1. Introduction

Decarbonisation of the shipping industry, which by 2050 could account for almost 17% of world-wide GHG emissions (1), is of global relevance under the current threat of climate change. Existing policies, such as the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and proposed policies, including goal-based fuel standard and economic instruments mentioned in the revised IMO GHG strategy (2) centre around maximising energy efficiency: a function of both technical specification and the way in which a ship is maintained and operated. A distinction therefore must be made between “technical efficiency” which refers to some baseline conditions of the vessel, and “operational efficiency” which considers the practicalities of the voyage, variability in environmental conditions, and commercial realities of operations. Research into operational efficiency measures is therefore crucial due to their potential application in facilitating reduction in fuel consumption and emissions immediately and in the short-term (reduction potential ranging from 10-30% reduction), their lower need for significant extra capital, and the need to optimise operational efficiency before a switch to more expensive zero emission fuels (3).

The adoption of any new energy efficient protocols and adherence to these regulations however once in place, depends on the ship crew, whose limited autonomy of operations affecting fuel consumption is particularly compounded by long voyages away from management onshore as well as overriding commercial and safety considerations (4). A better understanding of the crew behaviour on board which directly impacts operational energy efficiency allows for policies to target emissions at the very front lines of shipping. The lack of understanding of the socio-technical factors contributing to operational energy efficiency has given rise to the call for more psychological and social studies within ship crews in the recent years.

Incentives schemes can be one of the ways to adapt the internal and external factors pertaining to the sociotechnical barriers of energy efficient operations. Perverse incentives are already woven into the market-driven framework of the shipping industry’s operational infrastructure, whereby energy efficiency measures such as “speed reduction” can be incentivised to the contrary due to different types of charter, which can demand speedy arrival times at the expense of fuel efficiency (5). Even if contracts were to prioritise saving fuel via reduced speed, the crew who are actualising the measures aligned with better fuel efficiency are not the ones who benefit from it, leading to split incentives and the energy efficiency gap —the difference between the potential and the actualisation of an energy efficiency measure, whereby those who would benefit from operational savings derived from fuel efficiency are neither actually operating those measures, nor are the ones who invested in those technologies and measures in the first place (6). For crew, formalising the role of energy efficiency driven incentive schemes, both monetary and non-monetary, may be a way to tackle this to fairly distribute to them the gains of their actions on fuel efficiency. However, ship owners who invest in fuel efficiency improving measures, including investments in crew training for energy efficiency, in general can’t recoup their investment, unless they operate their own ships or have long term agreements with charterers, because the charter rates of ships don’t reflect the economic benefit of its fuel efficiency (3).

This analysis, which constitutes interviews and surveys, aims to gain a deeper understanding of the practices amongst different stakeholders that influence a vessel’s operational efficiency; to understand the barriers to operational efficiency and subsequent areas for improvement, and what role incentives may play in the realisation of these improvements, which is an area in which there is little to no research in maritime transport sector. The findings are important against the background of the current climate policy in the shipping sector and the policies encouraging the uptake of energy efficiency. The paper aims to answer the following research questions:

1. Which operational practices/measures have the highest energy saving potential that can be undertaken by onboard crew without compromising safety and commercial objectives?

2. Is there a role for incentives in improving operational energy efficiency?

a.What are the current incentives and reward structures for improving performance and which ones are perceived to be most effective?

b.Which incentives and rewards are most preferred by crew in return for improving personal performance towards energy efficiency?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Energy Efficiency

2.1.1. Background

Although the definition of energy efficiency is adapted when in the context of different industries, it may be simpler to think of energy efficiency as the ratio between the useful output of a process and the energy being funnelled into it (7). In shipping, energy efficiency can be achieved in two ways: operational and technical. Operational efficiency is more dynamic, varying with fuel consumption and the operational conditions under which human factors have more consequence. This can be partially measured by the Energy Efficiency Operating Indicator (EEOI), a measure used to help shipowners assess the impact of operational modifications on the fuel economy and emissions of their ships. Operational efficiency relates to decisions made by the crew regarding measures such as trim and auxiliary engine optimisation, speed optimisation and weather routing (3). Technical efficiency refers to technical specifications such as engine modifications and equipment, which can be implemented at the ship building stage or as retrofits (8). The IMO’s regulatory measure, the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), and the targets they have attached to it help to make a ship more technically energy efficient.

The aforementioned goal-based fuel standards also mentioned in the revised IMO GHG strategy (2) have established themselves within shipping regulations with the goal of prioritising energy efficiency in shipping. However, although such regulation explicates the targets in place for the shipping industry, the transition pathway to meet these targets, such as the those for the EEOI or EEDI, are less clear. The practicalities, for example, involved in improving operational efficiency must be carried out by crew. However, the crew’s realistic dominion over these practices is complicated by their downstream position in the stakeholder network which reduces their autonomy in actualising energy efficient practices.

2.1.2. Stakeholder Network

The complex stakeholder structure of shipping is further complicated by the sea’s changing environment which necessitates a dynamic reactivity from the crew. However, the decisions on how a ship operates is made by various stakeholders onshore and at different operational and management hierarchies. These can be shipowners, operators and charterers for example concerned with the speed, and arrival time, or third party companies who offer technical support in the form of weather systems (9) Often, it may be the case that each of these agents operates with mutually exclusive goals (10) that may pre-empt certain decisions before they can be organically established (11–13). Jaferzadeh & Utne (2014) and Rehmatulla & Smith (2015) depict the interrelationship between these parties (3,12)

Some of the personal choices and incentives of stakeholders onshore are driven by the shipping company’s economic environment, which often in pursuit of cost efficiency exploit seafarers (14). Poulsen et al (2022) focus mainly on the decisions regarding voyage planning made in advance of the trip and the identities of these decision makers, who are then split into commercial and nautical (4) In their study, the destination of one cargo ship was unassigned post-departure due to the charterer’s deliberating between six ports during the voyage, meaning the crew had to run a “middle course” until a port was named (4). The fuel consumed while charting an uncertain distance is likely to then have adverse effects on the EEOI. Conversely, there are some instances where a crew's experience can override third party stakeholder input.

2.1.3. Operational Efficiency

Seafarers, when asked which known operational measures had the highest potential for Co2 emission reduction cited the following: fuel consumption monitoring, weather routing, speed reduction, crew awareness and training (16), the majority of which are in line with the literature on the operational measures with the highest GHG abatement potential (8,13,17) . Significant reduction in fuel consumption can be achieved by ‘slow steaming’ i.e. reducing the speed of a vessel (18). The dichotomy of the meaning of ‘optimal speed’ however remains, whereby it can either mean that which aligns with fuel efficiency and emissions most closely, or that which maximises profit (19). Speed reduction as an energy efficiency measure is therefore often where there is a split incentive and a clash between environmental and economic sustainability, both within an organisation and between organisations (20).

The IMO’s mandatory Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) can guide a crew’s best energy efficient practices, such as better voyage planning, weather routing, speed optimization, reduced power consumption, optimized ship handling, enhanced fleet management, and cargo handling (21,22) it is often the case that crew have not been involved in the development of a vessel’s SEEMP plan (22) and therefore it may be difficult for them to be aware of its benefits or they are not motivated implement the measures (21).

The SEEMP also does not isolate the effects of individual nautical and operational parameters on energy efficiency (23) which means that it is possible that individual practices cannot be targeted for change. A lack of awareness with SEEMP can be addressed with appreciation schemes and noncompliance consequences (21). However, one argument against these is a lack of widespread precise monitoring equipment onboard ships which can provide granular data to fully isolate the effects of crew behaviour on efficiency. This is increasingly possible through continuous monitoring data, however, as has been shown in the literature (37), the availability of such fine-grained data is not a necessary pre-requisite to incentivise crew behaviour. However any monitoring and rewarding of crew behaviour with incentives will require controlling external variables such as weather and this should be possible based on noon reports (37). Furthermore it can be argued that lack of precise fuel consumption data is less a valid argument against appreciation schemes and more for the creation and legitimisation of more fine-grained vessel performance data and real time energy consumption monitoring, a sentiment echoed by ship masters in multiple surveys (15,21,25). The International Seafarer’s Wellness Association Network (ISWAN) recent survey on seafarer’s challenges with decarbonisation, found that seafarers wanted to be “acknowledged and valorised, both in terms of renumeration and job security” for their contributions to decarbonisation. The validity of monitoring data sets did not appear in this report as a priority or obstacle for seafarers (26).

2.2. Incentives

Incentive schemes in shipping are mostly rooted at the organisational level, where shipping companies are incentivised to reduce pollution and accidents to improve water quality (27) . These incentive structures have extended to energy efficiency in shipping, such as the implementation of lower port dues for vessels which score highly on the environmental Ship index (ESI) (28) however, personal incentives for crew within the ship environment are less known, this being an area where there is almost no research pertaining to shipping specifically.

The principal agent problem, derived from the Theory of the Firm (29) whereby a delegation of a task from a principal to the agent—accompanied by a granted capacity to the latter to perform said task— is nuanced with the conflicting interests of, and asymmetry of information between two parties. In shipping, this can be called a split-incentive (30). A common example of the split incentive problem is where one who must invest and implement the energy efficiency measure is not the one benefiting from the improvement in energy efficiency e.g. a time charterer who benefits from reduced fuel consumption when a shipowner invests in technical energy efficiency. Blumstein et al (1980), refers to these as landlord-tenant problems (31,32). Johnson et al (3) further highlight the importance of identifying or creating personal incentives for “investing” in energy efficiency, where investing extends to even day-to day activities which could nurture individual personal accountability for energy efficiency (31). Realising incentive structures for propagating energy efficient behaviours could both invest and empower crew in their role as agents of energy efficient shipping (31).

There are four types of incentive schemes: (a) cost incentives, (b) schedule incentives, (c) performance incentives, and (d) safety incentives (33,34), and the manner in which these can be delivered can be monetary or non-monetary (35,36)). Incentive schemes can retain an employee by boosting their satisfaction and compensate and improve their performance through the theory of expectancy, which predicts that individuals will make conscious choices (such as improving their performance to meet incentive-driven targets) in order to maximise their gain (further incentives) (35). It has also been shown that in addition to improving job performance, contractual incentives can result in a better alignment of owner and contractor objectives (36). It is possible that this may address the issue of split-incentives in complex chain of stakeholder relationships. The impact of incentives on crew’s energy efficiency in shipping has to date not been widely researched. However, treatments applied in other transport sectors, such as aviation and road freight, as shown below, can be useful to understand their impact on behaviour.

In their field experiment in partnership with Virgin Atlantic airways, Gosnell et al (37) used firm level incentives for workers as a pathway towards nurturing energy efficient behaviours over a 27-month period (37). The impact of three treatments on the fuel efficiency behaviours of captains were measured: personalized information (on fuel consumption), performance targets (on fuel consumption and other measures implemented), and prosocial incentives. Results relevant to this study stated that the inclusion of personalized targets increases captains’ implementation of their three measured behaviours: performance reports sent to captains, personal targets in addition to performance reports, and prosocial incentives such as charity donations subject to meeting targets. Overall, the effects for all three behaviours were statistically significantly different from the study’s control group for nearly every behaviour-treatment combination (37).

In the road freight transport sector, up to 91% of total trucking fuel consumption in the U.S. is affected by “usage” principal agent problems, where the driver does not pay fuel costs and lacks incentive for fuel saving operation (38). In a study focusing on light commercial vehicle drivers in a logistics company fleet, comparing the significance of monetary vs non-monetary incentives on fuel efficiency and eco-driving, participants in the non-monetary group exhibited a much higher reduction in average fuel consumption than the monetary treatment group (39). In this study, non-monetary incentives included vouchers in the same value as the monetary treatment for attending wellness activities such as the cinema. The same phenomenon was exhibited when comparing monetary and non-monetary incentives for energy conservation in a Dutch firm as well as a trucking company in Norway, with public and social rewards outperforming monetary rewards, even if monetary rewards were initially perceived as more popular with the workers (40,41).

In the discussion of non-monetary and monetary incentives, it must be postulated whether the existence of monetary incentives as extrinsic motivation creates a habit of perverse financially driven practices which ruin intrinsic motivation, often known as the “motivation crowding effect” (42). In shipping, seafarers' personal pride when it comes to energy efficiency, and the impact of incentivising performance via extrinsic measures, must be considered. However, Deci & Ryan’s cognitive evaluation theory (43) predicts that “rewards only reduce intrinsic motivation when they are perceived as controlling the behaviour” (44). Even when they do reduce intrinsic motivation, the factors contributing to this are not well understood (44). However, the possibility of perverse incentives is not an argument against exploring incentive schemes in shipping, especially given their efficacy in other transport sectors such as aviation and road freight, but more so highlights the importance of carefully constructed incentive structures which minimise perverse incentivisation. This analysis, is the first to focus incentives for maritime crew to energy efficiency in shipping, aims to shed light on its role in the maritime transport sector. (37)

3. Methods

Qualitative research in the form of semi-structured, in-depth interviews was deemed most suitable for an initial exploration that helped to meet the aforementioned aims. Twenty-five in-depth interviews were undertaken with nine captains, eight chief engineers and five operators, one technical manager and two policy experts (with seafaring experience), from a diverse range of shipping companies and sectors (tanker, drybulk and ferries) mostly headquartered in Europe with international operations.

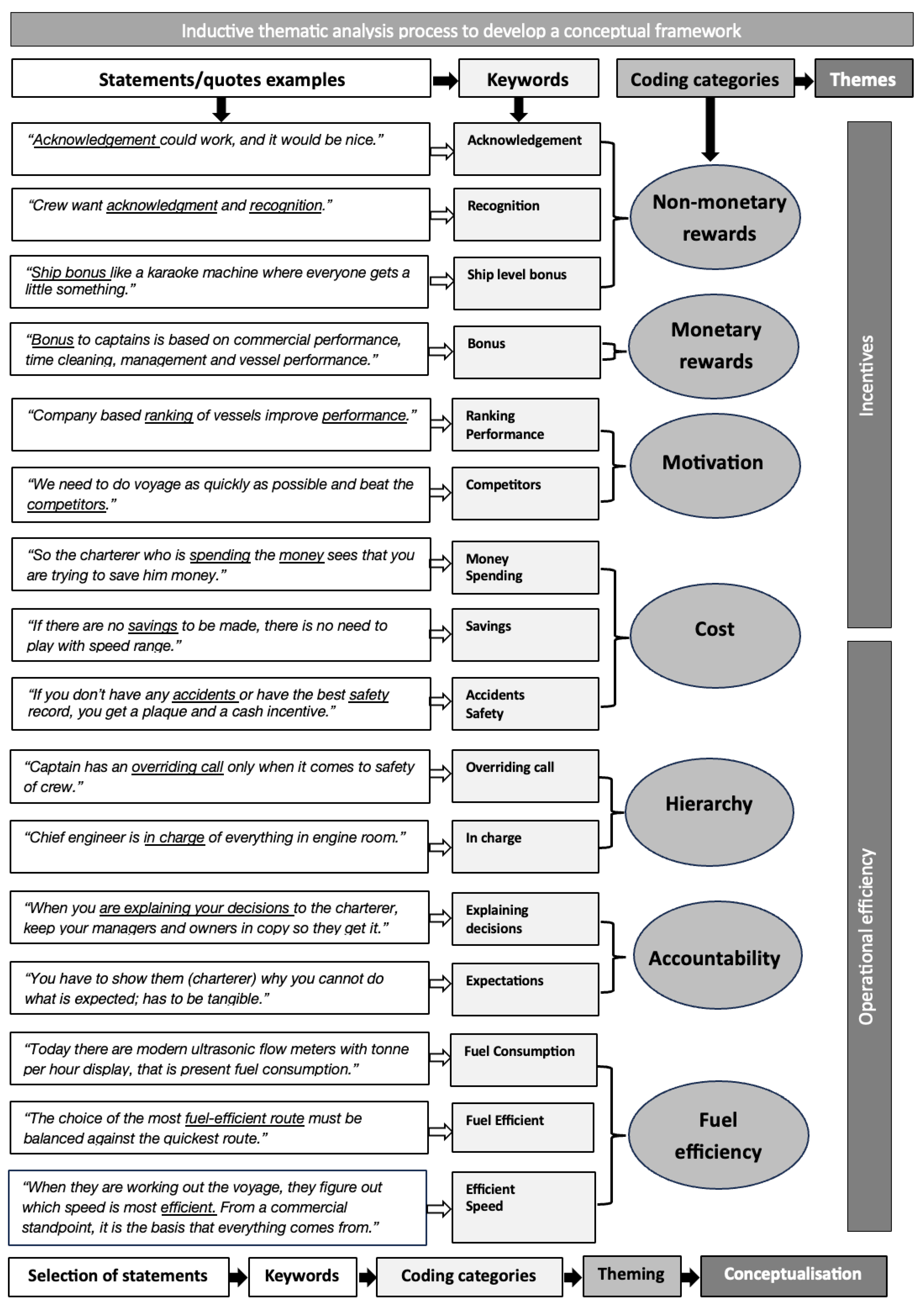

As per Braun and Clarke (2006) the study divided the analysis into two separate ‘global themes’: operational measures and incentives (45). Within each one of these global themes, various ‘organising themes’ were defined, that effectively organised the individual findings into relevant categories. Where relevant, basic themes are supported with direct (and anonymised) quotes from our interviewees.

The use of interviews and subsequent surveys is based on recommendations to use diverse array of methods to investigate underexplored or new subject areas (46). The study employs a sequential exploratory design, starting with a qualitative interview which builds on to quantitative survey. Qualitative data provides the opportunity to explore barriers from the respondents’ perspective, allowing them to control the narrative as opposed to a questionnaire which limits them in their answers (22). Individual interviews are also a frequently used data collection (47) and have previously been used in other studies focusing on seafarer perspectives on energy efficiency (37)

Online surveys allow "rapid turnaround in data collection” which allows cross sectional collection and analysis and is not human resource heavy (48). Qualitative data in the interviews is supplemented by quantitative data from surveys, which were undertaken due to heterogeneity in interview responses on the topic of incentives. This quantitative data is retained to allow for a general quantification of seafarer priorities and perceptions when it came to incentives and to identify any patterns in their ranking of given options. No statistical tests have been applied to this data due to the small sample size (n=42) and because it is first important to understand the data thoroughly through descriptive analysis. -

Whilst the focus of the research is onboard energy efficiency and the role of incentives in its optimisation, there are two reasons for including shore-based staff in the interviews; to corroborate the statements of onboard crew and to identify the limits and orders placed by shore-based staff on the commercial aspects of the voyage. Each interview built on the understanding gained from the previous ones, and some key conclusions emerged. The respondent demographics are presented in

Table 1 and the interview guide can be found in the . The interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. A theory driven thematic analysis was applied to the transcribed data via an adapted model recommended by Naeem et al (2023) (50) (

Figure 1).

The lack of consensus and heterogeneity in responses when it came to the subject of incentives warranted a further exploration and online ‘anonymous’ self-administered surveys were deemed most suitable as they would circumvent any potential interview bias, we potentially faced during the interviews, especially around perception of incentives. The online survey was designed using the Tailored Design Method (TDM) guidelines (51) distributed through the authors networks and garnered 42 responses over a period of 3 weeks (refer to appendix for full list of questions)

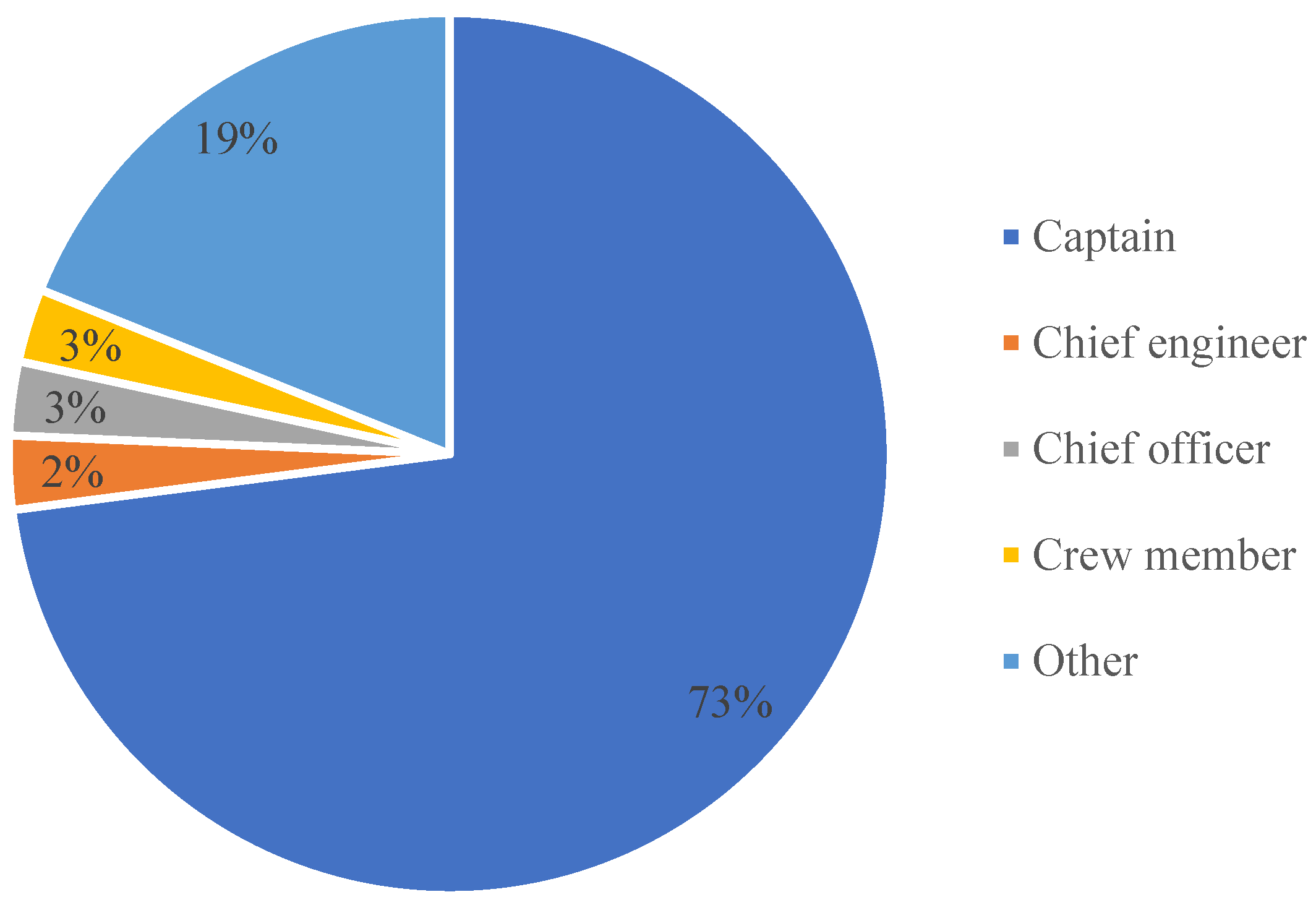

. The respondent demographics are presented in

Figure 2,

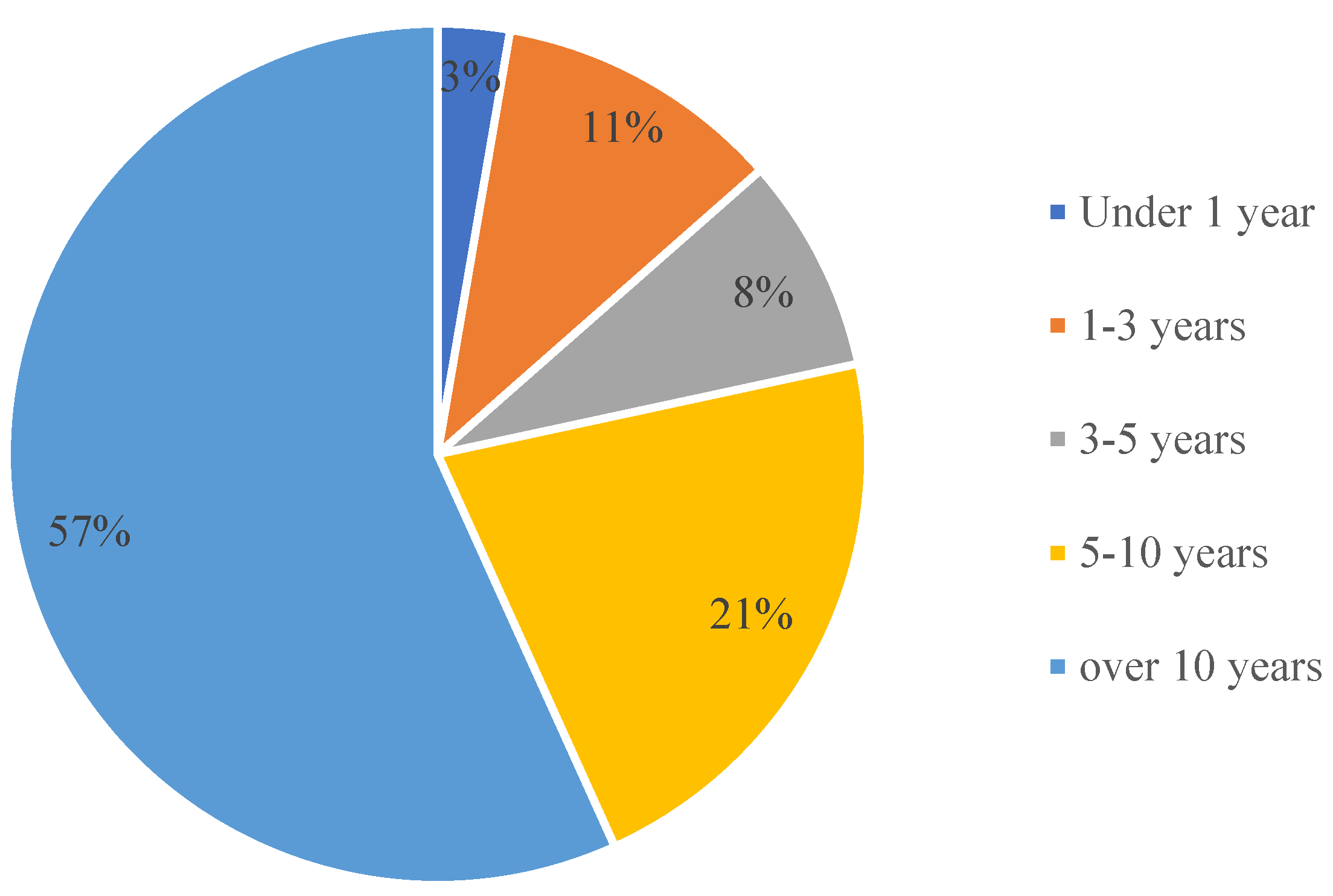

Figure 3 and

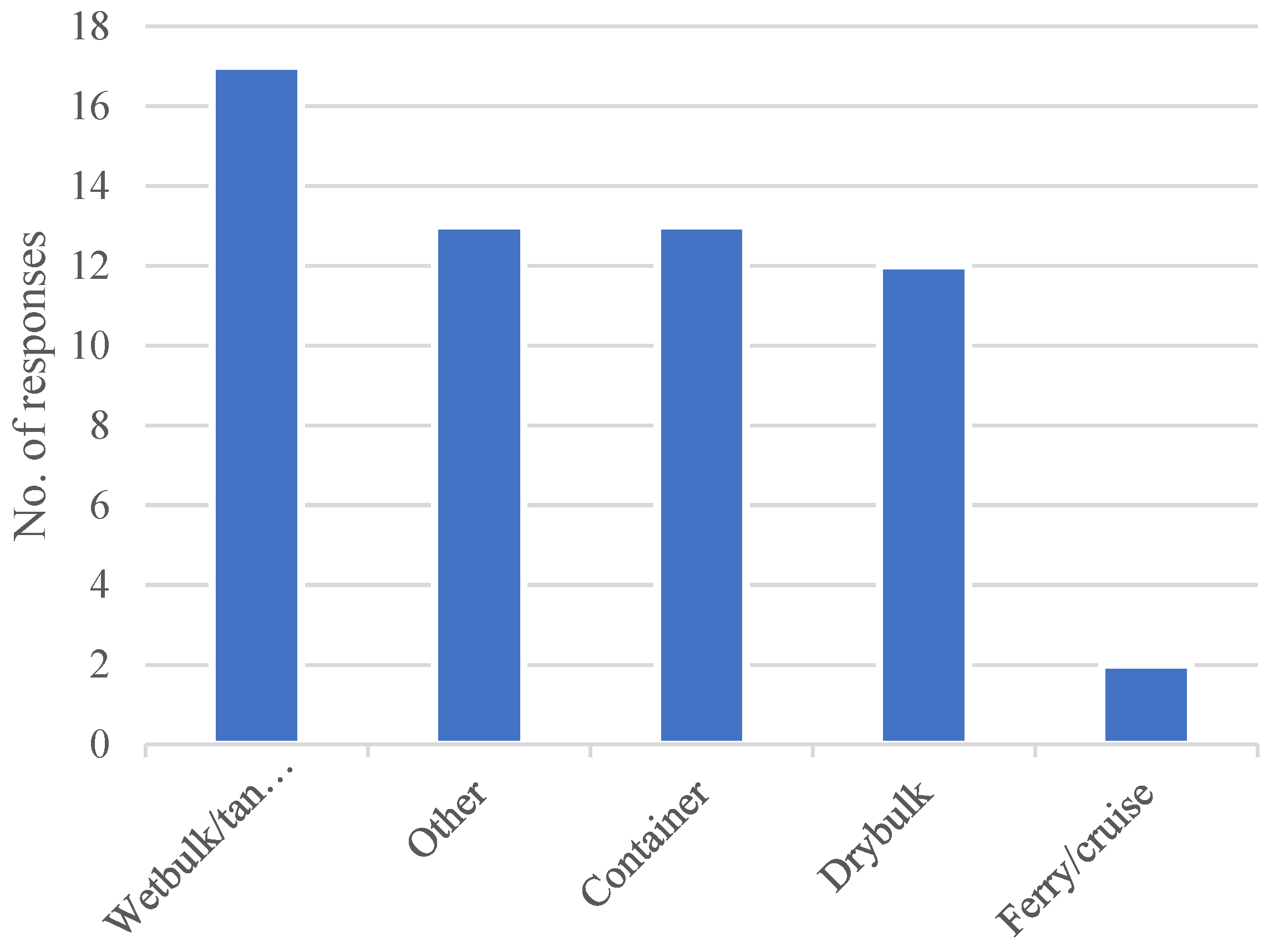

Figure 4. Note the totals do not reach 42 due to non-responses in the demographic questions and this is expected because TDM guidelines suggest including demographic questions at the end and not forcing responses, in order to overcome survey attrition and increase total response size

. Figure 2 shows most responses were from captains who were the target sample, and the majority had over ten years’ service with their current company (

Figure 3). Other respondents included superintendents and operations staff ashore. In terms of the sector coverage there was good representation across the sectors and the other category included respondents from offshore oil and gas and car carriers (note responses exceed the number of respondents as multiple responses were allowed). The survey consisted of questions around motivations, rewards and incentives

. The aim of the survey was exploratory

, and not to obtain statistically significant results, therefore the response rate achieved was deemed appropriate.

4. Results

After conducting interviews and surveys, the data revealed a number of new insights in the behaviour and operational practices of shore based and onboard crew around operational measures and perception of incentives.

4.1. Operational Measures

4.1.1. Speed Reduction

In almost all interviews, speed as an energy saving measure was brought up by the interviewees without requiring any prompts. Speed forms the basis for determining efficiency:

“From a commercial standpoint, it is the basis that everything comes from. When they are working out the voyage, they figure out which speed is most efficient.” Q-POL

Speed is closely related to, and influences fuel consumption:

“Speed is controlled by the engine department based on the fuel ceiling.” G-ENG

Decisions around optimising speed can also be driven by savings:

“If there are no savings to be made, there is no need to play with speed range.” X-ENG

The interviews confirmed that the captain and chief engineer are key entities pertaining to operational efficiency, especially around speed reduction. However, maximising energy efficiency through speed reduction requires a degree of autonomy which seems to be limited due to the charterparty’s overarching influence on operational decisions, which often considers market conditions as well.

“Market conditions sometimes mean speed would be higher” (A-OP).

Any deviations from their pre and in-voyage imposed orders must be justified to the charterer by the captain:

“There is a choice, as long as there is a justification.” (G-ENG).

The margins of manoeuvring with some autonomy are minute. An example of this is the deviation allowances of present voyage speeds being as small as “Plus or minus 0.5 knots”.

“You can get away with half a knot” (B-CAP).

However despite this allowance interviewees felt that in practice it was difficult to take this as an opportunity to reduce fuel consumption. The only cases in which these prerequisites can be overridden are for safety reasons:

“Permitted deviation, when something goes wrong.” (F-CAP).

The complex web of accountability makes it such that some of the autonomy on operational measures are dependent on charter party instructions, how well the cargo receivers are prepared, what the owners prefer:

“When you are explaining your decisions to the charter party, also keep your managers and owners in copy so they get it.”D-OP

Other measures that were mentioned and discussed below included weather routing, trim draft optimisation and improving auxiliary engine loads.

4.1.2. Weather Routing

In terms of the energy saving potential of weather routing, the interviewees considered it to be of importance (after speed reduction) but as with speed reduction, highlighted several barriers that hinder its implementation. On one hand, the autonomy of the ship master with regards to weather routing was said to be limited by the risk of not meeting expected time of arrival (ETA).

“There is little autonomy with weather routing” (K-CAP)

“Speed reduction is based on expected time (ET) requirement” (N-CAP).

“The charter party does not take into account currents” (A-OP).

There is also a lack of trust as there are varied levels of certainty on the weather conditions assumed to deliver savings and rule of thumbs which was cited by several captains e.g. sailing on previously calm/safe routes:

“The choice of most fuel-efficient route must be balanced against the safest route and quickest route” (U-CAP).

Captains are not only exposed to strict instructions from the charter, but also from secondary authorities such as meteorological experts for weather routing. Weather routing suggestions can be at odds with judgements made by key decision makers on the vessel:

“Meteorological don’t know what’s happening on the ground but people on the vessel know” (M-CAP).

However, this restricted autonomy was questioned in one interview with an engineer: The master has the overriding authority to follow or not to follow the recommendation from the weather routing companies. If they don't agree, the final word is with the master, because he’s responsible for the safety.” I-ENG

4.1.3. Auxiliary Engines Load Optimisation

Auxiliary engines generate power for non-propulsive energy required onboard including electricity for lighting and heating, cargo/crane functions, pressure systems, etc. The interviews confirmed that many vessels run more auxiliary engines simultaneously than is required by the vessel.

“Ideally, we don’t have to be running more than 1 aux engine. However, because engines are not performing, the crew may be forced to run both engines which may cause consumption to hit the roof.” S-ENG

“Generally I feel auxiliary engine consumption gets overlooked, especially from the operator side.”

Further insight into the deciding body of this behaviour came from: P-OP, who reveals that the chief engineer is an important entity when it comes to operational measures like the auxiliary engine:

“Chief engineer is in charge of everything in engine room.” P-OP

There is an awareness onboard that that personal usage of electricity can influence fuel consumption as well and that therein lies room for optimisation:

“AC load, blower, lights on board, cooking, electricity use when it comes to the meat room, fish room and veg room…what should I set my thermostat at? Optimising there can be done.” J.ENG.

4.1.5. Trim Draft Optimisation

Another measure that was consistently mentioned by the interviewees of having potential for improvement was trim draft optimisation. A vessel’s hull is designed and optimized for the fully loaded condition, therefore the trim that is optimal for a vessel under the different conditions would vary. Trim can be improved by arranging bunkers, by positioning cargo or by varying the amount of ballast water, which will affect displacement and resistance and thus have a direct impact on fuel consumption. There are also other ship specific and voyage related factors that also contribute towards optimal trim such as operation difficulties, lack of awareness of ship crews and lack of information (25). In order to compute the effect of these variables, software packages/decision support systems can analyse and facilitate counter measures. Trim tables play a key role within the trim draft optimization measure.

“Trim is used to improve performance.” A-OP.

The interviews confirmed the effectiveness of this measure requires agreement and cooperation from the whole crew onboard, especially between the deck, cargo handling and the engine room teams. This measure is also where the discrepancies in beliefs also lie and there is a need for individually tailored systems for each vessel’s operational profile. However, trim optimisation wasn’t readily available for all respondents:

“Don’t currently have it but it’s in the plan.” P-OP

4.1.6. Fuel Consumption Monitoring Systems

There is some variability in the degree to which operational efficiencies are optimised using ‘tools’ from one company to another. Although it appears that crew are keen to save fuel using tools as this also cuts costs, the new technology required to monitor this would come with an expectation of quick savings:

“After three months you’re going to be asked how much you’ve saved with the system” (B-CAP).

Any system therefore which manages operational measures e.g. weather routing software, autopilot adjustments and trim draft optimisation were some examples in our interviews, must be “user friendly” as a requirement (A-OP).

Interviewees, admit that while noon reports are important, more modern tools, such as “ultrasonic flow measures that measure volume” would allow for more continuous monitoring (See

Figure 5).

“A tonnes per hour display would allow for better optimisation of operational measures: (B-CAP).

“Today, there are modern ultrasonic flow meters that measure volume…so it could give you a ton per hour display…this is present fuel consumption.” Y-OP

Even within a company that provides tools, there is variation in the degree to which such tools are adopted:

“Some captains pay no attention to some of these tools.” U-CAP

4.2. Incentives

4.2.1. Perception of Incentives

Incentives proved to be the topic where there was significant variation in the interview responses. The question on what respondents would like to see as incentives for improved performance on energy efficiency was met with a lot of hesitation by the respondents. This is why we attempted to supplement interview data with surveys in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of interviewee responses. For example, in the interviews, some respondents claimed that there was not an explicit need to reward positive behaviour with incentives in the matter of energy efficiency because it was:

“Part of the job description…everyone is a part of saving.” (M-CAP).

Others in the interviews highlighted that there were:

“Company-based rankings of the vessel” (W-CAP

), which was enough of an incentive to improve performance

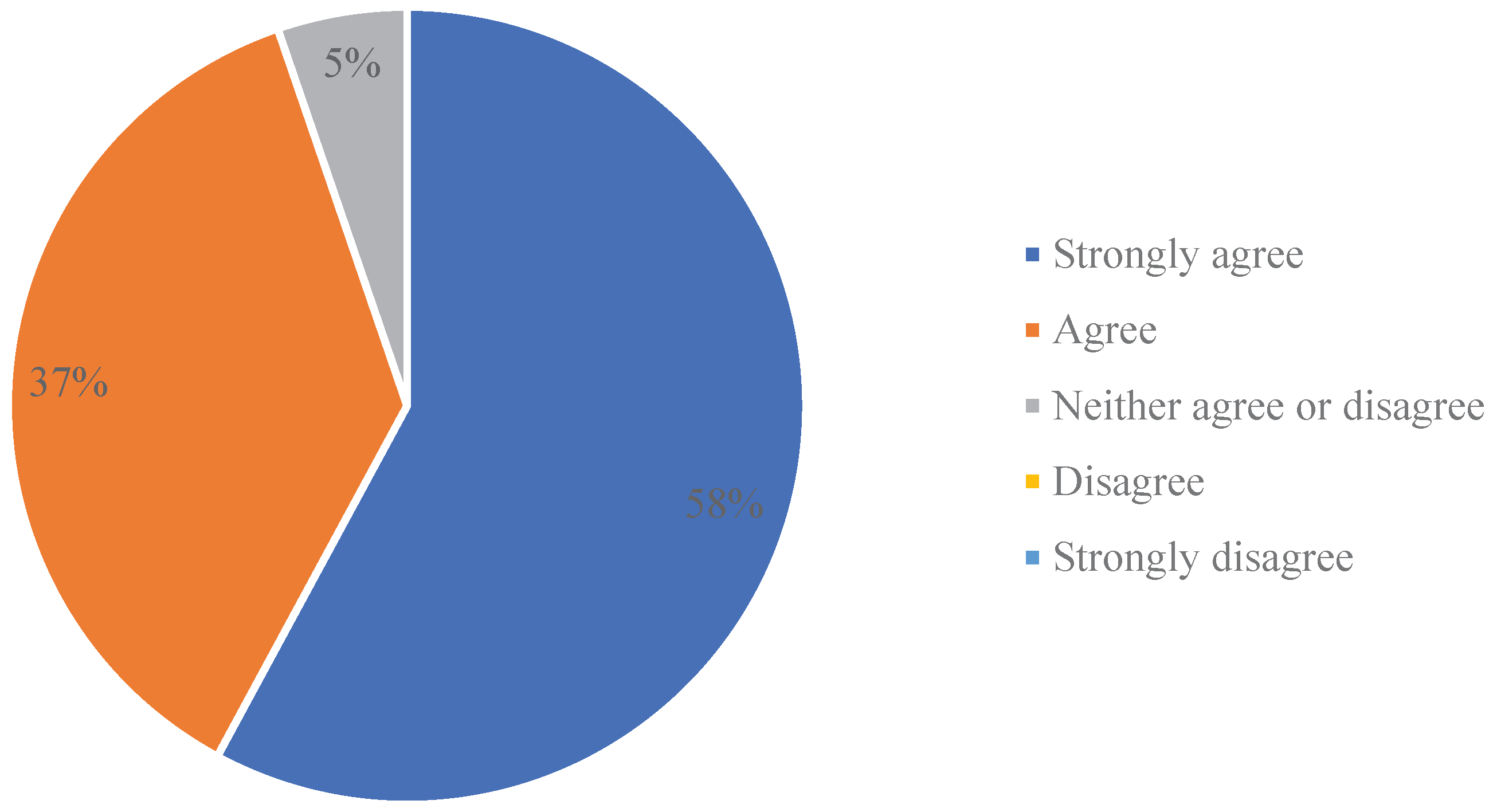

. However, in the surveys, the majority of the respondents thought that they should be rewarded over and above their salaries for good performance (

Figure 6), with 58% of respondents believing that individuals should be rewarded over and above their salary for good performance on their jobs. No respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, which suggests rewards and incentives for good performance should be explored further.

Direct cash incentives or in-kind e.g. business class flights, were preferred by some respondents while others argued that this should be avoided as it could diminish returns of the company and the bonuses for all staff and for creating a culture of staff being accustomed to incentives to drive good performance:

“Incentives taken for granted... must be careful in their design” (L-CAP).

Competition with other ships was also cited by one captain as an incentive for efficiency:

“We need to do the voyage as efficiently and beat the competitors” (M-CAP),

However, one captain deemed it as unhealthy and mentioned:

“Perverse incentive of competition, should not incentivise unsafe operations” (K-CAP).

4.2.2. Incentives for Fuel Efficiency

Despite this significant heterogeneity of opinion regarding incentives, there was agreement in the interviews that no specific incentives are in place for fuel efficiency.

“We are not really rewarded for fuel efficiency” (U-CAP).

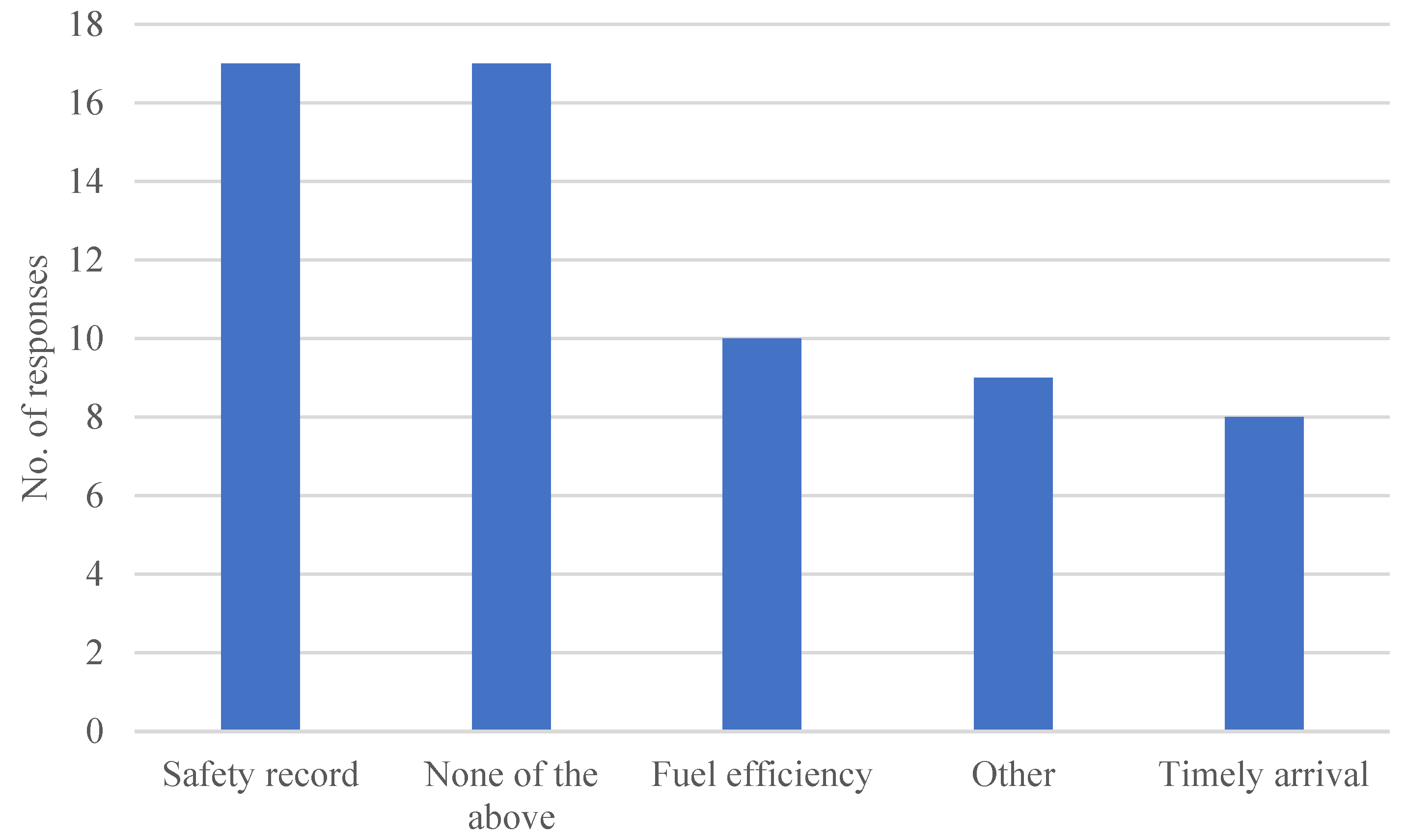

This contradicts survey data where a minority of respondents reported being rewarded for fuel efficiency (

Figure 7). The survey results do show however that crew and captains are aware and do receive incentives for other key performance indicators such as safety as shown in

Figure 7. Other responses from the survey showed that some received rewards for cargo handling operations, optimising maintenance schedules and following successful vetting/inspections.

4.2.3. Distribution of Incentives

Captains are most commonly incentivised for good performance, with direct cash or annual bonuses forming the bulk of their incentives. Regarding the captain’s monopoly on monetary incentives, interviewees were at odds, with some feeling that this should at least be shared with the chief engineer, while others wanted a ship-wide distribution.

“Bonus to master and crew should be considered; for e.g. a cash bonus.” (Y-OP)

“Ship bonus like a karaoke machine where everyone gets a little something.” (R-ENG)

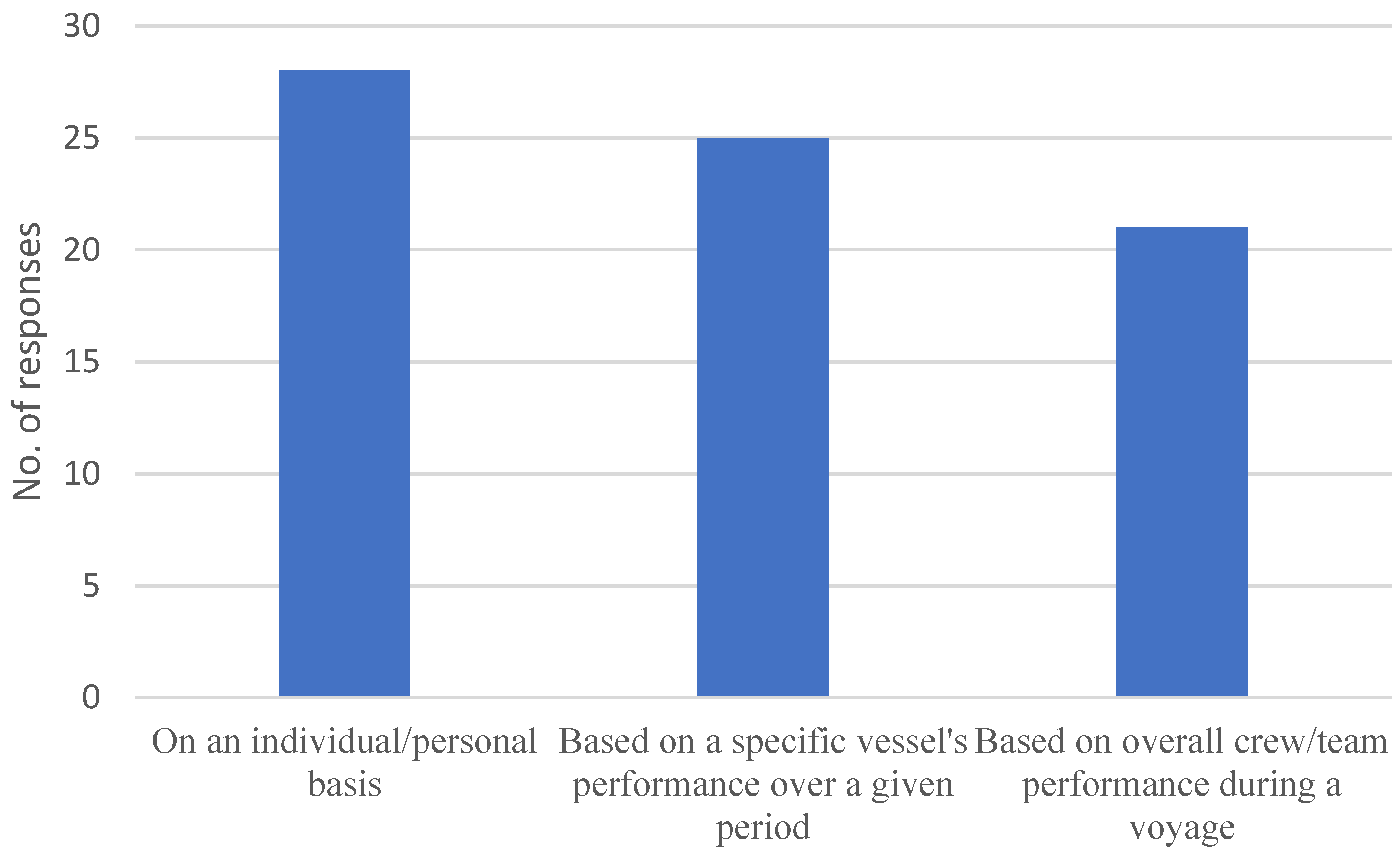

Survey results confirmed this view on equitable distribution, with 59% of responses preferring rewards should be tied to performance beyond the individual (i.e. team and vessel performance) (

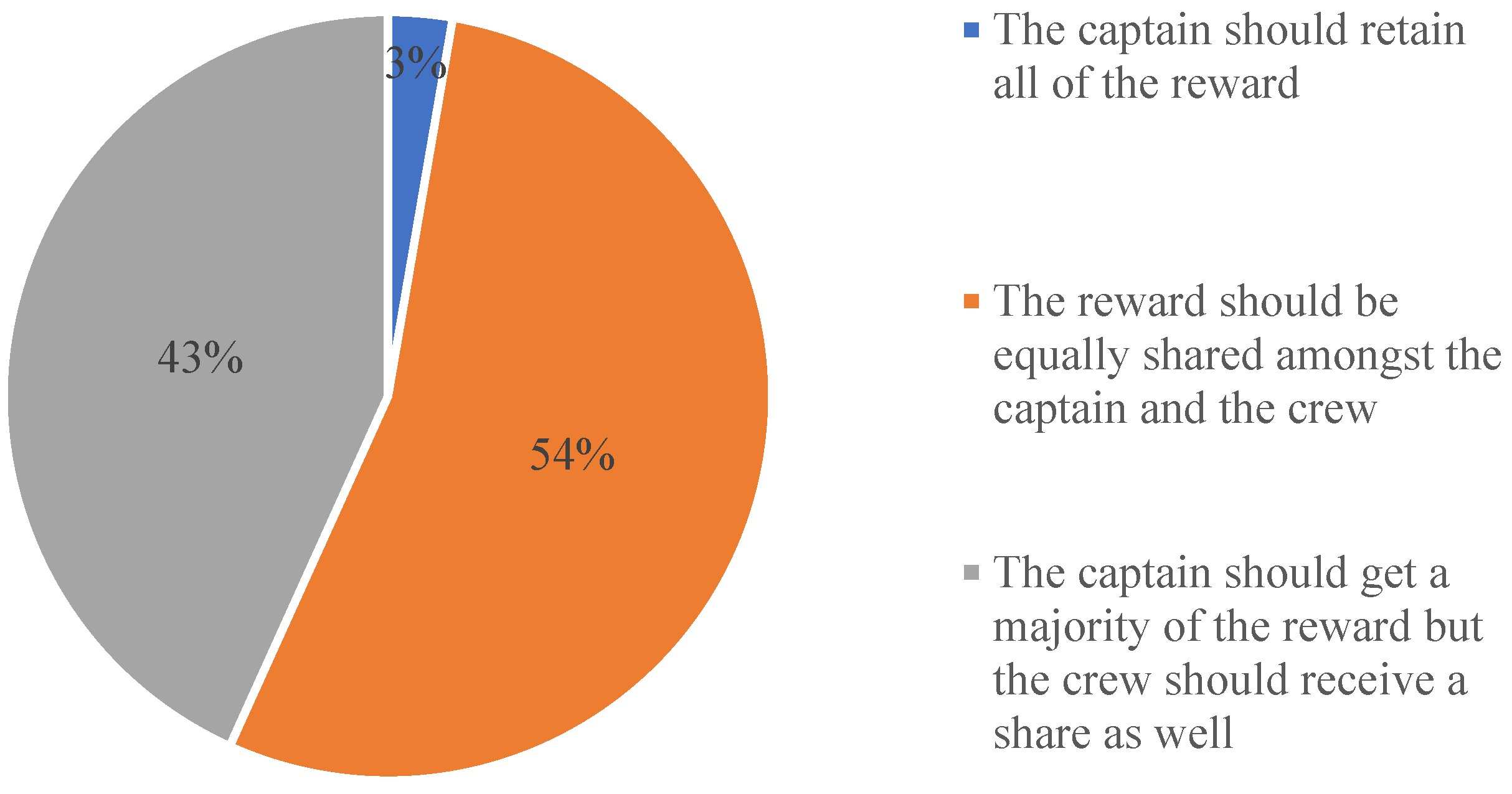

Figure 8). (note the results are not cumulative because the question allowed for multiple responses). Specifically on rewards for fuel efficiency, 54% of respondents remained in favour of sharing equally between the captain and the crew (

Figure 9).

4.2.4. Incentive Categories

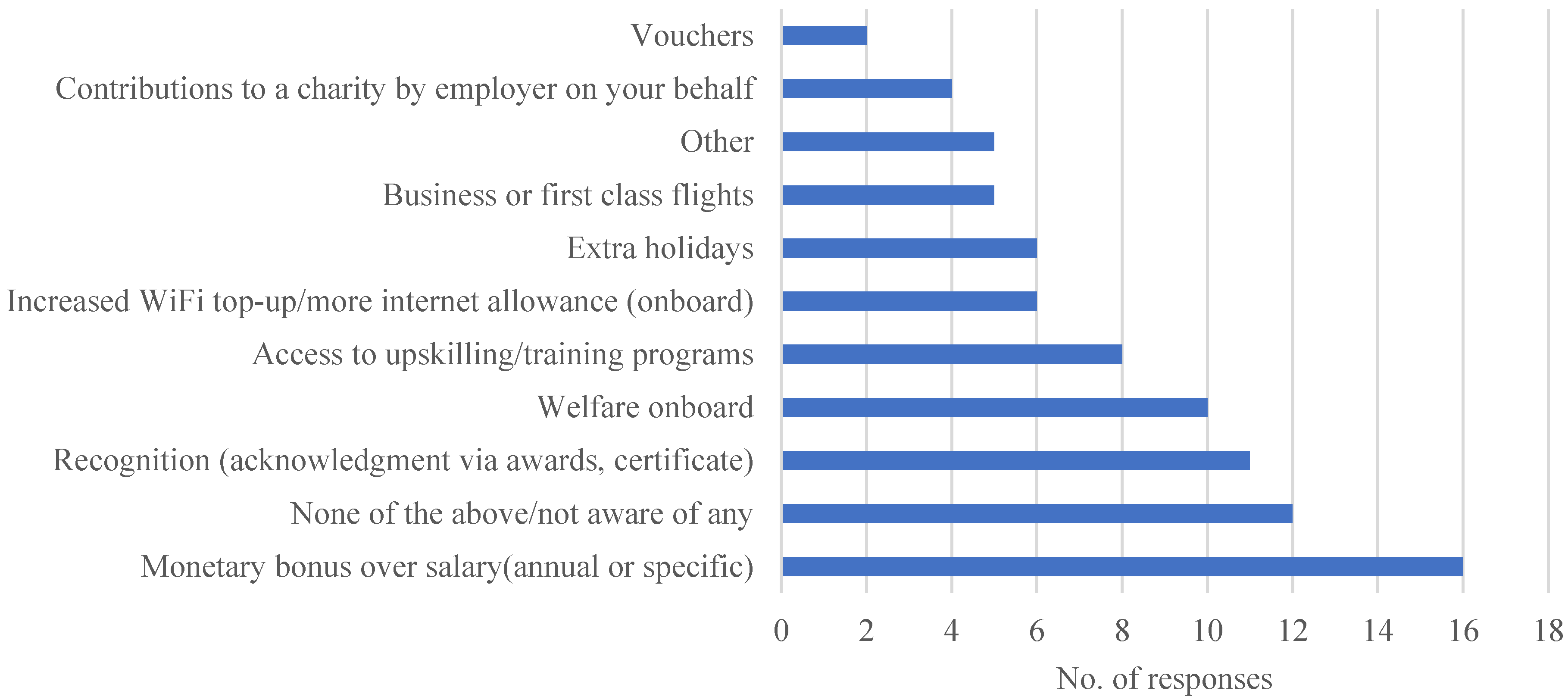

Monetary and annual bonuses were the most commonly preferred incentives for improving performance in interviews, which matches survey data, with monetary incentives being the most administered , followed by recognition and welfare onboard and the least commonly administered rewards were vouchers and pro-social incentives (

Figure 10).The priority of provision of these by the company, as well as the performance rewards offered specifically for the interviewed roles relatively matched worker preference, with monetary bonuses over salary, welfare onboard, and recognition constituting three out of the four topmost commonly reported incentives. However 14% of respondents were not aware of any rewards, meaning that there is a faction of workers working with no additional incentives or not aware of incentive structures in their company. This was the second most picked option after monetary rewards (

Figure 10).

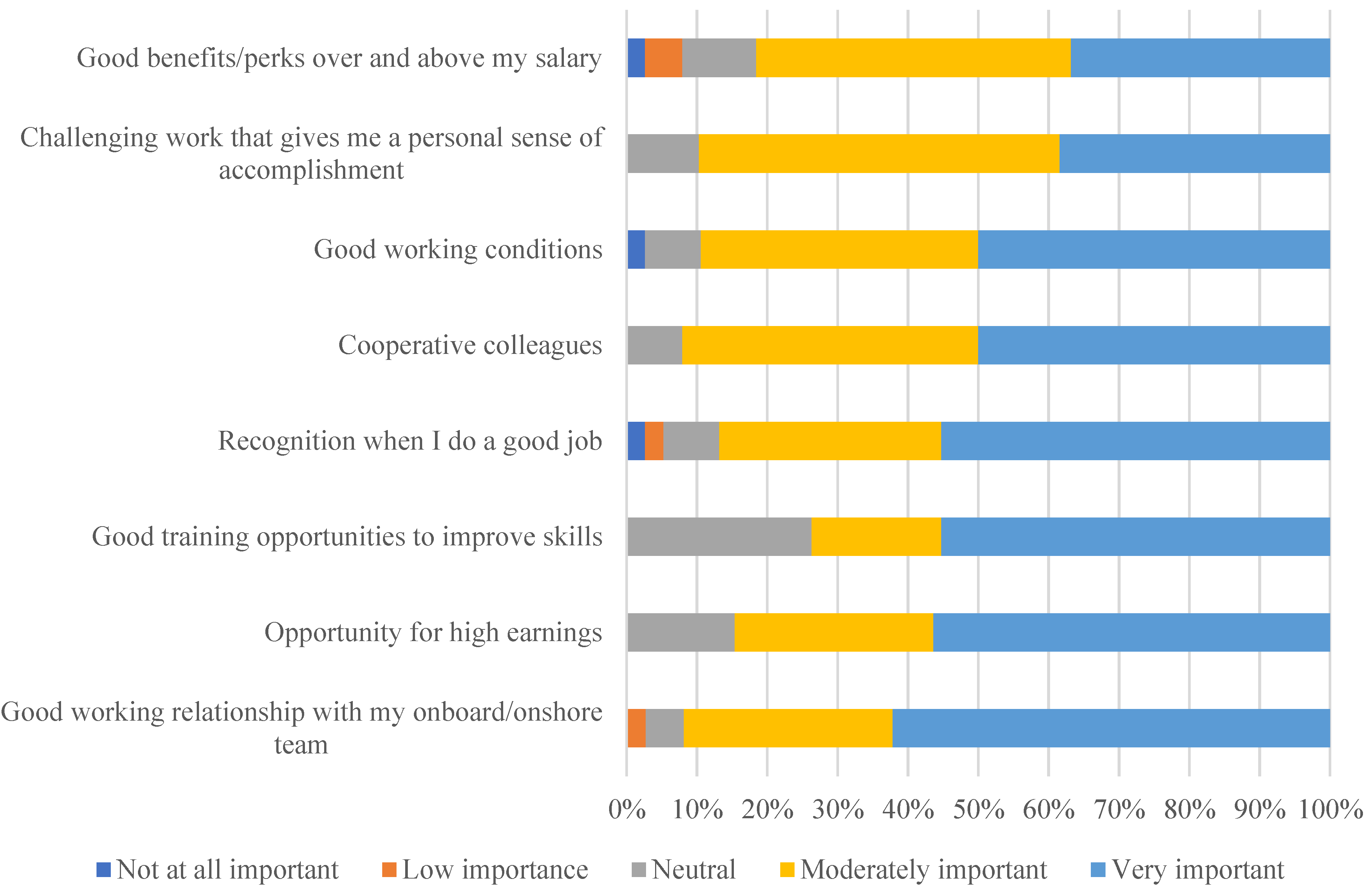

In terms of what factors would improve job motivation on a 1-5 Likert scale, with 5 being “very much” and 1 being “not at all”, recognition and upskilling opportunities were valued more than perks and benefits, which may open the path for non-monetary incentives, of which access to training programs, welfare onboard and recognition followed secondary preferences (

Figure 11).

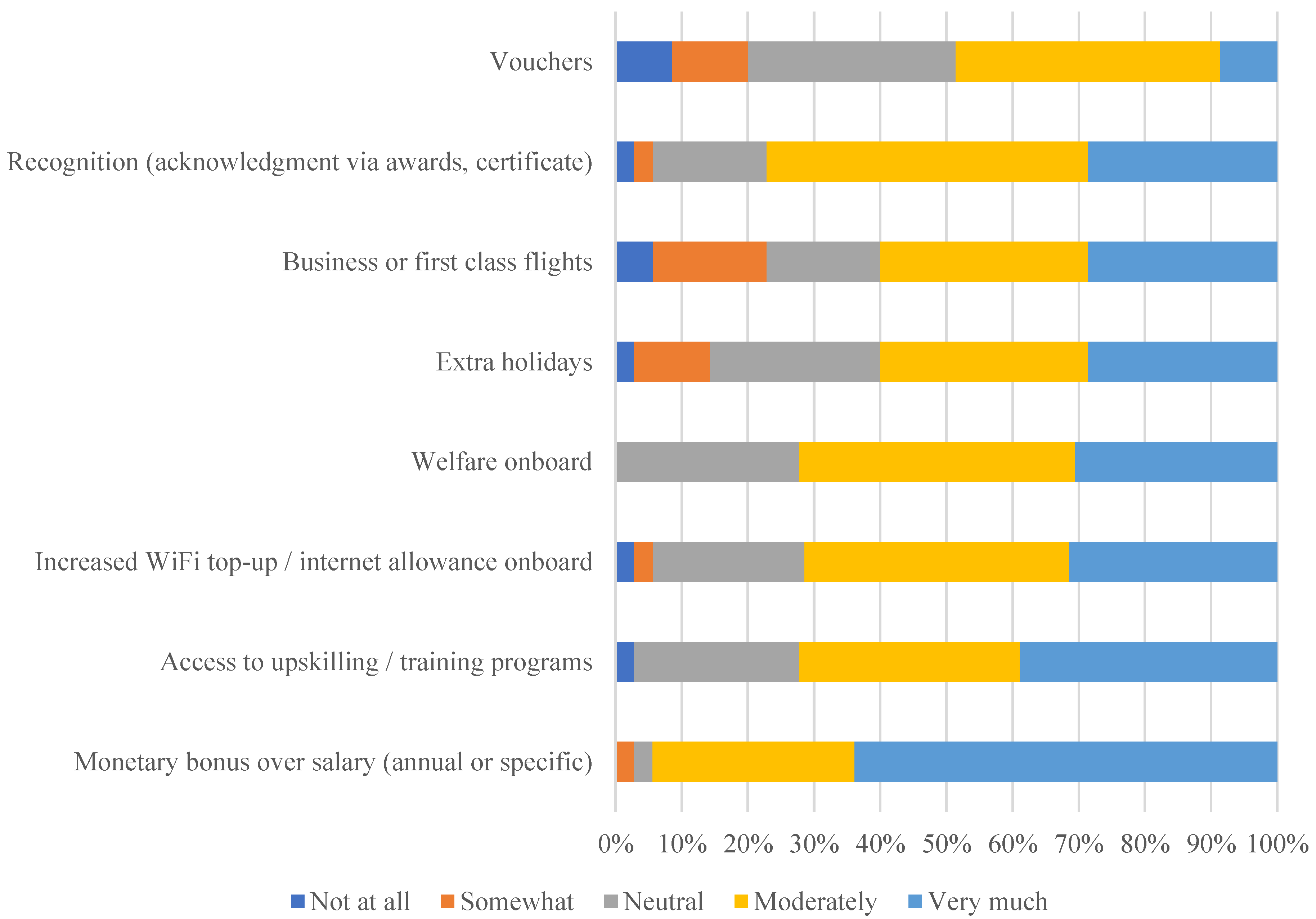

Unsurprisingly, in response to the question

“How much would the following performance rewards motivate you to improve your performance” with 1 being not at all, and 5 being very much,

‘monetary bonus over salary

’ again were most preferred by respondents followed by access to training programs and upskilling (

Figure 12).

Recognition as a non-monetary incentive was mentioned the most frequently in response to: “What do crew want?” in interviews:

“Acknowledgment and recognition.” (U-CAP).

The same captain also commented that he has found this acknowledgment more easily in companies with fewer employees as he was in:

“...the same rotation in the same ship, same colleagues.” (U-CAP).

Another captain supplemented this by specifying that this acknowledgement could specifically be catered towards operational efficiency:

“... as per per indicators such as EEOI” (K-CAP).

To correlate with survey data, first class flights were reported as existing reward schemes by 5.9 % of respondents, while welfare onboard was reported by 11.8% (

Figure 8). Hybrid non

-monetary incentives were also cited as attractive options

:

“First class return flights...generally the meals on the ship are good” (K-CAP)

“I’ve been offered upgraded flights home...” (A-OP)

“Feel good, being cared for e.g. meals (F-CAP)

“Free internet provision to the crew onboard could also be provided as a reward (W-CAP)

5. Discussion

5.1. Operational Measures

Our study finds that although the crew does have autonomy in operational measures, particularly the chief engineer, the limits of this rely on the ability to justify any deviances from charter instructions to the charter party and managers, and their distance from the decision-making hubs which control the recourses to implement energy efficiency processes. Speed is the operational measure most closely related to fuel consumption, and this is decided by market conditions, cost, and fuel consumption ceilings. Other measures include auxiliary engine load, trim draft optimisation, weather routing, and fuel consumption monitoring, the use of which is determined primarily by the chief engineer and sometimes captain. With regards to incentivising green behaviours, monetary rewards were most popular and it was believed that this should be shared with a larger proportion of the crew and not only the captain. Fuel efficiency was infrequently incentivised, while safety was the most incentivised behaviour.

5.1.1. Speed

The interviews helped with creating a shortlist of operational efficiency measures or interventions that can be targeted for improvement. Speed reduction was deemed to have the most energy saving, which is validated by other data confirming an 18% net reduction in Co2 emissions alone which could be achieved by slow steaming (8) but there was a limited range for further improvement due complex accountability, contractual constraints and even perverse incentives to increase speed such as:

I) speeding up to gain demurrage income

ii) speeding up to tender Notice of Readiness (NOR) to avoid the risk of tendering NOR outside the stipulated charterparty times/port times

Slow steaming or using information from fuel meters to adjust speed is also limited by predefined speeds in the charter contracts, which may demotivate crew to implement any energy efficiency initiatives (24).

5.1.2. Auxiliary Engine Load Optimisation

Following speed, the operational measure that was deemed most significant was auxiliary engine optimization, a measure over which crew, particularly the chief engineer has almost total control over, without the need for any additional capital investment. The interviews confirmed that many vessels run more auxiliary engines simultaneously than is required by the vessel. This is related to risk aversion of black-out, i.e. the only running auxiliary engine dropping out and to provide a safety margin against black-out and at times adhering to manufacturer guidelines (53). There is also a perverse incentive of turning on auxiliary engines and boilers well in advance of the required need to make sure that they are ready. In Hansen et al’s 2020 study, it is said that offshore sites claim a distance of 500 m as a ‘safety zone’ where vessels entering this zone must meet certain safety standards: ‘We have everything up and running […] we must be sure […] that we have enough power to get away’ (Navigator) (22). Although in other studies some tanker engineers are prepared to turn off engines between uses, they admit that safety will always come first. In addition to the significant energy saving potential of up to 20% per auxiliary engine (17), where safety permits, lowering the number of auxiliary engines in use where safety permits would also lead to monetary savings as a result of reduced engine hours, the rate of wear and tear per hour, lubrication oil consumption and consequently work needed to do maintenance.

There is an awareness onboard that personal usage of electricity can influence fuel consumption as well and that therein lies room for optimisation. This mirrors the sentiments of an interviewee in Hammander et al’s 2015 study who is aware that the use of paper dishes in dinners is against the ship’s International Organization for Standardization’s certification, awarded to ships which minimise their operation’s negative impact on the environment (52).

However, one must tread carefully with the optimisation of crews’ personal usage. Although this is the measure which crew have the most direct impact on, reducing lighting on board can be associated with safety concerns, and refrigeration to crew morale, because the quality of food on board was a particular non-monetary incentive for crew on board and a source of comfort.

5.1.3. Trim Draft

Another measure that was consistently mentioned by the interviewees of having potential for improvement was trim draft optimisation, which some interviewees reported was not in use at their companies currently. Poulsen et al (2021) mention discrepancy in agreement between engine room and deck teams (19). While the former has the opinion that a forward trim has a sizable impact on efficiency, the latter thinks this brings the propeller closer to surface thus risking safety. Crew need training in the use of such equipment and not all ships have the software/capability.

5.1.5. Fuel Consumption Monitoring

The tools measuring fuel efficiency were also brought into question. Although noon reports are important, interviewees report that they may be predated, and more modern tools could allow for live monitoring of fuel efficiency. This more instantaneous feedback on fuel consumption would provide crews with awareness of the actual energy efficiency of their onboard decisions and operations. Although both crew and charterers are keen to save fuel as this also cuts costs, the new technology required to monitor this would come with an expectation of quick savings, and to prove the system’s cost-benefit ratio. However, real time monitoring tools require long-term analysis of data to establish patterns and understand the premise of any savings made as even energy systems which allow you to look at individual parameters do not reflect the complex reality of ship energy consumption (49). In Viktorelius’s 2019 study where the post-adoption phase of a new energy-monitoring technology on board was analysed, some masters admitted that there were problems with both the input and output of data required to extract long-term objective patterns from the system (49).

5.1.6. Crew Autonomy

“There is a choice, as long as there is justification” J-ENG

The fact that the crew’s justification of their decisions to charter party and their own managers and owners comes retrospectively, leads us to hypothesise whether rather than the current consensus of restricted autonomy, it may be that crew has “answerable autonomy”, whereby the limitation lies in the expectation to successfully justify any autonomic decisions to higher-ups, rather than the inability to make decisions at all. Empowering the function and expanding the limits of this autonomy in favour of energy efficiency may be achieved by educating crew in and involving them in each ship’s SEEMP (22) which can allow them to make energy efficient decisions and justify to their charterers how these decisions are also in line with their cost management plans. In other studies, energy saving checklists developed based on audits, and incentive or bonus schemes have been suggested as ways of tackling crew awareness and training (23), which are essential prerequisites to involving crew in a ship’s SEEMP. However, it may seem that by proposing that crew’s only incentive in fuel consumption is extrinsic e.g.monetary, we are neglecting any intrinsic incentives e.g. personal pride they may have as seafarer’s in fuel consumption. This is an important dilemma and is addressed in the discussion in

Section 5.2.

The decision makers themselves may also fall short in the optimality of the decisions, which depend on the quality of the input data they receive from the voyage. Not only the crew who are closest to the real-time decisions made during the charter, but also the charterers themselves could be educated in the assessment of available measures in the market to make the most optimal decisions which align both energy efficiency as well as cost and safety (23).

5.2. Incentives

5.2.1. Current Practice

The mix of answers in interviews and surveys suggested that a review of both the types of incentives offered and their distribution across the vessel is needed. While safety was mentioned in both interviews and surveys, no interviewee reported being rewarded for fuel efficiency even though both the charter and crew recognise that ‘profitability’ is associated with efficiency. Contrary to this, 16% of respondents in the survey did report fuel efficiency as an incentivised measure, however, considering the important role of operational energy efficiency, this is still a minority.

5.2.2. Incentive Categories

Though overwhelmingly, monetary bonuses are offered, preferred, and available to the respondents, there is an awareness that their higher offering and anticipation could in time diminish returns, however, it can be argued that these returns are offset if they incentivise money-saving measures such as optimising auxiliary engine load and personal usage onboard. Regardless, where this is a concern, respondent focus on “recognition and acknowledgement” as well as welfare onboard highlights a place for non-monetary incentives as an area requiring little to no capital investment. When asked about acknowledgement within their companies, a Swedish crew exclaimed: “We have that, it’s not like working for a large company” (50) which suggests that closer working relationships, and a close relationship from further up the stakeholder chain may be key to perpetuating this incentive (54). In interviews, crew mentioned internet access, meals onboard, and feeling cared for under the umbrella of onboard welfare as other preferred options, which also rated highly in the surveys.

Despite the technical capability of ships to provide internet (54) many companies do not provide easily accessible nor affordable internet to the crew (55) The agreement in May 2022 on the introduction of mandatory internet provision, under the Maritime Labour Convention (2006) by the International Labour Organisation, which comes into force in December 2024 will go in some way to overcome this challenge (56). Improving social connectivity for seafarers and in turn their social wellbeing and mental health, which are a cause for concern (57) could lead to better on-the-job performance as well as retaining a highly motivated crew (37,54,57).

The linear alignment between what our sample knows and prefers, such as that observed with monetary incentives may be used to advance pro social incentives into the narrative. Although interviewees did not fail to mention prosocial incentives, there was little specification of what they meant by them. It can be questioned whether this is because they are not common or known and examples could not be given because crew had not experienced these, but it is difficult to draw any conclusions due to their minority status being an industry wide status quo, although their efficacy has been proven in other transport sectors such as aviation (37,58)

5.2.3. Incentive Distribution

The current reward structure is at odds with equity and fairness within the ship setting, as it seems that the highest ranked and paid i.e. ship’s captain, is rewarded the most for the efforts of a team. Although this may be justified by the fact that it is the captains and chief officers who are usually in charge of these operational measures (see the captain’s dominion on weather routing, and the chief engineer’s control of auxiliary engines), the fact that it is the captain who is most commonly incentivised for performance was not a popular with neither interviewees nor survey respondents, who believed that incentives should be shared with the crew.

A first step solution to this could be revisiting incentive structures and redistributing funds initially by the top four ranks on a ship (captain, chief engineer, chief mate and chief steward), which could allow for a relatively similar amount of funds to be distributed to a larger percentage of the work force —which feeds better into interviewee preference of ‘team/vessel recognition’ instead of individual awards. However, incentivising only the “top 4” i may alienate other members of the crew who are the ones carrying out the optimization, even if its ultimate responsibility and control lies in the hand of the top 4.

Another reason for rewarding only the captains may be because of the regularity with which a captain would sail on the ship, usually in rotation with one or two other colleagues, compared to the rest of the crew who could change from one voyage to another, and their short-term contracts.

The discrepancy in the tenure of the onboard crew also presents a challenge to effectively rewarding performance rightfully to the crew member who caused the efficiency gain. A vessel’s key performance indicator (KPI) is on a per voyage basis but also on a yearly basis, and who should be rewarded for good performance at the end of the year can be tricky as crew members may have already left or onboard another vessel.

Continuous employment as opposed to employment by voyage (58) and longer contractual obligations (59) , can be ways to allow for ship-wide distribution of monetary incentives which are fair and proportional to individual efforts within the team.

The next step would be targeted ship-specific incentive structures. If a chief engineer is the main entity responsible for the optimisation of operational measures, such as their involvement in auxiliary engine usage, the adoption of this measure by the chief engineer could be personally targeted. If captains have tools at their disposal but are not aware of them, their incentives could be targeted towards the adoption of these tools.

Finally, intrinsic (experienced meaningfulness) and extrinsic (pay satisfaction) motivators/incentives are complementary to one another (60) and when beginning to implement extrinsic incentive schemes, seafarer’s personal pride and intrinsic motivations for improving energy efficiency must not be discounted. In interviews, the fact that energy efficiency is already “part of the job” came up more than once. Crew are contractually obliged to optimise performance to the maximum extent, however, energy efficiency does not always explicitly fall under the umbrella of “performance”. By making energy efficiency’s role in the measuring of performance more explicit, crew’s intrinsic motivations to “do well” can be targeted more closely towards optimising energy efficiency on board.

6. Conclusions

We have found that there is an absence of an explicit narrative around optimizing operational efficiencies to save fuel and benefit the environment in the workplaces of our respondent seafarers. That is simply assumed to be a by-product. It is important to note here that until and unless hierarchically powerful entities set priorities that emphasize ‘saving fuel to save the environment as a priority’, this is unlikely to trickle down to decision makers on board a vessel, whose own decisions are steered by larger company/charter party/owner and personal priorities.

Benefits to the environment can be woven into the existing priorities communicated to key decision makers on board a vessel. While the captain and key decision makers have first-hand control and agency over operational measures, their actual power to influence some of the measures, especially those with significant energy efficiency savings, such as speed reduction, are situated within a complex web of accountability that needs to but cannot significantly prioritise the environment. This therefore leaves only a handful of other measures to optimise, such as auxiliary engine load optimisation, trim draft optimisation and weather routing, which have smaller efficiency gains, but if aggregated and consistently applied through behavioural changes and practices, encouraged through incentives, can lead to significant fuel savings over time. These smaller number of measures can be supplemented with education and inclusion of crew into the ship’s SEEMP, longer contractual relationships, and the optimisation of and training in energy consumption monitoring tools to maximise efficiency gains.

Incentives can be much more effectively utilized to manage and propel these changes. Non-monetary incentives requiring little capital such as recognition and acknowledgment are extrinsic motivations which can have a positive effect on intrinsic seafarer incentives, and which are easy to implement. Although there is a positive correlation between the preferred incentives and those which are offered, their distribution appears to be an area for further implementation. This is especially pertinent since it is clear that shipping companies have autonomy in setting incentives relative to other sectors such as aviation, where industry regulations restrict the ability of individual companies to incentivise employees over and above their salaries.

Once the right incentives are in place, their distribution must be expanded. Exclusively directing incentives to the captain or the ‘top 4’, as seems to be current practice, is likely to make the rest of the crew feel that they don’t have much of a role to play when it comes to saving fuel. Distributing incentives to include the crew coupled with the inclusion of reducing emissions and saving the environment into the set of priorities will ensure that every member of the crew feels that they have a role to play in reducing fuel consumption. This sense of agency can lead to positive spillovers, where even seemingly insignificant behaviours like air conditioning use and fridge temperature can lead to significant gains when aggregated.

Lastly, the potential oversaturation feared when it comes to introducing incentives is less likely to pose a problem as a sizable percentage of the sample were not aware of any incentives being available to them at all for good performance on energy efficiency or other areas e.g. safety. Incentives are not just about the what, but also about the who and the how and therefore need to be looked at as a holistic package of these three factors. These three aspects have revealed themselves as dimensions of significance through the interview and survey data.

Our study is limited in its small sample size; however, we believe that this is offset by the minimal existing research on incentives, which we hope will grow in the future. Although this limits the study’s generalisability, as one of the first papers on the topic of incentives, we are posing the question of the feasibility of their possible role in shipping. Our findings on incentives are mirrored in other studies on road freight and aviation, which support our claims.

This study presents a preliminary set of incentive structures that can be compared to one another in a Randomised Control Trial. This should be supplemented by further qualitative work to better understand survey results on incentives. Some of the results suggested incentive structures involve the crew and are tied to performance or behaviours that go beyond just the individual. Therefore, further work can help understand if an increase in efficiency was also correlated with an increase in crew engagement, and overall wellbeing and satisfaction, which are also key metrics to consider.

Appendix

Interview guide

Part 1: Areas where there may be potential for improving operational energy efficiency

Main q: In which areas of operation, where you have the most control, of the ship do you think there may be potential for improving energy efficiency/fuel efficiency?

Speed reduction

How does a master achieve ‘average speed’ instructions in practice (e.g. do they speed up initially, slow down later, constant speed, variable speed? i.e. is there room for improvement in how speed instructions are actually enacted

How much of a restriction is this on the mind of a master during a voyage?

How do you currently address the incentive to speed up under FCFS and utmost despatch and it’s significant impact on speed/efficiency? What are the trade-offs assessed to decide to go ahead or not with arriving on time?

How is the assessment of the repercussions of a “late arrival to the queue” carried out?

How do crew perceive slow steaming (more work? Lack of a break?)

Applies to shore-based staff

Do inventory costs influence decisions on speed?

If slow steaming is chosen how is this communicated to the crew?

What factors influence the instructions on speed?

Weather routing

What is the perception of the crew on using weather routing versus rule of thumbs (sailing on previously calm/safe routes)?

How much can a master decide on whether the route he/she sails is of a particular nature/how much autonomy do they have?

Just In Time arrival (applies to shore-based staff)

How do charterers/operators currently obtain information on port status (congestion, unexpected delay, etc.) and what do they do with this information?

Do any of the routes in your operations have ports that can/do share information for virtual arrival

Trim-draft optimisation/loading profile

Where a trim/draft optimisation software exists, does it get used on every voyage and what do you think are the key barriers to it’s effective usage?

How is the safety of a specific trim assessed in your vessel?

How could the loading plan steps be improved to optimise trimming as an option?

In the context of trimming, How much room for improvement is there on ballast loads given restrictions by environmental regulation?

Improving auxiliary engine loads

Is there room for energy efficiency gains in the management of auxiliary machinery at optimal loads? And what are the barriers to achieving those gains

Operation of other energy efficiency devices on board

What energy efficiency technologies have been implemented in your vessel? Are they being used optimally? What could be done to improve their utilisation.

Do you think there are new EETs that have the potential to reduce a workload (passage planning, route monitoring, better information about optimal trim / speed/ autopilot setting, power management systems etc).

What are the incentives to using autopilot during every voyage, what might be the barriers to its use

Part 2: Incentives

What types of rewards and incentives are you offered at work?

What types of rewards and incentives are seagoing staff/crew onboard offered at work?

What types of incentives, in your opinion, are most meaningful to crew / what type of incentives do crew want?

Survey questions

How important are the following in motivating you in your job?

| |

Not at all important |

Low importance |

Neutral |

Moderately important |

Very important |

| Challenging work that gives me a personal sense of accomplishment |

|

|

|

|

|

| Opportunity for high earnings |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cooperative colleagues |

|

|

|

|

|

| Good training opportunities to improve skills |

|

|

|

|

|

| Good benefits/perks over and above my salary |

|

|

|

|

|

| Recognition when I do a good job |

|

|

|

|

|

| Good working conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

| Good working relationship with my onboard/onshore team |

|

|

|

|

|

Do you think individuals should be rewarded over and above their salary for good performance in their jobs?

| Strongly agree |

|

| Agree |

|

| Neither agree or disagree |

|

| Disagree |

|

| Strongly disagree |

|

How much would the following performance rewards motivate you to improve your performance? 1=Not at all, 2=Somewhat, 3=neutral, 4=Moderately, 5=Very much

| |

Not at all |

Somewhat |

Neutral |

Moderately |

Very much |

| Monetary bonus over salary (annual or specific) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Access to upskilling / training programs |

|

|

|

|

|

| Increased WiFi top-up / internet allowance onboard |

|

|

|

|

|

| Welfare onboard |

|

|

|

|

|

| Extra holidays |

|

|

|

|

|

| Business or first class flights |

|

|

|

|

|

| Recognition (acknowledgment via awards, certificate) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Vouchers |

|

|

|

|

|

| Contributions to a charity by employer on your behalf |

|

|

|

|

|

Are there any types of rewards that would not motivate you to improve your performance?

What types of performance rewards does your company provide (across all types of roles)? Please tick as many as applicable

| Monetary bonus over salary(annual or specific) |

|

| None of the above/not aware of any |

|

| Recognition (acknowledgment via awards, certificate) |

|

| Welfare onboard |

|

| Access to upskilling/training programs |

|

| Increased WiFi top-up/more internet allowance (onboard) |

|

| Extra holidays |

|

| Business or first-class flights |

|

| Contributions to a charity by employer on your behalf |

|

| Vouchers |

|

| Other |

|

Which of the following performance rewards are you currently offered at work for YOUR role? Please tick as many as applicable.

| Monetary bonus over salary(annual or specific) |

|

| Business or first class flights |

|

| Increased WiFi top-up/more internet allowance (onboard) |

|

| Contributions to a charity by employer on your behalf |

|

| Extra holidays |

|

| Welfare onboard |

|

| Recognition (acknowledgment via awards, certificate) |

|

| Vouchers |

|

| Access to upskilling/training programs |

|

| None of the above |

|

Which of the following measures or behaviours are you rewarded for (over and above your salary/remuneration)? Please tick as many as applicable

| Safety record |

|

| None of the above |

|

| Fuel efficiency |

|

| Other |

|

| Timely arrival |

|

How would you prefer rewards to be attributed? Please tick as many as applicable

| On an individual/personal basis |

|

| Based on a specific vessel's performance over a given period |

|

| Based on overall crew/team performance during a voyage |

|

| Other |

|

In your opinion, if there are rewards for improving fuel efficiency, how should the rewards be distributed?

| The captain should retain all of the reward |

|

| The reward should be equally shared amongst the captain and the crew |

|

| The captain should get a majority of the reward but the crew should receive a share as well |

|

Demographic questions

Please describe your role in the company

| Captain |

|

| Chief engineer |

|

| Chief officer |

|

| Crew member |

|

| Other |

|

How long have you been employed by your company?

| Under 1 year |

|

| 1-3 years |

|

| 3-5 years |

|

| 5-10 years |

|

| over 10 years |

|

Which of the following shipping sectors or ship types does your employment belong to generally? Please tick as many as applicable

| Wetbulk/tanker |

|

| Other |

|

| Container |

|

| Drybulk |

|

| Ferry/cruise |

|

References

- Cames M, Graichen J, Siemons A, Cook V. Emission Reduction Targets for International Aviation and Shipping study. 2015. Available from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/569964/IPOL_STU(2015)569964_EN.pdf.

- IMO. Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships. 2023. Available from https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/Pages/2023-IMO-Strategy-on-Reduction-of-GHG-Emissions-from-Ships.aspx.

- Rehmatulla N, Smith T. Barriers to energy efficiency in shipping: A triangulated approach to investigate the principal agent problem. Energy Policy. 2015; 84: 44-57.

- Poulsen RT, Viktorelius M, Varvne H, Rasmussen HB, von Knorring H. Energy efficiency in ship operations - Exploring voyage decisions and decision-makers. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2022; 102:103120.

- Kaminski, W. Implementation of energy efficiency management in shipping companies and ships in operation. Scientific papers of Silesian University of Technology Organisation and Management Series no 157. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 12]; 157(157):223–35. Available from: http://managementpapers.polsl.pl/.

- Barreiro J, Zaragoza S, Diaz-Casas V. Review of ship energy efficiency. Ocean Engineering. 2022; 257:111594.

- Patterson, MG. What is energy efficiency?: Concepts, indicators and methodological issues. Energy Policy. 1996; 24 (5): 377–390.

- Bouman EA, Lindstad E, Rialland AI, Strømman AH. State-of-the-art technologies, measures, and potential for reducing GHG emissions from shipping – A review. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2017; 52: 408–21.

- Banks C, Turan O, Incecik A, Lazakis I, Lu R. Seafarers’ Current Awareness, Knowledge, Motivation and Ideas towards Low Carbon-Energy Efficient Operations. Journal of Shipping and Ocean Engineering. 2014; 4: 93–109.

- Armstrong VN, Banks C. Integrated approach to vessel energy efficiency. Ocean Engineering. 2015; 110 (B): 39–48.

- Viktorelius M, Varvne H, von Knorring H. An overview of sociotechnical research on maritime energy efficiency. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs. 2022; 21(3): 387–399.

- Jafarzadeh S, Utne IB. A framework to bridge the energy efficiency gap in shipping. Energy. 2014; 69: 603–612.

- Rehmatulla N, Smith T, Wrobel P. Barriers to low carbon shipping, Low Carbon Shipping Conference. 2013; Available from: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1450793/.

- Fang, Y. Adrift, alone and far from home: The human side of the global maritime industry. Harvard Int Rev. 2021; 42(1): 62–66.

- Poulsen RT, Johnson H. The logic of business vs. the logic of energy management practice: understanding the choices and effects of energy consumption monitoring systems in shipping companies. J Clean Prod. 2016; 112: 3785–3797.

- Wang, H. Long-term potential for increased shipping efficiency through the adoption of industry-leading practices. The International Council on Clean Transportation. 2013; Available from: https://www.academia.edu/download/89020428/ICCT_ShipEfficiency_20130723.pdf.

- Faber J, Lee D, Becken S, Corbett JJ, Cumpsty N, Fleming G, et al. Bridging the gap – the role of international shipping and aviation. 2020; 1–16. Available from: https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020.

- Christodoulou A, Gonzalez-Aregall M, Linde T, Vierth I, Cullinane K. Targeting the reduction of shipping emissions to air: A global review and taxonomy of policies, incentives and measures. Maritime Business Review. 2019; 4 (1): 2397–3757.

- Poulsen RT, Viktorelius M, Varvne H, Rasmussen HB, Von Knorring H. Energy efficiency in ship operations - Exploring voyage decisions and decision-makers. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2022; 102:103120.

- Thollander P, Palm J. Improving energy efficiency in industrial energy systems: An interdisciplinary perspective on barriers, energy audits, energy management, policies, and programs. 2013; Springer, London.

- Dewan MH, Godina R. Seafarers Involvement in Implementing Energy Efficiency Operational Measures in Maritime Industry ScienceDirect Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 4th International Conference on Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023; 217:1699–1709. [CrossRef]

- Hansen E, Kragesand, Rasmussen H, Barbara, Lützen M, Hansen EK, et al. Making shipping more carbon-friendly? Exploring ship energy efficiency management plans in legislation and practice. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2020; 65:101459.

- Dewan MH, Ameen M, Mustafi A, Matos F, Godina R. Exploring Seafarers’ Knowledge, Understanding, and Proficiency in SEEMP: A Strategic Training Framework for Enhancing Seafarers’ Competence in Energy-Efficient Ship Operations. Heliyon. 2024; 10(17): e36505.

- Rasmussen HB, Lützen M, Jensen S. Energy efficiency at sea: Knowledge, communication, and situational awareness at offshore oil supply and wind turbine vessels. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2018; 44: 50–60.

- Dewan MH, Godina R. Unveiling seafarers’ awareness and knowledge on energy-efficient and low-carbon shipping: A decade of IMO regulation enforcement. Mar Policy. 2024; 161:106037.

- ISWAN. The impact of maritime decarbonisation on wellbeing: Findings of an ISWAN survey of seafarers and shore-based staff. London; 2024. Available from: https://www.iswan.org.uk/resources/publications/the-impact-of-maritime-decarbonisation-on-wellbeing-findings-of-an-iswan-survey-of-seafarers-and-shore-based-staff/.

- Shinohara, M. Quality Shipping and Incentive Schemes: From the Perspective of the Institutional Economics. Maritime Economics & Logistics. 2005; 7(3): 281–295.

- Becqué R, Fung F, Zhu A. Incentive schemes for promoting green shipping. NRDC. 2017; Available from: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/incentive-schemes-promoting-green-shipping-ip.pdf.

- Jensen MC, Meckling WH. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J financ econ. 1976; 3(4): 305–360.

- Longarela-Ares Á, Calvo-Silvosa A, Pérez-López JB. The Influence of Economic Barriers and Drivers on Energy Efficiency Investments in Maritime Shipping, from the Perspective of the Principal-Agent Problem. Sustainability, 12 (19): 7943.

- Johnson H, Johansson M, Andersson K. Barriers to improving energy efficiency in short sea shipping: an action research case study. J Clean Prod. 2014; 66: 317-327.

- Blumstein C, Krieg B, Schipper L, York C. Overcoming social and institutional barriers to energy conservation. Energy. 1980; 5(4): 355–371.

- Bubshait, AA. Incentive/disincentive contracts and its effects on industrial projects. International Journal of Project Management. 2003; 21(1): 63–70.

- Herten HJ, Peeters WAR. Incentive contracting as a project management tool. International Journal of Project Management. 1986; 4(1): 34–39.

- Liu W, Liu Y. The Impact of Incentives on Job Performance, Business Cycle, and Population Health in Emerging Economies. Front Public Health. 2021; 9:778101.

- Suprapto M, Bakker HLM, Mooi HG, Hertogh MJCM. How do contract types and incentives matter to project performance? International Journal of Project Management. 2016; 34(6): 1071–1087. [CrossRef]

- Gosnell G, List J, Metcalfe R. The impact of management practices on employee productivity: A field experiment with airline captains. Journal of Political Economy. 2020; 128 (4): 1195-1233.

- Vernon D, Meier A. Identification and quantification of principal–agent problems affecting energy efficiency investments and use decisions in the trucking industry. Energy Policy. 2012; 49: 266–273.

- Schall DL, Mohnen A. Incentives for Energy-efficient Behavior at the Workplace: A Natural Field Experiment on Eco-driving in a Company Fleet. Energy Procedia. 2015; 75: 2626–2634.

- Handgraaf MJJ, Van Lidth de Jeude MA, Appelt KC. Public praise vs. private pay: Effects of rewards on energy conservation in the workplace. Ecological Economics. 2013; 86: 86–92.

- Pinchasik DR, Hovi IB, Bø E, Mjøsund CS. Can active follow-ups and carrots make eco-driving stick? Findings from a controlled experiment among truck drivers in Norway. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2021; 75:102007. [CrossRef]

- Frey BS, Jegen R. Motivation Crowding Theory. J Econ Surv. 2001; 15(5): 589–611.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Cognitive Evaluation Theory. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. 1985; 43–85.

- Promberger M, Marteau TM. When Do Financial Incentives Reduce Intrinsic Motivation? Comparing Behaviors Studied in Psychological and Economic Literatures. Health Psychology. 2013; 32(9): 950.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3(2): 77–101.

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Putting the human back in “human research methodology”: The researcher in mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2010; 4(4): 271–277.

- Kvale, S. The Qualitative Research Interview. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 1983; 14 (1–2): 171–96.

- Creswell, J; Creswell D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sixth Edition, SAGE Publications. 2022.

- Viktorelius M, Lundh M. Energy efficiency at sea: An activity theoretical perspective on operational energy efficiency in maritime transport. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2019; 52: 1–9.

- Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int J Qual Methods. 2023; 22.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Fourth Edition. 2014. Wiley, New Jersey.

- Hammander M, Karlsson P, Österman C, Hult C. How Do You Measure Green Culture in Shipping? The Search for a Tool Through Interviews with Swedish Seafarers. TransNav - International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation. 2015; 9 (4): 501–9.

- Zoubir M. Onboard energy-efficient operations and decision-making of ship crews. University of Lubeck. MSc thesis. 2019. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337950951_Onboard_energy-efficient_operations_and_decision-making_of_ship_crews.

- Kenney M, Gardner N, Palmajar E, Sivori H. Seafarers in the Digital Age: Prioritising The Human Element in Maritime Digital Transformation. 2022. Available from: https://www.inmarsat.com/en/insights/maritime/2022/seafarer-human-element-digital-transformation.html.

- DfT. Maritime 2050: Navigating the Future. London. 2019. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/maritime-2050-navigating-the-future.

- IMO. Revised Strategic Plan for the Organisation for the Six Year Period 2018-2023. International Maritime Organisation (IMO). 2022. Available from: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/About/strategy/Documents/A%2032-Res.1149.pdf.

- Sampson H, Ellis N. Seafarers’ mental health and wellbeing. 2019. Available from: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/127214/1/seafarers-mental-health-wellbeing-full-report.pdf.

- Mitroussi K, Notteboom T. Getting the work done: motivation needs and processes for seafarers and dock workers. WMU Journal of Maritime Affair. 2015; 14(2): 247–265.

- Rialland A, Nesheim DA, Norbeck JA, Rødseth ØJ. Performance-based ship management contracts using the Shipping KPI standard. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs. 2014; 13(2): 191–206.

- Thakor MV, Joshi AW. Motivating salesperson customer orientation: insights from the job characteristics model. J Bus Res. 2005; 58(5): 584–592.

- Churchman P, Longhurst N. Where is our delivery? The political and socio-technical roadblocks to decarbonising United Kingdom road freight. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2022; 83:102330. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).