Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

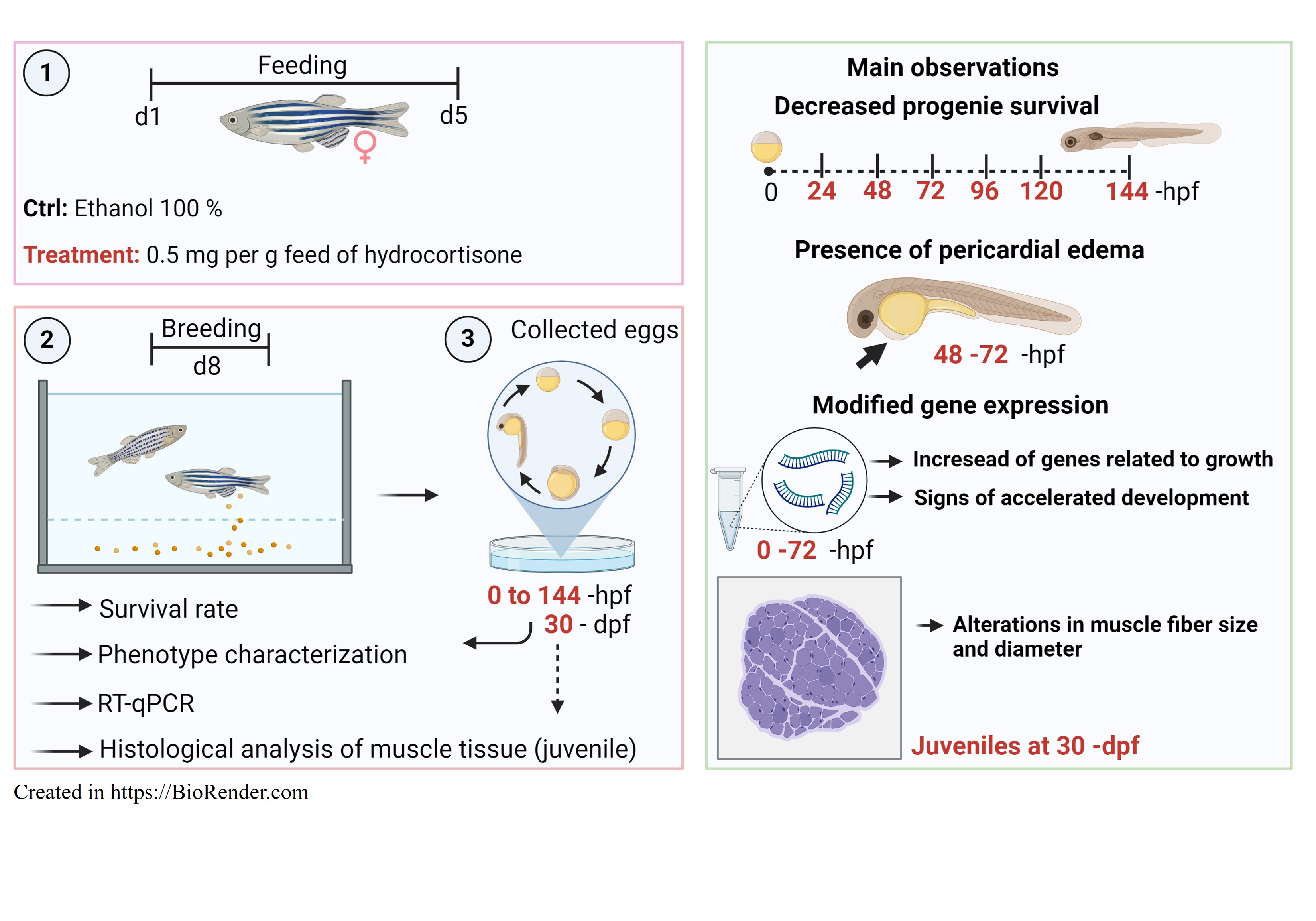

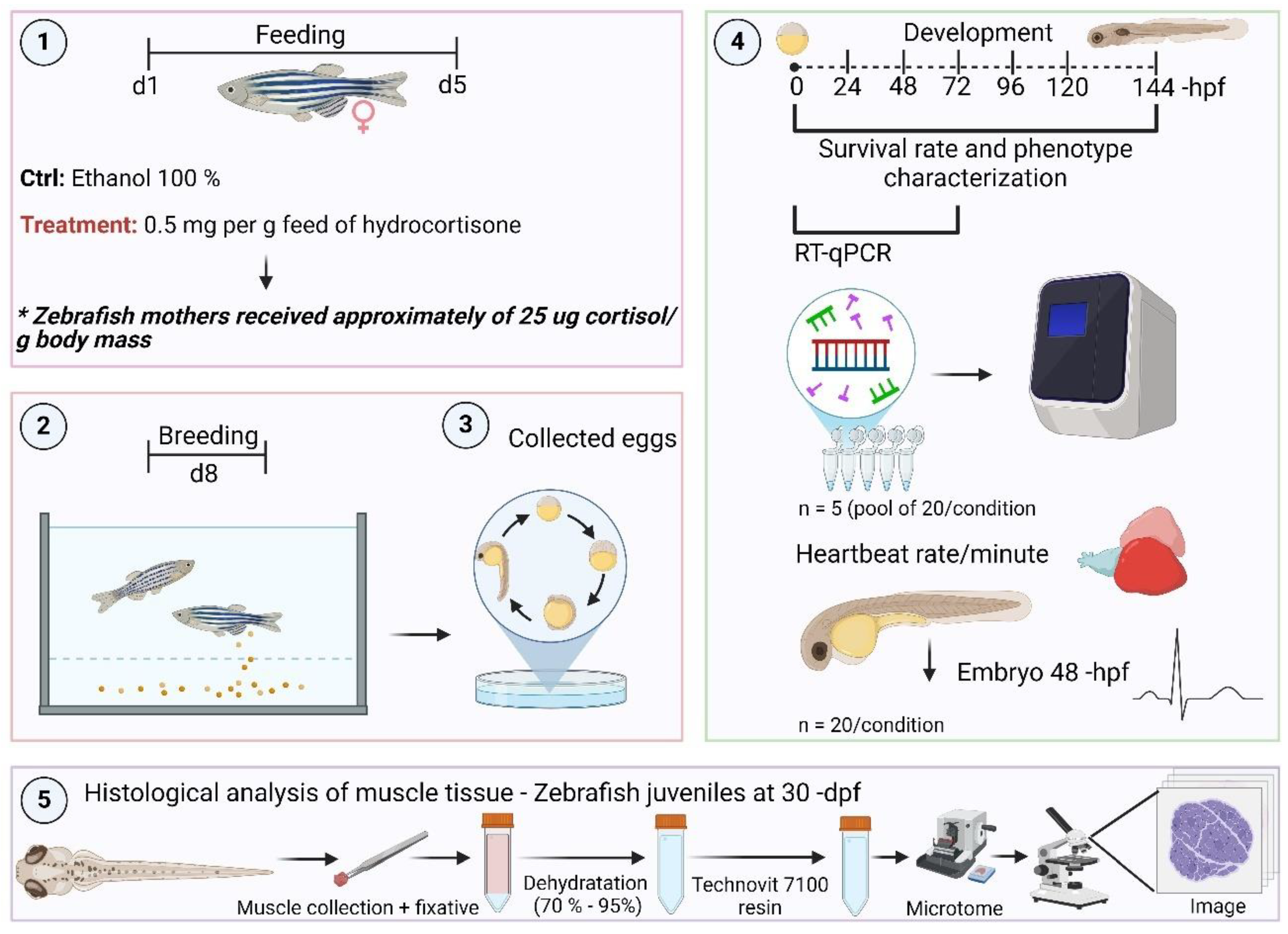

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal husbandry

2.2. Maternal stress-associated cortisol

2.3. Breeding

2.4. Transcript levels of the somatotropic axis by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

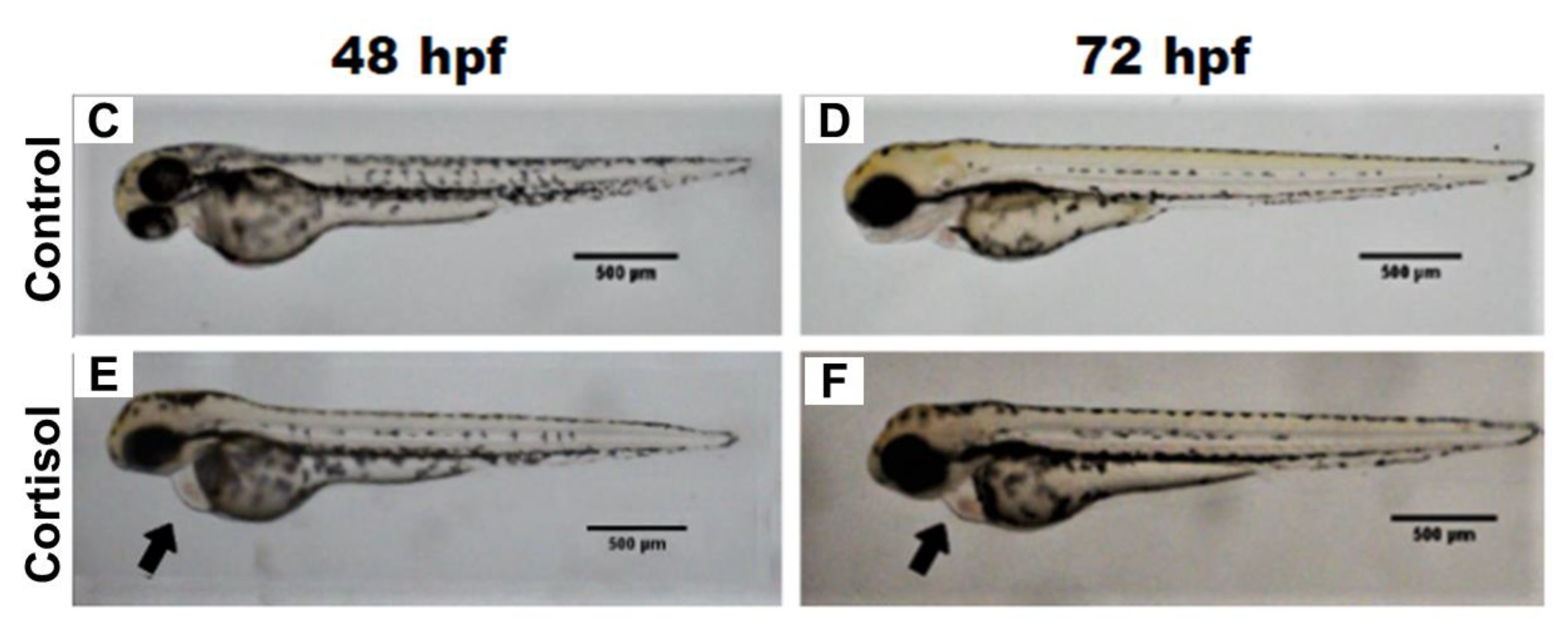

2.5. Embryo and larvae phenotypes

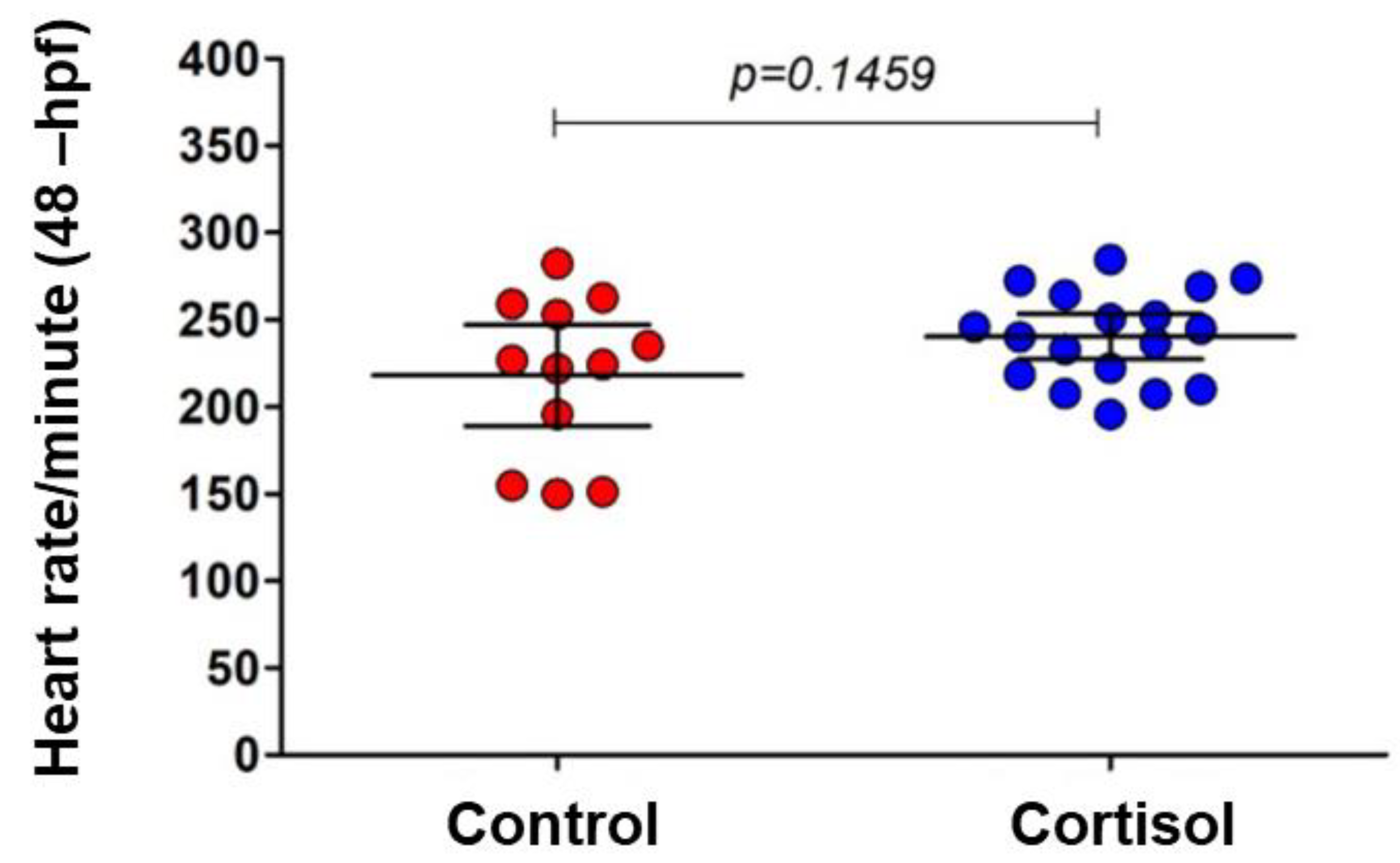

2.6. Heart rate measurement in embryos at 48 -hpf

2.7. Histological analysis of muscle tissue

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results

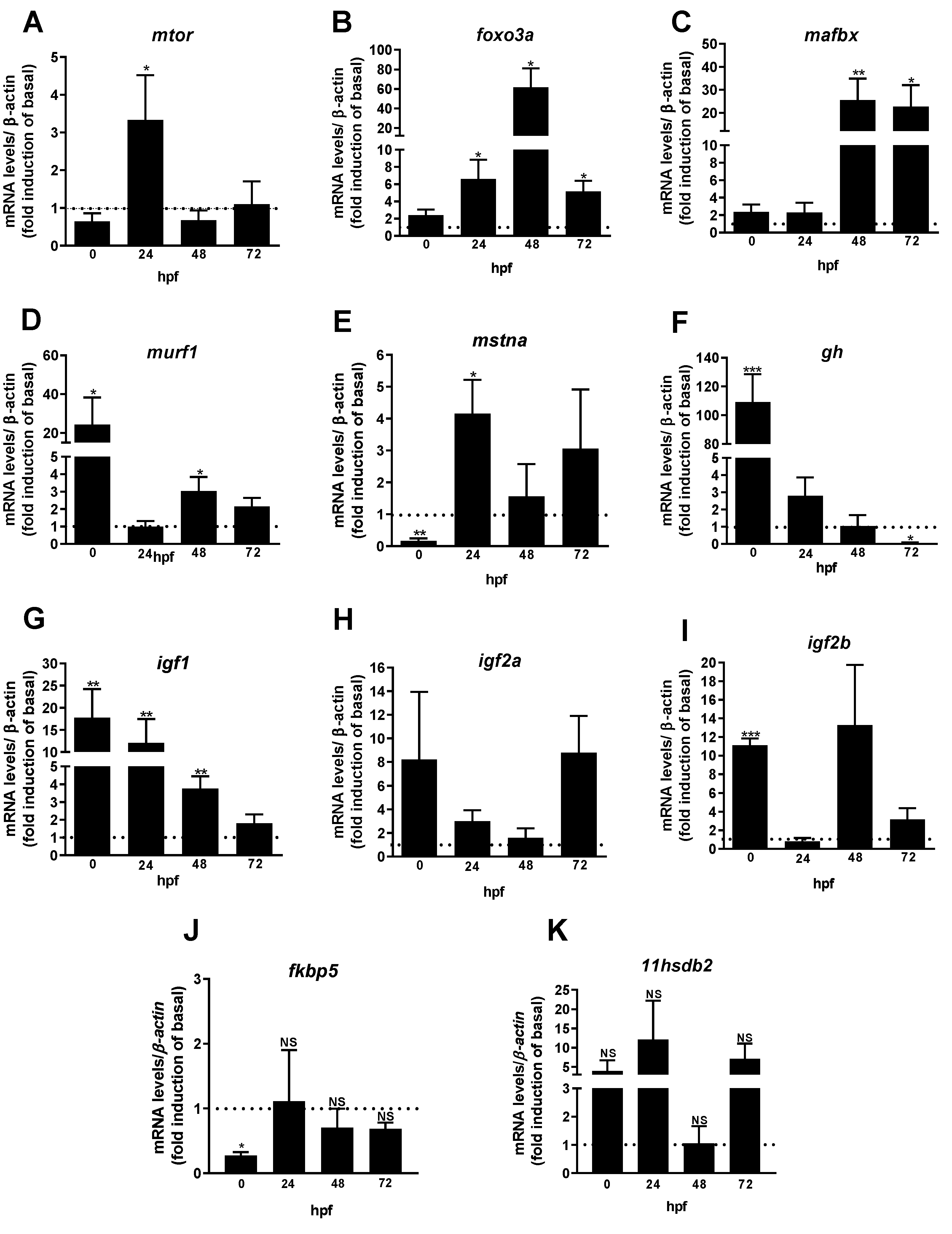

3.1. Maternal cortisol influences the mRNA expression levels of genes associated with the somatotropic and HPI axes in zebrafish offspring

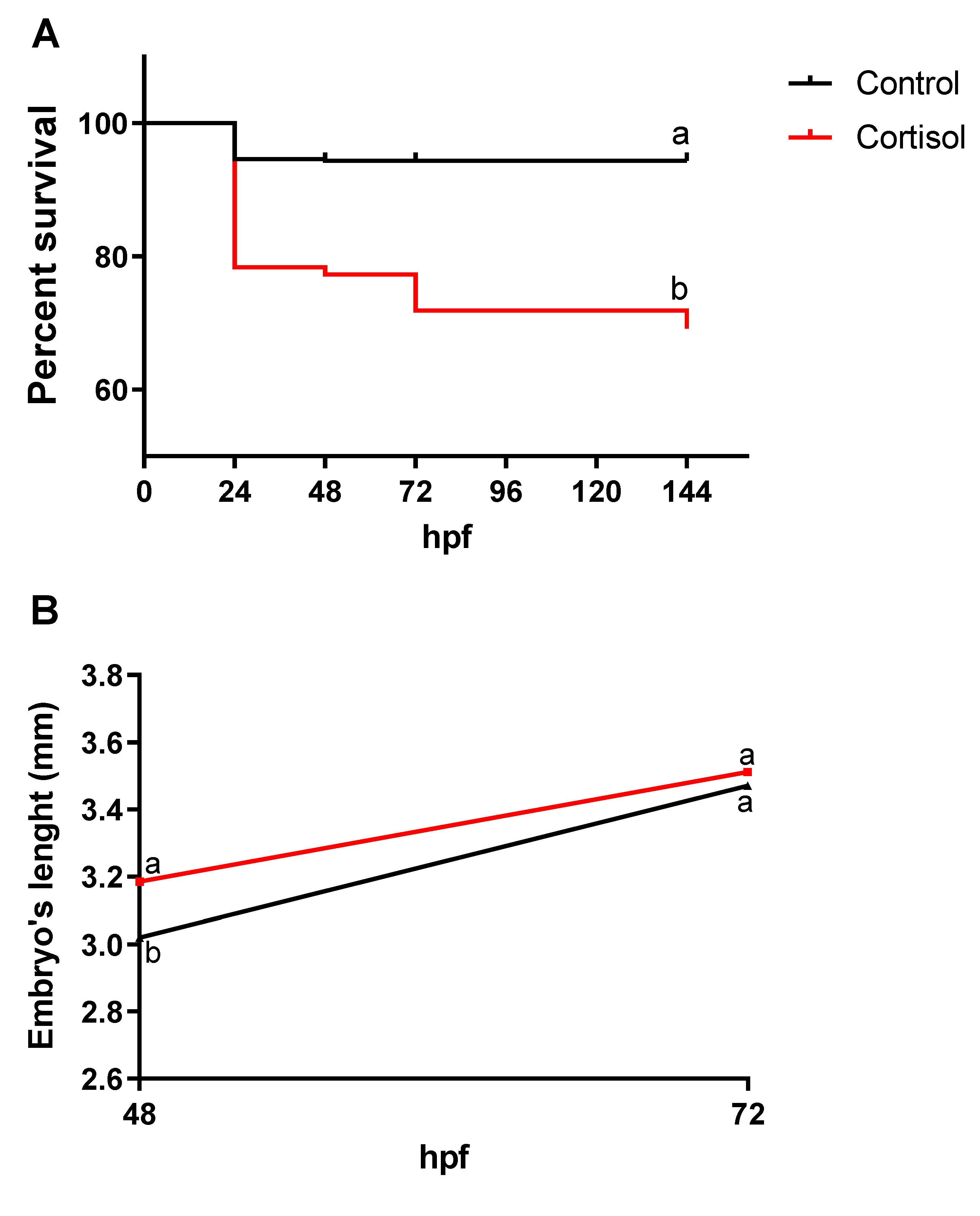

3.2. Maternal cortisol treatment affected different stages of offspring development in different parameters of evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tobi, E. W.; Slieker, R. C.; Luijk, R.; Dekkers, K. F.; Stein, A. D.; Xu, K. M. DNA methylation as a mediator of the association between prenatal adversity and risk factors for metabolic disease in adulthood. Sci Adv. 2018, 4, eaao4364, 1-10.

- Levine, S. Infantile experience and resistance to physiological stress. Science. 1957, 126 (3270), 405-405.

- Joseph, D.; Whirledge, S. Stress and the HPA axis: Balancing homeostasis and fertility. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 2224.

- Brunton, P. J.; Russell, J. A. Prenatal social stress in the rat programs neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress in the adult offspring: Sex-specific effects. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010, 22, 258–271.

- Dreiling, M.; Schiffner, R.; Bischoff, S.; Rupprecht, S.; Kroegel, N.; Schubert, H.; Rakers, F. Impact of chronic maternal stress during early gestation on maternal-fetal stress transfer and fetal stress sensitivity in sheep. Stress. 2017, 21, 1–10.

- D’Agostino, S.; Testa, M.; Aliperti, V.; Venditti, M.; Minucci, S.; Aniello, F.; Donizetti, A. Expression pattern dysregulation of stress- and neuronal activity-related genes in response to prenatal stress paradigm in zebrafish larvae. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2019, 24, 1005–1012.

- Entringer, S. Impact of stress and stress physiology during pregnancy on child metabolic function and obesity risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013, 16, 320–327.

- Coulon, M.; Wellman, C. L.; Marjara, I. S.; Janczak, A. M.; Zanella, A. J. Early adverse experience alters dendritic spine density and gene expression in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in lambs. Psychoneuroendocrinology.2013, 38, 1112-1121.

- Babenko, O.; Kovalchuk, I.; Metz, G. A. S. Stress-induced perinatal and transgenerational epigenetic programming of brain development and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015, 48, 70–91.

- Hirst, J. J.; Cumberland, A. L.; Shaw, J. C.; Bennett, G. A.; Kelleher, M. A.; Walker, D. W.; Palliser, H. K. Loss of neurosteroid-mediated protection following stress during fetal life. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016, 160, 181–188.

- Veru, F.; Laplante, D. P.; Luheshi, G., King, S. Prenatal maternal stress exposure and immune function in the offspring. Stress. 2014, 17, 133–148.

- Marques, A. H.; Bjørke-Monsen, A.-L.; Teixeira, A. L.; Silverman, M. N. Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: Impact on immune function, CNS development, and psychopathology. Brain Res. 2015, 1617, 28–46.

- Nesan, D.; Vijayan, M.M. Embryo exposure to elevated cortisol level leads to cardiac performance dysfunction in zebrafish. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 363, 85–91.

- Haussmann, M. F.; Longenecker, A. S.; Marchetto, N. M.; Juliano, S. A.; Bowden, R. M. Embryonic exposure to corticosterone modifies the juvenile stress response, oxidative stress and telomere length. Proc Biol Sci. 2011, 279, 1447–1456.

- De Fraipont, M.; Clobert, J.; John-Alder, H.; Meylan, S. Increased pre-natal maternal corticosterone promotes philopatry of offspring in common lizards Lacerta vivipara. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2000, 69, 404–4013.

- Tissier, M. L.; Williams, T. D.; Criscuolo, F. Maternal effects underlie ageing costs of growth in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). PloS ONE. 2014, 9, e97705.

- Faught, E.; Best, C.; Vijayan, M. M. Maternal stress-associated cortisol stimulation may protect embryos from cortisol excess in zebrafish. R Soc Open Sci. 2016, 24, 160032.

- Faught, E.; Vijayan, M. M. The mineralocorticoid receptor is essential for stress axis regulation in zebrafish larvae. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 18081.

- Yoshioka, E. T.O.; Mariano, W.S.; Santos, L.R.B. Estresse em peixes cultivados: Agravantes e atenuantes para o manejo rentável. In Manejo e sanidade de peixes em cultivo, 1st ed.; Tavares-Dias, M; Macapá: Embrapa Amapá, Brasil, 2009; pp. 226–247.

- Leatherland, J. F.; Li, M.; BARKATAKI, S. Stressors, glucocorticoids and ovarian function in teleosts. J of Fish Biol. 2010, 76, 86–111.

- Nesan, D.; Vijayan, M. M. Role of glucocorticoid in developmental programming: Evidence from zebrafish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2013, 181, 35–44.

- Alsop, D.; Vijayan, M. M. Development of the corticosteroid stress axis and receptor expression in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008, 294, R711–R719.

- Nesan, D.; Vijayan, M. M. Maternal cortisol mediates hypothalamus-pituitary-interrenal axis development in zebrafish. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 22582.

- Johnston, I. A.; Bower, N. I.; Macqueen, D. J. Growth and the regulation of myotome muscle mass in teleost fish. J Exp Biol. 2011, 214, 1617–1628.

- Keenan, S.; Currie, P. The developmental phases of zebrafish myogenesis. J Dev Biol. 2019, 7, 12.

- Hinits, Y.; Osborn, D. P. S.; Hughes, S. M. Differential requirements for myogenic regulatory factors distinguish medial and lateral somitic, cranial and fin muscle fibre populations. Development. 2009, 136, 403–414.

- Pikulkaew, S.; Benato, F.; Celeghin, A.; Zucal, C.; Skobo, T.; Colombo, L.; Valle, L. D. The knockdown of maternal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA alters embryo development in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2011, 240, 874–889.

- Alderman, S.L.; Mcguire, A.; Bernier, N.J.; Vijayan, M.M. Central and peripheral glucocorticoid receptors are involved in the plasma cortisol response to an acute stressor in rainbow trout. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012, 176, 79–85.

- Tsang, B.; Zahid, H.; Ansari, R.; Lee, R.C. Partap, A.; Gerlai, R. Breeding zebrafish: A review of different methods and a discussion on standardization. Zebrafish. 2017, 14, 561–573.

- Nóbrega R.H.; Greebe C.D.; Van De Kant H.; Bogerd J.; França L.R.; Schulz R.W. Spermatogonial stem cell niche and spermatogonial stem cell transplantation in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2010, 5, e12808.

- Tovo-Neto, A.; Martinez, Emanuel R. M.; Melo, A.G.; Doretto, L. B.; Butzge, A. J.; Rodrigues, M. S.; Nakajima, R.T.; Habibi, H. R.; Nóbrega, R.H. Cortisol directly stimulates spermatogonial differentiation, meiosis, and spermiogenesis in zebrafish (Danio rerio) testicular explants. Biomolecules. 2020, 10, 429.

- Figueiredo, M.A.; Mareco, E.A.; Silva, M.D.P.; Marins, L.F. Muscle-specific growth hormone receptor (GHR) overexpression induces hyperplasia but not hypertrophy in transgenic zebrafish. Transgenic Res. 2012, 21, 457–469.

- Sopinka, N. M.; Capelle, P. M.; Semeniuk, C. A. D.; Love, O. P. Glucocorticoids in fish eggs: variation, interactions with the environment, and the potential to shape offspring fitness. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2017, 90, 15–33.

- Glickman, N.; Yelon, D. Cardiac development in zebrafish: coordination of form and function. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002, 13, 507–513.

- Wood, A. W.; Duan, C.; Bern, H.A. Insulin-like growth factor signaling in fish. Int Rev Cytol. 2005, 243, 215–285.

- Nóbrega, R.H.; Morais, R.D.V.S.; Crespo, D.; De Waal, P.P.; França, L.R.; Schulz, R.W.; Bogerd, J. Fsh stimulates spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation in zebrafish via Igf3. Endocrinology. 2015, 156, 3804–3817.

- Wilson, K. S.; Matrone, G.; Livingstone, D. E. W.; Al-Dujaili, E. A. S.; Mullins, J. J.; Tucker, C.S.; Hadoke, P. W. F.; Kenyon, C. J.; Denvir, M. A. Physiological roles of glucocorticoids during early embryonic development of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Physiol. 2013, 591, 6209–6220.

- Cleveland, B.M.; Weber, G.M.; Blemings, K.P.; Silverstein, J.T. Insulin-like growth factor-I and genetic effects on indexes of protein degradation in response to feed deprivation in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009, 297, R1332–R1342.

- Acosta J.; Carpio Y.; Borroto I.; Gonzálezo.; Estradam.P. Myostatin gene silenced by RNAi show a zebrafish giant phenotype. J Biotechnol. 2005, 119, 324–331.

- Lee, C.; Hu, S.; Gong, H.; Chen, M.; Lu, J.; Wu, J. Suppression of myostatin with vector-based RNA interference causes a double-muscle effect in transgenic zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009, 387, 766–771.

- Maccatrozzo, L.; Bargelloni, L. ; Cardazzo, B.; Rizzo, G.; Patarnello, T. A novel second myostatin gene is present in teleost fish. FEBS Lett. 2001, 509, 36–40.

- Amali, A.A.; Lin, C. J.-F.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, W.-L.; Gong, H.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y.; Wu, J.-L. Up-regulation of muscle-specific transcription factors during embryonic somitogenesis of zebrafish (Danio rerio) by knock-down of myostatin-1. Dev Dyn. 2004, 229, 847–856.

- Gao, Y.; Dai, Z.; Shi, C.; Zhai, G.; Jin, X.; He, J.; Lou, Q.; Yin Z. Depletion of myostatin b promotes somatic growth and lipid metabolism in zebrafish. Front Endocrinol. 2016, 10, 332.

- Wilson, K. S.; Matrone, G.; Livingstone, D. E. W.; Al-Dujaili, E. A. S.; Mullins, J. J.; Tucker, C.S.; Hadoke, P. W. F.; Kenyon, C. J.; Denvir, M. A. Physiological roles of glucocorticoids during early embryonic development of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Physiol. 2013, 591, 6209–6220.

- Oakes, J.A.; Li, N.; Wistow, B.R.C.; Griffin, A.; Barnard, L.; Storbeck, K.-H.; Cunliffe, V.T.; Krone, N.P. Ferredoxin 1b deficiency leads to testis disorganization, impaired spermatogenesis, and feminization in zebrafish. Endocrinology. 2019, 160, 2401–2416.

- Keenan, S.; Currie, P. The developmental phases of zebrafish myogenesis. J Dev Biol. 2019, 7, 12.

- Nguyen, P.D.; Gurevich, D.B.; Sonntag, C.; Hersey, L.; Alaei, S.; Nim, H.T.; Siegel, A.; Hall, T.E.; Rossello, F.J.; Boyd, S.E. Muscle stem cells undergo extensive clonal drift during tissue growth via meox1-mediated induction of G2 cell-cycle arrest. Cell Stem Cell. 2017, 21, 107–119.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).