Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

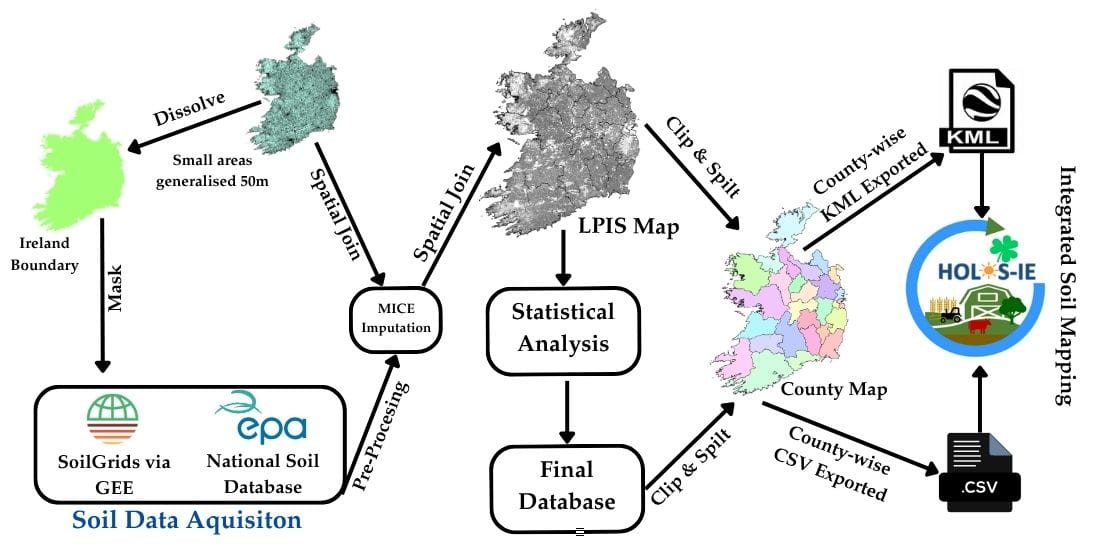

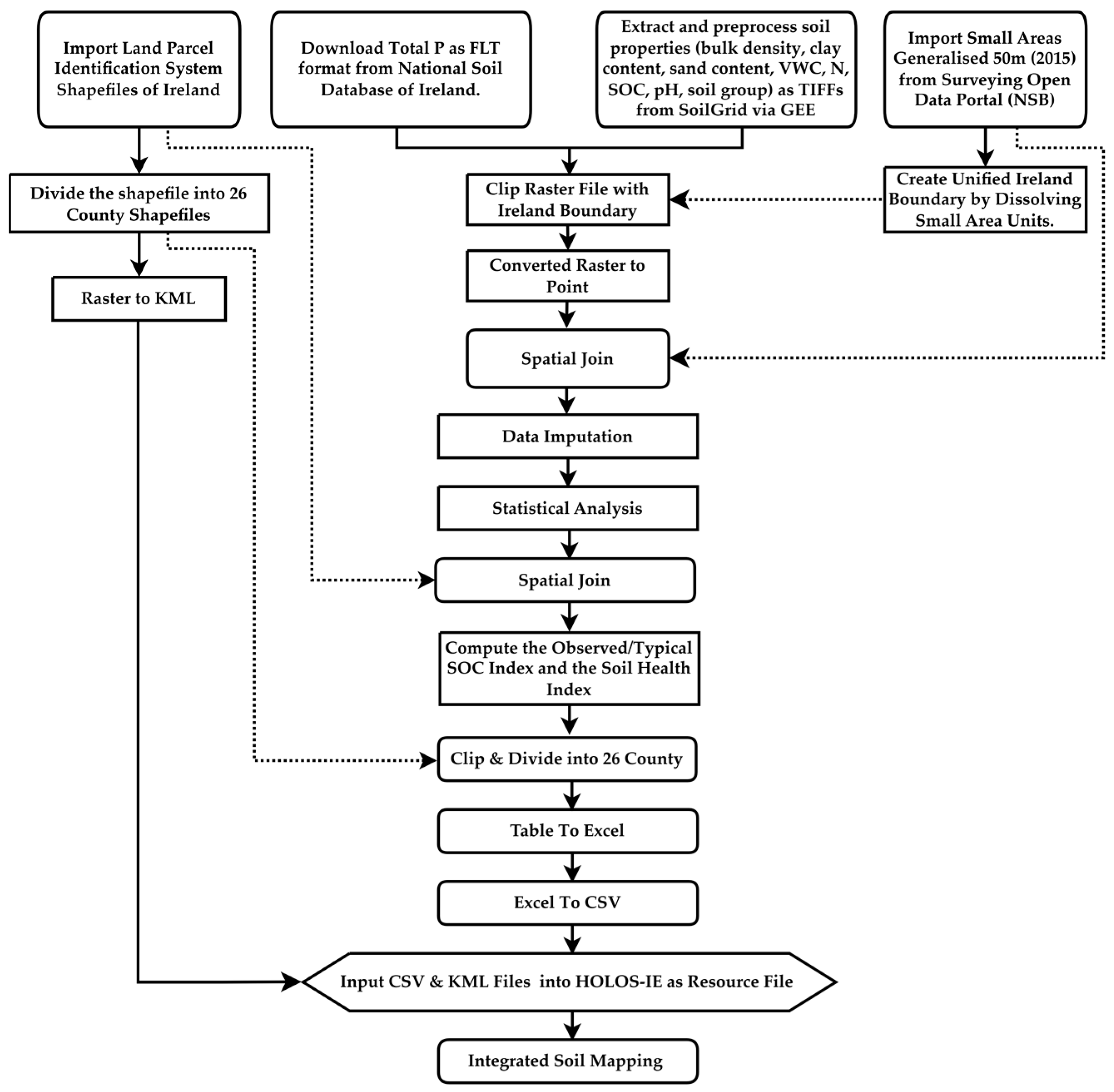

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.2. Data Acquisition and Preparation

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Imputation

2.4. Integration with HOLOS-IE Version 1.0

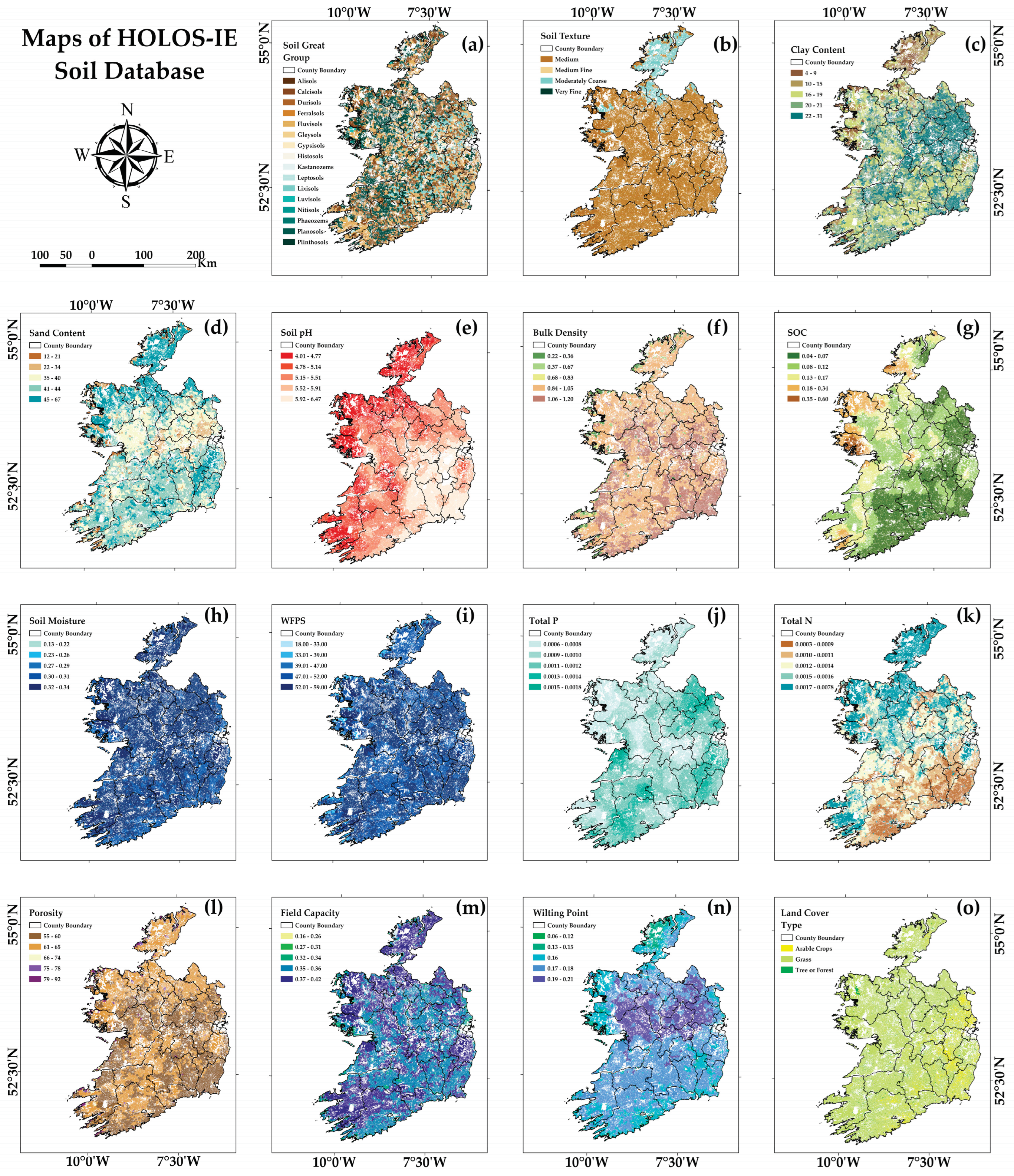

3. Results and Discussion

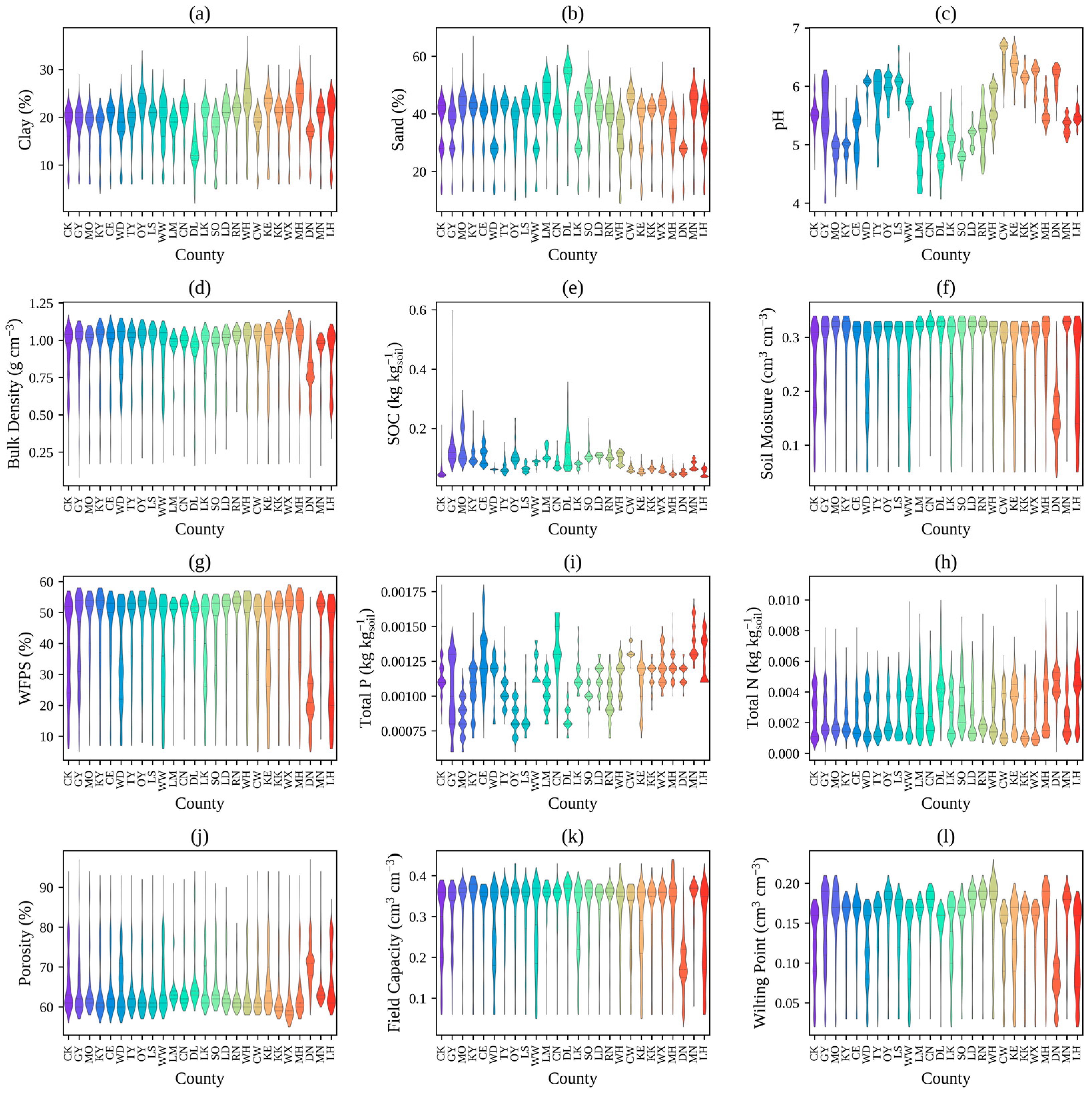

3.1. Summary Statistics

3.2. Soil Property Variation Across Irish Counties

3.3. Soil Health Quality Index

3.4. Integrating Soil Properties with LPIS Map in HOLOS-IE Platform

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CORINE | Coordination of Information on the Environment |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Value |

| DAFM | Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FLT | OpenFlight |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| HOLOS-IE | Towards a Systems-based Digital Platform for Agricultural Land Use Planning, Management Decision, and Inventory Reporting |

| KML | Keyhole Markup Language |

| LPIS | Land Percel Identification System |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| NSB | National Statistical Boundaries |

| NSDB | National Soil Database National Soil Database |

| O/T SOC | Observed/Typical SOC |

| SAFER | Secure Archive for Environmental Research |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| SODP | Surveying Open Data Portal |

| SSURGO | Soil Survey Geographic Database |

| SWAT | Soil and Water Assessment Tool |

| TIFF | Tagged Image File Format |

| Total N | Total Nitrogen |

| Total P | Total phosphorus |

| VWC | Volumetric Water Content |

| WFPS | Water-Filled Pore Space |

Appendix A

References

- Chatzichristou, T. Can Farms Combining Livestock and Crops Improve Sustainability? Available online: https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2024/0326/1440039-mixed-farming-systems-crops-livestock-sustainabilty-rural-development/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Fay, D.; McGrath, D.; Zhang, C.; Carrigg, C.; O’Flaherty, V.; Kramers, G.; Carton, O.T.; Grennan, E.J. National Soils Database, End of Project Report; Teagasc, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, H.; Almeida, D.; Vala, F.; Marcelino, F.; Caetano, M. Land Cover Mapping from Remotely Sensed and Auxiliary Data for Harmonized Official Statistics. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2018, Vol. 7, Page 157 2018, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyssaert, S.; Jammet, M.; Stoy, P.C.; Estel, S.; Pongratz, J.; Ceschia, E.; Churkina, G.; Don, A.; Erb, K.; Ferlicoq, M.; et al. Land Management and Land-Cover Change Have Impacts of Similar Magnitude on Surface Temperature. Nat Clim Chang 2014, 4, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Holden, N.M.; Ward, S.M. Mapping Peatlands in Ireland Using a Rule-Based Methodology and Digital Data. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2007, 71, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, W.J.; Brakensiek, C.L.; Saxton, K.E. Estimation of Soil Water Properties. Trans ASABE 1982, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray R., Weil; Nyle C. Brady The Nature and Properties of, Soils; Fox, D. , Gilfillan, A., Dimmick, L., Eds.; Fifteenth.; Pearson: Columbus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Havlin, J.L.; Tisdale, S.L.; Nelson, W.L.; Beaton, J.D. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers, 8th Edition. Pearson 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration to Mitigate Climate Change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Water Entry into Soil. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics 2003, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map. Available online: https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/pages/how-to-use-the-maps (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Barros, V.R.; Field, C.B.; Dokken, D.J.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Mach, K.J.; Bilir, T.E.; Chatterjee, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Estrada, Y.O.; Genova, R.C.; et al. Climate Change 2014 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part B: Regional Aspects: Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part B: Regional Aspects: Working Group II Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2014; pp. 1–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, M.M.; Alananbeh, K.M.; Othman, Y.A.; Leskovar, D.I. Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.G.; Huggins, D.R.; Reganold, J.P. Linking Soil Health and Ecological Resilience to Achieve Agricultural Sustainability. Front Ecol Environ 2023, 21, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, K. Assessment of Watershed Resources for Sustainable Agricultural Development: A Case of Developing an Operational Methodology Under Indian Conditions Through Geospatial Technologies. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2020, XLII-3-W11, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwart, S.; Black, H.; Cai, Z.; Gicheru, P.; Joosten, H.; Victoria, R.; Milne, E.; Noellemeyer, E.; Pascual, U.; Nziguheba, G.; et al. Benefits of Soil Carbon: Report on the Outcomes of an International Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment Rapid Assessment Workshop. Carbon Manag 2014, 5, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Dong, H.; Elsiddig, E.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; 2014; pp. 811–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B. Development of Soil and Land Cover Databases for Use in the Soil Water Assessment Tool from Irish National Soil Maps and CORINE Land Cover Maps for Ireland. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Osborne, B.A. Improving Estimates of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Stocks and Their Long-Term Temporal Changes in Agricultural Soils in Ireland. Geoderma 2018, 322, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Kiely, G.; O’Brien, P.; Müller, C. Organic Carbon Stocks in Agricultural Soils in Ireland Using Combined Empirical and GIS Approaches. Geoderma 2013, 193–194, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.; Kavvas, M.L.; Ishida, K.; Ercan, A.; Chen, Z.Q.; Anderson, M.L.; Ho, C.; Nguyen, T. Integrating Global Land-Cover and Soil Datasets to Update Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Parameterization in Hydrologic Modeling. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 631–632, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzio, M.; Arnold, J.; Srinivasan, R. Integration of SSURGO Maps and Soil Parameters within a Geographic Information System and Nonpoint Source Pollution Model System. J Soil Water Conserv 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, I.R.; Royston, P.; Wood, A.M. Multiple Imputation Using Chained Equations: Issues and Guidance for Practice. Stat Med 2011, 30, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azur, M.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Frangakis, C.; Leaf, P.J. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What Is It and How Does It Work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2011, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.I.; Collier, R.; Barry, A.; Khalil, M.I. Stakeholder Perspectives on Irish Agri-Environmental Measures and HOLOS-IE Digital Platform Development. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Sen, B.; Siddque, M.; Chatzichristou, T.; McPherson, A.; Rakin, S.; Herron, J.; Kröbel, R.; Osborne, B.; Collier, R. HOLOS-IE: A System Model for Assessing Carbon Emissions and Balance in Agricultural Systems. Copernicus Meetings 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binner, H.; Andrade, L.; McNamara, M.E. Assessing Synergies between Soil Research in the Republic of Ireland and European Union Policies. Environmental Challenges 2024, 15, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markdown/Access_on_gee.Md · Master · ISRIC / SoilGrids / Soilgrids.Notebooks · GitLab Available online:. Available online: https://git.wur.nl/isric/soilgrids/soilgrids.notebooks/-/blob/master/markdown/access_on_gee.md (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Poggio, L.; De Sousa, L.M.; Batjes, N.H.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing Soil Information for the Globe with Quantified Spatial Uncertainty. SOIL 2021, 7, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, M.E.; Poggio, L.; Batjes, N.H.; Armindo, R.A.; de Jong van Lier, Q.; de Sousa, L.; Heuvelink, G.B.M. Global Mapping of Volumetric Water Retention at 100, 330 and 15 000 Cm Suction Using the WoSIS Database. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2023, 11, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, Dr.D.; Zhang, Dr.C. Towards a National Soil Database Available online:. Available online: https://eparesearch.epa.ie/safer/resource?id=c265bb3f-2cec-102a-b1da-b128b41032cc (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Small Areas Generalised 50m - National Statistical Boundaries - 2015 | Surveying Open Data Portal Available online:. Available online: https://data-osi.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/osi::small-areas-generalised-50m-national-statistical-boundaries-2015/about (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Land Parcel Identification System Land Parcel Data - Dataset - PSB Data Catalogue Available online:. Available online: https://datacatalogue.gov.ie/dataset/land-parcel-identification-system-land-parcel-data (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- FAO 6. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/CDrom/FAO_Training/FAO_Training/General/x6706e/x6706e06.htm (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Brogowski, Z.; Kwasowski, W.; Madyniak, R. Calculating Particle Density, Bulk Density, and Total Porosity of Soil Based on Its Texture. Soil Science Annual 2014, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasundara, S. What’s an Easy Way to Measure WFPS of Arable Soil? 2016.

- Bean, E.Z.; Huffaker, R.G.; Migliaccio, K.W. Estimating Field Capacity from Volumetric Soil Water Content Time Series Using Automated Processing Algorithms. Vadose Zone Journal 2018, 17, 180073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, C.J.; Bentley, L.; De Rosa, D.; Panagos, P.; Emmett, B.A.; Thomas, A.; Robinson, D.A. Benchmarking Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) Concentration Provides More Robust Soil Health Assessment than the SOC/Clay Ratio at European Scale. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teagasc Irish Soil Information System. Teagasc Research Soil Special 2014.

- Riaz, M.; Marschner, P. Sandy Soil Amended with Clay Soil: Effect of Clay Soil Properties on Soil Respiration, Microbial Biomass, and Water Extractable Organic C. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2020, 20, 2465–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žurovec, O.; Wall, D.P.; Brennan, F.P.; Krol, D.J.; Forrestal, P.J.; Richards, K.G. Increasing Soil PH Reduces Fertiliser Derived N2O Emissions in Intensively Managed Temperate Grassland. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2021, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagasc Soil PH & Lime; 2016; Vol. 2;

- Brogan, J.; Crowe, M.; Carty, M.G. Towards Setting Environmental Quality Objectives for Soil Developing: A Soil Protection Strategy for Ireland. Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland.

- Schwyter, A.R.; Vaughan, K.L. 5.2: Bulk Density, Porosity, Particle Density of Soil. In Intro to Soil Science Laboratory Manual; University of Wyoming, 2020.

- Eaton, J.M.; McGoff, N.M.; Byrne, K.A.; Leahy, P.; Kiely, G. Land Cover Change and Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in the Republic of Ireland 1851-2000. Clim Change 2008, 91, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, S. Irish Soil Data Analysis 2023-2024 Part 2: Phosphorus; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, M.B. Field Capacity, Wilting Point, Available Water, and the Non-Limiting Water Range. Principles of Soil and Plant Water Relations 2005, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA; NRCS Soil Health – Bulk Density/Moisture/Aeration. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA NRCS), 2019.

- USDA; NRCS Soil Health - Respiration. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA NRCS), 2014.

- Hintze, J.L.; Nelson, R.D. Violin Plots: A Box Plot-Density Trace Synergism. American Statistician 1998, 52, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K. Understanding Soil Texture: Methods and Importance; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kiely, G.; Leahy, P.; Lewis, L.; Xu, X.; Sottocornola, M. SoilC - Feasibility of Grassland Soil Carbon Survey 2017.

- Jarmain, C.; Cummins, T.; Jovani-Sancho, A.J.; Nairn, T.; Premrov, A.; Reidy, B.; Renou-Wilson, F.; Tobin, B.; Walz, K.; Wilson, D.; et al. Soil Organic Carbon Stocks by Soil Group for Afforested Soils in Ireland. Geoderma Regional 2023, 32, e00615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Bampa, F.; Knights, K.; Creamer, R.E. Soil Protection for a Sustainable Future: Options for a Soil Monitoring Network for Ireland. Soil Use Manag 2017, 33, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuohy, P.; Fenton, O.; O’Loughlin, J.; Humphreys, J. Land Drainage - A Farmer’s Practical Guide to Draining Grassland in Ireland. 2013.

- Henry, J.; Aherne, J. Nitrogen Deposition and Exceedance of Critical Loads for Nutrient Nitrogen in Irish Grasslands. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 470–471, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, Karen.; Fealy, R. In Digital Soil Information System for Ireland – Scoping Study; Environmental Protection Agency, 2007.

- Creamer, R.E.; Simo, I.; O’sullivan, L.; Reidy, B.; Schulte, R.P.O.; Fealy, R.M. Irish Soil Information System: Soil Property Maps. In Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, R.W. Soil Carbon Stocks and Changes in the Republic of Ireland. J Environ Manage 2005, 76, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soil Carbon. Environmental information systems 2022.

- Tuohy, P.; O’Sullivan, L.; Fenton, O. Field Scale Estimates of Soil Carbon Stocks on Ten Heavy Textured Farms across Ireland. J Environ Manage 2021, 281, 111903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. A Simple Soil Organic Carbon Level Metric beyond the Organic Carbon-to-Clay Ratio. Soil Use Manag 2023, 39, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, S.; Broll, G.; Flessa, H.; Don, A. Benchmarking Soil Organic Carbon to Support Agricultural Carbon Management: A German Case Study#. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2022, 185, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Deng, L.; Wang, X.; Cui, R.; Liu, G. A Review of Farmland Soil Health Assessment Methods: Current Status and a Novel Approach. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14, 9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröbel, R.; Bolinder, M.A.; Janzen, H.H.; Little, S.M.; Vandenbygaart, A.J.; Kätterer, T. Canadian Farm-Level Soil Carbon Change Assessment by Merging the Greenhouse Gas Model Holos with the Introductory Carbon Balance Model (ICBM). Agric Syst 2016, 143, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Parameter | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay (%) | 18.41 | 4.8574 | 2 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 37 |

| Sand (%) | 35.57 | 9.9011 | 9 | 28 | 39 | 43 | 67 |

| pH | 5.67 | 0.5535 | 4 | 5.26 | 5.74 | 6.16 | 6.86 |

| Bulk Density (g cm-3) | 0.88 | 0.1914 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.2 |

| SOC (kg kgSoil-1) | 0.08 | 0.0458 | 0.035 | 0.049 | 0.063 | 0.092 | 0.598 |

| Soil Moisture (cm3 cm-3) | 0.23 | 0.0859 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| WFPS (%) | 36.50 | 15.4203 | 5 | 23 | 38 | 52 | 59 |

| Total P (kg kgSoil-1) | 0.00 | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0012 | 0.0018 |

| Total N (kg kgsoil-1) | 0.00 | 0.0017 | 0.0001 | 0.0016 | 0.0036 | 0.0046 | 0.011 |

| Porosity (%) | 66.68 | 7.2250 | 55 | 61 | 64 | 71 | 97 |

| Field Capacity (cm3 cm-3) | 0.27 | 0.0990 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.44 |

| Wilting Point (cm3 cm-3) | 0.12 | 0.0503 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).