Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

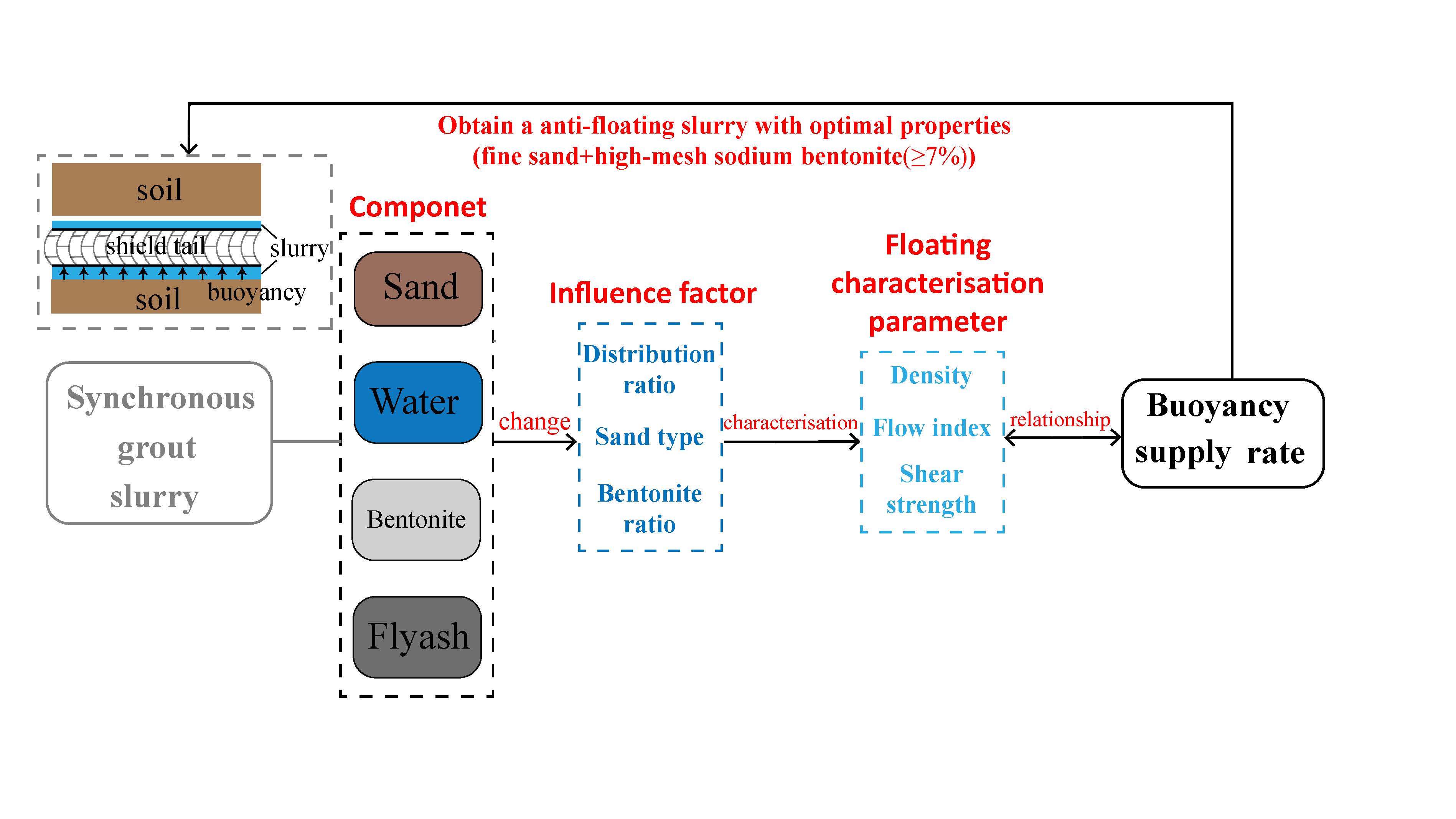

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

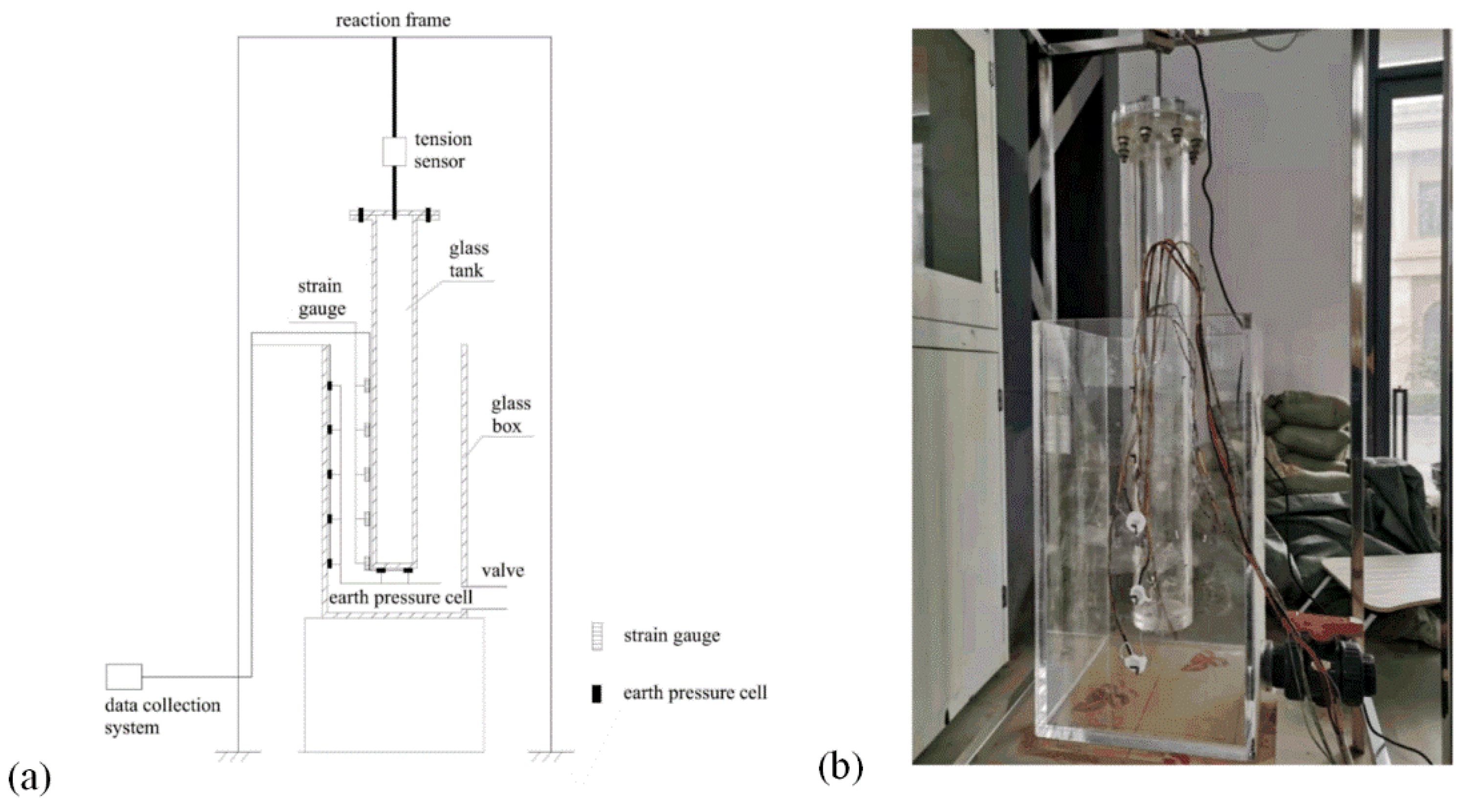

2.2. Equipment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Trial Test

3.2. Effect of Grout Composition on Characterisation Parameters of Uplift

3.3. Experiment on the Relationship Between Buoyancy Characterisation Parameters and Buoyancy

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Verification of Floating Characterisation Parameters

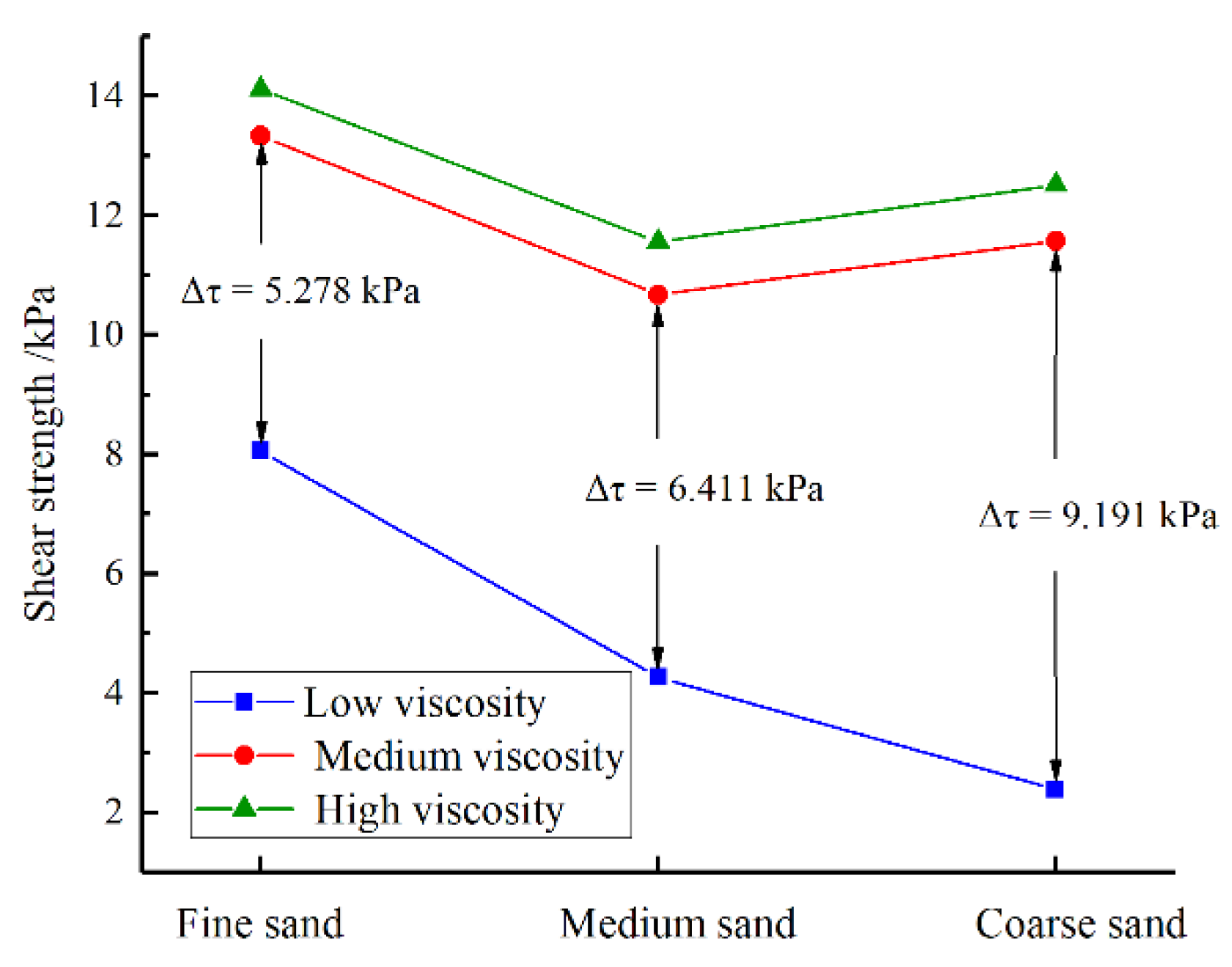

4.2. Effect of Slurry Components on Experimental Results

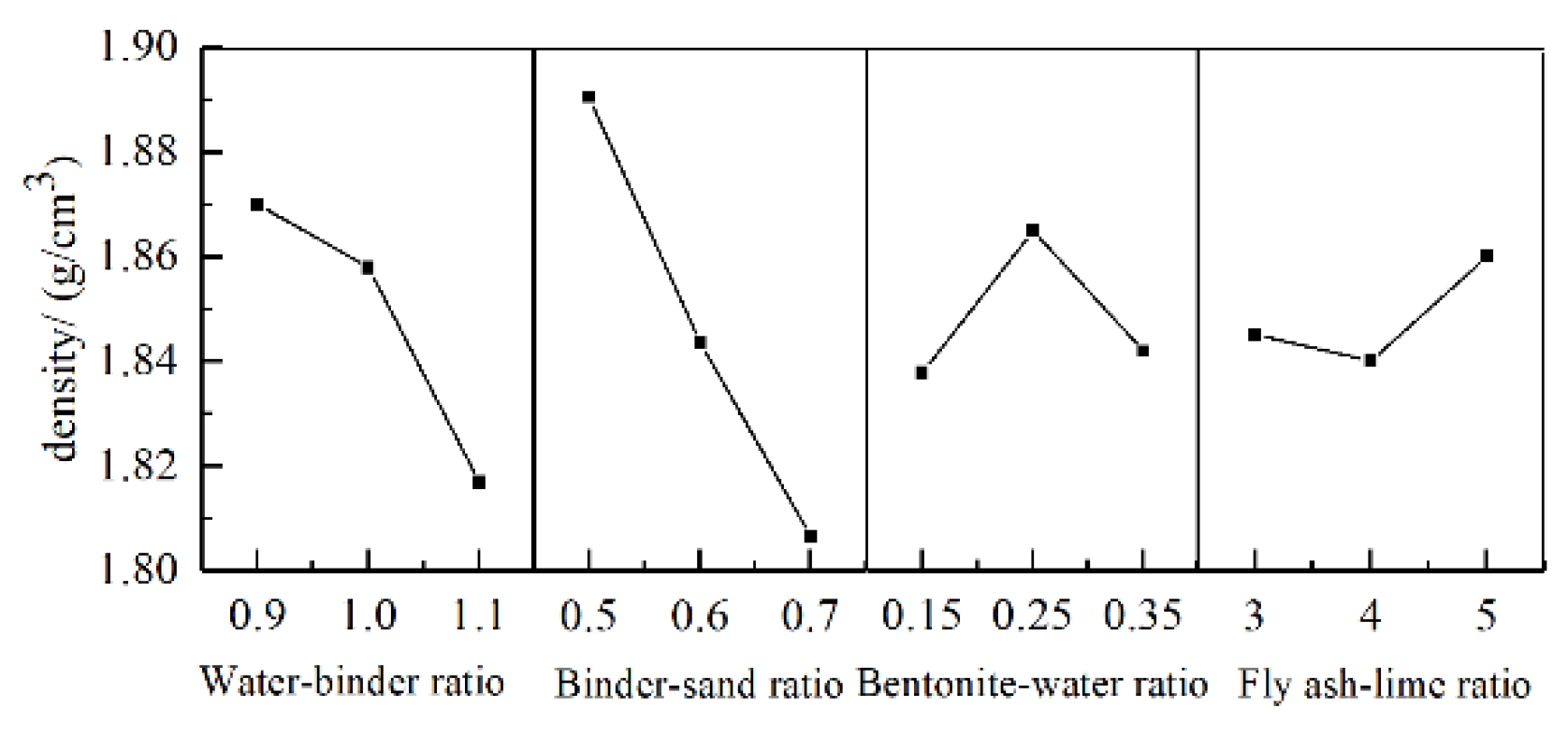

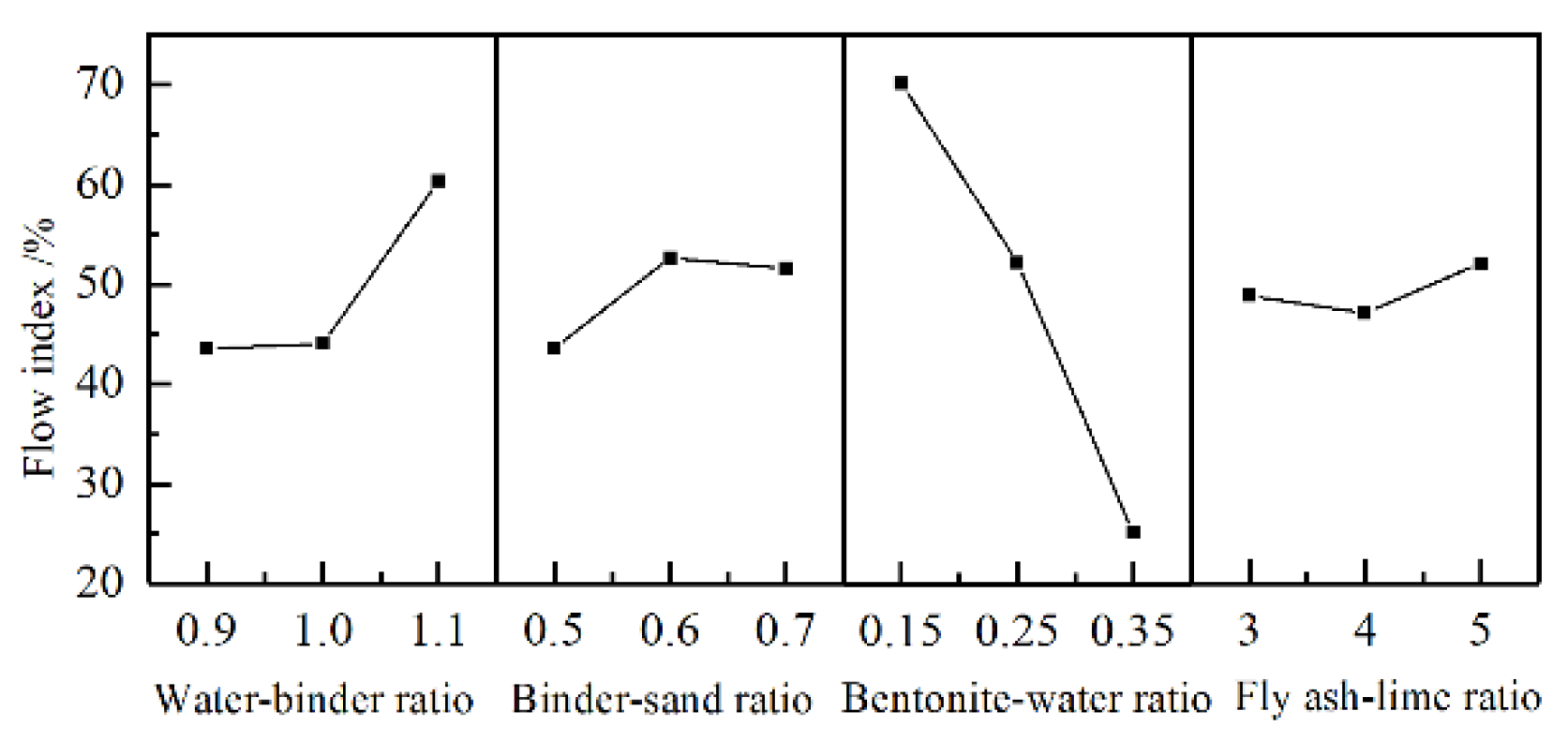

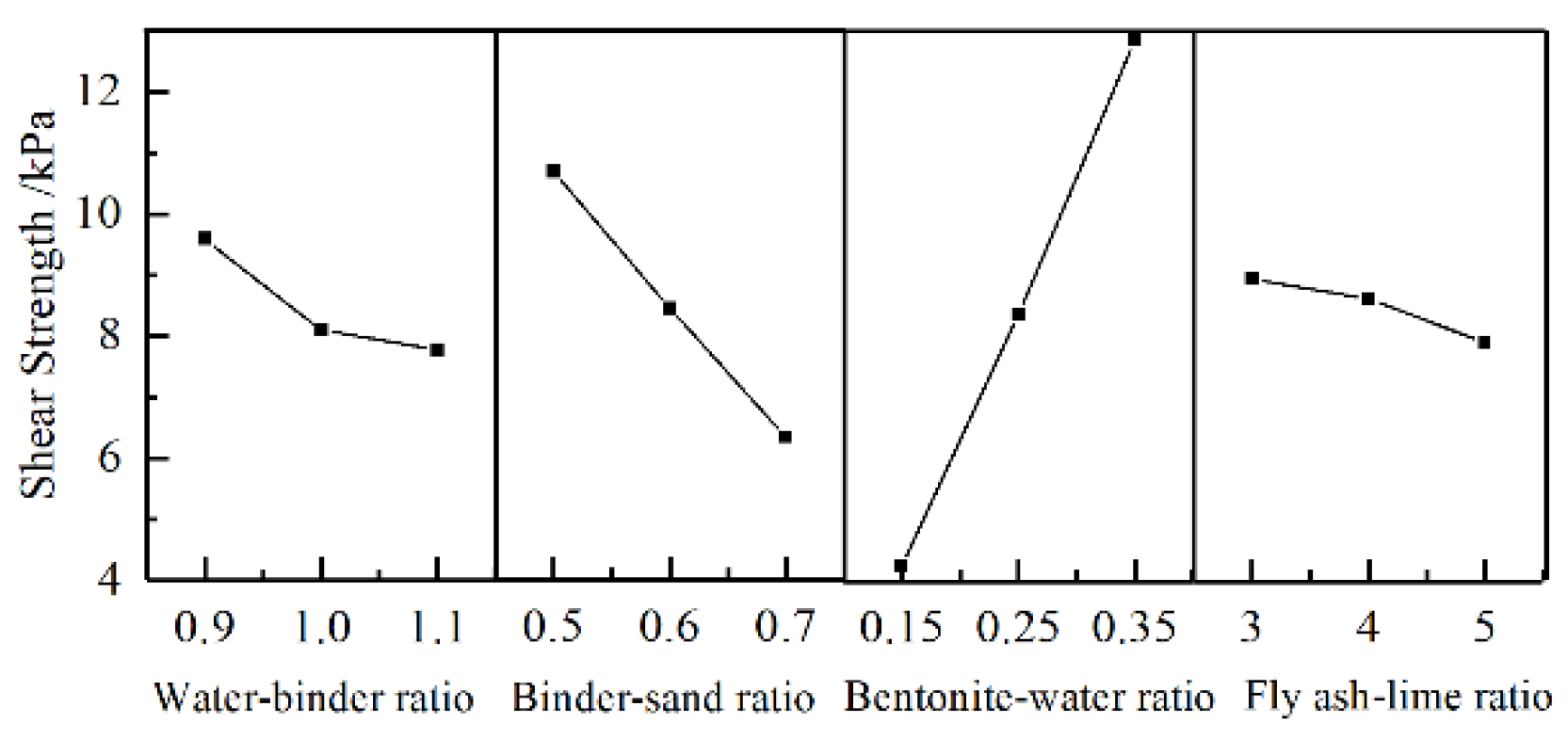

4.2.1. Influence of Slurry Ratio

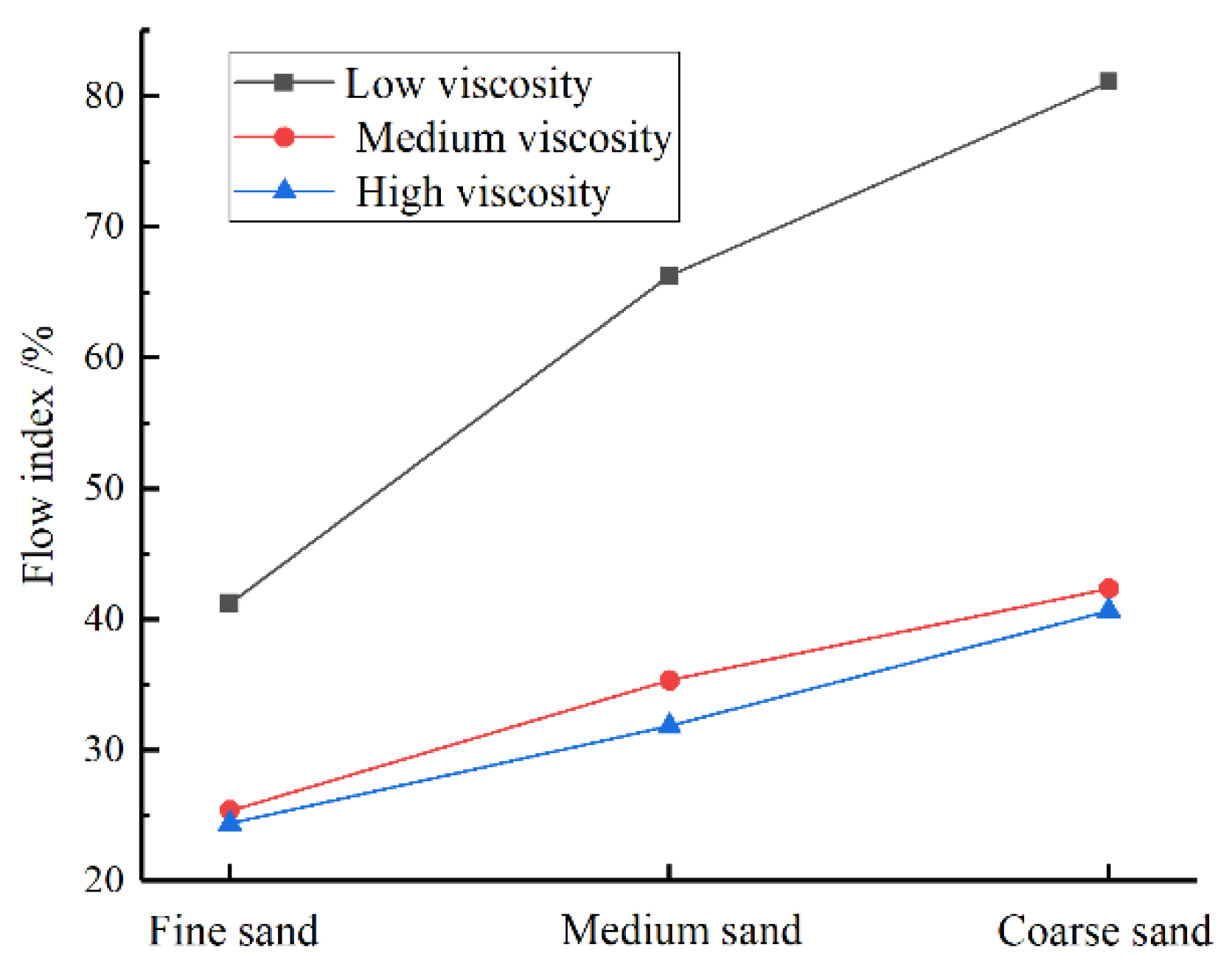

4.2.2. Influence of Slurry Composition

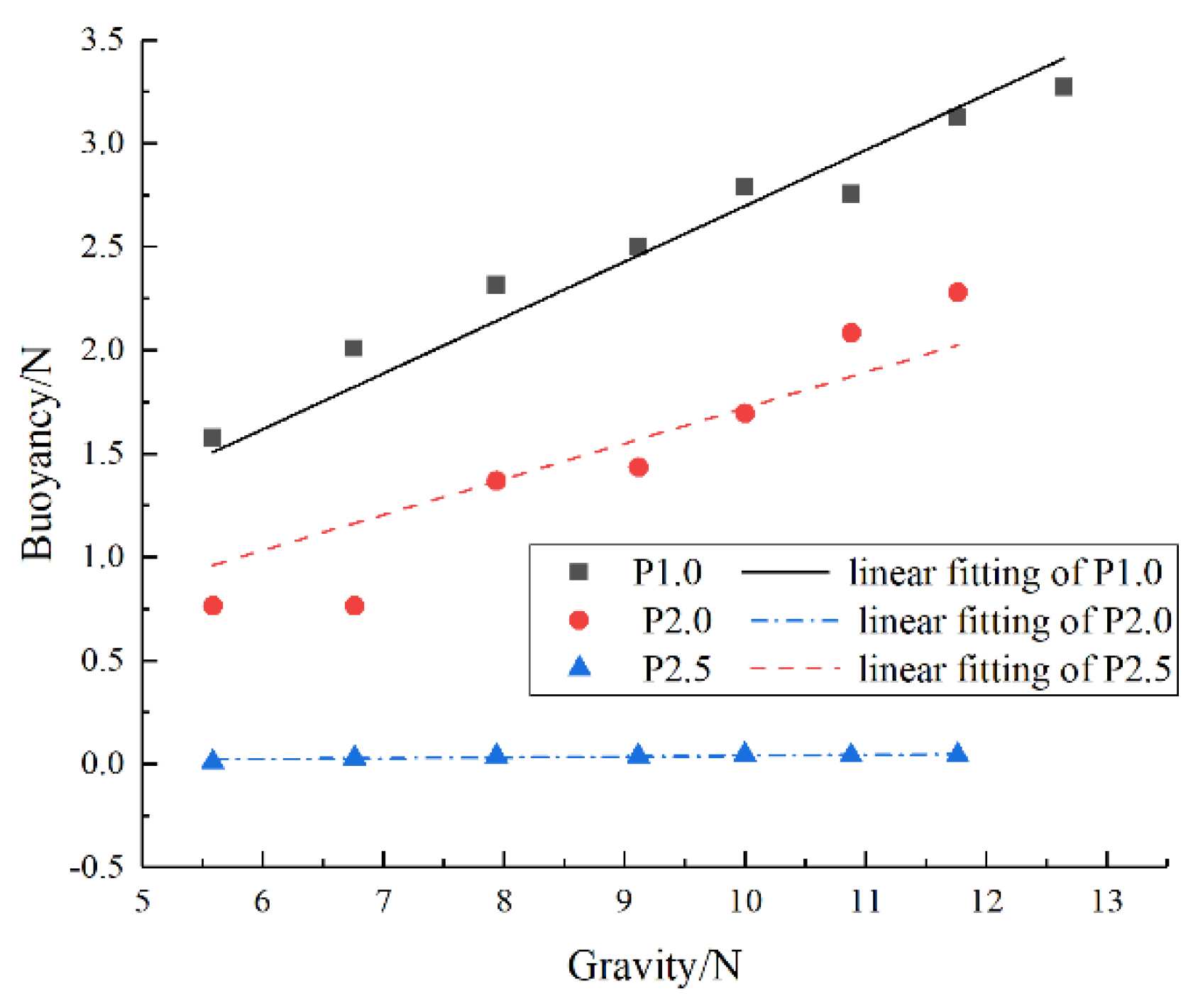

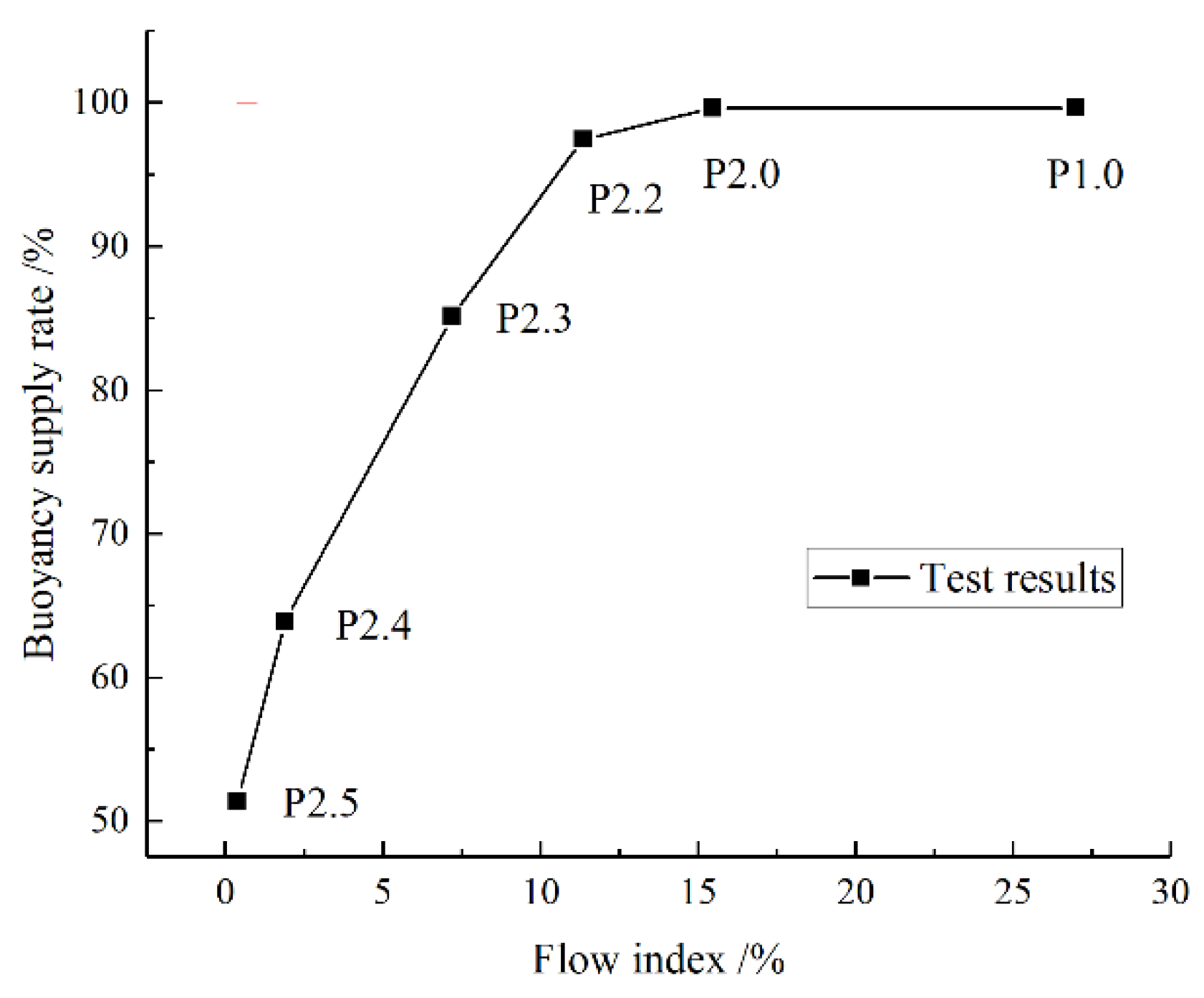

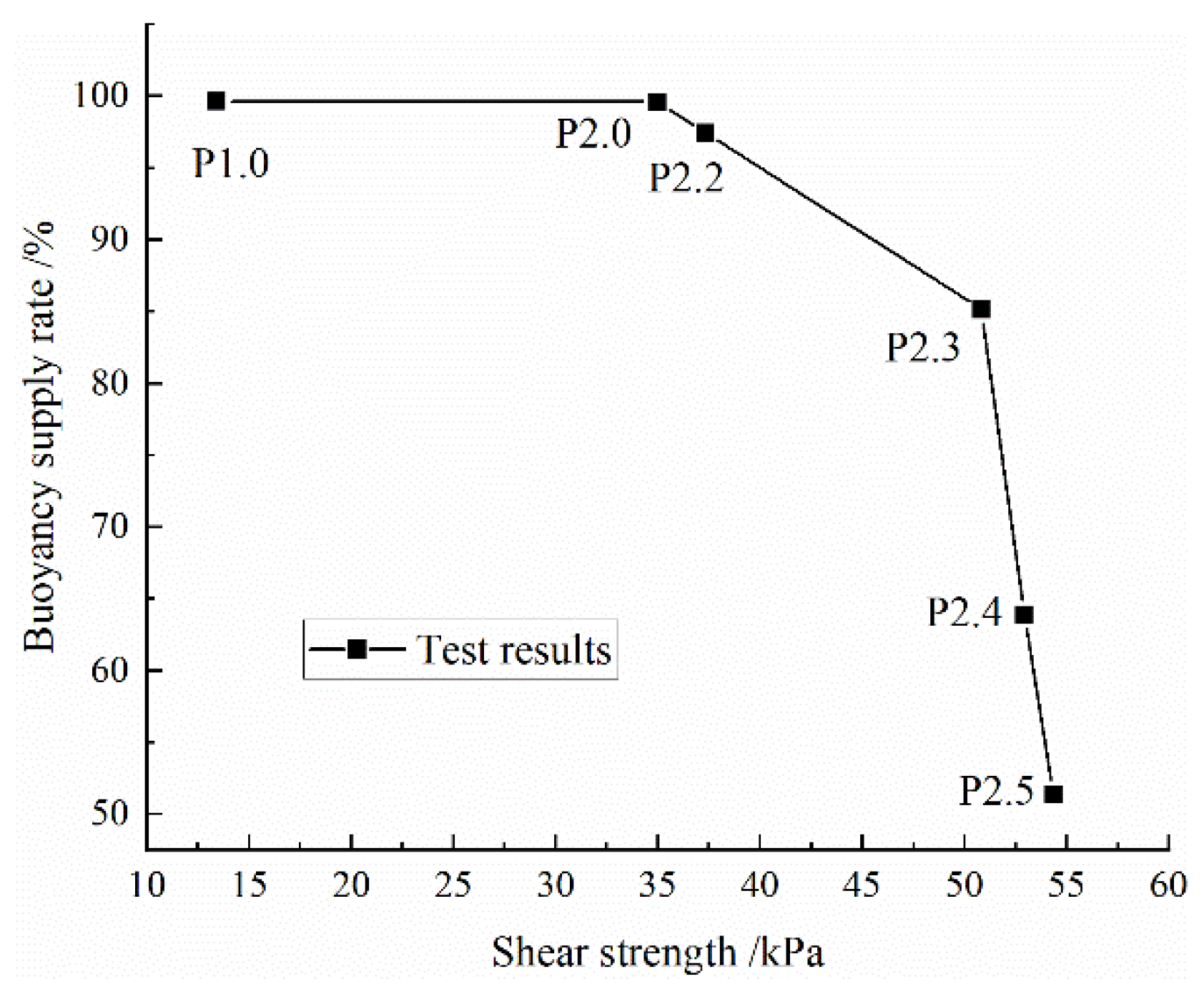

4.3. Relationship Between Buoyancy Characterisation Parameters and Buoyancy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faramarzi, L.; Rasti, A.; Abtahi, S.M. , An experimental study of the effect of cement and chemical grouting on the improvement of the mechanical and hydraulic properties of alluvial formations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, W.; Ding, W.T.; Wang, C.Z.; Yu, W.D.; Wang, Z.C. , Research on the Antifloating Performance of Grouts with Different Mix Proportions in Synchronous Grouting of Shield Tunnels: From Laboratory Tests to Theoretical Calculations. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04023279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-M.; Liu, J.-H.; Wang, R.-L.; Li, Z.-M. , Shield tunneling and environment protection in Shanghai soft ground. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2009, 24, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Hamza, O.; Davies-Vollum, K.S.; Liu, J.Q. , Repairing a shield tunnel damaged by secondary grouting. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2018, 80, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Fu, J.; Yang, J.; Ou, X.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Y. , Formulation and performance of grouting materials for underwater shield tunnel construction in karst ground. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirlaw, J.N.; Richard, D.P.; Ramond, P.; Longchamp, P. , Recent experience in automatic tail void grouting with soft ground tunnel boring machines. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2004, 19, 446. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.Q.; Duan, C.; Zhu, Y.H.; Zhao, T.C.; Huang, D.Z.; Li, P.N. , The behavior of synchronous grouting in a quasi-rectangular shield tunnel based on a large visualized model test. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2019, 83, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xu, J.F.; Xie, X.Y.; Zeng, H.B.; Xu, W.J.; Niu, G.; Xiao, Z.L. , Disaster mechanism analysis for segments floating of large-diameter shield tunnel construction in the water-rich strata: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.W.; Zhang, X.L.; Chen, Y.B.; Wei, Y.J.; Ding, Y. , Prediction of maximum upward displacement of shield tunnel linings during construction using particle swarm optimization-random forest algorithm. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science A 2024, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.L.; Xu, Z.Z.; Geng, D.X.; Dong, J.L.; Liao, Y.Q. , Optimization of Grouting Material for Shield Tunnel Antifloating in Full-Face Rock Stratum in Nanchang Metro Construction in China. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yuan, D.J.; Jin, D.L.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Han, B.Y.; Mao, J.H. , Shield kinematics and its influence on ground settlement in ultra-soft soil: a case study in Suzhou. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 1887–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Chen, J. , Experimental Research on the Floating Amount of Shield Tunnel Based on the Innovative Cumulative Floating Amount Calculation Method. Buildings 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Huang, X.M.; Gao, S.J.; Yin, Y.H. , Study on the Floating of Large Diameter Underwater Shield Tunnel Caused by Synchronous Grouting. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 2041924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, R. , Accident analysis of segment floating in soft stratum shield tunnel. Journal of Municipal Technology 2014, 32, 70–72. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.Y.; Yu, L.C.; Chen, J.; Jin, J.W.; Li, P.L.; Li, C.L.; Tian, Y.F. , In situ test analysis of segment uplift and dislocation of large-diameter slurry shield tunnel in silty clay. Journal of Railway Science and Engineering 2021, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; He, Z.H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.S.; Li, D.J. , Recycle application of the shield waste slurry in backfill grouting material: a case study of a slurry shield tunnelling in the river-crossing Fuzhou metro. Modern Tunnelling Technology 2019, 56, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.Y.; Lai, J.X.; Wang, L.X.; Wang, K. , A literature review on properties and applications of grouts for shield tunnel. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.F.; Xu, X.Y.; Huang, P.; He, J.; Li, L.Q. , Mechanism and control of segment floating of shield tunnel based on Newtonian kinematics. Construction Technology 2020, 49, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bezuijen, A.; Talmon, A.M. , Grout pressures around a tunnel lining, influence of grout consolidation and loading on lining. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2004, 19, 443–444. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.Q. , Anti-buoyancy technologies of extra-large slurry shield tunnel. Underground Engineering and Tunnels.

- Sonebi, M.; Lachemi, M.; Hossain, K.M.A. , Optimisation of rheological parameters and mechanical properties of superplasticised cement grouts containing metakaolin and viscosity modifying admixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Q.; Ma, Q.L.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, L.L. , Grouting performance improvement for natural hydraulic lime-based grout via incorporating silica fume and silicon-acrylic latex. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K. Study and application on high property grouting material used in synchronous grouting of shield tunnelling. Wuhan University of Technology, 2007.

- Abd Elaty, M.A.A.; Ghazy, M.F. , Fluidity evaluation of fiber reinforced-self compacting concrete based on buoyancy law. HBRC Journal 2018, 14, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, N.; Rincón, A.; Roether, J.A.; Ercole, P.; Bernardo, E.; Boccaccini, A.R. , Extensive reuse of soda-lime waste glass in fly ash-based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 188, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaleux, F.; Py, X.; Olives, R.; Dominguez, A. , Enhancement of geothermal borehole heat exchangers performances by improvement of bentonite grouts conductivity. Appl. Therm. Eng. -34.

- Aboulayt, A.; Jaafri, R.; Samouh, H.; El Idrissi, A.C.; Roziere, E.; Moussa, R.; Loukili, A. , Stability of a new geopolymer grout: Rheological and mechanical performances of metakaolin-fly ash binary mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajalloeian, R.; Matinmanesh, H.; Abtahi, S.M.; Rowshanzamir, M. , Effect of Polyvinyl Acetate Grout Injection on Geotechnical Properties of fine Sand. Geomech. Geoeng. 2013, 8, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggeri, C.; Fenoglio, T.M.; Vinai, R. , Tunnel spoil classification and applicability of lime addition in weak formations for muck reuse. Tunnelling Underground Space Technol. 2014, 44, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chu, Y.S.; Seo, S.K.; Kim, J.H.J. , The non-shrinkage grout to use ground fly ash as admixture. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2018, 19, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Bezuijen, A.; Sanders, M.P.M.; Den Hamer, D. , Parameters that influence the pressure filtration characteristics of bentonite grouts. Geotechnique 2009, 59, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; El Mohtar, C.S. , Groutability of Granular Soils Using Bentonite Grout Based on Filtration Model. Transp. Porous Media 2014, 102, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.K.; Tan, C.S.; Chen, K.P.; Lee, M.L.; Lee, W.P. , Effect of different sand grading on strength properties of cement grout. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

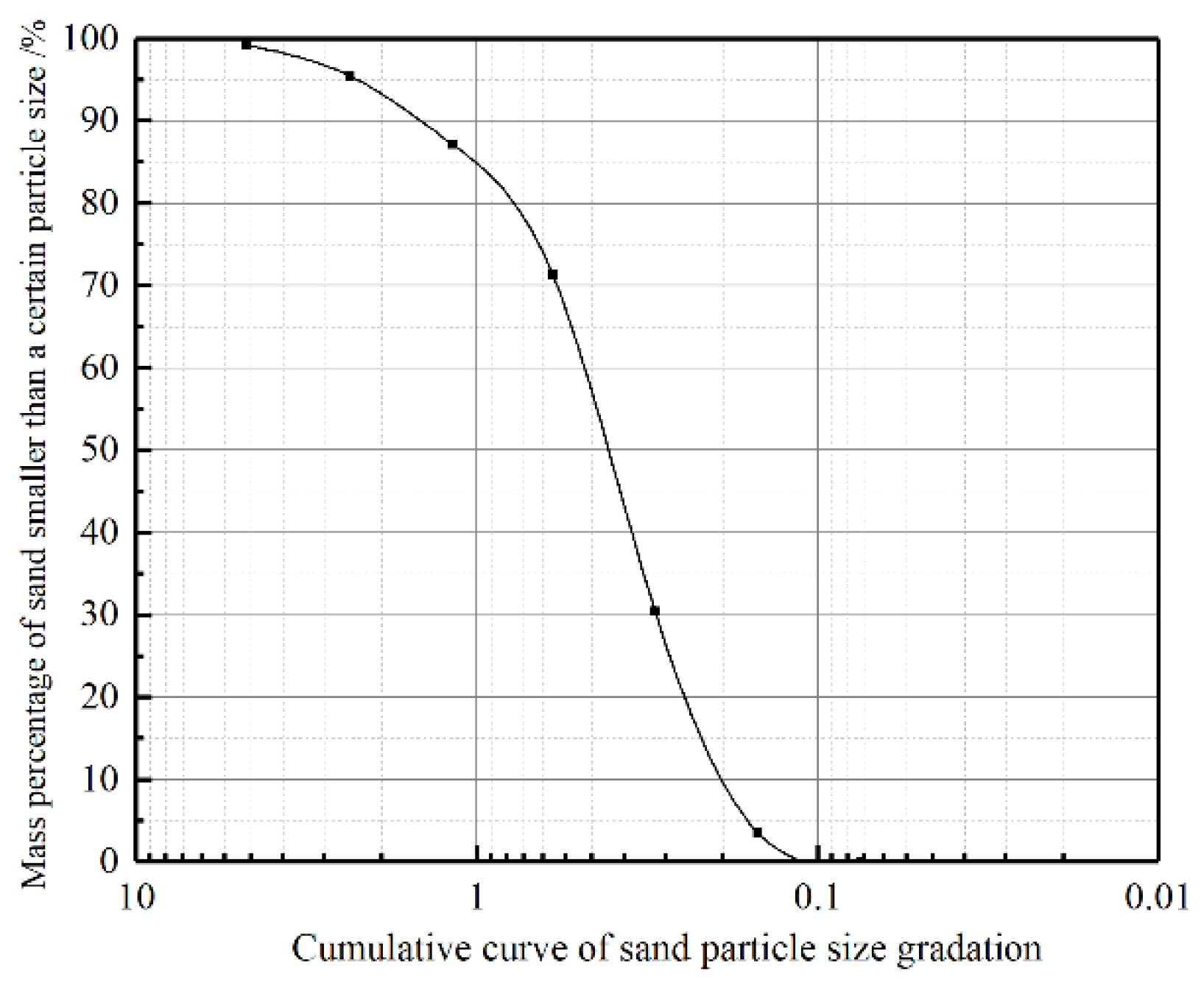

| Component | Performance indexes |

| Fly ash | First-grade fly ash; 0.045 mm square hole sieve allowance ≤ 12%; moisture content ≤ 1% |

| Slaked lime | Calcium hydroxide content ≥ 85%; 320 mesh screen allowance≤ 0.5% |

| Sand | Desalinated sea sand; fineness modulus = 2.1; sieve 4.75 mm before screening |

| Bentonite | Sodium-based; 95% pass-through 400 mesh screens; the main mineral mass composition is montmorillonite 78.5%, quartz 12.3%, and feldspar 5.6% with an initial water content of 10.8% |

| Water | Underground water; pH = 7.0; tasteless |

| Grout material ratio | Sand | Water | Slaked lime | Fly ash | Bentonite |

| P1.0 | 53.50 | 19.11 | 5.10 | 19.11 | 3.18 |

| Number | Water–binder ratio | Binder–sand ratio | Bentonite–water ratio | Fly ash–lime ratio |

| 1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 3.0 |

| 2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.25 | 4.0 |

| 3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.35 | 5.0 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 5.0 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.35 | 3.0 |

| 6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.15 | 4.0 |

| 7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.35 | 4.0 |

| 8 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.15 | 5.0 |

| 9 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.25 | 3.0 |

| Number | Sand | Bentonite |

| 1 | Fine sand | Low viscosity |

| 2 | Fine sand | Medium viscosity |

| 3 | Fine sand | High viscosity |

| 4 | Medium sand | Low viscosity |

| 5 | Medium sand | Medium viscosity |

| 6 | Medium sand | High viscosity |

| 7 | Coarse sand | Low viscosity |

| 8 | Coarse sand | Medium viscosity |

| 9 | Coarse sand | High viscosity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).