Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How have technical approaches to OpenBIM-based BIM–FM interoperability evolved, and what limitations remain?

- What managerial processes and human factors affect data quality and information handover?

- What strategic drivers and barriers influence organizational investment in OpenBIM for FM?

- How do tensions across these dimensions shape future research directions?

2. Methodology

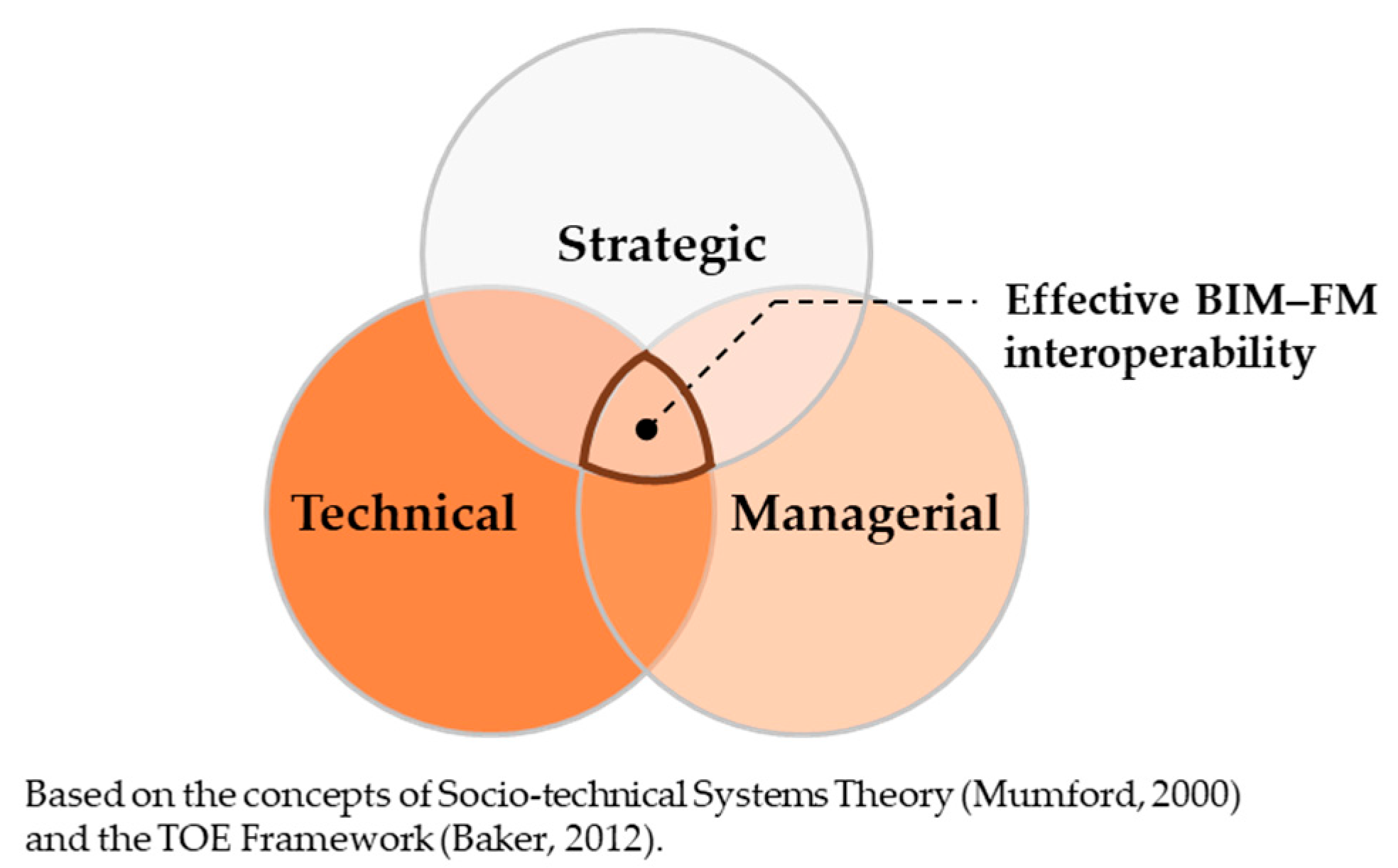

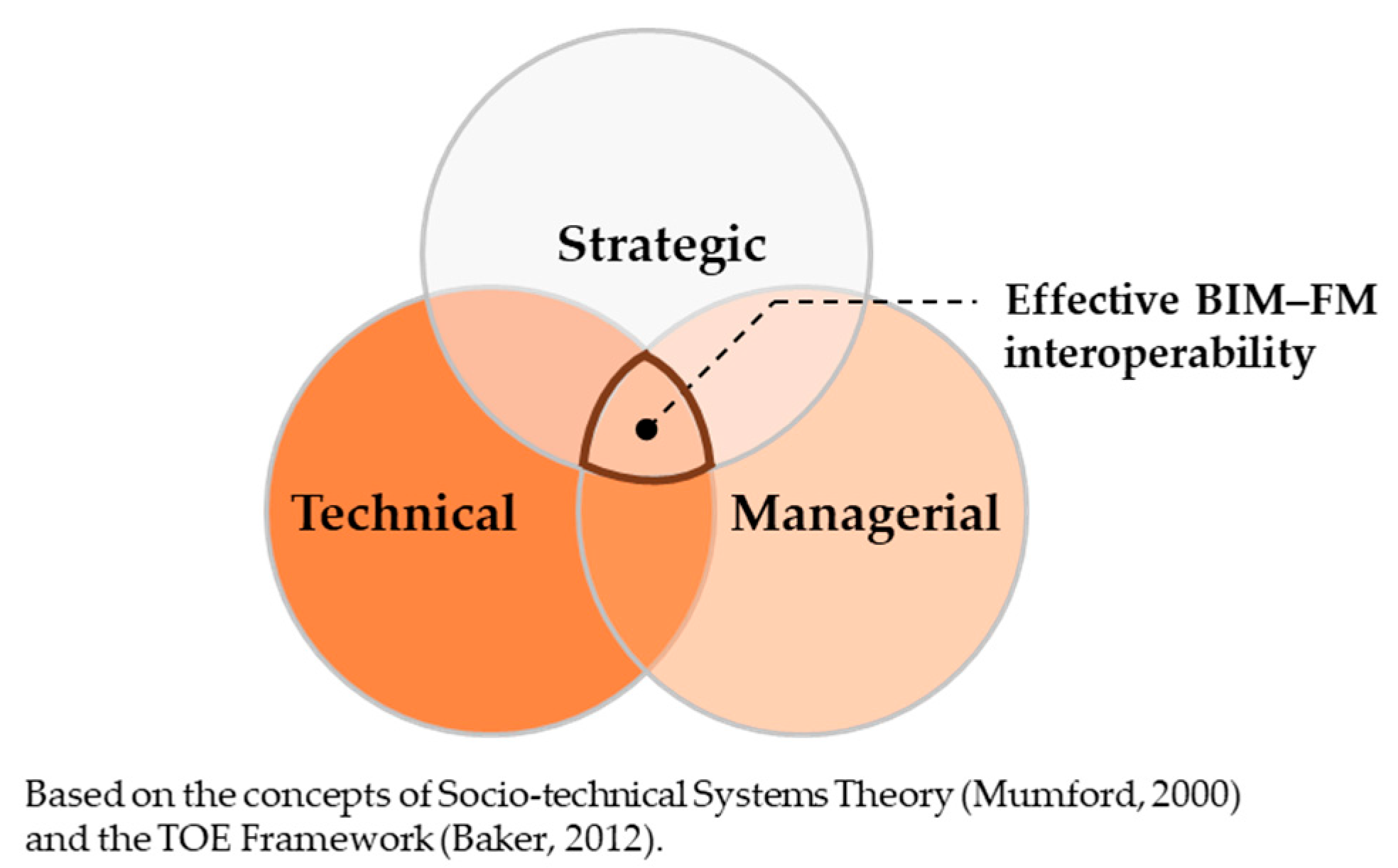

- Socio-technical Systems Theory, which stresses the interdependence between technologies and the social systems in which they operate. It highlights the need to align tools with human roles, organizational structures, and culture to ensure effective implementation (Mumford, 2000).

- The Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) Framework, which conceptualizes adoption as influenced by three contexts: internal technology, organizational capacity, and the external environment (Baker, 2012).

3. Dimensions of BIM–FM Interoperability through Open Standards

3.1 Technical Dimension

3.1.1 Current State and Limitations of IFC and COBie

3.1.2. Bidirectional Data Exchange: APIs and Cloud Integration

3.1.3. Semantic Enrichment and Linked Data

3.1.4. Digital Twins: Integrating IoT, AR, and VR

3.2. The Managerial Dimension

3.2.1. Implementation Challenges of ISO 19650

3.2.2. Ensuring Data Quality and Governance

3.2.3. Overcoming Human and Organizational Barriers

- Assemble a multidisciplinary change team;

- Define a clear vision and performance indicators (KPIs);

- Launch pilot projects to test new workflows;

- Provide training and monitor adoption;

- Reinforce change through ongoing leadership and realized benefits.

3.3. Strategic Dimension

3.3.1. Assessing Organizational Readiness via Digital Maturity Models

4. Synthesis of Challenges and Future Research Directions

4.1. Technical Gaps

- Scalability of Semantic Tools: Ontology-based frameworks like ifcOWL are promising but face complexity and performance issues at scale.

- Lack of Modular Ontologies: FM-specific ontologies that are both reusable and easy to implement are still underdeveloped.

- Limited Real-Time Integration: Bidirectional, dynamic BIM–FM synchronization remains rare despite the availability of APIs.

- Weak AI Integration: Semantic BIM data is not yet fully leveraged for predictive maintenance or fault detection.

4.2. Managerial Gaps

- OIR–AIR Misalignment: Poor linkage between high-level organizational goals and asset-level data leads to ineffective handovers.

- Unclear Roles and Weak Governance: Fragmented workflows and unclear accountability compromise data quality.

- Low BIM Literacy: Resistance to change and skill gaps among FM staff slow adoption.

4.3. Strategic Gaps

- Unclear ROI: While OpenBIM is seen as beneficial long-term, few studies quantify its impact in measurable terms.

- Understudied Policy Effects: The influence of national mandates on FM digital readiness is not well documented.

- Lack of Maturity Models: There is no widely accepted model to benchmark digital readiness for OpenBIM in FM.

5. Analytical Value of the Review

- An Integrated Three-Dimensional Framework: The literature is organized into technical, managerial, and strategic dimensions, supporting cross-disciplinary understanding of BIM–FM interoperability.

- A Conceptual Model for BIM–FM Transformation: The review synthesizes how open standards enable the transformation of building data into actionable operational intelligence.

- Critical Gap Mapping: It systematically identifies research limitations and outlines future directions relevant to both academia and industry.

- Bridging Academia and Practice: By assessing implementation challenges and policy contexts, the review provides practical insights for practitioners, developers, and decision-makers.

6. Conclusion

- Technically, while standards such as IFC and COBie provide a foundation for data exchange, they face limitations in semantic richness, real-time integration, and AI readiness. Advances in web-native formats, semantic web technologies, and AI-driven knowledge graphs offer more scalable and context-aware data ecosystems.

- Managerially, issues such as unclear information requirements, absence of data commissioning, and resistance to change continue to hinder adoption.

- Strategically, quantifying ROI remains difficult, and the lack of lifecycle-based policy incentives limits broader implementation.

- Develop interoperable ontologies that are lightweight, modular, and FM-aligned.

- Integrate natural language interfaces to reduce technical barriers for FM professionals.

- Explore contractual models that reward data quality and lifecycle value delivery.

- Advance cross-sector digital maturity models for benchmarking and planning.

- Evaluate the long-term impacts of policy mandates, not only on compliance but also on innovation and organizational learning.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIR | Asset Information Requirements |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| BEP | BIM Execution Plan |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| BMS | Building Management System |

| BRICK | Building Relationships in Context and Knowledge (ontology) |

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| COBie | Construction-Operations Building information exchange |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| EXPRESS | Exchange of Product model data representation (STEP-based language used in IFC) |

| FM | Facility Management |

| FM-DMM | Facility Management Digital Maturity Model |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| O-DF | Open Data Format (IoT standard) |

| OIR | Organizational Information Requirements |

| O-MI | Open Messaging Interface (IoT standard) |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| REST | Representational State Transfer (web architecture style) |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| TOE | Technology–Organization–Environment |

| TCO | Total Cost of Ownership |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| WebGL | Web Graphics Library (used in web-based 3D visualization) |

Appendix A

Appendix A

| Theme | Topic | Implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Enrichment | ifcOWL ontology for structured data | Formal logic, SPARQL query, compliance checking | (Beetz et al., 2009; Pauwels & Terkaj, 2016) |

| COBieOWL as extension of COBie | Enhances data expressiveness for FM delivery | (Farias et al., 2015) | |

| Modular domain ontologies for FM | Increased clarity and reusability | (Kang, 2017; Kim et al., 2018) | |

| Semantic Enrichment (AI) | NLP/GNN to structure dark data | Unlocks unstructured logs, builds knowledge graph | (L. Wang & Chen, 2024; Zhu et al., 2023) |

| IFC/COBie Limitations | Omission of geometry, inconsistent classification | Challenges for FM spatial reasoning | (Kumar & Teo, 2020; Lee et al., 2021) |

| Real-time Exchange | ifcJSON, ifcXML via APIs | Improved web compatibility | (Chamari et al., 2022; Chatsuwan et al., 2025; Moretti et al., 2020) |

| IoT Integration | MQTT, BACnet, O-MI/O-DF protocols | Feeds real-time sensor data into FM dashboards | (Deng et al., 2021; Su & Kensek, 2021) |

| IoT-BIM Fusion | Web-based DT with IFC + sensors | 3D spatial visualization of environmental data | (Chamari et al., 2022; Chatsuwan et al., 2025) |

| GIS+BIM for FM | Integration of spatial/geographic info | Improved navigation, asset location accuracy | (Congiu et al., 2024) |

| ISO 19650 Implementation | OIR/AIR misalignment | Need for clearer definition of FM-related info | (Ashworth et al., 2023; Chatsuwan et al., 2025; Tsay et al., 2022) |

| ISO 19650 Visualization | Process modelling to simplify adoption | Graphical tools improve understanding | (Abanda et al., 2025) |

| Data Governance | Data Commissioning protocol | Improves accountability and handover quality | (Patacas et al., 2020; Tsay et al., 2022) |

| Change Management | Socio-technical roadmap (5 phases) | Aligns human–tech transformation | (Ba et al., 2023) |

| Organizational Barriers | FM teams lack BIM literacy | Requires training and leadership | (Cavka, 2017; Gordo-Gregorio et al., 2025; W. Wang et al., 2025) |

| Strategic ROI | Lifecycle value and risk mitigation | Beyond short-term cost focus | (Ashworth et al., 2023; Lavy et al., 2019) |

| Public Policy | Mandates for IFC/COBie in procurement | Drives industry-wide adoption | (Godager et al., 2024) |

| Digital Maturity Models | FM-DMM with 7 key dimensions | Enables benchmarking and progress tracking | (Aliu et al., 2024) |

| Lifecycle Contracting | Aligning incentives across phases | Addresses the incentive gap | (Ashworth et al., 2023) |

References

- Abanda, F. H., B. Balu, S. E. Adukpo, and A. Akintola. 2025. Decoding ISO 19650 Through Process Modelling for Information Management and Stakeholder Communication in BIM. Buildings 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmajeed, M. G. 2023. A Multi-Stakeholder Information Model to Drive Process Connectivity In Smart Buildings. Birmingham City University. [Google Scholar]

- Abideen, D. K., A. Yunusa-Kaltungo, P. Manu, and C. Cheung. 2022. A Systematic Review of the Extent to Which BIM Is Integrated into Operation and Maintenance. In Sustainability (Switzerland). MDPI: Vol. 14, Issue 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, A. A., N. R. Muhamad Ariff, S. A. A. Sh Said, D. S. Ametefe, D. John, T. M. Dugeri, and M. Isah. 2024. Adopting Systematic Review in Conceptual Digital Maturity Modelling: A Focus on Facilities Management Sector. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology 52, 1: 332–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, S., M. Dillinger, and K. Körkemeyer. 2023. BIM guidance to optimise the operational phase: defining information requirements based on ISO 19650. Facilities 41, 5–6: 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzran, S. A., K. F. Ibrahim, J. H. M. Tah, and F. H. Abanda. 2019. Assessment of Open BIM Standards for Facilities Management. In Innovative Production and Construction. WORLD SCIENTIFIC: pp. 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. 2012. The Technology–Organization–Environment Framework. pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Z., Q. Wang, C. Chen, Z. Liu, L. Peh, and R. Tiong. 2023. Change Management of Organizational Digital Transformation: A Proposed Roadmap for Building Information Modelling-Enabled Facilities Management. Buildings 14, 1: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, J., J. van Leeuwen, and B. de Vries. 2009. IfcOWL: A case of transforming EXPRESS schemas into ontologies. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 23, 1: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, F. G., A. C. P. Martins, J. M. Franco de Carvalho, C. A. F. de Souza, J. C. L. Ribeiro, K. M. L. César Júnior, and D. S. de Oliveira. 2025. IFC framework for inspection and maintenance representation in facility management. Automation in Construction 174: 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui, Y., Z. Lafhaj, P. Yim, L. Ducoulombier, and B. Bennadji. 2020. Natural language processing model for managing maintenance requests in buildings. Buildings 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavka, H. B. 2017. UNDERSTANDING THE TRANSITION TO BIM FOR FACILITY OWNERS. The University Of British Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Chamari, L., E. Petrova, and P. Pauwels. 2022. A web-based approach to BMS, BIM and IoT integration: a case study. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. M., R. J. Dzeng, and Y. J. Wu. 2018. An automated IoT visualization BIM platform for decision support in facilities management. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatsuwan, M., M. Ichinose, and H. Alkhalaf. 2025. Enhancing Facility Management with a BIM and IoT Integration Tool and Framework in an Open Standard Environment. Buildings 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. C. P., W. Chen, K. Chen, and Q. Wang. 2020. Data-driven predictive maintenance planning framework for MEP components based on BIM and IoT using machine learning algorithms. Automation in Construction 112: 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congiu, E., E. Quaquero, G. Rubiu, and G. Vacca. 2024. Building Information Modeling and Geographic Information System: Integrated Framework in Support of Facility Management (FM). Buildings 14, 3: 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M., C. C. Menassa, and V. R. Kamat. 2021. From BIM to digital twins: A systematic review of the evolution of intelligent building representations in the AEC-FM industry. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 26: 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M. K., V. Venkatraj, M. Ostadalimakhmalbaf, F. Pariafsai, and S. Lavy. 2019. Integration of facility management and building information modeling (BIM). Facilities 37, 7/8: 455–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, K. 2020. Building Information Modelling and Asset Management: Semantic and Syntactic Interoperability. Oxford Brookes University. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, T. M., A. Roxin, and C. Nicolle. 2015. COBieOWL, an OWL Ontology based on COBie standard. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 9415: 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, B. C., R. Codinhoto, M. M. Fabricio, J. C. Estrella, C. M. Neves Ribeiro, J. M. Dos Santos Bueno, and J. P. Doimo Torrezan. 2022. Development of a BIM and IoT-Based Smart Lighting Maintenance System Prototype for Universities’ FM Sector. Buildings 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gispert, D. E., I. Yitmen, H. Sadri, and A. Taheri. 2025. Development of an ontology-based asset information model for predictive maintenance in building facilities. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 14, 3: 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godager, B., K. Mohn, C. Merschbrock, and L. Huang. 2024. Exploring the Enterprise BIM concept in practice: The case of Asset Management in a Norwegian hospital. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 29: 549–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo-Gregorio, P., H. Alavi, and N. Forcada. 2025. Decoding BIM Challenges in Facility Management Areas: A Stakeholders’ Perspective. Buildings 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFMA, and Autodesk. 2023. Optimizing Building Management with a Lifecycle Approach. Available online: https://it.ifma.org/optimizing-building-management-with-a-lifecycle-approach/.

- Jiang, S., L. Jiang, Y. Han, Z. Wu, and N. Wang. 2019. OpenBIM: An Enabling Solution for Information Interoperability. Applied Sciences 9, 24: 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordani, A David, and FAIA. 2010. BIM and FM: The Portal to Lifecycle Facility Management. Journal of Building Information Modeling. Available online: https://www.brikbase.org/sites/default/files/Pages%20from%20jbim_spring10-1.jordani.pdf.

- Kang, T. W. 2017. Object composite query method using IFC and LandXML based on BIM linkage model. Automation in Construction 76: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., H. Kim, W. Kim, C. Kim, J. Kim, and J. Yu. 2018. Integration of ifc objects and facility management work information using Semantic Web. Automation in Construction 87: 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaric, S., and D. R. Shelden. 2019. DBL SmartCity: An Open-Source IoT Platform for Managing Large BIM and 3D Geo-Referenced Datasets. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W., M. Karner, G. Traar, J. Henjes, and W. Sihn. 2018. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 51, 11: 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., and E. A. L. Teo. 2020. Perceived benefits and issues associated with COBie datasheet handling in the construction industry. Facilities 39, 5/6: 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S., N. Saxena, and M. Dixit. 2019. Effects of BIM and COBie Database Facility Management on Work Order Processing Times: Case Study. Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities 33, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. C., C. M. Eastman, and W. Solihin. 2021. Rules and validation processes for interoperable BIM data exchange. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering 8, 1: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoseiro Dinis, F., R. Rodrigues, and J. Pedro da Silva Poças Martins. 2023. Development and validation of natural user interfaces for semantic enrichment of BIM models using open formats. Construction Innovation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, N., X. Xie, J. Merino, J. Brazauskas, and A. K. Parlikad. 2020. An openbim approach to iot integration with incomplete as-built data. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 10, 22: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, E. 2000. Socio-Technical Design: An Unfulfilled Promise or a Future Opportunity? pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noardo, F., T. Krijnen, K. Arroyo Ohori, F. Biljecki, C. Ellul, L. Harrie, H. Eriksson, L. Polia, N. Salheb, H. Tauscher, J. van Liempt, H. Goerne, D. Hintz, T. Kaiser, C. Leoni, A. Warchol, and J. Stoter. 2021. Reference study of IFC software support: The GeoBIM benchmark 2019—Part I. Transactions in GIS 25, 2: 805–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, D., M. Briš Alić, and K. Čulo. 2024. The Issue of Estimating the Maintenance and Operation Costs of Buildings: A Case Study of a School. Eng 5, 3: 1209–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W., C. Cho, and M. Lee. 2023. Life Cycle Cost Method for Safe and Effective Infrastructure Asset Management. Buildings 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H., K. M. Al-Obaidi, A. Husain, and A. Ghaffarianhoseini. 2023. Digital Twins in the Construction Industry: A Comprehensive Review of Current Implementations, Enabling Technologies, and Future Directions. Sustainability 15, 14: 10908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, R. B., G. Miceli Junior, and P. C. Pellanda. 2025. BIM-FM integration through openBIM: Solutions for interoperability towards efficient operations. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 30: 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patacas, J., N. Dawood, and M. Kassem. 2020. BIM for facilities management: A framework and a common data environment using open standards. Automation in Construction 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patacas, J., N. Dawood, V. Vukovic, and M. Kassem. 2015. BIM for facilities management: evaluating BIM standards in asset register creation and service life. In Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon). Vol. 20, Available online: http://www.itcon.org/2015/20.

- Pauwels, P., and W. Terkaj. 2016. EXPRESS to OWL for construction industry: Towards a recommendable and usable ifcOWL ontology. Automation in Construction 63: 100–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, E., P. Pauwels, K. Svidt, and R. Jensen. 2019. Semantic data mining and linked data for a recommender system in the AEC industry. Proceedings of the 2019 European Conference on Computing in Construction 1: 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishdad-Bozorgi, P., X. Gao, C. Eastman, and A. P. Self. 2018. Planning and developing facility management-enabled building information model (FM-enabled BIM). Automation in Construction 87: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogage, K., and D. Greenwood. 2020. Data transfer between digital models of built assets and their operation & maintenance systems. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 25: 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, H. M. F., R. B. Ibrahim, A. F. Yusof, K. A. M. Khaidzir, M. Iqbal, and S. Razzaq. 2021. The role of interoperability dimensions in building information modelling. Computers in Industry 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhkhiz, S., and T. El-Diraby. 2023. Dynamic integration of unstructured data with BIM using a no-model approach based on machine learning and concept networks. Automation in Construction 150: 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G., and K. Kensek. 2021. Fault-detection through integrating real-time sensor data into BIM. Informes de La Construccion 73, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., D. R. Shelden, C. M. Eastman, P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, and X. Gao. 2019. A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: Present status and future trends. In Automation in Construction. Elsevier B.V: Vol. 101, pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkaj, W., and P. Pauwels. 2017. A Method to generate a Modular ifcOWL Ontology VFF-Virtual Factory Framework (EU FP7) View project ifcOWL View project A Method to generate a Modular ifcOWL Ontology. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320077313.

- Theißen, S., J. Höper, J. Drzymalla, R. Wimmer, S. Markova, A. Meins-Becker, and M. Lambertz. 2020. Using Open BIM and IFC to Enable a Comprehensive Consideration of Building Services within a Whole-Building LCA. Sustainability 12, 14: 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, G. S., S. Staub-French, and É. Poirier. 2022. BIM for Facilities Management: An Investigation into the Asset Information Delivery Process and the Associated Challenges. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, V., B. Naticchia, G. Bruno, K. Aliev, P. Piantanida, and D. Antonelli. 2021. Iot open-source architecture for the maintenance of building facilities. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittori, F., C. F. Tan, A. L. Pisello, A. Chong, and C. Miller. 2023. BIM-to-BRICK: Using graph modeling for IoT/BMS and spatial semantic data interoperability within digital data models of buildings.

- Wang, L., and N. Chen. 2024. Towards digital-twin-enabled facility management: the natural language processing model for managing facilities in buildings. Intelligent Buildings International 16, 2: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., M. Tao, S. Gong, L. Mi, L. Qiao, Y. Zhang, and X. Zhang. 2025. Revisiting what factors promote BIM adoption more effectively through the TOE framework: A meta-analysis. Frontiers of Engineering Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D., Z. Xia, Y. Zhu, and J. Duan. 2023. Overview of predictive maintenance based on digital twin technology. Heliyon 9, 4: e14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., P. Wu, and X. Lei. 2023. IFC-graph for facilitating building information access and query. Automation in Construction 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Research Focus | Proposed Action | Intended Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical |

Hybrid Semantic Frameworks | Combine ontologies (e.g., ifcOWL) with AI/NLP techniques | Enable scalable, machine-readable BIM–FM integration |

| Digital Twin Architectures | Integrate DTs with version control (e.g., blockchain) | Provide legally reliable “Digital Twins of Record” | |

| Managerial |

Validation of Change Roadmaps | Conduct longitudinal case studies using 5-phase models | Offer evidence-based transformation strategies |

| Data Commissioning Protocols | Define specs, validation steps, and sign-off workflows | Make FM-ready data a contractually enforceable output | |

| Strategic |

Lifecycle-Aware Contracting | Link BIM deliverables to FM incentives and outcomes | Align cross-phase stakeholder accountability |

| Policy Impact Measurement | Compare digital maturity across mandated/non-mandated cases | Guide effective national and sectoral policy design | |

| FM-DMM Benchmarking | Validate maturity models across sectors | Provide sector-specific digital readiness baselines |

| Stakeholder | Key Implication | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|

| Facility Owners & Operators | FM data must be treated as a contractual deliverable, not a passive handover | Define Data Handover Specifications; implement Data Commissioning processes; assess FM digital maturity |

| Project Managers & BIM Coordinators | Early alignment between OIR and AIR is critical to downstream interoperability | Co-develop AIR with FM teams; adopt API-ready, open-standard tools |

| FM Professionals | Usability is a barrier—tools must be tailored to non-technical users | Adopt semantic dashboards; introduce NLP-based query tools; invest in BIM literacy training |

| Software Developers / Vendors | Closed platforms hinder adoption—OpenBIM enables flexibility and integration | Build API-first platforms; support IFC, COBie, ifcJSON; incorporate AI/NLP-based features |

| Policymakers & Regulators |

Mandates must tie to outcomes, not just technical compliance | Include open-standard deliverables in procurement; reward lifecycle-based performance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).