1. Introduction

Society’s dynamic and continuous development requires education to respond to social and cultural novelties through constant transformation and searching for corresponding solutions to the challenges of this era. The traditional understanding of classic education, which primarily took care of the transfer of knowledge to the next generation, has been replaced by a new one aimed at preparing university graduates for living within society, focusing on the necessity to activate students’ thinking potential, to develop competences for resolving tasks set by their changing social environment [

1].

A UNESCO report on the vision of the development of education by 2050 emphasises that the world has changed a lot due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the global climate crisis, and linkages should therefore be established between what students learn at schools and universities and what is currently happening in the world. In the near future, the main task of education will be to help people manage not only professional but also social challenges. Education should not centre around the rational mind but socially useful or transversal competences, providing social sustainability and contributing to the common good [

2].

Therefore, universities increasingly become a space for the implementation of solidarity and cooperation, where an individual’s initiative, proactive behaviour and responsibility for the future sustainability of society are encouraged [

3,

4]. Research into transversal competences is thus gaining increasing importance, as their development in interaction with professional competences is necessary for individuals to adapt to change successfully and live meaningful and productive lives. [

5].

The European Pillar of Social Rights emphasises that encouraging the development of competences is one of the goals of the European Education Area that would allow the full-scale use of educational and cultural potential as a driving force promoting social justice and active citizenship, encouraging the study of the European identity in its diversity [

6]. It also emphasises the set of competences relevant for a young professional to encourage university graduates’ professional autonomy and help to maintain the current standard of living in society, preserve employment and contribute to social cohesion, taking into account the changing society and labour market requirements.

It is important to develop professional autonomy as a quality attesting to one’s ability to be independent, self-determined, proactive, self-managed in making decisions, flexible, and resilient in performing professional activity [

7] during one’s studies at university. Therefore, transversal competences are viewed as the “cornerstone” of the development of each individual, as they are essential in the application of any knowledge and skills [

8].

After analysing recent studies regarding students’ transversal competences, the crucial competences for university graduates both in the study process and for young professionals and citizens were identified and selected for the present study: civic, digital, entrepreneurial, global, innovation, and research [

9].

Digital competence describes a student’s behaviour in using information and communication technologies (ICTs) and digital media for efficient communication, information management, cooperation, and creating and disseminating knowledge within one’s professional and/or study activity [

10]. The labour market increasingly expects competences like the ability to resolve non-standard problem situations by using existing digitalisation possibilities and to develop new innovative solutions. Digital competence is related to the application of information and communication technology solutions for supporting tasks in the workplace, and like other transversal competences, it can be transferred among fields [

11,

12,

13].

Innovation competence includes a student’s knowledge, skills and attitudes needed for creating efficient improvements or innovations useful for people or organisations (a new product or solution, invention, method, device, or idea) and their long-term implementation. Innovation has become the third “mission” of universities alongside education and research [

14], as it acts as the promoter of economic prosperity, scientific discoveries, technological inventions and cultural dynamism, promoting global economic, technological and social achievements. Students are among the leading social innovation actors in higher education; therefore, it is the task of universities not only to train students for future employment possibilities but also to promote their opportunities to create innovations [

15].

Entrepreneurial ability means the creation, identification or modification of ideas and opportunities by mobilising and efficiently using necessary resources to attain goals in action. This transversal competence is applicable to all areas of life, from personal growth and active involvement in society processes to participation in the labour market as an employee or a self-employed person and starting social or commercial entrepreneurial activity. Entrepreneurial ability is recognised as a key to an individual’s development and fulfilment, active citizenship, social inclusion and employability in a knowledge-based society [

16].

Global competence describes the skill of assessing local, global and intercultural issues, understanding and assessing different perspectives and global views, engaging in open and effective interaction with people of various cultural backgrounds, and acting for the benefit of collective prosperity by contributing to sustainable development. Global competence is characterised by the ability to make decisions within the global environment by assessing diverse perspectives and global views and interacting with representatives of various cultures [

17].

Civic competence describes a person’s participation in civic and social life and promotion of healthy social and political prosperity and sustainability at the community, national and global levels. Civic competence is a set of values, knowledge and skills for effective, active, meaningful and responsible civic and social engagement, contributing to social and political prosperity and sustainability, democratic mutual communication and communities’ economic growth [

18].

The development of students’ transversal competences has a specific meaning in post-totalitarian societies, where there is a deficit of ideas and skills vital for democracy, for example, argumentation skills, civic engagement, openness to diversity, etc. [

1,

19]. Thus, the development of transversal competences at universities should also be considered as the development of tools for strengthening the sustainability of society.

When studying the development of students’ transversal competences, it should be taken into account that this is a multi-level and multi-factor process involving the continuous interaction of various factors.

First, this process can be viewed from the angle of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological system theory [

20,

21], conceptualising an individual’s development as a continuous and dynamic interaction with their environment via its ecological systems of various levels—the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem. Although Bronfenbrenner’s model was initially constructed to understand an individual’s development and functioning within their closest and farthest social-cultural environment, it has been adapted to multiple fields of research and can also be used for obtaining a better understanding of the development of students’ transversal competences, affecting factors and the interaction of factors on various levels.

For example, in studies regarding the development of the digital competence, it has been found that there is an interaction of various factors in its development at the individual, microsystem, exosystem and macrosystem levels—personal factors (self-confidence in using ICTs, attitudes towards ICTs, prior training on ICTs, motivation), learning design (online, blended learning), lecturers’ digital competence and external aspects (family support, COVID-19 pandemic) [

13]. In studies regarding entrepreneurial ability, the interaction and synergy of various factors are underlined (e.g., innate entrepreneurial aptitude, sociological conditions, and educational programmes), and the lack of any component limits the individual potential of an entrepreneur [

22]. There is also a range of studies about the mutual interaction of various factors in the development of both the global competence in the school [

23] and university [

24] environment and the civic competence [

25].

Second, the transversal competences possessed by an individual may be viewed as factors that not only interact with other factors but also affect and network with each other. Hanesová and Theodulides [

26] propose looking at students’ transversal competences as a system that changes and develops jointly, with several competences being mutually interlinked and all being linked with the ecosystem of higher education. This idea is also used in the present study through the following objectives: to find out how students’ six transversal competences (civic, digital, entrepreneurial, global, innovation, and research and their respective sub-competences) mutually interact and to propose possible approaches to how this dynamic of interaction can be applied to facilitate transversal competences’ change and development. In this way, it will be possible to discover which transversal competence elements are more linked to others. This, in turn, will allow us to identify how, by developing one component, we can expect other competences to grow to promote transversal competences’ sustainable development.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Competences and Sub-Competences across the Sample

Indices were calculated for all competences and sub-competences by averaging the items (behavioural indicators) representing the respective competence/sub-competence. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for each competence and sub-competence are displayed in

Table 1. The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was used to check whether the data were normally distributed. Because the distribution for all indices (except for the overall index of digital competence) did not fit a normal distribution, non-parametric methods of analysis were used to examine the differences and relationships among the competences and sub-competences.

First, the overall indices for all six competences were compared across the sample using the Friedman test; Conover’s post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were used for pairwise comparisons. All the indices (except for global and innovation competences, which did not differ significantly from each other) were significantly different (Chi-square = 2161.23, p < .001). The global and innovation competences showed the highest ratings, and the civic competence, by a large margin, had the lowest rating.

Next, the sub-competences were compared using the same method. The digital competence’s sub-competences all differed significantly from each other (Chi-square = 1860.41, p < .001), except for communication and cooperation and problem-solving, which did not differ significantly from each other. For the global competence, all sub-competences differed significantly from each other (Chi-square = 244.00, p < .001), except for information management and values and attitudes in an intercultural environment, which did not differ significantly from each other. For the innovation competence, all sub-competences differed significantly from each other (Chi-square = 274.77, p < .001), except for creativity and teamwork, which did not differ significantly from each other. For the research competence, all sub-competences differed significantly from each other (Chi-square = 899.58, p < .001), except for attitude and ethics and conducting research, which did not differ significantly from each other. For the civic competence, there was a significant overall difference between the three sub-competences (Chi-square = 331.95, p < .001), but the ratings for community involvement and civic capacity did not differ significantly from each other, whereas the third sub-competence—knowledge and application of the principles of a democratic society—was evaluated significantly higher. Finally, all three sub-competences of the entrepreneurial competence differed significantly from each other (Chi-square = 309.77, p < .001).

3.2. Network Analysis of Sub-Competences

A network analysis of the sub-competence indicators was used to estimate and visualise the relationships among all sub-competences. Network analysis allows the relationships among multiple interrelated variables to be visualised, and it is an especially appropriate method for presenting data where the directionality of causal links among the variables is difficult to establish, as is true in the case of transversal competences and their sub-competences. This data analytic approach treats the correlations among constructs as a network where nodes represent variables in a data set and edges represent pairwise conditional associations between variables in the data while conditioning on the remaining variables [

27].

The network analysis was based on regularised partial correlations with nonparanormal transformation of variables, using graphical LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) with a tuning parameter chosen using the Extended Bayesian Information Criterium (EBIC). The analysis was done in the JASP software (0.14.1) Network module, which runs on the R package ‘bootnet’ for calculations and the R package ‘qgraph’ for network visualisation. Bootstrapping with 1000 resamples was used to evaluate the network’s robustness and estimate the stability of the network’s centrality measures.

The network plot is depicted in

Figure 1. A visual examination of the network structure reveals that sub-competences of the same competence cluster together and tend to have stronger links among themselves than with the sub-competences of other competences. For some competences (e.g., entrepreneurial competence), the links among the sub-competences are of similar strength; for others (e.g., global and digital competence), some links between the sub-competences are weaker than others, and the bootstrap confidence intervals for those links include zero.

Overall, one can observe predominantly positive associations among most competences in the network, showing that all transversal competences positively correlate with each other. There are also some negative edges (dotted lines in

Figure 1), but it should be noted that for all except one of these negative edges, the bootstrap confidence intervals for their edge weights included zero. The only robust negative relationship is between the research sub-competence

collaboration and communication and the global sub-competence

awareness of diversity in local and global communities.

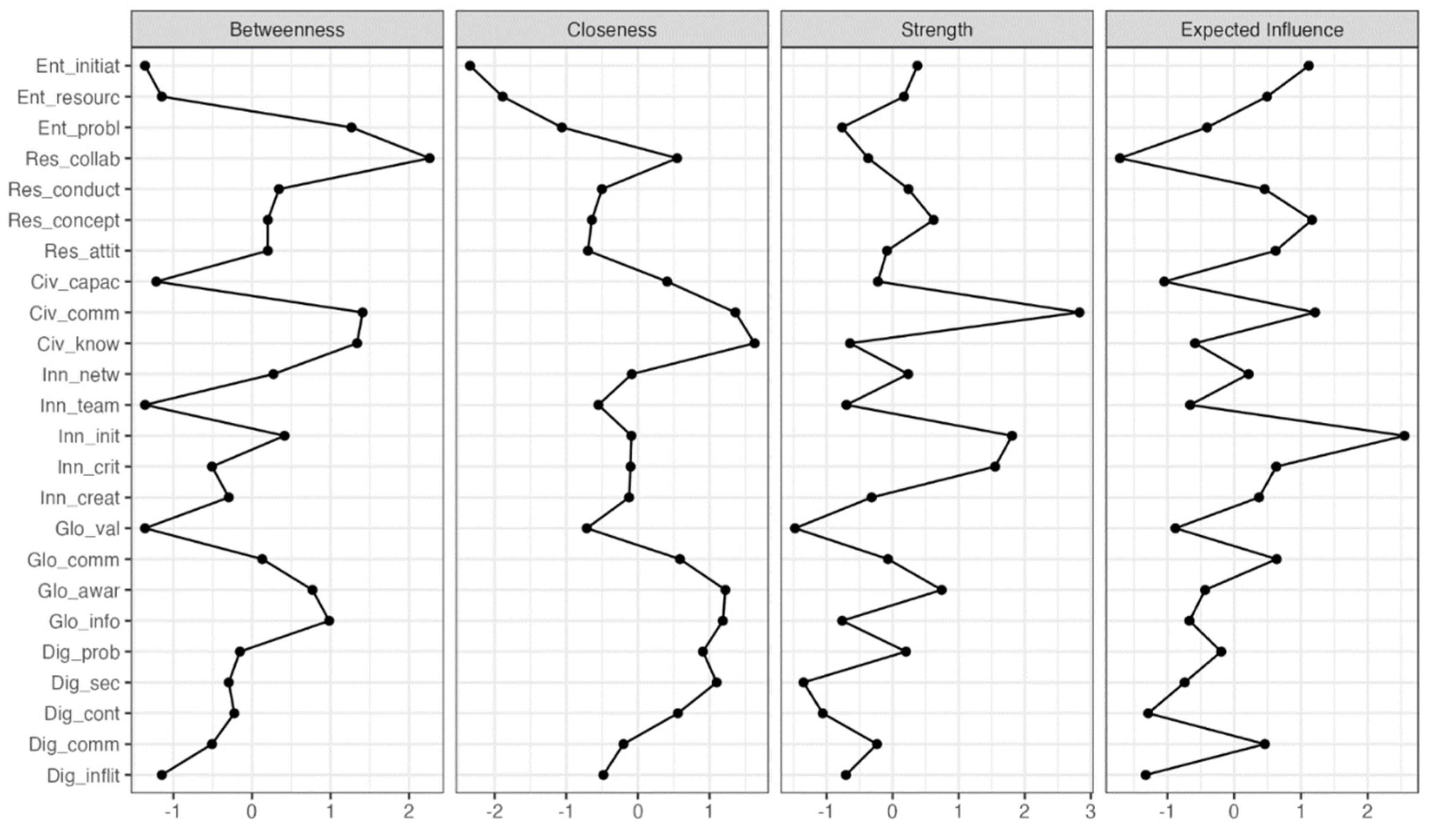

The centrality measures for the calculated network are depicted in

Figure 2. Two indicators are of special interest for this analysis. First, one can see that the

community involvement sub-competence of the civic competence and the

initiative and

critical thinking sub-competences of the innovation competence have the highest strength. Strength refers to how strongly a given node is directly connected to other nodes in the attitude network, counting both positive and negative associations. These three sub-competences have the strongest links to the other sub-competences in the network on average. The

community involvement sub-competence

, besides strong links to the other two sub-competences of the civic competence, also has robust positive relationships with the

intercultural communication and cooperation sub-competence of the global competence, the

collaboration and communication sub-competence of the research competence, and the

digital content creation sub-competence of the digital competence. The

initiative sub-competence, besides having strong relationships with the other sub-competences of the innovation competence, also has robust positive relationships with the

initiative and action orientation and

identification, mobilisation, and effective use of internal and external resources sub-competences of the entrepreneurial competence and the

values and attitudes in an intercultural environment sub-competence of the global competence. The

critical thinking sub-competence also has robust positive relationships with the other sub-competences of the innovation competence, except for the

networking sub-competence (the bootstrap confidence interval for this edge included zero). Critical thinking also had robust positive relationships with three out of four sub-competences of the global competence (

information management, awareness of diversity in local and global communities, and

values and attitudes in an intercultural environment) and the

information literacy and data literacy sub-competence of the digital competence.

The other centrality indicator of interest is expected influence. This measure is similar to strength but considers the direction of associations, so if a node has both positive and negative links to other nodes, it leads to lower expected influence, whereas many positive links result in higher expected influence. The highest expected influence can be observed for the initiative sub-competence of the innovation competence, which, as mentioned before, is robustly related to sub-competences of the entrepreneurial and global competences.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results reveal a general tendency that sub-competences associated with active and systematic collaboration and networking were evaluated lower than others. This is true about four of the six competences studied, the exceptions being the entrepreneurial competence (which does not have a designated sub-competence for cooperation and/or networking) and the digital competence, where the communication and cooperation sub-competence includes indicators related to the technical use of digital communication tools. The respondents indicated that they felt unsure about their abilities and skills to actively, systematically and continuously engage with others in various activities and contexts. In combination with the low self-evaluation of the civic competence, these results show a pattern of a generally underdeveloped set of skills and knowledge necessary for social and civic engagement.

Similar trends were also revealed by the international assessment of pupils’ civic education in 2022, the results of which confirm that a majority of 13–14-year-old teenagers in Latvia are passive from the civic point of view and that some of them are inclined to get involved in illegal protest activities [

28]. The above results can be explained by the implications of post-Soviet values and a relatively short experience of democracy in Latvian society, manifested as a lack of trust in democracy as a state administration form and its values [

1]. Likewise, the Russian mass media propaganda in Latvia as a border state of the European Union is another important explanation of the youth’s civic passivity [

29].

Still, the youth’s civic passivity is not only characteristic of countries of the post-Soviet space—a comparison with preceding study cycles and among IEA ICCS 2022 member states indicates that pupils are generally not active and do not possess much initiative [

30]. For example, an analysis of the most recent reforms in the field of democratic citizenship in Nordic countries’ national curricula led to the conclusion that the civic engagement level tends to decrease irrespective of the old democracy traditions in Scandinavia and relatively good results achieved by pupils in ICCS assessments [

31]. Therefore, it is necessary to seriously focus on the role of not only schools but also universities in encouraging the youth’s active involvement to secure the future sustainability of democracy. However, although the youth can be taught about democracy and its values at school and university, it is imperative for educational establishments to cooperate with the broader community and to strengthen civic engagement and values of all the youth, irrespective of their social and economic background [

31].

One needs to ask how this overall pattern of low civic engagement may affect the general development of transversal competences. The network analysis reported above allowed us to establish which sub-competences were most strongly related to others and thus may be hypothesised as having the strongest potential direct and indirect influence on the development of the whole set of transversal competences. Two observations are relevant here. First, the sub-competence with the lowest rating of all—community involvement from the civic competence—also has the strongest average connection with other sub-competences in the network (with the highest strength and the second-highest expected influence). This suggests that the low development of community involvement may have a hampering effect on the development of a number of other sub-competences, especially those from the global, research and digital competences, with which it has the strongest connections (a reverse causality is also possible, though—one can speculate that respondents with lower overall transversal competence development may find it more difficult to get involved in all kinds of communities and social networks). The second observation is that although the other communication- and collaboration-related sub-competences with lower ratings are not as strongly connected to other nodes of the competence network on average, each of them still has strong and robust connections to other sub-competences of the transversal competence to which it belongs, thus exerting a more subtle but still non-trivial potential influence on transversal competences’ overall development. Taken together, these observations suggest that the development of a broad range of cooperation- and collaboration-related and network-building skills may not only improve the corresponding sub-competences but may also have a systematic positive effect on the development of a wider set of transversal competences and the professional autonomy of students in the long term.

Another observation may be made if we consider the sub-competences with the highest strength and expected influence. One characteristic shared by the three sub-competences with the highest strength—the community involvement sub-competence of the civic competence and the critical thinking and initiative sub-competences of the innovation competence, the latter also displaying the highest expected influence—is that they all have robust connections with one or more sub-competences of the global competence. This pattern suggests that the potential influence of these most central sub-competences may be exerted through the global competence. This means that developing the community involvement, initiative, and, especially, critical thinking sub-competences may be expected to lead to the strongest beneficial effects for the global competence and thereby for other competences positively related to it. Again, however, the reverse causal link is also possible by higher global competence positively contributing to civic and innovation competence through the corresponding high-centrality sub-competences. In any case, these results point to the global competence as another potential pathway for the sustainable wide-range and long-term development of the whole set of transversal competences measured in this study.

Service learning, study abroad and internships are the civic or community-based learning experiences that universities should pay particular attention to if we want to develop a global and sustainable society focused on diversity. The most robust findings related to the effect of community or civic experience are related to personal or social responsibility results. Research on awareness of and mindsets towards diversity is more often related to study experience abroad rather than any other experience related to society [

32].

The results show an overall pattern of weak-to-moderate positive relationships among the sub-competences measured in this study (with very few mostly weak and non-robust negative relationships observed). Broadly speaking, this pattern suggests that the development of any transversal competence should bring potential benefits for some, if not all, other transversal competences. However, the results also point to the most promising directions for potential educational interventions aimed at the development of transversal competences. Among the several sub-competences with the highest strength indicator, the initiative sub-competence (from the innovation competence) stands out as having the highest expected influence. This means that by developing initiative, one can expect the highest overall positive effect on other transversal competences, especially entrepreneurial competence and global competence, without any identifiable potential negative side effects on other competences’ development. This expected influence would not be large in terms of the effect size but rather non-trivial and likely noticeable in the long term. One can also speculate that there is a broader psychological factor beyond the initiative sub-competence related to the general disposition to be proactive, open-minded and able to spot and exploit opportunities in broad areas of life, which, in turn, is positively related to multiple behavioural indicators corresponding to many, if not all, transversal competences within and beyond those covered in this study.

In order to improve students’ initiative in the study process at universities, it is necessary to expand the organisation and offering of various measures for creating social innovations—business incubators, hackathons, think tanks, project competitions, community-based and civic engagement in studies, etc.—to enable students to be aware of their resources, strengths and weaknesses, to train their design thinking and problem-solving during their studies. The possibility of solving actual societal issues by reducing inequality will not only encourage the creation of social innovation but also allow students to become aware of their civic rights and obligations for the sustainable development of a democratic society.

In conclusion, the main finding of this study is that all the transversal competences measured are interconnected. Although the results allowed us to identify some sub-competences that are more central and thus have more potential influence than others, it is important to pay attention to the development of all transversal competences, keeping in mind that any improvement in any sub-competence bears the potential to benefit a number of related skills, thus contributing to the overall development of the whole set of a person’s transversal competences. IEA ICCS 2022 data analysis presents a direct link between students’ civic competence level and their presented attitudes—notable, students with a higher level of knowledge are more open to democratic values, i.e., civic initiative and engagement [

28]. Also, a study of university students’ initiative and active engagement and cooperation with the community has led to the conclusion that active and collaborative learning, as well as undergraduate research, has a broadly positive effect on several learning outcomes, for example, critical thinking, necessity for inquiry and intercultural effectiveness. [

32] It is crucial to strengthen civic engagement as early as in the school environment and to continue it at university to minimise challenges and risks over the long term and to encourage critical thinking, initiative and active involvement in society. Higher education institutions know precious little about students’ capacity to demonstrate their civic abilities in applied contexts, inside and outside the classroom. This is the next frontier for researchers to truly understand the ways in which community-based and civic practices contribute to students’ attainment of essential skills.

There are some limitations to the present research. One is the use of self-ratings for the evaluation of transversal competences. The accuracy of a self-assessment survey is lower than objective tests of skills and abilities or behavioural observations because the respondents’ answers can be affected by both a limited ability to remember specific examples of their actions, distorted memories of their past actions, and a general tendency to overestimate themselves, their skills and their abilities. Responses can also be affected by social desirability and motivation for positive self-presentation. Another limitation is related to the study’s sampling procedure. Although the surveyed sample was as diverse as possible and maximum effort was put into making the sub-sample from each participant university as random as possible, it should be noted that no common sampling frame was used for the whole population of Latvian students and the study sample cannot be considered fully representative of this population. As a result, some study fields and programmes may be overrepresented or underrepresented in the sample, and participants’ self-selection may also have affected the results. A third limitation concerns the contents of the survey instrument. There are situations where the descriptions of the behavioural indicators used in the survey are possibly too general (for example, the specifics of research may differ significantly in different fields) or too simple (for example, descriptions of the behavioural indicators of digital competence when carrying out competence assessment in the field of ICT). Although a unified competency assessment tool has many advantages (for example, it is easier to compare results between domains and to maintain, update and improve the instrument), the formulations may not work equally well with respondents from all study fields and study programmes, thereby affecting the results’ reliability.

Future research should explore the possible higher-order factors behind the various competences and sub-competences, as well as the relationships between transversal competences and other individual difference variables that may theoretically contribute to transversal skills and knowledge, such as general intelligence, personality traits, personal values, stable motives, etc. Such research would contribute to the theoretical understanding of the mechanisms behind the emergence and development of transversal competences and would also have practical applications in the creation of tools for the development of transversal competences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z.R., G.D., A.M.; methodology, G.D., A.M.; validation, Z.R., G.D., A.M.; formal analysis, G.D., A.M.; investigation, Z.R., G.D., A.M.; resources, Z.R.; data curation, G.D., A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.R., G.D., A.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.R., G.D., A.M.; visualisation, G.D.; supervision, Z.R.; project administration, Z.R; funding acquisition, Z.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.