1. Introduction

Bone engineering aims to replace damaged bone tissue with materials that seamlessly integrate with the host. A successful bone substitute must provide temporary mechanical support at the defect spot and promote bone regeneration until normal biomechanical function is restored [

1]. Substitute material must have the required compressive strength, toughness, and porosity resembling that of natural bone (>50% porosity and >100 mm average pore size) [

2]. It also needs to be osteoconductive (to facilitate the supply of nutritional agents through its pores), osteoinductive (to stimulate new bone formation) and osteointegrative (to incorporate into the surrounding bone structures) [

3]. Bone substitutes should have a micro-nanometer surface structure crucial for directing cell adhesion and cell proliferation. Bone substitute production aims to imitate the natural bone remodeling processes, so a particular challenge in bone engineering is balancing the resorption rate of a bone substitute with the growth of new bone tissue [

2,

3,

4]. Critically sized bone defects pose a significant challenge in clinical settings, particularly in terms of care and therapy complexity. For this reason, modern medicine has embraced the three-dimensional (3D) printing of bone substitutes with highly precise shapes and sizes tailored to each patient’s specific needs [

5].

Nanostructured hydroxyapatite (nHAP) is a widely investigated biomaterial known for its outstanding biocompatibility, and potential to directly stimulate new bone formation, with absence of toxicity and inflammation. In combination with polymers, it represents an excellent candidate as a bone substitute [

6,

7,

8]. One of the latest generations of materials based on nHAP and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), named ALBO-OS, has shown a great potential as bone tissue substitute due to its excellent mechanical properties and ideal solubility, demonstrating complete rabbit calvaria defect healing in 12 weeks [

9,

10].

Many published papers on bone regeneration [

3,

11,

12] have demonstrated successful large bone defect reconstruction, while a single study offers details on bone tissue reconstruction, involving the removal of a full diameter bone section, including both the proximal and distal parts of the bone through cutting [

13]. To achieve adequate bone healing, autologous stem cells were seeded onto the bone substitute surface prior to implantation, along with bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) added to mesenchymal stem cells to act as an osteoinductor [

13].

A significant focus in the development of bone substitutes is to create materials that can promote bone regeneration with practicable, translatable approaches [

14], while cartilage regeneration demands some modulation of osteoinductive materials. It is well known that hydroxyethyl cellulose improves the cell viability, proliferation and differentiation capacity, showing high potential for cartilage repair [

15]. Alongside, sodium hyaluronate promotes cell adhesion and proliferation, regulation of inflammation, and enhances cartilage regeneration [

16], while chondroitin sulfate, as the main component of cartilage extracellular matrix, keeps cartilage healthy by absorbing fluids (particularly water) into the connective tissue. It may also block enzymes that break down cartilage, and it provides the building blocks for the body to produce new cartilage [

17].

For dual regeneration of bone and cartilage the gel based on nHAP enriched with hydroxyethyl cellulose, sodium hyaluronate, and chondroitin sulfate (nHAP gel) could provide wanted effect in combination with nHAP bone substitute. Thus, the study aim was to 1) investigate in vitro biocompatibility, osteogenic and chondrogenic potential of newly synthesized nHAP gel on SCAPs, 2) reconstruct part of the joint in a rabbit model (lateral condyle of the femur), 3) and regenerate combined bone and cartilage defects using a 3D-printed bone substitute made of a novel bioresorbable and osteoinductive nHAP material named ALBO-OS, combined with nHAP gel.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Synthesis

Calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) powder and ammonium hydrogen phosphate ((NH4)2HPO4) (Merck & CO., INC., Kenilworth, NJ, USA) were used for the hydrothermal synthesis of nano hydroxyapatite (nHAP). Precursor solutions were prepared as a combination of two mixtures: (i) 500 mL of 3.02 cmol aqueous solution of Ca(OH)2 (mixture 1) and 500 mL of 2.32 cmol aqueous solution of (NH4)2HPO4 (mixture 2), and mixture II was added dropwise into mixture I, under simultaneous vigorous mixing on a magnetic stirrer. Finally, polyethylene vinyl acetate (PEVA)/ polyethylene vinyl versatate (PEVV) was added as surface active substance to the obtained common solution. Then, this solution was subjected to hydrothermal treatment at the temperature of 120°C, during 2h to obtain nHAP particles. Finally, the solution containing obtained nHAP was filtered through a 200 nm pore filter, washed with deionized water and dried at 105°C during 4 h. The PLGA coating was obtained by pouring a chloroform solution of PLGA over the nHAP particles, which left a thin PLGA film on the particles surface after solvent evaporation. Obtained bone substitute, labeled as ALBO-OS, was further used for fabrication of bone graft by using 3D printing technology according to the corresponding 3D model (this procedure is described in detail in section 2.2). This graft was responsible for sub-cartilage bone regeneration.

After fabrication of 3D graft which was responsible for regeneration of the sub-cartilage bone, a very dense gel, predominantly based on nHAP (94%) (nHAP gel) was used for cartilage regeneration. For the production of nHAP gel, the nHAP powder, obtained as described above, was mixed with sodium hexametaphosphate (SHMP) as surface active substance, during which the SHMP form a thin coating on the surface of the nHAP particles, and thus preventing their agglomeration. In the next step, hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), sodium hyaluronate (SH), and chondroitin sulfate (CH) were added to so processed nHAP. Ratios of the components (in mass %) were SHMP: HEC: SH: CH: nHAP= 1: 2: 1.5: 1.5: 94. After that, the given mixture was processed in planetary mill with ceramic balls and ceramic lining was used. Ratio between gel mixture and balls with a diameter of 1 cm, was 1:10. A rotational speed of 250 rpm resulted in an acceleration of about 6.5 g (d is gravitation acceleration), while milling time was 39 min. After milling small amount of water and glycerin were added dropwise, to obtain very dense complex gel, which will be applied onto porous surface of the previously printed construct.

2.2. Three-Dimensional (3D) Modeling and Printing of Bone and Cartilage Grafts

2.2.1. CBCT Data to Printable 3D Model Transformation

A preoperative cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan of the rabbit’s ulna was obtained via the Scanora 3D scanner (Soredex, Tuusula, Finland), while the animal was anesthetized (as described in

Section 4.), using following parameters: 13mA, 90kV, and a voxel resolution of 0.2mm. After scanning, a Standard Tessellation Language (STL) file of target bones and cartilage tissue was generated from the CT data using Slicer software version 4.3.1 and Blender (Autodesc Inc., USA) software. Thus obtained STL files were imported into Autodesk 3D Max 2010 (Autodesc Inc., USA).

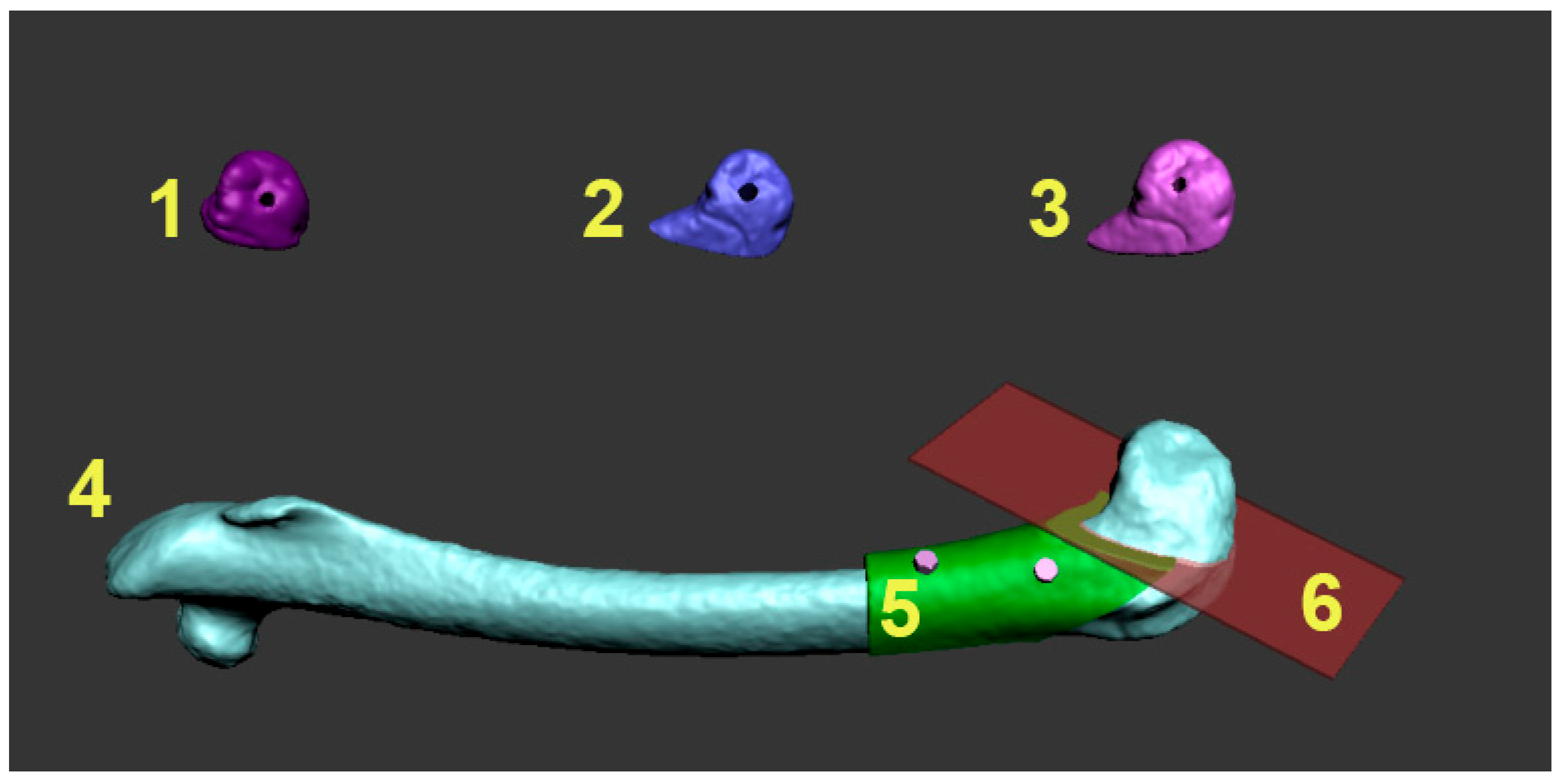

To prepare the grafts for the experiment, the diagonal resection was planned on the distal end of the rabbit’s femur to dissect the lateral condyle, as visualized in

Figure 1. Based on surface 3D model of the bone, a graft was modeled layer by layer using a maze forming algorithm.

2.2.2. Modeling and 3D printing of the constructs with the desired porosity

To achieve the desired porosity and pore interconnectivity in the custom bone and cartilage replacement constructs, we applied the randomized Kruskal’s maze generating algorithm (RKA) using Piton software. The RKA algorithm generated a 15 × 15 mm planar maze in the x and z axes, allowing control over porosity and “bone” volume by adjusting the ratio of maze wall thickness to path width. Walls were set at 225 μm to ensure pore interconnectivity by removing enclosed cells.

Then the 2D maze structure was extruded by 225 μm along the Z-axis, creating a 3D object. This 3D maze generation was repeated and stacked along the Z-axis until it reached the bone construct’s dimensions (X—15 mm, Y—15 mm, Z—25 mm), providing random vertical interconnectivity. This produced a 3D bone construct with 50% porosity and trabecular thickness of 225 μm, where maze walls formed trabeculae and paths represented voids.

The 3D maze and bone and cartilage construct models were imported into Autodesk 3D Max, where we merged them with a Boolean union operation. The model was then prepared in Slice3R software with settings of a 0.2 mm layer height, 100% infill, 10 mm/s print speed, zero shell thickness, and no support material. For 3D printing, Pronterface software was used, with paste made of ALBO-OS particles less than 300 µm and PLGA as a support material. The process of printing the construct was set so that the concentration of ALBO-OS particles gradually increases from 20 to 80% from the construct periphery towards the center, with the maximum concentration of PLGA on the construct surface. For the rabbit`s femoral condyle graft, prefabricated nHAP gel (described in section 2.1.) was rubbed onto porous surface of the printed construct.

Following the printing of 3D bone grafts with precisely matching the shape of desired defect, the bone models underwent UV sterilization for 12 hours.

2.3. In Vitro Study on SCAPs

2.3.1. Mitochondrial Activity

In vitro experiments on stem cells were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade (number: 36/8). Mitochondrial activity assay was performed following ISO standard 10993-5. Experimental samples were prepared as gel emulsions in growth medium (1%, 0.5%, 0.25%, 0.125%). Stem cells of the apical papilla (SCAPs) isolated and characterized as previously described [

18], were seeded in 96-well plate, 5 000 cells/well. The next day serial solutions of nHAP gel material were added in the wells. As a control, cells cultured in growth medium were used. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO

2 for 24 h after which the mitochondrial activity of the materials was evaluated through the (3-([4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl- tetetrazolium bromide (MTT) cell metabolic activity assay (Sigma-Aldrich). To quantify cell metabolic activity, growth medium was removed, and freshly prepared growth medium containing 5 mg/mL MTT was added. The plates with cells were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 4 h, after which the medium was removed and 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the wells. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm in microplate reader (RT-2100c, Rayto, China).

2.3.2. Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Differentiation

SCAPs were seeded in 96-well plates in concentration 10 000 cells/well, in growth medium. The next day, as cells reached 80% confluence, growth medium was discarded, and materials’ solution in concentration 0.125% was added to the corresponding wells. Materials were dissolved in osteogenic (StemMACS™ OsteoDiff Medium, Miltenyi Biotec) or chondrogenic medium (StemMACS™ ChondroDiff Medium, Miltenyi Biotec). As a control, cells cultured only in osteogenic or chondrogenic medium were used. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7 days, after which the cells were fixed with 4% neutral formalin buffer for 15 min., and stained with 2% Alizarin-Red Staining solution (ARS, Sigma-Aldrich), or with 1% in 3% acetic acid Alcian Blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich). ARS and Alcian Blue bounds to cultures were extracted by incubation with 250 μL of 1% hydrochloric acid in 70% ethanol for 20 min. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm in a microplate reader (RT-2100c, Rayto, China).

2.4. In Vivo Customized Bone Model Implantation in Rabbit Joint

The experiment included three adult New Zealand white rabbits, 4-month-old, weighing approximately 3.2–4.1 kg, following the EU guidelines (86/609/EEC) regarding the use of laboratory animals in line with the principles of good laboratory practice and the principles of care and use of laboratory animals (NIH publication 85–23, revised in 1985). The experimental research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Belgrade (number: 323-07-06340/2019-05/1). The first step involved intramuscular premedication (combination of Ketamidor (ketamine hydrochloride) 10%, Richter Pharma Ag, Austria, 35 mg/kg, and xylazine (Xylased) 2%, Bioveta, Czech Republic, 5 mg/kg) and CBCT scanning of all three laboratory animals (left ulna) to obtain images for designing customized bone models. Butorphanol (Richter Pharma Ag, Austria) was administered intramuscularly at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg for analgesia. Under local anesthesia (Lidocaine-chloride 2%, Galenika a.d. Serbia), a linear skin incision of 5.5 cm was made in the left joint region of all rabbits. The joint was revealed by gently lifting the overlying soft tissues. After removing a predetermined section of lateral femur condyle, 3D bone grafts were implanted into the defect site without using any stem cells or growth factors. Namely, the defect was created at a predetermined distance 1 cm from the top of lateral femur condyle to ensure accurate placement of the 3D-printed graft. A segmental osteotomy of lateral femur condyle was performed in all three rabbits. The 3D printed graft with applied nHAP gel on its surface was placed at the site of the osteotomy defect and fixed with a titanium screw (KLS MARTIN, Florida, USA), 12 mm long and 1 mm in diameter, through the graft hole that was previously precisely designed.

Following the placement of the 3D bone graft, mediolateral X-rays were acquired using a ZooMax White DR system (Control-X Medical, Ltd.) to verify the accuracy of its positioning. The imaging parameters were: 47 kV, 6.4 mAs, and 70 cm focal-film distance. X-ray images were digitized using a CR 10-X (Agfa HealthCare NV, Mortsel, Belgium). The soft structures were repositioned, and the surgical wound was closed with simple sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon, 3-0). Postoperatively, the rabbits were kept in cages with unrestricted access to food and water. Air temperature in the vivarium was kept at 23 ± 3 °C, with the humidity of 55 ± 5%, and a 12/12 light–dark cycle. The rabbits showed no signs of discomfort or loss of appetite five days after surgery. The incision site and the surrounding skin were clean. The skin sutures were removed ten days postoperatively. Five consecutive days after the intervention, the rabbits received buprenorphine 0.1 mg/kg (twice a day) and oxytetracycline 20 mg/kg subcutaneously to control pain and infection. The rabbit grimace scale, a standardized behavioral coding system that shows facial expressions, was used to assess pain. The rabbits were sacrificed 12 weeks following the experimental procedure when both joints were explanted from all rabbits. The right joint served as a control, while the left joint with the implanted 3D bone graft was examined as the experimental one. The sampled material was fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin.

2.4.1. Histological and Histomorphometric Analysis

Bone tissue samples were prepared for histological analysis using standard light microscopy techniques, including fixation in 4% buffered formaldehyde, decalcification in formic acid, dehydration, and paraffin embedding. Longitudinal sections, 4μm thick, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical staining for osteocalcin and collagen (Picrosirius red) was also performed. Given the potential differences in regeneration efficiency between the cartilage and bone, all histological and histomorphometric parameters were evaluated in both tissues. Morphometric evaluation was performed using a final magnification of 400×. Two-dimensional photographs were taken using a digital camera (Leica DFC295, Germany). Histological analysis was performed using light microscopy (Leitz Laborlux S fluorescence microscope, Ernst Leitz Wetzlar GMBH, Germany). Histomorphometric analysis was performed using the software package Leica University Suite, version 4.3 (Leica Microsystems, Germany).

2.4.2. qPCR Analysis of Tissue Samples

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

Tissue samples (bone and cartilage) were minced (1 cm3 pieces), and total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The RNA concentration was measured using the microvolume spectrophotometer (BioSpec–nano Microvolume UV–Vis Spectrophotometer; Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA). Oligo d(T) primer and the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to synthesize cDNA from 2 µg of total RNA.

Gene Expression Analysis of Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Differentiation

Real–time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using the first strand cDNA, 0.2 μM forward and reverse primers, and the SensiFAST SYBR Hi–ROX Kit (Bioline, UK). The expression of the following markers was analyzed: bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4), runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), as osteogenic markers; and integral membrane protein 2A (ITM2A), forkhead box C1 (FOXC1), and SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9 (SOX9), as chondrogenic markers. The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference. Relative gene expression values were calculated using the 2

−ΔCt method [

19]. The sequences of all primers used in this study are given in

Table 1.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The software package GraphPad Prism version 9 was used for the analyses (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Independent sample T-test and paired T-test were performed in the present study, after checking the distribution normality by Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. The data is shown as the mean ± St Dev. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, *** P< 0.001, and **** P< 0.0001 denote statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Results on SCAPs Cells

3.1.1. Mitochondrial Activity

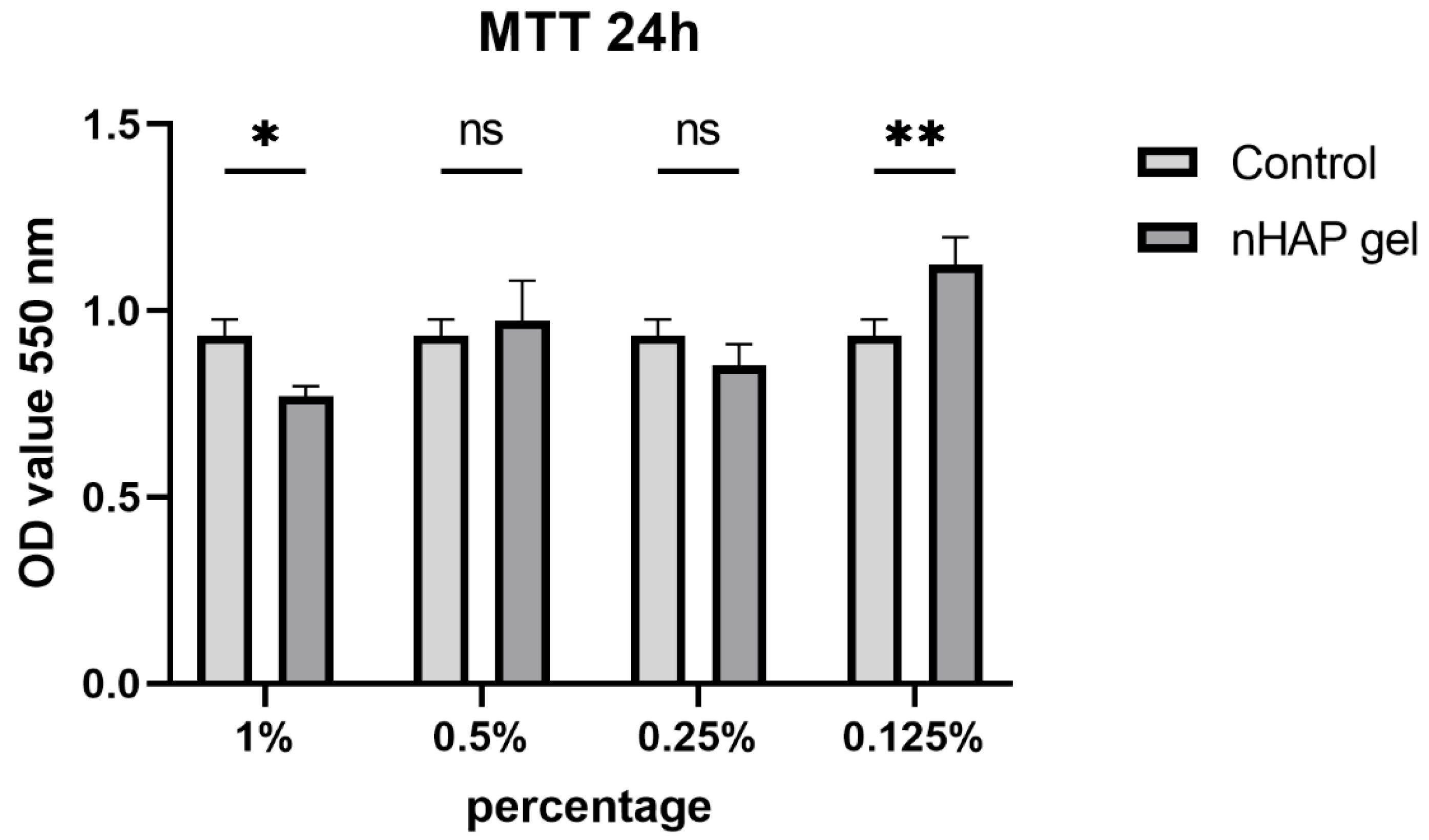

After 24 h, all concentrations stimulated cells to have mitochondrial activity over 70%, which is considered to be safety limit for materials in vitro. The cells treated with lowest investigated concentration, 0.125% of nHAP gel, had significantly higher mitochondrial activity (P<0.01), in comparison to the control (

Figure 2).

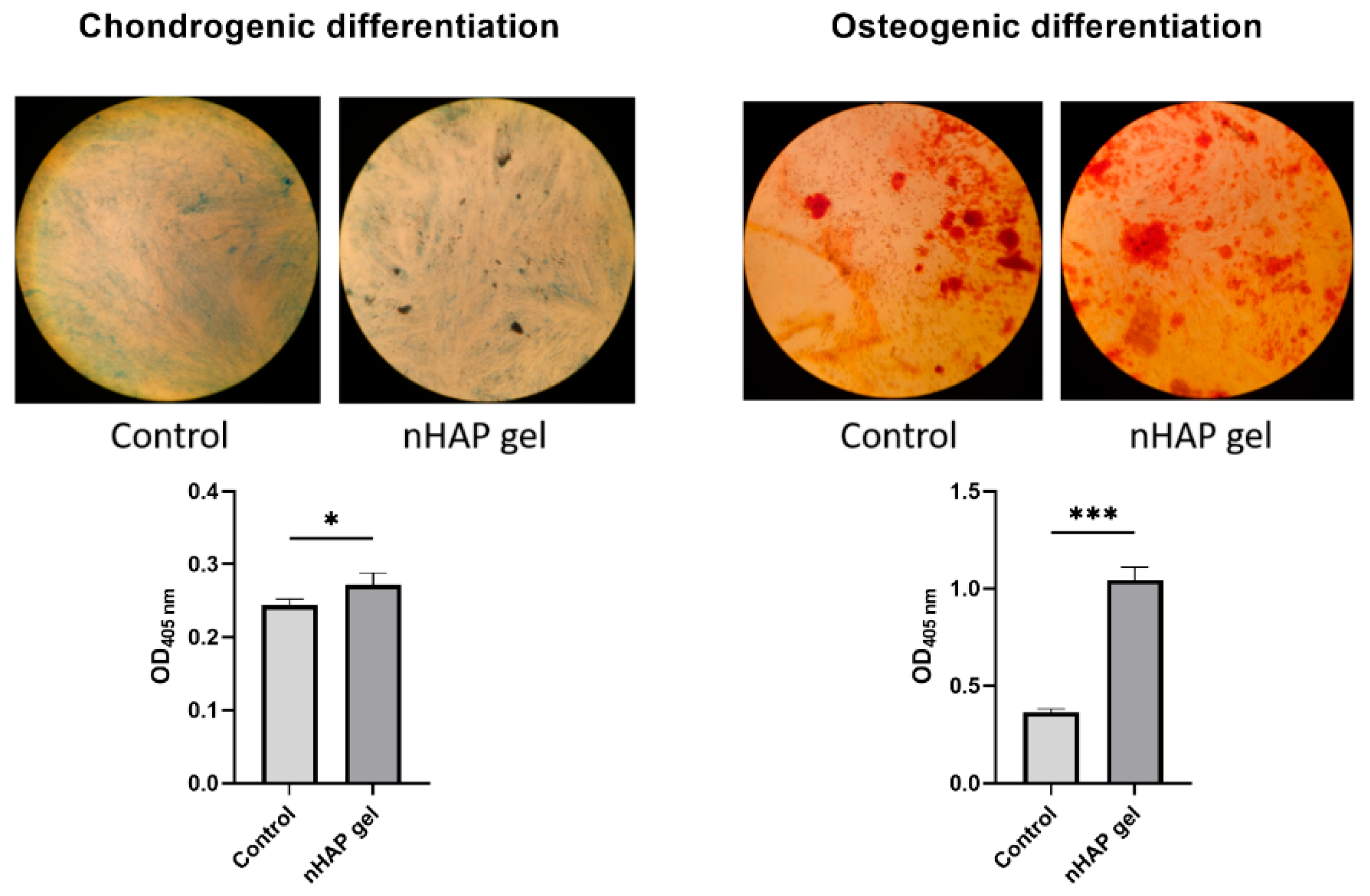

3.1.2. Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Differentiation

Since the concentration of 0.125% stimulated cells activity, it was chosen for further experiments. Cells were cultured in induction mediums for 7 days to observe potential of materials to accelerate differentiations in early stages of culturing. After 7 days of culturing cells in osteogenic medium, the group treated with nHAP gel significantly stimulated osteogenic differentiation, P<0.001, in comparison to the control. Mineralized globules were more prevalent and evenly distributed on the surface of the cells treated with nHAP gel. Also, nHAP gel significantly stimulated cells to chondrogenic differentiation, P<0.05, in comparison to the control (

Figure 3).

3.2. Stereological and Histological Findings

The implanted material proved to be very soluble for fixatives and brittle for cutting on a microtome, in the standard cytohistological procedure for analysis by light microscopy, which primarily influenced its detection. The material appeared torn and crumpled in histological sections, often only in fragments or pieces that remained closest to bone and cartilage cells (marked as “defect area” on micrographs).

However, in the micrographs a few remaining parts of the graft nanoparticles were observed, as well as the creation of new cartilage and bone tissue. Stereological (

Table 2) and histological (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13) analyses of longitudinal and transverse sections of rabbits’ joints revealed the presence of newly formed bone tissue and cartilage.

3.2.1. Hyaline cartilage in the rabbit joint region

Hyaline cartilage in the region of the implanted joint showed to be regenerated 12 weeks after implantation of 3D printed graft. Stereological (

Table 2) and histological (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) analysis of longitudinal and transverse sections of the rabbit joint showed the presence of newly formed cartilage.

Numerous new chondrocytes and significant layer of newly formed cartilage were observed in the hyaline cartilage of the lateral femur condyle. The presence of new chondrocytes strongly indicated the active reparation and advanced regeneration of the defect replaced with new 3D graft (

Table 2). A large number of fibroblasts and reticulocytes were observed, the cells active in tissue repair as mediators of wound healing (

Figure 4).

The architecture of the hyaline cartilage on the surface of the lateral femur condyle in control group (without 3D graft) showed more chondrocytes of larger dimensions (

Figure 5a) compared to the chondrocytes of the experimental group with implanted 3D graft. Chondrocytes of smaller dimensions, fewer in number, altered, irregular, flattened, spindle-shaped and balloon-shaped with wide lacunae (

Figure 5b) were observed in the experimental groups. The implanted material still remained in the form of small clusters around their edges of lacunae (

Figure 5, black arrows).

Chondrocytes in the cartilaginous tissues of the lateral femur condyle that was replaced with 3D graft did not have a regular linear and narrow arrangement as in the control group (

Figure 6a). They were scattered, irregular and disordered (

Figure 6b). The newly formed layer of cartilage which covered the femur defect was not thinner than in control group (

Figure 6). The NCR of chondrocytes with a 3D graft was high (

Table 2), which all together indicates the presence of a process of cartilage tissue regeneration and chondrogenesis near the graft.

Articular surface of the rabbits’ femur with a 3D graft (

Figure 7, defect area) was filled with newly formed irregular reticular cells and fibroblasts in cartilage tissue (

Figure 7, blue arrow). Immature chondrocytes and fibroblasts penetrated the pores of the 3D graft on the articular surfaces of the femur and thus proved the presence of chondrogenesis, the process of cartilage regeneration. The white arrow (

Figure 7a) shows regular cartilaginous tissue that is covered by newly formed cartilage on the upper side, while contact with bone tissue is visible on the lower side.

The longitudinal section of the joint with 3D graft showed the penetration of fibroblasts through the pores of the implanted graft (

Figure 7b). In the same image, young reticulocytes (yellow arrows) and chondrocytes (black arrow) were detected at the site of new cartilage formation and thus prove the presence of chondrogenesis.

3.2.2. Bone Tissue in the Rabbit Joint Defect Region (Sub-Cartilage Region)

During a 12-week healing period, there were no signs of necrosis, infection or bleeding. The bone tissue showed a good degree of regeneration and reparation of the defect filled with 3D graft (

Table 2). New osteocytes were numerous even though the young bone layer was thin.

The presence of cysts, necrosis, infiltration of blood cells, or immune response was not observed in the bone defect replaced by the 3D graft.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 represent longitudinal and cross-sectional micrographs of a femoral defect filled with a 3D graft. After 12 weeks, the connection between the damaged bone tissue and the implanted 3D graft was visible. No lymphocytes or cysts at the contact of bone and implanted material were observed (

Figure 9). Only fibroblasts with long cytoplasmic extensions that bind material to the bone were detected. Young osteocytes and fibroblasts were observed as mediators of osteogenesis.

Fragments of the implanted material were detected on the cross-sections of the lateral femoral condyle with implanted 3D graft. The presence of dark blue colored young osteocytes was also observed (

Figure 10).

The architecture of the bone tissue with implanted graft was changed, the osteocytes were fewer and have different shapes compared to the osteocytes in the control group (

Figure 11). NCR of osteocytes in bone with implanted grafts was elevated (

Table 2). This fact, as well as the presence of fibrocytes, indicated the acceptance processes of the implanted material by the bone tissue. Blood vessels in the bone tissue with an implanted graft had a higher volume density and diameter compared to the control group. (

Figure 11). Signs of angiogenesis in the bone tissue near the implanted graft indicated reparation and regeneration processes.

Detection and visualization of osteocytes was done by immunohistochemical staining of osteocalcin.

Figure 12a shows a longitudinal section of femur tissue without an implant, where excellent immunoreactivity to osteocalcin was observed compared to weaker reactivity to osteocalcin in

Figure 12b, where the graft was implanted. In

Figure 12b, the presence of osteocalcin was observed, which proved that the process of osteogenesis was present in the newly formed bone with implants.

Analysis revealed a small amount of mineralized bone tissue and a larger quantity of unmineralized bone, indicating ongoing osteogenesis. Additionally, a significant portion of the newly formed bone exhibited lamellar organization with vital osteocytes arranged concentrically around the Haversian canals. The presence of immature bone pointed to the active remodeling of bone tissue. The newly formed bone predominantly displayed trabecular architecture, with new bone marrow occupying the spaces between the trabeculae.

Visualization of collagen was done by immunohistochemical staining with Picrosirius red.

Figure 13 shows a very strong immunoreactivity to collagen in the control group, as well as in the experimental group. This indicated that osteogenesis was present in the newly formed bone with implanted graft, since collagen was present in the extracellular matrix of the newly formed bone tissue.

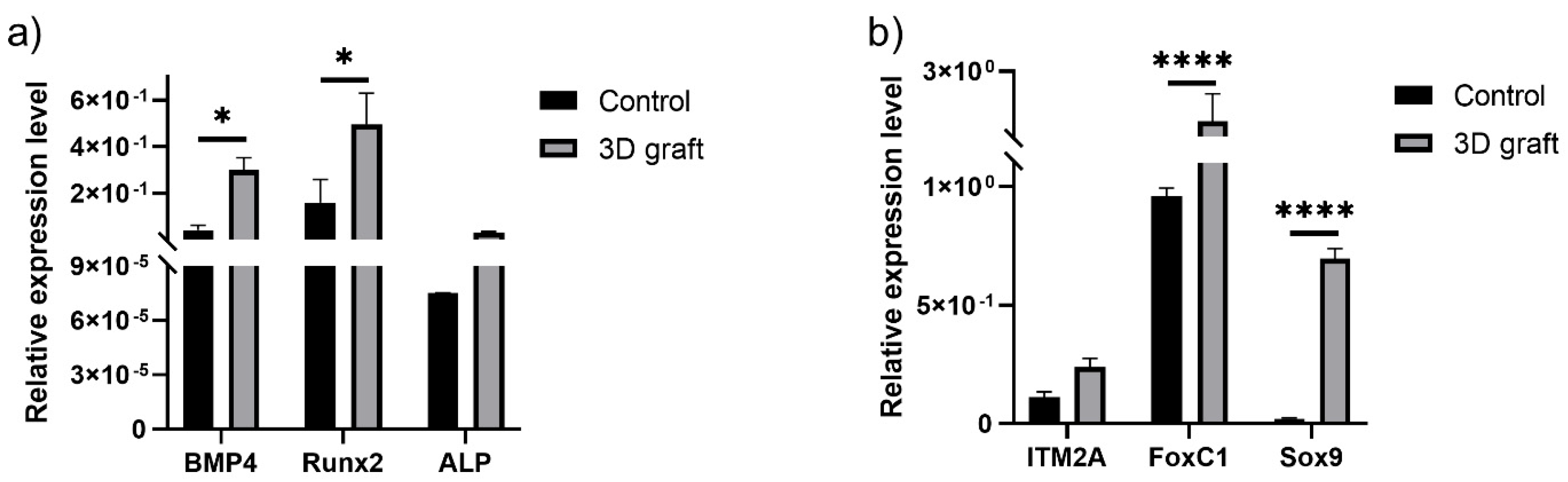

3.3. qPCR Analysis of Osteogenic and Chondrogenic Markers

Markers of osteogenic differentiation (BMP4, Runx2, ALP) were upregulated in the presence of material, compared to control (

Figure 14a). Expression levels of BMP4 and Runx2 were significantly higher in comparison to control (P<0.05). In the presence of 3D construct, markers of chondrogenic differentiation (ITM2A, FOXC1, SOX9) were upregulated, especially FOXC1 and SOX9 (P<0.0001) (

Figure 14b).

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrated that the 3D printed bone graft acts as a scaffold which imitates bone tissue structure and facilitates the migration, attachment, and reproduction of bone cells and the formation of new bone on the one hand, as well as the regeneration of cartilage on the other. Introduction of complex nHAP gel to established nHAP-PLGA construct enabled achieving of simultaneous regeneration of cartilage and bone, thus providing complex reconstruction of femur condyle.

After 12 weeks of healing, mature mineralized lamellar bone with Haversian osteons and blood vessels, as well as mature bone marrow, were observed at the periphery of the defect, indicating that almost complete peripheral bone defect regeneration was achieved. These results are consistent with those of Tang et al. [

20], which described almost complete bone regeneration using a new material containing bioactive glass with a growth factor recombinant human BMP-2. The newly formed bone tissue strongly suggests active osteogenesis and remodeling was ongoing 12 weeks post implantation. Runx2, as master osteogenic transcription factor that regulates the BMP4 pathway [

21] was upregulated as well as BMP4 in tissue samples where construct was implanted. Upregulation of osteogenic markers corresponds to osteoblast differentiation and active bone formation in the presence of 3D construct in the tissue. Considering the inflammatory cell count as the most important parameter of a bone substitute biocompatibility [

13], the results indicate significant biocompatibility of the 3D bone graft and complete bone regeneration.

The optimal degradation rate of the 3D bone graft, which corresponds to the new bone formation rate, is crucial for the osteoinductive potential of the bone. Also, many authors have made efforts to reconstruct large bone defects [

11,

12,

22,

23], which can be challenging compared to bone defects below the critical size due to difficult achieving ideal vascularization in the defect center. Significant progress in this field has been made by using stem cells on bone grafts before implantation—prefabricated bioreactor models that partially already contain new donor bone—with the addition of growth factors to the cell medium [

24,

25]. This has proven to be very suitable when the bone defect is surrounded by old bone on at least three sides, i.e., with intact bone integrity. This is also shown by studies in which bone was reconstructed by filling cylindrical bone defects in rat tibia [

26], rabbit calvaria [

10], or sheep femoral bone [

27]. Due to the complex tissue regeneration in bone reconstruction of large bone defects, it is often challenging to provide new bone growth in the center of a bone defect. This is due to lack of vascularization in center of the defect, and corresponding impaired oxygen delivery to the cells implanted in the construct [

28]. In previous pilot study, part of the rabbits’ joints was successfully reconstructed using the 3D printed graft based on nHAP, and its shape and dimensions fully matched the joint defect [

18]. The nHAP material that degrades at a similar rate as natural bone was used in study, allowing the surrounding bone to heal properly without fibrous tissue ingrowth. Previously to in vivo study, the absence of any adverse effect of the 3D-printed graft was validated on SCAPs in direct contact. Even more, it showed to be biocompatible, stimulating cell migration and osteodifferentiation [

18]. Detailed histological analysis revealed osteoblasts migration inside the 3D bone graft, while formation of blood vessels enabled new bone development nearby. Additionally, printed nHAP based graft provided adequate mechanical support and porosity, allowing for the necessary osteoconductivity. The combination of the graft’s materials, its mechanical properties, and its specific 3D structure seem to provide various physical and chemical signals as the main contribution to cell modulation and timing.

Research is still ongoing to identify materials that could effectively promote the regeneration of both bone and cartilage [

29,

30]. Our results showed that 12 weeks upon replacement of bone and cartilage with 3D construct of complex composition, regular cartilaginous tissue covered by newly formed cartilage on the one side could be observed, while on the other side contact with bone tissue was visible. Also, young chondrocytes and fibroblasts penetrated the pores of the 3D graft on the articular surfaces of the femur and thus proved the presence of chondrogenesis, the process of cartilage regeneration. Regeneration of cartilage was achieved due to complex gel based on nHAP enriched with hydroxyethyl cellulose, sodium hyaluronate, and chondroitin sulfate. Relative gene expression analysis of tissue corresponds to histological findings. Foxc1 and SOX9 were significantly upregulated in experimental group. SOX9 gene, a pivotal transcription factor, is expressed in cells from progenitor stage throughout differentiation, and in permanent chondrocytes. Its higher expression ensures successful chondrogenesis [

31]. It is suggested that SOX9 and Foxc1 cooperatively control endochondral ossification [

32], while ITM2A, cell surface chondrogenesis marker, if overexpressed could potentially inhibit chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [

33]. In our results, ITM2A expression was not significantly upregulated, but showed tendency to be higher expressed, in comparison to control. This balance of investigated genes, regulators of chondrogenesis, implies adequate development of new cartilage at the place of 3D construct.

Prior to the use of nHAP gel in animal model, preliminary in vitro study investigated its potential effect on stem cells. The gel affected mitochondrial activity of SCAPs, from 82.01±6.79 % as 1% solution, to 121.67±13.32% as 0.125% solution, in comparison to the control. Although higher concentrated hydrogel reduced slightly cell activity, it remained in high values. According to ISO 10993-5, percentages of cell viability above 70% are considered as non-cytotoxic [

34]. On the other hand, lowest concentration significantly stimulated cells activity (P<0.01) after 24h of incubation, indicating excellent biocompatibility in direct contact with stem cells. As for further experiments of bioactivity, material showed to significantly stimulate osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation when added in low concentration to the stem cells. Similar results for alkaline phosphatase cell production were observed when nHAP hybrid scaffolds enriched with chondroitin sulphate and hyaluronic acid were seeded with osteoblasts [

35]. Stimulation of dual differentiation could be considered as quite advanced feature of investigated gel that could promote its further use in osteochondral regeneration. Dual stimulation is considered to be provided due its diverse constitution, with well-established combination of nHAP for primary osteogenic differentiation, and chondroitin sulphate and hyaluronic acid which promote more chondrogenic differentiation [

36].

By achieving successful bone regeneration without using stem cells or growth factors, our findings highlight the potential of using engineered bone substitutes with desirable osteoinductive characteristics, as well as the possibility of cartilage tissue regeneration. While our preliminary results are promising, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. Future studies should confirm these results on a larger sample of laboratory animals and in larger animal models.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrated the promising potential of 3D printed bone grafts for the simultaneous regeneration of both bone and cartilage, offering a significant step forward in osteochondral tissue engineering. After 12 weeks of healing, we observed near-complete regeneration of bone tissue, with mature, mineralized bone forming at the periphery of the defect, and active osteogenesis in tissue. Furthermore, the incorporation of nHAP gel enhanced the regenerative capacity by promoting cartilage formation, as evidenced by the presence of newly formed cartilaginous tissue. While the results are encouraging, further research is needed to confirm these findings in larger animal models and to explore the long-term outcomes of this approach. Nonetheless, our study highlights the significant potential of 3D printed grafts in the regenerative medicine field, offering a viable strategy for addressing large, complex joint defects without the use of stem cells or growth factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.J. and S.Ž.; Material synthesis, B.P.; 3D modeling and printing, M.M.; In vitro study, D.M., M.L., and M.P.B.; In vivo implantation, V.B.; Histological and histomorphometric analysis, S.P., M.Ž. and S.Ž.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and D.M..; writing—review and editing, B.P and V.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (grant numbers 451-03-136/2025-03/ 200017 and 451-03-66/2024-03/ 200129).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of good laboratory practice and the principles of care and use of laboratory animals (NIH publication 85–23, revised in 1985). The experimental research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Belgrade (number: 323-07-06340/2019-05/1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D |

Three dimensional |

| nHAP |

Nano hydroxyapatite |

| PLGA |

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) |

| SCAPs |

Stem cells from apical papilla |

| ALBO-OS |

Name of material based on nHAP and PLGA |

| BMP2 |

Bone morphogenetic protein 2 |

| PEVA |

Polyethylene vinyl acetate |

| PEVV |

Polyethylene vinyl versatate |

| SHMP |

Sodium hexametaphosphate |

| HEC |

Hydroxyethyl cellulose |

| SH |

Sodium hyaluronate |

| CH |

Chondroitin sulfate |

| CBCT |

Cone beam computed tomography |

| STL |

Standard Tessellation Language |

| RKA |

Randomized Kruskal’s maze generating algorithm |

| MTT |

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetetrazolium bromide |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| qPCR |

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| BMP4 |

Bone morphogenic protein 4 |

| RUNX2 |

Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| ITM2A |

Integral membrane protein 2A |

| FOXc1 |

Forkhead box C1 |

| SOX9 |

SRY-box transcription factor 9 |

| GAPDH |

Gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| NCR |

Nucleocytoplasmic ratio |

| ALP |

Alkaline phosphatase |

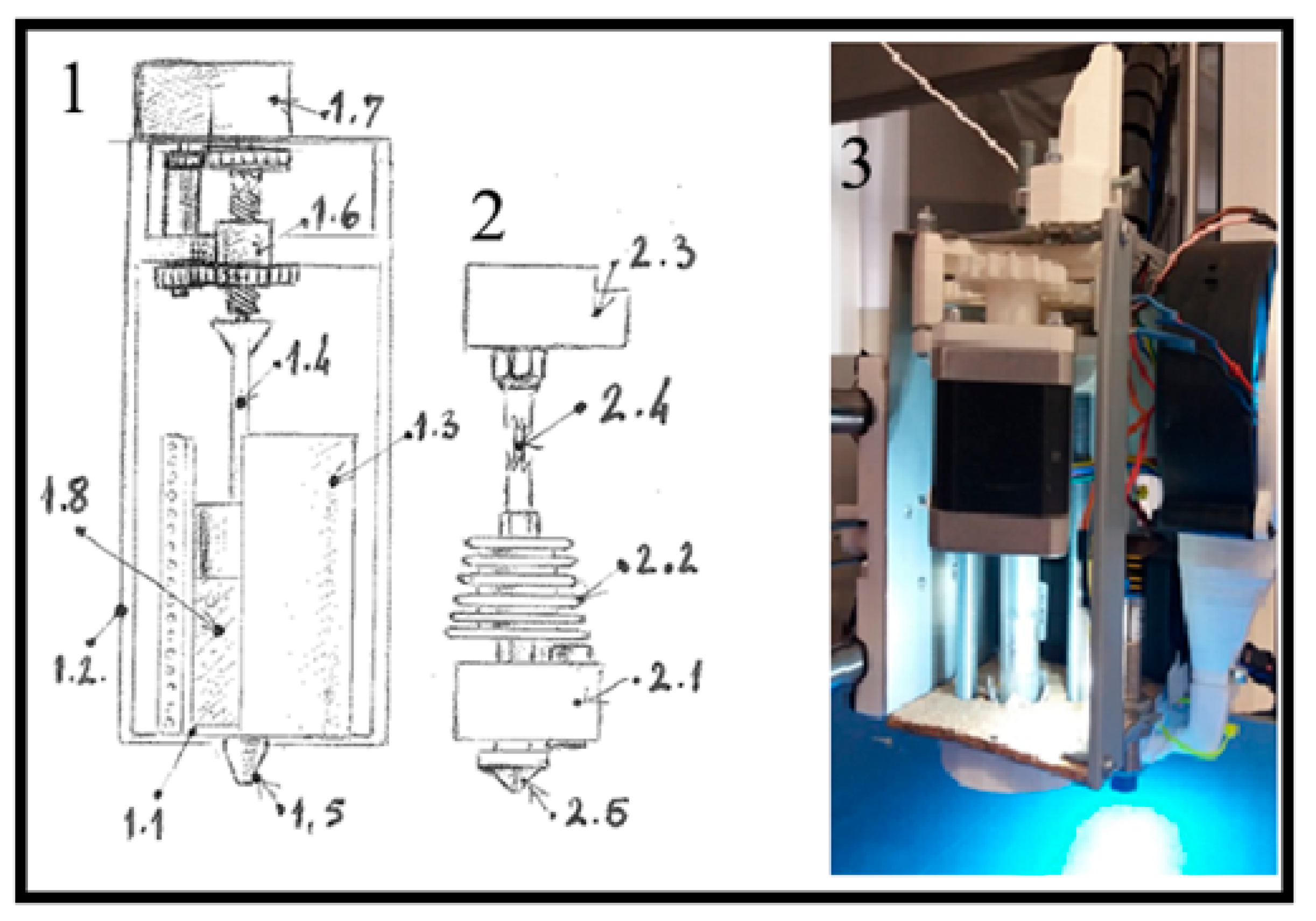

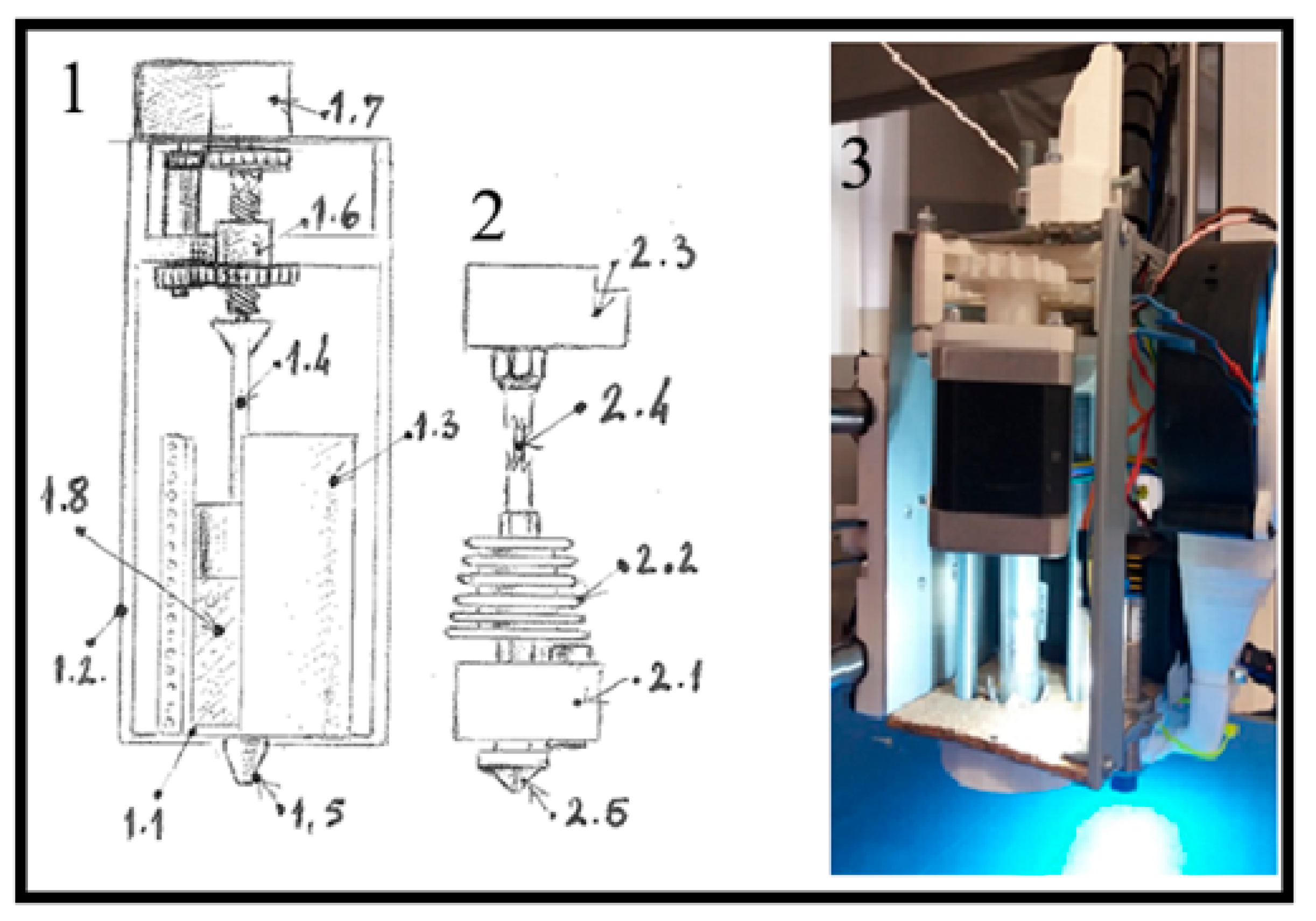

Custom 3D Printer Fabrication

To create a personalized bone constructs for planned rabbit’s femur defects, a custom 3D printer was developed at the Center of Bone Biology based on the Prusa I3 fused deposition modeling (FDM) printer (Prusa Research, Czech Republic). Key modifications included replacing the original frame with a robust, welded single-piece aluminum cube and upgrading the axis rails from 8mm to 20mm for added stability. A paste extruder for nHAP, designed as a syringe extruder with a NEMA 17 motor (6:1 gear ratio) and a 10cc steel-glass syringe, was added alongside a thermoplastic extruder and a 45-vat power air turbine on the X-axis. These upgrades allowed the printer to carry both extruders and the air turbine, minimizing vibrations during printing.

Figure A1.

Schematic representation of the extruder design in custom made laboratory 3D printer: from technical reasons, 3D printer was modified to include two extruders: 1—syringe extruder, 1.1—glass syringe, 1.2—external frame of the extruder 1, 1.3—electrical heater coil, 1.4 –metal piston of the syringe, 1.5—syringe nozzle (0,8mm in diameter), 1.6—gears of the piston drive, 1.7—piston drive motor with reduction, 1.8—HAP PLGA mixture, 2—PLGA extruder, 2.1—heater block of the PLGA extruder, 2.2—extruder cooler, 2.3—PLGA extruder motor drive with reduction, 2.4—PLGA filament 1.75mm in diameter, 2.5—PLGA extruder nozzle 0,4mm in diameter. 3—paste extruder attached to the head of the printer, with removed electrical heater coil, so the syringe with the metal piston can be visible. (Figure originates rom the PhD thesis: Micic M. [2023]. Influence of the choice of protocols on the accuracy of three-dimensional medical models, surgical guides and bone replacement. School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, National Repository of Dissertations in Serbia,

https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/bitstream/id/155980/Disertacija_14177.pdf).

Figure A1.

Schematic representation of the extruder design in custom made laboratory 3D printer: from technical reasons, 3D printer was modified to include two extruders: 1—syringe extruder, 1.1—glass syringe, 1.2—external frame of the extruder 1, 1.3—electrical heater coil, 1.4 –metal piston of the syringe, 1.5—syringe nozzle (0,8mm in diameter), 1.6—gears of the piston drive, 1.7—piston drive motor with reduction, 1.8—HAP PLGA mixture, 2—PLGA extruder, 2.1—heater block of the PLGA extruder, 2.2—extruder cooler, 2.3—PLGA extruder motor drive with reduction, 2.4—PLGA filament 1.75mm in diameter, 2.5—PLGA extruder nozzle 0,4mm in diameter. 3—paste extruder attached to the head of the printer, with removed electrical heater coil, so the syringe with the metal piston can be visible. (Figure originates rom the PhD thesis: Micic M. [2023]. Influence of the choice of protocols on the accuracy of three-dimensional medical models, surgical guides and bone replacement. School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, National Repository of Dissertations in Serbia,

https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/bitstream/id/155980/Disertacija_14177.pdf).

References

- Yang, C.; Wu, H.; Chen, S.; Kang, G. Three-Dimensional Bioglass-Collagen-Phosphatidylserine Scaffolds Designed with Functionally Graded Structure and Mechanical Features. Biomedical Engineering / Biomedizinische Technik 2018, 63, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Yu, X. Chitosan-Collagen/Organomontmorillonite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Front. Mater. Sci. 2015, 9, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shi, G.; Cui, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Guo, Y. Individual Construction of Freeform-Fabricated Polycaprolactone Scaffolds for Osteogenesis. Biomedical Engineering / Biomedizinische Technik 2017, 62, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, J. Effect of Steroidal Saponins-Loaded Nano-Bioglass/Phosphatidylserine/Collagen Bone Substitute on Bone Healing. Biomedical Engineering / Biomedizinische Technik 2017, 62, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-G.; Lee, K.-S.; Kang, Y.-J.; Hwang, J.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Park, Y.; Cho, Y.-S.; Lee, B.-K. Rabbit Calvarial Defect Model for Customized 3D-Printed Bone Grafts. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods 2018, 24, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiri, F.; Fatimi, A.; Magdalena Musuc, A.; Paiva Santos, A. C.; Paszkiewicz, S.; Igwe Idumah, C.; Singh, S.; Varma, R. S.; Berrada, M. Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHAp) Scaffolds for Bone Regeneration: Preparation, Characterization and Biological Applications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 95, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraš, S.; Trišić, D.; Mitrović Ajtić, O.; Prokić, B.; Drobne, D.; Živković, S.; Jokanović, V. Toxicological Profile of Nanostructured Bone Substitute Based on Hydroxyapatite and Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) after Subchronic Oral Exposure of Rats. Nanomaterials 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitić, D.; Čarkić, J.; Jaćimović, J.; Lazarević, M.; Jakšić Karišik, M.; Toljić, B.; Milašin, J. The Impact of Nano-Hydroxyapatite Scaffold Enrichment on Bone Regeneration In Vivo—A Systematic Review. Biomimetics 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, V.; Čolović, B.; Marković, D.; Petrović, M.; Jokanović, M.; Milosavljević, P.; Sopta, J. In Vivo Investigation of ALBO-OS Scaffold Based on Hydroxyapatite and PLGA. Journal of Nanomaterials 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, V.; Čolović, B.; Marković, D.; Petrović, M.; Soldatović, I.; Antonijević, D.; Milosavljević, P.; Sjerobabin, N.; Sopta, J. Extraordinary Biological Properties of a New Calcium Hydroxyapatite/Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)-Based Scaffold Confirmed by in Vivo Investigation. Biomedical Engineering / Biomedizinische Technik 2017, 62, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, H. J.; Zhu, X. D.; Vaidya, S.; Xiang, Z.; Fan, Y. J.; Zhang, X. D. Enhanced Repair of a Critical-Sized Segmental Bone Defect in Rabbit Femur by Surface Microstructured Porous Titanium. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2014, 25, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassbender, M.; Minkwitz, S.; Thiele, M.; Wildemann, B. Efficacy of Two Different Demineralised Bone Matrix Grafts to Promote Bone Healing in a Critical-Size-Defect: A Radiological, Histological and Histomorphometric Study in Rat Femurs. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2014, 38, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Wu, H. Tissue-Engineered Composite Scaffold of Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) and Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles Seeded with Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2017, 18, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, F.; Lang, A.; Schoon, J.; Wassilew, G. I.; Reichert, J. Scaffold Guided Bone Regeneration for the Treatment of Large Segmental Defects in Long Bones. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, M. L.; Velidandi, A.; Pabbathi, N. P. P.; Dahariya, S.; Parcha, S. R. Assessment of Properties, Applications and Limitations of Scaffolds Based on Cellulose and Its Derivatives for Cartilage Tissue Engineering: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 175, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, G.; Baudoin, R.; Dumas, D.; Baptiste, D.; Hubert, P.; Stoltz, J. F.; Dellacherie, E.; Mainard, D.; Netter, P.; Payan, E. Sodium Alginate Sponges with or without Sodium Hyaluronate:In Vitro Engineering of Cartilage. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 57, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kang, E. H.; Choi, S.; Jeon, E. J.; Cho, J. H.; Kang, D.; Lee, H.; Yun, I. S.; Cho, S.-W. Tissue-Adhesive Chondroitin Sulfate Hydrogel for Cartilage Reconstruction. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4230–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, M.; Antonijevic, D.; Milutinovic-Smiljanic, S.; Trisic, D.; Colovic, B.; Kosanovic, D.; Prokic, B.; Vasic, J.; Zivkovic, S.; Milasin, J.; Danilovic, V.; Djuric, M.; Jokanovic, V. Developing a Novel Resorptive Hydroxyapatite-Based Bone Substitute for over-Critical Size Defect Reconstruction: Physicochemical and Biological Characterization and Proof of Concept in Segmental Rabbit’s Ulna Reconstruction. Biomedical Engineering / Biomedizinische Technik 2020, 65, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Lin, D.; Yu, Y.; Niu, H.; Guo, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, C. Bioinspired Trimodal Macro/Micro/Nano-Porous Scaffolds Loading rhBMP-2 for Complete Regeneration of Critical Size Bone Defect. Acta Biomaterialia 2016, 32, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. D.; Zhang, C. Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. X.; Zheng, S. G. RUNX2 Regulates Osteoblast Differentiation via the BMP4 Signaling Pathway. J Dent Res 2022, 101, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oryan, A.; Alidadi, S.; Bigham-Sadegh, A.; Moshiri, A. Comparative Study on the Role of Gelatin, Chitosan and Their Combination as Tissue Engineered Scaffolds on Healing and Regeneration of Critical Sized Bone Defects: An in Vivo Study. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2016, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lv, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F. The Healing of Critical-Size Calvarial Bone Defects in Rat with rhPDGF-BB, BMSCs, and β-TCP Scaffolds. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2012, 23, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, X.; Zhao, D.; Jiang, W.; Du, Z.; Li, Q.; Jiang, C.; Han, D. Three Dimensional Printed Polylactic Acid-Hydroxyapatite Composite Scaffolds for Prefabricating Vascularized Tissue Engineered Bone: An in Vivo Bioreactor Model. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J. P.; Yeager, K.; Bhumiratana, S.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Grayson, W. L. Bioreactor Cultivation of Anatomically Shaped Human Bone Grafts. In Biomimetics and Stem Cells; Vunjak-Novakovic, G., Turksen, K., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhurina, E. K.; Karalkin, P. A.; Komlev, V. S.; Sviridova, I. K.; Kirsanova, V. A.; Akhmedova, S. A.; Shanskiy, Y. D.; Fedotov, A. Y.; Barinov, S. M.; Sergeeva, N. S. Physicochemical and Osteoplastic Characteristics of 3D Printed Bone Grafts Based on Synthetic Calcium Phosphates and Natural Polymers. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 347, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettwer, W.; Horstmann, P. F.; Bischoff, S.; Güllmar, D.; Reichenbach, J. R.; Poh, P. S. P.; Van Griensven, M.; Gras, F.; Diefenbeck, M. Establishment and Effects of Allograft and Synthetic Bone Graft Substitute Treatment of a Critical Size Metaphyseal Bone Defect Model in the Sheep Femur. APMIS 2019, 127, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AO Research Institute Davos, Clavadelerstrasse 8, 7270 Davos Platz, Switzerland; Verrier, S. ; Alini, M.; Alsberg, E.; Buchman, S.; Kelly, K.; Laschke, M.; Menger, M.; Murphy, W.; Stegemann, J.; Schütz, M.; Miclau, T.; Stoddart, M.; Evans, C. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Approaches to Improving the Healing of Large Bone Defects. eCM 2016, 32, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, P.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, H. Biomaterial-Based Scaffolds in Promotion of Cartilage Regeneration: Recent Advances and Emerging Applications. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 2023, 41, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Schwartz, Z.; Kahn, A.; Li, X.; Shao, Z.; Sun, M.; Ao, Y.; Boyan, B. D.; Chen, H. Advances in Porous Scaffold Design for Bone and Cartilage Tissue Engineering and Regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews 2019, 25, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.; Dvir-Ginzberg, M. SOX9 and the Many Facets of Its Regulation in the Chondrocyte Lineage. Connective Tissue Research 2017, 58, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, R.; Hata, K.; Takahata, Y.; Murakami, T.; Nakamura, E.; Yagi, H. Regulation of Cartilage Development and Diseases by Transcription Factors. J Bone Metab 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeuf, S.; Börger, M.; Hennig, T.; Winter, A.; Kasten, P.; Richter, W. Enhanced ITM2A Expression Inhibits Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Differentiation 2009, 78, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 10993-5:2009 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity, 2009.

- Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Fan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Q. Biomimetic Mineralized Hierarchical Hybrid Scaffolds Based on in Situ Synthesis of Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Chitosan/Chondroitin Sulfate/Hyaluronic Acid for Bone Tissue Engineering. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2017, 157, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wei, L.; Su, X.; Qin, L.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Hu, N. Preparation and Characterization of Biomimetic Functional Scaffold with Gradient Structure for Osteochondral Defect Repair. Bioengineering 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Surgery planning procedure in Autodesk 3D Max 2010 software. Numbers 1–3: identification numbers of every experimental animal and 3D model of the lateral femur reconstruction graft with the fixation hole. 4: 3D appearance of rabbit’s femur. 5: surgical guide for the resection of the lateral condyle (green color) with the fixation holes for fixation screws (pink color). 6: planned resection plane (transparent red color) of the lateral condyle.

Figure 1.

Surgery planning procedure in Autodesk 3D Max 2010 software. Numbers 1–3: identification numbers of every experimental animal and 3D model of the lateral femur reconstruction graft with the fixation hole. 4: 3D appearance of rabbit’s femur. 5: surgical guide for the resection of the lateral condyle (green color) with the fixation holes for fixation screws (pink color). 6: planned resection plane (transparent red color) of the lateral condyle.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial activity of grade concentrations of nHAP gel and control, after 24 h, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial activity of grade concentrations of nHAP gel and control, after 24 h, *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Figure 3.

Chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of SCAPs after 7 days of culturing in induction mediums, enriched with 0.125% of nHAP gel, and control, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of SCAPs after 7 days of culturing in induction mediums, enriched with 0.125% of nHAP gel, and control, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal section of lateral femur condyle with implanted 3D graft, H&E, magnification 20x, locations of graft (red arrows), chondrocytes (black arrows) and fibroblasts (yellow arrows).

Figure 4.

Longitudinal section of lateral femur condyle with implanted 3D graft, H&E, magnification 20x, locations of graft (red arrows), chondrocytes (black arrows) and fibroblasts (yellow arrows).

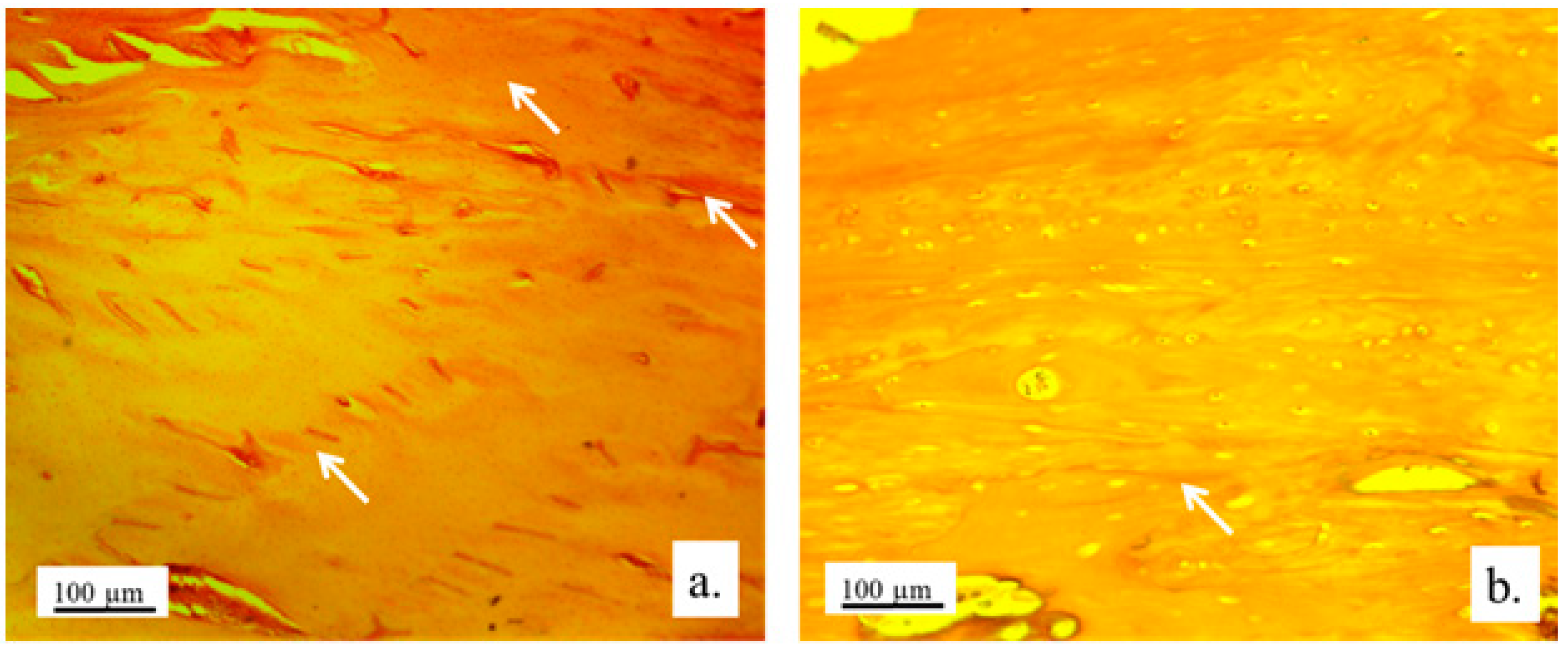

Figure 5.

Cartilaginous tissue in longitudinal sections of the lateral femur condyles: a. control and b. with 3D graft, H&E, magnification 50x, chondrocytes (red arrows) and lacunae with fragments of implanted material (black arrows).

Figure 5.

Cartilaginous tissue in longitudinal sections of the lateral femur condyles: a. control and b. with 3D graft, H&E, magnification 50x, chondrocytes (red arrows) and lacunae with fragments of implanted material (black arrows).

Figure 6.

Cartilaginous tissue in the longitudinal section of the lateral femur condyle: a. control and b. with 3D graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 50x, chondrocytes (red arrows), fibroblasts (yellow arrows) and fragments of graft (black arrows).

Figure 6.

Cartilaginous tissue in the longitudinal section of the lateral femur condyle: a. control and b. with 3D graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 50x, chondrocytes (red arrows), fibroblasts (yellow arrows) and fragments of graft (black arrows).

Figure 7.

a) Longitudinal section of the articular femur surface with 3D graft, newly formed irregular cartilage (blue arrow) and regular cartilage in contact with bone tissue (white arrow), immunohistochemical Goldner stain, magnification 10×; b) Longitudinal section of the articular femur surface with 3D graft, regular cartilage structure (black arrow) and newly formed irregular cartilage structure (yellow arrows), Toluidine blue stain, magnification 10x.

Figure 7.

a) Longitudinal section of the articular femur surface with 3D graft, newly formed irregular cartilage (blue arrow) and regular cartilage in contact with bone tissue (white arrow), immunohistochemical Goldner stain, magnification 10×; b) Longitudinal section of the articular femur surface with 3D graft, regular cartilage structure (black arrow) and newly formed irregular cartilage structure (yellow arrows), Toluidine blue stain, magnification 10x.

Figure 8.

Longitudinal section of a femur with 3D graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 20x, osteocytes (white arrows), fibroblasts (black arrows) and location of implanted material (red arrows).

Figure 8.

Longitudinal section of a femur with 3D graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 20x, osteocytes (white arrows), fibroblasts (black arrows) and location of implanted material (red arrows).

Figure 9.

Cross section of femur with implanted 3D graft, H&E, magnification 100x, osteocytes (white arrows), fibroblasts with cytoplasmic extensions (red arrow), magnified junction of femur bone tissue and 3D graft (black arrow and black square) and location of implanted graft (yellow arrows).

Figure 9.

Cross section of femur with implanted 3D graft, H&E, magnification 100x, osteocytes (white arrows), fibroblasts with cytoplasmic extensions (red arrow), magnified junction of femur bone tissue and 3D graft (black arrow and black square) and location of implanted graft (yellow arrows).

Figure 10.

Cross-section of lateral femur condyle with implanted graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 100×, osteocytes (yellow arrows) and location of implanted material (black arrows).

Figure 10.

Cross-section of lateral femur condyle with implanted graft, stained with immunohistochemical technique Picrosirius red, magnification 100×, osteocytes (yellow arrows) and location of implanted material (black arrows).

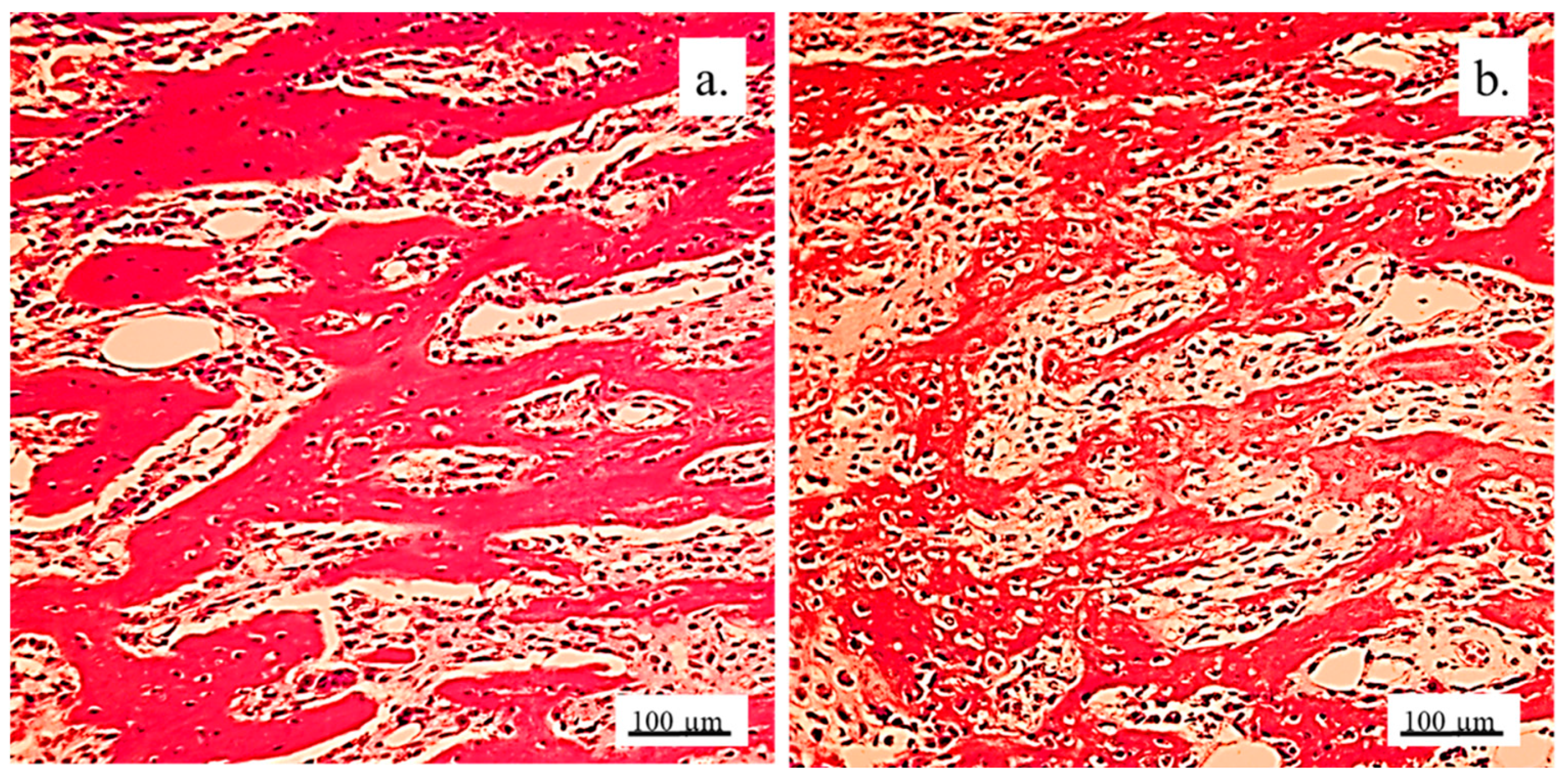

Figure 11.

Cross-section of lateral femur condyle in control (a), and with implanted graft (b), H&E, magnification 200×, osteocytes (white arrows) and blood vessels (yellow arrows).

Figure 11.

Cross-section of lateral femur condyle in control (a), and with implanted graft (b), H&E, magnification 200×, osteocytes (white arrows) and blood vessels (yellow arrows).

Figure 12.

Immunoreactivity to osteocalcin. Representative micrographs of femur tissue stained with immunohistochemical technique for visualization of osteocalcin: longitudinal section of femur without implant (a), and femur with an implanted graft (b). White arrows indicate sites of immunoreaction of bone tissue to osteocalcin, magnification 100x.

Figure 12.

Immunoreactivity to osteocalcin. Representative micrographs of femur tissue stained with immunohistochemical technique for visualization of osteocalcin: longitudinal section of femur without implant (a), and femur with an implanted graft (b). White arrows indicate sites of immunoreaction of bone tissue to osteocalcin, magnification 100x.

Figure 13.

Collagen deposition in bone tissue. Representative micrographs of bone tissue stained with histochemical technique Picrosirius red: control bone (a), bone with implanted graft (b), 100x magnification.

Figure 13.

Collagen deposition in bone tissue. Representative micrographs of bone tissue stained with histochemical technique Picrosirius red: control bone (a), bone with implanted graft (b), 100x magnification.

Figure 14.

Relative expression levels of a) osteogenic and b) chondrogenic markers in tissue with implanted material, compared to control; *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001.

Figure 14.

Relative expression levels of a) osteogenic and b) chondrogenic markers in tissue with implanted material, compared to control; *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001.

Table 1.

Primers with corresponding sequences used in the study.

Table 1.

Primers with corresponding sequences used in the study.

| BMP4 |

Rv |

5′ GGG TGA GTG GAT GG AAC 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ CTC GAT GAG TAT GAT AAG GTG GTA 3′ |

| RUNX2 |

Rv |

5′ GTC TCG GTG GCT GGT AGT GA 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ ACA AAC AAC CAC AGA ACC ACA AGT 3′ |

| ALP |

Rv |

5′ ATG GCA GTG AAG GGC TTC TT 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ CCA CGT CTT CAC ATT TGG TG 3′ |

| ITM2A |

Rv |

5′ GTCCTGCCAAGATGAATGAA 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ AGGATCTCCTCTTGCAGTC 3′ |

| FOXC1 |

Rv |

5′ CGGGGCTCTCGATCTTGGGCA 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ AAGACCGAGAACGGTACGTG 3′ |

| SOX9 |

Rv |

5’ CTC TTT TGC ACC CCT CCC ATT 3’ |

| Fw |

5’ GAC TTC ACA TGT CCC AGC ACT A 3’ |

| GAPDH |

Rv |

5′ CCC TGT TGC TGT AGC CAA ATT CGT 3′ |

| Fw |

5′ TCA TGA CCA CAG TCC ATG CCA TCA 3′ |

Table 2.

Stereological parameters of the analysis of cartilage and bone tissue in the region of the lateral femur condyle replaced with the personalized 3D graft.

Table 2.

Stereological parameters of the analysis of cartilage and bone tissue in the region of the lateral femur condyle replaced with the personalized 3D graft.

| Parameters |

Control |

3D graft |

| Volume density of chondrocytes (mm0) |

0.362±0.044* |

0.295±0.051 |

| Volume density of cartilage matrix (mm0) |

0.638±0.076 |

0.705±0.079 |

| Number of chondrocytes |

24805.1±3007.4*** |

17545.6±2107.4 |

| Numerical density of chondrocytes (mm-3) |

3664.4±417.8** |

2931.4±386.2 |

| Surface area of chondrocytes (μm2) |

238.5±22.6 |

305.7±28.6*** |

| Surface area of chondrocytes’ nuclei (μm2) |

75.3±9.9 |

98.6±10.2*** |

| Surface area of lacunae of cartilage (μm2) |

136.5±12.4 |

199.4±16.5**** |

| NCR of chondrocytes |

0.323±0.021 |

0.402±0.033*** |

| Volume density of osteocytes (mm0) |

0.266±0.019** |

0.225±0.017 |

| Volume density of bone matrix (mm0) |

0.560±0.044*** |

0.447±0.041 |

| Volume density of blood vessels in bone tissue (mm0) |

0.174±0.015 |

0.328±0.024**** |

| Number of osteocytes |

28574.2±2314.6**** |

21759.1±2219.4 |

| Numerical density of osteocytes (mm-3) |

3015.6±353.3* |

2554.5±311.1 |

| Surface area of osteocytes (μm2) |

172.6±15.4*** |

139.3±13.2 |

| Surface area of osteocytes nuclei (μm2) |

69.4±8.4 |

60.5±8.2 |

| NCR of osteocytes |

0.325±0.031 |

0.409±0.038*** |

| Diameter of blood vessels (µm) |

55.5±6.6 |

68.4±7.2** |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).