1. Introduction

In the contemporary era, humanity is confronted with complex and multidimensional crises, including climate change, the spread of infectious diseases, population aging, and digital inequality. These global challenges cannot be adequately addressed through responses from a single academic discipline or individual nation-state. Rather, they necessitate a new kind of human capital—individuals who can comprehend the contextual complexity of such issues and explore creative yet ethically grounded solutions. In this context, it is increasingly required that higher education transcends the traditional role of knowledge transmission and adopts transformative learning approaches that empower students to envision and actively engage with uncertain futures [

1].

With the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) gaining prominence as a central global agenda, higher education is undergoing a paradigmatic shift. This shift moves beyond mere problem recognition or theoretical instruction toward cultivating competencies that enable students to collaboratively shape sustainable futures. The term “futures” here implies a plurality of possibilities, encompassing diverse trajectories, values, and choices [

2]. Navigating such plural futures requires convergence thinking and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Against this backdrop, convergence education has emerged as a strategic response to the complexity and uncertainty of future societies. This educational approach integrates knowledge, skills, and attitudes across disciplinary boundaries, fostering the capacity to generate innovative solutions to real-world problems [

3,

4,

5]. Particularly, global challenges such as sustainability entail structural dilemmas that cannot be resolved by single disciplines or technologies alone, necessitating an integrative understanding that spans social, cultural, ethical, environmental, and economic dimensions.

Research on competencies for sustainability has grown considerably in recent years. Researchers [

6] have identified systems thinking, strategic thinking, values orientation, collaboration, and self-reflection as core sustainability competencies. Brundiers et al. [

7] further emphasized the need for interdisciplinary curriculum design that enables the integration of such competencies within authentic educational contexts. However, existing research on convergence competencies has been predominantly focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), with limited attention given to their conceptualization and assessment within Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (HASS) education.

HASS disciplines offer deep insights into human experiences and social contexts, cultivating qualities such as ethical reflection, cultural sensitivity, and creative expression—attributes that are closely linked to social sustainability. Nevertheless, the unique contributions of HASS fields have been insufficiently reflected in prevailing models of convergence education or sustainability discourse. In the context of higher education in South Korea, although various convergence initiatives have been implemented, there remains a lack of standardized tools for diagnosing convergence competencies specifically among HASS students and linking them to educational outcomes.

While studies have highlighted the qualitative and philosophical value of HASS-based sustainability education, efforts to operationalize these insights through quantitative assessment tools remain at a nascent stage. Research has mainly focused on course design and instructional cases, and attempts to develop systematic frameworks that support learners’ self-diagnosis and autonomous development remain scarce [

8].

Although the recently implemented Korean education policy increasingly emphasizes convergence education and the cultivation of future-ready talent, there has been limited progress in the development of assessment tools that can measure educational outcomes in this domain. For example, Huh [

9] indicated the challenges of convergence education in engineering, while Padmanabhan [

10] highlighted the need for competency-based assessment in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). However, practical implementation of such tools in higher education remains scarce. This lack of assessment infrastructure inhibits students’ ability to understand their own competencies and plan for growth, while also undermining the institutionalization and quality assurance of convergence education.

This study aims to develop a self-assessment tool for diagnosing convergence competencies among undergraduate students in the HASS fields. The research seeks to address the following questions:

RQ1. What are the core convergence competencies required for university students in the HASS fields to contribute to sustainable futures?

RQ2. How can the identified convergence competencies be structured and validated through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses?

RQ3. To what extent does the developed self-assessment tool validly measure the learning outcomes of convergence education in the HASS disciplines?

This study seeks to make the following academic and societal contributions. First, it complements existing STEM-centric models of convergence competencies by incorporating the unique insights and attributes of the HASS disciplines. Second, it provides a framework for learners to self-assess their competencies and receive formative feedback, thereby supporting self-directed learning. Third, it offers a shared evaluative language for higher education institutions, policy-makers, and industries to advance the diffusion and quality management of convergence education. Finally, it opens pathways for the international application of the tool as a global diagnostic framework aligned with the educational paradigms of convergence and sustainability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Convergence Education for Sustainable Futures: Paradigm Shifts and Competency Demands

As the global community confronts escalating poly-crises—climate change, resource depletion, social polarization, pandemics, etc.—sustainability has emerged as a central imperative for 21st-century education. UNESCO [

1], particularly, emphasizes transformative learning and convergence thinking as key educational approaches for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These pedagogies aim not only to impart functional skills but to cultivate practitioners capable of understanding and addressing interconnected socio-environmental and economic challenges.

Convergence education has thus acquired prominence as a core strategy for preparing students to respond to complex future issues by integrating technological capabilities with human-centered values. Kim and Ryou [

11] emphasized the need to nurture talents equipped with competencies for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, while Choi [

12] argued that globalization and digitalization necessitate a paradigm shift in higher education through convergence-driven qualitative transformation. Hong [

13] further asserted that convergence education is evolving from a focus on general education and character development to an action-oriented pedagogy that fosters the capacity to contribute to a sustainable society rooted in the creative industries. Essentially, convergence education is now being reframed as an educational philosophy that cultivates future-ready individuals capable of designing sustainable futures through an integrated lens of technology, humanities, society, and the environment.

Technological innovation alone cannot achieve a sustainable future. While advancements in artificial intelligence, big data, the Internet of Things (IoT), and robotics have opened new frontiers, they have also generated structural issues such as social inequality, labor market instability, and ecological degradation. To address such multifaceted problems, a broader set of competencies is required, including social responsibility, environmental sensitivity, ethical reasoning, and inclusivity. The transition to a knowledge-based, information-driven economy necessitates not only creativity and innovation but also the ability to critically interpret data and translate it into socially meaningful outcomes. Moreover, the ongoing transformation into multicultural and inclusive societies further accentuates the need for competencies rooted in social sustainability, diversity, and coexistence. These developments call for a fundamental reconfiguration not only of pedagogical methods but also of the values and goals that education itself should pursue.

Reports by the World Economic Forum (WEF) [

14,

15] have illustrated the evolving competencies required for the future employment landscape. Skills such as complex problem-solving, critical thinking, creativity, leadership, and resilience are not merely technical assets but essential capabilities for sustaining life, organizations, and communities. The 2025 WEF report [

15] presents an expanded competency framework that reaffirms the enduring relevance of human-centric skills—particularly in the context of HASS. It emphasizes the increasing importance of analytical and creative thinking, resilience, flexibility and agility, as well as curiosity and lifelong learning—competencies that align closely with the educational aims of the HASS disciplines. Moreover, leadership and social influence, systems thinking, motivation and self-awareness, and talent management are highlighted as key capabilities required to navigate complex socio-cultural transformations. Taken together, these findings suggest that core competencies for the future must integrate both technological literacy and humanistic values. The convergence of these domains constitutes the foundational attributes of convergence competencies, which are essential for driving sustainable societal transformation.

In response to these global shifts, higher education institutions and evaluation bodies in South Korea have increasingly advocated for competency-based curriculum design and assessment frameworks aligned with the vision of sustainability. While universities have begun restructuring curricular and extracurricular systems accordingly, the development of robust educational models and assessment tools that explicitly link convergence competencies to sustainability remains insufficient.

Historically, discussions on convergence competencies have been rooted in STEM-based education, emphasizing domains such as problem-solving, collaboration, creativity, and systems thinking [

16,

17]. However, there is growing recognition that technology-centric approaches alone are inadequate for resolving social problems, and that perspectives and competencies of HASS are vital components of a new convergence paradigm [

18,

19].

The significance of HASS-based convergence education can be substantiated as a foundational approach to envisioning and designing sustainable futures. First, the integration of emerging technologies—virtual reality, artificial intelligence, mobile learning, etc.—into the HASS fields provides immersive, multisensory learning environments that enhance not only creativity and critical thinking but also cultural sensitivity and human-centered technological literacy [

20]. Second, educational practices such as digital storytelling, 3D modeling, and immersive exhibitions facilitate identity work and civic responsibility, enabling learners to reinterpret cultural heritage and envision ethically grounded futures. Third, as Novis-Deutsch et al. [

21] emphasized, interdisciplinary learning in the humanities goes beyond knowledge building to foster critical subjectivity and the formation of learner identity. This dimension of learning supports ethical engagement with social issues and integrative thinking across disciplines—essential elements for a sustainable societal transition.

Moreover, Amsler and Facer [

22] introduced the concept of unlearning, advocating for a shift in higher education from prediction-based instruction to learning approaches that embrace uncertainty and explore multiple potential futures. In this context, HASS-based education offers a unique space for reflexive and imaginative inquiry, enabling students to experiment with new thought frameworks and cultivate ethical foresight. Although the authors do not directly employ the term “futures literacy,” the competencies they highlight—imagination, reflexivity, and possibility-oriented thinking—closely align with its core principles.

However, existing convergence competency assessment tools have primarily been developed for engineering or interdisciplinary majors, often failing to reflect the distinctive characteristics of HASS learners. While recent studies have proposed models for convergence competencies grounded in art and design, standardized tools that enable self-assessment in the HASS context remain scarce.

2.2. Review of Previous Research on Convergence Competencies

This study aims to develop a self-assessment tool for diagnosing convergence competencies among students in the HASS disciplines. To establish a robust theoretical foundation, previous research related to sustainability education and key competencies was reviewed.

Wiek et al. [

6] proposed a widely recognized framework that defines five essential competencies for sustainability education: systems-thinking, anticipatory (futures-thinking), normative (values-based), strategic, and interpersonal competencies. These competencies enable students to analyze complex socio-ecological systems, envision sustainable futures, make value-laden decisions, plan strategic interventions, and collaborate effectively with diverse actors. Furthermore, they [

6] included integrated problem-solving as a higher-order meta-competency that synthesizes and applies these five in practice. Basic academic skills are regarded as the foundation supporting these competencies.

Building on this, Evans [

23] restructured the Wiek framework into five broader categories: systems competence, critical and normative competence, interpersonal and communication competence, creative and strategic competence, and transdisciplinary competence. This adaptation places greater emphasis on reflexivity, communication, and cross-disciplinary collaboration—elements that align closely with the aims of convergence education in the HASS context.

In parallel, the concept of

Gestaltungskompetenz—a term originating in the German-speaking discourse on sustainability education—provides an expanded view on transformative learning. Introduced by de Haan [

24],

Gestaltungskompetenz refers to the ability to shape and implement solutions to sustainability challenges [

25]. It encompasses 12 sub-competencies including foresight, participation, empathy, and the capacity for self-reflection and decision-making, reinforcing the necessity for learners to actively engage in shaping sustainable futures.

Further refinement is seen in Redman and Wiek [

2], as referenced by Annelin and Boström [

26], who outlined eight core sustainability competencies. These updated models reflect the growing complexity and interdisciplinary nature of sustainability education. Vare et al. [

27] offered another multidimensional framework that includes 12 competencies such as systems thinking, futures thinking, attentiveness, empathy, criticality, responsibility, and decisiveness. These competencies collectively highlight the shift toward learner agency, ethical engagement, and systems-level transformation.

Additionally, Venn et al. [

28], through an action research study with senior sustainability professionals, delineated interpersonal collaboration competency as a core element of sustainability interventions. This includes boundary spanning, stakeholder engagement, building mutual trust, communication, and co-creation. These dimensions not only operationalize the interpersonal domain of Wiek’s framework but also reflect the practical and participatory aspects of convergence competencies in real-world contexts. Taken together, these complementary frameworks provide a comprehensive foundation for defining and assessing convergence competencies, particularly those required for addressing complex societal challenges through interdisciplinary and sustainability-focused education.

3. Materials and Methods

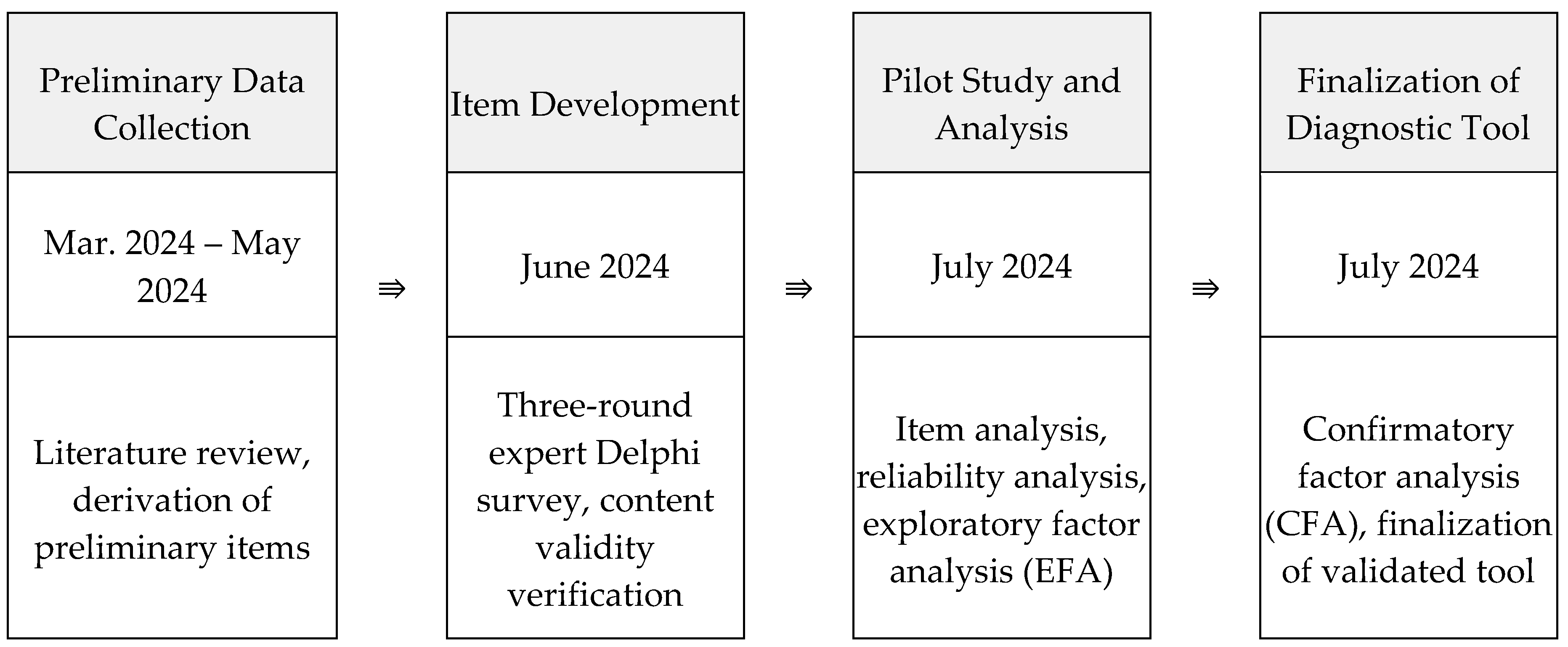

The purpose of this study is to develop and validate a self-assessment tool that diagnoses the core convergence competencies required for cultivating convergence-oriented talent capable of contributing to sustainable futures. A systematic research procedure was established, consisting of:

(1) literature review and conceptual framework development,

(2) item generation,

(3) expert Delphi validation, and

(4) empirical testing and statistical validation.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using a single dataset owing to practical constraints. While this approach provided preliminary evidence for the instrument’s validity, the limitation of using the same sample is acknowledged, and future studies are recommended to perform cross-validation. These procedures are illustrated in

Figure 1 and form the basis of the empirical development of the diagnostic tool.

3.1. Literature Review and Preliminary Item Development

To construct the foundation for item development, a total of 331 documents—including peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations, and policy reports—were collected using core keywords such as sustainability, future education, convergence competencies, convergence talent, and convergence education. After excluding duplicate indicators and instruments, 17 sources were selected for final analysis. Based on these materials, definitions and components of convergence competencies were derived, and preliminary items were developed accordingly.

3.2. Expert Delphi Survey

To ensure the validity and appropriateness of the preliminary items, a three-round Delphi survey was conducted with 10 experts who had extensive experience (over seven years) in developing and managing convergence education programs. These panelists were selected through recommendations from the National Research Foundation of Korea and relevant academic societies. All experts were provided with detailed explanations of the research objectives and consent forms via email and voluntarily agreed to participate.

In the first round, experts reviewed the definition, components, and draft items of convergence competencies and provided qualitative feedback. In the second round, a revised version of the items was reviewed again based on previous feedback. In the third round, the experts evaluated the appropriateness of each item to refine the tool. Content validity was assessed using Lawshe’s [

29] Content Validity Ratio (CVR), and items were retained only if they met the minimum CVR threshold of 0.62 for a panel of 10 experts.

3.3. Pilot Study: Exploratory Factor Analysis and Reliability Testing

Following the Delphi survey, the refined items were subjected to a pilot study conducted during July 10–17, 2024, targeting undergraduate students participating in the second HUSS Convergence Education Program. Of the 774 initial respondents, 455 valid responses were included in the final analysis after excluding incomplete or inattentive responses. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 27.0 to conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to evaluate construct validity and identify the underlying factor structure. Maximum Likelihood extraction was used, with Direct Oblimin rotation applied to account for inter-factor correlations. Internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α for each subdimension.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents were as follows: 27.9% male (n = 127) and 72.1% female (n = 328); by academic year, 19.1% were freshmen, 30.1% sophomores, 31.4% juniors, and 18.9% seniors. Regionally, 42.4% were from the Seoul metropolitan area and 57.6% from non-metropolitan regions.

3.4. Main Study: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Finalization of the Tool

Based on the results of the pilot study, several items were revised or removed. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted using AMOS 24.0 to validate the final version of the diagnostic tool. The model fit and construct validity of each subdimension were examined, and the appropriateness of item loading was assessed. Through this process, the final number of items per component and their corresponding reliability indices were confirmed.

Consequently, the developed diagnostic tool for convergence competencies in future-oriented talent secured both theoretical and psychometric validity. It serves as a practical instrument for quantitatively assessing the outcomes of HASS-based convergence education and provides a foundational resource for program improvement and curriculum design.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted using a non-anonymous online survey designed for curriculum improvement and diagnostic tool development. No sensitive personal information was collected, and individual identification was not possible. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents were informed about the study’s objectives and intended use of data prior to completion of the survey. Accordingly, the study does not fall under the category of clinical or biomedical research requiring Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, and no formal IRB application was submitted.

4. Results

4.1. Synthesis of Previous Research and Derivation of the Diagnostic Tool Framework

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of previous domestic studies on convergence competencies to establish the theoretical foundation for the diagnostic tool developed in this study. Using keywords such as sustainability, future education, convergence competencies, convergence talent, and convergence education, a total of 331 scholarly works—including academic journal articles, dissertations, and policy reports—were collected and reviewed. After eliminating sources that employed identical indicators or duplicate instruments, 17 key studies were selected for detailed analysis.

The selected literature conceptualized convergence competencies as multidimensional constructs encompassing cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains. Common themes included the integration of diverse disciplinary knowledge, collaborative attitudes, practical execution, and responsiveness to future challenges. Based on this synthesis, the present study defines future convergence competency as “the ability to create new value demanded by future society through understanding and integrative thinking across multiple academic domains.” This definition extends beyond mere acquisition of knowledge and emphasizes the creative capacity to traverse disciplinary boundaries, solve complex problems, and generate novel insights. It reflects the essential nature of convergence competency as a core capability in higher education for preparing students to navigate and shape sustainable futures, incorporating both the purpose and praxis of convergence.

The resulting model of future convergence competency is structured into six major domains (competency clusters) and 12 sub-competencies. These were designed to comprehensively represent the full spectrum of convergence thinking and practice. The six domains are as follows.

Table 1.

Convergence Competency Clusters, Definitions, and Related Concepts.

Table 1.

Convergence Competency Clusters, Definitions, and Related Concepts.

| Competency Cluster |

Definition |

Related Key Competencies |

Sources |

| Multidisciplinary Openness |

A mindset characterized by openness and curiosity toward diverse academic fields, new perspectives, and unfamiliar knowledge and phenomena |

Systems-thinking, Holistic thinking, Interdisciplinary work, Transdisciplinarity, Openness, Diversity of perspectives, Curiosity |

[7]; [30]; [31] |

| Integrative Willingness |

A proactive orientation to view issues and phenomena through the convergence of various perspectives, knowledge, and information |

Values-thinking Competency, Value diversity, Reflexivity, Participation, Trans-cultural understanding, Empathy, Inclusion, |

[7]; [31]; [32]; [33] |

| Convergent Learning |

The ability to analyze and synthesize knowledge across disciplines to derive new insights through reasoning and reflection |

Strategic-thinking Competency, Problem-solving, Critical thinking, Learning for change |

[7]; [33]; [34] |

| Collaborative Convergence |

The social ability to communicate and cooperate effectively with individuals from diverse academic backgrounds and information domains |

Interpersonal Competency, Communication, Collaboration, Conflict resolution, Solidarity, Networking, Building teams, Social engagement |

[7]; [30]; [35]; [36] |

| Futures Literacy |

The competency to identify signals of future change, make data-informed predictions, and define emerging tasks and challenges |

Futures-thinking Competency, Anticipatory thinking, Foresight, Scenario creation, Trans-generational thinking, Identifying signals |

[7]; [33]; [34] |

| Future Self-Efficacy |

The self-efficacy and social agency to proactively engage with uncertain futures and generate positive transformation |

Implementation Competency, Change agency, Action-taking, Social responsibility |

[7]; [30]; [33] |

4.2. Definition, Components, and Preliminary Items of Future Convergence Competencies: Findings from the Delphi Survey

Each sub-competency was defined in concrete terms to ensure its measurability in actual educational settings, systematically incorporating the core elements required in both contemporary and future societies. Notably, competencies such as convergent communication and collaboration and future self-efficacy are increasingly emphasized amid rapidly changing social conditions, demonstrating the relevance and timeliness of the proposed framework.

Based on the existing literature, the Delphi panel was invited to review and refine the definitions and components of future convergence competencies. The initial definition proposed in Round 1 was as follows: “The ability to create new convergent values required by future society through understanding and integrative thinking across various academic domains.”

While this definition was generally supported, experts recommended greater conceptual precision regarding the term “convergent values.” Additionally, they suggested replacing the phrase “required by future society” with a more concrete formulation such as “required by future society and industries.” These refinements aimed to reinforce the practical and future-oriented nature of the definition.

Incorporating these recommendations, the revised definition emphasized the actionable dimensions of convergence competencies and their relevance to socio-industrial transformation. The revised definition was subsequently subjected to content validation. The content validity analysis yielded a mean rating of 4.70 (on a 5-point scale) and a CVR of 1.00, based on Lawshe’s method, thereby confirming the conceptual soundness and content appropriateness of the refined definition.

Table 2.

Refinement of the Definition of Future Convergence Competencies through Delphi Survey.

Table 2.

Refinement of the Definition of Future Convergence Competencies through Delphi Survey.

| Version |

Definition |

M (SD) |

CVR |

| Initial Draft |

The ability to create new convergent values required by future society through understanding and integrative thinking across various academic domains |

4.00 (1.22) |

0.60 |

| Final Version (Revised after Delphi Survey) |

The ability to create novel and meaningful values required by future society and industries through understanding and integrative thinking across various academic domains |

4.70 (0.45) |

1.00 |

Based on a synthesis of previous research, the components of future convergence competencies were categorized into the following key domains: (1) Convergent Attitudes, including Multidisciplinary Openness and Integrative Willingness; (2) Convergent Knowledge, comprising Understanding of Integrative Knowledge and Convergent Learning; (3) Convergent Practice, encompassing Collaborative Communication and Problem-Solving; and (4) Futures Orientation, including Futures Literacy and Future Self-Efficacy. The validity of these domains and sub-competencies was reviewed in terms of both conceptual clarity and practical relevance.

While no major objections were raised regarding the overall competency clusters, a few expert panelists noted the difficulty of explicitly delineating closely related sub-competencies. They highlighted the need for behavioral indicators that could concretely represent each sub-competency and better facilitate the promotion of convergence-related actions in educational practice.

The statistical validity of the proposed components was assessed. All competency domains received high evaluations, with average scores exceeding 4.4 on a 5-point Likert scale. Standard deviations for most items were below 0.5 indicating a high degree of consistency in responses. Furthermore, the interquartile range (IQR) for the majority of items was 1.00, suggesting stable variance in expert ratings. Most notably, the CVR for all components was 1.000, confirming exceptionally high content validity across all proposed elements.

Table 3.

Content Validity Results of Future Convergence Competency Components from Delphi Rounds 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Content Validity Results of Future Convergence Competency Components from Delphi Rounds 2 and 3.

| Competency Domain |

Sub-Competency |

Definition |

Round 2

M(SD) |

CVR |

Round 3

M(SD) |

CVR |

| Convergent Attitudes |

Multidisciplinary Openness |

A mindset of openness and curiosity toward various academic fields, perspectives, and knowledge when observing phenomena |

4.1 (0.831) |

0.80 |

4.3 (0.640) |

1.00 |

| Integrative Mindset / Willingness |

The willingness to engage in convergent thinking across diverse and novel perspectives to understand and address problems and phenomena |

4.0 (1.000) |

0.80 |

4.4 (0.663) |

1.00 |

| Convergent Knowledge |

Understanding of Integrative Knowledge |

The capacity to comprehend various disciplines and perspectives through a convergence-oriented lens |

4.2 (0.872) |

0.80 |

4.4 (0.490) |

1.00 |

| Convergent Learning |

The ability to analyze and synthesize diverse disciplinary knowledge and perspectives to generate new insights through reasoning |

4.2 (0.979) |

0.80 |

4.5 (0.671) |

1.00 |

| Convergent Practice |

Collaborative Communication |

The capacity to communicate and collaborate effectively with individuals from various academic backgrounds based on shared information and knowledge |

4.2 (0.979) |

0.80 |

4.3 (0.900) |

0.80 |

| Convergent Problem-Solving |

The competency to examine diverse perspectives and alternatives to propose convergent solutions to complex problems |

3.7 (1.100) |

0.60 |

4.3 (0.640) |

1.00 |

| Futures Orientation |

Futures Literacy |

The ability to identify and define future problems and goals through structured foresight and exploration |

4.2 (1.077) |

0.80 |

4.3 (0.900) |

1.00 |

| Future Self-Efficacy |

The ability to accept ambiguity and uncertainty in the future and to make meaningful choices and actions that influence oneself, organizations, and society |

3.8 (0.980) |

0.80 |

4.3 (0.900) |

1.00 |

As a result of the content validity assessment for the definitions of each competency domain and sub-competency, all definitions were confirmed to be valid, with mean scores exceeding 4.0 and CVR values above the threshold of 0.62. In Rounds 2 and 3 of the Delphi survey, expert validation of individual diagnostic items was conducted for each sub-competency. Based on the experts’ consolidated feedback, several items were revised or refined to improve clarity and alignment with the intended constructs. Thereafter, the revised preliminary items were subjected to a final round of validation, during which mean ratings and CVR values were re-evaluated, confirming their appropriateness. Details of the specific modifications made to the items and their associated validation statistics are presented in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Delphi Validation Summary.

Table 4.

Delphi Validation Summary.

| Competency cluster |

Item No. |

Draft |

Final |

| M(SD) |

CVR |

Revision Status |

Revised Item |

M(SD) |

CVR |

| Multidisciplinary Openness |

1 |

3.8(1.249) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I believe that people may think differently depending on their environment or culture. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.6(1.497) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I acknowledge the perspectives of peers who hold views different from mine. |

4.8(0.400) |

1.000 |

| 3 |

4.3(0.900) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I actively incorporate diverse contexts and information when solving problems. |

4.7(0.458) |

1.000 |

| 4 |

3.3(0.900) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 5 |

3.5(1.118) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I believe it is important to learn about various subjects and academic disciplines. |

4.4(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 6 |

2.6(1.019) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.0(1.095) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 8 |

2.9(0.943) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 9 |

3.4(1.357) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 10 |

3.3(1.005) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I enjoy asking questions about various subjects and academic fields. |

4.2(0.872) |

1.000 |

| 11 |

3.6(1.200) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I am curious about new knowledge related to various subjects and academic fields. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| Integrative Mindset/Willingness |

1 |

3.7(1.418) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I try to explain complex situations by applying knowledge from various fields. |

4.7(0.458) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

4(1.1832) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I try to utilize knowledge from multiple disciplines when creating new outcomes. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 3 |

3.4(1.281) |

0.400 |

Revised |

I try to solve problems by integrating knowledge from various domains. |

4.3(0.781) |

1.000 |

| 4 |

4.0(0.894) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I try to apply interdisciplinary knowledge to solve problems. |

4.4(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 5 |

3.3(1.345) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 6 |

3.2(1.249) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.5(1.432) |

0.400 |

Revised |

I am open to thinking from the perspective of experts in other fields. |

4.0(0.775) |

0.800 |

| 8 |

3.1(1.300) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 9 |

3.1(1.300) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| Understanding of Integrative Knowledge |

1 |

3.7(0.781) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I tend to apply diverse knowledge and experiences when solving problems. |

4.3(0.640) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.8(1.327) |

0.600 |

Revised |

When needed, I actively seek to understand knowledge from unfamiliar fields. |

4.1(1.044) |

0.800 |

| 3 |

3.7(1.269) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I try to understand various disciplines to approach problems comprehensively. |

4.0(1.183) |

0.600 |

| 4 |

4.1(0.943) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I believe it is necessary to understand knowledge from diverse fields depending on the problem context. |

4.6(0.916) |

0.800 |

| 5 |

3.7(1.269) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I believe that real-world problems are interconnected across multiple domains of knowledge. |

4.4(1.019) |

0.800 |

| 6 |

3.1(1.300) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.5(1.360) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 8 |

3.7(1.005) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I can generate new ideas by combining interrelated knowledge. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 9 |

3.8(1.166) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 10 |

3.7(1.187) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I try to learn new knowledge from a variety of disciplines. |

3.9(1.044) |

0.800 |

| 11 |

3.1(1.044) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I enjoy working on collaborative projects with students from different majors, such as engineering, humanities, or arts. |

4.1(1.221) |

0.600 |

| 12 |

3.1(1.300) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| Integrated Learning for Convergence |

1 |

2.8(1.166) |

0.000 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 2 |

3.0(1.341) |

0.200 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 3 |

3.3(1.345) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 4 |

3.4(1.200) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I am able to identify links between different academic disciplines. |

4.2(0.748) |

1.000 |

| 5 |

3.6(1.281) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I can discover connections between seemingly unrelated things or phenomena and integrate them appropriately. |

4.4(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 6 |

3.8(1.327) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.2(1.400) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I make an effort to find connections between my major and other disciplines. |

4.3(0.900) |

0.800 |

| 8 |

4.0(1.183) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I can comprehend and internalize new knowledge and apply it to other domains. |

4.4(0.489) |

1.000 |

| 9 |

3.8(1.166) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I strive to integrate newly acquired knowledge and information with my existing understanding. |

4.4(0.916) |

0.800 |

| 10 |

3.6(1.200) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I often think about how to combine my disciplinary knowledge with other fields. |

4.0(1.000) |

0.800 |

| Convergent Communication and Collaboration |

1 |

4.2(0.872) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I respect diverse viewpoints and can work cooperatively with individuals who hold different perspectives. |

4.5(0.500) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.6(1.019) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 3 |

4.1(0.943) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I can co-construct and expand new knowledge and understanding through interactions with others. |

4.7(0.458) |

1.000 |

| 4 |

4.3(1.005) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I am able to accept information, knowledge, and viewpoints from fields outside of my own major. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 5 |

3.7(0.900) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I am open to accepting ideas that differ from my own. |

4.6(0.489) |

1.000 |

| 6 |

4.3(0.900) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I can communicate and collaborate with individuals from different academic disciplines or perspectives. |

4.7(0.458) |

1.000 |

| 7 |

3.4(1.200) |

0.800 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 8 |

3.3(1.100) |

0.800 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 9 |

3.5(1.360) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 10 |

3.8(1.166) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I enjoy learning through mutual communication between my field of study and other disciplines. |

4.5(0.500) |

1.000 |

| Convergent Problem Solving |

1 |

3.8(1.166) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I can gather relevant information about a problem and derive a valid solution. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.4(1.114) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 3 |

3.6(1.114) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 4 |

3.5(1.432) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 5 |

3.0(0.894) |

0.400 |

Retained |

I can apply diverse perspectives to solve problems and identify their success factors. |

4.0(0.894) |

0.800 |

| 6 |

3.2(0.979) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.5(1.025) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 8 |

3.5(1.025) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I seek solutions to problems from multiple perspectives. |

4.7(0.458) |

1.000 |

| 9 |

3.4(1.019) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 10 |

3.7(1.345) |

0.400 |

Revised |

I can prioritize and choose the most effective and appropriate method for solving a problem. |

4.2(0.979) |

0.800 |

| 11 |

4.0(0.894) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I can search for the information needed to solve a problem using multiple methods. |

4.5(0.500) |

1.000 |

| 12 |

3.6(1.114) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I can set criteria to decide among various problem-solving approaches. |

4.1(1.044) |

0.800 |

| Future Issue Recognition |

1 |

3.5(0.922) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I become interested when I hear about future technologies or societal changes. |

4.4(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.1(1.136) |

0.400 |

Retained |

I enjoy discussing future technologies and societal changes. |

4.4(0.800) |

1.000 |

| 3 |

3.2(1.327) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 4 |

4.2(0.979) |

0.800 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 5 |

3.6(1.114) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 6 |

3.3(1.269) |

0.400 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 7 |

3.6(1.114) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 8 |

3.6(1.114) |

0.600 |

Deleted |

– |

|

|

| 9 |

3.7(1.100) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I can identify and analyze errors or hidden intentions in future-related information. |

4.2(0.871) |

1.000 |

| 10 |

4.1(0.943) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I can compare and analyze various sources to understand different perspectives on the future. |

4.6(0.489) |

1.000 |

| 11 |

4.0(1.000) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I can recognize and predict patterns of change based on future-related information. |

4.4(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 12 |

3.9(1.044) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I can synthesize past and present data to derive implications for the future. |

4.6(0.489) |

1.000 |

| Future Efficacy |

1 |

3.9(0.943) |

0.800 |

Retained |

I believe that today’s choices and actions can change our future. |

4.6(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 2 |

3.6(1.281) |

0.600 |

Revised |

I believe that present decisions can influence future outcomes. |

4.5(0.671) |

1.000 |

| 3 |

4.1(0.943) |

0.800 |

Revised |

I believe it is important to take actions that bring positive change in the future. |

4.6(0.663) |

1.000 |

| 4 |

3.3(1.486) |

0.400 |

Revised |

Even in the face of an uncertain future, I can respond with a willingness to change. |

4.2(1.166) |

0.800 |

| 5 |

3.7(1.005) |

0.600 |

Retained |

Even when others are pessimistic about the future, I believe we can develop responses together. |

4.2(1.249) |

0.800 |

| 6 |

3.7(1.269) |

0.600 |

Retained |

I am confident that I can overcome various difficulties in preparing for the future. |

4.2(1.166) |

0.800 |

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Reliability Results

To determine the appropriate number of factors in advance, the Maximum Likelihood method was applied, and factors with eigenvalues of 1 or higher were selected. As correlations between factors were assumed, Direct Oblimin Rotation—an oblique rotation method—was employed.

As a result of the analysis of the Convergence Competency Diagnostic Tool for Future Talent, five factors were extracted. Based on the theoretical content of each factor, they were named as follows: Integrative Willingness, Future Issue Recognition, Future Efficacy, Convergent Learning, and Multidisciplinary Openness. The total explained variance of the five factors was 65.433%. The appropriateness of each preliminary item was examined, and items with communalities below 0.4 were removed, resulting in a final set of 20 items. As a few of the original preliminary items were removed, EFA was conducted again on the 20 items.

To verify whether the observed variables followed a multivariate normal distribution in the reanalysis, skewness and kurtosis were examined. Skewness ranged from –0.678 to 0.512, and kurtosis ranged from –1.123 to 1.044, indicating that the assumption of multivariate normality was met. The result of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .001, Chi-square = 2946.691, df = 190), and the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) measure was .925, exceeding the threshold of .5, confirming that the data matrix was suitable for factor analysis. To verify the reliability of each factor, Cronbach’s α values were calculated, and the reliability of the five factors ranged from .802 to .912, indicating acceptable levels.

Table 5.

Exploratory Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Convergence Competency Scale.

Table 5.

Exploratory Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Convergence Competency Scale.

| Factor Name |

Item Codes |

Normality Test |

Factor |

Reliability |

| Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

Factor 5 |

Communality |

| Convergent Commitment (Factor 1) |

CH07 |

-1.011 |

0.574 |

0.735 |

0.175 |

0.063 |

0.218 |

0.223 |

0.655 |

0.866 |

| CH06 |

-1.042 |

0.779 |

0.717 |

0.133 |

0.110 |

0.279 |

0.189 |

0.643 |

| CH08 |

-1.137 |

1.344 |

0.686 |

0.176 |

0.199 |

0.219 |

0.187 |

0.620 |

| CH05 |

-1.012 |

0.893 |

0.620 |

0.212 |

0.177 |

0.190 |

0.235 |

0.560 |

| Future Problem Awareness (Factor 2) |

CH18 |

-1.100 |

0.955 |

0.183 |

0.757 |

0.180 |

0.256 |

0.071 |

0.666 |

0.866 |

| CH16 |

-1.187 |

0.729 |

0.127 |

0.747 |

0.148 |

0.228 |

0.132 |

0.610 |

| CH19 |

-0.979 |

0.345 |

0.223 |

0.598 |

0.202 |

0.295 |

0.142 |

0.568 |

| CH17 |

-0.957 |

0.183 |

0.224 |

0.589 |

0.286 |

0.300 |

0.221 |

0.648 |

| Future Efficacy (Factor 3) |

CH21 |

-1.768 |

3.797 |

0.135 |

0.104 |

0.790 |

0.108 |

0.126 |

0.639 |

0.839 |

| CH22 |

-2.047 |

5.699 |

0.125 |

0.173 |

0.772 |

0.118 |

0.108 |

0.652 |

| CH20 |

-1.447 |

2.684 |

0.101 |

0.152 |

0.714 |

0.160 |

0.134 |

0.596 |

| CH24 |

-1.467 |

2.320 |

0.153 |

0.392 |

0.520 |

0.110 |

0.117 |

0.439 |

Convergent Learning

(Factor 4) |

CH11 |

-0.612 |

0.268 |

0.241 |

0.257 |

0.067 |

0.668 |

0.156 |

0.577 |

0.816 |

| CH12 |

-0.740 |

0.229 |

0.249 |

0.214 |

0.182 |

0.607 |

0.121 |

0.517 |

| CH13 |

-0.726 |

0.497 |

0.247 |

0.245 |

0.206 |

0.600 |

0.122 |

0.549 |

| CH10 |

-0.472 |

0.129 |

0.177 |

0.238 |

0.115 |

0.577 |

0.179 |

0.462 |

Multidisciplinary Inclusiveness

(Factor 5) |

CH04 |

-1.187 |

0.933 |

0.243 |

0.189 |

0.096 |

0.183 |

0.720 |

0.654 |

0.758 |

| CH03 |

-2.151 |

6.130 |

0.209 |

0.234 |

0.037 |

0.158 |

0.659 |

0.538 |

| CH02 |

-1.491 |

3.398 |

0.164 |

-0.020 |

0.241 |

0.090 |

0.604 |

0.470 |

| CH01 |

-2.136 |

6.011 |

0.359 |

0.104 |

0.228 |

0.136 |

0.571 |

0.495 |

| Eigenvalue |

6.034 |

2.653 |

2.201 |

1.645 |

1.411 |

|

|

| % Variance Explained |

30.169 |

13.265 |

11.007 |

8.225 |

7.055 |

|

|

| Cumulative % Variance |

30.169 |

43.434 |

54.441 |

62.666 |

69.721 |

|

|

4.4. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In this study, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the same dataset owing to practical constraints. While this approach provides preliminary evidence of construct validity, it may pose the risk of overfitting. Future studies should validate the factor structure using an independent sample to ensure generalizability.

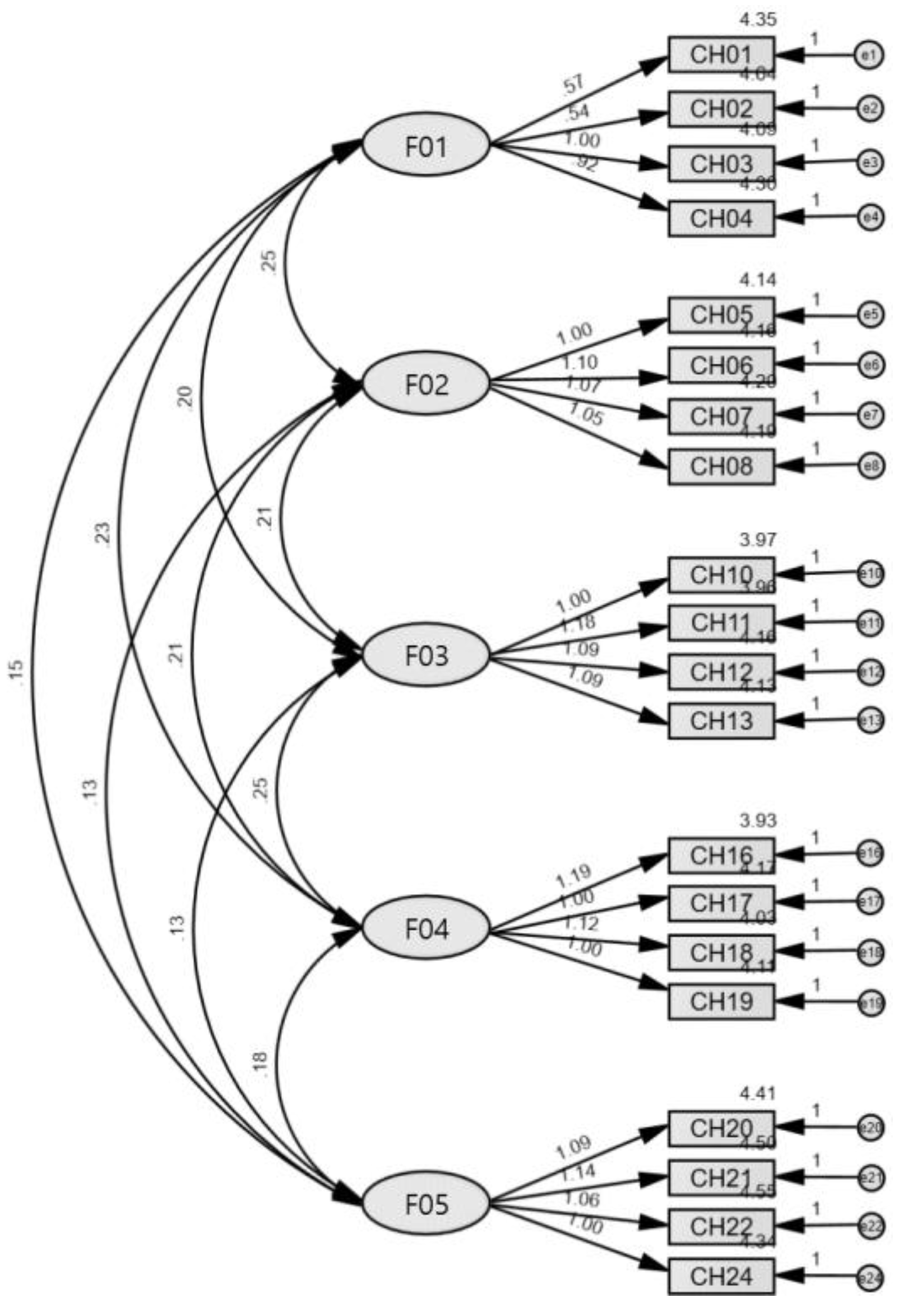

To evaluate the five-factor structure derived from the EFA, a CFA was performed. The model fit indices revealed a chi-square value of χ²(160) = 378.786 (p < .001), with a CMIN/DF of 2.367, which falls within the acceptable range (< 3.00), indicating a reasonable model fit.

Regarding absolute fit indices, the results were RMR = .053, RMSEA = .054, GFI = .902, and AGFI = .878. These values meet or approximate the commonly accepted thresholds (RMR < .08, RMSEA < .06, GFI ≥ .90, AGFI ≥ .85), indicating satisfactory model fit. Incremental fit indices also supported model adequacy, with NFI = .921, IFI = .953, TLI = .937, and CFI = .952, all exceeding the .90 benchmark.

Taken together, the results confirm that the proposed five-factor model aligns well with the empirical data (

Figure 2). This supports the structural validity of the convergence competency assessment tool and confirms its potential as a psychometrically sound instrument.

4.4. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To validate the structural model derived from the EFA, CFA was conducted. The model fit indices were as follows: χ² = 378.786, df = 160 (p < .001), CMIN/DF = 2.367. The absolute fit indices indicated acceptable model fit (RMR = .053, RMSEA = .054, GFI = .902, AGFI = .878). Incremental fit indices also supported a good model fit (NFI = .921, IFI = .953, TLI = .937, CFI = .952), suggesting that the hypothesized structure was empirically supported.

4.5. Finalized Items

Following the processes of preliminary item selection, EFA, and CFA, the final version of the diagnostic tool for convergence competencies in future-ready students was confirmed with 5 factors and 20 items. The tool followed a multivariate normal distribution and was verified to be suitable for factor analysis based on Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the KMO measure. Internal consistency reliability was also acceptable for all five factors.

To further evaluate the reliability of the finalized tool, Cronbach’s α was calculated using responses from 469 valid cases. The overall reliability coefficient was .919, indicating a high level of internal consistency. The α values remained stable (ranging from .912 to .919) even when individual items were removed, suggesting minimal impact of single items on the overall reliability. These results confirm that the tool possesses high reliability and can serve as a valid instrument for measuring convergence competencies.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study aimed to theoretically and empirically identify the components of convergence competencies required for a sustainable future society, targeting undergraduate students in HASS, and to develop and validate a self-assessment tool. Unlike existing research that often focuses on abstract descriptions or STEM-centric tools, this study contributes to the literature by proposing HASS-specific indicators of convergence competence.

First, the study integrated key elements emphasized in education for sustainable development (ESD)—systems thinking, collaboration, future responsiveness, etc.—into a structured competency model. The model encompasses attitudinal dimensions (e.g., interdisciplinary inclusiveness, convergence mindset, etc.), cognitive dimensions (e.g., understanding of convergent knowledge, integrative learning, etc.), and behavioral dimensions (e.g., collaborative communication, problem-solving, future efficacy, etc.). This comprehensive structure aligns closely with the notion of “interdisciplinary competence for transition and transformation” [37,38].

Second, through EFA and CFA, the tool’s reliability and validity were empirically verified, confirming its potential for practical use in HASS educational settings. The high structural coherence among factors and internal consistency of items suggest applicability across diverse learning environments.

Third, the tool not only facilitates individual-level diagnosis of convergence competence but also serves as an evaluation instrument to assess and improve curriculum effectiveness at the department, college, and consortium levels. It offers a foundation for competency-based quality assurance and feedback mechanisms in higher education.

5.1. Practical and Policy Implications

5.1.1. Use as a Feedback Tool for Convergence Curriculum

The tool can be applied to pre- and post-assessments in general education, co-curricular, and interdisciplinary programs, including MOOCs and PBL-based or cross-campus collaborative courses. It enables quantitative evaluation of program outcomes and provides evidence for program refinement.

5.1.2. Design of Personalized Learning Pathways Based on Diagnostic Results

By analyzing individual diagnostic results, tailored learning paths can be suggested, including recommended courses, co-curricular activities, and external experiences aligned with career goals. Integration with digital learning management systems (LMS) can support implementation.

5.1.3. Expansion Across Fields and Policy Integration

While developed for HASS, the tool can be extended to STEM and used for cross-disciplinary comparisons, regional or demographic gap analyses, and studies on the educational impact on underrepresented groups. It can serve as a foundation for national policies such as quality assurance in higher education.

5.1.4. Faculty Development and Pedagogical Innovation

In addition to learner assessment, the tool can be applied to evaluate the effectiveness of faculty development programs, such as “Teaching for Sustainability.” It enables feedback on convergence course design and supports instructional improvement.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Future studies should expand the application of the tool to diverse age groups, cultural backgrounds, and academic fields to assess its generalizability through multi-group analysis. Additionally, alternative assessment methods such as peer evaluations or portfolio-based assessments should be considered to supplement self-reported data. Structural equation modeling (SEM) could be employed to examine the relationships among convergence competency, academic achievement, and career outcomes.

In conclusion, this study fills a theoretical gap in the development of a convergence competency diagnostic tool tailored to the HASS context, while providing practical utility in both educational and policy domains. The tool may serve as a critical foundation for transforming educational systems toward cultivating convergence talent capable of driving sustainable societal transitions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. Jung; data collection, Y. Noh and I. Song; formal analysis, Y. Noh and I. Song; writing—original draft preparation, H. Jung; writing—review and editing, H. Jung, Y. Noh, and I. Song. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dankook University (Internal Research Fund). The authors would like to thank the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) for supporting the data collection for this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for the purposes of English editing, proofreading, and formatting of reference styles. The authors have reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics |

| HASS |

Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences |

| CVR |

Content Validity Ratio |

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

| SGDs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| WEF |

World Economic Forum |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| KMO |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| MOOC |

Massive Open Online Course |

| PBL |

Problem Based Learning |

| SEM |

Structural equation modeling |

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. In Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 785163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammer, G. Disciplining Interdisciplinarity: Integration and Implementation Sciences for Researching Complex Real-World Problems; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassler, M.; Dettmers, J. How to enhance interdisciplinary competence—interdisciplinary problem-based learning versus interdisciplinary project-based learning. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2017, 11, Article 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braßler, M. Interdisciplinary problem-based learning—a student-centered pedagogy to teach social sustainable development in higher education. In Teaching Education for Sustainable Development at University Level; Leal Filho, W., Pace, P., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key Competencies in Sustainability in Higher Education—Toward an Agreed-Upon Reference Framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.A.; Miller, K.; Perea-Vicente, J.L. Academic entrepreneurship in the humanities and social sciences: A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 1880–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J. A study on limitations and possibilities of convergence education in engineering. J. Eng. Educ. Res. 2019, 22, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, J. Integration of Education for Sustainable Development with Competency-Based Education. ABC Acad. Bank Credit AI Artif. Intell. BDI Beck Depress. Invent. CAI Comput.-Aided Instr. CAL Comput.-Aided Learn. 2024, 19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohd-Barkati/publication/385936886_Education_Technology_and_Sustainability/links/673ef9c888177c79e83c9cbb/Education-Technology-and-Sustainability.pdf#page=35.

- Kim, H.; Ryou, O. Case study of development of competency-based convergence subject in higher education: focused on the development guidelines and principles of ‘Practice on Manufacturing Systems’. J. Learn.-Cent. Curr. Instr. 2021, 21, 767–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Development of university convergence major standards to promote key competencies. J. Holist. Converg. Educ. 2020, 24, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B. Current diagnosis for convergence education and measures to improve convergence capacity. Korean J. Gen. Educ. 2016, 10, 13–35. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002178341 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Future of Jobs Report 2023; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Future of Jobs Report 2025; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Jones, P.; Selby, D.; Sterling, S. More than the sum of their parts? Interdisciplinarity and sustainability. In Sustainability Education; Jones, P., Selby, D., Sterling, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Usca, N.; Samaniego, M.; Yerbabuena, C.; Pérez, I. Arts and humanities education: A systematic review of emerging technologies and their contribution to social well-being. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novis-Deutsch, N.; Cohen, E.; Alexander, H.; Rahamian, L.; Gavish, U.; Glick, O.; Mann, A. Interdisciplinary learning in the humanities: Knowledge building and identity work. J. Learn. Sci. 2024, 33, 284–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsler, S.; Facer, K. Contesting anticipatory regimes in education: Exploring alternative educational orientations to the future. Futures 2017, 94, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.L. Competencies and pedagogies for sustainability education: A roadmap for sustainability studies program development in colleges and universities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, G. Gestaltungskompetenz als Kompetenzkonzept der Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung. In Kompetenzen der Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung: Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 23–43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gerhard-De-Haan/publication/226689376_Gestaltungskompetenz_als_Kompetenzkonzept_der_Bildung_fur_nachhaltige_Entwicklung/links/56c4562608ae7fd4625a1755/Gestaltungskompetenz-als-Kompetenzkonzept-der-Bildung-fuer-nachhaltige-Entwicklung.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Sposab, K.; Rieckmann, M. Development of sustainability competencies in secondary school education: a scoping literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A.; Boström, G.O. An Assessment of Key Sustainability Competencies: A Review of Scales and Propositions for Validation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 24, 53–69. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ijshe-05-2022-0166/full/html (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Vare, P.; Arro, G.; de Hamer, A.; Del Gobbo, G.; de Vries, G.; Farioli, F.; Kadji-Beltran, C.; Kangur, M.; Mayer, M.; Millican, R.; et al. Devising a competence-based training program for educators of sustainable development: Lessons learned. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, R.; Perez, P.; Vandenbussche, V. Competencies of sustainability professionals: An empirical study on key competencies for sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S.; Thomas, I. Education for sustainability: The role of capabilities in guiding university curricula. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 1, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearins, K.; Springett, D. Educating for sustainability: Developing critical skills. J. Manag. Educ. 2003, 27, 188–204. Available online: http://libms.dankook.ac.kr/welibhtml/proxy/proxy.js/scholarly-journals/educating-sustainability-imperative-action/docview/213774315/se-2?accountid=10536 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofton, F. Educating for sustainability: Opportunities in undergraduate engineering. J. Clean. Prod. 2000, 8, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, E.; Larson, K. Educating for sustainability: Competencies & practices for transformative action. J. Sustain. Educ. 2011. Available online: http://proquest.com/intermediateredirectforezproxy (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Lans, T.; Blok, V.; Wesselink, R. Learning apart and together: Towards an integrated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M.U. Enhancing students and learning achievement as 21st-century skills through transdisciplinary approaches. In Transdisciplinary Approaches to Learning Outcomes in Higher Education; Kumar, R., Ong, E., Anggoro, S., Toh, T., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 220–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, H.; Rai, S.S.; Zweekhorst, M.B. Transdisciplinary competencies for transformation. In Transdisciplinarity for Transformation: Responding to Societal Challenges through Multi-Actor, Reflexive Practices; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 469–495. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).