1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality each year in the current world [

1]. With fast pace life style, a high dietary intake of sodium is common in the adult and even in the young population. High salt intake is associated with elevated blood pressure, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. From the lab-based research to clinical data analysis, the results indicate strong positive relationship between high sodium intake and cardiovascular outcomes [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Gestational hypertension could contribute to the risk of developing hypertension later in life, and recent studies have suggested that gestational hypertension and preeclampsia are linked to cardiovascular complications [

7]. The high salt intake will decrease the implantation site in rats by changing the metabolism pathways and the homeostasis balance [

8]. High intake of salt during pregnancy affected fetal renal development associated with an altered expression of the renal key elements of renin angiotensin system using the pregnant ewes [

9], a relationship between high-salt diet in pregnancy and developmental changes of the cardiac cells and renin–angiotensin system [

10].

The Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is an important model organism extensively used for studying metabolic mechanism developmental biology [

11,

12] and genetics study [

13,

14,

15] due to its small size, optical transparency, easy treatment, low cost caring of the embryo. The zebrafish embryonic developmental and post embryonic zebrafish development are well established to further study of genetic changes that showed in the morphological changes [

16,

17].

High salt stress in the environment on zebrafish development has the impact on the hatch rate, survival rate, brain, heart and bladder development and reproductive system. The Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) and hedgehog pathways (Shh) are altered under the high salt condition [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. High-salt diets during pregnancy induce high blood pressure and increase predisposition to hypertension in offspring by altering of nitric oxide (NO)/protein kinase G (PKG) pathway [

23]. high salt also will impact the metabolism pathways, Renin angiotensin system and endocrine systems which will cause high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases [

24].

The intracellular mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway is a crucial cellular signaling cascade that transmits external signals to the cell interior, regulating various processes like cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [

25]. The MAPK signaling cascades likely play an important role in the pathogenesis of cardiac and vascular disease [

26,

27]. MAPK pathway is vital role in the salt sensitive hypertension [

28].

The mechanism of the high salt on blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases are involved in the metabolism pathways, Renin angiotensin system and endocrine systems. In previous study, we identified the high glucose effects on zebrafish development through Wnt signaling pathway [

29]. In this study, we investigated the MAPK and calcium pathways of salt condition on the zebrafish embryo development using the similar methodology as our previous published data [

29].

2. Materials and Methods

Table salt in 2% was used in this study. Embryonic media, E3 was purchased from Carolina Biological Supplies Company.

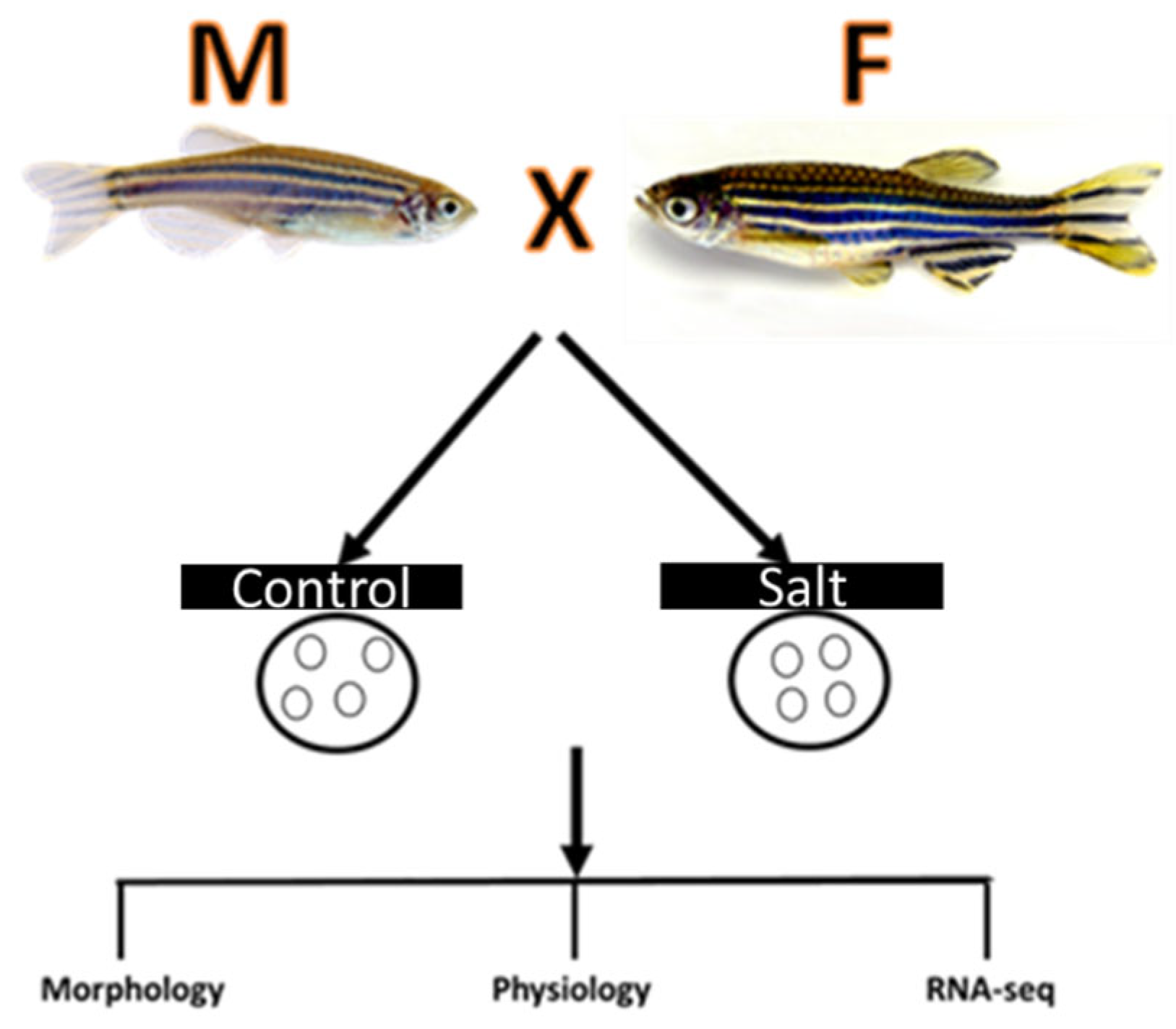

Figure 7.

The schematic of experimental design on the effect of salt on zebrafish embryos.

Figure 7.

The schematic of experimental design on the effect of salt on zebrafish embryos.

Adult wild-type zebrafish were obtained from breeding facilities at Carolina Biological Supply Co. Fish maintenance, breeding conditions, and egg production were done according to internationally accepted standards protocol [

30]. Embryos were obtained from Carolina Biological Supply, USA. Adult raised in embryonic media (E3) under standard conditions at 28.5 °C with a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle, and the embryonic stages are according to standard procedures [

11].

Embryos are separated into 5 petri dishes with each petri dish containing 25 embryos. At the time of grouping completion, the embryos are ~3 hours post fertilization (hpf). Once all 100 embryos have been separated in 5 groups the collection water was removed and replaced with E3 embryonic culture medium. Salt solution was added into two groups and E3 medium is used for three groups as control. The hatch rate and heart beats were recorded at different times as indicated in the results section. Each of the treatment concentrations as well as the control will undergo the same process.

The control and salt treated zebrafish embryos were collected for total RNA extraction. The experiment design includes 3 control samples and 2 salt treated samples. Total 5 RNA samples were extracted using Zymo RNA extraction kit (Irvine, CA) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Concentration of the RNA samples was measured by Nano drop 2000(DeNovix Inc.Wilmington, DE).

RNA seq was performed by experts at Novogene Corporation Inc. (West Coast: Sacramento, CA). The sample quality control, library preparation, Clustering and sequencing are in the supplemental methods.

RNA seq Data Analysis was performed by Novogene Corporation Inc. (West Coast: Sacramento, CA).

Briefly, Raw data (raw reads) of Fastq format were firstly processed through in-house per scripts. In this step, clean data (clean reads) were obtained by removing reads containing adapter, reads containing ploy-N and low-quality reads from raw data. At the same time, Q20, Q30 and GC content the clean data were calculated. All the downstream analyses were based on the clean data with high quality.

Reference genome and gene model annotation files were downloaded from genome website2directly. Index of the reference genome was built using Hisat2 v2.0.5 and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5. We selected Hisat2 as the mapping tool for that Hisat2 can generate a database of splice junctions based on the Gene model annotation file and thus a better mapping result than other non-splice mapping tools.

The mapped reads of each sample were assembled by StringTie (v1.3.3b) in a reference-based approach [

31]. StringTie uses a novel network flow algorithm as well as an optional de novo assembly step to assemble and quantitate full-length transcripts representing multiple splice variants for each gene locus.

FeatureCounts v1.5.0-p3 was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. And then FPKM of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and reads count mapped to this gene. FPKM, expected number of Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript sequence per-Millions base pairs sequenced, considers the effect of sequencing depth and gene length for the reads count at the same time, and is currently the most commonly used method for estimating gene expression levels.

(For DESeq2 with biological replicates) Differential expression analysis of two conditions/groups (two biological replicates per condition) was performed using the DESeq2R package (1.20.0). DESeq2 provide statistical routines for determining differential expression in digital gene expression data using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with an adjusted P-value <=0.05 found by DESeq2 were assigned as differentially expressed. (For edgeR without biological replicates) Prior to differential gene expression analysis, foreach sequenced library, the read counts were adjusted by edge R program package through one scaling normalized factor. Differential expression analysis of two conditions was performed using the edge R R package (3.22.5). The P values were adjusted using the Benjamini &Hochberg method. Corrected P-value of 0.05 and absolute foldchange of 2 were set as the3threshold for significantly differential expression.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes was implemented by the cluster Profiler R package, in which gene length bias was corrected. GO terms with corrected P value less than 0.05 were considered significantly enriched by differential expressed genes. We used cluster Profiler R package to test the statistical enrichment of differential expression genes in KEGG pathways.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) is a computational approach to determine if a predefined Gene Set can show a significant consistent difference between two biologicals states. The genes were ranked according to the degree of differential expression in the two samples, and then the predefined Gene Set were tested to see if they were enriched at the top or bottom of the list. Gene set enrichment analysis can include subtle expression changes. We use the local version of the GSEA analysis tool

http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp, GO, KEGG data set were used for GSEA independently

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Salt on Zebrafish Embryo Development

3.1.1. The Effect of Salt on Morphology and Physiology Changes

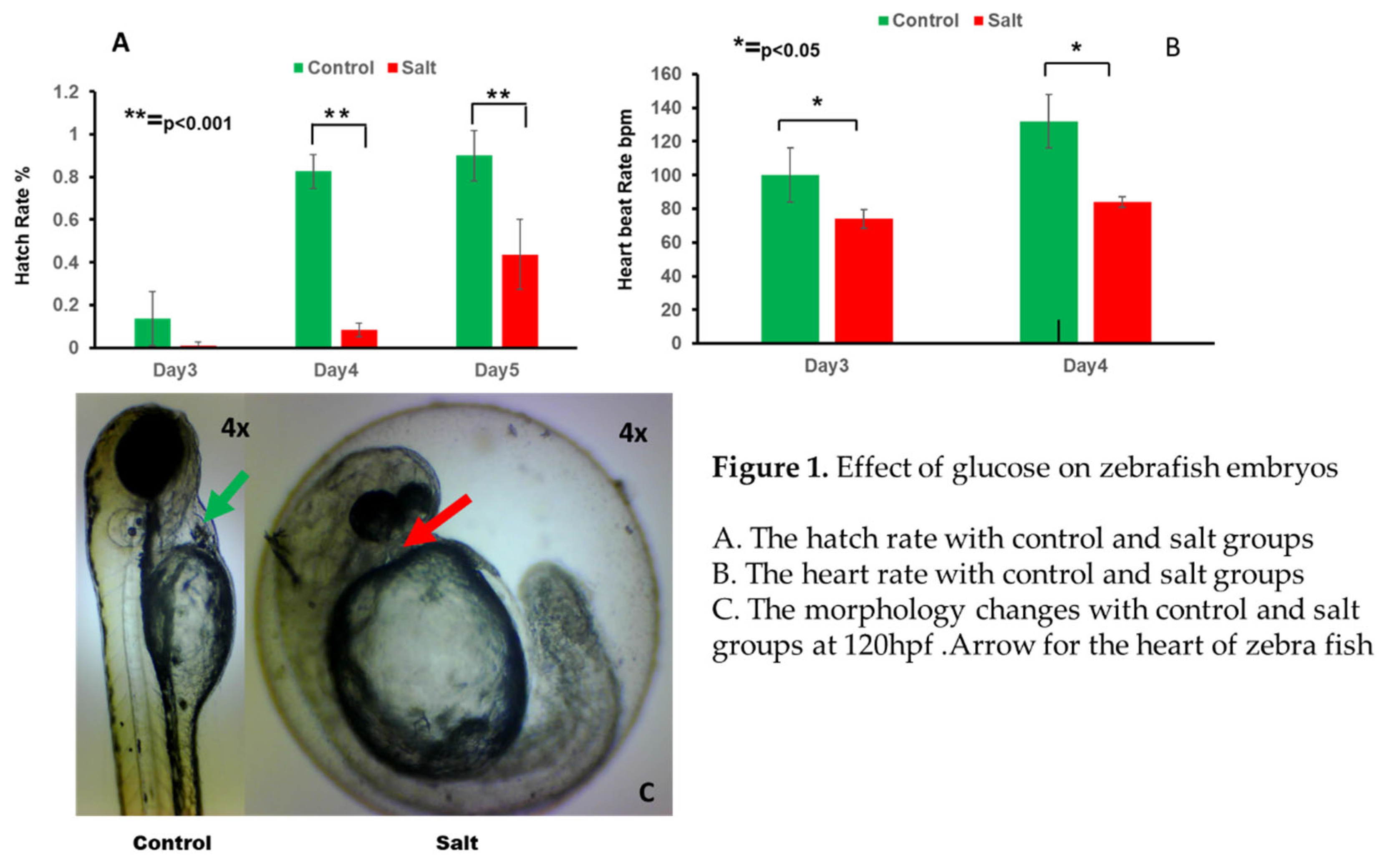

Salt exposure significantly impacted the developmental timeline of zebrafish embryos. Notably, the hatch rate was delayed by approximately 24 hours in the salt-exposed group compared to the control group, indicating a retardation in embryonic development associated with salt exposure. (

Figure 1A)

Evaluation of heart rate revealed significant alterations induced by salt exposure. On both day 3 and day 4 post-fertilization, embryos in the salt group exhibited a significantly reduction heart rate compared to those in the control group. The mean heart beat per minute is 100 and 74 in control and salt group respectively on day 3 while 132 and 84 on day 4 as shown in

Figure 1B.

Analysis of morphological parameters revealed distinct differences between the salt-exposed and control groups. At 120 hpf, embryos in the salt group exhibited smaller brain, heart, and tail morphology compared to those in the control group.The arrow focus on the heart size of zebrafish at 120hpf as shown in

Figure 1C. This suggests that salt exposure may interfere with the normal growth and development of these vital organs during early embryogenesis.

3.1.2. RNA-Seq Analysis Displayed Significant Gene Dysregulation in the Salt Treated Embryos

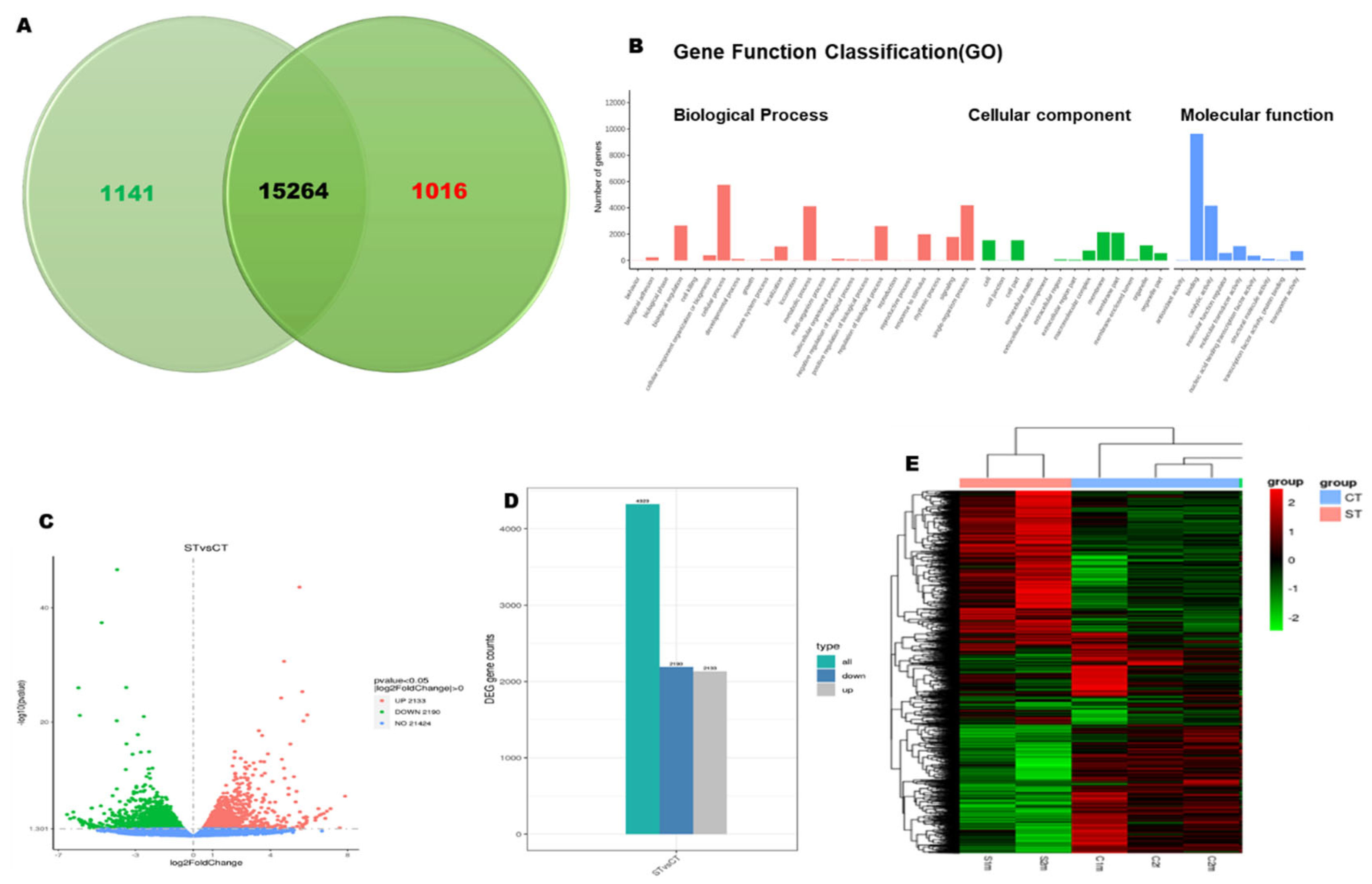

In this study, we investigated the global transcriptome changes in salt treated zebrafish embyos using RNAseq. Biological replicates were performed for the RNA seq. Venn Diagram shows the overlap genes and unique genes in these two groups data. (

Figure 2A).

Figure 2B shows the number of genes are identified in the gene function classification groups. With 25K transcripts, data analysis identified 4324(2%) differentially expressed genes(DEGs) with 2133 upregulated and 2190 downregulated respectively(fold chang>2 and p<0.05).(

Figure 2C,D). Gene expression differs between the control and high glucose treatement group shown in

Figure 2E heatmap.

To determine changes in expresson levels of individual genes, we identified the top 10 most significant up and down regulated genes are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The major GO biological precesses and molecular functions enriched from the top 10 upregulated genes includedEnables beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity, Arresting domain involved in protein transport, Pancreatic progenitor cell differentiation and proliferation factor b, Monocarboxylic acid transmembrane transport, Monocarboxylic acid transmembrane transport, Enable double stranded DNA binding activity and nucleosomal DNA binding activity, Enable double stranded DNA binding activity and nucleosomal DNA binding activity, Enable double stranded DNA binding activity and nucleosomal DNA binding activity, Ino80 complex component located in the nucleus

Glycerophosphocholine and phosphodiesterase activity, and within the top 10 downregulated genes, Nucleotidyltransferase activity and tRNA binding activity

Aconitate decarboxylase activity in mitochondria, Taurine: sodium symporter activity

L-glutamine transmembrane transporter activity, Involved in protein coding

Taurine:sodium symporter activity, Intracellular signal transduction, Organic cation transmembrane transporter activity, Protein coding activity, ATP binding activity, protein serine kinase activity and protein serine/threonine kinase activity.

3.1.3. Functional Analysis of DEGs Using Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis

In order to identify the functional associations of the DEGs, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed by the cluster Profiler R package, in which gene length bias was correct-ed. GO terms withcorrected Pvalue less than 0.05 were considered significantly en-riched by differentialexpressed genes. Aamong GO analysis, 24 Biological process(BP), 14 Cellular Component (CC) and 8 Molecular Function (MF) were identified.

Figure 2B shows the GO analysis for both up and down regulated DEGs.

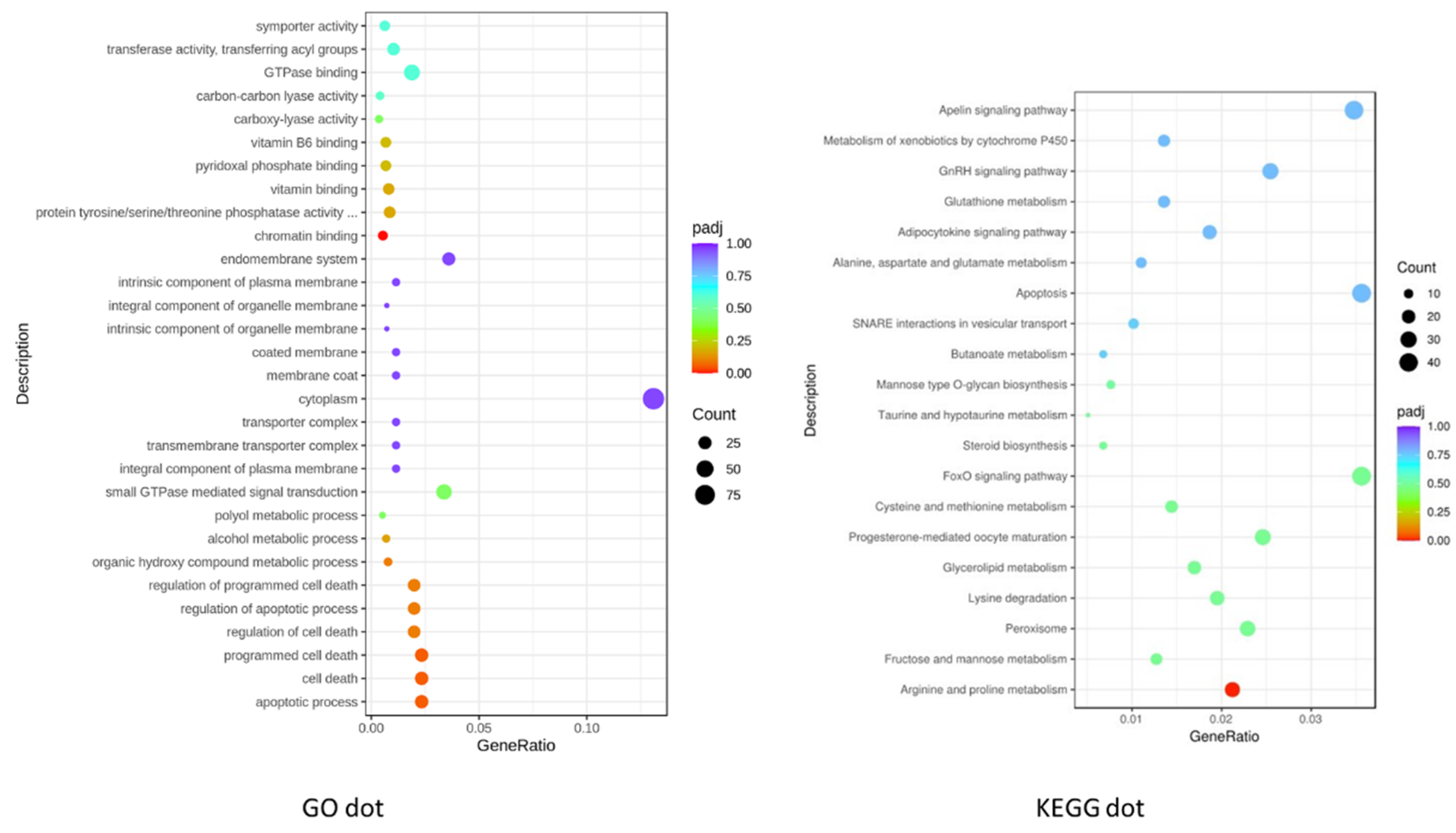

Figure 3A shows the top 30 GO in dot graph.

3.1.4. KEGG Pathway Analysis

We analyzed the biological pathways using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes(KEGG). KEGG is a database resource for understanding high-level functions andutilities of the biological system, such as the cell, the organism and the ecosystem, frommolecular-level information, especially large-scale molecular datasets generated by genomesequencing and other high-through put experimental technologies(

http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). 1101 out of 2190 downregulated DEGs were found in KEGG where 149 pathways were involved at least one Degs. The significant enrichment for pathways in KEGG pathways including metablate, DNA repair and development. 1470 genes out of 2133 up regulated DEGs were found in KEGG where 140 pathways were involved at least one DEGs. The significant KEGG enrichment has Calsium, MAPK, Wnt, Notch, cardiac musclue, and casclar smooth muscle signaling pathways. These pathways are highly consistent with the development of Zebrafish embryos especially during heart development.

Figure 3B shows the top 20 enriched pathways in up and down regulated DEGs.

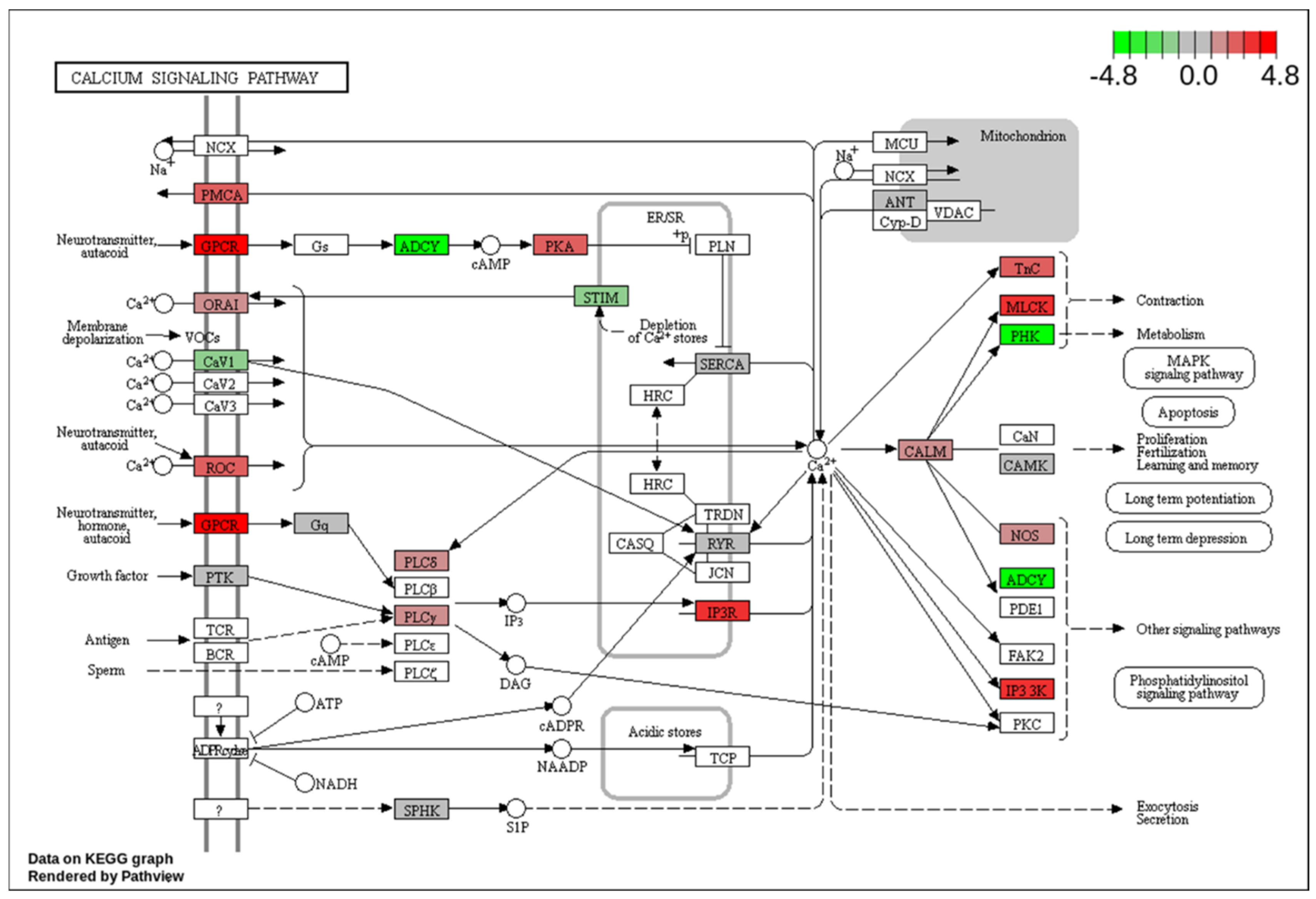

Figure 4 shows the Calcium Signaling Pathway indicating the total 20 up and down regulated genes are involved in this pathway.

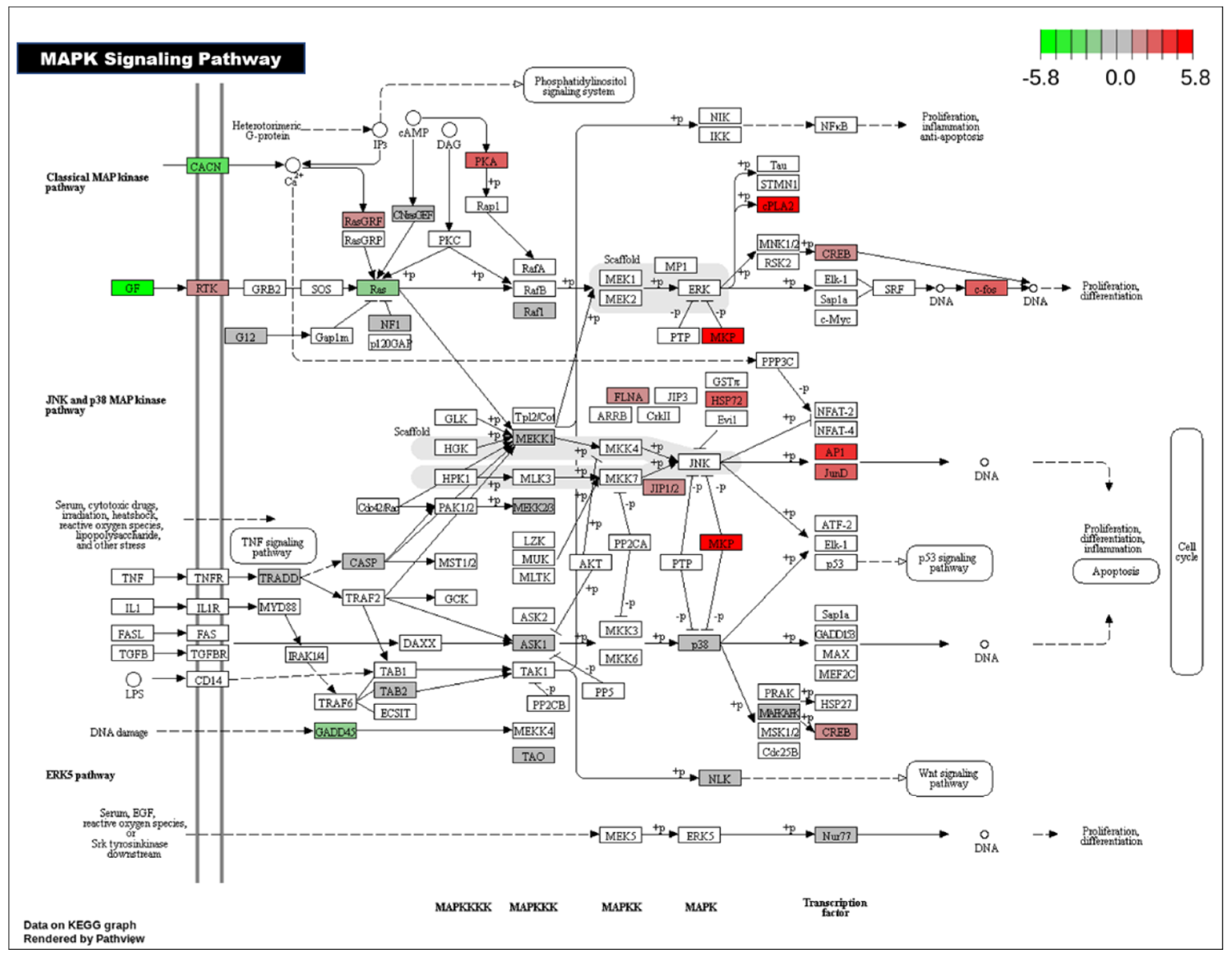

Figure 5 shows the MAPK pathway with altered gene in color.

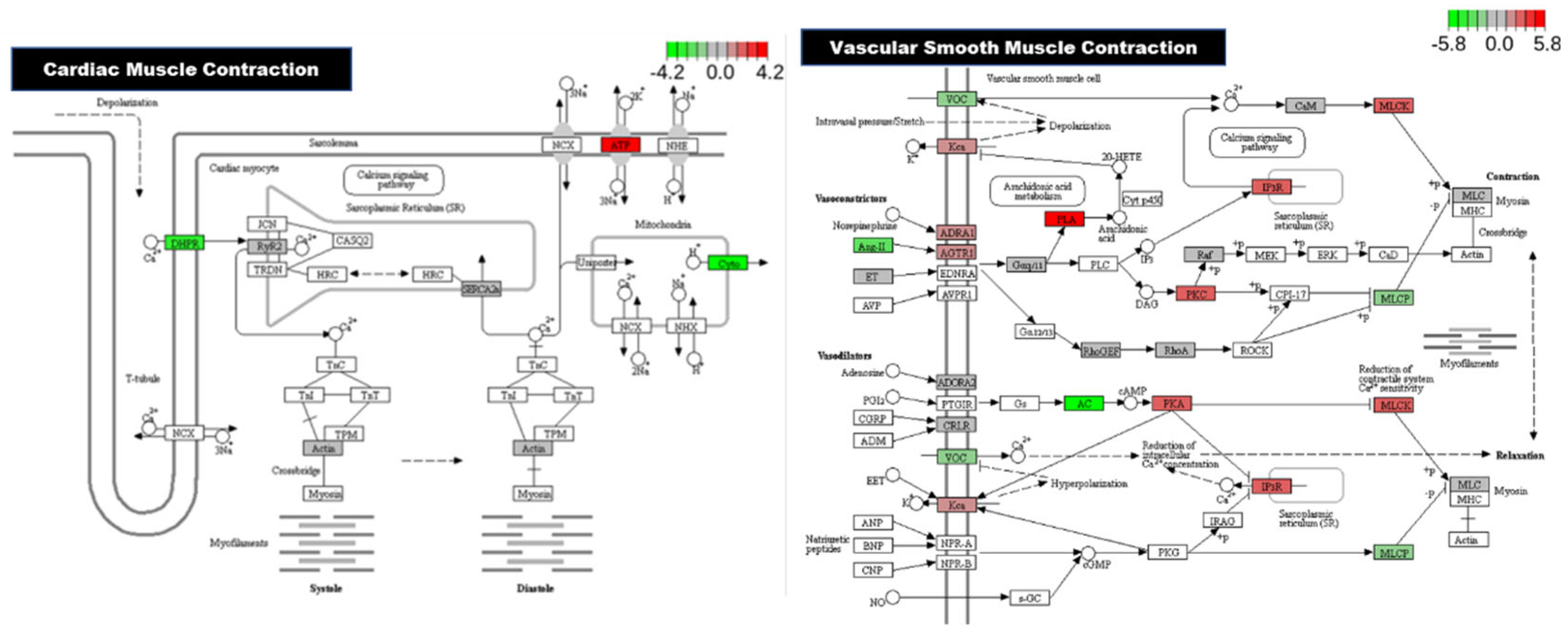

Figure 6 shows cardiac musclular and vascular smooth muscle signaling pathways with identified altered genes.

4. Discussion

Zebrafish embryos offer a valuable model for studying the developmental effects of high salt exposure. A key advantage is that zebrafish embryos can be treated directly with salt solutions, bypassing the placental-fetal barrier that complicates similar studies in mammalian models. This direct exposure enables precise control of the extracellular environment and allows for real-time observation of developmental processes, making zebrafish particularly suited for investigating environmental stressors such as excess sodium on early organogenesis. Given the high degree of conservation in cardiovascular and signaling pathways, findings from salt-exposed zebrafish embryos may provide meaningful insight into how maternal high salt intake impacts fetal development in humans [

32,

33].

Globally, high salt consumption is on the rise, largely driven by increased intake of processed and fast foods. Excessive dietary salt intake is strongly associated with elevated risk for hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, including during pregnancy. Maternal high salt intake has been implicated in adverse outcomes for both mothers and offspring, contributing to long-term health risks such as gestational hypertension and the development of preeclampsia [

8,

10,

24,

34,

35].

Emerging evidence suggests that high salt exposure during pregnancy can lead to increased circulating inflammatory mediators within the placenta, disrupting normal fetal development. These placental changes may contribute to the intrauterine programming of cardiovascular dysfunction, thereby increasing susceptibility to chronic disease later in life [

7,

36].

In this study, we investigated the developmental impact of high salt exposure using a 2% NaCl concentration in zebrafish embryos. Following salt treatment, we observed significant alterations in heart rate, hatching success, and cardiac morphology. Transcriptomic analysis via RNA sequencing further revealed salt-induced differential gene expression, highlighting potential molecular pathways—including calcium signaling and MAPK cascades—that may mediate these phenotypic effects.

The observed delays in hatch rate and alterations in morphological features, particularly in the heart suggest that salt exposure exerts a disruptive effect on zebrafish embryonic development. These findings align with previous studies indicating the susceptibility of developing embryos to cardiovascular disturbances [

18,

37,

38,

39,

40].

The reduced heart rate observed in the glucose-exposed group further underscores the impact of glucose on cardiovascular function during early development [

40].

The molecular mechanisms underlying salt-induced developmental abnormalities require further investigation. It is plausible that salt-mediated disruptions in metabolic processes and signaling cascades contribute to the phenotypic changes observed in zebrafish embryos. In our study, pathway enrichment analysis using RNA-Seq data (data not shown) revealed significant alterations in several pathways known to regulate embryonic development, particularly those related to cardiac formation and function.

Notably, multiple general developmental pathways were dysregulated in salt-treated embryos, including metabolism, Wnt, Notch, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and DNA repair. These findings suggest that high salt exposure broadly influences essential cellular processes critical for normal development.

Among the 149 differentially regulated KEGG pathways identified in the high salt treatment group, 9 of the top 20 were metabolism-related. These included biosynthesis of amino acids, fatty acids, and cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism. Additionally, several signaling pathways involved in developmental regulation were among the most significantly affected, including the apelin, adipocytokine, GnRH, and FoxO signaling pathways. Pathways involved in cell fate determination and communication—such as apoptosis, peroxisome function, and SNARE interactions in vesicular transport—were also impacted. Two biosynthesis-related pathways were prominently enriched in the top 20 results (

Figure 3). These findings underscore the broad systemic effects of high salt exposure on embryonic development and cellular homeostasis.

Together, these pathway alterations highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of salt-induced developmental disruption. They also provide a broader context for our focused investigation into specific signaling cascades. Among these, the calcium signaling and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) adrenergic signaling (data not shown) in cardiomyocytes, and regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathways play important roles for heart normal functions. Therefore, we next examined how high salt exposure modulated gene expression within these pathways.

The MAPK signaling pathway is a highly conserved cascade that plays a pivotal role in regulating numerous cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and stress responses. In the context of cardiac development, MAPK signaling is essential for the proper formation and maturation of the heart. During embryogenesis, it contributes to the specification of cardiac progenitor cells, the proliferation of cardiomyocytes, and the morphogenesis of cardiac chambers and valves. MAPK signaling also facilitates communication between myocardial and endocardial layers, ensuring coordinated development of heart structure and function. In postnatal and adult hearts, the MAPK pathway remains active and is involved in mediating the cardiac response to physiological and pathological stress, such as hypertrophy, ischemia, and pressure overload. Dysregulation of this pathway has been implicated in a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including congenital heart defects, dilated cardiomyopathy, and heart failure [

25,

28,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

In zebrafish, components of the MAPK pathway are expressed early in development, and previous studies have demonstrated that perturbations in MAPK activity can lead to abnormal cardiac morphology and function. Thus, alterations in MAPK signaling in response to environmental stressors such as high salt exposure may underlie some of the developmental cardiac abnormalities observed in this study [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Our data also point to significant involvement of the calcium signaling pathway, which is central to cardio genesis, excitation-contraction coupling, and intracellular signaling in developing embryos. Perturbations in calcium homeostasis—likely triggered by ionic imbalance due to excess sodium—may account for the observed cardiac abnormalities. Our data indicate that upregulation of genes such as GPCR and IP3R in calcium signaling pathway supports the hypothesis that salt stress disrupts normal calcium dynamics, potentially altering cardiac muscle development and function. The cardiac muscle contraction and vascular smooth muscle contraction signaling pathways were significantly altered in the salt-treated group, supporting the conclusion that high salt exposure affects key signaling mechanisms involved in heart development. These changes, along with disruptions observed in the MAPK signaling pathway, suggest a molecular basis for the impaired cardiac development seen in zebrafish embryos under salt stress [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

Together, these findings suggest that high salt exposure affects zebrafish embryonic development through a combination of morphological and molecular mechanisms. The disruption of MAPK and calcium signaling pathways provides a plausible link between environmental salt exposure and developmental programming of cardiovascular outcomes. Given the conservation of these pathways across vertebrates, these results may offer insight into similar mechanisms in mammalian models and underscore the importance of regulating maternal salt intake during pregnancy.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our findings highlight the vulnerability of early vertebrate development to high salt exposure and suggest that perturbations in calcium and MAPK signaling pathways may underlie long-term cardiovascular outcomes associated with maternal salt intake.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. RNA-Seq raw data can be found at NCBI GEO website with ID GSE228661

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T; methodology, R.T.; investigation, R.T.; resources, R.T.; data curation, E.T and J.H; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T., E.T. and J.H; visualization, J.H.; supervision, R.T.; project administration, R.T.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Organization for Research Review Board (RRB) No. 21 according to the regulations of Public Health Service (PHS), the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) and IACUC.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We would like to share the data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Novogene company for conducting the RNA seq and seq data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAPK |

mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| hpf |

hours post fertilization |

| RNA |

ribonucleic acid |

| DEGs |

differentially expressed genes |

References

- Goldsborough, E., 3rd.; Osuji, N.; Blaha, M.J. Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A 2022 Update. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2022, 51, 483–509.

- Mohan, S.; Campbell, N.R.C. Sodium and Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2134–2139. [Google Scholar]

- Whelton, P.K.; Appel, L.J.; Sacco, R.L.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Antman, E.M.; Campbell, N.; Dunbar, S.B.; Van Horn, L.V. Sodium, Blood Pressure, and Cardiovascular Disease: Further Evidence Supporting the AHA Sodium Reduction Recommendations. Circulation 2012, 126, e86–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.J.; Burnier, M.; MacGregor, G.A. Nutrition in cardiovascular disease: salt in hypertension and heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 3073–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Fahimi, S.; Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Engell, R.E.; Lim, S.; Danaei, G.; Ezzati, M.; Powles, J. Global Sodium Consumption and Death from Cardiovascular Causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, S.G. Effects of High Salt Intake on Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease: The Role of COX Inhibitors. Clin. Cardiol. 2016, 39, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asayama, K.; Imai, Y. The Impact of Salt Intake During and After Pregnancy. Hypertens. Res. 2018, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oludare, G.O.; Iranloye, B.O. Implantation and Pregnancy Outcome of Sprague–Dawley Rats Fed with Low and High Salt Diet. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2016, 21, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Liu, R.; Bo, L.; Chen, N.; Li, S.; Xia, S.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z. High-Salt Diets During Pregnancy Affected Fetal and Offspring Renal Renin–Angiotensin System. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 218, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Lv, J.; Mao, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, A.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Z. High-Salt Diet During Pregnancy and Angiotensin-Related Cardiac Changes. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, M, Lin, S. Zebrafish as a Developmental Model Organism for Pediatric Research. Pediatr Res 2008, 64, 470–476. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee D, Park C, Lee H, Lugus JJ, Kim SH, Arentson E, Chung YS, Gomez G, Kyba M, Lin S, Janknecht R, Lim DS, Choi K. ER71 acts downstream of BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling in blood and vessel progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2008, 2, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kudoh T, Tsang M, Hukriede NA, Chen X, Dedekian M, Clarke CJ, Kiang A, Schultz S, Epstein JA, Toyama R, Dawid IB. A gene expression screen in zebrafish embryogenesis. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1979–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsterdam A, Nissen RM, Sun Z, Swindell EC, Farrington S, Hopkins N. Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 12792–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- White RJ, Collins JE, Sealy IM, Wali N, Dooley CM, Digby Z, Stemple DL, Murphy DN, Billis K, Hourlier T, Füllgrabe A, Davis MP, Enright AJ, Busch-Nentwich EM. A high-resolution mRNA expression time course of embryonic develop-ment in zebrafish. Elife 2017, 6, e30860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parichy, D.M., Elizondo, M.R., Mills, M.G., Gordon, T.N., Engeszer, R.E. Normal table of postembryonic zebrafish development: Staging by externally visible anatomy of the living fish. Dev. Dyn. 2009, 238, 2975–3015. [CrossRef]

- Ord, J. Ionic Stress Prompts Premature Hatching of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos. Fishes 2019, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, M.S.; Zhang, S.; Li, L. Effect of salinity on development of zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. Curr. Sci. 2001, 81, 1347–1350.11. Lundin, E.A.; Zhang, J.; Kramer, M.S.; Klebanoff, M.A.; Levine, R.J. Maternal Diet and Hypertension in Pregnancy Among Nulliparous Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 786–793. [Google Scholar]

- Micou, S.; Forner-Piquer, I.; Cresto, N.; Zassot, T.; Drouard, A.; Larbi, M.; Mangoni, M.E.; Audinat, E.; Jopling, C.; Faucherre, A.; Marchi, N.; Torrente, A.G. High-speed optical mapping of heart and brain voltage activities in zebrafish larvae exposed to environmental contaminants. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 31, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seli, D.A.; Prendergast, A.; Ergun, Y.; Tyagi, A.; Taylor, H.S. High NaCl Concentrations in Water Are Associated with Developmental Abnormalities and Altered Gene Expression in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelnour, S.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Noreldin, A.E.; Batiha, G.E.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Ohran, H.; Khafaga, A.F.; Othman, S.I.; Allam, A.A.; Swelum, A.A. High Salt Diet Affects the Reproductive Health in Animals: An Overview. Animals 2020, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Huang, L.; Pan, J.; Yao, J.; Du, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, J. Maternal high salt-diet increases offspring’s blood pressure with dysfunction of NO/PKGI signaling pathway in heart tissue. Gynecol. Obstet. Clin. Med. 2022, 2, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, M.P.; Rodrigues, S.L.; Mill, J.G. High salt intake as a multifaceted cardiovascular disease: new support from cellular and molecular evidence. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 461–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardwell, L. Mechanisms of MAPK signalling specificity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslin, A.J. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2008, 115, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Etzion, S.; Elyagon, S.; Shahar, M.; Klapper-Goldstein, H.; Levitas, A.; Kapiloff, M.S.; Parvari, R.; Etzion, Y. Dock10 Regulates Cardiac Function under Neurohormonal Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.; Hensley, J.; Taylor, R.S. Effect of High Glucose on Embryological Development of Zebrafish, Brachyodanio, Rerio through Wnt Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, S.; Ruan, J.; Pan, H.; Ma, M.; Huang, G.; Ji, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, T. Inhibiting the MAPK pathway improves heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induced by salt-sensitive hypertension. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 115987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammer E, Carr GJ, Wendler K, Rawlings JM, Belanger SE, Braunbeck T. Is the fish embryo toxicity test (FET) with the zebrafish (Danio rerio) a potential alternative for the fish acute toxicity test? Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009, 149, 196–209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Lee JE, Dorsky RI. Identification of Wnt-responsive cells in the zebrafish hypothalamus. Zebrafish 2009, 6, 49–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akieda Y, Ogamino S, Furuie H, Ishitani S, Akiyoshi R, Nogami J, Masuda T, Shimizu N, Ohkawa Y, Ishitani T. Cell competition corrects noisy Wnt morphogen gradients to achieve robust patterning in the zebrafish embryo. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 4710. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Panth, N.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.-H.; Oak, M.-H. Protective Effect of Salicornia europaea Extracts on High Salt Intake-Induced Vascular Dysfunction and Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.; Visser, M.E.; Schoonees, A.; Naude, C.E. Replacing Salt with Low-Sodium Salt Substitutes (LSSS) for Cardiovascular Health in Adults, Children, and Pregnant Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 8, CD015207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, S.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Noreldin, A.E.; Batiha, G.E.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Ohran, H.; Khafaga, A.F.; Othman, S.I.; Allam, A.A.; Swelum, A.A. High Salt Diet Affects the Reproductive Health in Animals: An Overview. Animals 2020, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-xin Xu, Shu-hui Zhang, Shao-zhi Zhang, Meng-ying Yang, Xin Zhao, Ming-zhu Sun, Xi-zeng Feng. Exposure of zebrafish embryos to sodium propionate disrupts circadian behavior and glucose metabolism-related development. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2022, 241, 113791. [CrossRef]

- Sawant, M.S.; Zhang, S.; Li, L. Effect of salinity on development of zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. Current Science 2001, 81, 1347–1350, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:82982366. [Google Scholar]

- Varatharajan, S.; Dixit, S.D. Effects of Sodium Chloride on Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryonic Development and Analysis of the Zebrafish Embryo using ImageJ software. Int. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Forner-Piquer, I.; Cresto, N.; Drouard, A.; Mangoni, M.E.; Audinat, E.; Jopling, C.; Faucherre, A.; Marchi, N.; Torrente, A.G. High-speed optical mapping of heart and brain voltage activities in zebrafish larvae exposed to environmental contaminants. Environmental Technology and Innovation 2023, 31, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslin, A.J. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2008, 115, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ocaranza, M.P.; Jalil, J.E. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases as Biomarkers of Hypertension or Cardiac Pressure Overload. Hypertension 2010, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; He, J.Q. Common differentially expressed genes and pathways correlating both coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Streicher, J.M.; Ren, S.; Herschman, H.; Wang, Y. MAPK-Activated Protein Kinase-2 in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Cyclooxygenase-2 Regulation in Heart. Circulation Research 2010, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, D. The Role of the MAPK Signaling Pathway in Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Clinical Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Ding, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, P.; Shih, Y.H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Xu, X. Inhibition of mTOR or MAPK ameliorates vmhcl/myh7 cardiomyopathy in zebrafish. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e154215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, P.; Zhong, T.P. MAPK/ERK signalling is required for zebrafish cardiac regeneration. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 39, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Hu, G. Bmp4 in Zebrafish Enhances Antiviral Innate Immunity through p38 MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases) Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Missinato, M.A.; Saydmohammed, M.; Zuppo, D.A.; Rao, K.S.; Opie, G.W.; Kühn, B.; Tsang, M. Dusp6 attenuates Ras/MAPK signaling to limit zebrafish heart regeneration. Development 2018, 145, dev157206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Segal, L.; Etzion, S.; Elyagon, S.; Shahar, M.; Klapper-Goldstein, H.; Levitas, A.; Kapiloff, M.S.; Parvari, R.; Etzion, Y. Dock10 Regulates Cardiac Function under Neurohormonal Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Chu, L. [8]-Gingerol exerts anti-myocardial ischemic effects in rats via modulation of the MAPK signaling pathway and L-type Ca2+ channels. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, M.; Xie, X.; Chen, H.; Xiong, Q.; Tong, R.; Peng, C.; Peng, F. Aconitine induces cardiotoxicity through regulation of calcium signaling pathway in zebrafish embryos and in H9c2 cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2020, 40, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ao, S.; Zhou, C.; Hou, L.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, K.; Xia, Q. Narcissin induces developmental toxicity and cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos via Nrf2/HO-1 and calcium signaling pathways. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Kong, H.; Shen, C.; She, G.; Tian, S.; Liu, H.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Xia, Q.; Liu, K. Dimethyl phthalate induced cardiovascular developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos by regulating MAPK and calcium signaling pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Guo, S.; Miao, N. Transcriptional responses of fluxapyroxad-induced dysfunctional heart in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 90034–90045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Meng, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhong, K.; Cao, Z.; Liao, X.; Lu, H. Famoxadone-cymoxanil induced cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 205, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).