Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Stable Transfectants

2.2. Antibodies

2.3. Development of Hybridomas

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

3. Results

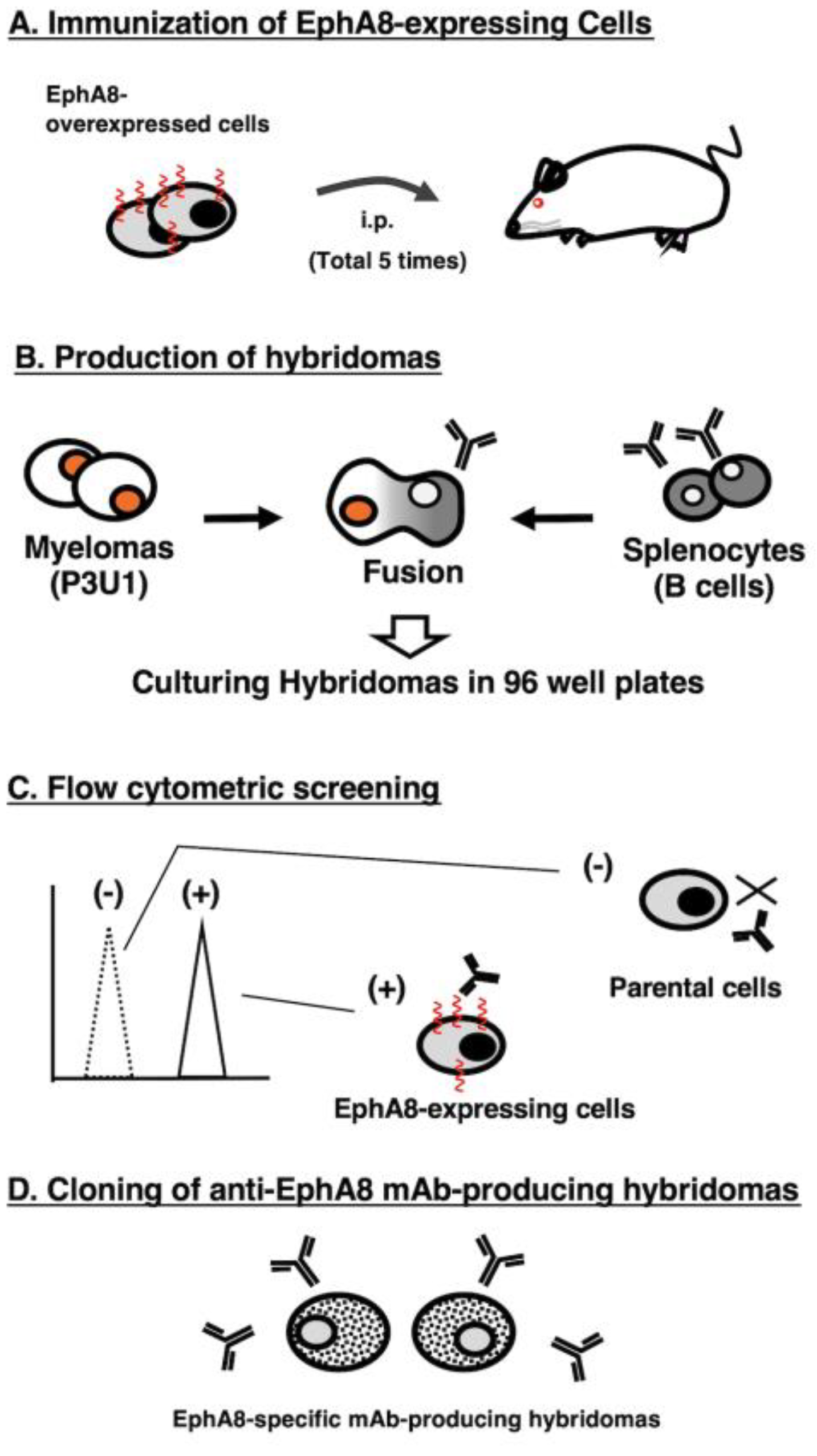

3.1. Development of Anti-EphA8 mAbs Using the CBIS Method

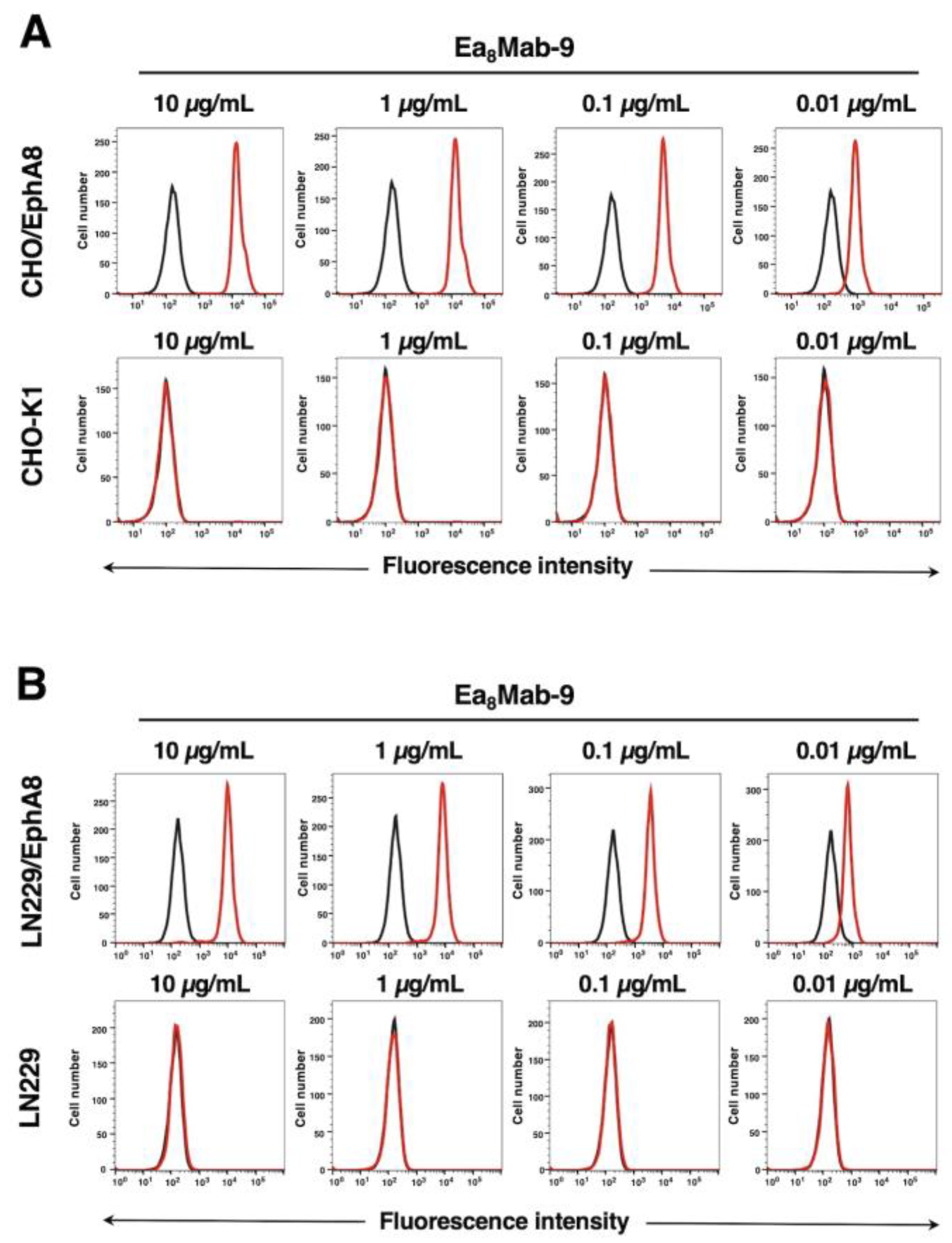

3.2. Flow Cytometric Analysis

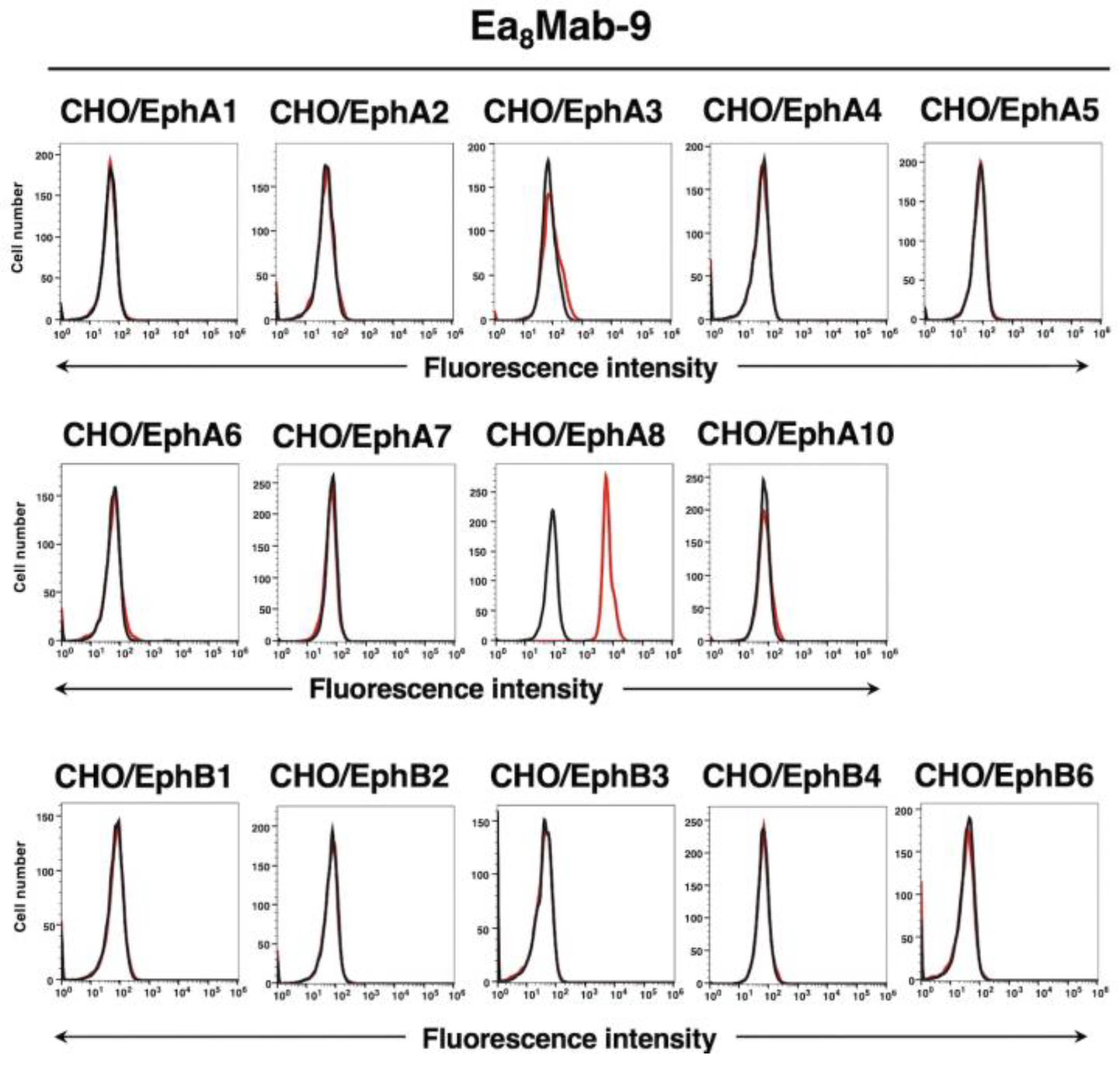

3.3. Specificity of Ea8Mab-9 to Eph Receptor-Expressed CHO-K1 Cells

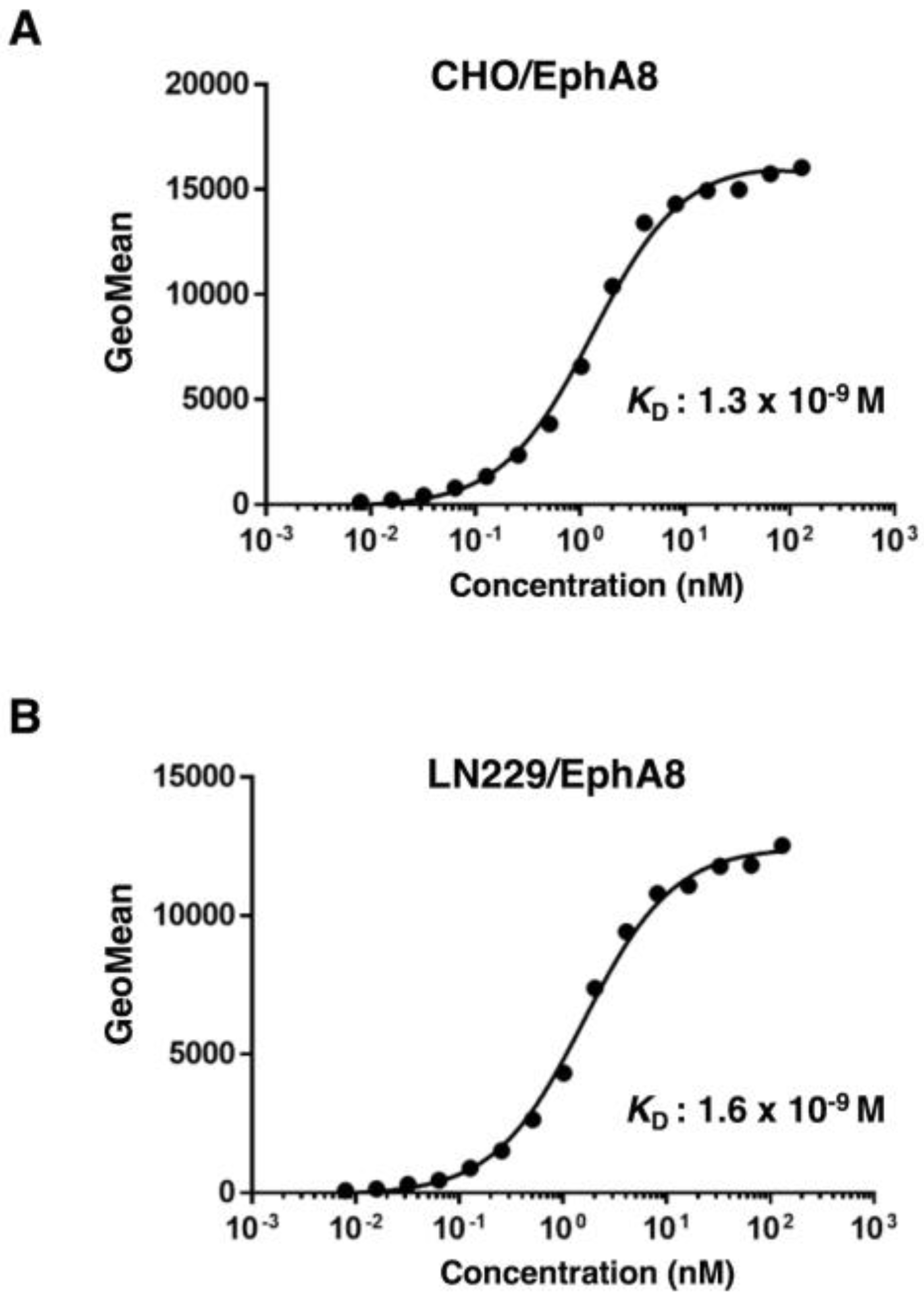

3.4. Determination of the Binding Affinity of Ea8Mab-9 by Flow Cytometry

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuzi, N.L.; Gullick, W.J. eph, the largest known family of putative growth factor receptors. Br J Cancer 1994;69(3): 417-421. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2024;24(1): 5-27. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell 2008;133(1): 38-52. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Watt, V.M. eek and erk, new members of the eph subclass of receptor protein-tyrosine kinases. Oncogene 1991;6(6): 1057-1061.

- Park, S.; Sánchez, M.P. The Eek receptor, a member of the Eph family of tyrosine protein kinases, can be activated by three different Eph family ligands. Oncogene 1997;14(5): 533-542. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, S. Phosphorylation at Tyr-838 in the kinase domain of EphA8 modulates Fyn binding to the Tyr-615 site by enhancing tyrosine kinase activity. Oncogene 1999;18(39): 5413-5422. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Park, S. The EphA8 receptor regulates integrin activity through p110gamma phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in a tyrosine kinase activity-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 2001;21(14): 4579-4597.

- Wang, S.D.; Rath, P.; Lal, B.; et al. EphB2 receptor controls proliferation/migration dichotomy of glioblastoma by interacting with focal adhesion kinase. Oncogene 2012;31(50): 5132-5143. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Bukkapatnam, S.; Van Court, B.; et al. The effects of ephrinB2 signaling on proliferation and invasion in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Carcinog 2020;59(9): 1064-1075. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, E.; Noh, H.; Park, S. Expression of EphA8-Fc in transgenic mouse embryos induces apoptosis of neural epithelial cells during brain development. Dev Neurobiol 2013;73(9): 702-712. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Frisén, J.; Barbacid, M. Aberrant axonal projections in mice lacking EphA8 (Eek) tyrosine protein kinase receptors. Embo j 1997;16(11): 3106-3114. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Shim, S.; Shin, J.; et al. The EphA8 receptor induces sustained MAP kinase activation to promote neurite outgrowth in neuronal cells. Oncogene 2005;24(26): 4243-4256. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Ge, W. EphA8 is a Prognostic Factor for Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit 2018;24: 7213-7222. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Jin, Q.; et al. EphA8 is a prognostic marker for epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7(15): 20801-20809. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Li, P.; et al. EphA8 acts as an oncogene and contributes to poor prognosis in gastric cancer via regulation of ADAM10. J Cell Physiol 2019;234(11): 20408-20419. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Ni, K.; Gu, C.; et al. EphA8 inhibits cell apoptosis via AKT signaling and is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2021;46(2). [CrossRef]

- Lucero, M.; Thind, J.; Sandoval, J.; et al. Stem-like Cells from Invasive Breast Carcinoma Cell Line MDA-MB-231 Express a Distinct Set of Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2020;17(6): 729-738. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Chen, S.; Liu, G.; et al. TUSC7 acts as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res 2017;9(9): 4026-4035.

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X.L.; et al. miR-10a controls glioma migration and invasion through regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition via EphA8. FEBS Lett 2015;589(6): 756-765. [CrossRef]

- Satofuka H, S.H., Tanaka T, Li G, Kaneko MK, Kato Y. An Anti-Human EphA2 Monoclonal Antibody Ea2Mab-7 Shows High Sensitivity for Flow Cytometry, Western Blot, and Immunohistochemical Analyses. Preprint 2024.

- Ubukata R, S.H., Hirose M, Satofuka H, Tanaka T, Kaneko MK, Kato Y. Establishment of a Highly-sensitive Anti-EphB2 Monoclonal Antibody Eb2Mab-3 for Flow Cytometry. Preprint 2024.

- Nanamiya, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an Anti-EphB4 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications Against Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2023;42(5): 166-177.

- Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Detection of high CD44 expression in oral cancers using the novel monoclonal antibody, C(44)Mab-5. Biochem Biophys Rep 2018;14: 64-68.

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016;35(6): 293-299. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014;95: 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Zhou, Y.; Ozawa, T.; et al. Ligand-activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling governs endocytic trafficking of unliganded receptor monomers by non-canonical phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2018;293(7): 2288-2301.

- Perez Verdaguer, M.; Zhang, T.; Paulo, J.A.; et al. Mechanism of p38 MAPK-induced EGFR endocytosis and its crosstalk with ligand-induced pathways. J Cell Biol 2021;220(7). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yamada, N.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Crucial roles of RSK in cell motility by catalysing serine phosphorylation of EphA2. Nat Commun 2015;6: 7679. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, M.; Shin, M.S.; Singhirunnusorn, P.; et al. TAK1-mediated serine/threonine phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor via p38/extracellular signal-regulated kinase: NF-{kappa}B-independent survival pathways in tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29(20): 5529-5539.

- Zhou, Y.; Oki, R.; Tanaka, A.; et al. Cellular stress induces non-canonical activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 through the p38-MK2-RSK signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 2023;299(5): 104699. [CrossRef]

- Paya, L.; Rafat, A.; Talebi, M.; et al. The Effect of Tumor Resection and Radiotherapy on the Expression of Stem Cell Markers (CD44 and CD133) in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2024;18(1): 92-99. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.D.; Araldi, R.P.; Belizario, M.R.; et al. DLK1 Is Associated with Stemness Phenotype in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Cell Lines. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25(22). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sakurai, H. Emerging and Diverse Functions of the EphA2 Noncanonical Pathway in Cancer Progression. Biol Pharm Bull 2017;40(10): 1616-1624. [CrossRef]

- Janes, P.W.; Vail, M.E.; Gan, H.K.; Scott, A.M. Antibody Targeting of Eph Receptors in Cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13(5). [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. Antitumor activities of a defucosylated anti-EpCAM monoclonal antibody in colorectal carcinoma xenograft models. Int J Mol Med 2023;51(2). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against Podocalyxin Exerted Antitumor Activities in Pancreatic Cancer Xenografts. Int J Mol Sci 2023;25(1).

- Arimori, T.; Mihara, E.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Locally misfolded HER2 expressed on cancer cells is a promising target for development of cancer-specific antibodies. Structure 2024;32(5): 536-549.e535. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Antitumor activities against breast cancers by an afucosylated anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody H(2) Mab-77-mG(2a) -f. Cancer Sci 2024;115(1): 298-309.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).