1. Introduction

The school environment is a decisive context for the holistic development of children and adolescents, influencing their academic performance, emotional security, and psychosocial well-being. In recent decades, increasing concerns regarding school violence, bullying, and social exclusion have gained international visibility, leading to a growing consensus on the need to ensure physically, emotionally, and socially safe educational environments [

1]. These concerns are not isolated but reflect broader global trends that intersect with children’s rights, educational quality, and public health [

2].

In Portugal, media coverage of school violence may amplify perceptions that schools are unsafe. However, empirical studies suggest that such incidents are often episodic and context-dependent rather than suggestive of systemic insecurity [

3,

4]. A narrow focus on physical security fails to capture the complexity of school safety. Contemporary perspectives advocate for a holistic, multidimensional understanding that includes emotional regulation, inclusive practices, positive peer relations, and mental health support.

Aligned with this view, this study explores the perception of safety among Portuguese adolescents using data from a large national sample. The aim is to identify risk and protective factors that influence students’ sense of safety and to contribute to evidence-informed recommendations aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals [

5] and international educational frameworks [

6].

1.2. Conceptual Framework: School Safety as a Multidimensional Construct

School safety is increasingly conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing physical, emotional, social, and contextual dimensions [

7]. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979), schools are situated as microsystems with profound developmental implications. Within this framework, safety refers not only to protection from physical harm but also to psychological security and social inclusion.

Positive perceptions of safety are consistently associated with better academic engagement, social adaptation, and emotional well-being [

8]. Conversely, perceptions of insecurity—whether due to direct violence, relational aggression, or fear of exclusion—can increase psychological distress, absenteeism, and behavioural problems [

9,

10].

Furthermore, school safety is embedded within the broader concept of school climate, which includes relational dynamics, pedagogical practices, and the institutional environment [

11]. A safe school climate promotes respect, clear behavioural norms, and supportive teacher-student relationships, fostering a sense of belonging and trust [

12].

From a developmental standpoint, adolescence is a key period for examining perceptions of safety. Adolescents are highly sensitive to social acceptance and environmental cues, which shape their identity formation and coping mechanisms [

13]. Understanding how young people perceive safety in their schools is essential for creating contexts that enhance their protective resources and mitigate risk behaviours.

1.3. Dimensions and Determinants of School Safety

According to international guidelines [

6], school safety encompasses five key dimensions: physical safety, mental health and emotional well-being, pedagogical and learning environment, interpersonal relationships, and sense of belonging. These pillars contribute directly to the overall safety and development of students and teachers alike.

Promoting school safety thus requires attention to both the physical and virtual learning environments and to the values, norms, and practices that shape school culture [

14]. Structural aspects such as school policies, teacher practices, and community characteristics also interact with individual and relational dynamics to shape perceptions of safety [

15].

This multidimensionality has direct implications for student outcomes: (1)

Reducing stress and anxiety: Environments perceived as safe reduce exposure to violence, bullying, and exclusion, thereby decreasing stress and anxiety [

16,

17]. (2)

Promoting healthy relationships: Respectful and supportive interactions among peers and adults foster emotional resilience and self-esteem [

18,

19]. (3)

Preventing trauma: Safe environments mitigate the risk of traumatic experiences such as PTSD [

20,

21]. (4)

Fostering positive development: A secure context enables students to explore their potential, build autonomy, and set personal goals. (5)

Enhancing academic performance: Unsafe contexts impair cognitive processing and participation, undermining learning and performance [

22].

1.4. The Interrelationship Between School Safety and Mental Health

The World Health Organization (2021) asserts that “there is no health without mental health”. Numerous studies support a reciprocal relationship between school safety and mental health: safe environments foster positive mental health, and mentally healthy students contribute to a safer, more productive school climate [

18,

19,

20,

21].

This interrelationship is vital for holistic youth development. Schools that promote mental health and emotional security facilitate inclusive and equitable education, consistent with children’s rights and the goals of social justice. These protective contexts are particularly relevant in adolescence, when identity, autonomy, and peer relationships become central.

1.5. Aim of the Study

Building on the conceptual framework outlined above, the main aim of this study is to understand and characterize the perception of safety in Portuguese schools by identifying potential risk and protective factors. The results will inform the development of evidence-based guidelines to promote safer and more inclusive educational environments aligned with national priorities and global frameworks for sustainable development.

2. Materials and Methods

The 2nd National Study of the Psychological Health and Well-being Observatory [

4] began in October with the aim of monitoring the psychological health and well-being of different groups within the school ecosystem. This included students from preschool to 12th grade, as well as parents/guardians, teachers, school leaders, psychologists, and other professionals. In January 2024, school clusters were randomly selected by NUTS III regions and subsequently contacted by email or telephone. The questionnaires were administered online between 23 January and 9 June 2024, under the coordination of teachers and psychologists appointed by each school or school cluster.

For the present study, a total of 3,083 students from lower and upper secondary education participated (2nd and 3rd cycles and secondary education). Of these, 49.5% identified as male and 50.5% as female, with a mean age of 13.64 years (SD = 2.53), ranging from 9 to 20 years old. Regarding school grade distribution: 11.7% were in 5th grade, 13.6% in 6th grade, 13.7% in 7th grade, 12.7% in 8th grade, 14.3% in 9th grade, 10.6% in 10th grade, 12.9% in 11th grade, and 10.6% in 12th grade (see

Table 1).

The full description of the instrument can be found in the study report [

4], and for this in-depth study the following questions were used: gender, education, HBSC symptoms of psychological distress scale, HBSC who-5 perceived quality of life, SSES scale | socio-emotional skills, DASS-21 scale, PYD scale | positive development, and school environment scale, namely the Perception of Safety at School.

2.1. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis included descriptive measures to characterize the sample, Chi-Squares to investigate differences according to gender and age, and linear regression to identify predictors of the dependent variable. The analyses were performed with SPSS, establishing a significance level of 5%.

3. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study, including the number of participants (N), percentages, means, standard deviations (SD), and maximum and minimum values. The variables cover socio-emotional skills (SSES), indicators of psychological well-being (HBSC_WHO-5), symptoms of psychological distress (HBSC), levels of stress, anxiety and depression (DASS-21), indicators of positive development (PYD), perception of the school environment and perception of safety at school.

More than half of the students reported feeling safe at school (61.8%).

There are statistically significant differences between genders and the school safety perception (χ2(2) = 6.027; p<0.05), with female students (63.5%) having a higher level of perception of safety at school compared to male students (60.5%).

Table 3.

Qui square | School Safety Perception by gender.

Table 3.

Qui square | School Safety Perception by gender.

| |

Male |

Female |

χ2

|

p |

| |

N |

% |

N |

% |

| School Safety Perception |

|

|

|

|

6.027 |

<0.05* |

| Perception Insecurity |

161 |

11.4 |

129 |

8.7 |

| No opinion |

397 |

28.1 |

410 |

27.8 |

| Perceived Safety |

856 |

60.5 |

936 |

63.5 |

Considering the differences between the grades regarding the school safety perception, illustrated in

Table 4, statistically significant differences are observed (χ2(14) = 60.000; p<0.001), with the youngest students (5th and 6th grades - 75.5% and 68.2%, respectively) having a higher level of perception of safety at school compared to other grades and the students in the 9th grade (13.7%) having a higher level of perception of insecurity at school compared to the other groups.

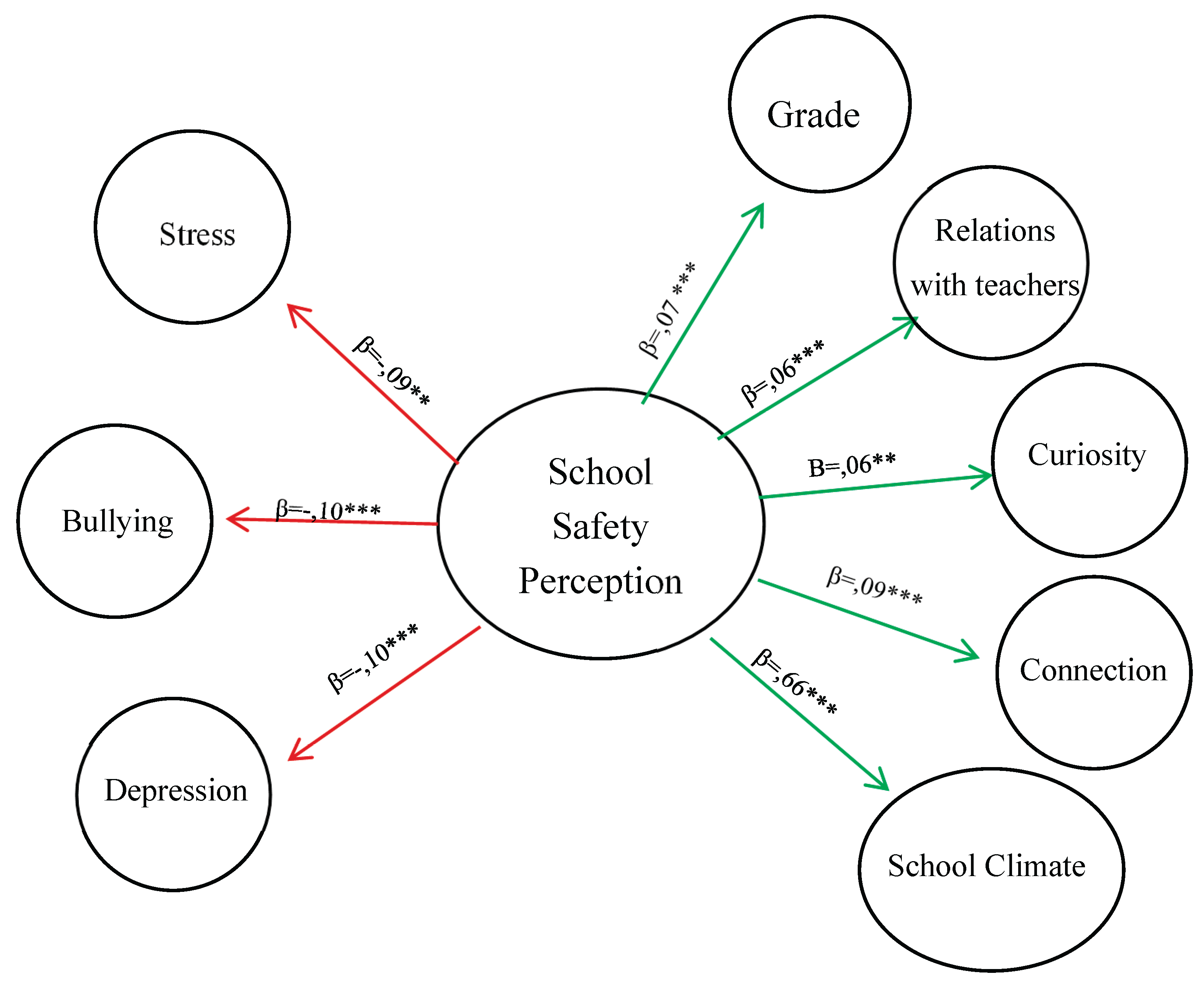

A linear regression analysis was performed to identify the variables associated with the perception of safety at school, using a multivariate model (

Table 5 and

Figure 1). The adjusted model is statistically significant and explains 25.9% of the total variance in the school safety perception (R

2=0.259; F (26.2266) =30.396; p<0.001).

Amongst the variables under analysis, the school environment stands out, presenting a positive association with the perception of safety at school (B= 0.66; t=33.30; p<0.001), suggesting that higher levels of a good school environment are associated with higher levels of school safety perception. The grades demonstrate a significant positive association (B=0.07; t=4.18; p<0.001), indicating that younger students report higher levels of security.

Other variables relevant to the model include, bullying (B=-0.10; t=-5.74; p=0.001), depression (B=-0.10; t=-3.25; p=0.001) and stress (B=-0.09; t=-3.00; p=0.003) in which there is a significant negative association with the perception of safety at school, suggesting that higher levels of these dimensions may be associated with lower levels of school safety.

In the domain of socio-emotional skills assessed by the SSES, curiosity stands out as a significant positive predictor (B=0.06; t=2.80; p=0.005), suggesting that students with greater curiosity have a greater perception of security. Relationships with teachers (B=0.06; t=3.22; p<0.001) also emerge as a positive factor associated with the perception of school safety, and in the context of Positive Youth Development (PYD), there is a significant positive association for connection (B=0.09; t=3.43; p<0.00), suggesting that higher levels of this dimension may be associated with higher levels of school safety.

The other variables analyzed in the model do not present statistically significant associations (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

The present study reinforces the conceptualization of school safety as a multidimensional construct that extends beyond physical protection to include emotional, relational, and contextual dimensions. The findings highlight that over 60% of students reported feeling safe at school, a result that reflects a generally positive perception of the school environment among Portuguese adolescents. However, this also indicates that a significant proportion of students do not share this perception, warranting targeted attention from educators and policymakers.

The multivariate regression analysis confirmed that the quality of the school environment is the strongest predictor of perceived safety. This finding underscores the crucial role that relational and organizational aspects of school life play in shaping students’ subjective sense of security. In particular, positive relationships with teachers were found to significantly enhance students’ perception of safety, aligning with previous literature on the protective function of adult-student relationships [

19]. These results support the argument that school safety is not merely the absence of threats, but rather a reflection of the overall relational climate and support structures within the school.

Significant negative associations were observed between perceived safety and experiences of bullying, depression, and stress, suggesting that psychological distress and exposure to peer victimization considerably undermine students’ sense of security. These findings support previous research [

4,

16] that identifies mental health as both an outcome and a determinant of school safety. The reciprocal relationship between psychological well-being and perceived safety further validates the integration of mental health promotion within school safety strategies.

Moreover, grade level emerged as a significant factor: younger students (especially in the 5th and 6th grades) reported higher perceptions of safety compared to older peers, particularly those in the 9th grade. This pattern may reflect increased exposure to peer conflicts, academic pressure, and developmental challenges in later adolescence (Estévez et al., 2009), all of which can negatively influence students’ emotional security and school adjustment.

In the domain of socio-emotional competencies, curiosity stood out as a significant positive predictor. This suggests that students with a more open and exploratory attitude may feel more secure in their school environment, potentially due to greater engagement, resilience, or adaptive coping strategies. These results highlight the importance of promoting social and emotional learning as a core component of school safety initiatives.

Within the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework, the Connection dimension was positively associated with perceived safety, reinforcing the central role of interpersonal bonds in creating secure educational spaces. Although other PYD dimensions were not statistically significant in the final model, bivariate analyses had shown meaningful associations with Confidence and Competence, indicating the relevance of a strength-based, developmental approach to school safety.

Gender differences were also observed. Interestingly, female students reported slightly higher levels of perceived safety compared to males, although this diverges from some previous findings [

17]. However, females also reported significantly higher scores in the Caring dimension, consistent with research on gender differences in emotional responsiveness and prosocial behaviour [

10]. These nuances suggest the need for gender-sensitive interventions that consider both perceived vulnerability and emotional expression in boys and girls.

Taken together, these findings highlight the protective role of developmental assets and the school climate in fostering a sense of safety and supporting adolescent well-being. The results are consistent with ecological-developmental models [

23,

24] that emphasize the interaction between individual and contextual factors in shaping developmental outcomes.

In alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals [

5], this study reinforces the imperative of creating safe, inclusive, and nurturing school environments to promote mental health, learning, and positive youth development. These efforts must address both the structural and relational dimensions of schooling and should be informed by students’ own perceptions and experiences.

5. Conclusion and Implications

School safety constitutes a foundational pillar for academic achievement and the holistic development of children and adolescents. This study reinforces the growing body of evidence supporting the critical role of perceived school safety in promoting Positive Youth Development (PYD) [

25]. The results revealed that adolescents who perceive their school environments as safe report higher levels of developmental assets across all five dimensions of PYD—most notably in Connection, Confidence, and Competence [

13].

From a theoretical point of view, these findings validate ecological-developmental perspectives, which position the school as a central context for fostering youth potential [

23,

24,

25]. A multidimensional understanding of school safety—encompassing physical, emotional, and relational dimensions—emerges as essential for the activation and consolidation of both internal strengths and external supports that nurture healthy development.

Practically, the study calls for educational stakeholders to reframe the promotion of school safety beyond reactive or punitive approaches. Rather than focusing solely on surveillance or disciplinary actions, interventions should aim to cultivate emotionally safe, inclusive, and relationally supportive school climates. Building meaningful student–teacher relationships, fostering peer cooperation, and encouraging prosocial behaviours are key strategies to reinforce safety perceptions and youth engagement [

11].

The identification of lower perceptions of safety among secondary school students is particularly significant. Educational transitions often heighten vulnerability to emotional and relational insecurity, suggesting that specific attention should be directed to this critical period. Tailored preventive strategies—such a mental health promotion, student voice initiatives, and targeted emotional support—may serve as protective mechanisms to buffer against these challenges.

Furthermore, the findings underscore the broader implications for public policy. Ensuring that all students feel emotionally and physically safe at school is not simply a precondition for learning—it is a key determinant of long-term health, well-being, and social inclusion. As such, school safety must be recognized as both an educational and a public health priority.

To deepen understanding and guide effective action, future research should adopt longitudinal and mixed-method approaches to explore causal mechanisms and contextual variations. Cross-cultural studies may also enhance the generalizability of findings and support the design of evidence-based, locally adapted interventions.

In conclusion, investing in school safety is investing in the present and future flourishing of young people. It is a collective responsibility—shared by educators, families, policymakers, and communities—to ensure that every school is a place where students can learn, grow, and thrive in security and dignity.

6. Recommendations

Based on the study findings, we recommend:

Implementing socio-emotional learning programmes across all levels of education, to foster emotional literacy, empathy, and conflict resolution skills.

Promoting mental health through integrated school-based services, including regular access to psychologists, counsellors, and mental health education.

Developing participatory safety plans that actively involve students, teachers, and families in identifying needs and co-creating solutions.

Investing in teacher training focused on creating inclusive, respectful, and emotionally supportive learning environments.

Monitoring school safety perceptions regularly, with attention to vulnerable groups, in order to assess risks and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

Creating safe, inclusive, and emotionally supportive school environments is not only a moral and legal imperative—but a strategic investment in the development of healthier, more resilient, and equitable societies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- UNESCO. (2017, 2024). Behind the numbers: Ending school violence and bullying. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483.

- WHO – World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. Geneva: WHO.

- Magalhães, A. (2010). Violência e indisciplina em meio escolar: uma leitura sociológica. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

- Matos, M. G., Simões, C., Tomé, G., Camacho, I., & Ferreira, M. (2018, 2024). A saúde dos adolescentes portugueses em tempos de mudança. Relatórios do estudo HBSC. Lisboa: FMH/Universidade de Lisboa.

- United Nations. (2015, 2024). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: UN.

- GADRRRES – Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector. (2023). Comprehensive School Safety Framework 2022–2030.

- Osher, D., Bear, G. G., Sprague, J. R., & Doyle, W. (2018). How can we improve school discipline? Educational Researcher, 49(1), 48–58. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357–385.

- Cornell, D., & Huang, F. (2016). Authoritative school climate and high school student risk behavior: A cross-sectional multi-level analysis of student self-reports. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(11), 2246–2259. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., Way, N., Ling, G. S., Yoshikawa, H., Chen, X., & Hughes, D. (2009). The influence of student perceptions of school climate on socioemotional and academic adjustment. Child Development, 80(5), 1511–1529.

- Cohen, J., & Swearer, S. M. (2009). Safe school climate and positive youth development. Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective, 13-33.

- Konold, T., Cornell, D., Jia, Y., & Malone, M. (2014). School climate, student engagement, and academic achievement: A structural equation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 1185–1198.

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M., Frey, N., & Smith, D. (2015). All learning is social and emotional: Helping students develop essential skills for the classroom and beyond. ASCD.

- Astor, R. A., Guerra, N., & Van Acker, R. (2010). How can we improve school safety research? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 69–78.

- Carvalho, M., Matos, M. G., & Marinucci, D. (2022). School safety and well-being: The influence of perceived insecurity on mental health and academic engagement. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 35(10), 1–12.

- Cosma, A., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Valimaa, R., Boniel-Nissim, M., & Vieno, A. (2023). Trends in adolescent mental well-being in Europe and North America: A repeated cross-sectional study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 25, 100546.

- Fisher, B. W., Gardella, J. H., & Teurbe-Tolon, A. R. (2017). Peer victimization and school climate: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1269–1286. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., Cavell, T. A., & Jackson, T. L. (2015). School climate and school violence: The mediating role of school connectedness. Psychology in the Schools, 42(6), 623–635. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2014). A latent class approach to examining forms of peer victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(3), 839–849. [CrossRef]

- Marinucci, D., Matos, M. G., & Nobre, G. (2022). The impact of school violence on students’ mental health: A review. Psychology, Community & Health, 11(1), 1–15.

- William, D. A., Green, R., & Grant, K. (2018). School connectedness and youth mental health: A systematic review. School Psychology International, 39(6), 545–564.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005). Positive youth development: A view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98-124.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).