1. Introduction

The erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular (Eph) receptor family constitutes the largest subgroup of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and plays pivotal roles in embryogenesis and the maintenance of tissue homeostasis [

1]. In mammals, the Eph-ephrin signaling system comprises five glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored ephrin-A ligands (ephrin-A1 to -A5) and three transmembrane ephrin-B ligands (ephrin-B1 to B3), which engage with their cognate Eph receptors (EphA1–A8, A10, and EphB1–B4, B6) [

2]. Generally, EphA receptors preferentially bind to ephrin-A ligands, while EphB receptors interact with ephrin-B ligands [

1]. Upon cell–cell contact, transmembrane ephrin ligands engage Eph receptors on adjacent cells to initiate the intracellular signaling (forward signaling). In ephrin-B ligands, reverse signaling is also activated in the ephrin-B ligands-expressing cells [

3]. In addition, soluble forms of ephrin-A ligands have been identified in the culture supernatants of various cancer cell lines. These soluble ligands are primarily generated through metalloprotease-mediated cleavage of membrane-bound ephrin-As, leading to autocrine activation of EphA signaling and subsequent cellular responses [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The expression levels of ephrins and Eph receptors are frequently dysregulated in tumors compared to normal tissues, with both upregulation and downregulation being observed [

1,

8]. These molecules exhibit dual roles, functioning either as oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on the context. In certain tumor types, Eph receptors are overexpressed during the early stages of tumorigenesis but become downregulated during the tumor progression, suggesting distinct roles in tumor initiation and progression [

1]. EphA5 has been reported to be overexpressed or mutated in multiple tumors, including lung cancer [

9], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [

10], gastric cancer [

11], and follicular thyroid carcinoma [

12] EphA5 stimulated cellular proliferation and inhibited apoptosis in follicular thyroid carcinoma through activation of STAT3 [

12]. In contrast, the knockdown of EphA5 promoted the migration and invasion of ESCC through activation of β-catenin pathway [

10]. Therefore, EphA5 possesses the oncogenic or tumor suppressive functions depending on the type of tumors.

Overexpression or mutation of Eph receptors, including EphA2, EphA3, EphA5, and EphA7—can render them tumor-associated antigens that potentiate antitumor immune responses [

9,

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, γδ T cells, components of the innate immune system, can utilize their T cell receptors in concert with ephrin-As to recognize the ligand-binding domain of EphA2 on tumor cells, thereby mediating cytotoxicity [

16]. EphA2 forward signaling has also been shown to promote endothelial inflammation, facilitating T cell adhesion and transmigration across the vascular endothelium [

17]. Conversely, in lung epithelial cells, EphA2 suppresses inflammasome activation via tyrosine phosphorylation of the NLRP3 component of the inflammasome complex, which may attenuate pro-tumorigenic inflammatory responses and potentially reduce immune evasion [

18]. EphA5 is mutated in multiple tumor types, including breast and lung cancers. EphA5 mutations are associated with elevated tumor mutation burden, increased neoantigen load, upregulation of immune-related gene expression signatures, and enhanced infiltration of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung adenocarcinomas [

9]. Within an immunotherapy-treated cohort, lung cancer patients harboring EphA5 mutations exhibited significantly prolonged progression-free survival compared to those with wild-type EphA5 [

9].

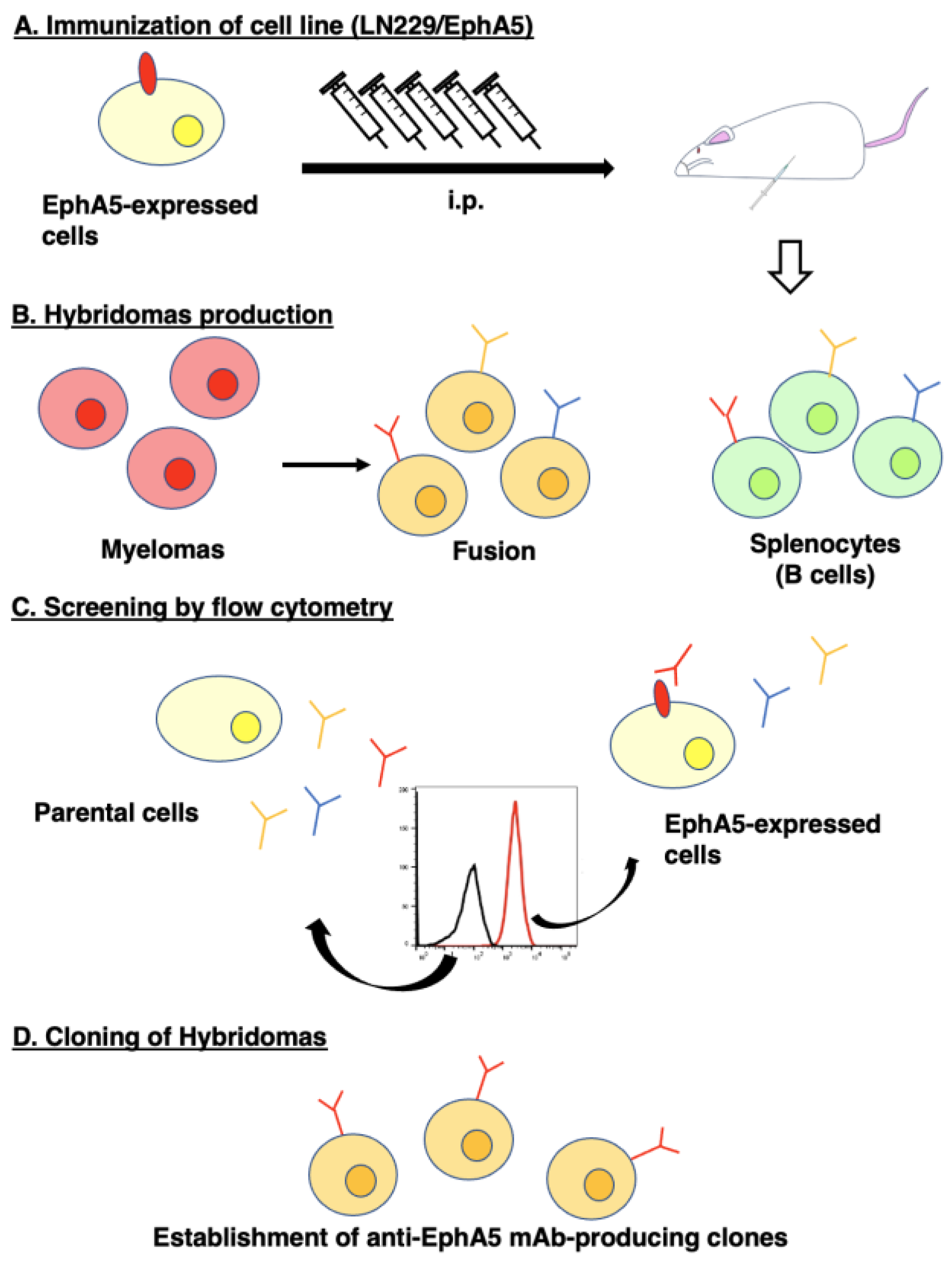

Our group has employed the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method which is useful to obtain various monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against membrane proteins. In this method, antigen-overexpressed cells are used as immunogens, and the flow cytometry-based high-throughput screening enable to obtain the variety of hybridoma clones. Our group have developed various mAbs to membrane proteins such as epidermal growth factor receptor family members [

19,

20], and Eph receptors [

21,

22], chemokine receptors [

23,

24], and cadherin [

25] using the CBIS method. These mAbs can be used for flow cytometry and recognize the variety of epitopes including conformational, linear, and glycan-modified ones. Furthermore, some of mAbs can be used in immunohistochemistry (IHC) and western blotting (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm). This study used the CBIS method to develop anti-EphA5 mAbs for multiple applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, human glioblastoma LN229, mouse myeloma P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1), and human osteosarcoma Saos-2 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The complementary DNA of EphA5 (Catalog No.: RC213206, Accession No.: NM_004439, OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) plus an N-terminal MAP16 tag and an N-terminal PA16 tag were subcloned into a pCAG-Ble vector. Afterward, plasmids were transfected, and stable transfectants [CHO/PA16-EphA5 (CHO/EphA5) and LN229/MAP16-EphA5] were subsequently selected by a cell sorter (SH800, Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using an anti-MAP16 tag mAb (PMab-1 [

26]) and an anti-PA16 tag mAb (NZ-1 [

27]), respectively. Other Eph receptor-expressing CHO-K1 cells (e.g., CHO/EphA2) were established as previously reported [

21].

2.2. Antibodies

An anti-human EphA5 mAb (clone 86731, mouse IgG

1, kappa) was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Another anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-9 were reported previously [

25]. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

2.3. Hybridoma Production

For developing anti-EphA5 mAbs, two 5-week-old female BALB/cAJcl mice purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan) were immunized with LN229/MAP16-EphA5 via the intraperitoneal route and the cell-fusion of P3U1 myeloma cells with the harvested splenocytes were performed as described previously [

21]. On day 6 after cell fusion, the hybridoma supernatants were screened by flow cytometry using CHO/EphA5 and parental CHO-K1 cells. Anti-EphA5 mAbs were purified from the hybridoma supernatants using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova, Kagawa, Japan).

2.4. Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested using 1 mM EDTA (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and incubated with primary mAbs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, they were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse (diluted 1:2000) before fluorescence analysis using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.).

2.5. Determination of the Binding Affinity by Flow Cytometry

CHO/EphA5 and Saos-2 were suspended in 100 μL serially diluted Ea

5Mab-7 or 86731, after which Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (dilution rate; 1:200) was treated. Fluorescence data were subsequently collected and the dissociation constant (

KD) was determined as described previously [

21].

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) CHO/EphA5 and CHO-K1 blocks were prepared using iPGell (Genostaff Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The FFPE cell sections were stained with Ea5Mab-7 (10 μg/mL), 86731 (10 μg/mL), or NZ-9 (1 μg/mL) using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit or the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Development of an Anti-EphA5 mAb, Ea5Mab-7 Using the CBIS Method

To establish mAbs targeting EphA5, we employed the CBIS method using EphA5-overexpressed LN229 cells (

Figure 1). Two female BALB/cAJcl mice were immunized with LN229/MAP16-EphA5 (5 times/week). Subsequently, splenocytes were removed from immunized mice and were fused with P3U1 cells. After confirming hybridoma formation, flow cytometric high throughput screening was conducted to select CHO/EphA5-reactive and parental CHO-K1-nonreactive supernatants of hybridomas. After limiting dilution and additional analysis, we established thirteen clones of anti-EphA5 mAbs. Among them, we selected a clone Ea

5Mab-7 (mouse IgG

1, kappa) by the reactivity and specificity. As shown in

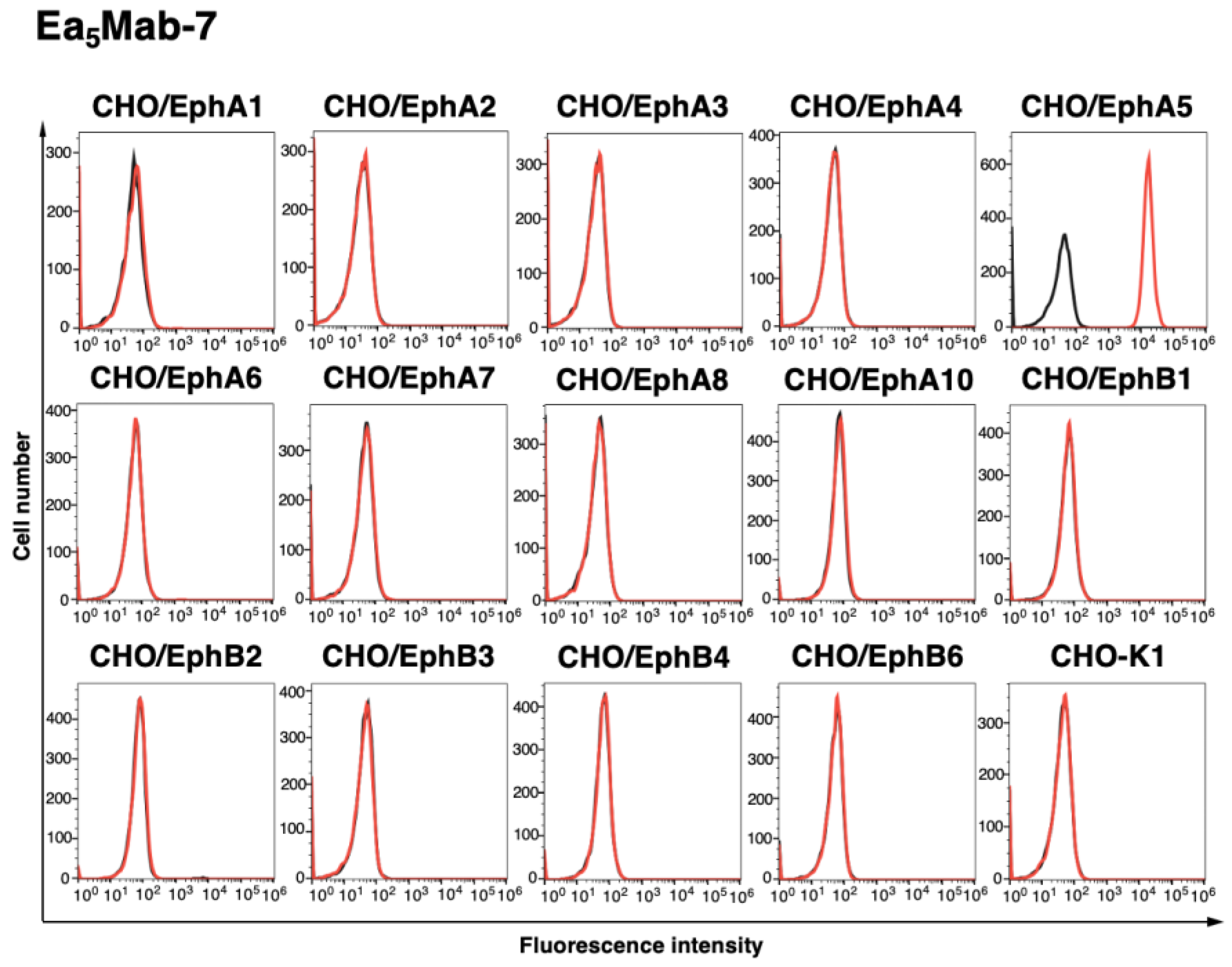

Figure 2, Ea

5Mab-7 recognized CHO/EphA5. Importantly, Ea

5Mab-7 did not react with other Eph receptors (EphA1 to A4, A6 to A8, A10, B1 to B4, and B6)-overexpressed CHO-K1. The expression of each other Eph receptor was previously confirmed by flow cytometry [

21]. This result indicates that Ea

5Mab-7 is a specific mAb against EphA5.

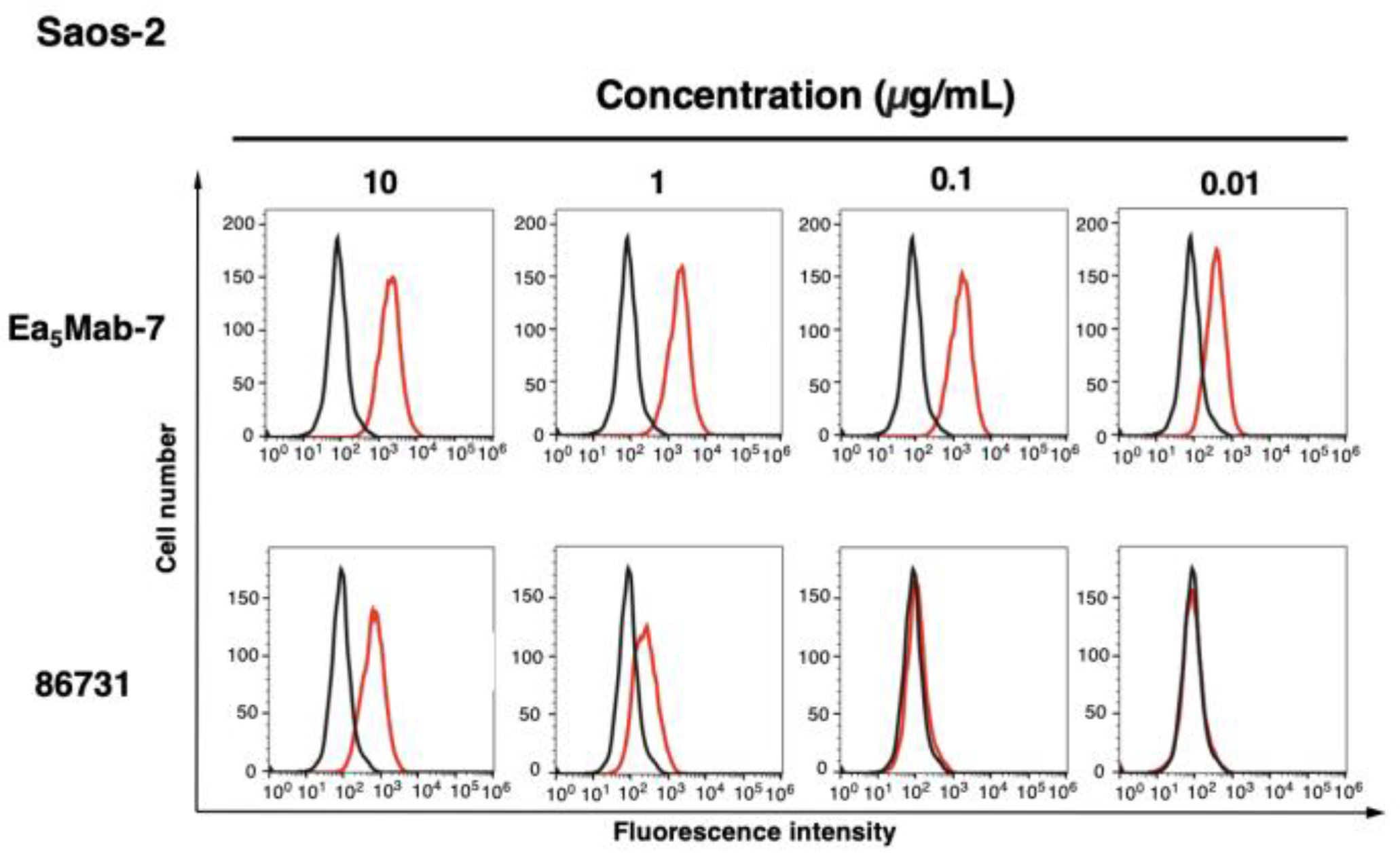

3.2. Investigation of the Reactivity of Anti-EphA5 mAbs Using Flow Cytometry

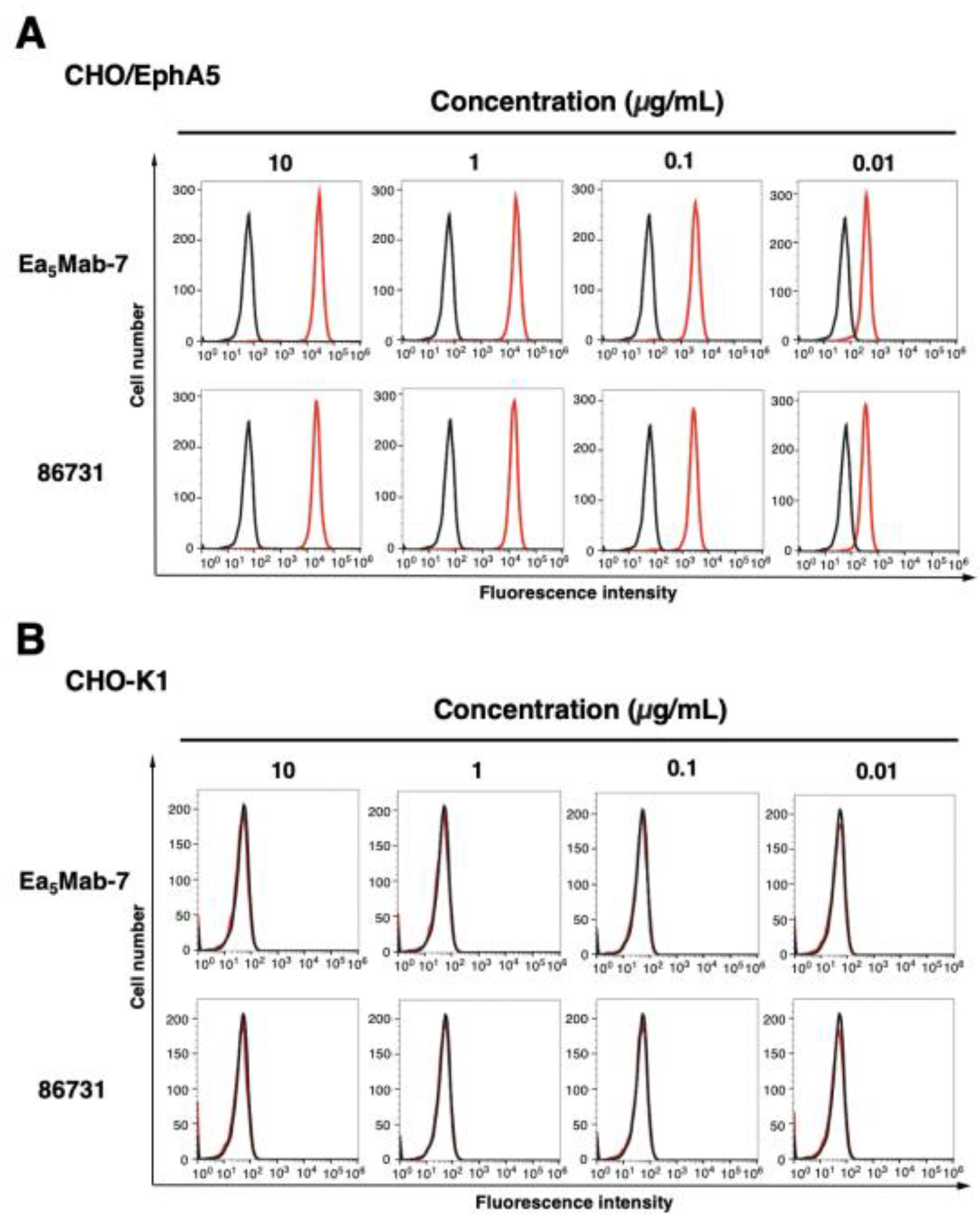

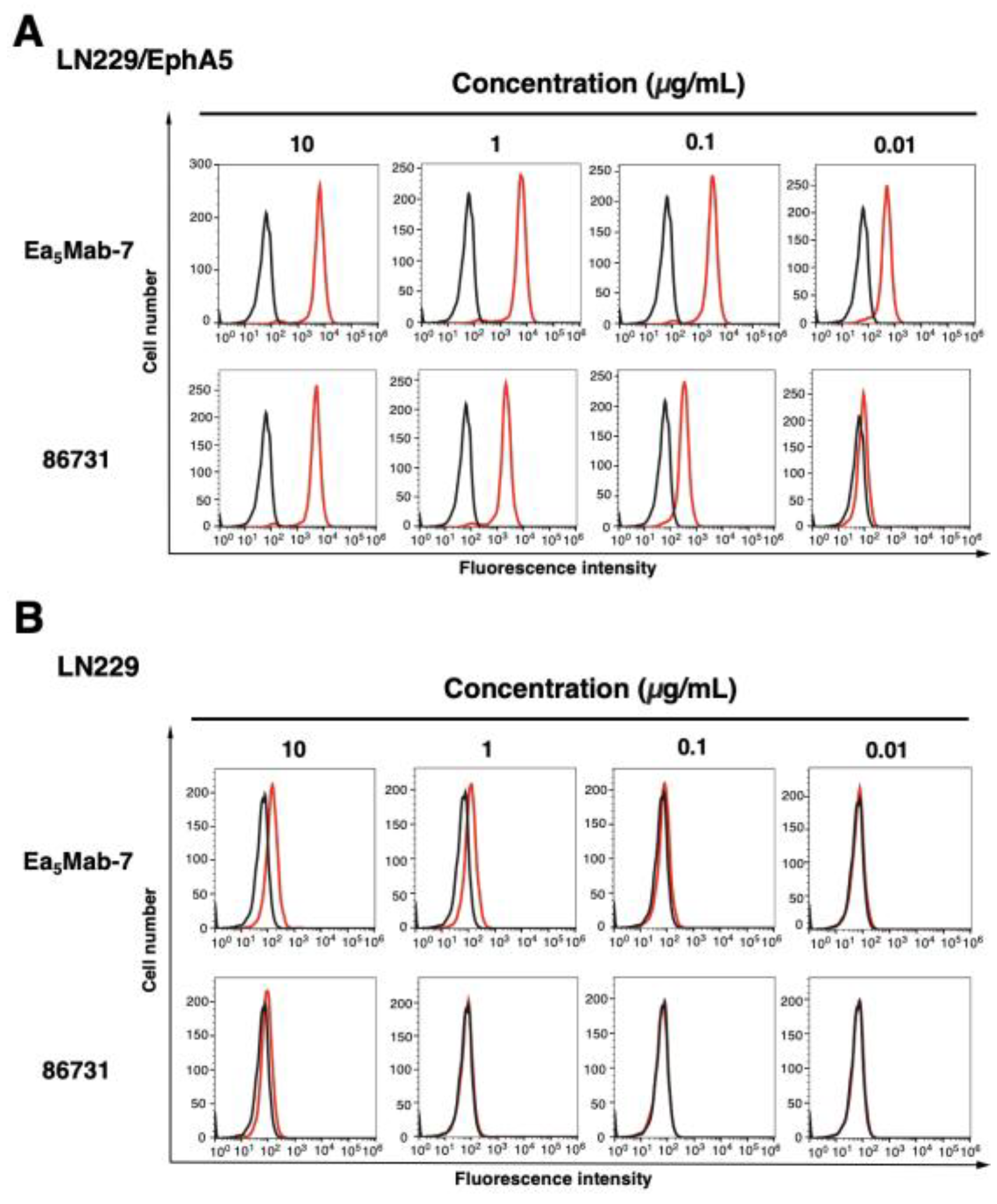

The reactivity of Ea

5Mab-7 to EphA5-positive cells was assessed using flow cytometric analysis. Results showed that Ea

5Mab-7 recognized CHO/EphA5 dose-dependently (

Figure 3A) but did not react with parental CHO-K1 cells (

Figure 3B). Ea

5Mab-7 also showed a dose-dependent reactivity to LN229/EphA5 (

Figure 4A), and weak reactivity to parental LN229 cells (

Figure 4B). Furthermore, Ea

5Mab-7 exhibited a dose-dependent reaction to osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells (

Figure 5). A commercially available anti-EphA5 mAb (clone 86731) showed lower reactivity compared to that of Ea

5Mab-7 (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). These results indicate that Ea

5Mab-7 can detect endogenous and exogenous EphA5 in flow cytometry.

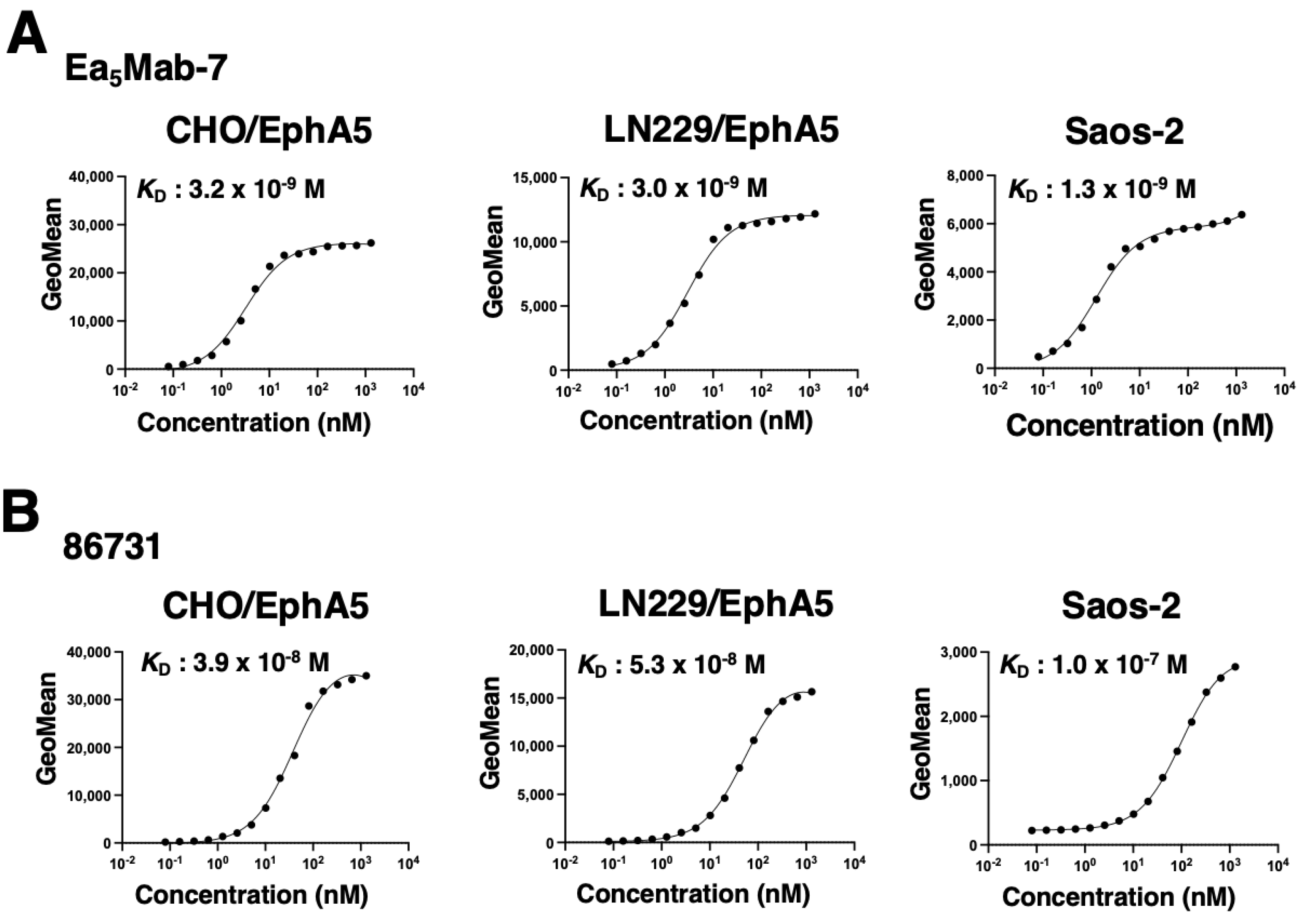

3.3. Determination of the Binding Affinity of Anti-EphA5 mAbs Using Flow Cytometry

To evaluate the binding affinity of Ea

5Mab-7 and 86731, flow cytometry was performed using CHO/EphA5, LN229/EphA5, and Saos-2 cells. The

KD values of Ea

5Mab-7 for CHO/EphA5, LN229/EphA5, and Saos-2 were 3.2 ×10

-9 M, 3.0 ×10

-9 M, and 1.3 ×10

-9 M, respectively (

Figure 6A). The

KD values of 86731 for CHO/EphA5, LN229/EphA5, and Saos-2 were 3.9 ×10

-8 M, 5.3 ×10

-8 M, and 1.0 ×10

-7 M, respectively (

Figure 6B). These results demonstrate that Ea

5Mab-7 possesses higher binding affinity to EphA5-positive cells compared to 86731.

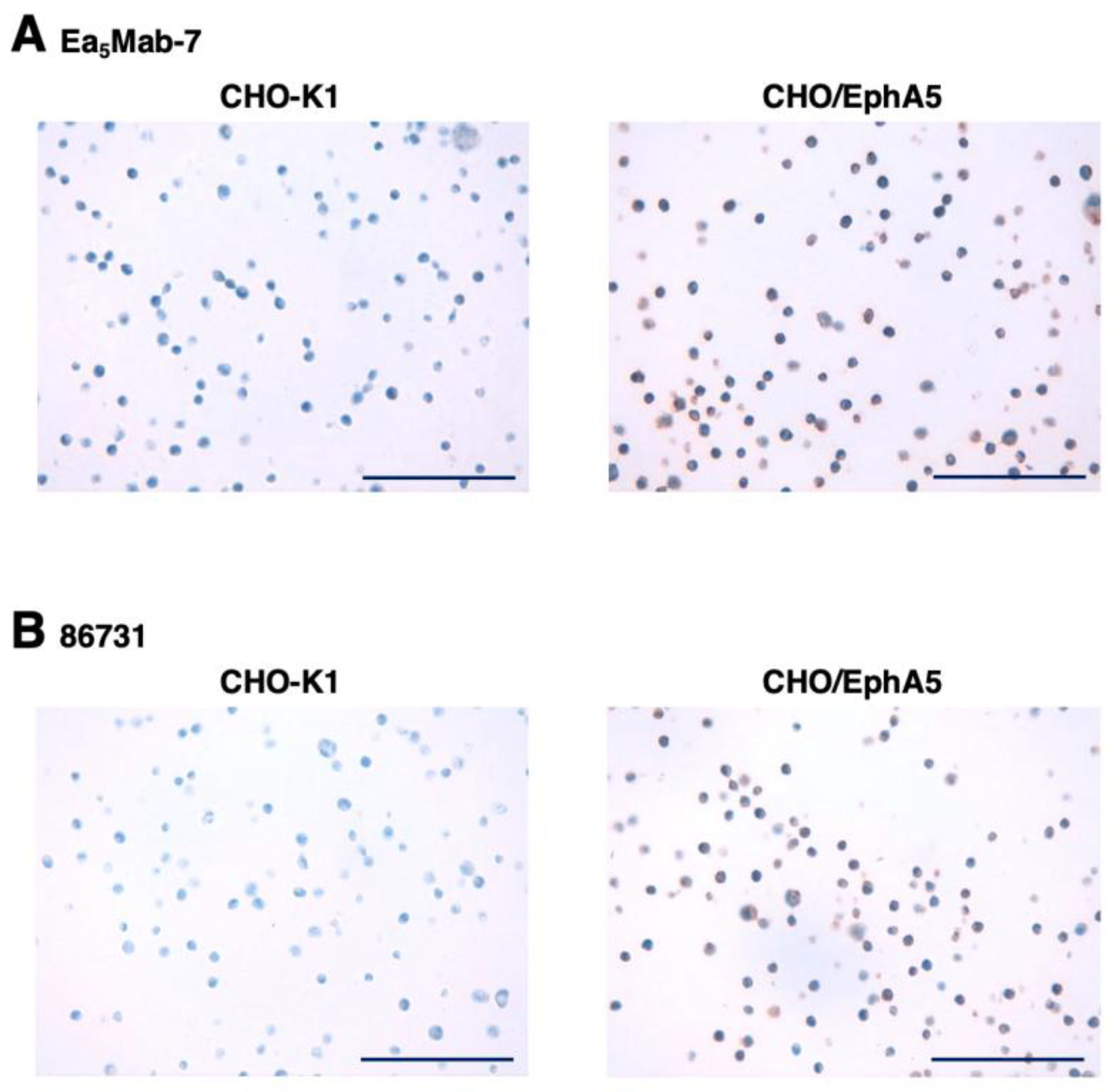

3.4. IHC Using Anti-EphA5 mAbs

To evaluate whether Ea

5Mab-7 can be used for IHC, FFPE CHO-K1 and CHO/EphA5 sections were stained with Ea

5Mab-7 and 86731. A membranous staining by Ea

5Mab-7 and 86731 was observed in CHO/EphA5 (

Figure 7). An anti-PA16 tag mAb, NZ-9 showed more potent reactivity to CHO/EphA5 (supplementary

Figure S1). These results indicate that Ea

5Mab-7 applies to IHC for detecting EphA5-positive cells in FFPE cell samples.

4. Discussion

This study developed and characterized a novel anti-human EphA5 mAb, Ea

5Mab-7, which is suitable for multiple applications. Ea

5Mab-7 recognizes exogenous EphA5 (

Figure 3A and

Figure 4A) and endogenous EphA5 in LN229 (

Figure 4B) and Saos-2 (

Figure 5) by flow cytometry. Ea

5Mab-7 did not recognize other Eph receptor-overexpressed CHO-K1 (

Figure 2). Furthermore, Ea

5Mab-7 could detect EphA5 in IHC (

Figure 7). Ea

5Mab-7 would contribute to the basic research to investigate the molecular functions of EphA5 in multiple applications. We also examined the application of other twelve clones and the information has been updated at “Antibody bank” (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm#EphA5).

We examined the reactivity of Ea

5Mab-7 to various cancer cell lines and found that osteosarcoma Saos-2 showed the relatively high cell surface expression of EphA5 (

Figure 5). Osteosarcoma accounts for the highest proportion of primary malignant bone tumors and is characterized by its pronounced aggressiveness, high metastatic potential, and frequent recurrence following treatment [

28]. Current therapeutic strategies include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. Despite advancements in multimodal treatment approaches, the overall prognosis for osteosarcoma remains poor, particularly in cases with metastasis [

29]. Consequently, the development of more effective therapeutic interventions is essential to improve clinical outcomes.

Osteosarcoma possesses the capacity to invade diverse skeletal sites, permitting its further classification based on distinct histopathological and molecular characteristics [

30]. Osteosarcoma is classified into two major subtypes—central and surface osteosarcomas—each exhibiting unique features in terms of origin, growth pattern, and clinical course [

31]. The classification facilitates a more refined understanding of tumor biology and disease progression. We should investigate whether EphA5 contribute to the classification of osteosarcoma and the disease progression using Ea

5Mab-7.

MAbs targeting Eph receptors have been developed to either activate or inhibit forward signaling, while also mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [

1]. DS-8895a, an anti-EphA2 mAb engineered with a defucosylated Fc region to enhance ADCC, underwent a Phase I clinical trial assessing safety and biodistribution in patients with advanced or metastatic EphA2-positive tumors [

32]. The trial demonstrated limited therapeutic efficacy with stable disease as the best response, and low tumor uptake observed. Consequently, further clinical development of DS-8895a was discontinued due to unfavorable biodistribution profiles [

33]. Ifabotuzumab, a humanized agonistic anti-EphA3 mAb with ADCC activity, was designed to target hematologic malignancies and glioblastoma, and has shown promising results in preclinical models [

34,

35] as well as clinical settings [

1]. In contrast, no clinical studies involving EphA5-targeting mAbs have been reported to date. In our previous work, we engineered mAbs by switching their isotypes to mouse IgG

2a or human IgG

1 to potentiate the ADCC. These class-switched antibodies were utilized in evaluating antitumor efficacy in murine xenograft models [

36,

37]. We have already identified the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of Ea

5Mab-7 (supplementary

Figure S2), and its class-switched variant is expected to serve as a valuable tool for assessing antitumor activity in osteosarcoma xenograft models.

Immunotherapy has demonstrated potential in the management of osteosarcoma, particularly in advanced or refractory cases. A hallmark of osteosarcoma is its capacity to evade immune surveillance, primarily through the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed death-ligand 1, which attenuate antitumor immune responses and permit tumor proliferation [

38]. However, further investigation is still required to establish the clinical use of immune check point inhibitors in osteosarcoma [

31]. In non-small cell lung cancer, the EphA5 mutation has potential as a biomarker to predict the positive effectiveness of immunotherapy [

39]. Further studies are essential to clarify the relationship between EphA5 mutation and/or expression and the effectiveness of immunotherapy in osteosarcoma. Ea

5Mab-7 may contribute the understanding of the mechanism of increased sensitivity to immunotherapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Guanjie Li: Investigation. Tomohiro Tanaka: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization. Hiroyuki Suzuki: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221339 (to Y.K.), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 24K18268 (to T.T.) and 25K10553 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2024, 24, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling complexes in the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem Sci 2024, 49, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisabeth, E.M.; Falivelli, G.; Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptor signaling and ephrins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alford, S.C.; Bazowski, J.; Lorimer, H.; Elowe, S.; Howard, P.L. Tissue transglutaminase clusters soluble A-type ephrins into functionally active high molecular weight oligomers. Exp Cell Res 2007, 313, 4170–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykosky, J.; Palma, E.; Gibo, D.M.; et al. Soluble monomeric EphrinA1 is released from tumor cells and is a functional ligand for the EphA2 receptor. Oncogene 2008, 27, 7260–7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, S.; Watson-Hurthig, A.; Scott, N.; et al. Soluble ephrin a1 is necessary for the growth of HeLa and SK-BR3 cells. Cancer Cell Int 2010, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, X.P.; Song, K.; Shang, Z.J. Ephrin-A1 is up-regulated by hypoxia in cancer cells and promotes angiogenesis of HUVECs through a coordinated cross-talk with eNOS. PLoS One 2013, 8, e74464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Scott, A.M.; Janes, P.W. Eph Receptors in Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lin, A.; Luo, P.; et al. EPHA5 mutation predicts the durable clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther 2021, 28, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. EphA5 knockdown enhances the invasion and migration ability of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via epithelial-mesenchymal transition through activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cancer Cell Int 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.Y.; Jang, G.; Kim, J.; et al. Identification of New Pathogenic Variants of Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2024, 56, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xu, G.; Fan, Y.; et al. EPHA5 promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in Follicular Thyroid Cancer via the STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncogenesis 2025, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, P.W.; Vail, M.E.; Ernst, M.; Scott, A.M. Eph Receptors in the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiuan, E.; Chen, J. Eph Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Tumor Immunity. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 6452–6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.X.; Lin, W.H.; et al. EPHA7 mutation as a predictive biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in multiple cancers. BMC Med 2021, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harly, C.; Joyce, S.P.; Domblides, C.; et al. Human γδ T cell sensing of AMPK-dependent metabolic tumor reprogramming through TCR recognition of EphA2. Sci Immunol 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, S.D.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Albert, P.; et al. EphA2 activation promotes the endothelial cell inflammatory response: a potential role in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012, 32, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xing, J.; Xia, T.; et al. EphA2 phosphorylates NLRP3 and inhibits inflammasomes in airway epithelial cells. EMBO Rep 2020, 21, e49666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Yamada, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. Establishment of EMab-134, a Sensitive and Specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody for Detecting Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells of the Oral Cavity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. H(2)Mab-77 is a Sensitive and Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody Against Breast Cancer. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, M.; et al. Establishment of a highly sensitive and specific anti-EphB2 monoclonal antibody (Eb2Mab-12) for flow cytometry. MI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Development of an anti-human EphA2 monoclonal antibody Ea2Mab-7 for multiple applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 42, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. A novel anti-mouse CCR7 monoclonal antibody, C(7)Mab-7, demonstrates high sensitivity in flow cytometry, western blot, and immunohistochemistry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 41, 101948. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; et al. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CCR5 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-CDH15/M-cadherin monoclonal antibody Ca15Mab-1 for flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2025, 43, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kuno, A.; et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation using a novel anti-podoplanin antibody reacting with its platelet-aggregation-stimulating domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 349, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, Z.; Fan, T.M.; Irudayaraj, J.M.K. Osteosarcoma mechanobiology and therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, K.; Hu, J.; Zhang, C. Advances and challenges in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2025, 197, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.; Sathiadoss, P.; Saifuddin, A.; Sheikh, A. A review of imaging of surface sarcomas of bone. Skeletal Radiol 2021, 50, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, G.S.; Schmidt, A.A.; Willams, L.R.; Wakefield, M.R.; Fang, Y. Osteosarcoma: current insights and advances. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2025, 6, 1002324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, J.; Sue, M.; Yamato, M.; et al. Novel anti-EPHA2 antibody, DS-8895a for cancer treatment. Cancer Biol Ther 2016, 17, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.K.; Parakh, S.; Lee, F.T.; et al. A phase 1 safety and bioimaging trial of antibody DS-8895a against EphA2 in patients with advanced or metastatic EphA2 positive cancers. Invest New Drugs 2022, 40, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenhäuser, C.; Al-Ejeh, F.; Puttick, S.; et al. EphA3 Pay-Loaded Antibody Therapeutics for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, B.W.; Stringer, B.W.; Al-Ejeh, F.; et al. EphA3 maintains tumorigenicity and is a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Anti-HER2 Cancer-Specific mAb, H(2)Mab-250-hG(1), Possesses Higher Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity than Trastuzumab. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Circulating Exosomal PD-L1 at Initial Diagnosis Predicts Outcome and Survival of Patients with Osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. To be, or not to be: the dilemma of immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer harboring various driver mutations. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 10027–10040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).