Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Yttria Partially Stabilized Zirconia (Y-TZP) Dental Ceramics

2.2. Monitoring of the Chemical Stability of the Y-TZP Dental Ceramics

3. Results

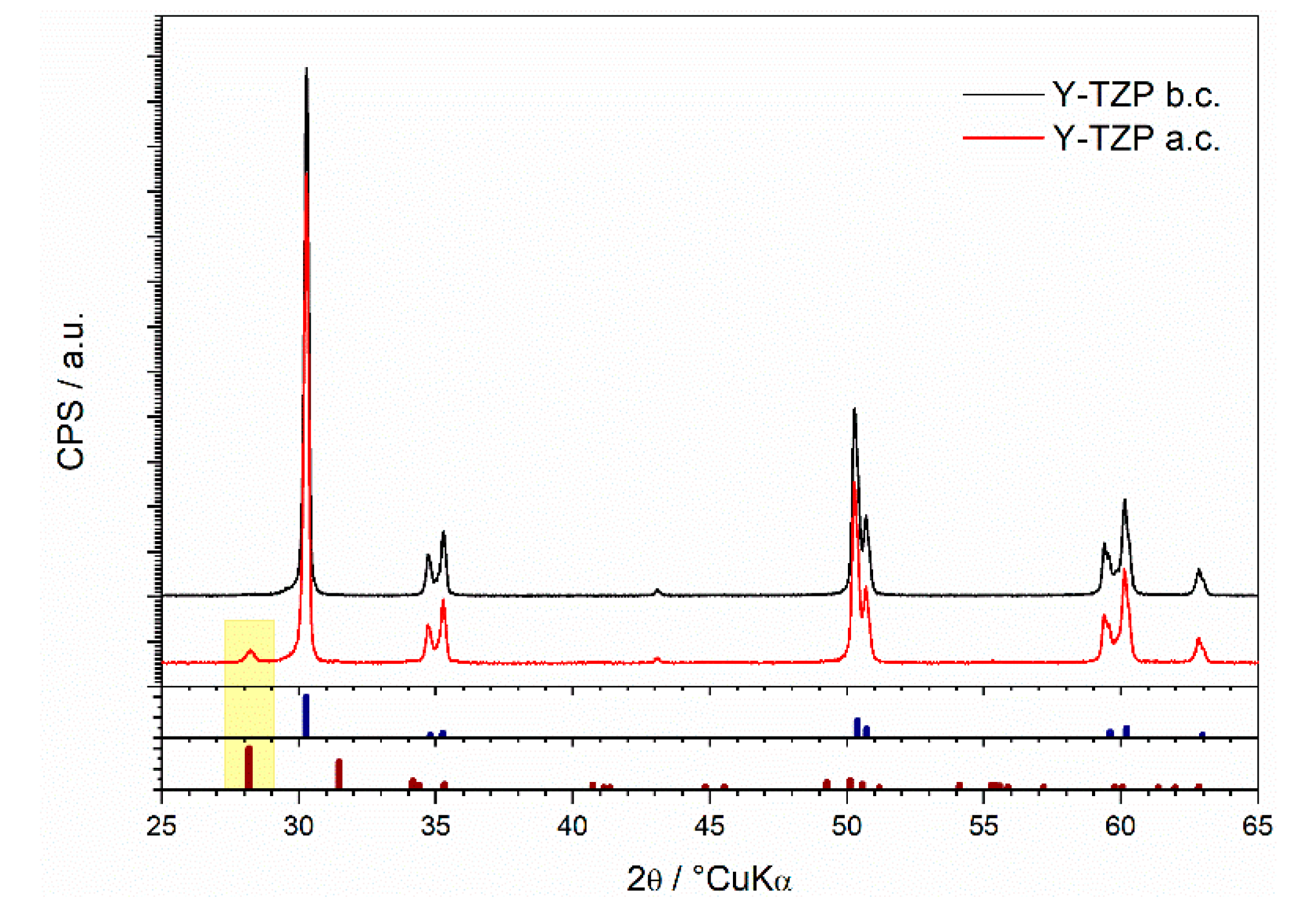

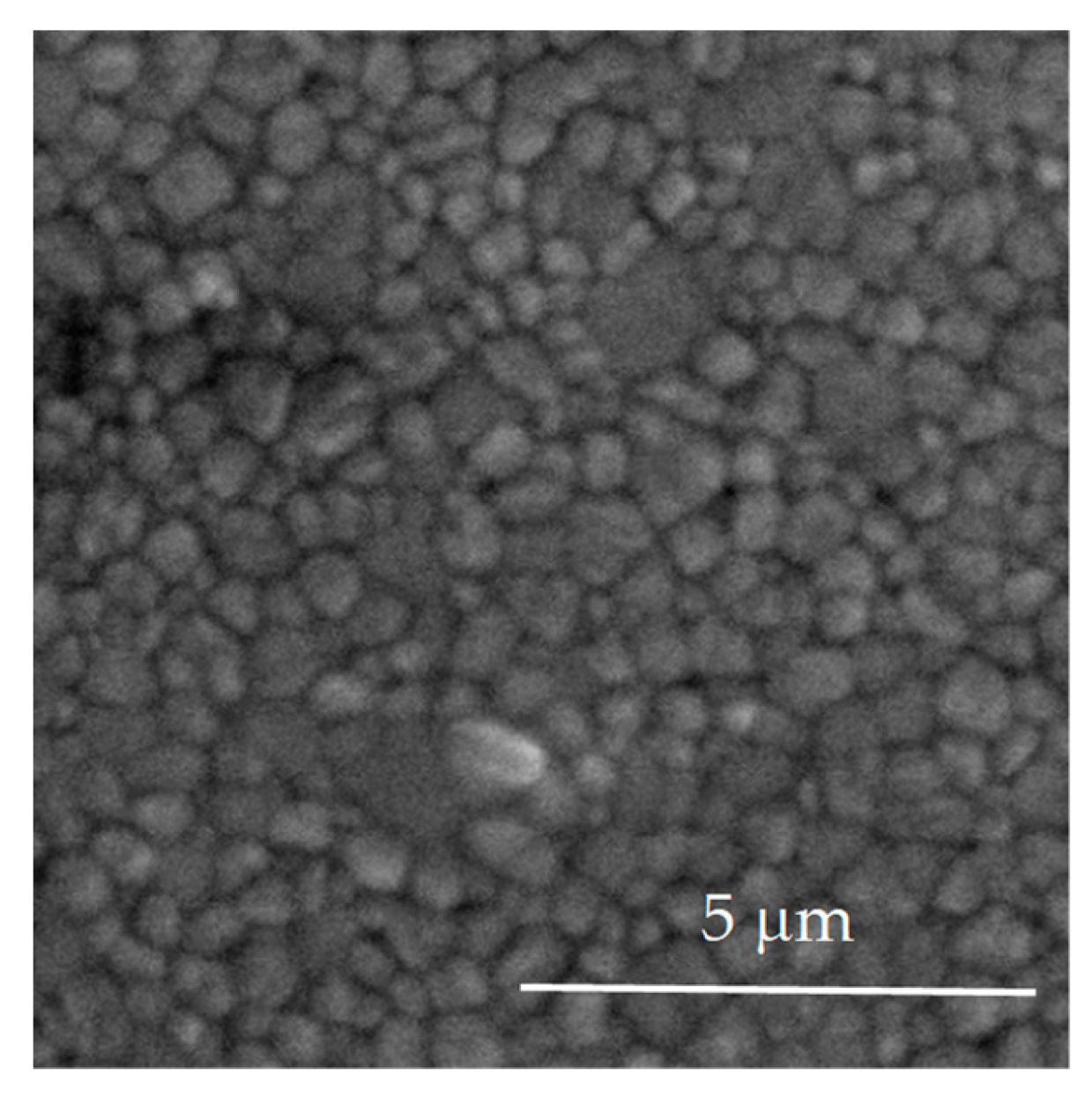

3.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization of Yttria Partially Stabilized Zirconia (Y-TZP) Dental Ceramics

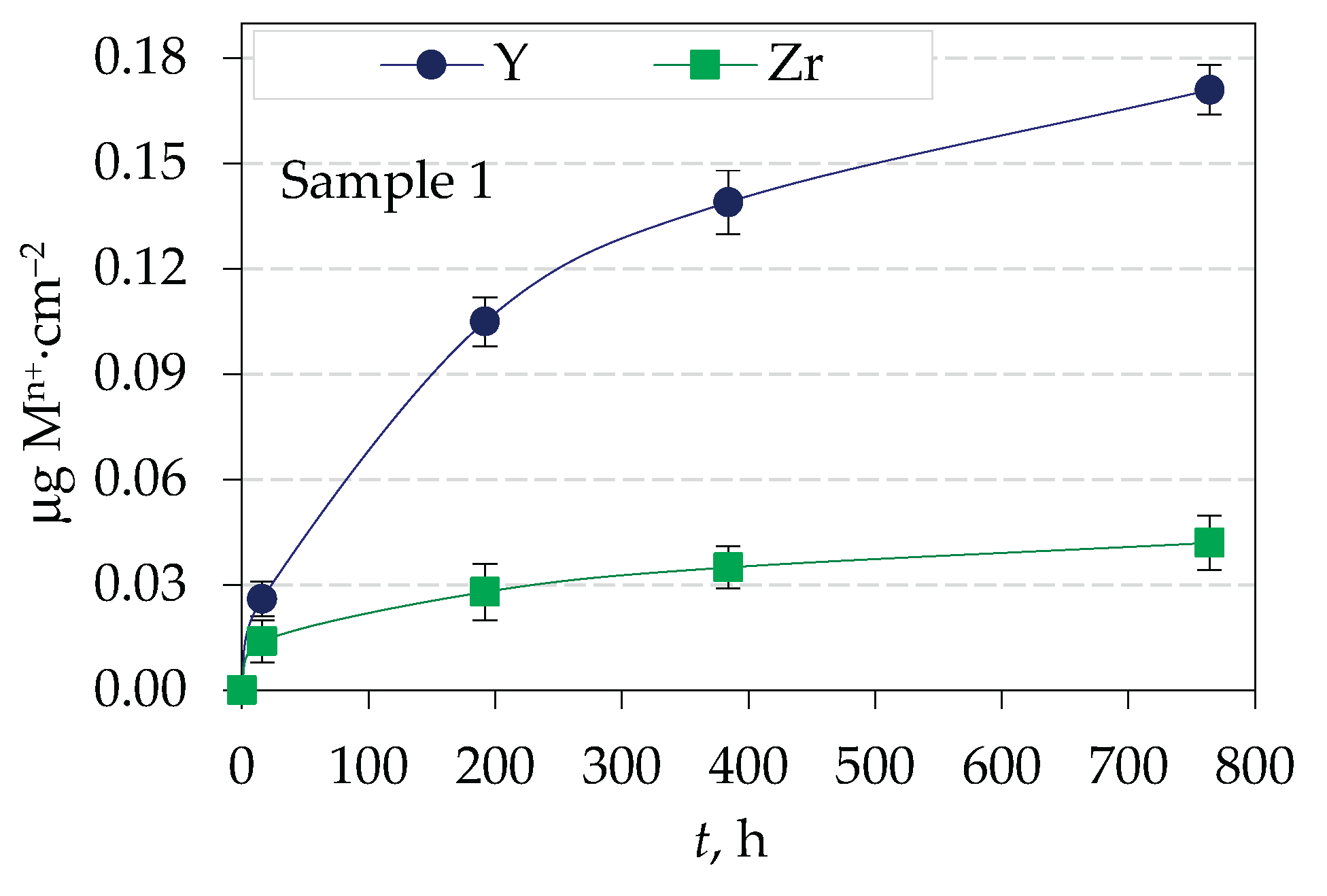

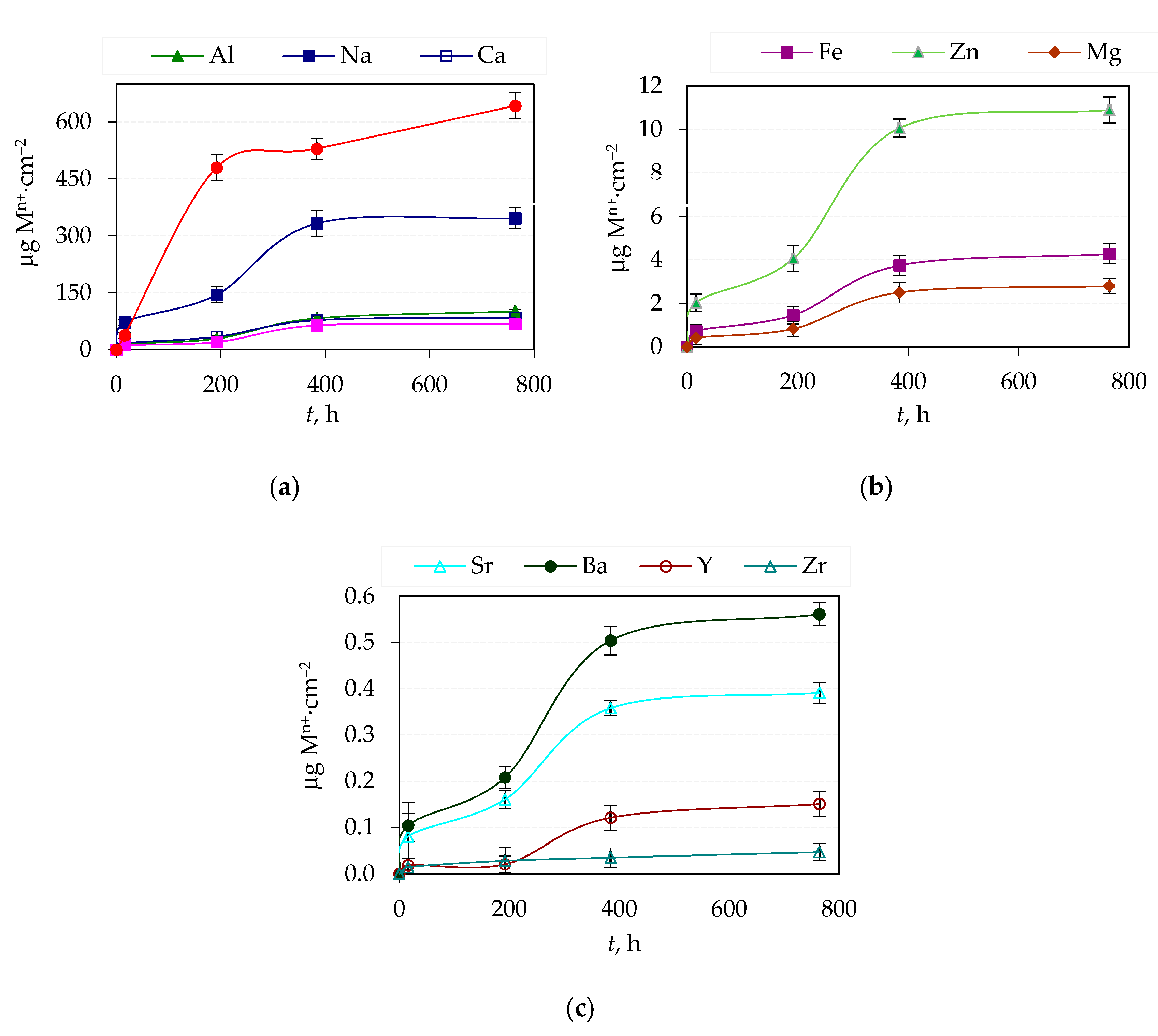

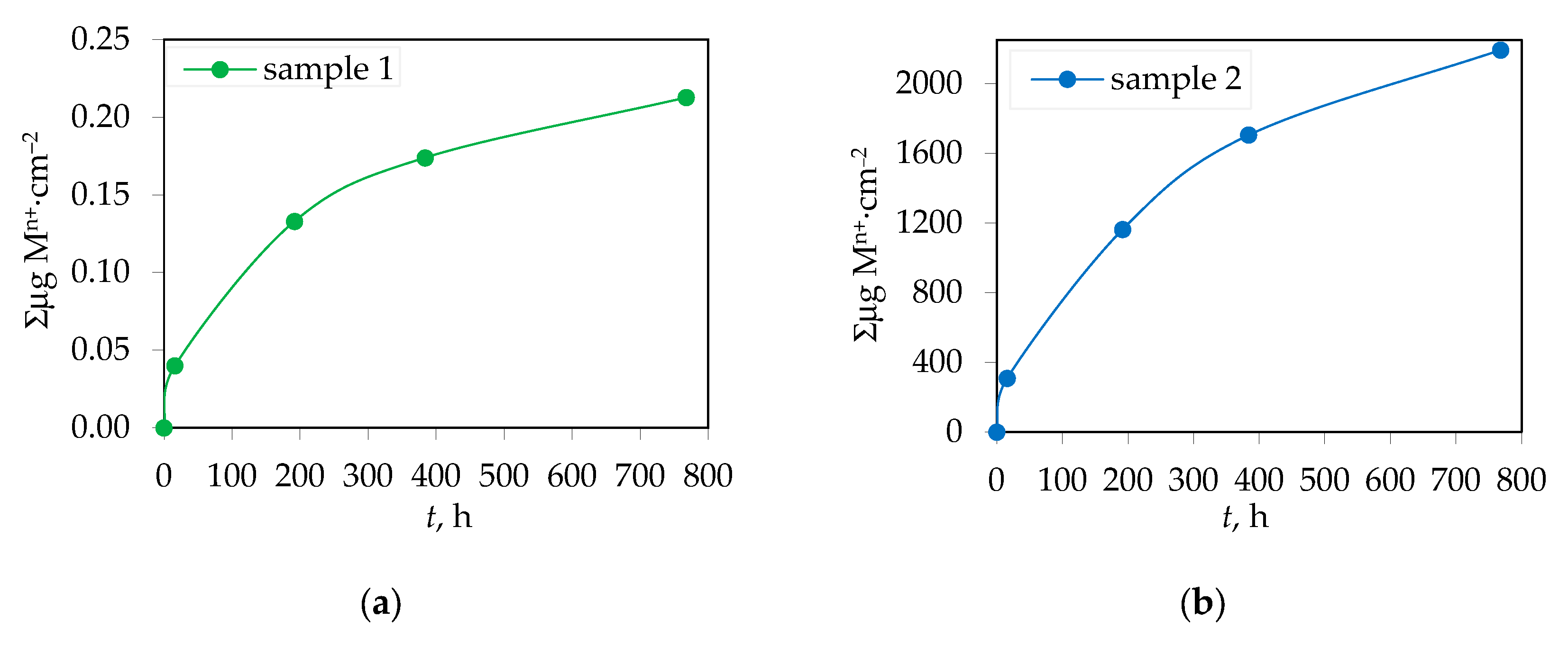

3.2. Amount of Ions Released in Corrosive Solution from Yttria Partially Stabilized Zirconia (Y-TZP) Dental Ceramics

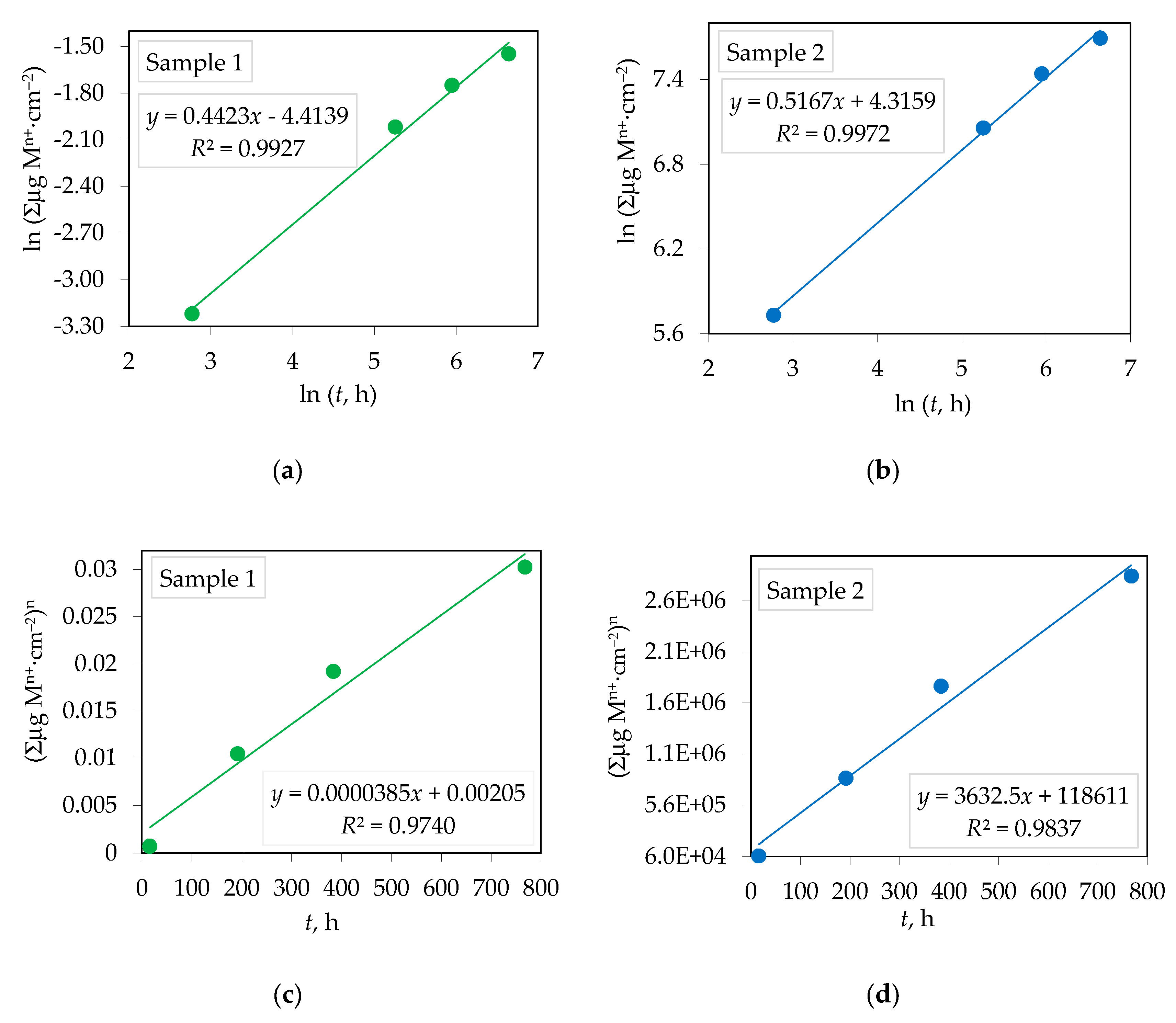

3.3. Corrosion Rate of Yttria Partially Stabilized Zirconia (Y-TZP) Dental Ceramics in CH3COOH

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3Y-TZP | 3 mol% yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal |

| 4Y-TZP | 4 mol% yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ALD | Atomic layer deposition |

| c | Cubic phase |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing |

| Ce-TZP | Ceria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal |

| CNC | Computer numerical control machining |

| FPD | Fixed partial denture |

| HR-ICP-MS | High-resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| LTD | Low-temperature degradation |

| m | Monoclinic phase |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| t | Tetragonal phase |

| VPP | Vat photopolymerization |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| YSZ | Yttria-stabilized zirconia polycrystal |

| Y-TZP | Yttria partially stabilized zirconia polycrystal |

References

- Han, J.; Zhang, F.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J.; Braem, A.; Castagne, S. Laser Surface Texturing of Zirconia-Based Ceramics for Dental Applications: A Review. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 123, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.S.; Mohsen, C.A. Effect of Corrosion On Some Properties of Dental Ceramics. Sys Rev Pharm 2021, 12, 584–588. [Google Scholar]

- Lughi, V.; Sergo, V. Low Temperature Degradation -Aging- of Zirconia: A Critical Review of the Relevant Aspects in Dentistry. Dental Materials 2010, 26, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćorić, D.; Majić Renjo, M.; Žmak, I. Critical Evaluation of Indentation Fracture Toughness Measurements with Vickers Indenter on Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Dental Ceramics: Kritische Bewertung Der Mittels Vickers-Indentierung Ermittelten Bruchzähigkeit von Mit Yttriumoxid Stabilisierten Tetragonalen Zirkonoxid-Dentalkeram. Mat.-wiss. u. Werkstofftech. 2017, 48, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceramic Steel? In Sintering Key Papers; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1990; pp. 253–257. ISBN 978-94-010-6818-5.

- Elshazly, E.S.; El-Hout, S.M.; Ali, M.E.-S. Yttria Tetragonal Zirconia Biomaterials: Kinetic Investigation. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2011, 27, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohé, A.E.; Gamboa, J.J.A.; Pasquevich, D.M. Enhancement of the Martensitic Transformation of Tetragonal Zirconia Powder in the Presence of Iron Oxide. Materials Science and Engineering: A 1999, 273–275, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkamhaeng, K.; Dawson, D.V.; Holloway, J.A.; Denry, I. Effect of Surface Modification on In-Depth Transformations and Flexural Strength of Zirconia Ceramics. Journal of Prosthodontics 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majić Renjo, M.; Ćurković, L.; Štefančić, S.; Ćorić, D. Indentation Size Effect of Y-TZP Dental Ceramics. Dental Materials 2014, 30, e371–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.G.; Lyons, K.M.; Waddell, J.N.; Li, K.C. Effect of Thermocycling on the Mechanical Properties, Inorganic Particle Release and Low Temperature Degradation of Glazed High Translucent Monolithic 3Y-TZP Dental Restorations. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2022, 136, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Yamani, A.; Soualhi, H.; Alaoui, Y.A. The Evolution of Dental Zirconia: Advancements and Applications. CODS - Journal of Dentistry 2025, 16, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toksoy, D.; Önöral, Ö. Optical Behavior of Zirconia Generations. cjms 2024, 9, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Inokoshi, M.; Batuk, M.; Hadermann, J.; Naert, I.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J. Strength, Toughness and Aging Stability of Highly-Translucent Y-TZP Ceramics for Dental Restorations. Dental Materials 2016, 32, e327–e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitwirachot, K.; Rungsiyakull, P.; Holloway, J.A.; Jia-mahasap, W. Wear Behavior of Different Generations of Zirconia: Present Literature. International Journal of Dentistry 2022, 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zhou, J.; Ren, C.; Zhang, F.; Tang, J.; Omran, M.; Chen, G. Sintering Behaviour and Properties of Zirconia Ceramics Prepared by Pressureless Sintering. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 27192–27200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Franco Tabares, S.; Larsson, C.; Papia, E. Laboratory, Clinical-Related Processing and Time-Related Factors’ Effect on Properties of High Translucent Zirconium Dioxide Ceramics Intended for Monolithic Restorations A Systematic Review. Ceramics 2023, 6, 734–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G.; Fabbri, P.; Leoni, E.; Salernitano, E.; Mazzanti, F. New Perspectives on Zirconia Composites as Biomaterials. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Dou, R.; Zhu, F.; Gao, Y. Effects of Dopants with Varying Cationic Radii on the Mechanical Properties and Hydrothermal Aging Stability of Dental 3Y-TZP Ceramics Fabricated via Vat Photopolymerization. Ceramics International 2025, 51, 11857–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefančić, S.; Ćurković, L.; Baršić, G.; Majić-Renjo, M.; Mehulić, K. Investigation of Glazed Y-TZP Dental Ceramics Corrosion by Surface Roughness Measurement. Acta Stomatol Croat 2013, 47, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A.; El-Maghraby, H.F.; Švančárková, A.; Galusková, D.; Reveron, H.; Gremillard, L.; Chevalier, J.; Galusek, D. Corrosion and Low Temperature Degradation of 3Y-TZP Dental Ceramics under Acidic Conditions. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2020, 40, 6114–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, F.R.; Porojan, S.D.; Vasiliu, R.D.; Porojan, L. The Effect of Polishing, Glazing, and Aging on Optical Characteristics of Multi-Layered Dental Zirconia with Different Degrees of Translucency. JFB 2023, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Evaluating Dental Zirconia. Dental Materials 2019, 35, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cailliet, S.; Roumanie, M.; Croutxé-Barghorn, C.; Bernard-Granger, G.; Laucournet, R. Y-TZP, Ce-TZP and as-Synthesized Ce-TZP/Al2O3 Materials in the Development of High Loading Rate Digital Light Processing Formulations. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 3892–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, L.S.; Pilecco, R.O.; Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Kantorski, K.Z.; Valandro, L.F.; Rocha Pereira, G.K. Should Finishing, Polishing or Glazing Be Performed after Grinding YSZ Ceramics? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2023, 138, 105654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Ghulam, O.; Krsoum, M.; Binmahmoud, S.; Taher, H.; Elmalky, W.; Zafar, M.S. Revolution of Current Dental Zirconia: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Li, X.; Tian, F.; Liu, Z.; Hu, D.; Xie, T.; Liu, Q.; Li, J. Fabrication, Microstructure, and Properties of 8 Mol% Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia (8YSZ) Transparent Ceramics. J Adv Ceram 2022, 11, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K. Effect of A Rapid-Cooling Protocol on the Optical and Mechanical Properties of Dental Monolithic Zirconia Containing 3–5 Mol% Y2O3. Materials 2020, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kui, A.; Manziuc, M.; Petruțiu, A.; Buduru, S.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Chisnoiu, A. Translucent Zirconia in Fixed Prosthodontics—An Integrative Overview. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrabeah, G.; Al-Sowygh, A.H.; Almarshedy, S. Use of Ultra-Translucent Monolithic Zirconia as Esthetic Dental Restorative Material: A Narrative Review. Ceramics 2024, 7, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.-K. Advances and Challenges in Zirconia-Based Materials for Dental Applications. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2024, 61, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavriqi, L.; Traini, T. Mechanical Properties of Translucent Zirconia: An In Vitro Study. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerppe, J.; Özcan, M. Zirconia: More and More Translucent. Curr Oral Health Rep 2023, 10, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitero, E.; Reveron, H.; Gremillard, L.; Garnier, V.; Ritzberger, C.; Chevalier, J. Ultra-Fine Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia for Dental Applications: A Step Forward in the Quest towards Strong, Translucent and Aging Resistant Dental Restorations. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2023, 43, 2852–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Osswald, B. Mechanical Properties of an Extremely Tough 1.5 Mol% Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Material. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano Moncayo, A.M.; Peñate, L.; Arregui, M.; Giner-Tarrida, L.; Cedeño, R. State of the Art of Different Zirconia Materials and Their Indications According to Evidence-Based Clinical Performance: A Narrative Review. Dentistry Journal 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, Z.; Shu, Z.; Wu, L. Preparation and Properties of Ternary Rare Earth Co-Stabilized Zirconia Ceramics for Dental Restorations. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovac, M.; Klaser, T.; Bafti, A.; Skoko, Ž.; Pavić, L.; Žic, M. The Effect of Y3+ Addition on Morphology, Structure, and Electrical Properties of Yttria-Stabilized Tetragonal Zirconia Dental Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliev, G.; Vasileva, R.; Kirov, D.; Deliverska, E.; Kirilova, J. Mechanical Resistance of Different Dental Ceramics and Composite, Milled, or Printed Materials: A Laboratory Study. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 11129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turon-Vinas, M.; Anglada, M. Strength and Fracture Toughness of Zirconia Dental Ceramics. Dental Materials 2018, 34, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Ziglioli, N.U.; Marocho, S.M.S.; Satterthwaite, J.; Borba, M. Effect of the CAD/CAM Milling Protocol on the Fracture Behavior of Zirconia Monolithic Crowns. Materials 2024, 17, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, R.; Sindoni, A.; Tribst, J.P.M.; Dal Piva, A.M.D.O.; Lo Giudice, G.; Bellezza, U.; Lo Giudice, G.; Famà, F. Evaluation of Zirconia and High Performance Polymer Abutment Surface Roughness and Stress Concentration for Implant-Supported Fixed Dental Prostheses. Coatings 2022, 12, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohal, R.J.; Riesterer, E.; Vach, K.; Patzelt, S.B.M.; Iveković, A.; Einfalt, L.; Kocjan, A.; Hillebrecht, A.-L. Fracture Resistance of a Bone-Level Two-Piece Zirconia Oral Implant System—The Influence of Artificial Loading and Hydrothermal Aging. JFB 2024, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.-M.; Peng, T.-Y.; Wu, Y.-A.; Hsieh, C.-F.; Chi, M.-C.; Wu, H.-Y.; Lin, Z.-C. Comparison of Optical Properties and Fracture Loads of Multilayer Monolithic Zirconia Crowns with Different Yttria Levels. JFB 2024, 15, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labetić, A.; Klaser, T.; Skoko, Ž.; Jakovac, M.; Žic, M. Flexural Strength and Morphological Study of Different Multilayer Zirconia Dental Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-L. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Dental Crown Prosthesis: A Scoping Review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Verma, A. Artificial Intelligence in Use of ZrO2 Material in Biomedical Science: Review Paper. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišević, A.; Tadin, A. Artificial Intelligence and Modern Technology in Dentistry: Attitudes, Knowledge, Use, and Barriers Among Dentists in Croatia—A Survey-Based Study. Clinics and Practice 2024, 14, 2623–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Spies, B.C.; Willems, E.; Inokoshi, M.; Wesemann, C.; Cokic, S.M.; Hache, B.; Kohal, R.J.; Altmann, B.; Vleugels, J.; et al. 3D Printed Zirconia Dental Implants with Integrated Directional Surface Pores Combine Mechanical Strength with Favorable Osteoblast Response. Acta Biomaterialia 2022, 150, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokola, P.; Ptáček, P.; Bafti, A.; Panžić, I.; Mandić, V.; Blahut, J.; Kalina, M. Comprehensive Study of Stereolithography and Digital Light Processing Printing of Zirconia Photosensitive Suspensions. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1616–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, H. Clinical Effectiveness of 3D-Milled and 3D-Printed Zirconia Prosthesis—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, H.; Inokoshi, M.; Nozaki, K.; Komatsu, K.; Kamijo, S.; Liu, H.; Shimizubata, M.; Minakuchi, S.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vleugels, J.; et al. Additively Manufactured Zirconia for Dental Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelkader, M.; Petrik, S.; Nestler, D.; Fijalkowski, M. Ceramics 3D Printing: A Comprehensive Overview and Applications, with Brief Insights into Industry and Market. Ceramics 2024, 7, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, W.; Lin, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, Z.; Nie, G.; An, D.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, Z.; et al. Sintering Kinetics Involving Densification and Grain Growth of 3D Printed Ce–ZrO2/Al2O3. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2020, 239, 122069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, A.; Fouda, N.; Eraky, M.T. Recent Advances in Design and Preparation of Bioceramic Materials for Manufacturing Dental Crowns by Vat Photopolymerization. Discov Appl Sci 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Qian, C.; Jiao, T.; Xu, C.; Sun, J. Zirconia Specimens Printed by Vat Photopolymerization: Mechanical Properties, Fatigue Properties, and Fractography Analysis. Journal of Prosthodontics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Cui, H.; Wang, W.; Xing, B.; Zhao, Z. High Performance Dental Zirconia Ceramics Fabricated by Vat Photopolymerization Based on Aqueous Suspension. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2024, 44, 116795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Seol, H.-J. Effect of High-Speed Sintering on the Optical Properties, Microstructure, and Phase Distribution of Multilayered Zirconia Stabilized with 5 Mol% Yttria. Materials 2023, 16, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka, K.; Takeuchi, N.; Morita, T.; Pezzotti, G. Evaluation of the Effect of High-Speed Sintering on the Mechanical and Crystallographic Properties of Dental Zirconia Sintered Bodies. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2023, 43, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarthak, K.; Singh, K.; Bhavya, K.; Gali, S. Glazing as a Bonding System for Zirconia Dental Ceramics. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, 89, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Asakura, M.; Koie, S.; Hasegawa, S.; Mieki, A.; Aimu, K.; Kawai, T. In Vitro Study of Zirconia Surface Modification for Dental Implants by Atomic Layer Deposition. IJMS 2023, 24, 10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarov, D.; Kozlova, L.; Rogacheva, E.; Kraeva, L.; Maximov, M. Atomic Layer Deposition of Antibacterial Nanocoatings: A Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binici Aygün, E.; Kaynak Öztürk, E.; Tülü, A.B.; Turhan Bal, B.; Karakoca Nemli, S.; Bankoğlu Güngör, M. Factors Affecting the Color Change of Monolithic Zirconia Ceramics: A Narrative Review. JFB 2025, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incesu, E.; Yanikoglu, N. Evaluation of the Effect of Different Polishing Systems on the Surface Roughness of Dental Ceramics. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2020, 124, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Aarts, J.; Ma, S.; Choi, J. The Influence of Polishing on the Mechanical Properties of Zirconia—A Systematic Review. Oral 2023, 3, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovac, M.; Živko-Babić, J.; Ćurković, L.; Aurer, A. Measurement of Ion Elution from Dental Ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2006, 26, 1695–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.; Gremillard, L. Ceramics for Medical Applications: A Picture for the next 20 Years. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2009, 29, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.-M.; Ho, W.-F.; Hsu, H.-C.; Song, Y.; Wu, S.-C. Evaluation of Feasibility on Dental Zirconia—Accelerated Aging Test by Chemical Immersion Method. Materials 2023, 16, 7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Y2O3 | HfO2 | Al2O3 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Na2O | ZrO2 |

| wt.% | 4.1 | 4.0 | 0.34 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | balance |

| Y-TZP | n | R2 | Kp, µgn⋅cm–2n⋅h–1 | R2 |

| Sample 1 | 2.261±0.004 | 0.9927 | 3.85 × 10–5±4.45 × 10–6 | 0.9740 |

| Sample2 | 1.935±0.015 | 0.9972 | 3632.5±330.7 | 0.9837 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).