Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

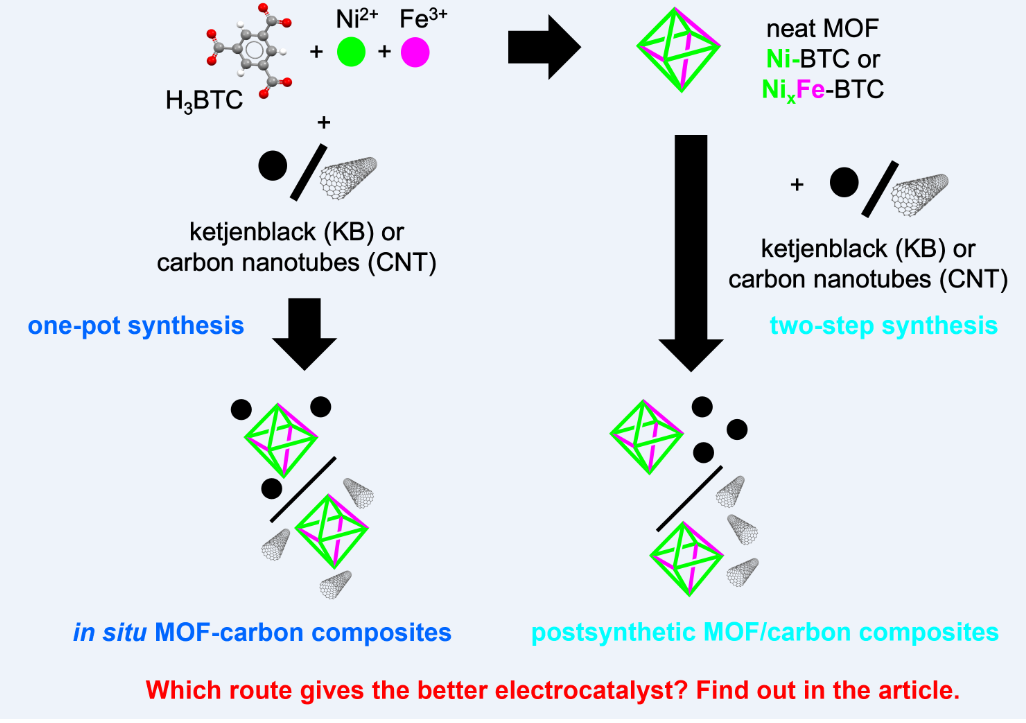

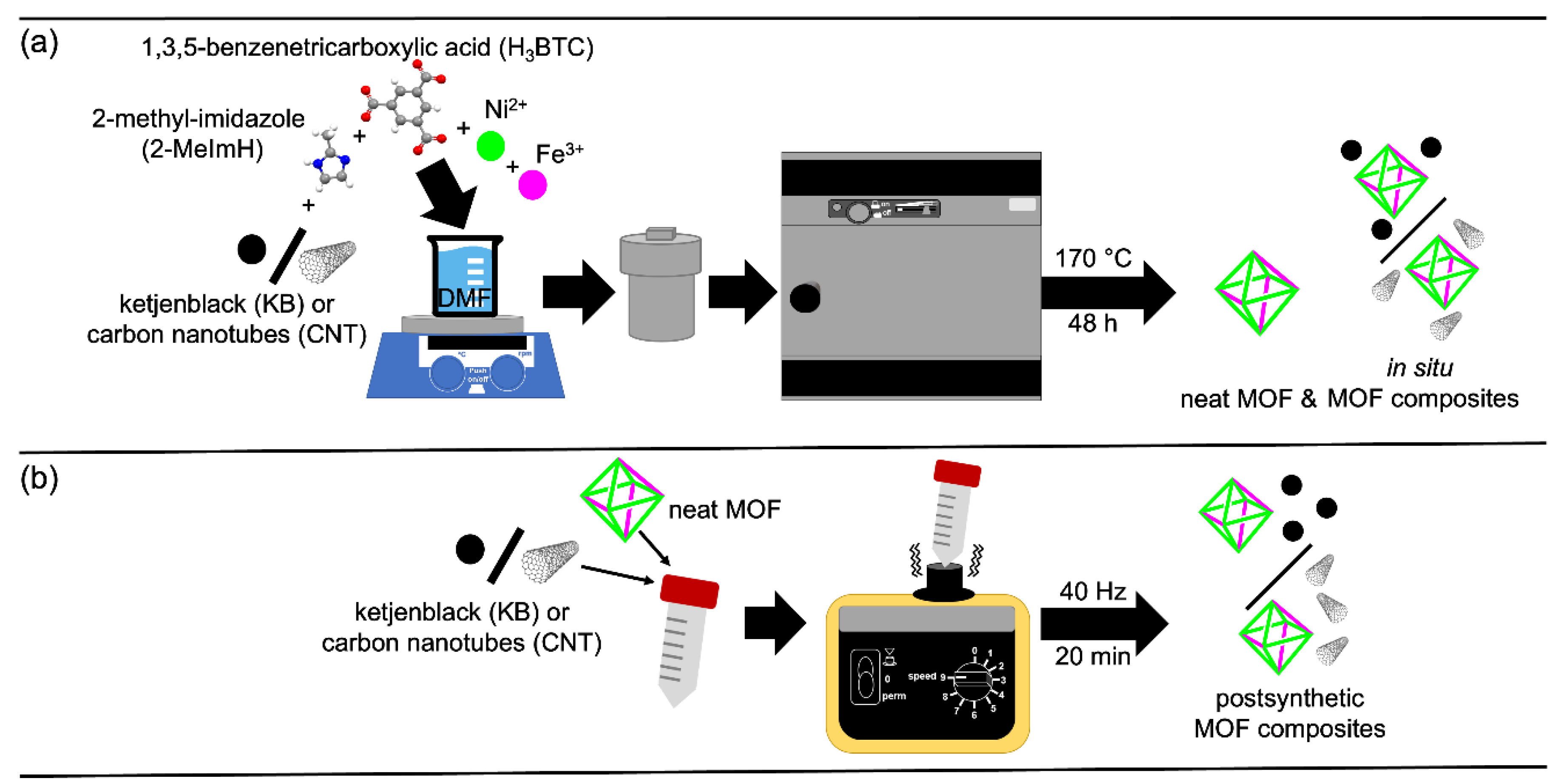

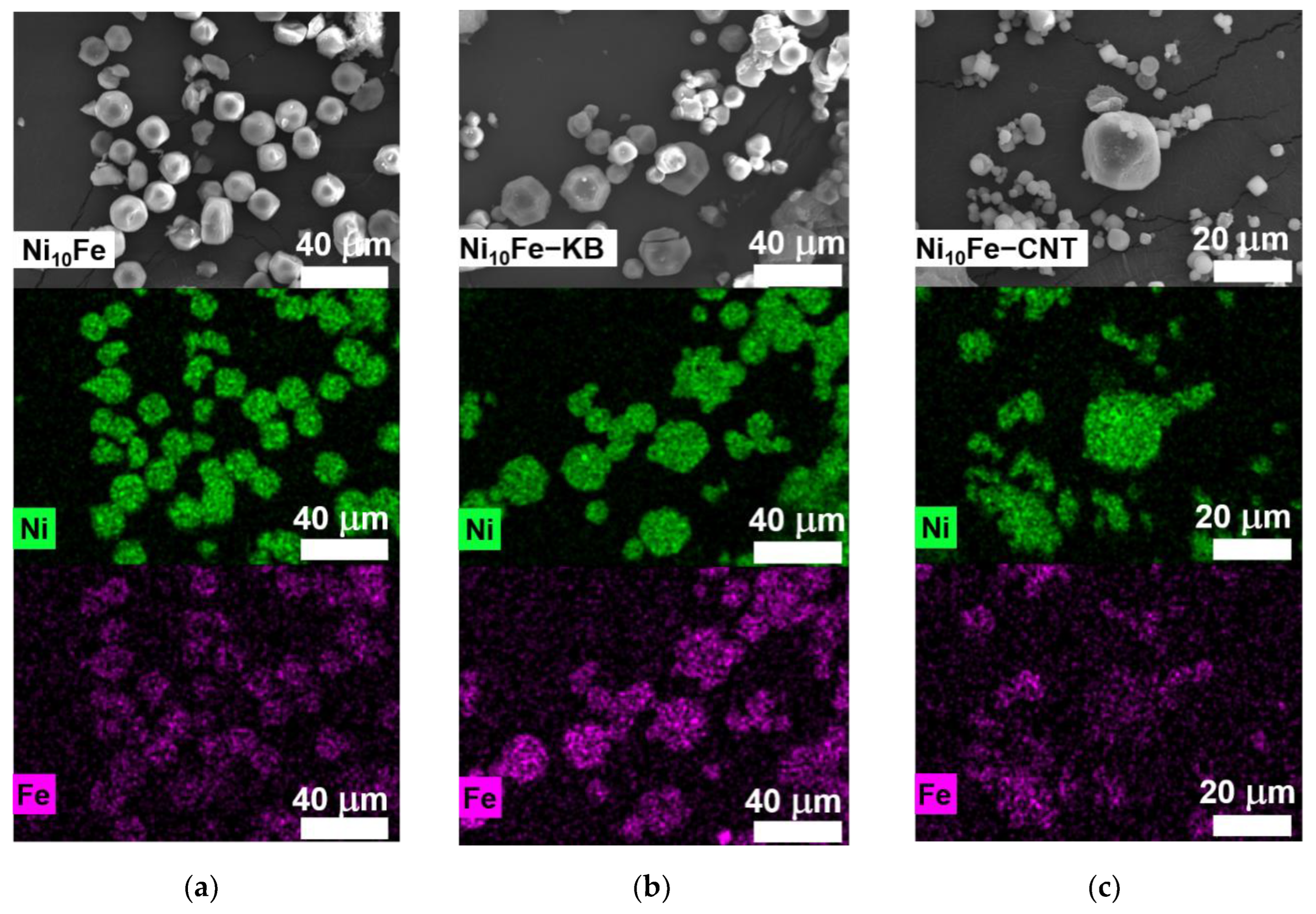

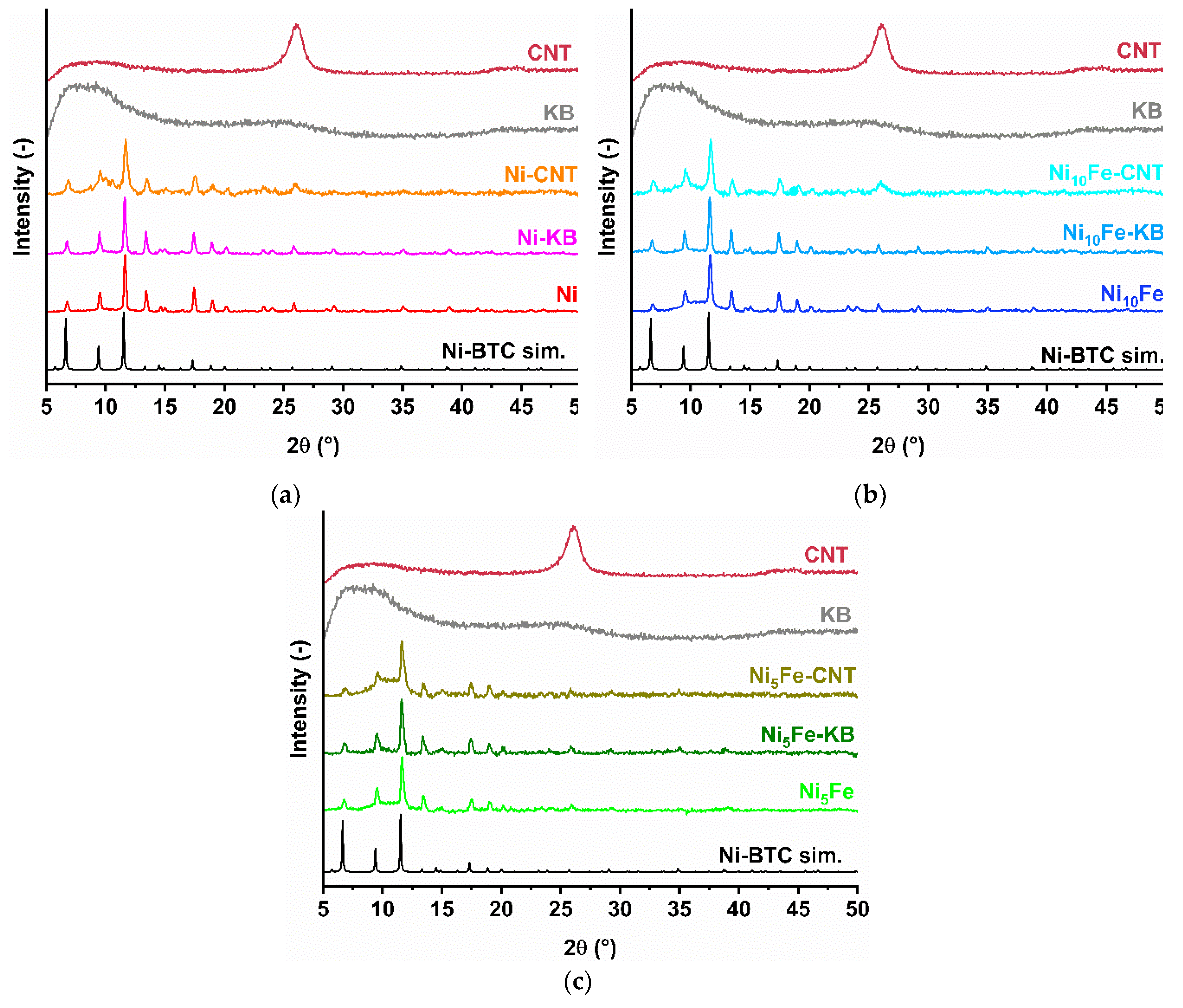

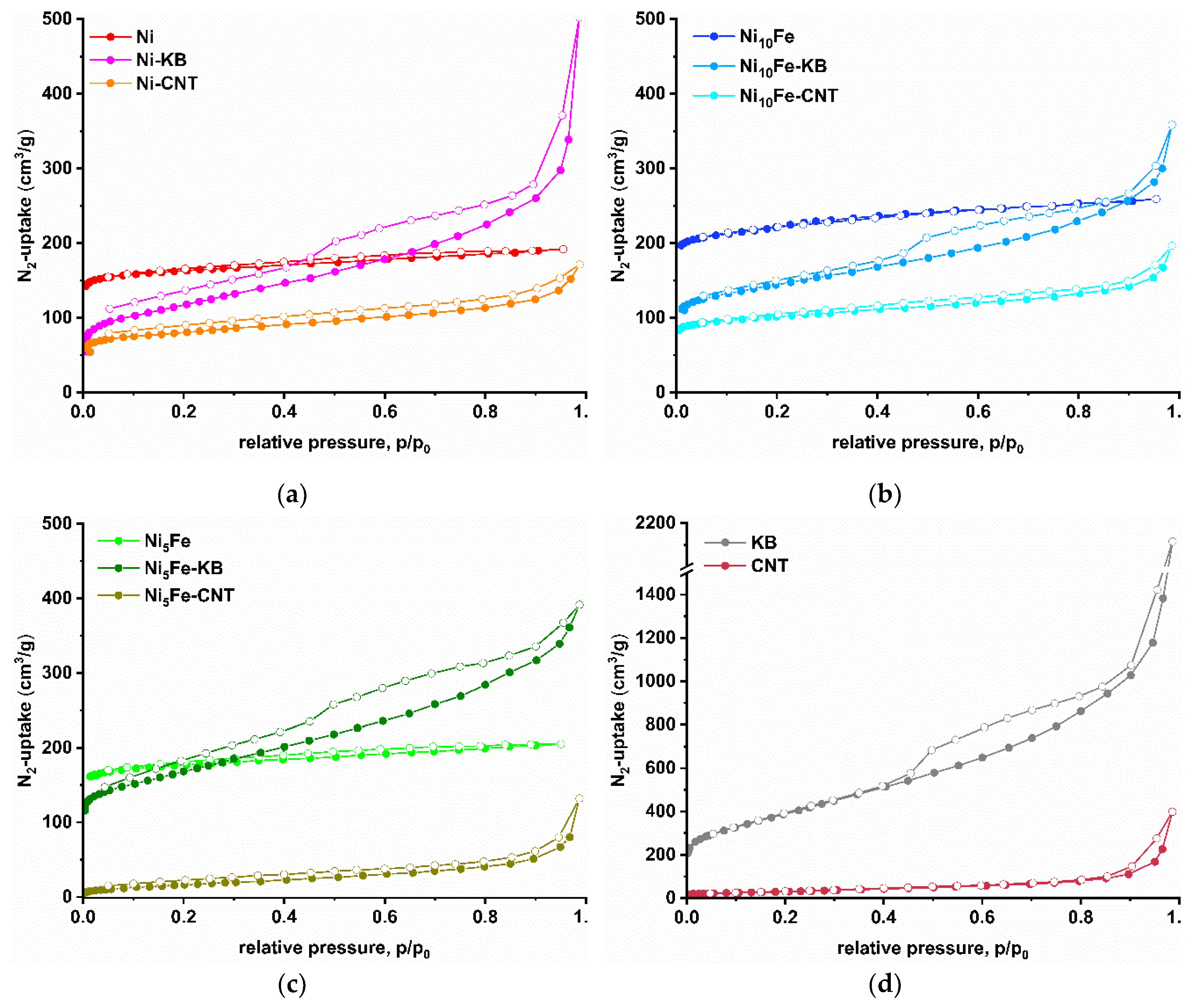

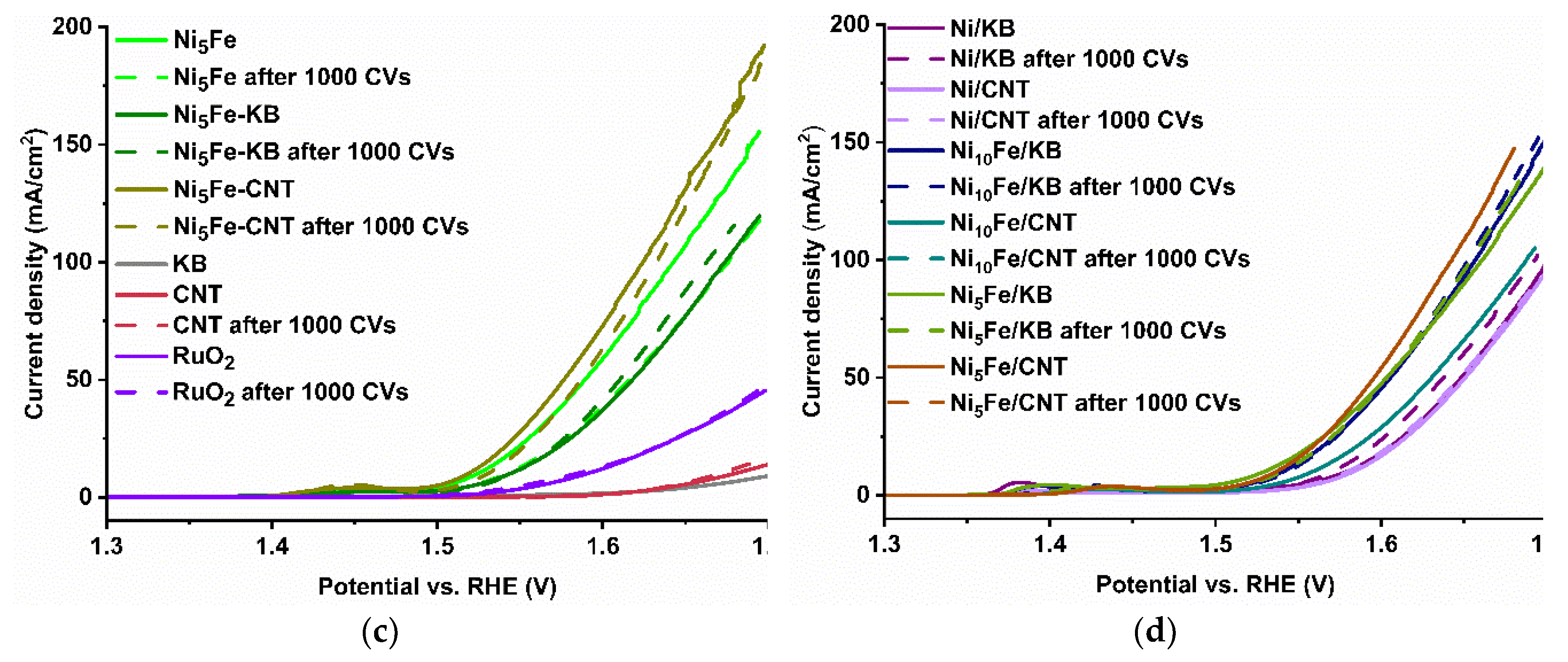

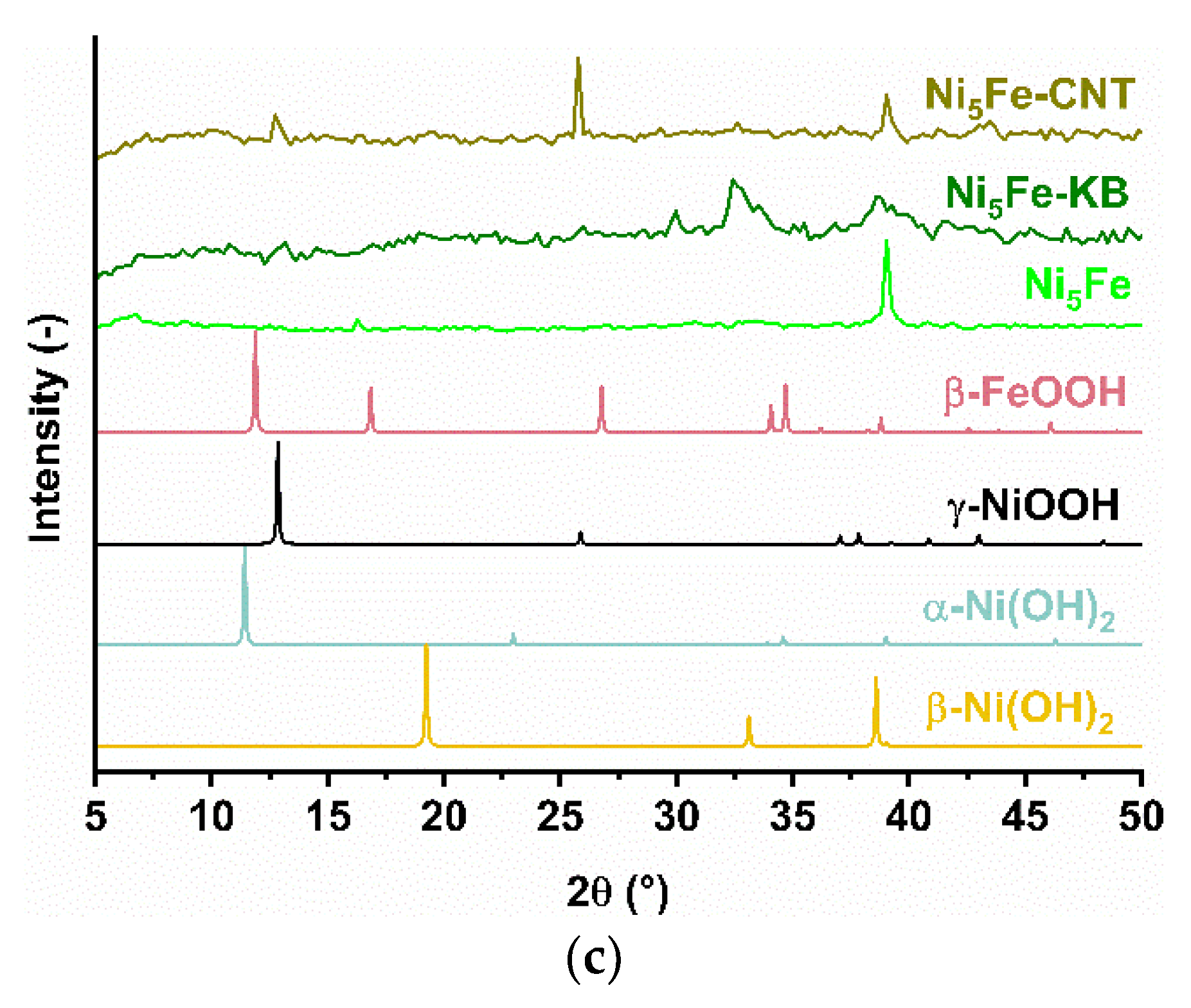

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the MOF Composites

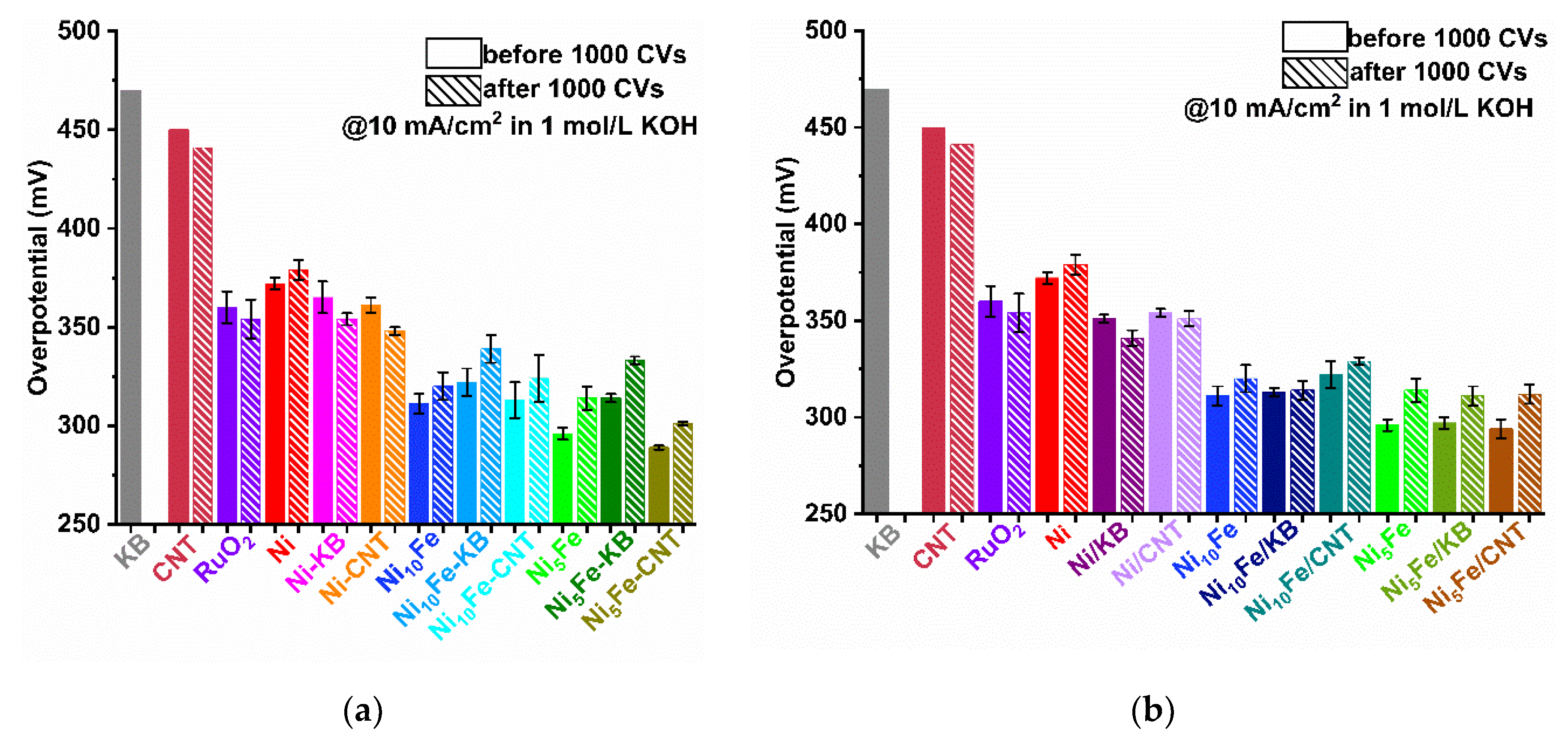

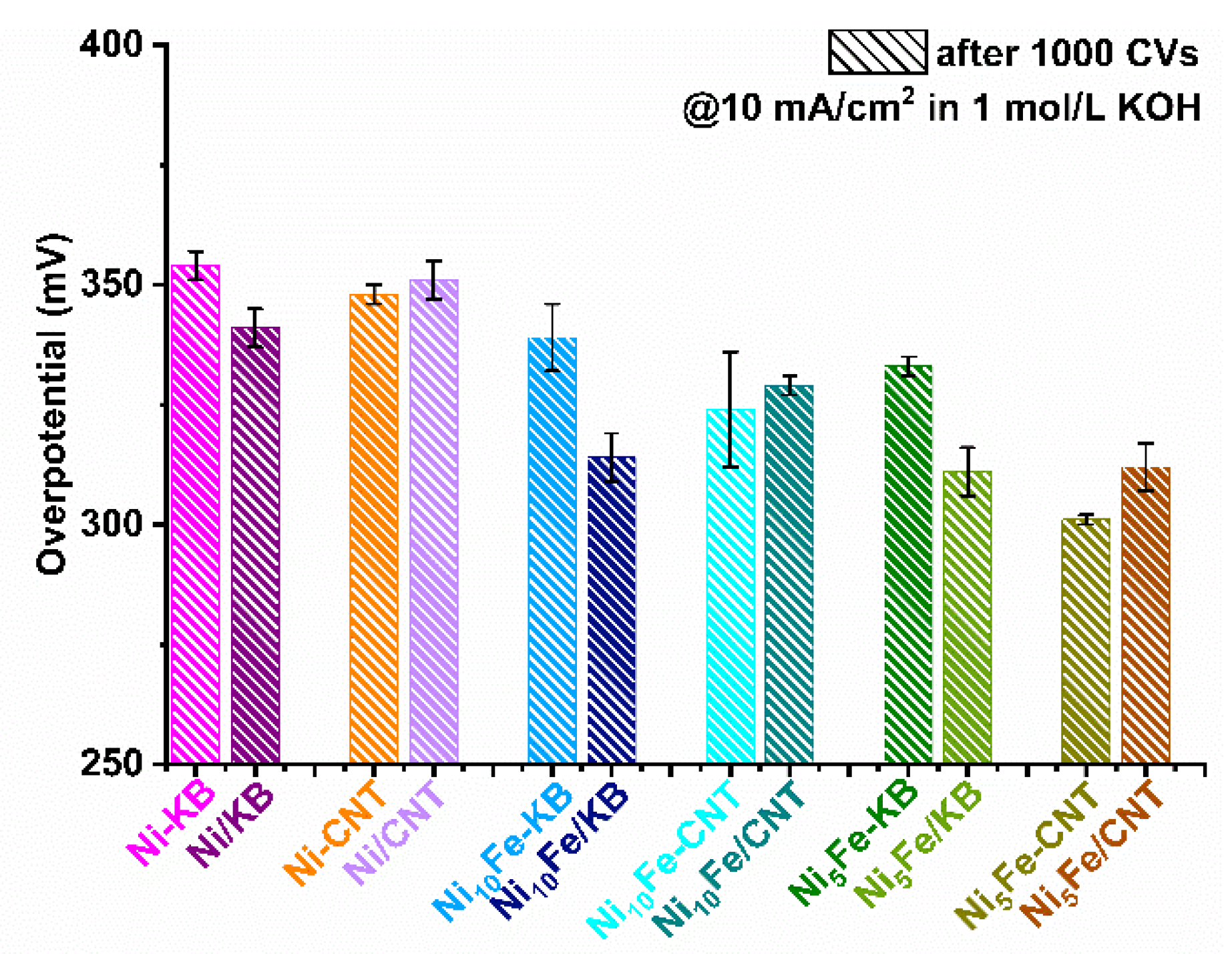

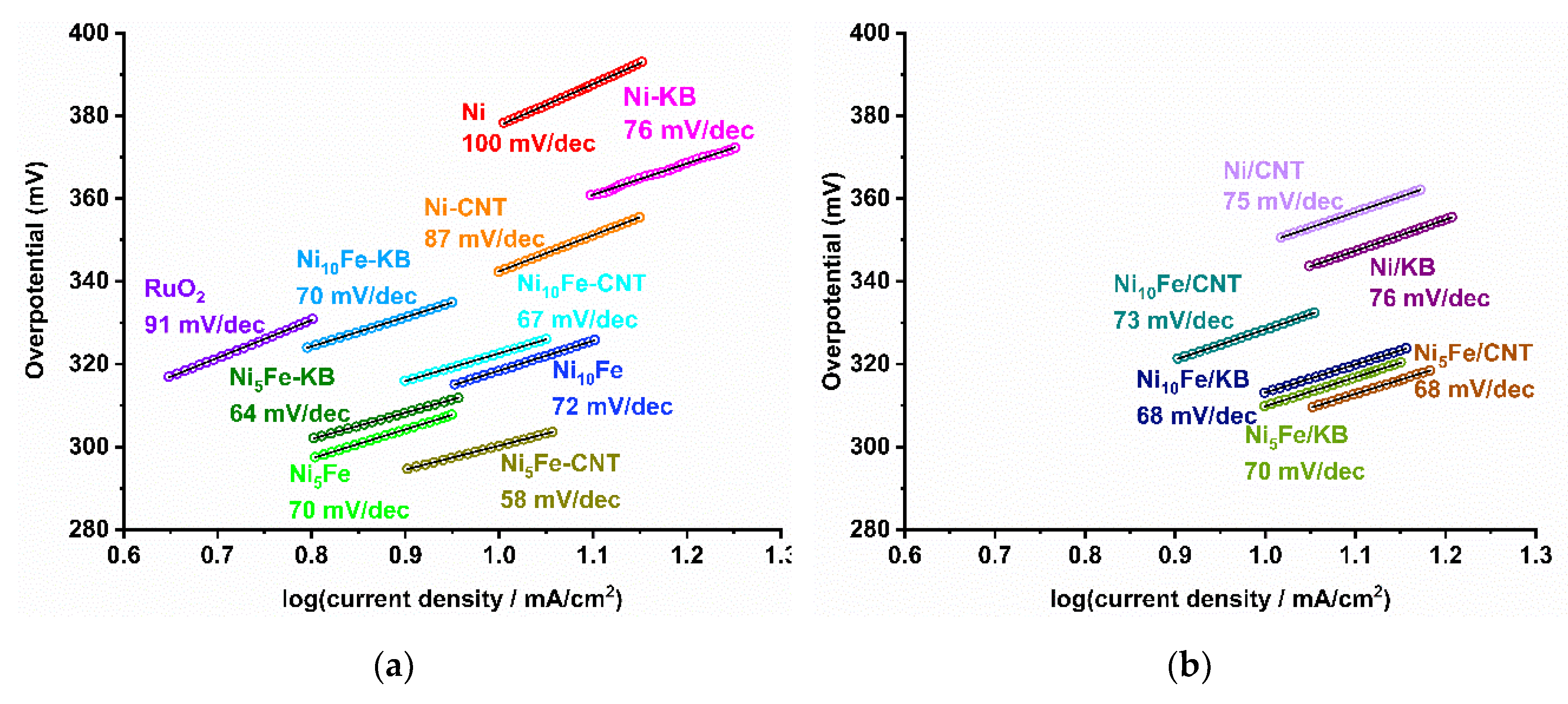

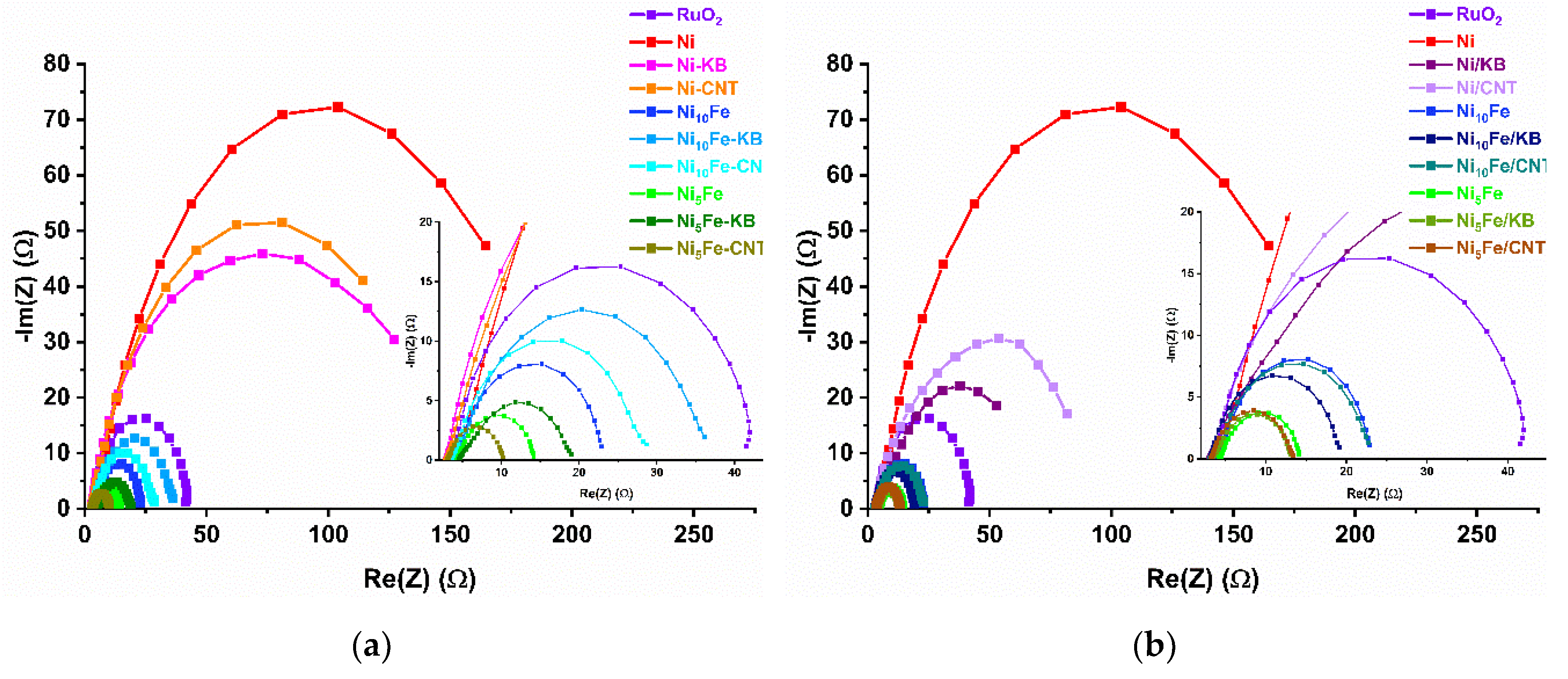

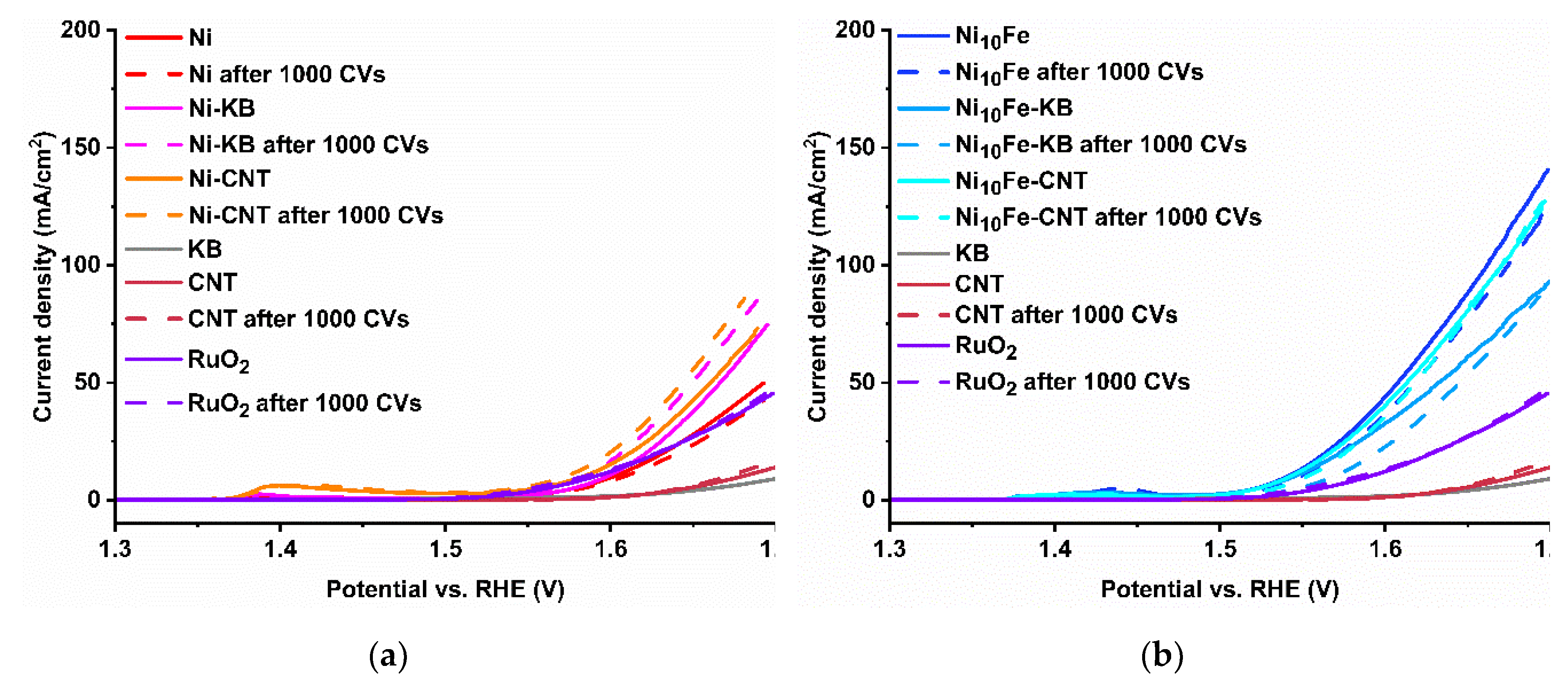

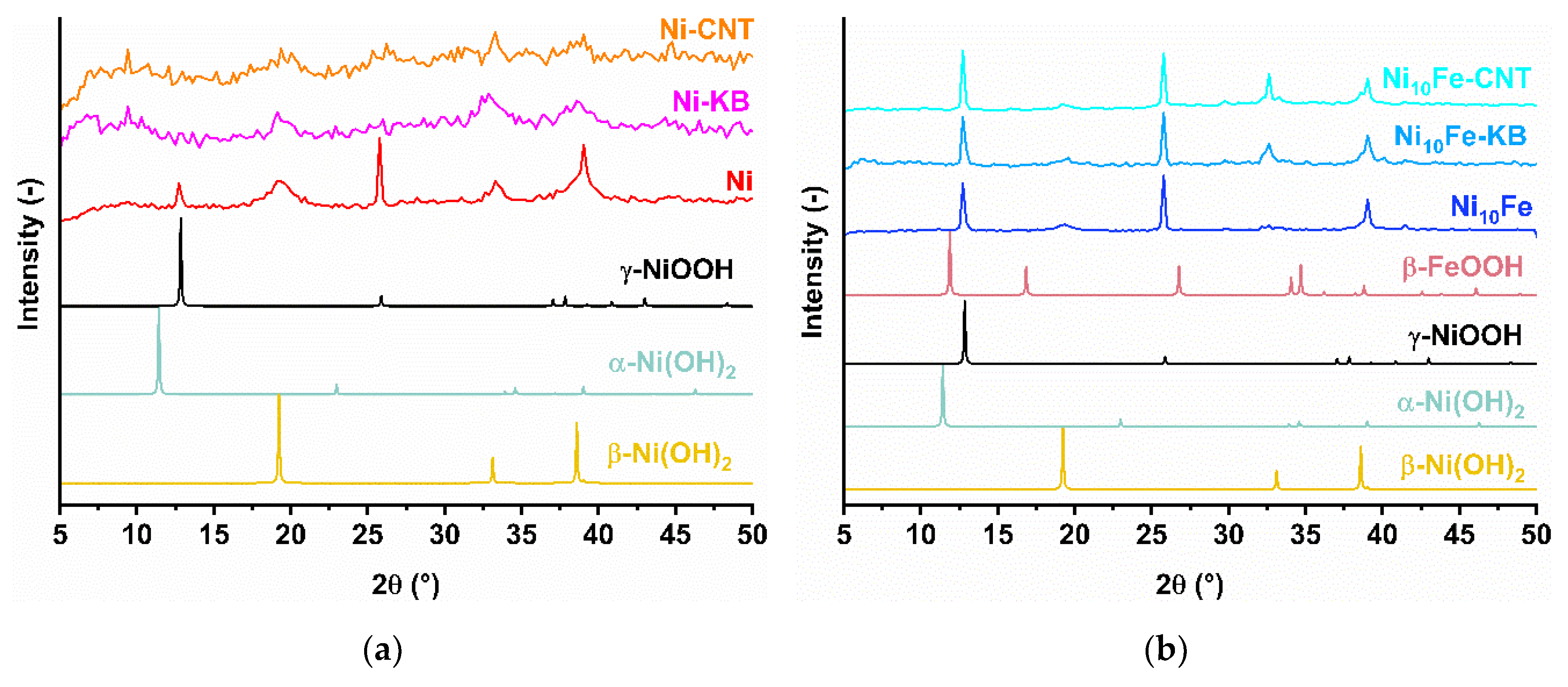

2.2. Electrocatalytical Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of the In Situ MOF-Composites

3.3. Materials Characterization

3.4. Electrocatalytic Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xin, Y.; Hua, Q; Li, C.; Zhu, H.; Gao, L.; Ren, X.; Yang, P.; Liu, A. Enhancing electrochemical performance and corrosion resistance of nickel-based catalysts in seawater electrolysis: focusing on OER and HER. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 23147–23178. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Rao, R.R.; Peng, J.; Huang, B.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Risch, M.; Xu, Z.J.; Shao-Horn, Y. Recommended Practices and Benchmark Activity for Hydrogen and Oxygen Electrocatalysis in Water Splitting and Fuel Cells. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Rui, K.; Zhu, J.; Dou, S. X.; Sun, W. Recent Progress on Nickel-Based Oxide/(Oxy)Hydroxide Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, R. Advanced Transition Metal-Based OER Electrocatalysts: Current Status, Opportunities, and Challenges. Small 2021, 17, 2100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Over, H. Fundamental Studies of Planar Single-Crystalline Oxide Model Electrodes (RuO2, IrO2) for Acidic Water Splitting. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8848–8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, C.C.L.; Jung, S.; Ferrer, I.M.; Chatman, S.M.; Peters, J.C.; Jaramillo, T.F. Benchmarking Hydrogen Evolving Reaction and Oxygen Evolving Reaction Electrocatalysts for Solar Water Splitting Devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4347–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jung, W. Recent advances in doped ruthenium oxides as high-efficiency electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2021, 9, 15506–15521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z; Shao, Q.; Xue, J.; Huang, B.; Niu, Z; Gu, H; Huang, X.; Lang, J. Multiple structural defects in ultrathin NiFe-LDH nanosheets synergistically and remarkably boost water oxidation reaction. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 310–316. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Bieberle-Hütter, A.; Brocks, G. Anti-Ferromagnetic RuO2: A Stable and Robust OER Catalyst over a Large Range of Surface Terminations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, N.; Han, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhai, C.; Chen, H.; Han, J.; Fang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Z. Nanoporous RuO2 characterized by RuO(OH)2 surface phase as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting in alkaline solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 881, 114955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jin, L.; Shang, H.; Xu, H.; Y. Shiraishi; Du, Y. Advances in engineering RuO2 electrocatalysts towards oxygen evolution reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Yan, Y.; Lai, S.; He, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, B.; Javanbakht, M.; Peng, X.; Chu, P.K. Ni3+-enriched nickel-based electrocatalysts for superior electrocatalytic water oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherevkoa, S.; Geigera, S.; Kasiana, O.; Kulyka, N.; Grote, J.-P.; Savan, A.; Ratna Shrestha, B.; Merzlikin, S.; Breitbach, B.; Ludwig, A.; Mayrhofer, K. J.J. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: A comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today 2016, 262, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beglau, T. H. Y.; Rademacher, L.; Oestreich, R.; Janiak, C. Synthesis of Ketjenblack Decorated Pillared Ni(Fe) Metal-Organic Frameworks as Precursor Electrocatalysts for Enhancing the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Molecules 2023, 28, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M. S.; Enman, L. J.; Batchellor, A. S.; Zou, S.; Boettcher, S. W. Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysis on Transition Metal Oxides and (Oxy)hydroxides: Activity Trends and Design Principles. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7549–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirez, J. M. P.; Carter, E. A. Unraveling Oxygen Evolution on Iron-Doped β-Nickel Oxyhydroxide: The Key Role of Highly Active Molecular-like Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartner, G.; Hein, D.; Bergmann, A.; Wendt, R.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Seidel, R. Insights into the electronic structure of Fe–Ni thin-film catalysts during the oxygen evolution reaction using operando resonant photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2023, 11, 8066–8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed-Ibrahim, J. A review on NiFe-based electrocatalysts for efficient alkaline oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources 2020, 448, 227375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lee, L. Y. S. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalysis: Catalyst or Precatalyst? ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdpour, S.; Fetzer, M. N. A.; Oestreich, R.; Beglau, T. H. Y.; Boldog, I.; Janiak, C. Bimetallic CPM-37(Ni,Fe) metal–organic framework: enhanced porosity, stability and tunable composition. Dalton Trans., 2024, 53, 4937–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y. J.; Kim, S.; Leung, V.; Kawashima, K.; Noh, J.; Kim, K.; Marquez, R. A.; Carrasco-Jaim, O. A.; Smith, L. A.; Celio, H.; Milliron, D. J.; Korgel, B. A.; Buddie Mullins, C. Effects of Electrochemical Conditioning on Nickel-Based Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10384−10399. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Park, G. S.; Lee, H. I.; Kim, S. T.; Cao, R.: Liu, M.; Cho, J. Ketjenblack Carbon Supported Amorphous Manganese Oxides Nanowires as Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Alkaline Solutions. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5362–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; He, X.; Li, H.; Zou, J.; Que, M.; Tian; J.; Qian, Y. Tunable metal–organic framework nanoarrays on carbon cloth constructed by a rational self-sacrificing template for efficient and robust oxygen evolution reactions. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 7090–7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul, P.; Abraham John, S. Size controlled synthesis of Ni-MOF using polyvinylpyrrolidone: New electrode material for the trace level determination of nitrobenzene. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 829, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, B.; Merkoçi, A. Carbon nanotubes and graphene in analytical sciences. Microchim. Acta 2012, 179, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, K.; Li, F.; Peng, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H. Co3O4/Co-N-C modified ketjenblack carbon as an advanced electrocatalyst for Al-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 30e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, G. Plastic Additives, Springer-Science + Business Media, Dordrecht, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S.; Moon, G.; Spieß, A.; Budiyanto, E.; Roitsch, S.; Tüysüz, H.; Janiak, C. A Highly-Efficient Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalyst Derived from a Metal-Organic Framework and Ketjenblack Carbon Material. ChemPlusChem 2021, 86, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinloch, I. A.; Suhr, J.; Lou, J.; Young R., J.; Ajayan, P. M. Composites with carbon nanotubes and graphene: An outlook. Science 2018, 362, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinadayalane, T. C.; Leszczynski, J. Remarkable diversity of carbon–carbon bonds: structures and properties of fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and graphene. Struct. Chem. 2010, 21, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, S. K.; Thomasa, B.; Karb, V. R. A comprehensive review on CNTs and CNT-reinforced composites: syntheses, characteristics and applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Lang, F.-F.; Pang, J.; Bu, X.-H. Recent progress in metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) for electrocatalysis Ind. Chem. Mater., 2023, 1, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, N.; Ge, L.; Bu, X.; Feng, P. Transition metal-based bimetallic MOFs and MOF-derived catalysts for electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction Energy Environ. Sci., 2021, 14, 1897–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Abazari, R.; Chen, J.; Tahir, M.; Kumar, A.; Ramadhan Ikreedeegh, R.; Rani, E.; Singh, H.; Kirillov, A. M. Bimetallic metal–organic frameworks and MOF-derived composites: Recent progress on electro- and photoelectrocatalytic applications Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 451, 214264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondermann, L.; Jiang, W.; Shviro, M.; Spieß, A.; Woschko, D.; Rademacher, L.; Janiak, C. Nickel-based metal-organic frameworks as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER). Molecules 2022, 27, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Mao, J.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Z.; Lai, Y. Metal–organic frameworks and their derivatives with graphene composites: preparation and applications in electrocatalysis and photocatalysis J. Mater. Chem. A, 2020, 8, 2934–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, S.; Yasmeen, G.; Shafiq, Z.; Abbas, A.; Manzoor, S.; Hussain, D.; Adel Pashameah, R.; Alzahrani, E. ; Alanazi; A. K.; Naeem Ashiq, M. Nickel-based nitrodopamine MOF and its derived composites functionalized with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for efficient OER applications Fuel, 2023, 331, 125881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadfalah, M.; Sedghi, A.; Hosseini, H.; Saber Mirhosseini, S. Synergic effect of physically-mixed metal organic framework based electrodes as a high efficient material for supercapacitors J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.-J.; Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Sun, X.-C.; Zhang, Y.W. In Situ Synthesis of NiO/CuO Nanosheet Heterostructures Rich in Defects for Efficient Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 16516–16523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniam, P.; Stock, N. Investigation of Porous Ni-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks Containing Paddle-Wheel Type Inorganic Building Units via High-Throughput Methods. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5085–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Yang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, H.; Yong, J.; Yu, L.; Luan, X.; Cui, M.; Zhang, X. ; Huang. X. Amorphous (Fe)Ni-MOF-derived hollow (bi)metal/oxide@N-graphene polyhedron as effectively bifunctional catalysts in overall alkaline Electrochimica Acta 2019, 318, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodjie, S. L.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Cai, W.; Li, C. Y.; Keating, M. Morphology and Crystallization Behavior of HDPE/CNT Nanocomposite J. Macromol. Sci. B, 45:2, 231–245. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, M.; Ma, Y.; Tan, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Hybridized Polyoxometalate-Based Metal Organic Framework with Ketjenblack for the Nonenzymatic Detection of H2O2. Chem. Asian, J. 2018, 13, 2054–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, B. P.; Talosig, A. R.; Rose, B.; Di Palma, G.; Patterson, J. P. Understanding and controlling the nucleation and growth of metal–organic frameworks Chem. Soc. Rev., 2023, 52, 6918–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazlan, N. A; Butt, F. S.; Lewis, A.; Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Huang, Y. The Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks in the Presence of Graphene Oxide: A Mini Review Membranes 2022, 12, 501. 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, H.; Hu, M.; Zhang, S. Classification and carbon structural transformation from anthracite to natural coaly graphite by XRD, Raman spectroscopy, and HRTEM. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2021, 249, 119286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.Q.; Lu, C.J.; Xia, Z.P.; . Zhou, Y.; Luo, Z. X-ray diffraction patterns of graphite and turbostratic carbon Carbon 2007, 45, 1686–1695. [CrossRef]

- Wade, C. R.; Dincă, M. Investigation of the synthesis, activation, and isosteric heats of CO2 adsorption of the isostructural series of metal–organic frameworks M3(BTC)2 (M = Cr, Fe, Ni, Cu, Mo, Ru). Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 7931–7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Boubeche, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Yan, K. Facile synthesis of Ni-, Co-, Cu-metal organic frameworks electrocatalyst boosting for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 72, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyani, N.; Siwatch, P.; Rana, S.; Sharma, K.; Tripathi, S.K. Study of electrochemical behaviour of binder-free nickel metal-organic framework derived by benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid for supercapacitor electrode Mater. Res. Bull., 2023, 165, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, F.; Chun, D.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. K. High yield synthesis of Ni-BTC metal–organic framework with ultrasonic irradiation: Role of polar aprotic DMF solvent. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.; Bienz, S.; Bigler, L.; Fox, T. Spektroskopische Methoden in der organischen Chemie, 9th ed.; Georg Thieme, Stuttgart, Germany, 2016.

- Pretsch, E.; Bühlmann, P.; Badertscher, M. Spektroskopische Daten Zur Strukturaufklärung organischer Verbindungen, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Song, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Shen, P.; Gao, L.; Wei, R.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, G. 3D-monoclinic M–BTC MOF (M = Mn, Co, Ni) as highly efficient catalysts for chemical fixation of CO2 into cyclic carbonates. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 58, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, L.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Nasir, H.; Zaman, N.; Talha, K. Electrochemical synergies of Fe–Ni bimetallic MOF CNTs catalyst for OER in water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 850, 156583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, G.-T.; Pham, M.-H.; Do, T.-O. Synthesis and engineering porosity of a mixed metal Fe2Ni MIL-88B metal–organic framework. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N. T. K.; Chung, Y.-M. Ethylene oligomerization over mesoporous FeNi-BTC catalysts: Effect of the textural properties of the catalyst on the reaction performance Mol. Catal. 2023, 541, 113094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beglau, T. H. Y.; Fei, Y.; Janiak, C. Microwave-Assisted Ultrafast Synthesis of Bimetallic Nickel- Cobalt Metal-Organic Frameworks for Application in the Oxygen Evolution Reaction Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202401644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eletskiĭ, A. V. Sorption properties of carbon nanostructures Physics–Uspekhi 2004, 47, 1119–1154. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; He, H.; Zhao, K.; He, Z.; Liu, S. Morphology-dependent electrochemical performance of Ni-1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate metal-organic frameworks as an anode material for Li-ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 530, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, G.; Wen, H.; Guan, X.; Sun, X.; Feng, H.; Tian, W.; Zheng, D.; Cheng, X.; Yao, Y. Constructing a highly oriented layered MOF nanoarray from a layered double hydroxide for efficient and long-lasting alkaline water oxidation electrocatalysis J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8771–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgopolova, E. A.; Brandt, A. J.; Ejegbavwo, O. A.; Duke, A. S.; Maddumapatabandi, T. D.; Galhenage, R. P.; Larson, B. W.; Reid, O. G.; Ammal, S. C.; Heyden, A.; Chandrashekhar, M.; Stavila, V.; Chen, D. A.; Shustova, N. B. Electronic Properties of Bimetallic Metal−Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Tailoring the Density of Electronic States through MOF Modularity J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5201–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; He, C.-T.; Yin, H.; An, P.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.; Gao, C.; Zhang, L.; Lv, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Khattak, A. M.; Khan, N. A.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Z. Ultrathin metal–organic framework nanosheets for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil Raja, D.; Lin, H.-W.; Lu, S.-Y. Synergistically well-mixed MOFs grown on nickel foam as highly efficient durable bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting at high current densities Nano Energy 2019, 57, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.-J.; Li, F.; Xie, J.; Li, Y.; He, J.-B. Trace Fe Incorporation into Ni-(oxy)hydroxide Stabilizes Ni3+ Sites for Anodic Oxygen Evolution: A Double Thin-Layer Study Langmuir 2020, 36, 5126–5133. [CrossRef]

- Li, X; Wei, D. ; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Unveiling the real active sites of Ni based metal organic framework electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction Electrochimica Acta 2020, 354, 136682. [CrossRef]

- Enman, L. J.; Burke, M. S.; Batchellor, A. S.; Boettcher, S. W. Effects of Intentionally Incorporated Metal Cations on the Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalytic Activity of Nickel (Oxy)hydroxide in Alkaline Media ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2416–2423. [CrossRef]

- Beglau, T. H. Y.; Fetzer, M. N. A.; Boldog, I.; Heinen, T.; Suta, M.; Janiak, C.; Yücesan, G. Exceptionally Stable And Super-Efficient Electrocatalysts Derived From Semiconducting Metal Phosphonate Frameworks Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202302765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.; Chandran, M.; Dhanusuraman, R. A comprehensive review on the electrochemical parameters and recent material development of electrochemical water splitting electrocatalysts RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3843–3876. [CrossRef]

- Naik Shreyanka, S.; Theerthagiri, J.; Lee, S. J.; Yu, Y.; Choi, M. Y Multiscale design of 3D metal–organic frameworks (M-BTC, M: Cu, Co, Ni) via PLAL enabling bifunctional electrocatalysts for robust overall water splitting. Chem. Eng. J 2022, 446, 137045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Sato, E. Electrocatalytic properties of transition metal oxides for oxygen evolution reaction. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1986, 14, 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Y. P.; Santos, A.; Bueno, P. R. Quantum Mechanical Meaning of the Charge Transfer Resistance J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 3151–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Stavrakis A. K., Stojanović, G. M. A Low-Complexity Method for Parameter Estimation of the Simplified Randles Circuit With Experimental Verification IEEE Sens. J., 2021, 21, 24209–24217. 2021, 21, 24209–24217. [CrossRef]

- Anantharaj, S.; Noda, S. Appropriate Use of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy in Water Splitting Electrocatalysis ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 2297–2308. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, C.; Liao, J.; Su, Y.; Xue, X. , Xing, W. Study of ruthenium oxide catalyst for electrocatalytic performance in oxygen evolution J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006, 247, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Giancola, S.; Khezri, B.; Nieto-Castro, D.; Redondo, J.; Schiller, F.; Barja, S.; Spadaro, M. C.; Arbiol, J.; Garcés-Pineda, F.A.; Galán-Mascarós, J. R. A survey of Earth-abundant metal oxides as oxygen evolution electrocatalysts in acidic media (pH <1) EES Catal., 2023, 1, 765–773. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Tran, D.T.; Li, J.; Chu, D. Ru@RuO2 Core-Shell Nanorods: A Highly Active and Stable Bifunctional Catalyst for Oxygen Evolution and Hydrogen Evolution Reactions Energy Environ. Mater. 2019, 2, 201–208. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).