Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Maintenance and Experimental Design

2.2. Sampling Protocols

2.3. Growth Performance and Somatic Indices

- -

- (K) = (100 × body mass)/fork length3

- -

- Mass gain (MG) = (100 × body mass increase)/initial body mass

- -

- Specific growth rate (SGR) = (100 × (ln final body mass - ln initial body mass))/days

- -

- Feed efficiency (FE) = mass gain/total feed intake

- -

- Hepatosomatic index (HSI) = (100 × liver mass)/fish mass

- -

- Viscerosomatic index (VSI) = (100 × gut mass)/fish mass

- -

- Intestine length index (ILI) = (100 × intestine length)/fork body length

2.4. Plasma and Tissue Parameters

2.4. Intestinal Lipase Activity

2.5. Fatty Acid Analysis

2.6. Gene Expression

2.6.1. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.6.2. Real-Time PCR

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Parameters and Somatic Indices

3.2. Plasma and Tissue Biochemistry Results

3.3. Intestinal Lipase Activity

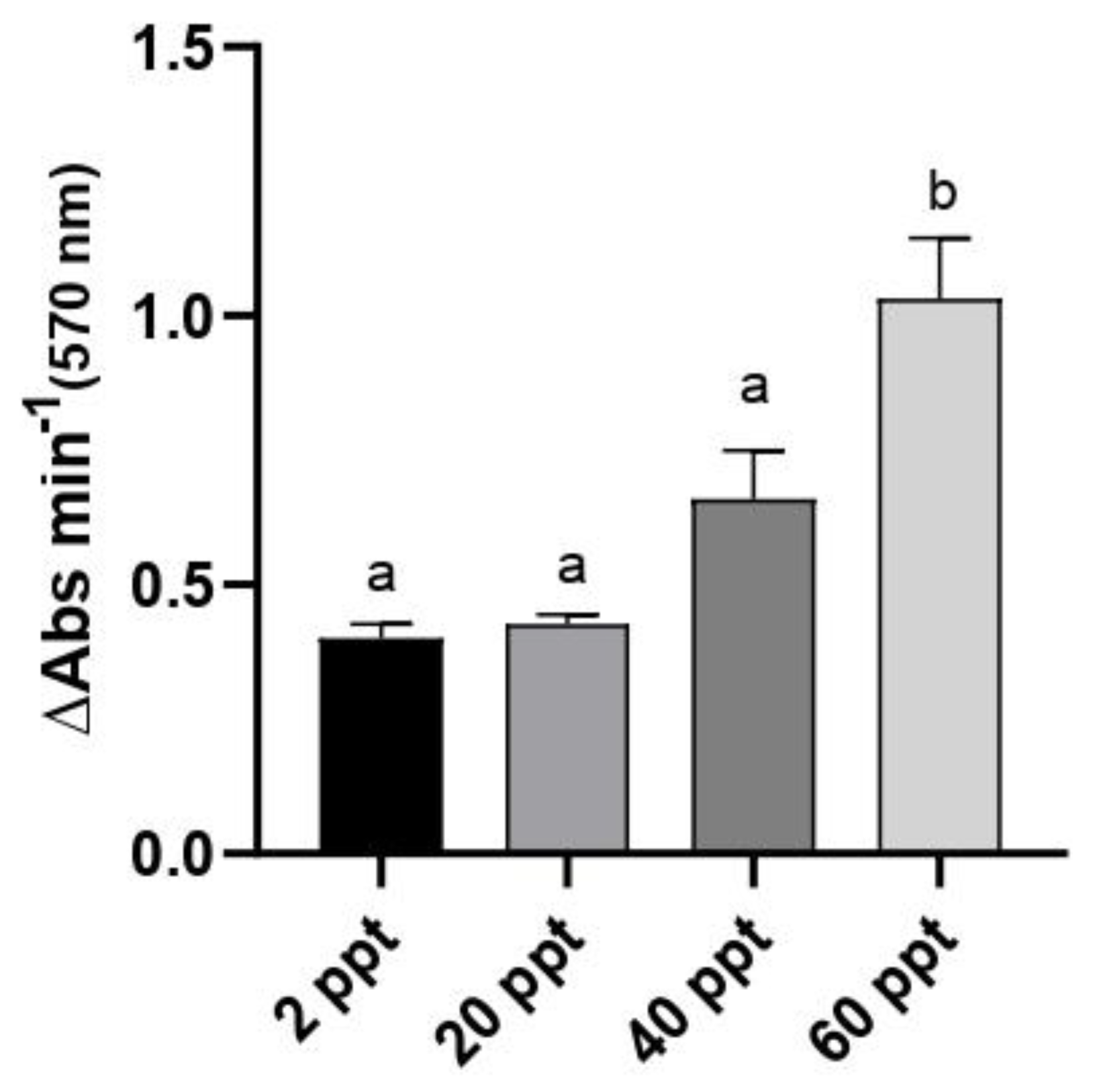

3.4. Fatty Acid Composition

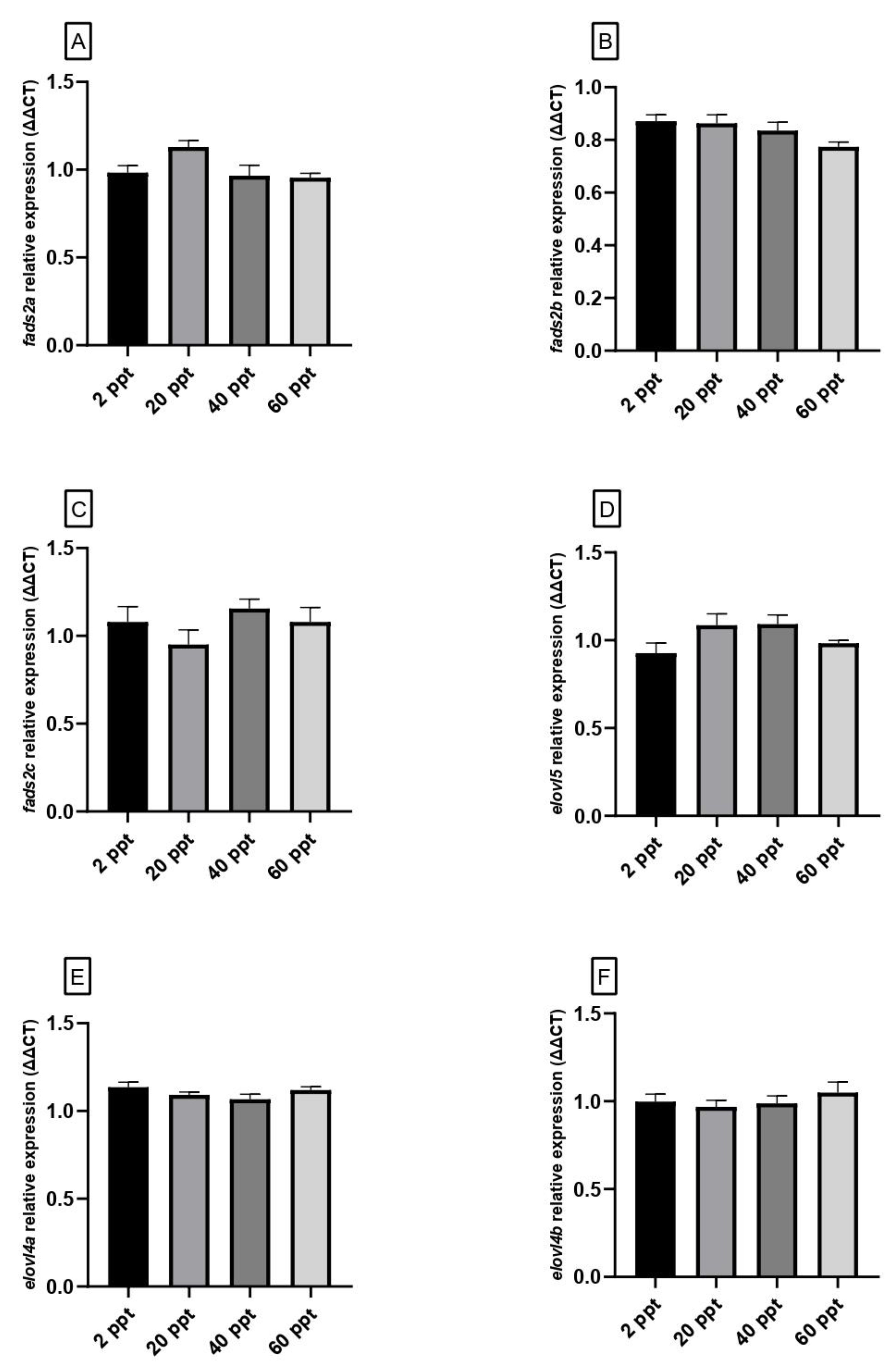

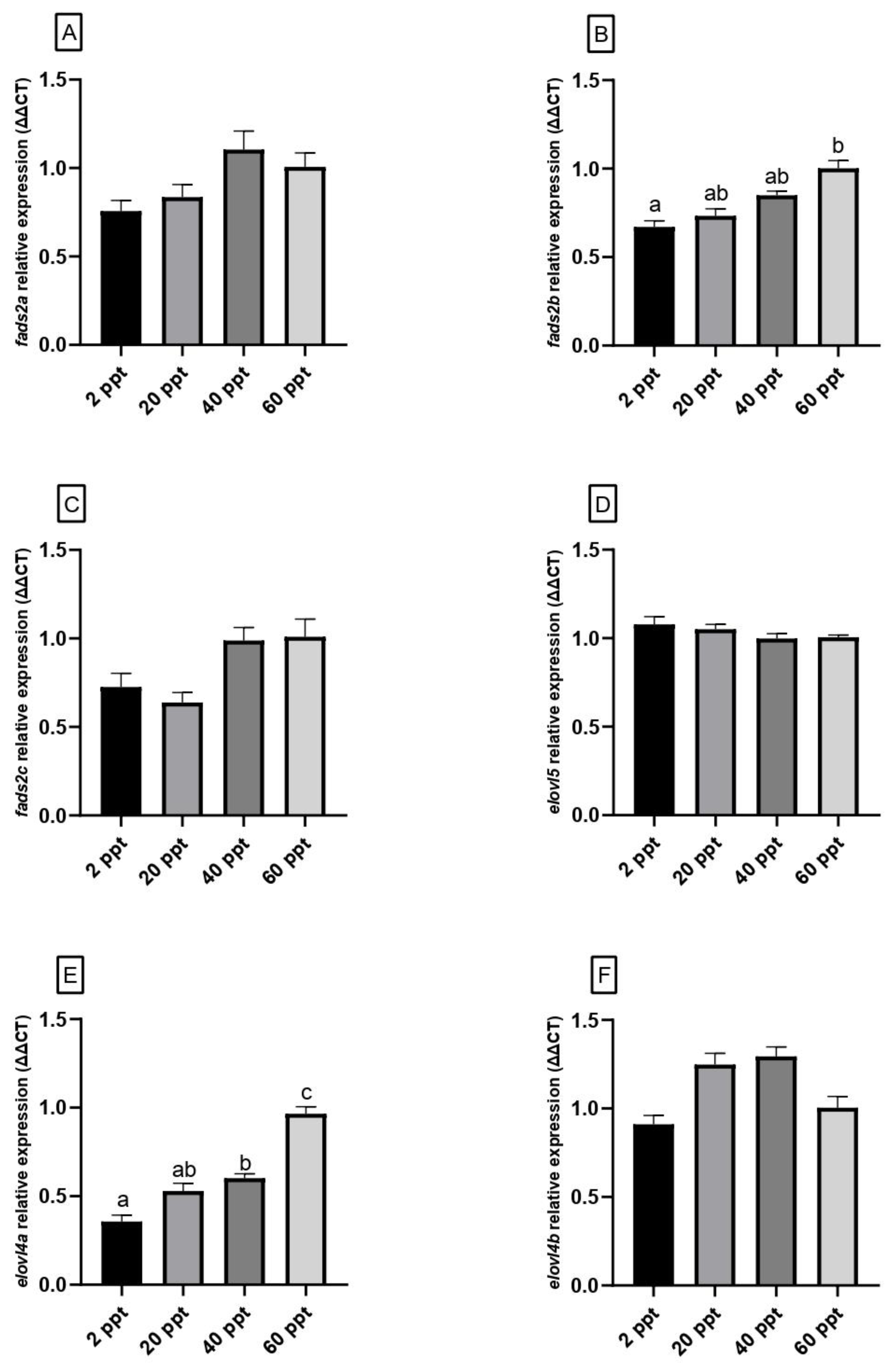

3.5. Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, T. G.; Kültz, D. The cellular stress response in fish exposed to salinity fluctuations. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology 2020, 333(6), 421-435.

- Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Lu, Z.; Xu, L.; Ji, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J. Metabolite and gene expression responses in juvenile flounder Paralichthys olivaceus exposed to reduced salinities. Fish Shellfish Immunology 2017, 63, 417-423. [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Erik, J.; Meryem, B.; Korhan, Ö.; Zuhal, A. Salinization increase due to climate change will have substantial negative effects on inland waters: a call for multifaceted research at the local and global scale. The Innovation 2020, 1(2), 100030.

- Maulu, S.; Hasimuna, O.J.; Haambiya, L.H.; Monde, C.; Musuka, C.G.; Makorwa, T.H.; Munganga, B.P.; Phiri, K.J.; Nsekanabo, J.D. Climate change effects on aquaculture production: sustainability implications, mitigation, and adaptations. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 609097. [CrossRef]

- Telesh, I.V.; Khlebovich, V.V. Principal processes within the estuarine salinity gradient: a review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2010, 61(4-6), 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Wetz, M.S.; Yoskowitz, D.W. An ‘extreme’future for estuaries? Effects of extreme climatic events on estuarine water quality and ecology. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2013, 69(1-2), 7-18. [CrossRef]

- González, R.J. The physiology of hyper-salinity tolerance in teleost fish: a review. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 2012, 182, 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Kültz, D. Physiological mechanisms used by fish to cope with salinity stress. The Journal of Experimental Biology 2015, 218(12), 1907-1914. [CrossRef]

- Barany, A.; Gilannejad, N.; Alameda-López, M.; Rodríguez-Velásquez, L.; Astola, A.; Martínez-Rodríguez, G.; Roo, J.; Muñoz, J.L.; Mancera, J.M. Osmoregulatory plasticity of juvenile greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) to environmental salinity. Animals 2021, 11(9), 2607. [CrossRef]

- Seale, A.P.; Breves, J.P. Endocrine and osmoregulatory responses to tidally-changing salinities in fishes. General and Comparative Endocrinology 2022, 326, 114071. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cai, B.; Tian, C.; Jiang, D.; Shi, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Li, G.; Deng, S. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis reveals liver lipid metabolism divergent adaptive response to low-and high-salinity stress in spotted scat (Scatophagus argus). Animals 2023, 13(9), 1503. [CrossRef]

- Bœuf, G.; Payan, P. How should salinity influence fish growth?. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2001, 130(4), 411-423.

- Soengas, J.L.; Sangiao-Alvarellos, S.; Laiz-Carrión, R.; Mancera, J.M. Energy metabolism and osmotic acclimation in teleost fish. In Fish osmoregulation; Baldisserotto, B., Mancera, J.M., Kapoor, B.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 277-307.

- Gregorio, S.F.; Carvalho, E.S.M.; Encarnacao, S.; Wilson, J.M.; Power, D.M.; Canario, A.V.M.; Fuentes, J. Adaptation to different salinities exposes functional specialization in the intestine of the sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). The Journal of Experimental Biology 2012, 216(3), 470-479. [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Gregório, S.F.; Egger, R.C.; Fuentes, J. Molecular and functional regionalization of bicarbonate secretion cascade in the intestine of the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2019, 233, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E. H.; Deaton, L. E.; Onken, H.; O’Donnell, M.; Grosell, M.; Dantzler, W.H.; Weihrauch, D. Osmoregulation and excretion. Comprehensive Physioly 2011, 4, 405-573. [CrossRef]

- Sargent, J.; McEvoy, L.; Estevez, A.; Bell, G.; Bell, M.; Henderson, J.; Tocher, D. Lipid nutrition of marine fish during early development: current status and future directions. Aquaculture 1999, 179 (1-4), 217-229. [CrossRef]

- Monroig, Ó.; Tocher, D.R.; Castro, L.F.C. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Biosynthesis and Metabolism in Fish. In Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Metabolism; Burdge, G.C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 31-60.

- Frallicciardi, J.; Melcr, J.; Siginou, P.; Marrink, S.J.; Poolman, B. Membrane thickness, lipid phase and sterol type are determining factors in the permeability of membranes to small solutes. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 1605. [CrossRef]

- Hamre, K.; Yúfera, M.; Rønnestad, I.; Boglione, C.; Conceição, L.E.; Izquierdo, M. Fish larval nutrition and feed formulation: knowledge gaps and bottlenecks for advances in larval rearing. Reviews in Aquaculture. 2013, 5, S26-S58. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Dong, S.; Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Ma, S.; Zhou, Y. Growth, osmoregulatory response, adenine nucleotide contents, and liver transcriptome analysis of steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) under different salinity acclimation methods. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734937. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-López, E.; Panzera, Y.; Bessonart, M.; Marandino, A.; Féola, F.; Gadea, J.; Magnone, L.; Salhi, M. Effect of salinity on fads2 and elovl gene expression and fatty acid profile of the euryhaline flatfish Paralichthys orbignyanus. Aquaculture 2024, 583, 740585. [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.-P.; Dong, S.-L.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q.-F.; Sun, D.-J. RNA-seq reveals temporal differences in the transcriptome response to acute heat stress in the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics 2019, 30, 169-178. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, H.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. RNA-Seq analysis of salinity stress–responsive transcriptome in the liver of spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus). PLoS One 2017, 12, e0173238. [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.V.; Tocher, D.R. Molecular species composition of the major phospholipids in brain and retina from rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Occurrence of high levels of di-(n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid species. Biochemical Journal. 1989, 264 (3), 909-915.

- Bell, M.V.; Batty, R.S.; Dick, J.R.; Fretwell, K.; Navarro, J.C.; Sargent, J.R. Dietary deficiency of docosahexaenoic acid impairs vision at low light intensities in juvenile herring (Clupea harengus L.). Lipids 1995, 30 (5), 443-449. [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: A review of the independent and shared effects of EPA. DPA and DHA. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2015, 7, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Gawrisch, K.; Eldho, N.V.; Holte, L.L. The structure of DHA in phospholipid membranes. Lipids 2003, 38 (4), 445-452. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.; Luo, Y.; Shen, H. Lipid content and fatty acid profile of muscle, brain and eyes of seven freshwater fish: a comparative study. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2014, 91(5), 795-804. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, W.S.; Emberley, T.R.; Singer, T.D.; Bryson, S.E.; McCormick, S.D. Time course of salinity adaptation in a strongly euryhaline estuarine teleost, Fundulus heteroclitus: a multivariable approach. Journal of Experimental Biology 1999, 202(11), 1535-1544. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, W.S.; Bryson, S.E. Transport mechanisms of seawater teleost chloride cells: an inclusive model of a multifunctional cell. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 1998, 119(1), 97-106. [CrossRef]

- Martos-Sitcha, J.A., Martínez-Rodríguez, G.; Mancera, J.M.; Fuentes, J. AVT and IT regulate ion transport across the opercular epithelium of killifish (F. heteroclitus) and gilthead sea bream (S. aurata). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2015, 182, 93-101.

- Wood, C.M.; Marshall, W.S. Ion balance, acid-base regulation, and chloride cell function in the common killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus, a euryhaline estuarine teleost. Estuaries 1994, 17, 34-52. [CrossRef]

- Genz, J.; Grosell, M. Fundulus heteroclitus acutely transferred from seawater to high salinity require few adjustments to intestinal transport associated with osmoregulation. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2011, 160(2), 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Kidder III, G.W.; Petersen, C.W.; Preston, R.L. Energetics of osmoregulation: Water flux and osmoregulatory work in the euryhaline fish, Fundulus heteroclitus. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Comparative Experimental Biology 2006, 305(4), 318-327.

- Matsushita, Y.; Miyoshi, K.; Kabeya, N.; Sanada, S.; Yazawa, R.; Haga, Y.; Satoh, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Strüssmann, C.A.; Luckenbach, J.A.; Yoshizaki, G. Flatfishes colonised freshwater environments by acquisition of various DHA biosynthetic pathways. Communications Biology 2020, 3, 4-5. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Navarro, J.C.; Varó, I.; Monroig, Ó.; Hontoria, F. Nutritional regulation of genes responsible for long-chain (C20-24) and very long-chain (> C24) polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in post-larvae of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). Aquaculture 2020a, 525, 735314. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Navarro, J.C.; Varó, I.; Agulleiro, M.J.; Morais, S.; Monroig, Ó.; Hontoria, F. Expression of genes related to long-chain (C18-22) and very long-chain (> C24) fatty acid biosynthesis in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) larvae: Investigating early ontogeny and nutritional regulation. Aquaculture 2020b, 520, 734949. [CrossRef]

- Lugert, V.; Thaller, G.; Tetens, J.; Schulz, C.; Krieter, J. A review on fish growth calculation: multiple functions in fish production and their specific application. Reviews in Aquaculture 2016, 8, 30-42. [CrossRef]

- García-Márquez, J.; Domínguez-Maqueda, M.; Torres, M.; Cerezo, I.M.; Ramos, E.; Alarcón, F.J.; Mancera, J.M.; Martos-Sitcha, J.A.; Moriñigo, M.A.; Balebona, M.C. Potential Effects of microalgae-supplemented diets on the growth, blood parameters, and the activity of the intestinal microbiota in Sparus aurata and Mugil cephalus. Fishes 2023, 8(8), 409.

- Molina-Roque, L.; Bárany, A.; Sáez, M.I.; Alarcón, F.J.; Tapia, S.T.; Fuentes, J.; Mancera, J.M.; Perera, E.; Martos-Sitcha, J.A. Biotechnological treatment of microalgae enhances growth performance, hepatic carbohydrate metabolism and intestinal physiology in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) juveniles close to commercial size. Aquaculture Reports 2022, 25, 101248. [CrossRef]

- Keppler, D.; Decker, K. Glycogen. Determination with Amyloglucosidase. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis 1974, 3, 1127-1131.

- O’Fallon, J.V.; Busboom, J.R.; Nelson, M.L.; Gaskins, C.T. A direct method for fatty acid methyl ester synthesis: Application to wet meat tissues, oils, and feedstuffs. Journal of animal science 2007, 85(6), 1511-1521. [CrossRef]

- Garrido, D.; Navarro, J.C.; Perales-Raya, C.; Nande, M.; Martín, M.V.; Iglesias, J.; Bartolomé, A.; Roura, A.; Varó, I.; Otero, J.J.; González, F.; Rodríguez, C.; Almansa, E. Fatty acid composition and age estimation of wild Octopus vulgaris paralarvae. Aquaculture 2016, 464, 564-569. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-DDCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402-408.

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research 2001, 29, e45. [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biology 2002, 3, 1-12.

- Vargas-Chacoff, L.; Saavedra, E.; Oyarzún, R.; Martínez-Montaño, E.; Pontigo, J.P.; Yáñez, A.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Mancera, J.M.; Bertrán, C. Effects on the metabolism, growth, digestive capacity and osmoregulation of juvenile of Sub-Antarctic Notothenioid fish Eleginops maclovinus acclimated at different salinities. Fish physiology and biochemistry 2015, 41, 1369-1381. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, R.W. Environment and salinity tolerance in the genus Fundulus. Copeia 1974, 2, 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Yetsko, K.; Sancho, G. The effects of salinity on swimming performance of two estuarine fishes, Fundulus heteroclitus and Fundulus majalis. Journal of Fish Biology 2015, 86(2), 827-833. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.; Zhang, S.; Roach, J.L.; Galvez, F. Common functional targets of adaptive micro- and macro-evolutionary divergence in killifish. Molecular Ecology 2013, 22, 3780-3796. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, E.B.; Saksena, V.P. Determination of salinity tolerances in mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus) larvae obtained from hormone-induced spawning. Chesapeake Science 1966, 7(4), 193-197. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.S. Salinity affects growth but not thermal preference of adult mummichogs Fundulus heteroclitus. Journal of Fish Biology 2019, 95(4), 1107-1115. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. D. Energetic aspects of osmoregulation in fish. Doctoral Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 1998.

- Mancera, J.M.; Fernandez-Llebrez, P.; Perez-Figares, J.M. Effect of decreased environmental salinity on growth hormone cells in the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Journal of fish biology 1995, 46(3), 494-500. [CrossRef]

- Mancera, J.M.; McCormick, S.D. Evidence for growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis regulation of seawater acclimation in the Euryhaline Teleost Fundulus heteroclitus. General and comparative endocrinology 1998, 111(2), 103-112. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.H.; Piermarini, P.M; Choe, K.P. The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid-base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiological Reviews 2005, 85, 97-177. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Garcia, A.; Partridge, G.J.; Flik, G.; Roques, J.A.; Abbink, W. Ambient salinity and osmoregulation, energy metabolism and growth in juvenile yellowtail kingfish (Seriola lalandi Valenciennes 1833) in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture Research 2015, 46(11), 2789-2797.

- O’Neill, B.; De Raedemaecker, F.; McGrath, D.; Brophy, D. An experimental investigation of salinity effects on growth, development and condition in the European flounder (Platichthys flesus L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2011, 410, 39-44.

- Butt, R.L.; Volkoff, H. Gut microbiota and energy homeostasis in fish. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019, 10 (9), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C.H.; Wu, S.M.; Tseng, Y.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Baba, O.; Hwang, P.P. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in gills and liver of the euryhaline tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) during acclimation to seawater. Journal of Experimental Biology 2007, 210(19), 3494-3504. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.C.; Hwang, P.P. Some insights into energy metabolism for osmoregulation in fish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2008, 148(4), 419-429.

- Tsui, W.C.; Chen, J.C.; Cheng, S.Y. The effects of a sudden salinity change on cortisol, glucose, lactate, and osmolality levels in grouper Epinephelus malabaricus. Fish physiology and biochemistry 2012, 38, 1323-1329. [CrossRef]

- De Backer, D. Lactic acidosis. Intensive care medicine 2003, 29, 699-702.

- Driedzic, W.R.; Hochachka, P.W. Metabolism in fish during exercise. In Fish physiology; Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 1978; Volume 7, pp. 503-543.

- Schwalme, K.; Mackay, W. C. Mechanisms that elevate the glucose concentration of muscle and liver in yellow perch (Perca flavescens Mitchill) after exercise–handling stress. Canadian journal of zoology 1991, 69(2), 456-461. [CrossRef]

- Polakof, S.; Mommsen, T.P.; Soengas, J.L. Glucosensing and glucose homeostasis: from fish to mammals. Comparative Biochemistry Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2011 160, 123-149.

- Polakof, S.; Panserat, S.; Soengas, J.L.; Moon, T.W. Glucose metabolism in fish: a review. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 2012, 182, 1015-1045.

- Stone DAJ (2003) Dietary carbohydrate utilization by fish. Reviews in Fisheries Sciences 2003, 11, 337-369.

- Fiol, D.F.; Kültz, D. Osmotic stress sensing and signaling in fishes. The FEBS journal 2007, 274(22), 5790-5798. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, E.S.; Garside, E.T. Salinity preferences of Fundulus heteroclitus and F. diaphanus (Pisces: Cyprinodontidae): their role in geographic distribution. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1974, 52(8), 997-1003.

- Whitehead, A. The evolutionary radiation of diverse osmotolerant physiologies in killifish (Fundulus sp.). Evolution 2010, 64(7), 2070-2085.

- Gaumet, F.; Boeuf, G.; Severe, A.; Le Roux, A.; Mayer-Gostan, N. Effects of salinity on the ionic balance and growth of juvenile turbot. Journal of Fish Biology 1995, 47(5), 865-876. [CrossRef]

- Imsland, A.K.; Foss, A.; Gunnarsson, S.; Berntssen, M.H.; FitzGerald, R.; Bonga, S.W.; Ham, E.V.; Naevdal, G.; Stefansson, S.O. The interaction of temperature and salinity on growth and food conversion in juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Aquaculture 2001, 198(3-4), 353-367. [CrossRef]

- Sadoul, B.; Geffroy, B. Measuring cortisol, the major stress hormone in fishes. Journal of Fish Biology 2019, 94(4), 540-555. [CrossRef]

- Evans D.H.; Rose R.E.; Roeser J.M.; Stidham J.D. NaCl transport across the opercular epithelium of Fundulus heteroclitus is inhibited by an endothelin to NO, superoxide, and prostanoid signaling axis. American Journal of Physiology; Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2004, 286, R560-R568.

- McCormick, S.D.; Bradshaw, D. Hormonal control of salt and water balance in vertebrates. General and Comparative Endocrinology 2006, 147, 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Fries, C.R. Effects of environmental stressors and immunosuppressants on immunity in Fundulus heteroclitus. American Zoologist 1986, 26(1), 271-282. [CrossRef]

- Mommsen, T.P.; Vijayan, M.M.; Moon, T.W. Cortisol in teleosts: dynamics, mechanisms of action and metabolic regulation. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 1999, 9, 211-268.

- Tahir, D.; Shariff, M.; Syukri, F.; Yusoff, F.M. Serum cortisol level and survival rate of juvenile Epinephelus fuscoguttatus following exposure to different salinities. Veterinary World 2018, 11(3), 327. [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Soria, H. Fish digestive lipase quantification methods used in aquaculture studies. Frontiers in Aquaculture 2023, 2, 1225216. [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Soria, H. Improving and standardizing protocols for alkaline protease quantification in fish. Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 13(1), 43-65. [CrossRef]

- El-Leithy, A.A.; Hemeda, S.A.; El Naby, W.S.A.; El Nahas, A.F.; Hassan, S.A.; Awad, S.T.; El-Deeb, S.I.; Helmy, Z.A. Optimum salinity for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) growth and mRNA transcripts of ion-regulation, inflammatory, stress-and immune-related genes. Fish physiology and biochemistry 2019, 45, 1217-1232. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, H.; Hu, N.; Zou, F.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Tan, B.; Zhang, S. Effects of dietary Clostridium autoethanogenum protein on the growth, disease resistance, intestinal digestion, immunity and microbiota structure of Litopenaeus vannamei reared at different water salinities. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 1034994. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.F., Gao, X.Q., Yu, J.X., Qian, X.M., Xue, G.P., Zhang, Q.Y.; Liu, B.L.; Hong, L. Effects of different salinities on growth performance, survival, digestive enzyme activity, immune response, and muscle fatty acid composition in juvenile American shad (Alosa sapidissima). Fish physiology and biochemistry 2017, 43, 761-773. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ai, T.; Yang, J.; Shang, M.; Jiang, K.; Yin, Y.; Gao, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, N.; Ju, J.; Qin, B. Effects of salinity on growth, digestive enzyme activity, and antioxidant capacity of spotbanded scat (Selenotoca multifasciata) Juveniles. Fishes 2024, 9(8), 309.

- Zhang, N.; Yang, R.; Fu, Z.; Yu, G.; Ma, Z. Mechanisms of digestive enzyme response to acute salinity stress in juvenile yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Animals 2023, 13(22), 3454. [CrossRef]

- Stoknes, I.S.; Økland, H.M.; Falch, E.; Synnes, M. Fatty acid and lipid class composition in eyes and brain from teleosts and elasmobranchs. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2004, 138(2), 183-191. [CrossRef]

- Morais, S.; Torres, M.; Hontoria, F.; Monroig, Ó.; Varó, I.; Agulleiro, M.J.; Navarro, J.C. Molecular and functional characterization of Elovl4 genes in Sparus aurata and Solea senegalensis pointing to a critical role in very long-chain (> C24) fatty acid synthesis during early neural development of fish. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21(10), 3514. [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.F.C.; Tocher, D.R.; Monroig, Ó. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in chordates: Insights into the evolution of Fads and Elovl gene repertoire. Progress in Lipid Research 2016, 62, 25-40. [CrossRef]

- Monroig, Ó.; Shu-Chien, A.C.; Kabeya, N.; Tocher, D.R.; Castro, L.F.C. Desaturases and elongases involved in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in aquatic animals: From genes to functions. Progress in lipid research 2022, 86, 101157. [CrossRef]

- Oboh, A.; Kabeya, N.; Carmona-Antoñanzas, G.; Castro, L.F.C.; Dick, J.R., Tocher, D.R.; Monroig, O. Two alternative pathways for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22: 6n-3) biosynthesis are widespread among teleost fish. Scientific reports 2017a, 7(1), 3889.

- Rivera-Pérez, C.; Valenzuela-Quiñonez, F.; Caraveo-Patiño, J. Comparative and functional analysis of desaturase FADS1 (∆5) and FADS2 (∆6) orthologues of marine organisms. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics 2020, 35, 100704. [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, H. Metabolism of highly unsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2000, 1486(2-3), 219-231.

- Suh, M.; Clandinin, M.T. 20:5n-3 but not 22:6n-3 is a preferred substrate for synthesis of n-3 Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids (C24-C36) in Retina. Current Eye Research 2005, 30, 959-968.

- Ge, L.; Yang, H.; Lu, W.; Cui, Y.; Jian, S.; Song, G.; Xue, J.; He, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Q. Identification and comparison of palmitoleic acid (C16: 1 n-7)-derived lipids in marine fish by-products by UHPLC-Q-exactive orbitrap mass spectrometry. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 115, 104925. [CrossRef]

- Le, H.D.; Meisel, J.A.; de Meijer, V.E.; Gura, K.M.; Puder, M. The essentiality of arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2009, 81(2-3), 165-170. [CrossRef]

- Monroig, Ó.; Rotllant, J.; Cerdá-Reverter, J.M.; Dick, J.R.; Figueras, A.; Tocher, D.R. Expression and role of Elovl4 elongases in biosynthesis of very long-chain fatty acids during zebrafish Danio rerio early embryonic development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2010, 1801, 1145-1154. [CrossRef]

- Oboh, A.; Navarro, J.C.; Tocher, D.R.; Monroig, Ó. Elongation of very long-chain (>C24) fatty acids in Clarias gariepinus: Cloning, functional characterization and tissue expression of elovl4 elongases. Lipids 2017b, 52, 837-848.

- Agbaga, M.P.; Mandal, M.N.A.; Anderson, R.E. Retinal very long-chain PUFAs: New insights from studies on ELOVL4 protein. Journal of Lipid Research 2010, 51, 1624-1642. [CrossRef]

- Deák, F.; Anderson, R.E.; Fessler, J.L.; Sherry, D.M. Novel cellular functions of very long chain-fatty acids: Insight from ELOVL4 mutations. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2019, 13, 428. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Monroig, Ó.; Navarro, J.C.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q.C. Molecular and functional characterisation of two elovl4 elongases involved in the biosynthesis of very long-chain (>C24) polyunsaturated fatty acids in black seabream Acanthopagrus schlegelii. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2017, 212, 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Monroig, Ó.; Wang, T.; Yuan, Y.; Navarro, J.C.; Hontoria, F.; Liao, K.; Tocher, D.R.; Mai, K.; Xu, W.; et al. Functional characterization and differential nutritional regulation of putative Elovl5 and Elovl4 elongases in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Garlito, B.; Portolés, T.; Niessen, W.M.A.; Navarro, J.C.; Hontoria, F.; Monroig, Ó.; Varó, I.; Serrano, R. Identification of very long-chain (>C24) fatty acid methyl esters using gas chromatography coupled to quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source. Analytica Chimica Acta 2019, 1051, 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Hopiavuori, B.R.; Deák, F.; Wilkerson, J.L.; Brush, R.S.; Rocha-Hopiavuori, N.A.; Hopiavuori, A. R.; Ozan, K.G.; Sullivan, M.T.; Wren, J.D.; Georgescu, C.; Szweda, L.; Awasthi, V.; Towner, R.; Sherry, D.M.; Anderson, R.E.; Agbaga M.P. Homozygous expression of mutant ELOVL4 leads to seizures and death in a novel animal model of very long-chain fatty acid deficiency. Molecular Neurobiology 2018, 55, 1795-1813. [CrossRef]

- Hopiavuori, B.R.; Anderson, R.E.; Agbaga, M.P. ELOVL4: Very long chain fatty acids serve an eclectic role in mammalian health and function. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2019, 69, 137-158. [CrossRef]

- Bejarano-Escobar, R.; Blasco, M.; DeGrip, W.; Oyola-Velasco, J.; Martin-Partido, G.; Francisco-Morcillo, J. Eye development and retinal differentiation in an altricial fish species, the Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis, Kaup 1858). Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2010, 314 (7), 580-605.

- Vihtelic, T.S.; Soverly, J.E.; Kassen, S.C.; Hyde, D.R. Retinal regional differences in photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in light-lesioned albino zebrafish. Experimental Eye Research 2006, 82, 558-575. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Genbank Acc. Nº | Amplicon length (bp) |

Primer sequence (5’–3’) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| actin beta (actb) | XM_012850364.3 | 163 | F: GCCAACAGGGAGAAGATGAC R: CCTCGTAGATGGGCACTG |

|

| eukaryotic elongation factor 1 alpha (eef1a) | XM_012852503.3 | 179 | F: CACCACCACAGGACACCTTA R: CAAACTTCCACAGCGAGATG |

|

| fatty acyl desaturase 2a (fads2a) | XM_036148888.1 | 200 | F: CACTGGTTTGTGTGGGTGAC R: AGGTGGTAGTTGTGCCTTGG |

|

| fatty acyl desaturase 2b (fads2b) | XM_012865392.3 | 175 | F: AGGACTGGCTGACCATGC R: CCGTGTTTCTCACACAGCTC |

|

| fatty acyl desaturase 2a (fads2c) | XM_036148890.1 | 183 | F: AATCAAGACTGGCTGACCAT R: CACTCCGTGCTTCTCACACA |

|

| fatty acid elongase 5 (elovl5) | XM_036126476.1 | 85 | F: TGTTCTCGTTCATTGTGCTTT R: TTCTGATGCTCCTTCCTTCG |

|

| fatty acid elongase 4a (elovl4a) | XM_012864666.3 | 200 | F: AGGAGCCCTCTGGTGGTACT R: GGATCAGTGCGTTCATGTGT |

|

| fatty acid elongase 4b (elovl4b) | XM_012868850.3 | 177 | F: TTCGGTGCAACCATCAACT R: GCAGCCAGTGTAGAGGGAAT |

|

| Parameters | 2 ppt | 20 ppt | 40 ppt | 60 ppt |

| Mi (g)* | 4.67 ± 0.33 | 3.89 ± 0.25 | 4.52 ± 0.39 | 3.82 ± 0.24 |

| Mf (g)* | 7.34 ± 0.34b | 5.44 ± 0.20a | 5.66 ± 0,26a | 4.72 ± 0.15a |

| TLf (cm)* | 6.68 ± 0.11b | 6.23 ± 0.11a | 6.22 ± 0.11a | 5.96 ± 0.08a |

| K * | 2.47 ± 0.05b | 2.44 ± 0.05b | 2.38 ± 0.03ab | 2.25 ± 0.03a |

| MG (%) * | 54.20 ± 2.85b | 51.54 ± 5.12b | 40.16 ± 6.01ab | 26.92 ± 6.33a |

| SGR (% day-1) * | 0.86 ± 0.05b | 0.83 ± 0.10b | 0.67 ± 0.10ab | 0.48 ± 0.11a |

| FE * | 0.54 ± 0.00b | 0.52 ± 0.02b | 0.58 ± 0.04b | 0.39 ± 0.03a |

| HSI (%) ** | 2.97 ± 0.28ab | 2.68 ± 0.15ab | 3.32 ± 0.21b | 2.31 ± 0.21a |

| VSI (%) ** | 7.58 ± 0.39ab | 7.93 ± 0.29ab | 8.57 ± 0.29b | 7.13 ± 0.34a |

| ILI (%) ** | 89.07 ± 4.06 | 93.76 ± 5.44 | 98.77 ± 5.39 | 93.55 ± 4.08 |

| Plasma | 2 ppt | 20 ppt | 40 ppt | 60 ppt |

| Osmolality (mOsm kg-1) | 435.8 ± 19,14ab | 392.7 ± 12.26a | 381.4 ± 6.282a | 469.8 ± 22.24b |

| TBA (µmol/L) | 71.94 ± 18.16 | 72.48 ± 13.36 | 67.7± 10.03 | 69.63 ± 14.31 |

| Cortisol (ng/mL) | 99.6 ± 19.38a | 237.3 ± 34.62ab | 231.4 ± 37.98ab | 358.5 ± 49.21b |

| Proteins (mg/mL) | 38.45 ± 3.26 | 33.97 ± 0.95 | 38.63 ± 0.83 | 31.78 ± 0.94 |

| Glucose (mM) | 5.62 ± 1.20 | 4.63 ± 0.41 | 3.91 ± 0.55 | 4.35 ± 0.43 |

| Lactate (mM) | 14.93 ± 1.27 | 14.03 ± 0.85 | 13.56 ± 0.65 | 12.71 ± 0.98 |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 5.31 ± 0.39b | 3.20 ± 0.24a | 4.77 ± 0.28b | 2.75 ± 0.21a |

| Cholesterol (mM) | 4.75 ± 0.16b | 4.52 ± 0.21ab | 5.16 ± 0.22b | 3.81 ± 0.25a |

| Liver | ||||

| Glucose (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 14.61 ± 0.91a | 14.56 ± 0.67a | 21.12 ± 2.05b | 18.46 ± 0.23b |

| Glycogen (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 43.03 ± 4.51 | 31.70 ± 2.07 | 42.21 ± 6.03 | 38.45 ± 4.33 |

| Lactate (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 7.43 ± 0.83a | 5.85 ± 0.46a | 12.31 ± 1.78b | 11.05 ± 1.16b |

| Triglycerides (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 68.42 ± 3.70 | 72.03 ± 5.77 | 67.33 ± 5.97 | 60.60 ± 5.52 |

| Cholesterol (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 27.10 ± 2.56 | 30.39 ± 2.53 | 22.69 ± 1.75 | 23.82 ± 2.09 |

| Muscle | ||||

| Glucose (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 2.64 ± 0.18b | 2.38 ± 0.19ab | 2.48 ± 0.15ab | 1.88 ± 0.15a |

| Glycogen (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 3.02 ± 0.50a | 2.13 ± 0.43a | 5.71 ± 0.82b | 3.64 ± 0.63ab |

| Lactate (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 21.45 ± 0.91 | 22.22 ± 1.94 | 22.29 ± 0.98 | 22.14 ± 1.05 |

| Triglycerides (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 4.48 ± 0.51b | 3.22 ± 0.50ab | 3.00 ± 0.44ab | 2.78 ± 0.35a |

| Cholesterol (mmol g-1 w.m.) | 1.79 ± 0.35 | 1.92 ± 0.39 | 1.92 ± 0.49 | 2.34 ± 0.53 |

| Brain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsaturated Fatty Acid | 2 ppt | 20 ppt | 40 ppt | 60 ppt |

| 14:1n-5 (myristoleic acid) | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| 16:1n-7 (palmitoleic acid) | 3.51 ± 0.59a | 2.89 ± 0.54a | 3.08 ± 0.60a | 8.08 ± 1.25b |

| 18:1n-9 (oleic acid) | 1.11 ± 0.20ab | 0.92 ± 0.10a | 1.34 ± 0.33ab | 2.40 ± 0.57b |

| 18:2n-6 (linoleic acid) | 0.59 ± 0.10ab | 0.42 ± 0.05a | 0.75 ± 0.24ab | 1.33 ± 0.32b |

| 18:3n-6 (γ-linolenic acid) | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.05 |

| 18:3n-3 (α-linolenic acid) | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.04 |

| 20:3n-6 (dihomo-γ-linolenic acid) | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.05 |

| 20:3n-3 (docosatrienoic acid) | 0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.06 ± 0.01a | 0.51 ± 0.16b |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid) | 2.45 ± 0.33ab | 1.41 ± 0.26a | 1.81 ± 0.25a | 4.81 ± 0.85b |

| 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) | 3.69 ± 0.50ab | 1.31 ± 0.27a | 5.17 ± 0.47b | 4.13 ± 0.27ab |

| 22:1n-9 (erucic acid) | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.13 | 1.06 ± 0.18 |

| 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) | 11.82 ± 2.04 | 12.69 ± 2.17 | 17.89 ± 4.06 | 24.12 ± 5.23 |

| 22:2n-6 (docosadienoic acid) | 0.97 ± 0.15 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.12 |

| Total MUFA | 5.44 ± 0.86 | 4.64 ± 0.73 | 5.36 ± 1.08 | 11.75 ± 2.02 |

| Total PUFA | 20.60 ± 3.22 | 17.8 ± 3.02 | 27.56 ± 5.15 | 37.00 ± 7.09 |

| Total UFA | 26.05 ± 4.08 | 22.44 ± 3.75 | 32.92 ± 6.22 | 48.76 ± 9.11 |

| Eye | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsaturated Fatty Acid | 2 ppt | 20 ppt | 40 ppt | 60 ppt |

| 14:1n-5 (myristoleic acid) | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.02 |

| 16:1n-7 (palmitoleic acid) | 4.07 ± 0.08ab | 3.83 ± 0.28ab | 3.54 ± 0.24a | 4.61 ± 0.10b |

| 18:1n-9 (oleic acid) | 2.74 ± 0.20 | 2.46 ± 0.30 | 2.02 ± 0.26 | 2.70 ± 0.09 |

| 18:2n-6 (linoleic acid) | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.12 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 1.00 ± 0.03 |

| 18:3n-6 (γ-linolenic acid) | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 0.15 ± 0.11 | 0.21 ± 0.08 |

| 18:3n-3 (α-linolenic acid) | 1.25 ± 0.16 | 1.27 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.23 | 1.10 ± 0.06 |

| 20:3n-6 (dihomo-γ-linolenic acid) | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| 20:3n-3 (docosatrienoic acid) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid) | 2.62 ± 0.22 | 3.14 ± 0.21 | 3.50 ± 0.26 | 2.67 ± 0.23 |

| 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) | 1.83 ± 0.12b | 1.44 ± 0.13ab | 1.36 ± 0.23ab | 0.84 ± 0.06a |

| 22:1n-9 (erucic acid) | 0.88 ± 0.16 | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 0.95 ± 0.39 | 0.80 ± 0.08 |

| 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) | 16.03 ± 0.46 | 19.31 ± 0.45 | 16.71 ± 1.68 | 15.12 ± 0.99 |

| 22:2n-6 (docosadienoic acid) | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| Total MUFA | 8.08 ± 0.48 | 7.08 ± 0.75 | 6.42 ± 0.94 | 8.39 ± 0.30 |

| Total PUFA | 23.23 ± 1.11 | 26.52 ± 1.07 | 23.40 ± 2.63 | 21.20 ± 1.43 |

| Total UFA | 31.31 ± 1.59 | 33.60 ± 1.82 | 29.82 ± 3.56 | 29.59 ± 1.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).