1. Introduction

Black holes provide a unique theoretical laboratory where the principles of general relativity, quantum field theory, and thermodynamics converge. Since the pioneering works of Bekenstein [

1] and Hawking [

2], it has been established that black holes possess entropy proportional to the area of the event horizon, given by the Bekenstein–Hawking formula:

where

A is the horizon area in Planck units. This relation forms the foundation of black hole thermodynamics and has profound implications for our understanding of quantum gravity.

However, it is widely expected that quantum gravitational effects modify this semiclassical entropy–area relation. Various approaches to quantum gravity—including string theory [

3], loop quantum gravity [

4], the generalized uncertainty principle (GUP) [

5,

6], and noncommutative geometry [

7,

8]—predict corrections involving logarithmic, inverse-area, or non-polynomial terms:

with model-dependent coefficients

capturing leading-order quantum corrections.

Among the phenomenological modifications proposed, the idea of a scale-dependent entropy correction has gained attention. In this work, we introduce a square-root deformation of the entropy–area relation of the form:

where

is a small dimensionless parameter encoding quantum gravitational effects. Such a correction may emerge from effective models with minimal length, modified dispersion relations, or higher-order curvature effects, and leads to non-trivial thermodynamic consequences even at intermediate mass scales.

We explore the impact of this deformation on Schwarzschild black hole thermodynamics, deriving analytic expressions for the temperature, specific heat, and evaporation rate. The analysis reveals the emergence of a stable remnant, which is of particular interest in the context of the black hole information paradox [

9] and as a potential dark matter candidate [

10].

This work provides a minimal yet insightful extension of black hole thermodynamics, serving as a bridge between semiclassical gravity and full quantum gravitational regimes.

2. Modified Black Hole Thermodynamics

In this section, we study the thermodynamic properties of Schwarzschild black holes under a deformation of the classical Bekenstein–Hawking entropy. The proposed deformation takes the form:

where

is a small, dimensionless parameter encoding leading-order quantum gravitational effects. This form is inspired by recent investigations into entropy corrections arising from quantum geometry [

11,

12] and scale-dependent gravity [

13].

2.1. Entropy as a Function of Mass

For a non-rotating, uncharged Schwarzschild black hole, the horizon area is given by:

where

M is the ADM mass of the black hole (in Planck units). Substituting into Eq. (

4), the entropy becomes:

2.2. Modified Hawking Temperature

From the first law of black hole thermodynamics:

we differentiate Eq. (

6):

This differs from the classical result , and is lower for any , consistent with quantum gravity-induced suppression of radiation.

2.3. Modified Specific Heat

The heat capacity is given by:

This expression shows that as , indicating thermodynamic stabilization and avoidance of the classical divergence at small mass.

2.4. Evaporation Rate

Assuming the black hole radiates approximately as a blackbody, the mass loss rate is given by:

Substituting the expressions for

and Eq. (

8), we obtain:

This clearly demonstrates a significant suppression of radiation at low mass, implying a remnant with non-zero mass. This is consistent with predictions from the GUP framework [

14,

15] and noncommutative geometry [

16].

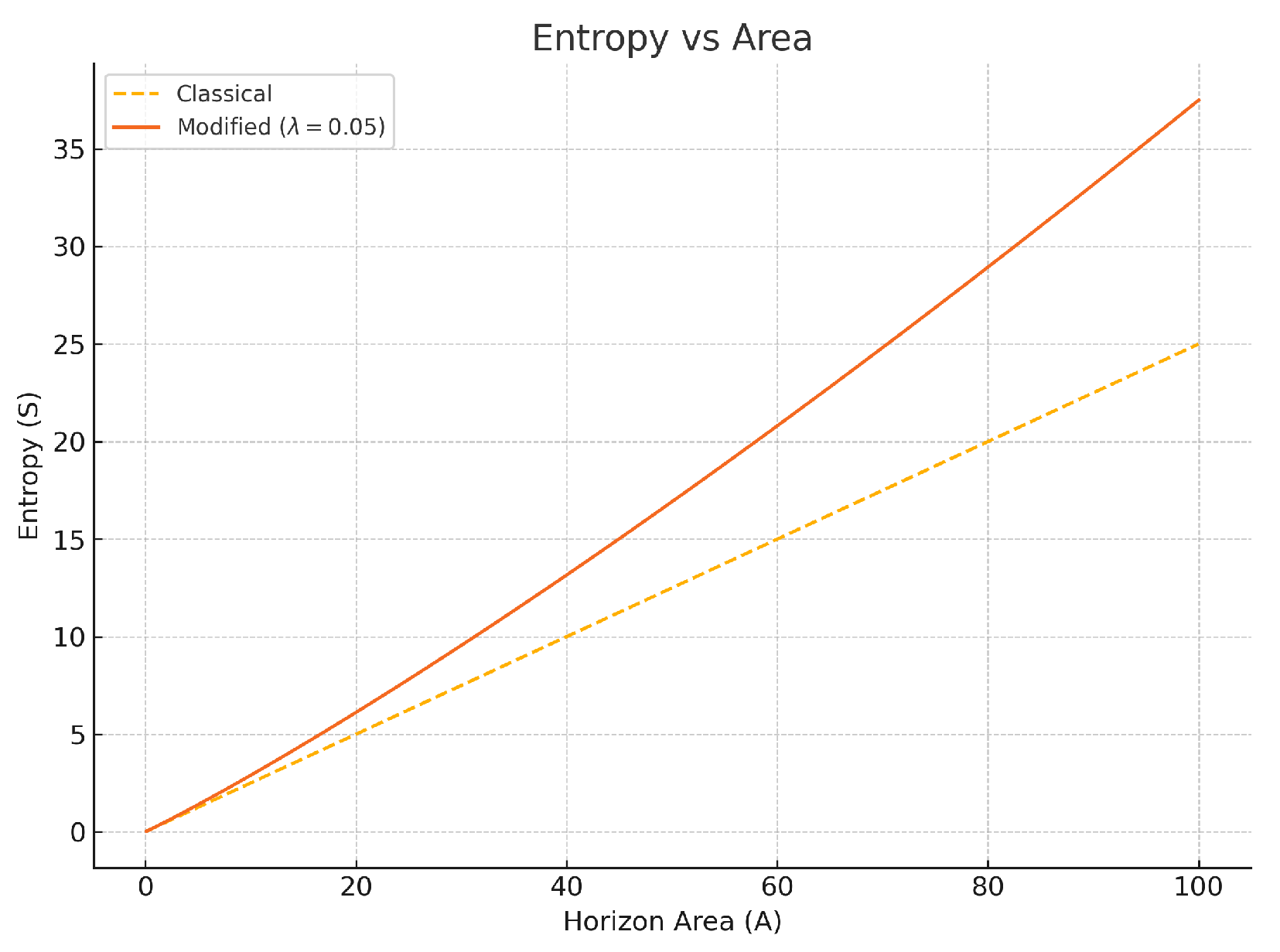

2.5. Entropy–Area Relation

For completeness, we compare the deformed entropy [Eq. (

4)] with the classical Bekenstein–Hawking entropy, as a function of the horizon area

A. The modified entropy grows faster than linearly due to the additional

term:

This implies enhanced entropy production at large horizon area, consistent with predictions from scale-dependent gravity [

13] and quantum-corrected entropy models [

12].

Figure 1 shows a comparison between the classical and modified entropy functions. For small

A, the correction is negligible, but for intermediate and large values, the deviation becomes significant.

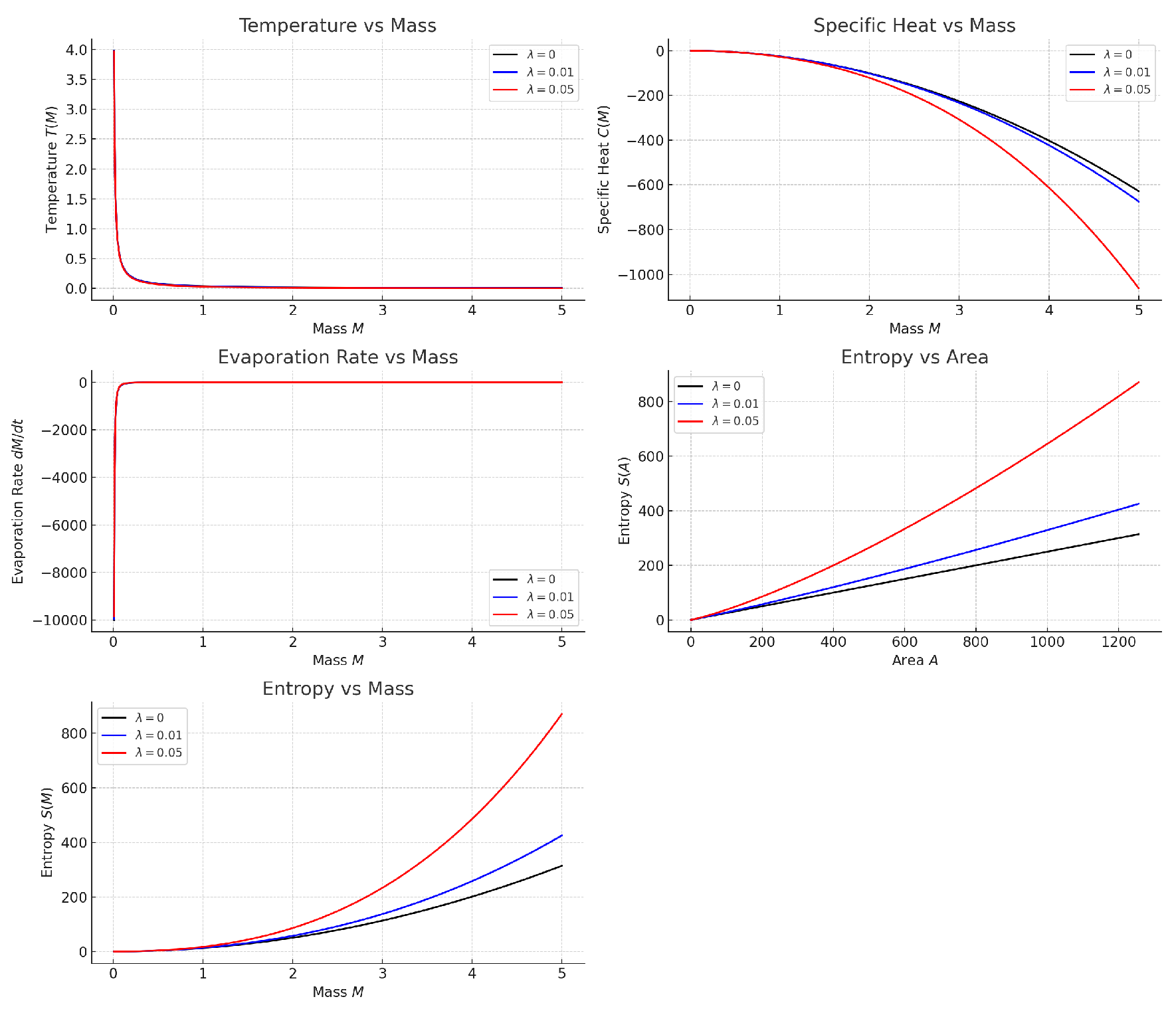

Figure 2 illustrates the behavior of temperature, specific heat, and evaporation rate in the deformed case compared to the classical Schwarzschild scenario. The suppression of both temperature and radiation at small masses is indicative of quantum backreaction and the formation of stable remnants.

3. Discussion and Implications

The square-root deformation of the entropy–area law [Eq. (

4)] leads to several important physical consequences. In what follows, we explore three key aspects: thermodynamic stability and remnant formation, connections to quantum gravity frameworks, and potential observational signatures.

3.1. Thermodynamic Stability and Remnant Formation

From Eq. (

11), the heat capacity

approaches zero as

, in stark contrast to the classical divergence

. This signals a thermodynamic stabilization at small mass scales, halting the runaway increase of temperature. Simultaneously, the evaporation rate [Eq. (

14)]

vanishes as

, implying the black hole asymptotically approaches a finite remnant mass

. Such remnants have been discussed extensively in the context of generalized uncertainty principles (GUP) and minimal-length scenarios [

5,

12,

15], and also appear in noncommutative geometry models [

7,

11].

3.2. Quantum Gravity Interpretation

Although introduced phenomenologically, the term can be motivated from multiple approaches:

Effective field theories with higher-curvature terms: One-loop corrections in Gauss–Bonnet or Lovelock gravity generate non-linear area terms in the entropy expansion [

17,

18].

Scale-dependent couplings: Renormalization group improvements to classical solutions induce scale-dependent Newton’s constant, leading to entropy deformations of the form

[

13].

Modified dispersion relations and GUP: Quantum gravity phenomenology often predicts a minimal length, which yields corrections scaling as fractional powers of area [

6,

8].

A derivation of Eq. (

4) from any of these approaches would bolster the model’s theoretical foundation—an important direction for future work.

3.3. Cosmological and Observational Relevance

3.3.0.1. Primordial Black Hole Remnants:

Primordial black holes (PBHs) formed in the early universe with initial masses

would today be in their final evaporation stages. In our model, these would settle into stable remnants of mass

(in Planck units). Constraints on PBH dark matter abundances then translate directly into limits on

[

10,

19].

Gravitational Wave Echoes and Entropy Balance:

Black hole mergers probe the total entropy budget before and after coalescence. A deviation from the area law could manifest as small discrepancies in the inferred Hawking-Page transition or ringdown frequencies [

20,

21].

Generalized Second Law Tests:

Precision tests of the generalized second law in black hole thermodynamics—e.g., via analogue gravity systems or high-accuracy observations of accreting black holes—could reveal hints of entropy deformations [

22,

23].

In summary, the square-root correction offers a minimal but rich extension of semiclassical thermodynamics. It naturally yields stable remnants, is compatible with several quantum gravity paradigms, and may leave subtle observational imprints in astrophysical and cosmological data.

4. Conclusion

We have investigated a phenomenological modification to the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy–area relation, incorporating a square-root correction inspired by quantum gravitational considerations. The deformed entropy,

induces significant changes in black hole thermodynamics. Our analysis shows that this modification leads to a lower Hawking temperature, a less negative specific heat, and a suppressed evaporation rate at small masses.

These results indicate the formation of a stable black hole remnant, which could offer a potential resolution to the black hole information paradox and contribute to the population of dark matter relics, especially in the context of primordial black holes.

While the model is introduced phenomenologically, it captures key features of quantum gravity-inspired corrections and offers a minimal extension of semiclassical thermodynamics. Future work will aim to derive this form of entropy from fundamental principles, explore its effects on charged or rotating black holes, and examine possible observational signatures in gravitational wave physics and cosmology.

References

- J. D. Bekenstein, “Black holes and entropy,” Phys. Rev. D 7, 2333 (1973).

- S. W. Hawking, “Particle creation by black holes,” Commun. Math. Phys. 43, 199 (1975).

- A. Strominger and C. Vafa, “Microscopic origin of the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy,” Phys. Lett. B 379, 99 (1996).

- C. Rovelli, “Black hole entropy from loop quantum gravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3288 (1996).

- R. J. Adler, P. Chen, and D. I. Santiago, “The generalized uncertainty principle and black hole remnants,” Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 33, 2101 (2001).

- F. Scardigli, “Generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity from micro–black hole Gedanken experiment,” Phys. Lett. B 452, 39 (1999).

- P. Nicolini, A. Smailagic, and E. Spallucci, “Noncommutative geometry inspired Schwarzschild black hole,” Phys. Lett. B 632, 547 (2006).

- A. Barrau, J. Grain, and S. O. Alexeyev, “Evaporation of black holes in noncommutative geometry,” Phys. Lett. B 584, 114 (2004).

- P. Chen, Y. C. Ong, and D. Yeom, “Black hole remnants and the information loss paradox,” Phys. Rep. 603, 1–45 (2015).

- B. Carr, F. Kühnel, and M. Sandstad, “Primordial black holes as dark matter,” Phys. Rev. D 94, 083504 (2016).

- A. F. Ali and M. Moussa, “Noncommutative geometry inspired black holes with generalized uncertainty principle,” Phys. Rev. D 100, 066024 (2019).

- T. Qiu and K. Yang, “Modified thermodynamics from deformed entropy-area law and implications for quantum gravity,” Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 878 (2021).

- B. Koch, I. A. Reyes, and Á. Rincón, “A scale-dependent black hole in three-dimensional spacetime,” Class. Quantum Grav. 37, 105014 (2020).

- J. Giné and E. Escofet, “Minimal length corrections to Schwarzschild black hole evaporation,” Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 1235 (2022).

- Y. C. Ong, “Hawking evaporation and black hole remnants in quantum gravity,” J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 93 (2022).

- P. Nicolini, “Noncommutative black holes, the final appeal to quantum gravity: A review,” Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 24, 1229 (2019).

- Y. S. Myung, Y. W. Kim, and Y. J. Park, “Black hole thermodynamics with generalized uncertainty principle,” Phys. Lett. B 645, 393–397 (2007).

- S. Geng and J. Zhou, “Entropy corrections from Gauss–Bonnet gravity,” Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 123 (2020).

- A. M. Green and B. J. Kavanagh, “Primordial black holes as a dark matter candidate,” J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 49, 120501 (2022).

- V. Cardoso and P. Pani, “Testing the nature of dark compact objects: a status report,” Living Rev. Relativ. 22, 4 (2019).

- E. Elizalde, S. Nojiri, and S. D. Odintsov, “Ringdown modes as probes of black hole entropy corrections,” J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 05, 013 (2021).

- P. C. W. Davies and R. B. Mann, “Analog gravity and the generalized second law,” Class. Quant. Grav. 37, 105006 (2020).

- D. Kletter, T. W. Kephart, and R. B. Mann, “Observational tests of black hole entropy deformations,” Phys. Rev. D 105, 064045 (2022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).