Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Specimen Collection

2.2. Acclimation and Feeding

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Experiment 1: Juveniles

2.5. Experiment 2: Adults

2.6. Gonadal Histological Evaluation

2.7. Plasma 11-KT and Vtg Concentrations

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis in Juveniles

2.9. Zootechnical Performance and Water Quality

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Juveniles

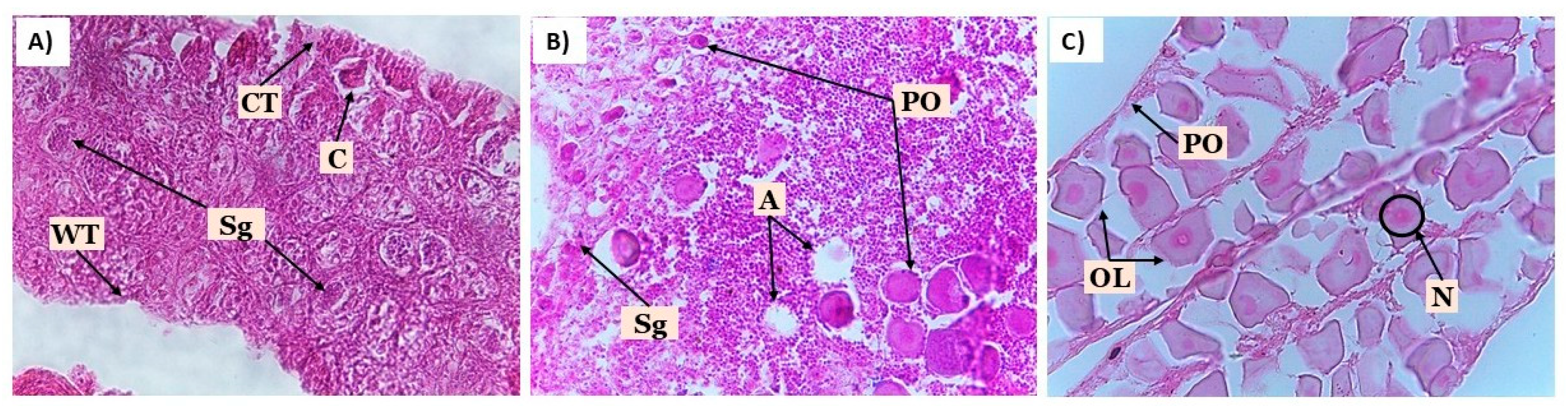

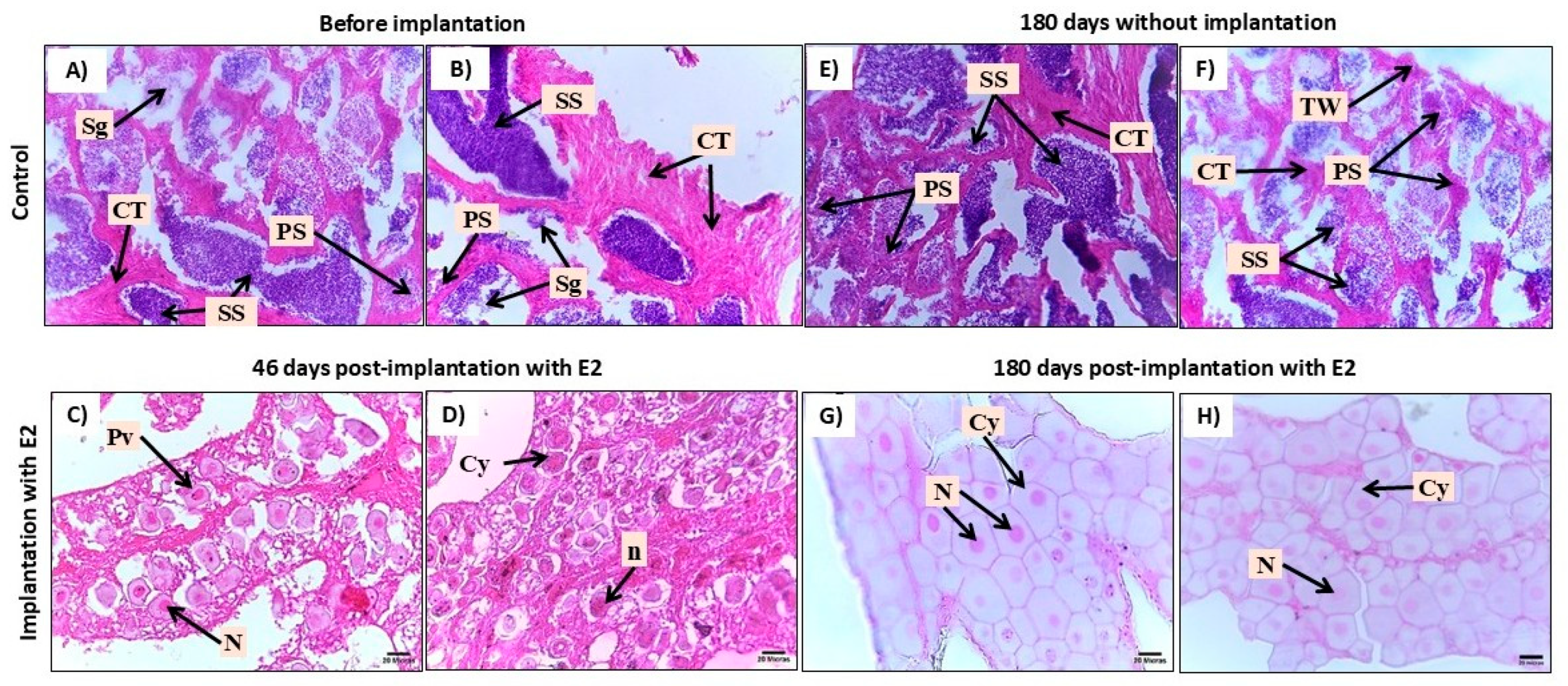

3.1.1. Histological Evaluation of Gonadal Development

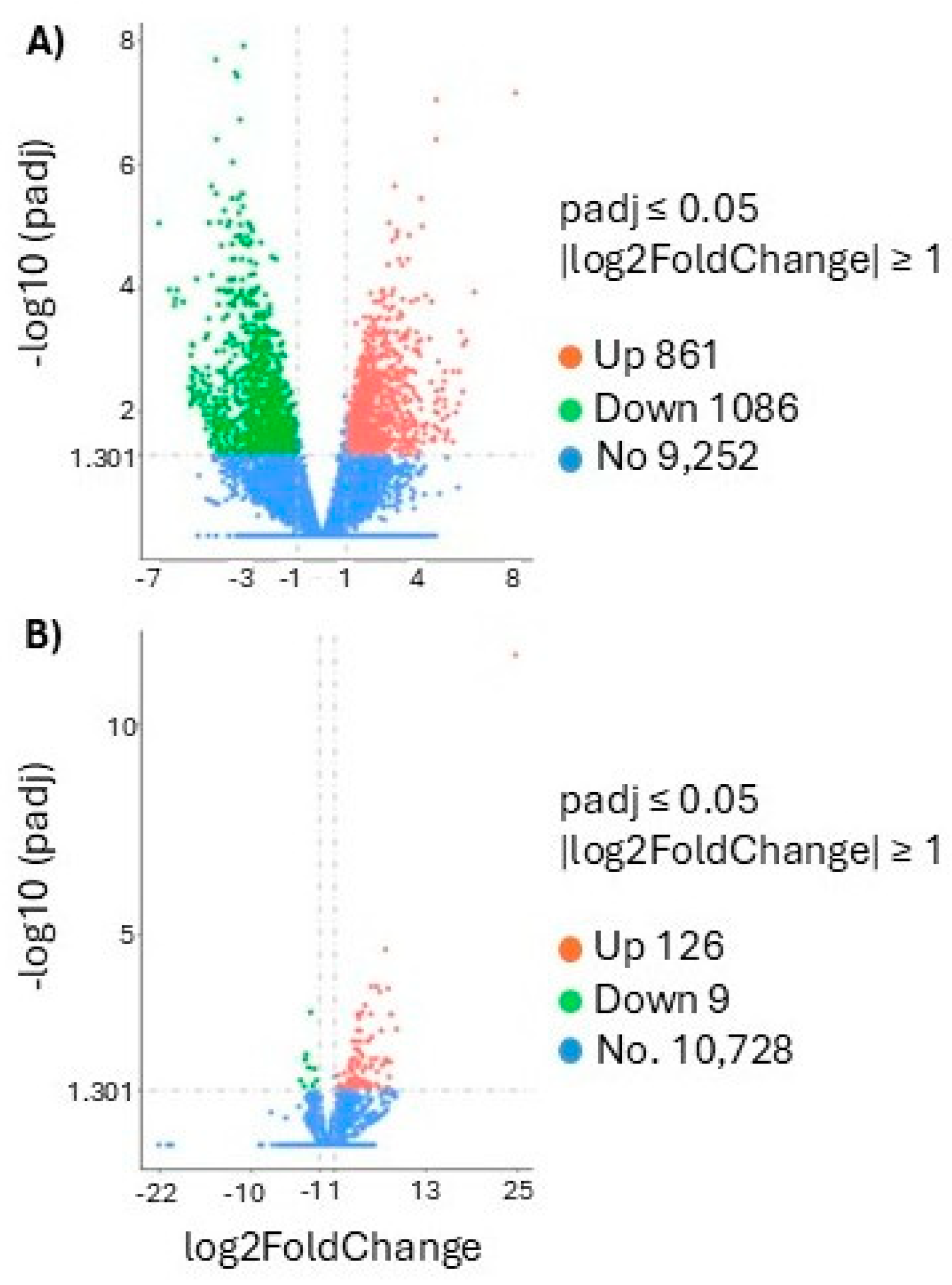

3.1.2. Gene Expression Associated with Sexual Processes and Gonadal Development in Feminized Juveniles of Centropomus undecimalis

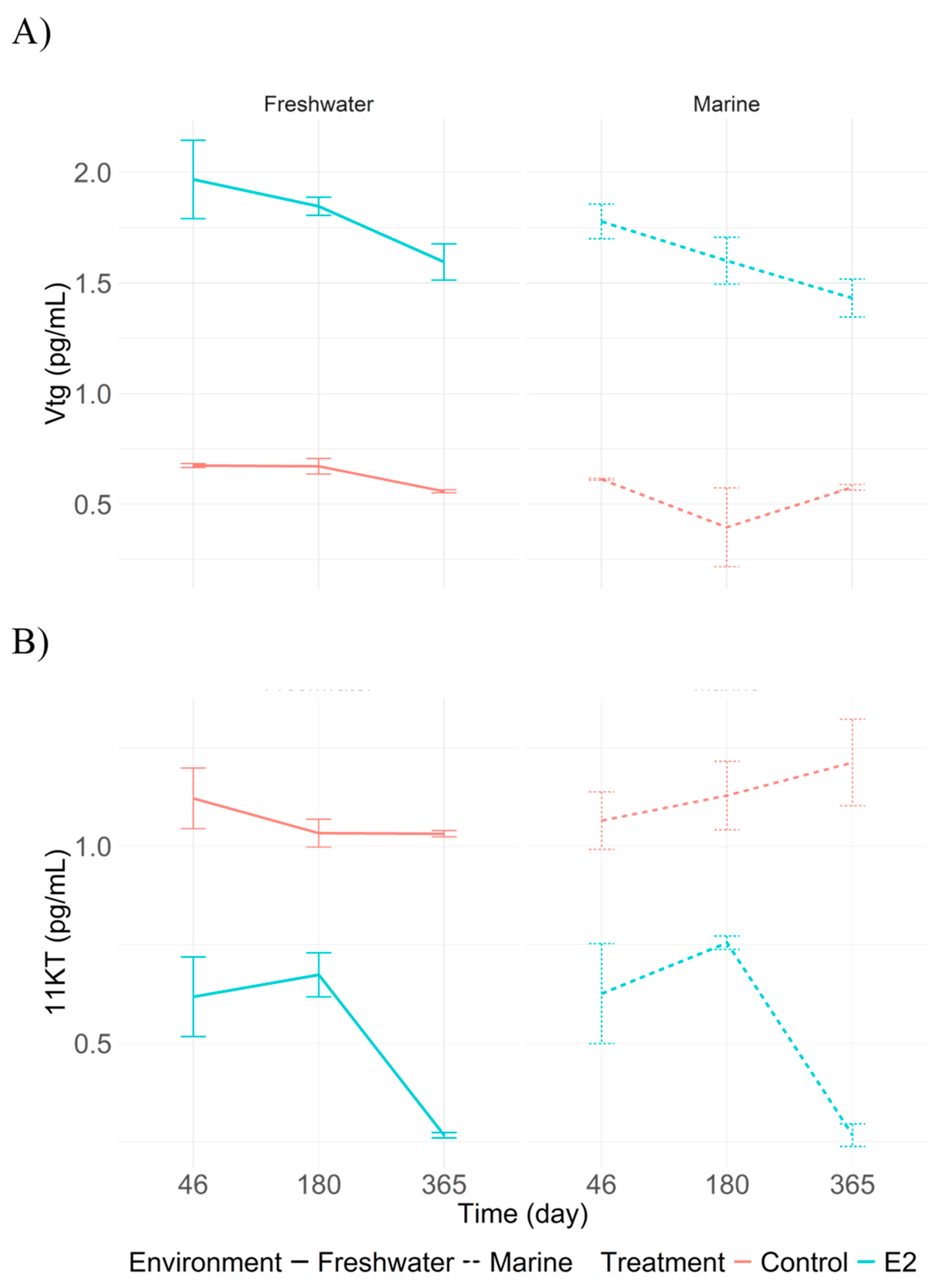

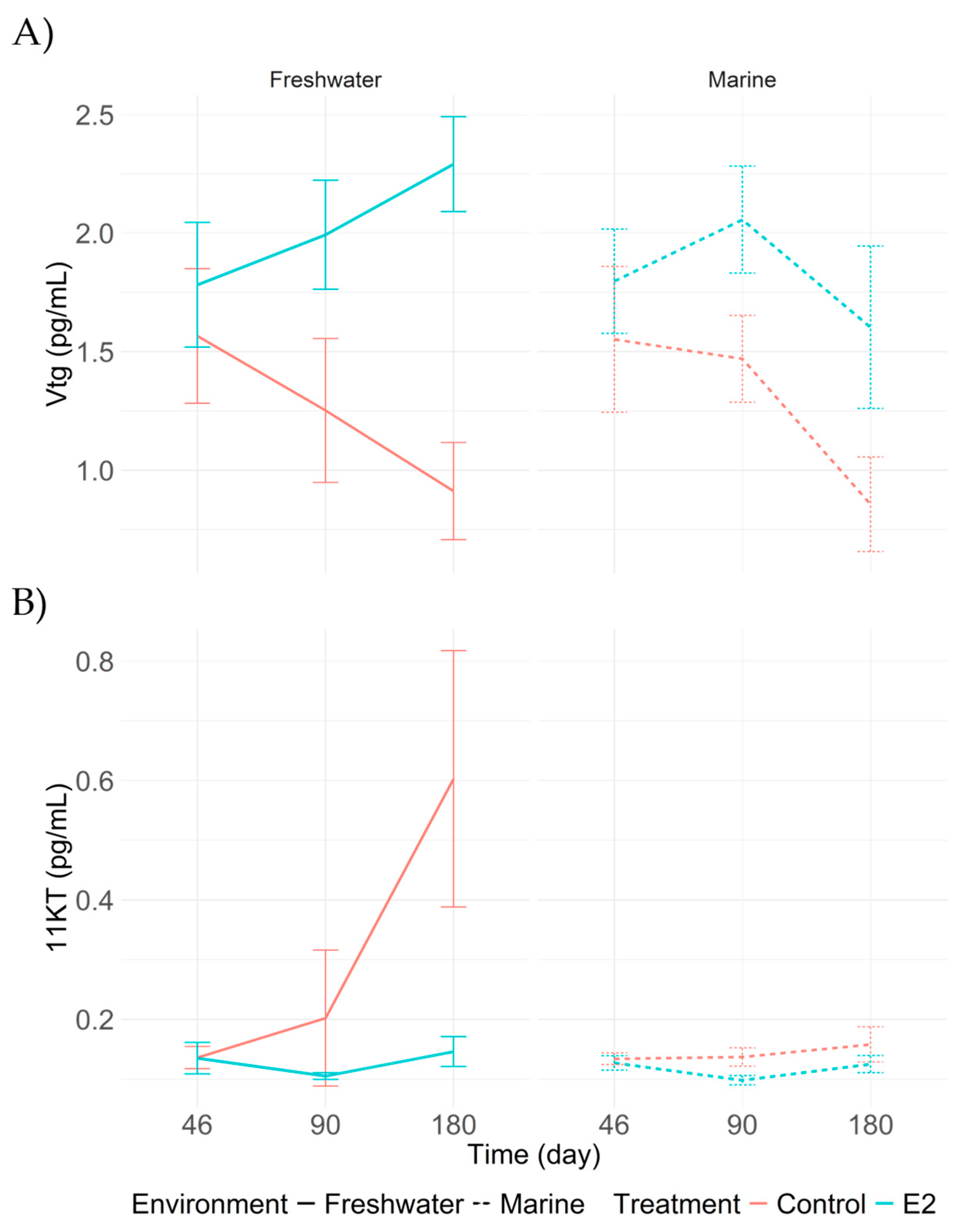

3.1.3. Plasma 11-KT and VTG Levels in Juvenile Centropomus undecimalis

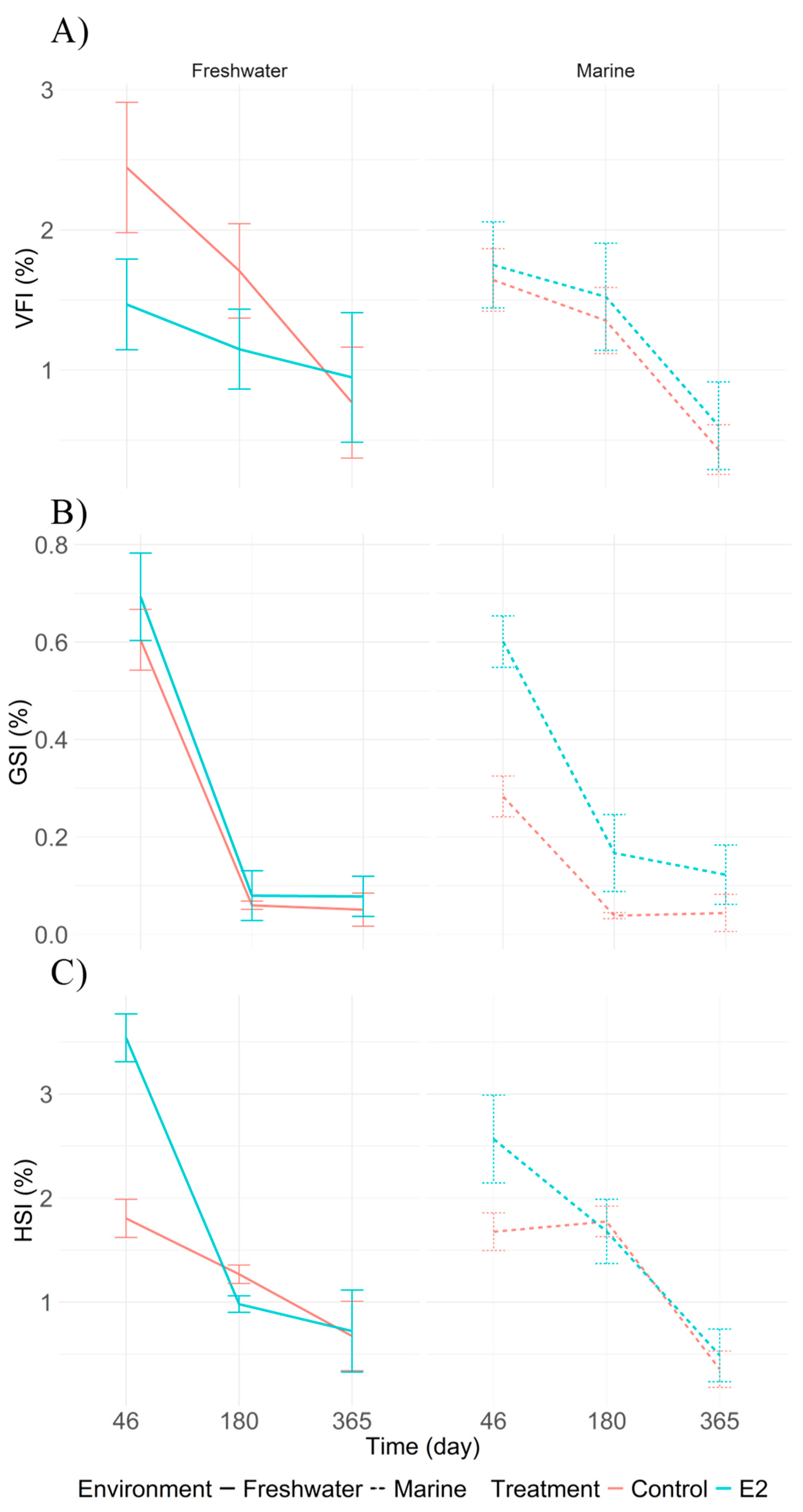

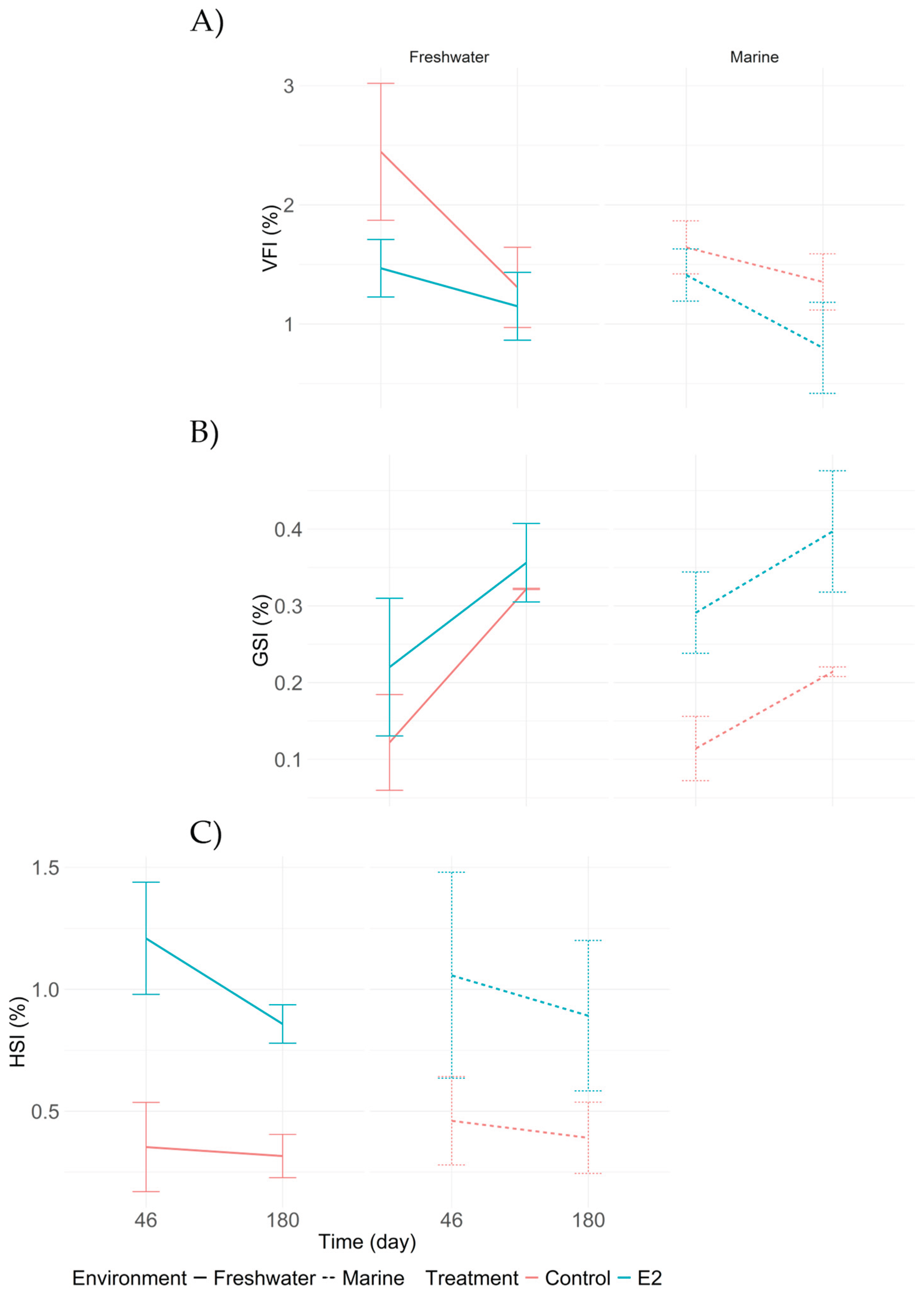

3.1.4. Visceral Fat, Gonadosomatic, and Hepatosomatic Indices in Juvenile Centropomus undecimalis

3.1.5. Growth Performance Indicators in Juvenile Centropomus undecimalis

3.2. Experiment 2: Adults

3.2.1. Histological Observation of Gonads in Centropomus undecimalis

3.2.2. Plasma Levels of Vitellogenin (Vtg) and 11-Ketotestosterone (11-KT) in Adult Centropomus undecimalis

3.2.3. Visceral Fat, Gonadosomatic, and Hepatosomatic Indices in Adult Centropomus undecimalis

3.2.4. Growth Performance Indicators in Adult Centropomus undecimalis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piferrer, F. Endocrine sex control strategies for the feminization of teleost fish. Aquaculture 2001, 197, 229–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-García, M.; Contreras-Sánchez, W.M.; Mendoza-Carranza, M.; Mcdonal-Vera, A.; Cruz-Rosado, L. Induced Sex Reversal in Adult Males of the Protandric Hermaphrodite Centropomus undecimalis Using 17 β-Estradiol. Aquac. J. 2023, 3, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Passini, G.; Melo-Costa, W.; Nunes-Vieira, B.; Ronzani-Cerqueira, V. Effect of estradiol-17β on the sex ratio, growth and survival of juvenile common snook (Centropomus undecimalis). Acta Sci. Anim. Sci. 2014, 36, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passini, G.; Sterzelecki, F.C.; De Carvalho, C.V.A.; Cerqueira, V.R. Induction of sex inversion in common snook (Centropomus undecimalis) males using 17-β estradiol implants. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.B.; Duarte, L.O.; Altamar, J.; Manjarrés, L.M. Demersal fish density in the upwelling ecosystem off Colombia, Caribbean Sea: Historic outlook. Fish. Res. 2007, 85, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Ibarra, S.; Villamizar-Villamizar, N. Piscicultura marina del róbalo (Centropomus undecimalis); Editorial Unimagdalena: Santa Marta, Colombia, 2024; 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-Chávez, J. Revisión de aspectos biológicos y pesqueros del róbalo (Centropomus undecimalis). Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Pecu. 2011, 24, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Flores, J.; Ibarra-Castro, L.; Martinez-Brown, J.M.; Zavala-Leal, O.I. Hermaphroditism in teleost fishes and their implications in commercial aquaculture. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2019, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalba-Bendeck, M.; Leal-Flórez, J.; Bolaños-Cubillos, N.; Acero, A. Centropomus undecimalis. In Libro Rojo de Peces Marinos de Colombia; INVEMAR: Santa Marta, Colombia, 2017; pp. 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-López JM, Álvarez-González CA, Sánchez WM, Patiño R, Hernández-Franyutti AA, Hernández-Vidal U, García RM. Feminización de juveniles del Robalo Blanco Centropomus undecimalis (Bloch 1792) usando 17β-estradiol. Revista Ciencias Marinas y Costeras. 2012, 4:83-93. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? 6337.

- Navarro-Flores, J.; Manuel, M.B.J.; Iram, Z.L.; Humberto, R.C.A.; Leonardo, I.C. Assessing the feasibility of exogenous 17β-estradiol for inducing sex change in white snook, C. viridis: From growth, resting and maturation studies. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.; Cocquet, J.; Xia, X.; Fellous, M.; Guiguen, Y.; Veitia, R.A. An evolutionary and functional analysis of FoxL2 in rainbow trout gonad differentiation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 33, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui H, Zhu H, Ban W, Li Y, Chen R, Li L, Zhang X, Chen K, Xu H. Characterization of Two Gonadal Genes, zar1 and wt1b, in Hermaphroditic Fish Asian Seabass (Lates calcarifer). Animals 2024, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, R.; Taimatsu, K.; Ohga, R.; et al. Critical roles of the ddx5 gene in zebrafish sex differentiation and oocyte maturation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vidal, U.; Chiappa-Carrara, X.; Contreras-Sánchez, W.M. Reproductive variability of the common snook, Centropomus undecimalis, in environments of contrasting salinities. Cienc. Mar. 2012, 40, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, C.C.; et al. Growth performance and osmoregulation in the shi drum (Umbrina cirrosa) adapted to different environmental salinities. Aquaculture 2009, 287, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, C.A.; Buckley, B.A. Transcriptomic responses to environmental temperature in eurythermal and stenothermal fishes. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banh, Q.Q.T.; Domingos, J.A.; Pinto, R.C.C.; et al. Dietary 17β-estradiol and 17α-ethinyloestradiol alter gonadal morphology and gene expression in juvenile barramundi (Lates calcarifer). Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 3415–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yue, H.M.; Chen, B.; Gui, J.F. Histone H2A Has a Novel Variant in Fish Oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Shen, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Gene expression of Takifugu rubripes gonads during AI-or MT-induced masculinization and E2-induced feminization. Endocrinology. 2021, 162, bqab068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonía-Rivera, C.; Gaitán, S.; Chaparro-Muñoz, N.; Villamizar, N. Captura, transporte y aclimatación de juveniles y adultos de róbalo Centropomus undecimalis. Rev. Intropica. 2017, 12, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Sánchez, W.M. Manual para la producción de róbalo blanco: Centropomus undecimalis en cautiverio; UJAT: Villahermosa, México, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. American Veterinary Medical Association. Recuperado el 3 de abril de 2024, de https://www.avma.

- Luna, H. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 3rd, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Eds.) ; American Registry of Pathology: New York, NY, USA, 1968.

- Brown-Peterson, N.J.; Wyanski, D.M.; Saborido-Rey, F.; et al. A standardized terminology for describing reproductive development in fishes. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2011, 3, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Yeiser, B.G.; Whittington, J.A.; Dutka-Gianelli, J. Maturation of female common snook Centropomus undecimalis: Implications for managing protandrous fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.P.; Ellis, T. Measurement of fish steroids in water: A review. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 153, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; et al. HISAT2: Graph-based alignment of next-generation sequencing reads. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology. 2015, 33(3):290-5.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. , Wang, LG., Han, Y., He, QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics: a journal of integrative biology. 2012, 1;16(5):284-7. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Zhang W, Dan Z, Zhuang Y, Liu Y, Mai K and Ai Q (2022), Replacement of dietary fish meal with Clostridium autoethanogenum meal on growth performance, intestinal amino acids transporters, protein metabolism and hepatic lipid metabolism of juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Front. Physiol. 13:981750. [CrossRef]

- Sadekarpawar, S. , Parikh, P. ( 8(1), 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Sokal, RR. The principles and practice of statistics in biological research. Biometry. 1995, 451–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zar, JH. Dichotomous variables. Biostatistical Analysis 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 2010, 557-8.

- Baroiller, J.F.; Guiguen, Y.; Fostier, A. Endocrine and environmental aspects of sex differentiation in fish. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999, 55, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, T.J.; Sheela, S.G. Hormonal induction of sex reversal in fish. Aquaculture 1995, 138, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, R.H.; Nagahama, Y. Sex determination and sex differentiation in fish: An overview of genetic, physiological, and environmental influences. Aquaculture 2002, 208, 191–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-López, J. M. , Contreras-Sánchez, W. M., Hernández-Franyutti, A., Contreras-García, M. D. J., & Uribe-Aranzábal, M. D. C. (2019). Functional feminization of the Mexican snook (Centropomus poeyi) using 17β-estradiol in the diet. Latin american journal of aquatic research, 47(2), 240-250.

- Contreras-García, M. J. , Contreras-Sánchez, W. M., Mendoza-Carranza, M., De La Cruz-Hernández, E. N., Mcdonal-Vera, A., & Hernández-Vidal, U. (2025). Gene expression, gonadal morphology, and steroid hormone profiles during induced sex-change in the protandric hermaphrodite Centropomus undecimalis. Aquaculture, 604, 742429.

- Vizziano-Cantonnet, D.; Baron, D.; Randuineau, G.; Guiguen, Y. Characterization of early molecular sex differentiation in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Dev. Dyn. 2007, 236, 2198–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, C.C.; Fostier, A.; Zanuy, S. Broodstock management and hormonal manipulations of fish reproduction. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, M.; Zanuy, S.; Carillo, M.; Piferrer, F. Effects of rearing temperature on the sex differentiation of the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). J. Exp. Zool. 1998, 281, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, I.; Estévez, A.; Zanuy, S.; et al. Environmental sex determination in the sea bream (Sparus aurata L.): Relationship between growth and sex. Aquaculture 2007, 263, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C.R.; van der Eerden, B.; Jobling, S.; Panter, G.; Sumpter, J.P. Measurement of vitellogenin in male fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) as a biomarker for estrogenic exposure. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1999, 18, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arukwe, A.; Goksøyr, A. Eggshell and egg yolk proteins in fish: Hepatic expression, synthetic control and use as biomarkers of estrogenic compounds. Mar. Environ. Res. 2003, 55, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.M.; Kille, P.; Tyler, C.R. Gene expression and molecular responses in fish: Integration with ecotoxicology and endocrine disruption. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 152, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, A.; Hiramatsu, N.; Fujita, T. Vitellogenesis and choriogenesis in fishes. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 42, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filby, A.L.; Thorpe, K.L.; Tyler, C.R. Multiple molecular effect pathways of an environmental oestrogen in fish. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 37, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passini, G.; Sterzelecki, F.C.; De Carvalho, C.V.A.; Baloi, M.F.; Naide, V.; Cerqueira, V.R. 17α-Methyltestosterone implants accelerate spermatogenesis in common snook, Centropomus undecimalis, during first sexual maturation. Theriogenology 2018, 106, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, Y.Y.; Lokman, P.M.; Damsteegt, E.L.; Closs, G.P.; Young, G. Sex identification in captive hapuku (Polyprion oxygeneios) using plasma levels of vitellogenin and sex steroids. Aquaculture. [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Vera, M.T.; Rodríguez-Pulido, J.A.; Góngora-Orjuela, A. ¿Qué sabemos de los esteroides sexuales y las gonadotropinas en la reproducción de teleósteos neotropicales? Orinoquia 2020, 24, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Yeiser, B.G.; Whittington, J.A.; Dutka-Gianelli, J. Maturation of female common snook Centropomus undecimalis: Implications for managing protandrous fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 97, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, C.V.A.; Passini, G.; De Melo Costa, W.; Cerqueira, V.R. Feminization and growth of juvenile fat snook Centropomus parallelus fed diets with different concentrations of estradiol-17β. Aquac. Int. 2014, 22, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lajonchère, L.; Hernández-Molejón, O.G. Producción de juveniles de peces estuarinos para un Centro en América Latina y el Caribe: diseño, operación y tecnologías. World Aquaculture Society, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Lajonchère, L.; Tsuzuki, M.Y. A review of methods for Centropomus spp. (snooks) aquaculture and recommendations for the establishment of their culture in Latin America. Aquac. Res. 2008, 39, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-López, V.; Rosas-Vázquez, C.; Brito-Pérez, R. Effects of salinity on physiological conditions in juvenile common snook Centropomus undecimalis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2006, 145, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | p-Value | log2FoldChange | ||

| T1 vs T3 | T2 vs T4 | |||

| zar1l | 0.001 | 246829734073046 | ||

| foxl2a | 0.001 | 651651063065463 | ||

| ddx5 | 0.001 | 401534593566732 | ||

| H2A | 0.009 | 306331524924077 | ||

| ddx5 | 0.001 | 307831256725416 | ||

| H2A | 0.001 | 261544452401545 | ||

| Parameters | Treatments | |||

|

T1 (E2-marine) |

T2 (E2-freshwater) |

T3 (marine) |

T4 (freshwater) |

|

| AGR (g/day) | 0.25±0.02 | 0.36±0.06 | 0.24±0.02 | 0.52±0.08 |

| ALG. (cm/day) | 0.03±0.01 | 0.03±0.00 | 0.02±0.00 | 0.04±0.01 |

| SGR (%/day) | 0.39±0.04a | 0.64±0.05ab | 0.38±0.04a | 0.734±0.051b |

| FCR | 8.85±0.69a | 5.68±0.56bc | 8.47±0.62ab | 4.90±0.47bc |

| FER | 12.19±1.98a | 18.94±2.56ab | 12.53±2.14a | 21.43±2.73b |

| PER | 0.205±0.02a | 0.320±0.01bc | 0.215±0.02ab | 0.370±0.05c |

| S (%) | 71 | 67 | 68 | 77 |

| Parameters | Treatments | |||

|

T1 (E2-Marine) |

T2 (E2-Freshwater) |

T3 (Marine) |

T4 (Freshwater) |

|

| AGR (g/day) | 1.031±0.33 | 0.615±0.31 | 1.186±0.14 | 0.980±0.39 |

| ALG (cm/day) | 0.016±0.00 | 0.013±0.00 | 0.029±0.01 | 0.024±0.00 |

| SGR (%/day) | 0.163±0.06 | 0.081±0.04 | 0.193±0.02 | 0.153±0.06 |

| FCR | 3.100±0.51 | 3.933±0.63 | 3.080±0.42 | 3.624±0.82 |

| FER | 0.342±0.05 | 0.269±0.04 | 0.336±0.04 | 0.317±0.09 |

| PER | 0.624±0.10 | 0.492±0.08 | 0.615±0.07 | 0.579±0.16 |

| S (%) | 68a | 95b | 73a | 98b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).