Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

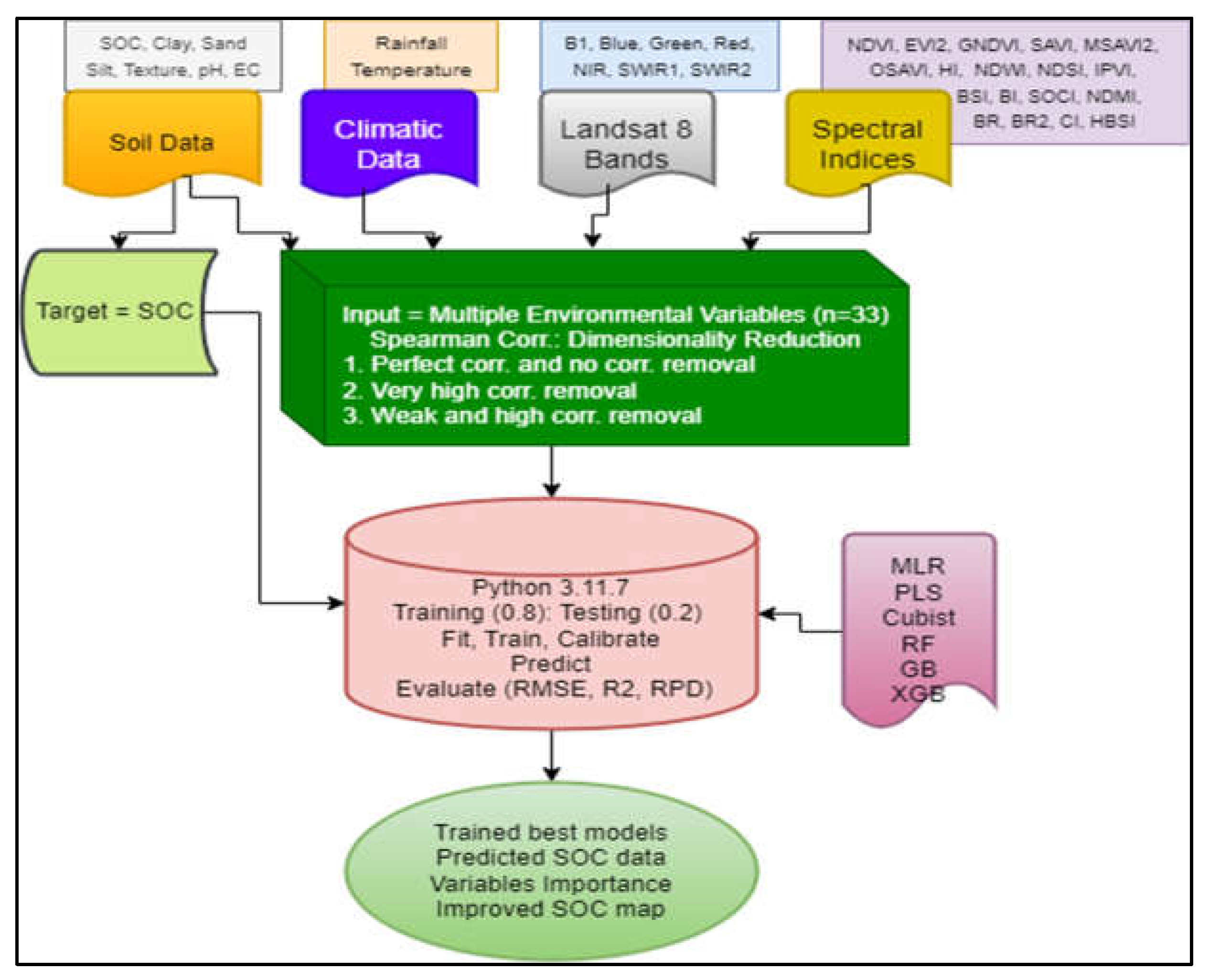

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Soil and Climatic Data

2.3. Landsat 8 and Spectral Indices Data

2.4. Selection of Input Variables

2.5. Models Training, Calibration, Prediction and Evaluation

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Observed Soil Properties

| Parameter | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | *Status | SD | CV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand, % | 2.80 | 85.10 | 43.48 | High | 18.11 | 41.65 |

| Clay, % | 3.50 | 57.30 | 27.27 | Moderate | 13.97 | 51.23 |

| Silt, % | 7.50 | 59.00 | 29.51 | Moderate | 11.61 | 39.36 |

| EC, dS m-1 | 0.01 | 1.92 | 0.19 | Non-saline | 0.28 | 142.03 |

| pH | 6.80 | 9.83 | 8.22 | Moderately alkaline | 0.54 | 6.59 |

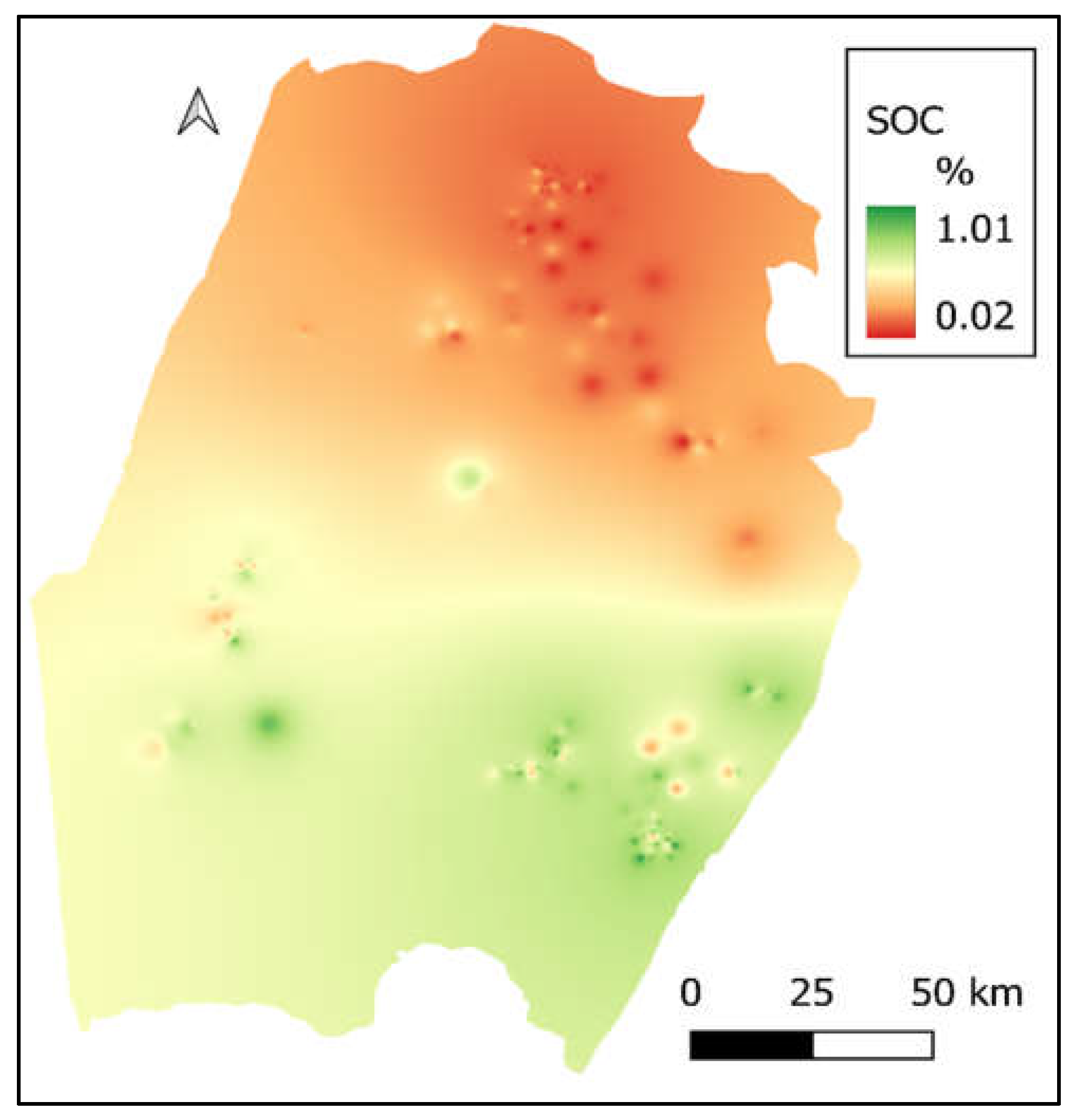

| SOC, % | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.44 | Poor | 0.28 | 62.89 |

3.2. Correlation Analysis, and Variables Dimension Reduction

3.3. SOC Prediction Accuracy of Models

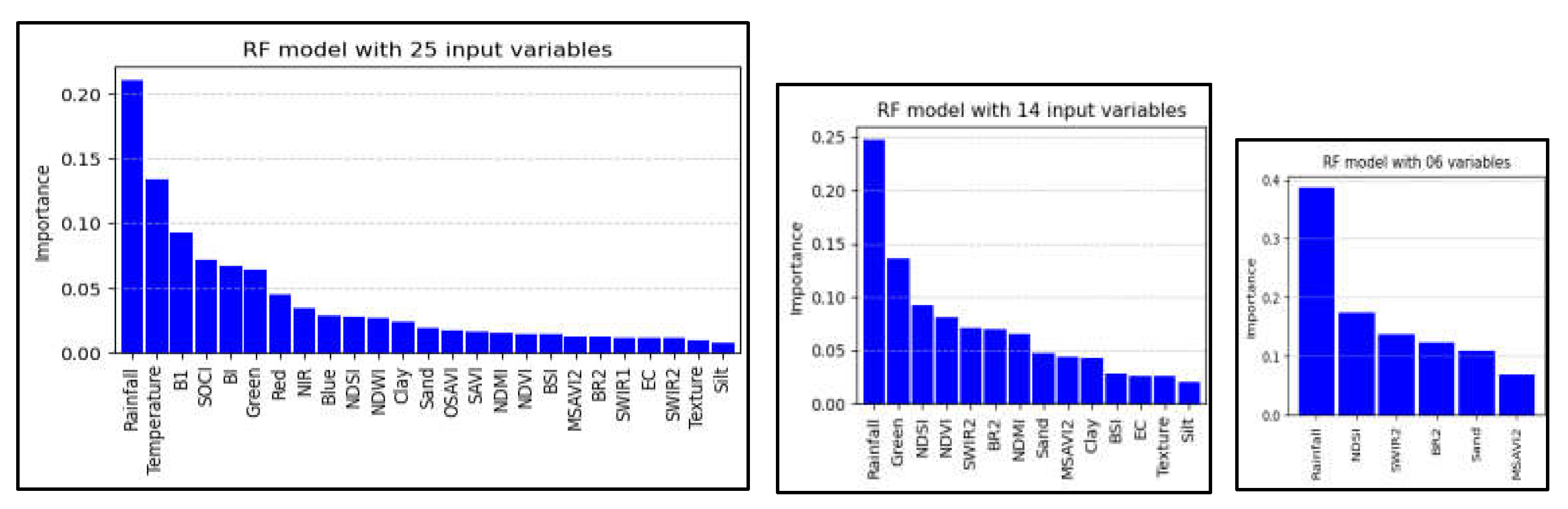

3.4. Importance of Variables

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Soil Organic Carbon: the hidden potential, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy, 2017.

- Page, K.L.; Dang, Y.P.; Dalal, R.C. The ability of conservation agriculture to conserve soil organic carbon and the subsequent impact on soil physical, chemical, and biological properties and yield, Front Sustain Food Syst 2020, 4:31. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.X.; Lal, R.; Smeck, N.E.; Calhoun, F.G. Relationships between soil organic carbon pool and site variables in Ohio. Geoderma 2004a, 121:187-195.

- Pringle, M.J.; Allen, D.E.; Phelps, D.G.; Bray, S.G.; Orton, T.G.; Dalal, R.C. The effect of pasture utilization rate on stocks of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in a semi-arid tropical grassland. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2014, 195:83–90. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.; Voigt, K.; Beusch, C.; Almeida-Cortez, J.S.; Kowarik, I.; Walz, A.; Cierjacks, A. Grazing deteriorates the soil carbon stocks of Caatinga forest ecosystems in Brazil. Forest Ecology Management 2016, 367:62–70. [CrossRef]

- Tolimir, M.; Kresović, B.; Životić, L.; Dragović, S.; Dragović, R.; Sredojević, Z.; Gajić, B. The conversion of forestland into agricultural land without appropriate measures to conserve SOM leads to the degradation of physical and rheological soil properties. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1):13668. [CrossRef]

- Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks–a meta-analysis. Global Change Biology 2011, 17(4):1658–1670. [CrossRef]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12000 years of human land use, P. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114, 9575– 9580. [CrossRef]

- Measho, S.; Chen, B.; Trisurat, Y.; Pellikka, P.; Guo, L. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Vegetation Dynamics as a Response to Climate Variability and Drought Patterns in the Semiarid Region, Eritrea. Remote Sens 2019, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebrezgabher, M.G.; Taibao, Y.; Xuemei, Y.; Congqiang, W. Assessment of desertification in Eritrea : degradation based on Landsat images, J Arid Land 2019, 11(3):319–331. [CrossRef]

- Nuguse, M.T.; Singh, B.; Ogbazghi, W. Studies on soil organic carbon and some physico-chemical properties as affected by different land uses in Eritrea. J. Soil Water Cons 2019, 18(3), 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, T.; Ogbazghi, W.; Singh, B. Effects of soil and water conservation interventions on some physico-chemical properties of soil in Hamelmalo and Serejeka Sub-zones of Eritrea, J. Soil Water Cons 2020, 19(3): 229-234. [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, T.; Mohamed, E.S., Ghebretnsae, T.W.; Ghebremariam, S.B.; Mehrteab, M. Soil organic carbon stock assessment for soil fertility improvement, ecosystem restoration and climate-change mitigation, E3S Web of Conferences 2024, 555 (RIEEM 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, T.; Ogbazghi, W.; Singh, B.; Tsegai, T. Factors Influencing Soil and Water Conservation Adoption in Basheri, Gheshnashm and Shmangus Laelai, Eritrea. IRA International Journal of Applied Sciences 2018, 12(2):7-14. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Hartemink, A.E.; Minasny, B.; Kheir, R.B.; Greve, M.B.; Greve, M.H. Digital mapping of soil organic carbon contents and stocks in Denmark, PLoS ONE 2014, 9(8): e105519. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E. S.; Saleh, A.M.; Belal, A.B.; Gad, A.A. Application of near infrared reflectance for quantitative assessment of soil properties. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences 2018, 21(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Abu-hashim, M.; Nassrallah, A.; Khalil, M.N.; Hendawy, E.; benhasher, F.F.; Shokr, M.S.; Elshewy, M.A.; Mohamed, E.S. Integration of remote sensing and artificial neural networks for prediction of soil organic carbon in arid zones, Front. Environ Sci 2024, 12:1448601. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X. Soil organic carbon estimation using remote sensing data-driven machine learning, PeerJ 2024, 12:e17836. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pre-Investment Study on Forestry and Wildlife Sub-Sector of Eritrea, FAO, Rome, Italy, 1997.

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: new 1 km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas, Int J of Clim 2017, 37 (12), 4302-4315.

- Naty, A. Environment, Society and the State in Western Eritrea. Africa 2002, 72(4). [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.J.; Black, I.A. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Standard operating procedure for soil organic carbon Walkley-Black method (Titration and colorimetric method), Global Soil Laboratory Network GLOSOLAN, 2019. https://www.fao.org/3/ca7471en/ca7471en.pdf.

- Thomas, G.W. Soil pH and Soil Acidity. In Method of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; SSSA Inc.: Madison, WI, USA; ASA Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1996, 475–490.

- Rhoades, J.D. Salinity: Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3; SSSA Book Series No.5, SSSA and ASA; SSSA Inc.: Madison, WI, USA; ASA Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1996, 417–435.

- Lavkulich, L.M. Methods Manual: Pedology Laboratory; University of British Columbia, Department of Soil Science: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1981.

- Sodango, T.H.; Sha, J.; Li, X.; Noszczyk, T.; Shang, J.; Aneseyee, A.B.; Bao, Z. Modelling the Spatial Dynamics of Soil Organic Carbon Using Remotely-Sensed Predictors in Fuzhou City, China, Remote Sens 2021, 13, 1682. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, J.; Song, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, G. Mapping high resolution national soil information grids of China, Sci Bulletin 2022, 67(3): 328–340. [CrossRef]

- Yami, B.; Singh, N.J.; Handique, B.K.; Swami, S. Mapping and monitoring of soil organic carbon using regression analysis of spectral indices. Current Sci 2023, 124(12), 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Zarnaq, M.; Moshiri, F.; Jamshidi, M.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Tehrani, M.M.; Meymand, F.E. Monitoring changes in soil organic carbon using satellite based variables and machine learning algorithms in arid and semi-arid regions, Environ. Earth Sci 2024, 83:582. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tian, J.; Lu, X.; Tian, Q. Temporal and spatial dynamics distribution of organic carbon content of surface soil in coastal wetlands of Yancheng, China from 2000 to 2022 based on Landsat images, Catena 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rouse Jr, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA Special Publication, Greenbelt, MD, USA, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 1974, 351, p. 309.

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOSMODIS, Remote Sens Environ 1996, 58, 289–298.

- Salas, E.A.L.; Kumaran, S.S. Hyperspectral Bare Soil Index (HBSI): Mapping Soil Using an Ensemble of Spectral Indices in Machine Learning Environment, Land 2023, 12, 1375. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Kim, Y.; Didan, K. 2-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band and its application to AVHRR data. In Proceedings of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering, Sep 2007, 6679, 45–53.

- Mokarram, M.; Roshan, G.; Negahban, S. Landform classification using topography position index (case study: salt dome of Korsia-Darab plain, Iran, Model. Earth Syst Environ 2015, 1(4): 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil adjusted vegetation index, Remote Sens Environ 1994, 48(2), 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, M.; Chen, R. RNDSI: a ratio normalized difference soil index for remote sensing of urban/suburban environments. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2015, 39, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalabad, M.; Abkar, A. Forest canopy density monitoring using satellite images. In 20th ISPRS Congress on International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Istanbul, Turkey, 2004, 12–23.

- Mondal, A.; Khare, D.; Kundu, S.; Mondal, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Spatial soil organic carbon (SOC) prediction by regression kriging using remote sensing data. Egypt J Remote Sens Space Sci 2017, 20(1), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakun, R.S.; Wulder, M.A.; Franklin, S.E. Sensitivity of the thematic mapper enhanced wetness difference index to detect mountain pine beetle red-attack damage. Remote Sens Environ 2003, 86, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuin, S.; Navarro, R.; Fernández, P. Fire severity assessment by using NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) derived from LANDSAT TM/ETM images, Int J Remote Sens 2008, 29, 1053–1073.

- Dvorakova, K; Shi, P; Limbourg, Q; van Wesemael, B. Soil Organic Carbon Mapping from Remote Sensing:The Effect of Crop Residues. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1913. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, J.; Bedidi, A.; Cervelle, B.; Pouget, M; Flay, N. Visible spectrometric indices of hematite (Hm) and goethite (Gt) content in lateritic soils: the application of a Thematic Mapper (TM) image for soil-mapping in Brasilia, Brazil. Int. J. Remote Sensing 1997, 18(13), 2835–2852.

- Carmona, JÁS.; Quirós, E.; Mayoral, V.; Charro, C. Assessing the potential of multispectral and thermal UAV imagery from archaeological sites: A case study from the Iron Age hillfort of Villasviejas del Tamuja (Cáceres, Spain), J Archaeol Sci Reports 2020, 31, 102312. [CrossRef]

- Barsi, J.; Lee, K.; Kvaran, G.; Markham, B.; Pedelty, J. The Spectral Response of the Landsat-8 Operational Land Imager, Remote Sens 2014, 6, 10232–10251. [CrossRef]

- Viscarra-Rossel, R.A.; Taylor, H.J.; McBratney, A.B. Multivariate calibration of hyperspectral γ- ray energy spectra for proximal soil sensing. European Journal of Soil Science 2007, 58(1), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estefan, G.; Rolf, S.; John, R. Methods of Soil, Plant, and Water Analysis: A manual for the West Asia and North Africa region. Third Edition. ICARDA (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas), Box 114/5055, Beirut, Lebanon, 2013.

- Hazelton, P.; Murphy, B. Interpreting soil test results-what do all the numbers mean? 2nd edition, CSIRO publishing, 150 Oxford street, Collingwood VIC 3066, Australia, 2007.

- Husein, H.H.; Lucke, B.; Bäumler, R.; Sahwan, W. A Contribution to Soil Fertility Assessment for Arid and Semi-Arid Lands, Soil Syst 2021, 5, 42. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E. Grazing Management, Forage Production and Soil Carbon Dynamics. Resources 2020, 9(4), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Sheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Using machine learning algorithms based on GF-6 and google earth engine to predict and map the spatial distribution of soil organic matter content. Sustainability 2021, 13(24), 14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, T.D.; Nguyen, C.T.; Delfos, J.; Archibald, R.; Dang, K.B.; Hoang, N.B.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H. A novel intelligence approach based active and ensemble learning for agricultural soil organic carbon prediction using multispectral and SAR data fusion, Sci Total Environ 2022, 804. [CrossRef]

- Meliho, M.; Boulmane, M.; Khattabi, A.; Dansou, C.E.; Orlando, C.A.; Mhammdi, N.; Noumonvi, K.D. Spatial prediction of soil organic carbon stock in the Moroccan high atlas using machine learning, Remote Sensing 2023, 15(10), 2494. [CrossRef]

- Hobley, E.; Wilson, B.; Wilkie, A.; Gray, J.; Koen, T. Drivers of Soil Organic Carbon Storage and Vertical Distribution in Eastern Australia. Plant and Soil 2015, 390, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, Y.; Hui, J.; Sivakumar, B.; Meng, X.; Liu, S. Projected soil organic carbon loss in response to climate warming and soil water content in a loess watershed. Carbon Balance Manage 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Xiao, W.; Chen, J.; Hua, L.; Huang, Z. Climate-Sensitive Spatial Variability of Soil Organic Carbon in Multiple Forests, Central China, Global Eco. Cons 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negassa, M.K.; Haile, M.; Feyisa, G.L.; Wogi, L.; Liben, F.M. Soil Organic Carbon Stock Prediction: Fate under 2050 Climate Scenarios, the Case of Eastern Ethiopia, Sustainability 2023, 15, 6495. [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, G.; Plaza, C.; Priori, S.; Giannetta, B.; Zaccone, C. Soil organic matter dynamics and stability: Climate vs. time, Sci. Total Environ 2024, 929. [CrossRef]

- Dvorakova, K; Heiden, U; Pepers, K; Staats, G; van Os, G; van Wesemael, B. Improving soil organic carbon predictions from a Sentinel–2 soil composite by assessing surface conditions and uncertainties. Geoderma 429 (2023) 116128. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, X. Prediction of Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon in Helan Farmland Based on Different Prediction Models, Land 2023, 12(11), 1984. [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variables | Resolution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Clay, Silt, Sand, Texture, pH, EC | Lab measurement | |

| Climatic | Temperature, Rainfall | 1 km | WorldClim 2.1 |

| Spectral indices | NDVI, GNDVI, IPVI, EVI2, SAVI, OSAVI, MSAVI2, NDWI, NDSI, BSI, HBSI, SOCI, NDMI, BR, BR2, CI, HI, BI | 30 m | Computed using their formula |

| L8 bands | B1, Blue, Green, Red, NIR, SWIR1, SWIR2 | 30 m | Landsat sensor |

| Formula/Wavelength | References |

|---|---|

| NDVI = (NIR – Red)/(NIR + Red) | [32] |

| GNDVI = (NIR−Green)/(NIR+Green) | [33,34] |

| EVI2 = 2.5[(NIR – Red)/(NIR + 2.4*Red + 1)] | [35] |

| IPVI = NIR/(NIR + Red) | [29] |

| SAVI = ((NIR – Red)/(NIR + Red + 0.5))*(1+0.5) | [31] |

| OSAVI = (NIR – Red)/(NIR + Red + 0.16 | [36] |

| MSAVI2 = 0.5[2*NIR+1− √ [(2*NIR+1)2 − 8(NIR−Red)]] | [37] |

| NDWI = (Green – NIR)/(Green + NIR) | [29] |

| NDSI = (SWIR1 – Green)/(SWIR1 + Green) | [38] |

| BSI = [(SWIR2 + Red) – (NIR + Blue)]/[(SWIR2 + Red) + (NIR + Blue)] | [39] |

| HBSI = [(SWIR2+Green)−(NIR+Blue)]/[(SWIR2+Green)+(NIR+Blue)] | [34] |

| SOCI = Blue/(Red*Green) | [31,40] |

| NDMI = (NIR-SWIR1)/(NIR+SWIR1) | [41] |

| BR = (NIR-SWIR2)/(NIR+SWIR2) | [42] |

| BR2 = (SWIR1-SWIR2)/(SWIR1+SWIR2) | [43] |

| CI = (Red – Green)/(Red + Green) | [44] |

| HI = (2*Red – Green – Blue)/(Green – Blue) | [44] |

| BI = √ [(Red2 + Green2)/2] | [34,45] |

| Blue 0.450 - 0.510 µm | [27,46] |

| Green 0.530 - 0.590 µm | [27,46] |

| Red 0.640 - 0.670 µm | [27,46] |

| NIR 0.850 - 0.880 µm | [27,46] |

| SWIR1 1.570 - 1.650 µm | [27,46] |

| SWIR2 2.110 - 2.290 µm | [27,46] |

| No. of Variables | Metrics | PLS | Cubist | XGB | GB | MLR | RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | RMSE | 0.128 | 0.131 | 0.129 | 0.129 | 0.143 | 0.141 |

| R2 | 0.776 | 0.778 | 0.775 | 0.784 | 0.737 | 0.743 | |

| RPD | 2.147*** | 2.097*** | 2.141*** | 2.125*** | 1.925** | 1.949** | |

| 14 | RMSE | 0.113 | 0.122 | 0.126 | 0.135 | 0.135 | 0.141 |

| R2 | 0.827 | 0.808 | 0.783 | 0.764 | 0.764 | 0.745 | |

| RPD | 2.439*** | 2.257*** | 2.177*** | 2.034*** | 2.032*** | 1.956** | |

| 06 | RMSE | 0.131 | 0.141 | 0.124 | 0.142 | 0.133 | 0.144 |

| R2 | 0.767 | 0.713 | 0.792 | 0.739 | 0.758 | 0.703 | |

| RPD | 2.104*** | 1.950*** | 2.224*** | 1.933** | 2.062*** | 1.917** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).