X2 | df | X2/ df | TLI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

| (a) | 483.763 | 249.000 | 1.942 | 0.937 | 0.943 | 0.046 | 0.047 |

| (b) | 474.792 | 249.000 | 1.906 | 0.938 | 0.944 | 0.043 | 0.047 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ERS | Ethics, Social Responsibility, and Sustainability |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | confirmatory factor analysis |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

| LO | Lower limit |

| HI | Upper limit |

| CR | Critical Ratio |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

References

- Ma, G.; Shi, W. Promoting Higher Education Sustainability through Teacher Ethics Development: Government Strategies for Action in China. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2024, 12, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albareda-Tiana, S.; Vidal-Raméntol, S.; Pujol-Valls, M.; Fernández-Morilla, M. Holistic Approaches to Develop Sustainability and Research Competencies in Pre-Service Teacher Training. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I. Fundamentación de la metafísica de las costumbres. 1980.

- Branch, W.T.; George, M. Reflection-Based Learning for Professional Ethical Formation. AMA J Ethics 2017, 19, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walshe, N.; Sund, L. Developing (Transformative) Environmental and Sustainability Education in Classroom Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, M. Transformative Education for Sustainable Development: A Faculty Perspective. Environ Dev Sustain 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Lozano, F.J.; Mulder, K.; Huisingh, D.; Waas, T. Advancing Higher Education for Sustainable Development: International Insights and Critical Reflections. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 48, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalėnienė, I.; Pereira, P. Higher Education For Sustainability: A Global Perspective. Geography and Sustainability 2021, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincera, J.; Kroufek ,Roman; and Bogner, F.X. The Perceived Effect of Environmental and Sustainability Education on Environmental Literacy of Czech Teenagers. Environmental Education Research 2023, 29, 1276–1293. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Higher Education, Sustainability, and the Role of Systemic Learning. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability: Problematics, Promise, and Practice; Corcoran, P.B., Wals, A.E.J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2004; pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-0-306-48515-2. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L.; Manolas, E.; Pace, P. The Future We Want: Key Issues on Sustainable Development in Higher Education after Rio and the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2015, 16, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkogkidis, V.; Dacre, N. Exploratory Learning Environments for Responsible Management Education Using Lego Serious Play 2020.

- Mantilla-Crespo, P.; Armijos-Robles, D.; Revilla, L. Gestión escolar con enfoque inclusivo a nivel macro, meso y microcurricular: Experiencias de un estudio de caso. RECIE. Revista Caribeña de Investigación Educativa 2024, 8, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ríos, D.; Ramírez-Malule, H.; Marriaga-Cabrales, N. Mesocurriculum Modernization of a Chemical Engineering Program: The Case of a High-Impact Regional University in Colombia. Education for Chemical Engineers 2023, 44, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, S.M.; Montes, W.F.; Herrera, A. Diagnostic Evaluation of the Contribution of Complementary Training Subjects in the Self-Perception of Competencies in Ethics, Social Responsibility, and Sustainability in Engineering Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V.L. The Role of Transformation in Learning and Education for Sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring the Student Teachers’ Views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R. Framing Student Engagement in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education 2013, 38, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkatsas, A. (Tasos); Kasimatis, K.; Gialamas, V. Learning Secondary Mathematics with Technology: Exploring the Complex Interrelationship between Students’ Attitudes, Engagement, Gender and Achievement. Computers & Education 2009, 52, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Practice 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P. Service-Learning as a Teaching Strategy for the Promotion of Sustainability. In The Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Education and Thinking for the 21st Century; Routledge India, 2025 ISBN 978-1-00-317157-7.

- Alfirević, N.; Stanke, K.M.; Santoboni, F.; Curcio, G. The Roles of Professional Socialization and Higher Education Context in Prosocial and Pro-Environmental Attitudes of Social Science and Humanities versus Business Students in Italy and Croatia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balawi, S.; Thyagarajan, R.S.; McVay, M.W.; Wright, L.M.; Tsenn, J.N. Implementation Strategy for Infusing Engineering-Specific Ethics into the Mechanical Engineering Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE); October 2024; pp. 1–6.

- Reig-Aleixandre, N.; Ramos, J.M.G.; Maldonado, C. de la C. Formación en la responsabilidad social del profesional en el ámbito universitario. Revista Complutense de Educación 2022, 33, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D.S.; Lee ,Jeonghyun; Borenstein ,Jason; and Zegura, E. The Impact of Community Engagement on Undergraduate Social Responsibility Attitudes. Studies in Higher Education 2024, 49, 1151–1167. [CrossRef]

- Caena, F. Developing a European Framework for the Personal, Social & Learning to Learn Key Competence (LifEComp); JRC Research Reports; Joint Research Centre, 2019;

- Demssie, Y.N.; Wesselink, R.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Mulder, M. Think Outside the European Box: Identifying Sustainability Competencies for a Base of the Pyramid Context. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 221, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPatin, M.; Barrens, S.; Poleacovschi, C.; Vaziri, B.; Spearing, L.; Padgett-Walsh, K.; Feinstein, S.; Rutherford, C.; Nguyen, L.; Faust, K.M. Engineering in a Crisis: Observing Students’ Perceptions of Macroethical Responsibilities during Pandemics and Natural Disasters. Journal of Civil Engineering Education 2023, 149, 04023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolio Domínguez, V.; Pinzón Lizarrága, L. Construcción y Validación de un Instrumento para Evaluar las Características de la Responsabilidad Social Universitaria en Estudiantes Universitarios. Revista internacional de educación para la justicia social (RIEJS) 2019, 8, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebles-Núñez, W.; Cabarcas-Velásquez, M.; Gaspar Hernández-Palma, H. RESPONSABILIDAD SOCIAL: ELEMENTO DE FORMACIÓN EN ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS. | EBSCOhost Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/doi:10.17151%2Frlee.2018.14.1.6?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:doi:10.17151%2Frlee.2018.14.1.6 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 126, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, J.; Botti, M.; Thomas, S. Design, Format, Validity and Reliability of Multiple Choice Questions for Use in Nursing Research and Education. Collegian 2005, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Beaman ,Jay; and Sponarski, C.C. Rethinking Internal Consistency in Cronbach’s Alpha. Leisure Sciences 2017, 39, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Pasca, C.M.; Riman, C.F. Thinking Ethics Differently (Challenges and Opportunities for Engineers Education). Independent Journal of Management & Production 2021, 12, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar, A.Y.; Ward, Y.D.; Ward, J.G. Imbuing Contemporary Engineering Education with Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility Perspectives: PRISMA-Based Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON); May 2024; pp. 1–5.

- Gutierrez-Bucheli, L.; Kidman, G.; Reid, A. Sustainability in Engineering Education: A Review of Learning Outcomes. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 330, 129734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Ed; Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed; Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2016; pp. xvii, 534; ISBN 978-1-4625-2334-4.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan : An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishinski, A. lavaanPlot: Path Diagrams for “Lavaan” Models via “DiagrammeR” 2024.

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research 2024.

- Hogarty, K.Y.; Hines, C.V.; Kromrey, J.D.; Ferron, J.M.; Mumford, K.R. The Quality of Factor Solutions in Exploratory Factor Analysis: The Influence of Sample Size, Communality, and Overdetermination. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2005, 65, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Limited, 2013; ISBN 978-1-292-02190-4.

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychological Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. PARE 2005.

- Artman, G. Power Analysis and Determination of Sample Size for Covariance Structure Modeling. Psychological … 1996.

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. Journal of Applied Psychology 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. The Counseling Psychologist 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Articles 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most from Your Analysis. 2005.

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; 16th ed.; Routledge: New York, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-05676-5.

- Rentería-Vera, J.A.; Hincapi-Montoya, E.M.; Rodríguez-Caro, Y.J.; Vélez-Castaneda, C.K.; Osorio-Vélez, B.E.; Durango-Marín, J.A.; Rentería-Vera, J.A.; Hincapi-Montoya, E.M.; Rodríguez-Caro, Y.J.; Vélez-Castaneda, C.K.; et al. Competencia global para el desarrollo sostenible: una oportunidad para la educación superior. Entramado 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jintalan, J. Sustainability Education and Critical Thinking in Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning: Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction 2025, 17, 453–485. [Google Scholar]

| X2 | df | X2/ df | TLI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | LO 90 | HI 90 |

| 438.021 | 227 | 1.929 | 0.940 | 0.946 | 0.042 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.054 |

| Item | Standardized factor loading | CR | Significance |

| i1 | 0.706 | ||

| i2 | 0.681 | 13.051 | <.001 |

| i3 | 0.697 | 13.347 | <.001 |

| i4 | 0.692 | 13.247 | <.001 |

| i5 | 0.652 | 12.497 | <.001 |

| i6 | 0.642 | 12.315 | <.001 |

| i7 | 0.662 | 12.686 | <.001 |

| i8 | 0.621 | 11.924 | <.001 |

| i9 | 0.627 | 12.033 | <.001 |

| i10 | 0.592 | 11.375 | <.001 |

| i11 | 0.584 | 11.222 | <.001 |

| i12 | 0.589 | 11.326 | <.001 |

| i13 | 0.76 | ||

| i14 | 0.697 | 14.162 | <.001 |

| i15 | 0.723 | 14.742 | <.001 |

| i16 | 0.719 | 14.632 | <.001 |

| i17 | 0.692 | 14.041 | <.001 |

| i18 | 0.687 | 13.94 | <.001 |

| i19 | 0.7 | 14.214 | <.001 |

| i20 | 0.705 | ||

| i21 | 0.695 | 12.011 | <.001 |

| i22 | 0.638 | 11.176 | <.001 |

| i23 | 0.654 | 11.425 | <.001 |

| No | Items | Dimensions |

| i1 | I am willing to accept the consequences of my mistakes in my daily actions. | Ethics |

| i2 | Doing what is right in my daily behavior allows me to be at peace with myself. | |

| i3 | Working with passion is part of my personal fulfillment. | |

| i4 | I convey my own values through my daily actions. | |

| i5 | I consider it worthwhile to accept the risk of making mistakes if it helps improve my performance in my field of study. | |

| I6 | To avoid making mistakes in my career, I must be aware of the limits of my knowledge and skills. | |

| i7 | I consider it essential to take ethical aspects into account in my academic and future professional career. | |

| i8 | Fulfilling my commitments on time is important in my daily conduct. | |

| i9 | I am willing to spend time updating my knowledge on any aspect of my field. | |

| i10 | I should not make important decisions without first considering their consequences. | |

| i11 | For good performance in my career, I cannot limit myself to developing only technical skills. | |

| i12 | Maintaining confidentiality is important in daily practice. | |

| i13 | I recognize the potential of the human and natural resources in my environment for use in sustainable development. | Sustainability |

| i14 | I am capable of imagining and anticipating the impacts of environmental changes on social and economic systems. | |

| i15 | I am aware of the importance of sustainability in society, and I learn from and influence the community in which I live. | |

| i16 | I use resources sustainably to prevent negative impacts on the environment and social and economic systems. | |

| i17 | I create and contribute solutions from a critical and creative perspective on issues of technology and engineering, considering sustainability. | |

| i18 | I analyze situations individually or in groups regarding sustainability and its relationship with society, the environment, and the economy, both locally and globally. | |

| i19 | I am aware of and concerned about local problems and their relationship with national and global factors. | |

| i20 | As a student, I feel I have the tools to contribute to social, political, and economic changes in my environment. | Social Responsibility |

| i21 | As a student, I would like to influence public policies that improve the quality of life for minority groups (race, ethnicity, sexual orientation) and vulnerable groups (children, women, elderly people). | |

| i22 | I believe that my education provides me with tools to monitor public or private programs and initiatives aimed at social transformation. | |

| i23 | I believe that through my professional practice I can contribute to reducing poverty and inequality in my region. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).