Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Additional Sampling, Instrumentation, and Analysis in 2024

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Long-Term Trends in PM2.5 Composition

3.1.1. Carbonaceous Species: Organic Carbon and Elemental Carbon

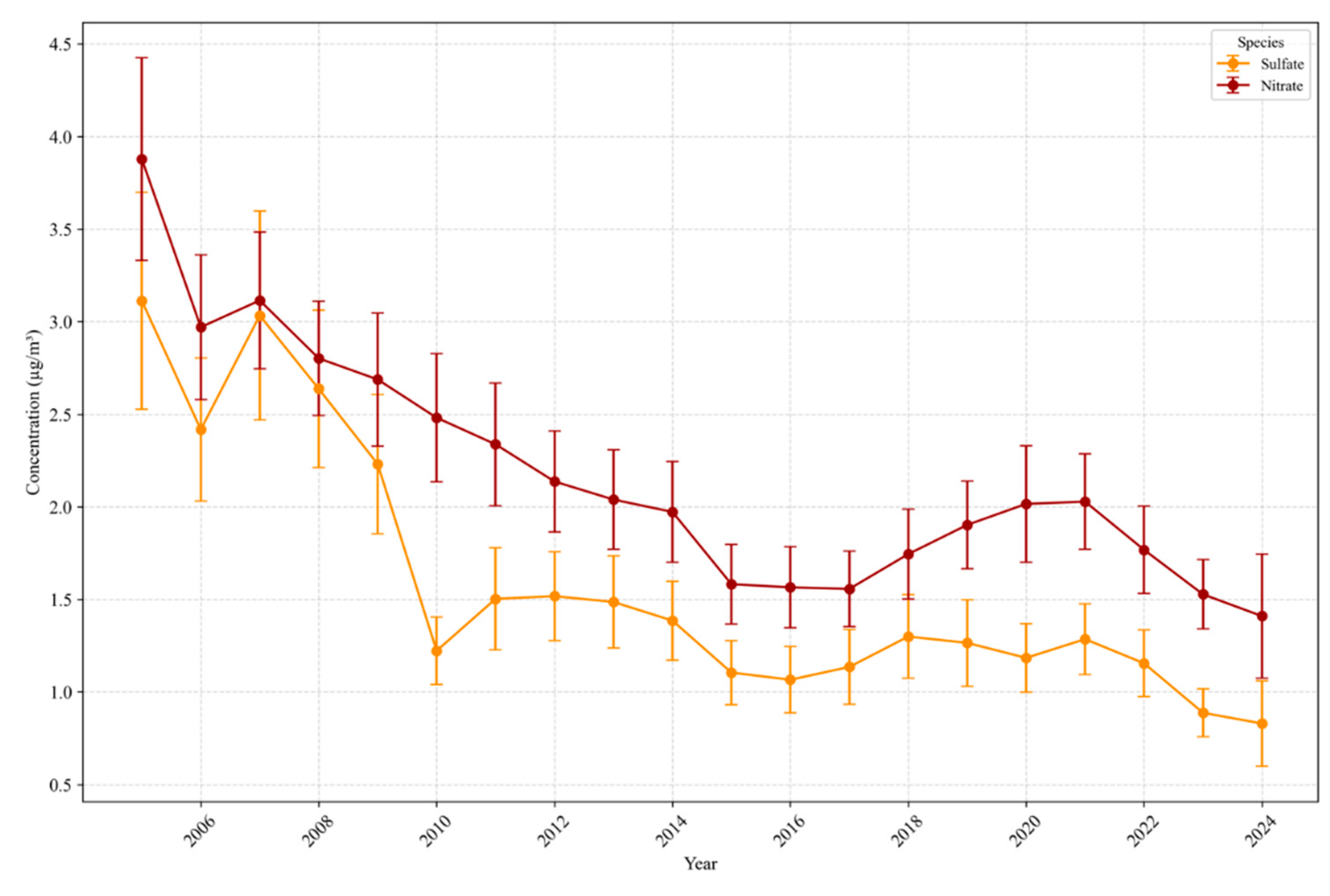

3.1.2. Inorganic Ions: Nitrate and Sulfate

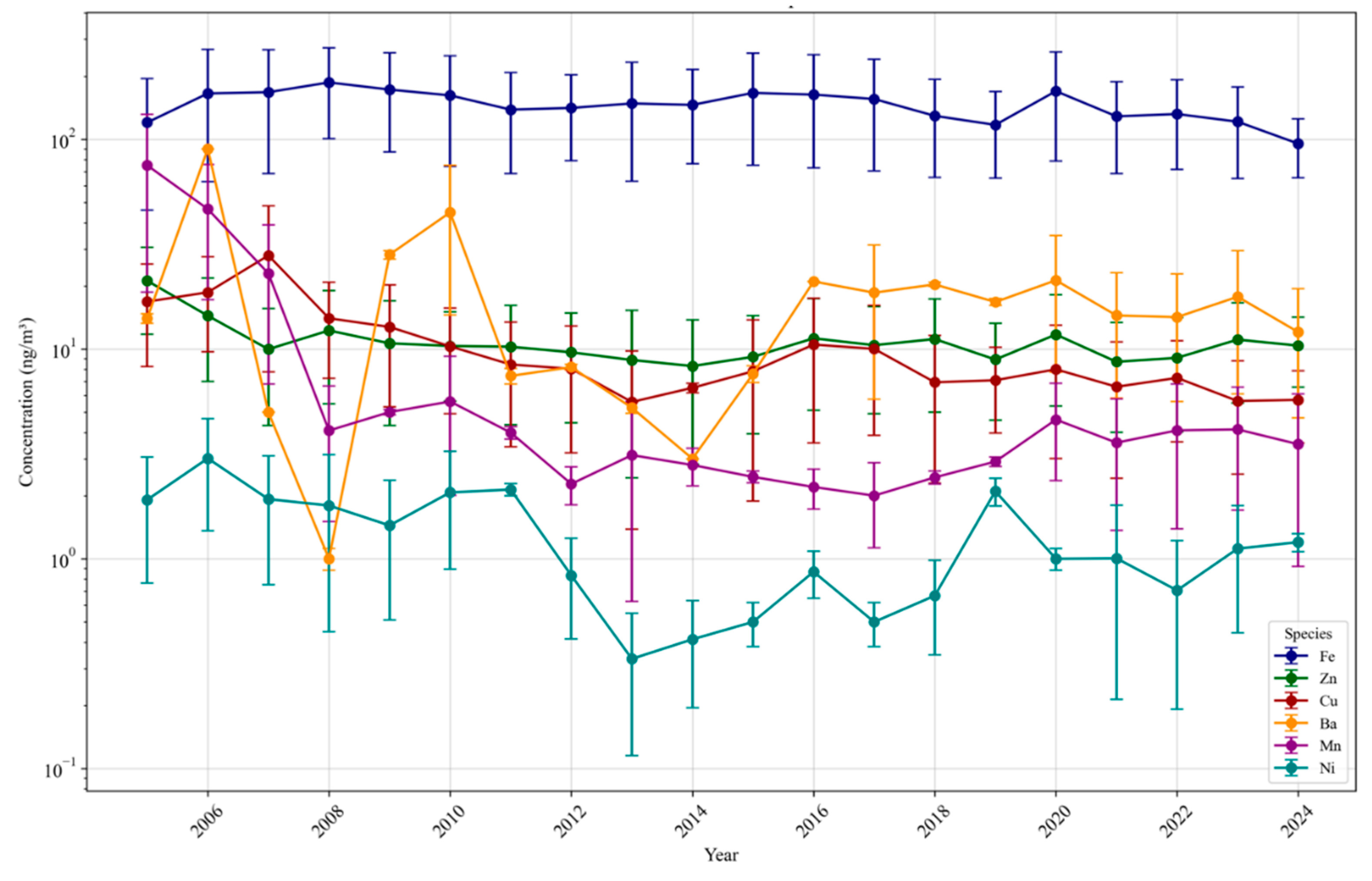

3.1.3. Trace Elements and Metals

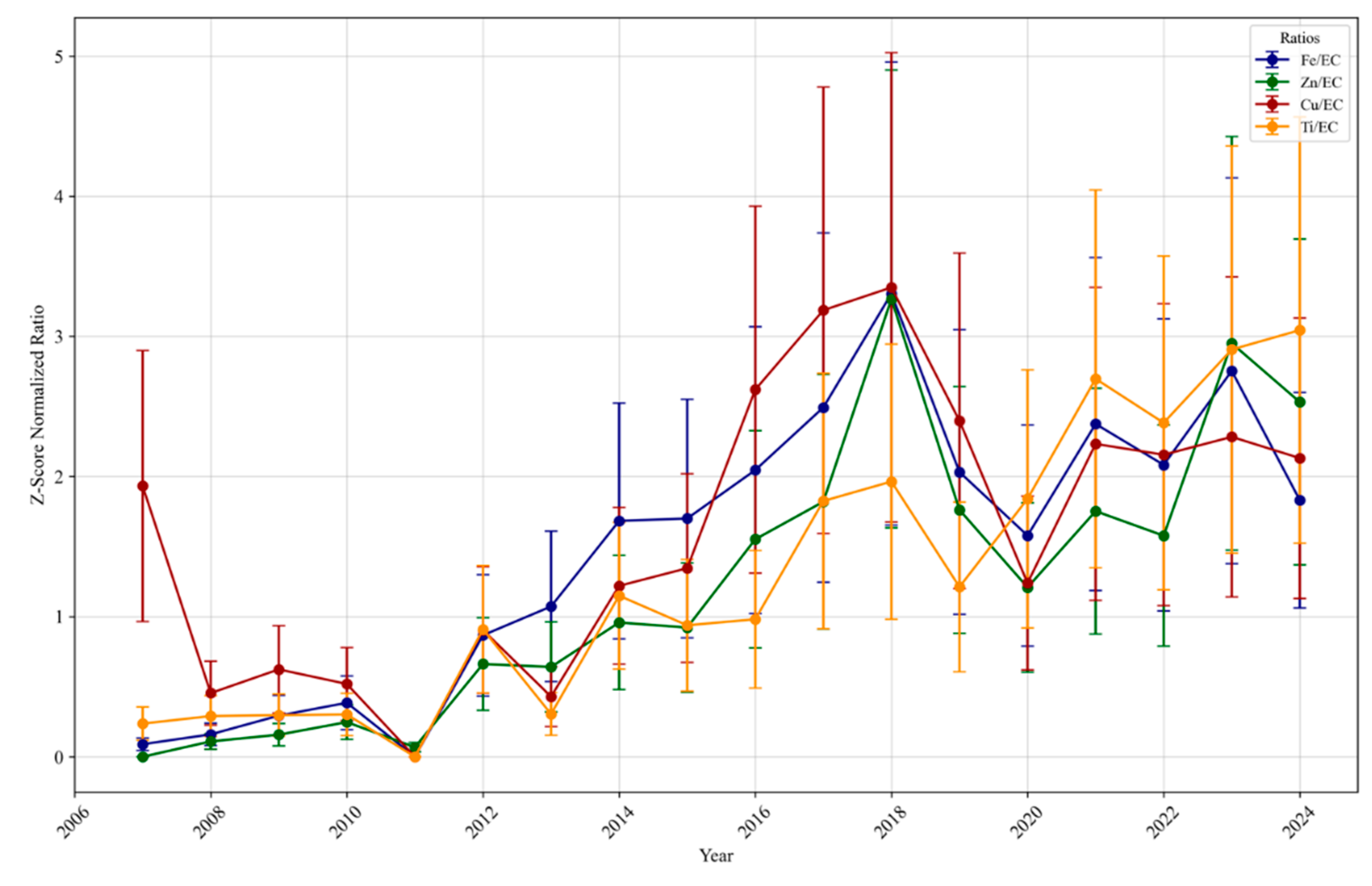

3.1.4. Long-Term Trends of the Ratio of Trace Elements and Metals to Elemental Carbon

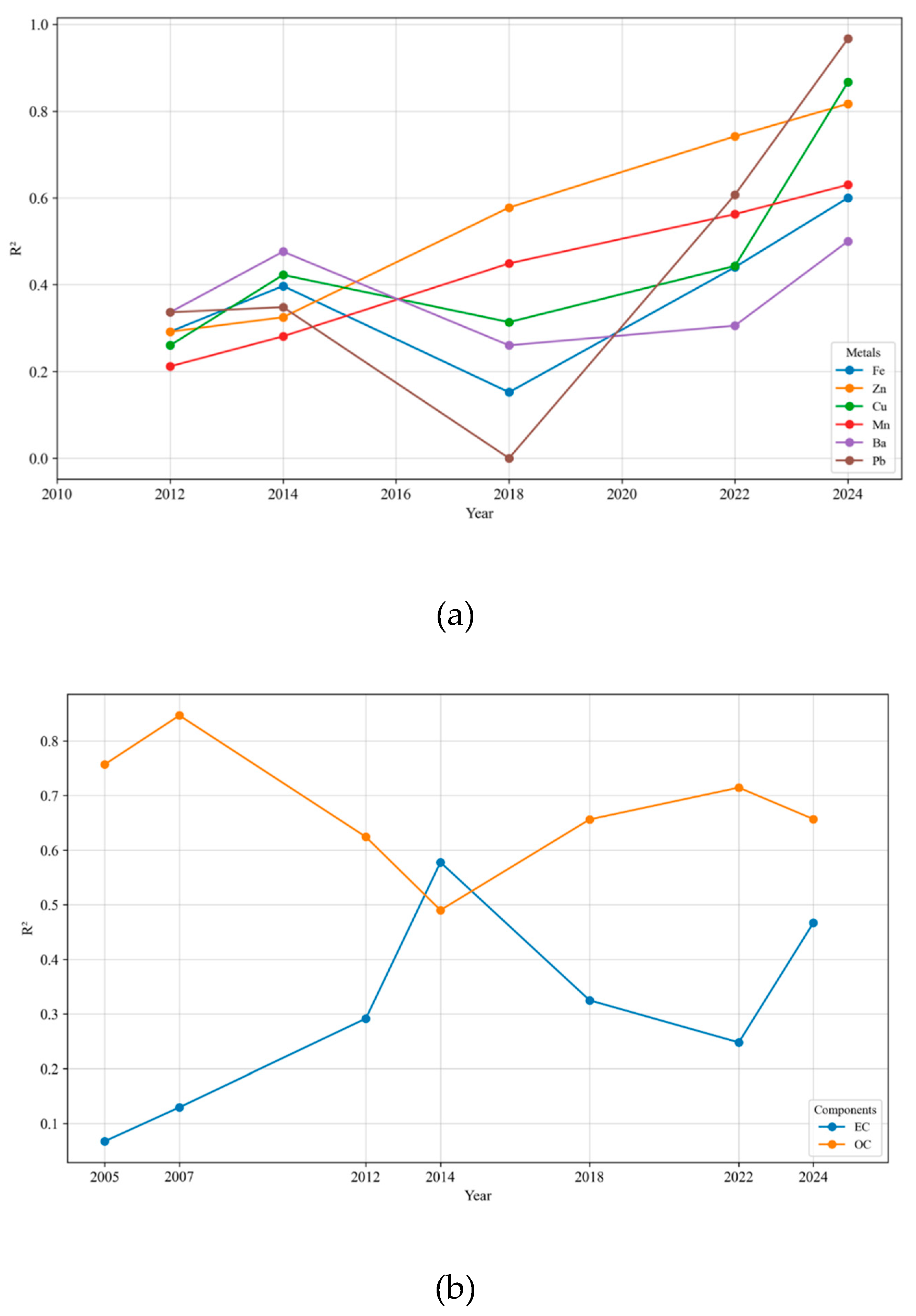

3.2. Trends in DTT Activity and Correlations with Species

3.2.1. Long-Term Trends of Oxidative Potential of PM2.5

3.2.2. Correlations of Species with PM2.5 DTT Activity

4. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2010;121:2331–78. [CrossRef]

- Pope CA, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association 2006;56:709–42. [CrossRef]

- Becker S, Soukup JM. Coarse (PM2.5-10), fine (PM2.5), and ultrafine air pollution particles induce/increase immune costimulatory receptors on human blood-derived monocytes but not on alveolar macrophages. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health - Part A 2003;66:847–59. [CrossRef]

- Sioutas C, Delfino RJ, Singh M. Exposure assessment for atmospheric Ultrafine Particles (UFPs) and implications in epidemiologic research. Environmental Health Perspectives 2005;113:947–55. [CrossRef]

- Tohidi R, Altuwayjiri A, Sioutas C. Investigation of organic carbon profiles and sources of coarse PM in Los Angeles. Environmental Pollution 2022;314:120264. [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide: executive summary 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034433 (accessed November 29, 2024).

- Aghaei Y, Sajadi B, Ahmadi G. The effect of the mucus layer and the inhaled air conditions on the droplets fate in the human nasal cavity: A numerical study. Journal of Aerosol Science 2023;171:113260. [CrossRef]

- Willers SM, Eriksson C, Gidhagen L, Nilsson ME, Pershagen G, Bellander T. Fine and coarse particulate air pollution in relation to respiratory health in Sweden. European Respiratory Journal 2013;42:924–34. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Liu L, Zhang L, Yu C, Wang X, Shi Z, et al. Assessing short-term impacts of PM2.5 constituents on cardiorespiratory hospitalizations: Multi-city evidence from China. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2022;240:113912. [CrossRef]

- Kreyling WG, Semmler-Behnke M, Möller W. Ultrafine particle-lung interactions: does size matter? J Aerosol Med 2006;19:74–83. [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster G. Pulmonary effects of inhaled ultrafine particles. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2000;74:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster G, Oberdörster E, Oberdörster J. Nanotoxicology: an emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environmental Health Perspectives 2005;113:823–39. [CrossRef]

- Burnett R, Chen H, Szyszkowicz M, Fann N, Hubbell B, Pope CA, et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:9592. [CrossRef]

- Crouse DL, Peters PA, Donkelaar A van, Goldberg MS, Villeneuve PJ, Brion O, et al. Risk of nonaccidental and cardiovascular mortality in relation to long-term exposure to low concentrations of fine particulate matter: A canadian national-level cohort study. Environmental Health Perspectives 2012;120:708–14. [CrossRef]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Beckerman BS, Turner MC, Krewski D, Thurston G, et al. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in California. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2013;188:593–9. [CrossRef]

- Künzli N, Jerrett M, Mack WJ, Beckerman B, LaBree L, Gilliland F, et al. Ambient air pollution and atherosclerosis in Los Angeles. Environmental Health Perspectives 2005;113:201–6. [CrossRef]

- Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Journal of the American Medical Association 2002;287:1132–41. [CrossRef]

- Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Rappaport EB, Thomas DC, Avol E, Gauderman WJ, et al. The effects of ambient air pollution on school absenteeism due to respiratory illnesses. Epidemiology 2001;12:43–54. [CrossRef]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Pope CA, Krewski D, Newbold KB, et al. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology 2005;16:727–36. [CrossRef]

- McConnell R, Berhane K, Gilliland F, London SJ, Islam T, Gauderman WJ, et al. Asthma in exercising children exposed to ozone: a cohort study. Lancet 2002;359:386–91. [CrossRef]

- CARB. Almanac of Emissions & Air Quality | California Air Resources Board 2013. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/almanac-emissions-air-quality (accessed December 13, 2024).

- Hasheminassab S, Daher N, Ostro BD, Sioutas C. Long-term source apportionment of ambient fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) in the Los Angeles Basin: A focus on emissions reduction from vehicular sources. Environmental Pollution 2014;193:54–64. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd AC, Cackette TA. Diesel Engines: Environmental Impact and Control. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2001;51:809–47. [CrossRef]

- Lurmann F, Avol E, Gilliland F. Emissions reduction policies and recent trends in Southern California’s ambient air quality. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association 2015;65:324–35. [CrossRef]

- Altuwayjiri A, Pirhadi M, Taghvaee S, Sioutas C. Long-Term trends in the contribution of PM2.5sources to organic carbon (OC) in the Los Angeles basin and the effect of PM emission regulations. Faraday Discussions 2021;226:74–99. [CrossRef]

- Badami MM, Tohidi R, Sioutas C. Los Angeles Basin’s air quality transformation: A long-term investigation on the impacts of PM regulations on the trends of ultrafine particles and co-pollutants. Journal of Aerosol Science 2024;176:106316. [CrossRef]

- Cheung K, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C. Historical trends in the mass and chemical species concentrations of coarse particulate matter in the Los Angeles basin and relation to sources and air quality regulations. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association 2012;62:541–56. [CrossRef]

- Suh HH, Bahadori T, Vallarino J, Spengler JD. Criteria air pollutants and toxic air-pollutants. Environmental Health Perspectives 2000;108:625–33. [CrossRef]

- CARB. Low-Emission Vehicle Program | California Air Resources Board 2003. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/low-emission-vehicle-program/about (accessed November 30, 2024).

- Singh S, Kulshrestha MJ, Rani N, Kumar K, Sharma C, Aswal DK. An Overview of Vehicular Emission Standards. MAPAN 2023;38:241–63. [CrossRef]

- Warneke C, Gouw JAD, Holloway JS, Peischl J, Ryerson TB, Atlas E, et al. Multiyear trends in volatile organic compounds in Los Angeles, California: Five decades of decreasing emissions. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres 2012;117:D00V17. [CrossRef]

- CARB. AB 32 Climate Change Scoping Plan | California Air Resources Board 2023. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/ab-32-climate-change-scoping-plan (accessed November 30, 2024).

- Goodchild A, Mohan K. The clean trucks program: Evaluation of policy impacts on marine terminal operations. Maritime Economics and Logistics 2008;10:393–408. [CrossRef]

- Haveman J, Thornberg C. Clean Trucks Program-3 2008.

- Lee G, You SI, Ritchie SG, Saphores JD, Jayakrishnan R, Ogunseitan O. Assessing air quality and health benefits of the Clean Truck Program in the Alameda corridor, CA. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2012;46:1177–93. [CrossRef]

- Andress D, Nguyen TD, Das S. Low-carbon fuel standard-Status and analytic issues. Energy Policy 2010;38:580–91. [CrossRef]

- CARB. Low Carbon Fuel Standard | California Air Resources Board 2013. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/low-carbon-fuel-standard (accessed November 29, 2024).

- Gani S, Chambliss SE, Messier KP, Lunden MM, Apte JS. Spatiotemporal profiles of ultrafine particles differ from other traffic-related air pollutants: lessons from long-term measurements at fixed sites and mobile monitoring. Environmental Science: Atmospheres 2021;1:558–68. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Pirjola L, Ketzel M, Harrison RM. Nanoparticle emissions from 11 non-vehicle exhaust sources – A review. Atmospheric Environment 2013;67:252–77. [CrossRef]

- Adamson IYR, Prieditis H, Hedgecock C, Vincent R. Zinc is the toxic factor in the lung response to an atmospheric particulate sample. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2000;166:111–9. [CrossRef]

- Bello D, Hsieh SF, Schmidt D, Rogers E. Nanomaterials properties vs. biological oxidative damage: Implications for toxicity screening and exposure assessment. Nanotoxicology 2009;3:249–61. [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri M, Øvrevik J, Holme JA, Perrone MG, Bolzacchini E, Schwarze PE, et al. Differences in cytotoxicity versus pro-inflammatory potency of different PM fractions in human epithelial lung cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2010;24:29–39. [CrossRef]

- Niu X, Wang Y, Chuang HC, Shen Z, Sun J, Cao J, et al. Real-time chemical composition of ambient fine aerosols and related cytotoxic effects in human lung epithelial cells in an urban area. Environmental Research 2022;209. [CrossRef]

- Shuster-Meiseles T, Shafer MM, Heo J, Pardo M, Antkiewicz DS, Schauer JJ, et al. ROS-generating/ARE-activating capacity of metals in roadway particulate matter deposited in urban environment. Environmental Research 2016;146:252–62. [CrossRef]

- Verma V, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C. Contribution of transition metals in the reactive oxygen species activity of PM emissions from retrofitted heavy-duty vehicles. Atmospheric Environment 2010;44:5165–73. [CrossRef]

- Bates JT, Fang T, Verma V, Zeng L, Weber RJ, Tolbert PE, et al. Review of Acellular Assays of Ambient Particulate Matter Oxidative Potential: Methods and Relationships with Composition, Sources, and Health Effects. Environmental Science and Technology 2019;53:4003–19. [CrossRef]

- Kelly FJ, Fussell JC. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmospheric Environment 2012;60:504–26. [CrossRef]

- Alramzi Y, Aghaei Y, Badami MM, Aldekheel M, Tohidi R, Sioutas C. Investigating Urban Emission and Lung-Deposited Surface Area Sources and Their Diurnal Trends in Fine and Ultrafine Pm in Los Angeles 2024.

- Ayres JG, Borm P, Cassee FR, Castranova V, Donaldson K, Ghio A, et al. Evaluating the toxicity of airborne particulate matter and nanoparticles by measuring oxidative stress potential - A workshop report and consensus statement. Inhalation Toxicology 2008;20:75–99. [CrossRef]

- Miller MR, Shaw CA, Langrish JP. From particles to patients: oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Future Cardiol 2012;8:577–602. [CrossRef]

- Gurgueira SA, Lawrence J, Coull B, Murthy GGK, González-Flecha B. Rapid increases in the steady-state concentration of reactive oxygen species in the lungs and heart after particulate air pollution inhalation. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:749–55. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Sioutas C, Cho A, Schmitz D, Misra C, Sempf J, et al. Ultrafine particulate pollutants induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. Environmental Health Perspectives 2003;111:455–60. [CrossRef]

- Charrier JG, Anastasio C. On dithiothreitol (DTT) as a measure of oxidative potential for ambient particles: Evidence for the importance of soluble transition metals. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2012;12:9321–33. [CrossRef]

- Cho AK, Sioutas C, Miguel AH, Kumagai Y, Froines JR. Redox activity of airborne particulate matter (PM) at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ Res 2005;99:40–7. [CrossRef]

- Fang T, Verma V, Guo H, King LE, Edgerton ES, Weber RJ. A semi-automated system for quantifying the oxidative potential of ambient particles in aqueous extracts using the dithiothreitol (DTT) assay: Results from the Southeastern Center for Air Pollution and Epidemiology (SCAPE). Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2015;8:471–82. [CrossRef]

- Gao D, Fang T, Verma V, Zeng L, Weber RJ. A method for measuring total aerosol oxidative potential (OP) with the dithiothreitol (DTT) assay and comparisons between an urban and roadside site of water-soluble and total OP. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2017;10:2821–35. [CrossRef]

- Fang T, Verma V, Bates JT, Abrams J, Klein M, Strickland JM, et al. Oxidative potential of ambient water-soluble PM2.5 in the southeastern United States: Contrasts in sources and health associations between ascorbic acid (AA) and dithiothreitol (DTT) assays. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2016;16:3865–79. [CrossRef]

- Verma V, Fang T, Xu L, Peltier RE, Russell AG, Ng NL, et al. Organic aerosols associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by water-soluble PM2.5. Environmental Science and Technology 2015;49:4646–56. [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi F, Wang D, Hasheminassab S, Verma V, Schauer JJ, Shafer MM, et al. Oxidative potential of on-road fine particulate matter (PM2.5) measured on major freeways of Los Angeles, CA, and a 10-year comparison with earlier roadside studies. Atmospheric Environment 2017;148:102–14. [CrossRef]

- US EPA O. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter 2015. https://www.epa.gov/isa/integrated-science-assessment-isa-particulate-matter (accessed November 30, 2024).

- Badami MM, Tohidi R, Aldekheel M, Farahani VJ, Verma V, Sioutas C. Design, optimization, and evaluation of a wet electrostatic precipitator (ESP) for aerosol collection. Atmospheric Environment 2023;308:119858. [CrossRef]

- Farahani VJ, Altuwayjiri A, Pirhadi M, Verma V, Ruprecht AA, Diapouli E, et al. The oxidative potential of particulate matter (PM) in different regions around the world and its relation to air pollution sources. Environmental Science: Atmospheres 2022;2:1076–86. [CrossRef]

- Hu S, Polidori A, Arhami M, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Cho A, et al. Redox activity and chemical speciation of size fractioned PM in the communities of the Los Angeles-Long Beach harbor. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2008;8:6439–51. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Wang M, Bramble LA, Schmitz DA, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C, et al. The adjuvant effect of ambient particulate matter is closely reflected by the particulate oxidant potential. Environmental Health Perspectives 2009;117:1116–23. [CrossRef]

- Ntziachristos L, Froines JR, Cho AK, Sioutas C. Relationship between redox activity and chemical speciation of size-fractionated particulate matter. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 2007;4. [CrossRef]

- Saffari A, Daher N, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C. Seasonal and spatial variation in dithiothreitol (DTT) activity of quasi-ultrafine particles in the Los Angeles Basin and its association with chemical species. Journal of Environmental Science and Health - Part A Toxic/Hazardous Substances and Environmental Engineering 2014;49:441–51. [CrossRef]

- Saffari A, Hasheminassab S, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Chatila TA, Sioutas C. Nighttime aqueous-phase secondary organic aerosols in Los Angeles and its implication for fine particulate matter composition and oxidative potential. Atmospheric Environment 2016;133:112–22. [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi F, Hasheminassab S, Wang D, Schauer JJ, Shafer MM, Delfino RJ, et al. The relative importance of tailpipe and non-tailpipe emissions on the oxidative potential of ambient particles in Los Angeles, CA. Faraday Discussions 2016;189:361–80. [CrossRef]

- Verma V, Polidori A, Schauer JJ, Shafer MM, Cassee FR, Sioutas C. Physicochemical and toxicological profiles of particulate matter in Los Angeles during the October 2007 Southern California wildfires. Environmental Science and Technology 2009;43:954–60. [CrossRef]

- Verma V, Pakbin P, Cheung KL, Cho AK, Schauer JJ, Shafer MM, et al. Physicochemical and oxidative characteristics of semi-volatile components of quasi-ultrafine particles in an urban atmosphere. Atmospheric Environment 2011;45:1025–33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Staimer N, Gillen DL, Tjoa T, Schauer JJ, Shafer MM, et al. Associations of oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers with chemically-characterized air pollutant exposures in an elderly cohort. Environmental Research 2016;150:306–19. [CrossRef]

- Yao K, Wang S, Zheng H, Zhang X, Wang Y, Chi Z, et al. Oxidative potential and source apportionment of size-resolved particles from indoor environments: Dithiothreitol (DTT) consumption and ROS production. Atmospheric Environment 2023;313:120060. [CrossRef]

- EPA. EPA: Air Quality System (AQS) API 2024. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Air%20quality%20System%20(AQS)%20API&author=US%20EPA&publication_year=2023 (accessed December 15, 2024).

- Misra C, Singh M, Shen S, Sioutas C, Hall PM. Development and evaluation of a personal cascade impactor sampler (PCIS). Journal of Aerosol Science 2002;33:1027–47. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Misra C, Sioutas C. Field evaluation of a personal cascade impactor sampler (PCIS). Atmospheric Environment 2003;37:4781–93. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai Y, Koide S, Taguchi K, Endo A, Nakai Y, Yoshikawa T, et al. Oxidation of proximal protein sulfhydryls by phenanthraquinone, a component of diesel exhaust particles. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2002;15:483–9. [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi S, Zhang Q, Pilla F, Basu B, Basu AS. Effects of West Coast forest fire emissions on atmospheric environment: A coupled satellite and ground-based assessment 2020. [CrossRef]

- Limbeck A, Kulmala M, Puxbaum H. Secondary organic aerosol formation in the atmosphere via heterogeneous reaction of gaseous isoprene on acidic particles. Geophysical Research Letters 2003;30. [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Y, Aldekheel M, Tohidi R, Badami MM, Farahani VJ, Sioutas C. Development and performance evaluation of online monitors for near real-time measurement of total and water-soluble organic carbon in fine and coarse ambient PM. Atmospheric Environment 2024;319:120316. [CrossRef]

- Graham LA, Belisle SL, Rieger P. Nitrous oxide emissions from light duty vehicles. Atmospheric Environment 2009;43:2031–44. [CrossRef]

- Soleimanian E, Mousavi A, Taghvaee S, Shafer MM, Sioutas C. Impact of secondary and primary particulate matter (PM) sources on the enhanced light absorption by brown carbon (BrC) particles in central Los Angeles. Science of The Total Environment 2020;705:135902. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard CL, Shaw SL, Edgerton ES, Schwab JJ. Ambient PM2.5 organic and elemental carbon in New York City: Changing source contributions during a decade of large emission reductions. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2021;71:995–1012. [CrossRef]

- Murphy BN, Sonntag D, Seltzer KM, Pye HOT, Allen C, Murray E, et al. Reactive organic carbon air emissions from mobile sources in the United States. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2023;23:13469–83. [CrossRef]

- Farahani VJ, Soleimanian E, Pirhadi M, Sioutas C. Long-term trends in concentrations and sources of PM2.5–bound metals and elements in central Los Angeles. Atmospheric Environment 2021;253. [CrossRef]

- Panko JM, Hitchcock KM, Fuller GW, Green D. Evaluation of Tire Wear Contribution to PM2.5 in Urban Environments. Atmosphere 2019;10:99. [CrossRef]

- Badami MM, Tohidi R, Jalali Farahani V, Sioutas C. Size-segregated source identification of water-soluble and water-insoluble metals and trace elements of coarse and fine PM in central Los Angeles. Atmospheric Environment 2023;310:119984. [CrossRef]

- CARB. Advanced Clean Trucks | California Air Resources Board 2019. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/advanced-clean-trucks (accessed November 29, 2024).

- Fujitani Y, Furuyama A, Tanabe K, Hirano S. Comparison of Oxidative Abilities of PM2.5 Collected at Traffic and Residential Sites in Japan. Contribution of Transition Metals and Primary and Secondary Aerosols. Aerosol Air Qual Res 2017;17:574–87. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Ahmed CMS, Canchola A, Chen JY, Lin Y-H. Use of Dithiothreitol Assay to Evaluate the Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Aerosols. Atmosphere 2019;10:571. [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Y, Badami MM, Tohidi R, Subramanian PSG, Boffi R, Borgini A, et al. The Impact of Russia-Ukraine geopolitical conflict on the air quality and toxicological properties of ambient PM2.5 in Milan, Italy. Sci Rep 2024;14:5996. [CrossRef]

- Campbell SJ, Wolfer K, Utinger B, Westwood J, Zhang Z-H, Bukowiecki N, et al. Atmospheric conditions and composition that influence PM2.5 oxidative potential in Beijing, China. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2021;21:5549–73. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).