Research Problem and Significance

Educational institutions and organizations increasingly recognize the limitations of traditional instruction for developing the adaptive expertise needed in today’s complex environments. Immersive learning—which engages learners in authentic, contextually rich environments through active participation in meaningful tasks—has gained significant attention as a potential solution (Dede, 2009; Shaffer, 2006). However, implementation varies widely, with inconsistent results across contexts.

Recent reviews in adjacent fields have documented similar patterns of promising but variable outcomes. For example, Radianti et al. (2020) found significant potential but inconsistent implementation of virtual reality in higher education, while Joksimović et al. (2023) identified both benefits and challenges in problem-based learning approaches. Similarly, Cheng et al. (2022) documented variability in augmented reality effectiveness in K-12 settings, and Kuhn and Weissman (2023) highlighted the complex interaction between simulation fidelity and learning outcomes in medical education. The present study extends this work by examining immersive learning more broadly while focusing specifically on the conditions that moderate effectiveness.

This research addresses three critical gaps in the field’s understanding of immersive learning:

The differential effects of immersive learning on distinct learning outcomes (knowledge acquisition, transfer, and motivation)

The moderating role of individual differences and implementation factors

The practical requirements for effective design and implementation across diverse educational contexts

By systematically analyzing both existing research and new empirical data, this study provides evidence-based guidance for researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and educational leaders seeking to leverage immersive learning effectively.

Theoretical Framework and Integrated Model

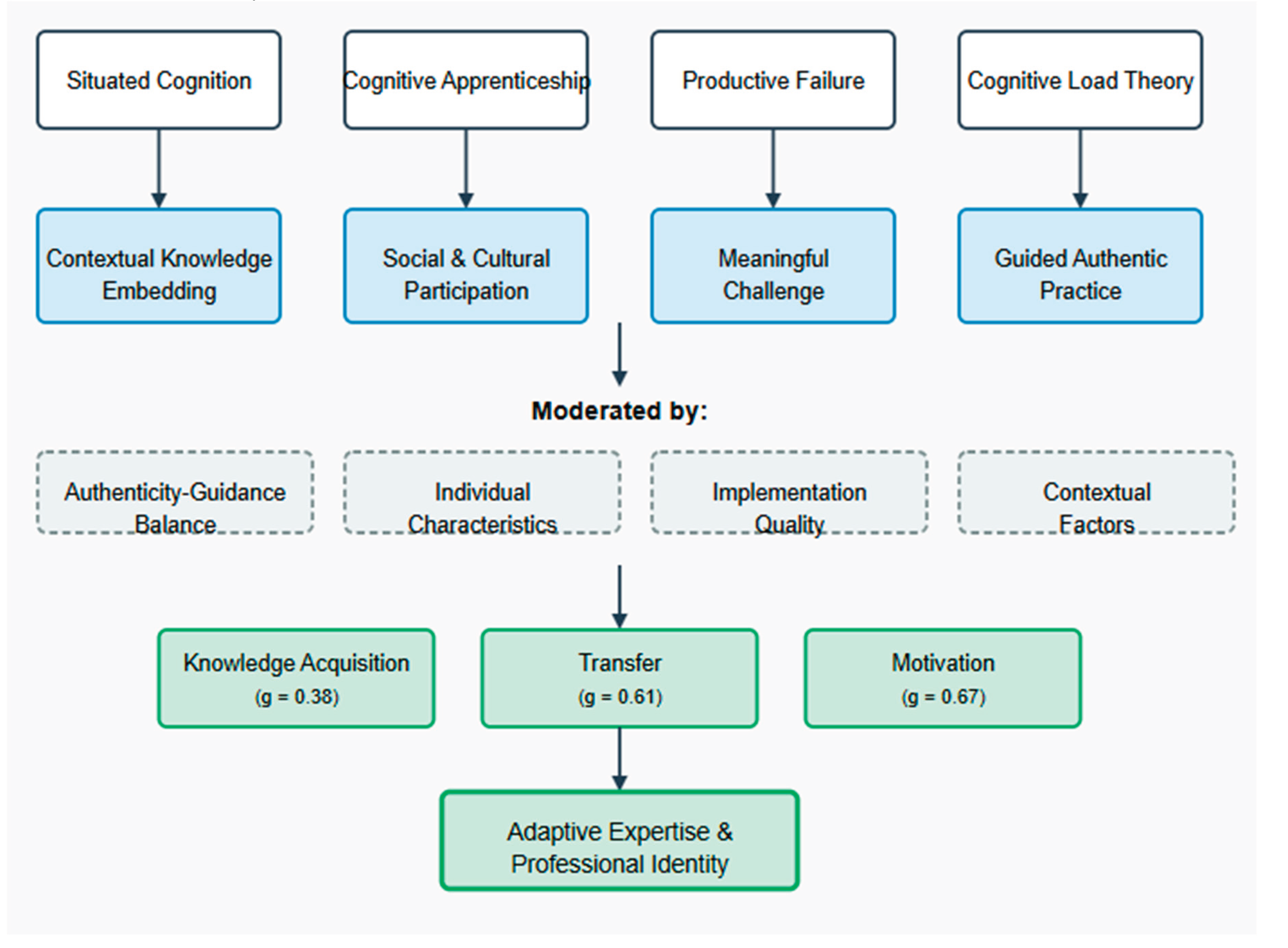

This investigation is grounded in an integrated model drawing from several established cognitive and learning theories (

Figure 1). These theoretical perspectives converge to explain why and how immersive learning can enhance educational outcomes, while also highlighting potential limitations and boundary conditions.

Situated Cognition Theory posits that knowledge is fundamentally tied to the context in which it is learned and used (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). This perspective suggests that authentic learning environments should enhance knowledge transfer by embedding learning in contexts similar to those where knowledge will be applied. The theory emphasizes that learning is inherently social and involves enculturation into communities of practice.

Cognitive Apprenticeship extends traditional apprenticeship models to cognitive domains by making expert thinking visible through modeling, coaching, and scaffolding (Collins & Kapur, 2022). This framework emphasizes the role of guided participation in authentic practices, with experts gradually transferring responsibility to learners as they develop competence.

Productive Failure research demonstrates that struggling with complex problems before receiving direct instruction can prepare learners to better understand concepts when they are eventually presented (Kapur & Bielaczyc, 2012). This counterintuitive finding suggests value in authentic complexity, even when it initially leads to unsuccessful attempts, by activating prior knowledge and highlighting knowledge gaps.

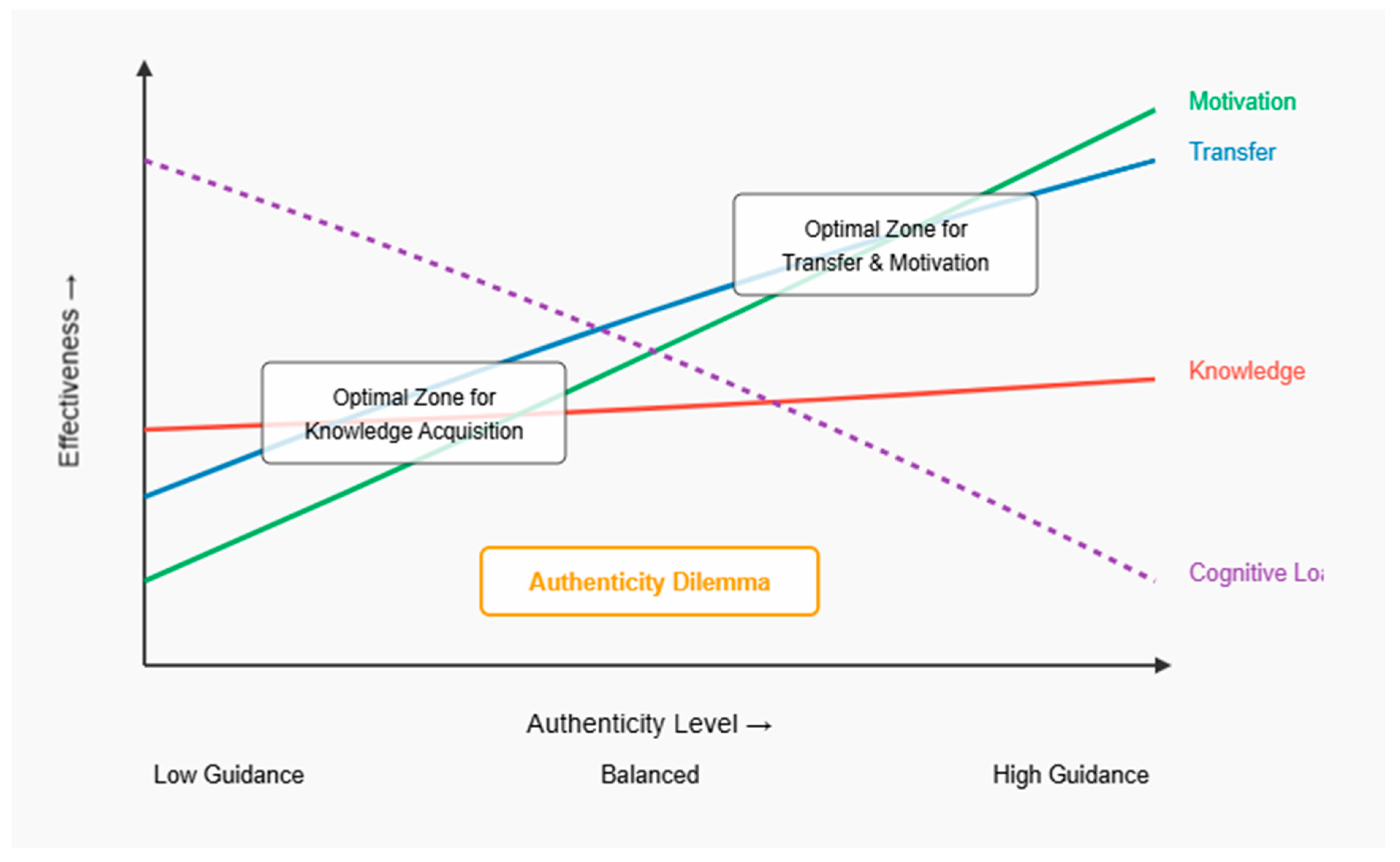

The Authenticity Dilemma, as conceptualized by Nachtigall, Shaffer, and Rummel (2024), describes the tension between the motivational benefits of authentic complexity and the cognitive demands this complexity creates. This framework suggests that optimal immersive learning requires balancing authenticity with appropriate scaffolding.

Cognitive Load Theory provides an important counterpoint by highlighting the limited capacity of working memory and the potential for complex environments to overwhelm cognitive processing (Sweller et al., 2019). This perspective helps explain why immersive learning might be less effective for novices or without appropriate guidance.

These theoretical perspectives intersect to create an integrated model of immersive learning effectiveness (

Figure 1) that guides this investigation. The model proposes that immersive learning enhances outcomes through multiple mechanisms:

Contextual embedding of knowledge that facilitates transfer

Social and cultural participation that develops professional identity

Meaningful challenges that generate intrinsic motivation

Guided authentic practice that builds adaptive expertise

However, the model also identifies key moderating factors that determine when these mechanisms operate effectively:

The balance between authenticity and guidance (the authenticity dilemma)

Individual learner characteristics (prior knowledge, self-regulation skills)

Implementation quality factors (duration, facilitation, technology integration)

Contextual factors (educational level, domain, institutional support)

This integrated theoretical framework provides the foundation for the research questions and methodological approach, while offering a lens for interpreting findings and their implications.

Research Questions

This study addresses the following research questions:

What are the overall effects of immersive learning on knowledge acquisition, transfer, and motivational outcomes compared to conventional instruction?

How do design features, implementation quality, and individual learner characteristics moderate these effects?

What are the practical requirements, challenges, and costs associated with effective implementation of immersive learning in diverse educational contexts?

Methods

A mixed-methods approach was employed combining meta-analysis of existing experimental studies with original case study research to provide both breadth and depth in addressing the research questions.

Measurement Quality Assessment

Given the importance of measurement quality for meta-analytic validity, separate analysis were conducted of measurement characteristics in the primary studies. Each outcome measure was coded for:

Type of measurement (standardized, researcher-developed, authentic performance)

Reported reliability (coefficient alpha or equivalent)

Timing of measurement (immediate, delayed)

Validity evidence presented

This assessment was used to examine potential relationships between measurement characteristics and reported effects, and to contextualize the interpretation of meta-analytic findings.

Case Study Methodology

To complement the meta-analysis with in-depth implementation data, three case studies were conducted across different educational contexts. These cases were selected to represent diverse learning contexts, learner populations, and immersive learning approaches while allowing for cross-case comparison on key dimensions.

The three cases were strategically selected based on the following criteria:

Diversity of educational contexts: The cases span K-12 education (Case 3), higher education (Case 2), and professional training (Case 1), allowing examination of how immersive learning functions across the educational spectrum.

Variety of immersive approaches: Each case represents a distinct theoretical approach to immersive learning—goal-based scenarios (Case 1), epistemic games (Case 2), and cognitive apprenticeship (Case 3)—providing insights into how different immersive designs function in practice.

Range of implementation resources: The cases represent varying levels of resource investment, from highly resourced corporate training to more constrained K-12 implementation, enabling analysis of resource-outcome relationships.

Comparable outcome measures: All cases included parallel measures of knowledge acquisition, transfer, and motivation, allowing for meaningful cross-case comparison on key outcomes.

Researcher access: In all cases, the research team had sufficient access to observe implementation, collect comprehensive data, and interview key stakeholders, ensuring robust case documentation.

Together, these cases provide a representative sample of immersive learning implementations that enables both within-case analysis of implementation dynamics and cross-case comparison of patterns and principles.

Case 1: Corporate Sales Leadership Training Methodological Details

Context and Design: A goal-based scenario approach for sales leadership training was implemented at a global technology company over a 14-month period (January 2023 - February 2024). The design immersed sales managers (n = 124) in extended simulations where they built and led virtual teams through realistic client engagements.

Researcher Role: The researcher served as a design consultant and evaluation lead, working with the company’s learning and development team throughout implementation while maintaining independence for evaluation activities.

Sampling Strategy: All incoming sales managers during the implementation period participated in the training (n = 124). For interviews, a stratified random sample of participants (n = 32) was selected based on pre-training experience, performance during training, and geographic region to ensure diverse perspectives.

Data Collection Timeline:

Pre-implementation assessment (January-March 2023)

Implementation and concurrent data collection (April 2023-January 2024)

Post-implementation evaluation (February-March 2024)

Six-month follow-up (April-August 2024)

Data collection included:

Pre-post assessment of leadership competencies using standardized instruments

Comparison with historical data from previous training approach (n = 156)

Performance tracking for 6 months post-training

Qualitative interviews with participants and their supervisors

Trustworthiness Procedures:

Member checking of interview findings with participants

Triangulation of data sources (competency assessments, supervisor evaluations, participant interviews)

Independent coding of qualitative data by two researchers

Reflexivity journals maintained by researchers to document potential biases

Case 2: Engineering Ethics in Higher Education Methodological Details

Context and Design: An epistemic game approach to teaching professional ethics was implemented for junior-level engineering students at a public research university during the Fall 2023 semester. A quasi-experimental design compared the epistemic game approach (n = 60) with a traditional case study approach (n = 60) across two course sections.

Researcher Role: The researcher collaborated with engineering faculty to design the intervention but was not involved in direct instruction. The researcher led data collection and analysis activities with assistance from graduate research assistants not involved in course delivery.

Sampling Strategy: Course sections were assigned to conditions based on scheduling constraints. Focus groups used maximum variation sampling to ensure representation of students with diverse academic backgrounds, gender, and engagement levels.

Data Collection Timeline:

Intervention design and development (Spring-Summer 2023)

Pre-assessments (August 2023)

Implementation and process data collection (September-November 2023)

Post-assessments and focus groups (December 2023)

Data collection included:

Pre-post comparison of ethical reasoning using the Engineering Ethical Reasoning Instrument

Comparison between epistemic game section and case-study section

Analysis of student work products using professional rubrics

Focus groups with students and instructors

Implementation cost and resource tracking

Trustworthiness Procedures:

Blind scoring of student work by raters unaware of condition

Standardized protocols for all assessments and focus groups

Audit trail of all methodological decisions

Triangulation across quantitative and qualitative data sources

Case 3: Middle School Historical Understanding Methodological Details

Context and Design: An immersive learning module on civil rights history using a cognitive apprenticeship approach was implemented for 8th-grade students (n = 175) in a diverse urban district during the 2023-2024 academic year. Outcomes were compared with the previous year’s traditional curriculum (n = 168).

Researcher Role: The researcher provided professional development for teachers and ongoing implementation support while independent evaluators conducted classroom observations and assessment activities.

Sampling Strategy: All 8th-grade students in the participating school received the intervention. For teacher interviews, all participating teachers (n = 7) were included in data collection.

Data Collection Timeline:

Teacher professional development (August 2023)

Pre-assessments (September 2023)

Implementation and concurrent data collection (October-December 2023)

Post-assessments (December 2023-January 2024)

Follow-up interviews (February 2024)

Data collection included:

Pre-post assessment of historical thinking skills using validated instruments

Comparison with previous year’s traditional curriculum

Student self-efficacy and interest surveys

Analysis of work products using disciplinary rubrics

Teacher time logs and implementation fidelity measures

Trustworthiness Procedures:

Standardized observation protocols

Calibration of scorers for historical thinking assessments

Peer debriefing among the research team

Prolonged engagement in the research setting

Case Study Analysis

Quantitative data from each case were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods (t-tests, ANOVA, regression). Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis with initial coding based on the theoretical framework, followed by emergent coding to identify unanticipated themes. Implementation data were systematically categorized to identify resource requirements, challenges, and success factors.

Cross-Case Analysis

A systematic cross-case analysis was conducted using a comparative framework focused on:

Implementation contexts and constraints

Design features and their alignment with theoretical principles

Patterns of effectiveness across outcome types

Resource requirements and challenges

Strategies for addressing the authenticity dilemma

This analysis used matrices to identify patterns across cases while preserving the contextual richness of individual implementations.

Results

Meta-Analysis Findings

Overall Effects

The meta-analysis revealed positive effects of immersive learning across all outcome categories, with significant variation in effect magnitude (

Table 1).

These results indicate that immersive learning had a moderate positive effect on knowledge acquisition, with stronger effects on transfer and motivation. However, the high I² values indicate substantial heterogeneity, suggesting important moderating factors.

Measurement Quality Analysis

Analysis of measurement characteristics revealed significant variation in the types of measures used across outcome categories (

Table 2).

Knowledge acquisition was primarily assessed through researcher-developed or standardized tests, while transfer measures more frequently involved authentic performance assessments. Motivation measures showed the highest rates of reliability reporting and validity evidence. Delayed measurement was relatively uncommon across all outcome categories, limiting insights into the durability of effects.

Meta-regression analyses found no significant relationship between reported reliability coefficients and effect sizes for knowledge acquisition (β = 0.05, p = .42) or motivation (β = 0.08, p = .31), but a significant positive relationship for transfer measures (β = 0.23, p = .02), suggesting that more reliable transfer measures tended to show larger effects.

These measurement quality findings have important implications for interpreting the meta-analytic results. The significant relationship between transfer measure reliability and effect size suggests that the strong transfer effects observed (g = 0.61) may be particularly robust, as more reliable measures showed larger effects. However, the predominance of authentic performance assessments for transfer (42%) also raises questions about whether these measures better align with immersive learning approaches compared to traditional standardized tests, potentially contributing to the larger effect sizes observed for transfer.

Moderator Analyses

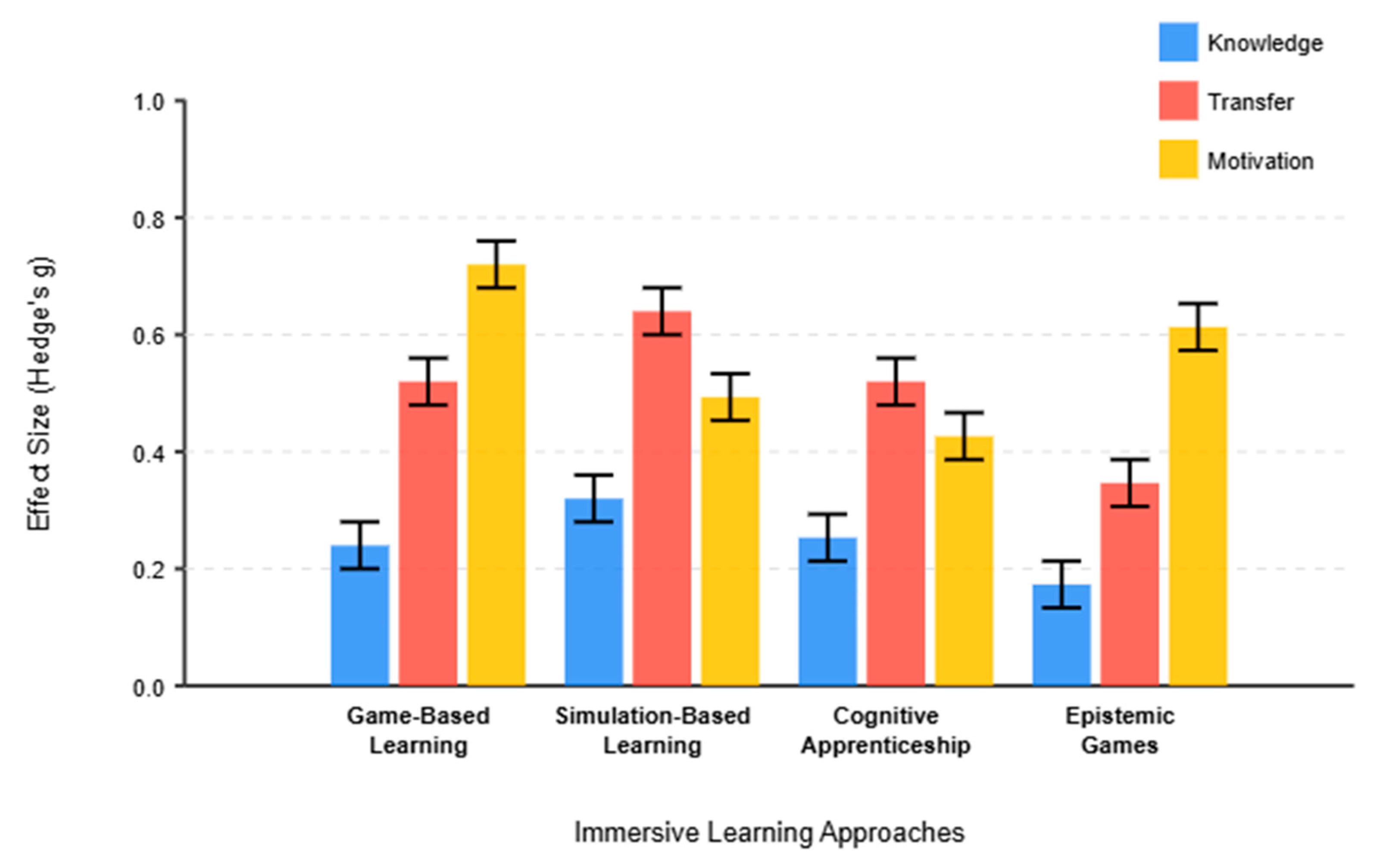

Immersive Approach Type

Different immersive approaches yielded varying effects on outcomes (

Table 3).

Simulation-based learning showed the strongest effects on knowledge acquisition and transfer, while game-based learning had the strongest effect on motivation. Differences between approach types were statistically significant for knowledge acquisition (Q = 9.74, p = .021) but not for transfer or motivation.

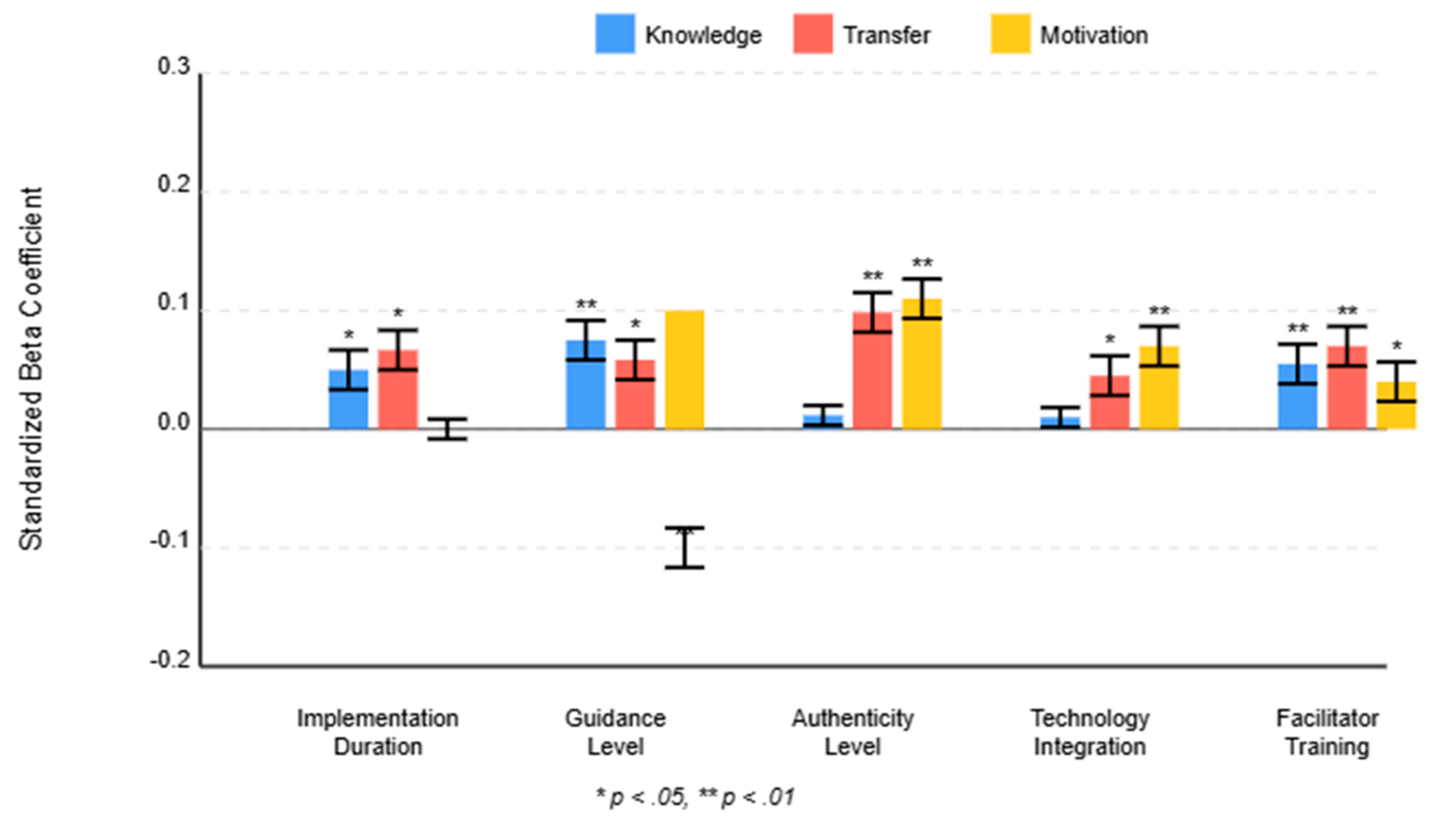

Implementation Features

Several implementation features significantly moderated effectiveness (

Table 4).

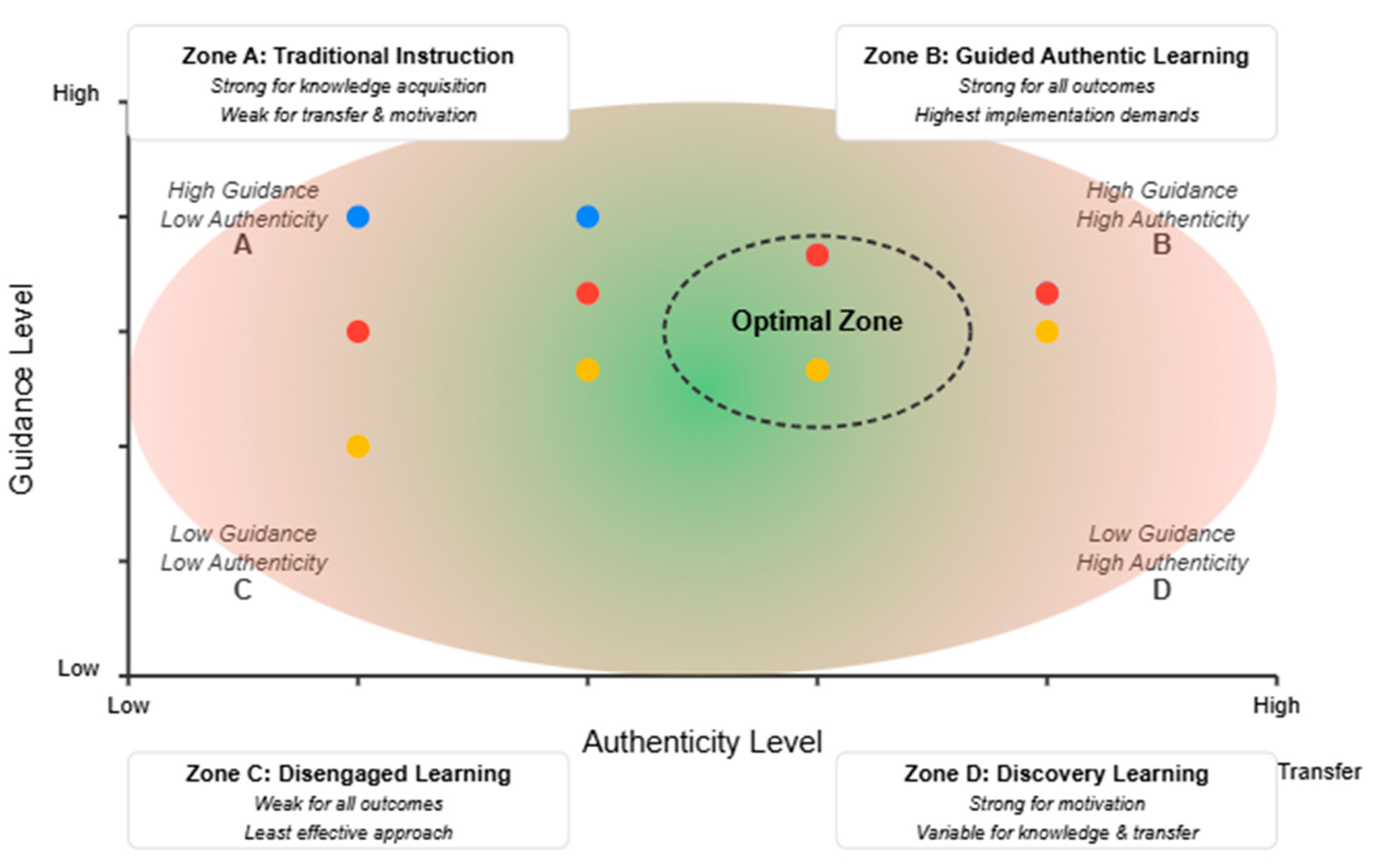

These results indicate that:

Longer implementations showed stronger effects on knowledge and transfer but not motivation

Higher guidance levels enhanced knowledge and transfer but reduced motivational effects

Higher authenticity enhanced transfer and motivation but had no significant effect on knowledge

Technology integration enhanced transfer and motivation but not knowledge

Facilitator training enhanced effectiveness across all outcome types

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between immersion level and engagement, revealing a non-linear pattern with a threshold effect. The figure also shows important individual differences in how learners respond to immersion.

Individual Differences

Individual characteristics significantly moderated the effectiveness of immersive learning (

Table 5).

These results suggest that:

Immersive learning was more effective for knowledge and transfer among learners with lower prior knowledge (expertise reversal effect)

Transfer effects were stronger for older/more advanced learners, while motivation effects were stronger for younger learners

Self-regulation skills significantly moderated effects on knowledge and transfer but not motivation

Figure 3 presents an interaction plot illustrating the expertise reversal effect. While immersive learning was generally beneficial, its effectiveness for knowledge outcomes decreased as prior knowledge increased. For learners with very high prior knowledge, traditional approaches sometimes outperformed immersive ones, consistent with cognitive load theory predictions.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots showed slight asymmetry for knowledge acquisition outcomes. Egger’s regression test was significant (p = .032), suggesting possible publication bias. Trim-and-fill analysis suggested 7 missing studies, with an adjusted effect size of g = 0.33 (95% CI [0.26, 0.41]), indicating only a small reduction from the original estimate. Publication bias analyses for transfer and motivation outcomes were non-significant.

Case Study Findings

Quantitative Results: The immersive approach yielded significantly higher leadership assessment scores (M = 76.3, SD = 8.2) compared to the previous approach (M = 64.1, SD = 9.6), t(278) = 11.64, p < .001, d = 1.39. Time-to-productivity decreased by 27 days on average (95% CI [21.3, 32.7]), representing a 23% improvement.

Qualitative Findings: Thematic analysis of interviews revealed four key success factors:

Authentic complexity that mirrored real workplace challenges

Strategic guidance from experienced coaches

Meaningful consequences for decisions

Structured reflection connecting simulation experiences to leadership principles

Implementation challenges included:

High development costs ($420,000 initial investment)

Technology barriers for international participants

Coaching consistency across facilitators

Resistance from some managers accustomed to traditional approaches

Illustrative Example: One particularly effective implementation strategy involved “scaffolded authenticity,” where participants initially encountered simplified team scenarios with substantial coaching, then progressively faced more complex situations with reduced guidance. As one participant explained: “The gradual increase in complexity allowed me to build confidence while still feeling challenged. Having a coach available to discuss my approach before finalizing decisions was critical, especially in the early scenarios.”

Another participant highlighted the value of structured reflection: “The daily debriefs were where everything clicked for me. Walking through what happened, why it happened, and connecting it to leadership principles helped me see patterns I could apply in real situations.” This reflection component was particularly important for transfer, as it helped participants abstract principles from specific scenarios.

Quantitative Results: Students in the epistemic game section showed significantly greater improvement in ethical reasoning scores (M = 16.2, SD = 3.1) compared to the case-study section (M = 13.8, SD = 3.4), F(1,117) = 15.27, p < .001, partial η² = .12. This effect was moderated by prior GPA, with stronger effects for middle-achieving students.

Qualitative Findings: Focus groups revealed that the epistemic game approach enhanced:

Engagement with ethical dimensions of engineering decisions

Recognition of multiple stakeholder perspectives

Application of ethical frameworks to novel situations

Professional identity development

Implementation data documented substantial resource requirements:

Development time: 320 hours ($48,000 equivalent cost)

Technology infrastructure: $15,000

Facilitator training: 24 hours per instructor

Instructional time: 40% more than traditional approach

Illustrative Example: A critical implementation strategy involved structured stakeholder interviews where students engaged with virtual professionals representing different perspectives on an ethical dilemma. Instructors noted that scaffolding these interactions with preparatory questions and post-interview reflection prompts significantly enhanced their effectiveness. As one instructor observed: “Having students prepare interview questions in advance, then reflect on what they learned afterward, transformed what could have been passive content delivery into active knowledge construction.”

The epistemic game approach was particularly effective at developing professional identity, as students reported increased identification with engineering ethics as a core professional responsibility. One student explained: “Before this class, I saw ethics as separate from ‘real engineering.’ Now I see ethical considerations as part of every engineering decision I’ll make.” This shift in perspective appeared to enhance both motivation and transfer of ethical reasoning skills to new contexts.

Instructors emphasized the importance of alignment between the immersive experience and assessment methods. As one faculty member noted: “When we shifted our assessment to include realistic ethical dilemmas rather than just concept questions, we saw much stronger performance from the epistemic game section. The traditional assessments weren’t capturing what they had learned.”

Quantitative Results: Students in the immersive module demonstrated significantly greater gains in historical thinking skills (M = 8.7, SD = 2.3) compared to the previous year’s traditional curriculum (M = 6.9, SD = 2.5), t(341) = 7.12, p < .001, d = 0.77. Effects were strongest for source evaluation (d = 0.91) and contextual understanding (d = 0.83).

Disaggregation by achievement quartiles revealed differential effects (

Figure 4):

Highest quartile: d = 0.41, p = .08

Middle-high quartile: d = 0.86, p < .001

Middle-low quartile: d = 0.92, p < .001

Lowest quartile: d = 0.48, p = .04

Qualitative Findings: Teachers reported significant changes in student engagement, with a 31% increase in voluntary participation. Analysis of student work revealed more sophisticated historical reasoning, particularly:

Recognition of historical context influencing decisions

Consideration of multiple perspectives on historical events

Critical evaluation of source reliability

Construction of evidence-based historical narratives

Implementation challenges included:

Technology access inequities for economically disadvantaged students

Extensive teacher preparation time (avg. 82 hours per teacher)

Tension with standardized testing requirements

Space and scheduling constraints for collaborative activities

Illustrative Example: A particularly successful implementation strategy involved the “expert thinking worksheet,” which made historical thinking processes explicit by prompting students to document their reasoning when analyzing primary sources. Teachers gradually removed this scaffold as students internalized the process. One teacher explained: “The worksheet initially seemed like extra work, but it forced students to slow down and think like historians instead of rushing to conclusions. By the end of the unit, most students didn’t need it anymore—they had internalized the questioning process.”

Teachers also reported that the cognitive apprenticeship approach was particularly effective for students who typically struggled with traditional instruction. As one teacher noted: “Many of my middle and lower-performing students really thrived with this approach. They could see the purpose of what they were learning, and the modeling helped them understand what good historical thinking actually looks like in practice.” This observation aligns with the quantitative findings showing the largest effects for middle-achieving students.

The impact on student motivation was particularly notable. One student reflected: “I used to think history was just memorizing facts and dates. Now I see it’s about investigating evidence and understanding why people did what they did. It’s like being a detective.” This shift from passive reception to active investigation appeared to significantly enhance engagement with historical content.

Cross-Case Analysis

Systematic comparison across the three case studies revealed several important patterns that inform understanding of immersive learning implementation (

Table 6).

The cross-case analysis revealed several consistent patterns:

Authenticity-Guidance Balance: All three cases employed different but systematic approaches to balancing authenticity and guidance. The corporate training used just-in-time coaching within highly authentic scenarios, the engineering ethics case used structured frameworks to scaffold complex ethical reasoning, and the historical understanding case used modeling and progressive fading of supports.

Resource-Outcome Relationships: Higher resource investments were generally associated with stronger implementation quality, but the relationship between resources and outcomes was not linear. Strategic allocation of resources to critical design elements appeared more important than overall resource levels.

Contextual Adaptation: Successful implementations adapted theoretical principles to specific contextual constraints. For example, the middle school case modified the cognitive apprenticeship approach to fit within standardized testing requirements, while the corporate training adapted goal-based scenarios to accommodate varying technology access across global regions.

-

Common Implementation Challenges: All three cases encountered challenges related to:

- ○

Facilitator/teacher preparation and support

- ○

Technology integration and troubleshooting

- ○

Time constraints and competing priorities

- ○

Resistance from stakeholders accustomed to traditional approaches

- ○

Assessment alignment with immersive learning experiences

-

Successful Strategies: Cross-cutting successful strategies included:

- ○

Explicit connection of immersive experiences to learning objectives

- ○

Progressive complexity with corresponding scaffolding

- ○

Structured reflection connecting experiences to principles

- ○

Ongoing facilitator support and communities of practice

- ○

Clear communication with all stakeholders about rationale and expectations

-

Differential Effectiveness: Across all three cases, immersive learning showed consistent patterns of differential effectiveness:

- ○

Moderate effects on knowledge acquisition across all contexts

- ○

Strong effects on transfer and application in all contexts

- ○

Strong motivational effects, particularly related to identity development

- ○

Most beneficial for learners in the middle achievement/experience range

Synthesis of Findings

Integration of meta-analysis and case study findings revealed several consistent patterns:

Differential effects by outcome type: Both datasets confirmed stronger effects on transfer and motivation than on knowledge acquisition.

The authenticity-guidance balance: The optimal balance differed by outcome type, with higher guidance enhancing knowledge and transfer but potentially reducing motivation.

Individual difference effects: Prior knowledge and self-regulation skills consistently moderated effectiveness, with stronger benefits for certain learner profiles.

Implementation requirements: All case studies documented substantial resource requirements for high-quality implementation, consistent with moderator analyses showing the importance of implementation duration and facilitator training.

Context-specific adaptation: Effective designs required significant adaptation to specific educational contexts, learner characteristics, and content domains.

Discussion

Interpretation of Key Findings

This mixed-methods investigation provides nuanced insights into the effectiveness, moderators, and implementation requirements of immersive learning.

Differential Effectiveness by Outcome Type

The stronger effects on transfer and motivation compared to knowledge acquisition align with the theoretical foundations of immersive learning. The authentic contexts and tasks that characterize immersive learning appear particularly effective for helping learners understand when and how to apply knowledge (transfer) and for generating intrinsic interest in the content (motivation).

However, the moderate effects on knowledge acquisition (g = 0.38) suggest that immersive learning should not be viewed as a universal replacement for direct instruction. Instead, it appears most valuable when transfer and motivational outcomes are primary goals or when combined with appropriate direct instruction components.

Alternative Explanations and Critical Analysis

Several alternative explanations for these findings warrant consideration:

1. Novelty Effects vs. Inherent Advantages

The stronger motivational effects observed with immersive learning might reflect novelty effects rather than inherent advantages of immersion. However, several lines of evidence argue against this interpretation:

The meta-analysis included studies with implementation durations ranging from 1 to 16 weeks, and moderator analyses showed no significant decline in motivational effects with longer implementations.

Case studies with repeated measures over time showed sustained engagement rather than declining interest patterns typical of novelty effects.

Qualitative data from case studies highlighted specific features of immersive learning (authenticity, agency, meaningful contexts) that supported motivation through established psychological mechanisms.

Nevertheless, the possibility of novelty contributing to motivational effects cannot be entirely dismissed, particularly for short-term implementations or technology-rich approaches that are uncommon in the educational context.

2. Measurement Artifacts

The pattern of stronger effects for transfer and motivation could potentially reflect measurement artifacts rather than true differences in effectiveness. Transfer and motivation are often measured with more authentic, performance-based assessments, while knowledge acquisition typically relies on standardized tests designed for traditional instruction.

The measurement quality analysis provides some support for this concern—transfer was more frequently assessed through authentic performance measures (42%) than knowledge acquisition (6%). However, subgroup analyses based on measurement type showed that the pattern of stronger transfer effects persisted even when comparing studies using similar measurement approaches. Additionally, the case studies, which used parallel measurement approaches across outcome types, showed the same pattern of stronger transfer and motivation effects.

The significant positive relationship between transfer measure reliability and effect size (β = 0.23, p = .02) suggests that measurement quality influences reported outcomes. This finding has important implications for interpreting the strong transfer effects (g = 0.61) observed in the meta-analysis. On one hand, the relationship suggests that more reliable transfer measures yield stronger effects, potentially indicating that the true effect on transfer is robust. On the other hand, it raises questions about whether studies with less reliable measures might underestimate transfer effects, contributing to variability in the literature.

3. Selection and Implementation Bias

The positive effects might reflect selection bias in which only successful implementations are published or studied. The publication bias analysis indicated some evidence of this for knowledge outcomes but not for transfer or motivation. Additionally, the case studies documented challenges and implementation variations that would likely be underreported in published literature.

More concerning is the possibility of implementation bias—immersive learning may receive more careful design attention and resources than comparison conditions. The case studies documented substantial resource investments in immersive approaches, raising questions about whether equivalent investment in traditional approaches might yield similar improvements. This possibility cannot be fully addressed with the available data and remains an important consideration for interpreting the findings.

The Authenticity Dilemma

The findings empirically validate the authenticity dilemma proposed by Nachtigall et al. (2024). The meta-analysis demonstrates that authenticity level positively predicted transfer and motivation but not knowledge acquisition, while guidance level positively predicted knowledge and transfer but negatively predicted motivation.

This tension suggests that designing effective immersive learning requires intentional decisions about the balance between authenticity and guidance based on primary learning goals. The case studies further illustrate how this balance can be achieved through strategic scaffolding, expert facilitation, and structured reflection integrated within authentic contexts.

Figure 5 illustrates how the authenticity dilemma manifests across different outcome domains, highlighting the need for deliberate design decisions based on primary learning objectives.

Individual Differences as Boundary Conditions

The significant moderating effects of individual characteristics highlight important boundary conditions for immersive learning effectiveness. The expertise reversal effect (stronger benefits for learners with lower prior knowledge) suggests that immersive approaches may be particularly valuable for introductory or foundational learning experiences.

Similarly, the moderating effect of self-regulation skills suggests the need for differentiated support within immersive environments. The case studies demonstrated successful strategies for such differentiation, including adaptive coaching, optional scaffolds, and peer collaboration structures.

Figure 4 from the middle school case study provides a particularly clear illustration of differential effects across achievement levels, showing that middle-performing students benefited most from the immersive approach. This pattern suggests that immersive learning may help address the “missing middle” phenomenon often observed in educational interventions, where high and low achievers receive targeted support while middle-performing students receive less attention.

Implementation Requirements and Challenges

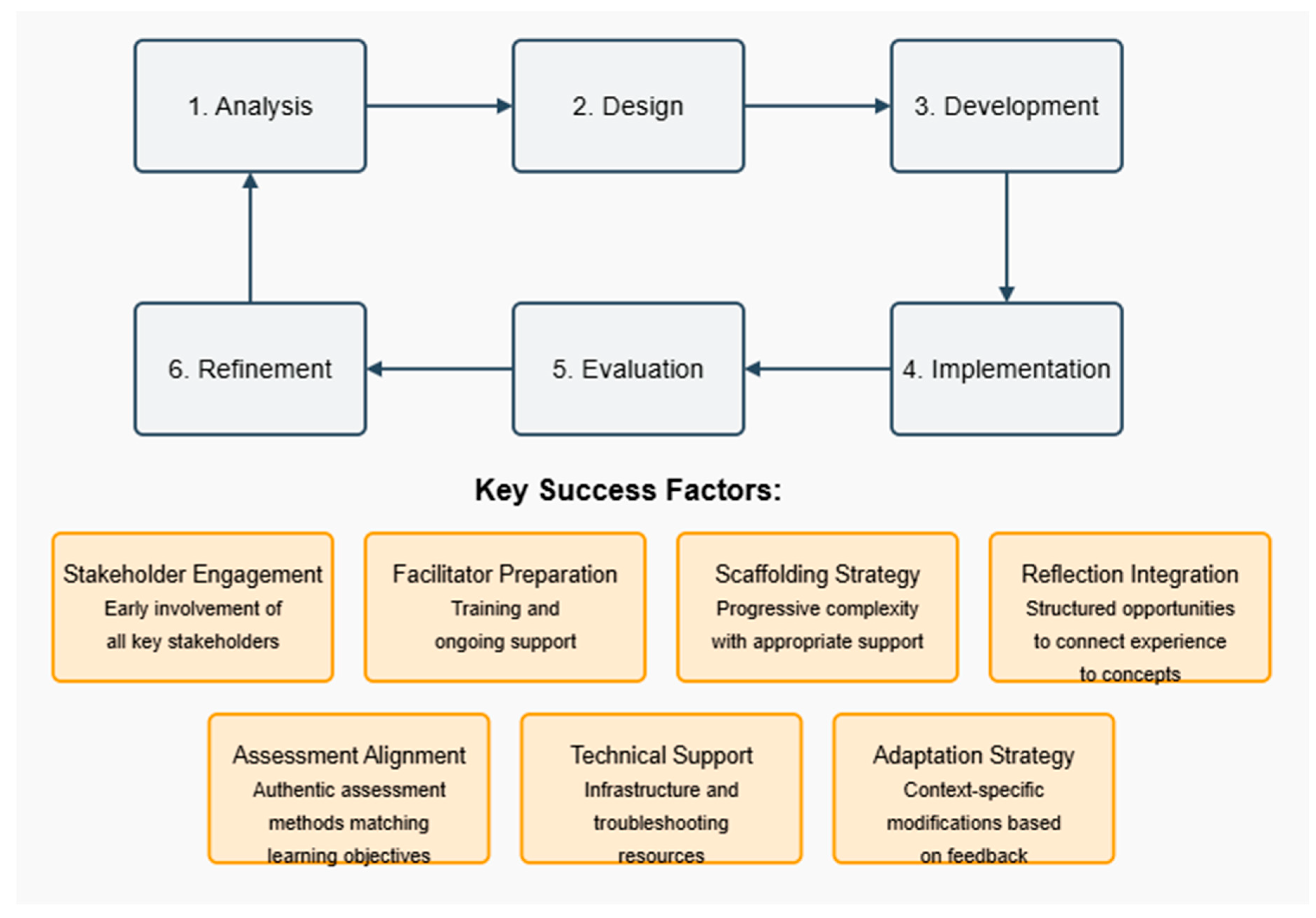

Both the meta-analysis and case studies highlight substantial resource requirements for effective implementation. The significant moderating effects of implementation duration, facilitator training, and technology integration emphasize that immersive learning quality depends heavily on implementation factors beyond the core design.

This finding has important implications for educational policy and practice, suggesting that successful adoption of immersive learning requires institutional commitment to capacity building, infrastructure development, and sustained implementation support (see

Figure 6).

Theoretical Implications

The findings extend existing theoretical frameworks in several important ways:

Refinement of the Authenticity Dilemma: This study provides empirical validation for this theoretical construct while identifying specific moderators that influence how this dilemma manifests across contexts and outcomes.

Integration with Expertise Reversal Effect: The interaction between prior knowledge and immersive learning effectiveness connects situated learning theory with cognitive load perspectives, suggesting boundary conditions for immersive approaches.

Expanded Understanding of Transfer: The strong transfer effects observed across studies support the theoretical claim that authentic contexts enhance transfer, while highlighting the importance of explicit reflection and abstraction processes within immersive experiences.

Theoretical Integration: The findings support the integrated theoretical model (

Figure 1) by demonstrating how multiple theoretical perspectives (situated cognition, cognitive apprenticeship, productive failure, cognitive load) collectively explain the complex patterns of effectiveness observed across different contexts and learner populations.

Practical Implications

The findings yield several practical implications for educational designers, practitioners, policymakers, and institutional leaders:

Alignment with Learning Goals: Immersive learning should be selected and designed based on primary learning goals, with stronger justification when transfer and motivation are priorities.

Strategic Scaffolding: Effective immersive learning requires thoughtful scaffolding that supports learning without undermining authenticity, such as just-in-time guidance, embedded tools, and structured reflection opportunities.

Implementation Planning: Successful adoption requires comprehensive planning that addresses facilitator preparation, technology infrastructure, time allocation, and institutional alignment.

Cost-Benefit Analysis Framework: Based on the findings, we propose a structured framework for assessing the potential return on investment for immersive learning implementations (

Table 7).

This framework provides a structured approach to evaluating whether immersive learning investments are likely to yield sufficient returns in specific contexts. The case studies illustrate how this analysis might be applied:

In the corporate training case, the high development cost ($420,000) was justified by substantial time-to-proficiency reductions (27 days × daily productivity value) across a large number of participants.

In the engineering ethics case, moderate development costs ($48,000) were justified by improvements in ethical reasoning transfer and professional identity development, outcomes highly valued by the engineering program.

In the middle school case, the lower development costs ($22,000) and strong effects on historical thinking made the approach cost-effective despite the substantial teacher preparation time required.

For policymakers and institutional leaders, findings suggest several important considerations:

Strategic Investment: Rather than broad implementation, strategic investment in immersive learning for specific high-priority outcomes (especially transfer and professional identity development) likely offers the highest return on investment.

Capacity Building: Sustainable implementation requires investment in educator capacity through professional development, communities of practice, and ongoing support structures.

Infrastructure Development: Technology infrastructure, physical space flexibility, and scheduling accommodations may be necessary to support immersive learning implementation.

Assessment Alignment: Traditional assessment systems may not capture the unique benefits of immersive learning, suggesting the need for expanded assessment approaches that value transfer and application.

The findings connect to broader educational trends, including competency-based education’s focus on demonstrated application, personalized learning’s attention to individual differences, and advances in educational technology that enable increasingly authentic simulations. These connections suggest that immersive learning will continue to gain prominence as education systems evolve to meet changing societal needs.

Ethical Considerations

This investigation highlights several important ethical considerations in immersive learning design, implementation, and research:

Psychological Safety

Immersive learning often involves emotional engagement and risk-taking that requires careful attention to psychological safety. In the corporate training case, participants sometimes experienced stress when facing challenging simulated leadership scenarios. Effective implementations included clear framing of the experience as a learning opportunity, debriefing protocols after emotionally charged activities, and options to modify participation if needed.

Privacy and Data Ethics

Technology-enhanced immersive environments often collect extensive data on learner behavior. The engineering ethics case raised concerns about data privacy in the virtual stakeholder interview system, which was addressed through clear consent procedures, anonymized data storage, and transparency about data usage. Educational leaders implementing immersive learning should develop explicit policies regarding data collection, storage, usage, and sharing.

Equity and Access

The middle school case highlighted significant concerns about equitable access to immersive learning opportunities. Students with limited technology access at home were disadvantaged when activities extended beyond class time. Successful implementation required providing alternative access options (extended lab hours, paper alternatives) and careful consideration of technology requirements. More broadly, the substantial resource requirements for high-quality immersive learning raise concerns about potentially exacerbating existing educational inequities if implementation is concentrated in well-resourced settings.

Cultural Sensitivity

Immersive learning often involves role-play, perspective-taking, and engagement with diverse viewpoints. The historical understanding case revealed the importance of cultural sensitivity when engaging students with historically marginalized identities in civil rights history. Effective implementation required teacher preparation for facilitating potentially sensitive discussions, consultation with community members, and thoughtful framing of historical contexts.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of this study suggest directions for future research:

Long-term Outcomes: Few studies in the meta-analysis measured outcomes beyond immediate post-tests. Future research should examine the durability of immersive learning effects through longitudinal designs.

Implementation Variability: While implementation features were documented as moderators, more detailed analysis of implementation quality and fidelity would further clarify the conditions for effectiveness.

Domain Specificity: The case studies covered diverse domains, but systematic investigation of how immersive learning effectiveness varies across subject areas would enhance design principles.

Equity Dimensions: Both the meta-analysis and case studies identified potential concerns about differential access and effectiveness. Future research should explicitly examine how immersive learning can be designed for equity.

Measurement Challenges: The field would benefit from development of validated instruments specifically designed to assess the unique outcomes of immersive learning, particularly complex transfer and identity development.

Cost-Effectiveness Comparisons: More rigorous comparative studies of cost-effectiveness relative to other educational interventions would inform strategic investment decisions.

Integrative Approaches: Further research should examine how immersive learning can be effectively integrated with direct instruction to maximize benefits across all outcome types. The moderate knowledge acquisition effects suggest that hybrid approaches might be particularly promising.

Conclusion

This mixed-methods investigation demonstrates that immersive learning, when thoughtfully designed and implemented, offers advantages over traditional instruction for developing transferable knowledge, complex skills, and intrinsic motivation. The effect sizes observed in the meta-analysis (g = 0.38 for knowledge, g = 0.61 for transfer, g = 0.67 for motivation) represent educationally meaningful impacts, while the case studies illustrate practical implementation strategies across diverse contexts.

However, the findings also highlight important nuances often overlooked in discussions of immersive learning. The significant moderating effects of implementation features, individual characteristics, and the authenticity-guidance balance emphasize that effectiveness depends heavily on how, for whom, and under what conditions immersive learning is implemented.

Immersive learning connects to broader trends in educational practice and technology, including competency-based education’s focus on demonstrated application, personalized learning’s attention to individual differences, and advances in educational technology that enable increasingly authentic simulations. These connections suggest that immersive learning will continue to gain prominence as education systems evolve to meet changing societal needs.

As educational institutions and organizations increasingly recognize the limitations of traditional instruction for developing the adaptive expertise needed in today’s complex environments, immersive learning will continue to gain prominence. The challenge lies not in blindly advocating for immersion, but in developing the design expertise, evidence base, and implementation capacity to leverage these approaches effectively.

For researchers, these findings suggest the need for more nuanced investigation of implementation factors, individual differences, and long-term outcomes. For practitioners, the results provide empirical guidance for strategic decision-making about when and how to implement immersive approaches for maximum impact. For policymakers and educational leaders, the findings highlight the importance of strategic investment, capacity building, and assessment alignment to support effective implementation.

By addressing both theoretical and practical dimensions of immersive learning, this research contributes to the ongoing transformation of educational practice to better prepare learners for complex, rapidly changing environments.

Appendix A: Meta-Analysis Coding Protocol

Study Identification and Screening Form

Citation Information:

Study ID: [AUTO-GENERATED]

Authors: __________

Year: __________

Title: __________

Journal/Source: __________

Volume/Issue/Pages: __________

Inclusion Criteria Checklist:

Published between January 2010 and December 2024

Peer-reviewed publication

Experimental or quasi-experimental design with comparison group

K-12, higher education, or professional training context

Measures at least one target outcome (knowledge, transfer, or motivation)

Sufficient statistical information for effect size calculation

English language publication

Decision:

Include

-

Exclude

- ○

Reason for exclusion: __________

Study Coding Form

Study Characteristics:

Sample size (treatment): __________

Sample size (control): __________

Total sample size: __________

-

Educational context:

- ○

K-12 Education

- ○

Higher Education

- ○

Professional Training

Subject domain: __________

Participant age range: __________

Country: __________

-

Study design:

- ○

True experimental (random assignment)

- ○

Quasi-experimental (non-random assignment)

Attrition rate (%): __________

Study quality rating (1-5): __________ [Based on standardized quality assessment tool]

Intervention Characteristics:

-

Type of immersive approach:

- ○

Game-based learning

- ○

Simulation-based learning

- ○

Cognitive apprenticeship

- ○

Epistemic game

- ○

Other: __________

Duration (weeks): __________

Total instruction time (hours): __________

Technology use (1-5 scale): __________ [1=minimal to 5=extensive]

Degree of authenticity (1-5 scale): __________ [1=low to 5=high]

Level of guidance (1-5 scale): __________ [1=minimal to 5=extensive]

-

Implementation setting:

- ○

Classroom/formal learning environment

- ○

Laboratory setting

- ○

Online/distance learning

- ○

Workplace

- ○

Other: __________

Facilitator training (hours): __________

Key design features (open text): __________

Comparison Condition:

Outcome Measures:

-

Knowledge acquisition:

- ○

Measure description: __________

- ○

Reliability coefficient (if reported): __________

- ○

-

Timing of measurement:

- ■

Immediate

- ■

Delayed (specify timeframe): __________

- ○

-

Effect size data:

- ■

Treatment group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Control group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Test statistic (t, F, etc.): __________

- ■

p-value: __________

- ■

Calculated effect size (Hedge’s g): __________

- ■

Standard error: __________

-

Transfer:

- ○

Measure description: __________

- ○

-

Transfer type:

- ■

Near transfer

- ■

Far transfer

- ○

Reliability coefficient (if reported): __________

- ○

-

Timing of measurement:

- ■

Immediate

- ■

Delayed (specify timeframe): __________

- ○

-

Effect size data:

- ■

Treatment group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Control group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Test statistic (t, F, etc.): __________

- ■

p-value: __________

- ■

Calculated effect size (Hedge’s g): __________

- ■

Standard error: __________

-

Motivation:

- ○

Measure description: __________

- ○

-

Motivation dimension:

- ■

Interest

- ■

Self-efficacy

- ■

Value

- ■

Engagement

- ■

Other: __________

- ○

Reliability coefficient (if reported): __________

- ○

-

Timing of measurement:

- ■

Immediate

- ■

Delayed (specify timeframe): __________

- ○

-

Effect size data:

- ■

Treatment group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Control group (M, SD, n): __________

- ■

Test statistic (t, F, etc.): __________

- ■

p-value: __________

- ■

Calculated effect size (Hedge’s g): __________

- ■

Standard error: __________

Moderator Variables:

-

Learner characteristics:

-

Prior knowledge level:

- ■

Low

- ■

Medium

- ■

High

- ■

Mixed

- ■

Not reported

- ○

Self-regulation skills (if measured): __________

- ○

Other individual differences measured: __________

-

Implementation features:

- ○

Implementation fidelity (1-5 scale): __________ [1=low to 5=high]

- ○

Level of teacher/facilitator involvement (1-5 scale): __________ [1=low to 5=high]

- ○

Technology integration quality (1-5 scale): __________ [1=low to 5=high]

Additional Notes:

Key findings reported by authors: __________

Limitations reported by authors: __________

Coder comments: __________

Appendix B: Case Study 1 Research Instruments

Case Study 1: Corporate Sales Leadership Training

Pre-implementation Assessment Protocol

Organizational Context Analysis:

Current sales leadership training approaches

Identified performance gaps

Organizational readiness for immersive learning

Technology infrastructure assessment

Budget and resource constraints

Stakeholder Interview Guide:

Leadership Interviews (30-45 minutes)

What are the primary challenges your sales leaders face when transitioning into leadership roles?

What knowledge, skills, and attitudes are most critical for successful sales leadership?

How would you describe the effectiveness of current training approaches?

What metrics do you currently use to evaluate sales leadership performance?

What expectations do you have for a new immersive training approach?

What concerns do you have about implementing an immersive learning approach?

What resources (time, budget, personnel) can be allocated to this initiative?

Current Sales Managers Interviews (30-45 minutes)

Describe your experience transitioning into your leadership role.

What were the most challenging aspects of becoming a sales leader?

How did previous training prepare you for your role? What was missing?

What scenarios or situations would you want new leaders to practice before taking on the role?

How comfortable are you with technology-enhanced learning approaches?

What support would you need to participate in an immersive learning experience?

Training Needs Analysis Survey:

Rate the importance of developing competency in each area (1=not important, 5=extremely important):

Strategic account planning

Sales team coaching and development

Performance management

Pipeline management

Cross-functional collaboration

Customer relationship management

Business acumen and financial analysis

Change management

Virtual team leadership

Negotiation strategy

Rate your current proficiency in each area (1=novice, 5=expert)

[Same 10 items]

Open-ended questions:

What situations do you find most challenging in your sales leadership role?

What resources or support would help you become more effective?

What would an ideal sales leadership development program include?

Implementation Measurement Instruments

Leadership Competency Assessment Tool:

Assessment dimensions (1-5 scale with behavioral anchors):

Sample item - Coaching and Development:1 = Provides minimal feedback to team members

3 = Provides regular feedback and some development opportunities

5 = Creates comprehensive development plans, provides actionable feedback, and actively supports growth

Simulation Engagement Tracking:

Time spent in simulation (total and by module)

Decision points encountered and choices made

Resources accessed during simulation

Help requests and system support utilized

Completion rate and progression pace

Post-Module Reflection Prompts:

What was the most challenging decision you faced in this module?

How did you approach this challenge and what informed your decision?

What would you do differently if faced with a similar situation in the future?

How does this experience connect to your current or future role?

What support or resources would help you apply these lessons in your work?

Post-Training Survey:

Experience rating (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree):

The simulation scenarios were realistic and relevant to my role

I was able to apply my existing knowledge in meaningful ways

The feedback I received helped me improve my approach

The experience challenged me to think differently about leadership

I feel more confident in my ability to handle similar situations

The technology enhanced rather than distracted from my learning

The coaching support enhanced my learning experience

I would recommend this training to colleagues

Open-ended questions:

What aspects of the training were most valuable to you?

What aspects could be improved?

How do you plan to apply what you’ve learned?

What additional support would help you implement these skills?

6-Month Follow-up Performance Tracking:

Time to productivity metrics (days to achievement of performance standards)

Team performance indicators (sales results, conversion rates, etc.)

Manager evaluation of leadership effectiveness (standardized assessment)

Team member feedback on leadership (360° assessment)

Self-reported application of training (structured interview)

Qualitative Interview Protocol (Post-Implementation)

Participant Interviews (45-60 minutes):

Describe your overall experience with the immersive training program.

How did the simulation compare to real-world leadership challenges you’ve encountered?

Which aspects of the simulation most effectively prepared you for your role?

How has your approach to leadership changed as a result of this experience?

What specific situations have you handled differently based on what you learned?

What aspects of the experience have been most valuable in your daily work?

What additional scenarios or elements would have enhanced your learning?

How did the technology affect your learning experience?

How did the coaching component contribute to your development?

What recommendations would you make for improving the program?

Supervisor Interviews (30-45 minutes):

What changes have you observed in the participant’s leadership approach?

How would you compare the effectiveness of participants who completed this training versus previous approaches?

What skills or competencies seem to have been most influenced by the training?

Have you observed any challenges in applying the learning?

How has the training affected team performance and dynamics?

What organizational factors have supported or hindered application of the learning?

What recommendations would you make for improving the program?

Implementation Cost and Resource Tracking Form:

Development costs (itemized by category)

Technology infrastructure costs

Facilitator/coach time allocation and costs

Participant time allocation and opportunity costs

Ongoing support and maintenance costs

Total cost per participant

Appendix C: Case Study 2 Research Instruments

Case Study 2: Engineering Ethics in Higher Education

Quasi-Experimental Design Protocol

Participant Assignment:

Assignment method: Section-based assignment (two course sections)

Control for selection bias: Demographic and academic background survey

Sample size calculation: Power analysis for medium effect (d=0.5), power=0.8, alpha=0.05

Experimental Group (Epistemic Game Approach):

4-week immersive learning module

Engineering ethics investigation scenario

Virtual stakeholder interviews

Document analysis activities

Collaborative ethical analysis

Professional framework application

Final ethical recommendations

Control Group (Case Study Approach):

4-week traditional ethics instruction

Same learning objectives and content

Traditional case study analysis

Lecture-based ethical framework instruction

Individual written ethical analyses

Class discussions of ethical dilemmas

Final ethics position papers

Implementation Fidelity Checklist:

Core epistemic game elements present

Appropriate facilitation provided

Technology functioning properly

Authentic ethical frameworks applied

Collaborative processes supported

Reflection activities completed

Assessment aligned with learning approach

Assessment Instruments

Engineering Ethical Reasoning Instrument (Pre/Post):

-

25-item assessment measuring:

- ○

Recognition of ethical issues (5 items)

- ○

Stakeholder perspective-taking (5 items)

- ○

Application of ethical frameworks (5 items)

- ○

Ethical decision-making process (5 items)

- ○

Justification of ethical positions (5 items)

Format: Scenario-based questions with constructed responses

Scoring: Standardized rubric (1-5 scale per dimension)

Validation: Previously validated with engineering students (α=.87)

Example item: “A senior engineer asks you to remove a safety concern from your report because addressing it would delay an important product launch. Analyze the ethical dimensions of this situation and describe how you would respond.”

Work Product Analysis Rubric:

Quality of ethical issue identification (1-5 scale)

Depth of stakeholder perspective consideration (1-5 scale)

Appropriateness of ethical framework application (1-5 scale)

Logical reasoning and analysis (1-5 scale)

Professional communication of recommendations (1-5 scale)

Consideration of consequences (1-5 scale)

Integration of technical and ethical considerations (1-5 scale)

Student Engagement Survey:

Rate your agreement with each statement (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree):

I found myself thinking about the ethical scenarios outside of class time

I was mentally engaged during the learning activities

The scenarios captured my interest

I could see the relevance of these activities to my future career

I invested significant effort in the learning activities

I enjoyed discussing ethical issues with my peers

I felt personally involved in resolving the ethical dilemmas

I wanted to perform well on the assignments

Implementation Process Documentation:

Development time log (hours by activity)

Technology development and integration costs

Facilitator training time and activities

Instructional time allocation (by activity)

Technical support requirements

Student time on task (logged in learning management system)

Focus Group Protocol

Student Focus Groups (60-90 minutes, 6-8 students per group):

Opening Questions:

Key Questions:

3. How did this approach to learning ethics compare to other educational experiences you’ve had?

4. How did engaging with virtual stakeholders affect your understanding of ethical issues?

5. What was challenging about analyzing ethical situations in this format?

6. How did collaboration with peers influence your ethical reasoning?

7. How did the immersive nature of the experience affect your engagement?

8. In what ways did this experience change how you think about ethical issues in engineering?

9. How do you anticipate applying what you’ve learned in your future work?

Closing Questions:

10. What would you change about the learning experience?

11. What additional thoughts would you like to share about learning ethics in this way?

Instructor Focus Group (60-90 minutes):

How did implementing this approach compare to previous teaching experiences?

What changes did you observe in student engagement and learning?

What challenges did you encounter in facilitating the immersive approach?

How did your role as an instructor change in this approach?

What support or resources were most helpful in implementation?

What additional support would have improved the implementation?

How sustainable is this approach for future teaching?

What modifications would you recommend for future iterations?

Appendix D: Case Study 3 Research Instruments

Case Study 3: Middle School Historical Understanding

Historical Thinking Skills Assessment

Pre/Post Assessment of Historical Thinking Skills:

-

20-item assessment measuring:

- ○

Sourcing (evaluating document origins)

- ○

Contextualization (placing events in historical context)

- ○

Corroboration (comparing multiple sources)

- ○

Historical perspective-taking

- ○

Historical significance assessment

Format: Document-based questions with constructed responses

Scoring: Standardized rubric (1-5 scale per dimension)

Validation: Previously validated with middle school students (α=.83)

Sample item: “Examine these two accounts of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. How do they differ? Why might they present different perspectives? What can we learn from comparing them?”

Student Work Product Rubric:

Historical accuracy (1-5 scale)

Use of evidence from primary sources (1-5 scale)

Consideration of multiple perspectives (1-5 scale)

Contextualization of historical events (1-5 scale)

Recognition of cause and effect relationships (1-5 scale)

Quality of historical narrative construction (1-5 scale)

Exhibition of historical empathy (1-5 scale)

Self-Efficacy and Interest Measures

Historical Thinking Self-Efficacy Scale:

Rate your confidence in your ability to (1=not at all confident, 5=extremely confident):

Analyze primary source documents

Identify biases in historical accounts

Understand historical events from multiple perspectives

Place historical events in their proper context

Evaluate the reliability of historical sources

Create evidence-based historical explanations

Recognize connections between past and present

Engage in historical debates using evidence

Historical Interest Inventory:

Rate your agreement with each statement (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree):

I enjoy learning about history

Understanding history is important to me

I am curious about how people lived in the past

I find historical debates and controversies interesting

I often wonder about the causes of historical events

I like to imagine what life was like in different time periods

I see connections between historical events and current issues

I would choose to learn more about history outside of school

Implementation Documentation

Teacher Time and Activity Log:

Preparation time (hours by activity)

Instructional time (hours by activity)

Assessment time (hours)

Collaboration time (hours)

Technology troubleshooting time (hours)

Total implementation time

Implementation Fidelity Checklist:

Technology Access and Equity Assessment:

Student technology access (home and school)

Accommodations provided for students with limited access

Technical issues encountered

Digital literacy support provided

Alternative access methods utilized

Student Engagement Tracking

Behavioral Engagement Measures:

Classroom participation rates (teacher observation protocol)

Assignment completion rates

Time on task during class activities (structured observation)

Extension activity participation

Resource access metrics (digital platform analytics)

Teacher Observation Protocol:

For each 15-minute interval, record:

Number of students actively engaged with learning materials

Number of voluntary student contributions to discussion

Number of student-initiated questions

Instances of students building on peers’ ideas

Examples of historical thinking observed

Student Reflection Journal Prompts:

What did you find most interesting about today’s historical investigation?

What questions do you still have about this historical topic?

How did examining primary sources change your understanding of events?

What was challenging about today’s historical thinking activities?

How has your approach to analyzing historical sources changed?

How does this historical topic connect to other things you’ve learned or experienced?

Teacher Interview Protocol

Mid-Implementation Interviews (30-45 minutes):

How are students responding to the cognitive apprenticeship approach?

What aspects of the implementation are working well?

What challenges have you encountered in implementation?

How are you adapting the approach to meet student needs?

What differences are you observing compared to previous instructional approaches?

What support would help improve implementation?

Post-Implementation Interviews (45-60 minutes):

How would you describe the overall impact of this approach on student learning?

What changes have you observed in students’ historical thinking skills?

How did student engagement compare to previous instructional approaches?

Which components of the cognitive apprenticeship approach were most effective?

How did the implementation affect different groups of students?

What modifications would you make in future implementations?

How sustainable is this approach within your current teaching context?

What institutional factors supported or hindered implementation?

How has this experience influenced your approach to teaching historical thinking?

What advice would you give to other teachers implementing this approach?

Appendix E: Cross-Case Analysis Protocol

Cross-Case Analysis Protocol

Implementation Factors Comparative Analysis Framework

Design Features Matrix:

Authenticity components implemented

Guidance/scaffolding approaches

Technology integration level

Content/context alignment

Assessment approach

Implementation Process Comparison:

Resource Requirements Comparison:

Development costs (standardized categories)

Technology infrastructure requirements

Personnel time allocation

Sustainability factors

Cost-effectiveness metrics

Outcome Patterns Analysis Framework

Effect Size Standardization:

Conversion of all outcome measures to comparable effect sizes

Categorization by outcome type (knowledge, transfer, motivation)

Disaggregation by learner characteristics

Qualitative Outcome Pattern Analysis:

Cross-case thematic analysis of qualitative data

Identification of common success factors

Documentation of implementation barriers

Context-specific moderating factors

Moderator Analysis Template:

Individual differences effects

Implementation quality effects

Contextual factors effects

Design feature effects

Case Synthesis Protocol

Synthesis Workshop Agenda:

Individual case presentation (key findings)

Cross-case pattern identification

Rival explanation analysis

Contextual factor discussion

Implementation principles development

Research limitations assessment

Practical implications formulation

Future research direction identification

Integration Framework:

Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings

Explanatory mechanisms identification

Boundary condition definition

Implementation guidance development

Research-to-practice translation

References

- Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

- Cheng, K. H., Yen, S. H., & Chen, J. S. (2022). Augmented reality in K-12 education: A meta-analysis of student learning effectiveness and a systematic review of implementation challenges. Computers & Education, 183, 104494.

- Chernikova, O., Heitzmann, N., Stadler, M., Holzberger, D., Seidel, T., & Fischer, F. (2020). Simulation-based learning in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 90(4), 499-541.

- Clark, D. B., Tanner-Smith, E. E., & Killingsworth, S. S. (2016). Digital games, design, and learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 79-122.

- Clark, R. E. (2007). Learning from serious games? Arguments, evidence, and research suggestions. Educational Technology, 47(3), 56-59.

- Collins, A., & Kapur, M. (2022). Cognitive apprenticeship. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (3rd ed., pp. 156-174). Cambridge University Press.

- Dede, C. (2009). Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science, 323(5910), 66-69.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. ACM Computers in Entertainment, 1(1), 1-4.

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127.

- Ifenthaler, D., & Kim, Y. J. (Eds.). (2019). Game-based assessment revisited. Springer International Publishing.

- Joksimović, S., Dowell, N., Gašević, D., Mirriahi, N., Dawson, S., & Graesser, A. C. (2023). Comprehensive analysis of automated feedback and learning analytics to enhance problem-based learning. Computers & Education, 191, 104644.

- Kallio, J. M., & Halverson, R. (2020). Distributed leadership for personalized learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(3), 371-390.

- Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23-31.

- Kapur, M., & Bielaczyc, K. (2012). Designing for productive failure. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(1), 45-83.

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

- Kuhn, S., & Weissman, S. (2023). The fidelity paradox in simulation-based medical education: A systematic review and framework. Medical Education, 57(6), 577-592.

- Merchant, Z., Goetz, E. T., Cifuentes, L., Keeney-Kennicutt, W., & Davis, T. J. (2014). Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students’ learning outcomes in K-12 and higher education: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 70, 29-40.

- Nachtigall, V., Shaffer, D. W., & Rummel, N. (2024). The authenticity dilemma: Towards a theory on the conditions and effects of authentic learning. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(4), 3483-3509.

- Radianti, J., Majchrzak, T. A., Fromm, J., & Wohlgenannt, I. (2020). A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Computers & Education, 147, 103778.

- Reich, J., Buttimer, C. J., Fang, A., Hillaire, G., Hirsch, K., Larke, L. R., Littenberg-Tobias, J., Moussapour, R. M., Napier, A., Thompson, M., & Slama, R. (2019). Scaling up behavioral science interventions in online education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(29), 14900-14905.

- Schank, R. C. (1994). Goal-based scenarios: A radical look at education. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3(4), 429-453.

- Shaffer, D. W. (2006). How computer games help children learn. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shaffer, D. W., & Resnick, M. (1999). “Thick” authenticity: New media and authentic learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 10(2), 195-216.

- Stoddard, J., Brohinsky, J., Behnke, D., & Shaffer, D. (2022). Designing epistemic games for informed civic learning. Harvard Education Press.

- Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261-292.

- Wouters, P., Van Nimwegen, C., Van Oostendorp, H., & Van Der Spek, E. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 249-265.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166-183.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).