1. Introduction

As a crucial part of maritime supply chain, shipping serves as a driving force for global trade, ensuring the efficient and safe movement of raw materials, finished goods, and commodities worldwide. However, as the backbone of the economic development, shipping also poses a significant environmental threat, producing some other pollutants such as sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, contributing to air pollution and acid rain [

1]. According to estimates by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), approximately 2-3% of global GHG emissions comes from shipping, a notable contribution to carbon emissions. Reducing this impact has become a focus for international environmental policies. And it is still the most urgent and imperative issues to mitigate carbon emission in maritime shipping [

2].

On a global scale, international agencies, such as IMO, have set forth regulations that enforce carbon emission reductions. One of the most significant is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from ships by at least 50% by 2050, compared to 2008 levels. This ambitious target requires coordinated efforts across nations and industries, including technological innovation, operational efficiency, and compliance with emission standards.

At the heart of the maritime supply chain system are shipping companies (i.e., carriers), which provide the essential services of shipping transportation. In addition to responsibilities for transporting cargoes, carriers also play a critical role in ensuring the smooth operation of supply chains by providing reliable, safe, and compliant transportation services. Carriers not only ensure goods are delivered across borders but also influence broader economic trends. Besides, tasked with transporting vast quantities of goods across oceans, carriers now face growing pressure to reduce caron emission.

To carriers, transitioning to focusing on emission reduction strategies, such as structural and power system modification, environmental protection equipment installation, etc., to comply with regulations and market needs, which can lead to increased operational costs [

3]. Furthermore, carriers also face the risk of not recouping their investments in low-carbon fuels due to insufficient customer demand. Additionally, a competitive environment for carriers hinders emission reduction efforts due to cost pressures, resulting in a low motivation to adopt low-carbon energies.

Shippers are also seeking greener options, aligning their supply chains with sustainability goals by partnering with carriers that demonstrate environmental responsibility. Their demand for low-carbon logistics solutions is helping to drive competition among shipping companies to offer more sustainable services.

In response, various governments and international organizations are implementing low-carbon subsidy incentives aimed at encouraging carriers to adopt greener energies and practices. Providing financial incentives for the adoption of low-carbon technologies and fuels is proved to be highly efficient to address climate change issues [

4,

5,

6]. Several researchers analyzed two different strategies to mitigate emission of a transport chain with carriers’ competition [

7]. But they neglected government incentives impact on carbon reduction. The impact of subsidies and carbon tax policy on the development of competition was considered among different ocean carriers [

8]. But what they did not consider is that whether providing subsidies to carriers in a competitive environment can reduce carbon emissions effectively. Our previous work also considered subsidies and competitive carriers, but it only focused on how to relieve lock congestion before TGD [

9]. Price competition between carriers was also considered, but government subsidies and carbon emission reduction were out of their scope [

10]. With ocean carriers’ competition, how subsidies from the government can impact carbon emission alleviation, or if subsidies are effective to abate carbon emission is seldomly studied by researchers. To fill in this gap, we want to answer the following questions in this paper:

(1) Should government subsidize price-competitive carriers and encourage them to make the transition to decarbonize?

(2) What is the optimal subsidy strategy under different scenarios? And how effective is such a subsidy in reducing carbon emission?

(3) Taking into account the price competition and shippers’ green preference, what impact do they have on service prices, demands, profits, carbon emission and social welfare?

To figure out these issues, we develop game models to illuminate the interactive relationship among the port, the government, two competitive carriers and green preference shippers. Then, we derive equilibrium results for each partner under three different scenarios. After that, numerical analysis is conducted.

There are several contributions in this study. Firstly, game models are constructed to explore the interactions among different players of the maritime supply chain. Through optimal results derived, we explore the impact of subsidy strategies with price-competitive carriers on carbon emission reduction in green shippers. To our knowledge, this is seldom studied in extant literature. Secondly, we demonstrate the effectiveness of subsidies in mitigating carbon emissions in a price-competitive environment. Carriers are encouraged to make investments in the adoption of low-carbon technologies, contributing to more sustainable environment. Last, we reveal how shippers’ low-carbon preference and price competition between carriers impact prices, demands, profits, carbon emission and social welfare. Our paper can provide decision-makers managerial insights to achieve sustainable environment.

The reminder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 briefly reviews the related literature.

Section 3 describes the problem and model formulation is given in

Section 4.

Section 5 and

Section 6 give the modal analysis and numerical analysis. Conclusion is presented in

Section 7. Proofs are provided in the Appendix.

2. Literature Review

The first stream of related literature is carbon emission control strategy of a maritime supply chain. And ports, shipping companies and forwarders are the main implementing subjects [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Different strategies are adopted to abate carbon emission, such as blockchain technologies [

13,

17,

18], port construction or infrastructure [

6,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], low-carbon fuel adoption [

1,

6,

7,

12,

24]; carbon tax and cap-and-trade [

8,

25,

26]. Shipping carriers made decisions about sustainability investment to comply with emission control regulations in a two-level maritime supply chain [

11]. The role of ports taking part in shipping decarbonization was analyzed, and various measures ports can be adopted to facilitate ships’ emissions reduction [

27]. Balcombe et al., (2021) utilized new emissions measurements to assess the cost of LNG as the shipping fuel, and a 50% decarbonisation target can be met with a methane emissions reduced to 0.5% of throughput [

24]. Considering investment in carbon abatement of a maritime supply chain, Huang et al., (2023) also investigated the influences of government policies and social preferences [

4]. After a comparison analysis, Chen et al., (2023) found that emission was reduced significantly after COVID-19 for passenger shipping in Danish waters [

28]. Taking CMA-CGM as an example, emissions inventories were quantified with a bottom-up framework at the worldwide level [

29].

Our paper also relates to the area of government subsidy. Government encourages NEV carriers to make green innovations with subsidies [

30]. And incentive policies can be helpful for the increasement of revenue of carriers [

23]. The impact of government subsidies on shipping companies are elaborated in [

20]. Results indicated that price subsidies can help improving shipping supply chain profits. Two incentive policies were considered on ship-borne power receiving system deployment to reduce carbon emission near ports in [

21]. Carbon abatement investment and low-carbon service investment from the government subsidies were considered in [

4]. Findings indicated that government subsidies can significantly improve greenness of the maritime supply chain. Wang et al., (2023) studied the influence of government subsidies for shipping companies to choose shore power or lower sulfur fuel oil. They found that government subsidies can play different roles under certain power structures [

1]. Zhen et al., (2022) investigated subsidy strategies to install and utilize shore power for ports, and they optimized subsidies to reduce costs for government and maximize profits for ports [

21]. Li et al., (2024) analyzed the government adopting two subsidy schemes for port operations to meet low-carbon requirements [

17]. Wang et al., (2024) designed two different subsidy schemes for the shipping company through Hotelling models [

31]. Luo et al., (2024) considered government incentivizes shipping operators to retrofit ships and initially uses SP of a shipping supply chain in the short term [

22].

The last related topic is price competition between carriers. Huang et al., (2023) analyzed investing in blockchain technologies in competitive environment. Results indicated that competition between shipping companies would affect the service prices [

4]. Xie and Wang (2024) investigated two competing carriers of two transportation chains about which to be the privileged carrier [

15]. Considering shipping supply chain competition, game models are formulated to investigate the equilibrium strategies of shipping operators on SP usage under different policies [

22]. Zhou and Zhang (2022) constructed game models to analyze the emission control strategy of the port with the customers’ low-carbon preference. Results demonstrated that with customers’ low low-carbon preference, the port should adopt LSFO to obtain higher profits, but also with higher carbon emissions [

14].

As depicted above, there is limited literature addressing carbon emission reduction for price-competitive carriers in government subsidies and green shippers. To fill in this gap, we develop game models to abate carbon emission reduction strategies considering government intervention and green preference from shippers, and try to find optimal strategies under three different scenarios. Our paper differs from previous work in that it considers not only the price-competition between ocean carriers but also government subsidies and green shippers to abate carbon emission.

3. Problem Description

We consider a maritime supply chain consisting of a port, two price-competitive carriers, shippers and the government. The port, located upstream, provides services such as cargo handling, storage, berthing to carriers, denoted as and , respectively. For simplicity, the port’s marginal cost is assumed to be zero. As the buyer of services, shippers have preferences for low-carbon transportation options. Carriers set their own service prices with and , and compete in price aiming to offer the best transportation services.

In the maritime supply chain, the government acts as the Stackelberg leader, strategically offering subsidies to carriers to maximize social welfare. These subsidies incentivize carriers to invest in emission-reduction technologies and contribute to a greener maritime supply chain. The port and carriers prioritize maximizing their profits.

According to [

32,

33,

34], we suppose demand functions are defined as:

In the demand model, means the demand of different carriers, represents the competition intensity between ocean carriers, is the service price of carriers provided to shippers, is the environmental awareness from shippers. The higher , the higher the degree of greenness during the transportation. is the carbon emission, here, we assume that all carriers possess the same level of carbon emission under the same scenario.

To clarify the interactive relationship among different players in the maritime supply chain, game models under three scenarios are developed: Scenario OS, Scenario CS and Scenario BS. In Scenario OS and CS, only one carrier, namely, carrier 1 or carrier 2, takes carbon emission reduction measures with government subsidies. In scenario BS, both carriers are subsidized to take actions to alleviate carbon emission.

According to the extant studies [

13,

17,

32,

35,

36], the additional sustainability investment cost for ocean carriers to abate carbon emission is denoted by

, with

representing the subsidy level. The government shares

of the total investment. Correspondingly, profit functions for different players and social welfare functions will change in different scenarios. For convenience, the symbols and notations are shown in

Table 1.

4. Model formulation

Three different scenarios are described as below:

4.1. Scenario 1. (Scenario OS)

In this scenario, carrier 1 will invest a total of

in carbon emission abatement, with additional subsidies provided by the government. Profit functions of both carriers and the port, and the social welfare function are expressed as Equations (3) to (7):

Lemma 1. In scenario OS, social welfare function is jointly concave related to , and , when .

Based on Lemma 1, we know that there exist optimal values such as price, demand, carbon emission reduction, profits, social welfare, obtained by taking first-order partial derivatives of

with respect to different parameters, as shown in

Table 2.

4.2. Scenario 2. (Scenario CS)

In this condition, ocean carrier 2 receives subsidies from the government, which covers

of the total investment cost

. So, profit functions and the social welfare are formulated as Equations (8) to (12). By solving these equations, other optimal results can be derived.

Lemma 2. When , social welfare function is jointly concave related to , , and .

Similarly, based on Lemma 2,

Table 3 presents optimal results derived from taking first-order partial derivative of

with respect to

,

, and

, respectively. Accordingly, other optimal solutions can be obtained.

4.3. Scenario 3. (Scenario BS)

In this scenario, the total investment cost for carriers to reduce carbon emission is

. The government share

and

of the total investment cost, respectively. Profit functions for all partners and social welfare are formulated as Equations (13) to (18).

Lemma 3. When , social welfare function is jointly concave related to , , and .

The following

Table 4 outlines optimal results derived by solving first-order derivatives of Equation (18).

5. Model analysis

5.1. Analysis for Price and Demand

Proposition 1. Optimal prices and demands under different scenarios satisfy: (1) , and increase in and decrease in , and , , when and increase; (2) differs in , and satisfy , and ; (3) differs in , and satisfy , and .

See Appendix for Proof of Proposition 1.

Proposition 1 indicates that as competition intensifies, service prices charged by different carriers tend to increase. Although subsidies can help offset operational costs to alleviate carbon emission, allowing carriers the flexibility to increase prices in order to capture a larger market share, which can ultimately strengthen their long-term competitiveness. And increased subsidies may lead to overcapacity, resulting in a decline in shipping volume.

5.2. Profit and Social Welfare analysis

Proposition 2. The optimal profits satisfy (1) differs in and ; (2) , , and .

Proposition 3. (1) increase in ,when , ; when , ; when , ; (2) decrease in , when , ;when , .

Proof of Proposition 2 and 3, see Appendix.

Proposition 2 indicates that with the increase of intensified competition and subsidies, carriers must increase service quality, shorten transit times, and invest in greener technologies, which will result in different changes in profits. But competition intensity drives carriers to implement greener shipping practices, which benefits both shippers and the whole society, as demonstrated in Proposition 3. However, too much subsidy may result in fiscal deficits for the government, which negatively impacts the economy and social welfare.

5.3. Carbon Emission Effect Analysis

Proposition 4. Optimal carbon emission satisfies (1) decrease in , increase in ; (2) .

Proposition 4 explores that in a price-competitive market, the increase in subsidy can lead to the reduction of carbon emission in different scenarios, which means that adopting low-emission technologies can be beneficial to abate carbon emission. Intense price competition may lead carriers to expand capacity, leading to overcapacity in the market. Excessive capacity not only wastes resources but also reduces load factors, further increasing carbon emission.

See Appendix of Proof for Proposition 4.

6. Numerical Analysis and Discussion

Based on the above theoretical analysis, next, we will conduct numerical simulation analysis to verify above lemmas and propositions in this section. We also try to explore the impact of different parameters under different scenarios, aiming to provide optimal strategies for carriers and the government. According to extant literature [

14,

37], we set some parameter assumptions as follows,

,

,

.

6.1. Optimal Price and Demand Analysis

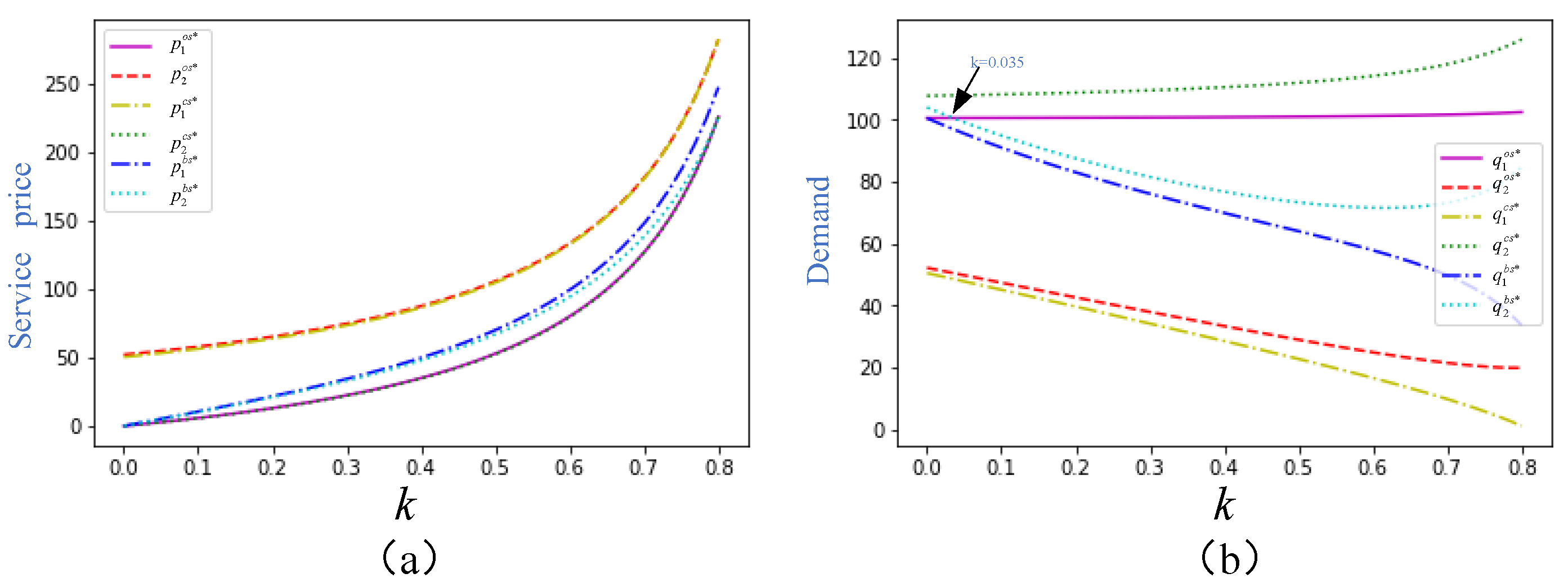

We can see that as

increases, service prices under different scenarios also rise, as depicted in

Figure 1(a). When

exceeds 0.5, most curves demonstrate a sharp increase, aligning with Proposition 1. This is because with subsidies, carriers are committed to investments in low-carbon technologies, and providing better transportation service to attract shippers, leading to the increase in prices.

Additionally, as competition intensifies, the demand for carrier 1 in Scenario OS and carrier 2 in Scenario CS gradually increases, while in Scenario BS, the demand for both carriers decline rapidly. Similarly, the demand for carrier 2 in Scenario OS and carrier 1 in Scenario CS drops sharply. Government subsidies may disrupt normal market competition, causing some carriers to rely on subsidies rather than focus on improving service efficiency. This weakens their competitiveness in the market, which may lead to a decline in shipping volume.

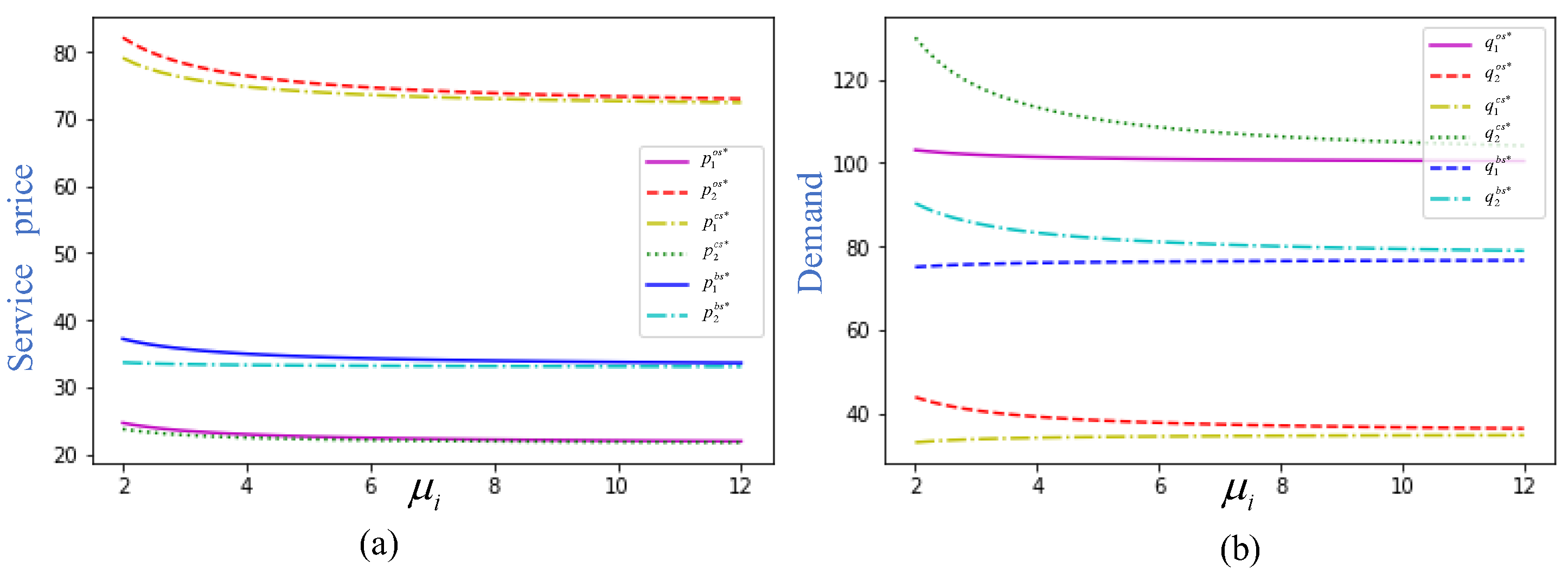

As

Figure 2(a) shows, an increase in subsidy level can lead to a reduction in service prices, aligning with Proposition 1. All curves are showing a gradually downward trend with the increase of subsidy level, as subsidies typically offset carriers’ operating costs, enabling them to invest in decarbonization and reduce service prices.

When is small and lower than 4, demand for carrier 2 in Scenario CS declines rapidly, while others show a trend of slow decline as is approaching the value of 12. Government subsidies can help lower carriers’ operational costs, allowing carriers to offer better transportation services, leading to more intense price competition. To maintain high profitability, carriers may reduce their transport volume through price cuts. In such a case, subsidies could reduce the overall market volume, as carriers, in an effort to ensure profitability, may cut back on the services they provide.

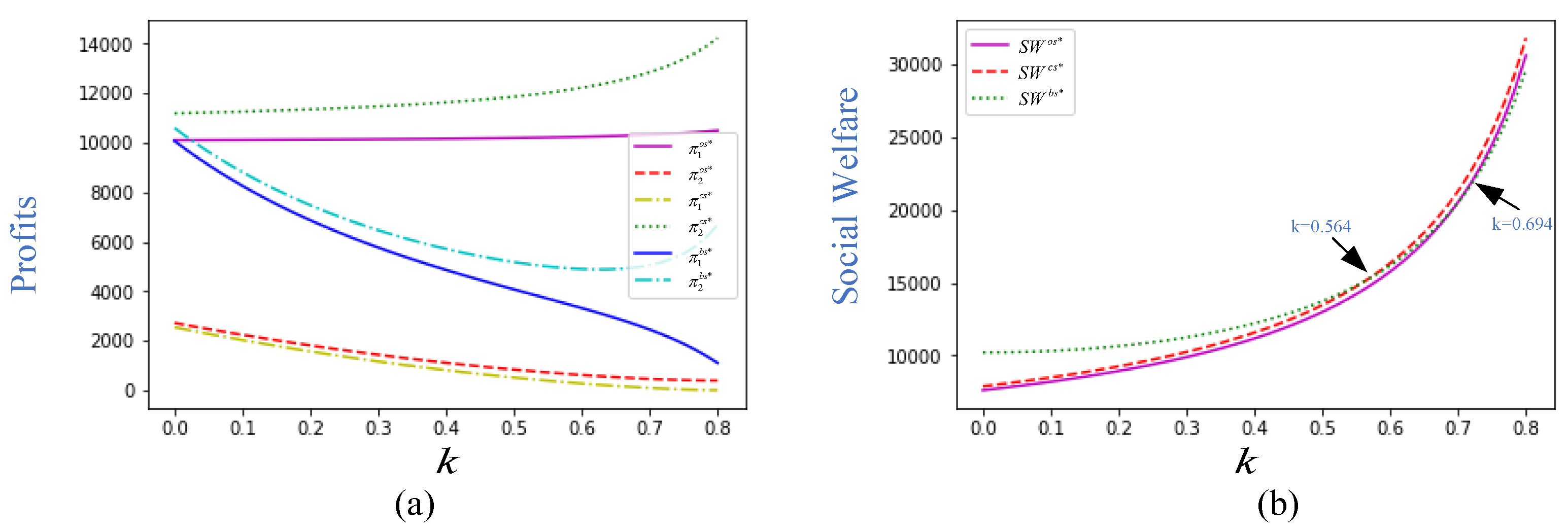

6.2. Optimal Profit and Social Welfare Analysis

Figure 3(a) shapes the profit dynamics for carriers under different scenarios with intensified competition. As competition intensifies, curves for carrier 1 in Scenario OS and carrier 2 in Scenario CS show an upward trend, while in Scenario BS, there is a sharp decline for both carriers, but with gradual downward trend for carrier 2 in Scenario OS and carrier 1 in Scenario CS, aligning with Proposition 2. This is because increased competition may drive carriers taking measures to abate carbon emission, improve service quality, leading to the decline of profits.

As the competition intensity increase, social welfare curves under different scenarios also rise, as shown in

Figure 3(b). And when

varies, social welfare also varies in different values. When

is lower than 0.694, social welfare in Scenario OS is the lowest. After the value 0.564 for

, social welfare in CS remains highest. When

is between 0.564 and 0.694, social welfare in Scenario BS is much higher than that in Scenario OS. This is because carriers that adopt greener technologies may increase social welfare by reducing environmental harm, leading to differences in social welfare outcomes.

In

Figure 4(a), we observe that with the increase in subsidies, profits exhibit varying trends. For Carrier 2 in Scenario OS and Carrier 1 in Scenario CS, profits grow very slowly because they do not receive subsidies. In contrast, Carrier 1 in Scenario OS and Scenario BS, along with Carrier 2 in Scenario CS and Scenario BS, show much higher profits due to receiving subsidies. As subsidies increase, most profits remain relatively unchanged because the subsidies offset the costs of environmental investments. However, the changes in profit decline for Carrier 2 in Scenario CS and Scenario BS are relatively small. This might be because the subsidies are used to offset operational costs, which could lead to customer loss or reduced demand, thereby affecting profits.

In

Figure 4(b), social welfare in all three scenarios decreases as

increases. In both Scenarios BS and OS, the decline in social welfare is relatively minor. In Scenario CS, social welfare drops sharply with the increase of the subsidy. When the subsidy level is lower than 3.779, social welfare in Scenario CS remains the highest, while after the value of 3.779 for subsidy level, social welfare in Scenario BS remains highest because both carriers are subsidized. Long-term subsidies may be a huge burden for the government, leading to technological stagnation, which could reduce overall social welfare.

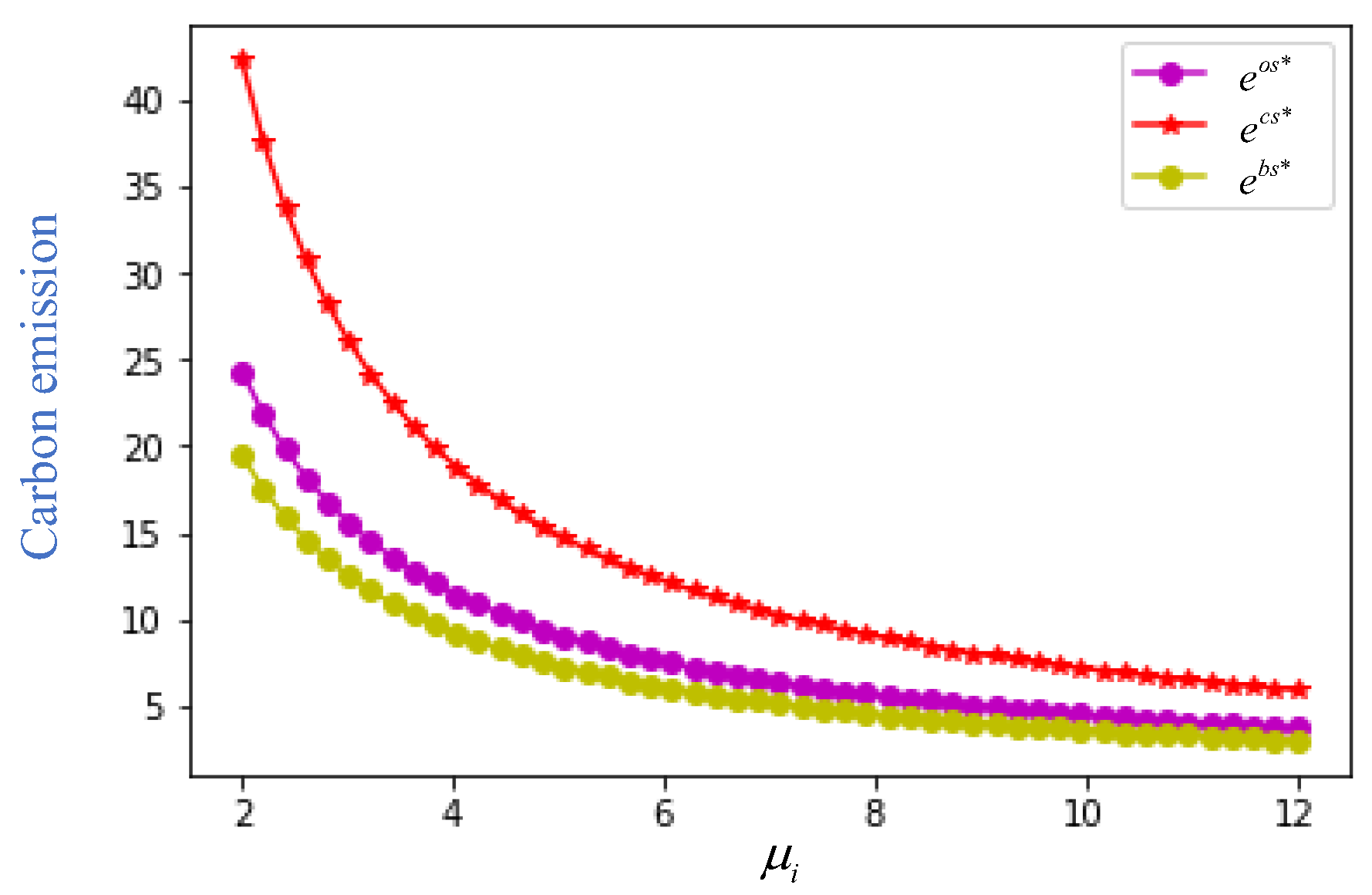

6.3. Optimal Carbon-Emission Analysis

From

Figure 5, it is evident that as subsidies improve, carbon emissions gradually decrease. When subsidy level is lower than 6, all curves show a significant decline. All curves exhibit relatively gentle trends when the value exceeds 6. This is because government subsidies allow carriers to adopt environmentally friendly technologies, resulting in reduced emissions of harmful gases, which contributes to lowering environmental pollution.

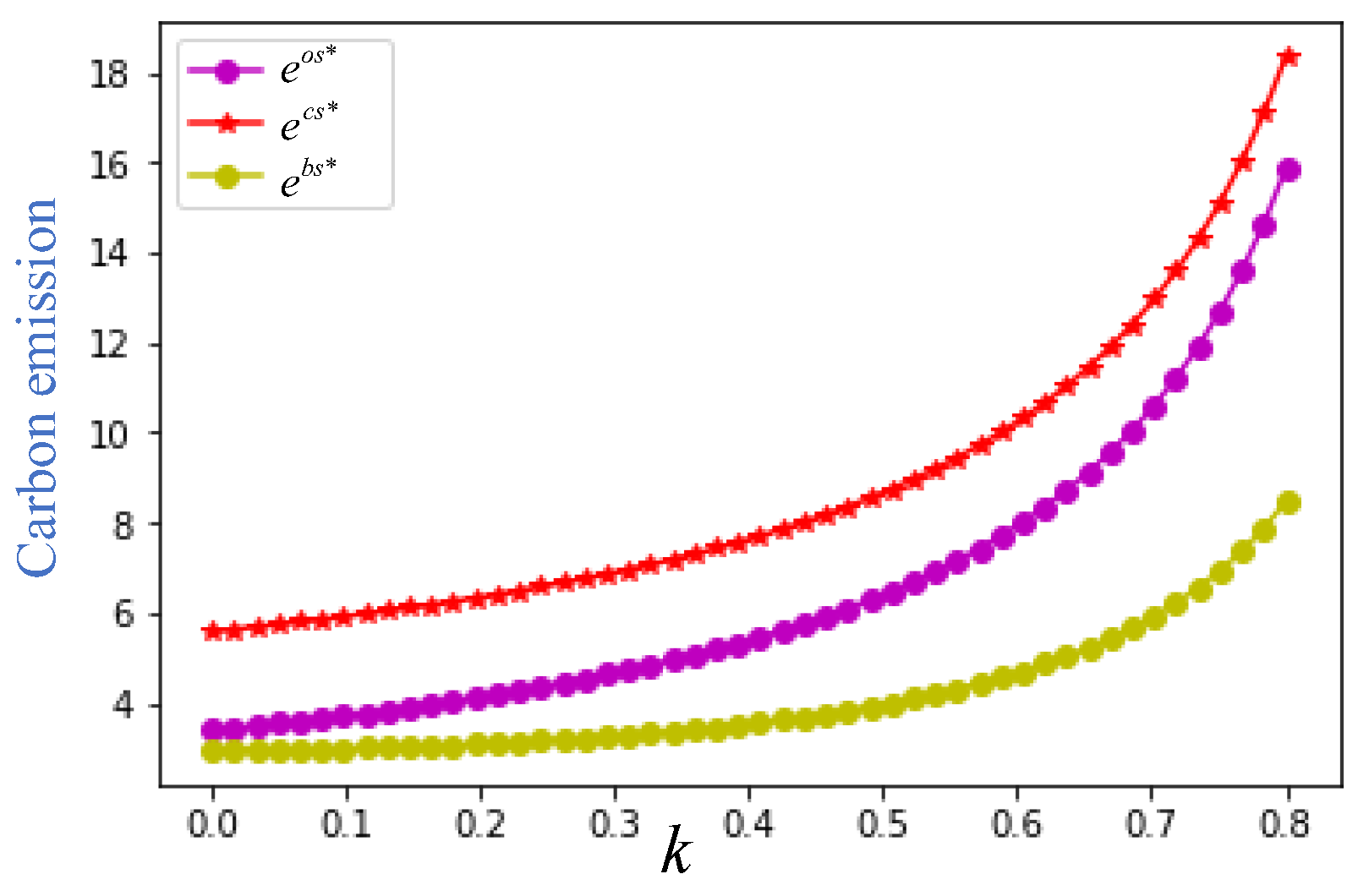

In some situations, competition among carriers can lead to increased carbon emissions, as shown in

Figure 6. In the initial stage, all curves are gradually rising, but after the value of 0.7, all curves show a trend of sharp rise. In Scenario BS, carbon emission remains the highest, while those in other scenarios remain lower, which is consistent with Proposition 4. Fierce price competition compels carriers to prioritize short-term market share, leading to operational models and technological choices that deviate from decarbonization goals and, as a result, increase carbon emissions.

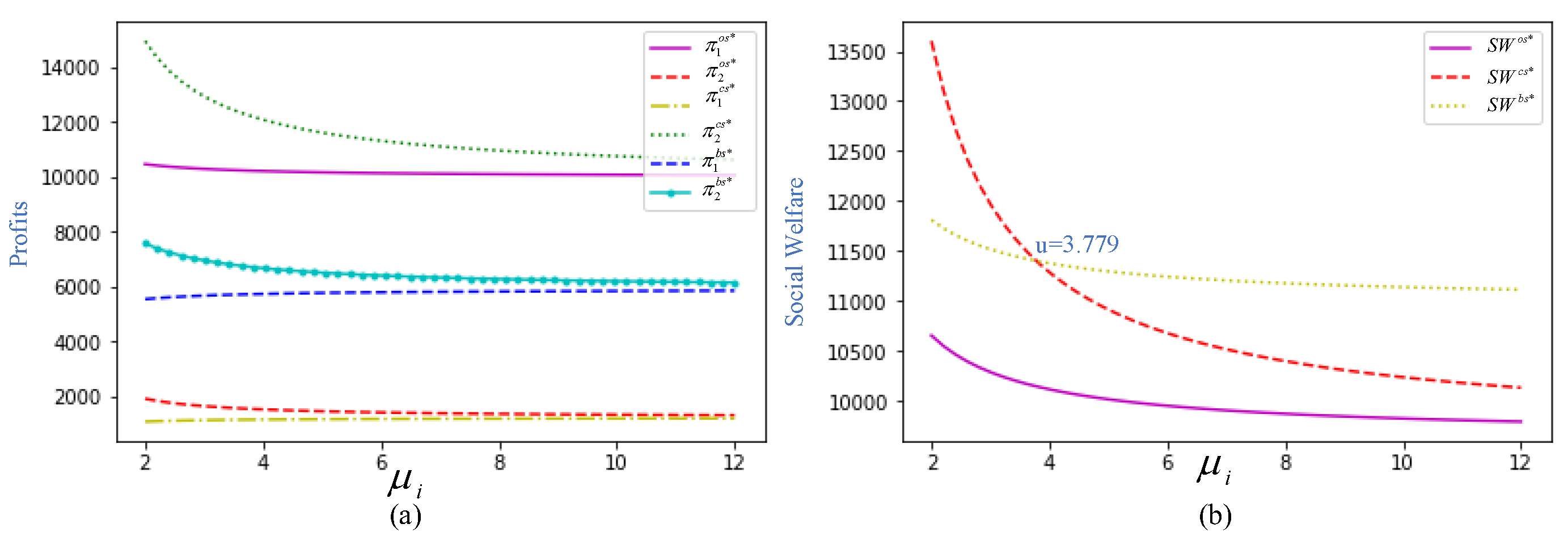

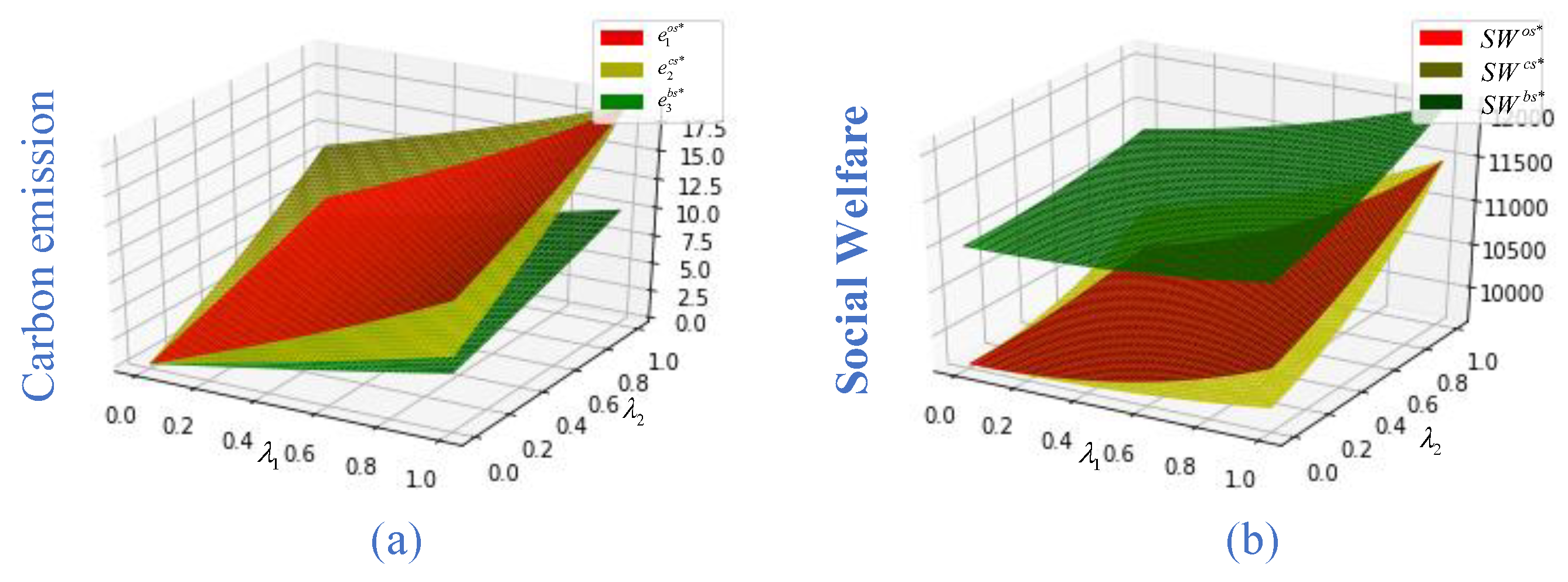

6.4. Analysis of the Impact of Shippers’ Green Preferences

Shippers are becoming increasingly inclined to prioritize environmental protection, and prefer carriers that can provide more sustainable services with faster delivery times, pushing carriers to increase sailing speeds. Speedier delivery also results in higher fuel consumption and, consequently, increased carbon emissions, as depicted in

Figure 7(a).

Figure 7(b) illustrates that all curves are increasing when environmental awareness from shippers increase. This is because if carriers take operational measures to protect the environment, such as use low-caron fuels, further enhancing social welfare.

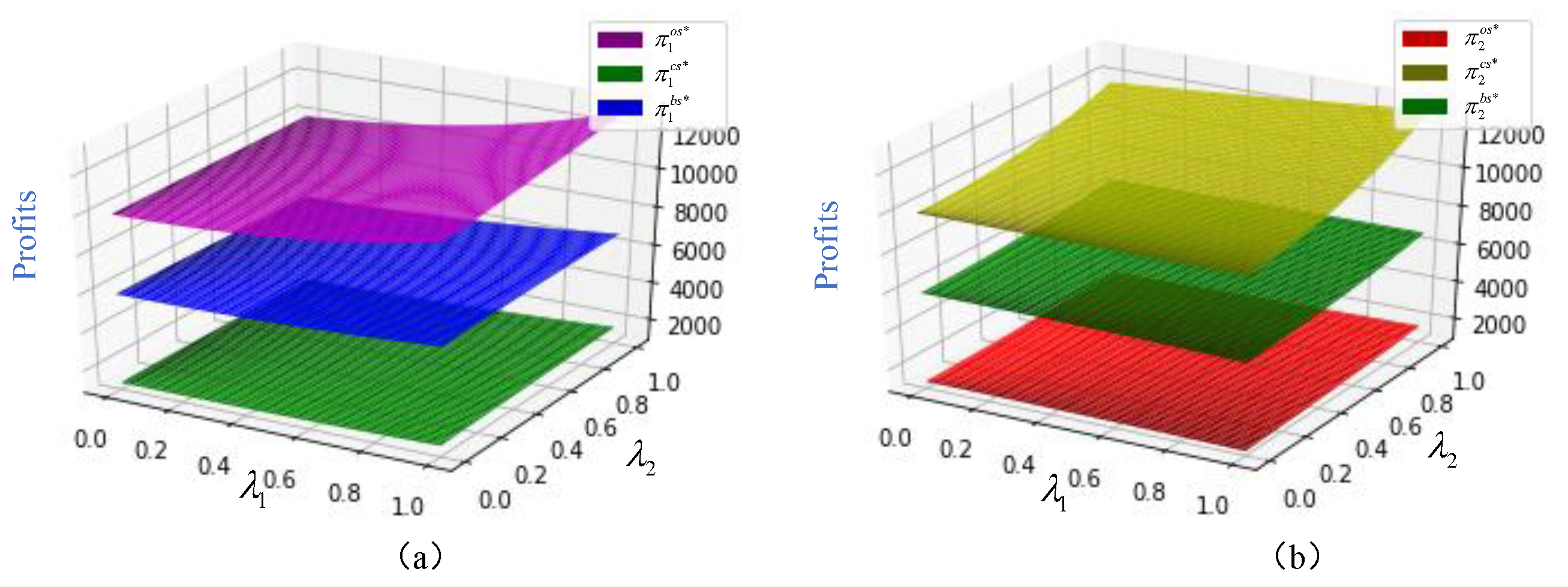

When green preference from shippers increases, profits for carriers under different scenarios also increase, as illustrated in

Figure 8. In competitive market, carriers with green transport options are more likely to secure contracts, leading to increased market share and revenue. Additionally, governments offer subsidies for green transportation. Shippers’ green preferences may drive carriers to adopt more eco-friendly practices, indirectly benefiting carriers through policy incentives. Furthermore, shippers with strong green preferences might be willing to pay higher prices to carriers who can provide more environmentally friendly services, thereby boosting carriers’ revenue.

7. Conclusions

Carriers play a crucial role in addressing global climate change and protecting marine ecosystems. However, transitioning to low-carbon technologies needs a huge investment for carriers, but they are reluctant to make the shift. Government incentives, a very efficient tool, can help carriers to invest in carbon emission reduction with the adoption of low-carbon technologies. Additionally, carriers also compete in price to attract more and more shippers, meanwhile, they also want to make profits through transportation services, which shippers are mainly focusing on.

In this paper, we considered a maritime supply chain consisting of shippers, two price-competitive carriers, a port and a government. Different models are constructed under three scenarios, in which profits of different partners and social welfare are evaluated. The impact of the competition, subsidy strategy and green preference on service prices, demand, profits, social welfare are also discussed.

We first study optimal strategies of each partner with carriers’ competition under three different scenarios. We find that increased competitive intensity between carriers can help increase prices, social welfare and carbon emission, but would lead to the decrease in demands and profits under some situation. Price competition compels carriers to take measures to improve service quality and achieve environmental sustainability.

We then identify the optimal subsidies under various conditions. Subsidies have shown effectiveness in decarbonization, and the government should provide subsidies to carriers in a price-competitive environment. Furthermore, subsidies are beneficial to decrease freight prices and social welfare, and alleviate carbon emission. Under most scenarios, subsidies are used to adopt low-carbon technologies, while carriers also want to provide better transportation service, leading to the decrease in profits and demands.

Finally, we extend the impact of the green preference from shippers on social welfare, carbon emission and profits. Our results demonstrate that when the green preference increases, social welfare, carbon emission and profits also increase. Because carriers endeavor to better transportation service, take more environmentally friendly measures, contributing to the improvement of carbon emission, social welfare and profits.

The findings of our paper can provide carriers or shipping companies a reference to choose carbon emission strategies when they compete in price. Results of our paper also help the government make optimal subsidy decisions and managerial insights to further alleviate carbon emission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y.(Lijuan Yang); methodology, L.Y.(Lijuan Yang); software, L.F.(Fangcheng Liao); validation, Y.H. (Yong He); formal analysis, L.Y.(Lijuan Yang); writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.(Lijuan Yang); writing—review and editing, L.Y.(Lijuan Yang); supervision, Y.H. (Yong He). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GUAT Special Research Project on the Strategic Development of Distinctive Interdisciplinary Fields (TS2024521) and Guangxi Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Project(21FGL025,23FYJ52).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 1:

With the back induction method, we firstly substitute

and

to the social welfare function (7). Taking second-order partial derivatives of

, Hessian matrix

on (

) can be written as follows:

With , we have,

, which means that is negative and jointly concave on , and . And optimal results , , , and can be derived. Additionally, let , , and , we can get and . Accordingly, , , , and can be obtained.

Proof of Lemma 2

Taking second-order partial derivatives of

on

, which yields:

When , we have, means that is negative and jointly concave on ().

let , and , we can get derive the following optimal results , , , and .

let , and , and can be obtained. So, we can get , , and .

Proof of Lemma 3

By solving second-order partial derivatives, Hessian matrix of

on

,

and

can be written as follows:

When ,we have,

means that is negative and jointly concave on ().

let , , and , we can get , , , , , , , , and .

Proof of Proposition 1

With

,

, and

, we can get:

Thus, Proposition 1 is proven.

Proof of Proposition 2

With

,

, and

, we can derive:

So, Proposition 2 is proven.

Therefore, Proposition 3 is proven.

Proof of proposition 4

With

,

and

, we can derive:

So, Proposition 4 is proven.

References

- Wang, C.; Jiao, Y.; Peng, J. Shipping company’s choice of shore power or low sulfur fuel oil under different power structures of maritime supply chain. Marit Policy Manag 2024, 51(7), 1423–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, Y.; Xie, X.; Turkmen, S.; Fan, S.; Ghassemi, H.; He, G. Achieving the global net-zero maritime shipping goal: The urgencies, challenges, regulatory measures and strategic solutions. Ocean Coast Manage 2024, 256, 107301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planakis, N.; Papalambrou, G.; Kyrtatos, N. Predictive power-split system of hybrid ship propulsion for energy management and emissions reduction. Control Eng. Pract 2021, 111, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Zheng, P. Dynamic analysis of a low-carbon maritime supply chain considering government policies and social preferences. Ocean Coast Manage 2023, 239, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lai, K.H. Role of carbon emission linked financial leasing in shipping decarbonization. Marit Policy Manag 2023, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhen, L. Optimal subsidy design for energy generation in ship berthing. Marit Policy Manag 2024, 51(8), 1824–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, C. Shore power vs low sulfur fuel oil: pricing strategies of carriers and port in a transport chain. Int J Low-Carbon Tec 2021, 16(3), 715–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, W. Analyzing the development of competition and cooperation among ocean carriers considering the impact of carbon tax policy. Transport Res E-Log 2023, 175, 103157. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Lin, X.; Li, E.Y.; Tavasszy, L. Lock congestion relief in a multimodal network with public subsidies and competitive carriers: a two-stage game model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 43707–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J. Carrier alliance incentive analysis and coordination in a maritime transport chain based on service competition. Transport Res E-Log 2019, 128, 333–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zou, Z. Sustainability investment in maritime supply chain with risk behavior and information sharing. Int J Prod Econ 2019, 218, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yu, Y.; Yin, J. Impact of Sulphur Emission Control Areas on port state control’s inspection outcome. Marit Policy Manag 2023, 50(7), 908–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Xie, Y. Blockchain technology investment strategy for shipping companies under competition. Ocean Coast Manage 2023, 243, 106696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, W. Choice of Emission Control Technology in Port Areas with Customers’ Low-Carbon Preference. Sustainability 2022, 14(21), 13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Wang, C. Privileged or ordinary carrier: strategic choice in a competitive environment. Marit Policy Manag 2024, 51(2), 240–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, G.; Xie, K. Using DPF to Control Particulate Matter Emissions from Ships to Ensure the Sustainable Development of the Shipping Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16(15), 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Xin, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, T. Investment and subsidy strategy for low-carbon port operation with blockchain adoption. Ocean Coast Manage 2024, 248, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surucu-Balci, E.; Iris, Ç.; Balci, G. Digital information in maritime supply chains with blockchain and cloud platforms: Supply chain capabilities, barriers, and research opportunities. Technol Forecast Soc 2024, 198, 122978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ölçer, A.I.; Ballini, F. Port greenhouse gas emission reduction: Port and public authorities’ implementation schemes. Res Transp Bus Manag 2022, 43, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Tang, W.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, G. Implications of government subsidies on shipping companies’ shore power usage strategies in port. Transport Res E-Log 2022, 165, 102840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L.; Wang, W.; Lin, S. Analytical comparison on two incentive policies for shore power equipped ships in berthing activities. Transport Res E-Log 2022, 161, 102686. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Zhou, Y.; Mu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Z. Subsidy, tax or green awareness: Government policy selection for promoting initial shore power usage and sustaining long-run use. J Clean Prod 2024, 442, 140946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Qi, S. Incentive policy for rail-water multimodal transport: Subsidizing price or constructing dry port? Transport Policy 2024, 150, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, P.; Staffell, I.; Kerdan, I.G.; Speirs, J.F.; Brandon, N.P.; Hawkes, A.D. How can LNG-fuelled ships meet decarbonisation targets? An environmental and economic analysis. Energy 2021, 227, 120462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S. The interplay between subsidy and regulation under competition. IEEE T Syst Man Cy 2022, 53(2), 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Lyu, Y. Emission reduction technologies for shipping supply chains under carbon tax with knowledge sharing. Ocean Coast Manage 2023, 246, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A.S.; Ölçer, A.I.; Ballini, F. Ports’ role in shipping decarbonisation: A common port incentive scheme for shipping greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Clean Logis Supply C 2022, 3, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, S.; Sys, C. Policies focusing on market-based measures towards shipping decarbonization: Designs, impacts and avenues for future research. Transport Policy 2023, 137, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.K.; Lam, J.S.L. CO2 emissions in a global container shipping network and policy implications. Marit Econ Logist 2024, 26(1), 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zheng, P.; Liu, G. Non-cooperative and Nash-bargaining game of a two-parallel maritime supply chain considering government subsidy and forwarder’s CSR strategy: A dynamic perspective. Chaos Soliton Fract 2024, 178, 114300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Z.; Du, Y. Coordinating inland river ports through optimal subsidies from the container shipping carrier. Transport Res E-Log 2024, 189, 103671. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhou, G. Dual-channel green supply chain management with eco-label policy: A perspective of two types of green products. Comput Ind Eng 2020, 146, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, G. Two-stage pricing strategies of a dual-channel supply chain considering public green preference. Comput Ind Eng 2021, 151, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Shi, V.; Sun, Q. Manufacturer’s choice of online selling format in a dual-channel supply chain with green products. Eur J Oper Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Service purchasing and market-entry problems in a shipping supply chain. Transport Res E-Log 2020, 136, 101895. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D.; Guo, R.; Lan, Y.; Shang, C. Shareholding strategies for selling green products on online platforms in a two-echelon supply chain. Transport Res E-Log 2021, 149, 102261. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Tumpa, T.J.; Rifat, A.A.; Paul, S.K. Examining price and service competition among retailers in a supply chain under potential demand disruption. J Retail Consum Serv 2018, 40, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, F. Emission abatement in low-carbon supply chains with government subsidy and information asymmetry. Int J Prod Res 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Johari, M.; Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M. Coordination of social welfare, collecting, recycling and pricing decisions in a competitive sustainable closed-loop supply chain: a case for lead-acid battery. Ann Oper Res 2019, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Cheng, P.; Zhen, L. Green development of the maritime industry: Overview, perspectives, and future research opportunities. Transport Res E-Log 2023, 179, 103322. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, N. The evasion strategy options for competitive ocean carriers under the EU ETS. Transport Res E-Log 2024, 183, 103439. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhuge, D.; Psaraftis, H.N.; Wang, S. Subsidy strategy design for shore power utilization and promotion. Marit Policy Manag 2024, 51(8), 1606–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, D.; Wang, S.; Zhen, L. Shipping emission control area optimization considering carbon emission reduction. Oper Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).