1. Introduction

The use of block-shaped bone grafts for three-dimensionally stable alveolar ridge augmentations remains a challenge when non-autogenous grafting material is considered. In particular, xenogenic and synthetic block grafts are difficult to use, as the brittle material characteristics often impairs precise adaptation and fixation to the underlying bone. In this respect, the use of 3D data of the individual defect anatomy for additive manufacturing of 3D scaffolds constitutes a promising approach to the production of individually preshaped bone graft blocks for alveolar bone repair. The major advantages of this technique are not only the ability to adjust the shape of the scaffolds to the individual anatomy of bone defects but also the possibility to vary material composition according to the individual requirements of the recipient bed (Lindner et al 2010, Alonso-Fernandez et al. 2023). A frequently employed process for the manufacturing of 3D scaffolds is selective laser melting (SLM) or selective laser sintering (SLS), where a 3D object is printed layer by layer through a laser beam in a powder bed (Hokmabad et al. 2017, Bose et al. 2018). Selective laser melting uses temperatures at which the powder is completely melted and is preferably employed for the production of patient specific metallic implants whereas SLS uses temperatures just below the melting point of the material that can fuse together molecularly on the surface of the powder particles, which leads to sintering of the powder thus defining the 3D shape without entire melting of the material (Bose et al. 2018). This approach is particularly suitable for printing of resorbable polymer scaffolds (Xia et al. 2013, Du et al. 2017, Sun et al. 2020, Li et al. 2023).

The most frequently used degradable polymers in medicine are composed of poly-alpha-hydroxy acids such as poly-lactic acid (PLA), poly-glycolic acid (PGA), poly-caprolactone (PCL) (Ali et al. 1993) or poly-dioxanone (PDA) (Hutmacher et al. 1996). Particularly, the use of PLA and PGA is associated with the occurrence of acidic degradation products that can to lead to foreign body reactions and inhibit bone contact with the surface of resorbable polymer PLA scaffolds by formation of an intervening soft tissue layer (Pihlajamäki et al. 2006 & 2010, Nonhoff et al. 2024). The decrease in periimplant pH associated with these acidic degradation products can be avoided by the addition of basic CaCO3 or Ca PO4 particles during scaffold production. This has been shown to lead to a near constant physiological pH in vitro during the entire process of degradation of resorbable PDLLA scaffolds produced through supercritical gas foaming of poly-DL-lactic acid-ACP-CaCO3-powder (Schiller et al. 2004). In vivo, addition of basic particles such as hydroxylapatite has been associated with direct contact between bone and the polymer composite (Kawai et al. 2021, Akagi et al. 2014). The use of SLS for the production of resorbable scaffolds from poly-lactic acid- CaCO3 powder would allow for the creation of degradable block-shaped bone grafts with a well-controlled open porosity in the µm range, which can allow for bone ingrowth and at the same time avoid untoward effects of polymer degradation on bone formation. The feasibility of this approach on the material side has already been shown in in vitro studies (Gayer et al. 2019). The present experimental pilot study was therefore conducted to evaluate the in-vivo performance of additively manufactured 3D resorbable polymer scaffolds produced through SLS from PLA-CaCO3 / CaP powder with different pore volume and compositions. The necessary preparatory work for material characterisation and biocompatibility testing was carried out at Innovent. The aim of the study was to test the hypothesis that modifications in scaffold architecture and material composition have an effect on bone ingrowth into the macroporous resorbable scaffolds.

2. Materials and Methods

The mini pig was chosen as experimental animal for the in vivo testing for three reasons: i) the anatomy allows for the testing of clinically relevant scaffold volumes, ii) the species is well established in preclinical research on implants and bone regeneration, iii) bone physiology and bone turn over are comparable to humans (Pearce et al. 2007). For the present pilot study on material characteristics, the tibia diaphysis was chosen for implant placement to avoid complications with wound dehiscences and subsequent infections frequently encountered with transoral procedures in ridge defects in this species (Tröltzsch et al. 2017, Gruber et al. 2009). Four types of implants were planned (see below) and two intervals were scheduled for evaluation (4 and 13 weeks).

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

The number of animals needed was calculated according to Meads resource equation E=N-B-T (Mead 1988). This equation is designed to save resources in complex biological experiments with multiple treatments. N is the total number of experimental units (defects), B is the number of blocking effects (environmental conditions, housing or grouped treatment) and T is the number of treatment groups. If the number of experimental units N is adequate, E should have a value between 10-20 (Festing 2011).

In the experimental design, four defects were planned per animal in the tibiae on one side. Hence the number of blocking effects B (grouped treatment) would be B = N/The experiments involved four treatments (two variations in scaffold architecture and two variations in material composition). With results being assessed at 2 intervals (after 4 and 13 weeks), a factorial design of 4 treatments x 2 intervals resulted in 8 groups. With a maximum value of E = 20, the maximum number of experimental units N (defects) required is calculated by 20 = N – N/4 -8. resulting in N = 37.3 defects, which was equivalent to 9.3 animals. Hence, the number of animals used was n=10 with 5 animals each being assigned to the two intervals.

2.2. Scaffold Production

The scaffolds were produced through selective laser sintering of a composite powder of poly-L-lactide combined with CaCO3 with and without surface modification with CaP. The addition of CaP was intended to improve the bioactivity of the scaffold with respect to bone formation. The composite powder had been produced and characterized by Schaefer Kalk as previously described (Gayer et al. 2019). In brief, poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) (Resomer L206 S, Evonik) granules and spherulite-shaped precipitated calcium carbonate-with and without CaP coating (4%) were dry processed in an impact mill (NHS-1, Tokyo 143, Japan) at 6,400 rpm leading to an inclusion of the spherulites into the PLLA granules. The volume fraction of the CaCO3 / CaCO3-CaP spherulites in the composite particles was approximately 24%. The median particle size of the resulting composite particles ranged between 55 and 57 μm.

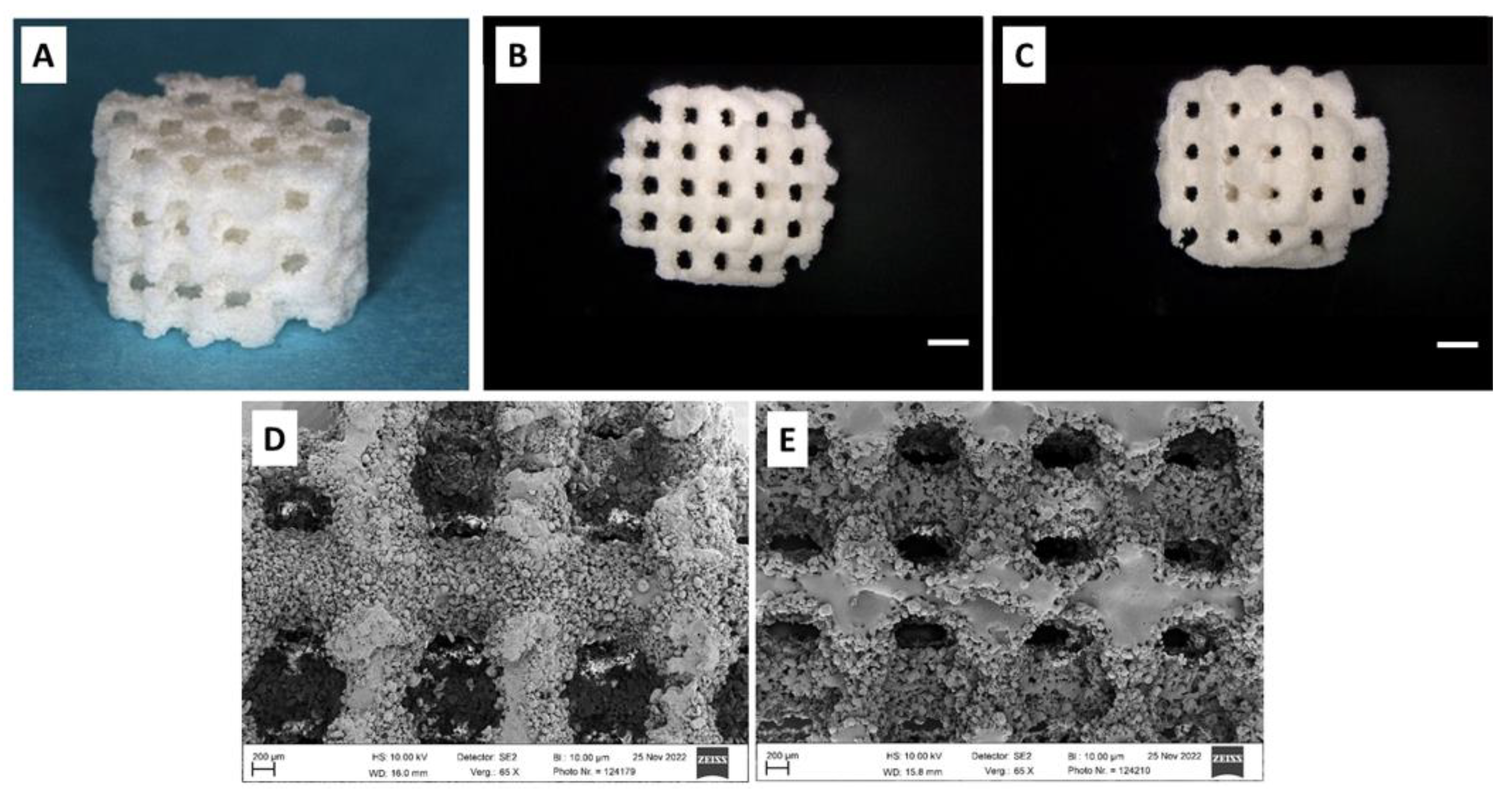

The scaffolds were designed and produced by KLS Martin on an SLS machine (Formiga P110 Velocis, EOS GmbH, Krailling / München, Germany, focus diameter: 220 µm, 2.2 W, 1,200 mm/sec) in cylindrical shape of 7 mm diameter and 5 mm height resulting in a scaffold volume of 192 mm³ (Fig. 1A). The scaffold architecture was varied in thickness of scaffold webs between pores (1000 µm and 800 µm) with a constant pore size of 400 µm, resulting in two different pore volumes (69 m³ and 79 mm³*, equivalent to a porosity of 35.9% and 41.1%, respectively). In conjunction with the two different types of composite powder, four types of scaffolds were produced (Fig. 1B through E):

Group 1) PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³ / 35.9% porosity)

Group 2) PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 79 mm³ / 41.1% porosity)

Group 3) PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³ / 35.9% porosity)

Group 4) PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 79 mm³ / 41.1% porosity)

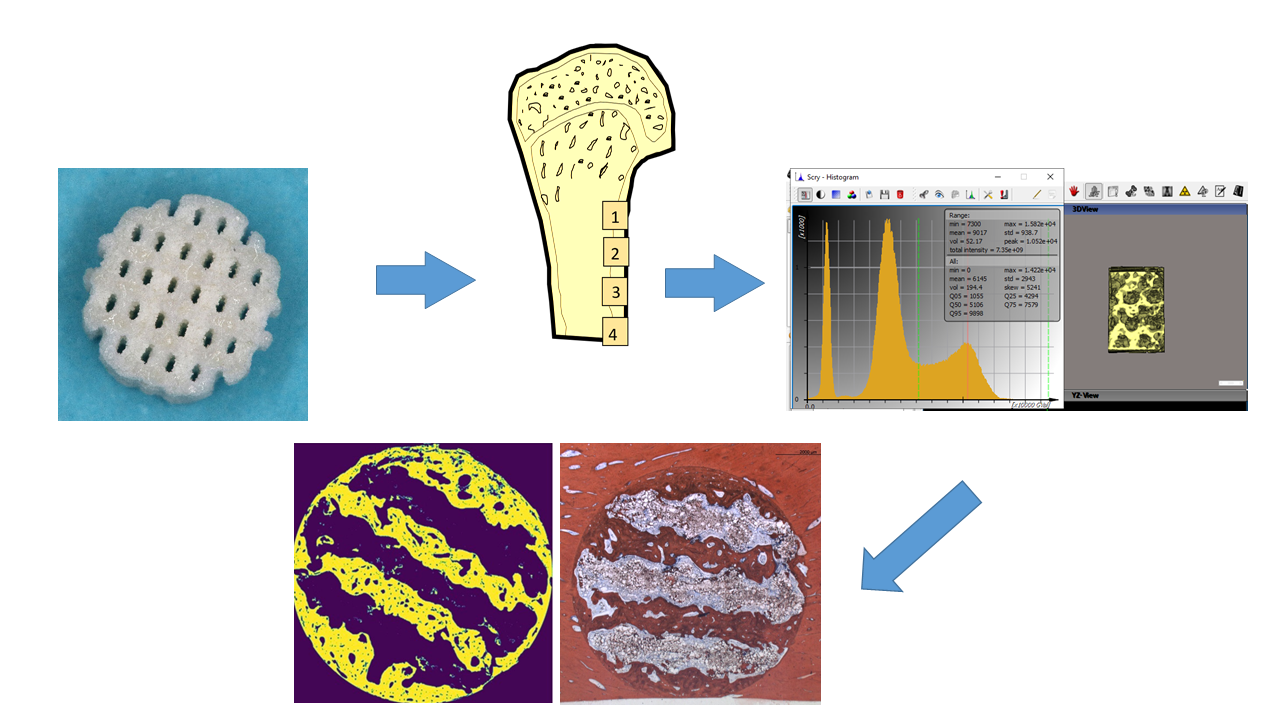

Figure 1.

A: Cylindrical scaffold of 7 mm diameter and 5 mm height; B: Scaffold with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, Bar: 1 mm, C: scaffold with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness; Bar: 1 mm; D: PLLA-CaCO3 scaffold, Bar: 200 µm, E: PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffold; a large number of unmelted polymer composite granules is attached to the scaffold surface as residuals after laser sintering, Bar: 200 µm.

Figure 1.

A: Cylindrical scaffold of 7 mm diameter and 5 mm height; B: Scaffold with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, Bar: 1 mm, C: scaffold with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness; Bar: 1 mm; D: PLLA-CaCO3 scaffold, Bar: 200 µm, E: PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffold; a large number of unmelted polymer composite granules is attached to the scaffold surface as residuals after laser sintering, Bar: 200 µm.

2.3. Surgical Procedures

All surgical procedures, housing and animal care were carried out in accordance with the German legislation for animal protection and the regulations for animal experiments of the state of Lower Saxony. The trials were reported and admitted under the license number 33.19-42502-04-21/3774 of the Office for consumer protection and food safety of Lower Saxony (LAVES). Surgical experiments were only admitted to be performed on one leg per animal. Animals were held in groups of 2 – 3 animals in cages with concrete floor with saw dust bedding and wooden walls. They were allowed to accommodate for four weeks prior to the beginning of the clinical procedures. All animals presented in good health. All surgical procedures were conducted in the animal facilities of the University Medicine Goettingen following the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010).

The experiments were conducted between 07/2022 and 12/Qualified veterinarians performed the sedation and general anesthesia as well as the postoperative care. Sedation was initiated by an orally administered dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight of Diazepam followed by intramuscular injection of 7.5 mg/kg body weight Ketamine and 0.375 mg/kg body weight Midazolam i.m. approximately 30 minutes later. General anesthesia was induced with titrated i.v. administration of 1-2-mg/kg Propofol and 10 µg/kg Fentanyl, followed by endotracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained using of Propofol (5-8-mg / kg / h) and Fentanyl (10 - 15 µg / kg / h). A Dexpanthenole lotion (Bepanthen©, Bayer AG, 51368 Leverkusen, .Germany) was used to cover the eyes. Vital parameters were monitored using ECG, pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2 measurement and rectal body temperature.

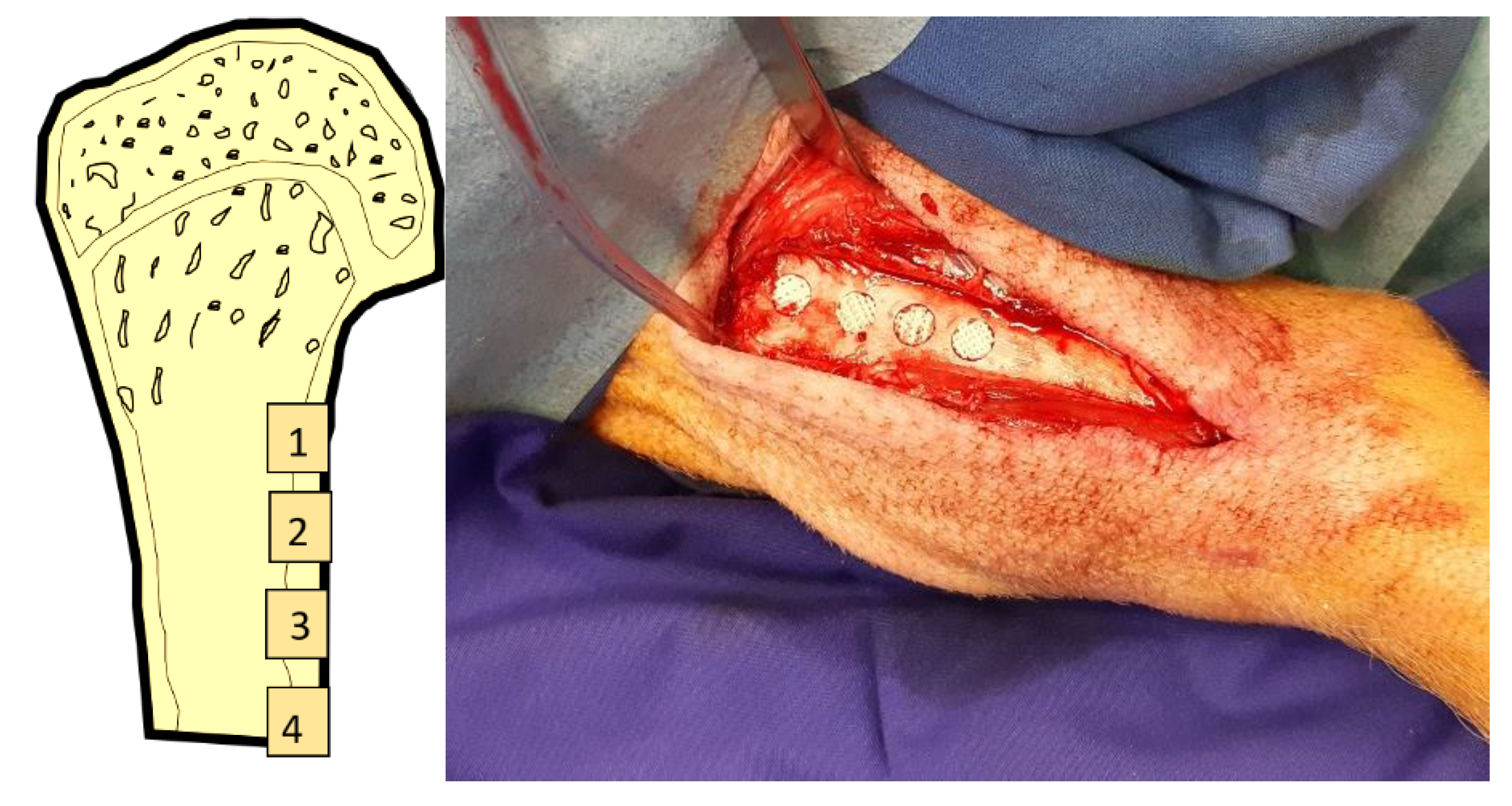

The tibia on one side was exposed subperiosteally from an anterior incision. The side in each animal was assigned randomly through drawing lots. Cylindrical cavities of 7 mm diameter and 5 mm depth were created in the diaphysis in a linear fashion approx. 1 cm apart (Fig. 2a and b). The implants were inserted pressfit into the defects. Wound closure was performed in layers using resorbable sutures (Vicryl 3.0, Ethicon, Norderstedt). The position of the individual scaffolds was allocated randomly through drawing lots.

Figure 2.

A:Clinical picture of implant placement; B: schematic illustration of implant locations in the minpig tibia.

Figure 2.

A:Clinical picture of implant placement; B: schematic illustration of implant locations in the minpig tibia.

During the immediate postoperative period (1 week) animals were visited twice per day. For reduction of postoperative pain 5 mg/kg body weight Carprofen were administered orally daily during the first postoperative week. When animals showed signs of discomfort 50 mg / kg body weight Metamizol were administered orally.

During the postoperative period tibial fractures occurred in 4 out of the 10 animals resulting in 6 animals remaining in the experiment. As the number of 24 defects that were available in these 6 animals, was equivalent to the minimum number of animals required according to the Meads equation used for sample size calculation, it was concluded to continue with the reduced number of animals.

2.4. Outcome parameter

The tibia of 3 animals each were removed after 4 weeks and 13 weeks with retrieval of scaffolds together with adjacent bone using a diamond saw (EXAKT©, Robert-Koch-Str. 5, 22851 Norderstedt). The following outcome parameters were defined:

- -

Primary outcome parameters:

Bone formation and pore volume fill assessed through µCT (mm³)

Bone formation assessed through histomorphometry (mm²)

Osteocalcin-Expression assessed through immune-histochemistry (mm²)

2.5. Micro-CT, Histologic Preparation and Morphometry

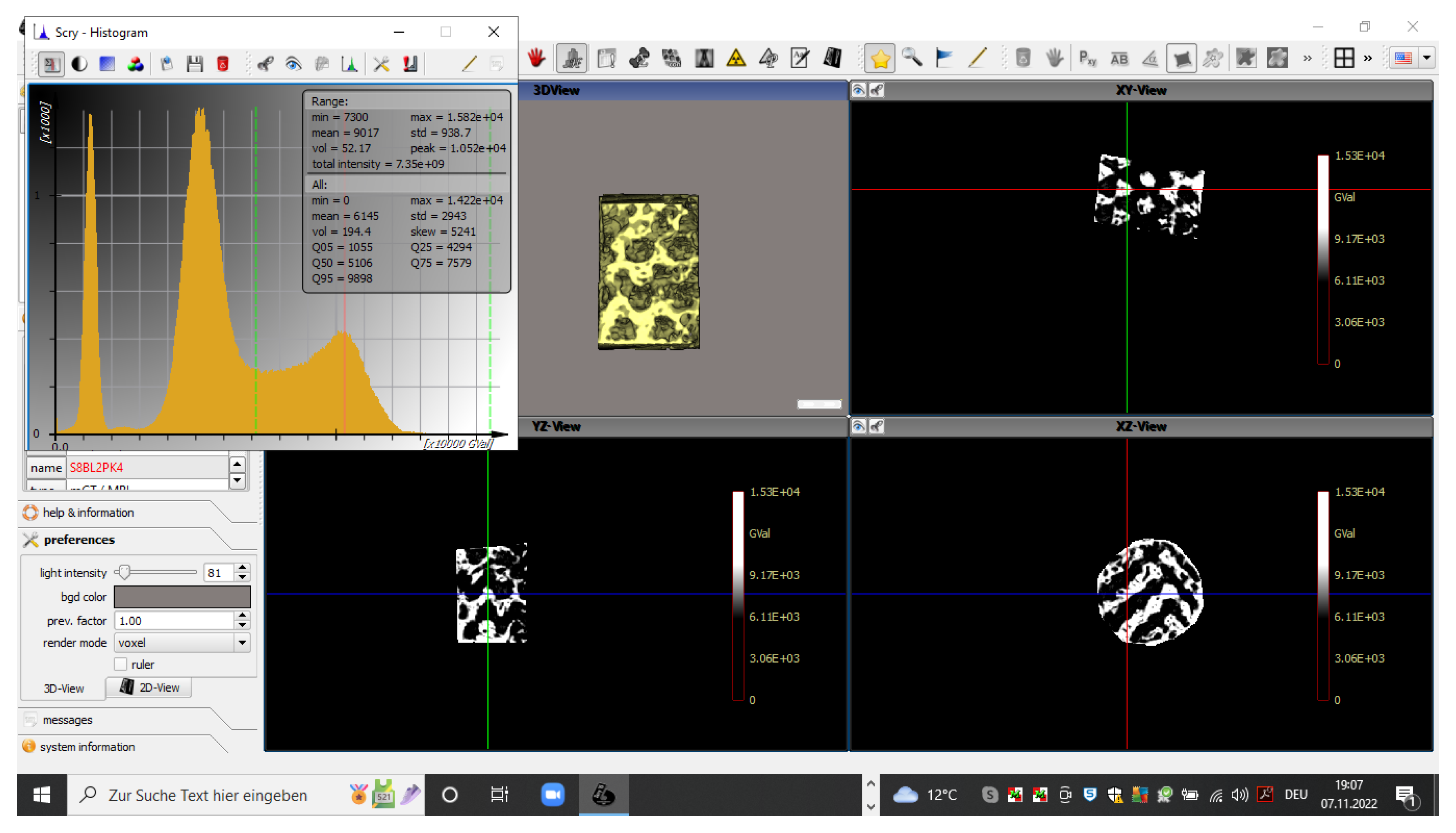

Before preparation for histologic and morphometric evaluation, the scaffolds were submitted analysis in a µCT device (QuantumFX, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using low-resolution scans (90kV, 200 µA, field-of-view 20x20 mm² and 10x10² witm, respectively. The resulting density data were analysed using a threshold-based algorithm (Scry 6.0, C. Dullin)(Fig. 3) across a volume corresponding to the 7 x 5 mm cylindrical block volume with 0.1 mm allowance. The density range of newly formed bone was defined using density values of >7300 arbitrary units and the volume was assessed in mm³. Pore volume fill was calculated from the technically defined pore volumes of 69 mm3 and 79 mm3, respectively.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of a histogram distribution of density values. Identification of bone inside the scaffolds using density values of >7300 arbitrary units (dotted green line in the histogram). Display of identified bone tissue in xyz planes.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of a histogram distribution of density values. Identification of bone inside the scaffolds using density values of >7300 arbitrary units (dotted green line in the histogram). Display of identified bone tissue in xyz planes.

For histologic preparation, the scaffolds with the surrounding bone were dehydrated and embedded into Technovit 9100© (Heraeus Kulzer GmbH, Philipp-Reis-Str. 8/13, 61273 Wehrheim, Germany). Thick section specimens were produced using a laser microtome ((Tissue Surgeon, LLS ROWIAK, Hannover) (Line Oberlap: 60 %, Pulse Overlap: 77 %, Pulse energy: 130 nJ, Index of Refraction: 1,5, Pulse Frequency: 10 MHz, Cutting depth: 50-55 µm) at a thickness of 40-45 µm perpendicular to the trephine defect axis. Approximately, 10 to 12 specimens were produced from each implant and its surrounding bone perpendicular to the axis of the trephine cavity and divided between

- -

surface staining for histomorphometric assessment of bone formation using Alizarine red / Methylene Blue and van Gieson stains.

- -

immunohistochemical staining of Osteocalcin, using Peroxidase staining. For immunohistochemical staining, specimens were mounted on Adhesive Microscope Slides (3800200AE, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and deplastisized (according to ROWIAK, Hannover, Germany) by incubation in a mixture of xylene and MMA (1:1; Methyl methacrylate, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 24 h, followed by incubation in xylene for 20 h. The specimens were then rehydrated in descending concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95%, 70%, for 5 min each) and washed in deionized water for 5 min. Deplasticized and rehydrated bone tissue sections were incubated in 1x citrate-based Target Retrieval Solution, pH 6.0 (Agilent Dako, Waldbronn, Germany) at 60°C overnight. Afterwards, the sections were washed for 10 min in deionized water and three times in TBS for 5 min each, following treatment with 1 ml Trypsin Solution and 3 ml Trypsin Buffer (Trypsin Pretreatment Kit, Zytomed Systems, Berlin, Germany) in a humidity chamber at 37°C for 20 min. The sections were washed for 5 min in deionized water and three times in TBS, 5 min each. To block endogenous peroxidase activity, the specimens were incubated with Peroxidase-Blocking Solution (Dako, Waldbronn, Germany) in a humidity chamber at room temperature (RT) for 17 min and rinsed with TBS for three times, 5 min each. Next, the samples were incubated in a humidity chamber for 1h at RT in blocking buffer (10% goat Serum Block in PBS, Histoprime Biozol, Eching, Germany). Immunostaining was performed by incubation with a 1:50 dilution of BGLAP (Osteocalcin) monoclonal antibody (ABN-H00000632-M01, Abnova Biozol, Eching, Germany; humidity chamber, overnight at 4°C) followed by washing three times in TBS for 5 min each and incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Goat anti-Mouse, A10551, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, USA ; 1:250, humidity chamber, 1h at RT). The antibodies were diluted using Antibody Diluent (Agilent Dako, Waldbrunn, Germany). After the samples were washed three times in TBS, 5 min each, the reactivity was detected using DAB (3,3´-Diaminobenzidine) substrate (Liquid DAB Substrate-Chromogen System, Agilent Dako, Waldbrunn, Germany; 20 min at RT). The reaction was stopped with deionized water, and the sections were rinsed four times in deionized water. Subsequently, specimens were counterstained with Mayer´s hemalaun solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 4s at RT followed by incubation for 5 min in tap water at RT. The samples were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (70% for 2 min, 96% twice for 2 min each, 100% twice for 5 min each) followed by clarification in xylene for 5 min. Finally, the specimens were mounted with Entellan (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and dried for 48 h at RT. Sections stained without the primary antibody served as controls.

For histomorphometric evaluation of bone formation, the specimens were scanned through a high resolution camera (Axioskop 2 plus mit Axio Cam MRc5, Zeiss GmbH, Jena) at 1.25 x magnification. For evaluation of immunohistochemistry, the specimens were scanned using a motordriven table and a microscope camera (Zeiss Axiovert 200M / AxioCam MRc Rev.3.FireWire, Zeiss, GmbH, Jena, Germany) at 10x magnification.

The resulting digital image data were analysed using a custom-made Python3 based image analysis pipeline (C.D.) utilizing the common Python modules scikit-image, matplotlib, opencv and pandas.

For histomorphometry of both bone formation and Osteocalcin expression, the algorithm automatically identified the color of the van Gieson / Peroxidase stained areas in the respective cross-section specimens and assessed the area occupied by bone and positive Osteocalcin expression, respectively, in absolute values by pixel counting. Pixels were converted in mm² using the calculated pixel size of 4.17 µm² / pixel for bone morphometry and 2.39 µm² / pixel for Osteocalcin expression. The area of interest was defined as the circular crossectional area of the scaffolds. For subsection analysis, the area was divided into a central, intermediate and periphery zone (Fig. 4A - D).

Figure 4.

A-D. Subsection analysis of central, intermediate and periphery of as well as the entire cross section area of the scaffolds.

Figure 4.

A-D. Subsection analysis of central, intermediate and periphery of as well as the entire cross section area of the scaffolds.

2.6. Statistics

Results were reported as means and standard deviation. Results were tested for normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilkes tests for each of the variables. Only for 4 out of the 40 variables, a p-values < 0.05 resulted indicating that 90% of the variables had a normal distribution. Mean values of the area of newly formed bone as well as pore volume fill and area of positive OC expression were compared between the four scaffolds using repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing in pairwise comparisons. Comparison between the 4 and 13 week intervals was performed using t-tests for unpaired samples (SPSS Statistics 24.0,

http://support.spss.com). The significance level was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

As mentioned before, four out of the 10 animals suffered a tibial fracture resulting in 6 animals remaining in the experiment. These animals healed well without any further signs of complications.

3.1. Histology

After 4 weeks, bone formation extended 1 – 2 mm into the scaffold pores (Fig. 5 A-D). There was some degree of superficial disintegration visible with polymer particles being detached from the scaffold surface into the pore lumina surrounded by soft tissue. In many areas, the newly formed bone tissue was in immediate contact with the scaffold surface (Fig. 6A). After 13 weeks, bone tissue had almost completely penetrated the scaffold volume along the pore structure (Fig. 5 E-H). Most of the detached particles had been degraded and bone tissue was in direct contact to the scaffold surface with bone formed on the surface and inside the scaffold material between the polymer grains (Fig. 6B). There was no obvious difference with respect to morphology nor pattern of bone formation between the four different groups.

Figure 5.

Representative cross sections through the scaffolds, Alizarin-Methylene Blue stain (Bar: 2000 µm): Upper row 4 weeks: A: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); B: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); C: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³)) D: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³) .

Figure 5.

Representative cross sections through the scaffolds, Alizarin-Methylene Blue stain (Bar: 2000 µm): Upper row 4 weeks: A: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); B: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); C: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³)) D: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³) .

Lower Row: 13 weeks E: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); F: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); G: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³); H: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³)

Figure 6.

A:Bone ingrowth into scaffolds from the defect wall after 4 weeks. Direct contact between bone and scaffold material, detached polymer particles in the vicinity of the scaffold surface. Ca containing particles can be seen from the red Alizarin stain inside the scaffold material (Bar: 250 µm); B: Resorption of polymer particles through multinuclear giant cells (asterisk) (Bar 50 µm) C: Bone formation in the central parts of the scaffold showing bone formation directly on the scaffold surface (Bar: 250 µm).

Figure 6.

A:Bone ingrowth into scaffolds from the defect wall after 4 weeks. Direct contact between bone and scaffold material, detached polymer particles in the vicinity of the scaffold surface. Ca containing particles can be seen from the red Alizarin stain inside the scaffold material (Bar: 250 µm); B: Resorption of polymer particles through multinuclear giant cells (asterisk) (Bar 50 µm) C: Bone formation in the central parts of the scaffold showing bone formation directly on the scaffold surface (Bar: 250 µm).

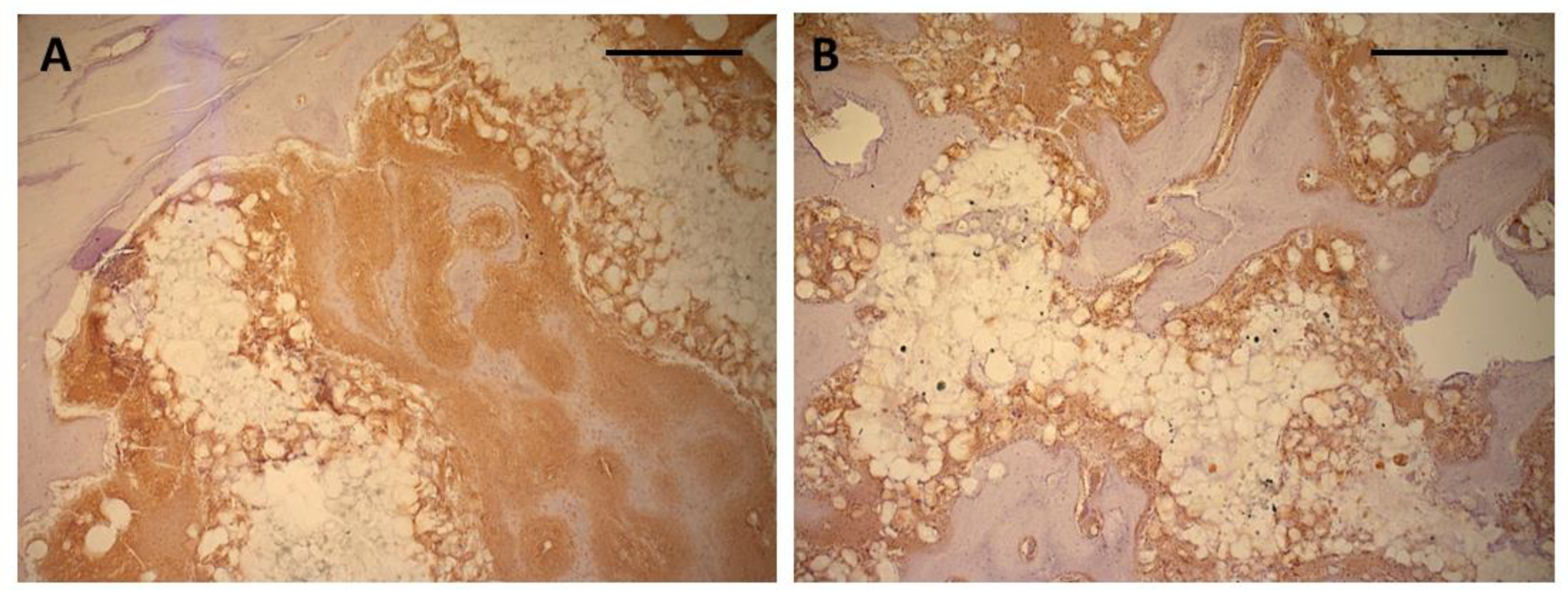

3.2. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for osteocalcin showed extensive positive reaction evenly distributed throughout the entire soft tissue inside the scaffold after 4 weeks (Fig. 7A-D). Both the matrix adjacent to the immature bone as well as the soft tissue in immediate contact with the scaffold material showed exhibited intense staining for osteocalcin (Fig. 8A). After 13 weeks, the areas of osteocalcin expression had substantially decreased being limited to narrow seams of positively stained tissues on the surface of the newly formed bone (Fig. 7 E-H). Positive staining extended into the scaffold material between the polymer grains and around the detached polymer particles (Fig. 8B).

Figure 7.

Representative cross sections through the scaffolds, Peroxidase stain for Osteocalcin (Bar: 2000 µm): Upper row 4 weeks: A: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); B: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); C: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³)) D: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³) .

Figure 7.

Representative cross sections through the scaffolds, Peroxidase stain for Osteocalcin (Bar: 2000 µm): Upper row 4 weeks: A: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); B: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); C: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³)) D: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³) .

Lower Row: 13 weeks E: Group 1 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness (pore volume 69 mm³); F: Group 2 / PLLA-CaCO3 scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³); G: Group 3 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 1000 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 69 mm³); H: Group 4 / PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffolds with 800 µm scaffold web thickness, (pore volume 78 mm³).

Figure 8.

A: Intense positive reaction for osteocalcin in immature ingrowing bone after 4 weeks. Soft tissue invading the scaffold material has also shown positive reaction in direct contact with the scaffold surface. (Bar: 500 µm); B: smaller seams of positively stained tissue between newly formed bone and scaffold surface in the center of the scaffolds after 13 weeks (Peroxidase stain for Osteocalcin, bar: 500 µm).

Figure 8.

A: Intense positive reaction for osteocalcin in immature ingrowing bone after 4 weeks. Soft tissue invading the scaffold material has also shown positive reaction in direct contact with the scaffold surface. (Bar: 500 µm); B: smaller seams of positively stained tissue between newly formed bone and scaffold surface in the center of the scaffolds after 13 weeks (Peroxidase stain for Osteocalcin, bar: 500 µm).

3.3. Histomorphometry & µCT

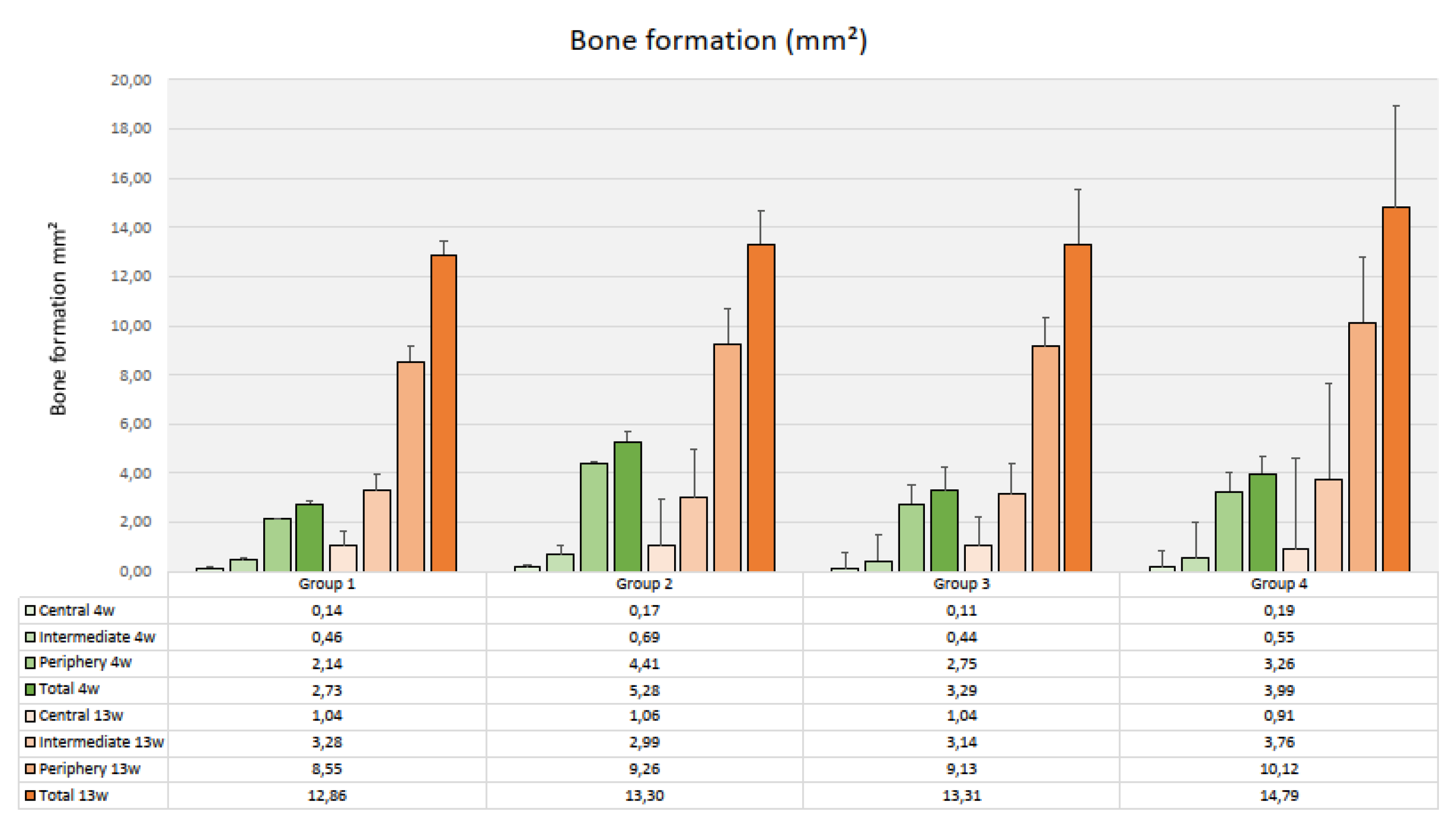

After 4 weeks, the amount of newly formed bone varied considerably between a mean total area of 2.73 mm² (SD 0.81) in Group 1 (PLLA-CaCO3, 69 mm³ pore volume) and 5.28 mm² (SD 1.8) in Group 2 (PLLA-CaCO3, 79 mm³ pore volume) (Fig. 9). Differences in mean values were not significant between the four types of scaffolds (p=0.156) .There was a clear decrease in bone formation from the periphery to the center of the scaffolds that was significant for all scaffold types (p-values varied from 0.002 to 0.019). Bone formation in the individual zones was not significantly different between the four types of scaffolds.

Figure 9.

Bone formation inside the scaffolds (Histomorphometry, mm², mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

Figure 9.

Bone formation inside the scaffolds (Histomorphometry, mm², mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

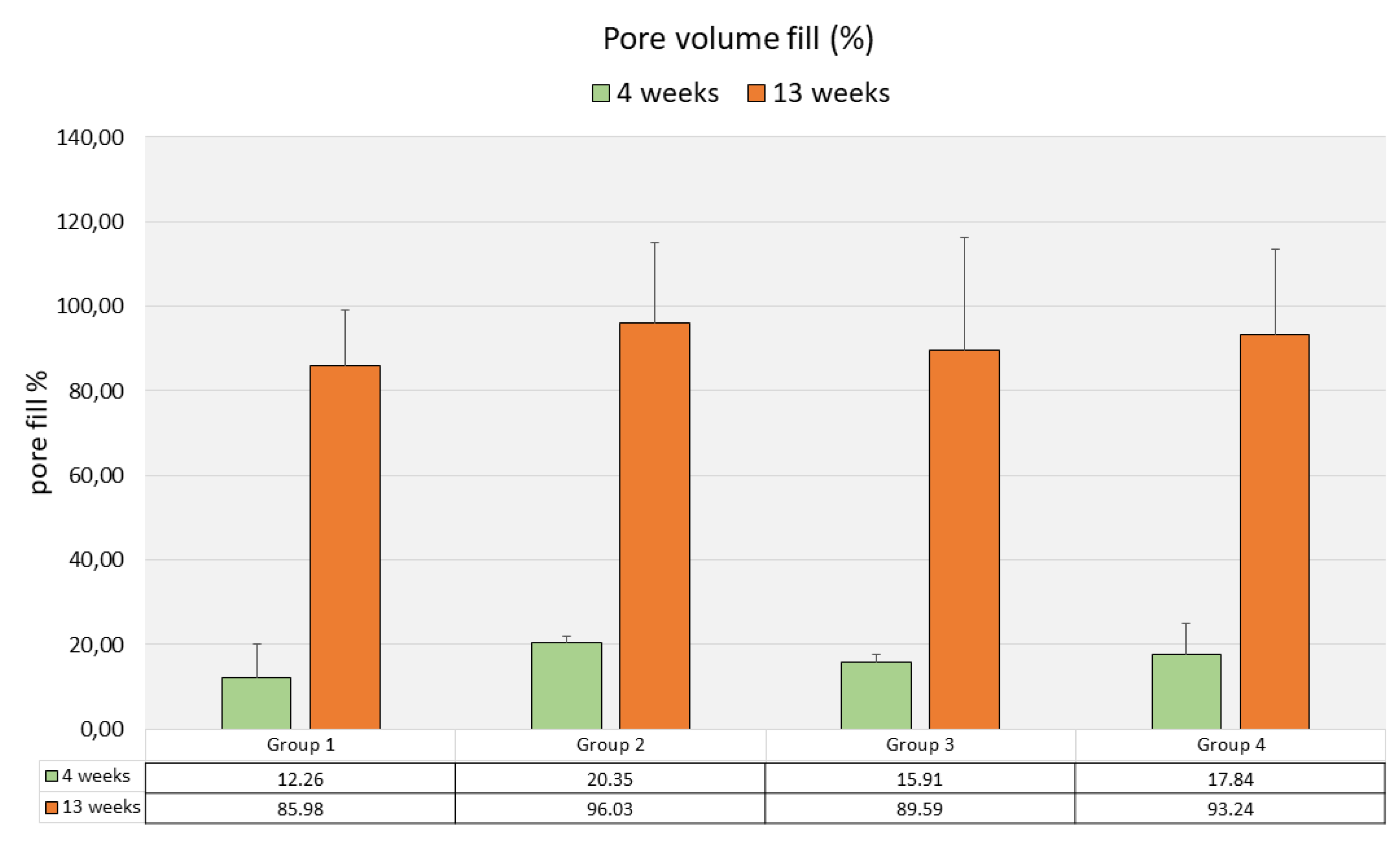

Mean pore volume fill as assessed by µCT varied between 12.25% (SD 9.71) in Group1 and 20.35% (SD 1.92) in Group 2, without significant differences (p=0.390) between the four groups (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Pore volume fill (µCT, %, mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

Figure 10.

Pore volume fill (µCT, %, mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

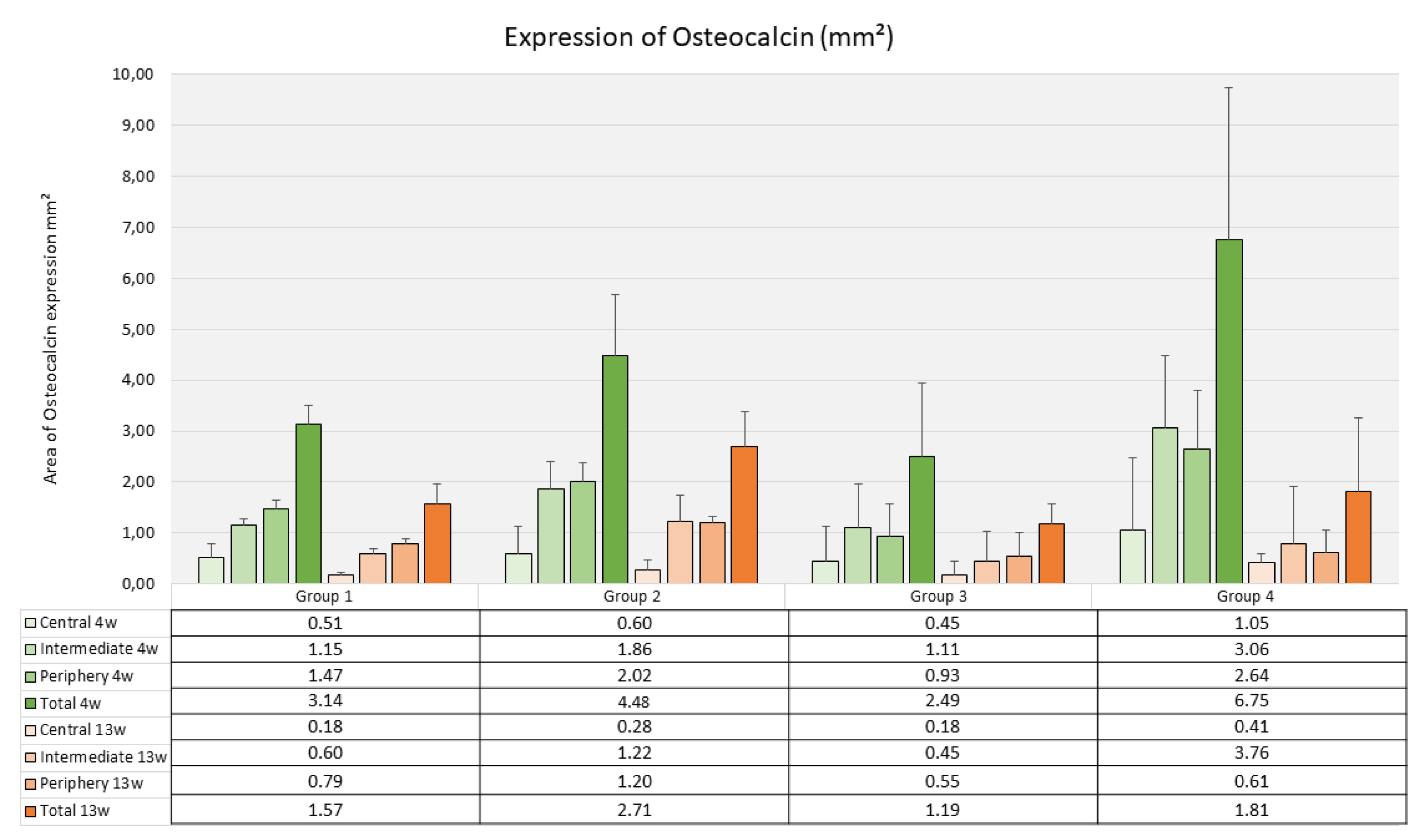

The average level of osteocalcin expression as assessed through immunohistochemical staining ranged between 2.49 mm² (SD 1.41) for Group 3 and 4.48 mm² (SD 1.73) for Group 2 without significant differences between the groups (p=0.126) (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Osteocalcin expression inside the scaffolds (Histomorphometry, mm², mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

Figure 11.

Osteocalcin expression inside the scaffolds (Histomorphometry, mm², mean values & standard deviations, n=3)).

Bone formation after 13 weeks as assessed by histomorphometry had significantly increased in all scaffold groups (p-values ranging between 0.004 and 0.0.028). The highest amount of newly formed bone was found in Group 4 with a mean value of 14.79 mm² (SD 5.06) and the lowest was registered in Group 1 (12.86 mm², SD 4.50) (Fig. 9). Again, differences in mean values between the groups were not significant (p=0.361). There was a significant decrease in the amount of newly formed bone from the periphery towards the center of the scaffolds (p-values ranging from <0.001, to 0.002 for the four types of scaffolds). Bone formation in the individual zones was not significantly different between the four groups.

The mean pore volume fill had significantly increased from 4 weeks to 13 weeks (p-values ranging from 0.001 to 0.009) and varied between 86.0% (SD 16.24) in Group 1 and 96.0% (SD 23.36) in Group Differences in mean pore volume fill between the different scaffold types were not significant (p=0.479) (Fig. 10).

The mean area with positive staining for osteocalcin after 4 weeks ranged between 1.18 mm² for Group 3 (SD 0.53) and 2.71 mm² (SD 1.39) for GroupDifferences between the groups were not significant (p=0.543). The decrease from 4 weeks to 13 weeks was not significant as well in the different scaffold types (p-values in the four groups varied between 0.052 and 0.120) (Fig. 11).

4. Discussion

The present study has evaluated the in vivo performance of a resorbable PLA- bioceramic scaffold that has been produced through selective laser sintering (SLS). Most of the resorbable PLA-bioceramic scaffolds currently under research have been produced through extrusion based techniques, where the heated polymer material is extruded through a computer driven nozzle such as fused deposition modelling (FDM) or other types of 3D-printing resulting in three-dimensional structure of rectangular struts with a smooth surface (Alonso-Fernandez et al. 2023). The characteristics of PLA scaffolds produced through SLS from a powder bed are quite different depending on the type of PLA polymer and the laser energy employed. In vitro studies on SLS using poly-lactid-acid powder in conjunction with CaCO3 particles have shown (Gayer et al. 2018 & 2019) that poly-(L-lactide) is more suitable than poly-(DL-lactide) to produce open porous scaffolds due to superior sintering characteristics at the energy level used for the laser sintering process. Additionally, the scaffolds are characterized by a rough inner surface with a certain degree of microporosity due to incompletely melted powder grains resulting from the fact that the process temperature does not lead to complete melting of the material (Du et al. 2017, Sun et al. 2020). The microporosity in conjunction with bioceramic particles is considered to facilitate cell attachment and capillary growth (Li et al. 2024). These surface features reported in previous studies compare well to the SEM findings and histologic results of the present study showing unmelted polymer grains on the scaffold surface that became detached in vivo during the first weeks of implantation and accumulated at a certain distance to the inner scaffold surface where they became subject to multinuclear giant cell degradation. This degradation process obviously did not interfere with bone ingrowth as bone formation in many areas even occurred in direct contact with the PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP scaffold surface with mineralized tissue extending between the superficial polymer particles as shown in the 4-weeks micrographs. These findings have also been previously reported for bone ingrowth into polymer-bioceramic scaffolds (Li et al. 2023, poly-vinyl-acid / hydroxyapatite) but are different from the features of bone ingrowth into pure poly-lactic acid scaffolds where direct contact between newly formed bone and the scaffold surface has not been regularly observed (Schliephake et al. 2008, Gruber et al. 2009).

In the present study, bone ingrowth into the scaffolds appeared to originate from the surrounding bone as shown by the significant decrease in bone formation towards the center of the scaffold in comparison to the scaffold periphery that is in contact with the pristine bone. This osteoconductive pattern of bone formation was seen after 4 weeks and even after 13 weeks in all types of scaffolds indicating that bone regeneration in the central parts may not have been completed after that period. Immunohistochemical staining also had shown, that even after 13 months the soft tissue in contact with the scaffold surface had maintained a state of osteogenic differentiation, indicating that osteogenesis can be expected to continue. This raises the question whether the size of the defects was appropriate for a critical size defect and whether an empty control defect would have been required. The dimensions of cylindrical critical size bone defects reported in different skeletal sites of minipigs vary between 7.3 and 11 mm (Ribeiro et al. 2024, van Oirschot et al. 2022, Jungbluth et al 2013, Spies et al. 2010), indicating that the defect size chosen with 7 mm diameter in the current study could be considered as critical size defect. The rather high numbers of tibial fractures in the current experiment also suggests that an additional empty defect of this size would have been impossible to accommodate in the tibial metaphysis of the animals. As the approval of the veterinarian authority was limited to the use of one leg per animal, the omission of the control defect was the most preferable option considering the fact that the comparison of material characteristics was in focus of the experiment and the defect size compared well to the size of previously reported critical defects.

Quantitative assessment of bone ingrowth has shown that the amount of bone formed had significantly increased between 4 and 13 weeks in all four scaffold types. After 13 weeks, a high degree of pore volume fill was found ranging between 86 and 96% corresponding to a bone volume fraction inside the whole scaffold between 30.9 and 39.5%. This volume fraction compares well to the newly formed bone volume between 11,2 and 39.9 % reported for synthetic and block grafting materials in experimental applications in large animal models after up to 1 year (Tumedei et al. 2019). When SLS produced resorbable polymer-bioceramic scaffolds are considered, the results of the present study as well are very much comparable to those previously reported for poly-caprolactone-hydroxyapatite scaffolds (Du et al. 2017)

Comparison of bone formation between the different scaffold types at both intervals has shown that neither pore volume nor composition of the scaffolds had a significant effect on the amount of bone ingrowth. The same held true, when the three individual zones inside the scaffolds were considered, indicating that also the pattern of bone ingrowth was not affected by the differences neither in pore volume nor composition between the four scaffolds types. The variation in composition by the surface modification of CaCO3 particles with CaP has been intended to enhance the bioactivity of the sintered surface. This approach is based on observations that the integration of hydroxyapatite nano particles into polymer fiber scaffolds has shown to increase in vitro bone cell viability and activity as well as in vivo bone formation (Liu et al. 2022, Eldokmak et al. 2023, Suba Sri & Usha 2025). The micrographs in the present study have shown that the Calcium containing microparticles were evenly distributed across the polymer matrix of the scaffold. The quantitative results of bone formation inside the scaffolds as well as the micrographic features of the bone-to-scaffold contact suggest that with this type of particle presentation in the polymer matrix, the addition of CaP to the CaCO3 particles did not account for a difference in bone formation compared to the pure CaCO3 particles alone.

5. Conclusions

The present study has shown that resorbable SLS produced PLLA-CaCO3/ CaP with two different pore volumes and two different compositions allowed for bone ingrowth that was able to almost completely fill the provided pore volume after 13 weeks and was in contact with the scaffold walls. The differences in pore volume and in composition by the addition of CaP did not account for significant differences in bone formation inside the scaffolds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.K., C.R., H.S.; methodology: P.K., S.G., C.R., H.S.; material development: F.R., S.G., T.W., M.V., S.H., C.R.; scaffold production: F.R., S.G., T.W.; imaging software: C.D.; validation: H.S.; investigation: S.W., C.B., P.K., and T.G.; visualization: C.D., T.G., and H.S.; resources: H.S.; S.H., C.R., data curation: P.K., S.W., T.G.; writing—original draft preparation: H.S.; writing—review and editing: P.K., S.W., C.B., P.S., C.D., T.G., F.R., S.G., M.V., S.H., C.R., and H.S.; supervision: P.K. and H.S.; project administration: C.R. and H.S.; funding acquisition: H.S., C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Verena Reupke, Mrs. Ute Kant and Mrs. Sigrid Ahlborn for their valuable support in animal care (VR) and histologic preparation (UK & SA).

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (Patientenspezifischer resorbierbarer Knochenersatz, FKZ 49MF190039) provided through Innovent e.V.

References

- 1: Lindner M, Hoeges S, Meiners W, Wissenbach K, Smeets R, Telle R, Poprawe R, Fischer H. Manufacturing of individual biodegradable bone substitute implants using selective laser melting technique. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011 Jun 15;97(4):466-71. Epub 2011 Apr PMID: 21495168. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Fernández I, Haugen HJ, López-Peña M, González-Cantalapiedra A, Muñoz F. Use of 3D-printed polylactic acid/bioceramic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering in preclinical in vivo studies: A systematic review. Acta Biomater. 2023 Sep 15;168:1-21. Epub 2023 Jul PMID: 37454707. [CrossRef]

- Raeisdasteh Hokmabad V, Davaran S, Ramazani A, Salehi R. Design and fabrication of porous biodegradable scaffolds: a strategy for tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2017 Nov;28(16):1797-1825. Epub 2017 Jul PMID: 28707508. [CrossRef]

- Bose S, Ke D, Sahasrabudhe H, Bandyopadhyay A. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials. Prog Mater Sci. 2018 Apr;93:45-111. Epub 2017 Aug PMID: 31406390; PMCID. [CrossRef]

- 6690; 5. PMC6690629.

- Xia Y, Zhou P, Cheng X, Xie Y, Liang C, Li C, Xu S. Selective laser sintering fabrication of nano-hydroxyapatite/poly-ε-caprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:4197-213. Epub 2013 Nov PMID: 24204147; PMCID: PMC3818022. [CrossRef]

- Du Y, Liu H, Yang Q, Wang S, Wang J, Ma J, Noh I, Mikos AG, Zhang S. Selective laser sintering scaffold with hierarchical architecture and gradient composition for osteochondral repair in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2017 Aug;137:37-48. Epub 2017 May PMID: 28528301; PMCID: PMC5544967. [CrossRef]

- Sun Z, Wu F, Gao H, Cui K, Xian M, Zhong J, Tian Y, Fan S, Wu G. A Dexamethasone-Eluting Porous Scaffold for Bone Regeneration Fabricated by Selective Laser Sintering. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020 Dec 21;3(12):8739-8747. Epub 2020 Nov PMID: 35019645. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Peng Z, Lv Q, Li L, Zhang C, Pang L, Zhang C, Li Y, Chen Y, Tang X. SLS 3D Printing To Fabricate Poly(vinyl alcohol)/Hydroxyapatite Bioactive Composite Porous Scaffolds and Their Bone Defect Repair Property. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023 Dec 11;9(12):6734-6744. Epub 2023 Nov PMID: 37939039. [CrossRef]

- Ali SA, Zhong SP, Doherty PJ, Williams DF. Mechanisms of polymer degradation in implantable devices. I. Poly(caprolactone). Biomaterials. 1993 Jul;14(9):648-56. PMID: 8399961. [CrossRef]

- Hutmacher D, Hürzeler MB, Schliephake H. A review of material properties of.

- 12. biodegradable and bioresorbable polymers and devices for GTR and GBR.

- applications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996 Sep-Oct;11(5):667-PMID:.

- 8908867.

- Pihlajamäki H, Böstman O, Tynninen O, Laitinen O. Long-term tissue response to bioabsorbable poly-L-lactide and metallic screws: an experimental study. Bone. 2006 Oct;39(4):932-7. Epub 2006 Jun PMID: 16750438. [CrossRef]

- Pihlajamäki HK, Salminen ST, Tynninen O, Böstman OM, Laitinen O. Tissue restoration after implantation of polyglycolide, polydioxanone, polylevolactide, and metallic pins in cortical bone: an experimental study in rabbits. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010 Jul;87(1):90-8. Epub 2010 May PMID: 20495791; PMCID: PMC2887933. [CrossRef]

- Nonhoff M, Puetzler J, Hasselmann J, Fobker M, Gosheger G, Schulze M. The Potential for Foreign Body Reaction of Implanted Poly-L-Lactic Acid: A Systematic Review. Polymers (Basel). 2024 Mar 14;16(6):817. PMID: 38543422; PMCID: PMC10974195. [CrossRef]

- Schiller C, Rasche C, Wehmöller M, Beckmann F, Eufinger H, Epple M, Weihe S. Geometrically structured implants for cranial reconstruction made of biodegradable polyesters and calcium phosphate/calcium carbonate. Biomaterials. 2004 Mar-Apr;25(7-8):1239-47. PMID: 14643598. [CrossRef]

- Kawai H, Sukegawa S, Nakano K, Takabatake K, Ono S, Nagatsuka H, Furuki Y. Biological Effects of Bioresorbable Materials in Alveolar Ridge Augmentation: Comparison of Early and Slow Resorbing Osteosynthesis Materials. Materials (Basel). 2021 Jun 14;14(12):3286. PMID: 34198634; PMCID: PMC8232082.. [CrossRef]

- Akagi H, Iwata M, Ichinohe T, Amimoto H, Hayashi Y, Kannno N, Ochi H, Fujita Y, Harada Y, Tagawa M, Hara Y. Hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide acid screws have better biocompatibility and femoral burr hole closure than does poly-L-lactide acid alone. J Biomater Appl. 2014 Feb;28(6):954-62. Epub 2013 May PMID: 23680818. [CrossRef]

- 21. Gayer C, Ritter J, Bullemer M, Grom S, Jauer L, Meiners W, Pfister A.

- Reinauer F, Vučak M, Wissenbach K, Fischer H, Poprawe R, Schleifenbaum JH. Development of a solvent-free polylactide/calcium carbonate composite for selective laser sintering of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019 Aug;101:660-673. Epub 2019 Mar PMID: 31029360. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A. I., Richards, R. G., Milz, S., Schneider, E., earce, S.G. (2007). Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: A review. European Cells & Materials, 13, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Gruber RM, Krohn S, Mauth C, Dard M, Molenberg A, Lange K, Perske C, Schliephake H. Mandibular reconstruction using a calcium phosphate/polyethylene glycol hydrogel carrier with BMP-J Clin Periodontol. 2014 Aug;41(8):820-6.

- Mead R. The design of experiments. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. 620 p.

- 2011; T10, 26. Festing MFW (2011) How to reduce the number of animals used in research by improving experimental design and statistics ANZCCART Fact Sheet T10, 1-11.

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012 Apr;20(4):256-60. PMID: 22424462. [CrossRef]

- 28. Gayer C, Ritter J, Bullemer M, Grom S, Jauer L, Meiners W, Pfister A,.

- Reinauer F, Vučak M, Wissenbach K, Fischer H, Poprawe R, Schleifenbaum JH.

- 30. Development of a solvent-free polylactide/calcium carbonate composite for.

- selective laser sintering of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C.

- Mater Biol Appl. 2019 Aug;101:660-673. Epub. [CrossRef]

- 2019; 33. 2019 Mar PMID: 31029360. [PubMed]

- Ribeiro M, Grotheer VC, Nicolini LF, Latz D, Pishnamaz M, Greven J, Taday R, Wergen NM, Hildebrand F, Windolf J, Jungbluth P. Biomechanical validation of a tibial critical-size defect model in minipigs. Clin Biomech (Bristol). 2024 Dec;120:106336. Epub 2024 Sep PMID: 39276502. [CrossRef]

- 25. van Oirschot BAJA, Geven EJW, Mikos AG, van den Beucken JJJP, Jansen JA. A Mini-Pig Mandibular Defect Model for Evaluation of Craniomaxillofacial Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2022 May;28(5):193-201. PMID: 35262400; PMCID: PMC9271328. [CrossRef]

- Jungbluth P, Hakimi AR, Grassmann JP, Schneppendahl J, Betsch M, Kröpil P, Thelen S, Sager M, Herten M, Wild M, Windolf J, Hakimi M. The early phase influence of bone marrow concentrate on metaphyseal bone healing. Injury. 2013 Oct;44(10):1285-94. Epub 2013 May PMID: 23684350. [CrossRef]

- Spies CK, Schnürer S, Gotterbarm T, Breusch SJ. Efficacy of Bone Source™ and Cementek™ in comparison with Endobon™ in critical size metaphyseal defects, using a minipig model. J Appl Biomater Biomech. 2010 Sep-Dec;8(3):175-PMID: 21337309.

- Tumedei M, Savadori P, Del Fabbro M. Synthetic Blocks for Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 28;20(17):4221. PMID: 31466409; PMCID: PMC6747264. [CrossRef]

- Eldokmak MM, Essawy MM, Abdelkader S, Abolgheit S. Bioinspired poly- dopamine/nano-hydroxyapatite: an upgrading biocompatible coat for 3D-printed polylactic acid scaffold for bone regeneration. Odontology. 2025 Jan;113(1):89-100. Epub 2024 May PMID: 38771492. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Li D, Chen X, Jiang L. Biomimetic cuttlebone polyvinyl alcohol/carbon nanotubes/hydroxyapatite aerogel scaffolds enhanced bone regeneration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022 Feb;210:112221. Epub 2021 Nov PMID: 34838414. [CrossRef]

- Suba Sri M, Usha R. An insightful overview on osteogenic potential of nano hydroxyapatite for bone regeneration. Cell Tissue Bank. 2025 Mar 4;26(2):13. PMID: 40038123. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).