Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of Related Literature and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptualization of Graduates’ Competence Development

2.2. Theoretical Framework

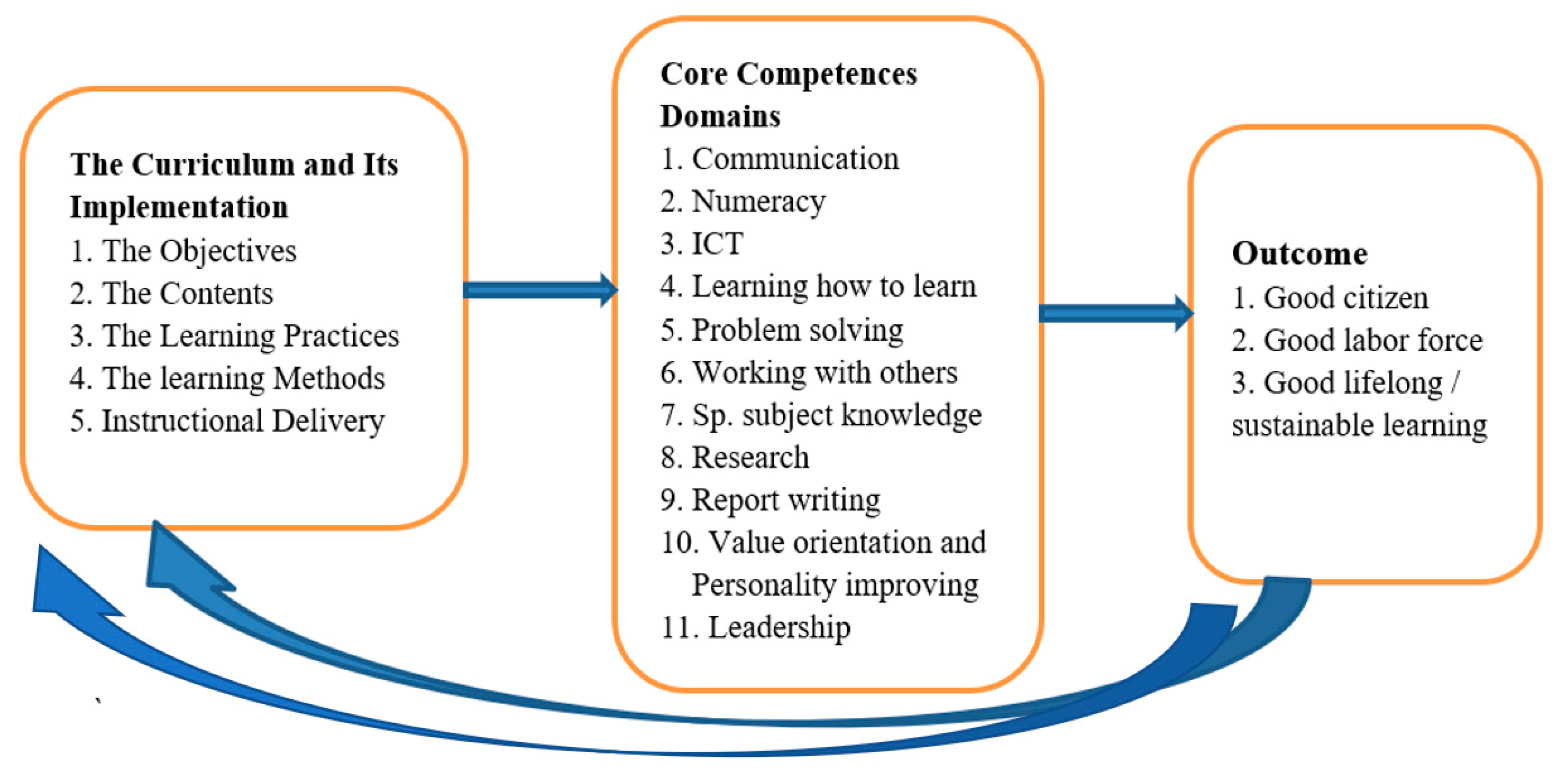

2.2.1. The Curriculum and Its Implementation in Universities Match with Core Competencies

2.2.2. Graduates’ Core Competencies Description

- Communication Skills: The skill that allows graduates to convey their idea as an individual or as a group member and to include a variety of backgrounds in order to reach a good decision, solution, and negotiation (Chauhan, Begum & Saiyad, 2023)). Communication skills mean one’s ability to apply active listening, writing skills, oral communication, presentation skills, questioning, and feedback skills to achieve effective communication (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003; Washer, 2007; and Jones, 2009).

- Numeracy: Numeracy is one of the core competence domains that are essential for conducting clinical research. Numeracy refers to the ability to use and understand numbers, data, and mathematical concepts in various contexts and situations (Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). Numeracy skills include calculating, interpreting, analyzing, and presenting quantitative information. Numeracy is important for designing, conducting, and evaluating clinical trials, as well as for communicating the results and implications of the research. Numeracy can also help researchers critically appraise the quality and validity of existing evidence and apply it to their own practice (Washer, 2007).

- Information Technology: Information technology is one of the core competence domains that are essential for many professions and fields of study. Information technology refers to the use and development of computer systems, software, networks, and devices to create, store, process, and communicate information. Information technology skills include the ability to use various hardware and software tools, such as operating systems, applications, databases, programming languages, web design, cyber-security, and cloud computing (SQA, 2003; Washer, 2007). Information technology is important for enhancing productivity, efficiency, innovation, and collaboration in various domains and contexts. Information technology can also help professionals and learners to access, analyze, and evaluate information from various sources and to create and share knowledge (Hadiyanto, 2010).

- Learning how to learn: Learning how to learn is a core competence domain that involves the ability to seek, acquire, retain, and apply knowledge and skills in various contexts (Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to understand how one learns best and to use effective strategies and techniques to enhance one’s own learning process. Learning how to learn can help one achieve personal, academic, and professional goals, as well as adapt to changing situations and challenges (European Commission, 2018; QCA, 2002).

- Problem Solving: Problem solving is a core competence domain that involves the ability of the individual, group, or nation to think in depth and perform well to achieve a goal by overcoming obstacles using various unusual strategies and techniques (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003; Dunne,;Bennett, & Carre, 2000; Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohamad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to analyze a problem, identify its cause, and evaluate and select the best solution. Problem solving is a frequent part of most activities, as humans exert control over their environment through solutions. Problem solving can be applied to simple personal tasks or complex issues in business and technical fields.

- Working with Others: Working with Others is a core competence domain that involves the ability to effectively interact, cooperate, collaborate, and manage conflicts with other people in order to complete tasks and achieve shared goals (QCA, 2002; Washer, 2007; Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al., 2006). It is also the ability to understand and work within a team or organization’s culture, rules, and values (QCA, 2002; SQA, 2003). Working with others requires many skills, such as communication, conflict management, consensus building, problem solving, decision-making, and respect for diversity.

- Subject-Specific Competencies: Subject-Specific Competencies is a core competence domain that involves the knowledge of theories, concepts, and techniques as well as their application to specific fields (Chauhan, Begum, & Saiyad, 2023). It is also the ability to demonstrate proficiency and excellence in one’s chosen subject area. Subject-specific competenciess are essential for academic and professional success, as they enable one to master the content and methods of a discipline, and contribute to its advancement (Washer, 2007)

-

Research Competence: Research competence is one of the core competence domains that are essential for conducting and disseminating high-quality research in any field (Ciraso-Calí et al., 2022). According to the European Commission, (2018), research competence is defined as "the ability to create new scientific and technological knowledge, products, processes, methods and systems, and to design and manage complex projects and research activities in a systematic and ethical manner" (Yu et al 2020). Research competence can be divided into seven sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Yu et al., 2020; Jamieson & Saunders, 2020). These are: (1) Cognitive abilities: the ability to apply critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, and analytical skills to research problems; (2) Doing research: the ability to design, plan, implement, and evaluate research projects using appropriate methods, tools, and techniques. (3) Managing research: the ability to manage research activities, resources, data, and risks in compliance with ethical and legal standards and regulations. (4) Managing research tools: the ability to use and develop research tools, such as software, hardware, databases, and instruments, to support research processes and outputs; (5) Making an impact: the ability to communicate, disseminate, and exploit research results, and to foster innovation and social change through research. (6) Working with others: the ability to collaborate and network with other researchers, stakeholders, and users and to respect diversity and intercultural differences; (7) Self-management: the ability to manage one’s own professional development, learning, and well-being, and to cope with uncertainty and ambiguity in research.Research competence can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice (Rao, 2013, Ciraso-Calí et al., 2022). Some examples of activities that can enhance research competence are: participating in research projects, workshops, seminars, and conferences; Reading and reviewing scientific literature and publications; writing and publishing research papers, reports, and proposals; applying for research grants and funding; Engaging in peer review and feedback processes; developing and maintaining a research portfolio and a personal research plan; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other researchers; exploring and exploiting research opportunities and collaborations; using and creating research tools and platforms; Communicating and disseminating research findings and implications to various audiences and media; Translating and applying research knowledge and skills to real-world problems and contexts.

-

Report writing skills: Report writing skills are one of the core competence domains that are essential for creating and presenting high-quality reports in any field. Report writing skills are “abilities that help professionals write brief documents about a topic." These skills are applicable for several jobs that may require writing, editing, and researching(Cer, 2019; Kim, Yang, Reyes & Conner, 2021). To write an effective report, one should identify the readers, define the scope, craft a thesis statement, group information logically, use headings, bullets, charts, photos, and other tools, write an enticing introduction and a compelling conclusion, and apply the rules of Standard English. The report should adhere to the specifications of the report brief analyze relevant information, structure material in a coherent order, present in a consistent manner, and draw appropriate conclusions.Report-writing skills can be divided into five sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Graham, & Alves, 2021). These are: (1) Research: the ability to find, evaluate, and use relevant and reliable sources and data to support the report topic and purpose. (2) Planning: the ability to organize the report content and structure and to create an outline and a timeline for the writing process. (3) Writing: the ability to communicate effectively with words, using clear and concise language, appropriate tone and style, and correct grammar and spelling. (4) Visual aids: the ability to use and create charts, tables, graphs, and other visual elements to illustrate and enhance the report content and message. (5) Editing and revising: the ability to review and improve the report draft, checking for accuracy, clarity, coherence, and consistency, and incorporating feedback from others.Report-writing skills can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice. Some examples of activities that can enhance report-writing skills are: Reading and reviewing examples of reports from different fields and purposes Writing and publishing reports for different audiences and contexts, such as academic, professional, or personal. Applying for report writing grants and awards; participating in report writing competitions and challenges; Engaging in peer review and feedback processes, both as a reviewer and a writer; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other report writers, such as mentors, tutors, or colleagues; and Exploring and exploiting report writing opportunities and collaborations, such as online platforms, communities, or networks (Solomon et al., 2021; Chauhan, Begum & Saiyad, 2023).

-

Value-semantic orientation and personality improvement competence: Value-semantic and personality improvement competence is one of the core competence domains that is essential for developing and enhancing one’s personal values, meanings, and goals in life. According to Epanchintseva, Bukhtiyarova, & Panich (2021), value semantic and personality improvement competence is defined as "the ability to form and realize one’s own value-semantic orientations, to overcome value-semantic barriers and conflicts, to achieve personal growth and self-actualization."Value, semantics, and personality improvement competence can be divided into four sub-areas, each with its own set of learning outcomes and proficiency levels (Madin et al., 2022; Nikolenko et al., 2020). These are: (1) Value awareness: the ability to identify, understand, and appreciate one’s own and others’ values, beliefs, and motivations, and to recognize how they influence one’s behaviour and choices. (2) Value development: the ability to critically evaluate, revise, and create one’s own value system and to align one’s actions and goals with one’s values. (3) Value communication: the ability to express, share, and negotiate one’s values with others and to respect and tolerate different value perspectives and worldviews. (4) Value integration: the ability to integrate one’s values into one’s personality, identity, and life purpose and to achieve harmony and balance between one’s values and one’s environment.Value-semantic and personality-improvement competence can be developed through various means, such as formal education, training, mentoring, and practice. Some examples of activities that can enhance value-semantic and personality-improvement competence are: Reading and reflecting on philosophical, ethical, and spiritual texts and literature; Writing and presenting essays, speeches, and stories about one’s values and life experiences; Participating in value clarification and value education programmes and workshops; Engaging in self-assessment and feedback processes, such as personality tests, value inventories, and coaching sessions; Seeking and providing guidance and support from and to other value seekers, such as mentors, counsellors, or engineers, Exploring and exploiting value-added semantic and personality improvement opportunities and collaborations, such as online platforms, communities, or networks, Grit and perseverance, self-control, motivation and goal setting, and personal identity development are also part of this core competence domain.

-

Leadership competence: is one of the core competency domains for graduates’ competence development in universities. Leadership is the ability to guide, influence, and inspires others to accomplish tasks and achieve a common goal. Leadership competencies are the specific skills and attributes that make a graduate an effective leader (Kragt & Day, 2020). Some of the leadership competencies that are important for graduates to develop are: (1) Integrity: This is the quality of being honest, ethical, and consistent in one’s actions and decisions. Integrity helps leaders build trust and credibility with their followers, peers, and stakeholders. Leaders with integrity uphold the values and beliefs of their organization, admit their mistakes, and prioritize the well-being of others. (2) Self-discipline: This is the ability to control one’s emotions, impulses, and behaviors, and to overcome any personal challenges. Self-discipline helps leaders to focus on their goals, manage their time and energy, and commit to self-improvement. Leaders with self-discipline are aware of their strengths and areas for development and seek out feedback and opportunities to learn. The foundation on behalf of the entire set of leadership competencies is good self-leadership. (3) Empowerment: This is the ability to delegate authority and responsibility to others and to support them in achieving their potential. Empowerment helps leaders foster a culture of collaboration, innovation, and accountability. Leaders who empower others encourage them to self-organize, promote connection and belonging, and provide them with the resources and guidance they need. (4) Experimentation: This is the ability to embrace change, uncertainty, and ambiguity and to try new ideas and approaches. Experimentation helps leaders to adapt to the changing environment, solve problems creatively, and learn from failures. Leaders who experiment are open to feedback, willing to take risks, and committed to the professional and intellectual growth of themselves and others. (5)Teamwork: This is the ability to form and organize small supplementary and complimentary groups with delegating specified authority and responsibility for accomplishing the assigned tasks or innovative initiatives and achieving their goals that leads the organization or the nation towards competitiveness and success. Leaders need to have the skill of working with others while maintaining respect, dignity, transparency, participation, openness, and being people-oriented. (6) Project management: This is the ability of the leader to plan, organize, direct, staff, coordinate, review, and budget strategic initiatives with large or small-scale investments within the organization or nationwide. Risk-taking and handling various source conflicts in the process of project design, implementation, and evaluation of outcomes are also crucial competencies of leadership and project managers.Developing the eleven core competencies in the classroom and outside the classroom will help students become more effective and independent learners during their studies, as well as enhance their employment prospects upon graduation. As a result, the graduate of a university comes out with three major outcomes: employability, life-long learning, and good citizenship (QCA, 2002; Hadiyanto, 2006; Star & Hamer, 2007; Washer, 2007).

2.2.3. Desired Outcomes of the Model in the Nation and the World

3. Design and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Sources of the Study

3.3. Sampling Techniques and Sample size determination

3.3.1. Interviewees

3.3.2. Tracer Study Finding Exhibits

3.3.3. University Exit-Exam Result Exhibits

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. Interviews

3.4.2. Document Analysis

3.4.3. Exit exam results

3.5. Analysis Techniques

4. Findings

4.1. Examining the Quality Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competences Domain Development

To me it is died. …Because I believe that the quality status of our graduates are below our expectations or standards such as: They lack future oriented thinking so that they showed limitation in terms of maintaining nature, shortage of preserving social values and wisdom for upcoming generation. Our college instructions did not significantly promote the connection between local and global events (values). Our instruction focus on lecturing and memorizing rather than searching and finding the new wisdom, Graduates lack critical and creative thinking to solve problems with in the institution and the community. Internship and practicum field works and their feedbacks were not genuinely well practiced, in the last 5 years (9 April 2022, 0:20).

Habtu M. further noted in the interview report as follow:

The poor quality of graduates may have some degree of association with the status of inputs used in graduates’ production process such as instructors’ and students’ identity(capacity, competence, interest…), instructional technology and infrastructure availability, Moreover, the production system or the process part such as instruction, curriculum, program management, internship fieldworks, practicum and other feedbacks have also considerable influence on the quality of the graduates in our college (9 April 2022, 0:20).

4.2. University Exit-Exam Results as Indicator of Graduates’ Competence Development

Interpretation

4.3. Quality Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competence Domains

| Core competencies from the adapted model | Academics’ interview | Graduates’ interview | Employers’ interview | Kerebih et al, 2020 Tr. Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graduates rating | Employer view | Emp. sati sfaction | ||||

| Communication skill | Very good | Very good | Very good | 67 | 82 | 62 |

| Numeracy skill | Good | Good | Good | - | 80 | 59 |

| IT skill | Good | Good | Good | - | 76 | 58 |

| Learning how to learn | Good | Good | Good | - | 79 | - |

| Problem solving skills | Good | Good | Good | 68 | 81 | 59 |

| Working with others | Very good | Good | Very good | 76 | 85 | 63 |

| Subject specific knowledge and skill | Very good | Very good | Very good | 78 | 84 | 63 |

| Research and innovation skill | Satisfactory | satisfactory | Good | 69, 64 | 79 | 60 |

| Report writing and presentation skill | Good | Good | Good | 74 | 80 | 60 |

| Value-semantic and personality improving skill |

Satisfactory | Good | Good | 71 | 83 | 63 |

| Leadership competence | Satisfactory | Good | Good | 69 | 79 | 59 |

| Grand | Good-+ | Good+ | Good+ | 72 | 80 | 60 |

4.4. Major Causes for the Identified Statuses of Graduates’ Core Competence Domains

4.4.1. Practice versus Theory Based Training

4.4.2. Leadership quality

4.4.3. External Environmental Influence

4.4.4. Employers’ Recruitment Problems

4.4.5. Instructional Variable Problems: (the graduates themselves, academics’ competence, program and curriculum relevance, resource and budget deficiency)

5. Conclusions and recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

- The quality statuses of graduates’ competence developments in various competence domains across colleges shall be investigated regularly in the college or institutional level so that interventions shall be given accordingly.

- The top level leaders shall give the desired attention to the faculties relative to the three colleges in terms of budget and other supports needed.

- Whatever leadership theory or style the deans (leaders) followed, leaders’ leadership behavior practice and the control of the leadership contingent contexts (justice, culture, …) shall develop relatively shared identity to adequately direct the staff and students effort toward achieving desired common goal (quality of graduates’ core competences development).

- College instructions shall be improved towards equal attention to both theory and practice and also focus on core competences domains more demanded by employers such as teamwork skills, innovative ability, research skills, problem solving skill, critical thinking, field specific subject matter knowledge, generic skills … School of medicine can be taken as best practices that shall be shared for other colleges

- The external environment influence especially the political context influence in terms of ethnic group conflicts and wars created security problems for universities even some universities were closed their regular teaching learning process. Therefore, the government shall alleviate ethnic concerns and build peace and security for affected universities.

- Employers both government and private shall recruit candidates based on genuine and fair selection criteria free from biasedness, and merit based employment shall be reinforced.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Clearance Approval

References

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita DSeabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate employability and competence development in higher education—A systematic literature review using PRISMA. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- An, B.P.; Loes, C.N. Participation in High-Impact Practices: Considering the Role of Institutional Context and a Person-Centered Approach. Res High Educ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Billet, S. Integrating Practice-Based Experiences into Higher Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, S. Towards competence-oriented higher education: a systematic literature review of the different perspectives on successful exit profiles; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cer, E. The instruction of writing strategies: The effect of the metacognitive strategy on the writing skills of pupils in secondary education; SAGE Open, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraso-Calí, A.; Martínez-Fernández, J.R.; París-Mañas, G.; Sánchez-Martí, A.; García-Ravidá, L.B. The Research competence: acquisition and development among undergraduates in Education Sciences. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 836165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Begum, J.; Saiyad, S. Validated checklist for assessing communication skills in undergraduate medical students: bridging the gap for effective doctor-patient intera-ctions. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2023, 47, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CRSC [Core Renewal Steering Committee]. Learning Outcomes for the University Core Curriculum: Final Report; Loyola University: Chicago, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Croswell, J. W. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th ed.; Sage publications Inc.:: Los Angeles, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, M; Jele, A.; Major, Z.B. The model of maximum productivity for research universities SciVal author ranks, productivity, university rankings, and their implications. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 4335–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; De Hauw, S. Linking competency development to career success: exploring the mediating role of employability, Vlerick Leuven Gent Working Paper Series, 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.

- Divine, R.; Linrud, J.; Miller RWilson, J.H. Required internship programs in, marketing: Benefits, challenges and determinants of fit. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2007, 17, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, E.; Bennett, N.; Carre, C. Skill Development in Higher Education and Employment. In Differing Visions of Learning Society; Coffield, F., Ed.; Bristol: Policy Press: 2000.

- Ekmekcioglu, W.E.B.; Aydintan, B.; Celebi, M. The effect of charismatic leadership on coordinated teamwork: A Study in Turkey. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epanchintseva, G.; Bukhtiyarova, I.; Panich, N. Comparative Analysis of Perfectionism and Value-Semantic Barriers of the Student's Personality. TEM Journal 2021, 10, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Alves, R.A. Research and teaching writing. Reading and Writing 2021, 34, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; de Jesus Gomes, M.; da Cunha Moniz, A.; Américo, J.; Afonso, A.; Marçal, J. A Study of the Attribute of Graduates and Employer Satisfaction—A Structured Elements Approach to Competence and Loyalty. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies 2023, 11, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, L.I.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Components of Education 4.0 in 21st Century Skills Frameworks: Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwill, A.M.; Shen-Hsing, A.C. Embracing a culture of lifelong learning: the science of lifelong learning. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.

- Gürbüz, S.; van Woerkom, M.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Demerouti, E.; van der Klink, J.J.L.; Brouwers, E.P.M. Employable until Retirement: How Inclusive Leadership and HR Practices Can Foster Sustainable Employability through Strengths Use. Sustainability 2021, 14, 12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiyanto, H. The Development of Core Competencies at Higher Education: A Suggestion Model for Universities in Indonesia. EDUCARE: International Journal for Educational Studies 2010, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Haile, M.; Zeleke, S.A.; Petros, K.D.; Sifelig, T.N.; Aragaw, M.M. Analysis of supply side factors influencing employability of new graduates: A tracer study of Bahir Dar University graduates. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability 2019, 10, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, L.; Moon, S.; Geall, V.; Bower, R. Graduates' work: Organisational change and students' attributes; Centre for Research into Quality: Birmingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T. The meanings of competency. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1999, 23, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibreck, Rachel & Alex, de Waal. Introduction: Situating Ethiopia in genocide debates. Journal of genocide research 2022, 24, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Saunders, M.V. Contextual framework for developing research competence: Piloting a validated classroom model. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones Anna. Re-Disciplining Generic Attributes: The Disciplinary Context in Focus. Journal of Studies in Higher Education 2009, 34, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Yang, D.; Reyes, M.; Connor, C. Writing instruction improves students’ writing skills differentially depending on focal instruction and children: A meta-analysis for primary grade students. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kragt, k.; Day, D.V. Predicting leadership competency development and promotion among high-potential executives: The roleof leader identity. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerebih, A.; Haile, M.; Zeleke, S.; Melaku, M.; Petros, K.; Sifelig, T. Graduate tracer study of regular undergraduate students of Bahir Dar university, graduated on 2016/17 and 2017/18, Unpublished doc. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, P.; Yorke, M. Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2003; ISBN 020346527X. [Google Scholar]

- Kumilachew S., A.; Gubaye A., A.; Mohammed S., A.; Abebe, D.D. The Causes of Blood Feud in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. African Studies, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Laker, D.; Powell, J. The differences between hard and soft skills and their relative impact on training transfer. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2011, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, YS. & Guba, EG. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA.

- Liu, H.; Chu, W.; Fang, F.; Elyas, T. Examining the professional quality of experienced EFL teachers for their sustainable career trajectories in rural areas in China. Sustainability 2021, (13), 10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Louis, K. S.; Anderson, S. & Wahlstrom, K. (2004) How leadership influences student learning: Review of research, Carei Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, Minnesota, USA. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234667370.

- Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Wahlstrom, K., Anderson, S., Mascall, B. & Gordon, M. (2010) How Successful Leadership Influences Student Learning: The Second Installment of a Longer Story. Springer International Handbooks of Education 23. [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, A.; Capone, V.; Aversano, A.; Akkermans, J. Career competencies and career success: on the roles of employability activities and academic satisfaction during the school-to-work transition. Journal of Career Development 2022, 49, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madin, Z.; Aizhana, A.; Nurgul, S.; Alma, Y.; Nursultan, S.; Ahmed, A. A.; Mengesha, R.W. (2022). Stimulating the professional and personal self-development of future teachers in the context of value-semantic orientation. [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, S.; Pouliakas, K.; Redmond, P. (2017) How Useful is the Concept of Skills Mismatch? Geneva, International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_552798.pdf.

- Ministry of Education(MoE) (2018) Ethiopian education development road map. 2018-2030. AddisAbaba (un published doc).

- Mucinskas, D., Biller, M., Wajda, H., Gardner, H., & Yuen, D. (2023). Navigating Changes Successfully at Work: The Development of a Course about Unlearning and Good Work for Adult Learners. Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

- Nikolenko, Oksana; Zheldochenko, Lyudmila; Lomova, Natalia; Rudoy, D.; Ignateva, S. Psychological and pedagogical conditions for the formation of value-semantic sphere of students of technical specialties. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 175, 15029. [CrossRef]

- Nikusekela, N., & Pallangyo, E. (2016). Analysis of supply side factors influencing employability of fresh higher learning graduates in Tanzania. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research.

- Ngulube, P. (2015). Qualitative data analysis and interpretation: Systematic search for meaning, in Mathipa, ER & Gumbo, MT (edrs). Addressing research challenges; Making headway for developing researchers. Mosala MASEDI publishers & Booksellers cc. Noordywk PP.131-156.

- QCA [Qualifications and Curriculum Authority]. Key Skills for Developing Employability. London 2002.

- Rao, M.S. Smart leadership blends hard and soft skills: … and emphasizes the importance of continuous learning. Human Resource Management International Digest 2013, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, T.; Rojas, R. College of education graduate tracer study (GTS): Boon or bne? European Scientific Journal, ESJ 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römgens, I.; Scoupe, R.; Beausaert, S. Unraveling the concept of employability, bringing together research on employability in higher education and the workplace. Stud. High. Educ. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.; Heimler, R.; Morote, E. Basic employability skills: A triangular design approach. Education+ Training 2012, 54, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D.S.; Salganik, L.H. Key competencies for a successful life and a well-functioning society; OECD definitions and selection competencies final report; Hogrefe & Huber: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Semela, T. Breakneck expansion and quality assurance in Ethiopian higher education: Ideological rationales and economic impediments. Higher Education Policy 2011, 24, 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. K.; Sharma, R.C. Innovation framework for excellence in higher education institutions. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management (June 2021) 2021, 22, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SQA [Scottish Qualifications Authority]. “Key Competencies: Some International Comparisons in Policy and Research” in Research Bulletin, 2. 2003. Available online: http://www.sqa.org.uk/files_ccc/ Key_Competencies.pdf. [accessed January 2023]. 20 January.

- Star, Cassandra & Sara Hammer. Teaching generic skills: eroding the higher purpose of universities or an opportunity for renewal? Oxford Review of Education 2007, 34, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Stoof, A.; Martens, R.I.; Van Merrienboer, J.J.G.; Basteiaens, T.J. The boundary approach of competence. A constructivist aid for understanding and using the concept of competence. Hum. Resour. Dev.Reu. 2002, 1, 345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, M.; Burkholder, G.J.; Solberg, E.; Stellmack, A.; Presson, W.; Seitz, J. development and validation of a global competency framework for preparing new graduates for early career professional roles. Higher Learning Research Communications 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling-Lang, T.; Yin-Lan, Y. Effect of Organizational Culture, Leadership Style, and Organizational Learning on Organizational Innovation and performance in the Public Sector. Journal of Quality 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekeste Negash. The crisis of Ethiopian Education. Implications for nation building, Uppsala University: Uppsal Education Report No. 29. 1990.

- Tekeste Negash. Rethinking education in Ethiopia, 1996.

- Ur-Rahman, S.; Bhatti, A.; Chaudhry, N.I. Mediating effect of innovative culture and organizational learning between leadership styles at third-order and organizational performance in Malaysian SMEs. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washer Peter. Revisiting Key Skills: A Practical Framework for Higher Education. Journal of Quality in Higher Education 2007, 13, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westera, W. Competences in education: A confusion of tongues. J. Curric. Stud. 2001, 33, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittorski, R. Professionalization and the development of competences in education and training; Coen-Scali, V., Ed; Barbara Budrich Publisher: Opladen/Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yorke, M. Employability in higher education: What it is, What it is not; learning & employability series; Higher Education Academy (HEA): Heslington, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in organizations, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Newjersy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zalizan Mohammad Jelas et al. “Developing Core Competencies at Graduates: A Study of Effective Higher Education Practices in Malaysian Universities” in Summary Report. Kuala Lumpur:Faculty of Education UKM [Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia]. 2006.

- Zangoueinezhad, A.; Moshabaki, A. Measuring university performance using knowledge based balanced scorecard. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2011, 60, 824–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleke, S.; Tiruneh, A.; Mandefro, M.; Teramaj, W. A tracer study on employability of business and economics graduates at Bahr-Dar university. Int. J. High. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 2, PP45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, S.-G.; Zhao, Y.-N.; Cao, X.-Y. Analyzing Core Competencies and Correlation Paths of Emerging Engineering Talent in the Construction Industry: An Integrated ISM–MICMAC Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Human capital, institutional quality and industrial upgrading: global insights from industrial data. Economic Change and Restructuring, Springer 2016, 51, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A. Hospitality internships in Cyprus: A genuine academic experience or a continuing frustration? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2007, 19, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| College/Faulty | Mean | Below 35 % | 35-49 % | 50-69 % | 70-84 % | 85-100 % | Passed | Failed | Total | % passed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMHS | 75.22 | 0 | 0 | 23(19.82) | 86(74.14) | 7(6.03) | 116 | 0 | 116 | 100% |

| CAES | 65.92 | 0 | 10 (17.3) | 84(55.62) | 54(35.76) | 3(1.99) | 141 | 10 | 151 | 93.38% |

| CS | 69.013 | 2(1.2) | 7(4.1) | 68(40) | 80(47.1) | 13(7.6) | 161 | 9 | 170 | 94.7% |

| FSS | 61.65 | 2(0.7) | 32(11.22) | 178(62.5) | 73(25.6) | 0 | 251 | 34 | 285 | 88.1% |

| FH | 62.59 | 4(2.4) | 45(26.8) | 53(31.6) | 49(29.17) | 17(10.1) | 119 | 49 | 168 | 70.83% |

| Total | 66.87 | 8(0.8) | 94(10.54) | 406(45.56) | 342(38.38) | 40(4.49) | 788 | 103 | 891 | 88.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).