Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

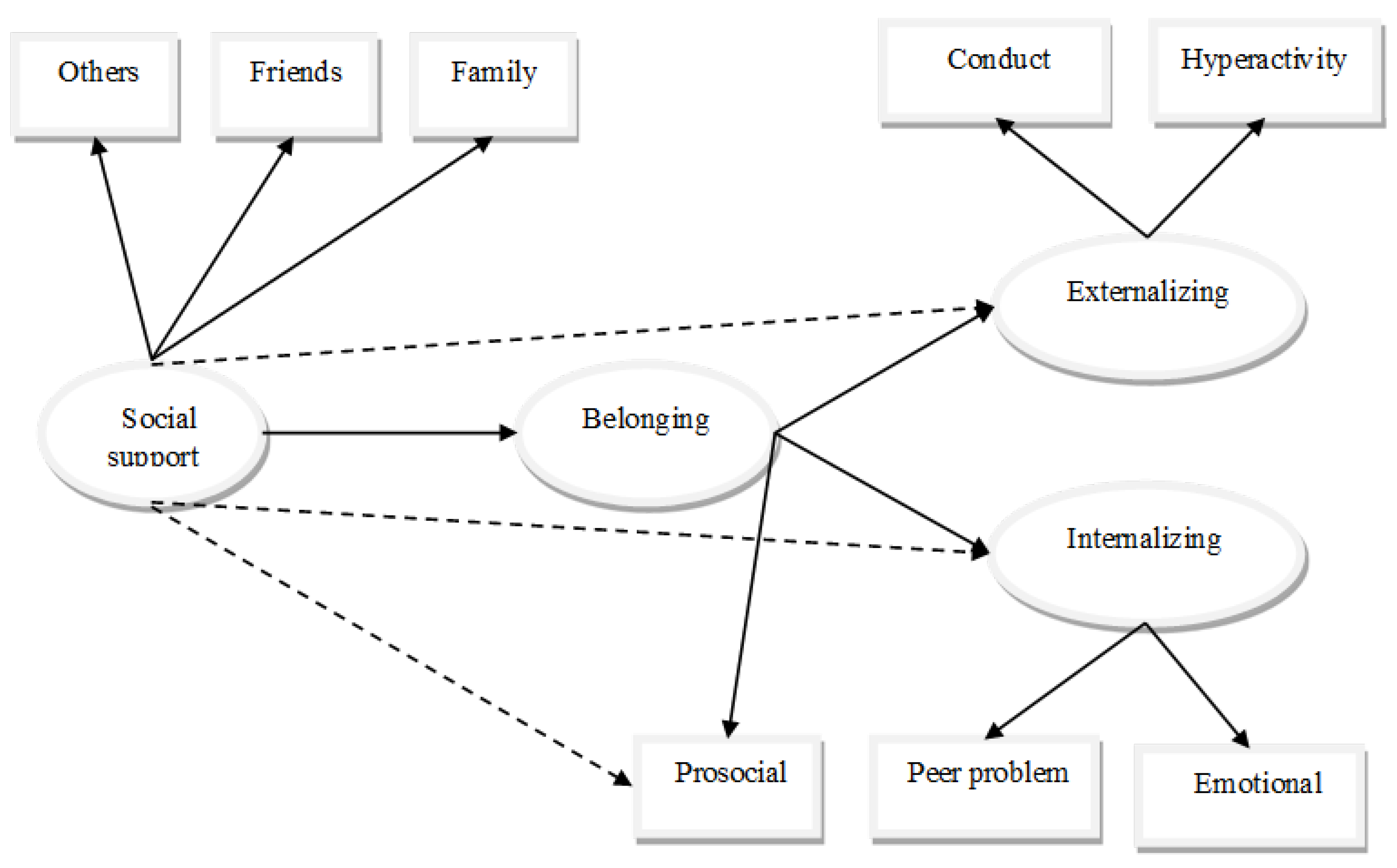

The Mediating Role of School Belonging

The Current Study

Method

Participants and Procedure

Measurement

Analysis

Results

Descriptive Analysis and Correlation Analysis

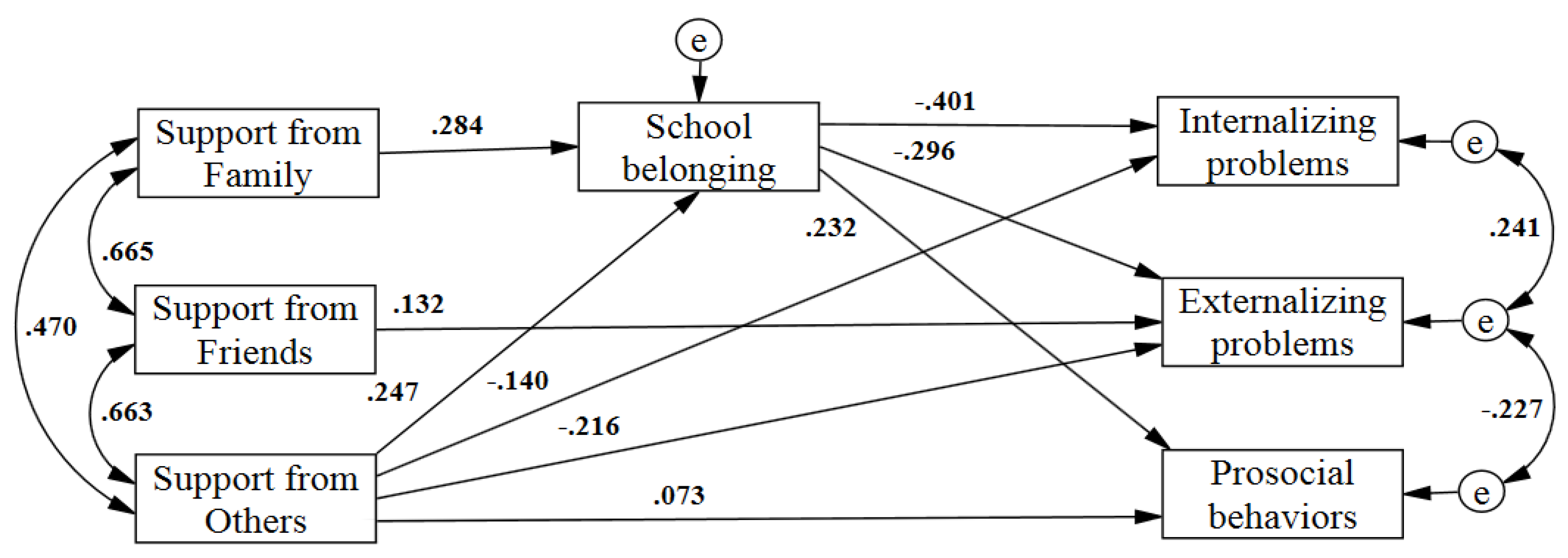

Mediation Model

Discussion

Social Support and Adolescents’ Well-Being

The Mediating Role of School Belonging

Implications

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Statement on Ethics Approval

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

References

- Acoba, E. F. (2024). Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1330720. [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.-A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97-121. [CrossRef]

- Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational psychology review, 30, 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. (2018). Social exclusion, social support and psychological wellbeing at school: A study of mediation and moderation effect. Child indicators research, 11, 897-918. [CrossRef]

- Attar-Schwartz, S., Mishna, F., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2019). The role of classmates’ social support, peer victimization and gender in externalizing and internalizing behaviors among Canadian youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2335-2346. [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu, L., Antonio-Aguirre, I., Izar-de-la-Funte, I., & Fernández-Lasarte, O. (2024). School adjustment in adolescence explained by social support, resilience and positive affect. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Başol, G. (2008). Validity and reliability of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support-revised, with a Turkish sample. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 36(10), 1303-1313. [CrossRef]

- Beam, M. R., Chen, C., & Greenberger, E. (2002). The nature of adolescents’ relationships with their “very important” nonparental adults. American journal of community psychology, 30(2), 305-325. [CrossRef]

- Bernasco, E. L., Nelemans, S. A., van der Graaff, J., & Branje, S. (2021). Friend support and internalizing symptoms in early adolescence during COVID-19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 692-702. [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K., Silva, M. J., Harding, S., & Stansfeld, S. (2017). Bullying, social support, and psychological distress: Findings from RELACHS cohorts of East London’s White British and Bangladeshi adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 317-328. [CrossRef]

- Blum, R. W., Astone, N. M., Decker, M. R., & Mouli, V. C. (2014). A conceptual framework for early adolescence: a platform for research. International journal of adolescent medicine and health, 26(3), 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, K. H., Goodman, R., Rae, D. S., Simpson, G., & Koretz, D. S. (2005). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: US normative data and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(6), 557-564. [CrossRef]

- Bowers, E. P., Johnson, S. K., Buckingham, M. H., Gasca, S., Warren, D. J., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Important non-parental adults and positive youth development across mid-to late-adolescence: The moderating effect of parenting profiles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 897-918. [CrossRef]

- Brendgen, M., & Poulin, F. (2018). Continued bullying victimization from childhood to young adulthood: A longitudinal study of mediating and protective factors. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 46(1), 27-39. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. sage publications.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. Handbook of child psychology, 1. [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G. (2013). The development and correlates of prosocial moral behaviors. In Handbook of moral development (pp. 208-234). Psychology Press.

- Chaudhry, S., Tandon, A., Shinde, S., & Bhattacharya, A. (2024). Student psychological well-being in higher education: The role of internal team environment, institutional, friends and family support and academic engagement. PLoS ONE, 19(1), e0297508. [CrossRef]

- Chemers, M. M., Hu, L.-t., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational psychology, 93(1), 55. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.55.

- Cheung, H. Y. (2004). Comparing Shanghai and Hong Kong students’ psychological sense of school membership. Asia Pacific Education Review, 5, 34-38. [CrossRef]

- Clapham, R., & Brausch, A. (2024). Internalizing and externalizing symptoms moderate the relationship between emotion dysregulation and suicide ideation in adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 55(2), 467-478. [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Rendón, R., López-Angulo, Y., Pérez-Villalobos, M. V., & Díaz-Mujica, A. (2020). Perceived social support and its effects on changes in the affective and eudaimonic well-being of Chilean university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 590513. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American psychologist, 59(8), 676.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98(2), 310. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

- Commisso, M., Geoffroy, M.-C., Temcheff, C., Scardera, S., Vergunst, F., Côté, S. M., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R. E., & Orri, M. (2024). Association of childhood externalizing, internalizing, comorbid problems with criminal convictions by early adulthood. Journal of psychiatric research, 172, 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002). The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools, 39(3), 305-316. 3). [CrossRef]

- Ercan, E. S., Polanczyk, G., Akyol Ardıc, U., Yuce, D., Karacetın, G., Tufan, A. E., Tural, U., Aksu, H., Aktepe, E., & Rodopman Arman, A. (2019). The prevalence of childhood psychopathology in Turkey: a cross-sectional multicenter nationwide study (EPICPAT-T). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 73(2), 132-140. [CrossRef]

- Fakhrou, A. A., Adawi, T. R., Ghareeb, S. A., Elsherbiny, A. M., & AlFalasi, M. M. Role of family in supporting children with mental disorders in Qatar. [CrossRef]

- Fortuin, J., van Geel, M., & Vedder, P. (2015). Peer influences on internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents: A longitudinal social network analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 887-897. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Wang, C., Chai, H., & Xue, R. (2022). Examining the relationship of empathy, social support, and prosocial behavior of adolescents in China: A structural equation modeling approach. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, G., Honkaniemi, H., & Quesnel-Vallee, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284-293. [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79-90. [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The journal of experimental education, 62(1), 60-71. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Güvenir, T., Özbek, A., Baykara, B., Arkar, H., Şentürk, B., & İncekaş, S. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health, 15(2), 65-74.

- Haddadi Barzoki, M. (2024). School belonging and depressive symptoms: the mediating roles of social inclusion and loneliness. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 78(3), 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Haller, E., Lubenko, J., Presti, G., Squatrito, V., Constantinou, M., Nicolaou, C., Papacostas, S., Aydın, G., Chong, Y. Y., & Chien, W. T. (2022). To help or not to help? Prosocial behavior, its association with well-being, and predictors of prosocial behavior during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 775032. [CrossRef]

- Högberg, B., Petersen, S., Strandh, M., & Johansson, K. (2021). Determinants of declining school belonging 2000–2018: The case of Sweden. Social indicators research, 157(2), 783-802. [CrossRef]

- Kågström, A., Pešout, O., Kučera, M., Juríková, L., & Winkler, P. (2023). Development and validation of a universal mental health literacy scale for adolescents (UMHL-A). Psychiatry Research, 320, 115031. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Korol, L., Bayram Özdemir, S., & Stattin, H. (2020). Friend support as a buffer against engagement in problem behaviors among ethnically harassed immigrant adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(7), 885-913. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wisnivesky, J., Gonzalez, A., Feder, A., Pietrzak, R. H., Chanumolu, D., Hu, L., & Kale, M. (2025). The association of perceived social support, resilience, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among coronavirus disease patients in the United States. Journal of affective disorders, 368, 390-397. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Hu, G. (2023). Positive impacts of perceived social support on prosocial behavior: the chain mediating role of moral identity and moral sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1234977. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Li, Q. (2024). How Social Support Affects Resilience in Disadvantaged Students: The Chain-Mediating Roles of School Belonging and Emotional Experience. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 114. [CrossRef]

- Lyell, K. M., Coyle, S., Malecki, C. K., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2020). Parent and peer social support compensation and internalizing problems in adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 83, 25-49. [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V. O., Rigoli, D., Heritage, B., Roberts, L. D., & Piek, J. P. (2016). The relationship between motor skills, perceived social support, and internalizing problems in a community adolescent sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 543. [CrossRef]

- McLean, L., Gaul, D., & Penco, R. (2023). Perceived social support and stress: A study of 1st year students in Ireland. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(4), 2101-2121. [CrossRef]

- Meque, I., Dachew, B. A., Maravilla, J. C., Salom, C., & Alati, R. (2019). Externalizing and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence and the risk of alcohol use disorders in young adulthood: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(10), 965-975. [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y., & Du, B. (2024). Peer factors and prosocial behavior among Chinese adolescents from difficult families. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 815. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K. J., Qualter, P., Humphrey, N., Damsgaard, M. T., & Madsen, K. R. (2023). With a little help from my friends: Profiles of perceived social support and their associations with adolescent mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(11), 3430-3446. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J. D., & Reyes, J. B. (2023). Effect of social support from family on an individual’s loneliness when mediated by one’s sense of belongingness. International Journal of Advances in Social and Economics, 5(1), 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Roksa, J., & Kinsley, P. (2019). The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education, 60, 415-436. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Sacco, R., Camilleri, N., Eberhardt, J., Umla-Runge, K., & Newbury-Birch, D. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in Europe. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J., & Munford, R. (2016). Fostering a sense of belonging at school––five orientations to practice that assist vulnerable youth to create a positive student identity. School Psychology International, 37(2), 155-171. [CrossRef]

- Sari, M. (2012). Sense of School Belonging Among Elementary School Students. Çukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 41(1).

- Schacter, H. L., Lessard, L. M., Kiperman, S., Bakth, F., Ehrhardt, A., & Uganski, J. (2021). Can friendships protect against the health consequences of peer victimization in adolescence? A systematic review. School Mental Health, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Scholte, R. H., Van Lieshout, C. F., & Van Aken, M. A. (2001). Perceived relational support in adolescence: Dimensions, configurations, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 71-94. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of educational research, 99(6), 323-338. [CrossRef]

- Schüürmann, A., & Goagoses, N. (2022). Perceived Social Support and Alcohol Consumption during Adolescence: A Path-Analysis with Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviour Problems. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 27(4), 297-309. [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Martin, M. J., & Wang, Z. (2024). School belonging mediates the longitudinal effects of racial/ethnic identity on academic achievement and emotional well-being among Black and Latinx adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 106, 101330. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, S. D., Dariotis, J. K., Tucker, M. G., & Sonenstein, F. L. (2013). Coping, stress, and social support associations with internalizing and externalizing behavior among urban adolescents and young adults: revelations from a cluster analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(5), 627-633. [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Pastor, A. M., & Sancho, P. (2020). Perceived social support, school adaptation and adolescents’ subjective well-being. Child indicators research, 13(5), 1597-1617. [CrossRef]

- Vaitsiakhovich, N., Landes, S. D., & Monnat, S. M. (2025). The role of perceived social support in subjective wellbeing among working-age US adults with and without limitations in activities of daily living. Disability and Health Journal, 18(1), 101705. [CrossRef]

- Van der Graaff, J., Carlo, G., Crocetti, E., Koot, H. M., & Branje, S. (2018). Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(5), 1086-1099. [CrossRef]

- van Meegen, M., Van der Graaff, J., Carlo, G., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2024). Longitudinal Associations Between Support and Prosocial Behavior Across Adolescence: The Roles of Fathers, Mothers, Siblings, and Friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(5), 1134-1154. [CrossRef]

- Vang, T. M., & Nishina, A. (2022). Fostering School Belonging and Students’ Well-Being Through a Positive School Interethnic Climate in Diverse High Schools. Journal of School Health, 92(4), 387-395. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Madriz, L. F., & Konishi, C. (2021). The relationship between social support and student academic involvement: The mediating role of school belonging. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36(4), 290-303. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Madriz, L. F., Zhang, M., Wang, Z., Long, Y., & Konishi, C. (2023). Social support and traditional bullying perpetration among high school students: The mediating role of school belonging. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson-Lee, A. M., Zhang, Q., Nuno, V. L., & Wilhelm, M. S. (2011). Adolescent emotional distress: The role of family obligations and school connectedness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 221-230. [CrossRef]

- Xin, B., Yao, Z., & Ouyang, M. (2024). Impact of family cohesion and adaptability on students’ sense of school belonging: Chain mediating effects of self-support and selfesteem. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 52(4), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Yu, S., & Lin, W. (2024). Parents’ perceived social support and children’s mental health: the chain mediating role of parental marital quality and parent‒child relationships. Current Psychology, 43(5), 4198-4210. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z. (2024). Cumulative family risk and rural-to-urban migrant adolescent prosocial behavior: The moderating role of school belonging. School Psychology International, 45(6), 616-640. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M., Yıldırım-Kurtuluş, H., Batmaz, H., & Kurtuluş, E. (2023). School belongingness and internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents: Exploring the influence of meaningful school. Child indicators research, 16(5), 2125-2140. [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of personality assessment, 52(1), 30-41. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Perceived support- Family | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Perceived support- Friends | 0.67** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Perceived support- Others | 0.47** | 0.66** | 1 | ||||

| 4. School belonging | 0.40** | 0.37** | 0.38** | 1 | |||

| 5. Internalizing problems | -0.27** | -0.28** | -0.29** | -0.45** | 1 | ||

| 6. Externalizing problems | -0.18** | -0.13** | -0.24** | -0.33** | 0.36** | 1 | |

| 7. Prosocial behaviors | 0.17** | 0.15** | 0.16** | 0.26** | -0.12** | -0.30** | 1 |

| M | 4.66 | 4.16 | 5.01 | 62.06 | 6.27 | 6.94 | 7.82 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.55 | 1.31 | 12.30 | 3.50 | 2.97 | 1.68 |

| Indirect paths | Effect values |

P |

Boot LLCI |

Boot ULCI |

| Perceived support- Family → School belonging → Internalizing problems | -0.114 | < 0.001 | -0.149 | -0.082 |

| Perceived support- Family → School belonging → Externalizing problems | -0.084 | < 0.001 | -0.117 | -0.057 |

| Perceived support- Family → School belonging → Prosocial behaviors | 0.066 | < 0.001 | 0.042 | 0.095 |

| Perceived support- Others → School belonging → Internalizing problems | -0.099 | < 0.001 | -0.104 | -0.070 |

| Perceived support- Others → School belonging → Externalizing problems | -0.073 | < 0.001 | -0.133 | -0.049 |

| Perceived support- Others → School belonging → Prosocial behaviors | 0.057 | < 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.084 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).