Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

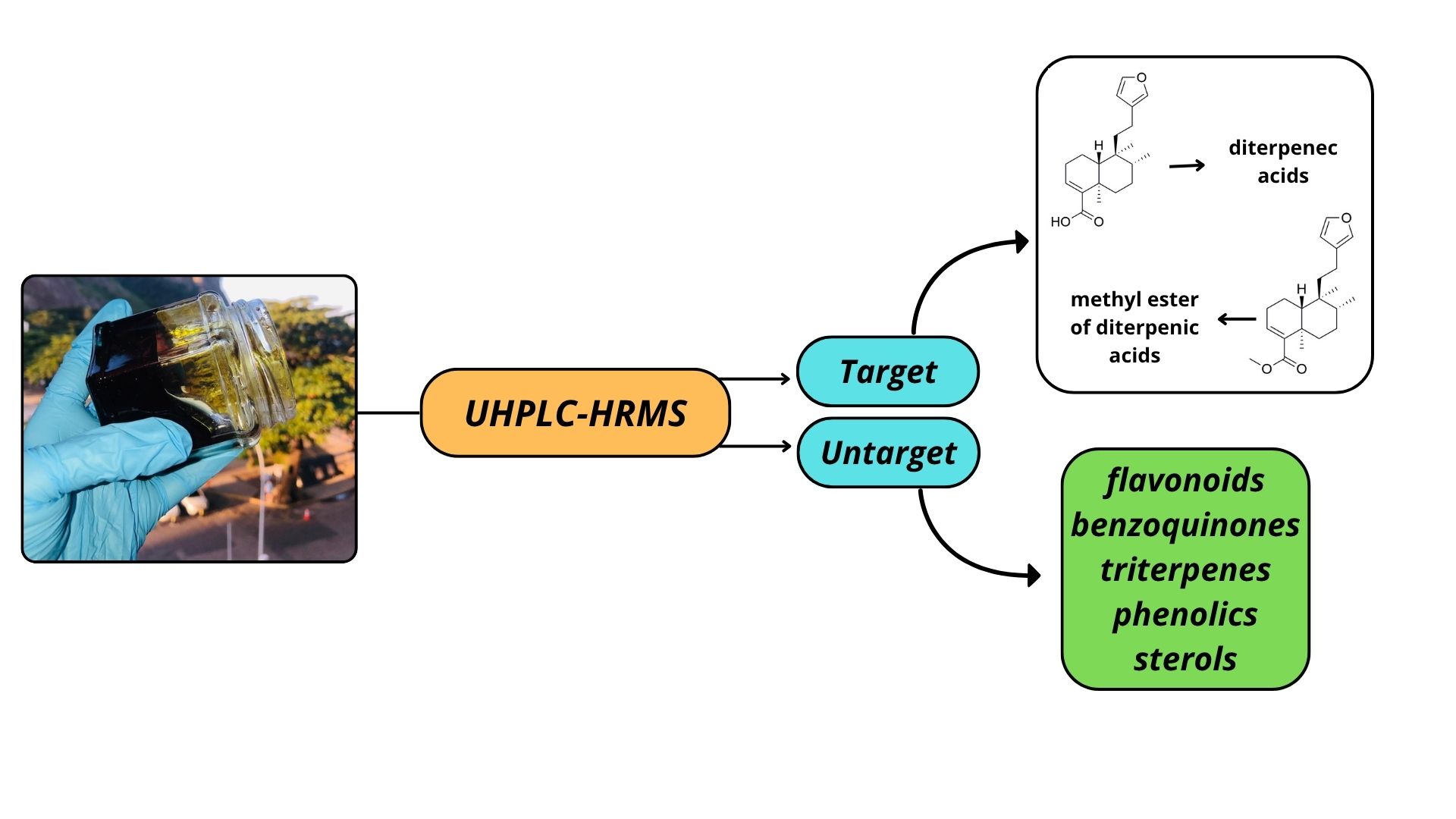

Abstract

Keywords:

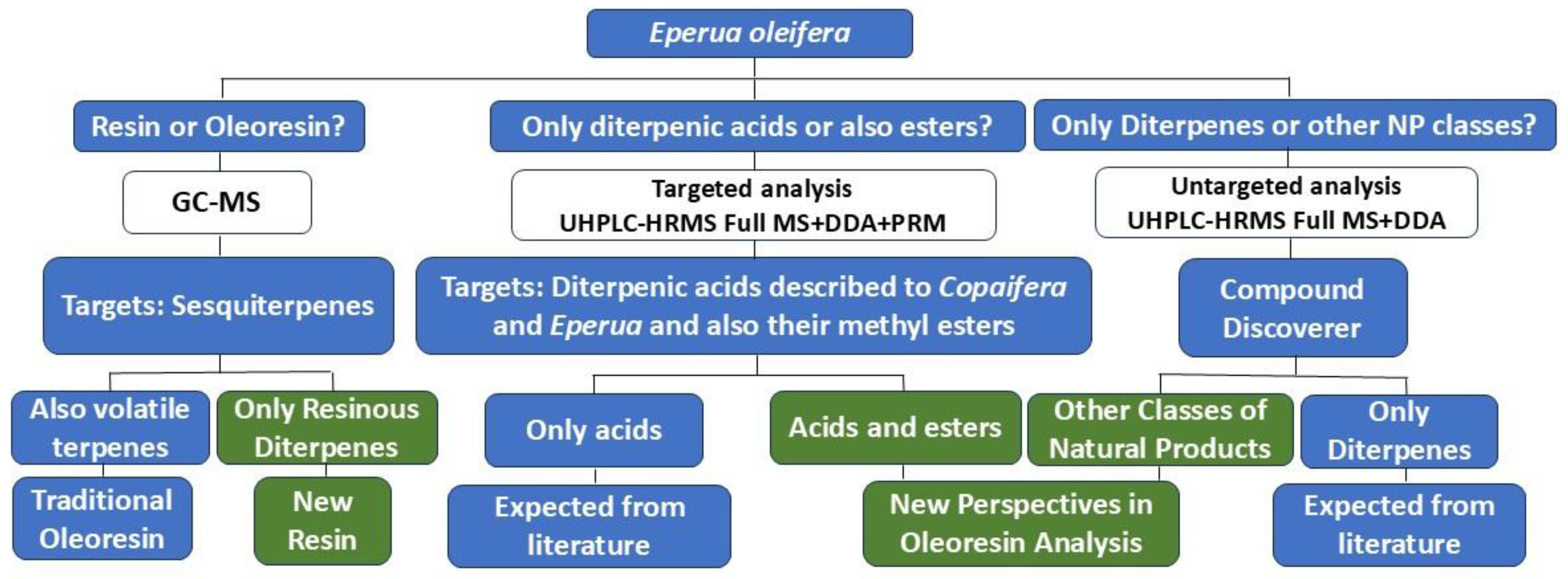

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. GC-MS Analysis and Instrument Conditions

2.3. UHPLC-HRMS Analysis and Instrument Conditions

2.3.1. Evaluation of the Kinetics of Methyl Ester Formation by UHPLC-HRMS

2.3.2. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

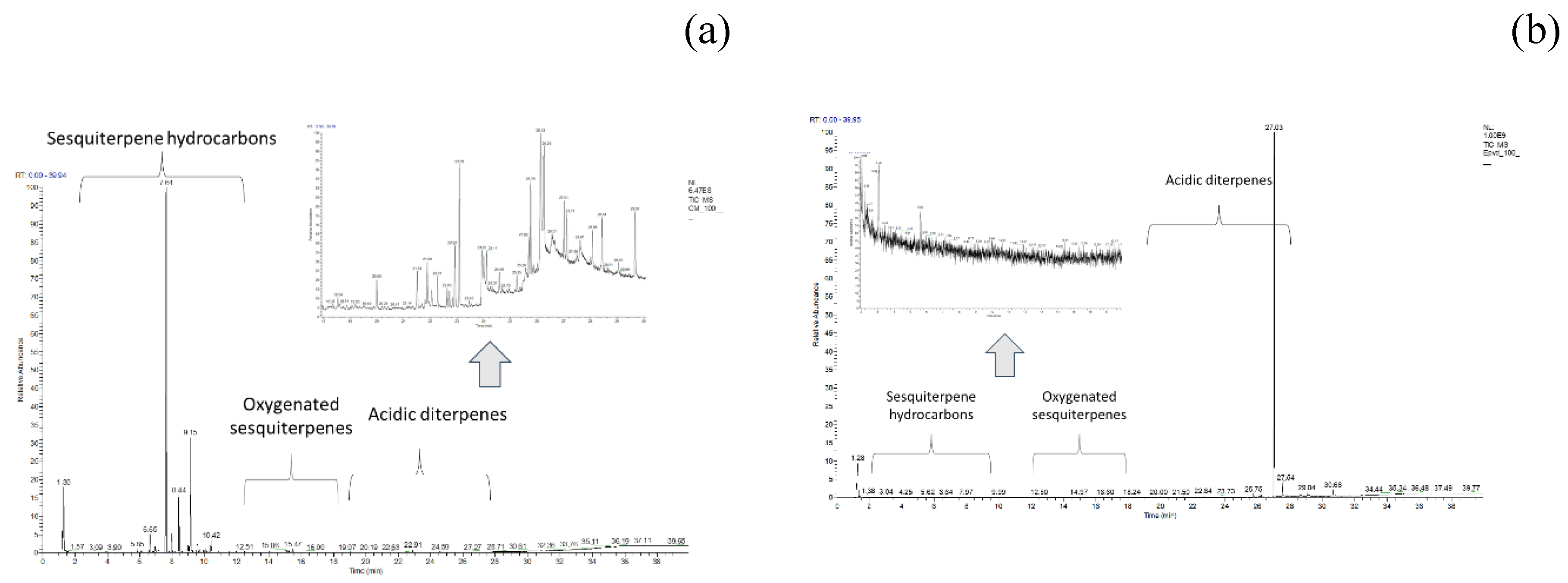

3.1. Characterization of Sesquiterpenes Using Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

3.2. Chemical Characterization of Diterpenes (Targeted) by UHPLC-HRMS

| Compound | Molecular Formula [M] | Retention time (min) | Precursor ion (m/z) [M-H]- | Precursor ion (m/z) [M-H]+ | (N)CE (%) |

Product ion (m/z) [M-H]- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardwickiic acid | C20H28O3 | 12.95 | 315.1966 | 40 | 301.18063 / 257.19086 | |

| Patagonic acid | C20H28O4 | 11.29 | 331.1915 | 40 | 287.20193 / 259.20685 / 243.17505 | |

| Copalic acid | C20H32O2 | 14.00 | 303.2330 | 40 | 285.18607 / 259.20685 / 243.17514 | |

| Agathic acid | C20H30O4 | 11.95 | 333.2071 | 40 | 301.18094 / 291.23303 / 273.22216 | |

| Dihydroagathic (pinifolic) acid | C20H32O4 | 12.22 | 335.2227 | 40 | 301.18109 / 291.23306 / 273.22263 | |

| Eperuic acid | C20H34O2 | 14.06 | 305.2486 | 40 | 287.23767 | |

| Kovalenic acid | C20H32O2 | 14.02 | 303.2329 | 40 | 285.18613 / 243.17538 / 84.02048 | |

| Clerod-3-en-15,18-dioic acid | C20H32O4 | 11.49 | 335.2227 | 40 | 285.18622 / 259.17053 / 245.19104 | |

| 14,15,16-trinor-hardwikiic acid** | C17H26O4 | 10.90/14.43 | 293.1758 | 40 | 96.95888 | |

| 2-oxokolavenic acid | C20H30O3 | 11.84 | 317.2122 | 40 | 301.18112 / 273.22256 / 257.19113 | |

| Methyl hardwickiate | C21H30O3 | 13.90 | 329.2122 | 40 | 301.18015 / 285.18555 / 257.19052 | |

| Methyl copalate | C21H34O2 | 14.90 | 317.2486 | 40 | 301.18112 / 285.18622 / 257.19128 | |

| Methyl 3β-hydroxy copalate | C21H34O3 | 12.81 | 319.2278 | 40 | 301.18073 / 273.22269 / 257.19122 | |

| Methyl 3β-acetoxy copalate | C23H36O4 | 13.88 | 375.2541 | 40 | 317.21210 / 301.18039 / 287.16553 | |

| Methyl patagonate | C21H32O4 | 13.89 | 345.2071 | 40 | 315.19662 / 301.21735 / 243.17531 | |

| Methyl agathate | C21H32O4 | 12.29 | 347.2227 | 40 | ||

| Methyl eperuate | C21H36O2 | 14.95 | 319.2642 | 40 | ||

| Cativic acid* | C20H34O2 | 14.10 | 305.2486 | 40 | ||

| 8,17-dihydroxy-13-labden-16,15-olid-19-oate* | C21H32O6 | 12.21 | 439.2340 [M-H-60]- |

|||

| Effusanin A* | C20H28O5 | 10.84 | 347.1865 | |||

| 18-hydroxy-clerod-3-en-15-oic acid* | C20H34O3 | 13.13 | 321.2437 | |||

| craterellin A* | C22H34O4 | 13.16 | 380.2792 [M+NH4]+ |

|||

| 14-Deoxy-11,12-didehydroandrographolide* | C20H28O4 | 11.94 | 315.1953 [M+H]-18 |

|||

| 12-hydroxy-7-carboxy- abiet-8(13)-en-18-oic acid* |

C20H30O4 | 12.53 | 335.2216 |

|||

| Aphidicolin* | C20H34O4 | 12.08 | 339.2529 |

|||

| 7-keto, 12-hydroxy, abiet-8-14-en-18-oic acid | C20H30O4 | 12.71 | 333.2071 | |||

| (-)-7β-hydroxycleroda-8(17),13E-diene-15-oic acid* | C20H32O3 | 13.47 | 319.2278 | |||

| 16-oxo-13,14H-hardwikiic acid* | C20H28O4 | 11.26 | 331.1914 | |||

| nor-hardwikiic acid* | C17H26O4 | 12.16 | 293.1758 | |||

| 7-oxo-labda-8-ene-15-oic acid* | C20H30O3 | 11.86 | 317.2122 | |||

| (-)-cleroda-7,13E-diene-15-oic acid* | C20H32O2 | 14.62 | 303.2329 | |||

| 6β,7β-Dihydroxykaurenoic acid* | C20H30O4 | 11.48 | 333.2071 | |||

| 8-Hydroxyoctadeca-9,12-dienoic acid* | C18H32O3 | 13.86 | 295.2278 | |||

| Ent-16β,17-dihydroxy-19-kaurenoic acid* | C20H32O4 | 13.05 | 335.2227 |

3.2.1. Evaluation of the Kinetics of Diterpenoate Methyl Ester Formation

3.2.1.1. Oleoresin Dissolved in Methanol Containing 0.1% Formic Acid

3.2.1.2. Oleoresin Dissolved in Acetonitrile

3.3. Other Substances Described in E. oleifera Resin, by UHPLC-HRMS Approach

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Do Brasil, F. Jardim Botânico Do Rio de Janeiro 2020.

- Gomes, F.T.A.; de Araújo Boleti, A.P.; Leandro, L.M.; Squinello, D.; Aranha, E.S.P.; Vasconcelos, M.C.; Cos, P.; Veiga-Junior, V.F.; Lima, E.S. Biological Activities and Cytotoxicity of Eperua Oleifera Ducke Oil-Resin. Pharmacogn Mag 2017, 13, 542. [Google Scholar]

- Leandro, L.M.; Veiga-Junior, V.F. O Gênero Eperua Aublet: Uma Revisão. Sci Amazonia 2012, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leandro, L.M.; da VEIGA-JUNIOR, V.F.; Sales, A.P.B.; do O Pessoa, C. Composição Química e Atividade Citotóxica Dos Óleos Essenciais Das Folhas e Talos de Eperua Duckeana Cowan. Bol Latinoam Caribe Plantas Med Aromat 2015, 14, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, R. ; Finotti, Padilha, M.C.; R.; Pereira, H.M.G.; Magalhães, A; Hallwass, F; Veiga-Junior, V.F. Eperua oleifera Ducke (Fabaceae) oilresin chemical composition and the isolation of a natural diterpenic acid methyl ester. Chem Biodivers, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, J.P.B.; Brancalion, A.P.S.; Junior, M.G.; Bastos, J.K. A Validated Chromatographic Method for the Determination of Flavonoids in Copaifera Langsdorffii by HPLC. Nat Prod Commun 2012, 7, 1934578X1200700110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier Junior, F.H.; Gueutin, C.; do Vale Morais, A.R.; do Nascimento Alencar, E.; do Egito, E.S.T.; Vauthier, C. HPLC Method for the Dosage of Paclitaxel in Copaiba Oil: Development, Validation, Application to the Determination of the Solubility and Partition Coefficients. Chromatographia 2016, 79, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.B.; Moreira, M.R.; Borges, C.H.G.; Simão, M.R.; Bastos, J.K.; de Sousa, J.P.B.; Ambrosio, S.R.; Veneziani, R.C.S. Development and Validation of a Rapid RP-HPLC Method for Analysis of (−)-copalic Acid in Copaíba Oleoresin. Biomedical Chromatography 2013, 27, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sulaiti, H.; Almaliti, J.; Naman, C.B.; Al Thani, A.A.; Yassine, H.M. Metabolomics Approaches for the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Better Disease Management of Viral Infections. Metabolites 2023, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Lu, H.; Lee, Y.H. Challenges and Emergent Solutions for LC-MS/MS Based Untargeted Metabolomics in Diseases. Mass Spectrom Rev 2018, 37, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couttas, T.A.; Jieu, B.; Rohleder, C.; Leweke, F.M. Current State of Fluid Lipid Biomarkers for Personalized Diagnostics and Therapeutics in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders and Related Psychoses: A Narrative Review. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 885904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazofsky, A.; Brinker, A.; Rivera-Núñez, Z.; Buckley, B. A Comparison of Four Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Platforms for the Analysis of Zeranols in Urine. Anal Bioanal Chem 2023, 415, 4885–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Chu, S.; Tan, S.; Yin, X.; Jiang, Y.; Dai, X.; Gong, X.; Fang, X.; Tian, D. Towards Higher Sensitivity of Mass Spectrometry: A Perspective from the Mass Analyzers. Front Chem 2021, 9, 813359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaženović, I.; Kind, T.; Ji, J.; Fiehn, O. Software Tools and Approaches for Compound Identification of LC-MS/MS Data in Metabolomics. Metabolites 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbels, T.M.D.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Chatelaine, H.; Broeckling, C.; Zamboni, N.; Hassoun, S.; Mathé, E.A. Recent Advances in Mass Spectrometry-Based Computational Metabolomics. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2023, 74, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontou, E.E.; Walter, A.; Alka, O.; Pfeuffer, J.; Sachsenberg, T.; Mohite, O.S.; Nuhamunada, M.; Kohlbacher, O.; Weber, T. UmetaFlow: An Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow for High-Throughput Data Processing and Analysis. J Cheminform 2023, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, B.B. New Software Tools, Databases, and Resources in Metabolomics: Updates from 2020. Metabolomics 2021, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.L.; Patti, G.J. A Protocol for Untargeted Metabolomic Analysis: From Sample Preparation to Data Processing. In Mitochondrial Medicine: Volume 2: Assessing Mitochondria; Springer, 2021; pp. 357–382.

- Rivera-Pérez, A.; Garrido Frenich, A. Comparison of Data Processing Strategies Using Commercial vs. Open-Source Software in GC-Orbitrap-HRMS Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis for Food Authentication: Thyme Geographical Differentiation and Marker Identification as a Case Study. Anal Bioanal Chem 2024, 416, 4039–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzadi, I.; Nadeem, R.; Hanif, M.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Jilani, M.I.; Nisar, S. Chemistry and Biosynthesis Pathways of Plant Oleoresins: Important Drug Sources. Int J Chem Biochem Sci 2017, 12, 18–52. [Google Scholar]

- Patitucci, M.L.; Veiga Jr, V.F.; Pinto, A.C.; Zoghbi, M. das G.B.; Silva, J.R.A. Utilização de Cromatografia Gasosa de Alta Resolução Na Detecção de Classe de Terpenos Em Extratos Brutos Vegetais. Quim Nova 1995, 18, 262–265. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Antonio, A.; Oliveira, D.S.; Dos Santos, G.R.C.; Pereira, H.M.G.; Wiedemann, L.S.M.; da Veiga-Junior, V.F. UHPLC-HRMS/MS on Untargeted Metabolomics: A Case Study with Copaifera (Fabaceae). RSC Adv 2021, 11, 25096–25103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, R.B.; Harrata, A.K. Solvent Effect on Analyte Charge State, Signal Intensity, and Stability in Negative Ion Electrospray Mass Spectrometry; Implications for the Mechanism of Negative Ion Formation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 1993, 4, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, C.; Aldana Mejía, J.A.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Gambeta Borges, C.H.; Martins, C.H.G.; Sola Veneziani, R.C.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Bastos, J.K. Occurrence, Chemical Composition, Biological Activities and Analytical Methods on Copaifera Genus—A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, K. de S.; Yoshida, M.; Scudeller, V. V Detection of Adulterated Copaiba (Copaifera Multijuga Hayne) Oil-Resins by Refractive Index and Thin Layer Chromatography. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2009, 19, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, M.E.; Zoghbi, M. das G.B.; Pinto, J.E.B.P.; Bertolucci, S.K.V. Chemical Variability of the Volatiles of Copaifera Langsdorffii Growing Wild in the Southeastern Part of Brazil. Biochem Syst Ecol 2012, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.G. da; Cortesi, N.; Fusari, P. Copaiba Oleoresin: Evaluation of the Presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2010, 46, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, B.C.; Costa-Lotufo, L. V; Moraes, M.O.; Burbano, R.R.; Silveira, E.R.; Cunha, K.M.A.; Rao, V.S.N.; Moura, D.J.; Rosa, R.M.; Henriques, J.A.P. Genotoxicity Evaluation of Kaurenoic Acid, a Bioactive Diterpenoid Present in Copaiba Oil. Food and chemical toxicology 2006, 44, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsaki, A.; Yan, L.T.; Ito, S.; Edatsugi, H.; Iwata, D.; Komoda, Y. The Isolation and in Vivo Potent Antitumor Activity of Clerodane Diterpenoid from the Oleoresin of the Brazilian Medicinal Plant, Copaifera Langsdorfi Desfon. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1994, 4, 2889–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, K. Accelerator of Collagen Production 2005.

- Símaro, G.V.; Lemos, M.; da Silva, J.J.M.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Arruda, C.; Schneider, A.H.; de Souza Wanderley, C.W.; Carneiro, L.J.; Mariano, R.L.; Ambrósio, S.R. Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Copaifera Pubiflora Benth Oleoresin and Its Major Metabolite Ent-Hardwickiic Acid. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 271, 113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, B.M.R.; Wimalasiri, W.R.; Bandara, K.A.N.P. Isolation and Insecticidal Activity of (-)-Hardwickiic Acid from Croton Aromaticus. Planta Med 1987, 53, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, M.; Stien, D.; Beauchêne, J.; Herbette, G.; McLean, J.P.; Thibaut, A.; Thibaut, B. Extractives of the Tropical Wood Wallaba (Eperua Falcata Aubl.) as Natural Anti-Swelling Agents. 2010.

- Braz Filho, R.; Gottlieb, O.R.; Pinho, S.L.V.; Monte, F.J.Q.; Da Rocha, A.I. Flavonoids from Amazonian Leguminosae. Phytochemistry.

| Experiment dates |

Target analytes or Target substances | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardwickiic acid | CV% | Methyl hardwickiate | CV% | Copalic acid | CV% | Methyl copalate | CV% | Patagonic acid | CV% | Methyl patagonate | CV% | Agathic acid | CV% | Methyl ester of agathic acid | CV% | |

| May 15, 2024 | 1975121726 | 8.0 | 1512316 | 5.1 | 1203063795 | 7.7 | 921009 | 4.4 | 74788718 | 7.7 | 891007 | 5.2 | 399396558 | 7.5 | 509843 | 6.2 |

| May 20, 2024 | 1926711350 | 1341619 | 1114681593 | 870510 | 64791889 | 862986 | 406791632 | 498032 | ||||||||

| May 25, 2024 | 1711628436 | 1470515 | 1223025777 | 941617 | 74937278 | 789675 | 453361272 | 569872 | ||||||||

| June 4, 2024 | 2075347716 | 1421008 | 1098075485 | 858979 | 77429128 | 871585 | 381595128 | 543929 | ||||||||

| Experiment dates |

Target analytes or Target substances | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardwickiic acid | CV% | Methyl hardwickiate | CV% | Copalic acid | CV% | Methyl copalate | CV% | Patagonic acid | CV% | Methyl patagonate | CV% | Agathic acid | CV% | Methyl ester of agathic acid | CV% | |

| May 15, 2024 | 177534771 | 6.0 | 122541 | 6.1 | 109567508 | 5.2 | 76870 | 8.5 | 7278871 | 7.6 | 79100 | 8.5 | 37939253 | 4.9 | 48209 | 4.1 |

| May 20, 2024 | 169568903 | 130981 | 152698547 | 64191 | 6479188 | 75298 | 39891163 | 47981 | ||||||||

| May 25, 2024 | 162671135 | 131701 | 191469162 | 67078 | 7093297 | 75465 | 40459027 | 50629 | ||||||||

| June 4, 2024 | 186713428 | 142216 | 100330879 | 65132 | 7798235 | 89698 | 36289712 | 52298 | ||||||||

| Class of natural products | Substance detected | Molecular formula [M] | m/z [M-H]- | m/z [M+H]+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyacetylene | (R)-(-)-Falcarinol | C17H24O | 243.17535 | |

| Benzoquinone | 5-O-ethyl embelin | C19H30O4 | 321.20731 | |

| Embelin | C17H26O4 | |||

| Fatty Acid | Methyl palmitate | C17H34O2 | 288.28931 | |

| (13Z)-8-hydroxyoctadecene-9,11-diynoic acid | C18H26O3 | 289.18121 | ||

| α-Linolenic acid | C18H30O2 | 277.21741 | ||

| Ricinoleic Acid | C18H34O3 | 297.24380 | ||

| Azelaic acid | C9H16O4 | 187.09711 | ||

| Amino Acid | L-Tyrosine methyl ester | C10H13NO3 | 194.08177 | |

| Polyene | (9cis)-Retinal | C20H28O | 285.22107 | |

| Diterpene | (E,E,E)-3,7,11,15-Tetramethylhexadeca-1,3,6,10,14-pentaene | C20H32 | 273.25748 | |

| Triterpene | Betulin | C30H50O2 | 443.38809 | |

| Ursolic acid | C30H48O3 | 455.35306 | ||

|

Phenolic |

1-(5-Hexyl-2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethenone | C14H20O3 | 254.17482 [M+NH4]+ | |

| 1-(2,6-Dihydroxyphenyl)-1,3-dodecanedione | C18H26O4 | 307.19009 | ||

| p-hydroxy benzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 137.02441 | ||

| Gallic acid | C27H20O5 | 425.13835 | ||

| Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | 300.99899 | ||

| Flavonoids | 7-Hydroxy-2-methyl-4H-chromen-4-one | C10H8O3 | 177.05460 | |

| Catechin | C15H14O6 | 289.07176 | ||

| Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | 289.07176 | ||

| Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 191.05611 | ||

| Quercitrin | C21H20O11 | 447.09328 | ||

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 301.03537 | ||

| Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 285.04046 | ||

| Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 269.04554 | ||

| Dihydromyricetin | C15H12O8 | 319.04594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).