Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

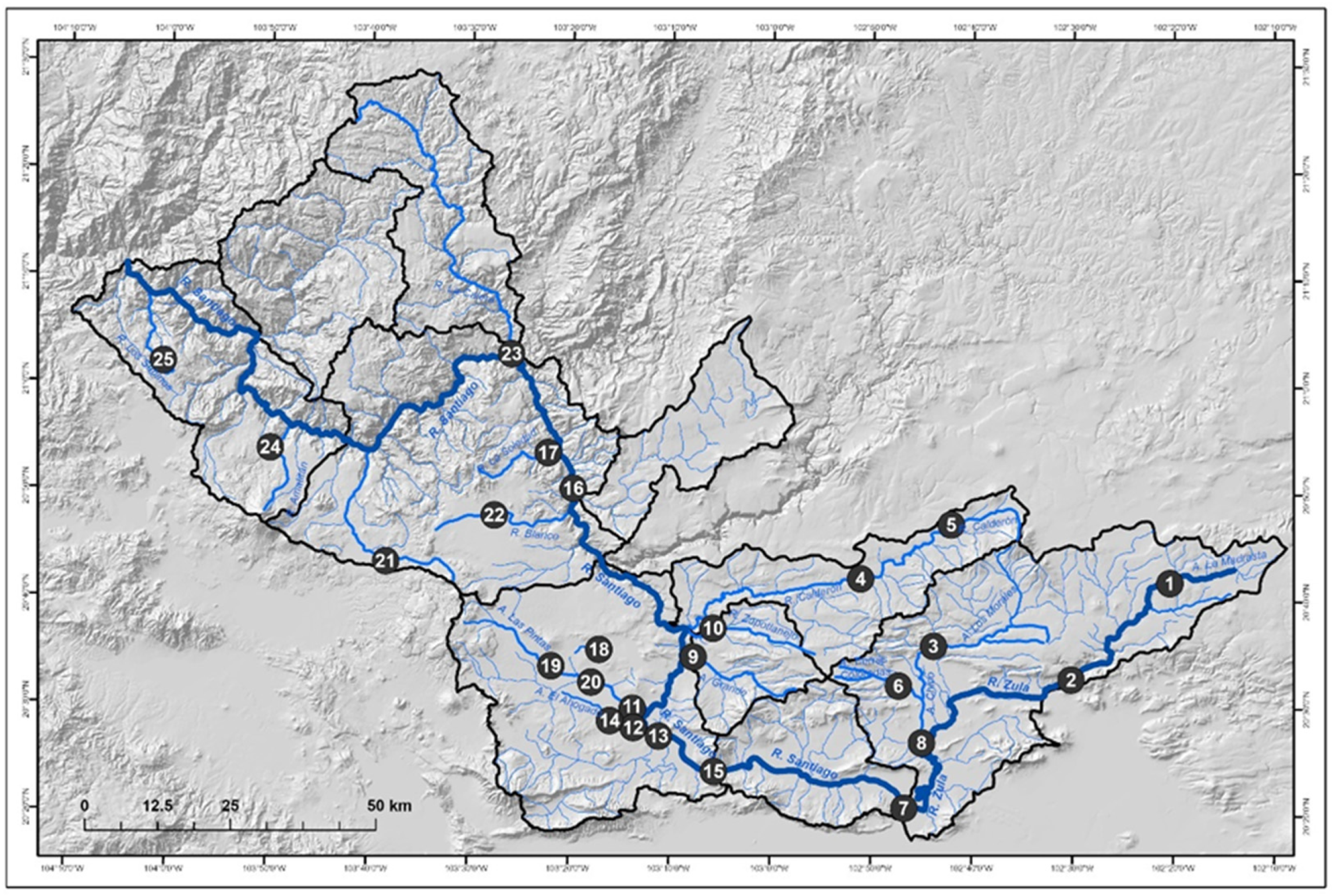

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Monitoring Stations

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Assessment Criteria

2.5. The Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI)

2.6. Human Health Risk Assessment

2.7. Exposure Assessment

2.8. Non-Cancerous Health Risk

2.9. Cancerous Health Risk

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Heavy Metals in the Monitoring Stations

3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Index

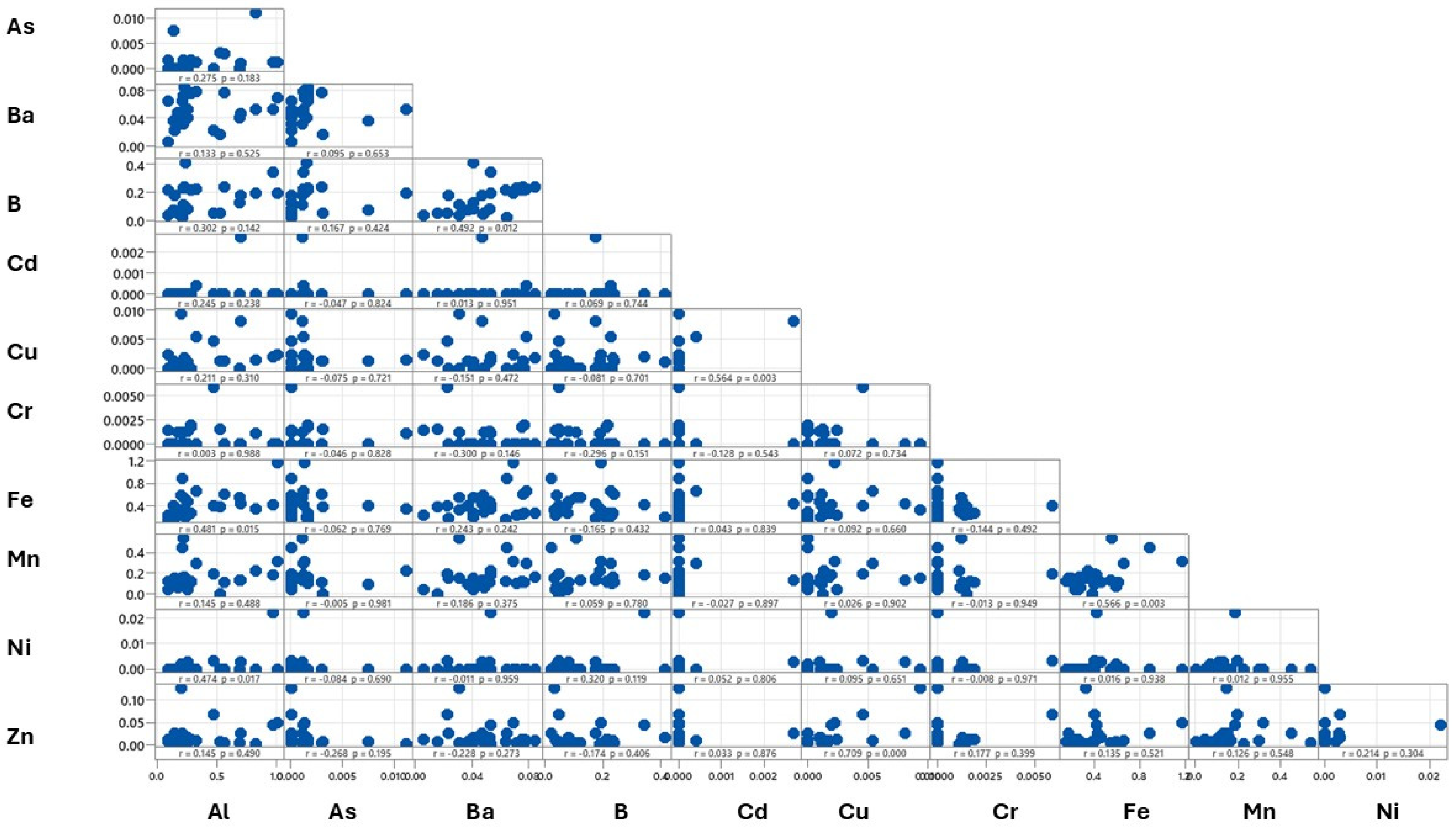

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Human Health Risk Assessment

3.4.1. Non-Cancerous Health Risks

3.4.2. Cancerous Health Risk

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANZECC & ARMCANZ | Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Freshwater and Marine Water Quality |

| CCME | Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment |

| CDI | Chronic Daily Intake |

| CSF | Cancer Slope Factor |

| FRA | Federal Rights Act |

| HI | Hazard Index |

| HHRA | Human Health Risk Assessment |

| HPI | Heavy Metal Pollution Index |

| HQ | Hazard quotients |

| ICO-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| ICP | Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectroscopy |

| MAG | Metropolitan Area of Guadalajara |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NSDEU | National Statistical Directory of Economic Units |

| RfD | Reference Dose |

| SGRB | Santiago-Guadalajara River Basin |

| STD | Standard Deviation |

| TCR | Total Carcinogenic Risk |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund |

| US EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| SGRB | Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Sampling site |

Official Name of the sampling site |

Name of the sampled tributary |

West Longitude |

North Latitude |

| 1 | Arandas | Arroyo La Madrastra | 102° 20' 23'' | 20° 41' 46'' |

| 2 | Atotonilco el Alto | Arroyo El Taretán | 102° 30' 09'' | 20° 32' 43'' |

| 3 | La Ladera | Arroyo Los Morales | 102° 43' 50'' | 20° 35' 50'' |

| 4 | Gaviotas | Río Calderón | 102° 51' 06'' | 20° 42' 06'' |

| 5 | San José de Gracia | Río Calderón | 102° 42' 07'' | 20° 47' 10'' |

| 6 | San Miguel | Arroyo Tierras Coloradas | 102° 47' 18'' | 20° 32' 06'' |

| 7 | Ocotlán Centro | Río Zula | 102° 46' 41'' | 20° 20' 41'' |

| 8 | Los Cerritos | Arroyo Chico | 102° 44' 58'' | 20° 26' 47'' |

| 9 | La Laja | Arroyo Grande | 103° 07' 40'' | 20° 34' 41'' |

| 10 | Río Zapotlanejo | Río Zapotlanejo | 103° 05' 44'' | 20° 37' 23'' |

| 11 | La Azucena | Arroyo El Ahogado | 103° 13' 40'' | 20° 29' 51'' |

| 12 | La Noria | Río Santiago | 103° 13' 35'' | 20° 28' 03'' |

| 13 | Río Santiago1 | Río Santiago | 103° 11' 04'' | 20° 27' 17'' |

| 14 | Carretera Guadalajara – Chapala | Arroyo Las Pintas | 103° 15' 55'' | 20° 28' 41'' |

| 15 | Presa Corona | Río Santiago | 103° 05' 35'' | 20° 24' 01'' |

| 16 | Paso a Guadalupe | Río Santiago | 103° 19' 44'' | 20° 50' 20'' |

| 17 | Rancho La Soledad | Río La Soledad | 103° 22' 15'' | 20° 53' 40'' |

| 18 | Plan de Oriente | Arroyo El Ahogado | 103° 17' 03'' | 20° 35' 19'' |

| 19 | Villa Fontana | Arroyo Las Pintas | 103° 21' 48'' | 20° 33' 46'' |

| 20 | San José del Quince | Arroyo El Ahogado | 103° 17' 48'' | 20° 32' 16'' |

| 21 | El Arenal | Río Arenal | 103° 38' 19'' | 20° 43' 24'' |

| 22 | San Isidro | Río Blanco | 103° 27' 34'' | 20° 47' 47'' |

| 23 | San Cristóbal de la Barranca | Río La Calera | 103° 25' 59'' | 21° 02' 51'' |

| 24 | Tequila | Río Amatitán | 103° 49' 54'' | 20° 53' 54'' |

| 25 | Hostotipaquillo | Río Los Sabinos | 104° 00' 40'' | 21° 01' 56'' |

References

- Ingrao, C.; Strippol,i R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water scarcity in agriculture: An overview of causes, impacts and approaches for reducing the risks. Heliyon 2023, 9(8), 18507. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Tapia, I.; Salazar-Martínez, T.; Acosta-Castro, M.; Meléndez-Castolo, K.A.; Mahlknecht, J.; Cervantes-Avilés, P.; Capparelli, M.V.; Mora, A. Occurrence of emerging organic contaminants and endocrine disruptors in different water compartments in Mexico–A review. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136285. [CrossRef]

- Ewaid, S.H.; Abed, S.A.; Al-Ansari, N.; Salih, R.M. Development and evaluation of a water quality index for the Iraqi rivers. Hydrology 2020, 7(3), 67. [CrossRef]

- Al-Addous, M.; Bdour, M.; Alnaief, M.; Rabaiah, S.; Schweimanns, N. Water resources in Jordan: a review of current challenges and future opportunities. Water 2023, 15(21), 3729. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. Urban flooding mitigation techniques: A systematic review and future studies. Water 2020, 12(12), 3579. [CrossRef]

- Tirgar, A.; Aghalari, Z.; Sillanpää, M.; Dahms, H.U. A glance at one decade of water pollution research in Iranian environmental health journals. International Journal of Food Contamination 2020, 7, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Water Releases by Chemical & Industry. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/trinationalanalysis/water-releases-chemical-industry (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Gikas, G.D.; Sylaios, G.K.; Tsihrintzis, V.A; Konstantinou, I.K., Albanis, T.; Boskidis, I. Comparative evaluation of river chemical status based on WFD methodology and CCME water quality index. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 745, 140849. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Chaudhary, M.; Singh, J. Waste management initiatives in India for human well being. European Scientific Journal 2015. Available online: https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/h16.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Chan, E.Y.Y.; Tong, K.H.Y.; Dubois, C.; Mc Donnell, K.; Kim, J.H.; Hung, K.K.C.; Kwok, K.O. Narrative review of primary preventive interventions against water-borne diseases: scientific evidence of health-EDRM in contexts with inadequate safe drinking water. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(23), 12268. [CrossRef]

- Velarde, L.; Nabavi, M.S.; Escalera, E.; Antti, M.L.; Akhtar, F. Adsorption of heavy metals on natural zeolites: A review. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138508. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ma, M.; Chen, H. A review on the removal of heavy metals from water by phosphorus-enriched biochar. Minerals 2024, 14(1), 61. [CrossRef]

- Velayatzadeh, M. Heavy metals in surface soils and crops. In Heavy Metals-Recent Advances 2023. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, P.; Wang, D.; Ren, X.; Wei, M. Statistical and multivariate statistical techniques to trace the sources and affecting factors of groundwater pollution in a rapidly growing city on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hossain, M.F.; Duan, C., Lu, J.; Tsang, Y.F.; Islam, M. S.; Zhou, Y. Isotherm models for adsorption of heavy metals from water-a review. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135545. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mazumder, M. J.; Al-Attas, O.; Husain, T. Heavy metals in drinking water: occurrences, implications, and future needs in developing countries. Science of the total Environment 2016, 569, 476-488. [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Azara, E.; Mammani, I.M.A.; De Miglio, M.R.; Zinellu, A.; ... Medici, S. Heavy metals in biological samples of cancer patients: a systematic literature review. BioMetals 2024, 1-15. doi.org/10.1007/s10534-024-00583-4.

- Nnaji, N.D.; Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; Ugwa, C. Bioaccumulation for heavy metal removal: a review. SN Applied Sciences 2023, 5(5), 125. [CrossRef]

- Zaynab, M.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Ameen, A.; Sharif, Y.; Ali, L.; Fatima, M.; ... Li, S. Health and environmental effects of heavy metals. Journal of King Saud University-Science 2022, 34(1), 101653. [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, S.; Krishnan, K.A.; Krishnakumar, A.; Maya, T. V., Dev, V.V.; Antony, S.; Arun, V. Monitoring of heavy metal contamination in Netravati river basin: overview of pollution indices and risk assessment. Sustainable Water Resources Management 2021, 7(2), 20. [CrossRef]

- Jaskuła, J.; Sojka, M. Assessment of spatial distribution of sediment contamination with heavy metals in the two biggest rivers in Poland. Catena 2022, 211, 105959. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, G.; Hu, Y.; Gao, D.; ... & Zhang, H. Ecological risk assessment and identification of the distinct microbial groups in heavy metal-polluted river sediments. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2023, 45(5), 1311-1329. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Ouyang, W.; Gu, X.; He, M.; Lin, C. Accelerated export and transportation of heavy metals in watersheds under high geological backgrounds. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 465, 133514. [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; García-Gamboa, M.; Sánchez-Luna, M.S.; Gloria-García, L.; Cervantes-Avilés, P.; Mahlknecht, J. A review of the current environmental status and human health implications of one of the most polluted rivers of Mexico: The Atoyac River, Puebla. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 782, 146788. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Castresana, G.; Castañeda Roldán, E.; García Suastegui, W.A.;Morán Perales, J.L.; Cruz Montalvo, A.; Handal Silva, A. Evaluation of health risks due to heavy metals in a rural population exposed to Atoyac River pollution in Puebla, Mexico. Water 2019, 11(2), 277. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Razo, I.; de Anda, J.; Barrios-Piña, H.; Olvera-Vargas, L.A.; García-Ruíz-García, M.; Hernández-Morales, S. Development of a Watershed Sustainability Index for the Santiago River Basin, Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15(10), 8428. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Arya, S.; Kumar, S. Industrial wastewater treatment: Current trends, bottlenecks, and best practices. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131245. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Molecular, clinical and environmental toxicology: volume 3: environmental toxicology 2012, 133-164. [CrossRef]

- Briseño-Bugarín, J.; Araujo-Padilla, X.; Escot-Espinoza, V.M.; Cardoso-Ortiz, J.; Flores de la Torre, J.A.; López-Luna, A. Lead (Pb) Pollution in Soil: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Contamination Grade and Health Risk in Mexico. Environments 2024, 11(3), 43. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, A.; Cortés, J.L.; Delgado, C.; Aguilar, Y.; Aguilar, D.; Cejudo, R.; ... Bautista, F. Heavy metal contamination (Cu, Pb, Zn, Fe, and Mn) in urban dust and its possible ecological and human health risk in Mexican cities. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 854460. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Gupta, P. Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution in Groundwater in the Hindon River Basin Using Pollution Index. In E3S Web of Conferences, 2024; Vol. 596, p. 01005. EDP Sciences. Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2024/126/e3sconf_iccmes2024_01005.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Ahirvar, B.P.; Das, P.; Srivastava, V.; Kumar, M. Perspectives of heavy metal pollution indices for soil, sediment, and water pollution evaluation: An insight. Total Environment Research Themes 2023, 6, 100039. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.M.; Swain, J.B. Modified heavy metal Pollution index (m-HPI) for surface water Quality in river basins, India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27(13), 15350-15364. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.K.; Ghosh, G.C.; Hossain, M.R.; Islam, M.S.; Habib, A., Zaman, S.; ... Khan, A.S. Human health risk and receptor model-oriented sources of heavy metal pollution in commonly consume vegetable and fish species of high Ganges river floodplain agro-ecological area, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8(10). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.; Cerda, V.; Cunha, F.A.; Lemos, V.A.; Teixeira, L.S.; dos Santos, W.N.; ... de Jesus, R.F. Application of human health risk indices in assessing contamination from chemical elements in food samples. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 117281. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Xie, F. Source-specific probabilistic health risk assessment of heavy metals in surface water of the Yangtze River Basin. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 926, 171923. [CrossRef]

- Chorol, L.; Gupta, S.K. Evaluation of groundwater heavy metal pollution index through analytical hierarchy process and its health risk assessment via Monte Carlo simulation. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2023, 170, 855-864. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.Z.; Gao, Z.D.; Li, K. M.; ... Zang, F. Pollution characteristics and probabilistic risk assessment of heavy metal (loid) s in agricultural soils across the Yellow River Basin, China. Ecological Indicators 2024, 167, 112676. [CrossRef]

- Bollo-Manent, M.; Montaño, R.; Hernández, J.R. Situación ambiental de la cuenca Santiago-Guadalajara., 1st ed. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental. Morelia, Michoacán, México, 2017. Available online: https://sigat.semadet.jalisco.gob.mx/pofa/index_archivos/libro/Libro%20SACRSG_vf.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Pedrozo-Acuña, A. Restauración de ríos, un paso hacia la sustentabilidad hídrica. PERSPECTIVAS IMTA 2020, 34, 5p. Available online: https://www.imta.gob.mx/gobmx/DOI/perspectivas/2020/b-imta-perspectivas-2020-34.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Díaz-Quiñonez, J.A. Tula Basin, the most polluted region in Mexico. Mexican Journal of Medical Research ICSA 2023, 11(22), I-II. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Peña, L.C.S.; Martínez-Acuña, M.I.; Del Razo, L.M. Arsenic and Fluoride in the Drinking Water in Tula City, México: Challenges and Lessons Learned. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2022, 233(6), 200. [CrossRef]

- Castresana, G.P.; Flores, V.T.; Reyes, L. L.; Aldana, F.H.,; Vega, R.C.; Perales, J.L.M.; ... Silva, A.H. Atoyac river pollution in the metropolitan area of Puebla, México. Water 2018, 10, 267. [CrossRef]

- Cotler Ávalos, H.; Mazari Hiriart, M.; de Anda Sánchez, J. Atlas de la cuenca Lerma-Chapala, construyendo una visión conjunta. Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, México, 2006. Available on line: https://agua.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/AtlasCuencaLermaChapala.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. Área Metropolitana de Guadalajara. Available on line: https://jalisco.gob.mx/jalisco/guadalajara (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- de Anda, J.; Shear, H.; Lugo-Melchor, O.Y.; Padilla-Tovar, L.E.; Bravo, S. D.; Olvera-Vargas, L.A. Use of the Pesticide Toxicity Index to Determine Potential Ecological Risk in the Santiago-Guadalajara River Basin, Mexico. Water 2024, 16(20), 3008. doi.org/10.3390/w16203008.

- McCulligh, C. Wastewater and wishful thinking: Treatment plants to “revive” the Santiago River in Mexico. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2023, 6(3), 1966-1986. [CrossRef]

- Riera, F.S.; Pulido, V.M.M.; Sánchez, I.L.D.R.; Hoffmeister, M. Integrated solutions to improve wastewater quality in Mendoza and Santiago River Basin. Water International 2024, 49(3-4), 517-531. [CrossRef]

- INEGI-DENUE. Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Aguascalientes, México. Available online: Available: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/default.aspx (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Srivastava, A.; Chinnasamy, P. Watershed development interventions for rural water safety, security, and sustainability in semi-arid region of Western-India. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26(7), 18231-18265. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Hong, Q.; Flower, R. Optimizing safe and just operating spaces at sub-watershed scales to guide local environmental management. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 398, 136530. [CrossRef]

- US EPA. SW-846 Test Method 3005A: Acid Digestion of Waters for Total Recoverable or Dissolved Metals for Analysis by Flame Atomic Absorption (FLAA) or Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Spectroscopy. United States Environmental Protection Agency, USA. Available on line: https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-3005a-acid-digestion-waters-total-recoverable-or-dissolved-metals (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- NMX-AA-051-SCFI-2001. Water analysis - Determination of metals by atomic absorption in natural, potable, residual, and treated residual waters. Secretaría de Economía, México. Available on line: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/166785/NMX-AA-051-SCFI-2001.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- NIST. NIST Policy on Metrological Traceability. National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA. Available on line: https://www.nist.gov/calibrations/traceability (accessed 04Jan 2025).

- LFD. Ley Federal de Derechos. Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión. México. Available on line: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/ref/lfd.htm (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- US EPA. Justification of Appropriation Estimates for the Committee on Appropriations. United States Environmental Protection Agency, USA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-04/fy24-cj-03-goal-objective-overview.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- CCME. Water-Aquatic Life. Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life. Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Available online: https://ccme.ca/en/resources/water-aquatic-life (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- ANZECC & ARMCANZ. Toxicant default guideline values for aquatic ecosystems — technical briefs. Metals and Metalloids. Australian Government Initiative. Available online: https://www.waterquality.gov.au/anz-guidelines/guideline-values/default/water-quality-toxicants/toxicants (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Mohan, S.V.; Nithila, P.; Reddy, S.J. Estimation of heavy metals in drinking water and development of heavy metal pollution index. Journal of Environmental Science & Health Part A 1996, 31(2), 283-289. doi.org/10.1080/10934529609376357.

- Asim, M.; Nageswara Rao, K. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in Yamuna River, Delhi-NCR, using heavy metal pollution index and GIS. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193(2), 103. [CrossRef]

- Caeiro, S.; Costa, M. H.; Ramos, T. B.; Fernandes, F.; Silveira, N.; Coimbra, A.; ... Painho, M. Assessing heavy metal contamination in Sado Estuary sediment: an index analysis approach. Ecological indicators 2005, 5(2), 151-169. [CrossRef]

- Hartiningsih, D.; Diana, S.; Yuniarti, M.S.; Ismail, M.R.; Sari, Q.W. Water quality pollution indices to assess the heavy metal contamination: A case study of the estuarine waters in Cirebon City (West Java, Indonesia) Pre-and post-CARE COVID-19. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2024, 21, 100318. doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2023.100318.

- Bamuwamye, M.; Ogwok, P.,; Tumuhairwe, V.; Eragu, R.; Nakisozi, H.; Ogwang, P. E. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in Kampala (Uganda) drinking water. Journal of Food Research 2017; 6(4), 6-12. [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S.; Jesuraja, K.; Roy, P.D.; Venkatramanan, S.; Khan, R., Shukla, S.; ... Muthukumar, P. Human health risk assessment of heavy metal and pathogenic contamination in surface water of the Punnakayal estuary, South India. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134027. doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134027.

- U.S. EPA. Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final Report). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-09/052F, 2011. Available on line: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=236252 (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- US EPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund. Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part E, Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. EPA/540/R/99. 2011. Available on line: https://www.epa.gov/risk/risk-assessment-guidance-superfund-rags-part-e (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- US EPA. Guidelines for ecological risk assessment. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC, USA. 1998. Avaiable on line: https://www.epa.gov/risk/guidelines-ecological-risk-assessment (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Tokatli, C.; Ustaoğlu, F. Health risk assessment of toxicants in Meriç river delta wetland, thrace region, Turkey. Environmental earth sciences 2020, 79(18), 426. [CrossRef]

- de Anda, J.; Olvera-Vargas, L.A.; Lugo-Melchor, O.Y.; Shear, H. Ecological Risk Assessment to Aquatic Life from Metals in the Surface Sediments of the Santiago-Guadalajara River Basin, Mexico. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal 2024, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Ghaisas, N.A.; Maiti, K.; Roy, A. Iron-Mediated Organic Matter Preservation in the Mississippi River-Influenced Shelf Sediments. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2021, 126(4), e2020JG006089. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, A.; Lázaro, I.; Razo, I.; Briones-Gallardo, R. Geochemical and mineralogical characterization of stream sediments impacted by mine wastes containing arsenic, cadmium and lead in North-Central Mexico. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2021, 221, 106707. [CrossRef]

- Valladares, L.D.L.S.,; Vargas-Luque, A.; Borja-Castro, L.; Valencia-Bedregal, R.; de Jesús Velazquez-Garcia, J.; Barnes, E.P.; ... Barnes, C.H.W. Physical and chemical techniques for a comprehensive characterization of river sediment: A case of study, the Moquegua River, Peru. International Journal of Sediment Research 2024, 39(3), 478-494. [CrossRef]

- Salcedo Sánchez, E.R.; Martínez, J.M.E.; Morales, M.M.; Talavera Mendoza, O.; Alberich, M.V.E. Ecological and health risk assessment of potential toxic elements from a mining area (water and sediments): the San Juan-Taxco River system, Guerrero, Mexico. Water 2022, 14(4), 518. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.; Bux, R.K., Medina, D.I.; Barrios-Piña, H.; Mahlknecht, J. Spatial and multivariate statistical analyses of human health risk associated with the consumption of heavy metals in groundwater of Monterrey Metropolitan Area, Mexico. Water 2023, 15(6), 1243. [CrossRef]

- A Biasi, L.; de las Mercedes, A.; Messina, D.G.A.; Gómez, D.; Noemi, N. Determinación de Zinc en muestras de agua de ríos y red de la provincia de San Luis y aguas envasadas. Diaeta 2020, 38(173), 38-48. Available on line: https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/diaeta/v38n173/1852-7337-diaeta-38-173-38.pdf (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Y. Wang et al., “Assessment of heavy metals in surface water, sediment and macrozoobenthos in inland rivers: a case study of the Heihe River, Northwest China,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 29, no. 23, pp. 35253–35268, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Feng, C.; Li, Y.; Yin, L.; Shen, Z. Heavy metal pollution in the surface water of the Yangtze Estuary: a 5-year follow-up study. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 718-725. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, Y.; Lei, M.; ... Zhang, Z. Process, influencing factors, and simulation of the lateral transport of heavy metals in surface runoff in a mining area driven by rainfall: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 857, 159119. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, B.; ... Dong, H. Contamination characteristics, source analysis and health risk assessment of heavy metals in the soil in Shi River Basin in China based on high density sampling. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 227, 112926. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, C.; Aguilar, C.; Argaes, J.; Cerón, R.M.; Cerón, J.G.; Amador L.E.; Ramírez, M.A. Cuantificación de los niveles de metales pesados en el río Palizada. In Análisis del Espacio Urbano y sus Consecuencias Ambientales en la Región de la Laguna de Términos, Villegas Sierra, J., Cerón Bretón R.M. (Coord.). Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, México, 2018, ch. 9, pp. 181–213. Avaiabe on line: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326812827_Cuantificacion_de_los_niveles_de_metales_pesados_en_el_rio_Palizada (accessed 04 Jan 2025).

- Figueroa, E.C. La población en riesgo y la calidad del agua al sur de la Zona Metropolitana de Guadalajara (Jalisco, México). Agua y territorio= Water and Landscape 2021, (17), 55-76. [CrossRef]

- McCulligh, C.; Arellano-García, L.; Casas-Beltrán, D. Unsafe waters: the hydrosocial cycle of drinking water in Western Mexico. Local Environment 2020, 25(8), 576-596. [CrossRef]

- McCulligh, C.; Vega Fregoso, G. Defiance from Down River: deflection and dispute in the urban-industrial metabolism of pollution in Guadalajara. Sustainability 2019, 11(22), 6294. [CrossRef]

- Graffelman, J.; De Leeuw, J. Improved approximation and visualization of the correlation matrix. The American Statistician 2023, 77(4), 432-442. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, G.; Franzoni, V. Discovering correlation indices for link prediction using differential evolution. Mathematics 2020, 8(11), 2097. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Metin, M.; Altay, V.; Bhat, R. A.; Ejaz, M., Gul, A.; ... Kawano, T. Arsenic and human health: genotoxicity, epigenomic effects, and cancer signaling. Biological Trace Element Research 2022, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Garkal, A.; Sarode, L.; Bangar, P.; Mehta, T.; Singh, D. P.; Rawal, R. Understanding arsenic toxicity: Implications for environmental exposure and human health. Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters 2024, 5, 100090. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, I.; Umar, R. Status of heavy metals and metalloid concentrations in water resources and associated health risks in parts of Indo-Gangetic plain, India. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2023, 23, 101047. [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Zeng, Q.; Luo, P.; Yang, G.; Li, J.; Sun, B.; ... Zhang, A. Assessing the health risks of coal-burning arsenic-induced skin damage: A 22-year follow-up study in Guizhou, China. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 905, 167236. [CrossRef]

- Althobaiti, N.A. Heavy metals exposure and Alzheimer’s disease: Underlying mechanisms and advancing therapeutic approaches. Behavioural Brain Research 2024, 115212. [CrossRef]

- Z Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Song, Z.; Bi, Y.; ... Zhang, S. Early-life lead exposure induces long-term toxicity in the central nervous system: From zebrafish larvae to juveniles and adults. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 804, 150185. [CrossRef]

- Dike, C.; Antia, M.; Bababtunde, B.; Sikoki, F.; Ezejiofor, A. Cognitive, Sensory, and Motor Impairments Associated with Aluminium, Manganese, Mercury and Lead Exposures in the Onset of Neurodegeneration. IPS Journal of Public Health 2023, 2(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Elegbede, I.O.; Ndimele, P.E.; Mekuleyi, G.O.; Oladipupo, I.O; Mustapha, A.A. Comprehensive geochemical assessment, probable ecological and human health risks of heavy metals in water and sediments from dredged and non-dredged Rivers in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 12, 100379. [CrossRef]

- Ugbede, F.O.; Aduo, B.C.; Ogbonna, O.N.; Ekoh, O.C. Natural radionuclides, heavy metals and health risk assessment in surface water of Nkalagu river dam with statistical analysis. Scientific African 2020, 8, e00439. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, D.; Valand, M.; Vachhrajani, K. Assessment of seasonal variations in soil heavy metal concentrations and potential health risks in Gujarat, India. Environmental geochemistry and health 2024, 46(10), 391. [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, E. D.; Nwachukwu, E.D. Heavy metal content and health risk assessment of a South-eastern Nigeria River. Applied Water Science 2020, 10(9), 210. [CrossRef]

- Lipy, E.P.; Mohanta, L.C.; Islam, D.; Lyzu, C., Akhter, S.; Hakim, M. The impact of feeding pattern on heavy metal accumulation and associated health risks in fishes from the Dhaleshwari River Bangladesh. Heliyon 2024, 10(23). [CrossRef]

- Teschke, R. Copper, Iron, Cadmium, and Arsenic, All Generated in the Universe: Elucidating Their Environmental Impact Risk on Human Health Including Clinical Liver Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(12), 6662. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. Ecological and health risk assessments and water quality criteria of heavy metals in the Haihe River. Environmental Pollution 2021, 290, 117971. [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, M.; Alemu, T.; Shasho, E. Heavy Metals Pollution and Potential Health Risks: The Case of the Koche River, Tatek Industrial Zone, Burayu, Ethiopia. Journal of Toxicology 2024, 2024(1), 9425206. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M. N.; Anees, M. T.; Ansari, E.; Ja’afar, J. B.; Danish, M.; Bakar, E. A. Baseline Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution during COVID-19 near River Mouth of Kerian River, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14(7), 3976. [CrossRef]

- Bmh, A.T. Preliminary Assessment of Several Heavy Metal Ions (Fe, Cu, Ni, Zn, Cr, Pb, and Cd) in Water, Sediment, Ceratophyllum demersum, and Potamogeton pectinatus Plants from Marsh Al-Hawizeh, Iraq. Journal of Water and Environment Technology 2021, 19(4), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.M.; Abdulkareem, M.N.; Muhammad, A.; Hamza, K. Environmental Impact Assessment Of Heavy Metals Effluient (Chromium & Nickel) Released Into Romi River, Kaduna State: A Case Study. Fudma Journal of Sciences 2020, 4(3), 704-707. Available on line: https://fjs.fudutsinma.edu.ng/index.php/fjs/article/view/283.

| Heavy metal | Symbol | Detection limit (mg/L) |

| Aluminum | Al | < 0.05 |

| Arsenic | As | < 0.01 |

| Boron | B | < 0.001 |

| Barium | Ba | < 0.01 |

| Cadmium | Cd | < 0.002 |

| Total Chromium | Cr | < 0.01 |

| Copper | Cu | < 0.01 |

| Iron | Fe | < 0.01 |

| Mercury | Hg | < 0.001 |

| Manganese | Mn | < 0.01 |

| Nickel | Ni | < 0.01 |

| Lead | Pb | < 0.01 |

| Antimony | Sb | < 0.005 |

| Selenium | Se | < 0.002 |

| Zinc | Zn | < 0.01 |

| Heavy metal | Symbol | Federal Rights Act | Fresh-water CMC1 (acute) | Fresh-water CCC2 (chronic) | Long-term exposure | Short-term exposure | Guidelines for fresh and marine water quality |

| FRA [55] | US EPA [56] | US EPA [56] | CCME [57] | CCME [57] | ANZECC & ARMCANZ [58] | ||

| µg/L | µg/L | µg/L | µg/L | µg/L | µg/L | ||

| Aluminum | Al | 50.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 55.000 |

| Antimony | Sb | 90.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 9.000 |

| Arsenic | As | 200.000 | 340.000 | 150.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 24.000 |

| Barium | Ba | 10.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Boron | B | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 1,500.000 | 29,000.000 | 940.000 |

| Cadmium | Cd | 4.000 | 1.800 | N.D. | 0.090 | 1.000 | 0.200 |

| Copper | Cu | 50.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.470 |

| Total Chrome | Cr | 50.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Cr (III) | Cr+3 | N.D. | 570.000 | 74.000 | 8.900 | 8.900 | 3.300 |

| Cr (VI) | Cr+6 | N.D. | 16.000 | 11.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Iron | Fe | 1,000.000 | N.D. | 1,000.000 | N.D. | N.D. | 300.000 |

| Manganese | Mn | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 430.000 | 3,600.000 | 1,900.000 |

| Mercury | Hg | 0.500 | 1.400 | 0.770 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.600 |

| Nickel | Ni | 600.000 | 470.000 | 52.000 | 87.000 | 87.000 | 11.000 |

| Lead | Pb | 30.000 | 65.000 | 2.500 | N.D. | N.D. | 3.400 |

| Selenium | Se | 8.000 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 11.000 |

| Zinc | Zn | 20.000 | 120.000 | 120.000 | 7.000 | 37.000 | 8.000 |

| Monitoring Stations | Al | As | Ba | B | Cd | Cu | Cr | Fe | Mn | Ni | Zn |

| S1 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.885 | 0.452 | 0.000 | 0.026 |

| S2 | 0.094 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.232 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.012 |

| S3 | 0.205 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.591 | 0.069 | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| S4 | 0.178 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.285 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| S5 | 0.138 | 0.008 | 0.037 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.405 | 0.093 | 0.000 | 0.006 |

| S6 | 0.260 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.078 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| S7 | 0.558 | 0.003 | 0.076 | 0.240 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.611 | 0.109 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| S8 | 0.687 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.545 | 0.132 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| S9 | 0.328 | 0.001 | 0.078 | 0.228 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.658 | 0.300 | 0.000 | 0.009 |

| S10 | 0.474 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.401 | 0.195 | 0.003 | 0.067 |

| S11 | 0.235 | 0.002 | 0.041 | 0.415 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.193 | 0.155 | 0.000 | 0.016 |

| S12 | 0.282 | 0.002 | 0.077 | 0.215 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.261 | 0.116 | 0.000 | 0.011 |

| S13 | 0.218 | 0.002 | 0.072 | 0.234 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.222 | 0.104 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| S14 | 0.281 | 0.002 | 0.076 | 0.214 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.254 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| S15 | 0.099 | 0.002 | 0.064 | 0.217 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.158 | 0.126 | 0.000 | 0.006 |

| S16 | 0.697 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.177 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.434 | 0.128 | 0.003 | 0.026 |

| S17 | 0.522 | 0.003 | 0.016 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.387 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| S18 | 1.007 | 0.001 | 0.070 | 0.193 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 1.174 | 0.320 | 0.000 | 0.048 |

| S19 | 0.146 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.178 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.173 | 0.153 | 0.000 | 0.025 |

| S20 | 0.966 | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.343 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.420 | 0.187 | 0.022 | 0.043 |

| S21 | 0.222 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.553 | 0.544 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| S22 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.331 | 0.148 | 0.000 | 0.128 |

| S23 | 0.822 | 0.011 | 0.053 | 0.191 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.347 | 0.228 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| S24 | 0.253 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.464 | 0.112 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| S25 | 0.233 | 0.002 | 0.085 | 0.236 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.272 | 0.168 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| Min | 0.094 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.158 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Max | 1.007 | 0.011 | 0.085 | 0.415 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 1.174 | 0.544 | 0.022 | 0.128 |

| Mean | 0.372 | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.153 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.421 | 0.165 | 0.001 | 0.020 |

| SD | 0.269 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.103 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.236 | 0.125 | 0.004 | 0.028 |

| Heavy metal | Mean Concentration (mg/L) | (Si) | (Ii) | (Wi) | (Qi) | WiQi | HPI |

| Al | 0.372 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 18.182 | 6,449.096 | 117,256.283 | 277.572 |

| As | 0.002 | 0.340 | 0.005 | 2.941 | 0.896 | 2.634 | 0.006 |

| Ba | 0.050 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 100.000 | 501.360 | 50,136.000 | 118.683 |

| B | 0.153 | 29.000 | 0.940 | 0.034 | 2.794 | 0.096 | 0.000 |

| Cd | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 250.000 | 0.870 | 217.391 | 0.515 |

| Cu | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 20.000 | 2.532 | 50.636 | 0.120 |

| Cr | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 20.000 | 1.378 | 27.556 | 0.065 |

| Fe | 0.421 | 1.000 | 0.300 | 1.000 | 17.255 | 17.255 | 0.041 |

| Mn | 0.165 | 3.600 | 0.430 | 0.278 | 8.360 | 2.322 | 0.005 |

| Ni | 0.001 | 0.600 | 0.011 | 1.667 | 1.698 | 2.830 | 0.007 |

| Zn | 0.020 | 0.120 | 0.007 | 8.333 | 11.504 | 95.870 | 0.227 |

|

Sampling station |

HPI | STD |

Sampling station |

HPI | STD |

| S1 | 331.960 | ± 67.307 | S14 | 378.107 | ± 76.531 |

| S2 | 72.238 | ± 17.685 | S15 | 193.424 | ± 46.154 |

| S3 | 156.798 | ± 35.396 | S16 | 195.640 | ± 35.315 |

| S4 | 449.830 | ± 73.230 | S17 | 80.952 | ± 16.351 |

| S5 | 163.180 | ± 33.064 | S18 | 209.048 | ± 50.104 |

| S6 | 140.513 | ± 30.860 | S19 | 137.450 | ± 28.418 |

| S7 | 618.045 | ± 137.569 | S20 | 914.455 | ± 236.881 |

| S8 | 139.547 | ± 30.602 | S21 | 221.258 | ± 47.736 |

| S9 | 430.390 | ± 86.589 | S22 | 205.968 | ± 42.750 |

| S10 | 419.711 | ± 109.551 | S23 | 790.226 | ± 200.020 |

| S11 | 256.725 | ± 53.726 | S24 | 299.991 | ± 61.602 |

| S12 | 382.528 | ± 77.401 | S25 | 358.711 | ± 73.150 |

| S13 | 314.205 | ± 63.775 | Mean | 314.436 |

| Heavy metal | Al | As | Ba | B | Cd | Cu | Cr | Fe | Mn | Ni | Zn |

| Al | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| As | 0.275 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Ba | 0.133 | 0.095 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| B | 0.302 | 0.167 | 0.492* | 1.000 | |||||||

| Cd | 0.245 | -0.047 | 0.013 | 0.069 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Cu | 0.211 | -0.075 | -0.151 | -0.081 | 0.564* | 1.000 | |||||

| Total Cr | 0.003 | -0.046 | -0.3 | -0.296 | -0.128 | 0.072 | 1.000 | ||||

| Fe | 0.481* | -0.062 | 0.243 | -0.165 | 0.043 | 0.092 | -0.144 | 1.000 | |||

| Mn | 0.145 | -0.005 | 0.186 | 0.059 | -0.027 | 0.026 | -0.013 | 0.566* | 1.000 | ||

| Ni | 0.474* | -0.084 | -0.011 | 0.32 | 0.052 | 0.095 | -0.008 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 1.000 | |

| Zn | 0.145 | -0.268 | -0.228 | -0.174 | 0.033 | 0.709* | 0.177 | 0.135 | 0.126 | 0.214 | 1.000 |

|

Monitoring Stations |

HQChildren | HI | HQAdults | HI | ||||||||||||||

| As | Cd | Cu | Cr | Fe | Ni | Pb | Zn | As | Cd | Cu | Cr | Fe | Ni | Pb | Zn | |||

| S1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.104 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.087 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.090 |

| S2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.077 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.106 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.041 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.067 |

| S3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.062 |

| S4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.066 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.099 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.064 |

| S5 | 0.820 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.868 | 0.723 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.765 |

| S6 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.026 |

| S7 | 0.328 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.399 | 0.289 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.351 |

| S8 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 |

| S9 | 0.131 | 0.052 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.264 | 0.116 | 0.035 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.220 |

| S10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.323 | 0.046 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.385 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.174 | 0.040 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.227 |

| S11 | 0.164 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.189 | 0.145 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.166 |

| S12 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.104 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.310 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.056 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.237 |

| S13 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.201 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.177 |

| S14 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.093 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.298 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.230 |

| S15 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.194 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.170 |

| S16 | 0.119 | 0.351 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.534 | 0.105 | 0.235 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.395 |

| S17 | 0.339 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.082 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.467 | 0.299 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.044 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.383 |

| S18 | 0.142 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.000 | 0.544 | 0.005 | 0.827 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.000 | 0.478 | 0.005 | 0.725 |

| S19 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| S20 | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.037 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.222 | 0.116 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.195 |

| S21 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.252 | 0.107 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.198 |

| S22 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.052 |

| S23 | 1.225 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.326 | 1.080 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.148 |

| S24 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.071 | 0.053 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.046 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.090 |

| S25 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.209 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.183 |

| Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.019 |

| Max | 1.225 | 0.351 | 0.008 | 0.323 | 0.134 | 0.037 | 0.544 | 0.014 | 1.326 | 1.080 | 0.235 | 0.007 | 0.174 | 0.116 | 0.032 | 0.478 | 0.012 | 1.148 |

| Mean | 0.176 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.305 | 0.155 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.252 |

| Samples exceeding the limit |

1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| % of samples exceeding the limit |

4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| Monitoring | CR in Children | TCR | CR in Adults | TCR | ||||||||

| Stations | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | ||

| S1 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| S2 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.0E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.0E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.7E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.7E-05 |

| S3 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 9.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 9.8E-05 |

| S4 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.2E-05 |

| S5 | 3.6E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.6E-04 | 3.2E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.2E-04 |

| S6 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| S7 | 1.5E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.5E-04 | 1.3E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.3E-04 |

| S8 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| S9 | 5.8E-05 | 7.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.4E-04 | 5.2E-05 | 7.0E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.2E-04 |

| S10 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 2.5E-04 | 1.7E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 4.2E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.6E-04 | 1.5E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 3.0E-04 |

| S11 | 7.3E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 7.3E-05 | 6.5E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.5E-05 |

| S12 | 7.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 8.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.6E-04 | 6.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 5.0E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.2E-04 |

| S13 | 7.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 7.8E-05 | 6.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.9E-05 |

| S14 | 7.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 7.3E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.5E-04 | 6.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 4.5E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-04 |

| S15 | 7.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 7.8E-05 | 6.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.9E-05 |

| S16 | 5.3E-05 | 5.3E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 1.4E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 7.3E-04 | 4.7E-05 | 4.7E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 1.3E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 6.5E-04 |

| S17 | 1.5E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 6.5E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 2.1E-04 | 1.3E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 4.0E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.7E-04 |

| S18 | 6.3E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.6E-06 | 7.0E-05 | 5.6E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.7E-06 | 6.2E-05 |

| S19 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| S20 | 5.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.2E-03 | 0.0E+00 | 1.3E-03 | 5.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-03 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-03 |

| S21 | 5.4E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 5.3E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 1.1E-04 | 4.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 3.2E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 8.0E-05 |

| S22 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| S23 | 5.4E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 4.7E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.9E-04 | 4.8E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 2.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.1E-04 |

| S24 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 5.6E-05 | 1.5E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 2.1E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 3.4E-05 | 1.4E-04 | 0.0E+00 | 1.7E-04 |

| S25 | 7.8E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 7.8E-05 | 6.9E-05 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 6.9E-05 |

| Min | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 | 0.0E+00 |

| Max | 5.4E-04 | 5.3E-04 | 2.5E-04 | 1.2E-03 | 6.6E-06 | 1.3E-03 | 4.8E-04 | 4.7E-04 | 1.6E-04 | 1.1E-03 | 5.7E-06 | 1.1E-03 |

| Mean | 7.8E-05 | 2.4E-05 | 3.0E-05 | 7.2E-05 | 2.6E-07 | 2.0E-04 | 6.9E-05 | 2.2E-05 | 1.8E-05 | 6.4E-05 | 2.3E-07 | 1.7E-04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).