Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Need for a Complex-Time Framework

2. Foundations of the Duality of Time Theory and Its Physical Implications

2.1. The Duality-of-Time Postulate (DoT)

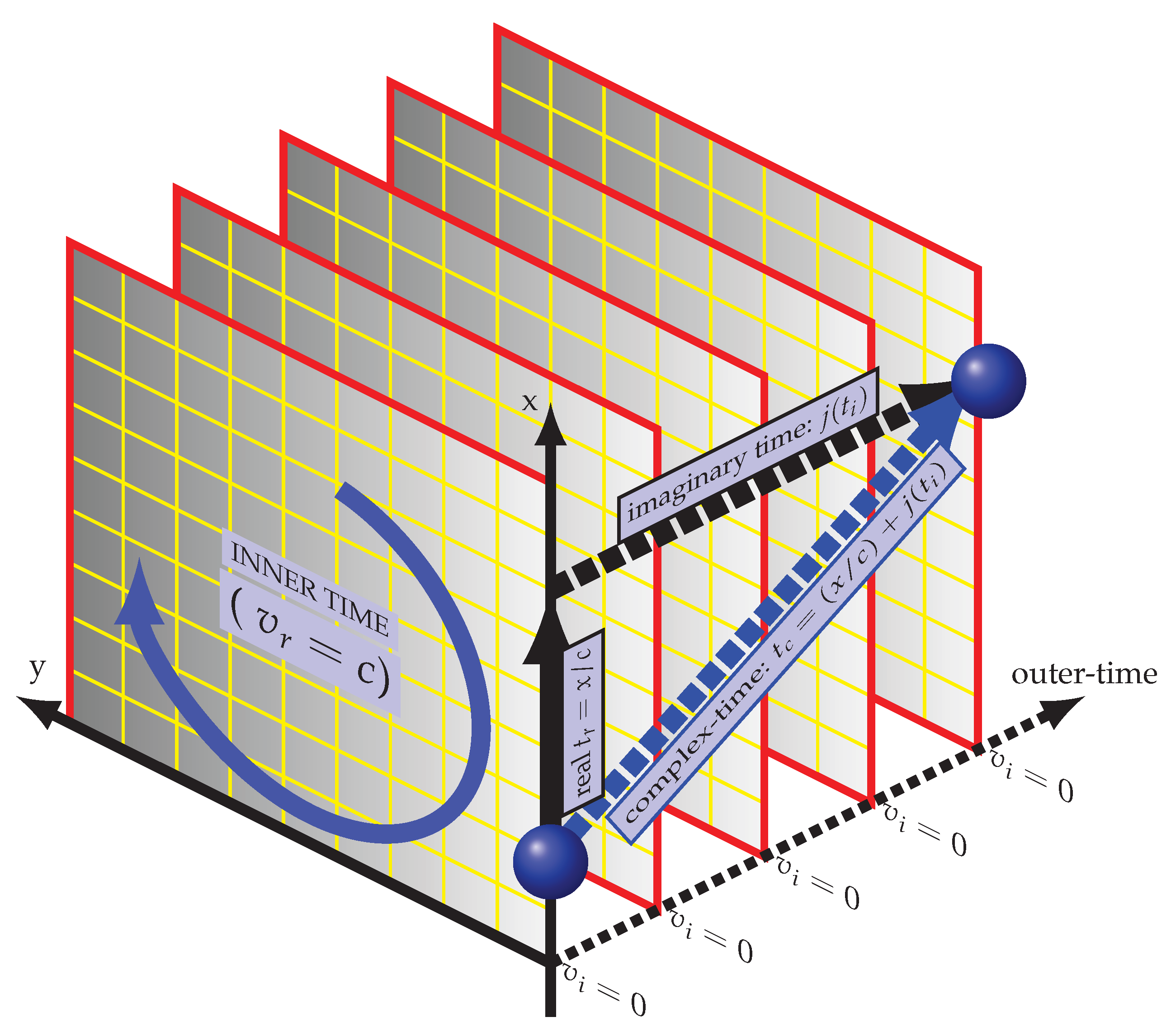

At every instance of the outer (imaginary) level of time, the spatial dimensions are continuously re-created through a precise chronological sequence of inner (real) time layers, forming nested temporal hierarchies embedded within each lower dimension.

2.2. The Complex-Time Structure

2.3. Physics from Metaphysics: the Single Monad Model (SSM)

2.4. Physical and Cosmological Implications of Inner-Time Dynamics

3. Comparative Analysis with Existing Quantum Gravity Approaches

- Time Structure: Splits time into real (generative) and imaginary (evolutionary) components, unlike conventional or relational treatments.

- Vacuum Energy: Naturally resolves the cosmological constant problem via real-time averaging, avoiding the discrepancy without fine-tuning.

- Lorentz Invariance: Lorentz symmetry arises inherently from DTT’s complex-time geometry rather than being imposed.

- Mass–Energy Origin: The mass-energy relation follows intrinsically from inner-time dynamics, without external fields or symmetry breaking.

- Singularity Avoidance: Continuous re-creation processes prevent singularities like the Big Bang and black holes, without requiring quantum bounces or string fuzziness.

- Background Independence: Eliminates any pre-existing spacetime assumptions, achieving a deeper level of background independence than other models.

3.1. Comparison with String Theory

3.2. Comparison with Loop Quantum Gravity

3.3. Comparison with Causal Set Theory (CST) and Causal Dynamical Triangulations (CDT)

3.4. Comparison with Entanglement-Based Emergence Models

3.5. Summary and Conceptual Distinctions of DTT

4. Hyperbolic Complex-Time Geometry: Mathematical Construction

4.1. The Ontological Process Underlying the Imaginary Nature of Time

4.2. The Advantages of the Hyperbolic Complex-Time Frame

4.3. Discreteness and the Two Primordial States

4.4. Supersymmetry and the Two Arrows of Time

- Normal time: , yielding (matter in space-time).

- Orthogonal time: , yielding (anti-matter).

- Balanced time: , yielding (super-energy/vacuum).

4.5. Reviving the Aether Concept and Reinterpretation Vacuum Energy

4.6. Yang-Mills Conjecture and the Origin of Mass and Charges

5. Deriving the Principles of Quantum Relativity from the DoT Postulate

- Galilean Invariance (extended to Lorentz Invariance).

- Constancy of the Speed of Light.

- Equivalence of Inertial and Gravitational Masses.

5.1. The Constancy and Invariance of the Speed of Light

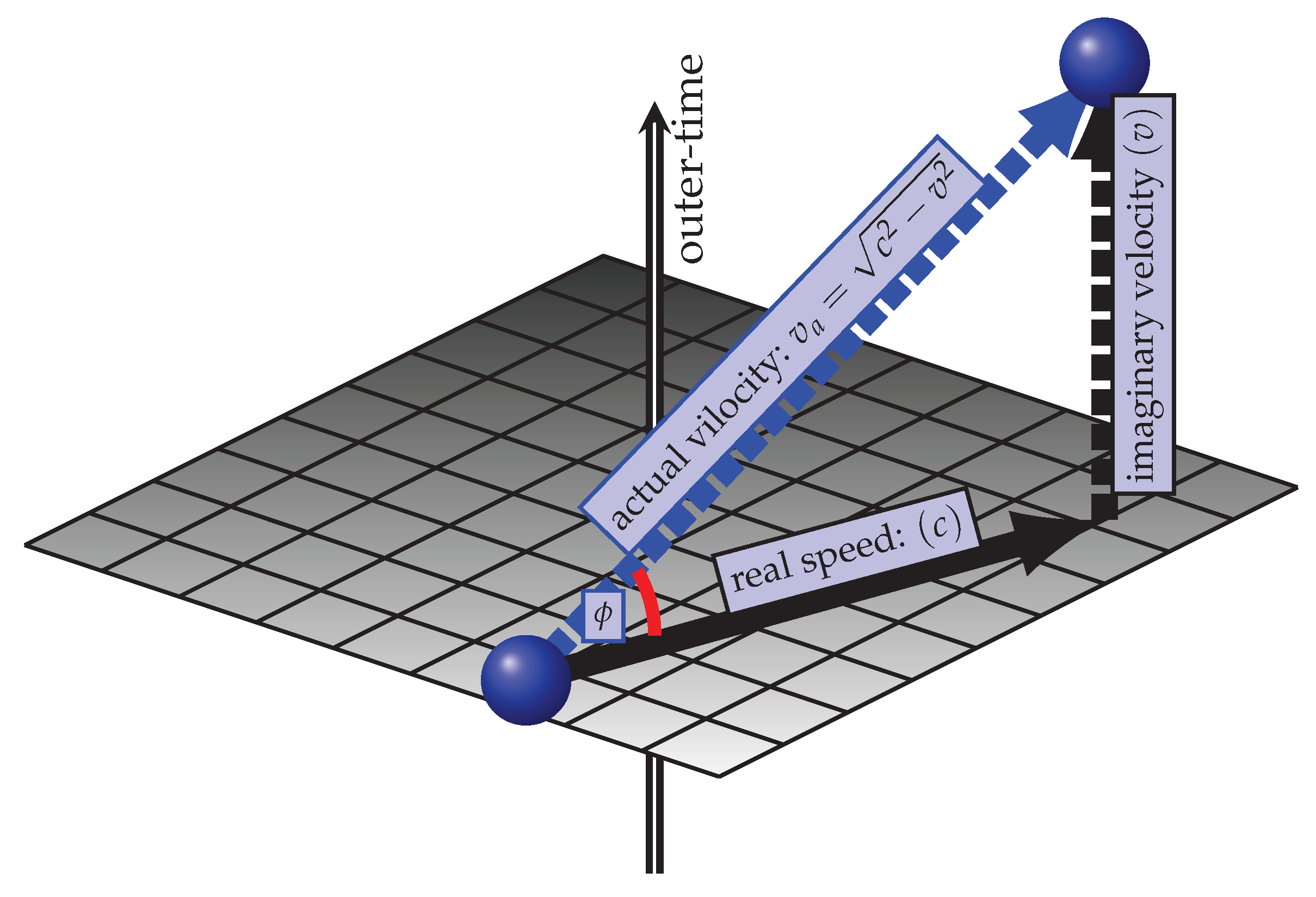

5.2. Deriving the Fundamental Invariance from Temporal Symmetry

5.3. The Pseudo-Riemannian Limit of DTT Discrete Symmetry

6. Mathematical Formulation of Complex–Time Geometry

6.1. Deriving Lorentz Transformations

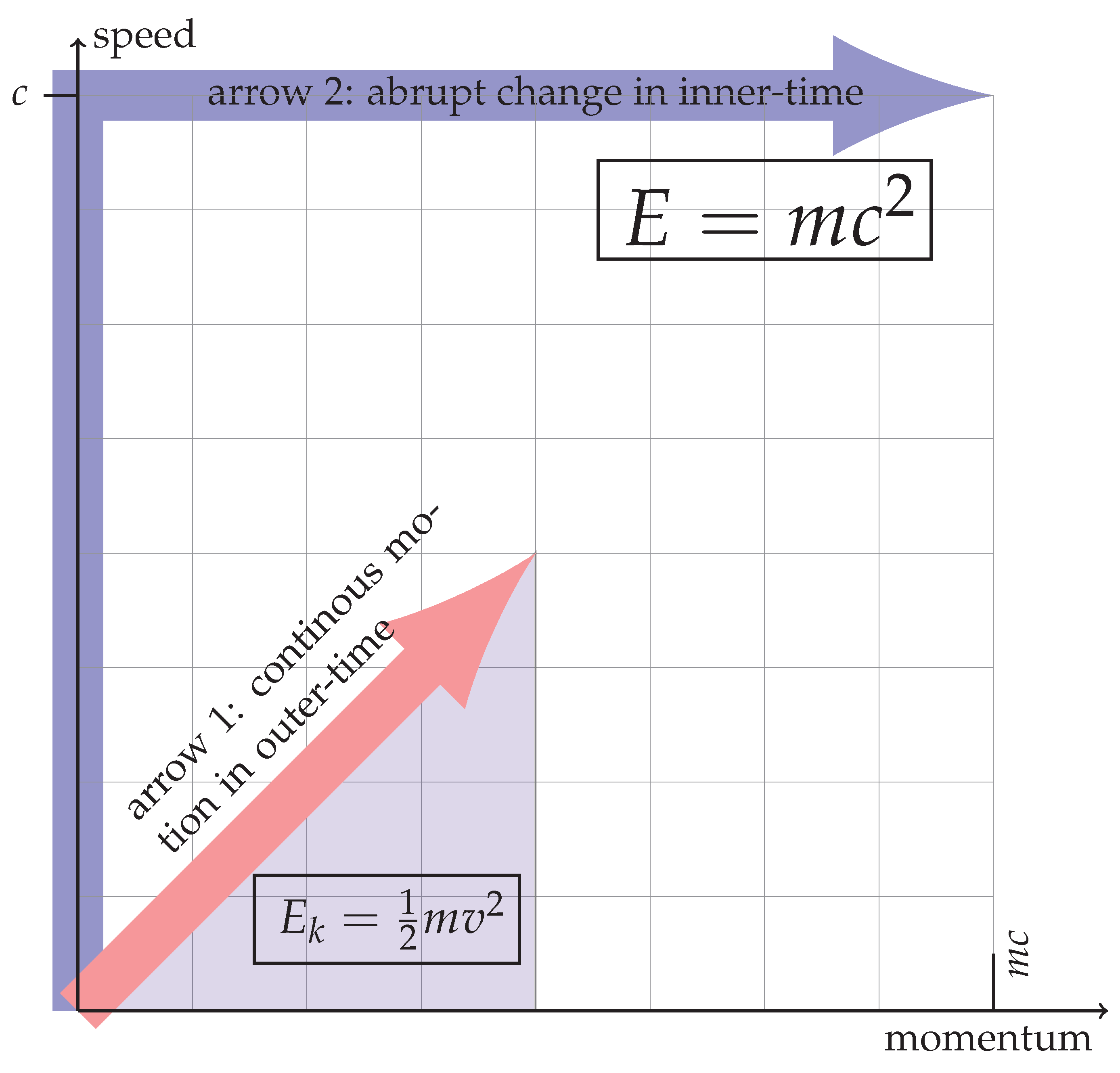

6.2. The Mass–Energy Equivalence Relation

6.2.1. The Classical Kinetic Energy (in Normal Time)

6.2.2. Method I (Abrupt Change of Speed in the Inner Time)

6.2.3. Method II (Generating Mass in the Inner Time)

6.2.4. Note I (Relativistic Mass)

6.2.5. Note II (Mass-Energy Duality)

6.2.6. Note III (Effective Mass)

6.2.7. Method III (Total Relativistic Energy)

6.2.8. Method IV (Complex Momentum and Energy-Momentum Relation)

6.3. The Equivalence Principle of General Relativity

6.4. Deriving the Einstein Field Equations from the DoT Postulate

- : Scalar field representing the local rate of real-time flow at spacetime point .

- : Emergent metric induced by sequential re-creation of spatial frames.

- : Cumulative sequential re-creation metric.

- : Effective Ricci tensor reflecting deviations in sequential re-creation.

- : Stress-energy modifying local sequential re-creation rates.

- : Intrinsic vacuum energy linked to underlying sequential dynamics.

| Aspect | General Relativity | Duality of Time Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Space-time | Pre-existing manifold | Emergent dynamic structure |

| Curvature | Geometric deformation | Delay in sequential re-creation |

| Gravity | Geometrized mass-energy | Sequential deformation dynamics |

| Field Equations | Covariant postulate | Emergent from internal dynamics |

| Cosmological Constant | Added ad hoc | Intrinsic vacuum tension |

7. Emergence of Einstein Field Equations from Inner-Time Dynamics

7.1. Statistical Structure of Emergent Geometry

7.2. Stress-Energy Tensor from Re-Creation Fluctuations

7.3. Emergent Curvature from Re-Creation Inhomogeneities

7.4. Emergent Einstein Field Equations

7.5. Complex Energy and the Fundamental Atomic Interactions

8. Empirical Predictions and Observational Signatures

8.1. Potential Observational Signatures of Complex-Time Geometry

- Gravitational Wave Dispersion: The discrete re-creation dynamics predict slight frequency-dependent dispersion of gravitational waves at cosmological scales. Deviations from Lorentz-invariant propagation could be detectable by LISA and next-generation observatories. Microscopic-scale experiments are increasingly sensitive to gravitational interactions at extremely short distances, as demonstrated by recent quantum-scale gravity measurements [84], suggesting that deviations from standard predictions could soon become observable.

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Anomalies: Residual imprints of early universe inner-time synchronization could manifest as low-multipole anomalies or hemispherical asymmetries in the CMB.

- Vacuum Decoherence Rates: The structured vacuum implies subtle deviations from perfect vacuum stability, possibly detectable as minute variations in Casimir forces or precision atom interferometry experiments.

- Dark Energy Evolution: A time-averaged structured vacuum suggests a slowly varying dark energy component, which could be observed through late-time cosmological surveys measuring the equation-of-state parameter .

- Fine-Structure Constant Variability: Spatial or temporal drift in fundamental constants, such as , could arise from differential evolution of inner vs outer time rates over cosmic history.

8.2. Quantitative Estimate: Gravitational Wave Dispersion

8.3. The Physical Vacuum as Dynamic Aether

- Is intrinsically Lorentz-invariant, as all physical motion occurs in the orthogonal outer-time.

- Does not affect the speed of light, which is governed by the inner/outer temporal ratio.

- Supports massless excitations, with mass emerging through temporal entanglement of geometrical nodes.

8.4. Vacuum Energy and the Cosmological Constant Problem

8.5. Dark Energy as a Residual Temporal Ground State

- Cosmic expansion reflects the ongoing formation of space rather than a repulsive force.

- Acceleration of expansion is linked to dynamic changes in local fractal dimensionality.

8.6. Mass Generation Without the Higgs Mechanism

- Isolated geometrical points are massless.

- Coupling between points via delayed re-creation induces inertia and rest mass.

- The minimal number of coupled nodes defines a discrete mass spectrum, independent of spontaneous symmetry breaking.

8.7. Matter–Antimatter Asymmetry and Supersymmetry Breaking

- Inner (real) time generating spatial dimensions.

- Outer (imaginary) time projecting observable motion and dynamics.

8.8. Phenomenological Predictions and Experimental Signatures

- Fractal and Scale-Dependent Spacetime: Local dimensionality depends on the inner-to-outer time ratio, possibly causing scale-dependent deviations from Lorentz invariance. Potential observational tests include gamma-ray dispersion or anomalies in ultra-high-energy cosmic ray propagation.

- Temporal Origin of the Arrow of Time: The asymmetry between inner and outer time layers geometrically underpins thermodynamic irreversibility, potentially correlating with anisotropies observed in the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

- Quantum Nonlocality as Temporal Synchronization: Entanglement correlations arise from synchronized re-creation across spatially separated points. Gravitational gradients might induce observable variations in entanglement decoherence times, offering new experimental probes into sub-quantum structures.

- Variations in the Speed of Light: The speed of light, being the ratio of inner to outer time scales, could exhibit slight variations near singularities or at Planck-scale energies. These effects might be detected through photon arrival delays from gamma-ray bursts or modified dispersion relations.

- Gravitational Wave Echoes and Discrete Redshifts: Inner-time layer reflections may cause gravitational wave echoes, and discrete redshift quantization could emerge from layer-by-layer re-creation.

- High-Energy Cosmic Ray Cutoff: A maximal re-creation frequency may impose a natural high-energy cutoff in cosmic ray spectra, distinct from standard GZK limits.

- Vacuum Birefringence: A spin-dependent structure of the dynamic vacuum may produce vacuum birefringence, potentially detectable in experiments such as PVLAS.

- Anomalous Bell Inequality Violations: Complex-time synchronization could lead to violations of standard quantum bounds (e.g., Tsirelson’s bound) in specially configured multipartite entanglement experiments.

8.9. Proposed Simulations and Experimental Tests

Discrete Time Quantum Field Theory Simulation

Re-creative Clock Interferometry

Neutrino Oscillation Deviations

8.10. Future Detection Channels

- Space-based Observatories: LISA, Euclid, and Roman Telescope may detect gravitational wave echoes, deviations in cosmic expansion, or discrete redshift anomalies.

- Quantum Optics Experiments: Bell-type inequality tests and delayed-choice quantum eraser setups could probe synchronization effects beyond standard quantum limits.

- Astrophysical Observations: Time delays in high-energy photon arrival from distant sources (e.g., GRBs) could reflect inner-time layering structures.

- Vacuum Structure Probes: Casimir force measurements and vacuum birefringence studies could reveal scale-dependent deviations attributable to granular vacuum properties.

9. Conclusion and Outlook

- The constancy and invariance of the speed of light, reinterpreted as a dimensionless ratio of inner to outer time intervals.

- Lorentz transformations, emerging directly from the discrete structure of complex-time geometry.

- The mass–energy equivalence relation, derived from inner-time dynamics without reliance on field-based mass generation mechanisms such as the Higgs field.

- The equivalence principle of inertial and gravitational mass, arising naturally from the internal dynamics of re-creation.

- Mass generation through temporal dynamics rather than scalar fields.

- Quantum nonlocality as a manifestation of synchronized re-creation cycles.

- Matter–antimatter asymmetry and supersymmetry breaking as consequences of the dual-time projection mechanism.

- The arrow of time as an emergent feature of sequential inner-time flow.

- A granular, self-organizing vacuum structure as the physical origin of both matter and dark energy phenomena.

- Gravitational wave dispersion effects.

- Anomalies in the cosmic microwave background.

- Measurable variations in vacuum energy density and particle mass generation.

- Developing a complete mathematical formalism for field dynamics within the complex-time geometry.

- Deriving concrete, testable predictions to distinguish the DoT framework from conventional models.

- Extending the framework to early-universe cosmology, black hole thermodynamics, and the foundations of quantum gravity.

- Investigating connections with quantum information theoretic approaches to space-time emergence.

References

- Hobson, M.; Efstathiou, G.; Lasenby, A., General Relativity: An Introduction for Physicists; Cambridge University Press, 2006; p. 187.

- Witten, E. Light rays, singularities, and all that. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiebach, B. A First Course in String Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: A status report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Sorkin, R.D. Causal Sets: Discrete Gravity. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2020, 29, 2042017. [Google Scholar]

- Oriti, D. The group field theory approach to quantum gravity. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2009, 27, 145017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A. The Spin-Foam Approach to Quantum Gravity. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 143001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabados, L.B. Minkowski Space from Quantum Mechanics. Foundations of Physics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The concept of time in Ibn Arabi’s cosmology and its implication for modern physics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK, 2005. published by Routledge in 2007 as (Ibn Arabi - Time and Cosmology).

- Haj Yousef, M.A. Ibn Arabi – Time and Cosmology; Routledge: London, New York, 2007.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The Single Monad Model of the Cosmos: Ibn Arabi’s Concept of Time and Creation; CreateSpace: Charleston, 2014.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. DUALITY OF TIME: Complex-Time Geometry and Perpetual Creation of Space; The Single Monad Model of The Cosmos, Book 2, CreateSpace: Charleston, 2017.

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P. Loop Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 084001. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, M.A.H. Deriving the Fine-Structure Constant from Dimensional Projection Coherence. SSRN Preprint, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.A.H. Spin from Temporal Topology: A Duality of Time Theory Interpretation. SSRN Preprint, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.A.H. A Rigorous Proof of the Yang–Mills Existence and Mass Gap via Duality of Time Theory. ResearchSquare Preprint, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.A.H. Deriving Newton’s Law and the Cosmological Constant from Inner-Time Projection Density. SSRN Preprint, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. The White Pearl: Names and Descriptions of the Single Monad.

- Haj Yousef, M.A. ULTIMATE SYMMETRY: Fractal Complex-Time, the Incorporeal World and Quantum Gravity.

- Hawking, S.W. Euclidean Quantum Gravity. In Recent Developments in Gravitation: Cargèse 1978; Lévy, M., Deser, S., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1979; pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Yousef, M.A. Zeno’s Paradoxes and the Reality of Motion According to Ibn al-Arabi’s Single Monad Model of the Cosmos. In Islamic and Christian Philosophies of Time, Vernon Series in Philosophy; Mitralexis, S., Ed.; Vernon Press: Wilmington, USA, 2018; chapter 7, pp. 147–178.

- Bojowald, M. Effective descriptions of quantum cosmology. Reports on Progress in Physics 2021, 84, 026902. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M., Quantum: Einstein, Bohr and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality.

- Green, M.B.; Schwarz, J.H.; Witten, E. Superstring theory; Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Zwiebach, B. A first course in string theory; Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Polchinski, J. String theory. Vol. 2: Superstring theory and beyond; Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Ashtekar, A. The quantum nature of the big bang: improved dynamics. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojowald, M. Quantum cosmology: A review. Reports on Progress in Physics 2021, 78, 023901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Loll, R. The emergence of spacetime from causal dynamical triangulations. Scientific American 2008, 299, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, L.; Surya, S. Causal Set Cosmology and Quantum Gravity. Entropy 2023, 25, 410. [Google Scholar]

- Dowker, F. Causal sets and the deep structure of spacetime. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2015, 373, 20140241. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, R.D. Does locality fail at intermediate length-scales? International Journal of Modern Physics D 2020, 29, 2042003. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, R.D. Causal sets: Discrete gravity (Notes for the Valdivia summer school). Classical and Quantum Gravity 2006, 23, R1–R13. [Google Scholar]

- Carlip, S.; Surya, S. Path integral suppression of badly behaved causal sets. arXiv preprint 2022, [arXiv:gr-qc/2209.00327].

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic Derivation of Entanglement Entropy from the Anti-de Sitter Space/Conformal Field Theory Correspondence. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 181602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raamsdonk, M.V. Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement. General Relativity and Gravitation 2010, 42, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Carroll, S.M.; Singh, S. Space from Hilbert Space: Recovering Geometry from Bulk Entanglement. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2017, 34, 074002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swingle, B. Entanglement Renormalization and Holography. Physical Review D 2012, 86, 065007, [0905.1317]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Takeda, D.; Tanaka, K.; Yonezawa, S. Spacetime-emergent ring toward tabletop quantum gravity experiments. arXiv preprint 2022, [arXiv:hep-th/2211.13863].

- Hawking, S., A Brief History of Time; Updated and expanded tenth anniversary edition, Bantam Books, 1998; p. 157.

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum Theory of Gravity. III. Applications of the Covariant Theory. Phys. Rev. 1967, 162, 1239–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panine, M.; Kempf, A. Towards spectral geometric methods for Euclidean quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 084033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borunda, M.; Janssen, B.; Bonga, B. Towards a split-complex extension of special relativity. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 045018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poincaré, M.H. Sur la dynamique de l’électron. Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo (1884-1940) 1906, 21, 129–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A., The Principle of Relativity; Original Papers by A. Einstein and H. Minkowski. Translated Into English by M.N. Saha and S.N. Bose; With a.

- Fjelstad, P. Extending special relativity via the perplex numbers. American Journal of Physics 1986, 54, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizeau, N.; Sels, D. Quantum Mereology and Subsystems from the Spectrum. Foundations of Physics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MICHELSON, A.; MORLEY, E. On the relative motion of the earth and the luminiferous ether. SPIE milestone series 1991, 28, 450–458. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker, R., Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension; Dover Books on Mathematics.

- DIRAC, P.A.M. Is there an AEther? Nature 1951, 168, 906–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, I.; Wang, L.; Steinhardt, P.J. Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratra, B.; Peebles, P.J.E. Cosmological consequences of a rolling homogeneous scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 1988, 37, 3406–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, R.R.; Dave, R.; Steinhardt, P.J. Cosmological Imprint of an Energy Component with General Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasznahorkay, A.J.; et al. Observation of Anomalous Internal Pair Creation in Be8 : A Possible Indication of a Light, Neutral Boson. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 042501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 73 - ON THE THEORY OF SUPERCONDUCTIVITY. In Collected Papers of L.D. Landau; HAAR, D.T., Ed.; Pergamon, 1965; pp. 546 – 568. [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Oakes, R.J.; Renner, B. Behavior of Current Divergences under SU3×SU3. Phys. Rev. 1968, 175, 2195–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, H.; Shapiro, P.R.; Weinberg, S. Likely Values of the Cosmological Constant. The Astrophysical Journal, 492, 29.

- SAHNI, V.; STAROBINSKY, A. THE CASE FOR A POSITIVE COSMOLOGICAL l-TERM. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2000, 09, 373–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, A. Lectures on the cosmological constant problem. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 093001. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. Implications of dynamical symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 13, 974–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. Dynamics of spontaneous symmetry breaking in the Weinberg-Salam theory. Phys. Rev. D 1979, 20, 2619–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeenkov, A.V.; Zloshchastiev, K.G. Quantum Bose liquids with logarithmic nonlinearity: self-sustainability and emergence of spatial extent. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics, 44, 195303.

- Dzhunushaliev, V.; Zloshchastiev, K.G. Singularity-free model of electric charge in physical vacuum: Non-zero spatial extent and mass generation. Central Eur. J. Phys. 2013, 11, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zloshchastiev, K.G. Spontaneous symmetry breaking and mass generation as built-in phenomena in logarithmic nonlinear quantum theory. Acta Phys. Polon. 2011, B42, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A. The Millennium Prize Problems: Yang–Mills existence and mass gap. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2000, 17, 4997–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinska, A. Structural Quantum Gravity, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E. How Einstein confirmed E 0=mc 2. American Journal of Physics 2011, 79, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudka, A.; et al. Renormalisation of Postquantum-Classical Gravity. Foundations of Physics 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy-content. Ann Phys 1905, 18, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. Das Prinzip der Relativität und die Grundgleichungen der Mechanik. Verh. Deutsch. Phys. Ges. 1906, 8, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, H.E. Derivation of the mass-energy relation. JOSA 1952, 42, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Über die Gültigkeitsgrenze des Satzes vom thermodynamischen Gleichgewicht und über die Möglichkeit einer neuen Bestimmung der Elementarquanta. Annalen der Physik 1907, 327, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Did Einstein prove E=mc2? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2009, 40, 167–173. [CrossRef]

- Capria, M., Physics Before and After Einstein; IOS Press, 2005; p. 82.

- Rohrlich, F. An elementary derivation of E=mc 2. American Journal of Physics 1990, 58, 348–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, J.; Chen, E.K. The Decoherent Arrow of Time and the Entanglement Past Hypothesis. Foundations of Physics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhateeb, E.A. Reconstruction of f(R) Gravity from Cosmological Unified Dark Fluid Model. Foundations of Physics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlamminger, S.; Choi, K.Y.; Wagner, T.A.; Gundlach, J.H.; Adelberger, E.G. Test of the Equivalence Principle Using a Rotating Torsion Balance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reasenberg, R.D.; Patla, B.R.; Phillips, J.D.; Thapa, R. Design and characteristics of a WEP test in a sounding-rocket payload. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 29, 184013.

- Nottale, L.; Schneider, J. Fractals and nonstandard analysis. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1984, 25, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnor, W.B. Negative mass in general relativity. General Relativity and Gravitation 1989, 21, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.P.; D’Agostini, G. Cosmological bimetric model with interacting positive and negative masses and two different speeds of light, in agreement with the observed acceleration of the Universe. Modern Physics Letters A 2014, 29, 1450182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; et al.. Quantum physics makes small leap with microscopic gravity measurement, 2024. The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2024/feb/23/quantum-physics-microscopic-gravity-discovery.

- Hur, S.; Minic, D.; Takeuchi, T.; Jejjala, V.; Kavic, M. First observational evidence supporting string theory, 2025. LiveScience article, available at: https://www.livescience.com/physics-mathematics/quantum-physics/scientists-claim-to-find-first-observational-evidence-supporting-string-theory-which-could-finally-reveal-the-nature-of-dark-energy.

- D’Angelo, E.; Ferrero, R.; Fröb, M.B. De Sitter quantum gravity within the covariant Lorentzian approach to asymptotic safety. arXiv preprint 2025, [arXiv:gr-qc/2502.05135].

- Lee, S.S. Massless graviton in a model of quantum gravity with emergent spacetime. arXiv preprint 2022, [arXiv:hep-th/2212.14011].

| Feature | SMM and DTT | LQG / CST / CDT | String Theory / AdS/CFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin of Spacetime | Emergent from complex-time dynamics (no pre-assumed structure) | Discrete elements on fixed or statistical background | Smooth manifold or boundary assumed; emergent features at limits |

| Continuity vs Discreteness | Both arise dynamically from dual temporal flows | Discreteness fundamental; continuity emergent statistically | Continuity fundamental; discreteness secondary |

| Background Independence | Full: no presupposed geometry | Partial: discrete structure built over assumed continuum | Partial: background needed for dualities |

| Causality | Emergent from sequential real-time generation | Postulated causal relations | Emergent in specific holographic models |

| Role of Quantum Entanglement | Secondary to inner temporal re-creation | Not primary | Primary (geometry from entanglement) |

| Mass Generation | Dynamic re-creation through structured vacuum; no Higgs required | Largely unexplained; external fields or boundary conditions | Via symmetry breaking (e.g., Higgs mechanism) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).