1. Introduction

In the last decades, methanol application as an alternative efficient and ecological fuel for gas turbines, vehicles and fuel cells gains a considerable interest [

1]. Methanol decomposition to hydrogen and carbon monoxide is one of the promising ways in this aspect [

2,

3]. Decomposed methanol fuel could be up to 60% more efficient than gasoline and up to 34% better than undecomposed methanol. Significant reduction of the CO, hydrocarbons and NOx emission in the experimental vehicles, burning the decomposed methanol, is established as well [

4,

5]. Methanol decomposition also seems to be suitable for application as an efficient heat pump in the industry [

6,

7].

A number of studies are being conducted worldwide on the synthesis of activated carbons from various raw materials, mainly focused on their use as adsorbents and catalyst supports. Today, many efforts are directed towards reducing the high cost of activated carbons, using various methods for their preparation based on various waste products as raw materials [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Activated carbons have a heterogeneous micro/mesoporous structure, as well as controllable chemical properties of the surface due to the presence of various acidic and basic surface functional groups. Surface functional groups reduce the hydrophobic properties of the surface of the activated carbon, play the role of active centers or participate in the reaction by a bifunctional mechanism [

13]. There are many studies that show that the properties of activated carbons can be successfully regulated by the type of raw material and synthesis conditions, as well as by additional treatment with various oxidizing agents. As a catalyst support, activated carbon has many advantages, such as high surface area, tunable pore structure and surface chemistry, resistance to acidic or basic media, stability at high temperatures in inert or reduction atmosphere, as well as ability to recover the supported active metals [

14,

15,

16]. Activated carbon structure is developed by imperfect aromatic sheets of carbon atoms, as well as incompletely saturated valences and unpaired electrons on the surface [

12]. This determines high adsorption capacity of carbon materials, especially towards polar or polarizable molecules. The surface functional groups, formed as a result of thermal or chemical treatments, influence the acid–base properties of carbon surface and could be considered as potential active sites for adsorption and catalysis [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

At the same time, ceria is one of the most used metal oxides in various catalytic applications due to its intrinsic redox ability. If the size of its building crystallites decreases deep in the nanometer scale an increase in their specific reactivity is expected to be registered. At the same time, the combination of nanostructured metal oxide with carbon materials (nanodiamond or graphene oxide) would lead to the formation of a nanocomposite hybrid material with improved textural and chemical functionality [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Besides the expected increase in the specific surface area of the hybrid materials, the presence of oxygen-containing groups within the carbon component would ensure good bonding and interfacial interactions with the metal oxide component that would prevent agglomeration processes and could lead to the occurrence of synergistic effects, and hence to the appearance of new properties that differ from those of the individual components.

Nanosized single and double metal oxides allow their wide application in various fields due to their high activity and unusual electronic, optical and magnetic properties. Among the new generation adsorbents and catalysts, magnetic nanomaterials are distinguished by high specific surface area, controllable morphology, high efficiency and the possibility of easy separation. There is evidence of the use of ferrites for the removal of phenol [

25], phosphorus compounds [

26], antibiotics [

27] (tetracycline [

28] and oxytetracycline [

29]) from water, methanol decomposition [

30,

31], etc. It has been established that the adsorption of pollutants on ferrites and their composites is mainly determined by the occurrence of hydrogen bonding, π-π interaction, surface complexation, electrostatic interaction, chemisorption or ion exchange. Spinel ferrites can accumulate oxygen vacancies in their structure. This facilitates the exchange of oxygen with the environment at high temperatures, making them attractive for catalytic purposes [

32]. In the spinel structure, metal cations are 4- or 6-coordinated with oxygen ions, forming tetrahedral (A) or octahedral (B) sublattices arranged in close packing. Changes in the nature of the metal ion and the distribution of ions in the A and B positions are a simple way to control the properties of spinel ferrites [

33,

34,

35]. This can be achieved by varying the metal ion, changing the dispersion of the ferrite particles, or by depositing them on different supports.

The aims of this paper are:

i) To obtain activated carbons from spent motor oil with different surface and texture features due to variation in the additional precursor;

ii) To investigate the role of the addition of two different carbon components (nanodiamond and graphene oxide) to the synthesis solution for the preparation of nanosized ceria hybrid nanocomposite materials.

iii) The synthesized carbon materials will be modified with copper-cobalt mixed ferrites (CoCuFe2O4) and tested as catalysts in methanol decomposition.

iv) The obtained carbon materials and modified samples will be characterized by complex of various physicochemical methods, such as: low temperature physisorption of nitrogen, XRD, Moessbauer spectroscopy and TPR with hydrogen.

v) Finally, this investigation will be focused on the possibility for fine tuning and improving catalyst behavior by tailoring the properties of carbon support, by varying the nature of the precursor and the preparation procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The activated carbons from spent motor oil and waste were synthesized according to the procedure described in [

36]. In the beginning, two mixtures of spent motor oil and pine wood chips (AC-A) or crushed coal from "Chukurovo" mine (AC-B) in the proportion of 1:1 were treated with concentrated sulfuric acid under continuous stirring at 500 K until solidification. The obtained solid products were soaked in 0.1 N solution of NaOH and washed with distilled water to neutral pH. The next, carbonization step, modified materials were placed into ceramic crucibles covered with lids to prevent combustion. It was carried out at heating in air very slowly till 873 K. The obtained carbons after cooling and replaced in reactor were pyrolyzed in nitrogen and activated with water vapor (2 ml.min

-1). For the purpose the temperature was increased with 10 K. min

-1 up to the final activation temperature of 973 K, followed by treatment under these conditions for 15 minutes. After cooling in an inert atmosphere, the produced carbons were dried at 383 K for 30 min. Thus prepared activated carbons were denoted as AC-A and AC-B.

Nanodiamond (ND) powder with a particle size of 5 nm was dispersed in distilled water by sonication (1 h, 300 W), thus obtaining a suspension with a ND concentration of 4 mg/ml (weighed as dry matter). Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared as follows: 60 ml H2SO4, 10 ml H3PO4, 1g graphene and 3g KMnO4 were mixed in a round-bottom flask. The reaction mixture was then heated to 313 K and stirred for 6 h. The resulting suspension was poured onto ice and mixed with 200 ml 30% H2O2. The GO was decanted to neutral pH, thus obtaining a suspension with a GO concentration of 12.5 mg/ml (weighed as dry matter). A 20 mM solution of cerium (III) nitrate (500 ml) was mixed with the desired amount of graphene oxide (GO) (5; 10; 20 wt.%) or (ND) (1; 5; 10 wt.%). In a closed stirrer, it was purged with CO2-free air (to avoid carbonates, which are undesirable) for several minutes and heated to 303 K. The slow addition of 20 ml of ammonia solution to adjust the pH above 10 led to the precipitation of cerium hydroxide. The mixture was further stirred and purged with CO2-free air until it transformed to CeO2 (usually after about 4-5 hours). The resulting powder was washed several times with deionized water and dried. GO composite samples were dried by lyophilization with liquid nitrogen. ND composites were dried in air at 333 K.

The activated carbons, ceria/graphene oxide and ceria/nanodiamond-based supports were modified by the using incipient-wetness impregnation method with methanol solutions of Fe(NO3)3.9H2O, Co(NO3)2.6H2O and Cu(NO3)2.3H2O in appropriate ratios. Preliminary, the supports were evacuated at 333 K for 1 hour. After the impregnation procedure, the samples were dried at room temperature for 24 hours. The precursor decomposition was carried out in an inert atmosphere (N2) at 773 K for 2 hours. The metal content in the samples was 12% in all modifications, the molar ratio Fe/(Co+Cu) is 2, and the molar ratio Co/Cu is 1.

2.2. Methods

Low-temperature nitrogen physisorption analyses at 77 K were done on a Quantachrome Instruments NOVA 1200e (USA) apparatus. The specific surface areas (SBET) was determined from BET equation and the total pore volume (Vt) was evaluated by the amount of adsorbed nitrogen at relative pressure of 0.99. The micropore volume and area were calculated using the t-plot method. Powder X-ray diffraction patterns were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Ka radiation (λ=1.5406 Å) and a LynxEye detector with constant step of 0.02° 2θ and counting time of 17.5 s per step. The Mossbauer spectra were obtained on a Wissel (Wissenschaftliche Elektronik GmbH, Germany) electromechanical spectrometer using 57Co/Rh (activity z25 mCi) and a-Fe standards. The temperature programmed-thermogravimetric (TPR/TG) measurements were performed on a Setaram TG92 apparatus in a flow of H2 (Purity 5.0) in Ar (Purity 5.0, 50 vol %, total flow of 100 cm3min-1, and a heating rate of 5 Kmin-1).

Methanol decomposition was performed in a flow type fixed-bed reactor using 0.055 g of catalyst. Argon was used as carrier gas, the methanol partial pressure was 1.57 kPa and the used weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) was 1.5 h-1. The catalysts were tested under temperature-programmed regime within the temperature range of 350-770 K and a heating rate of 1 Kmin-1. The GC analyses were carried out on a SCION 456-GC apparatus equipped with flame ionization and thermoconductivity detectors, and by using PORAPAC-Q column.

3. Results

3.1. Low-Temperature Nitrogen Physisorption

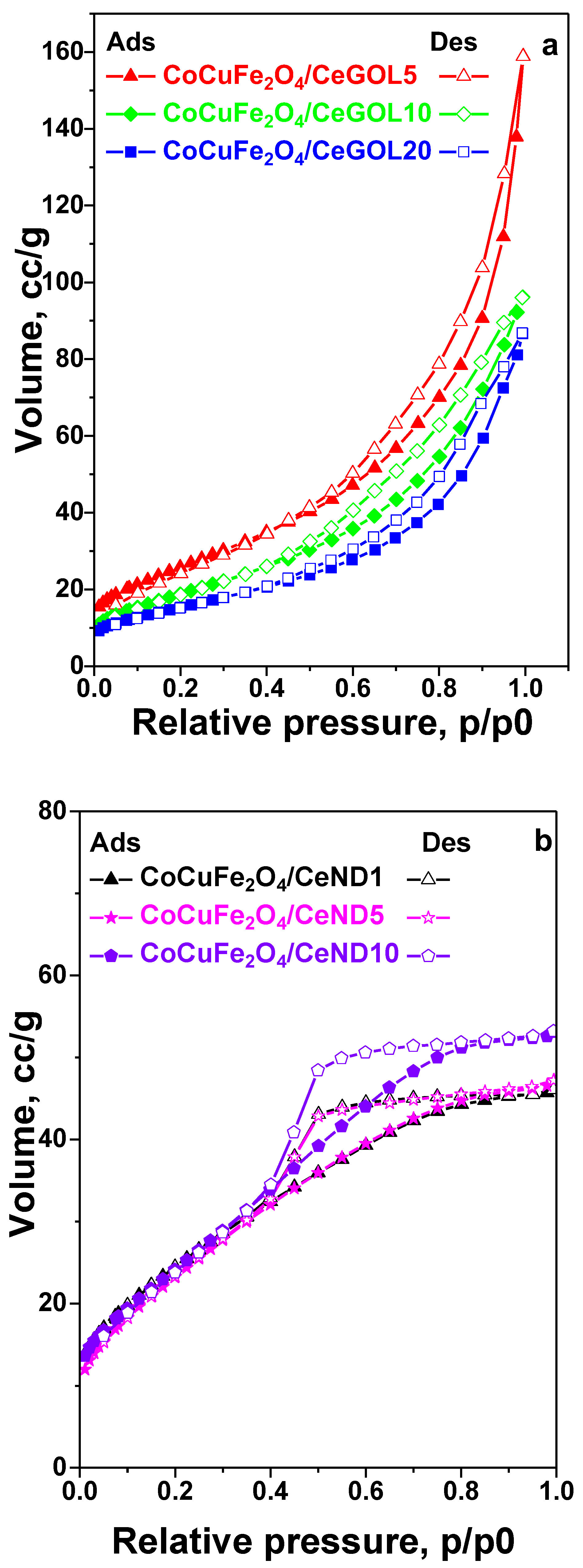

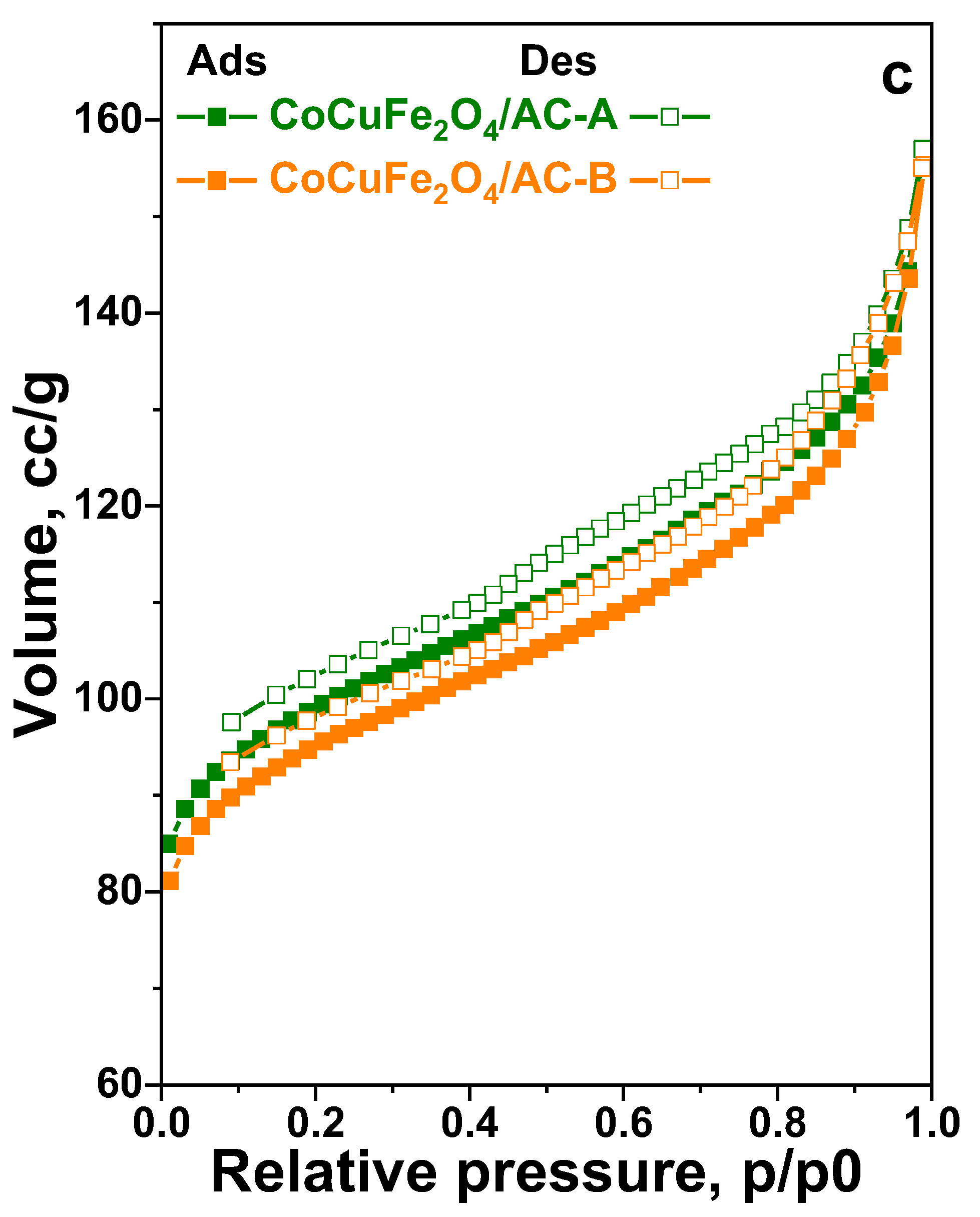

The low-temperature nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms of the obtained materials are presented in

Figure 1 a, b, c and the corresponding textural parameters are listed in

Table 1. The isotherms of all carbon-containing materials are characterized with gradual increase at low relative pressure (p/p0) and capillary condensation step above 0.5 p/p0 that give rise to a combination of types I and II isotherms according to IUPAC classification characteristic of micro-microporous materials [

37]. At the same time, a H4 hysteresis loop is registered as well that often could be found with aggregated particles characterized with relatively large amount of interparticle meso- and macropores (

Table 1).

The use of activated carbon as a support leads in significantly higher values of specific surface area and total pore volume compared to ceria-graphene oxide and ceria-nanodiamond (

Table 1) materials. This effect is probably due to the predominant microporous structure typical of activated carbon-based materials. The use of a support containing graphene oxide phase with a higher concentration (GOL 20) leads to a significant decrease in the specific surface area, probably due to the deposition of different sized types of metal oxides, which not only deposit in the pores of the starting cerium-carbon nanocomposite, but also deposit as larger crystallites on its surface and thus block part of the starting pores of the support. In the modifications based on the graphene oxide containing supports, the found increase in the total pore volume in comparison to their ND analogues is an indication of the higher porosity of the GOL support.

3.2. Powder X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The XRD data for the phase composition, unit cell parameters and average crystallite size of all modified materials are summarized in

Table 2. The powder X-ray diffraction data shows the presence of reflections only of the CeO

2 phase [

38,

39] with a crystallite size of 6-8 nm for the ND and GOL modifications. No reflections of another metal-containing phase are registered, as well as those of carbon materials, which is an indication of the presence of only very finely dispersed metal oxide phases, and indicates the excellent dispersion of the loaded cobalt-copper ferrite phase on this type of support. In the activated carbon-based materials, only a (Co,Cu)Fe

2O

4 mixed metal oxide phase with an average crystallite size of 4-5 nm was registered.

3.3. Moessbauer Spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectroscopy was used to identify the type of iron phases and their quantification. The data of selected samples for the hyperfine interaction parameters - isomer shift (δ), quadrupole splitting (Δ) and line width (Γexp) are summarized in

Table 3. The experimental spectra of all samples are similar and are composed of doublet and sextet components. The doublets of all modifications have characteristic parameters of Fe

3+ in oxide phases and may be due to paramagnetic or superparamagnetic phases, including superparamagnetic ferrite phases with spinel structure. The sextet components also have typical Fe

3+ parameters in a spinel-type structure due to iron in tetrahedral and octahedral oxygen environments. This cannot be said for Sx3 in the spectrum of the CoCuFe

2O

4/AC-B sample, which has a significant line width and is probably due to particles with a size close to the size of the superparamagnetic particles. It is interesting to note that the value of the isomeric shift of Sx2 in sample B is higher than that typical for Fe

3+, but is characteristic of iron ions in the octahedral lattice of magnetite. In fact, in the octahedral sublattice of magnetite there are Fe

3+ ions and Fe

2+ ions, but due to the presence of electron exchange and the inability to distinguish them, they are combined into a sextet component, corresponding conditionally to an oxidation state of iron of

2.5+ [

40,

41]. The particle size in the samples can be judged by the relative weight of the superparamagnetic doublet in the spectra, other things being equal. Therefore, by average particle size the samples should be arranged in the order: B > A. (The latter is valid only if the crystalline phases in the two modified activated carbon samples are the same, i.e. the spectra depend only on the size effect).

3.4. Temperature Programmed Reduction-Thermo-Gravimetric (TPR–TG) Experiments

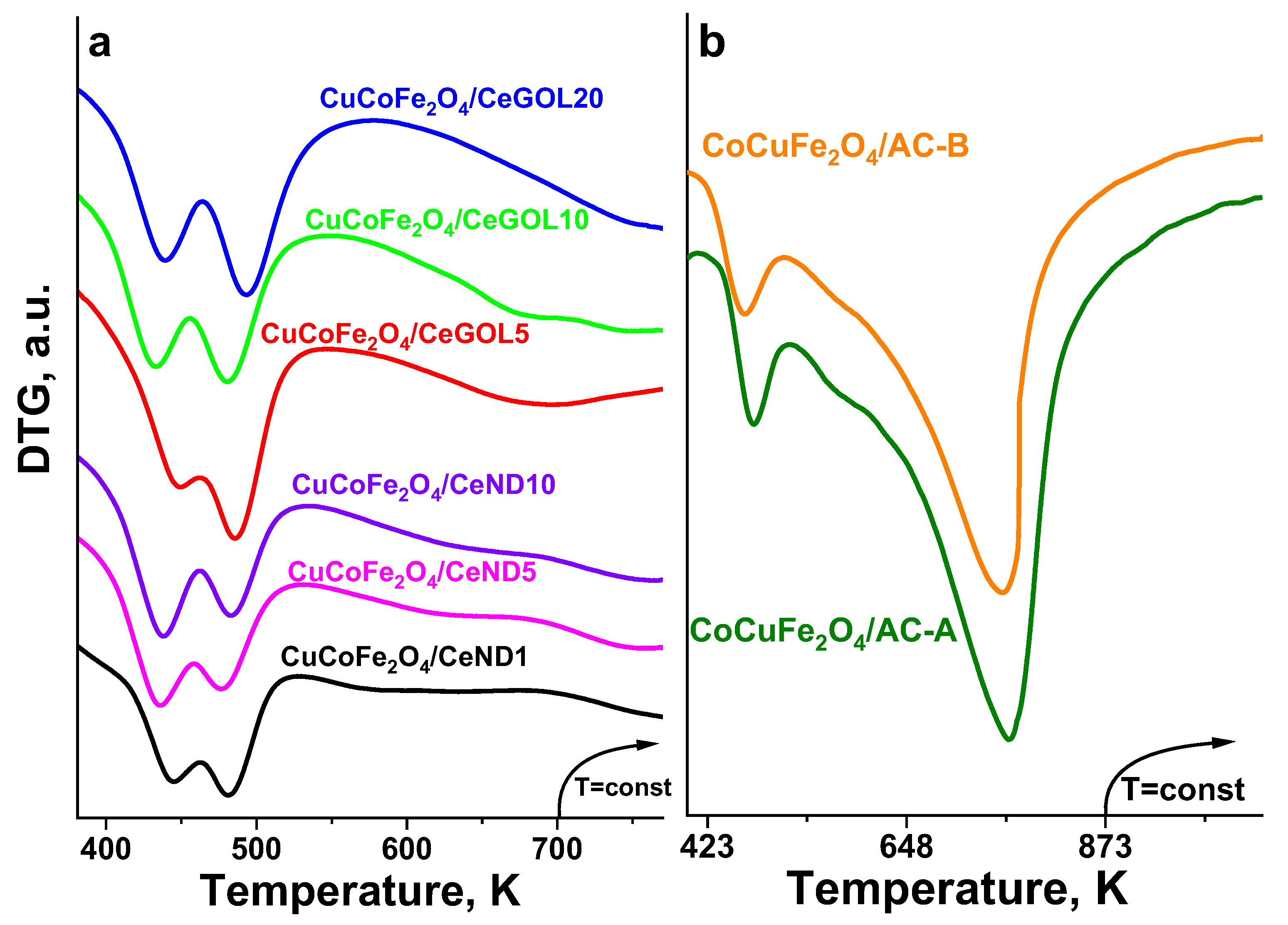

In the

Figure 2 shows the reduction transformations in the obtained modifications of the nanocomposite hybrid materials, which were investigated using temperature-programmed reduction with hydrogen.

The TPR-TG profiles of the ND and GOL modifications show an almost constant weight loss in the 400-773 K range. All modifications exhibited two well-defined reduction effects with maxima in the range 430-490 K. According to the literature [

42], these effects correspond to the reduction of well dispersed CuO phase and we also assign it to the reduction of the copper phase within the samples. However, these effects are two big, which means that the reduction of the copper facilitates also the reduction of cobalt and iron oxides present in these samples. The further and not well defined weight loss could be ascribed to the reduction of not readily reducible cobalt- and iron oxide phases. This assumption is in accordance with [

43], where the broad peak in the range of after 575 K could be ascribed to the reduction of Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ [

44]. The peaks associated with the reduction of cobalt Co

3O

4 (Co

3O

4→CoO) and iron Fe

2O

3 (Fe

2O

3→Fe

3O

4→Fe) particles (593K and 789K) [

43] were not recorded. The reduction effects of activated carbon-based modifications are different. In these samples, that were studied in the 400-873 K range, we observe also two reduction effects with maxima at around 475 K and 763 K, however, the high-temperature one is very broad. The first effect is probably due to the reduction of well dispersed CuO, and the second high-temperature effect is due to the reduction of cobalt- and iron oxide from the mixed-oxide spinel phase (

Table 2,

Table 3), where larger spinnel and iron oxide particles were found. In conclusion we can say the results clearly indicated the presence of synergetic interaction between the loaded different metal oxide species, which in accordance with XRD and Moessbauer data may be due to the close contact and good dispersion of the various oxide phases, especially in the case of ND- and GOL modifications.

3.5. Catalytic Test

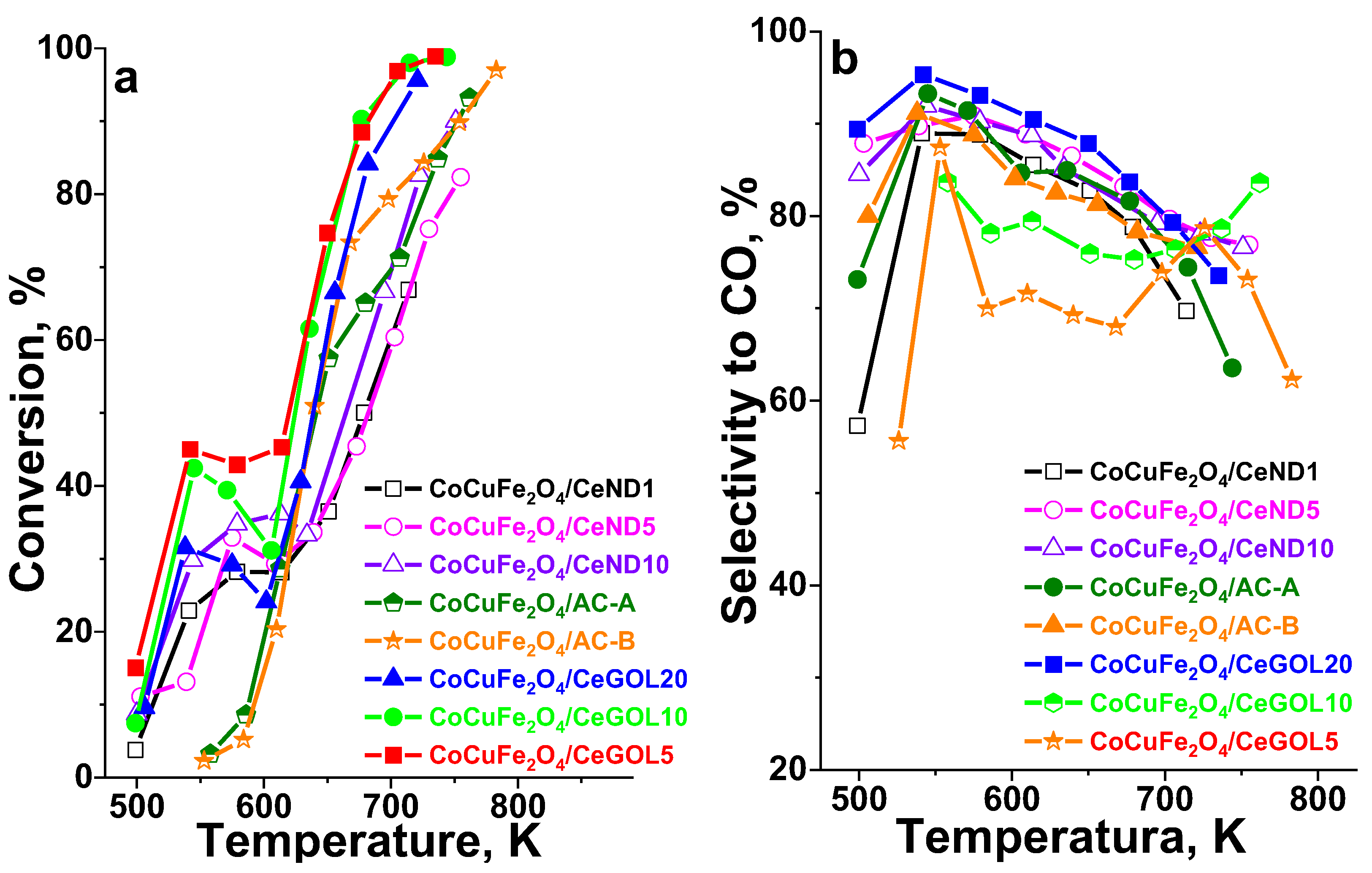

The temperature dependencies of methanol decomposition on various modifications in the temperature range of 550–750 K are presented in

Figure 3 a, b.

The catalytic activity was observed above 500 K and hydrogen and CO are the main registered products, however a small amount of methane (up to 4-6%) and CO

2 (up to 8-10%) are also detected as by-products for all materials. Ceria-GOL and ceria-ND modifications show catalytic activity reaching 45% of conversion in the range 500-570 K, where the activated carbon modifications do not show catalytic conversion. We could assign this effect to the facilitated reduction found for the former materials (see TPR data). However, above 600 K, both activated carbon ferrite modifications show a steep rise in the catalytic activity which exceeds the one registered for the ceria-ND catalysts. The highest activity and selectivity is registered for catalysts based on ceria-graphene oxide support. The BET (

Table 1) analysis showed the presence of the higher porosity for these materials that could lead to higher dispersion (

Table 2) that are readily reducible (

Figure 2) and better exposed to the methanol. For AC modifications, we already assumed that the significant decrease in the microporosity (

Table 1) of the carbon support (AC) after the modification with ferrites could be due to either blocking by deposition of the metal oxide species within the micropores or to a simultaneous formation of oxide particles on the external carbon surface. This leads the formation of both active ferrite species that are not accessible to the reactants and larger spinel mixed oxide phase (XRD, Moessbauer) that are more difficult to reduce and are active just at elevated reaction temperatures.

4. Conclusions

The activated carbons, ceria/graphene oxide and ceria/nanodiamond materials were used as supports of copper-cobalt ferrite oxide phase loaded by the using incipient-wetness impregnation method. The catalysis composition and the distribution of the metal ions in the spinel sub-lattices and the related redox and catalytic properties depend on the texture and composition of the used carbon-containing supports. They could be easily tuned by a variation in the additional precursor in case of the activated carbons and by the amount of graphene oxide or nanodiamond in the hybrid nanocomposites. The use of a CeO2-graphene oxide support provides the formation of a higher porosity in the modifications and leads to higher catalytic activity due to the improved dispersion and hence facilitated reducibility of the loaded metal oxide phase as well as better accessibility of the active species to the reactants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I. and M.D.; methodology, G.I., M.D., I.T. and S.M.; investigation, G.I., M.D., I.D., N.V., D.K., S.M. and J.T.; data curation, G.I., M.D., I.T., I.D., N.V., D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I., M.D., I.T.; writing—review and editing, G.I., M.D., I.T.; project administration, G.I.; funding acquisition, G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Bulgarian National Scientific Fund, grant number КП-06-H59/12/2021 and project № BG16RFPR002-1.014-0006 "National Centre of Excellence Mechatronics and Clean Technologies" was used for experimental work financially supported by European Regional Development Fund under "Research Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation" program 2021-2027.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Bulgarian National Scientific Fund (Grant Number КП-06-H59/12/2021). Research equipment of the project № BG16RFPR002-1.014-0006 "National Centre of Excellence Mechatronics and Clean Technologies" was used for experimental work financially supported by European Regional Development Fund under "Research Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation" program 2021-2027.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| TPR–TG |

Temperature programmed reduction-thermo-gravimetric experiments |

| AC-A |

activated carbons - spent motor oil and pine wood chips |

| AC-B |

activated carbons - spent motor oil and crushed coal from "Chukurovo" mine |

| ND |

Nanodiamond powder |

| GOL |

Graphene oxide |

References

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and Evaluation of Hydrogen Production Methods for Better Sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Yi, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Du, M.; Pan, J.; Wang, Q. Review of Hydrogen Production Using Chemical-Looping Technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 3186–3214. [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A.; Pollet, B.G. Hydrogen Economy: Paving the Path to a Sustainable, Low-Carbon Future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 93, 307–319. [CrossRef]

- Karakoti, A.S.; King, J.E.S.; Vincent, A.; Seal, S. Synthesis Dependent Core Level Binding Energy Shift in the Oxidation State of Platinum Coated on Ceria–Titania and Its Effect on Catalytic Decomposition of Methanol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 388, 262–271. [CrossRef]

- Jampa, S.; Jamieson, A.M.; Chaisuwan, T.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Wongkasemjit, S. Achievement of Hydrogen Production from Autothermal Steam Reforming of Methanol over Cu-Loaded Mesoporous CeO2 and Cu-Loaded Mesoporous CeO2–ZrO2 Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 15073–15084. [CrossRef]

- Clarizia, L.; Spasiano, D.; Di Somma, I.; Marotta, R.; Andreozzi, R.; Dionysiou, D.D. Copper Modified-TiO2 Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation through Photoreforming of Organics. A Short Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 16812–16831. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Shen, W.-J. Methanol Decomposition and Synthesis Over Palladium Catalysts. Top. Catal. 2003, 22, 271–275. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.M. Sustainable and/or Waste Sources for Catalysts: Porous Carbon Development and Gasification. Catal. Today 2017, 285, 204–210. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, P.; Xu, M.; Ning, C.; Sze Ki Lin, C.; McKay, G. A Critical Review on Preparation, Characterization and Utilization of Sludge-Derived Activated Carbons for Wastewater Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 895–906. [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.A.; Al-Qodah, Z.; Ngah, C.W.Z. Agricultural Bio-Waste Materials as Potential Sustainable Precursors Used for Activated Carbon Production: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 46, 218–235. [CrossRef]

- Menya, E.; Olupot, P.W.; Storz, H.; Lubwama, M.; Kiros, Y. Production and Performance of Activated Carbon from Rice Husks for Removal of Natural Organic Matter from Water: A Review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 129, 271–296. [CrossRef]

- Bader, N.; Ouederni, A. Functionalized and Metal-Doped Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons for Energy Storage Application. J. Energy Storage 2017, 13, 268–276. [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Ahmad, T. A Review on Utilization of Wood Biomass as a Sustainable Precursor for Activated Carbon Production and Application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 87, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, M.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Ma, X. Hydrogen Production by Catalytic Methane Decomposition: Carbon Materials as Catalysts or Catalyst Supports. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 19755–19775. [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, M.; Malaika, A.; Rechnia, P.; Miklaszewska, A.; Kozłowski, M. Metal/Activated Carbon Systems as Catalysts of Methane Decomposition Reaction. Catal. Today 2015, 249, 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Konwar, L.J.; Boro, J.; Deka, D. Review on Latest Developments in Biodiesel Production Using Carbon-Based Catalysts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 546–564. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Weon, S.; Moon, G.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, W. Robust Co-Catalytic Performance of Nanodiamonds Loaded on WO3 for the Decomposition of Volatile Organic Compounds under Visible Light. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 8350–8360. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, R.; Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Xie, J. Graphene-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 430, 53–107. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, A.M.T. Graphene Oxide-P25 Photocatalysts for Degradation of Diphenhydramine Pharmaceutical and Methyl Orange Dye. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 275, 361–368. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, S.; Liao, W.; You, H. Novel Ceria/Graphene Oxide Composite Abrasives for Chemical Mechanical Polishing. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 26325–26333. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Das, A.K.; Khanra, P.; Uddin, M.E.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Characterizations of in Situ Grown Ceria Nanoparticles on Reduced Graphene Oxide as a Catalyst for the Electrooxidation of Hydrazine. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9792–9801. [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, T.S.; Das, S.; Pratt, C.J.; Seal, S. One-Pot Synthesis of a Ceria–Graphene Oxide Composite for the Efficient Removal of Arsenic Species. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3367–3374. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, X.; Dai, L.; Gong, H.; Lin, S. Chemical-Mechanical Polishing Performance of Core-Shell Structured Polystyrene@ceria/Nanodiamond Ternary Abrasives on Sapphire Wafer. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 31691–31701. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, M.; Issa, G.; Kovacheva, D.; Tsoncheva, T. Novel Ceria and Ceria-Based Nanocomposites as Potential Catalysts for Methanol Decomposition and Total Oxidation of Ethyl Acetate. Proc. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 2022, 75, 1287–1294. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ji, L.; Ma, P.-C.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, W.; Li, Y. Development of Carbon Nanotubes/CoFe2O4 Magnetic Hybrid Material for Removal of Tetrabromobisphenol A and Pb(II). J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 265, 104–114. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-J.; You, C.-F. Phosphorus Adsorption onto Green Synthesized Nano-Bimetal Ferrites: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Investigation. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 251, 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, L. Facile Synthesis, Characterization of a MnFe2O4/Activated Carbon Magnetic Composite and Its Effectiveness in Tetracycline Removal. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 135, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.A.; Yusoff, I.; Alias, Y. Fluoride Adsorption by Doped and Un-Doped Magnetic Ferrites CuCexFe2-XO4: Preparation, Characterization, Optimization and Modeling for Effectual Remediation Technologies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 316–324. [CrossRef]

- Velinov, N.; Manova, E.; Tsoncheva, T.; Estournès, C.; Paneva, D.; Tenchev, K.; Petkova, V.; Koleva, K.; Kunev, B.; Mitov, I. Spark Plasma Sintering Synthesis of Ni1−xZnxFe2O4 Ferrites: Mössbauer and Catalytic Study. Solid State Sci. 2012, 14, 1092–1099. [CrossRef]

- Velinov, N.; Koleva, K.; Tsoncheva, T.; Manova, E.; Paneva, D.; Tenchev, K.; Kunev, B.; Mitov, I. Nanosized Cu0.5Co0.5Fe2O4 Ferrite as Catalyst for Methanol Decomposition: Effect of Preparation Procedure. Catal. Commun. 2013, 32, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Manova, E.; Tsoncheva, T.; Paneva, D.; Popova, M.; Velinov, N.; Kunev, B.; Tenchev, K.; Mitov, I. Nanosized Copper Ferrite Materials: Mechanochemical Synthesis and Characterization. J. Solid State Chem. 2011, 184, 1153–1158. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Xue, T.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Oxygen Vacancy Mediated CuyCo3-YFe1Ox Mixed Oxide as Highly Active and Stable Toluene Oxidation Catalyst by Multiple Phase Interfaces Formation and Metal Doping Effect. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 269, 118827. [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, S.; Nasiri, A.; Hashemi, M. Enhanced Activation of Persulfate by CuCoFe2O4@MC/AC as a Novel Nanomagnetic Heterogeneous Catalyst with Ultrasonic for Metronidazole Degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131872. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Rajabi, S.; Amiri, A.; Fattahizade, M.; Hasani, O.; Lalehzari, A.; Hashemi, M. Adsorption of Tetracycline Using CuCoFe2O4@Chitosan as a New and Green Magnetic Nanohybrid Adsorbent from Aqueous Solutions: Isotherm, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Study. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104014. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Rajabi, S.; Hashemi, M.; Nasab, H. CuCoFe2O4@MC/AC as a New Hybrid Magnetic Nanocomposite for Metronidazole Removal from Wastewater: Bioassay and Toxicity of Effluent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 296, 121366. [CrossRef]

- Tsoncheva, T.; Mileva, A.; Paneva, D.; Kovacheva, D.; Spassova, I.; Nihtianova, D.; Markov, P.; Petrov, N.; Mitov, I. Zinc Ferrites Hosted in Activated Carbon from Waste Precursors as Catalysts in Methanol Decomposition. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 229, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Broekhoff, J.C.P. Mesopore Determination from Nitrogen Sorption Isotherms: Fundamentals, Scope, Limitations. In Preparation of Catalysts II; Delmon, B., Grange, P., Jacobs, P., Poncelet, G.B.T.-S. in S.S. and C., Eds.; Elsevier, 1979; Vol. 3, pp. 663–684 ISBN 0167-2991.

- Tsoncheva, T.; Rosmini, C.; Dimitrov, M.; Issa, G.; Henych, J.; Němečková, Z.; Kovacheva, D.; Velinov, N.; Atanasova, G.; Spassova, I. Formation of Catalytic Active Sites in Hydrothermally Obtained Binary Ceria–Iron Oxides: Composition and Preparation Effects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 1838–1852. [CrossRef]

- Tsoncheva, T.; Mileva, A.; Issa, G.; Henych, J.; Tolasz, J.; Dimitrov, M.; Kovacheva, D.; Atanasova, G.; Štengl, V. Mesoporous Copper-Ceria-Titania Ternary Oxides as Catalysts for Environmental Protection: Impact of Ce/Ti Ratio and Preparation Procedure. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 595, 117487. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Humbe, A. V; Kumar, A.; Dorik, R.G.; Jadhav, K.M. Urea Assisted Synthesis of Ni1−xZnxFe2O4 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.8): Magnetic and Mössbauer Investigations. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 704, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Borhan, A.I.; Ghercă, D.; Iordan, A.R.; Palamaru, M.N. 2 - Classification and Types of Ferrites. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials; Pal Singh, J., Chae, K.H., Srivastava, R.C., Caltun, O.F.B.T.-F.N.M.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2023; pp. 17–34 ISBN 978-0-12-823717-5.

- Dow, W.-P.; Wang, Y.-P.; Huang, T.-J. TPR and XRD Studies of Yttria-Doped Ceria/γ-Alumina-Supported Copper Oxide Catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 190, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Watanabe, H.; Xu, Y.; Tamura, M.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tomishige, K. Catalytic Performance and Characterization of Co–Fe Bcc Alloy Nanoparticles Prepared from Hydrotalcite-like Precursors in the Steam Gasification of Biomass-Derived Tar. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 160–161, 701–715. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hisada, Y.; Koike, M.; Li, D.; Watanabe, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tomishige, K. Catalyst Property of Co–Fe Alloy Particles in the Steam Reforming of Biomass Tar and Toluene. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 121–122, 95–104. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).