Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Circularity, Life Cycle Assessment and End of Life

2.2. BIM, Not a Model but Heterogenous Data

2.3. Challenges in BIM-LCA Integration

2.4. BIM for Circular Design and Material Reuse

2.5. Future Directions for Circularity in Construction

2.6. Towards a Comprehensive Circular Strategy in the Construction Sector

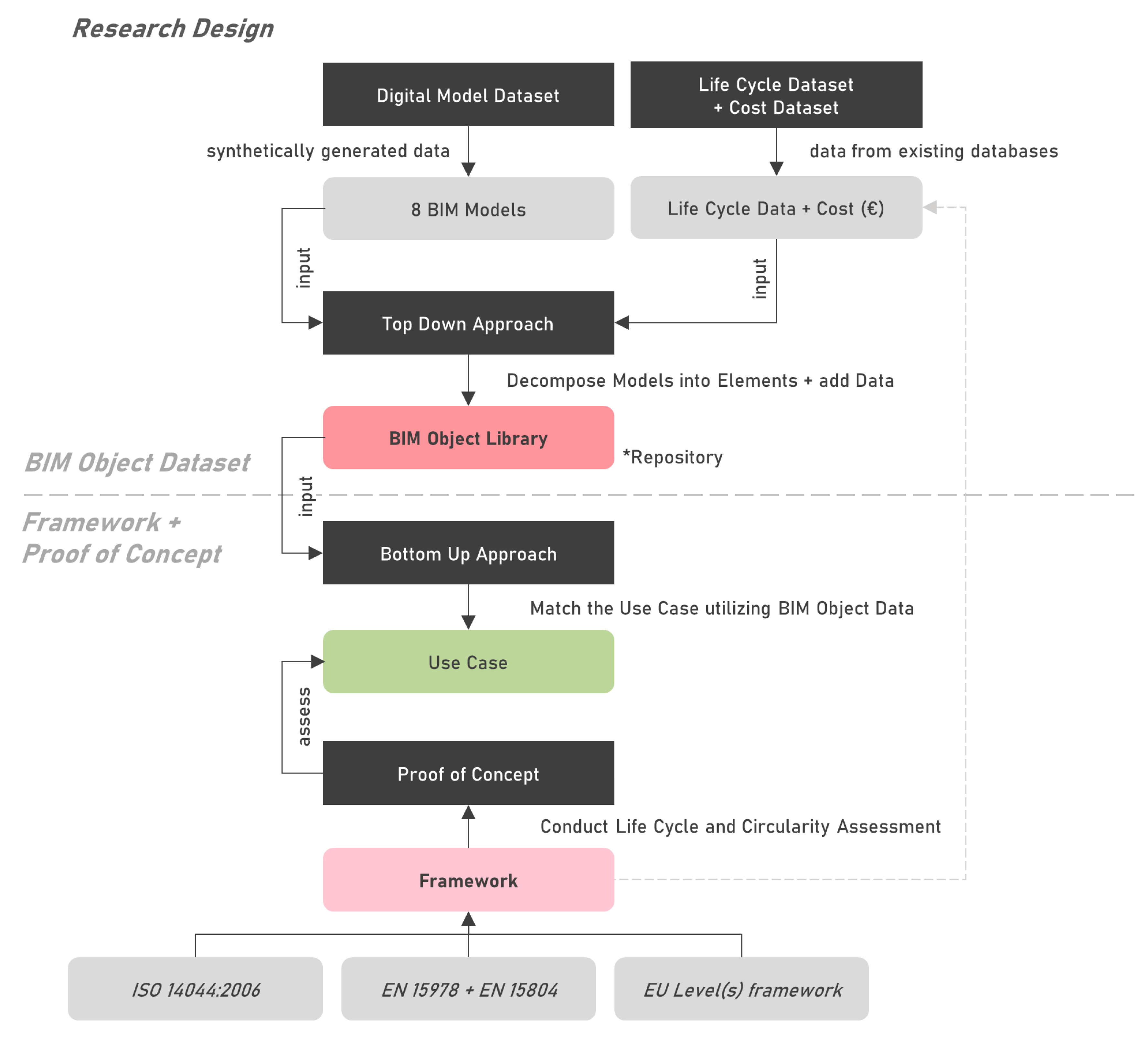

3. Research Design

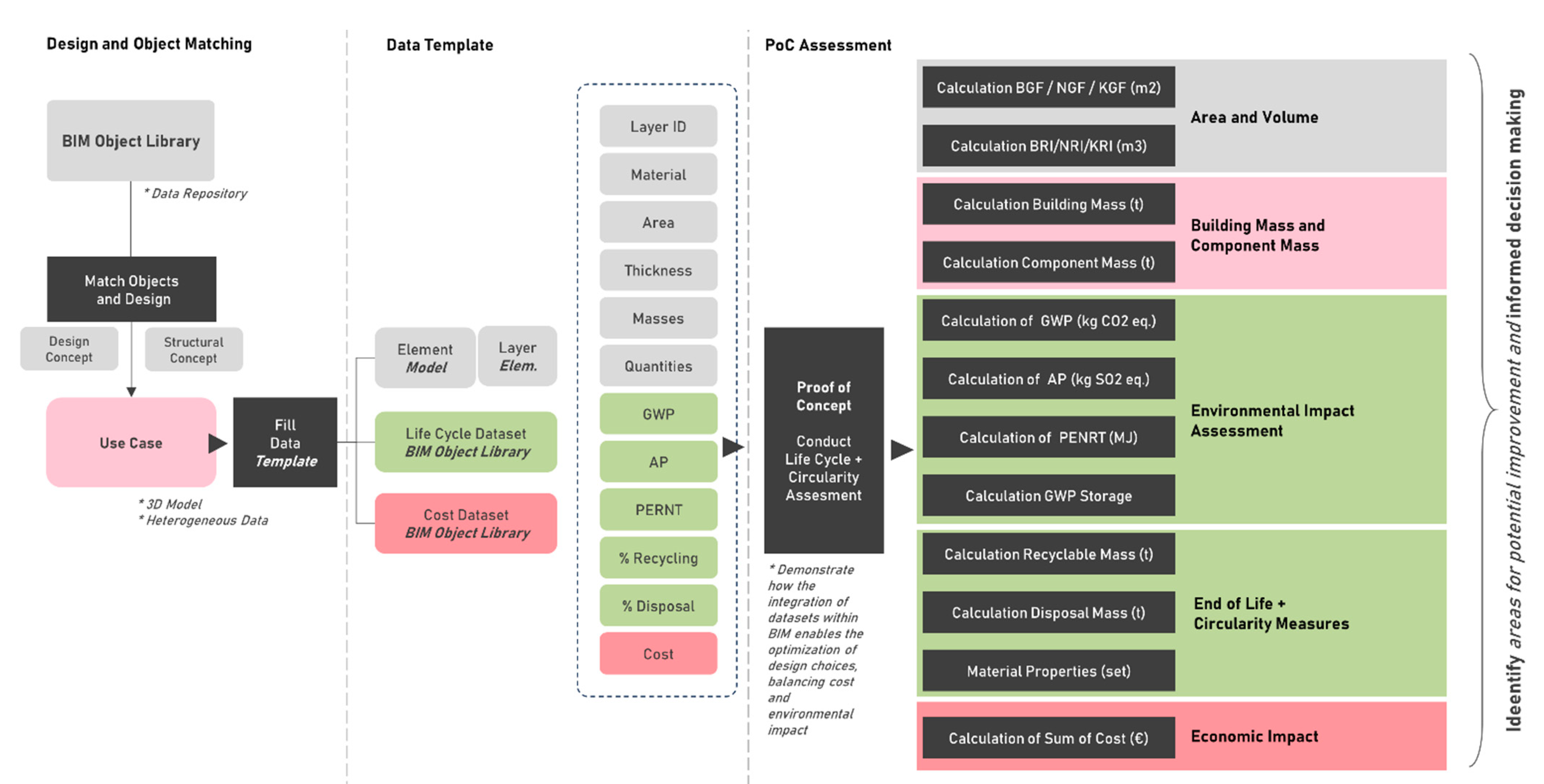

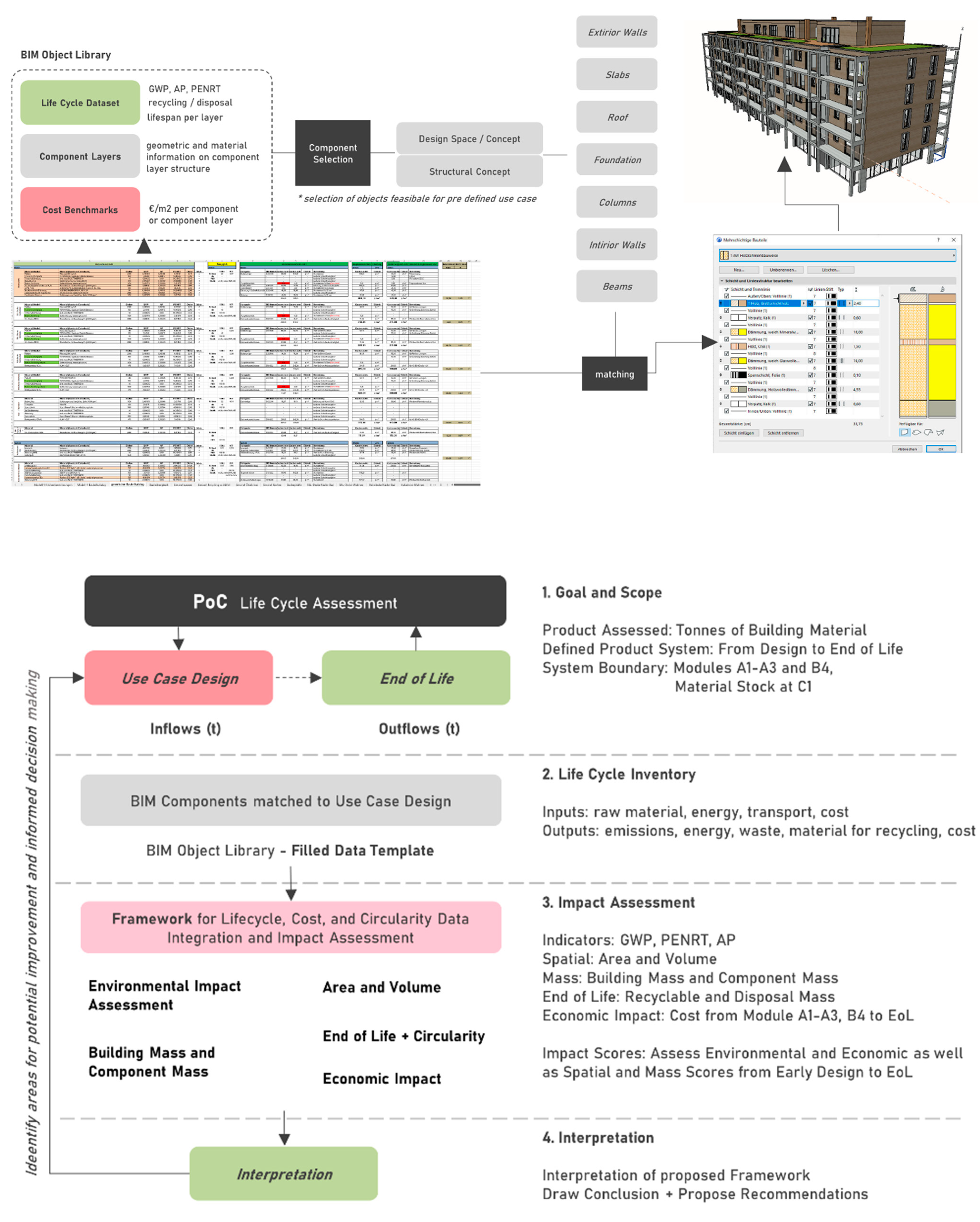

4. Framework

4.1. Data Template

4.2. Key Metrics and Assessment

| Category | Calculation/Metric | Units | Relevant Standard/Framework | Reference Details |

| Area and Volume | Building Gross Floor Area (GFA) | m² | EN 15978 | Basis for functional units in building LCA calculations. |

| Net Gross Floor Area (NFA) | m² | EN 15978 | Supports defining the building scope in environmental assessments. | |

| Construction Gross Floor Area (CFA) | m² | EN 15978 | Used in establishing the functional and declared units for assessment. | |

| Gross Room Volume (GRV) | m³ | EN 15978 | Contributes to scope definition in whole-building environmental assessments. | |

| Net Room Volume (NRV) | m³ | EN 15978 | Supports calculations, aligning with EN 15978 system boundary. | |

| Construction Room Volume (CRV) | m³ | EN 15978 | Part of volume-based functional unit definitions within whole-building LCA. | |

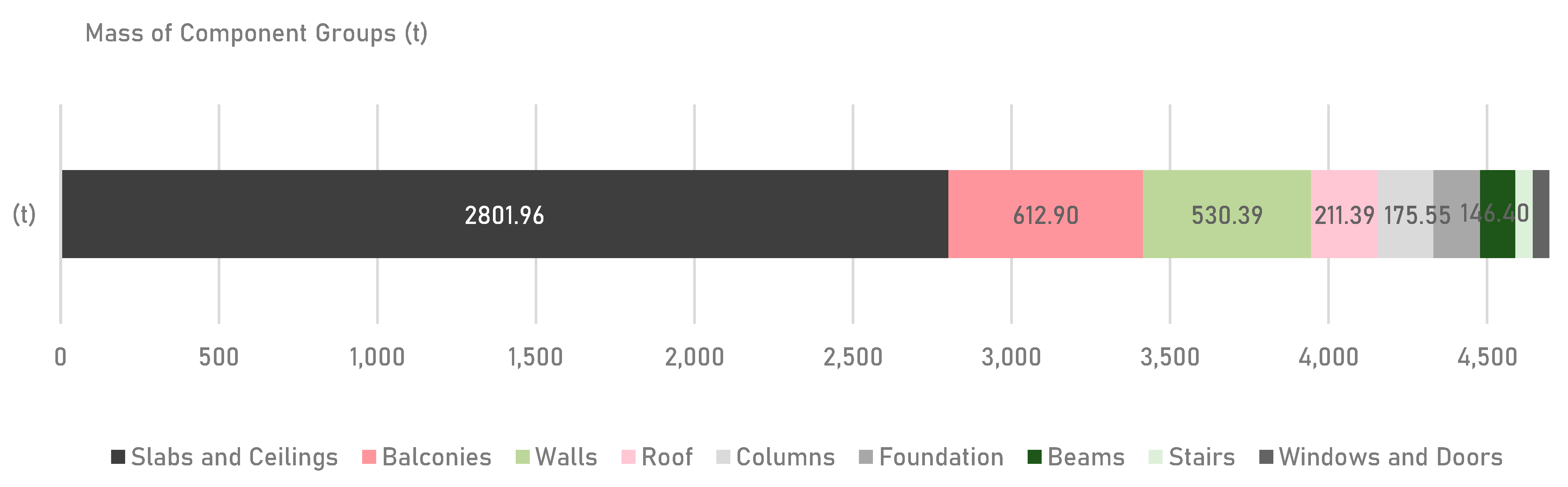

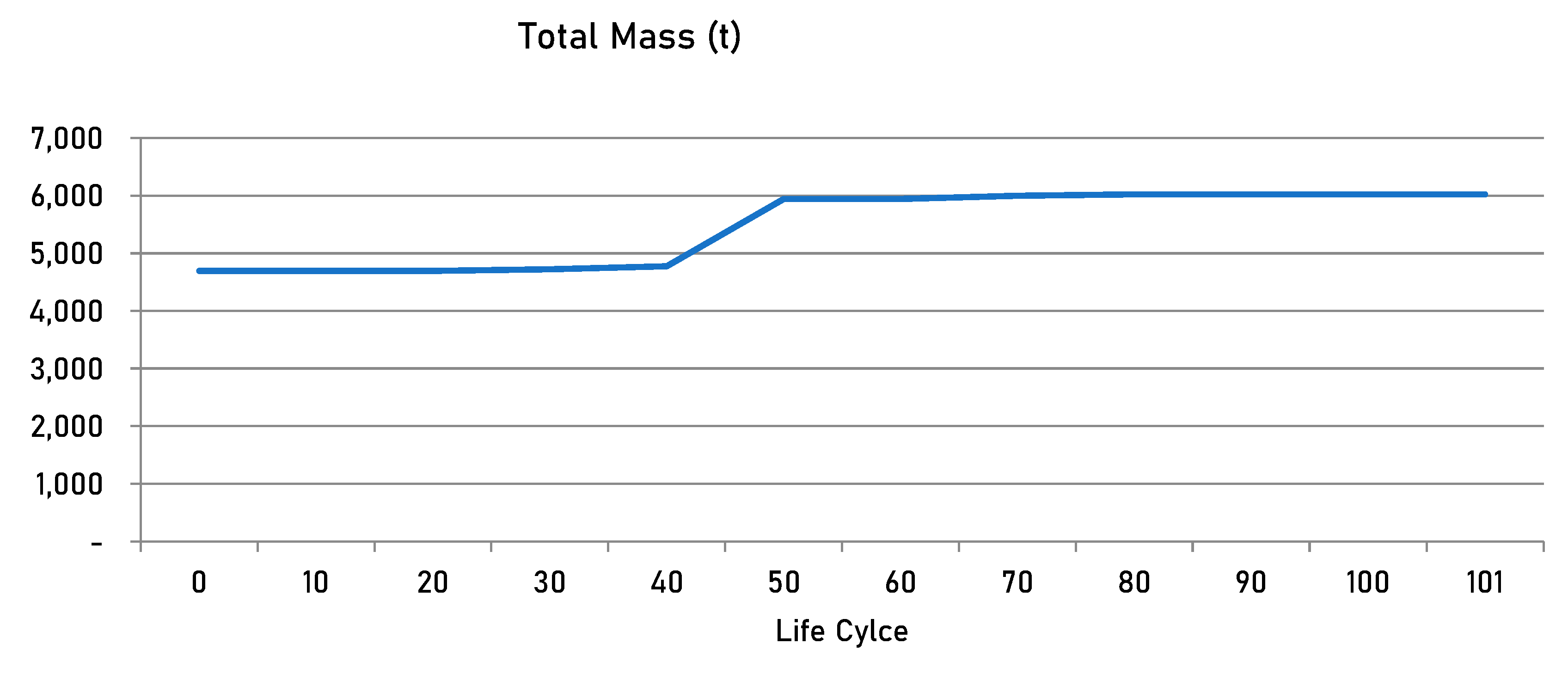

| Building Mass and Component Mass | Total Building Mass | tons / kg | EN 15804, EN 15978 | Mass data used in building-level and component-level LCA stages. |

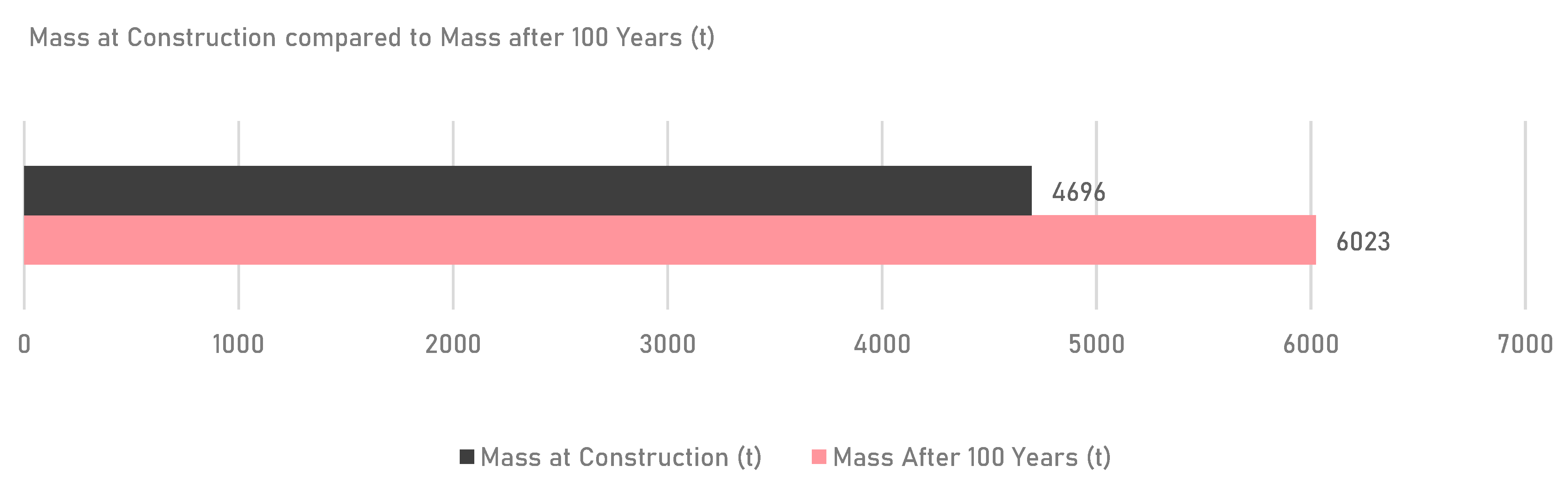

| Building Mass after 100 Years | tons / kg | EN 15978 | Relevant for assessing impacts over the life cycle and future material needs. | |

| Individual Component Masses | tons / kg | EN 15804 | Supports environmental assessments of specific materials and their life cycle impacts. | |

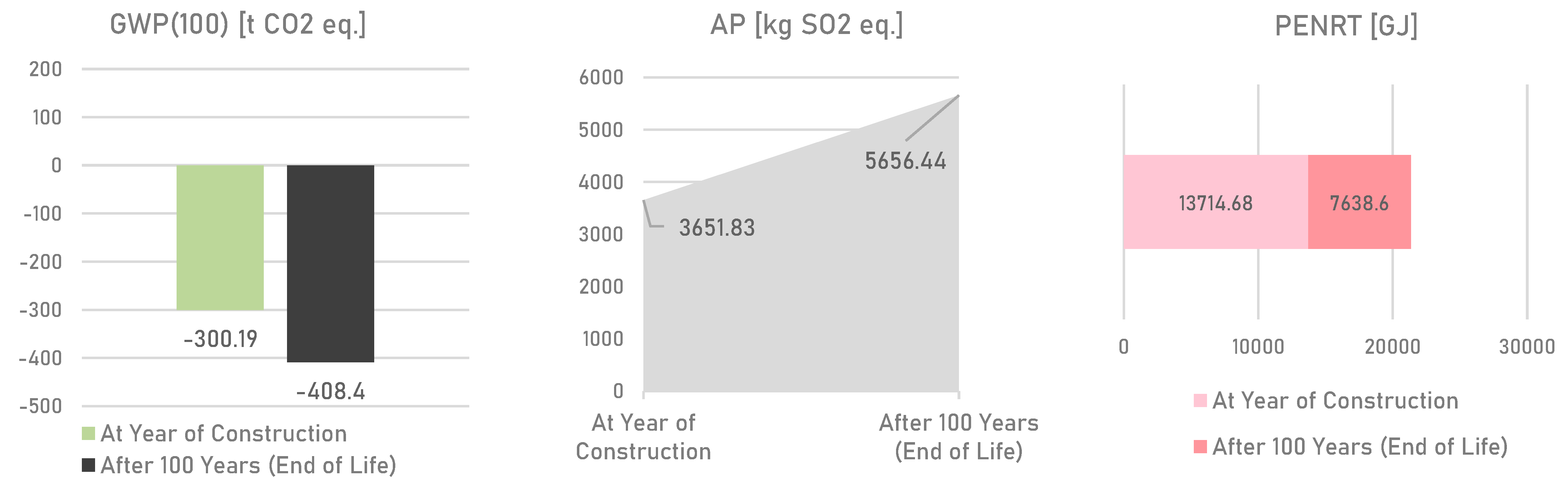

| Environmental Impact Assessment | GWP (Global Warming Potential) | kg CO₂ equivalent | ISO 14044, EN 15804, EN 15978, EU Level(s) | Core LCA metric for assessing climate impact across product and building levels. |

| AP (Acidification Potential) | kg SO₂ equivalent | ISO 14044, EN 15804, EN 15978 | Used in impact assessments to quantify acidification in product and building LCA. | |

| PENRT (Primary Energy Non-Renewable Total) | MJ | ISO 14044, EN 15804, EN 15978 | Reflects non-renewable energy use, integral in environmental impact analysis. | |

| GWP Storage | kg CO₂ equivalent | EN 15804, EU Level(s) | Assesses CO₂ sequestration potential within materials, contributing to GWP balance. | |

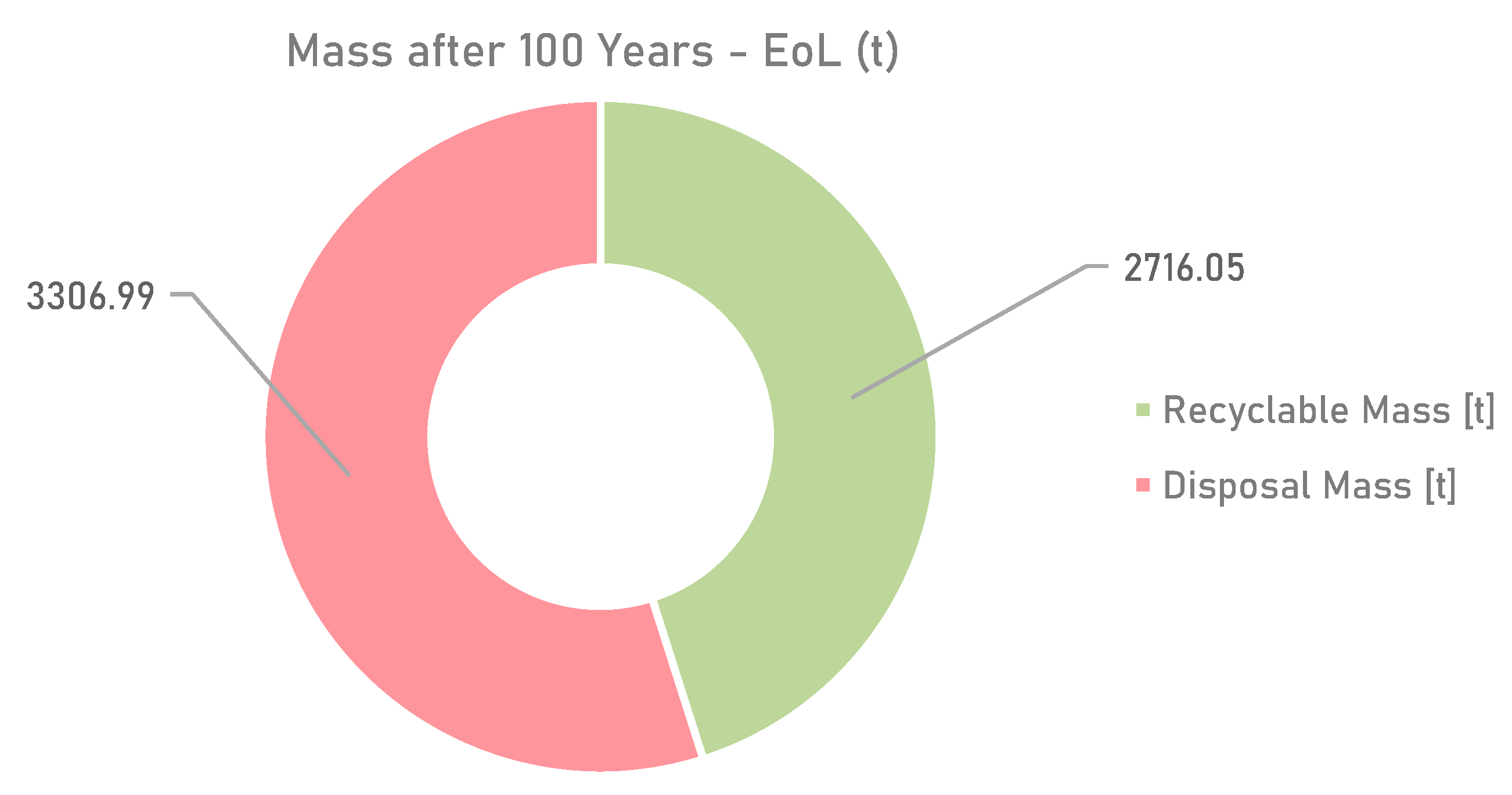

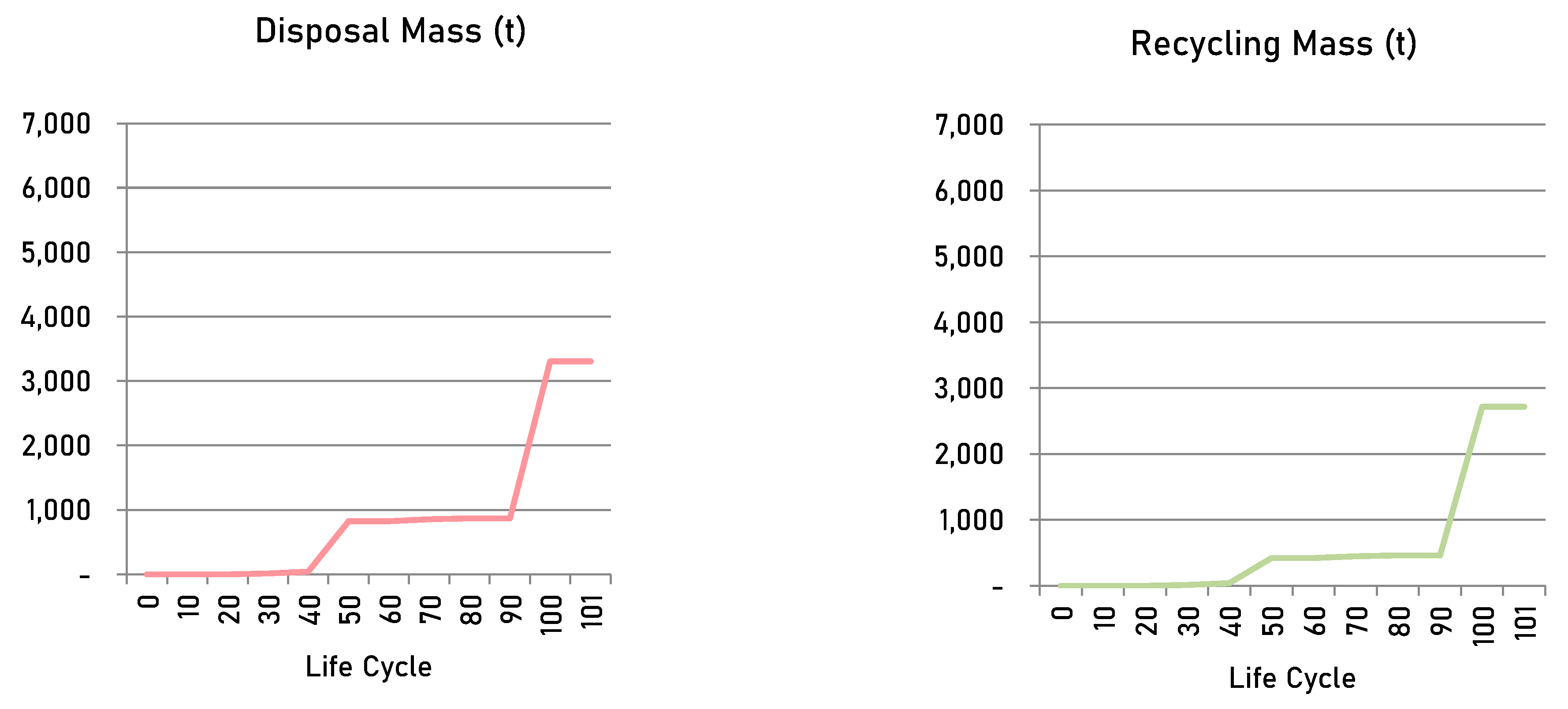

| EoL and Circularity Measures | Recyclable Mass | tons / kg | EN 15804, EN 15978, EU Level(s) | Critical for EoL analysis, assessing recyclability within LCA. |

| Disposal Mass | tons / kg | EN 15804, EN 15978 | Used to evaluate end-of-life disposal impacts and circularity metrics. | |

| Material Properties | descriptive | EN 15804, EU Level(s) | Describes attributes influencing circularity, EoL recovery, and reuse. | |

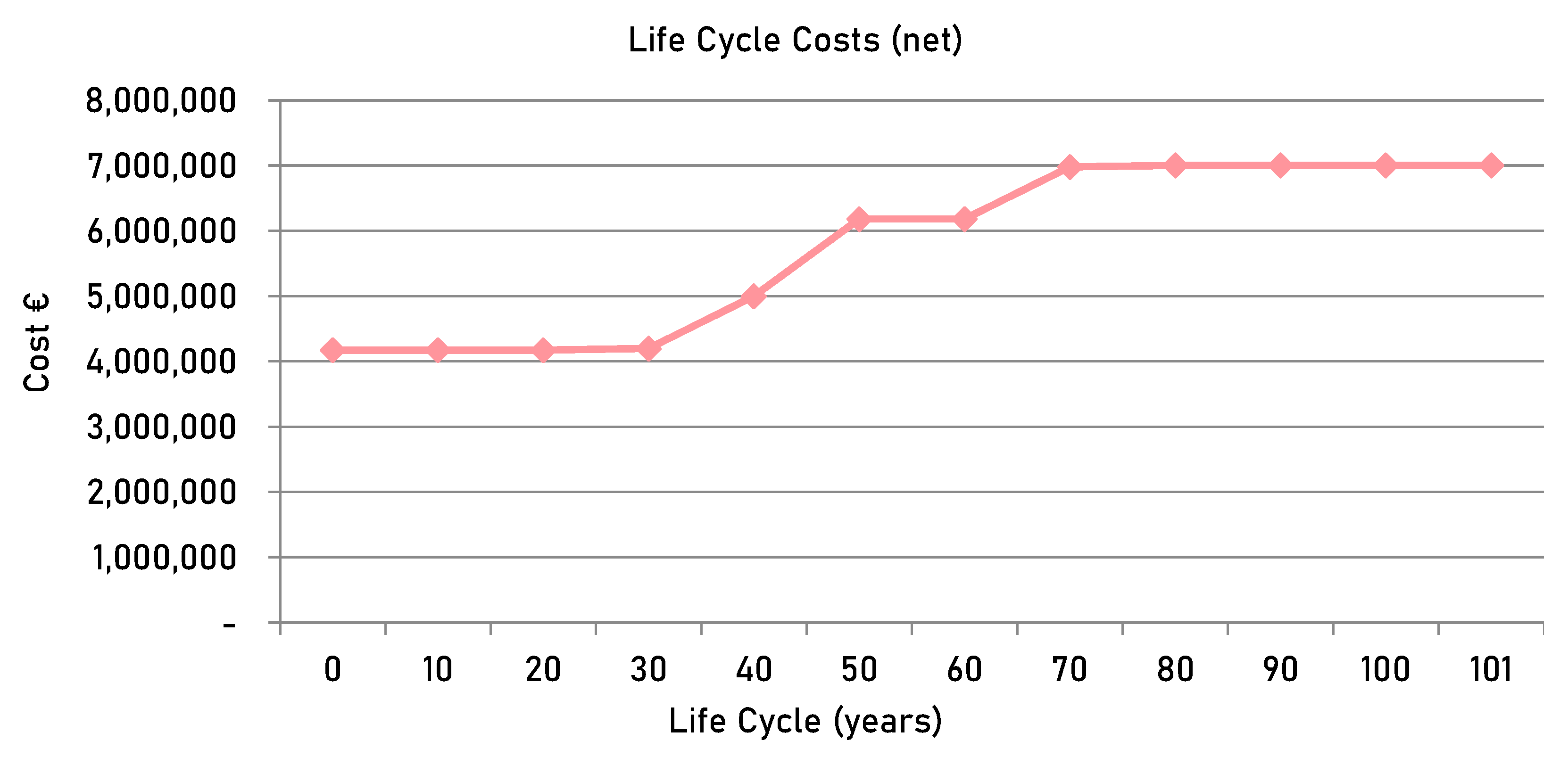

| Economic and Regulatory Impact | Cost | € | EN 15978, EU Level(s) | Supports life cycle cost (LCC) assessments and economic evaluations in LCA. |

5. Proof of Concept

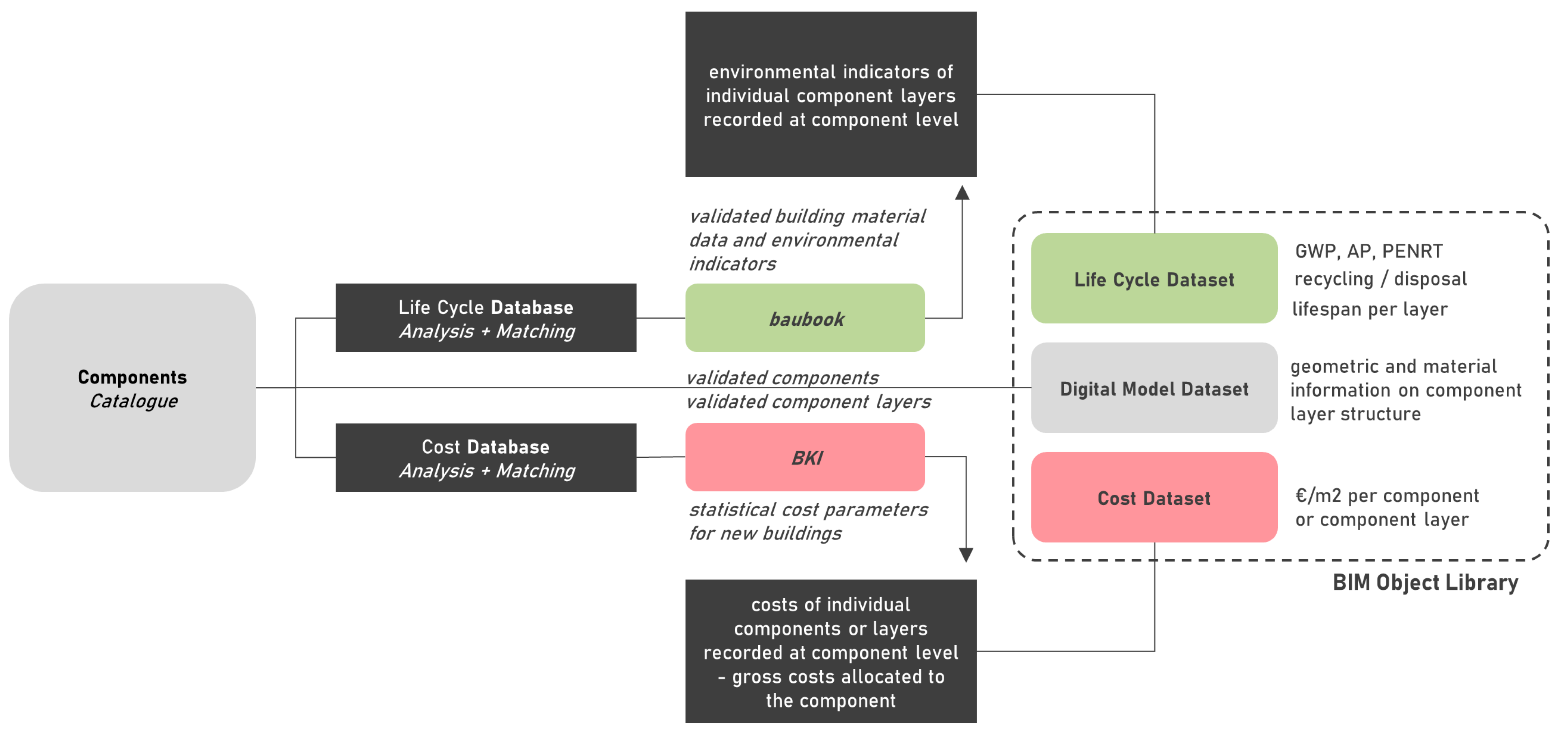

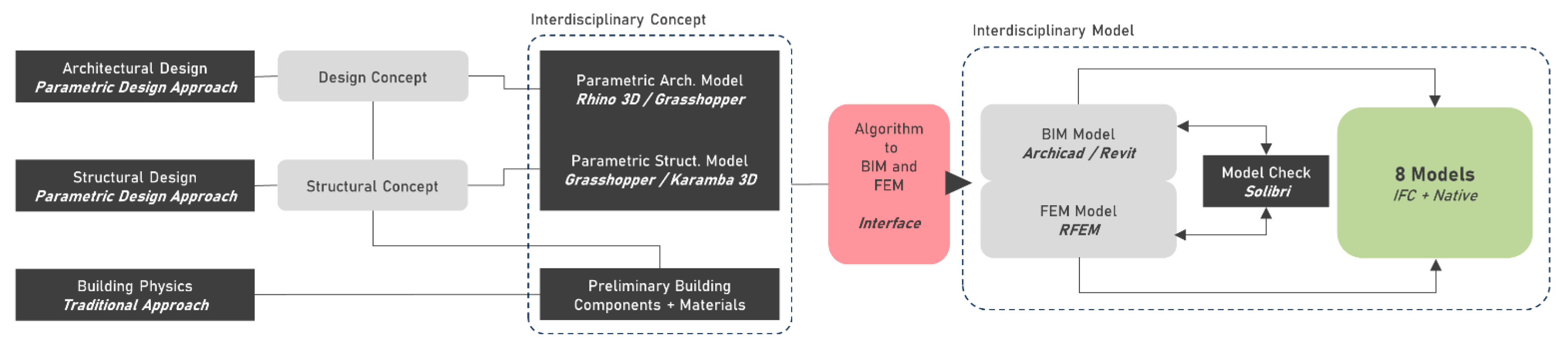

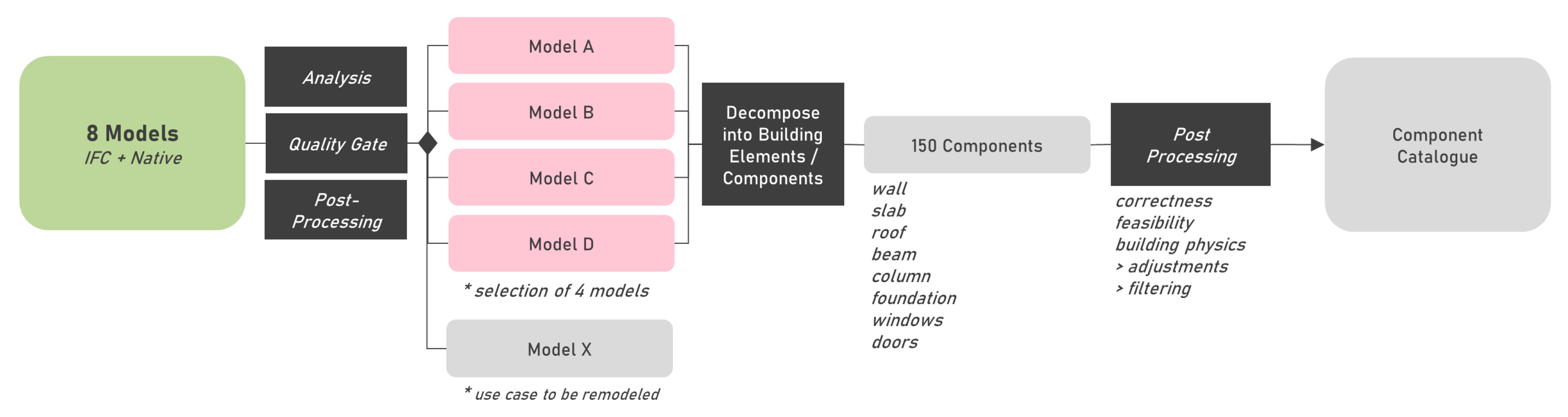

5.1. Digital Model Dataset (Component Catalogue)

5.2. Lifecycle Dataset

5.3. Cost Dataset

5.4. Proof of Concept - Life Cycle Assessment

6. Results

6.1. Area and Volume

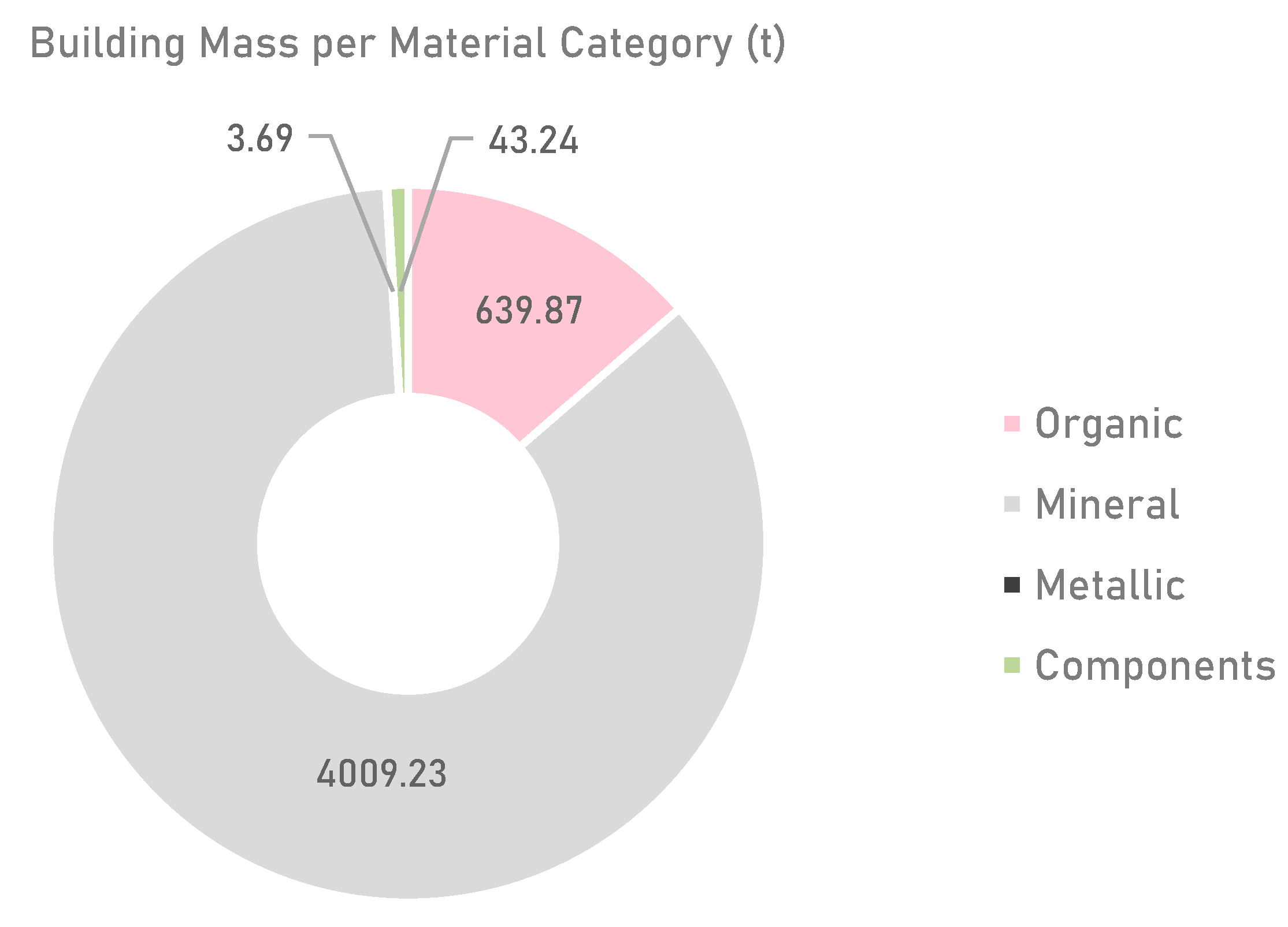

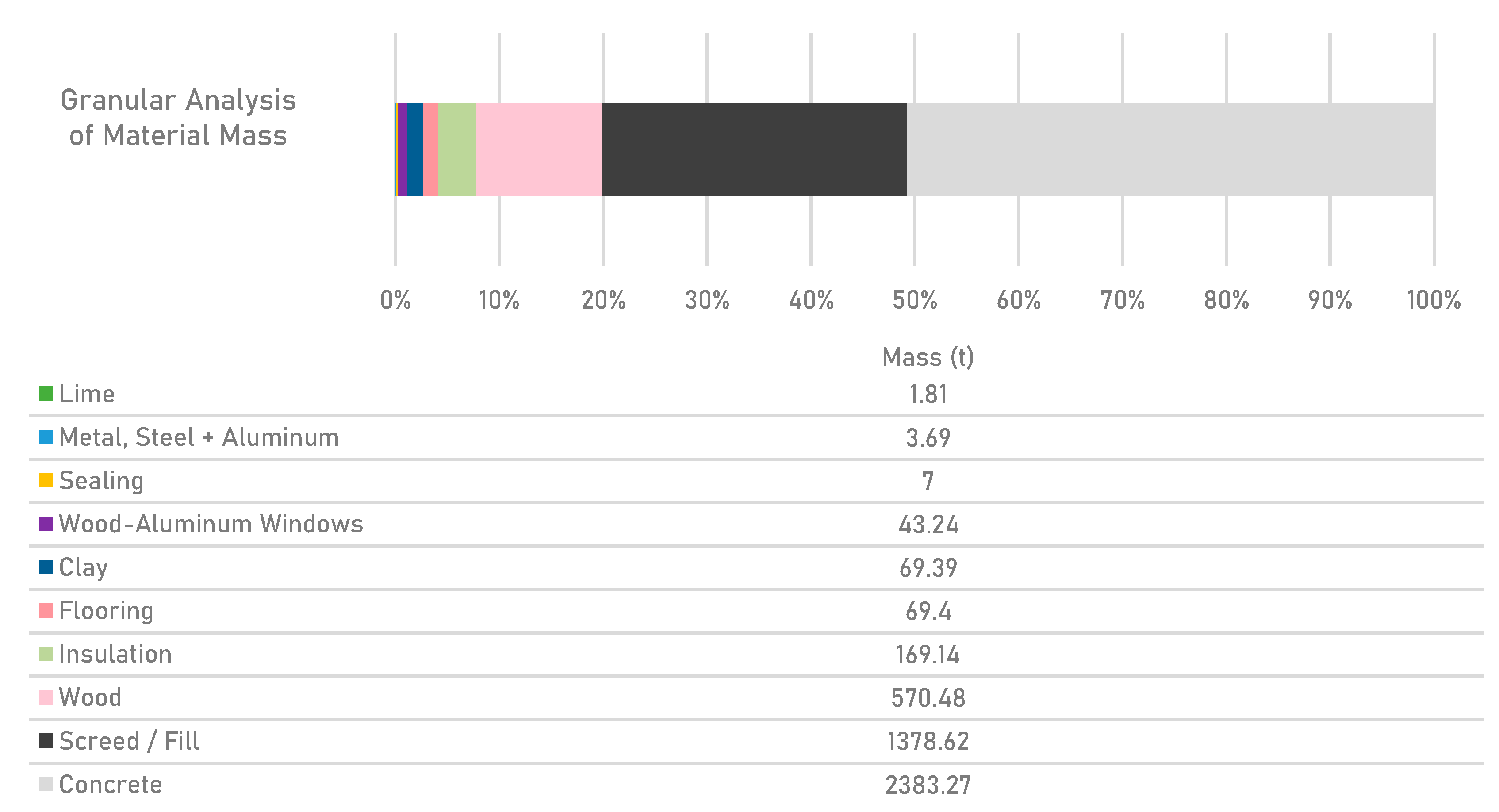

6.2. Building Mass and Component Mass

6.3. Environmental Impact Assessment

6.4. End of Life and Circularity Measures

6.5. Economic Impact

7. Discussion

7.1. Addressing the Research Questions

7.2. Insights from the PoC Implementation

7.3. Quantitative Analyses and Potential Areas for Improvement

7.4. Limitations and Challenges

8. Conclusions and Future Research

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Acknowledgments

References

- bSDD Search. https://search.bsdd.buildingsmart.org/?SearchText=object&ShowPreview=true (accessed 31 October 2024).

- NBS BIM Object Standard. https://source.thenbs.com/bimlibrary/nbs-bim-object-standard (accessed 31 October 2024).

- Guignone, G.; Calmon, J.L.; Vieira, D.; Bravo, A. BIM and LCA integration methodologies: A critical analysis and proposed guidelines. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106780. [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, S.F.; Nani, G.; Taiwo, R.; Antwi-Afari, P.; Zayed, T.; Sojobi, A.O. Modelling the relationship between circular economy barriers and drivers for sustainable construction industry. Build. Environ. 2024, 254. [CrossRef]

- ÖNORM EN ISO 14044:2021 03 01. https://www.austrian-standards.at/de/shop/onorm-en-iso-14044-2021-03-01~p2568309 (accessed 31 October 2024).

- ÖNORM EN 15804:2022 02 15. https://www.austrian-standards.at/de/shop/onorm-en-15804-2022-02-15~p2614831 (accessed 31 October 2024).

- ÖNORM EN 15978:2012 10 01. https://www.austrian-standards.at/de/shop/onorm-en-15978-2012-10-01~p1963407 (accessed 31 October 2024).

- Level(s) - European Commission. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/levels_en (accessed 31 October 2024).

- Norouzi, M.; Chàfer, M.; Cabeza, L.F.; Jiménez, L.; Boer, D. Circular economy in the building and construction sector: A scientific evolution analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Allen, S.; Coley, D. Life cycle assessment in the building design process – A systematic literature review. Build Environ 2020, 185, 107274. [CrossRef]

- Häfliger, I.-F.; John, V.; Passer, A.; Lasvaux, S.; Hoxha, E.; Saade, M.R.M.; Habert, G. Buildings environmental impacts’ sensitivity related to LCA modelling choices of construction materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 805–816. [CrossRef]

- Buyle, M.; Braet, J.; Audenaert, A. Life cycle assessment in the construction sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, S. Assessment methods and digital tools to support circular building strategies. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1402. [CrossRef]

- Austrian Standards Jahresbericht 2021. https://cdn.austrian-standards.at/asset/reb_dokumente/Ueber-uns/Ueber-AS/ASI/Austrian_Standards_International_T%C3%A4tigkeitsbericht_2021.pdf (accessed 20 December 2024).

- ÖNORM ISO 14025:2006 09 01. https://www.austrian-standards.at/de/shop/onorm-iso-14025-2006-09-01~p1515466 (accessed 31 October 2024).

- Charef, R.; Lu, W. Factor dynamics to facilitate circular economy adoption in construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319. [CrossRef]

- Akbarieh, A.; Jayasinghe, L.B.; Waldmann, D.; Teferle, F.N. BIM-Based End-of-Lifecycle Decision Making and Digital Deconstruction: Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2670. [CrossRef]

- Sacks R, Eastman C, Lee G, et al. BIM Handbook. BIM Handbook. Epub ahead of print 14 August 2018. [CrossRef]

- Eastman CM., Teicholz PM., Sacks Rafael, et al. BIM handbook: a guide to building information modeling for owners, managers, designers, engineers and contractors.

- Azhar S. Building Information Modeling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering 2011; 11: 241–252. [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, T.; Glaumann, M.; Scarpellini, S.; Zabalza, I.; Aranda, A.; Llera, E.; Díaz, S. Life cycle assessment in buildings: The ENSLIC simplified method and guidelines. Energy 2010, 36, 1900–1907. [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, B.; Llatas, C.; García-Martínez, A. Critical review of bim-based LCA method to buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 136, 110–120. [CrossRef]

- Sajid, Z.W.; Khan, S.A.; Hussain, F.; Ullah, F.; Khushnood, R.A.; Soliman, N. Assessing economic and environmental performance of infill materials through BIM: a life cycle approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. Epub ahead of print 4 July 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guo, C.; Chen, L.; Qiu, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q. Using BIM and LCA to Calculate the Life Cycle Carbon Emissions of Inpatient Building: A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5341. [CrossRef]

- Al Mahmud, J.; Arefin, S.; Ahmmed, I. Uncovering the research tapestry: bibliometric insights into BIM and LCA – exploring trends, collaborations and future directions. Constr. Innov. Epub ahead of print 2 May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Guo, Z.-Z.; Zhou, S.-X.; Wei, Y.-Q.; She, A.-M.; Dong, J.-L. Research on carbon emissions during the construction process of prefabricated buildings based on BIM and LCA. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Namaki, P.; Vegesna, B.S.; Bigdellou, S.; Chen, R.; Chen, Q. An Integrated Building Information Modeling and Life-Cycle Assessment Approach to Facilitate Design Decisions on Sustainable Building Projects in Canada. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4718. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Costa, A.A.; Silvestre, J.D.; Pyl, L. Integration of LCA and LCC analysis within a BIM-based environment. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 127–149. [CrossRef]

- Gantner J, Tom Saunders, Sebastien Lasvaux, et al. Operational guidance for life cycle assessment studies of the Energy-Efficient Buildings Initiative (EeBGuide). 2011.

- ISO 14040:2006 - Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework, https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed 6 November 2024).

- Silvestre, J.D.; Lasvaux, S.; Hodková, J.; de Brito, J.; Pinheiro, M.D. NativeLCA - a systematic approach for the selection of environmental datasets as generic data: application to construction products in a national context. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 731–750. [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A. Circular economy for the built environment: A research framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 710–718. [CrossRef]

- John, O.G.; Forth, K.; Theißen, S.; Borrmann, A. Estimating the Circularity of Building Elements using Building Information Modelling. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1363, 012043. [CrossRef]

- Askar, R, Karaca F, Bragança L, et al. The Role of BIM in Supporting Circularity: A Conceptual Framework for Developing BIM-Based Circularity Assessment Models in Buildings. 2024, pp. 649–658. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.; Chaves, L.; Silva, M.; Carvalho, M.; Caldas, L. Integration between BIM and EPDs: Evaluation of the main difficulties and proposal of a framework based on ISO 19650:2018. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68. [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, A.; Benghi, C.; van Berlo, L.; Hjelseth, E. Requiring Circularity Data in Bim With Information Delivery Specification. Circ. Econ. 2024, 1. [CrossRef]

- Heisel, F, McGranahan J. Enabling Design for Circularity with Computational Tools. 2024, pp. 97–110. [CrossRef]

- De Wolf C, Cordella M, Dodd N, et al. Whole life cycle environmental impact assessment of buildings: Developing software tool and database support for the EU framework Level(s). Resour Conserv Recycl 2023; 188: 106642. [CrossRef]

- Di Bari R, Horn R, Bruhn S, et al. Buildings LCA and digitalization: Designers’ toolbox based on a survey. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2022; 1078: 012092. [CrossRef]

- Hollberg, A.; Tjäder, M.; Ingelhag, G.; Wallbaum, H. A Framework for User Centric LCA Tool Development for Early Planning Stages of Buildings. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Säwén, T.; Magnusson, E.; Kalagasidis, A.S.; Hollberg, A. Tool characterisation framework for parametric building LCA. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1078. [CrossRef]

- Honic, M.; Ferschin, P.; Breitfuss, D.; Cencic, O.; Gourlis, G.; Kovacic, I.; De Wolf, C. Framework for the assessment of the existing building stock through BIM and GIS. Dev. Built Environ. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Turan, I, Fernandez J. Material Across Scales: Combining Material Flow Analysis And Life Cycle Assessment to Promote Efficiency in A Neighborhood Building Stock. 2015. Epub ahead of print 7 December 2015. [CrossRef]

- Çetin, S.; Raghu, D.; Honic, M.; Straub, A.; Gruis, V. Data requirements and availabilities for material passports: A digitally enabled framework for improving the circularity of existing buildings. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 422–437. [CrossRef]

- Charef, R. The use of Building Information Modelling in the circular economy context: Several models and a new dimension of BIM (8D). Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 100414. [CrossRef]

- Nepal MP, Jupp JR, Aibinu AA. Evaluations of BIM: Frameworks and Perspectives. In: Computing in Civil and Building Engineering (2014). Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2014, pp. 769–776.

- Gu, N.; London, K. Understanding and facilitating BIM adoption in the AEC industry. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 988–999. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Wu, P.; Yue, T. Integrating Building Information Modeling and Prefabrication Housing Production. Autom. Constr. 2019, 100, 46–60. [CrossRef]

- Lima PRB de, Rodrigues C de S, Post JM. Integration of BIM and design for deconstruction to improve circular economy of buildings. Journal of Building Engineering 2023; 80: 108015. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chang, R.; Li, Y. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for green buildings: A critical review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2017, 83, 134–148. [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, E.; Soust-Verdaguer, B.; Llatas, C.; Traverso, M. How to Obtain Accurate Environmental Impacts at Early Design Stages in BIM When Using Environmental Product Declaration. A Method to Support Decision-Making. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6927. [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Hossain, U.; Liu, M.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, M.; Chen, X.; Cao, G. BIM Integrated LCA for Promoting Circular Economy towards Sustainable Construction: An Analytical Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1310. [CrossRef]

- Freek van Eijk, Anca Turtoi, Abdulla Moustafa, et al. (PDF) Circular buildings and infrastructure - State of play report ECESP Leadership Group on Buildings and Infrastructure 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359062006_Circular_buildings_and_infrastructure_-_State_of_play_report_ECESP_Leadership_Group_on_Buildings_and_Infrastructure_2021 (2021, accessed 31 October 2024).

- Khadim, N.; Agliata, R.; Thaheem, M.J.; Mollo, L. Whole building circularity indicator: A circular economy assessment framework for promoting circularity and sustainability in buildings and construction. Build. Environ. 2023, 241. [CrossRef]

- Plociennik C, Pourjafarian M, Saleh S, et al. Requirements for a Digital Product Passport to Boost the Circular Economy. Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI), Proceedings - Series of the Gesellschaft fur Informatik (GI) 2022; P-326: 1485–1494.

- Bergquist, A.-K.; David, T. Beyond Planetary Limits! The International Chamber of Commerce, the United Nations, and the Invention of Sustainable Development. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2023, 97, 481–511. [CrossRef]

- Honic, M, Kovacic I, Rechberger H. Concept for a BIM-based Material Passport for buildings. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2019; 225: 012073. [CrossRef]

- Honic, M.; Kovacic, I.; Aschenbrenner, P.; Ragossnig, A. Material Passports for the end-of-life stage of buildings: Challenges and potentials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319. [CrossRef]

- de Araujo JB, de Oliveira JFG. Proposal of a Methodology Applied to the Analysis and Selection of Performance Indicators for Sustainability Evaluation Systems. 2008, pp. 593–600. [CrossRef]

- Illankoon, C.; Vithanage, S.C. Closing the loop in the construction industry: A systematic literature review on the development of circular economy. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107362. [CrossRef]

- Welcome to baubook — English. https://www.baubook.info/en/welcome-to-baubook?set_language=en (accessed 11 November 2024).

- BKI - Baukosteninformationszentrum für Architekten. https://bki.de/ (accessed 11 November 2024).

- DIN 276:2018 12. https://www.austrian-standards.at/de/shop/din-276-2018-12~p2452589 (accessed 12 November 2024).

| Category | Parameter | Description | Unit/Examples |

| Component | Type | Horizontal or vertical Component / Element of Building | Wall, Slab, Beam, Column, Roof, Foundation, Flooring… |

| ID Component | Identification of Component | WE01(Exterior Wall 01) | |

| Component Information | Component Layers | List of various construction components. | e.g., Tiles, Dry Screed Plate |

| ID Layer | Identification of Layer | WE01-01 | |

| Corresponding Construction Layers | Specific types of materials used in construction. | e.g., FERMACELL gypsum fiber screed | |

| Lifespan | Expected lifespan of each material. Note: Over 100 years, the initial data will be multiplied by the number of times indicated by the lifespan. | Number of years (e.g., 10, 25, 35, 50, 100 years) | |

| Thickness of Layers | Thickness of each material layer. | Measurement in meters (e.g., 0.015 m) | |

| Material Properties | Material Classification | Classification based on the function of the material. | e.g., Flooring, Insulation |

| Building Material Category | Type of material based on composition. | organic, mineral, metallic | |

| Harmful Substances | List of harmful substances contained in the material / layer. | e.g., KMF, DEHP, H/F/C/KW, PAK | |

| Density | Density of each material / component layer | kg/m³ (e.g., 2300 kg/m³) | |

| Environmental Impact Metrics | GWP | Potential contribution to global warming. | kg CO2 eq./kg |

| AP | Potential to contribute to acidification. | kg SO2 eq./kg | |

| Primary Energy Non Renewable total (PENRT) | Primary Energy Non Renewable total. Primary energy input. | MJ/kg | |

| Disposal Classification | Dimensionless classification categorizing disposal difficulty, impacting waste volume calculations via multipliers. | Dimensionless (classification scale) | |

| Recycling Potential | Expressed as a percentage, indicating recyclability and potential for waste reduction. | Percentage (%) | |

| Mass and Environmental Impact | Mass per Area | Mass of material per square meter. | kg/m² |

| Mass at Construction | Mass of the material at the time of construction. | kg | |

| Mass after 100 Years | Mass of the material after 100 years. | kg | |

| Waste and Recycling Potential | Recycling Potential | Classification of the material’s potential for recycling and disposal. | Potential rating from 1 to 5 (e.g., high to medium to low) |

| Recyclable Mass at Construction | Mass of material that can be recycled after EOL considered at the time of construction. | kg | |

| Waste Mass at Construction | Mass of material that becomes waste after EOL considered at the time of construction. | kg | |

| Recyclable Mass after 100 Years | Mass of material that can be recycled after 100 years. Recyclable Mass at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | kg | |

| Waste Mass after 100 Years | Mass of material that becomes waste after 100 years. Waste Mass at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | kg | |

| Environmental Impact at Different LC- Stages |

GWP at Construction | Environmental impact in terms of GWP at the time of construction. | t CO2 eq. |

| AP at Construction | Environmental impact in terms of AP at the time of construction. | kg SO2 eq. | |

| PENRT at Construction | Primary energy non renewable total at the time of construction. | GJ | |

| GWP(100) after 100 Years | Environmental impact in terms of GWP after 100 years. GWP at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | t CO2 eq. | |

| AP after 100 Years | Environmental impact in terms of AP after 100 years. AP at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | kg SO2 eq. | |

| PENRT after 100 Years | Primary energy non renewable total after 100 years. PENRT at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | GJ | |

| GWP Storage | The amount of CO2 stored in biogenic materials, expressed in kg or t CO2 eq./m² | t CO2 eq. | |

| Cost Information | Costs at Construction | Cost per square meter for each material/component as of 2022. | €/m² |

| Costs after 100 Years | Cost per square meter for each material/component after 100 years. Cost at Construction * (100 / Lifespan) | €/m² |

| Metric | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| GWP | Measures greenhouse gas emissions for each material, assessing climate change impact. | kg CO₂-equivalent |

| AP | Calculates emissions contributing to acidification, assessing impacts on ecosystems, infrastructure, and health. | kg SO₂-equivalent |

| Primary Energy Non-Renewable Total (PENRT) | Indicates total non-renewable energy consumed throughout a material’s lifecycle, reflecting resource depletion. | Megajoules (MJ) |

| Disposal Classification | Dimensionless classification categorizing disposal difficulty, impacting waste volume calculations via multipliers. | Dimensionless (classification scale 1 to 5) |

| Recycling Potential | Expressed as a percentage, indicating recyclability and potential for waste reduction. | Percentage (%) |

| Lifespan per Layer | Represents expected service life of each material element layer, accounting for durability and replacement cycles. | Years (yr) |

| Element | At Year of Construction | After 100 Years EoL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWP(100) [t CO2 eq.] |

AP [kg SO2 eq.] |

PENRT [GJ] |

GWP(100) [t CO2 eq.] |

AP [kg SO2 eq.] |

PENRT [GJ] |

|

| Slabs and Ceilings | -51,65 | 2447,59 | 9136,02 | 32,62 | 3552,29 | 13435,51 |

| Walls | -306,3 | 1001,87 | 3663,38 | -525,52 | 1901,78 | 7002,49 |

| Beams | 3,31 | 42,74 | 254,05 | 30,05 | 42,74 | 254,05 |

| Columns | 21,86 | 73 | 326,56 | 21,86 | 73 | 326,56 |

| Stairs | 8,96 | 23,82 | 92,02 | 8,96 | 23,82 | 92,02 |

| Foundations | 23,63 | 62,81 | 242,65 | 23,63 | 62,81 | 242,65 |

| Sum | -300,19 | 3651,83 | 13714,68 | -408,4 | 5656,44 | 21353,28 |

| Elements after 100 Years EoL | Recyclable Mass [t] | Disposal Mass [t] |

| Concrete Slab - General | 695,93 | 772,82 |

| Concrete Slab - Kitchen/Bathroom | 94,00 | 116,48 |

| Concrete Slab - Living Area | 261,57 | 325,65 |

| Wooden Ceiling - Kitchen/Bathroom | 146,54 | 177,32 |

| Wooden Ceiling - Living Area | 492,12 | 600,05 |

| Wooden Flat Roof | 119,92 | 120,18 |

| Concrete Balcony | 306,45 | 306,45 |

| Exterior Wall 01 | 32,69 | 36,67 |

| Exterior Wall 02 | 58,40 | 139,76 |

| Interior Wall 01 | 59,32 | 135,66 |

| Interior Wall 02 | 52,96 | 52,96 |

| Partition Wall | 50,29 | 170,03 |

| Shaft Walls | 7,42 | 14,05 |

| Attica | 13,53 | 30,17 |

| Concrete Beams | 49,78 | 49,78 |

| Glulam Beams | 8,12 | 2,71 |

| Steel Beams | 0,39 | 0,13 |

| Concrete Columns | 85,07 | 85,07 |

| Glulam Columns | 3,73 | 1,24 |

| Steel Columns | 0,34 | 0,11 |

| Concrete Stairs | 27,76 | 27,76 |

| Wooden Windows | 19,88 | 19,88 |

| Glass Surfaces Windows | 20,61 | 20,61 |

| Wooden Doors | 11,67 | 3,89 |

| Glass Surfaces Doors | 24,37 | 24,37 |

| Concrete Foundations | 73,20 | 73,20 |

| Sum Mass [t] | 2716,05 | 3306,99 |

| Component | At Construction (€) | After 100 Years (€) | Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slabs and Ceilings | 1,749,324.11 | 2,258,235.42 | 29.06% |

| Walls | 1,099,900.92 | 1,706,316.42 | 55.12% |

| Beams | 118,544.09 | 118,544.09 | 0% |

| Columns | 200,372.80 | 200,372.80 | 0% |

| Stairs | 50,048.93 | 50,048.93 | 0% |

| Windows | 462,468.37 | 1,387,405.12 | 200.05% |

| Doors | 470,244.18 | 1,258,845.62 | 167.60% |

| Foundations | 22,513.61 | 22,513.61 | 0% |

| Total | 4,173,417.02 | 7,002,282.01 | 67.73% |

| Incl. 20% VAT | 5,008,100.42 | 8,402,738.41 |

| Component | Difference (€) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Interior Wall Wood | -141.09 | 47% |

| Interior Wall Gypsum | -75.16 | 50% |

| Beam Glulam | 14,406.87 | 16% |

| Window | 206.13 | -46% |

| Foundation Concrete | 119.08 | -48% |

| Future Research |

Description | Expected Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration Interoperability | Develop systems that integrate data from environmental metrics, cost benchmarks, and external databases. Ensure interoperability between building models and various databases to enable smooth data exchanges across project stages. | Enhanced collaboration among stakeholders and informed decision-making through consistent data flow and reduced information silos. |

| Automated Calculation of Key Metrics | Focus on automating the calculation of critical metrics (GWP, AP, PENRT, recycling/disposal rates) and dynamically link them to model components. | Improved efficiency and accuracy in environmental impact assessments, allowing immediate reflection of design/material changes in circularity and sustainability assessments. |

| Flexible Assessment Approaches | Research variant-based approaches for assessing area, volume, mass, environmental impacts, and economic implications, independently or in combination, to cater to specific project requirements. | Iterative design processes by offering flexible assessments, supporting quick adjustments as project details evolve. |

| Interactive Dashboards | Develop real-time dashboards with features such as component-specific impacts, aggregate project impacts, and benchmarking against industry standards. | Monitor circularity and environmental impacts in real time, suggesting material/process improvements and encouraging continuous improvement. |

| Decision-Support Tool | Create decision-support tools that provide real-time feedback on environmental and economic implications, with scenario analysis for testing materials, configurations, and circularity measures. | Design choices, optimizing for both sustainability and cost-efficiency through informed scenario-based decisions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).