Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Field Sampling Procedure and Laboratory Analyses

- For soil organic carbon analysis: Disturbed samples were air-dried, crushed, and passed through a 0.5 mm sieve

- For bulk density determination: Undisturbed samples were oven-dried at 105°C to determine soil bulk density using the following equation (Eq. 1):

- SOCi (Mg C ha-1) is the organic carbon stock of depth increment i; OCi (mg C g-1 fi ne earth) is the organic carbon content of the fine earth fraction (< 2 mm) in the depth increment i;

- BD fne2i (g fine earth cm-3 soil) is the mass of ne earth per total volume of the soil sample = mass (g) of fine earth / total volume of soil sample (cm3 ) in the depth increment i;

- ti is the thickness (depth, in cm) of the depth increment i;

- is a factor for converting mg C cm-2 to Mg C ha-1

2.3. Remote Sensing Image Acquisition and Processing

2.4. Terrain, Soil and Climatic Variables.

2.5. ML Approaches and Description of the Models

2.6. Model Development and Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Land Use Land Cover (LULC) Analysis

3.2. Soil Bulk Density and Organic Carbon

3.3. Correlation Between Remote Sensing-Derived and Environmental Variables with SOC

3.4. RapidEye and Sentinel-2-Based SOC Prediction

3.5. Variable Importance Ranking for SOC

3.6. SOC Computed per Land Use Class/Types from the RapidEye and Sentinel-2 Data

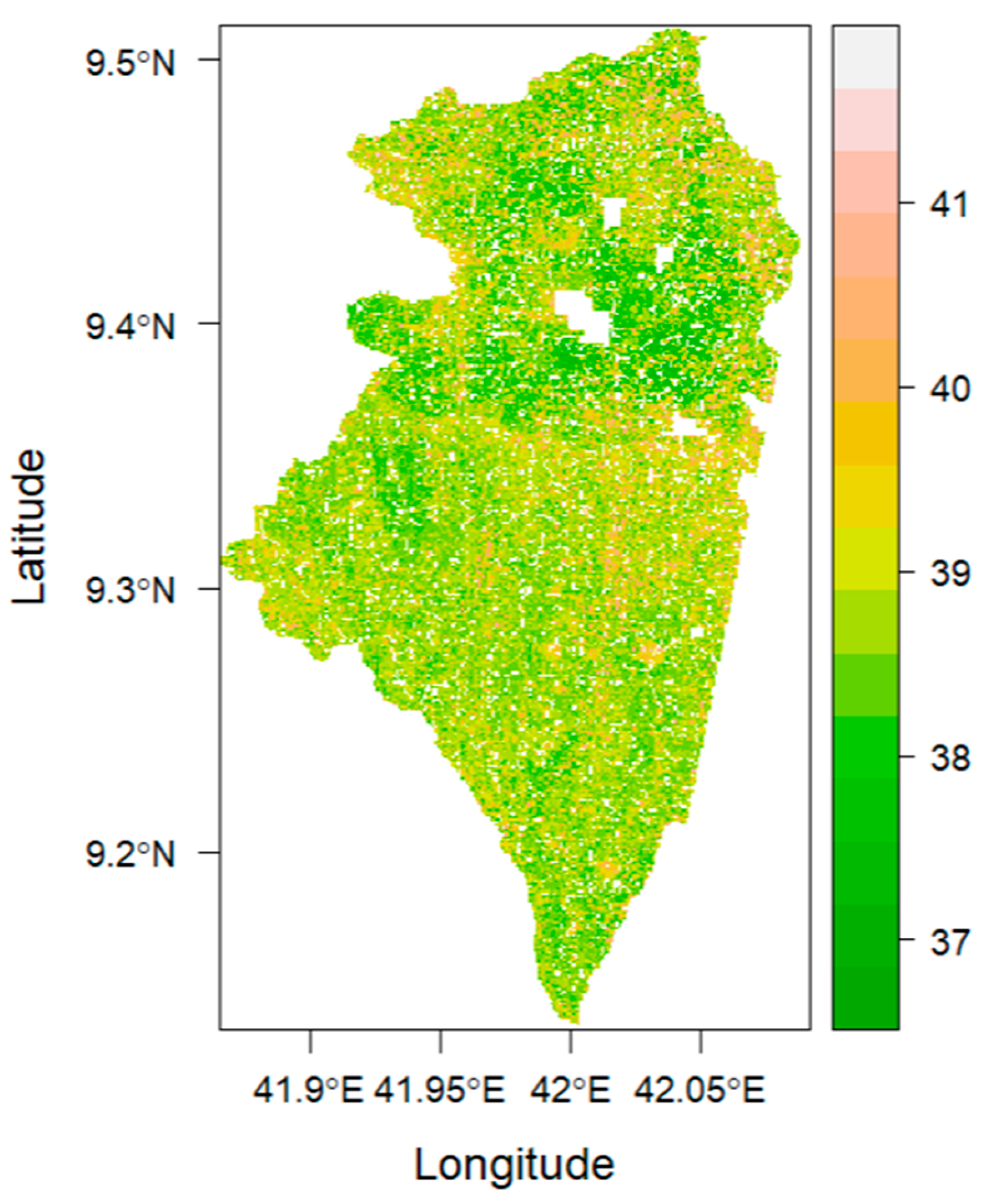

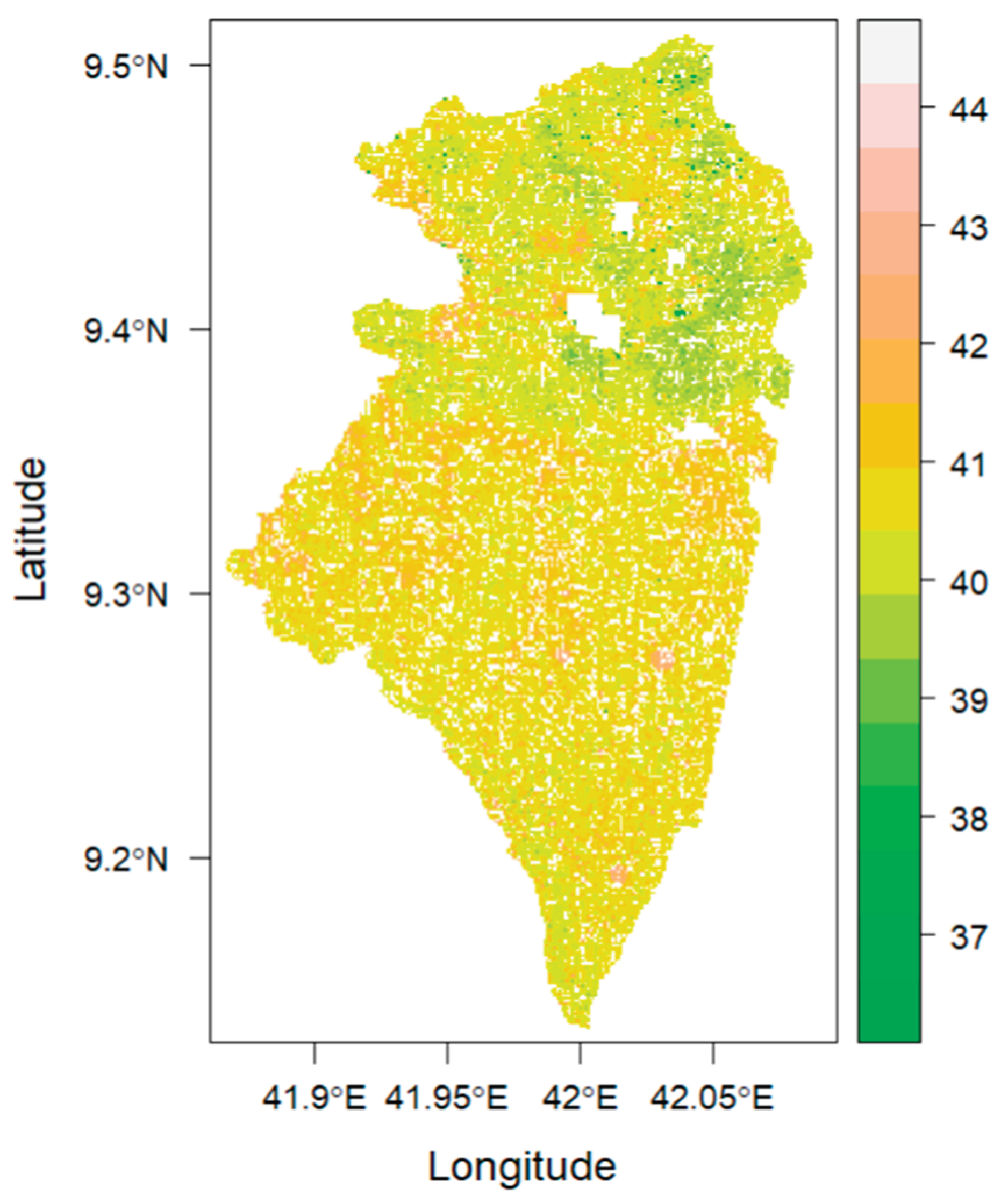

3.7. Spatial Variability Mapping of the SOC from RapidEye and Sentinel-2 Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Minasny, B. , et al., Soil carbon 4 per mille. Geoderma, 2017. 292: p. 59-86. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. , Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. science, 2004. 304(5677): p. 1623-1627. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.L. , Environmental soil chemistry: An overview. Environmental soil chemistry, 1995: p. 1-22.

- Smith, P. , Land use change and soil organic carbon dynamics. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2008. 81(2): p. 169-178. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A. , et al., Detection of carbon stock change in agricultural soils using spectroscopic techniques. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2006. 70(3): p. 844-850. [CrossRef]

- Berhongaray, G. , et al., Land use effects on soil carbon in the Argentine Pampas. Geoderma, 2013. 192: p. 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Ashagrie, Y. , et al., Soil aggregation, and total and particulate organic matter following conversion of native forests to continuous cultivation in Ethiopia. Soil and Tillage Research, 2007. 94(1): p. 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Tofu, D.A. and K. Wolka, Climate change induced a progressive shift of livelihood from cereal towards Khat (Chata edulis) production in eastern Ethiopia. Heliyon, 2023. 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Feyisa, T.H. and J.B. Aune, Khat expansion in the Ethiopian highlands. Mountain Research and Development, 2003. 23(2): p. 185-189.

- Mellisse, B.T., M. Tolera, and A. Derese, Traditional homegardens change to perennial monocropping of khat (Catha edulis) reduced woody species and enset conservation and climate change mitigation potentials of the Wondo Genet landscape of southern Ethiopia. Heliyon, 2024. 10(1): p. e23631. [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, S. , et al., Climate and soil properties limit the positive effects of land use reversion on carbon storage in Eastern Australia. Scientific Reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 17866. [CrossRef]

- Gabarron-Galeote, M.A., S. Trigalet, and B. van Wesemael, Effect of land abandonment on soil organic carbon fractions along a Mediterranean precipitation gradient. Geoderma, 2015. 249: p. 69-78. [CrossRef]

- Abera, W. , et al., Estimating spatially distributed SOC sequestration potentials of sustainable land management practices in Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental Management, 2021. 286: p. 112191. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.B. and R.M. Gifford, Soil carbon stocks and land use change: a meta analysis. Global change biology, 2002. 8(4): p. 345-360. [CrossRef]

- Padarian, J., B. Minasny, and A.B. McBratney, Using deep learning for digital soil mapping. Soil, 2019. 5(1): p. 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Amare, T. , et al., Prediction of soil organic carbon for Ethiopian highlands using soil spectroscopy. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013. 2013(1): p. 720589. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeus, H. , et al., Spectral reflectance based indices for soil organic carbon quantification. Geoderma, 2008. 145(1-2): p. 28-36.

- Grunwald, S. , Multi-criteria characterization of recent digital soil mapping and modeling approaches. Geoderma, 2009. 152(3-4): p. 195-207. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, V. , et al., The use of remote sensing in soil and terrain mapping—A review. Geoderma, 2011. 162(1-2): p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, A. and C. Hergarten, Visible near infra-red (VisNIR) spectroscopy for predicting soil organic carbon in Ethiopia. Soil-Based Ecological Services and Potentials for Sequestering Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) in Ethiopia, 2014: p. 94.

- Bhunia, G.S., P. Kumar Shit, and H.R. Pourghasemi, Soil organic carbon mapping using remote sensing techniques and multivariate regression model. Geocarto International, 2019. 34(2): p. 215-226. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, F. , et al., Soil organic carbon mapping using LUCAS topsoil database and Sentinel-2 data: An approach to reduce soil moisture and crop residue effects. Remote Sensing, 2019. 11(18): p. 2121. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, F. , et al., Evaluation of the potential of the current and forthcoming multispectral and hyperspectral imagers to estimate soil texture and organic carbon. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016. 179: p. 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Francos, N. , et al., Mapping soil organic carbon stock using hyperspectral remote sensing: A case study in the sele river plain in southern italy. Remote Sensing, 2024. 16(5): p. 897. [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A. , et al., Soil organic carbon and texture retrieving and mapping using proximal, airborne and Sentinel-2 spectral imaging. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2018. 218: p. 89-103. [CrossRef]

- van Wesemael, B. , et al., Remote sensing for soil organic carbon mapping and monitoring. 2023, MDPI. p. 3464.

- Minasny, B. , et al., Soil carbon 4 per mille. Geoderma, 2017. 292: p. 59-86. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. , et al., The estimation of soil organic matter variation in arid and semi-arid lands using remote sensing data. International Journal of Geosciences, 2019. 10(05): p. 576.

- da Silva Junior, E.C. , et al., Mapping soil organic carbon stock through remote sensing tools for monitoring iron minelands under rehabilitation in the Amazon. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2024. 26(11): p. 27685-27704.

- Kumar, P. , et al., Estimation of accumulated soil organic carbon stock in tropical forest using geospatial strategy. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 2016. 19(1): p. 109-123.

- Madugundu, R. , et al., Estimation of soil organic carbon in agricultural fields: A remote sensing approach. Journal of Environmental Biology, 2022. 43(1): p. 73-84.

- Yapa, L.K., N. M. Piyasena, and H.K. Herath, Applicability of Multispectral Images to Detect Soil Organic Carbon Content in Land Suitability Assessment: A Case of a Sugarcane Plantation. Asian Soil Research Journal, 2023. 7(3): p. 20-29.

- Ben-Dor, E. , et al., Using imaging spectroscopy to study soil properties. Remote sensing of environment, 2009. 113: p. S38-S55.

- Wadoux, A.M.-C., B. Minasny, and A.B. McBratney, Machine learning for digital soil mapping: Applications, challenges and suggested solutions. Earth-Science Reviews, 2020. 210: p. 103359.

- Jo, Y. , et al., Soil organic carbon (SOC) prediction using super learner algorithm based on the remote sensing variables. Environmental Challenges, 2025. 19.

- Mahmood, S. , et al., A High-resolution Soil Organic Carbon Map for Great Britain. Sustainable Environment, 2024. 10(1): p. 2415166.

- Abbaszad, P. , et al., Evaluation of Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 vegetation indices to predict soil organic carbon using machine learning models. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 2023. 10(2): p. 2581-2592.

- Kibret, K. , Characterization of agricultural soils in CASCAPE intervention woredas in eastern region. Final Report. Haramaya University, 2014.

- Powers, J.S. , et al., Geographic bias of field observations of soil carbon stocks with tropical land-use changes precludes spatial extrapolation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011. 108(15): p. 6318-6322.

- Walkley, A. and I.A. Black, An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil science, 1934. 37(1): p. 29-38.

- Millard, P. , et al., Measuring and modelling soil carbon stocks and stock changes in livestock production systems: guidelines for assessment; Version 1-Advanced copy. 2019.

- Tyc, G. , et al., The RapidEye mission design. Acta Astronautica, 2005. 56(1-2): p. 213-219. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. , et al., Estimating soil organic carbon stocks using different modelling techniques in the semi-arid rangelands of eastern Australia. Ecological indicators, 2018. 88: p. 425-438. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A., Y. J. Kaufman, and M.N. Merzlyak, Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sensing of Environment, 1996. 58(3): p. 289-298. [CrossRef]

- Rikimaru, A., P. S. Roy, and S. Miyatake, Tropical forest cover density mapping. Tropical ecology, 2002. 43(1): p. 39-47.

- Hardisky, M., V. Klemas, and M. Smart, The influence of soil salinity, growth form, and leaf moisture on the spectral radiance of. Spartina alterniflora, 1983. 49: p. 77-83.

- Huete, A.R. , A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment, 1988. 25(3): p. 295-309. [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. , The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 1996. 17(7): p. 1425-1432. [CrossRef]

- Florinsky, I.V., T. Skrypitsyna, and O. Luschikova, Comparative accuracy of the AW3D30 DSM, ASTER GDEM, and SRTM1 DEM: A case study on the Zaoksky testing ground, Central European Russia. Remote Sensing Letters, 2018. 9(7): p. 706-714. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Y. Wang, and X. Zhu, Soil organic carbon estimation using remote sensing data-driven machine learning. PeerJ, 2024. 12: p. e17836.

- Beisekenov, N. , et al., Remote sensing-based soil organic carbon monitoring using advanced machine learning techniques under conservation agriculture systems. Smart Agricultural Technology, 2025. 11. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, F.R.A. , et al., Multi-property digital soil mapping at 30-m spatial resolution down to 1 m using extreme gradient boosting tree model and environmental covariates. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 2024. 33: p. 101123.

- Liaw, A. and M. Wiener, Classification and regression by randomForest. R news, 2002. 2(3): p. 18-22.

- Svetnik, V. , et al., Random forest: a classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. Journal of chemical information and computer sciences, 2003. 43(6): p. 1947-1958.

- Breiman, L. , Random forests. Machine learning, 2001. 45: p. 5-32.

- Grinand, C. , et al., Extrapolating regional soil landscapes from an existing soil map: Sampling intensity, validation procedures, and integration of spatial context. Geoderma, 2008. 143(1-2): p. 180-190.

- Fan, J. , et al., Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Extreme Gradient Boosting for predicting daily global solar radiation using temperature and precipitation in humid subtropical climates: A case study in China. Energy conversion and management, 2018. 164: p. 102-111. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. , Stochastic gradient boosting. Computational statistics & data analysis, 2002. 38(4): p. 367-378.

- Hengl, T. , et al., SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS one, 2017. 12(2): p. e0169748.

- Meier, M. , et al., Digital soil mapping using machine learning algorithms in a tropical mountainous area. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 2018. 42: p. e0170421. [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T. , et al., Mapping soil properties of Africa at 250 m resolution: Random forests significantly improve current predictions. PloS one, 2015. 10(6): p. e0125814.

- Jaber, S.M. C.L. Lant, and M.I. Al-Qinna, Estimating spatial variations in soil organic carbon using satellite hyperspectral data and map algebra. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2011. 32(18): p. 5077-5103. [CrossRef]

- Malone, B.P. , et al., Digital Soil Mapping. 2017: Springer.

- Tikuye, B.G. and R.L. Ray, Soil organic carbon retrieval using a machine learning approach from satellite and environmental covariates in the Lower Brazos River Watershed, Texas, USA. Applied Computing and Geosciences, 2025. 26. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszad, P. , et al., Evaluation of Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 vegetation indices to predict soil organic carbon using machine learning models. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 2024. 10(2): p. 2581-2592.

- Cutting, B.J. , et al., Remote Quantification of Soil Organic Carbon: Role of Topography in the Intra-Field Distribution. Remote Sensing, 2024. 16(9): p. 1510.

- Nabiollahi, K. , et al., Assessing soil organic carbon stocks under land-use change scenarios using random forest models. Carbon Management, 2019. 10(1): p. 63-77.

- Kalambukattu, J.G. , et al., Digital mapping of soil organic carbon in the hilly and mountainous landscape of Indian Himalayan region employing machine-learning techniques. Discover Soil, 2025. 2(1).

- Tajik, S., S. Ayoubi, and M. Zeraatpisheh, Digital mapping of soil organic carbon using ensemble learning model in Mollisols of Hyrcanian forests, northern Iran. Geoderma Regional, 2020. 20.

- Budak, M. , et al., Improvement of spatial estimation for soil organic carbon stocks in Yuksekova plain using Sentinel 2 imagery and gradient descent–boosted regression tree. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023. 30(18): p. 53253-53274.

- Gebere, S.B. , et al., Land Use and Land Cover Change Impact on Groundwater Recharge: The Case of Lake Haramaya Watershed, Ethiopia, in Landscape Dynamics, Soils and Hydrological Processes in Varied Climates, A.M. Melesse and W. Abtew, Editors. 2016, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 93-110.

- Wondafrash Ademe, B. , et al., Khat Production and Consumption; Its Implication on Land Area Used for Crop Production and Crop Variety Production among Rural Household of Ethiopia. Journal of Food Security, 2017. 5(4): p. 148-154. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, M. , et al., From self-subsistence farm production to khat: driving forces of change in Ethiopian agroforestry homegardens. Environmental Conservation, 2016. 43(3): p. 263-272. [CrossRef]

- Negash, M., J. Kaseva, and H. Kahiluoto, Perennial monocropping of khat decreased soil carbon and nitrogen relative to multistrata agroforestry and natural forest in southeastern Ethiopia. Regional Environmental Change, 2022. 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, U. , et al., in Haramaya District of East Hararghe Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 2018. 8.

- Mohammed, U., K. K.P.M. Mohammed, and A. Diriba, in Haramaya District of East Hararghe Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. 2018.

- Girmay, G. and B. Singh, Changes in soil organic carbon stocks and soil quality: land-use system effects in northern Ethiopia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B-Soil & Plant Science, 2012. 62(6): p. 519-530. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, E. , et al., Digital mapping of soil organic carbon stocks in the forest lands of Dominican Republic. European Journal of Remote Sensing, 2022. 55(1): p. 213-231. [CrossRef]

- Pouladi, N. , et al., Digital mapping of soil organic carbon using remote sensing data: A systematic review. Catena, 2023. 232. [CrossRef]

- Zeraatpisheh, M. , et al., Digital mapping of soil properties using multiple machine learning in a semi-arid region, central Iran. Geoderma, 2019. 338: p. 445-452. [CrossRef]

- Dahhani, S., M. Raji, and Y. Bouslihim, Synergistic Use of Multi-Temporal Radar and Optical Remote Sensing for Soil Organic Carbon Prediction. Remote Sensing, 2024. 16(11): p. 1871. [CrossRef]

- Were, K. , et al., A comparative assessment of support vector regression, artificial neural networks, and random forests for predicting and mapping soil organic carbon stocks across an Afromontane landscape. Ecological Indicators, 2015. 52: p. 394-403. [CrossRef]

- Keskin, H., S. Grunwald, and W.G. Harris, Digital mapping of soil carbon fractions with machine learning. Geoderma, 2019. 339: p. 40-58. [CrossRef]

| Indices | Description and Equation | References |

|---|---|---|

| MSAVI | Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index 2NIR+1−sqr((2NIR+1)2−8(NIR−RED))/2 |

[43] |

| GNDVI | Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index GNDVI=NIR-Green/NIR+Green, |

[44] |

| BSI | Bare Soil Index BSI=(Red+SWIR)-(NIR+Blue)/(Red+SWIR)+(NIR+Blue) |

[45] |

| NDMI | Normalized Difference Moisture Index NDMI=NIR+SWIR/NIR−SWIR |

[46] |

| SAVI | Soil Adguested Vegetaion Index SAVI= (NIR-R)/(NIR+R+L) ×(1+L), where L=0.5 |

[47] |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index NDWI = (Green – NIR)/(Green + NIR) |

[48] |

| TVI | Transformed Vegetaion Index TVI = Sqrt (NIR-Red/NIR+Red)+0.5 |

[35] |

| Sources | Typical Resolution (resampled to 5- and 10m) | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| MODIS | 500m(fAPAR),1km(LST) | fAPAR, LST |

| ASTER GDEM | 30m | Elevation, Slope, TWI |

| ISRIC SoilGrids | 250m | Sand, Clay, CEC |

| Field | 5 and 10m | Bulk Density (Interpolation) |

| CHIRPS | 0.05° (~5 km) | Rainfall |

| RapidEye | 5m | MSAVI, GNDVI, NDMI, BSI, SAVI, TVI, NDWI |

| Sentinel-2 | 10m | MSAVI, GNDVI, NDMI, BSI, SAVI, TVI, NDWI |

| LULC Types | Area in ha | Area in % |

| Agriculture | 15141.72 | 26.81% |

| Khat-cultivation | 15068.65 | 26.68% |

| Forest | 8004.95 | 14.18% |

| Bare-Grass-Shrub | 15510.27 | 27.47% |

| Other | 2744.61 | 4.86% |

| Total | 56470.2 | 100% |

| Parameters | n | min | max | std.e | stdv | variance | Mean |

| BD | 88 | 0.978 | 1.77 | 0.018 | 0.167 | 0.028 | 1.356 |

| OC | 88 | 0.883 | 3.9 | 0.046 | 0.430 | 0.185 | 1.388 |

| RapidEye | Sentinel-2 | |||||||||||

| LULC | min | max | range | mean | std | min | max | range | mean | std | ||

| Agriculture | 36.7 | 41.9 | 5.2 | 38.6 | 0.6 | 36.3 | 44.2 | 7.9 | 40.6 | 0.5 | ||

| Khat-cultivation | 36.4 | 41.9 | 5.5 | 38.7 | 0.7 | 36.3 | 43.8 | 7.4 | 40.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Forest | 36.5 | 42.0 | 5.5 | 38.9 | 0.8 | 36.0 | 43.8 | 7.8 | 40.4 | 0.6 | ||

| Bare-Grass-Shrub | 36.6 | 41.7 | 5.1 | 38.7 | 0.5 | 36.5 | 44.8 | 8.2 | 40.7 | 0.5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).