Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

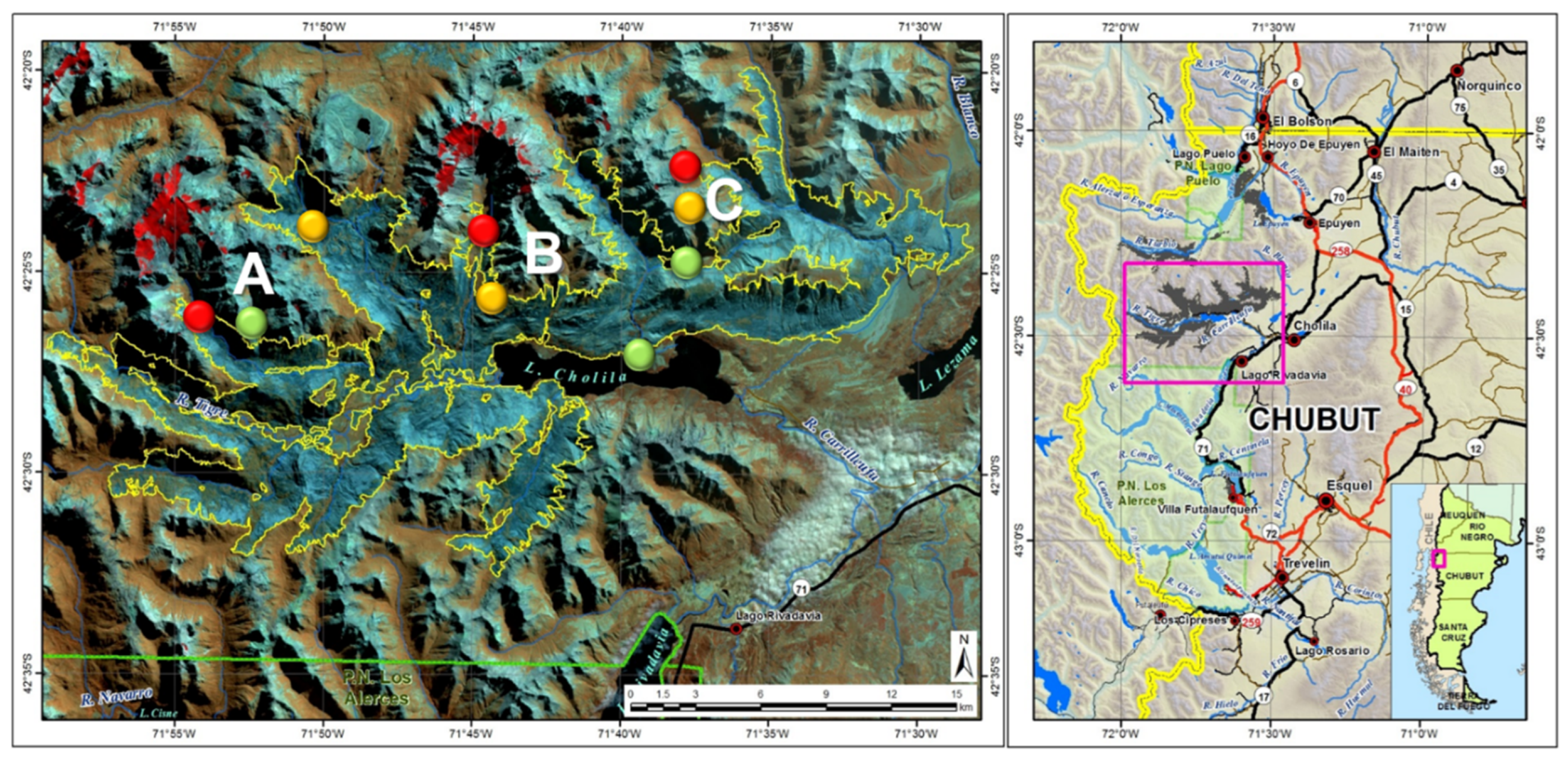

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. Sample Processing; Spore and Soil Analyses

2.4. Bioassay Setup

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

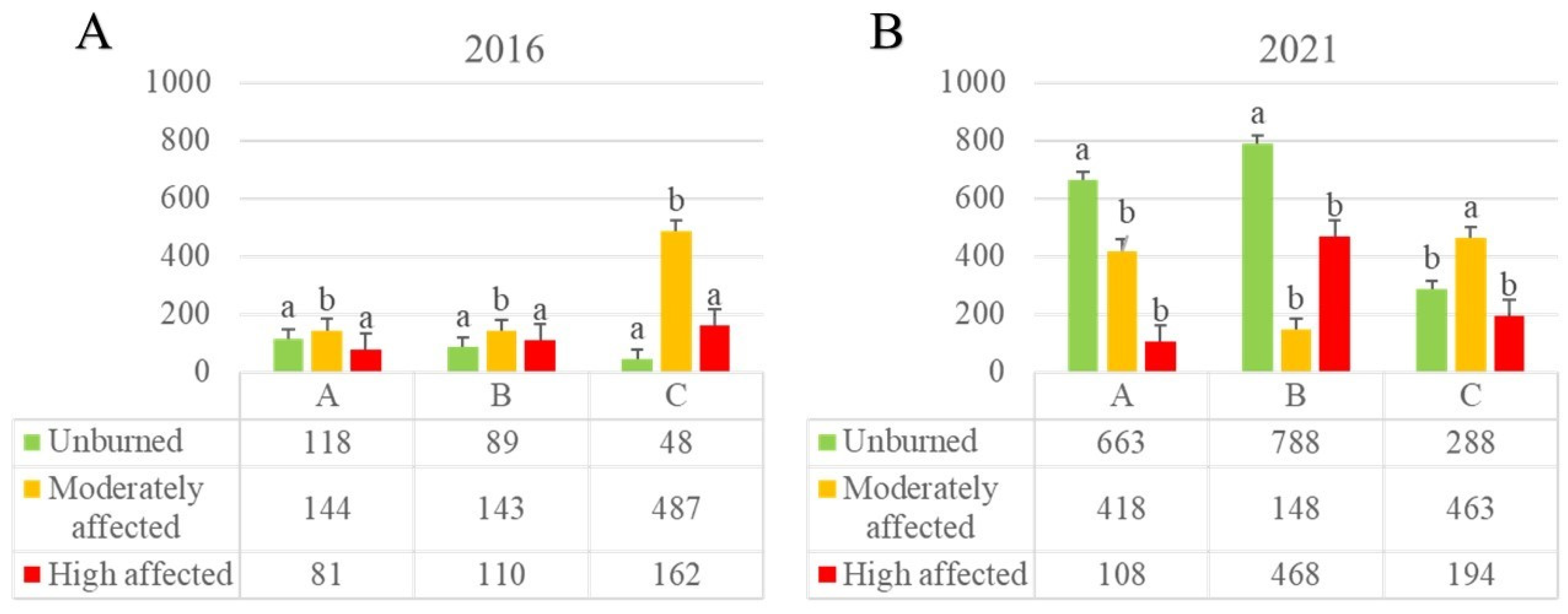

3.1. Analyses of Soil AMS Densities and Soil Variables

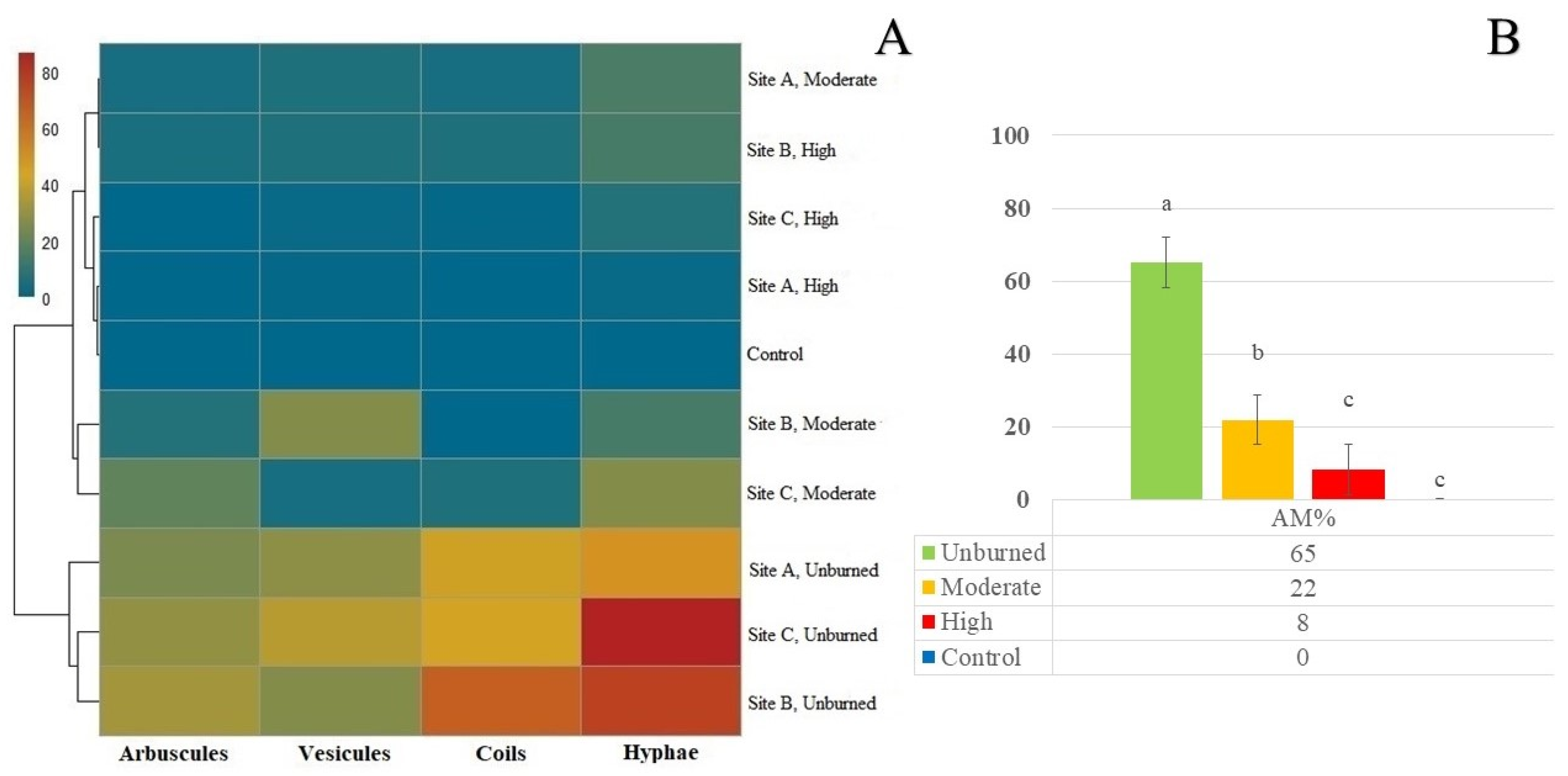

3.2. Seedlings AM Colonization from Soil Bioassay

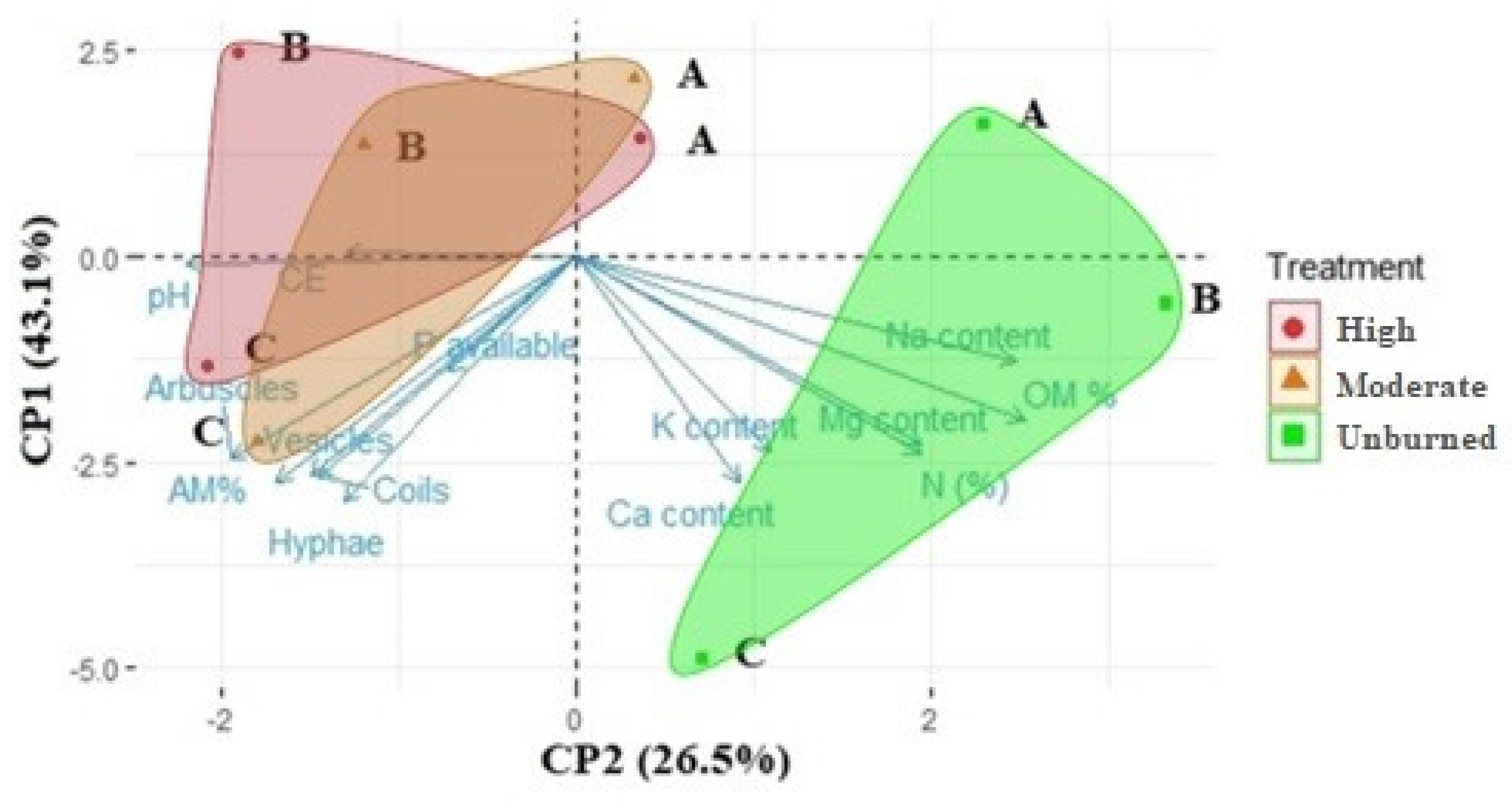

3.3. Relationships Between Seedlings AM Colonization, Spore Density and Soil Features

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMF | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| AMS | Arbuscular mycorrhizal spores |

| AM% | Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization percentaje |

| WFS | Wildfire severity |

| AM | Arbuscular mycorrhiza |

| OM | Soil organic matter |

| N | Soil Nitrogen content |

| EC | Soil Electrical conductivity |

| C/N | Soil carbon nitrogen ratio |

| 2W-GLMM | Two-way general linear mix model |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Veblen, T.T., Kitzberger, T., Villalva, R., Donnegan, J. Fire History in Northern Patagonia: The Roles of Humans and Climatic Variation. Ecol Monogr, 1999, 69(1), 47–67. [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S., Chatzitheodoridis, F., Kalfas, D., Patitsa, C., Papagrigoriou, A. Socio-Psychological, Economic and Environmental Effects of Forest Fires. Fire, 2023, 6, 280. [CrossRef]

- Kitzberger, T., Veblen, T.T., Fire-induced changes in northern Patagonian landscapes. Landsc Ecol, 1999, 14, 1–15 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1008069712826. [CrossRef]

- de Torres Curth, M.I., Ghermandi, L., Pfister, G. Los incendios en el noroeste de la Patagonia: su relación con las condiciones meteorológicas y la presión antrópica a lo largo de 20 años. Ecología Austral, 2008, 18, 153–167. [CrossRef]

- Mohr Bell, D. Superficies afectadas por incendios en la región Bosque Andino Patagónico durante los veranos de 2013-2014 y 2014-2015. Nodo Regional Bosque Andino Patagónico (SAyDS -CIEFAP). 2015.

- Kitzberger, T., Tiribelli, F., Barberá, I., Gowda, J.H., Morales, J.M., Zalazar, L., Paritsis, J. Projections of fire probability and ecosystem vulnerability under 21st century climate across a trans-Andean productivity gradient in Patagonia. Sci Total Environ, 2022, 839, 156303. [CrossRef]

- Barros. V.R., Boninsegna, J.A., Camilloni, I.A., Chidiak, M., Magrín, G.O., Rusticucci, M. Climate change in Argentina: trends, projections, impacts and adaptation. WIREs Clim Change, 2015, 6(2), 151–169. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.). Cambridge University Press. 2021.

- González, M.E., Lara, A., Urrutia, R., Bosnich, J. Cambio climático y su impacto potencial en la ocurrencia de incendios forestales en la zona centro-sur de Chile (33º-42º S). Bosque, 2011, 32(3), 215–219. [CrossRef]

- Mundo, I.A., Villalba, R., Veblen, T.T., Kitzberger, T., Holz, A., Paritsis, J., Ripalta, A. Fire history in southern Patagonia: human and climate influences on fire activity in Nothofagus pumilio forests. Ecosphere, 2017, 8(9), e01932. [CrossRef]

- Urretavizcaya, M.F., Defossé, G.E. Restoration of burned and post-fire logged Austrocedrus chilensis stands in Patagonia: effects of competition and environmental conditions on seedling survival and growth. Int. J. Wildland Fire, 2019, 28(5), 365. [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, M.J., Fariña, M.M., Bran, D., Gallo, L.A. Extremos geográficos de la distribución natural de Austrocedrus chilensis (Cupressaceae). Boletín de la SAB, 2006, 41, 307–311.

- Urretavizcaya, M.F.; Defossé, G. Soil seed bank of Austrocedrus chilensis (D. Don) Pic. Serm. et Bizarri related to different degrees of fire disturbance in two sites of southern Patagonia, Argentina. Forest Ecol Manag, 2004, 187, 361-372. [CrossRef]

- López Bernal, P.M., Urretavizcaya, M.F., Defossé, G.E. Seedling dynamics in an environmental gradient of Andean Patagonia, Argentina. In From seed germination to young plants: ecology, growth and environmental influences; Busso, C.A., Ed.; Publisher: Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY, 2013, pp. 189–210.

- Gallo, L., Pastorino, M.J., Donoso, C. Variación en Austrocedrus chilensis (D. Don) Pic. Ser et Bizzarri (Ciprés de la Cordillera). In Variación intraespecífica en las especies arbóreas de los bosques templados de Chile y Argentina; Donoso, C., Premoli, A., Gallo, L., Ipinza, R., Eds.; Publisher: Marisa Cuneo, Valdivia, Chile, 2004, pp. 233–250.

- La Manna, L., Bava, J., Collantes, M., Rajchenberg, M. Características estructurales de los bosques de Austrocedrus chilensis afectados por “mal del ciprés” en Patagonia, Argentina. Bosque, 2006, 27(2), 135–145.

- Gobbi, M., Sancholuz, L. Regeneración pos-incendio del ciprés de la cordillera (Austrocedrus chilensis) en los primeros años. Bosque, 1992, 13(2), 25–32.

- CIEFAP, MAyDS. Actualización de la Clasificación de Tipos Forestales y Cobertura del Suelo de la Región Bosque Andino Patagónico. Informe Final https://drive.google.com/open?id=0BxfNQUtfxxeaUHNCQm9lYmk5RnM CIEFAP. 2016, 111 p.

- Bava, J., Lencinas, J.D., Haag, A. Determinación de la materia prima disponible para proyectos de inversión forestales en cuencas de la provincia del Chubut. Informe Parcial. Consejo Federal de Inversiones. 2006, 85 pp.

- Morales, D., Rostagno, C.M., La Manna, L. Runoff and erosion from volcanic soils affected by fire: The case of Austrocedrus chilensis forests in Patagonia. Argentina. Plant Soil, 2013, 370(1), 367–380. [CrossRef]

- Vélez, M.L., La Manna, L., Tarabini, M., Gomez, F., Elliott, M., Hedley, P.E., Cock, P., Greslebin, A. Phytophthora austrocedri in Argentina and co-inhabiting Phytophthoras: Roles of anthropogenic and abiotic factors in species distribution and diversity. Forests, 2020, 11(11), 1223. [CrossRef]

- Orellana, I.A., Raffaele, E. The spread of the exotic conifer Pseudotsuga menziesii in Austrocedrus chilensis forests and shrublands in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. N Z J For Sci, 2020, 40, 199–209.

- Urretavizcaya, M.F. Propiedades del suelo en bosques quemados de Austrocedrus chilensis en Patagonia, Argentina. Bosque, 2010, 31(2), 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Loguercio, G.A., Urretavizcaya, M.F., Caselli, M., Defossé, G.E. Propuestas silviculturales para el manejo de bosques de Austrocedrus chilensis sanos y afectados por el mal del ciprés de Argentina. In Silvicultura en bosques nativos. Experiencias en silvicultura y restauración en Chile, Argentina y el oeste de Estados Unidos; Donoso, P.J., Promis, A., Soto, D.P., Eds.; Publisher: Imprenta América, Valdivia, Chile, 2018, pp. 117–134. () ISBN 978–0-692–09238–5.

- Godoy, R., Mayr, R. Caracterización morfológica de micorrizas vesículo-arbusculares en coníferas endémicas del sur de Chile. Bosque, 1989, 10(2), 89–98.

- Fontenla, S., Godoy, R., Rosso, P., Havrylenko, M. Root associations in Austrocedrus forests and seasonal dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizas. Mycorrhiza, 1998, 8, 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E., Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. 3th ed. Publisher: Academic Press, Cambridge, UK, 2008, 145–187.

- Sendek, A., Karakoç, C., Wagg, C., Domínguez-Begines, J., Martucci do Couto, G., van der Heijden, M.G.A., Ahmad Naz, A., Lochner, A., Chatzinotas, A., Klotz, S., Gómez-Aparicio, L., Eisenhauer, N. Drought modulates interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity and barley genotype diversity. Sci Rep, 2019, 9, 9650. [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M., Bitterlich, M., Jansa, J., Püschel, D., Ahmed, M.A. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in improving plant water status under drought. J Exp Bot, 2023, 74(16), 4808–4824. [CrossRef]

- Veresoglou, S. D., Rillig, M. C. Suppression of fungal and nematode plant pathogens through arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Biol Lett, 2012, 8(2), 214–217. [CrossRef]

- Willis, A., Rodrigues, B. F., Harris, P. J. C. The ecology of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Crit Rev Plant Sci, 2013, 32(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Powell, J. R., Rillig, M. C. Biodiversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and ecosystem function. New Phytol, 2018, 220(4), 1059–1075. [CrossRef]

- Neuenkamp, L., Prober, S. M., Price, J. N., Zobel, M., Standish, R. J. Benefits of mycorrhizal inoculation to ecological restoration depend on plant functional type, restoration context and time. Fungal Ecol, 2019, 40, 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Longo, S., Nouhra, E., Goto, B. T., Berbara, R. L., Urcelay, C. Effects of fire on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the Mountain Chaco Forest. For Ecol Manage, 2014, 315, 86–94. [CrossRef]

- Cofré, N., Urcelay, C., Wall, L. G., Domínguez, L., Becerra, A. El potencial de colonización micorrícico-arbuscular varía entre prácticas agrícolas y sitios en diferentes áreas geográficas de la región Pampeana. Ecología Austral, 2018, 28(3), 581–592.

- Day, N.J., Dunfield, K.E., Johnstone, J.F., Mack, M.C., Turetsky, M.R., Walker, X.J., Baltzer, J.L. Wildfire severity reduces richness and alters composition of soil fungal communities in boreal forests of western Canada. Global Change Biol, 2019, 25(7), 2310–2324. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X., Gibbons, S.M., Yang, J., Kong, J., Sun, R., Chu, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities show low resistance and high resilience to wildfire disturbance. Plant Soil, 2015, 397, 347–356. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Miller, J.B., Granqvist, E., Wiley-Kalil, A., Gobbato, E., Maillet, F., Maillet, F., Cottaz, S., Samain, E., Venkateshwaran, M., Fort, S., Morris, R. J., Ané, J., Dénarié, J., Oldroyd, G.E. Activation of symbiosis signaling by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in legumes and rice. Plant Cell, 2015, 27(3), 823–838. [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.R., Rogers, B.M., Treseder, K.K., Randerson, J.T. Fire severity influences the response of soil microbes to a boreal forest fire. Environ Res Lett, 2016, 11(3), 035004. [CrossRef]

- Claridge, A. W., Trappe, J. M., Hansen, K. Do fungi have a role as soil stabilizers and remediators after forest fire? For Ecol Manage, 2009, 257(3), 1063–1069. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., Ahmed, T., Ayub, N., Khan, A.G. Effect of forest fire on number, viability and post-fire re-establishment of arbuscular mycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza, 1997, 7, 217–220. [CrossRef]

- de Assis, D.M.A., De Melo, M.A.C., da Silva, D.K.A., Oehl, F., da Silva, G.A. Assemblages of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in tropical humid and dry forests in the Northeast of Brazil. Botany, 2018, 96(12), 859–871. [CrossRef]

- Orgiazzi, A., Bardgett, R.D., Barrios, E., Behan-Pelletier, V., Briones, M.J.I., Chotte, J-L., De Deyn, G.B., Eggleton, P., Fierer, N., Fraser, T., Hedlund, K., Jeffery, S., Johnson, N.C., Jones, A., Kandeler, E., Kaneko, N., Lavelle, P., Lemanceau, P., Miko, L., Montanarella, L., Moreira, F. M. S., Ramírez, K.S., Scheu, S., Singh, B.K., Six, J., van der Putten, W.H., Wall, D. H. (Eds.) Global soil biodiversity atlas. European Commission. European Commission, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2016, 176 pp.

- Whitman, T., Whitman, E., Woolet, J., Flannigan, M.D., Thompson, D.K., Parisien, M.A. Soil bacterial and fungal response to wildfires in the Canadian boreal forest across a burn severity gradient. Soil Biol Biochem, 2019, 138, 107571. [CrossRef]

- Dove, N.C., Hart, S.C. Fire reduces fungal species richness and in situ mycorrhizal colonization: a meta-analysis. Fire Ecol, 2017, 13(2), 37–65. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R., Sharma, S. Climate resilient microbes in sustainable crop production. In Contaminants in Agriculture and Environment: Health Risks and Remediation; Kumar, V., Kumar, R., Singh, J., Kumar, P, Eds.; Publisher: Agro Environ Media, Publication Cell, Agriculture and Environmental Science Academy, Haridwar (Uttarakhand), India, 2019, 265–283pp.

- Johnson, N.C., Tilman, D., Wedin, D. Plant and soil controls on mycorrhizal fungal communities. Ecology, 1992, 73, 2034–2042.

- Egerton-Warburton, L.M., Johnson, N.C., Allen, E.B. Mycorrhizal community dynamics following nitrogen fertilization: A cross-site test in five grasslands. Ecol Monogr, 2007, 77, 527–544. [CrossRef]

- Lekberg, Y., Gibbons, S.M., Rosendahl, S., Ramsey, P.W. Severe plant invasions can increase mycorrhizal fungal abundance and diversity. ISME J, 2013, 7, 1424–1433. [CrossRef]

- Egan, C., Li, D.-W., Klironomos, J. Detection of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores in the air across different biomes and ecoregions. Fungal Ecol, 2014, 12, 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Urretavizcaya, M.F., Rago, M.M., Caselli, M., Ríos Campano, F., Gianolini, S., Alonso, V. Effect of fire severity and presence of bamboo (Chusquea culeou) on soil chemical properties in Andean Patagonian forests of Argentina. Int J Wildland Fire, 2025, 34, WF24011. [CrossRef]

- SUIE 2002 Sistema Unificado de Información Energética (SUIE). Secretaría de Energía de la Nación Argentina. 2002. Mapa de Isohietas República Argentina. Available in: https://sig.energia.gob.ar/visor/visorsig.php. Visited in December of 2023.

- Ianson, D.C., Allen, M.F. The Effects of soil texture on extraction of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores from arid sites. Mycologia, 1986, 78(2),164–168. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.F., Moore, Jr., T.S., Christensen, M., Stanton, N. America growth of Vesicular-Arbuscular-Mycorrhizal and Nonmycorrhizal Bouteloua gracilis in a defined medium. Mycologia, 1979, Vol. 71(3), 666–669. [CrossRef]

- Bailey W. Soil Science. In Análisis químico de suelos; Jackson M.L., Ed.; Publisher: Ediciones Omega S.A. Barcelona, 1943, 55-143.

- Allison, L.E. Diagnóstico y rehabilitación de suelos salinos y sódicos. Publisher: Editorial Limusa, México, 1980.

- Davies, B E. Loss-on ignition as an estimate of soil organic matter. Soil Sci Proc, 1974, 38, 150. [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Soil Organic Matter Testing: An Overview. In Soil organic matter: analysis and interpretation; Magdoff, F.R.; Tabatabai, M.A., Hanlon Jr., E.A-, Eds.; Publisher: Soil Science Society of America, Madison, USA, 1996, 1–9.

- Bremmer JM. Determination of Nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J Agr Sci, 1960, 55, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R., Cole, D.V., Watanabe, F.S., Dean, L.A. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. U.S.D.A. 939, USA, 1954, pp 19.

- Elrashidi, M.A. Soil and Water Conservation Advances in the United States: A review. J Soil Water Conserv, 2011, 66(1), 5A. [CrossRef]

- Richter, M., Conti, M., Maccarini, G. Mejoras en la determinación de cationes intercambiables y capacidad de intercambio catiónico en los suelos. Rev Fac Agronomía, 1982, 3(2), 145–155.

- Schollenber, C.J., Simon, R.H. Determination of exchange capacity and exchangeable bases in soil - ammnium acetate method. Soil Sci, 1945, 59,13–25.

- Sauer, D.B., Burroughs, R. Disinfection of seed surfaces with sodium hypochlorite. Phytopathology, 1986, 76(7),745–749.

- Schinelli Casares T. Producción de Nothofagus bajo condiciones controladas. Publisher: Ediciones INTA, Bariloche, Argentina, 2012, 52pp.

- van der Heijden, M.G.A., Klironomos, J.N., Ursic, M., Moutoglis, P., Streitwolf-Engel, R., Boller, T., Wiemken, A., Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Letter to Nature, 1998, 396, 69–72. [CrossRef]

- Cázares, E., Smith, J.E. Ocurrence of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in Pseudotsuga menziesii and Tsuga heterophylla seedlings grown in Oregon coast range soil. Mycorrhiza, 1996, 6, 65–67. [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M., Bougher, N., Grove, T., Malajczuk, N. Working with mycorrhizas in forestry and agriculture. Australian Center for International Agricultural Reserch, Monograph 32. Canberra, Australia, 1996, 374pp.

- Di Rienzo, J.A., Macchiavelli, R.E., Casanoves, F. Modelos Mixtos en InfoStat. Manual del Usuario; Publisher: Editorial Brujas, Córdoba, Argentina, 2010.

- Di Rienzo, J.A., Casanoves, F., Balzarini, M.G., Gonzalez, L., Tablada, M., Robledo, C.W. InfoStat versión 2020. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina, 2020. URL: http://www.infostat.com.ar.

- RStudio Team. Posit team RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA. 2022, URL http://www.posit.co/.

- Carrillo, R., Godoy, R., Peredo, H. Simbiosis micorrícica en comunidades boscosas del Valle Central en el sur de Chile. Bosque, 1992, 13(2), 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Dhillion, S.S., Anderson, DC. Seasonal dynamics of dominant species of arbuscular mycorrhizae in burned and unburned sand prairies. Can J Bot, 1993, 71, 1625–1630. [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, G.S., Hammill, K.A., Sutton, B.G., McGee, P.A. Simulated fire reduces the density of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi at the soil surface. Mycol Res, 1999, 103(4), 491–496. [CrossRef]

- Eom, A.-H., Hartnett, D.C., Wilson, G.W.T., Figge, D.A.H. The effect of fire, mowing and fertilizer amendment on arbuscular mycorrhizas in Tallgrass Prairie. Am Midl Nat, 1999, 142, 55–70. [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.B., Steers, R.J., Dickens, S.J. Impacts of fire and invasive species on desert soil ecology. Rangeland Ecol Manage, 2011, 64(5), 450–462. [CrossRef]

- Bouffaud, M.-L., Bragalini, C., Berruti, A., Peyret-Guzzon, M., Voyron, S., Stockinger, H., van Tuinen, D., Lumini, E., Wipf, D., Plassart, P., Lemanceau, P., Bianciotto, V., Redecker, D., Girlanda, M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community differences among European long-term observatories. Mycorrhiza, 2017, 27,331–343. [CrossRef]

- Soudzilovskaia, N.A., Vaessen, S., Barcelo, M., He, J., Rahimlou, S., Abarenkov, K., Brundrett, M.C., Gomes, S.I.F., Merckx, V., Tedersoo, L. FungalRoot: Global online database of plant mycorrhizal associations. New Phytol, 2020, 227, 955–966. [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.G., Klopatek, C.C., DeBano, L.F., Folliott, P.F. Fire effects on belowground sustainability: a review and synthesis. For. Ecol. Manag, 1999, 122, 51–71. [CrossRef]

- Chimal-Sánchez, E., Araiza-Jacinto, M.L., Román-Cárdenas, V.J. El efecto del fuego en la riqueza de especies de hongos micorrizógenos arbusculares asociada a plantas de matorral xerófilo en el Parque Ecológico “Cubitos”. Revista Especializada en Ciencias Químico-Biológicas, 2015, 18(2),107–115. [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, A.D., Olsson, P.A. Slash-and-burn practices decrease arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi abundance in soil and the roots of Didierea madagascariensis in the dry tropical forest of Madagascar. Fire, 2018, 1, 37. [CrossRef]

- Chávez, D., Machuca, A., Fuentes-Ramirez, A., Fernandez, N., Cornejo, P. Shifts in soil traits and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis represent the conservation status of Araucaria araucana forests and the effects after fire events. For Ecol Manage, 2020, 458, 117806. [CrossRef]

- Kivlin, S.N., Harpe. V.R., Turner, J.H., Moore, J.A.M., Moorhead, L.C., Beals, K.K., Hubert, M.M., Papes, M., Schweitzer, J.A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal response to fire and urbanization in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Elem Sci Anth, 2021, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Mino, L., Kolp, M.R., Fox, S., Reazin C., Zeglin, L., Jumpponen, A. Watershed and fire severity are stronger determinants of soil chemistry and microbiomes than within-watershed woody encroachment in a tallgrass prairie system. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2021, 97(12), fiab154. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.R., McKenna, T.P., Bennett, AE. 2024. Fire season and time since fire determine arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal trait responses to fire. Plant Soil, 2024, 503, 231–245. [CrossRef]

- Docherty, K.M., Balser, T.C., Bohannan, B.J.M., Gutknecht, J.L.M. Soil microbial responses to fire and interacting global change factors in a California annual grassland. Biogeochemistry, 2012, 109,63–83. [CrossRef]

- Longo, S., Nouhra, E., Tecco, P.A., Urcelay, C. Functional stability of mycorrhizal interactions in woody natives and aliens facing fire disturbance. Plan Ecol, 2020, 221, 321–331. [CrossRef]

- Stürmer, S.L., Hackbarth Heinz, K.G., Marascalchi, M.N., Giongo, A., Siqueira, J.O. Wildfire does not affect spore abundance, species richness, and inoculum potential of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) in ferruginous Canga ecosystems. Acta Bot Brasil, 2022, 36, e2021abb0218. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M., Baretta, D., Tsai, S.M., Nogueira Cardoso, E.J.B. Spore density and root colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in preserved or disturbed Araucaria angustifolia (Bert.) O. Ktze. Ecosystems. Sci. Agric. (Piracicaba, Braz.), 2006, 63(4), 380-385. [CrossRef]

- Urretavizcaya, M.F., Defossé, G.E., Gonda, H.E. Effect of sowing season, plant cover, and climatic variability on seedling emergence and survival in burned Austrocedrus chilensis forests. Restor Ecol, 2012, 20(1), 131–140. [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M., Schlichter, T. Survival of Austrocedrus chilensis seedlings in relation to microsite conditions and forest thinning. For Ecol Manage, 1998, 111, 137–146. [CrossRef]

- La Manna, L., Barroetaveña, C. Propiedades químicas del suelo en bosques de Nothofagus antarctica y Austrocedrus chilensis afectados por fuego. Rev. FCA UNCUYO, 2011, 43(1), 41–55.

- Marín, C., Aguilera, P., Oehl, F., Godoy, R. Factors affecting arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi of Chilean temperate rainforests. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr, 2017, 17 (4), 966–984. [CrossRef]

- Begum, N., Qin, C., Ahanger, M.A., Raza, S., Khan, M.I., Ashraf, M., Ahmed, N., Zhang, L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci, 2019, 10, 1068. [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, M., Outeiro, L., Francos, M., Úbeda, X. Effects of prescribed fires on soil properties: a review. Sci Total Environ, 2018, 613–614, 944–957. [CrossRef]

- Jamiołkowska, A., Księżniak, A., Gałązka, A., Hetman, B., Kopacki, M., Skwaryło-Bednarz, B. Impact of abiotic factors on development of the community of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the soil: a Review. Int Agrophys, 2018, 32, 133–140. [CrossRef]

- Gavito, M.E., Olsson, P.A. Foraging for resources in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: What is an obligate symbiont searching for and how is it done? In Mycorrhiza, A. Varma (ed.), Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp.73–88. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Goltapeh, E., Rezaee Danesh, Y., Prasad, R., Varma, A. Mycorrhizal fungi: What we know and What should we know? In Mycorrhiza, A. Varma (ed.), Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 3–27. [CrossRef]

- Öpik, M., Saks, Ü., Kennedy, J., Daniell, T. Global diversity patterns of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi–community composition and links with functionality. In Mycorrhiza, A. Varma (ed.), Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2008, pp.89–111. [CrossRef]

- Kytöviita, M-M., Vestberg, M. Soil legacy determines arbuscular mycorrhizal spore bank and plant performance in the low Arctic. Mycorrhiza, 2020, 30, 623–634. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.F., Su, Y.Y., Zhang, Y., Wu, M.Y., Zhang, Z., Pei, K.Q., Sun, L.F., Wan, S.Q., Liang, Y. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spore communities and its relations to plants under increased temperature and precipitation in a natural grassland. Chin Sci Bull, 2013, 58(33), 4109–4119. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Yang, X., Guo, R., Guo, J. Response of AM fungi spore population to elevated temperature and nitrogen addition and their influence on the plant community composition and productivity. Sci Rep, 2015, 6, 24749. [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, J., Aphalo, P.J., Lehto, T. Temperature affected the formation of arbuscular mycorrhizas and ectomycorrhizas in Populus angustifolia seedlings more than a mild drought. Soil Biol Biochem, 2020, 146, 107798. [CrossRef]

| Sampling sites | A | B | C | ||||||

| Fire Severity | Unb* | Mod | High | Unb | Mod | High | Unb | Mod | High |

| pH | 6.05 | 6.71 | 7.15 | 6.85 | 7.31 | 7.18 | 6.76 | 6.8 | 7.63 |

| *S*T | Aa | Ab | Ac | Ba | Bb | Bc | Ba | Bb | Bc |

| OM | 24.38 | 11.04 | 11.02 | 28.72 | 8.95 | 7.46 | 34.76 | 12.95 | 8.51 |

| *T | b | a | a | b | a | a | b | a | a |

| N | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.64 | 0.39 |

| *S*T | Ab | ABa | ABa | Ab | Aa | Aa | Bb | Ba | Ba |

| P available | 40.66 | 21.65 | 55.23 | 24.01 | 47.29 | 30.45 | 54.03 | 44.48 | 39.68 |

| Na | 0.88 | 0.88 | 1.06 | 1.12 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 1.07 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| *T | b | a | a | b | a | a | b | a | a |

| K | 0.96 | 1.37 | 0.94 | 1.71 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 1.69 | 1.21 | 1.68 |

| S*T* | b | a | a | ||||||

| Ca | 16.91 | 7.08 | 17.42 | 38.16 | 18.42 | 14.83 | 43.33 | 20 | 32.5 |

| *S*T | b | a | b | b | a | a | b | a | a |

| Mg | 4.08 | 2.08 | 5.58 | 9.33 | 1.83 | 1.33 | 7.5 | 5.67 | 4.5 |

| *S*T | b | a | a | ||||||

| EC | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| *T | a | ab | b | a | ab | b | a | ab | b |

| C/N | 16.7 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 24.4 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 19.2 | 9.9 | 10.8 |

| *T | b | a | a | b | a | a | b | a | a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).