1. Introduction

Since the early 2000s, the architecture, engineering, construction, and operation (AECO) industry is strongly growing [

1]. Especially the field of Building Information Modeling (BIM) has seen a noticeable increase in research publications since 2010, reflecting the rising interest and adoption of BIM within the AECO sector [

2]. As a result, BIM as a common planning practice is increasing across the industry [

3,

4]. With BIM, project information is enriched within a digital model. This data can be used to communicate information between different stakeholders and tools, supporting a consistent and coherent exchange of information, reducing time and errors during the planning and construction of a building. This allows tasks such as structural calculations, quantity and cost determination or construction scheduling to be optimized. However, BIM implementation varies greatly on an international scale due to several challenges, and overall adoption remains relatively low. While the exchange of information at geometric level already works well, especially for structural calculations and quantity calculations, there are problems with the exchange of data with energy simulation tools, especially with alphanumerical information. The inconsistent naming of properties, proprietary exchange formats and complex requirements lead to complications, especially when exchanging data between BIM and energy simulation tools. Interoperability - the ability to exchange information between different tools as seamlessly as possible - presents a significant barrier. These challenges are leading to not reliable and consistent data management within BIM tools and post-processing steps are required, hindering the potential of BIM [

5].

BIM review papers repeatedly emphasize interoperability as a fundamental challenge for the AECO industry. The most common problems identified include inconsistent data, lack of semantic precision, and the absence of standardized data exchange formats. Addressing these interoperability issues is considered essential for the full adoption of BIM [

6,

7]. In particular, the transfer of BIM data to Building Energy Models (BEM) or Building Energy Performance Simulations (BEPS) is a challenge. The conversion of a digital planning model into an energy model on a geometric level is a separate challenge in the BIM to BEM process, but is not the focus here. The exchange of alphanumeric information, i.e. metadata such as the thermal transmittance of a wall, is the focus of this work. Especially in the context of BIM to BEM planning processes, solving semantic challenges is critical for the implementation of early design optimization. Each project, company, BIM and BEM tool has its own alphanumeric information, in order for different programs to communicate the information with each other, 2 points are necessary. Firstly, it must be available and exportable and secondly, it must be understandable (semantic). Standards can be helpful here for both points. Standards can help to define what information should be available and how this information should be labeled. This ensures the completeness and comprehensibility of exchange requirements. Addressing semantic challenges could significantly improve the interoperability of BIM to BEM workflows [

8]. While semantics is a fundamental problem of interoperability in BIM to BEM exchange, the correct provision, maintenance and coordination of alphanumeric information in the model is another major challenge. Standards help to define requirements and describe properties, but managing this information in the models (BIM and BEM) and between the models, as well as in the database, remains a problem.

Databases for parameter standardization are used to standardize the exchange requirements. However, this approach does not do justice to the current state of software and practice. The standardizations do not do justice to the large number of complex requirements and the associated volumes of alphanumeric information. Many areas of the AECO sector are not covered and the standardizations cannot map the project- and tool-specific requirements. In addition, the standards are often not integrated into the models. As a result, databases with exchange standards often only serve as archives and cannot be meaningfully connected in practice [

9]. Especially in the planning phase and during the data exchange between BIM and different tools for energy simulations, these rigid and inert constructs are an obstacle to early energy design optimization.

The challenges addressed in the following work can be summarized as follows. (1) Semantic problems due to different designations (2) Mapping information due to complex requirements (3) Flexible and adaptable structures. The identified challenges in alphanumeric interoperability motivate the present work: How can project and tool-specific parameters make the integration of BIM and BEM more efficient and to what extent can flexible, toolchain-based approaches close the existing gaps?

Interoperability was recognized as a central problem in the BIM2IndiLight project [

10]. The aim was to develop a BIM2BEM framework that connects Autodesk Revit with DALEC - a web-based tool for thermal, daylight and artificial lighting simulation [

11]. Standardized properties and the use of IFC [

12] play a key role in optimizing building performance in the early planning phase achieving interoperability at the semantic level.

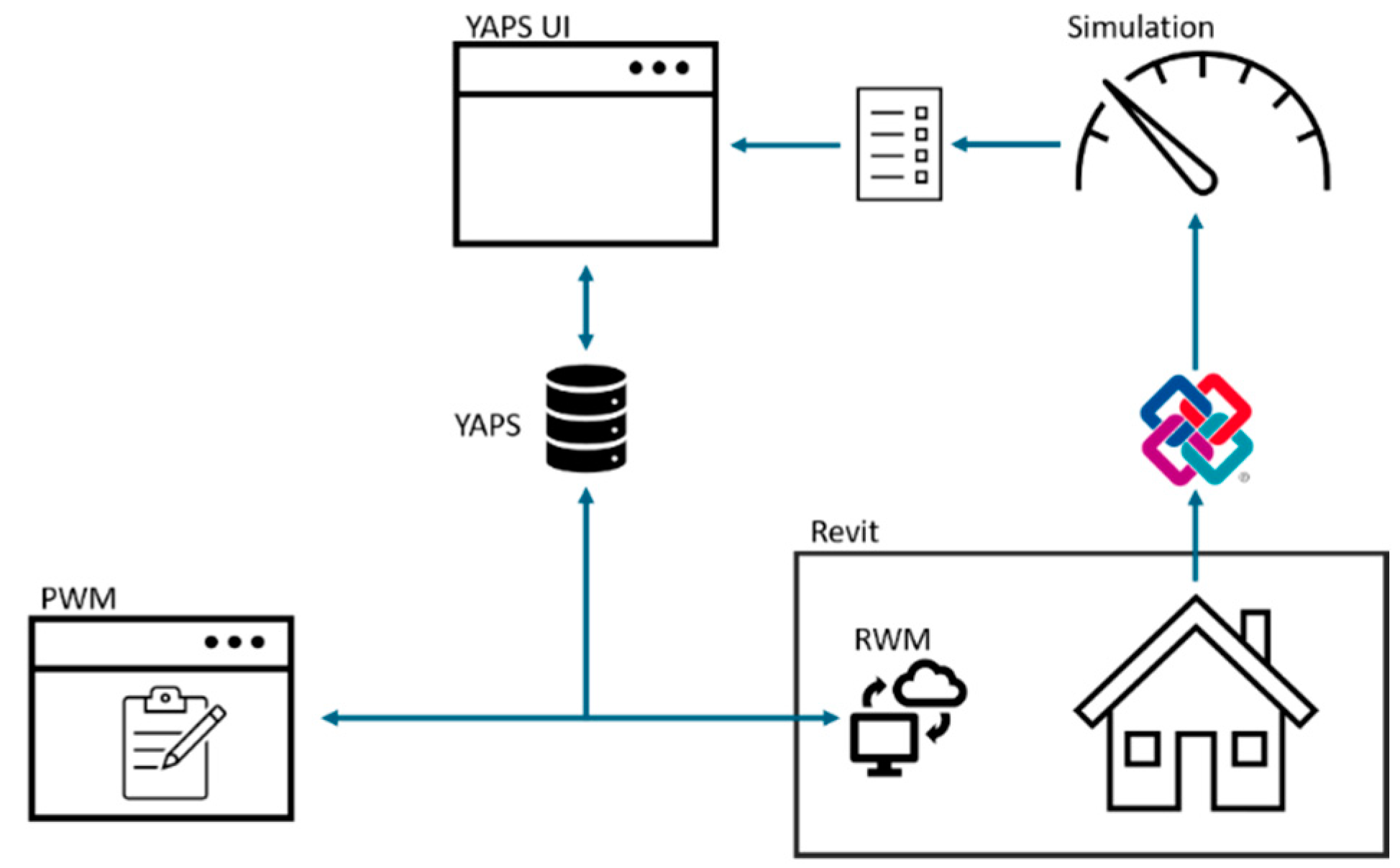

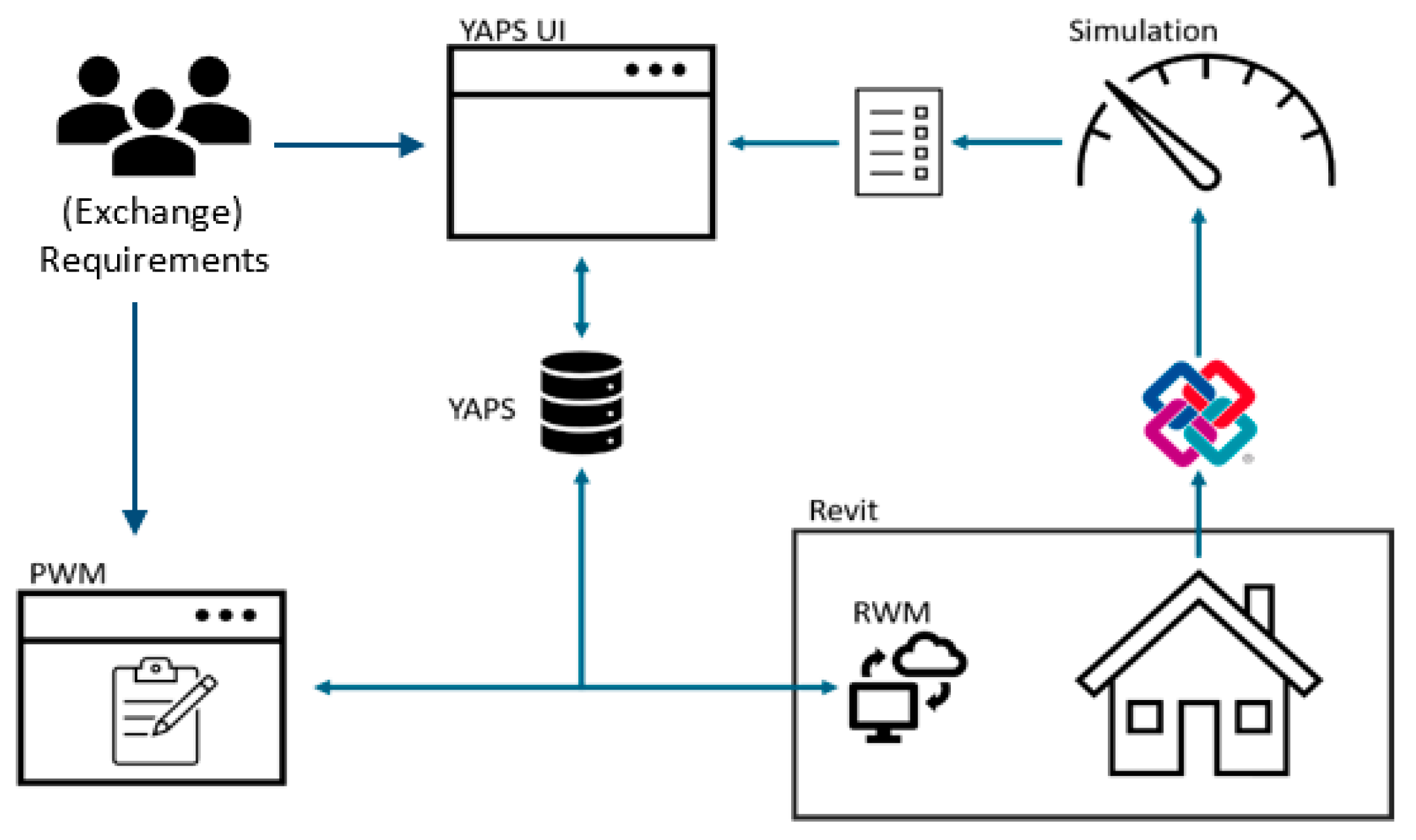

The experience that pure standardization without a functional link to BIM tools is insufficient motivated the follow-up project BIM2BEM-Flow. This developed a web-based platform (YAPS), which is used to manage project and tool-specific parameters and integrate them into BIM applications using defined workflows (PWM and RWM). (

Figure 1).

The basis of the approach is the mapping of alphanumerical information between different tools. The integration of exchange parameters, with a stored mapping of different BEM/simulation tools, in the BIM application ensures that the IFC export works correctly depending on the use case of the current work processes

This article provides the outcomes from the finished BIM2IndiLight project and the current BIM2BEM-Flow project and presents an overview of interoperability approaches in BIM2BEM research. It is divided into three sections: (I) the results of the BIM2IndiLight project, (II) the creation of the web-based parameter management platform and (III) a discussion of the findings.

2. Theoretical Background

The integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Building Energy Modeling (BEM) holds significant potential for enhancing energy performance during early-stage building design. While BIM serves as a centralized platform for data aggregation and management, BEM focuses on simulating and optimizing energy outcomes [

13]. However, despite advancements in both domains, seamless data exchange between BIM and BEM remains hindered by persistent interoperability challenges. These challenges are coming from fragmented workflows, inconsistent parameter definitions across tools, and a lack of standards[

14,

15]. This section critically examines the conceptual foundations of BIM-to-BEM integration, identifies key barriers, and evaluates emerging solutions to bridge these gaps.

2.1. BIM and BEM: Definitions and Synergies

A clear distinction must be drawn between the

building information model (a digital asset enabling stakeholder collaboration [

16]) and

building information modeling (the process of creating and leveraging this asset). The model serves as a dynamic repository for cost estimation, structural analysis, and—critically—energy simulations. When shared across stakeholders, it enhances design coordination, operational control, and simulation accuracy [

17].

The translation of BIM data into energy simulation inputs, termed

BIM2BEM [

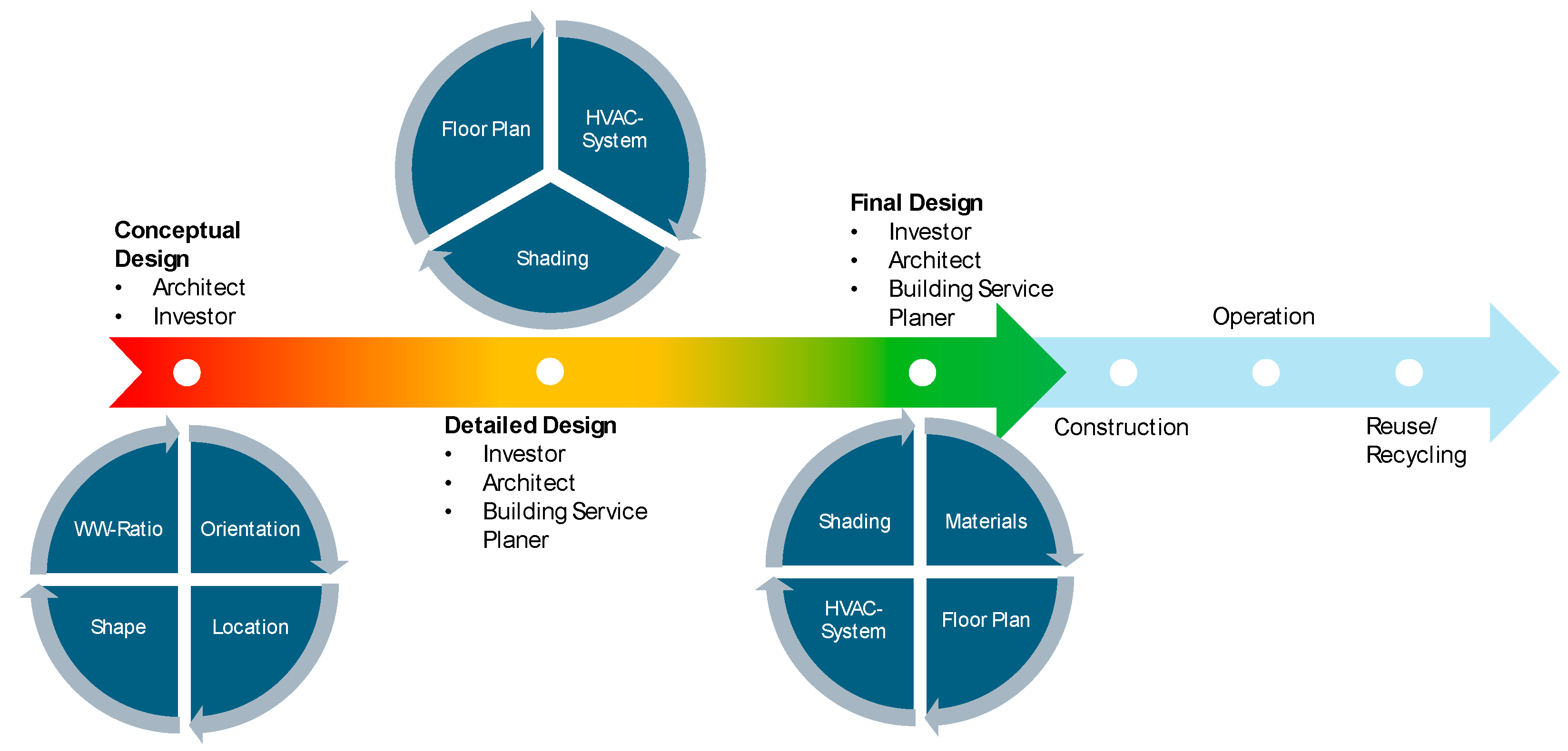

18], enables iterative energy optimization during the design phase. As illustrated in

Figure 2, this workflow operates through feedback loops, where simulations progressively refine design decisions to align with operational performance targets. However, its effectiveness hinges on

interoperability—the ability to exchange and consistently interpret data across tools. Three interoperability levels underpin reliable BIM2BEM workflows [

19]:

File/Syntax: Error-free file exchange between tools.

Visualization: Accurate geometric representation across platforms.

Semantic: Shared understanding of data meaning and context.

2.2. Interoperability Strategies in BIM2BEM

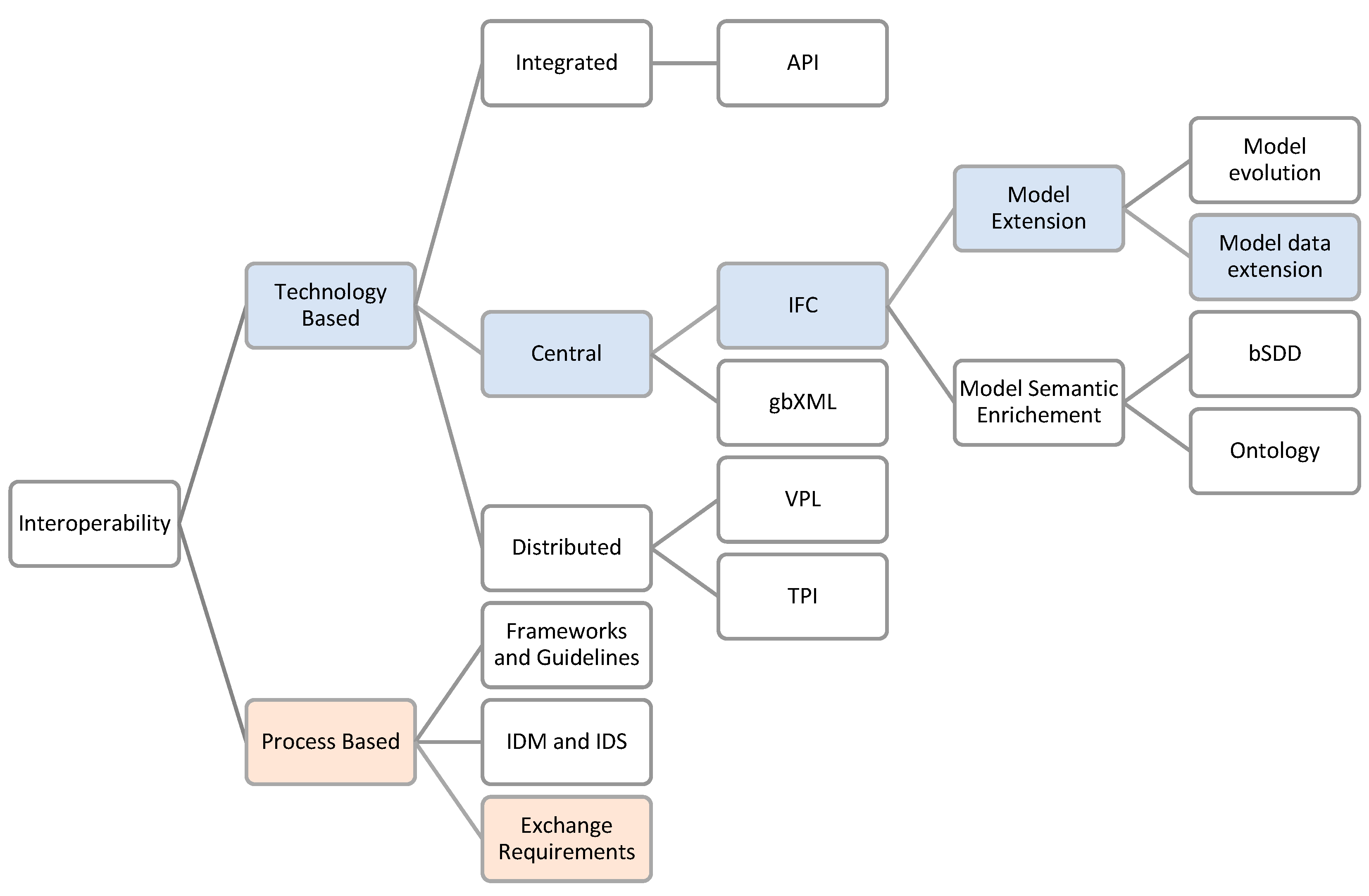

Current approaches to interoperability (

Figure 3) fall into two basic categories:

Technology-based approaches

Integrated: Tightly coupled tools (e.g., BIM-embedded BEM plugins) minimize geometry errors but limit flexibility [

20].

Central: Open formats like IFC/gbXML enable cross-tool compatibility but risk data loss during conversion [

21,

22].

Distributed: Visual programming languages (e.g., Grasshopper/Dynamo) bridge BIM and BEM engines (EnergyPlus, Radiance) but require technical expertise [

20].

Since IFC cannot accommodate all necessary data exchanges, there are several methods available for updating and extending missing entities. El Asmi et al. (2015) describe potential methods for extending IFC, as detailed in

Table 1.

Process-Driven Frameworks

Standardization initiatives like ISO 19650-1 and IDS (Information Delivery Specifications) address workflow fragmentation by [

24]:

Defining Exchange Requirements (ER): Specifying data needs per project phase.

Structuring Information Delivery Manuals (IDM): Aligning processes with stakeholder roles.

Enforcing IDS Compliance: Validating data quality and completeness.

All BIM-based BEM approaches have their strengths and weaknesses, but many struggle to optimize the design process during the early project stages.

The following table provides an overview of issues identified in various studies [

20,

25,

26,

27], along with potential solutions to these challenges.

In the BIM2IndiLight and BIM2BEM-Flow projects, a

combined approach was selected, and the methods used are highlighted in

Figure 3 (blue and pink). By using a combined approach, the following challenges are to be improved:

-

Repetitive Project/Model Preparation:

-

BEM Tools Lack User-Friendliness:

-

Time-Consuming and Redundant Workflows:

-

Integration Challenges:

The preparation and post-processing of the digital asset, as well as the conversion and adaptation of BEM formats (e.g., converting formats, adjusting IFC files, and adding missing data in specific BEM tools), requires a deep understanding of building physics and the entire process, from the early design stages to the detailed design phase. Standardization, which reduces individual procedures while yet supporting the overall workflow, can help to resolve some of this complexity. Standards such as ISO 17412-1, ISO 29481-1, and ISO 19650-1 seek to address two major challenges: simplifying the BIM process and providing precise definitions of exchange criteria. These standards help to ensure that BIM processes and data transfers are well-structured and clear, resulting in more effective project workflows.

3. Standardization

As outlined in

Table 2, implementing standards is key to overcoming BIM integration challenges, including BIM-to-BEM processes. Standardizing processes, concepts, and data models creates a unified framework that supports project management, aligns stakeholder expectations, and reduces errors [

28]. In information management, this approach aims to:

Enable efficient and effective data transfer,

Reduce unnecessary data exchange, and

Streamline decision-making with focused information [

29].

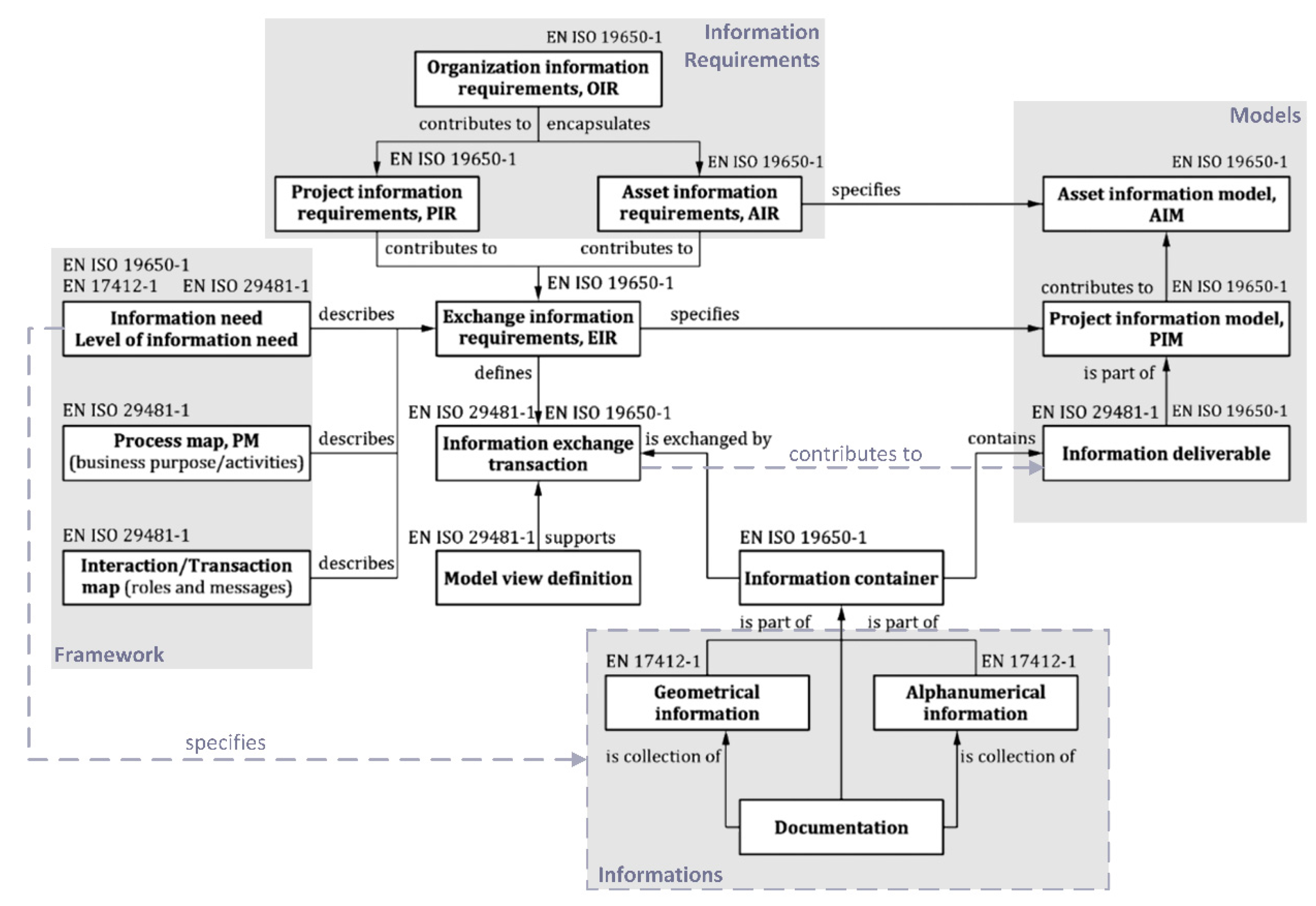

International Standards

International standards, such as those depicted in

Figure 4, harness technology to ensure smooth interoperability while meeting information exchange requirements (e.g., EIRs, BEPs). The ISO 19650 series, introduced in 2018, lays the groundwork for BIM information management by defining key concepts and introducing LOIN—a framework that specifies the minimum necessary geometric, alphanumeric, and documentary details per EN 17412. Similarly, the ISO 29481 standard details IDMs, which connect construction processes with precise information specifications, leading to improved data quality and availability. Together, these standards work to create a clear, organized BIM workflow that minimizes misunderstandings. While not every aspect of BIM can be standardized, focusing on exchange properties is essential for true interoperability, especially between BIM and BEM.

The standards provide a framework for defining and describing exchange requirements. Complex, time-consuming and often manual processes are leading to potential errors. Typically, companies enrich these requirements during their initial BIM projects and then update them as needed. However, interoperability continues to pose significant challenges in the BIM and BIM-to-BEM workflows [

23]. Addressing these issues early in the project lifecycle reduces difficulties in later stages. Instead of having project partners independently define exchange requirements, supporting standardized platforms and exchange requirements can save time, reduce costs, and minimize errors [

14]. Although standardized properties alone do not fully guarantee interoperability, they significantly reduce the need for later adjustments related to geometry, topology, and semantics caused by unmatching interfaces and translation issues [

31].

4. Methodology

To address the challenges of interoperability between BIM and BEM, this research is based on two interlinked projects: BIM2IndiLight and BIM2BEM-Flow. These projects span the period from 2017 to 2025 and represent a phased approach to address the issues of parameter standardization and workflow optimization.

The first project, BIM2IndiLight, focused on researching and validating exchange parameters for daylighting, artificial lighting and façade control systems. Through extensive data collection and analysis, over 400 parameters were identified, validated and documented to create a basis for standardized information exchange.

Building on these results, the second project, BIM2BEM-Flow, aimed to translate the theoretical findings into practical tools. In this phase, the focus was on developing a toolchain consisting of two web-based applications and a Revit plugin. The aim was to enable efficient management, assignment and coordination of project- and company-specific parameters and to simplify their transfer to BIM applications for energy simulations.

This section describes the methods used in these projects, including data collection, development processes, collaboration with stakeholders, and the integration of tools and technologies such as Revit. Together, these approaches form a holistic strategy to improve interoperability between BIM and BEM.

4.1. BIM2IndiLight (2018-2022): Research and Validation of Exchange Parameters for Daylight, Artificial Light, and Facade Control

The motivation behind the project was to expand the ASI property server with selected and validated properties from the areas of daylighting and artificial lighting, shading systems and their control in order to drive forward their standardization. The properties from the DALEC calculation tool were also to be compared with these standardized properties and, if not already mapped, included. In addition, the validated parameters were compared with IFC2x3 and the new IFC 4.3 standard (ISO standard 16739) to determine overlaps. Originally, the resulting standardized parameters of the work were published on the ASI Property Server, but due to a change in the structure and strategy of the ASI, these results are no longer available.

By offering pre-defined, standardized properties, detailed information (such as phase and exchange scenarios) can be accessed and implemented directly, bypassing the lengthy, complex, and error-prone process of manually defining these properties. As a result, using standardized properties can streamline tasks like those outlined in

Figure 5.

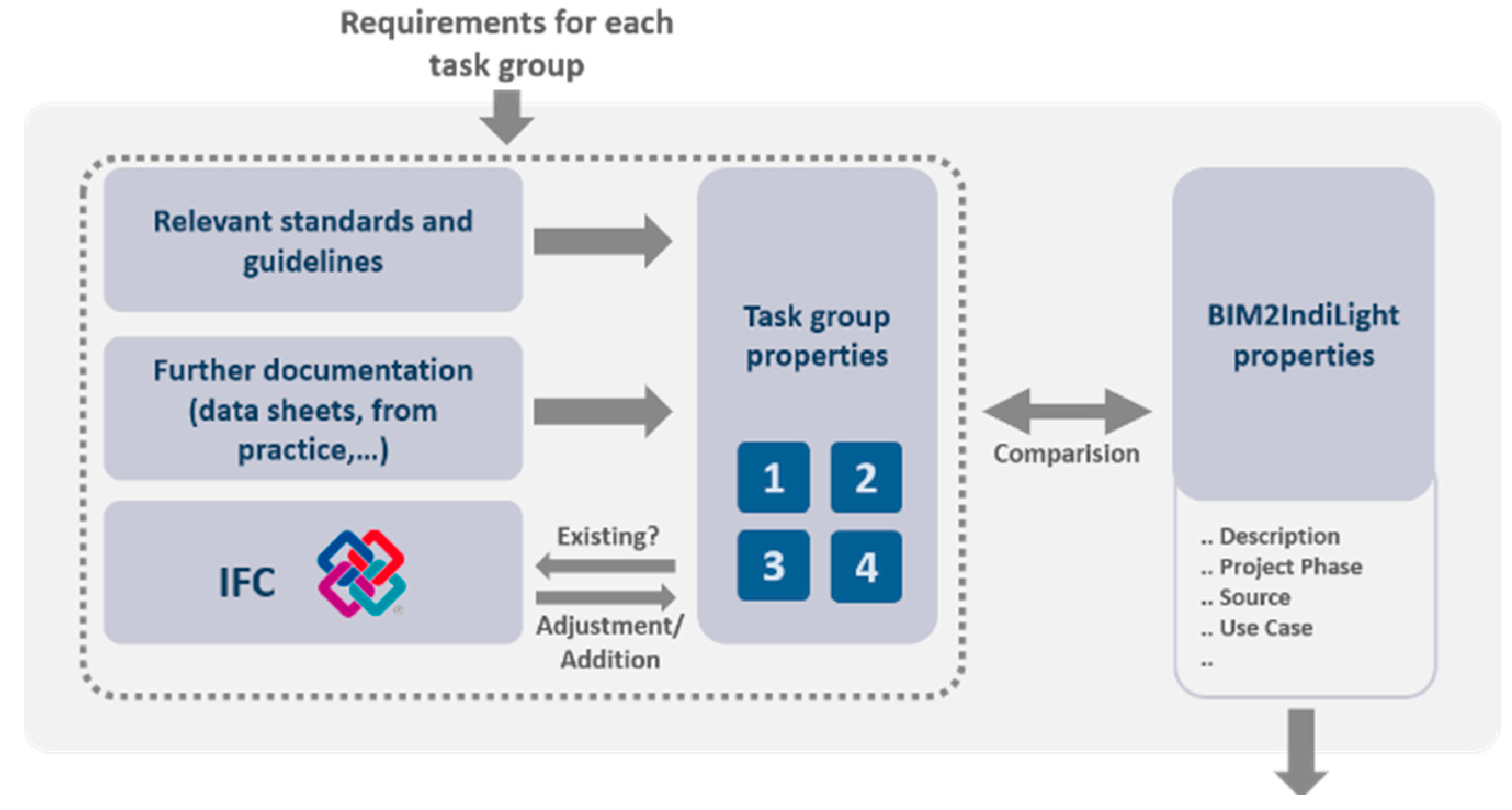

To facilitate the standardization of properties during the

BIM2IndiLight research project, four task groups were established, involving representatives from the University of Innsbruck, HELLA Sonnen- und Wetterschutztechnik GmbH, and Bartenbach GmbH (see

Figure 6). These groups identified the properties necessary for information exchange with the DALEC simulation tool and for describing daylight and artificial light-related components, such as shading devices, lamps, and luminaires. Additionally, properties related to sensors and controls were defined to support personalized daylight and artificial lighting control [

32]. This process followed a methodology previously used successfully in the standardization of component descriptions for the ASI Property Server, resulting in a dedicated BIM2IndiLight library [

33].

Relevant standards and guidelines were first reviewed to identify and document the most important properties (see

Figure 6). These properties were then enriched using practical data from literature, product datasheets, and additional documentation to provide comprehensive descriptions and current overviews of each component. After comparing these properties with those defined in the IFC standard, necessary modifications were made, and further details—such as descriptions, value lists, and normative references—were integrated into the datasets.

Throughout this process, various expertise areas contributed seamlessly to the property definition. For instance, the DALEC [

11] system’s essential parameters—largely derived from ISO 13790—were prioritized to support the BIM2IndiLight workflow between Revit and DALEC [

34], with a focus on daylight and artificial light as core elements. Concurrently, properties for control systems were assembled based on past project experience and guidelines (originating from the VEC-Module [

35]), ensuring alignment with standards such as EN 13790 [

36] and EN 17037 [

37]. This work also incorporated HVAC control properties from standards like EN 13779 [

38] and EN 16798 [

39] to bolster energy efficiency strategies.

In the daylight sector, properties were sourced from research-specific documents, product literature, and standards like DIN 14501 [

40] and DIN 410 [

41], with sensor and commissioning-related controls added and motor properties cross-checked against DIN 60034-1 [

42] and DIN 60043-5 [

43] standards. Finally, in the area of artificial lighting, experts gathered properties from technical standards and norms; this effort evolved through contributions from manufacturers, the Swiss lighting software community, the ZVEI BIM group, and a CEN task force [

44,

45]. The resulting list comprehensively covers both photometric and electronic lamp properties as well as detailed luminaire attributes—including naming, mounting, mechanics, electronics, lifetime, safety, and control aspects—ensuring robust support for simulation-assisted design from early-stage to detailed design.

4.2. BIM2BEM-Flow (2021-Ongoing): Development of the Web-Tool and Revit Plugin

During the BIM2IndiLight project, it became evident that merely providing standardized parameters without a functional link to tools limits the usability of the ASI Property Server. Due to the limitations of the existing database system, establishing such a connection was not possible. Consequently, the BIM2BEM-Flow follow-up project developed a new database system (YAPS) and workflow (PWM and RWM) (

Figure 1) that enables easier connections to new developments. Properties from the BIM2IndiLight project were transferred to the YAPS. BIM2BEM-Flow aims to establish a workflow-driven toolchain for defining exchange properties between different software tools in the BIM and BEM environments (e.g., Revit to DALEC). The specified properties will be automatically synchronized in the digital building model, allowing for the continued use of properties defined in BIM2IndiLight (

Figure 7).

Not only does the standalone provision of standardized parameters without a functional connection to BIM or BEM tools pose a challenge, but the rigid structure of the standard property server can also be a hurdle for users in the AECO industry. Many companies have their own property lists developed over time, and tools have specific requirements for properties, necessitating a more flexible approach [

46]. The lack of standardized procedures for integrating BIM and BEM, as well as interoperability issues, further complicate the process, highlighted by the need for more flexible and adaptable systems. These challenges underline the importance of developing more adaptable and user-friendly systems to meet diverse needs [

47]. The main challenge for BIM2BEM-Flow is, therefore, to offer reusable properties while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to changes.

As part of BIM2BEM-Flow, three applications were developed to support a consistent BIM workflow: (I) a web-based platform for creating, describing and managing company- or project-specific properties and their mapping (YAPS), (II) a web-based platform for creating workflows that outline a clear, comprehensive process (BIM tool, BEM tool, phase, use case, parameter library, and responsible parties) (PWM), and (III) a Revit plugin to coordinate this information within the BIM tool (RWM). This paper focuses on the YAPS (I).

Feedback from industry partners in the BIM2IndiLight project and practical application experience highlighted the need for a functional interface connection to demonstrate the server's practical value. A survey, conducted under the leadership of “Digital Findet Stadt” [

48], gathered insights from architects, planners, facility managers, BIM consultants, and research offices. The survey participants were also invited to a workshop where the BIM2BEM-Flow project concept was presented. This approach allowed for an early identification of needs and helped to specify the project requirements. In workshops and in direct discussions with participants, the project concept was well received and further discussions helped to fine-tune the requirements. In summary, the following needs were mentioned by the industry:

Based on this feedback, the web-based platform for managing company- and project-specific parameters was designed and implemented.

The database structure follows the IFC format, which, along with gbXML, is one of the only open exchange formats that support comprehensive building mapping and is compatible with most BIM tools currently available [

49,

50]. The objective of the database developed in BIM2BEM-Flow was not to provide a server with standardized parameters but to create a user-friendly application where company- and project-specific parameters can be defined and managed. This data belongs to the company or project stakeholders and can be modified, expanded, and reused in future projects by the participating companies. The parameters created can then be integrated into the building design through a Revit plugin. Although the database itself is manufacturer-independent, the plugin developed for BIM2BEM-Flow is specific to Revit, as the project participants use this software. Similar parameter management has been implemented by BIMQ [

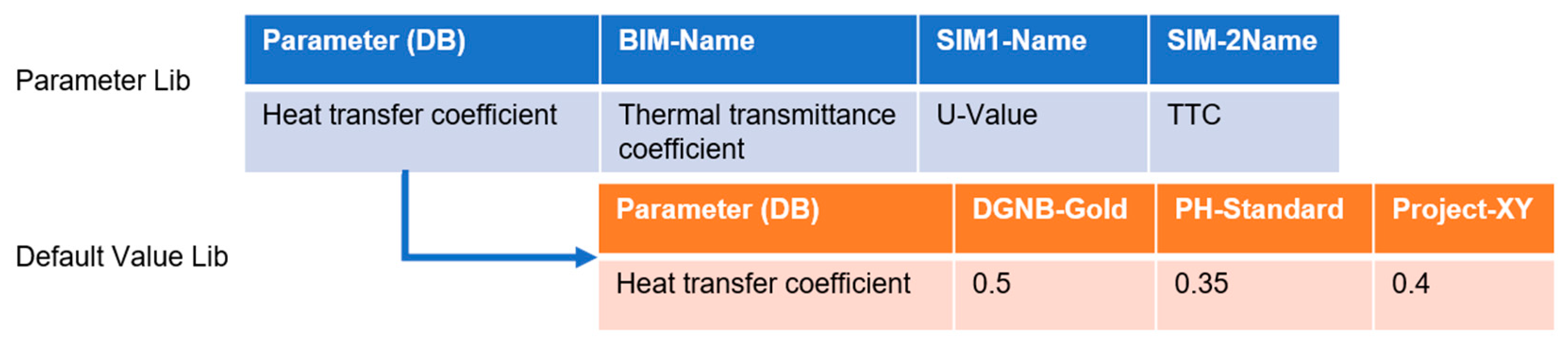

51]. However, the goal of BIM2BEM-Flow is to optimize the workflow from design to energy simulation, supporting energy-efficient building optimization. The requirements extend the database structure's functionality to include:

Mapping parameters (Server → BIM → BEM (Simulation))

Connecting default value libraries to parameter libraries

Defining threshold values for result certification/verification

Data import capability

Access to the data via external tools through an API

5. Results

The results of this research show the progress made in addressing the interoperability issues between BIM and BEM, with a focus on the exchange of alphanumeric information in the early design phase. The two projects, BIM2IndiLight and BIM2BEM-Flow, have made significant progress in both the standardization of exchange parameters and the development of practical tools to streamline workflows.

The first project, BIM2IndiLight, culminated in a comprehensive list of standardized parameters for exchange between BIM and BEM, focusing on critical aspects such as daylighting, artificial lighting and façade control. The validation process not only ensured the robustness of these parameters, but also provided valuable insights into their practical application in the AECO industry.

Building on these foundations, the second project, BIM2BEM-Flow, led to the development of two web-based applications and a Revit plugin. The toolchain developed is designed to support project- and company-specific parameter management and seamless integration into BIM to BEM workflows. With these tools, users can effectively define, assign and coordinate exchange parameters and increase compatibility during BIM to BEM exchange. The reviewed parameters from the BIM2IndiLight project are stored in the BIM2BEM-Flow database YAPS and made available for use.

This chapter presents the results of both projects and illustrates their contributions to improving interoperability and supporting the optimization of energy performance through standardized workflows and innovative tools.

5.1. Outcomes of BIM2IndiLight

In total, 454 properties were defined across the task groups. During a subsequent comparison, 26 instances of property overlap were identified. These overlaps involved properties from different packages representing the same information within the model. The naming and supplementary details could be identical or slightly varied. To resolve these overlaps, discussions were held among the concerned task groups, resulting in harmonized properties to prevent duplication (

Table 4). There is a total of 428 properties necessary for the DALEC simulation tool, as well as for describing model components related to daylight and shading systems, lamps, luminaires, and user-specific lighting controls. Existing IFC properties were examined and aligned with these new properties if they conveyed similar information. As shown in

Table 5 , roughly one-third of the DALEC properties correspond to IFC2x3 properties, offering a solid foundation for early design stages that primarily involve basic model content covered by IFC.

However, the agreement with properties for artificial lighting and daylight components was significantly lower. The ZVEI BIM group is actively working on the standardization of artificial lighting components, but only about 10% of the daylight properties and 2% of the sensor/control properties match the IFC2x3 properties. This is because these properties are more detailed and do not match the IFC standards directly. In summary, the IFC2x3 properties do not provide an adequate database for accurate component descriptions or effective energy simulations and lighting designs.

Table 5 shows the results from the individual sectors. While the ZVEI group has standardized artificial lighting properties for ONR CEN/TS 17623, over one-third of the DALEC properties are derived from standards, with the remaining sourced from additional documentation or specific research. For daylight components, nearly half of the properties come from standards and are further supplemented by component data sheets. Although sensor and control properties in building models lack standardization, approximately 72% are defined by existing standards and guidelines.

The LOIN is a framework that outlines the scope and level of detail for information to be exchanged. According to EN 17412-1 [

30], LOIN should include a combination of geometric information, alphanumeric data, and documentation. When defining LOIN, a distinction is made between geometric and alphanumeric data. As seen in

Table 6, the focus in each package is primarily on alphanumeric information, highlighting that a purely geometric representation of a building model offers limited value for simulation purposes.

The BIM2IndiLight project aimed to establish a practical workflow for the AECO industry. All investigated and defined properties were documented in the BIM2BEM-Flow database and will be made usable when the BIM2BEM-Flow results are released.

As part of the BIM2BEM-Flow project, the parameters from BIM2IndiLight were revisited and revised. Some parameters were merged, which was mainly due to duplicate parameters caused by a differentiation of different façade systems, and the number of parameters was reduced to 385. These parameters were aligned with the new IFC 4.3 standard. The 385 BIM2IndiLight parameters were checked for compliance with the IFC 4.3 standard using the Brutal Force method. This means that all IFC 4.3 property sets (644) including their parameters (3642) were read out and saved in a list. An algorithm was then used to generate a list of possible matches for each BIM2IndiLight parameter. For each parameter, the generated list was then manually checked for a match. This is necessary because a parameter can have a linguistic match, but the parameter is assigned to an IFC entity by the parameter set, which does not match the parameter from the BIM2IndiLight. For example, maintenance factor - window or maintenance factor - heating, makes a difference. The results of the match were then assigned to one of the 4 categories (0 - No assignment, 1 - Clear assignment, 2- Assignment complex, 3 - Theoretically available but not quite correct). Assignment complex was chosen as a category because certain parameters are required in the early planning phase in particular, but if they are nested too deeply in the IFC, they are not represented in the design. For example, the maximum luminance on the façade as a limit value for glare protection is already relevant in the early planning phase, but this property is nested in the IfcSensor entity. However, it is far too early to place sensors in the early design phase. For the 385 parameters, no match could be determined for 40%, a clear match for 44%, a complex match for 11% and a theoretical match for 6% (

Table 7 Revision of BIM2IndiLight parameters against the IFC 4.3 standard). “Theoretically available but not quite correct” means that the results are not unambiguous and can certainly be interpreted differently.

5.2. Outcomes BIM2BEM-Flow:

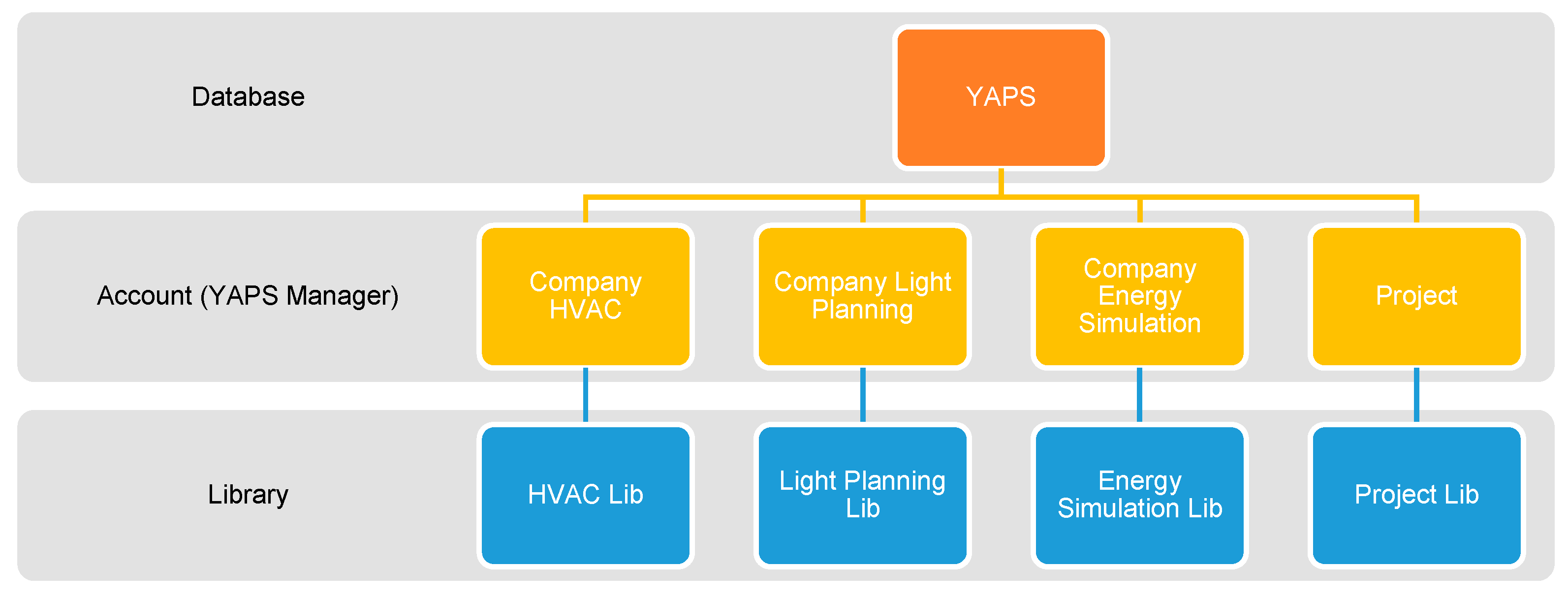

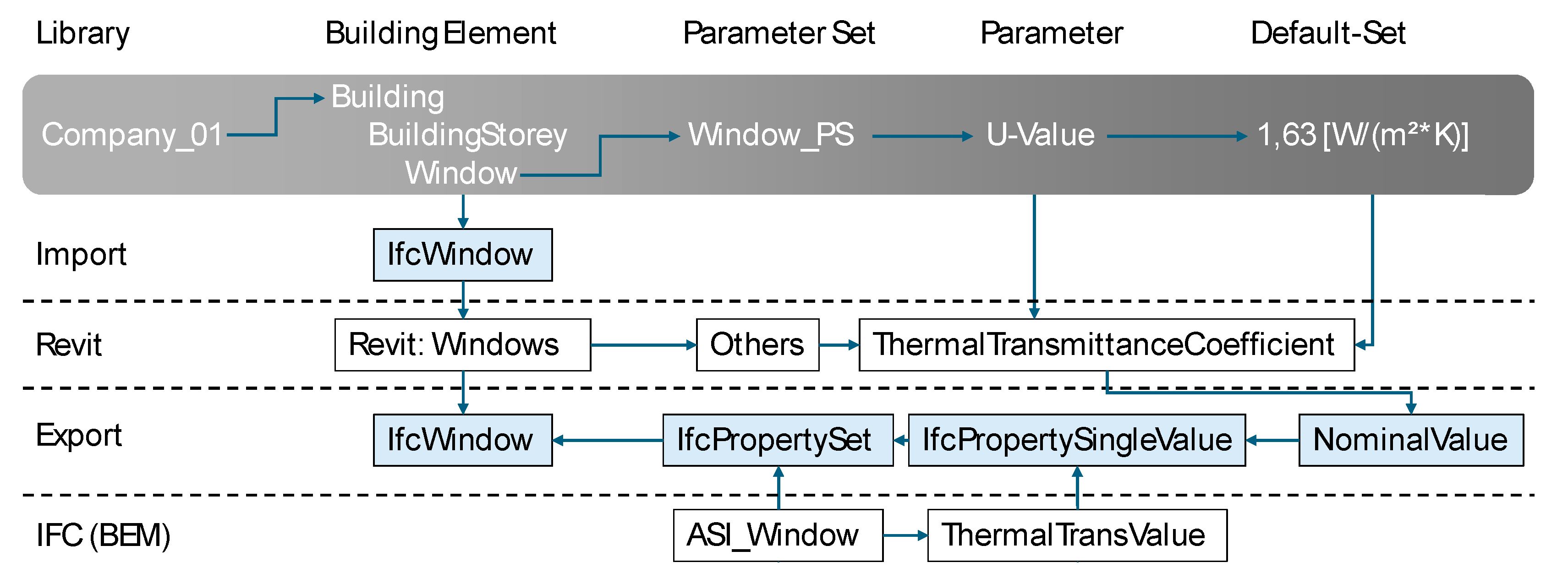

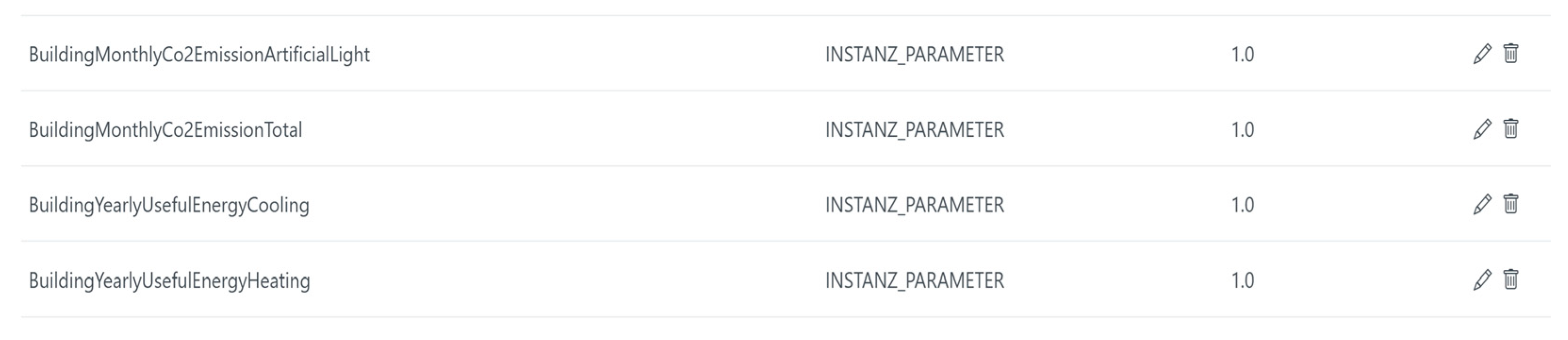

The project- and company-specific parameter management database (YAPS) allows for a realistic building structure depiction through virtual and physical building components, similar to IFC. Alphanumeric component and room information can be mapped using parameter sets. Default sets can be defined for early energy design optimization, allowing architects to use validated values during initial design and conduct simulations early on. A threshold value library is also included to customize the mapping of simulation results. However, the core of the database is property mapping, which ensures proper integration into BIM tools and validated alphanumeric export in IFC format.

A user-friendly UI was developed to facilitate the creation, editing, and management of libraries. Companies or project-stakeholders can now create and manage property-libraries that are flexible and reusable. For example, a company can have a single, ever-expanding library that, through mapping, supports multiple tools. Alternatively, separate libraries can be created for different simulation tools like EnergyPlus, PHPP, DALEC, etc. Since the mere availability of standardized parameters on the server was insufficient for practical connection and usability, the results from BIM2IndiLight were transferred to the BIM2BEM-Flow platform, and initial mappings were created for the Revit2DALEC and PHPP tools.

5.2.1. Database Structure

In addition to the web UI for creating libraries, parameters etc., libraries can also be imported completely via a CSV structure. This means that existing data records, which are often in Excel format, can be easily transferred to the database. The database also has a modular structure and an API, making it easy to connect external tools and work with the database data. To use the platform, a company must register. Once registered, the company can activate its employees for an administration account. Those managing parameters carry a high level of responsibility, as all subsequent processes, including simulation, rely on the accuracy of the data stored on the server (see

Figure 8, YAPS Manager or Property Manager). Users can create libraries, such as a comprehensive company library or one specifically for a project. These libraries can be shared with other companies involved in the same project. The coordination of libraries among different project participants or companies occurs within the Project Workflow Manager (PWM), which was developed in BIM2BEM-Flow and is mentioned here for context.

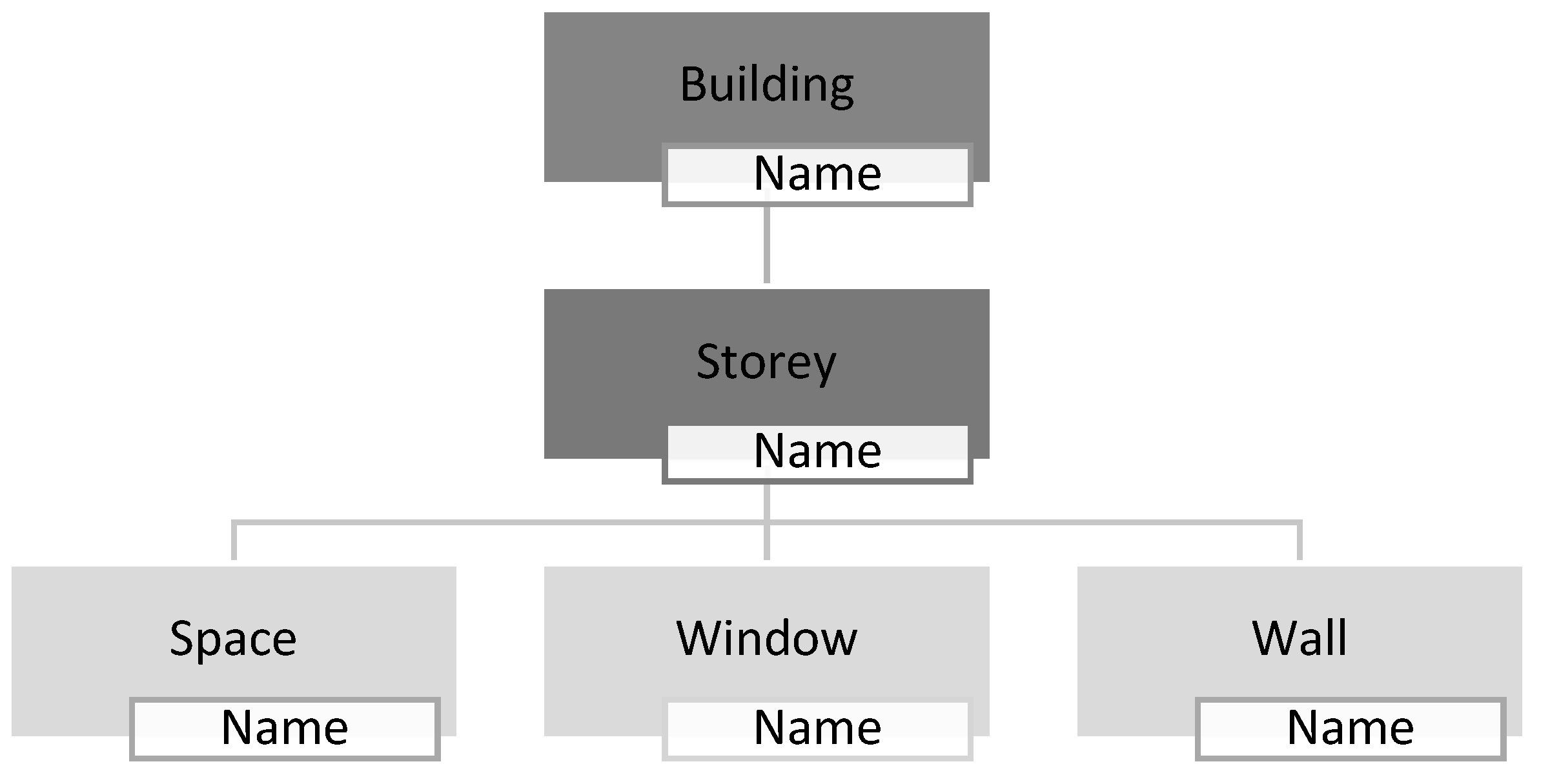

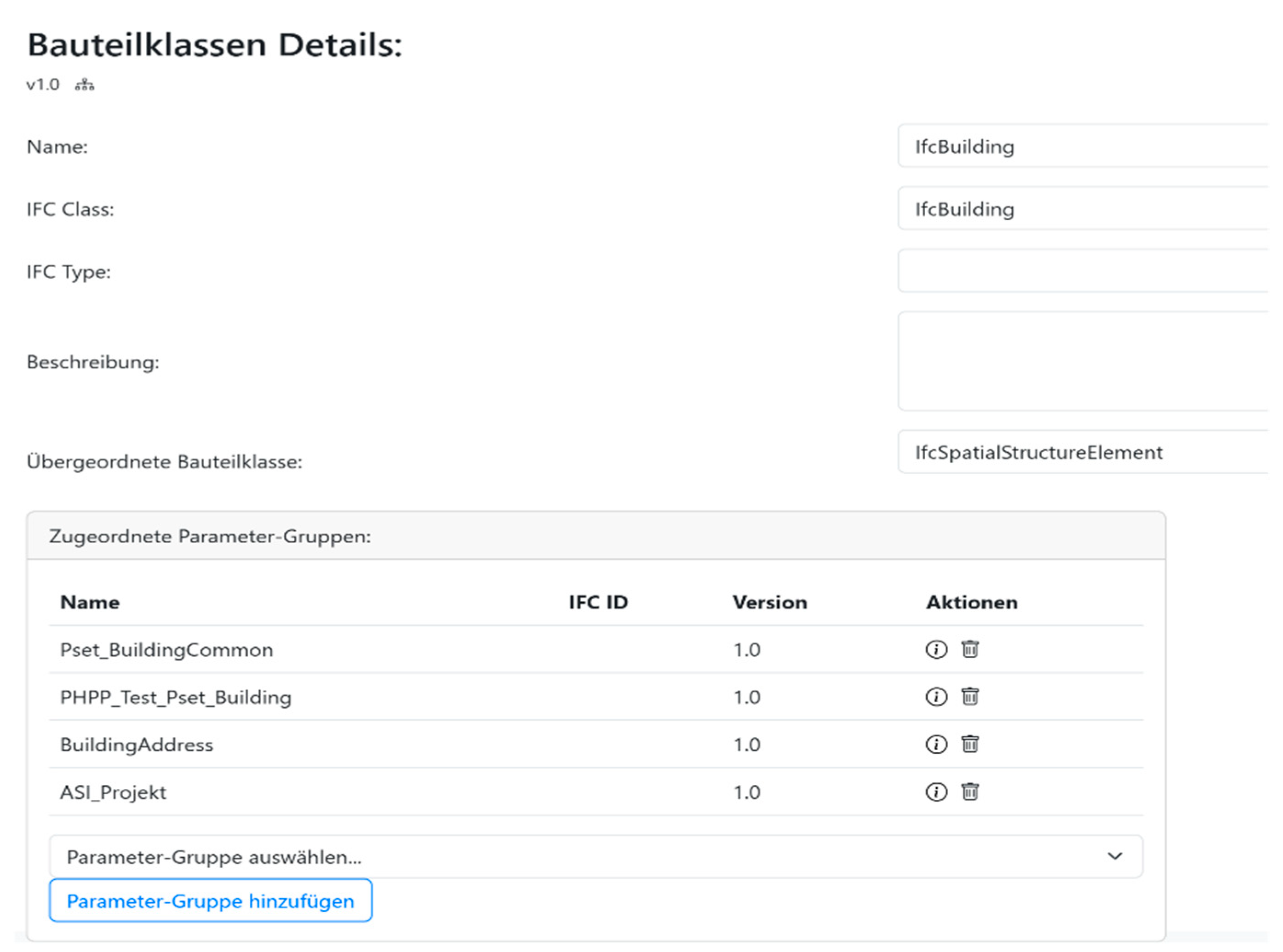

A library consists of component classes (

Building Element), which can be either virtual (e.g., room, project) or physical (e.g., window, wall) and can be linked hierarchically. This hierarchical structure is crucial for inheritance, allowing parameters (e.g., name) to be passed from parent to child components (

Figure 9).

Building Element

A library element includes attributes such as name, IFC class, optional type assignment, description, and associations with parameter groups (see

Figure 10). Linking to an IFC class is essential, as Revit's import process depends on this classification (e.g., Building → IfcBuilding). For example, if the IFC import settings in Revit include Building → IfcBuilding, the component class "Building" is mapped to the Revit

BuildInCategory (Revit-API specific element) “Building Model". Also, by working with the open standard IFC entities the database structure stays manufacture independent.

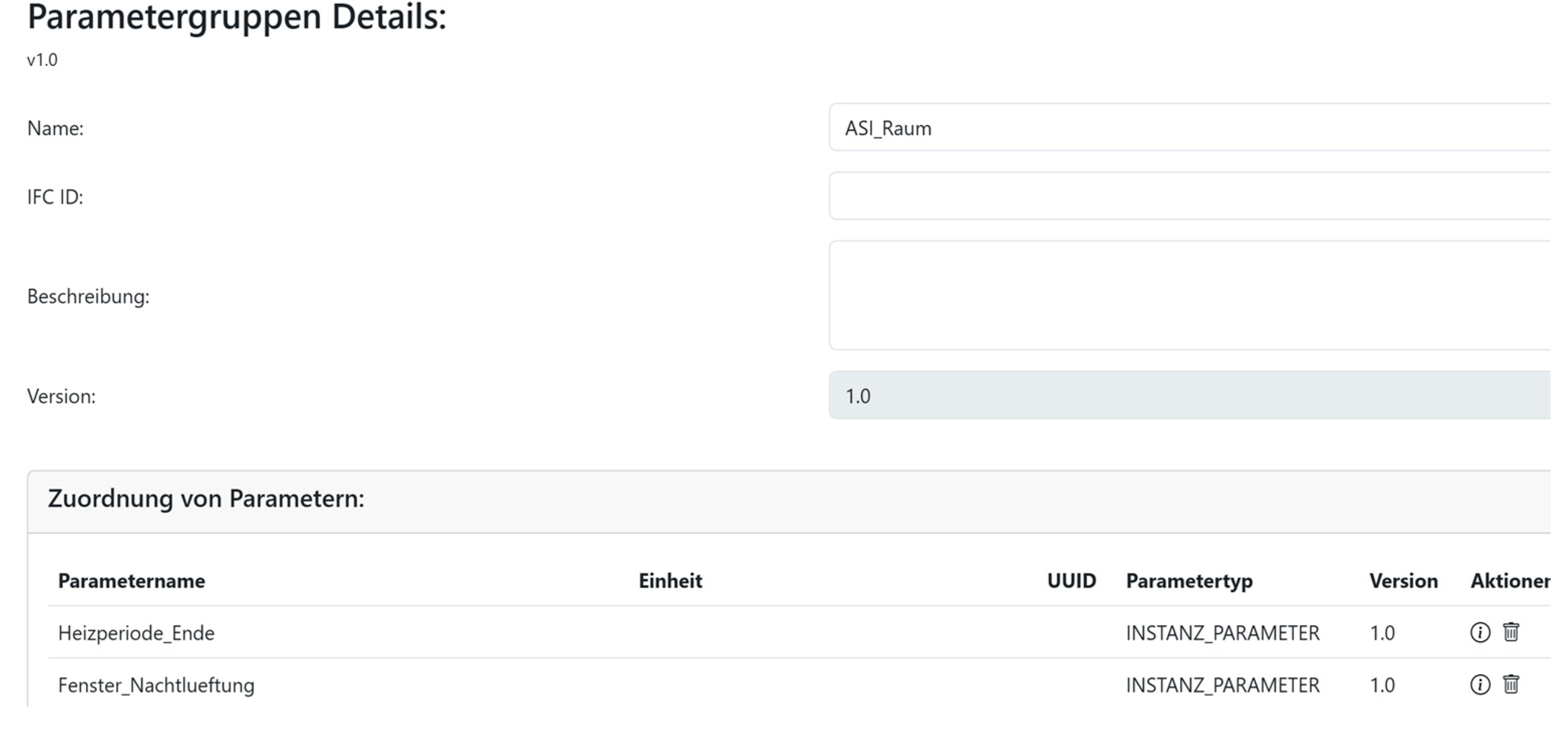

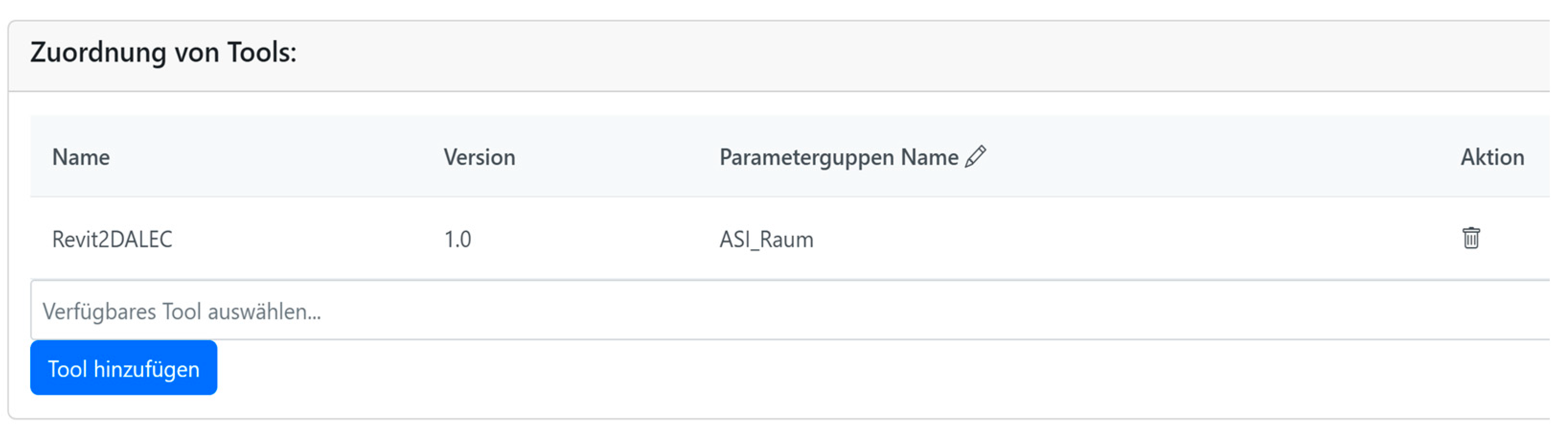

Parameter group

A parameter group includes a name, an optional IFC ID which can be used for mapping, and an optional description, along with a list of parameters and a mapping list for various simulation applications (

Figure 11). The parameter group name is specific to the database (e.g., ASI_Raum), but it can store multiple mappings for IFC export (

Figure 12). E.g., for Revit2DALEC import to work correctly, the room parameters must be stored within the IfcPropertySet ASI_Raum, as Revit2DALEC looks for this specific property set.

A parameter group can either be assigned to an existing component class, or an existing parameter group can be linked to a component class.

Parameter

A parameter is defined using the following attributes, the mandatory fields are marked with an *:

| ∙ Name* |

∙ Value type * |

∙ Relevant from phase |

| ∙ Building-Smart GUID |

∙ Discipline |

∙ Description |

| ∙ UUID |

∙ Data type* |

∙ Documentation |

| ∙ Dimensioning * |

∙ Parameter type* |

|

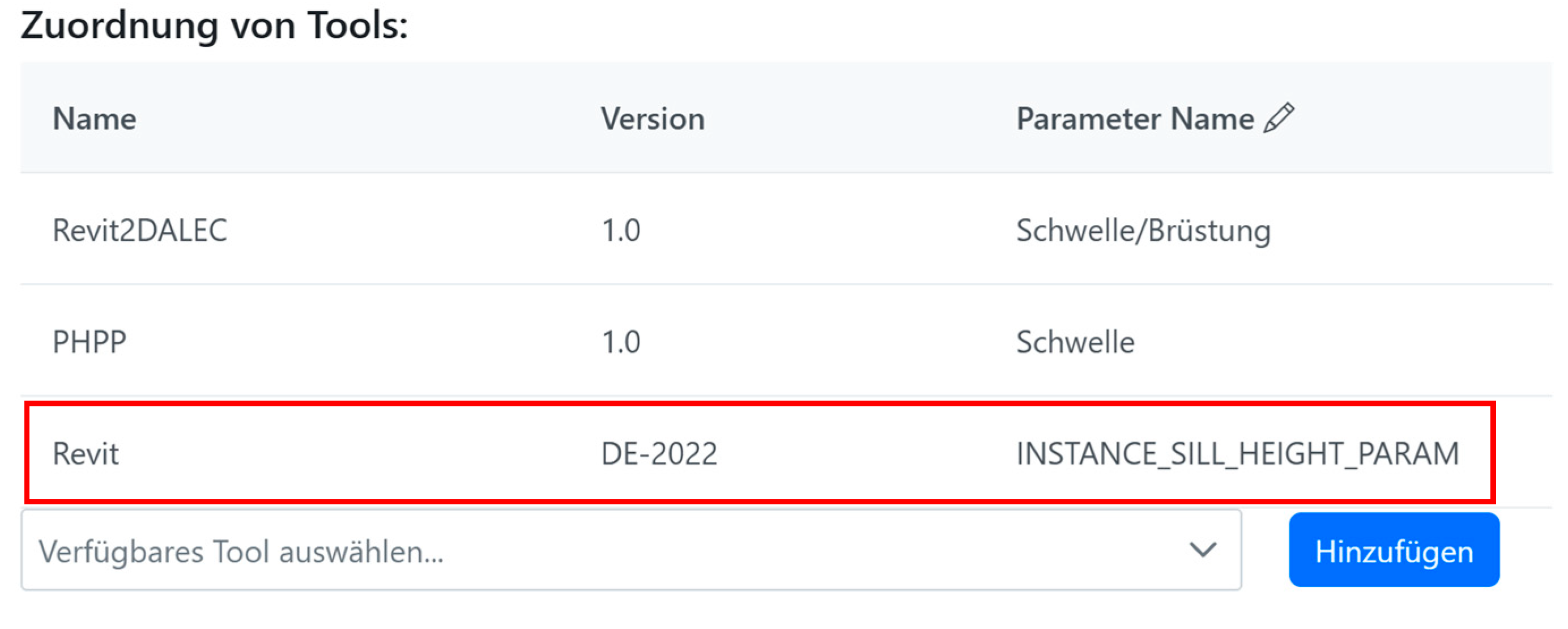

Parameters can belong to one or more parameter groups, where they are then listed. Each parameter can also have mappings for BIM or simulation tools (

Figure 13). The parameter name in the library is flexible, but mappings ensure that it is exported to the IFC with the correct name for the specific simulation tool. Use cases can be assigned to the parameter in line with ÖNORM A6241-2 Although phase and use case fields are currently optional, they will be used in the future to align parameters with the BIM model’s phase and use case for better clarity.

The "dimensioning" attribute links to internal Revit API dimensioning variables, while the "data type" maps to Revit's internal data types. The "value type" can either be free-form or a predefined list (e.g., Usage – Office | Meeting | Kitchen | Toilet, etc.). Similar to Revit, the "parameter type" can be set to either "Instance" (specific to a component) or "Type" (applies to all components of the same type). If a parameter lacks a mapping for the BIM tool, it is newly created; otherwise, the existing BIM property is adopted based on the mapping (

Figure 13, red box). Proper mapping with the Revit API internal naming is crucial.

At this point, it should be mentioned that Revit was used as a BIM tool in the project, which is why there is often a mention of linking to Revit properties. This is essential for the Revit Workflow Manager plugin, which integrates and manages properties from the server, but the structure of the database is tool-independent and should also be linked to other BIM tools in the future.

Default-Sets

Supporting BIM2BEM workflows involves not just parameter implementation in the BIM model and correct IFC export but also providing default parameter values during the early planning phase. This allows planners to use default values without having to define them themselves. Each parameter library can contain multiple default value sets, which can be used to fill properties with values within Revit (

Figure 14).

The described server structure is illustrated in

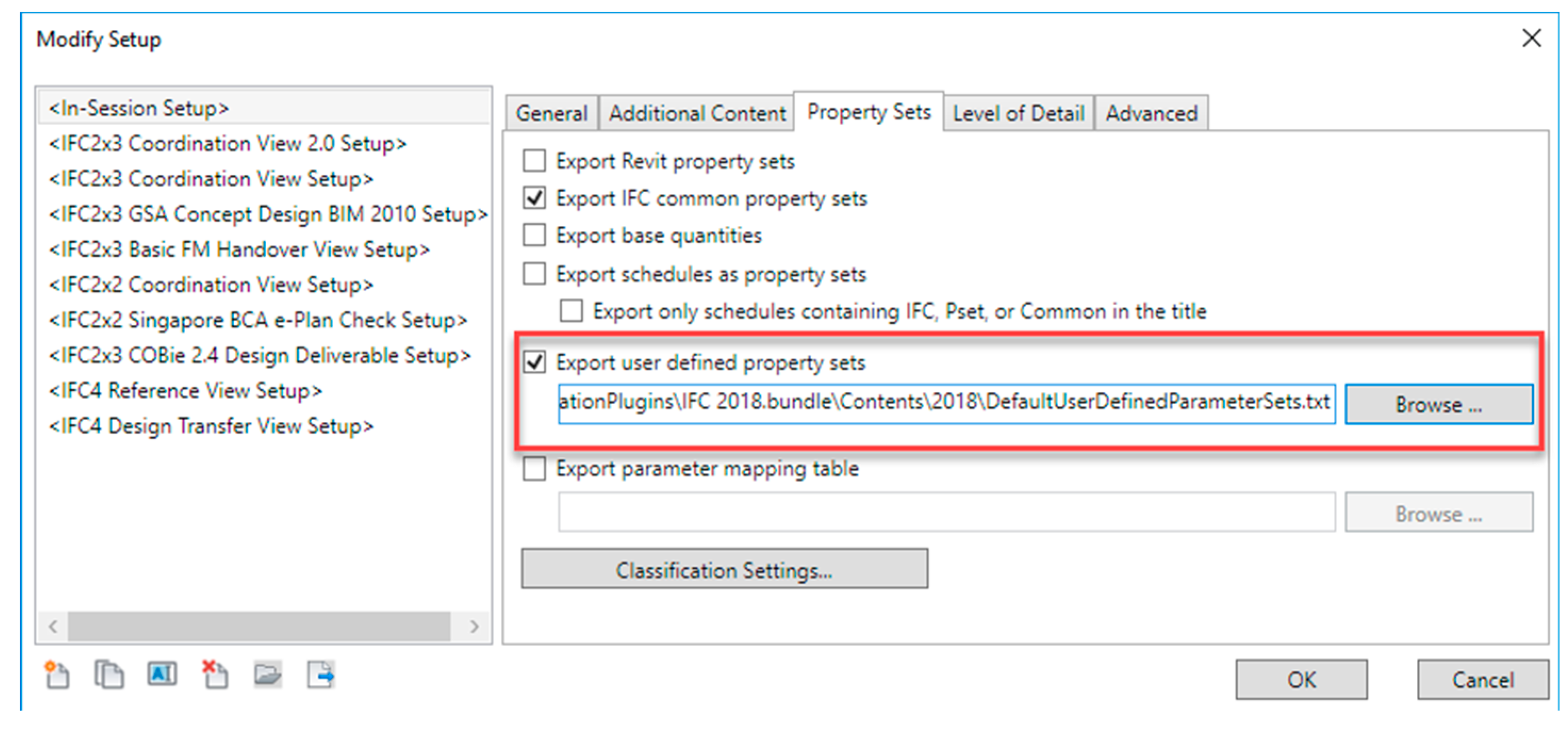

Figure 15. Companies or projects manage libraries that consist of building elements with properties and default values imported through IFC assignments using the Revit’s import options for mapping IFC entities to Revit building elements (BuiltInCategory). Building elements can have multiple parameter sets, each containing several parameters. To import the data into Revit, mapping to at least one IFC element is required. Parameters in Revit are filled either manually or by assigning them default values from the library.

The Revit "BuiltInCategory" is linked to an IFC element through Revit's export options. The "Export user-defined property sets" option (

Figure 16) allows for the creation of a mapping file for Revit IFC export. This mapping file is automatically generated by a BIM2BEM-Flow-specific program.

Threshold-Values

The BIM2BEM-Flow project also includes a web-based application for the standardized presentation of simulation results from different tools, using CSV mapping. Although only briefly mentioned here, this application enables users to customize which simulation results are displayed. The parameter database is used to map result and limit value libraries. For this purpose, a new library is created on the server, where result parameters (e.g., annual heating demand, primary energy demand for artificial light, daylight autonomy) are defined instead of input parameters.

In the "Limit values" tab, one or more threshold value sets can be defined, using parameters from the result library. These sets can represent standards, such as the Passive House (PH) standard with a maximum annual heating demand of 15 kWh/(m²*a). Thresholds can be defined as minimum, maximum, or within a specific range. For example, while a minimum daylight autonomy is important, excessive values can cause glare or overheating. The defined threshold value library can be used in the web-based tool to visualize simulation results.

Figure 18.

Exemplary List of threshold values.

Figure 18.

Exemplary List of threshold values.

5.2.2. Side note Project Workflow Manager (PWM) and Revit Workflow Manager (RWM)

The entire BIM2BEM flow project consists of a 3-stage workflow, which results from 3 applications. (I) A web-based application for defining and managing properties as well as their mapping to BIM and simulation tools (YAPS), (II) a web-based application for defining workflows (PWM), these represent a clearly defined and completed use case and (III) a Revit plugin (Revit Workflow Manager - RWM) to integrate and manage the information in the BIM model and ensure the export of a validated IFC. The content of this publication focuses on the database, but in order to provide an overall picture of the work, the PWM and RWM applications are briefly explained.

Due to the described functionality of the database, a property library can now look like this

Table 8.

A parameter of the library has a mapping to a BIM tool (Revit) and several simulation tools (IES VE, DALEC, PHPP) and several default sets that can represent different standards such as DGNB Gold, PH standard, etc. A workflow can now be described using the PWM. This consists of the responsible BIM person and the tool used, as well as a responsible simulation person and the tool used. In addition, the use case and the project phase are defined, which have not yet been used functionally, but the option should be available for future work. In addition, the library used from the YAPS must be selected (

Table 9).

The user can now log in to RWM and can only see workflows assigned to its account. If the user now imports this workflow into the BIM model, only the properties that are necessary for the Workflow (the simulation tool) are imported into the model, in this example DALEC. The user can now fill the properties manually or automatically with the values from the default set. Referring to

Table 8 and

Table 9, only the properties “

Thermal Transmittance Coefficient” and “

Visible Light Transmittance” would now be imported. By selecting the default set

PH Standard, the values would be filled with 0.6

and 0.7 [-] and the parameters would be exported to the IFC via the mapping as “

U-Wert” and “

VLT”.

6. Discussion

The integration of BIM and BEM is fundamental for optimizing energy performance in early design stages. However, the process is challenged by extensive, repetitive project and model preparation. Every new project often demands a fresh definition of exchange requirements—even when companies have developed internal standards over many years. This repetitive preparation is intensified by evolving design requirements and boundary conditions. In addition, the inherent disconnect between architects workflows and the complexity of BEM tools creates conflicts in collaborative processes, further hindering energy optimization decisions.

6.1. Standardization

Standardization remains a foundation for reliable information exchange between BIM and BEM. The BIM2IndiLight project demonstrated that defining and validating over 400 standardized parameters can provide a robust foundation for property mapping. Standardized parameters are meaningful during the process of EIR, ER, and IDM definition and can offer a basis for mapping of information. They also ensure uniform communication among stakeholders, reducing errors when transferring data between diverse software platforms. Of course, this is only the case if both application sides follow the standards. But, BEM software in particular does not yet support alphanumeric information and its import.

However, standardized parameters alone are insufficient. The rapid evolution of design requirements and the nearly infinite number of possible parameters make manual updating both time-consuming and error-prone. Moreover, cross-border projects are troubled by conflicting national standards, underscoring the need for a more dynamic, adaptable approach that makes parameter libraries more flexibel with default value libraries for practical implementation.

6.2. Toolchain Development

To bridge the gap between standardization, a need for flexible requirement adaptation and practical application, the BIM2BEM-Flow toolchain was developed. This innovative system integrates a web-based property management server (YAPS), a workflow management interface (PWM), and a Revit-integrated plugin (RWM). Key features of this toolchain include:

Mapping Parameters (Server → BIM → BEM): The toolchain ensures that parameters are correctly mapped from the central database into BIM models and then translated for use in energy simulation tools, thereby streamlining the data exchange process.

Connecting Default Value Libraries: By linking default value libraries directly to parameter libraries, the system provides validated, ready-to-use data that can be automatically assigned during the early design phase. This reduces manual input and minimizes errors.

Defining Threshold Values for Certification/Verification: The integrated framework allows users to set and manage threshold values for simulation results. This is crucial for establishing certification criteria (e.g., Passive House standards) and for verifying the performance of the design against energy efficiency benchmarks.

Data Import Capability and API Access: Recognizing that many organizations already manage data in formats such as Excel, the toolchain supports full data import functionality. Furthermore, an API facilitates access to and integration of the parameter data with external tools, enabling a seamless, automated workflow.

This approach not only addresses the disconnect between BIM and BEM by creating a centralized, flexible, and adaptable management system, but it also overcomes the essential limitations of existing BEM tools, which are often perceived as complex and not user-friendly. By providing an intuitive interface and automating the mapping process, the toolchain helps to reassign responsibilities clearly allowing property managers to oversee data accuracy and reducing the burden on architects.

6.3. Early Design Optimization

Early design decisions have a disproportionately large impact on building energy performance. Integrating BIM and BEM in the early planning phase not only accelerates the iterative design process but also ensures that energy simulations are closely aligned with the evolving architectural model. With the new toolchain, architects and planners can:

Quickly import workflow-based parameters and default values, ensuring model completeness from the outset.

Rely on automated parameter mapping to maintain consistency across different design phases—even as simulation requirements change from early planning to detailed execution.

Benefit from a system that minimizes redundant workflows. Instead of creating separate energy models manually for each design iteration, the integrated approach supports rapid, automated updates, allowing teams to focus on refining design alternatives.

Avoid duplication of work in BEM tools by providing important simulation data already in the IFC.

In summary, the combined approach of flexible and customizable parameters and a dynamic, integrated toolchain address major obstacles in BIM2BEM workflows. It reduces the repetitive work inherent in project/model preparation, mitigates the complexity of BEM tools, and provides a pathway for rapid, reliable energy optimization in the early design stages.

6.4. Specific Discussion on the YAPS

At the heart of the BIM2BEM-Flow toolchain lies the YAPS Parameter Server—a highly flexible, user-driven platform for managing exchange parameters. One of YAPS’s most notable strengths is its flexible structure, which allows users to freely create and organize libraries. This design freedom transforms YAPS from a mere parameter repository into a dynamic hub for knowledge sharing and customization. Because of its flexibility, YAPS can serve multiple roles:

Public Libraries and Standardization: YAPS supports the creation of public libraries that comply with industry standards. These libraries can be accessible for projects and organizations, providing a consistent and validated set of parameters for energy simulation and building performance assessment. In this model, simulation software companies have the opportunity to contribute validated libraries that are pre-mapped for tool-specific imports. This not only reinforces trust in the simulation process but also streamlines the integration of BIM data into BEM tools.

Private, Custom Libraries: Beyond public standard libraries, YAPS empowers individual companies and project teams to develop private, fully individualized libraries. These libraries can be tailored to reflect unique project requirements, specific company standards, or proprietary simulation processes. This adaptability ensures that, while there is a push towards standardization, there is also room for innovation and customization where needed.

Flexibility in Data Management and Mapping: The inherent flexibility of YAPS is further enhanced by its support for mapping functions that link standardized parameters with tool-specific requirements. Whether parameters are intended for a public standard library or a custom, private collection, the YAPS framework ensures that data remains interoperable across various BIM and BEM tools.

In summary, the YAPS Parameter Server is not just a static database but a versatile platform that can be used to address both industry-wide standardization and individual user needs. It enables a dual approach: on one side, promoting a shared, standardized basis that benefits the broader community; and on the other, offering the freedom for tailored, private libraries that meet the specific demands of companies and projects. This dual capability is essential for fostering both collaboration and innovation in the evolving landscape of BIM-to-BEM integration.

6.5. The Role of the YAPS-Manager in Ensuring Reliable Data Exchange

A key enabler of the YAPS Parameter Server’s success is the dedicated role of the YAPS-Manager. This role is vital for establishing consistent and reliable data, which in turn supports early design optimization by relieving planners of manual data management burdens. The YAPS-Manager is responsible for:

Creating and Curating Libraries

Developing Default and Threshold Libraries: Default libraries provide pre-validated, ready-to-use data for early design phases, while threshold libraries define critical performance benchmarks (e.g., energy efficiency limits) used for simulation verification and certification.

Ensuring Data Consistency and Reliability: By overseeing the creation and maintenance of these libraries, the YAPS-Manager ensures that data is consistent, accurate, and up-to-date. This reliability is crucial for seamless information transfer from the YAPS server through BIM to BEM simulation tools.

Facilitating Collaboration and Standardization: Public libraries, ideally created and maintained by reputable software companies or industry committees, set standardized baselines that can be adopted across multiple projects. This not only increases trust in the data exchange process but also streamlines interoperability among different tools and stakeholders.

In summary, the YAPS-Manager is the cornerstone that guarantees the success of the overall BIM-to-BEM integration process. Their expertise and oversight transform raw parameter data into a structured, reliable asset that supports efficient early design optimization and reduces the repetitive workload for planners. The establishment of public libraries further amplifies these benefits by providing standardized, validated parameter sets that enhance collaboration and promote industry-wide best practices.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

The standardization work of the BIM2IndiLight project resulted in the description and validation of around 400 parameters for daylight, artificial light, and façade systems. These standardized parameters form a solid foundation for defining exchange requirements and support consistent semantic communication between BIM and BEM. By integrating these parameters as a library into the BIM2BEM-Flow, a mapping for DALEC and PHPP was prepared.

Key Findings and Recommendations:

Comprehensive Parameter Libraries: The research has demonstrated that well-defined parameter libraries are essential. They not only provide consistency for early design simulations but also reduce manual rework. In our approach, these libraries are the backbone of the BIM2BEM workflow, supporting both project-specific needs and standardized exchange requirements.

Flexible, Toolchain-Based Integration: While standardized parameters lay the groundwork, flexible mappings—including default value libraries and threshold libraries—are necessary to address rapidly evolving project demands and cross-border differences in standards. This flexible toolchain approach enhances the interoperability between BIM and BEM by automating data validation and ensuring the correct export of IFC files.

Role of the YAPS- (Parameter or Property) Manager: A newly established role is critical to the process. The YAPS-Manager is responsible for creating, curating, and maintaining libraries. Public libraries maintained by reputable software companies or industry committees can not only reduce the workload for individual projects but also enhance data trust and consistency across the AECO sector.

Early Design Optimization: By integrating standardized parameters with default-values into the BIM model early in the design process, architects and planners can conduct energy simulations and performance assessments sooner. This early design optimization enables rapid iteration and more informed decision-making, which is crucial for improving overall building performance.

Revisited Research Questions:

(1) How can project and tool-specific parameters make the integration of BIM and BEM more efficient? Our findings show that standardized parameters—when combined with flexible mapping and automated toolchains—establish a common data foundation. This approach streamlines data exchange, reduces errors, and supports early-stage energy simulations, thus promoting design optimization and better collaboration among AECO stakeholders.

(2) To what extent can flexible, tool chain-based approaches close the existing gaps? Standardization alone struggles to address the evolving requirements and complexity of modern projects. By incorporating toolchain-based solutions (like the BIM2BEM-Flow system) with API-driven integrations, default value libraries, and role-based responsibilities, the approach not only automates property management but also adapts dynamically to project-specific needs. This method paves the way for broader interoperability, provided that BEM software vendors enhance IFC support for alphanumeric data.

Open Questions and Future Challenges:

Standardization vs. Flexibility: Creating a standard that is both flexible and scalable remains a challenge. Future work should focus on developing public libraries that can be updated quickly and adapted to both national and international requirements.

Interoperability in Practice: While our approach successfully integrates parameters into BIM workflows, many simulation tools (aside from DALEC and PHPP) still do not support the import of alphanumeric data via IFC. Collaboration with software vendors is needed to optimize this process.

Parameter Management and Redundancy: As property libraries grow, managing redundancies and conflicts becomes increasingly complex. Dividing libraries by simulation tool and establishing clear rules for managing overlaps are promising solutions.

Long-Term Dissemination and Industry Acceptance: The current work is experimental and has not yet been validated by independent companies. Future initiatives should aim to publish these tools and property libraries for public use, support their inclusion in academic curricula, and encourage industry-wide collaboration.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that a combined approach of standardized parameter development and a flexible, toolchain-based management system can significantly enhance the integration of BIM and BEM. By enabling early design optimization, reducing repetitive workflows, and establishing clear roles and responsibilities, the BIM2BEM-Flow approach sets a strong foundation for future innovations. The next steps involve broader industry validation, enhanced interoperability with more simulation tools, and the widespread adoption of public property libraries to drive further improvements in energy-efficient building design.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

The work presented is based on the project results of BIM2IndiLight funded by the Standortagentur Tirol. The program K-Regio is co-financed by the funds of Europäische Fonds für Regionale Entwicklung EFRE, started on November 2018 and completed on April 2022 and BIM2BEM-Flow funded by the Austrian research agency (FFG), 8th announcement Stadt der Zukunft. For the writing of this paper, ChatGPT was used as a tool to support and refine the work. ChatGPT was helpful in discussing the structure and organization of the paper, evaluating whether the research questions were adequately addressed, and improving the clarity and wording of certain sections. Although all of the content was human, ChatGPT provided valuable assistance in reviewing and refining the text and provided a clearer and more structured presentation of ideas. Chapter 7 is particularly noteworthy here. This arose from a discussion with ChatGPT. ChatGPTs contributions have helped to improve the quality of this work, for which I am grateful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASI |

Austrian Standards Institute |

| AECO |

Architecture, Engineering, Construction, Operation |

| BEM |

Building Energy Modeling |

| BEP |

BIM Execution Plan |

| BEPS |

Building Energy Performance Simulation |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| DALEC |

Day- and Artificial Light Energy Calculation |

| ER |

Exchange Requirements |

| EIR |

Exchange Information Requirements |

| gbXML |

Green Building XML |

| HVAC |

Heating, Cooling, Air Conditioning |

| IDM |

Information Delivery Manual |

| IDS |

Information Delivery Specifications |

| IFC |

Industry Foundation Classes |

| LOIN |

Level of Information Need |

| MVD |

Model View Definitions |

| PWM |

Project Workflow Manager |

| RWM |

Revit Workflow Manager |

| VEC |

VisErgyControl |

| YAPS |

Yet Another Property Server |

References

- Varghese, P. Influence and Adoption of BIM within the AEC Industry; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. A Scientometric Review of Global BIM Research: Analysis and Visualization. Autom Constr 2017, 80, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Lill, I.; Witt, E. An Overview of BIM Adoption in the Construction Industry: Benefits and Barriers. Emerald Reach Proceedings Series 2019, 2, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.; Merschbrock, C.; Munkvold, B.E. A Review of Building Information Modelling for Construction in Developing Countries. Procedia Eng 2016, 164, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Koch, C.; Wu, Y. Building Information Modelling Based Building Energy Modelling: A Review. Appl Energy 2019, 238, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, G.; Luo, L.; Shi, Q.; Xie, J.; Meng, X. Mapping the Managerial Areas of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Using Scientometric Analysis. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Santos, J.; Leite, F.; Escórcio, P. Using BIM to Improve Building Energy Efficiency – A Scientometric and Systematic Review. Energy Build 2021, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Bin; Chou, H.Y. Subjective Benefit Evaluation Model for Immature BIM-Enabled Stakeholders. Autom Constr 2019, 106, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doe, R.; Kaur, K.; Selway, M.; Stumptner, M. Ecosystem Interoperability for the Architecture, Engineering, Construction & Operations (Aeco) Sector. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2024, 29, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIM2IndiLight. Available online: https://www.uibk.ac.at/bauphysik/forschung/projects/bim2indilight/index.html.en.

- Werner, M.; Geisler-Moroder, D.; Junghans, B.; Ebert, O.; Feist, W. DALEC–a Novel Web Tool for Integrated Day- and Artificial Light and Energy Calculation. J Build Perform Simul 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 16739-1 Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) Für Den Datenaustausch in Der Bauwirtschaft Und Im Anlagenmanagement - Teil 1: Datenschema (ISO 16739-1:2018); Englische Fassung EN ISO 16739-1:2020 2021.

- Alhammad, M.; Eames, M.; Vinai, R. Enhancing Building Energy Efficiency through Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Building Energy Modeling (BEM) Integration: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsani, G.B.; de Lersundi, K.D.V.; Gutiérrez, A.S.O.; Bandera, C.F. Interoperability between Building Information Modelling (Bim) and Building Energy Model (Bem). Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Elnabawi, M.H. Building Information Modeling-Based Building Energy Modeling: Investigation of Interoperability and Simulation Results. Front Built Environ 2020, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 19650-1:2019 Organization and Digitization of Information about Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, Including Building Information Modelling (BIM) — Information Management Using Building Information Modelling — Part 1: Concepts and Principles. 2019.

- Borrmann, A.; König, M.; Koch, C. Building Information Modeling Technology Foundations and Industry Practice; Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, W.; Kim, J.B.; Clayton, M.J.; Haberl, J.S.; Yan, W. Translating Building Information Modeling to Building Energy Modeling Using Model View Definition. Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, J.; Drogenmuller, R.; Toth, B. Model Interoperability in Building Information Modelling. Softw Syst Model 2012, 11, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, A.; Monfet, D.; Forgues, D. Review of Using Building Information Modeling for Building Energy Modeling during the Design Process. Journal of Building Engineering 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.; Wimmer, R.; Muhic, S.; Maile, T.; O’Donnell, J.; Bazjanac, V.; Frisch, J.; van Treeck, C. Model View Definition for Advanced Building Energy Performance Simulation. In Proceedings of the BauSim Conference, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, S.; Wimmer, R.; O’Donnell, J.; Muhic, S.; Bazjanac, V.; Maile, T.; Frisch, J.; van Treeck, C. MVD Based Information Exchange between BIM and Building Energy Performance Simulation. Autom Constr 2018, 90, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asmi, E.; Robert, S.; Haas, B.; Zreik, K. A Standardized Approach to BIM and Energy Simulation Connection. International Journal of Design Sciences and Technology 2015, 21, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- buildingSMART IDS - Information Delivery Specification. Available online: https://technical.buildingsmart.org/projects/information-delivery-specification-ids/.

- Gao, H.; Koch, C.; Wu, Y. Building Information Modelling Based Building Energy Modelling: A Review. Appl Energy 2019, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arayici, Y.; Fernando, T.; Munoz, V.; Bassanino, M. Interoperability Specification Development for Integrated BIM Use in Performance Based Design. Autom Constr 2018, 85, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazjanac, V. IFC BIM-Based Methodology for Semi-Automated Building Energy Performance Simulation. CIB-W78 25th International Conference on Information Technology in Construction; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic, D.; Patanakul, P. Standardized Project Management May Increase Development Projects Success. International Journal of Project Management 2005, 23, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK BIM Framework Information Management According to BS EN ISO 19650 - Guidance Part 1: Concepts. UK BIM Alliance 2019, 42.

- 17412-1, S. C: ISO 17412-1:2020 Building Information Modelling - Level of Information Need - Part 1, 1741.

- Osadcha, I.; Jurelionis, A.; Fokaides, P. Requirements for Geometrical Data in Digital Twin for Building Energy Modelling and Interoperability. 2024 9th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies, SpliTech 2024, 2024; 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsbergen, V. Van; Moser, S.; Plörer, D.; Weitlaner, R.; Hauer, M.; Pfluger, R. An Experimental Investigation of the IndiLight-Module - a Multi-Objective Occupant-Centric Day- and Artificial Lighting Control Strategy.

- Fröch, G.; Gächter, W.; Tautschnig, A.; Al, E. Merkmalserver Im Open-BIM-Prozess. Bautechnik 2019, 96, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Moser, F.; Stumpf, J.P.; Pfluger, R. REVIT2DALEC : A BIM2BEM COMBINED THERMAL AND DAY- AND ARTIFICIAL LIGHT ENERGY CALCULATION WITH DALEC USING THE MVD. BauSIM 2020 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hauer, M.; Pfluger, R.; Plörer, D. Integrale Tages- Und Kunstlicht- Steuerung Für Hohen Visuellen Und Melanopischen Komfort Bei Hoher Primärenergieeffizienz. 2019.

- ISO/TC 163/SC 2 EN 13790:2008 Energy Performance of Buildings - Calculation of Energy Use for Space Heating and Cooling. 2008.

- DIN EN 17037:2019-03 Tageslicht in Gebäuden; Deutsche Fassung EN 17037:2018. 2019.

- DIN EN 13779:2007-09 Lüftung von Nichtwohngebäuden - Allgemeine Grundlagen Und Anforderungen Für Lüftungs- Und Klimaanlagen Und Raumkühlsysteme. 2007.

- ÖNORM EN 16798-1 - Energetische Bewertung von Gebäuden - Teil 1: Eingangsparameter Für Das Innenraumklima Zur Auslegung Und Bewertung Der Energieeffizienz von Gebäuden Bezüglich Raumluftqualität, Temperatur, Licht Und Akustik - Module M1-6. 2019.

- DIN EN 14501:2021-09 Abschlüsse - Thermischer Und Visueller Komfort - Leistungsanforderungen Und Klassifizierung. 2021.

- DIN EN 410:2011-04 Glas Im Bauwesen - Bestimmung Der Lichttechnischen Und Strahlungsphysikalischen Kenngrößen von Verglasungen. 2011.

- DIN EN 60034-1 VDE 0530-1:2011-02 Drehende Elektrische Maschinen Teil 1: Bemessung Und Betriebsverhalten. 2011.

- DIN EN 60034-5:2007-09 VDE 0530-5:2007-09 Drehende Elektrische Maschinen - Teil 5: Schutzarten Aufgrund Der Gesamtkonstruktion von Drehenden Elektrischen Maschinen (IP-Code) - Einteilung (IEC 60034-5:2000 + Corrigendum 2001 + A1:2006). 2007.

- CEN DIN-Normenausschuss Lichttechnik (FNL) – Allgemeine Begriffe Und Gütemerkmale – Definitionen. 2022.

- DIN CEN/TS 17623:2021-08 BIM-Merkmale Für Die Beleuchtung - Leuchten Und Sensoren. 2021.

- Kamel, E.; Memari, A.M. Review of BIM’s Application in Energy Simulation: Tools, Issues, and Solutions. Autom Constr 2019, 97, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, D.E.B.I.M.; Brasileiro, P.; Edifica, D.E.E.D.E.; Revis, U.M.A. BIM APPLICATION IN THE BRAZILIAN BUILDING LABELING PROGRAM : A REVIEW APLICAÇÃO DE BIM NO PROGRAMA BRASILEIRO DE ETIQUETAGEM DE EDIFICAÇÕES : UMA The Building Sector Consumes 35 % of the World ’ s Energy and Is Responsible for Emitting. 2024, 1–26.

- DFS Digital Findet Stadt. Available online: https://www.digitalfindetstadt.at/.

- Bazjanac, V. Model Based Cost and Energy Performance Estimation during Schematic Design. CIB W78, Proc. 22nd conf. information technology in construction.

- Dong, B.; Lam, K.P.; Huang, Y.C.; Dobbs, G.M. A Comparative Study of the IFC and GbXML Informational Infrastructures for Data Exchange in Computational Design Support Environments. IBPSA 2007 - International Building Performance Simulation Association 2007, 1537. [Google Scholar]

- BIMQ BIMQ. Available online: https://www.bimq.de/en/.

Figure 1.

BIM2BEM-Flow workflow toolchain.

Figure 1.

BIM2BEM-Flow workflow toolchain.

Figure 2.

Building life cycle with energy optimization loops during the design stage.

Figure 2.

Building life cycle with energy optimization loops during the design stage.

Figure 3.

Scheme of BIM2BEM interoperability approaches (The blue and pink boxes indicate the approaches in which the work from the two projects is categorized).

Figure 3.

Scheme of BIM2BEM interoperability approaches (The blue and pink boxes indicate the approaches in which the work from the two projects is categorized).

Figure 4.

Conceptual relationships between International Norms (ISO 19650-1, ISO 17412-1, ISO 29481-1) [

30] (slightly changed by adding categories (grey boxes)).

Figure 4.

Conceptual relationships between International Norms (ISO 19650-1, ISO 17412-1, ISO 29481-1) [

30] (slightly changed by adding categories (grey boxes)).

Figure 5.

Simplifying and standardization the process of defining the Asset Information Model.

Figure 5.

Simplifying and standardization the process of defining the Asset Information Model.

Figure 6.

Property definition process - method .

Figure 6.

Property definition process - method .

Figure 7.

Use of property server BIM2BEM-Flow.

Figure 7.

Use of property server BIM2BEM-Flow.

Figure 8.

Database structure (YAPS = BIM2BEM-Flow project database name).

Figure 8.

Database structure (YAPS = BIM2BEM-Flow project database name).

Figure 9.

Data structure and inheritance.

Figure 9.

Data structure and inheritance.

Figure 10.

Building element classes.

Figure 10.

Building element classes.

Figure 11.

Parameter groups (IfcPropertySets).

Figure 11.

Parameter groups (IfcPropertySets).

Figure 12.

Property Set Mapping.

Figure 12.

Property Set Mapping.

Figure 13.

Parameter Mapping.

Figure 13.

Parameter Mapping.

Figure 14.

Parameter library with connected default values library.

Figure 14.

Parameter library with connected default values library.

Figure 15.

Database and mapping structure.

Figure 15.

Database and mapping structure.

Figure 16.

Revit export user defined property sets.

Figure 16.

Revit export user defined property sets.

Figure 17.

Exemplary List of result Parameters.

Figure 17.

Exemplary List of result Parameters.

Table 1.

Approaches for model enrichment [

23].

Table 1.

Approaches for model enrichment [

23].

| |

Approaches to interoperability enhancement |

| |

Model Extension |

Model semantic enrichment |

| Description |

Model evolution

Adding new concepts to the standard |

Model Data extension

Use of existing interfaces in the standard model |

bSDD

Use of bSDD library as a complement of IFC |

Ontology

Conversion and enrichment of IFC model |

| Pros |

+Wider implementation

+Sustainable Solution

+More Impact |

+Easy and quick to implement

+Widely used

+No change to the standard |

+Offers a dictionary (multi-concept, multi-lingual)

+Standard compliance |

+Several conversion tools exist

+Better expressiveness |

| Cons |

-Implementation time

-Complex models

-No semantic |

-Local extension (CAD tool import/ export)

-No semantic |

-Only enrichment (no extension) |

-Conversion time to RDF/ owl

-Tool maintaining |

Table 2.

BIM2BEM: Problems and Solutions.

Table 2.

BIM2BEM: Problems and Solutions.

| Problem |

Solution |

| Implementation of energy model properties to BIM tools is time and resource consuming |

|

| Post-processing the BIM output for inputs of the BEM tools are time and resource consuming and only for professionals |

|

| BIM-based BEM is only useful if design variation can be easily and quickly compared and evaluated during the first design stage |

|

| Tools are not compatible with architects working methods and needs, especially in the early design phase |

|

| Interoperability of exchange information |

|

Table 4.

Property lists and their overlaps.

Table 4.

Property lists and their overlaps.

| |

In Total |

Property package’s overlaps |

| |

|

PP1-DALEC |

PP2-Artificial Light |

PP3-Daylight |

PP4-Sensor and control properties |

| PP1-DALEC |

71 |

|

4 |

6 |

10 |

| PP2-Artificial Light |

114 |

4 |

|

5 |

1 |

| PP3-Daylight |

166 |

6 |

5 |

|

0 |

| PP4-Sensor and controlling properties |

103 |

10 |

1 |

0 |

|

| In Total |

454 |

|

|

|

428 |

Table 5.

Source analysis for each task group’s property package.

Table 5.

Source analysis for each task group’s property package.

| |

In total |

IFC-properties |

Documentation/Source |

| |

|

|

standards and guidelines |

Further documentation – BIM2IndiLight specific |

| PP1-DALEC |

71 |

23 |

32% |

26 |

37% |

45 |

| PP2-Artificial Light |

114 |

26 |

23% |

114 |

100% |

- |

| PP3-Daylight |

166 |

17 |

10% |

76 |

46% |

90 |

| PP4-Sensor and controlling properties |

103 |

2 |

2% |

74 |

72% |

17 |

Table 6.

Distinction between alphanumerical and geometrical information.

Table 6.

Distinction between alphanumerical and geometrical information.

| |

Alphanumerical information |

Geometrical information |

| PP1-DALEC |

91.5% |

8.5% |

| PP2-Artificial Light |

88.6% |

11.4% |

| PP3-Daylight |

88.6% |

11.4% |

| PP4-Sensor and controlling properties |

98.1% |

1.9% |

| Total (weighted average) |

91.2% |

8.8% |

Table 7.

Revision of BIM2IndiLight parameters against the IFC 4.3 standard.

Table 7.

Revision of BIM2IndiLight parameters against the IFC 4.3 standard.

| All Parameters |

385 |

|

| 0 = No assignment |

153 |

40% |

| 1 = Clear assignment |

168 |

44% |

| 2 = Assignment complex |

42 |

11% |

| 3 = Theoretically available but not quite correct |

22 |

6% |

Table 8.

Property Library and Default Sets.

Table 8.

Property Library and Default Sets.

| Library |

Parameter |

BIM (Revit) |

IES VE |

DALEC |

PHPP |

|

DGNB Gold |

PH Standard |

| Project_01 |

Thermal Transmittance Coefficient |

Thermal Transmittance Coefficient |

U-Value |

U-Wert |

Wärmedurchgangs-coefficient |

|

0.8 |

0.6 |

| Visible Light Transmittance |

Visible Light Transmittance |

Light Trans |

VLT |

Transmission Licht |

|

0.65 |

0.7 |

| Shading Reflectance 15° |

Shading Reflectance 15° |

SH_R_15 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

Table 9.

Workflow Example.

Table 9.

Workflow Example.

| Workflow |

Responsible BIM |

BIM Tool |

Responsible SIM |

SIM Tool |

Use-Case |

Phase |

Library |

Default-Set |

| Daylight Simulation |

Josef M. |

Revit |

Rainer P. |

DALEC |

Comparison of Variants |

Early Design |

Project_01 |

PH Standard |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).