Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materiales and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Copoazu Collection and Processing

2.3. VOCs Analysis and Optimization

2.3.1. Analysis of Volatile Metabolites Using HS-SPME-GC-MS

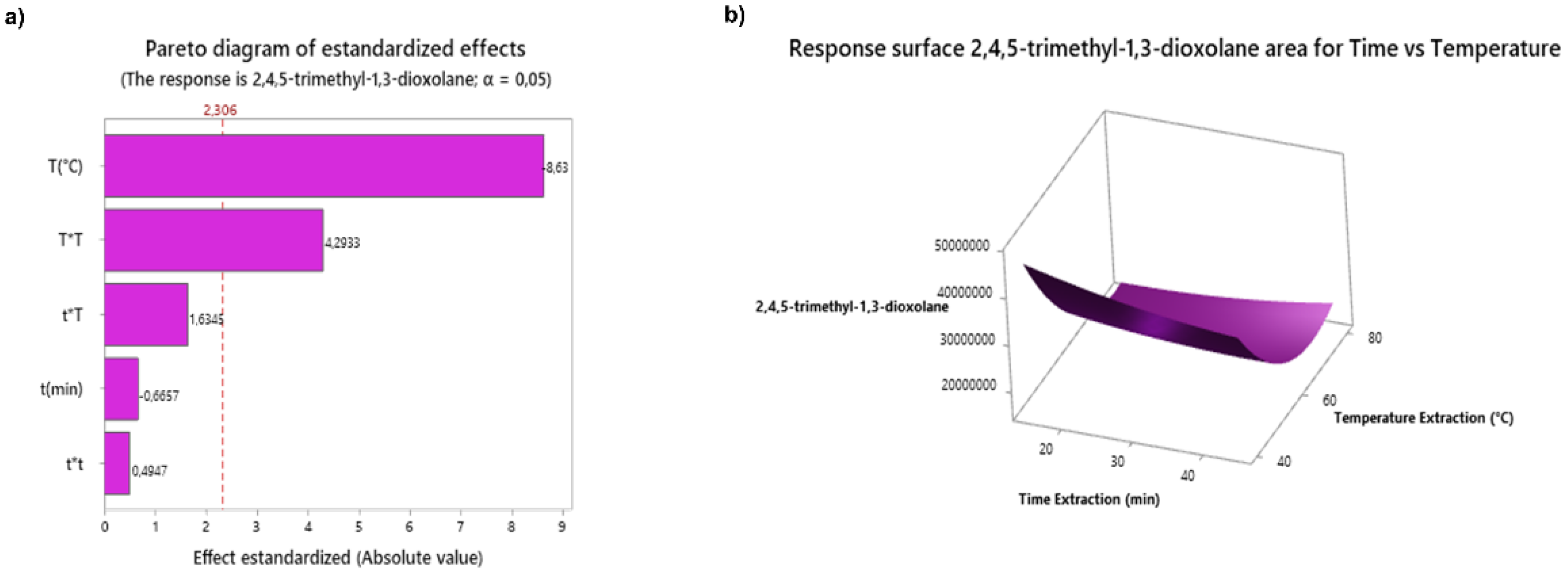

2.3.2. Optimization of Analysis Conditions using Desing of Experiments

2.3.3. Quality Control

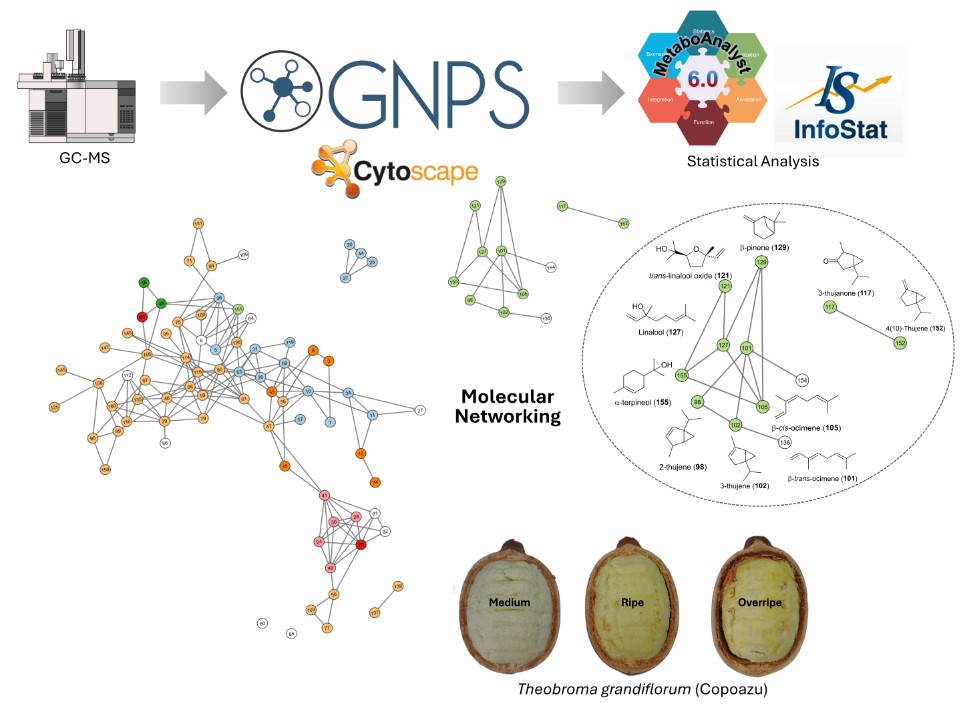

2.4. Data Treatment, Metabolite Annotation and Molecular Networking

2.5. Characterization of Copoazu Maturation Stages

2.5.2. ATR-FTIR Analysis

2.5.3. Carotenoids Analysis by HPLC-DAD

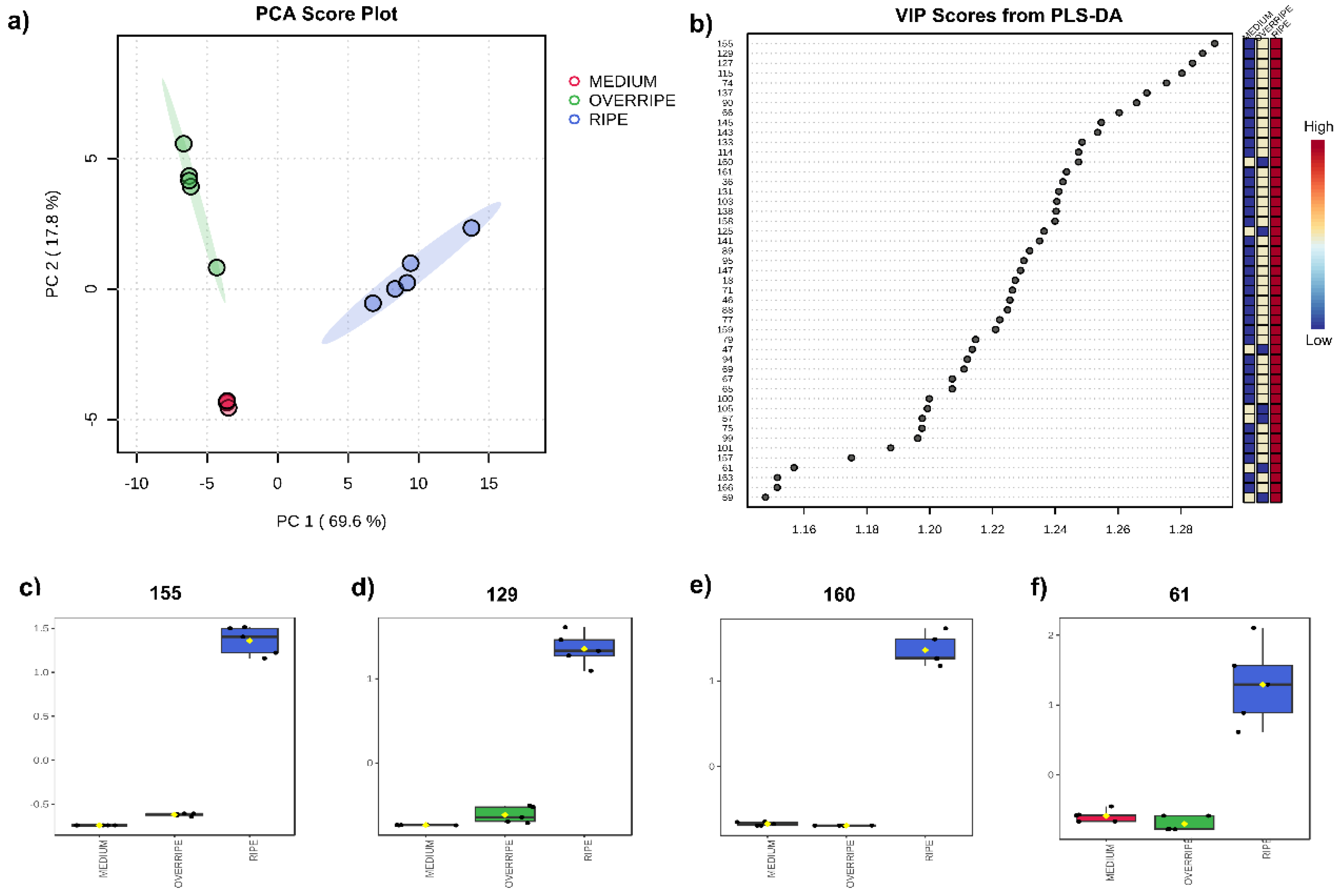

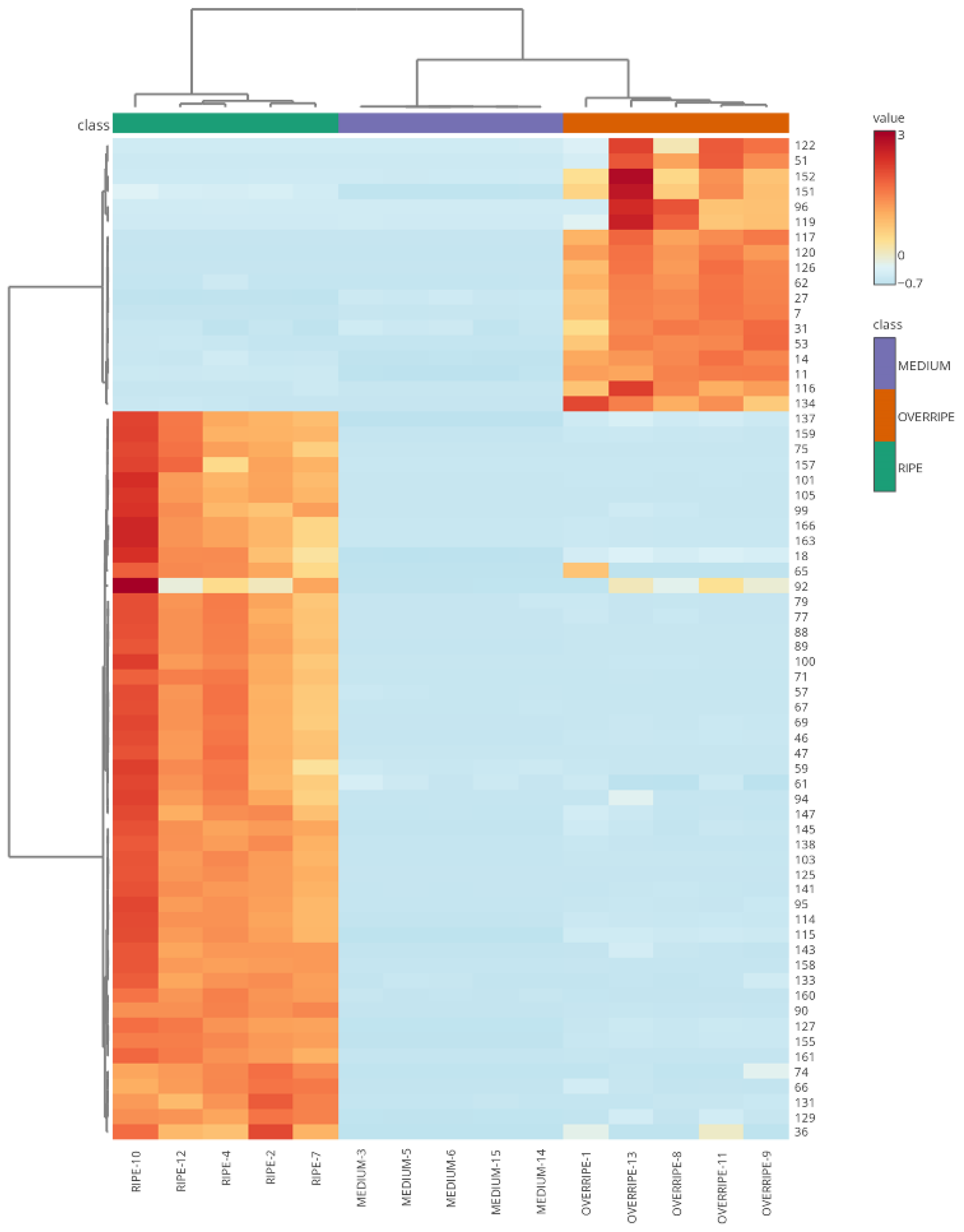

2.5.4. Statistical Analysis for the Characterization of Maturation States of Copoazu

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Volatile Metabolites Using HS-SPME-GC-MS

3.2. DoE

3.3. Maturation State Indices

3.3.1. Characterization of Copoazu Maturation States by ATR-FTIR

3.3.2. Carotenoid Analysis by HPLC-DAD

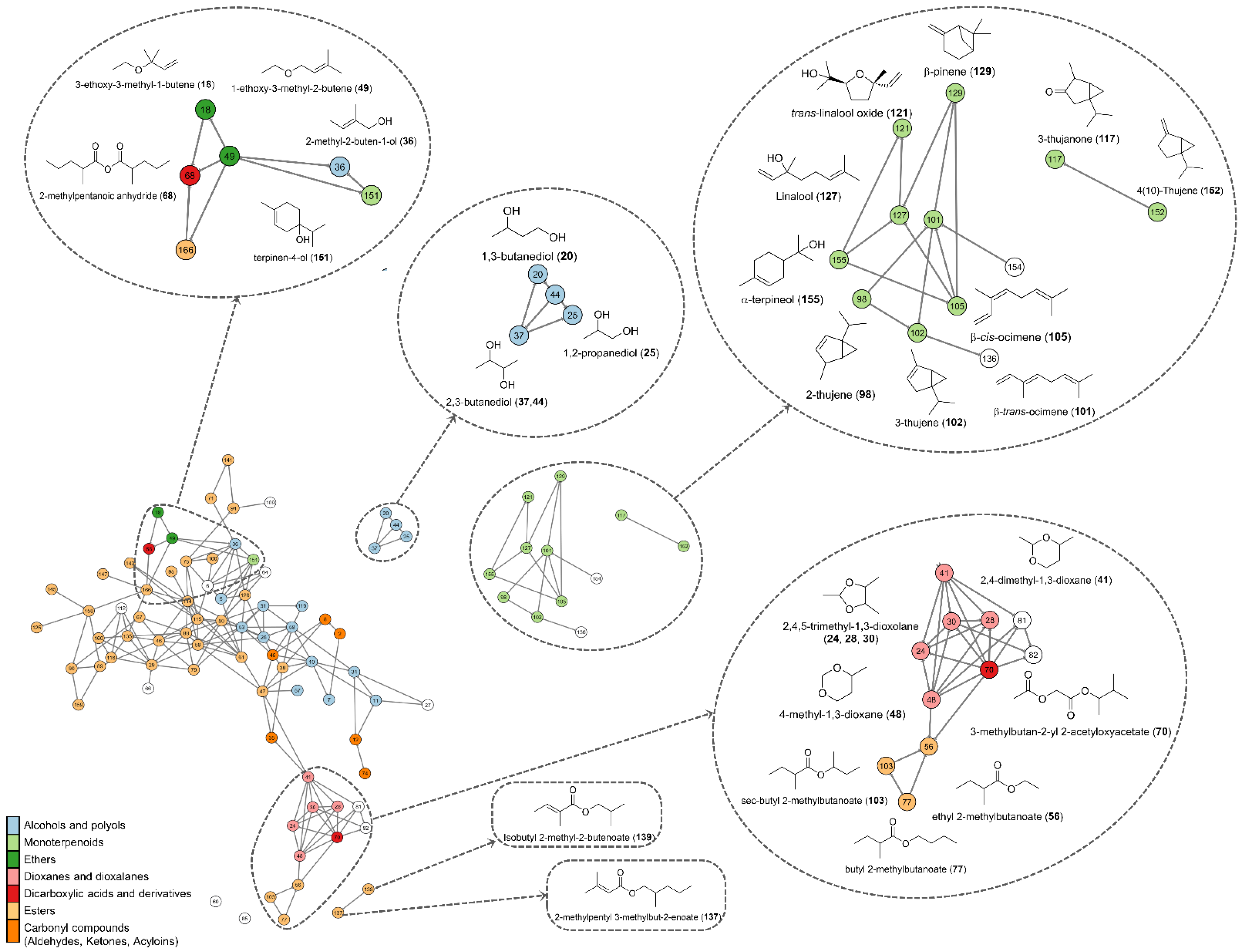

3.4. Volatilomics and Molecular Networking Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

References

- E. Lagneaux, F. E. Lagneaux, F. Andreotti, C.M. Neher, Cacao, copoazu and macambo: Exploring Theobroma diversity in smallholder agroforestry systems of the Peruvian Amazon, Agroforestry Systems 95 (2021) 1359–1368. [CrossRef]

- V.A.C. de Abreu, R. V.A.C. de Abreu, R. Moysés Alves, S.R. Silva, J.A. Ferro, D.S. Domingues, V.F.O. Miranda, A.M. Varani, Comparative analyses of Theobroma cacao and T. grandiflorum mitogenomes reveal conserved gene content embedded within complex and plastic structures, Gene 849 (2023) 146904. [CrossRef]

- A.L.F. Pereira, V.K.G. A.L.F. Pereira, V.K.G. Abreu, S. Rodrigues, Cupuassu—Theobroma grandiflorum, Exotic Fruits Reference Guide (2018) 159–162. [CrossRef]

- D. Albuquerque da Silva, A. D. Albuquerque da Silva, A. Manoel da Cruz Rodrigues, A. Oliveira dos Santos, R. Salvador-Reyes, L.H. Meller da Silva, Physicochemical and technological properties of pracaxi oil, cupuassu fat and palm stearin blends enzymatically interesterified for food applications, LWT 184 (2023) 114961. [CrossRef]

- L.L. Orduz-Díaz, K. L.L. Orduz-Díaz, K. Lozano-Garzón, W. Quintero-Mendoza, R. Díaz, J.E.C. Cardona-Jaramillo, M.P. Carrillo, D.C. Guerrero, M.S. Hernández, Effect of Fermentation and Extraction Techniques on the Physicochemical Composition of Copoazú Butter (Theobroma grandiflorum) as an Ingredient for the Cosmetic Industry, Cosmetics 2024, Vol. 11, Page 77 11 (2024) 77. [CrossRef]

- T.F.S. Curimbaba, L.D. T.F.S. Curimbaba, L.D. Almeida-Junior, A.S. Chagas, A.E.V. Quaglio, A.M. Herculano, L.C. Di Stasi, Prebiotic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of edible Amazon fruits, Food Biosci 36 (2020) 100599. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Costa, M.L.G. M.P. Costa, M.L.G. Monteiro, B.S. Frasao, V.L.M. Silva, B.L. Rodrigues, C.C.J. Chiappini, C.A. Conte-Junior, Consumer perception, health information, and instrumental parameters of cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) goat milk yogurts, J Dairy Sci 100 (2017) 157–168. [CrossRef]

- P.D. de Oliveira, D.A. P.D. de Oliveira, D.A. da Silva, W.P. Pires, C.V. Bezerra, L.H.M. da Silva, A.M. da Cruz Rodrigues, Enzymatic interesterification effect on the physicochemical and technological properties of cupuassu seed fat and inaja pulp oil blends, Food Research International 145 (2021) 110384. [CrossRef]

- S. Melo, J. S. Melo, J. Weltman, A. de Oliveira, J. Herman, P. Efraim, Cupuassu from bean to bar: Sensory and hedonic characterization of a chocolate-like product, Food Research International 155 (2022) 111039. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, X. Y. Chen, X. Wu, X. Wang, Y. Yuan, K. Qi, S. Zhang, H. Yin, PusALDH1 gene confers high levels of volatile aroma accumulation in both pear and tomato fruits, J Plant Physiol 290 (2023) 154101. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, B. X. Chen, B. Fedrizzi, P.A. Kilmartin, S.Y. Quek, Development of volatile organic compounds and their glycosylated precursors in tamarillo (Solanum betaceum Cav.) during fruit ripening: A prediction of biochemical pathway, Food Chem 339 (2021) 128046. [CrossRef]

- F. das C. do A. SOUZA, E.P. F. das C. do A. SOUZA, E.P. SILVA, J.P.L. AGUIAR, Vitamin characterization and volatile composition of camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia (HBK) McVaugh, Myrtaceae) at different maturation stages, Food Science and Technology 41 (2021) 961–966. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Quijano, J.A. C.E. Quijano, J.A. Pino, Volatile compounds of copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum Schumann) fruit, Food Chem 104 (2007) 1123–1126. [CrossRef]

- R. Boulanger, J. R. Boulanger, J. Crouzet, Free and bound flavour components of Amazonian fruits: 3-glycosidically bound components of cupuacu, Food Chem 70 (2000). [CrossRef]

- C. Cabral, D.J. C. Cabral, D.J. Charles, J.E. Simon, Volatile Fruit Constituents of Theobroma grandiflorum, 1991. [CrossRef]

- F. Augusto, A.L.P. F. Augusto, A.L.P. Valente, E. dos Santos Tada, S.R. Rivellino, Screening of Brazilian fruit aromas using solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, J Chromatogr A 873 (2000) 117–127. [CrossRef]

- M.R.B. Franco, T. M.R.B. Franco, T. Shibamoto, Volatile Composition of Some Brazilian Fruits: Umbu-caja (Spondias citherea), Camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia), Araça-boi (Eugenia stipitata), and Cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum), J Agric Food Chem 48 (2000) 1263–1265. [CrossRef]

- J. Xie, X. J. Xie, X. Li, W. Li, H. Ding, J. Yin, S. Bie, F. Li, C. Tian, L. Han, W. Yang, X. Song, H. Yu, Z. Li, Characterization of the key volatile organic components of different parts of fresh and dried perilla frutescens based on headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and headspace solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, Arabian Journal of Chemistry 16 (2023) 104867. [CrossRef]

- C. Carazzone, J.P.G. C. Carazzone, J.P.G. Rodríguez, M. Gonzalez, G.-D. López, Volatilomics of Natural Products: Whispers from Nature, in: X. Zhan (Ed.), Metabolomics, IntechOpen, Rijeka, 2021: p. Ch. 4. [CrossRef]

- M. Marinaki, I. M. Marinaki, I. Sampsonidis, A. Lioupi, P. Arapitsas, N. Thomaidis, K. Zinoviadou, G. Theodoridis, Development of two-level Design of Experiments for the optimization of a HS-SPME-GC-MS method to study Greek monovarietal PDO and PGI wines, Talanta 253 (2023) 123987. [CrossRef]

- H. Ebrahimi, R. H. Ebrahimi, R. Leardi, M. Jalali-Heravi, Experimental design in analytical chemistry -Part I: Theory, J AOAC Int 97 (2014) 3–11. [CrossRef]

- R.S. Nunes, G.T.M. R.S. Nunes, G.T.M. Xavier, A.L. Urzedo, P.S. Fadini, M. Romeiro, T.G.S. Guimarães, G. Labuto, W.A. Carvalho, Cleaner production of iron-coated quartz sand composites for efficient phosphorus adsorption in sanitary wastewater: A design of experiments (DoE) approach, Sustain Chem Pharm 35 (2023) 101206. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Galeano, B.H. P.G. Galeano, B.H. Zimmermann, C. Carazzone, Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry and multivariate analysis of the de novo pyrimidine pathway metabolites, Biomolecules 9 (2019). [CrossRef]

- M. Gorbounov, J. M. Gorbounov, J. Taylor, B. Petrovic, S. Masoudi Soltani, To DoE or not to DoE? A Technical Review on & Roadmap for Optimisation of Carbonaceous Adsorbents and Adsorption Processes, S Afr J Chem Eng 41 (2022) 111–128. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Chen, M. W.-H. Chen, M. Carrera Uribe, E.E. Kwon, K.-Y.A. Lin, Y.-K. Park, L. Ding, L.H. Saw, A comprehensive review of thermoelectric generation optimization by statistical approach: Taguchi method, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and response surface methodology (RSM), Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 169 (2022) 112917. [CrossRef]

- Baena, L.M. Londoño, G. Taborda, Volatilome study of the feijoa fruit [Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret.] with headspace solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry, Food Chem 328 (2020) 127109. [CrossRef]

- Lua. Vazquez, Maria. Celeiro, Meruyert. Sergazina, Thierry. Dagnac, Maria. Llompart, Optimization of a miniaturized solid-phase microextraction method followed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry for the determination of twenty four volatile and semivolatile compounds in honey from Galicia (NW Spain) and foreign countries, Sustain Chem Pharm 21 (2021) 100451. [CrossRef]

- M.C. Chambers, B. M.C. Chambers, B. MacLean, R. Burke, D. Amodei, D.L. Ruderman, S. Neumann, L. Gatto, B. Fischer, B. Pratt, J. Egertson, K. Hoff, D. Kessner, N. Tasman, N. Shulman, B. Frewen, T.A. Baker, M.Y. Brusniak, C. Paulse, D. Creasy, L. Flashner, K. Kani, C. Moulding, S.L. Seymour, L.M. Nuwaysir, B. Lefebvre, F. Kuhlmann, J. Roark, P. Rainer, S. Detlev, T. Hemenway, A. Huhmer, J. Langridge, B. Connolly, T. Chadick, K. Holly, J. Eckels, E.W. Deutsch, R.L. Moritz, J.E. Katz, D.B. Agus, M. MacCoss, D.L. Tabb, P. Mallick, A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics, Nature Biotechnology 2012 30:10 30 (2012) 918–920. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Aksenov, I. A.A. Aksenov, I. Laponogov, Z. Zhang, S.L.F. Doran, I. Belluomo, D. Veselkov, W. Bittremieux, L.F. Nothias, M. Nothias-Esposito, K.N. Maloney, B.B. Misra, A. V. Melnik, A. Smirnov, X. Du, K.L. Jones, K. Dorrestein, M. Panitchpakdi, M. Ernst, J.J.J. van der Hooft, M. Gonzalez, C. Carazzone, A. Amézquita, C. Callewaert, J.T. Morton, R.A. Quinn, A. Bouslimani, A.A. Orio, D. Petras, A.M. Smania, S.P. Couvillion, M.C. Burnet, C.D. Nicora, E. Zink, T.O. Metz, V. Artaev, E. Humston-Fulmer, R. Gregor, M.M. Meijler, I. Mizrahi, S. Eyal, B. Anderson, R. Dutton, R. Lugan, P. Le Boulch, Y. Guitton, S. Prevost, A. Poirier, G. Dervilly, B. Le Bizec, A. Fait, N.S. Persi, C. Song, K. Gashu, R. Coras, M. Guma, J. Manasson, J.U. Scher, D.K. Barupal, S. Alseekh, A.R. Fernie, R. Mirnezami, V. Vasiliou, R. Schmid, R.S. Borisov, L.N. Kulikova, R. Knight, M. Wang, G.B. Hanna, P.C. Dorrestein, K. Veselkov, Auto-deconvolution and molecular networking of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry data, Nature Biotechnology 2020 39:2 39 (2020) 169–173. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Hackstadt, A.M. A.J. Hackstadt, A.M. Hess, Filtering for increased power for microarray data analysis, BMC Bioinformatics 10 (2009) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- J. Xia, N. J. Xia, N. Psychogios, N. Young, D.S. Wishart, MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation, Nucleic Acids Res 37 (2009) W652–W660. [CrossRef]

- Blaženović, T. Kind, J. Ji, O. Fiehn, Software Tools and Approaches for Compound Identification of LC-MS/MS Data in Metabolomics, Metabolites 8 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N. Garg, A. N. Garg, A. Sethupathy, R. Tuwani, R. Nk, S. Dokania, A. Iyer, A. Gupta, S. Agrawal, N. Singh, S. Shukla, K. Kathuria, R. Badhwar, R. Kanji, A. Jain, A. Kaur, R. Nagpal, G. Bagler, FlavorDB: a database of flavor molecules, Nucleic Acids Res 46 (2018). [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, J.-A. J. Liu, J.-A. Clarke, S. McCann, N.K. Hillier, K. Tahlan, Analysis of Streptomyces Volatilomes Using Global Molecular Networking Reveals the Presence of Metabolites with Diverse Biological Activities, Microbiol Spectr 10 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P. Shannon, A. P. Shannon, A. Markiel, O. Ozier, N.S. Baliga, J.T. Wang, D. Ramage, N. Amin, B. Schwikowski, T. Ideker, Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks, Genome Res 13 (2003) 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- Y. Djoumbou Feunang, R. Y. Djoumbou Feunang, R. Eisner, C. Knox, L. Chepelev, J. Hastings, G. Owen, E. Fahy, C. Steinbeck, S. Subramanian, E. Bolton, R. Greiner, D.S. Wishart, ClassyFire: automated chemical classification with a comprehensive, computable taxonomy, J Cheminform 8 (2016) 1–20. [CrossRef]

- W. Lan, C.M.G.C. W. Lan, C.M.G.C. Renard, B. Jaillais, A. Leca, S. Bureau, Fresh, freeze-dried or cell wall samples: Which is the most appropriate to determine chemical, structural and rheological variations during apple processing using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy?, Food Chem 330 (2020) 127357. [CrossRef]

- L. Zamudio, E. L. Zamudio, E. Suesca, G.D. López, C. Carazzone, M. Manrique, C. Leidy, Staphylococcus aureus Modulates Carotenoid and Phospholipid Content in Response to Oxygen-Restricted Growth Conditions, Triggering Changes in Membrane Biophysical Properties, Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023) 14906. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Agbangba, E. C.E. Agbangba, E. Sacla Aide, H. Honfo, R. Glèlè Kakai, On the use of post-hoc tests in environmental and biological sciences: A critical review, Heliyon 10 (2024) e25131. [CrossRef]

- H. Singh, M. H. Singh, M. Meghwal, P.K. Prabhakar, N. Kumar, Grinding characteristics and energy consumption in cryogenic and ambient grinding of ajwain seeds at varied moisture contents, Powder Technol 405 (2022) 117531. [CrossRef]

- M. Gonzalez, P. M. Gonzalez, P. Palacios-Rodriguez, J. Hernandez-Restrepo, M. González-Santoro, A. Amézquita, A.E. Brunetti, C. Carazzone, First characterization of toxic alkaloids and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the cryptic dendrobatid Silverstoneia punctiventris, Front Zool 18 (2021) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- J. Pawliszyn, Theory of Solid-Phase Microextraction, in: J. Pawliszyn (Ed.), Handbook of Solid Phase Microextraction, Elsevier, Oxford, 2012: pp. 13–59. [CrossRef]

- R. Tahergorabi, S.V. R. Tahergorabi, S.V. Hosseini, Nutraceutical and Functional Food Components, in: Galanakis Charis (Ed.), segunda, Elsevier, Chania, 2017: pp. 5–384. [CrossRef]

- R. Metrani, G.K. R. Metrani, G.K. Jayaprakasha, B.S. Patil, Optimization of Experimental Parameters and Chemometrics Approach to Identify Potential Volatile Markers in Seven Cucumis melo Varieties Using HS–SPME–GC–MS, Food Anal Methods 15 (2022) 607–624. [CrossRef]

- S. Siriamornpun, N. S. Siriamornpun, N. Kaewseejan, Quality, bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of selected climacteric fruits with relation to their maturity, Sci Hortic 221 (2017) 33–42. [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, Y. J. Shi, Y. Xiao, C. Jia, H. Zhang, Z. Gan, X. Li, M. Yang, Y. Yin, G. Zhang, J. Hao, Y. Wei, G. Jia, A. Sun, Q. Wang, Physiological and biochemical changes during fruit maturation and ripening in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.), Food Chem 410 (2023) 135299. [CrossRef]

- L.S. Macarena, J.A.C. L.S. Macarena, J.A.C. María, M.D. Antonio, Olive fruit growth and ripening as seen by vibrational spectroscopy, J Agric Food Chem 58 (2010) 82–87. [CrossRef]

- M. González, A. M. González, A. Domínguez, M.J. Ayora, Hyperspectral FTIR imaging of olive fruit for understanding ripening processes, Postharvest Biol Technol 145 (2018) 74–82. [CrossRef]

- P. Skolik, C.L.M. P. Skolik, C.L.M. Morais, F.L. Martin, M.R. McAinsh, Determination of developmental and ripening stages of whole tomato fruit using portable infrared spectroscopy and Chemometrics, BMC Plant Biol 19 (2019). [CrossRef]

- John, J. Yang, J. Liu, Y. Jiang, B. Yang, The structure changes of water-soluble polysaccharides in papaya during ripening, Int J Biol Macromol 115 (2018) 152–156. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Naranjo, J. A.M. Naranjo, J. Quintero, G.L. Ciro, M.J. Barona, J. de C. Contreras, Characterization of the antioxidant activity, carotenoid profile by HPLC-MS of exotic colombian fruits (goldenberry and purple passion fruit) and optimization of antioxidant activity of this fruit blend, Heliyon 9 (2023) e17819. [CrossRef]

- G.D. López, G. G.D. López, G. Álvarez-Rivera, C. Carazzone, E. Ibáñez, C. Leidy, A. Cifuentes, Bacterial Carotenoids: Extraction, Characterization, and Applications, Crit Rev Anal Chem 53 (2023) 1239–1262. [CrossRef]

- L. Etzbach, A. L. Etzbach, A. Pfeiffer, F. Weber, A. Schieber, Characterization of carotenoid profiles in goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.) fruits at various ripening stages and in different plant tissues by HPLC-DAD-APCI-MSn, Food Chem 245 (2018) 508–517. [CrossRef]

- R. Schex, V.M. R. Schex, V.M. Lieb, V.M. Jiménez, P. Esquivel, R.M. Schweiggert, R. Carle, C.B. Steingass, HPLC-DAD-APCI/ESI-MSn analysis of carotenoids and α-tocopherol in Costa Rican Acrocomia aculeata fruits of varying maturity stages, Food Research International 105 (2018) 645–653. [CrossRef]

- J. Fang, Y. J. Fang, Y. Guo, W. Yin, L. Zhang, G. Li, J. Ma, L. Xu, Y. Xiong, L. Liu, W. Zhang, Z. Chen, Neoxanthin alleviates the chronic renal failure-induced aging and fibrosis by regulating inflammatory process, Int Immunopharmacol 114 (2023) 109429. [CrossRef]

- R.K. Saini, S.H. R.K. Saini, S.H. Moon, E. Gansukh, Y.S. Keum, An efficient one-step scheme for the purification of major xanthophyll carotenoids from lettuce, and assessment of their comparative anticancer potential, Food Chem 266 (2018) 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Aragüez, V. Valpuesta, Metabolic engineering of aroma components in fruits, Biotechnol J 8 (2013) 1144–1158. [CrossRef]

- H. Seo, R.J. H. Seo, R.J. Giannone, Y.H. Yang, C.T. Trinh, Proteome reallocation enables the selective de novo biosynthesis of non-linear, branched-chain acetate esters, Metab Eng 73 (2022) 38–49. [CrossRef]

- S. Klie, S. S. Klie, S. Osorio, T. Tohge, M.F. Drincovich, A. Fait, J.J. Giovannoni, A.R. Fernie, Z. Nikoloski, Conserved changes in the dynamics of metabolic processes during fruit development and ripening across species, Plant Physiol 164 (2014) 55–68. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Barrios, D.C. J.C. Barrios, D.C. Sinuco, A.L. Morales, Compuestos volátiles libres y enlazados glicosídicamente en la pulpa de la uva Caimarona (Pourouma cecropiifolia Mart.), Acta Amazon 40 (2010) 189–198. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Padilla-Jiménez, M.V. S.M. Padilla-Jiménez, M.V. Angoa-Pérez, H.G. Mena-Violante, G. Oyoque-Salcedo, J.L. Montañez-Soto, E. Oregel-Zamudio, Identification of Organic Volatile Markers Associated with Aroma during Maturation of Strawberry Fruits, Molecules 2021, Vol. 26, Page 504 26 (2021) 504. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, M. C. Li, M. Xin, L. Li, X. He, P. Yi, Y. Tang, J. Li, F. Zheng, G. Liu, J. Sheng, Z. Li, J. sun, Characterization of the aromatic profile of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) during ripening by HS-SPME-GC/MS and RNA sequencing, Food Chem 355 (2021) 129685. [CrossRef]

- Ferenczi, N. Sugimoto, R.M. Beaudry, Emission Patterns of Esters and Their Precursors Throughout Ripening and Senescence in ‘Redchief Delicious’ Apple Fruit and Implications Regarding Biosynthesis and Aroma Perception, Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 146 (2021) 297–328. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Nagegowda, P. D.A. Nagegowda, P. Gupta, Advances in biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering of plant specialized terpenoids, Plant Science 294 (2020) 110457. [CrossRef]

- N.A.M. Eskin, E. N.A.M. Eskin, E. Hoehn, Fruits and Vegetables, in: Biochemistry of Foods, Elsevier Inc., 2013: pp. 49–126. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, N. X. Liu, N. Hao, R. Feng, Z. Meng, Y. Li, Z. Zhao, Transcriptome and metabolite profiling analyses provide insight into volatile compounds of the apple cultivar ‘Ruixue’ and its parents during fruit development, BMC Plant Biol 21 (2021) 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Granell, J.L. Rambla, Biosynthesis of Volatile Compounds, in: Graham B. Seymour, Mervin Poole, James J. Giovannoni, Gregory A. Tucker (Eds.), The Molecular Biology and Biochemistry of Fruit Ripening, 2013: pp. 135–161. [CrossRef]

- R. Yue, Z. R. Yue, Z. Zhang, Q. Shi, X. Duan, C. Wen, B. Shen, X. Li, Identification of the key genes contributing to the LOX-HPL volatile aldehyde biosynthesis pathway in jujube fruit, Int J Biol Macromol 222 (2022) 285–294. [CrossRef]

- C.L. Loviso, D. C.L. Loviso, D. Libkind, Síntesis y regulación de compuestos del aroma y el sabor derivados de la levadura en la cerveza: ésteres, Rev Argent Microbiol 50 (2018) 436–446. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Yu, Y.N. A.N. Yu, Y.N. Yang, Y. Yang, M. Liang, F.P. Zheng, B.G. Sun, Free and Bound Aroma Compounds of Turnjujube (Hovenia acerba Lindl.) during Low Temperature Storage, Foods 9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Mostafa, Y. S. Mostafa, Y. Wang, W. Zeng, B. Jin, Floral Scents and Fruit Aromas: Functions, Compositions, Biosynthesis, and Regulation, Front Plant Sci 13 (2022) 860157. [CrossRef]

- R. Guilherme, N. R. Guilherme, N. Rodrigues, Í.M.G. Marx, L.G. Dias, A.C.A. Veloso, A.C. Ramos, A.M. Peres, J.A. Pereira, Sweet peppers discrimination according to agronomic production mode and maturation stage using a chemical-sensory approach and an electronic tongue, Microchemical Journal 157 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Shi, Y. J. Shi, Y. Xiao, C. Jia, H. Zhang, Z. Gan, X. Li, M. Yang, Y. Yin, G. Zhang, J. Hao, Y. Wei, G. Jia, A. Sun, Q. Wang, Physiological and biochemical changes during fruit maturation and ripening in highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.), Food Chem 410 (2023) 135299. [CrossRef]

| GNPS Scan number | tR | Metabolite | Formula | Confidence Level | Identification | ClassyFire (SubClass) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols and polyols | 5 | 2,3 | 2-methylbut-3-en-2-ol | C5H10O | 3 | NIST | Alcohols and polyols |

| 7 | 2,47 | isobutylalcohol | C4H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 10 | 2,93 | butan-1-ol | C4H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 11 | 3,22 | 1-penten-3-ol | C5H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 14 | 3,53 | 3-pentanol | C5H12O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 20 | 3,74 | 1,3-butanediol | C4H10O2 | 3 | GNPS | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 25 | 4,26 | 1,2-Propanediol | C3H8O2 | 3 | GNPS | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 26 | 4,35 | Isoamyl alcohol | C5H12O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 27 | 4,44 | 2-methylbutanol | C5H12O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 31 | 5,41 | 1-pentanol | C5H12O | 3 | NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 34 | 5,53 | 2-penten-1-ol | C5H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 36 | 5,68 | 2-methyl-2-buten-1-ol | C5H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 37 | 5,79 | 2,3-butanediol (Isomer I) | C4H10O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 44 | 6,27 | 2,3-butanediol (Isomer II) | C4H10O2 | 3 | GNPS | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 53 | 8,58 | 2-ethyl-1-butanol | C6H14O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Alcohols and polyols | |

| 58 | 10,25 | 1-hexanol | C6H14O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty alcohols | |

| 119 | 24,12 | 2-ethyl-1-hexanol | C8H18O | 4 | GNPS | Alcohols and polyols | |

| Monoterpenoids | 87 | 19,18 | β-myrcene | C10H16 | 1 | NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids |

| 98 | 21,45 | 2-thujene | C10H16 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Monoterpenoids | |

| 99 | 21,45 | Limonene | C10H16 | 1 | GNPS, NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids | |

| 101 | 22,27 | β-trans-ocimene | C10H16 | 1 | GNPS, NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids | |

| 102 | 22,33 | 3-thujene | C10H16 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Monoterpenoids | |

| 105 | 22,82 | β-cis-ocimene | C10H16 | 1 | GNPS, NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids | |

| 117 | 23,98 | 3-thujanone | C10H16O | 3 | GNPS | Monoterpenoids | |

| 121 | 24,68 | trans-linalool oxide | C10H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Tetrahydrofurans | |

| 127 | 25,35 | linalool | C10H18O | 1 | GNPS, NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids | |

| 129 | 25,44 | β-pinene | C10H16 | 3 | GNPS | Monoterpenoids | |

| 151 | 28,25 | terpinen-4-ol | C10H18O | 3 | NIST | Monoterpenoids | |

| 152 | 28,3 | 4(10)-Thujene | C12H20O | 3 | GNPS | Monoterpenoids | |

| 155 | 28,75 | α-terpineol | C10H18O | 1 | GNPS, NIST, STD | Monoterpenoids | |

| Ethers | 18 | 3,65 | 3-ethoxy-3-methyl-1-butene | C7H14O | 3 | NIST | Ethers |

| 49 | 7,75 | 1-ethoxy-3-methyl-2-butene | C7H14O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Ethers | |

| 64 | 11,3 | 1-butene, 3-butoxy-2-methyl- | C9H18O | 4 | NIST | Ethers | |

| 1,3-dioxanes and 1,3-dioxalanes | 24 | 4,15 | 2,4,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolane (Isomer I) | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | 1,3-dioxolanes |

| 28 | 4,88 | 2,4,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolane (Isomer II) | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | 1,3-dioxolanes | |

| 30 | 5,33 | 2,4,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxolane (Isomer III) | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | 1,3-dioxolanes | |

| 41 | 6,12 | 2,4-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | 1,3-dioxanes | |

| 48 | 7,57 | 4-methyl-1,3-dioxane | C5H10O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | 1,3-dioxanes | |

| 54 | 8,96 | 2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane | C7H14O2 | 3 | NIST | 1,3-dioxanes | |

| Dicarboxylic acids derivatives | 68 | 12,17 | 2-methylpentanoic anhydride | C12H22O3 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Dicarboxylic acids and derivatives |

| 70 | 13,38 | 3-methylbutan-2-yl 2-acetyloxyacetate | C9H16O4 | 3 | GNPS | Dicarboxylic acids and derivatives | |

| Esters | 29 | 5,1 | ethyl isobutanoate | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives |

| 38 | 5,91 | butyl acetate | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 46 | 6,64 | ethyl butanoate | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 47 | 7,25 | butyl acetate | C6H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 56 | 9,07 | ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | C7H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 59 | 10,67 | isoamyl acetate | C7H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 61 | 10,83 | 2-methylbutyl acetate | C7H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 66 | 11,72 | vinyl acetate | C4H6O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 67 | 12,07 | propyl butanoate | C7H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 69 | 12,26 | ethyl pentanoate | C7H14O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 71 | 13,87 | prenyl acetate | C7H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 77 | 15,34 | butyl 2-methylbutanoate | C9H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 75 | 15,34 | pentyl butanoate | C9H18O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 79 | 16,16 | butyl isobutanoate | C8H16O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 80 | 16,33 | isobutyl 2-ethylbutanoate | C8H16O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 86 | 18,92 | ethyl 5-hexenoate | C8H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 88 | 19,62 | butyl butanoate | C8H16O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 89 | 19,95 | ethyl hexanoate | C8H16O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 90 | 20,07 | ethyl isohexanoate | C8H16O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 92 | 20,38 | methyl (E)-2-butenoate | C5H8O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 94 | 20,67 | ethyl-4-hexenoate | C8H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 95 | 20,8 | isomyl Isobutanoate | C9H18O2 | 3 | GNPS | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 100 | 22,1 | 4-pentenyl butanoate | C9H16O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 103 | 22,53 | sec-butyl 2-methylbutanoate | C9H18O2 | 3 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 114 | 23,3 | isopentyl 2-methylpropanoate | C9H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 115 | 23,43 | 2-methylbutyl butanoate | C9H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 116 | 23,56 | pentan-2-yl propyl carbonate | C9H18O3 | 3 | GNPS | Carbonic acid diesters | |

| 125 | 25,2 | propyl hexanoate | C9H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 126 | 25,3 | (E)-2-hexenyl butanoate | C9H18O2 | 4 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 137 | 26,26 | 2-methylpentyl 3-methylbut-2-enoate | C11H20O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 139 | 26,77 | isobutyl 2-methyl-2-butenoate | C9H16O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 141 | 27,05 | 3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl pivalate | C10H18O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carboxylic acid derivatives | |

| 143 | 27,38 | 4-Methylpentyl butanoate | C26H54 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 145 | 27,44 | isobutyl hexanoate | C10H20O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 147 | 27,76 | 3-methyl-2-butenyl hexanoate | C11H20O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acid esters | |

| 157 | 28,81 | ethyl 4-octenoate | C10H18O2 | 3 | NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 158 | 28,88 | butyl hexanoate | C10H20O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 159 | 29,11 | ethyl octanoate | C10H20O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 160 | 30,24 | ethylene glycol dibutyrate | C10H18O4 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| 161 | 30,56 | ethyl 2-phenylacetate | C10H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Benzene and substituted derivatives | |

| 163 | 30,6 | 2-ethylphenyl acetate | C10H12O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Phenol esters | |

| 166 | 30,81 | isopentyl hexanoate | C11H22O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Fatty acid esters | |

| Carbonyl compounds (aldehydes, ketones and acyloins) | 2 | 2,15 | butanal | C4H8O | 3 | NIST | Carbonyl compounds |

| 8 | 2,78 | 3-methylbutanal | C5H10O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 12 | 3,46 | pentan-3-one | C5H10O | 3 | NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 35 | 5,6 | 3-methylpentan-2-one | C6H12O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 45 | 6,5 | hexanal | C6H12O | 3 | GNPS | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 62 | 11,16 | 3-ethoxy-3-methyl-2-butanone | C7H14O2 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 74 | 15,11 | 5-hydroxy-2,7-dimethyl-4-octanone | C10H20O2 | 3 | GNPS | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 84 | 18,77 | 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | C8H14O | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 131 | 25,49 | nonanal | C9H18O | 3 | NIST | Carbonyl compounds | |

| 133 | 25,53 | 2-methylbutanal | C5H10O | 3 | GNPS | Carbonyl compounds | |

| Other compounds | 57 | 9,27 | 2,2-dimethylvaleric acid | C7H14O2 | 3 | GNPS | Fatty acids and conjugates |

| 63 | 11,2 | styrene | C8H8 | 3 | GNPS | Styrenes | |

| 109 | 23 | 2,6-octadiene, 2,7-dimethyl- | C10H18 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Branched unsaturated hydrocarbons | |

| 138 | 26,53 | 1,3-Cyclopentadiene, 1,2,3,4,5-pentamethyl | C10H16 | 2 | GNPS, NIST | Unsaturated hydrocarbons | |

| Unkowms | 33 | 5,41 | unknown | - | 4 | - | |

| 43 | 6,27 | unknown | - | 4 | - | ||

| 51 | 7,8 | unknown | - | 4 | - | ||

| 65 | 11,3 | unknown | - | 4 | - | ||

| 120 | 24,68 | unknown | - | 4 | - | ||

| 122 | 25,16 | unknown | - | 4 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).