Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

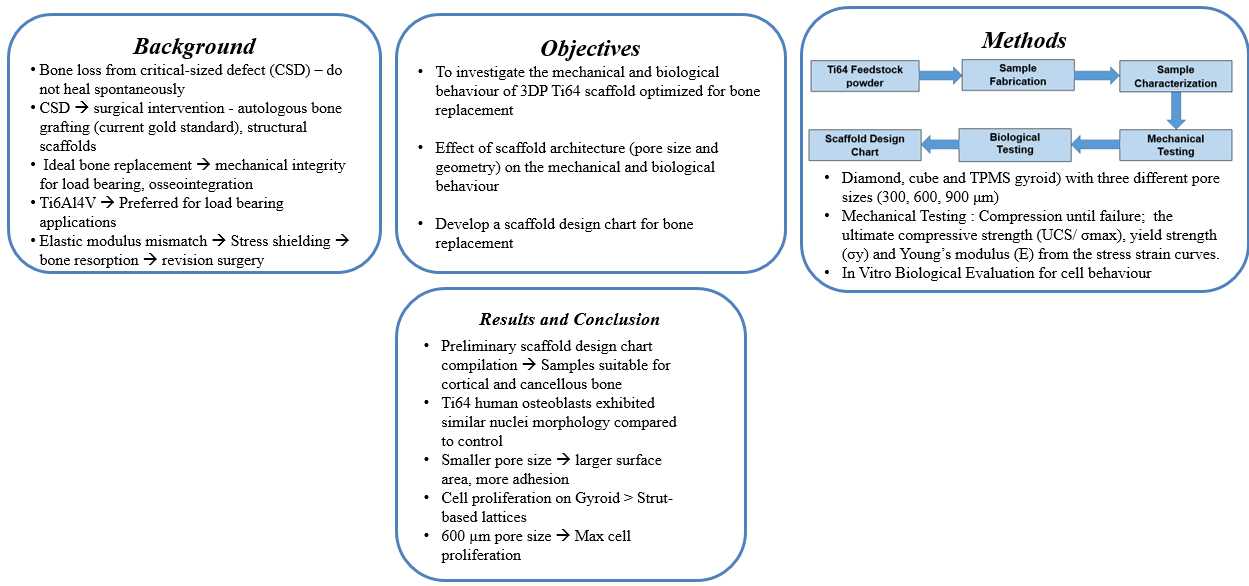

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

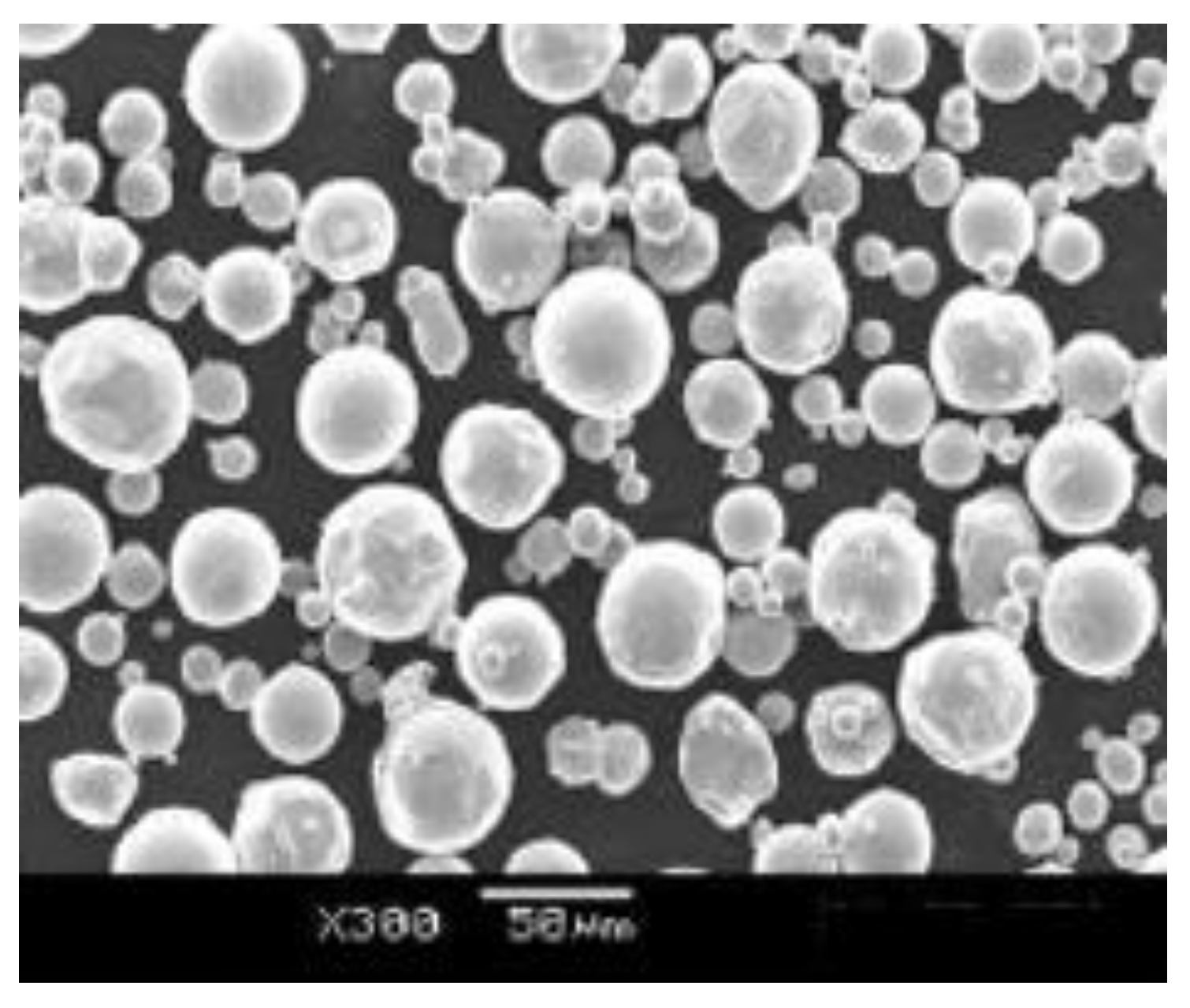

2.1. Feedstock Powder

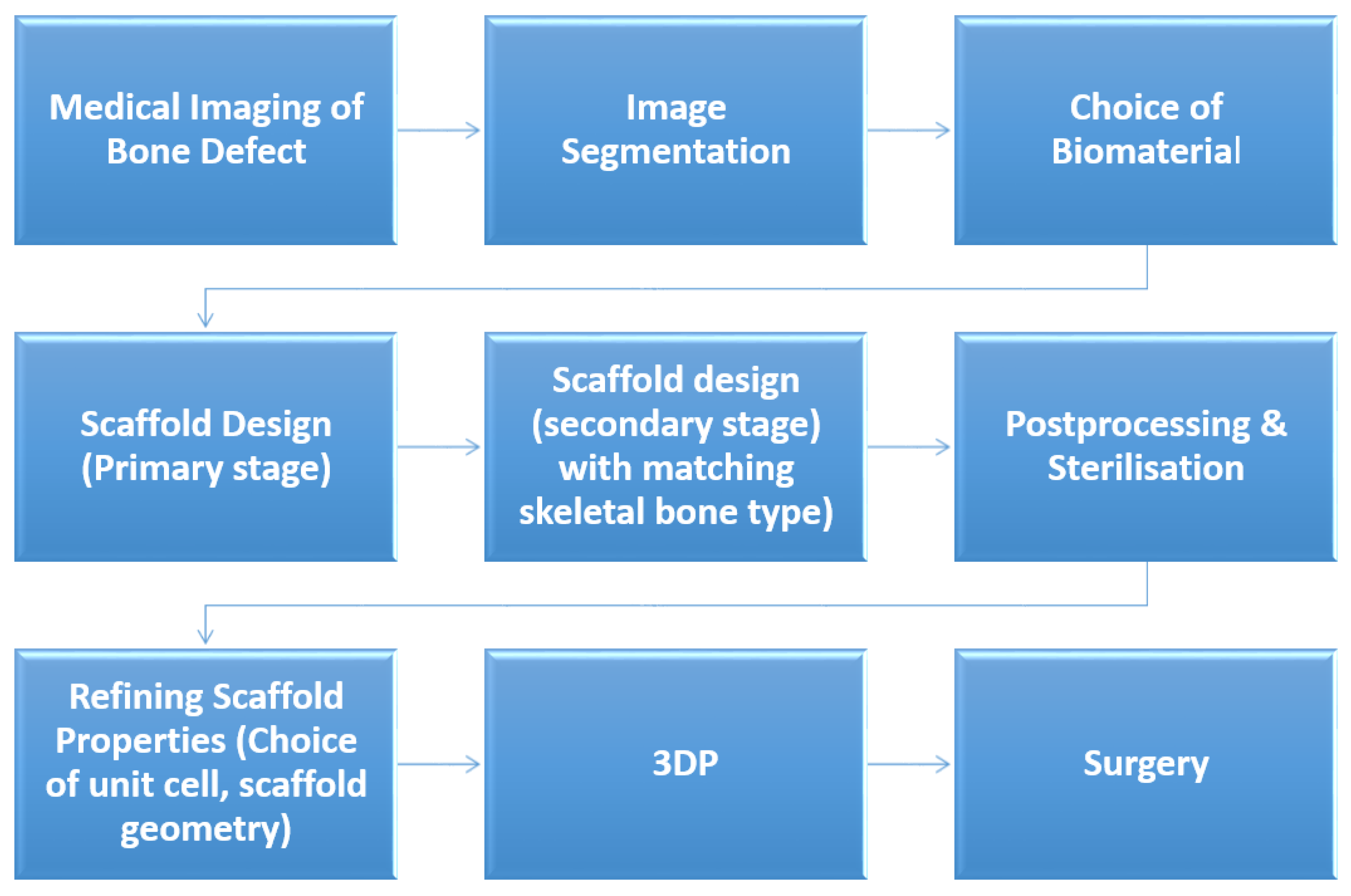

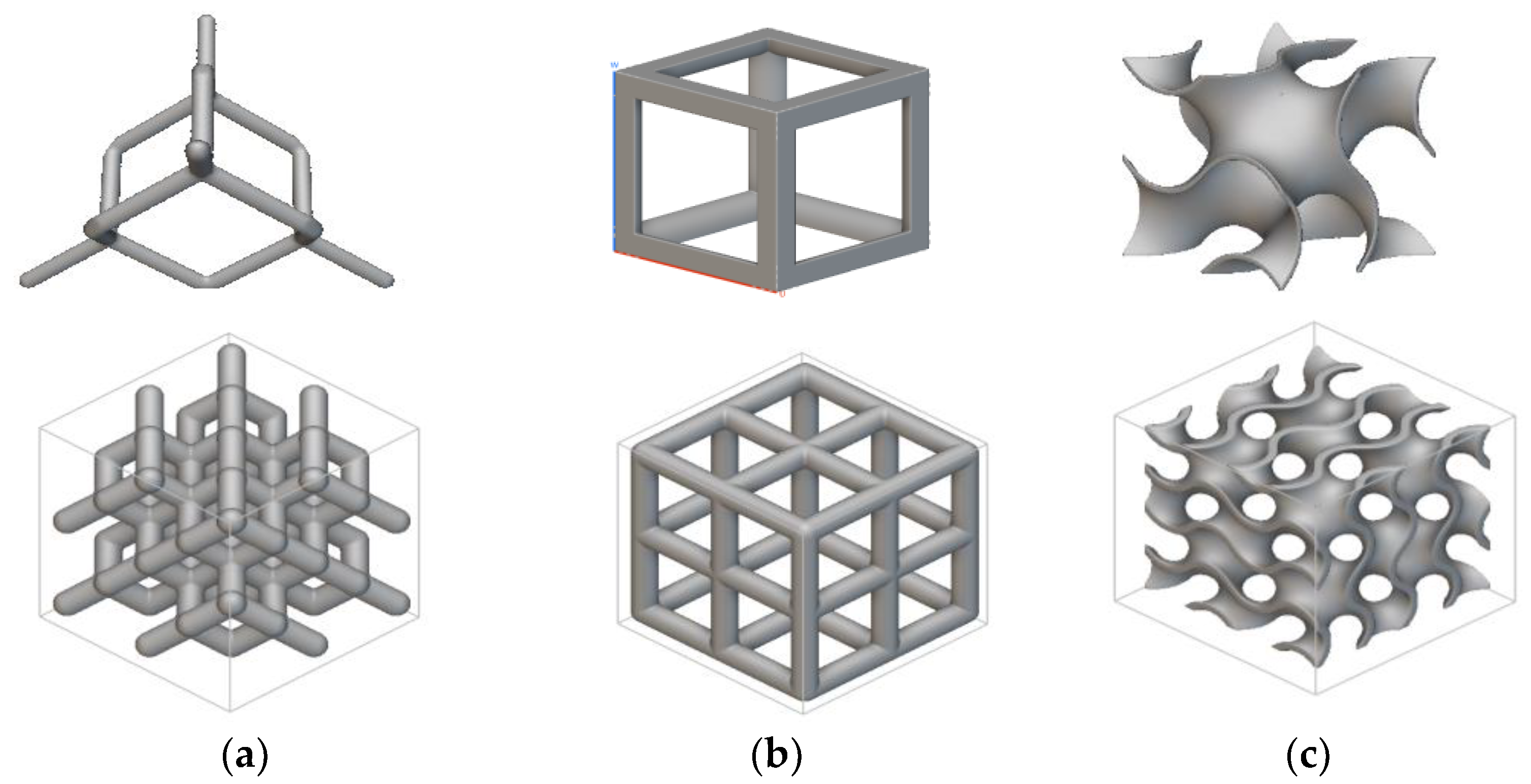

2.2. Sample Design and Fabrication

2.3. Sample Characterization

2.3.1. Dry Weighing, MicroCT (µCT) Scanning and SEM

2.3.2. Mechanical Testing

2.3.3. In Vitro Biological Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

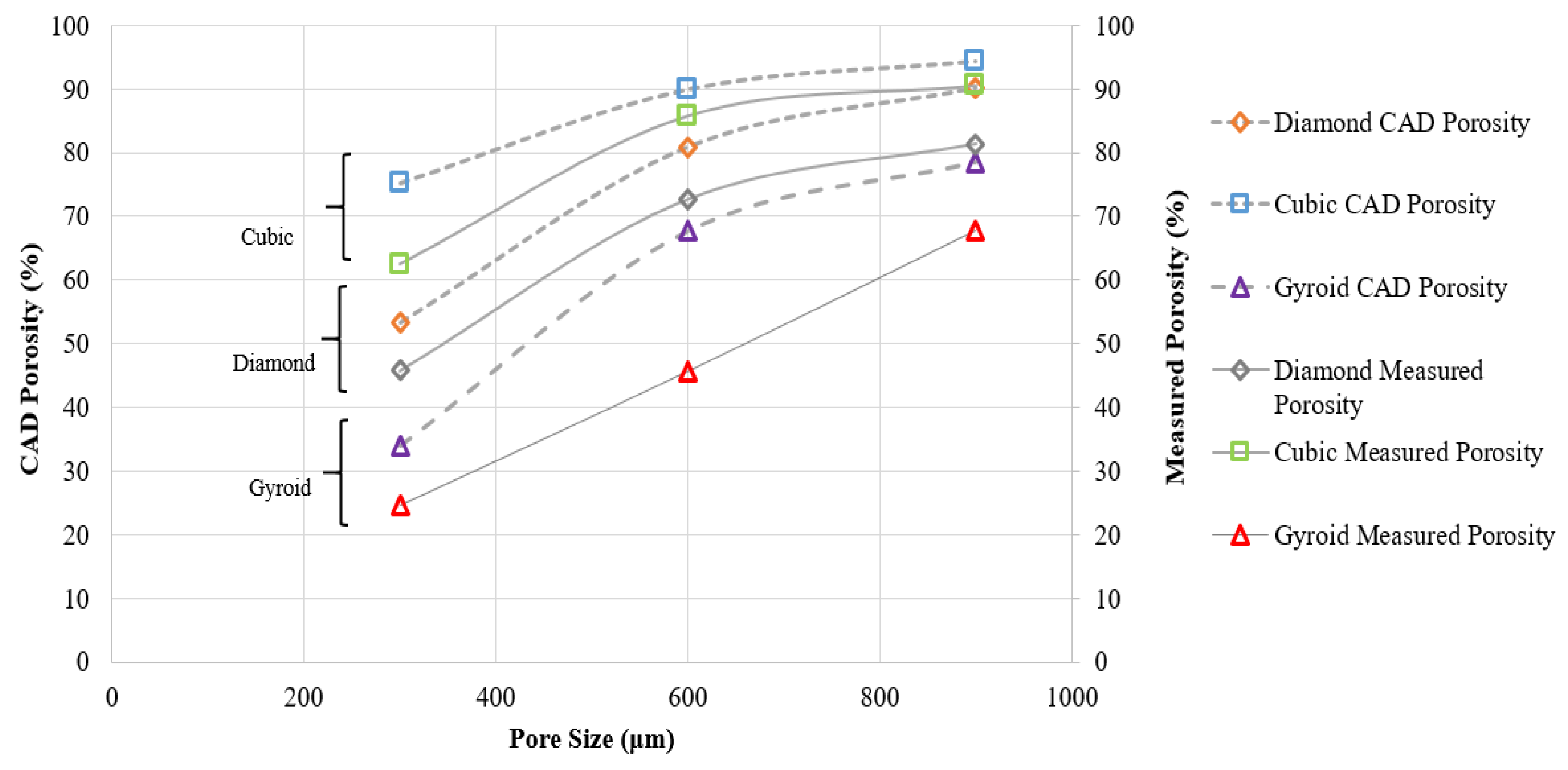

3.1. Sample Characterization

3.2. Compressive Properties

3.2. Biological Performance of 3DP Ti64 scaffolds

3.2.1. Cytocompatibility Assessment

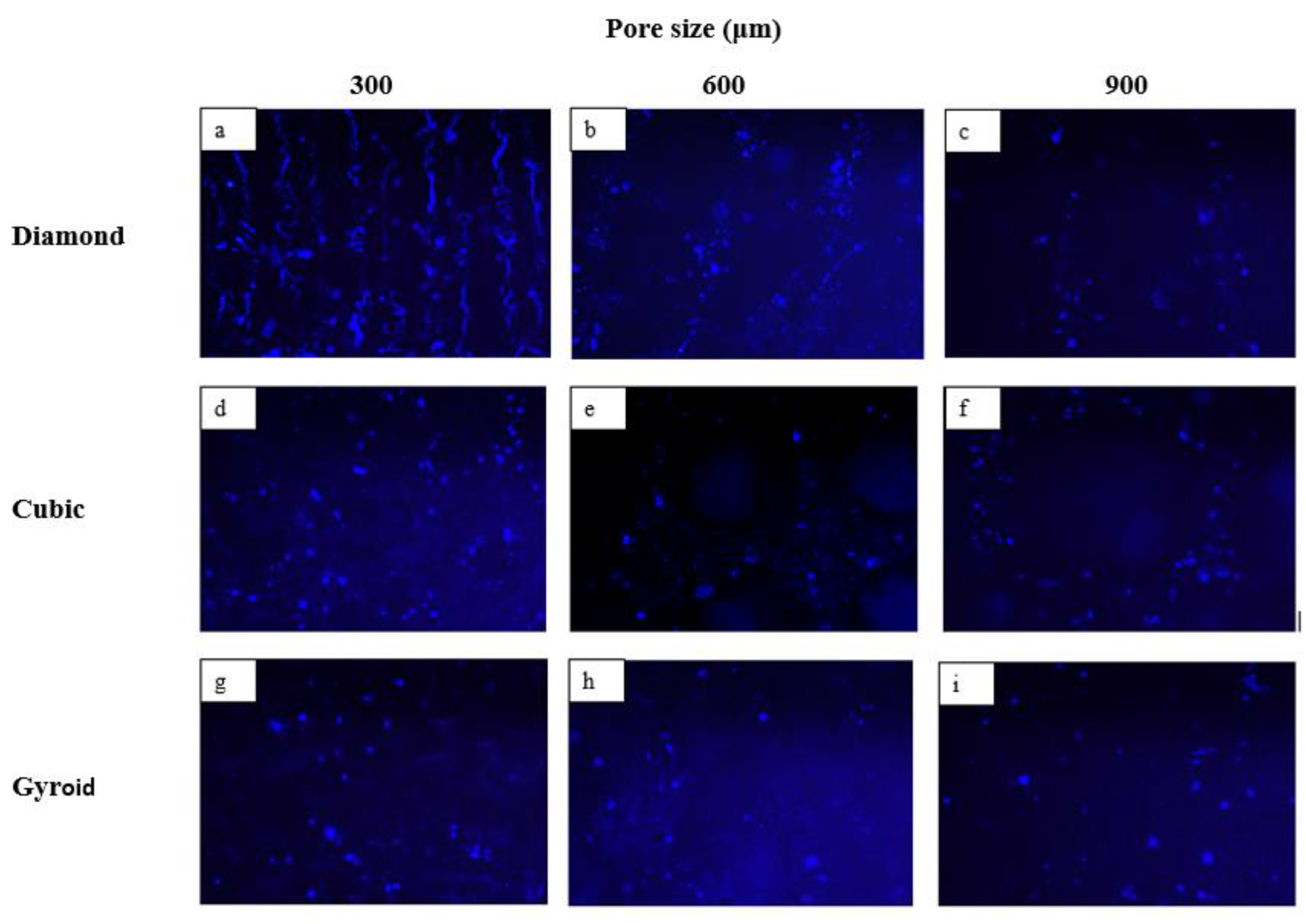

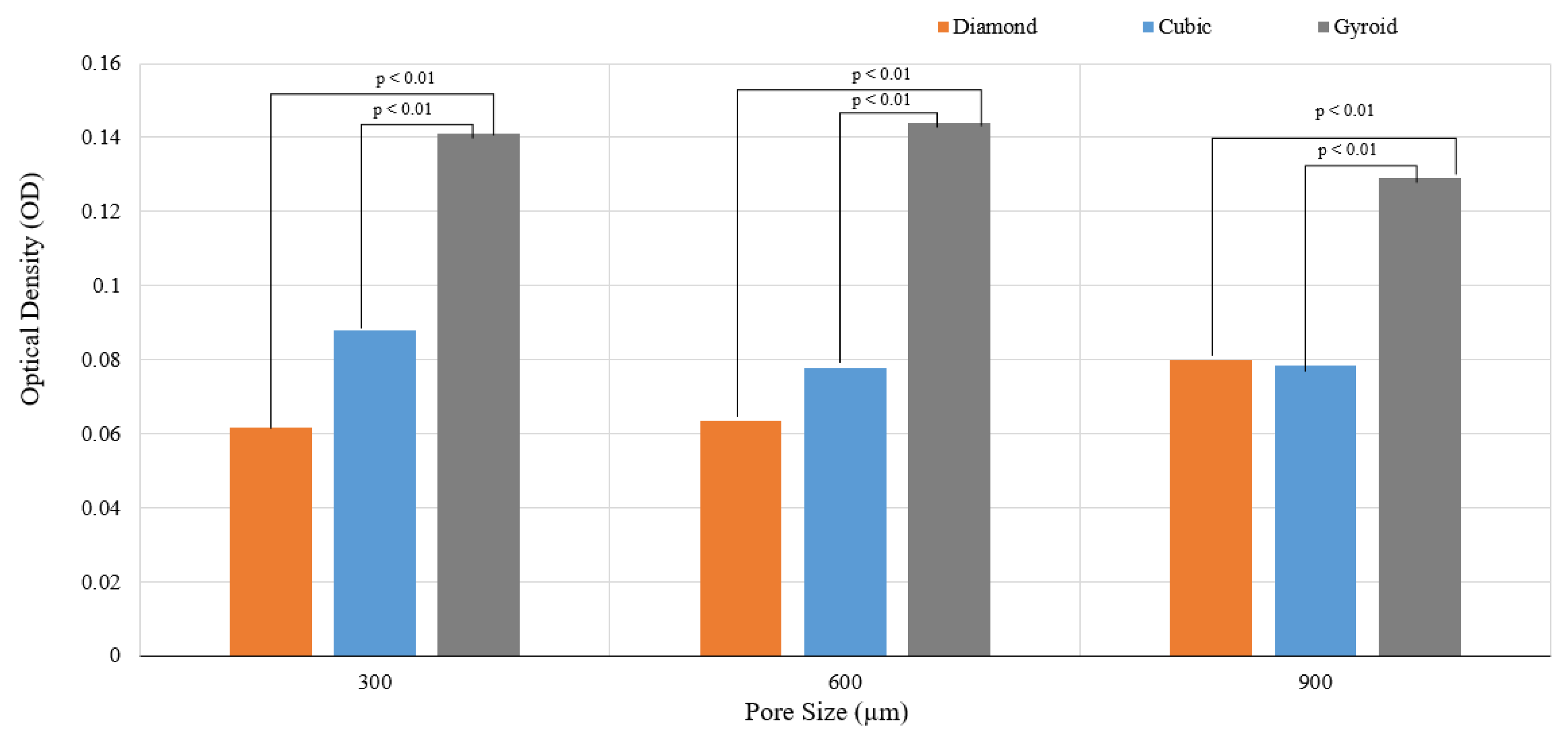

3.2.2. Impact of Pore Size on Cell Adherence and Cell Proliferation

| D300 > C300 > G300 |

| G600 > G300 > G900 |

| C300 > D900 > C900 > C600 > D600 > D300 (Figure 17) |

| G600 > G300 > G900 > C300 > D900 > C900 > C600 > D600 > D300 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| BTE 3DP |

Bone Tissue Engineering 3D printing |

| CSD | Critical-sized bone defects |

| ELI | Extra low interstitial |

| µCT | MicroCT |

| UCS | Ultimate compressive strength |

| HOB | Human osteoblast |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| DAPI | 4', 6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide |

| OD | optical density |

| C | Cubic |

| TC | Truncated cube |

| TCO | Truncated cuboctahedron |

| RD | Rhombic dodecahedron |

| D | Diamond |

| RCO | rhombi cuboctahedron |

| S | Star |

| X | Cross |

| P | Primitive |

| I | I-WP |

| G | Gyroid |

References

- Popov, V.V.; Muller-Kamskii, G.; Kovalevsky, A.; Dzhenzhera, G.; Strokin, E.; Kolomiets, A.; Ramon, J. Design and 3D-printing of titanium bone implants: brief review of approach and clinical cases. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2018, 8, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T.D.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Hui, D. Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): A Review of Materials, Methods, Applications and Challenges. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Li, D.; Ni, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, B. 3D printing of acellular scaffolds for bone defect regeneration: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Khan, R.H.; Suman, R. 3D printing applications in bone tissue engineering. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 11, S118–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauth, A.; Schemitsch, E.; Norris, B.; Nollin, Z.; Watson, J.T. Critical-Size Bone Defects: Is There a Consensus for Diagnosis and Treatment? J. Orthop. Trauma 2018, 32, S7–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koolen, M.; Yavari, S.A.; Lietaert, K.; Wauthle, R.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Weinans, H. Bone Regeneration in Critical-Sized Bone Defects Treated with Additively Manufactured Porous Metallic Biomaterials: The Effects of Inelastic Mechanical Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, L.; Pan, W.; Yang, F.; Jiang, W.; Wu, X.; Kong, X.; Dai, K.; Hao, Y. In vitro and in vivo study of additive manufactured porous Ti6Al4V scaffolds for repairing bone defects. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.; Mirzaali, M.; Apachitei, I.; Zhou, J.; Zadpoor, A. Multi-material additive manufacturing technologies for Ti-, Mg-, and Fe-based biomaterials for bone substitution. Acta Biomater. 2020, 109, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Wu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhan, F.; Lai, H.; Gu, Y. The combination of multi-functional ingredients-loaded hydrogels and three-dimensional printed porous titanium alloys for infective bone defect treatment. J. Tissue Eng. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumedei, M.; Savadori, P.; Del Fabbro, M. Synthetic Blocks for Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahar, N.N.F.N.M.N.; Ahmad, N.; Jaafar, M.; Yahaya, B.H.; Sulaiman, A.R.; Hamid, Z.A.A.; Mariatti, M. A review of bioceramics scaffolds for bone defects in different types of animal models: HA and β -TCP. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2022, 8, 052002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.; Klute, L.; Baertl, S.; Walter, N.; Mannala, G.-K.; Frank, L.; Pfeifer, C.; Alt, V.; Kerschbaum, M. The clinical use of bone graft substitutes in orthopedic surgery in Germany—A 10-years survey from 2008 to 2018 of 1,090,167 surgical interventions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2022, 110, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, A.; Rao, Y.; Cai, X. Application of 3D printing technology in bone tissue engineering. Bio-Design Manuf. 2018, 1, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Vahabzadeh, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Bone Tissue Engineering Using 3D Printing. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, C.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Shi, C.; Leng, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Additive manufacturing technique-designed metallic porous implants for clinical application in orthopedics. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 25210–25227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitelli, S.; Accoto, D.; Trombetta, M.; Rainer, A. Current trends in the design of scaffolds for computer-aided tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Johnson, B.N.; Jia, X. Three-dimensional (3D) printed scaffold and material selection for bone repair. Acta Biomater. 2019, 84, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, S.; Vijayavenkataraman, S. Design of 3D printed scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: A review. Bioprinting 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajje, A.; Kolos, E.C.; Wang, J.K.; Maleksaeedi, S.; He, Z.; Wiria, F.E.; Choong, C.; Ruys, A.J. Physical and mechanical characterisation of 3D-printed porous titanium for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Student, M.S. 3D printing and titanium alloys: a paper review. Eur. Acad. Res. 2016, 3, 11144–11154. [Google Scholar]

- Dziaduszewska, M.; Zieliński, A. Structural and Material Determinants Influencing the Behavior of Porous Ti and Its Alloys Made by Additive Manufacturing Techniques for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wubneh, A.; Tsekoura, E.K.; Ayranci, C.; Uludağ, H. Current state of fabrication technologies and materials for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2018, 80, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariwala, S.H.; Lewis, G.S.; Bushman, Z.J.; Adair, J.H.; Donahue, H.J. 3D Printing of Personalized Artificial Bone Scaffolds. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2015, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunello, G.; Sivolella, S.; Meneghello, R.; Ferroni, L.; Gardin, C.; Piattelli, A.; Zavan, B.; Bressan, E. Powder-based 3D printing for bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germaini, M.-M.; Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S.; Deterre, R.; Corre, P.; Weiss, P. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering – A critical review of the state of the art and new concepts. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhu, M.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, C.; Bai, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Lu, T. The contribution of pore size and porosity of 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds to osteogenesis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2022, 133, 112651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, N.; Fujibayashi, S.; Takemoto, M.; Sasaki, K.; Otsuki, B.; Nakamura, T.; Matsushita, T.; Kokubo, T.; Matsuda, S. Effect of pore size on bone ingrowth into porous titanium implants fabricated by additive manufacturing: An in vivo experiment. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 59, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Pan, S.-T.; Qiu, J.-X. The osteogenic effects of porous Tantalum and Titanium alloy scaffolds with different unit cell structure. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 210, 112229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zhang, B.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, C. Bionic mechanical design of titanium bone tissue implants and 3D printing manufacture. Mater. Lett. 2017, 208, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Pei, X.; Zhou, C.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ronca, A.; D'Amora, U.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; et al. The biomimetic design and 3D printing of customized mechanical properties porous Ti6Al4V scaffold for load-bearing bone reconstruction. Mater. Des. 2018, 152, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, S.A.; Ahmadi, S.; Wauthle, R.; Pouran, B.; Schrooten, J.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A. Relationship between unit cell type and porosity and the fatigue behavior of selective laser melted meta-biomaterials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 43, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, D.Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, M.; Jafar, S. Mechanical Properties of Optimized Diamond Lattice Structure for Bone Scaffolds Fabricated via Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2018, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wally, Z.J.; Haque, A.M.; Feteira, A.; Claeyssens, F.; Goodall, R.; Reilly, G.C. Selective laser melting processed Ti6Al4V lattices with graded porosities for dental applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 90, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. 3D printed Ti6Al4V bone scaffolds with different pore structure effects on bone ingrowth. J. Biol. Eng. 2021, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, S.Y.; Sun, C.-N.; Leong, K.F.; Wei, J. Compressive properties of Ti-6Al-4V lattice structures fabricated by selective laser melting: Design, orientation and density. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 16, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Marquez, D.; Delmar, Y.; Sun, S.; Stewart, R.A. Exploring Macroporosity of Additively Manufactured Titanium Metamaterials for Bone Regeneration with Quality by Design: A Systematic Literature Review. Materials 2020, 13, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharin, H.A.; Rani, A.M.A.; Ginta, T.L.; I Azam, F. Additive Manufacturing Technology for Biomedical Components: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 328, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D. Mechanical properties of a Ti6Al4V porous structure produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2013, 49, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Ding, S.; Wen, C. Additive manufacturing technology for porous metal implant applications and triple minimal surface structures: A review. Bioact. Mater. 2019, 4, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Ling, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Benyshek, C.; Zan, R.; Miri, A.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. Three-dimensional printing of metals for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Bio 2019, 3, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A.K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A.K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants – A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; Cheng, L.; Huo, M.; Yin, J.; Hao, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, P.; et al. Additive manufacturing of structural materials. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 2021, 145, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.A.; Trobos, M.; Thomsen, P.; Palmquist, A. Commercially pure titanium (cp-Ti) versus titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) materials as bone anchored implants — Is one truly better than the other? Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 62, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseti, L.; Parisi, V.; Petretta, M.; Cavallo, C.; Desando, G.; Bartolotti, I.; Grigolo, B. Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: State of the art and new perspectives. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 78, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Chua, Z.Y.; Moon, S.K.; Song, J.; Bi, G.; Zheng, H. Femtosecond Laser Produced Hydrophobic Hierarchical Structures on Additive Manufacturing Parts. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Pan, C.; Lin, C.; Yang, T.; Huang, Y.; Ou, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, D.; Lin, H.; et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of open-cell porous Ti-6Al-4V fabricated by selective laser melting. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 713, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, Z.; Concli, F. A Review of the Selective Laser Melting Lattice Structures and Their Numerical Models. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markhoff, J.; Krogull, M.; Schulze, C.; Rotsch, C.; Hunger, S.; Bader, R. Biocompatibility and Inflammatory Potential of Titanium Alloys Cultivated with Human Osteoblasts, Fibroblasts and Macrophages. Materials 2017, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotaru, H.; Schumacher, R.; Kim, S.-G.; Dinu, C. Selective laser melted titanium implants: a new technique for the reconstruction of extensive zygomatic complex defects. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 37, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-W.; Chen, J.-K.; Lin, B.-H.; Chiang, P.-H.; Tsai, M.-K. Compressive fatigue properties of additive-manufactured Ti-6Al-4V cellular material with different porosities. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousová, M.; Vojtěch, D.; Kubásek, J.; Jablonská, E.; Fojt, J. Promising characteristics of gradient porosity Ti-6Al-4V alloy prepared by SLM process. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 69, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharin, H.A.; Abdul Rani, A.M.; Azam, F.I.; Ginta, T.L.; Sallih, N.; Ahmad, A.; Yunus, N.A.; Zulkifli, T.Z.A. Effect of Unit Cell Type and Pore Size on Porosity and Mechanical Behavior of Additively Manufactured Ti6Al4V Scaffolds. Materials 2018, 11, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavari, S.A.; Wauthle, R.; van der Stok, J.; Riemslag, A.; Janssen, M.; Mulier, M.; Kruth, J.; Schrooten, J.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A. Fatigue behavior of porous biomaterials manufactured using selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 4849–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Santus, C. Notch fatigue and crack growth resistance of Ti-6Al-4V ELI additively manufactured via selective laser melting: A critical distance approach to defect sensitivity. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 121, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.M.; Yavari, S.A.; Wauthle, R.; Pouran, B.; Schrooten, J.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A.A. Additively Manufactured Open-Cell Porous Biomaterials Made from Six Different Space-Filling Unit Cells: The Mechanical and Morphological Properties. Materials 2015, 8, 1871–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Meenashisundaram, G.K.; Kandilya, D.; Fuh, J.Y.H.; Dheen, S.T.; Kumar, A.S. A biomechanical evaluation on Cubic, Octet, and TPMS gyroid Ti6Al4V lattice structures fabricated by selective laser melting and the effects of their debris on human osteoblast-like cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2022, 137, 212829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, F.; Lietaert, K.; Eftekhari, A.; Pouran, B.; Ahmadi, S.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A. Additively manufactured metallic porous biomaterials based on minimal surfaces: A unique combination of topological, mechanical, and mass transport properties. Acta Biomater. 2017, 53, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weißmann, V.; Bader, R.; Hansmann, H.; Laufer, N. Influence of the structural orientation on the mechanical properties of selective laser melted Ti6Al4V open-porous scaffolds. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooreweder, B.; Apers, Y.; Lietaert, K.; Kruth, J.-P. Improving the fatigue performance of porous metallic biomaterials produced by Selective Laser Melting. Acta Biomater. 2017, 47, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, J.; Guo, K.; Wang, L. Compressive mechanical properties and energy absorption characteristics of SLM fabricated Ti6Al4V triply periodic minimal surface cellular structures. Mech. Mater. 2022, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yánez, A.; Cuadrado, A.; Martel, O.; Afonso, H.; Monopoli, D. Gyroid porous titanium structures: A versatile solution to be used as scaffolds in bone defect reconstruction. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, S.A.; Tamaddon, M.; Marghoub, A.; Wang, K.; Babamiri, B.B.; Hazeli, K.; Xu, W.; Lu, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; et al. Mechanical Characterisation and Numerical Modelling of TPMS-Based Gyroid and Diamond Ti6Al4V Scaffolds for Bone Implants: An Integrated Approach for Translational Consideration. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, H.; Kelly, C.N.; Nelson, K.; Gall, K. Compressive anisotropy of sheet and strut based porous Ti–6Al–4V scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 115, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Yu, F.; Zhu, L.; Liang, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q. Early osteointegration evaluation of porous Ti6Al4V scaffolds designed based on triply periodic minimal surface models. J. Orthop. Transl. 2019, 19, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nune, K.; Kumar, A.; Misra, R.; Li, S.; Hao, Y.; Yang, R. Osteoblast functions in functionally graded Ti-6Al-4 V mesh structures. J. Biomater. Appl. 2015, 30, 1182–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Cao, X. Study on Topology Optimization Design, Manufacturability, and Performance Evaluation of Ti-6Al-4V Porous Structures Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Materials 2017, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bael, S.; Chai, Y.C.; Truscello, S.; Moesen, M.; Kerckhofs, G.; Van Oosterwyck, H.; Kruth, J.-P.; Schrooten, J. The effect of pore geometry on the in vitro biological behavior of human periosteum-derived cells seeded on selective laser-melted Ti6Al4V bone scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 2824–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, K. Osteogenesis of 3D printed porous Ti6Al4V implants with different pore sizes. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Montaño, Ó.L.; Cortés-Rodríguez, C.J.; Uva, A.E.; Fiorentino, M.; Gattullo, M.; Monno, G.; Boccaccio, A. Comparison of the mechanobiological performance of bone tissue scaffolds based on different unit cell geometries. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 83, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, Q.; Ge, L.; Zhou, Q.; Warszawik, E.M.; Bron, R.; Lai, K.W.C.; van Rijn, P. Topography induced stiffness alteration of stem cells influences osteogenic differentiation. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Hao, L.; Hussein, A.; Young, P. Ti–6Al–4V triply periodic minimal surface structures for bone implants fabricated via selective laser melting. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 51, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, A.; Takemoto, M.; Saito, T.; Fujibayashi, S.; Neo, M.; Pattanayak, D.K.; Matsushita, T.; Sasaki, K.; Nishida, N.; Kokubo, T.; et al. Osteoinduction of porous Ti implants with a channel structure fabricated by selective laser melting. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Composition (%) |

|---|---|

| Al | 6.46 |

| V | 4.24 |

| Fe | 0.17 |

| N | 0.01 |

| C | 0.007 |

| H | 0.002 |

| Ti | ≈ 90 |

| P300 | P600 | P900 | |

|---|---|---|---|

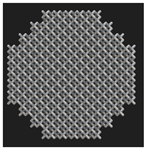

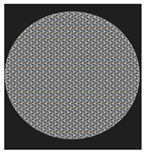

| Designed Top View (CAD) |  |

|

|

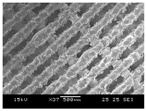

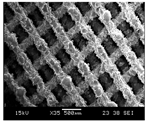

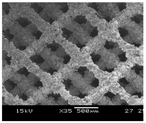

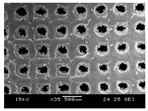

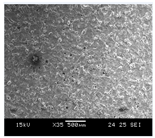

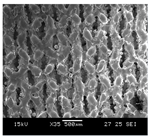

| SEM Images |  |

|

|

| Designed Strut Size (μm) | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Measured Strut Size (SEM) (μm) (n = 5) | 165 ± 3.7 | 185 ± 6.6 | 140 ± 7.5 |

| Measured Strut Size (μCT) (n = 2) | 158 ± 11 | 172 ± 9.5 | 150 ± 6 |

| Measured Pore Size (SEM) (μm) (n = 5) | 258 ± 5.9 | 563 ± 7.5 | 846 ± 10 |

| Measured Pore Size (μCT) (μm) (n = 2) | 230 ± 1.9 | 524 ± 4.8 | 810 ± 2.6 |

| Porosity (CAD) (%) | 53.34 | 80.88 | 90.13 |

| Measured Porosity (%) (μCT) | 45.78 | 72.65 | 81.34 |

| P300 | P600 | P900 | |

|---|---|---|---|

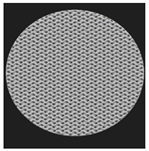

| Designed Top View (CAD) |  |

|

|

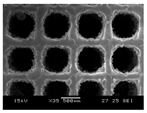

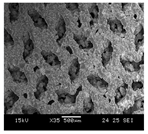

| SEM Images |  |

|

|

| Designed Strut Size (μm) | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Measured Strut Size (SEM) (μm) (n = 5) | 181 ± 9.7 | 191 ± 5.4 | 186 ± 5.3 |

| Measured Strut Size (μ- CT) (n = 2) | 164 ± 5.5 | 177 ± 2.9 | 180 ± 4.6 |

| Measured Pore Size (SEM) (μm) (n = 5) | 268 ± 6.9 | 533 ± 2.7 | 855 ± 3.6 |

| Measured Pore Size (μCT) (μm) (n = 2) | 228 ± 6.2 | 557 ±11.6 | 830 ± 6.8 |

| Porosity (CAD) (%) | 75.17 | 89.94 | 94.38 |

| Measured Porosity (%) (μCT) | 62.45 | 85.78 | 90.54 |

| P300 | P600 | P900 | |

|---|---|---|---|

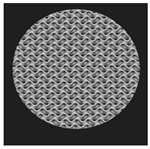

| Designed Top View (CAD) |  |

|

|

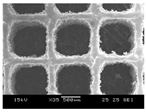

| SEM Images |  |

|

|

| Measured Pore Size (μCT) (μm) (n = 2) | NA* | 358 ± 12.5 | 630 ± 6.8 |

| Theoretical Porosity (CAD) (%) | 34.06 | 67.66 | 78.45 |

| Measured Porosity (%) (μ CT) | 24.54 | 45.67 | 67.87 |

| Scaffold Type | Pore Size ( μm) | Peak Force (kN) | Ultimate Compressive Strength (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Yield Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Porosity (%)) | |||||

| Diamond | 300 (45.78) | 57.33 ± 2.56 | 729.98 ± 32.61 | 10.72 ± 0.40 | 450.96 ± 31.17 |

| 600 (72.65) | 5.33 ± 0.17 | 68.27 ± 2.56 | 2.76 ± 0.14 | 45.43 ± 3.38 | |

| 900 (81.34) | 2.22 ± 0.04 | 27.41 ± 0.55 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 17.5 ± 0.56 | |

| Cube | 300 (62.45) | 21.21 ± 0.5 | 270.10 ± 6.33 | 10.03 ± 1.43 | 260.41 ± 22.44 |

| 600 (85.78) | 5.97 ± 0.3 | 89.33 ± 4.97 | 4.88 ± 0.32 | 51.87 ± 5.41 | |

| 900 (90.54) | 3.12 ± 0.11 | 38.25 ± 1.39 | 2.26 ± 0.41 | 14.86 ± 1.24 | |

| Gyroid | 300 (24.35) | **NA | |||

| 600 (45.67) | 73.78 ± 5.64 | 925.4 ± 72.00 | 13.18 ± 0.85 | 478.16 ± 8.29 | |

| 900 (67.87) | 22.55 ± 0.41 | 282.78 ± 6.05 | 7.83 ± 0.76 | 238.18 ± 10.96 | |

| Author (year) | Technology, Material & Unit Cell | Scaffold Architecture | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Study (2025) | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, TPMS Gyroid | Pore size : 300, 600, 900 μm (fixed strut size) |

ED300 > ED600 >ED900 Similar trend for σy and UCS |

| Taniguchi et al. (2016) [27] | SLM, cp- Ti, Diamond | Pore size : 300, 600, 900 μm (constant porosity 65%) |

E900 > E600 > E300 |

| Pei et al. (2017) [29] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond | Strut diameter : 200, 250,300,350, 400 μm with constant pore size (~ 630 μm) | Increase in strut diameter increased E, UCS linear trend |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [30] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond | Strut diameter : 200, 250,300,350, 400 μm strut diameter with constant pore size (~ 650 μm) | Increase in strut diameter increased E, UCS linear trend |

| Yavari et al. (2014) [31] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, Truncated cuboctahedron | Pore size : 600 – 1452 μm 63 – 90% porosity |

Increase in strut thickness increased E, UCS linear trend |

| Liu et al. (2018) [32] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond | Relative density of 1.28 to 18.6% Varying strut size ,optimised radius |

Increase in strut diameter, optimised radius increased E |

| Wally et al. (2019) [33] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, functionally graded structures (FGS), hexagonal prism | Non-graded pore size : 400 – 650 μm Strut diameter : 300 - 400 μm Varying pore and strut size for FGS |

Overall linear relationship in the elastic region and then plastic yield plateau Graded and non-graded structures exhibited similar E, σy Increase in strut diameter increased E, UCS Increase in porosity, pore size increased E, UCS |

| Deng et al.(2021) [34] | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, Truncated cuboctahedron, open circular pores | Pore size : 650 μm 65 % porosity |

ETC > EC > ED > ECIR Similar trend for σy |

| Author (year) | Technology, Material & Unit Cell | CAD Scaffold Architecture | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Study (2022) | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, TPMS Gyroid | Pore size : 300, 600, 900 μm (fixed strut size) |

EC300 > EC600 >EC900 Similar trend for σy and UCS |

| Ahmadi et al. (2015) [55] |

SLM, Ti64, cubic (C), diamond (D), truncated cube (TC), truncated cuboctahedron (TCO), rhombic dodecahedron (RD), and rhombi cuboctahedron (RCO) | Pore size : 600 – 1452 μm Strut size : 277 – 720 μm |

Compressive properties increased with increase in structure relative density Rhombic cuboctahedron and rhombic dodecahedron highest and lowest compressive properties at relative density < 0.2 Cubic samples relatively stable |

| Yavari et al. (2015) [31] |

SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, Truncated cuboctahedron | Pore size : 600 – 1452 μm Strut size : 277 – 720 μm |

Fatigue life decreased as the porosity of the structure increased Cubic unit cell samples did not fail at endurance limit maximum fatigue strength mechanical properties of the truncated cuboctahedron similar for similar porosities |

| Benedetti et al. (2019) [54] |

SLM, Ti64, cubic (C), star (S) and cross (X) structures | Pore size: 700 – 1500 μm Strut size – 200 - 500 μm |

Maximum stiffness reported by cubic samples Collapse of vertical struts Sharp decrease of stress during plastic deformation |

| Deng et al. (2021) [34] |

SLM, Ti64, cubic (C), diamond (D), truncated cube (TC), circular pores | Pore size : 650 μm Porosity : 65% |

ETC > ECU> EDIA> ECIR |

| Wang et al.(2022) [56] | SLM, Ti64 cubic, octet, and TPMS gyroid | Pore size : 200 – 500 μm Porosity – 40%, 50%, 60% |

Mechanical stability: TPMS > octet > cubic |

| Author (year) | Technology, Material & Unit Cell | CAD Scaffold Architecture | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Study (2022) | SLM, Ti64, Diamond, Cubic, TPMS Gyroid | Pore size : 300, 600, 900 μm (fixed strut size) |

EC300 > EC600 >EC900 Similar trend for σy and UCS Gyroid exhibited max E and UCS despite lesser porosity |

| Bobbert et al. (2017) [57] | SLM, Ti64, TPMS | Porosity range : 43 – 77% Pore size : 361 – 896 μm |

Increase in pore size, porosity reduced E Ductile failure in gyroid |

| Yanez et al. (2018) [61] | SLM, Ti64, TPMS | Porosity: 75 – 90% Circular and ellipsoidal pores |

Deformed gyroids had better mechanical characteristics |

| Zaharin et al. (2018) [52] | SLM, Ti64, TPMS, cubic | Pore size : 300 µm, 400 µm, 500 µm and 600 µm Fixed strut size |

Increase in the pore size reduced E E at 300 µm pore size close to cortical bone range for TPMS and cubic samples |

| Naghavi et al. (2022) [62] | SLM , Ti64, TPMS diamond and gyroid | TPMS Gyroid pore size: 600 – 1200 μm Porosity range: 54 – 72%. TPMS diamond pore size : 900 – 1500 μm Porosity range : 56 – 70% |

Stiffness of the gyroid structures varied from 4.4 – 9.54 GPa σy - 106 – 170 MPa. TPMS diamond samples stiffer at similar pore sizes and porosities |

| Wang et al.(2022) [56] | SLM, Ti64 cubic, octet, and TPMS gyroid | Pore size : 200 – 500 μm Porosity – 40%, 50%, 60% |

Mechanical stability: TPMS > octet > cubic |

| Sun et al. (2022) [60] | SLM Ti64 TPMS gyroid, diamond and primitive | Sheet thickness : 200 – 400 μm | Elastic-brittle failure mechanism for all samples |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).