1. Introduction

The participation of children in group or organized physical activities is fundamental for their holistic development, not only in terms of physical health but also in emotional, social, and cognitive aspects [

1]. However, there is a concerning trend where many children are not regularly involved in such activities. This lack of participation can be attributed to a variety of factors, ranging from the increasing dependence on technology to the lack of access to suitable sports programs [

2]. Understanding the causes and seeking solutions to encourage active participation of children in group physical activities is crucial for promoting a healthy lifestyle and optimal development of social skills from an early age [

3].

Regular physical activity improves physical fitness, cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, flexibility, lung capacity, body composition, and metabolic health [

4,

5]. Team sports are especially effective in promoting health in youth, enhancing strength, flexibility, balance, and coordination [

6], while also reducing body fat [

4] and improving cardiorespiratory endurance, notably peak oxygen consumption [

7]. Basketball stands out as a highly integral sport, distinguished by its incorporation of various elements such as sprinting, jumping, and feints, which actively engage both the lower and upper limbs [

8]. As a team sport, it encourages active participant involvement, thereby promoting increased PA and ranks among the sports with the highest levels of practice [

9]. Basketball involves high-intensity training coupled with a consistent workout regimen, leading to comprehensive improvements in physical condition [

10], even in children.

Intensive and frequent physical training can significantly influence cardiovascular health in children and adolescents [

11]. While there are studies that exclusively examine cardiovascular adaptations in response to training, there is limited research that considers physical fitness and its effects on metabolism and body composition. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the health status by examining anthropometric, cardiometabolic, and fitness changes following regular basketball training after school in boys.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

A prospective, non-randomised controlled intervention study with repeated measures was conducted. The protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07007624). The study was designed and reported following the TREND statement guidelines (Supplementary material 1).

A basketball after school program was offered to scholars with a medium social/educative class in Córdoba (Spain). The inclusion criteria were: age between 7-12 y and a good state of health with Tanner stage I (prepuberal). Exclusion criteria included the presence of any clinical or analytical sign of puberty, disease or the use of medication that alters blood pressure (BP) or the glucose or lipid metabolism. The study was designed following the ethical principles for human research of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the local ethics and research committee in the University Reina Sofia Hospital (Code: 1866). All the participants and their families were informed about the study and voluntarily agreed to participate. For every child, informed consent from their parents or legal guardian was obtained. All measurements and data collection were carried out across the school year (from September to June).

A convenience sample was selected from a large group. First, 20 boys of the same age and gender were chosen to form a basketball team (group B), in accordance with federal recommendations, and their training sessions were monitored by a highly qualified basketball trainer. Of these 20 participants, 3 withdrew from the study due to lack of availability to continue. Second, a cohort of 74 boys from a school was selected to form a control group (group C), starting from the same baseline as the intervention group. The control group only granted permission for a single visit.

Intervention

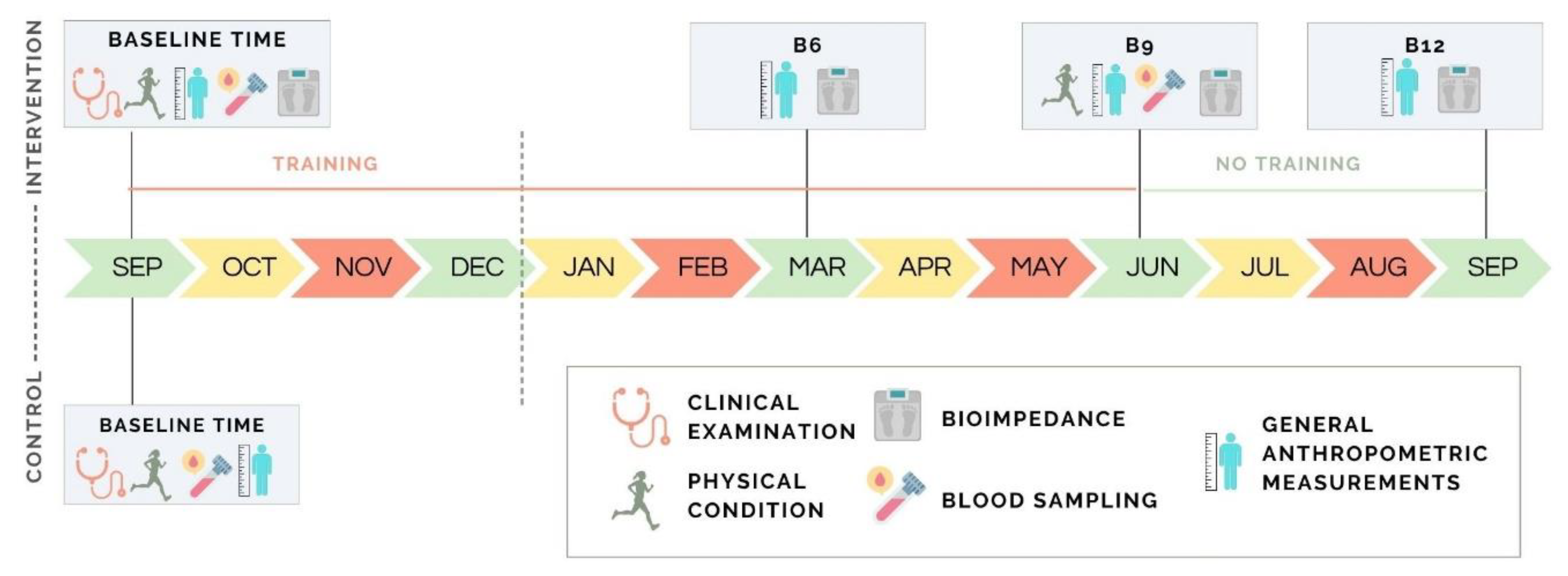

The intervention basketball program training supervised by a qualified trainer was divided into two periods: a pre-season period at the beginning of the school year during the first 6 weeks, and immediately afterward, a season for 32 weeks (until the end of the school year). After that, recommendations to be active were done for summer holidays and 3 months after the intervention end, a follow-up visit was carried out.

The pre-season included 5 training sessions (Monday to Friday) per week of 2 hours each one. This intervention was focused on dribbling, defending and shooting skills. The season included 3 training sessions per week of 2 hours each one (after school) and a match during the weekend. Each session was divided into 2 periods separated by a break of 10 minutes: the first period focused on individual skills with moderate- to high-intensity (60-85% of heart rate (HR)) exercises, and the second period focused on game tactics and strategy.

Outcomes

At baseline (B

0), clinical examination, body composition, physical fitness tests, BP and blood draws to assess biochemical parameters related to metabolism and cardiovascular health were carried out in all boys included in the study. Follow-up visits were conducted at 6 months (B

6), 9 months (B

9), and 12 months (B

12) to repeat anthropometric and other measurements, with no training sessions between B

9 and B

12 (

Figure 1). All measurements were performed under the same conditions: after emptying the bladder, three hours after rising and eating, and without previous hard exercise.

Clinical examination

A comprehensive clinical evaluation was performed by trained healthcare professionals, including a structured anamnesis to collect medical and family history (particularly regarding metabolic or cardiovascular diseases), current health status, and medication use. Sexual maturity was assessed following Tanner’s five-stage scale [

12], through a physical examination conducted in a private setting by a paediatric. In boys, this included evaluation of genital development and pubic hair distribution.

Body Composition

Body weight and height were measured using standard techniques, a beam balance and a precision stadiometer SECA 213 (Scale 20–205 cm; SECA), with the participants lightly dressed and barefoot. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/ height (m

2) and compared to growth charts for Spanish children [

13]. Body composition components such as fat-free mass and fat mass were obtained by bioelectrical impedance analysis using a Tanita BC 418 MA Segmental Body Composition Analyser® (Tokyo, Japan).

Blood pressure

Systolic and diastolic BP and heart rate (HR) were measured in the right arm in a sitting position, using a random-zero sphygmomanometer (Dinamap V-100) after the subjects had rested without changing position for at least 5 minutes.

Blood sampling

Fasting blood samples were collected and analysed for hematimetry, glucose, insulin, lipids, and HOMA-IR. Full procedures are provided (Supplementary Material 2).

Evaluation of cardiorespiratory fitness (Course Navette test)

The Course Navette test was employed to evaluate cardiorespiratory fitness. Participants were required to run for the maximum possible time in a continuous 20-meter shuttle run at a progressively increasing speed [

14].

Lower body explosive strength (horizontal jump test)

Lower body muscular strength is evaluated through the horizontal jump test [

15]. Participants performed three maximal jumps with feet together; the longest was recorded. A take-off mark ensured correct foot placement and prevented invalid attempts.

Core strength (Abdominal test)

Core strength was assessed with a 30-second sit-up test. From a supine position, participants performed as many correct sit-ups as possible, touching elbows to thighs and returning shoulders to the mat. A trained evaluator supervised and gave standardized instructions.

Sample Size

As the horizontal jump is one of the main outcomes for this study, the sample size was determined by calculating the statistical power based on previous study [

16], together with a similar male population, with a power of 0.80 and a 2-tailed α level set to 0.05; the minimum number of participants required to detect an 8% difference in horizontal jump performance was estimated 17.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of variables. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. To compare physical fitness variables, anthropometric variables and biochemical parameters at different times in the intervention group, ANOVA test was used, while to compare the control group with the different times of the intervention group T-student was used. The study employed the Pearson correlation coefficient to examine the bivariate correlations among the variables. Correlations models were fitted to assess associations between physical fitness variables, anthropometric variables, and biochemical parameters at different times. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS statistics 25 (IBM Corp., 2017). In all analyses statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed P value <.05.

3. Results

A total of 91 children participated in the study: 74 in the control group (C) and 20 in the intervention group (B), of whom 17 completed the study7 (

Table 1). Both groups (C) - (B

0) exhibited differences in baseline anthropometric measurements; no significant differences observed between groups (C) - (B

0) at baseline in weight, height, weight percentile, height percentile, BMI, and BMI z-scores. However, there was an increase in weight and height from B

0 to B

12 in trained boys. Additionally, lower levels in both systolic and diastolic BP was noted in B

0 compared to group C and maintained during training.

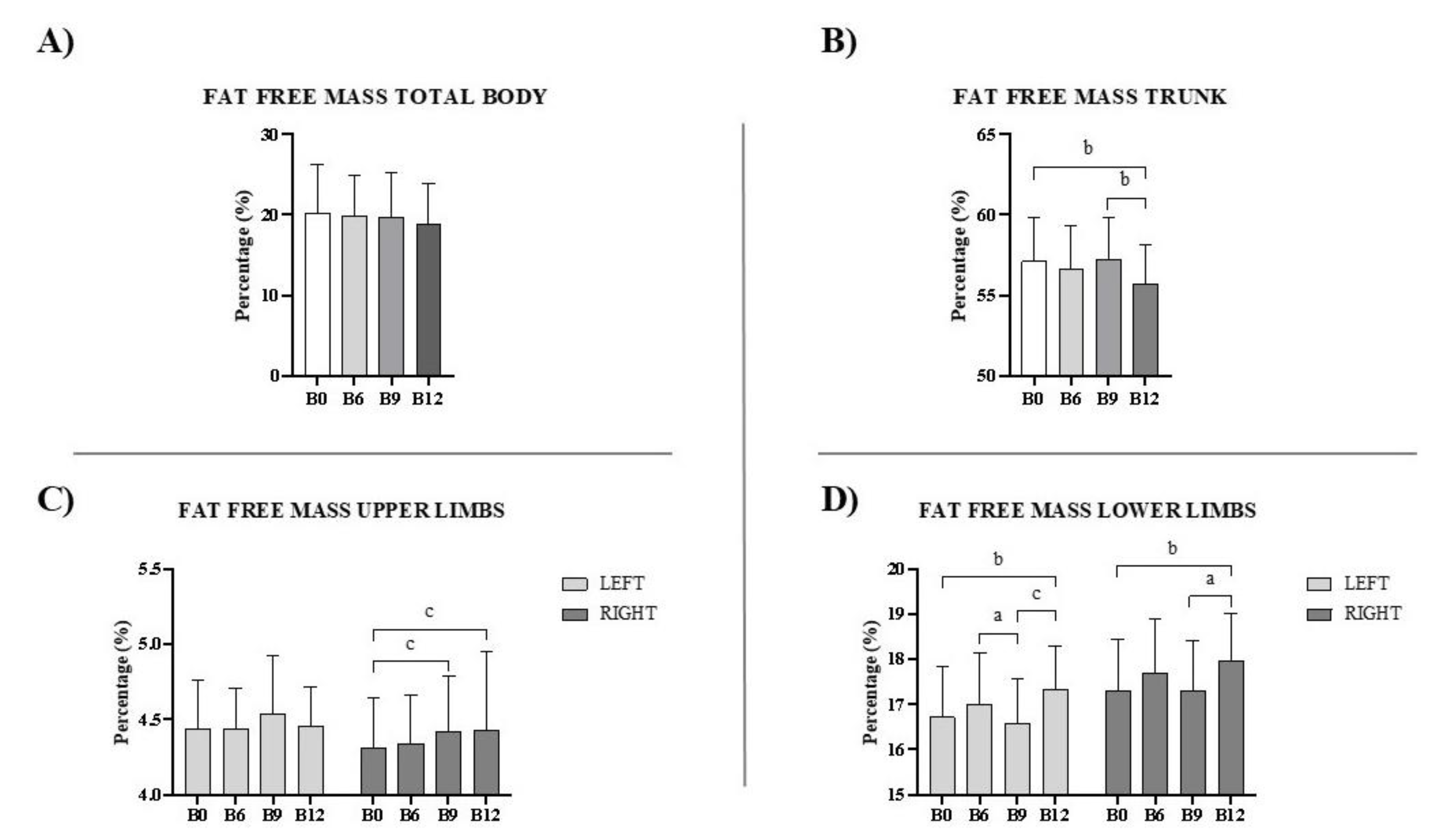

Significant differences in fat free mass were observed in several body regions in boys trained in the different times of measurements without differences in total fat free mass (

Figure 2A). Specially,

in the trunk, a reduction in fat free mass was found in B12 compared to B9 and B0 (

Figure 2B). In upper limbs no significant differences were found except an increase in B

9 and B

12 respect to baseline time in right limb (

Figure 2C). Lower limbs showed an increase of fat free mass from basal time to the end of the study at B

12 (

Figure 2D).

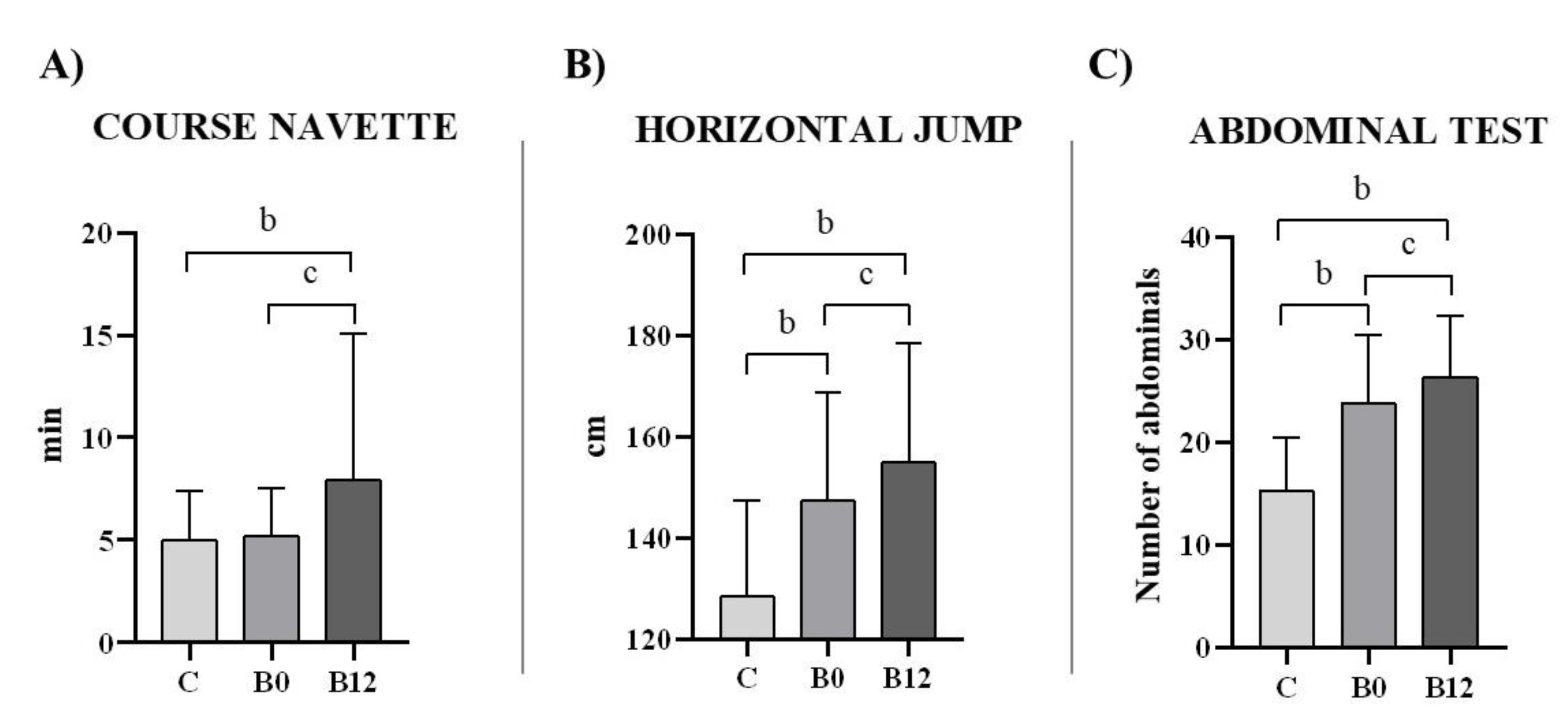

The group of basketball training showed better results in jump and abdominal tests than control group at basal time without differences in Course-Navette test. After the intervention at B

12, boys improved their results in all these tests compared with their data at basal time B

0 (p<0.001) (

Figure 3).

Blood parameters were within the normal range compared with reference values from the laboratory, indicating that all the children exhibited a state of good health at baseline (for both groups). It was maintained in the follow-up after the intervention (B

12) in the trained group (

Table 2).

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA test was used to compare variables among the different groups; No matching superscript letters (a, b, c, d) indicate significant differences (p<0.05) by two-way ANOVA and Wilcoxon tests, depending on variables following or not a normal distribution, with repeated measures.

The Course Navette test was negatively correlated with BMI z-score at baseline (r = –0.521, p = 0.046), and this association became stronger at B12 (r = –0.738, p = 0.010), indicating that higher aerobic fitness was linked to lower BMI z-scores. At B12 follow-up, the Course Navette test also showed a significant inverse correlation with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (r = –0.714, p = 0.009). In addition, in B12 follow-up, both horizontal jump performance (r = –0.651, p = 0.022) and abdominal test performance (r = –0.659, p = 0.020) were negatively associated with CRP.

4. Discussion

An afterschool program of basketball training during the scholar year, seems to improve the body composition and physical fitness in a group of prepuberal boys compared with a similar group without this intervention.

The limited literature on anthropometric and performance changes in preadolescent basketball players underscores the need to further explore the benefits of this sport during this key developmental stage. Some limitations in evaluating the effects of basketball training are associated with small teams with a controlled number of participants [

17] or teams solely comprised of individuals of a single sex [

18]. However, in this study, comparison with a control group at baseline ensured that all participants began from similar conditions with comparable health statuses prior to training. Furthermore, the intervention was conducted by expert trainers specifically with this group of prepubertal boys, preparing them to compete in real conditions against similar counterparts.

Previous studies [

19,

20,

21] have consistently demonstrated a general increase in all anthropometric traits during the training period in children who practice basketball, coupled with a decrease in fat mass. This reduction in fat mass has been attributed to both the rapid growth of fat free mass and a slower accumulation of fat. Excessive fat mass not only hampers mobility in sports but also adversely affects physical performance [

22]. Decreasing body fat reduces strain on both the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems, thereby enhancing movement efficiency and the capacity for physical exercise, resulting in improvements in strength, endurance, and overall functional capability [

23]. In the children participating in this study, a decrease in BMI z-score and fat mass was observed, while maintaining normoweight values, along with an improvement in Course Navette test. These findings are consistent with results from another study conducted on children of similar ages, where participants with higher BMI achieved inferior results in fitness tests [

24].

Basketball emerges as an excellent candidate for enhancing body composition and bone mineral density due to its high-impact nature (Collado-Castro et al. 2025). Sports like basketball are characterized by their impact and require actions such as jumping, similar to volleyball [

25], handball [

26] or dance [

27]. On the other hand, full-body sports such as swimming involve both the upper and lower limbs but lack impact on the body, as it occurs in a microgravity environment where the body does not experience any impact forces [

28]. In our study, a general improvement in fat free mass was observed in both the lower and upper limbs throughout the training period. Unlike many sports, such as football, where one leg often predominates, in basketball, both the left and right lower limbs are used equally, resulting in similar fat free mass development. This equal involvement of both sides of the body during training contributes to the balanced development of fat free mass [

29]. Additionally, engaging in comprehensive sports that involve both lower and upper body training has been associated with a decrease in fat mass and an increase in fitness levels among prepubertal and early pubescent children [

30].

The Course-Navette test is a widely used tool to assess physical fitness, providing valuable information on maximal effort and aerobic capacity [

31]. It also reflects cardiovascular and respiratory health through its estimation of maximal oxygen consumption [

32]. Children and adolescents involved in organized sports tend to show better physical fitness and a lower risk of overweight or obesity [

33].This improvement is attributed to their commitment to an active lifestyle, characterized by regular levels of PA. The systematic practice of sports also promotes cardiovascular health, which is further associated with anthropometric improvements [

34]. In the present study, there are interesting inverse correlations, specially at the end of the intervention between fitness and weight and BMI z-score, and with CRP, a classic biomarker of inflammation.

The frequency of sport practice has been closely linked to improvements in fitness [

35]. In a study involving 19 basketball players in training sessions conducted twice a week for 8 weeks resulted in enhanced cardiorespiratory fitness, explosive strength and core strength [

33]. Similarly, in another study focusing on prepubertal children who trained three times a week for 12 weeks, improvements were observed in anaerobic capacity, endurance running, and overall strength [

30]. Thus, training twice a week emerges as a viable option to achieve health benefits with enhancements in jumping and running performances, along with an increase in fat free mass, as previously reported [

24]. Furthermore, higher performance in horizontal jumps has been linked to improved sprints and agility in male adolescent basketball players [

36].

It is also evident that participants in the intervention group demonstrate superior performance compared to those in the control group right from the baseline, particularly in the abdominal and horizontal jump tests. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that individuals in the intervention group were generally more active and inclined to participate in sports activities compared to those in the control group.

Both groups showed normal baseline biochemical values, which were maintained post-training in the basketball group. While high-intensity exercise may induce low-grade inflammation [

37], regular, controlled training improves fitness and body composition without altering metabolic biomarkers. Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and lipid profiles, especially in at-risk individuals [

38]. Basketball, in particular, benefits multiple systems and supports disease prevention during youth [

37]. However, these benefits decline after ~12 weeks of inactivity, with reductions in lean mass evident within three months (B12).

Practical implications

Maintaining regular physical activity is essential to avoid sedentary behaviors that can increase disease risk. This study supports basketball as an effective strategy to promote fitness and healthy body composition during childhood, suggesting its potential as a preventive tool against obesity. These findings could inform recommendations in pediatric healthcare settings, particularly for children at risk of excess adiposity or low fitness levels. Future policies might consider structured afterschool sports programs as part of preventive health strategies in youth populations.

Limitations

This study was limited to prepubertal boys, which may reduce generalizability to girls or older adolescents. The intervention was conducted in a single setting with a relatively small sample size, and participation was voluntary, potentially introducing selection bias. Future studies should include longitudinal follow-ups to assess sustained effects and explore differences by sex, maturation stage, and training modalities.

5. Conclusions

This basketball training program in prepubertal boys conducted three days a week with a weekend match over a period of 32 weeks, with a moderate to vigorous intensity, leads to significant improvements in physical fitness and body composition outcomes contributing to improve the health status.

Author Contributions

Study design, FJ.L.C., M.G.C.; Data collection and management, FJ.L.C., M.G.C., C.C.C., G.Q.N.; Statistical analysis, FJ.L.C., M.G.C., C.C.C., G.Q.N.; Interpretation of the results, C.C.C., JM.J-C., M.G.C., G.Q.N., FJ.L.C.; Drafting, C.C.C., JM.J-C., M.G.C., G.Q.N., FJ.L.C. All authors critically reviewed the content of the manuscript and provided substantial feedback. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was designed following the ethical principles for human research of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the local ethics and research committee in the University Reina Sofia Hospital (Code: 1866).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children and their parents for their participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabiri LS, Rodriguez AX, Perkins-Ball AM, et al. Organized Sports and Physical Activities as Sole Influencers of Fitness: The Homeschool Population. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

- Chang SH, Kim K. A review of factors limiting physical activity among young children from low-income families. J Exerc Rehabil. 2017, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stea TH, Solaas SA, Kleppang AL. Association between physical activity, sedentary time, participation in organized activities, social support, sleep problems and mental distress among adults in Southern Norway: a cross-sectional study among 28,047 adults from the general population. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira DV, Branco BHM, de Jesus MC, et al. [Relationship between vigorous physical activity and body composition in older adults]. Nutr Hosp. 2021, 38, 60–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyriax BC, Windler E. Lifestyle changes to prevent cardio- and cerebrovascular disease at midlife: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2023, 167, 60–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thivel D, Ring-Dimitriou S, Weghuber D, et al. Muscle Strength and Fitness in Pediatric Obesity: a Systematic Review from the European Childhood Obesity Group. Obes Facts. 2016, 9, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oja P, Titze S, Kokko S, et al. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015, 49, 434–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang D, Xu G. Effects of chains squat training with different chain load ratio on the explosive strength of young basketball players’ lower limbs. Front Physiol. 2022, 13, 979367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai CL, Ju J, Chen Z. The mediating role of prosocial and antisocial behaviors between team trust and sport commitment in college basketball players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 1418–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama T, Rikukawa A, Nagano Y, et al. Acceleration Profile of High-Intensity Movements in Basketball Games. J Strength Cond Res. 2022, 36, 1715–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen MN, Madsen M, Nielsen CM, et al. Cardiovascular adaptations after 10 months of daily 12-min bouts of intense school-based physical training for 8-10-year-old children. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020, 63, 813–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Marubini E, et al. The adolescent growth spurt of boys and girls of the Harpenden growth study. Ann Hum Biol. 1976, 3, 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobradillo B, Aguirre A, Aresti U, et al. Curvas y tablas de crecimiento. Estudios longitudinal y transversal. 2004.

- Ruiz JR, Castro-Piñero J, España-Romero V, et al. Field-based fitness assessment in young people: the ALPHA health-related fitness test battery for children and adolescents. Br J Sports Med. 2011, 45, 518–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas-Sanchez C, Martinez-Tellez B, Sanchez-Delgado G, et al. Assessing physical fitness in preschool children: Feasibility, reliability and practical recommendations for the PREFIT battery. J Sci Med Sport. 2016, 19, 910–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengizel E, Cengizel ÇÖ, Öz E. Effects of 4-Month Basketball Training on Speed, Agility and Jumping in Youth Basketball Players. African Educational Research Journal. 2020, 8, 417–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Muñoz I, Ramírez-Campillo R, Azocar-Gallardo J, et al. Effects of Progressed and Nonprogressed Volume-Based Overload Plyometric Training on Components of Physical Fitness and Body Composition Variables in Youth Male Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2021, 35, 1642–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Díaz S, Yanci J, Raya-González J, et al. A Comparison in Physical Fitness Attributes, Physical Activity Behaviors, Nutritional Habits, and Nutritional Knowledge Between Elite Male and Female Youth Basketball Players. Front Psychol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Malina RM, Eisenmann JC, Cumming SP, et al. Maturity-associated variation in the growth and functional capacities of youth football (soccer) players 13-15 years. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004, 91, 555–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldo N, Toselli S, Gualdi-Russo E, et al. Effects of Anthropometric Growth and Basketball Experience on Physical Performance in Pre-Adolescent Male Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Temfemo A, Hugues J, Chardon K, et al. Relationship between vertical jumping performance and anthropometric characteristics during growth in boys and girls. Eur J Pediatr. 2009, 168, 457–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero-Cristóbal R, Albaladejo-Saura M, Luna-Badachi AE, et al. Differences in Fat Mass Estimation Formulas in Physically Active Adult Population and Relationship with Sums of Skinfolds. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermassi S, van den Tillaar R, Bragazzi NL, et al. The Associations Between Physical Performance and Anthropometric Characteristics in Obese and Non-obese Schoolchild Handball Players. Front Physiol. 2021, 11, 580991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis PT, Asadi A, Santos EJAM, et al. Relationship of body mass status with running and jumping performances in young basketball players. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015, 5, 187–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka H, Tabata H, Shi H, et al. Playing basketball and volleyball during adolescence is associated with higher bone mineral density in old age: the Bunkyo Health Study. Front Physiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Pereira R, Krustrup P, Castagna C, et al. Effects of recreational team handball on bone health, postural balance and body composition in inactive postmenopausal women - A randomised controlled trial. Bone. 2021, 145. [CrossRef]

- Yang LC, Lan Y, Hu J, et al. Relatively high bone mineral density in Chinese adolescent dancers despite lower energy intake and menstrual disorder. Biomed Environ Sci. 2010, 23, 130–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Bruton A, Montero-Marín J, González-Agüero A, et al. The Effect of Swimming During Childhood and Adolescence on Bone Mineral Density: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoli A, Gentil P, Moro T, et al. Resistance Training with Single vs. Multi-joint Exercises at Equal Total Load Volume: Effects on Body Composition, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Muscle Strength. Front Physiol. 2017, 8, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingle L, Sleap M, Tolfrey K. The effect of a complex training and detraining programme on selected strength and power variables in early pubertal boys. J Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 987–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Vélez R, Silva-Moreno C, Correa-Bautista JE, et al. Self-Rated Health Status and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in a Sample of Schoolchildren from Bogotá, Colombia. The FUPRECOL Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lamoneda J, Huertas-Delgado FJ, Cadenas-Sanchez C. Feasibility and concurrent validity of a cardiorespiratory fitness test based on the adaptation of the original 20 m shuttle run: The 20 m shuttle run with music. J Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romarate A, Yanci J, Iturricastillo A. Evolution of the internal load and physical condition of wheelchair basketball players during the competitive season. Front Physiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaoutis G, Georgoulis M, Psarra G, et al. Association of Anthropometric and Lifestyle Parameters with Fitness Levels in Greek Schoolchildren: Results from the EYZHN Program. Front Nutr. 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- Högström G, Nordström A, Nordström P. High aerobic fitness in late adolescence is associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction later in life: a nationwide cohort study in men. Eur Heart J. 2014, 35, 3133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamuk Ö, Makaracı Y, Ceylan L, et al. Associations between Force-Time Related Single-Leg Counter Movement Jump Variables, Agility, and Linear Sprint in Competitive Youth Male Basketball Players. Children (Basel). 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- DiFiori JP, Güllich A, Brenner JS, et al. The NBA and Youth Basketball: Recommendations for Promoting a Healthy and Positive Experience. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2053–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler MJ, Green DJ, Cerin E, et al. Combined effects of continuous exercise and intermittent active interruptions to prolonged sitting on postprandial glucose, insulin, and triglycerides in adults with obesity: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).