Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| As | Arsenic |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| Fe | Iron |

| Hg | Mercury |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Pb | Lead |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM10 | Particles with a diameter less than 10 |

| PM2.5 | Particles with a diameter less than 2.5 |

| V | Vanadium |

| XRF | X-ray Fluorescence |

| Zn | Zinc |

Appendix A Estimated concentrations of metals by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry in PM2.5 and PM10, including all metals at all sampling sites, regardless of whether values were left-censored (e.g., below the calibrated detection limits) or below the instrument’s detection limit.

| Site ID | Name | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Fe | Hg | Mn | Ni | Pb | V | Zn | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Prados School | 2.8 | 5.4 | 4.4 | 19.0 | 12.8 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 19.7 | 18.48 | -69.96 | |

| 2 | San Judas Tadeo School | 2.4 | 2.5 | 10.2 | 23.2 | 10.5 | 6.5 | 23.8 | 21.6 | 18.48 | -69.93 | |||

| 3 | UASD Faculty Club | 2.0 | 3.5 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 18.9 | 18.46 | -69.90 | ||

| 4 | Faculty of Health Sciences, UASD | 3.5 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 18.46 | -69.91 | ||

| 5 | University Geographic Institute, UASD | 3.2 | 2.8 | 20.7 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 9.9 | 18.8 | 19.0 | 18.47 | -69.88 | |

| 6 | Padre Valentín Salinero School | 2.4 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 23.2 | 17.6 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 20.9 | 18.46 | -69.94 | |||

| 7 | Padre Eulalio Antonio Arias Inoa School | 2.9 | 3.9 | 19.2 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 19.8 | 18.51 | -69.92 | ||||

| 8 | José Bordas Valdez School | 2.9 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 23.0 | 22.1 | 5.2 | 18.3 | 20.2 | 18.50 | -69.99 | |||

| 9 | Rosa Duarte School | 4.9 | 3.5 | 24.5 | 28.0 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 19.2 | 18.44 | -69.95 | |||

| 10 | Francisco Xavier Billini School | 2.8 | 23.9 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 20.4 | 18.44 | -69.96 | ||||||

| 11 | National Botanical Garden | 3.3 | 3.5 | 23.4 | 13.8 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 21.1 | 18.49 | -69.95 | ||||

| 12 | Escuela Básica Prof. María del Carmen Pérez Méndez | 2.5 | 20.1 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.53 | -69.97 | |||||

| 13 | Notre Dame School | 4.0 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 19.2 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 36.9 | 19.5 | 18.48 | -69.94 | ||

| 14 | Movearte Professional School | 2.1 | 4.9 | 7.3 | 20.4 | 11.0 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 12.1 | 17.9 | 18.43 | -69.98 | ||

| 15 | República Dominicana School | 3.1 | 20.9 | 14.6 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 24.0 | 19.2 | 18.49 | -69.91 | ||||

| 16 | Víctor Estrella Liz School | 3.2 | 2.4 | 25.6 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 12.2 | 22.3 | 19.5 | 18.49 | -69.93 | ||

| 17 | Association of Authorized Master Builders | 4.4 | 23.1 | 15.0 | 7.6 | 9.5 | 27.0 | 22.0 | 18.49 | -69.89 | ||||

| 18 | María Auxiliadora School | 5.0 | 3.9 | 21.8 | 10.8 | 7.6 | 10.6 | 19.6 | 18.50 | -69.89 | ||||

| 19 | Nuestra Señora del Carmen School | 2.6 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 21.8 | 13.3 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 19.5 | 18.51 | -69.90 | ||

| 20 | Salomé Ureña School | 2.6 | 10.0 | 5.4 | 22.5 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 7.1 | 22.6 | 19.6 | 18.50 | -69.90 | |

| 21 | American School of Santo Domingo | 3.1 | 23.8 | 11.2 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 20.5 | 18.51 | -69.94 | |||||

| 22 | The Community For Learning | 2.7 | 3.7 | 26.2 | 12.3 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 20.7 | 18.51 | -69.97 | ||||

| 23 | APEC University | 2.3 | 6.3 | 21.1 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 30.6 | 20.5 | 18.47 | -69.91 | ||||

| 24 | Prof. Adolfo González School | 2.4 | 6.9 | 21.2 | 8.8 | 2.7 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 19.8 | 18.54 | -69.98 | |||

| 25 | Capotillo School | 7.9 | 19.5 | 13.0 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 19.8 | 18.50 | -69.90 | |||||

| 26 | Aida Cartagena Portalatín School | 3.7 | 3.8 | 19.6 | 14.3 | 7.8 | 11.4 | 19.2 | 18.51 | -69.92 | ||||

| 27 | Arroyo Hondo School | 4.1 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 19.9 | 16.2 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 11.9 | 21.2 | 18.49 | -69.94 | ||

| 28 | Governorship of Mirador Sur Park | 2.4 | 6.6 | 22.3 | 13.9 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 10.0 | 20.7 | 20.3 | 18.44 | -69.96 | ||

| 29 | Agrarian Institute of Dominican Republic | 3.7 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 6.4 | 12.2 | 19.3 | 18.45 | -69.97 | |||||

| 30 | Private residence | 2.8 | 3.5 | 19.1 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.46 | -69.96 |

| Site ID | Name | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Fe | Hg | Mn | Ni | Pb | V | Zn | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Prados School | 4.3 | 20.6 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 7.1 | 8.4 | 18.2 | 18.48 | -69.96 | ||||

| 2 | San Judas Tadeo School | 3.2 | 3.5 | 15.5 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 19.9 | 18.48 | -69.93 | |||

| 3 | UASD Faculty Club | 6.7 | 2.8 | 16.5 | 21.4 | 4.1 | 6.7 | 20.3 | 21.1 | 18.46 | -69.90 | |||

| 4 | Faculty of Health Sciences, UASD | 3.5 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 22.2 | 26.7 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 18.46 | -69.91 | ||

| 5 | University Geographic Institute, UASD | 4.6 | 2.4 | 21.2 | 10.0 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 22.6 | 20.3 | 18.47 | -69.88 | |||

| 6 | Padre Valentín Salinero School | 3.3 | 3.7 | 23.1 | 13.8 | 7.6 | 12.9 | 19.8 | 18.46 | -69.94 | ||||

| 7 | Padre Eulalio Antonio Arias Inoa School | 2.8 | 2.3 | 19.6 | 12.6 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 2.8 | 20.3 | 18.51 | -69.92 | |||

| 8 | José Bordas Valdez School | 3.2 | 7.1 | 22.1 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 21.1 | 18.50 | -69.99 | |||||

| 9 | Rosa Duarte School | 6.9 | 6.8 | 18.4 | 9.5 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 20.6 | 18.44 | -69.95 | |||

| 10 | Francisco Xavier Billini School | 2.2 | 4.7 | 21.9 | 12.8 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 21.0 | 18.44 | -69.96 | |||

| 11 | National Botanical Garden | 5.3 | 24.3 | 10.2 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 20.4 | 18.49 | -69.95 | |||

| 12 | Escuela Básica Prof. María del Carmen Pérez Méndez | 2.6 | 21.4 | 8.8 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 20.1 | 18.53 | -69.97 | ||||

| 13 | Notre Dame School | 2.8 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 19.3 | 12.7 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 6.9 | 20.0 | 18.48 | -69.94 | ||

| 14 | Movearte Professional School | 2.9 | 3.5 | 19.2 | 4.1 | 7.5 | 2.2 | 13.9 | 19.6 | 18.43 | -69.98 | |||

| 15 | República Dominicana School | 19.6 | 11.4 | 6.1 | 19.8 | 18.49 | -69.91 | |||||||

| 16 | Víctor Estrella Liz School | 2.6 | 8.9 | 2.1 | 20.5 | 14.8 | 4.6 | 9.6 | 20.2 | 18.49 | -69.93 | |||

| 17 | Association of Authorized Master Builders | 2.3 | 24.1 | 18.7 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 7.4 | 21.2 | 18.49 | -69.89 | ||||

| 18 | María Auxiliadora School | 2.8 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 21.3 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 19.2 | 18.50 | -69.89 | ||

| 19 | Nuestra Señora del Carmen School | 4.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 20.9 | 16.9 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 6.4 | 31.6 | 21.0 | 18.51 | -69.90 | |

| 20 | Salomé Ureña School | 2.4 | 4.2 | 25.5 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 8.4 | 19.9 | 18.50 | -69.90 | ||||

| 21 | American School of Santo Domingo | 7.8 | 2.7 | 19.2 | 13.2 | 4.6 | 13.9 | 20.6 | 18.51 | -69.94 | ||||

| 22 | The Community For Learning | 3.1 | 20.0 | 18.9 | 2.2 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 16.9 | 20.2 | 18.51 | -69.97 | |||

| 23 | APEC University | 4.2 | 21.6 | 11.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 43.6 | 18.9 | 18.47 | -69.91 | |||

| 24 | Prof. Adolfo González School | 3.6 | 2.0 | 6.6 | 24.1 | 10.9 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 3.1 | 19.6 | 18.54 | -69.98 | ||

| 25 | Capotillo School | 3.2 | 3.5 | 15.5 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 19.9 | 18.50 | -69.90 | |||

| 26 | Aida Cartagena Portalatín School | 5.7 | 5.3 | 23.3 | 28.4 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 20.9 | 18.51 | -69.92 | ||||

| 27 | Arroyo Hondo School | 3.5 | 5.3 | 20.4 | 17.5 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 18.3 | 20.4 | 18.49 | -69.94 | |||

| 28 | Governorship of Mirador Sur Park | 3.8 | 23.9 | 8.3 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 18.44 | -69.96 | |||

| 29 | Agrarian Institute of Dominican Republic | 2.1 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 23.4 | 8.2 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 19.5 | 18.45 | -69.97 | ||

| 30 | Private residence | 2.4 | 5.6 | 26.0 | 10.9 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 20.1 | 18.46 | -69.96 |

References

- Anderson, J.O.; Thundiyil, J.G.; Stolbach, A. Clearing the Air: A Review of the Effects of Particulate Matter Air Pollution on Human Health. Journal of Medical Toxicology 2012, 8, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life; World Health Organization, 2002.

- Organization, W.H.; et al. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2. 5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide; World Health Organization, 2021.

- Goossens, J.; Jonckheere, A.C.; Dupont, L.J.; Bullens, D.M.A. Air Pollution and the Airways: Lessons from a Century of Human Urbanization. Atmosphere 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.S.; Ali, S.M.; ud din, M.I.; Subhani, M.A.; Anwar, M.N.; Nizami, A.S.; Ashraf, U.; Khokhar, M.F. An Emerged Challenge of Air Pollution and Ever-Increasing Particulate Matter in Pakistan; A Critical Review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123943. [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; Anenberg, S.C.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E.; Calatayud, V. Trends in urban air pollution over the last two decades: A global perspective. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 858, 160064. [CrossRef]

- Sanda, M.; Dunea, D.; Iordache, S.; Predescu, L.; Predescu, M.; Pohoata, A.; Onutu, I. Recent Urban Issues Related to Particulate Matter in Ploiesti City, Romania. Atmosphere 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Wang, S.; Li, M. The Impacts of Urban Form on PM2.5 Concentrations: A Regional Analysis of Cities in China from 2000 to 2015. Atmosphere 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Fu, B.; Zhu, Y. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Air Pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO) in the Inland Basin City of Chengdu, Southwest China. Atmosphere 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter (Final Report, Dec 2019). Technical Report EPA/600/R-19/188, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, 2019. Final Report.

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Brunekreef, B.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R.; et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The lancet 2017, 389, 1907–1918.

- Murray, C.J.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249.

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdisciplinary toxicology 2014, 7, 60.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Review of Evidence on Health Aspects of Air Pollution – REVIHAAP. Technical report, WHO Europe, Copenhagen, 2013. Accessed June 2025.

- Silva, R.A.; West, J.J.; Lamarque, J.F.; Shindell, D.T.; Collins, W.J.; Faluvegi, G.; Folberth, G.A.; Horowitz, L.W.; Nagashima, T.; Naik, V.; et al. Future global mortality from changes in air pollution attributable to climate change. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 647–651. [CrossRef]

- Dominici, F.; Peng, R.D.; Bell, M.L.; Pham, L.; McDermott, A.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M. Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Hospital Admission for Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases. JAMA 2006, 295, 1127–1134, [https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/articlepdf/202503/joc60023.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Yousuf, S.; Donald, A.N.; Hassan, A.M.M.; Iqbal, A.; Bodlah, M.A.; Sharf, B.; Noshia, N. A review on particulate matter and heavy metal emissions; impacts on the environment, detection techniques and control strategies. MOJ Ecology & Environmental Sciences 2021, 7, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.A.; Rushdi, A.I.; Bazeyad, A.; Al-Mutlaq, K.F. Temporal Variations, Air Quality, Heavy Metal Concentrations, and Environmental and Health Impacts of Atmospheric PM2.5 and PM10 in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Atmosphere 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Contini, D.; Cesari, D.; Donateo, A.; Chirizzi, D.; Belosi, F. Characterization of PM10 and PM2.5 and Their Metals Content in Different Typologies of Sites in South-Eastern Italy. Atmosphere 2014, 5, 435–453. [CrossRef]

- Alwadei, M.; Srivastava, D.; Alam, M.S.; Shi, Z.; Bloss, W.J. Chemical characteristics and source apportionment of particulate matter (PM2.5) in Dammam, Saudi Arabia: Impact of dust storms. Atmospheric Environment: X 2022, 14, 100164. [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Viana, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Artiñano, B.; Salvador, P.; Garcia do Santos, S.; Fernandez Patier, R.; Ruiz, C.; de la Rosa, J.; et al. Speciation and origin of PM10 and PM2.5 in Spain. Journal of Aerosol Science 2004, 35, 1151–1172. [CrossRef]

- Buseck, P.R.; Adachi, K. Nanoparticles in the Atmosphere. Elements 2008, 4, 389–394, [https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/msa/elements/article-pdf/4/6/389/3113124/389_v4n6.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Yin, J. Particulate matter in the atmosphere: which particle properties are important for its effects on health? Science of The Total Environment 2000, 249, 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jing, J.; Tao, J.; Hsu, S.C.; Wang, G.; Cao, J.; Lee, C.S.L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Chemical characterization and source apportionment of PM2.5 in Beijing: seasonal perspective. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2013, 13, 7053–7074. [CrossRef]

- Duffus, J.H. "Heavy metals"-A meaningless term. Chemistry International – Newsmagazine for IUPAC 2001, 23. [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. Zinc Biochemistry: From a Single Zinc Enzyme to a Key Element of Life. Advances in Nutrition 2013, 4, 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J., Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. In Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology: Volume 3: Environmental Toxicology; Springer Basel: Basel, 2012; pp. 133–164. [CrossRef]

- Pant, P.; Harrison, R.M. Estimation of the contribution of road traffic emissions to particulate matter concentrations from field measurements: A review. Atmospheric Environment 2013, 77, 78–97. [CrossRef]

- III, C.A.P.; and, D.W.D. Health Effects of Fine Particulate Air Pollution: Lines that Connect. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2006, 56, 709–742, [. [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M.T. Metals, Toxicity and Oxidative Stress. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2005, 12, 1161–1208. [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, G.; Shirmardi, M.; Naimabadi, A.; Ghadiri, A.; Sajedifar, J. Chemical and organic characteristics of PM2.5 particles and their in-vitro cytotoxic effects on lung cells: The Middle East dust storms in Ahvaz, Iran. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 655, 434–445. [CrossRef]

- Galeano-Páez, C.; Brango, H.; Pastor-Sierra, K.; Coneo-Pretelt, A.; Arteaga-Arroyo, G.; Peñata-Taborda, A.; Espitia-Pérez, P.; Ricardo-Caldera, D.; Humanez-Álvarez, A.; Londoño-Velasco, E.; et al. Genotoxicity and Cytotoxicity Induced In Vitro by Airborne Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from an Open-Cast Coal Mining Area. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1420. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ge, P.; Deng, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Toxicological responses of A549 and HCE-T cells exposed to fine particulate matter at the air–liquid interface. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 27375–27387. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, D.; Vicente, E.D.; Vicente, A.; Gonçalves, C.; Lopes, I.; Alves, C.A.; Oliveira, H. Toxicological and Mutagenic Effects of Particulate Matter from Domestic Activities. Toxics 2023, 11, 505. [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Li, R.; Chen, G.; Chen, S. Impact of Respiratory Dust on Health: A Comparison Based on the Toxicity of PM2.5, Silica, and Nanosilica. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7654. [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 0 ed.; CRC Press, 2000. [CrossRef]

- and, J.B. Bioindicators: Types, Development, and Use in Ecological Assessment and Research. Environmental Bioindicators 2006, 1, 22–39, [. [CrossRef]

- Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Da Silva, A.S.; Texcalac-Sangrador, J.L.; Moreno-Banda, G.L. Air pollution management and control in Latin America and the Caribbean: implications for climate change. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2016, 40, 150–159.

- Li, Q.Q.; Guo, Y.T.; Yang, J.Y.; Liang, C.S. Review on main sources and impacts of urban ultrafine particles: Traffic emissions, nucleation, and climate modulation. Atmospheric Environment: X 2023, 19, 100221. [CrossRef]

- Espinal, G.; Nivar, S. Estudio de la contaminación ambiental al interior de las viviendas en tres barrios de la capital dominicana. Ciencia y Sociedad 2004, 29, 167–212. [CrossRef]

- Caballero-González, C. Calidad del aire e infraestructura verde. Estudio de caso: Distrito Nacional. Master’s thesis, Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2020.

- Gómez Pérez, A.; Guillermo Manzanillo, L.A.; Vázquez Frías, J.; Quintana Pérez, C.E. Contaminación atmosférica en puntos seleccionados de la ciudad de Santo Domingo, República Dominicana. Ciencia y Sociedad 2014, 39, 533–557.

- Martinuzzi, S.; Locke, D.H.; Ramos-González, O.; Sanchez, M.; Grove, J.M.; Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Arendt, W.J.; Bauer, G. Exploring the relationships between tree canopy cover and socioeconomic characteristics in tropical urban systems: The case of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 62, 127125. [CrossRef]

- Matos-Espinosa, C.; Delanoy, R.; Caballero-González, C.; Hernández-Garces, A.; Jauregui-Haza, U.; Bonilla-Duarte, S.; Martínez-Batlle, J.R. Assessment of PM10 and PM2.5 Concentrations in Santo Domingo: A Comparative Study Between 2019 and 2022. Atmosphere 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Airmetrics. MiniVol Portable Air Sampler Operation Manual. Airmetrics, Eugene, OR, USA, 2007. Accessed: 15 August 2024.

- Airmetrics. MiniVol TAS Portable Air Sampler, 2024. Accessed: 12 August 2024.

- Skyray Instrument Inc.. RoHS4 Software, Version 1.1.47_110524_R. Skyray Instrument Inc., Kunshan, Jiangsu, China, 2009. Copyright © Skyray Instrument Inc.

- Skyray Instrument Inc.. RoHS4 User Manual. Skyray Instrument Inc., Kunshan, Jiangsu, China, 2010. Edition dated 2010-12-13.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1686. [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E.J. Multivariable geostatistics in S: the gstat package. Computers & Geosciences 2004, 30, 683–691.

- Gräler, B.; Pebesma, E.; Heuvelink, G. Spatio-Temporal Interpolation using gstat. The R Journal 2016, 8, 204–218.

- Hiemstra, P.; Pebesma, E.; Twenh"ofel, C.; Heuvelink, G. Real-time automatic interpolation of ambient gamma dose rates from the Dutch Radioactivity Monitoring Network. Computers & Geosciences 2008. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2008.10.011.

- Neuwirth, E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes, 2022. R package version 1.1-3.

- Lee, L. NADA: Nondetects and Data Analysis for Environmental Data, 2020. R package version 1.6-1.1.

- Stacklies, W.; Redestig, H.; Scholz, M.; Walther, D.; Selbig, J. pcaMethods – a Bioconductor package providing PCA methods for incomplete data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1164–1167.

- Shoari, N.; Dubé, J.S. Toward improved analysis of concentration data: embracing nondetects. Environmental toxicology and chemistry 2018, 37, 643–656.

- Matheron, G. Principles of geostatistics. Economic geology 1963, 58, 1246–1266.

- Cressie, N. Geostatistics. The American Statistician 1989, 43, 197–202.

- Isaaks, E.H.; Srivastava, R.M. Applied geostatistics: Oxford University Press. New York 1989, 561.

- Goovaerts, P.; et al. Geostatistics for natural resources evaluation; Oxford University Press on Demand, 1997.

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. Spatial Data Science: With applications in R; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. The R Journal 2018, 10, 439–446. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag New York, 2016.

- Pedersen, T.L. patchwork: The Composer of Plots, 2024. R package version 1.2.0.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 6200: Field Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry for the Determination of Elemental Concentrations in Soil and Sediment. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/6200.pdf, 2007. Revision 0.

- Beckhoff, B.; Kanngießer, H.B.; Langhoff, N.; Wedell, R.; Wolff, H., Eds. Handbook of Practical X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. Inorganic Mass Spectrometry: Principles and Applications; Wiley, 2008.

- Niu, J.; Rasmussen, P.E.; Wheeler, A.; Williams, R.; Chénier, M. Evaluation of airborne particulate matter and metals data in personal, indoor and outdoor environments using ED-XRF and ICP-MS and co-located duplicate samples. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44, 235–245. [CrossRef]

- PerkinElmer, Inc.. Sensitivity, Background, Noise, and Calibration in Atomic Spectroscopy: Effects on Accuracy and Detection Limits. White paper, PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA, 2018. pp. 1–11.

- WOLD, H. Estimation of principal components and related models by iterative least squares. Multivariate Analysis 1966, pp. 391–420.

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 1987, 2, 37–52. Proceedings of the Multivariate Statistical Workshop for Geologists and Geochemists, . [CrossRef]

- Celo, V.; Yassine, M.M.; Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E. Insights into Elemental Composition and Sources of Fine and Coarse Particulate Matter in Dense Traffic Areas in Toronto and Vancouver, Canada. Toxics 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Ryu, J.S.; Ra, K. Characteristics of potentially toxic elements and multi-isotope signatures (Cu, Zn, Pb) in non-exhaust traffic emission sources. Environmental Pollution 2022, 292, 118339. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, L.; He, X.; Au, W.C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, W.X.; Nah, T. Measurement report: Abundance and fractional solubilities of aerosol metals in urban Hong Kong – insights into factors that control aerosol metal dissolution in an urban site in South China. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2023, 23, 1403–1419. [CrossRef]

- Rasoazanany, E.O.; Andriamahenina, N.N.; Ravoson, H.N.; Andriambololona, R.; Randriamanivo, L.V.; Ramaherison, H.; Ahmed, H.; Harinoely, M. Air pollution studies in terms of PM2.5, PM2.5-10, PM10, lead and black carbon in urban areas of Antananarivo - Madagascar, 2012, [arXiv:physics.ao-ph/1204.1498].

- Laidlaw, M.A.; Filippelli, G.M. Resuspension of urban soils as a persistent source of lead poisoning in children: A review and new directions. Applied Geochemistry 2008, 23, 2021–2039. [CrossRef]

- Mielke, H.W.; Laidlaw, M.A.; Gonzales, C. Lead (Pb) legacy from vehicle traffic in eight California urbanized areas: Continuing influence of lead dust on children’s health. Science of The Total Environment 2010, 408, 3965–3975. [CrossRef]

- Resongles, E.; Dietze, V.; Green, D.C.; Harrison, R.M.; Ochoa-Gonzalez, R.; Tremper, A.H.; Weiss, D.J. Strong evidence for the continued contribution of lead deposited during the 20th century to the atmospheric environment in London of today. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2102791118, [https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.2102791118]. [CrossRef]

- O’Day, P.A.; Pattammattel, A.; Aronstein, P.; Leppert, V.J.; Forman, H.J. Iron Speciation in Respirable Particulate Matter and Implications for Human Health. Environmental Science & Technology 2022, 56, 7006–7016, [. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furutani, H.; Jung, J.; Miura, K.; Takami, A.; Kato, S.; Kajii, Y.; Uematsu, M. Single-particle chemical characterization and source apportionment of iron-containing atmospheric aerosols in Asian outflow. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2011, 116, [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2011JD015867]. [CrossRef]

- Spada, N.J.; Cheng, X.; White, W.H.; Hyslop, N.P. Decreasing Vanadium Footprint of Bunker Fuel Emissions. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52, 11528–11534, [. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Fairley, D.; Kleeman, M.J.; Harley, R.A. Effects of Switching to Lower Sulfur Marine Fuel Oil on Air Quality in the San Francisco Bay Area. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47, 10171–10178, [. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Romero, A.; González-Flórez, C.; Panta, A.; Yus-Díez, J.; Reche, C.; Córdoba, P.; Moreno, N.; Alastuey, A.; Kandler, K.; Klose, M.; et al. Variability in sediment particle size, mineralogy, and Fe mode of occurrence across dust-source inland drainage basins: the case of the lower Drâa Valley, Morocco. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2023, 23, 15815–15834. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Jones, A.M.; Lawrence, R.G. Major component composition of PM10 and PM2.5 from roadside and urban background sites. Atmospheric Environment 2004, 38, 4531–4538. [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Belis, C.A.; Dora, C.F.C.; Prüss-Ustün, A.M.; Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M. Contributions to cities’ ambient particulate matter (PM): A systematic review of local source contributions at global level. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 120, 475–483. [CrossRef]

- McComb, J.Q.; Rogers, C.; Han, F.X.; Tchounwou, P.B. Rapid Screening of Heavy Metals and Trace Elements in Environmental Samples Using Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer, A Comparative Study. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2014, 225, 2169. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ge, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.; Meng, X.; Wang, W.; Niu, C.; Kan, L.; Schikowski, T.; et al. Application of land use regression to assess exposure and identify potential sources in PM2.5, BC, NO2 concentrations. Atmospheric Environment 2020, 223, 117267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, N.; Li, S.; Dong, M.; Wang, X.; Ge, L.; Guo, T.; Li, W.; Gao, X. An Amended Chemical Mass Balance Model for Source Apportionment of PM2.5 in Typical Chinese Eastern Coastal Cities. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water 2019, 47, 1800115, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/clen.201800115]. [CrossRef]

| Metal | Mean | Median | Max | Min | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | Variance | N Censored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 2.48 | 2.40 | 4.9 | 1.17 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 10 |

| Cd | 3.20 | 2.50 | 10.0 | 0.58 | 2.39 | 0.44 | 5.71 | 11 |

| Cr | 4.04 | 3.70 | 10.2 | 1.31 | 2.08 | 0.38 | 4.32 | 6 |

| Cu | 21.89 | 22.00 | 26.2 | 19.00 | 1.98 | 0.36 | 3.91 | 0 |

| Fe | 13.32 | 12.90 | 28.0 | 4.94 | 6.10 | 1.11 | 37.19 | 14 |

| Ni | 6.29 | 6.75 | 8.0 | 2.40 | 1.40 | 0.26 | 1.97 | 1 |

| Pb | 6.78 | 6.10 | 12.2 | 2.27 | 3.10 | 0.57 | 9.60 | 7 |

| V | 13.07 | 9.32 | 36.9 | 2.41 | 9.18 | 1.68 | 84.32 | 15 |

| Zn | 20.04 | 19.80 | 22.0 | 17.90 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.80 | 0 |

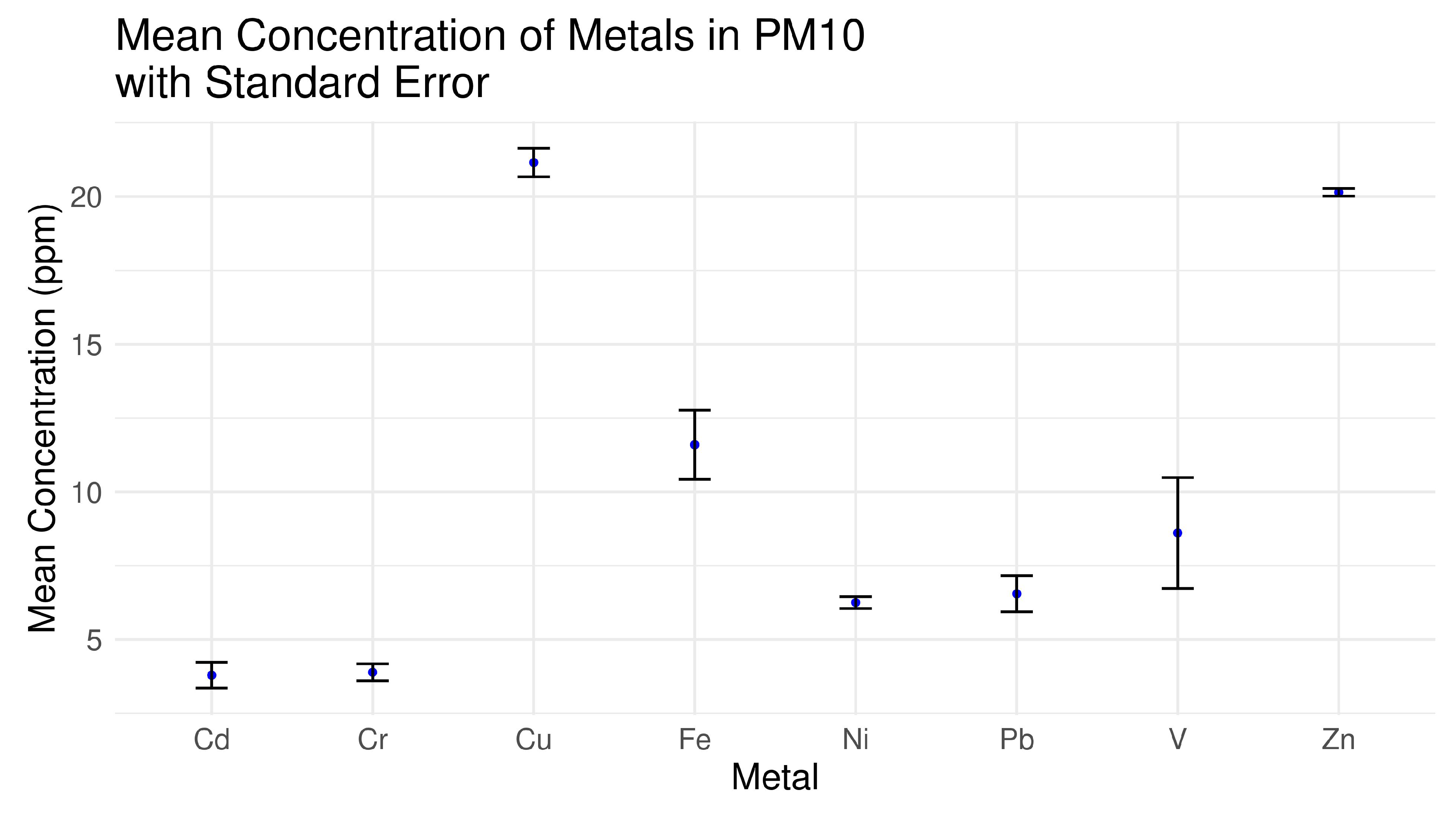

| Metal | Mean | Median | Max | Min | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | Variance | N Censored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 3.79 | 3.20 | 9.4 | 0.83 | 2.39 | 0.44 | 5.73 | 10 |

| Cr | 3.89 | 3.60 | 7.1 | 1.51 | 1.57 | 0.29 | 2.45 | 3 |

| Cu | 21.15 | 21.25 | 26.0 | 15.50 | 2.66 | 0.49 | 7.08 | 0 |

| Fe | 11.60 | 9.91 | 28.4 | 3.41 | 6.43 | 1.17 | 41.36 | 19 |

| Ni | 6.25 | 6.35 | 7.6 | 3.50 | 1.11 | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0 |

| Pb | 6.55 | 6.55 | 12.9 | 1.67 | 3.35 | 0.61 | 11.23 | 4 |

| V | 8.61 | 4.10 | 43.6 | 0.38 | 10.27 | 1.88 | 105.56 | 16 |

| Zn | 20.14 | 20.15 | 21.2 | 18.20 | 0.70 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).