1. Introduction

School belonging refers to the perception of being accepted, valued, and included in the school community (Osterman, 2000). This emotional connection plays a fundamental role in the academic, emotional, and social development of adolescents (Goodenow, 1993; OECD, 2021). Students who perceive a strong sense of belonging are more likely to engage in school activities, exhibit pro-social behaviours, and achieve better academic outcomes (Allen et al., 2018; Speranza et al., 2023).

Emerging evidence supports that school belonging is not merely a by-product of academic achievement but a fundamental psychological need, strongly influenced by school engagement, peer and teacher relationships, and individual socio-emotional competencies (Slaten et al., 2016; Allen & Kern, 2017). The Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and the Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) provide frameworks to understand how interpersonal and contextual interactions shape the development of belonging in school-aged youth.

In Portugal, studies have identified vulnerable student groups—such as those from ethnic minorities, low socioeconomic backgrounds, or with special educational needs—as being at heightened risk of social exclusion and reduced belonging (Seabra et al., 2022). Furthermore, school engagement, understood as students’ active emotional, behavioural, and cognitive involvement in school life, has emerged as a key determinant of belonging as well as psychological health (Crespo et al., 2021).

The shift towards digital communication and the increasing role of social media in adolescents’ lives have also reshaped experiences of connection and exclusion. While online platforms offer new forms of engagement, they may also amplify risks such as cyberbullying and social isolation (Rodrigues & Silva, 2021; Twenge et al., 2022).

Given its strong associations with mental health, academic motivation, and youth development, school belonging has gained international attention as a core dimension of adolescent well-being (WHO, 2020; OECD, 2021). Despite its relevance, large-scale data on school belonging in Portuguese schools remain scarce.

2. Conceptual Framework: School Belonging as a Developmental and Contextual Construct

2.1. School Belonging: A Psychological Need and Developmental Asset

School belonging is a complex psychological construct that reflects the degree to which students feel personally accepted, included, valued, and supported within the school environment (Goodenow, 1993; Osterman, 2000). In psychological terms, it encompasses affective, cognitive, and behavioural dimensions of one’s experience within a social context, aligning with fundamental human needs for connection and meaning.

According to Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), the need to belong stems from the universal psychological need for relatedness—feeling connected to others and experiencing mutual care and recognition. This perspective positions school belonging as essential for intrinsic motivation and mental health.

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1980) further suggests that secure relationships within the school—particularly with teachers and peers—function as a secondary attachment system. These bonds provide emotional security, encourage exploration and autonomy, and function as buffers against stress indicators. When these needs are not met, students may experience alienation, withdrawal, or engage in externalizing behaviours.

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) adds a group-based lens, proposing that individuals derive part of their identity from the groups they belong to. A strong sense of school belonging, therefore, contributes not only to personal well-being but to the internalization of school values and collective responsibility (Juvonen, 2006).

In the educational context, school belonging has been associated with increased academic engagement, emotional regulation, prosocial behaviour, and lower levels of depression and anxiety (Allen & Kern, 2017; Arslan, 2021; Speranza et al., 2023). It is a protective factor against school dropout and a key indicator of inclusive and supportive school environments (Slaten et al., 2016; OECD, 2021).

Recent studies have also linked belonging to self-regulatory capacity: students who feel connected to their school environment are more likely to set academic goals, persist in the face of difficulties, and engage in reflective learning strategies (Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Wang & Fredricks, 2014). Thus, school belonging is both a determinant and an outcome of positive youth development.

2.2. Socio-Emotional Skills and Positive Youth Development (PYD)

The development of school belonging is closely tied to students’ socio-emotional competences—the skills that allow them to understand and manage emotions, establish healthy relationships, and make responsible decisions (OECD, 2021). These skills are not only protective against psychological distress but also central to forming meaningful connections within the school context.

Within the framework of Positive Youth Development (PYD), socio-emotional skills are seen as foundational assets that promote thriving and reduce risk behaviours. PYD proposes the “Five Cs”— Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring—as developmental outcomes that foster resilience and community engagement (Lerner et al., 2005). Empirical studies confirm that students who report higher levels of connection and competence also report stronger feelings of belonging and higher school engagement (Geldhof et al., 2014; Tomé et al., 2019).

Educational interventions that integrate social-emotional learning (SEL) into the curriculum have demonstrated positive effects on both academic performance and school connectedness. These interventions help students navigate interpersonal challenges, regulate stress, and build a sense of shared purpose in school (Durlak et al., 2011; Matos & Gonçalves, 2020).

2.3. The Role of School Engagement and Relational Support

School engagement is a multidimensional construct that includes students’ emotional attachment to school, behavioural participation in academic and extracurricular activities, and cognitive investment in learning (Fredricks et al., 2004). It serves as both a facilitator and an indicator of school belonging.

Research consistently shows that students who experience supportive school environments—characterised by fairness, emotional safety, and inclusivity—are more likely to report high school engagement and belonging (Wang & Degol, 2016). These settings foster motivation, identity integration, and a sense of orientation towards the future.

In this context, the quality of teacher-student relationships is critical. Teachers who express empathy, show availability, and provide meaningful feedback promote a relational climate that supports belonging and participation (Roorda et al., 2011). Such relationships act as protective buffers, particularly for students experiencing social or academic difficulties.

Relational support from peers also plays a vital role. Peer acceptance and collaboration increase students’ opportunities to engage in school life meaningfully and reduce the risk of social isolation (Slaten et al., 2016). Inversely, experiences of rejection or social conflict—especially bullying—can severely undermine students’ connection to school.

2.4. Structural Barriers: Inequity, Exclusion, and Vulnerability

Despite the universal need for belonging, students do not experience school engagement and inclusion equally. Structural factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, disability, and linguistic background contribute to disparities in access to supportive school environments (Seabra et al., 2022; Veiga, 2016).

Students from marginalized groups often face implicit biases, lower expectations, and fewer opportunities for meaningful participation. These dynamics lead to cumulative disadvantage and reduced academic self-concept, undermining both school engagement and the sense of belonging (Walton & Cohen, 2007).

Bullying, discrimination, and exclusionary practices further weaken the social fabric of the school, creating psychological harm and alienation. A meta-analysis by Gini et al. (2014) confirmed that victimization is strongly associated with diminished school belonging, especially when institutional responses are perceived as inadequate.

Addressing these inequities requires systemic change—policies that prioritize equity, culturally responsive pedagogies, and the active dismantling of discriminatory norms within school cultures (UNESCO, 2019; OECD, 2021).

2.5. Belonging in a Digital and Hybrid Educational Landscape

The digital transformation of education—accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic—has introduced new dynamics in how students engage with school and each other. While digital platforms can extend learning opportunities and social connectivity, they also risk increasing disconnection, surveillance, and exposure to cyberbullying (Livingstone et al., 2021; Twenge et al., 2022).

Digital belonging is emerging as a distinct but interrelated construct, encompassing students’ sense of inclusion, recognition, and participation in virtual learning environments. When digital tools are integrated with care and relational intention, they can foster community and co-learning. When used rigidly or without emotional scaffolding, they may exacerbate disengagement and isolation.

Schools face the challenge of fostering belonging in both physical and digital spaces—ensuring continuity of care, opportunities for voice and expression, and inclusive digital literacy (Kearney et al., 2021). This requires training for teachers, platform design centred on collaboration, and digital well-being policies that align with educational inclusion goals.

3. Aim of the Study

The main objective of this study is to analyze and characterize the level of feeling of belonging among students in Portuguese schools, identifying potential risk factors and protective factors, to develop clues for action.

3.1. Method

The 2nd National Study of the Psychological Health and Well-being Observatory (Matos et al., 2024) began in October with the aim of monitoring the psychological health and well-being of different groups within the school ecosystem. This included students from preschool to 12th grade, as well as parents/guardians, teachers, school leaders, psychologists, and other professionals. In January 2024, school clusters were randomly selected by NUTS III regions and subsequently contacted by email or telephone. The questionnaires were administered online between 23 January and 9 June 2024, under the coordination of teachers and psychologists appointed by each school or school cluster.

For the present study, a total of 3,083 students from lower and upper secondary education participated (2

nd and 3

rd cycles and secondary education). Of these, 49.5% identified as male and 50.5% as female, with a mean age of 13.64 years (SD = 2.53), ranging from 9 to 20 years old. Regarding school grade distribution: 11.7% were in 5

th grade, 13.6% in 6

th grade, 13.7% in 7

th grade, 12.7% in 8

th grade, 14.3% in 9

th grade, 10.6% in 10

th grade, 12.9% in 11

th grade, and 10.6% in 12

th grade (see

Table 1).

The full description of the instrument can be found in the study report (Matos et al., 2024), and for this in-depth study the following questions were used: gender, grade, HBSC symptoms of psychological distress scale, HBSC who-5 perceived quality of life, SSES scale | socio-emotional skills, including the perception of belonging to school; DASS scale, PYD scale | positive development, and school environment scale.

3.2. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis included descriptive measures to characterize the sample, ANOVAs to investigate differences according to gender and age, and linear regression to identify predictors of the dependent variable. Analyses were performed with SPSS, using a significance level of 5%.

3.3. Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study, including the number of participants (N), means, standard deviations (SD), and maximum and minimum values. The variables include social-emotional skills (SSES), indicators of psychological well-being (HBSC_WHO-5), symptoms of psychological distress (HBSC), levels of stress, symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression (DASS), indicators of positive development (PYD) and perception of the school environment. On average, students reported a level of sense of school belonging corresponding to 2.47 (SD = 0.53) out of a maximum of 4 and a minimum of 1.

There were statistically significant differences between genders in relation to involvement in school fights (χ2 (1) = 132.232; p<0,001), with boys (25.2%) more frequently reporting involvement in school fights compared to girls (9.2%).

In the study of the differences between genders in relation to the level of feeling of belonging to school, statistically significant differences were found (F = 8.790; p = 0.003), with male students tending to present a higher level of feeling of belonging to school (M=2.5; SD = 0.53) compared to female students (M= 2.44; SD = 0.53).

Table 3.

ANOVA | Differences between gender and the sense of belonging to school.

Table 3.

ANOVA | Differences between gender and the sense of belonging to school.

| |

N |

Average |

SD |

F |

p |

| Male |

1429 |

2.5 |

0.53 |

8.790 |

0.003** |

| Female |

1488 |

2.44 |

0.53 |

Regarding the study of differences in the level of senseg of school belonging amongst students according to school grades, illustrated in

Table 4, statistically significant differences were observed (F = 11.170; p < 0.001). In the analysis of multiple comparisons, using the post-hoc test by the Scheffé method, there were significant differences in the feeling of school belonging among 5

th grade students (2.64; SD = 0.56) and 8

th grade students (2.41; SD = 0.53), 9th grade (2.39; SD = 0.50), 10

th grade (2.45; SD = 0.52), 11

th grade (2.41; SD = 0.51) and 12

th grade (2.38; SD = 0.55). Significant differences were also identified between 6

th grade students (2.55; SD = 0.51) and 8

th, 9

th, 11

th and 12

th grade students. Additionally, there were statistically significant differences between 10

th and 12

th grade students. These results suggest that younger students tend to have higher levels of sense of belonging to school compared to older students.

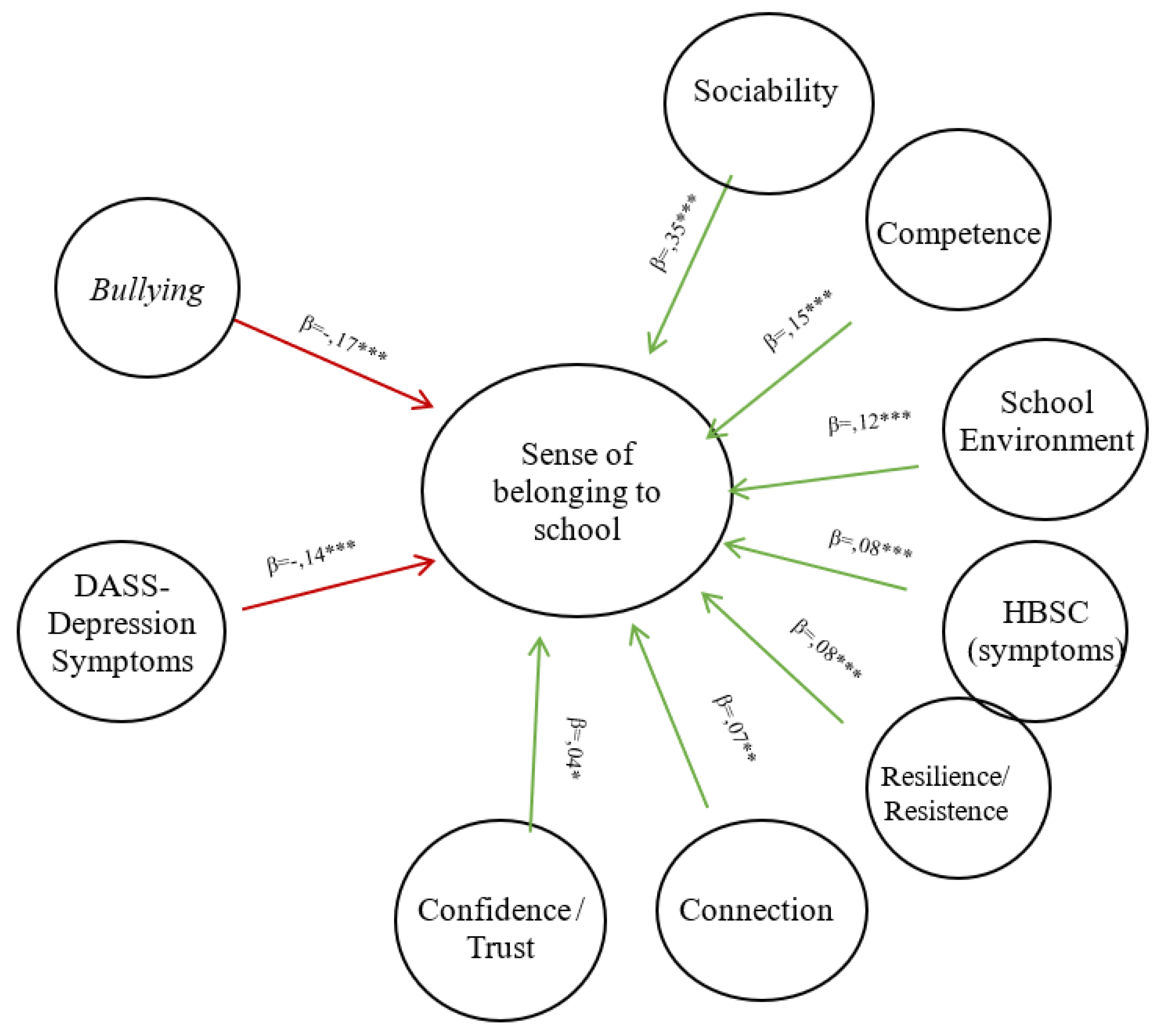

A linear regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of the feeling of school belonging (

Table 5 and

Figure 1). The adjusted model was statistically significant, explaining 58% of the total variance in the feeling of school belonging (R

2 = 0.58; F (26.2208) = 117.492; p < 0.001).

Among the variables evaluated, sociability stands out, presenting a significant positive association with the feeling of belonging to school (β = 0.35; t = 16.64; p < 0.001), indicating that students with greater sociability tend to report a greater sense of belonging to the school environment. Resilience/resistance (β = 0.08; t = 3.48; p < 0.001) and confidence (β = 0.04; t = 2.07; p = 0.04) also demonstrate positive and significant associations.

Within the scope of psychological symptoms, higher levels of symptoms (HBSC) are significantly positively related to the feeling of belonging at school (β = 0.08; t = 3.76; p < 0.001). However, in contrast, symptoms of depression demonstrate a negative association with the feeling of belonging (β = -0.14; t = -5.37; p < 0.001), highlighting the impact of emotional difficulties on school integration.

The dimensions of Positive Youth Development (PYD) are also relevant to the model, especially competence (β = 0.15; t = 6.52; p < 0.001) and connectedness (β = 0.07; t = 3.07; p = 0.002), which are positively associated with the sense of belonging. The school environment emerges as a significant predictor (β = 0.12; t = 6.71; p < 0.001), reinforcing the role of the school context in strengthening integration.

Finally, there is a significant negative association between bullying and sense of belonging (β = -0.17; t = -11.04; p < 0.001), showing that experiences of exclusion or hostility at school harm the sense of belonging. The other predictors included in the model do not present statistically significant associations (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study offers an in-depth analysis of perceived school belonging amongst Portuguese students, highlighting how socio-emotional skills, psychological well-being, and school engagement interact to shape adolescents' connection to their educational environment. The results confirm that school belonging is a multidimensional phenomenon, influenced by both individual competences and systemic relational dynamics.

As in previous literature (Goodenow, 1993; Allen & Kern, 2017), the findings demonstrate developmental differences in perceived belonging. Younger students (particularly those in 5th and 6th grades) reported significantly higher levels of school belonging when compared to older students in secondary education. This pattern suggests that the school transition and increasing academic and social pressure experienced during adolescence may reduce students’ sense of inclusion and connection.

Gender differences also emerged: boys reported higher levels of belonging than girls, consistent with both national(Veiga, 2016) and international findings (Slaten et al., 2016). These differences may reflect gendered experiences of schooling, social support, and emotional expression, and warrant further exploration in gender-sensitive research and intervention designs.

The strongest positive predictor of school belonging was sociability, followed by resilience and confidence—all key dimensions of socio-emotional competence. These results are consistent with international evidence that suggests that emotional regulation, interpersonal skills, and self-efficacy foster social integration and mitigate emotional vulnerability (OECD, 2021; Durlak et al., 2011).

These findings reinforce the importance of integrating Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programmes in schools, as students with stronger socio-emotional skills are more likely to navigate relational challenges and engage meaningfully in academic life (Matos & Gonçalves, 2020; Tomé et al., 2024). Notably, confidence, while a weaker predictor, highlights the internal dimension of belonging—feeling competent and valued within the school setting.

The positive association between school engagement and belonging supports the conceptual model that views emotional, behavioural, and cognitive participation in school life as both outcomes and facilitators of social inclusion (Fredricks et al., 2004; Wang & Fredricks, 2014). Engaged students are more likely to build positive peer relationships, feel respected by teachers, and perceive school as meaningful—conditions that nurture belonging.

Within the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework, competence and connection emerged as significant contributors to school belonging. These dimensions reflect adolescents’ perception of their abilities and their relationships with others, aligning with the “Five Cs” model (Lerner et al., 2005; Geldhof et al., 2014). Their predictive power underscores the developmental relevance of designing school environments that cultivate students’ strengths, instead of just focusing on deficits.

While general psychological symptoms (HBSC) had a small positive association with school belonging, depressive symptoms (DASS) showed a strong negative relationship. This finding aligns with research showing that students with higher depressive symptoms are more likely to feel disconnected, invisible, or unworthy in school contexts (Arslan, 2021). Such students may experience cognitive distortions, social withdrawal, or reduced academic motivation which constitute barriers to relational and institutional belonging.

The most significant negative predictor in the model was bullying, confirming robust evidence that experiences of victimization erode the foundations of school belonging (Gini et al., 2014; Carvalho et al., 2019). Bullying introduces fear, mistrust, and exclusion, directly counteracting the conditions necessary for feeling safe, accepted, and valued.

This reinforces the importance of whole-school approaches to bullying prevention, where fostering empathy, promoting restorative practices, and ensuring relational justice are integral to building inclusive school cultures (UNESCO, 2019; Carvalho et al., 2021).

5. Conclusion and Implications

This study contributes to the growing body of research on adolescent well-being by examining the psychosocial predictors of school belonging in a nationally representative sample of Portuguese students. The findings show that school belonging is not a peripheral construct, but a core developmental and protective factor in young people’s educational trajectories and psychological adjustment.

The results show that younger students and boys report higher levels of school belonging, pointing to the need for targeted interventions during adolescence and with a gender-sensitive approach. More importantly, socio-emotional competences—particularly sociability, resilience, and confidence—emerge as central promotors of school belonging. This underscores the developmental potential of emotional and relational skills for fostering connectedness in school contexts.

Equally significant are the structural and psychological barriers to belonging. Bullying and depressive symptoms were strong negative predictors, revealing how interpersonal harm and internal emotional distress undermine students’ capacity to feel included and valued. In contrast, supportive dimensions of school engagement, along with Positive Youth Development assets like competence and connection, enhance the sense of belonging.

These findings call for an integrated response at multiple levels. In the school setting, fostering school engagement, socio-emotional learning, and relational safety must be prioritized in curriculum, pedagogy, and school culture. At the policy level, investment in inclusive education, mental health promotion, and systemic equity are essential for ensuring that all students, regardless of their background, can experience school as a place of belonging.

5.1. Recommendations

Based on the findings, we propose the following guidelines for action across individual, institutional, and systemic levels:

5.2. Educational Practice and School-Based Interventions

Implement comprehensive SEL programmes that explicitly develop skills such as empathy, resilience, communication, and cooperation.

Foster a culture of school engagement by promoting inclusive, participatory learning environments where students feel valued and heard.

Train teachers in relationship-centred pedagogies and emotional literacy to strengthen student-teacher connections and classroom climate.

Establish anti-bullying frameworks grounded in prevention, early detection, and restorative practices to repair harm and rebuild safety.

5.3. Developmental and Gender-Sensitive Approaches

Target key transition points, such as entering secondary education, with interventions that support identity, peer relationships, and stress management.

Adapt interventions by gender, acknowledging that boys and girls may experience and express school belonging differently, and may benefit from differentiated emotional and relational supports.

5.4. Policy and Systems-Level Recommendations

Prioritize school belonging in education and health policy as a measurable indicator of well-being and inclusion in national strategies.

Ensure systemic equity by addressing structural barriers for vulnerable student populations (e.g., students from low-income backgrounds, ethnic minorities, students with disabilities).

Invest in psychological services in schools, promoting early identification and intervention for emotional difficulties that compromise school engagement and belonging.

Incorporate digital well-being frameworks to strengthen belonging in hybrid or online learning environments, ensuring inclusive digital access and supportive communication.

References

- Allen, K.A.; Kern, M.L. School belonging in adolescents: Theory, research and practice; Springer International Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hattie, J.; Waters, L. What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review 2018, 30, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: Exploring the role of hope and social connectedness. Child Indicators Research 2021, 14, 1921–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design; Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Branquinho, C.; Matos, M.G. Bullying, ciberbullying e problemas de comportamento: o género e a idade importam? Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente 2019, 10, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Branquinho, C.; Gaspar, S.; Reis, M.; Loureiro, V.; Loureiro, N.; Matos, M.G. Ative a sua escola: Violência e Lesões; Instituto Politécnico de Beja, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cosma, A.; Molcho, M.; Picket, t, W. A focus on adolescent peer violence and bullying in Europe, central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children international report from the 2021/2022 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2024; Volume 2, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, C.; Matos, M.G.; Gaspar, T.; Tomé, G. School engagement in Portuguese adolescents: Contributions of individual and contextual variables. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 2021, 34, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, C.; Skinner, E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology 2003, 95, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Bowers, E.P.; Lerner, R.M. Special issue introduction: Thriving in context: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2014, 43, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T.; Hymel, S. Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior 2014, 40, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodenow, C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools 1993, 30, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J. Sense of belonging, social bonds, and school functioning. In Handbook of Educational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Alexander, P.A., Winne, P.H., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2006; pp. 655–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J.V. Positive youth development: A view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2005, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Stoilova, M.; Nandagiri, R. Children’s data and privacy online: Growing up in a digital age. Media and Communication 2021, 9, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.G.; Gonçalves, A. Educação para a saúde e educação emocional em meio escolar: Dos afetos ao desenvolvimento de competências. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia 2020, 54, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 21st-Century Readers: Developing Literacy Skills in a Digital World; OECD Publishing, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, K.F. Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research 2000, 70, 323–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D.L.; Koomen, H.M.Y.; Spilt, J.L.; Oort, F.J. The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research 2011, 81, 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, F.; Veiga, F.; Sá, I. Students’ perceptions of inclusiveness in Portuguese schools: Differences by socioeconomic status and disability. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2022, 37, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaten, C.D.; Ferguson, J.K.; Allen, K.-A.; Brodrick, D.V.; Waters, L. School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist 2016, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, L.; Di Norcia, A.; Larcan, R. School engagement and perceived school belonging as predictors of students’ well-being and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1107037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The social psychology of intergroup relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M.; Haidt, J.; Joiner, T.E.; Campbell, W.K. Declines in adolescent mental health linked to screen time and digital media: A review of evidence and discussion of future directions. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 70, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, G.; Reis, M.; Branquinho, C.; Almeida, A.; Ramiro, L.; Gaspar, T.; Matos, M.G. Chapter 8 - The whole-school ecosystem approach for promoting health and satisfaction with life among adolescents. Osvaldo Santos, Ricardo R. Santos, Ana Virgolino, Ed.; Environmental Health Behavior, Academic Press, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2019: Migration, displacement and education – Building bridges, not walls; UNESCO Publishing, 2019; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265866.

- Veiga, F.H. Assessing student engagement: A review of instruments with a focus on Portuguese research. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 217, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.M.; Cohen, G.L. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2007, 92, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-T.; Degol, J.L. School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review 2016, 28, 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Fredricks, J.A. The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development 2014, 85, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Adolescent well-being: A conceptual framework; World Health Organization, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334419.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).