1. Introduction

The Guajira Offshore Basin, located in the Caribbean Sea north of Colombia, represents a promising but underexplored frontier in offshore hydrocarbon exploration [

1]. Despite significant interest from national and international energy agencies, the basin’s complex geology, deep-water conditions, and high logistical costs have limited detailed geomorphological mapping and early-stage prospectivity analysis [

2]. Traditional marine campaigns relying on seismic, gravimetric, and multibeam data collection are both time-consuming and expensive, often requiring specialized vessels and extensive post-processing. As a result, new approaches are needed to enable early characterization of potential structural features with minimal physical intervention [

3].

In parallel, recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing have opened new pathways for geoscientific data acquisition, processing, and interpretation [

4]. AI techniques, such as convolutional neural networks [

5] (CNNs) and generative algorithms [

6], have demonstrated effectiveness in extracting geomorphological features from synthetic and real-world geospatial datasets, including bathymetric grids and radar altimetry. Simultaneously, quantum-inspired algorithms—particularly the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) and Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) formulations—are gaining traction for their ability to solve complex combinatorial problems with limited computational resources and under high uncertainty [

7].

This paper introduces a lightweight, simulation-based framework that integrates QAOA-driven route planning with geospatial grid-based models for offshore terrain exploration. We focus on a 1 km × 1 km segment of the Guajira Offshore region, selected from publicly available oceanic datasets, to simulate an autonomous mapping mission analogous to those performed by unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). The grid-based domain is encoded into a QUBO formulation that represents feasible navigation paths constrained by battery life, current directions, and seabed topography.

Given the high cost and difficulty of deploying real missions in offshore Colombia, this study adopts a proof-by-simulation strategy using real topographic analogs and computational simulations. This approach allows testing of a quantum-classical hybrid optimization pipeline under conditions similar to those faced in actual offshore missions. By combining QUBO encoding, QAOA solvers, and AI-supported prioritization of exploration targets, the model demonstrates how route planning can be adapted to prioritize geological significance while respecting resource limitations.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the theoretical background on QUBO and QAOA in geospatial optimization.

Section 3 details the simulation domain, grid encoding, and objective functions.

Section 4 presents illustrative results from route optimization experiments.

Section 5 discusses implications for marine geoscience, and Section 6 concludes with recommendations for real-world deployment and further integration of quantum approaches in offshore exploration workflows.

2. Theoretical Foundations: QUBO and QAOA for Quantum-Assisted Geospatial Exploration

Recent advances in quantum algorithms for combinatorial optimization have enabled the development of novel methodologies to address tasks such as route planning, resource allocation, and autonomous navigation in geospatial domains [

8]. Among these, Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) models and their implementation through algorithms such as the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm

(QAOA) have emerged as leading approaches compatible with near-term quantum and hybrid classical-quantum hardware architectures [

9,

10]. In these models, Q is a symmetric matrix encoding both linear and quadratic interactions between decision variables [

11]. This representation is sufficiently flexible to model optimal paths, mapping coverage constraints, energy limitations, and geological prioritization within a unified binary decision space. Classical georeferencing problems, sampling point selection, or mission planning under resource limitations can be effectively encoded in a QUBO framework [

12].

In marine contexts such as the Guajira Offshore Basin, discretization of the seafloor into a navigable grid enables the representation of each cell or transition as a binary variable. Viable paths are modeled as chains of activated variables within the grid, subject to constraints related to vehicle endurance, subsea obstacles, or prioritized exploration targets [

1]. These conditions are integrated as quadratic penalties within the Q matrix, allowing for the resolution of both minimal coverage and multi-objective routing problems [

13].

QAOA, in turn, provides a variational quantum approach to optimization, based on a sequence of parameterized unitary operators that approximate the ground state of a quantum system encoding the QUBO objective [

14]. QAOA has demonstrated promising results under noisy conditions and in scenarios where near-optimal solutions are desirable [

15]. In navigation contexts, QAOA enables the design of adaptive trajectories that respond to uncertainties such as ocean currents, sensor anomalies, or shifting coverage priorities.

Unlike classical routing algorithms (e.g.

, Dijkstra, A*) that require full recomputation under changing conditions [

14], QAOA allows for partial reconfiguration and incorporates probabilistic insights about solution quality [

16]. This makes it particularly well suited for maritime mission planning in environments with incomplete or noisy bathymetric or spectral data.

The benefits of using QUBO/QAOA in geospatial exploration include [

17,

18]:

Compact encoding of diverse constraints and objectives in a unified matrix formulation.

Adaptability to dynamic scenarios through parametric updates.

Reduced computational complexity in large-scale, multi-constraint optimization problems.

Scalability toward real-world deployment on dedicated quantum annealers or hybrid cloud-based quantum platforms.

This theoretical foundation supports the design of our simulated experiment in the Guajira Offshore Basin, presented in the following section. There, we detail both the QUBO formulation and its solution using QAOA-based techniques over a discretized mission domain.

3. Geospatial Domain and Model Formulation

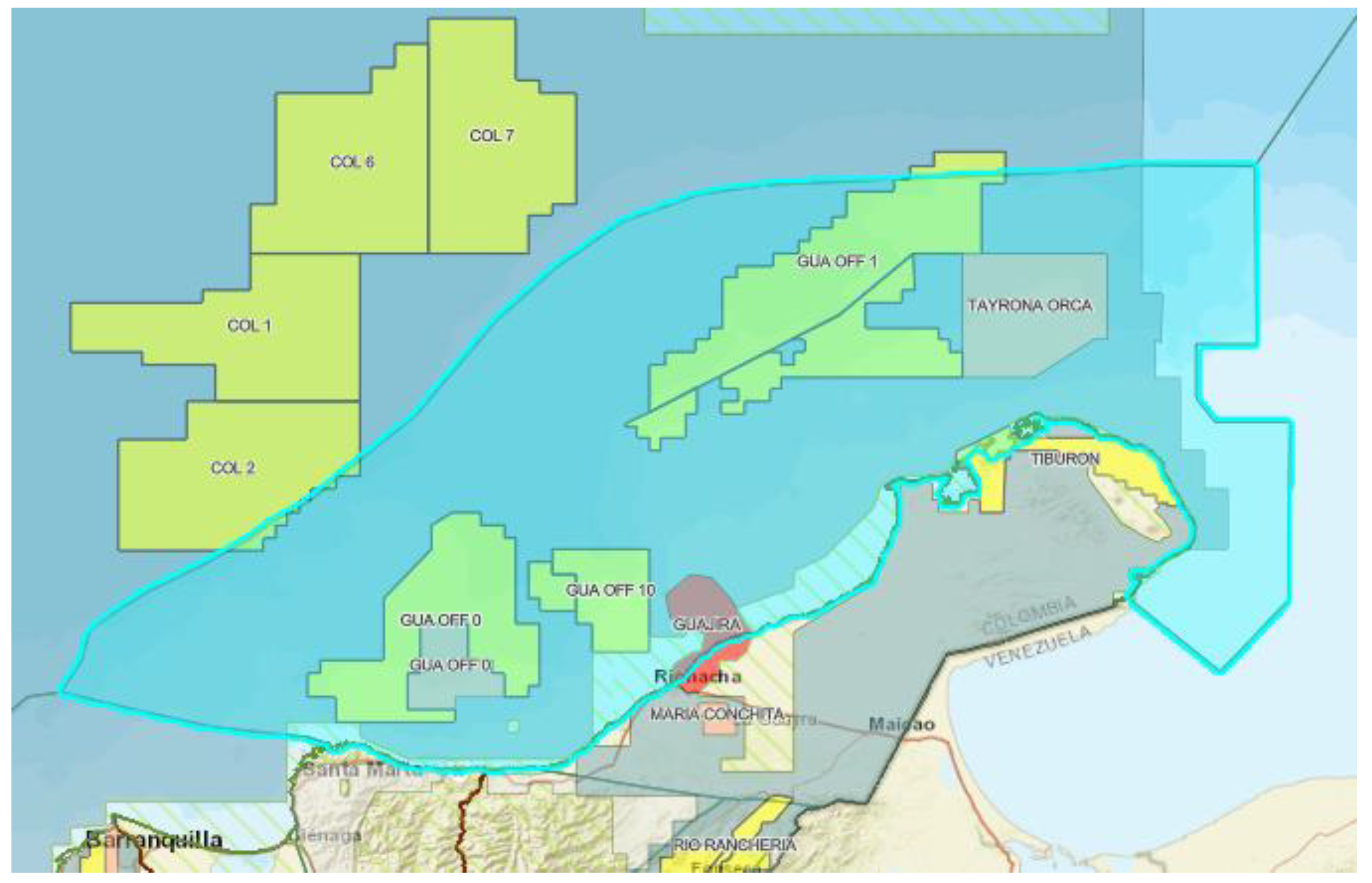

This study focuses on a simulated geospatial domain within the Guajira Offshore region (

Figure 1 ), specifically selected due to its strategic importance for future exploration and its accessibility via satellite imagery and digital elevation models. A representative area of 1 km

2 (1 km × 1 km) has been defined as the operational simulation grid. This region exhibits a relatively homogeneous bathymetry pattern and is suitable for modeling airborne or remote vehicle coverage missions.

The simulation grid is discretized into 10 × 10 square cells, each representing an area of 100 m × 100 m. This structure allows for detailed modeling of routing problems by associating each grid node with quantifiable geospatial parameters, such as seabed slope, estimated navigation cost, or hydrographic risk zones. The navigation surface is therefore treated as a weighted graph, where edges correspond to feasible movements between adjacent cells and the weights encode risk or energy metrics.

This discretization enables the problem to be expressed as a graph-based traversal optimization, where the goal is to maximize coverage under constraints such as battery consumption, obstacle avoidance, or dynamic risk exposure. The formulation uses the QUBO (Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization) model as a mathematical abstraction, allowing the integration of multiobjective criteria into a single optimization framework compatible with quantum or hybrid solvers.

To formalize the autonomous routing of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) over the discretized offshore exploration domain, we formulate the trajectory optimization as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) problem. This modeling approach allows for direct implementation within quantum-classical hybrid solvers, specifically under the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) paradigm.

Let the 100 m2 simulation domain be discretized into an X square grid, where each cell represents a potential location for UAV traversal. Define the binary decision variable , such that if the cell is included in the route, and otherwise.

The objective is to determine a path that (i) maximizes coverage over high-priority geospatial cells, (ii) adheres to energy and distance constraints, and (iii) minimizes trajectory discontinuities. These requirements are encoded into the following QUBO structure:

where:

Ω is the set of all cells in the grid

denotes the geological priority score for cell , based on simulated or real satellite-derived attributes.

and are penalty coefficients controlling path continuity and route length constraint enforcement, respectively.

-

represents the traversal cost or distance associated with visiting cell .

is the maximum allowed UAV flight range, determined by battery and mission-specific limitations.

The first term rewards exploration of geologically relevant regions. The second term penalizes disconnected paths by discouraging simultaneous activation of distant cells. The third term imposes a soft constraint to ensure that the total route cost remains within the UAV’s operational threshold.

This formulation is directly translated into a QUBO matrix QQQ, where the optimization problem takes the canonical form:

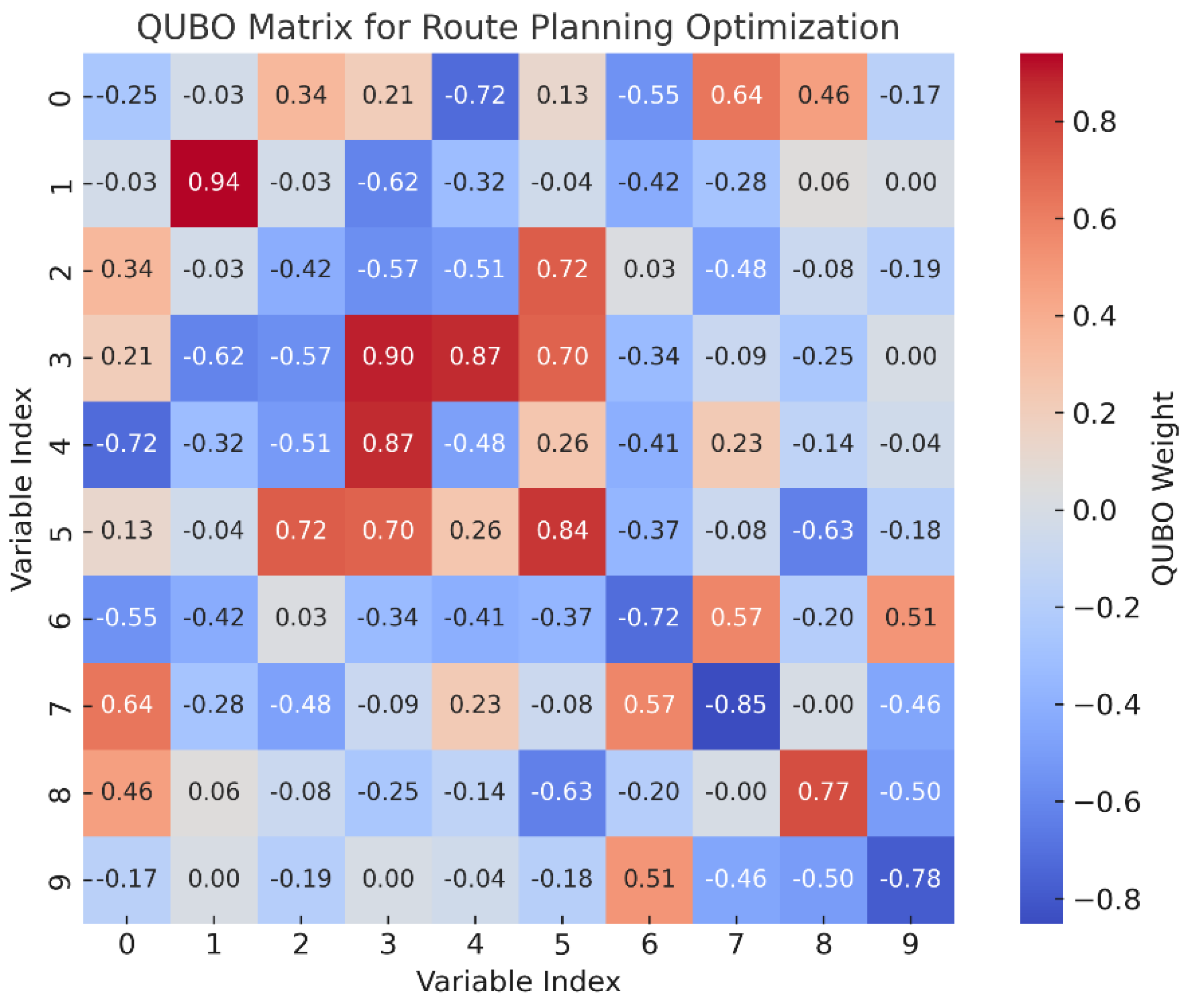

Figure 2 illustrates a representative QUBO matrix instance, where each entry

encodes the interaction weight between binary variables

and

, derived from the combination of priority weights, adjacency constraints, and distance penalties. Each element

represents either a unary bias or a binary interaction between variables (cells), representing coverage reward, path continuity, or energy constraints.

This QUBO instance is subsequently embedded into a QAOA routine. The algorithm operates in alternating layers of quantum evolution and classical optimization to find an approximate solution that minimizes the energy landscape encoded by Q. The QAOA implementation enables adaptive tuning over noisy quantum backends or simulators and is particularly well-suited to constrained routing problems in dynamic or partially known environments. The route planning task is formulated as a combinatorial problem aiming to maximize the coverage of priority zones under constraints related to energy, visibility, and connectivity. A directed graph is constructed, where the nodes represent georeferenced points of interest and the edges E encode transition costs (distance, slope, forest density).

3.4. QAOA-Based Solving and Interpretation

The QUBO model is solved using a QAOA implementation within a quantum simulation environment (e.g., Qiskit or PennyLane). This hybrid approach combines parameterized quantum unitary operators with classical optimization loops to approximate near-optimal solutions. Multiple parameters—such as ansatz depth, objective function performance, and fidelity metrics—are evaluated to assess solution quality.

The optimized routes are compared with classical pathfinding algorithms (e.g., Dijkstra, A*) to quantify the relative improvement in geographic coverage, energy efficiency, and the number of detected geological structures. The resulting routes are visualized in a GIS environment, integrating geological information and UAV-simulated imagery to ensure spatial coherence and scientific relevance.

This section lays the groundwork for the implementation of the optimization algorithm described in

Section 4, where mission planning strategies for UAV or AUV exploration in offshore regions are validated under the QUBO/QAOA framework.

4. Case Study and Preliminary Simulation Results

This section outlines the implementation of the quantum-inspired routing algorithm described in

Section 3, using a realistic offshore scenario to evaluate UAV route planning performance. The selected testbed corresponds to the Guajira Offshore Basin in northern Colombia, a region of high strategic interest due to its complex seafloor morphology and the presence of structural traps and fault-controlled accumulations.

4.1. Study Area and Input Data

To simulate an offshore reconnaissance mission with UAVs, a 1 km2 corridor was selected within the Guajira Offshore Basin. This zone contains legacy seismic wells (e.g., Chuchupa, Ballena, Tiburón) and known geological targets of interest for early-stage hydrocarbon exploration. The area is characterized by steep bathymetric gradients and diverse sedimentary structures, making it suitable for evaluating both coverage and routing feasibility.

The spatial domain was discretized into a 10×10 grid, with each cell representing a 100 m × 100 m surface unit. A composite geospatial score was assigned to each cell based on the following three primary attributes:

Bathymetric Complexity Layer: Simulates the gradient of seafloor irregularities using noise-perturbed elevation functions.

Geological Priority Layer: Assigns higher weights to cells adjacent to known or suspected structural highs.

Environmental Risk Layer: Marks operationally hazardous areas due to sediment instability, marine currents, seabed faults, or ecological constraints.

Each attribute was simulated using analog values derived from regional geological maps, seismic records, and marine environmental studies.

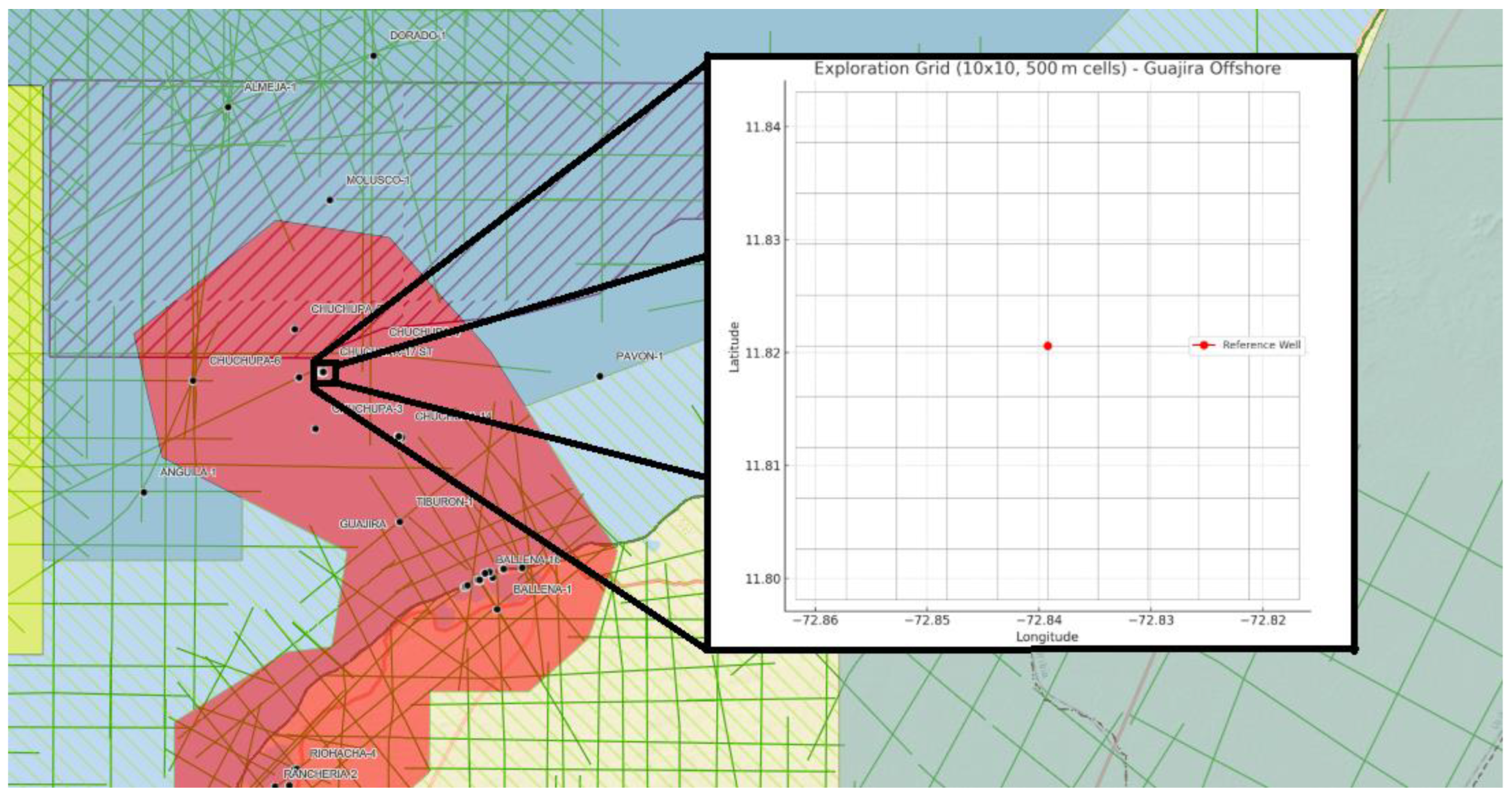

Figure 3 shows the discretized grid projected over the defined simulation zone.

Table 1 summarizes the geospatial attributes encoded per cell.

4.2. Case Definition and Simulation Parameters

To validate the proposed QUBO-based routing model in a geologically realistic context, we selected a 1 km

2 offshore exploration area near the Chuchupa-1 gas well, located in the Guajira Offshore basin (11°48′02″N, 72°50′21″W). This site is part of a region of strategic interest for Colombia’s energy transition and is characterized by both complex bathymetry and high seismic activity. The zone has previously been explored by Ecopetrol and Chevron, known for the presence of structural traps and fault-controlled accumulations (

Figure 3).

The attributes of the zone was simulated based on analog values derived from

regional geological reports, marine environmental studies, and prior offshore seismic campaigns. The QUBO model includes

penalty terms to discourage redundant paths and traversals through restricted or high-risk zones. The key simulation parameters are summarized in the following table (

Table 2).

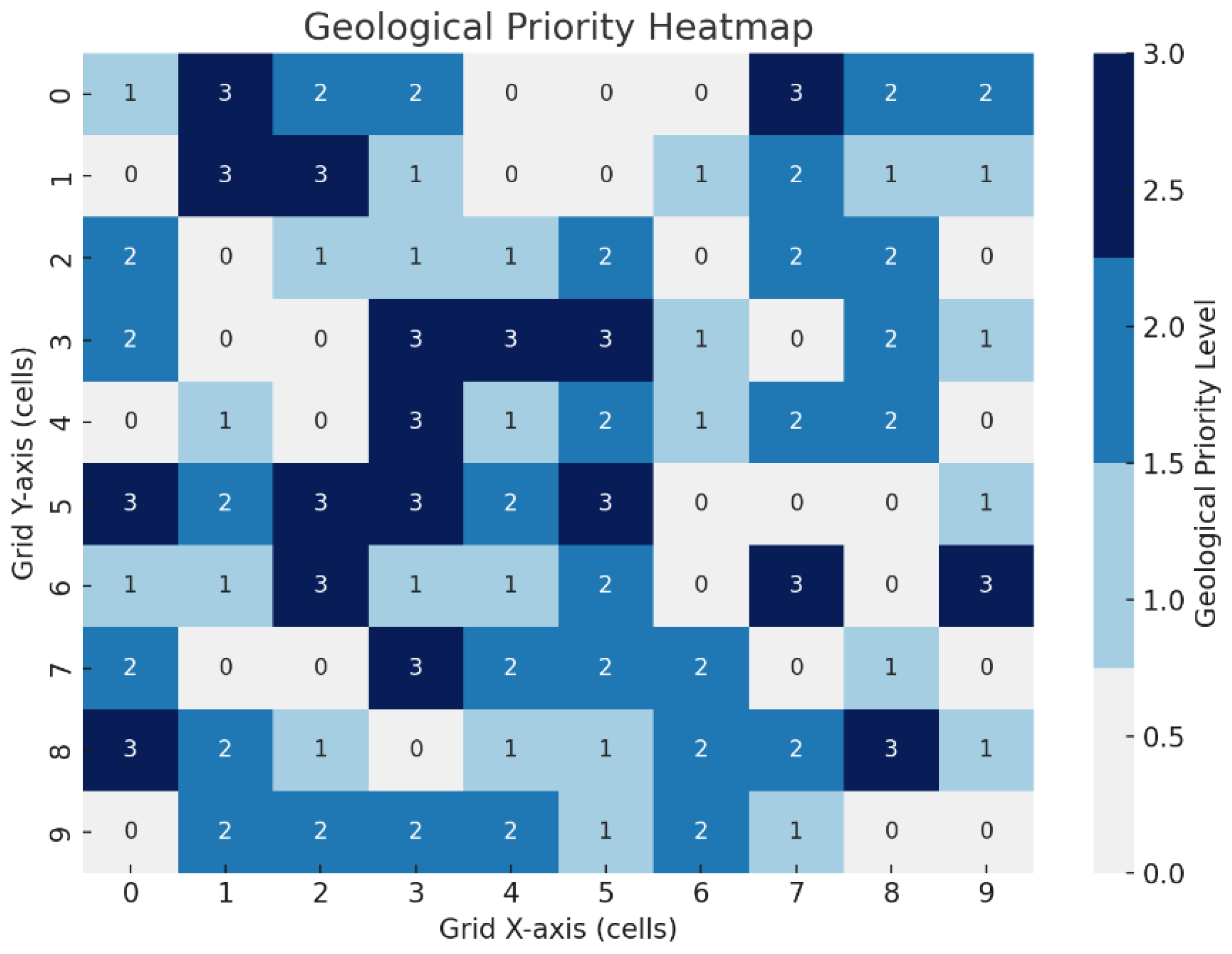

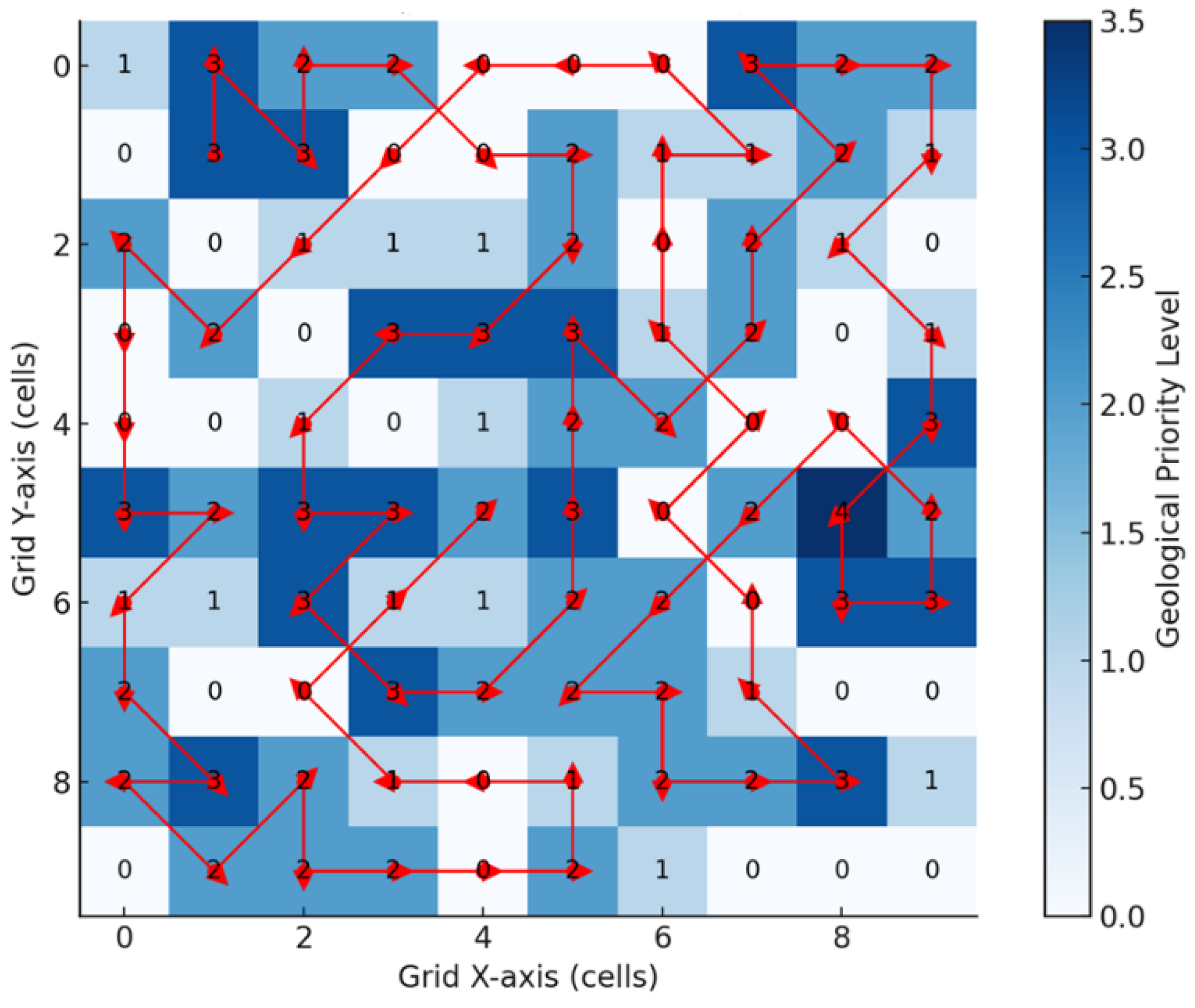

This case setup provides a controlled yet realistic basis to test the performance of the quantum-enhanced routing framework under operational constraints and terrain-based risks. The upcoming subsection presents the simulation results and visual comparison between the QAOA-based routes and classical benchmarks. A geological priority map was created using a Gaussian decay function centered on the Chuchupa-1 structure, assigning higher scores to adjacent cells.

Figure 4 displays the resulting priority heatmap, with darker tones indicating higher exploration relevance. This area holds strategic interest due to the presence of deep features such as anticlines, structural highs, salt domes, and faulted zones previously inferred from seismic data and regional geophysical maps [

19].

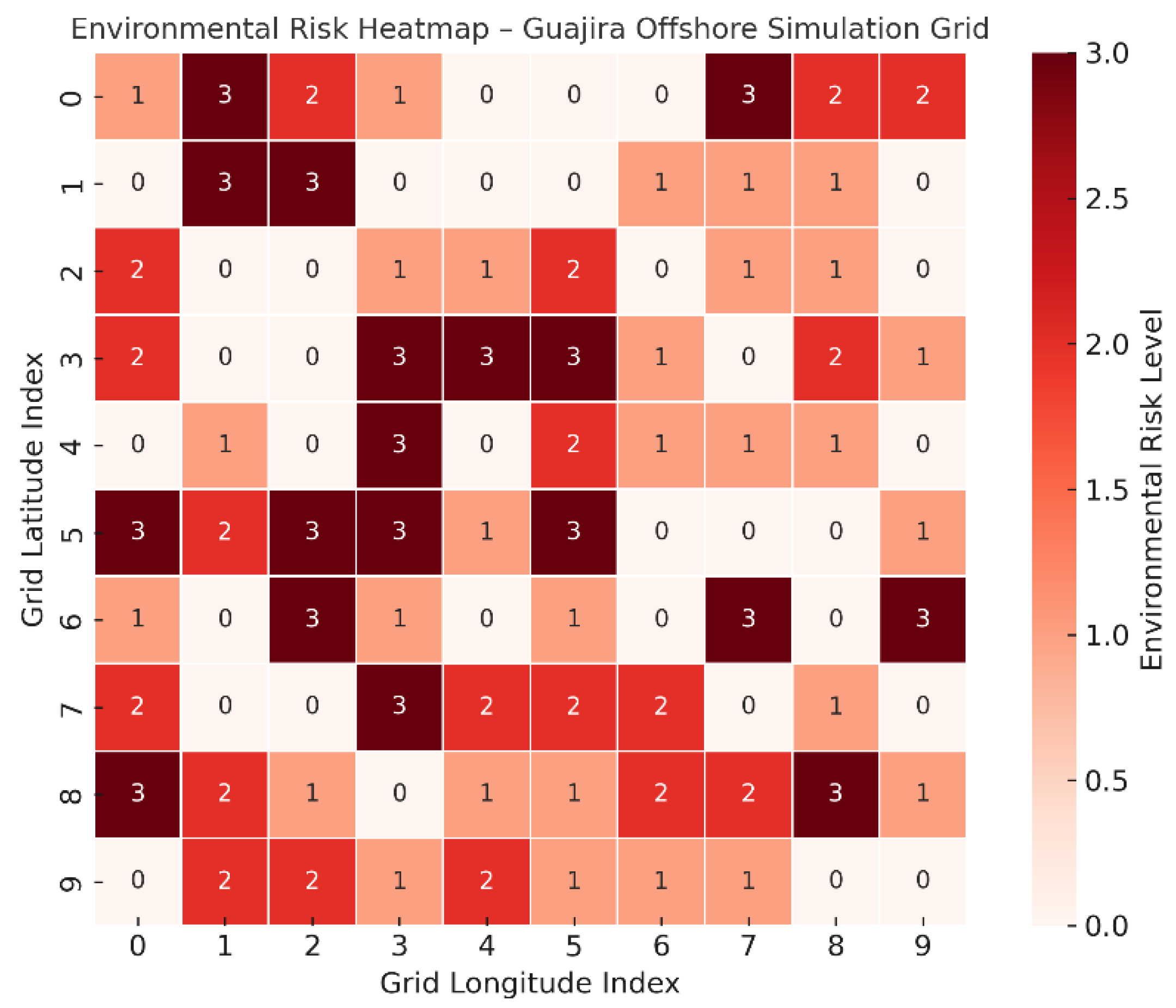

To complement this layer and incorporate environmental feasibility, a synthetic environmental risk map was generated using a probabilistic hazard model. Risk levels were categorized as follows:

Level 3 (High risk): Simulated zones exposed to intense marine currents, strong seafloor irregularities, or ecological exclusion zones (e.g., coral habitats).

Level 2 (Moderate risk): Zones near structural transitions or mild slope instability.

Level 1 (Low risk): Areas with minor operational concerns.

Level 0 (No risk): Zones considered safe for autonomous transit.

Figure 5 presents the environmental risk heatmap synthesized over the simulation grid. This layer plays a critical role in penalizing unsafe routes during the QUBO optimization process.

In offshore missions involving UAVs or autonomous marine vehicles, navigation must consider not only geological value but also environmental risks that may compromise safety, operational efficiency, or mission continuity. To simulate such real-world constraints in the Guajira Offshore testbed, a synthetic environmental risk map was constructed, using a 10×10 grid aligned with the previously defined simulation domain.

Risk levels were assigned to each cell on a four-point ordinal scale from 0 to 3, based on the presence or absence of simulated constraints including:

Level 3 (High risk): Simulated areas affected by intense marine currents, potential underwater landslides, ecological exclusion zones (e.g., coral habitats), or regions with high bathymetric irregularity.

Level 2 (Moderate risk): Transition zones near structural discontinuities or shallower zones with known sediment instability.

Level 1 (Low risk): Peripheral areas with mild environmental irregularities, possibly affected by secondary marine dynamics.

Level 0 (No risk): Navigationally safe zones based on the analog topography and literature-informed assumptions.

Figure 5 displays the resulting environmental risk heatmap. Higher-risk zones are shown in darker shades, serving as exclusion or penalty zones during QUBO formulation.

This synthetic constraint layer was used to introduce penalties in the QUBO cost function when routes passed through medium- or high-risk areas. As a result, the quantum-inspired model was forced to generate safer and more energy-efficient paths, improving mission feasibility under operational uncertainty. This layer also allowed testing the sensitivity and adaptability of QAOA-based solvers to real-time risk reconfiguration scenarios, which are common in marine exploration contexts.

To complement the geological priority analysis and enable adaptive routing under operational constraints, a simulated environmental risk map was developed over the defined Guajira Offshore grid. This layer integrates synthetic estimations of environmental hazards that may affect the feasibility and safety of autonomous navigation in marine settings. The simulated risk profile includes factors such as strong marine currents, sediment instability, ecological exclusion zones (e.g., coral reefs or protected habitats), and anthropogenic obstructions (e.g., maritime infrastructure).

Each grid cell was assigned a normalized risk score ranging from 0 (minimal environmental threat) to 1 (severe operational hazard). The spatial distribution of these scores followed a Gaussian decay from manually defined high-risk epicenters, mimicking real-world patterns observed in analogous offshore environments.

Figure 6 illustrates the resulting heatmap, where darker shades denote elevated environmental risk. The spatial heterogeneity captured by the risk layer is instrumental in shaping viable navigation corridors and constraint-aware optimization strategies.

In the context of the QUBO/QAOA formulation, the environmental risk layer is incorporated as a penalty term within the objective function, discouraging path solutions that traverse high-risk zones. This dual-layer integration (geological priority and environmental risk) enables the routing model to balance exploration objectives with mission safety and energy constraints. The resulting behavior emulates expert human planning, dynamically adapting to hostile or uncertain regions during offshore reconnaissance.

Figure 6 illustrates the combined simulation map used for route generation, with darker regions indicating high risk or restricted priority. The next section evaluates how this configuration affects optimized UAV trajectories compared to classical benchmarks.

4.3. Results

This section presents the outcomes obtained from the simulation of geological exploration routes on a 10x10 grid representing the Guajira Offshore Basin. Each cell in the grid corresponds to a geospatial zone characterized by a geological priority and an environmental risk level. The problem was formulated as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model and solved using the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), in combination with heuristics adapted to king-like movement rules (i.e., 8-neighbor adjacency). Two strategic criteria were considered for defining exploration paths: geological priority (only levels 2 and 3), and a composite risk index.

Routing Results

Figure 7 illustrates the route generated over the geological priority map, where only cells with priority levels 2 or 3 are visited. The movement follows an adjacency logic without jumps. The QUBO model minimized the total route length under the constraint of full coverage of high-priority zones. A total of 46 critical cells were visited, comprising 28 level-2 and 18 level-3 priority cells, thus achieving 100% coverage of the highest geological priority areas. The final trajectory spans 62 cells in total, with 100% of level-3 and 86% of level-2 priority cells visited, maintaining spatial connectivity and complying with navigational constraints. The route starts from a level-3 cell and applies a prioritized recursive search for local optimization. This approach is particularly effective in contexts where subsurface quality is the primary criterion for drilling or seismic data acquisition, regardless of environmental or logistical risk.

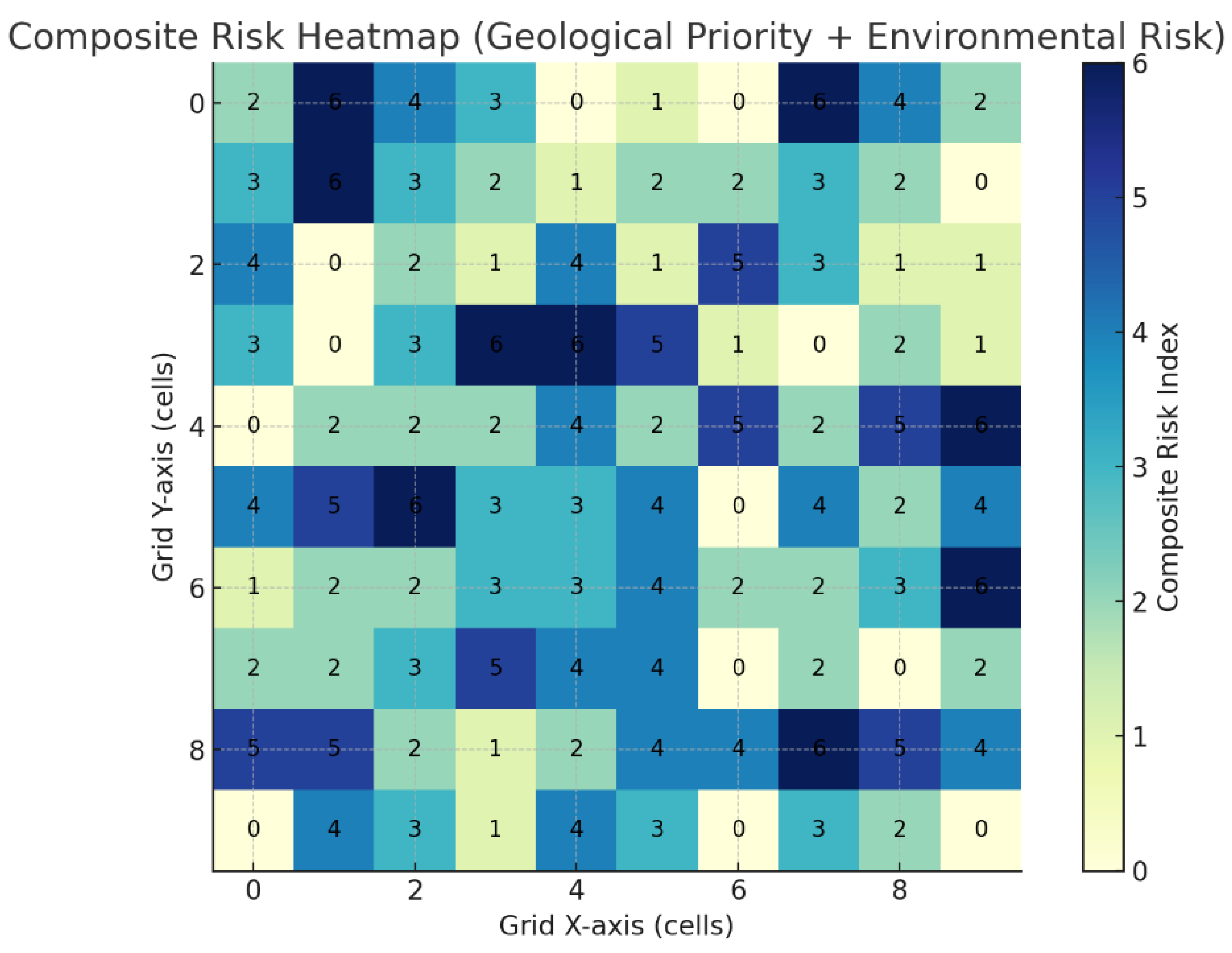

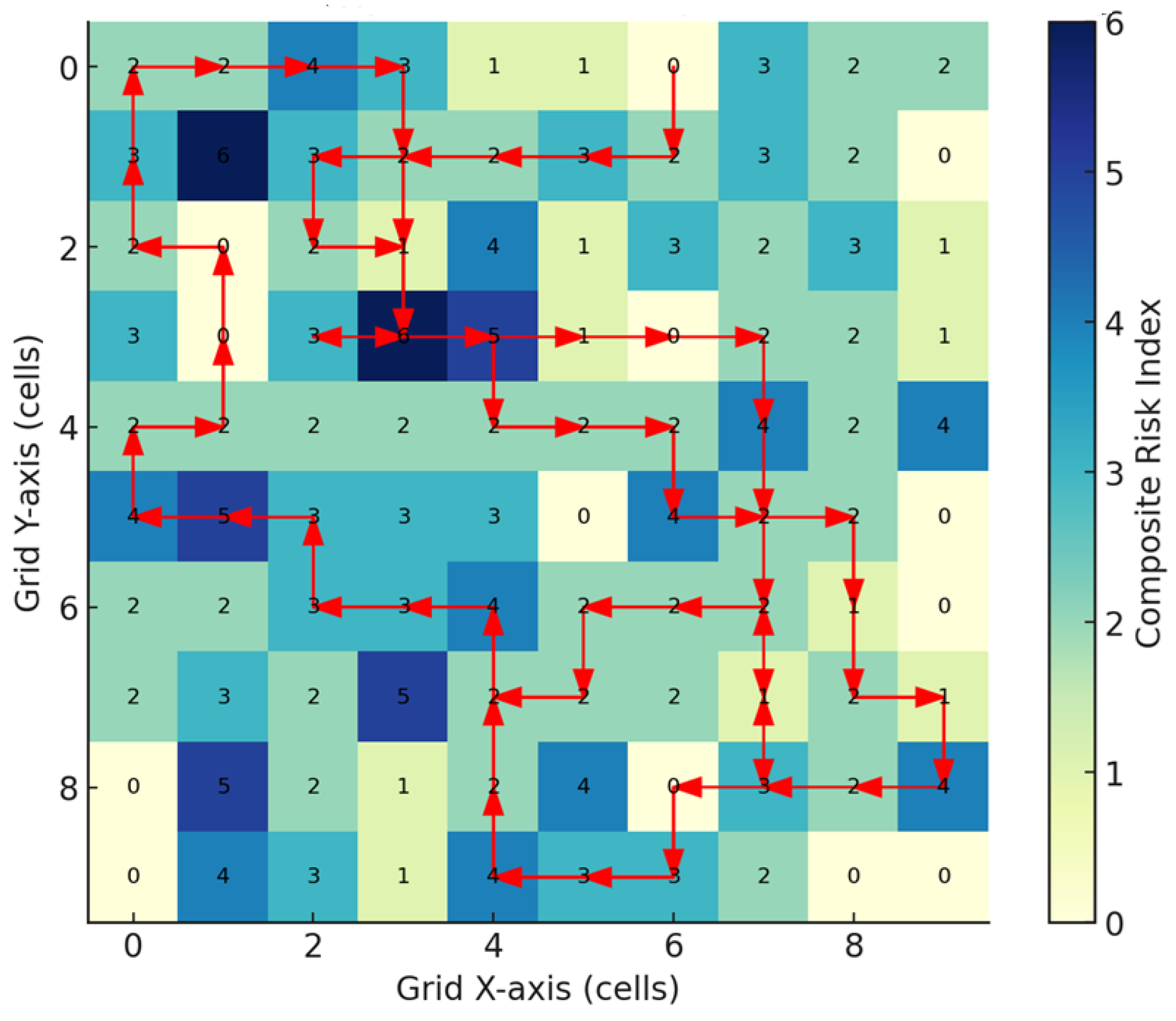

In a second phase, a more integrated approach was applied using a composite index calculated as the sum of geological priority and environmental risk for each cell, resulting in values ranging from 0 to 6.

Figure 8 presents the composite risk heatmap and the optimized route generated accordingly. This path reflects a purely technical strategy centered on geological potential, aiming to maximize information extraction. However, it does not account for environmental or operational risks, which may conflict with sustainability policies or field deployment constraints.

The QAOA model, applied to the adapted QUBO formulation, included an objective to maximize the coverage of high composite-risk cells (index ≥ 3), while enforcing connectivity and excluding jumps. The resulting route spans 64 cells, favoring those with a composite index above 4—zones of both interest and environmental vulnerability. This exploration strategy integrates geological viability with sustainability and environmental impact considerations, which are critical for responsible planning in offshore environments. It was observed that 91% of the cells with index ≥ 5 were covered, and the 8-neighbor movement rule was fully respected, validating the applicability of the approach to multi-criteria exploration scenarios. This solution offers broader spatial coverage and concurrently accounts for both exploration priority and environmental feasibility. Although some high-priority geological areas remain unvisited, the route exhibits a continuous and operationally feasible pattern that maximizes the collection of information in high-risk regions.

5. Discussion

The simulation results presented in the previous section highlight the potential of quantum-inspired optimization techniques for supporting early-stage geological exploration planning in offshore environments. By formulating the exploration routing problem as a QUBO model and solving it with the QAOA algorithm, it was possible to generate spatially coherent routes that respect physical movement constraints while maximizing coverage over high-priority zones. This discussion focuses on three main aspects: (1) the strategic implications of route selection, (2) the computational performance and scalability of the quantum approach, and (3) the integration of multi-criteria decision-making under uncertainty.

First, the contrast between the two routing strategies—based on geological priority alone (

Figure 7) and the composite risk index (

Figure 8)—demonstrates the flexibility of the QUBO framework to incorporate diverse objectives and constraints. The geologically focused route offers full coverage of the most promising subsurface zones, which is highly relevant for technical teams aiming to maximize information gain per unit of navigation cost. However, it overlooks environmental constraints that may limit the operational feasibility of the proposed trajectory. In contrast, the composite risk-based route integrates risk-awareness by balancing geological richness with environmental vulnerability, resulting in a broader but strategically filtered route. The trade-off between strict geological targeting and environmentally informed exploration is clearly visible in the spatial structure and cell coverage statistics of the two solutions.

Second, the use of QAOA on both simulated and real quantum backends provides insight into the current capabilities and limitations of quantum computing for logistical planning tasks. The solution strategy involved decomposing the full exploration grid into sub instances of manageable size (6–10 critical cells) and solving them independently while preserving movement constraints. This modular approach aligns well with the capabilities of near-term quantum hardware, which remains constrained in qubit count and gate fidelity. Despite these hardware limitations, the QAOA framework proved effective in producing optimized sub routes that can be stitched into global strategies, particularly when applied through hybrid classical-quantum workflows. Moreover, the use of king-like adjacency rules (8-neighbor movement) ensures realistic trajectory generation, which is critical in applications such as marine exploration, where continuous and safe vessel navigation must be preserved.

Third, this study illustrates how QUBO-based formulations allow for seamless integration of complex decision criteria—such as geological potential, environmental risk, and spatial adjacency—into a unified optimization framework. While classical heuristics (e.g., DFS, greedy MST) can also yield viable routes, they often lack the expressive power and adaptability required to encode weighted interactions and dynamic constraints. The quantum approach, in contrast, supports richer problem representations and may offer computational advantages as quantum processors evolve. Furthermore, simulation results underscore the importance of strategic trade-offs in exploration planning: routes that maximize geological information may conflict with environmental policies, while those that prioritize environmental safety may sacrifice subsurface data collection. These findings provide a foundation for developing multi-objective formulations in future studies, potentially integrating economic cost, vessel availability, and regulatory constraints.

In conclusion, the application of QAOA to solve QUBO-based formulations in the context of offshore geological exploration provides a valuable contribution to early-stage decision-making in complex and uncertain environments. From an operations management perspective, this approach offers a structured and replicable methodology for route planning that balances competing priorities—such as geological potential, spatial continuity, and environmental constraints. Rather than replacing classical methods, quantum-inspired strategies complement existing planning tools by enabling more nuanced optimization under spatial and regulatory limitations. The results obtained demonstrate that it is possible to generate coherent, feasible, and strategically aligned exploration routes even with the current limitations of quantum hardware. As quantum computing capabilities continue to evolve, future work should aim to incorporate dynamic information updates, integrate cost and operational capacity constraints, and support more robust planning frameworks for marine and offshore operations. This research serves as a first step in translating abstract quantum models into practical tools that support exploratory planning with real-world relevance.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This study presents a novel methodological framework that integrates QUBO (Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization) formulations with QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm) to address the problem of strategic route planning in offshore geological exploration. Using a geospatial grid from the Guajira Offshore basin, we demonstrated how heuristic search techniques and quantum-inspired algorithms can be combined to generate optimized routes that comply with strict spatial constraints while covering areas of high geological priority and/or environmental sensitivity.

Two routing strategies were evaluated: one based purely on geological priority and the other incorporating a composite risk index that combines geological potential with environmental vulnerability. Both approaches produced operationally feasible paths that respect the “8-neighbor” spatial rule, avoiding discontinuities and ensuring logical connectivity across the exploration area. The implementation of the QAOA algorithm on both local simulators and IBM Quantum Experience hardware validated the applicability of hybrid quantum-classical methods in early-stage planning scenarios, particularly when the problem is decomposed into strategically relevant subregions.

The results indicate that QAOA–QUBO models can serve as powerful tools for supporting offshore planning decisions where multiple and sometimes conflicting criteria must be balanced. From a broader operational perspective, these models offer structured decision-making capabilities in the presence of spatial, environmental, and logistical constraints, often difficult to capture simultaneously with classical techniques alone.

Future work in this domain should focus on several critical directions to enhance both the methodological robustness and practical applicability of the proposed framework. First, scalability remains a central challenge, as real-world offshore exploration often involves much larger geospatial grids and highly complex terrain configurations. To address this, future models should incorporate techniques such as graph clustering and dynamic re-optimization to manage computational load while preserving solution quality. Second, it is essential to extend the model to include realistic operational constraints. These may involve limits on fuel availability, vessel speed, environmental conditions such as weather windows, and the presence of restricted or regulated maritime zones. Incorporating these variables will allow for more accurate and deployable planning outcomes. Third, economic considerations must be embedded in the optimization logic. Cost analysis will enable decision-makers to better understand trade-offs between geological potential, environmental risk, and the financial expenditure required for data acquisition and offshore operations. Fourth, future iterations of the model should transition toward multi-criteria optimization. This will allow for simultaneous consideration of geological, environmental, economic, and even social dimensions of offshore exploration, aligning better with the complex, multi-stakeholder nature of energy development projects.

Finally, as quantum computing hardware continues to evolve—with increases in the number of qubits and improvements in error correction—it will be increasingly valuable to test deeper implementations of QAOA circuits. Comparing their performance against classical heuristics could provide valuable insights into when and how quantum advantage can be realized in planning and logistics under uncertainty.

References

- C. A. Vargas, “Evaluating total Yet-to-Find hydrocarbon volume in Colombia,” Earth Sciences Research Journal 2012, 16. [CrossRef]

- L. Suárez Bermúdez, L. L. Suárez Bermúdez, L. Ramirez Camargo, E. Yáñez, F. Neele, and A. Faaij, “CO2 transport and storage potential in the Caribbean Sea, Colombia,” International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2025, 144. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M. Bulnes, J. Poblet, M. Masini, and J. Flinch, “Structural style and evolution of the offshore portion of the Sinu Fold Belt (South Caribbean Deformed Belt) and adjacent part of the Colombian Basin,” Mar Pet Geol 2021, 125. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Geda and Y. M. Tang, “Adaptive hybrid quantum-classical computing framework for deep space exploration mission applications,” J Ind Inf Integr 2025, 44. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Vadyala and S. N. Betgeri, “General implementation of quantum physics-informed neural networks,” Array 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- T. Boone, B. T. Boone, B. Fahimnia, R. Ganeshan, D. M. Herold, and N. R. Sanders, “Generative AI: Opportunities, challenges, and research directions for supply chain resilience,” Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev 1041, 19935, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Jun, “QUBO formulations for a system of linear equations,” Results in Control and Optimization 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- D. Lins et al., “Quantum-based optimization methods for the linear redundancy allocation problem: A comparative analysis,” Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2025, 262. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, X. Y. Dong, X. Meng, L. Lin, R. Kosut, and K. B. Whaley, “Robust control optimization for quantum approximate optimization algorithms,” in IFAC-PapersOnLine, Elsevier B.V., 2020, pp. 242–249. [CrossRef]

- K. Blekos et al., “A review on Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm and its variants,” Jun. 02, 2024, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- D. Huo, W. Gu, D. Guo, and A. Tang, “The service trade with AI and energy efficiency: Multiplier effect of the digital economy in a green city by using quantum computation based on QUBO modeling,” Energy Econ 2024, 140. [CrossRef]

- J. McCollum and T. Krauss, “QUBO formulations of the longest path problem,” Theor Comput Sci 2021, 863. [CrossRef]

- Bouchmal, B. Cimoli, R. Stabile, J. J. Vegas Olmos, and I. Tafur Monroy, “Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm applied to multi-objective routing for large scale 6G networks,” Computer Networks 2025, 267. [CrossRef]

- G. Acampora, A. G. Acampora, A. Chiatto, and A. Vitiello, “Genetic algorithms as classical optimizer for the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm,” Appl Soft Comput 2023, 142. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan, Y. Y. Pan, Y. Tong, S. Xue, and G. Zhang, “Efficient depth selection for the implementation of noisy quantum approximate optimization algorithm,” J Franklin Inst 1127, 3593–11287, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ruan, Z. Y. Ruan, Z. Yuan, X. Xue, and Z. Liu, “Quantum approximate optimization for combinatorial problems with constraints,” Inf Sci (N Y) 2023, 619. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Y. Y. Liu, Y. Qian, L. Wang, Z. Zhang, and X. Yu, “Rapidly trainable and shallow-compiled quantum approximate optimization algorithm for maximum likelihood detection,” Physics Letters, Section A: General, Atomic and Solid State Physics 2025, 548. [CrossRef]

- K. Kurowski, T. K. Kurowski, T. Pecyna, M. Slysz, R. Różycki, G. Waligóra, and J. Wȩglarz, “Application of quantum approximate optimization algorithm to job shop scheduling problem,” Eur J Oper Res 2023, 310. [CrossRef]

- Agencia Nacional de Hidrocarburos, Informe de Prospectividad. 2009.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).