1. Introduction

With the rapid development of information technology, education is also changing rapidly. As the virtual interactive technologies including Virtual Reality (VR) and Simulation Technology (ST), the application of VR and ST in education becomes more and more popular. In the field of education, the above-mentioned technologies provide students with immersive experiences and hands-on environment. Many researchers have proved that these technologies are effective in terms of conceptual learning, spatial learning and skill-based learning (Jian & Abu Bakar, 2024; Nshimiyimana & Ndayambaje, 2025).

However, the adoption of VR and ST in language education, particularly in non-English-speaking contexts such as China, remains limited. Traditional college English classes often face challenges such as low engagement, wide proficiency gaps, and rigid, outdated instructional practices. These issues hinder the development of students’ practical English abilities.

Although there has been a large body of researches investigating the application of VR in professional training, few have studied the pedagogical application of VR in English language education. More importantly, there is a lack of theoretical models to explain the impact of virtual technologies on learning performance through engagement and motivation (Kozorez et al., 2022)..

Therefore, this study attempts to explore the impact of virtual interaction technologies on college students’ English learning performance. Furthermore, this study attempts to explore the mediating effects of classroom participation and learning motivation. This research adopts fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in the mixed-method study to offer empirical evidence and theoretical reference for practice.

Additionally, by adopting Student Engagement Theory (Astin, 2014; Fredricks et al., 2004), and Self-Determination Theory(Deci et al., 1985) and Constructivist Learning Theory(Schott & Marshall, 2018), this study explores the mediating effects of classroom participation and learning motivation on the impact of virtual interaction technologies on college students’ English learning performance.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

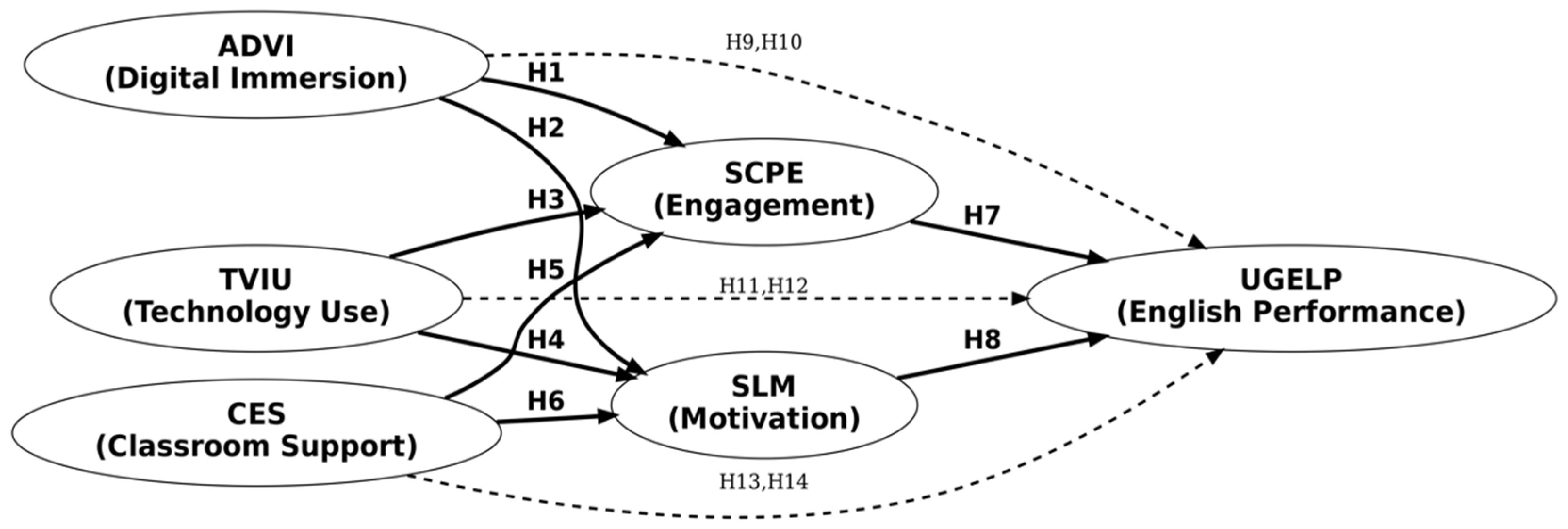

This study is grounded in three complementary theoretical perspectives that jointly explain how virtual interaction technology can enhance English language learning performance. Student Engagement Theory (Astin, 2014; Fredricks et al., 2004) emphasizes the multidimensional nature of student engagement, encompassing behavioral, emotional, and cognitive involvement. This theory supports the inclusion of student classroom participation (SCPE) as a key mediating mechanism. In parallel, Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) highlights the role of intrinsic motivation in promoting sustained academic effort and performance, reinforcing the relevance of student learning motivation (SLM) in the conceptual model. Additionally, Constructivist Learning Theory (Schott & Marshall, 2018) advocates for experiential, learner-centered environments, validating the use of immersive technologies such as VR and simulation tools in modern English classrooms. These theoretical perspectives collectively justify the proposed research framework and inform the hypothesized pathways between virtual interaction, student engagement, and learning outcomes.

2.2. Literature Review of Key Constructs

2.2.1. Application of Virtual Interaction Technology (ADVI)

ADVI refers to the extent and depth to which immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and simulations are applied in English language teaching. This includes the variety of digital content used, the frequency of student interaction with these technologies, and their alignment with pedagogical goals (Liu et al., 2022; Monteiro & Ribeiro, 2020). According to Constructivist Learning Theory, learning is most effective when students actively construct knowledge through authentic and immersive experiences. Empirical studies confirm that students exposed to high levels of ADVI demonstrate greater attention, engagement, and interest in English learning tasks (Zhai et al., 2023).Thus, we propose:

H1: ADVI positively affects students’ classroom engagement (SCPE).

H2: ADVI positively affects students’ learning motivation (SLM).

2.2.2. Teachers’ Virtual Interaction Technology Usage (TVIU)

TVIU refers to the degree to which teachers proficiently use virtual tools in their instructional design, classroom delivery, and student interaction. Effective use of VIT not only enhances interactivity but also shapes students' perceptions of technology-enhanced learning (Lin et al., 2024). Grounded in Student Engagement Theory, teacher practices serve as environmental stimuli that affect learners’ emotional and behavioral responses. Research indicates that when teachers actively embed VR or simulation elements, students demonstrate higher motivation and collaborative learning behavior (Kamaliasari & Nurbianta, 2022). Hence, we hypothesize:

H3: TVIU positively affects SCPE.

H4: TVIU positively affects SLM.

2.2.3. Classroom Environment Support (CES)

CES encompasses the infrastructural and psychological support provided by institutions for VIT integration. This includes accessibility of devices, platform reliability, internet connectivity, and overall classroom atmosphere conducive to experimentation and digital engagement (Y. Huang et al., 2022). From the lens of SDT, a supportive environment enhances students’ sense of competence and autonomy. A well-supported classroom significantly improves students’ willingness to participate and stay motivated. Therefore:

H5: CES positively affects SCPE.

H6: CES positively affects SLM.

2.2.4. Students’ Classroom Participation Engagement (SCPE)

SCPE involves students’ active involvement in classroom activities such as discussions, group work, and interactive tasks. It is a behavioral expression of engagement and is shaped by external stimuli like technology and teacher input (Fredricks et al., 2004) High SCPE is associated with increased language production, task completion, and overall learning performance (Guo et al., 2021). Accordingly:

H7: SCPE positively affects UGELP.

2.2.5. Students’ Learning Motivation (SLM)

SLM denotes the intrinsic desire of students to learn English, encompassing interest, perseverance, and self-directed effort. Self-Determination Theory posits that intrinsic motivation is crucial for sustained academic engagement and success (Deci & Ryan, 1985). In language learning contexts, motivation has been shown to directly influence both classroom behavior and academic performance (Fugate et al., 2004). We therefore hypothesize:

H8: SLM positively affects UGELP.

2.2.6. Mediating Effects of SCPE and SLM

Drawing upon Student Engagement Theory (Fredricks et al., 2004), classroom participation engagement (SCPE) is posited to mediate the relationship between virtual interaction factors (ADVI, TVIU, CES) and English learning outcomes. Engaged students are more likely to translate technological opportunities into academic performance improvements.

Concurrently, according to Self-Determination Theory (Deci et al., 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000), student learning motivation (SLM) serves as a critical motivational channel linking educational environments to outcomes. Prior research (Pan, 2023) has confirmed that supportive technological environments enhance intrinsic motivation, which subsequently promotes better learning achievement.

Therefore, SCPE and SLM are hypothesized as key mediators connecting virtual interaction technologies to UGELP. These mediating pathways reflect both behavioral and motivational channels through which instructional design impacts learning outcomes:

H9: SCPE mediates the relationship between ADVI and UGELP.

H10: SLM mediates the relationship between ADVI and UGELP.

H11: SCPE mediates the relationship between TVIU and UGELP.

H12: SLM mediates the relationship between TVIU and UGELP.

H13: SCPE mediates the relationship between CES and UGELP.

H14: SLM mediates the relationship between CES and UGELP.

2.3. Summary of Prior Research and Gaps

Recent empirical research has demonstrated the pedagogical potential of virtual interaction technologies in various aspects of English language instruction. For instance, Zhai (2023) showed that the use of VR in English writing classes significantly improved students’ composition skills and learning motivation by simulating authentic writing contexts. Similarly, Yan et al. (2024) reported enhancements in oral fluency and confidence when students practiced speaking through immersive VR platforms. In a broader application, Pan (2023) investigated virtual tools in integrated English curricula and found improvements in both linguistic accuracy and classroom participation.

Despite these advances, prior studies tend to rely heavily on quantitative surveys and often overlook the configurational nature of causal relationships In particular, the combined roles of environmental support and teacher practices remain underexplored. Furthermore, few studies have adopted mixed-method strategies to reveal both linear relationships and non-linear causal combinations(Pappas & Woodside, 2021).

This study integrates Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to address these limitations. This dual-method approach not only validates hypothesized pathways but also uncovers multiple, equally effective configurations that lead to high English learning performance(Furnari et al., 2020). By doing so, the study contributes both theoretical depth and methodological innovation to the understanding of how virtual interaction technologies shape student outcomes in language education.

2.4. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

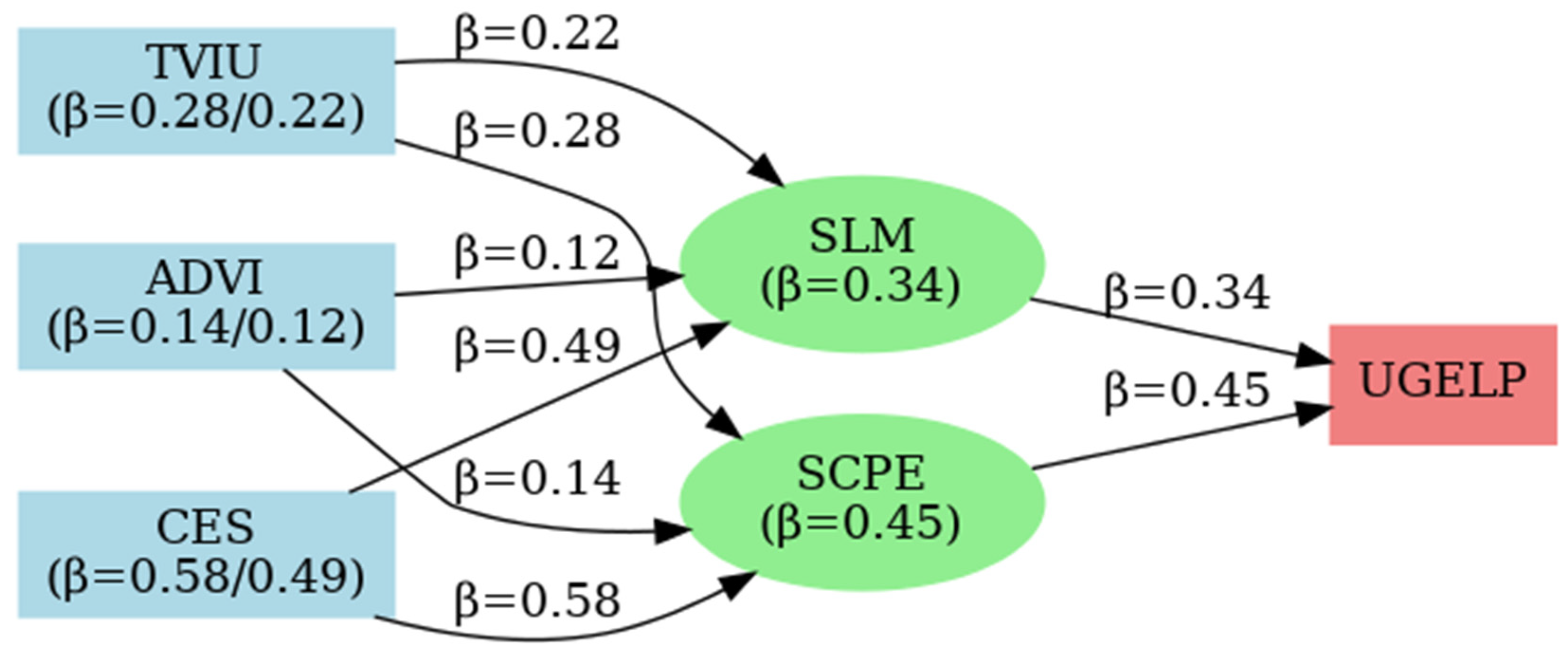

According to

Figure 1, it illustrates the conceptual model, incorporating the key constructs and corresponding hypotheses. Building upon the theoretical framework and hypothesized relationships presented above, the next chapter details the research methodology, including the research design, measurement instruments, sampling strategies, and analytical techniques—specifically, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)—employed to examine the proposed model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Distribution

To investigate the variables influencing student engagement in university English classrooms, a structured questionnaire was developed based on a comprehensive literature review. Initially, the instrument was distributed to frontline university English teachers to collect expert insights on the factors most likely to enhance or hinder student participation. Based on their feedback, the questionnaire was refined to improve clarity and content validity.

The finalized questionnaire was then administered to undergraduate students who had experience using virtual interaction technologies (VIT) in English classroom settings. The aim was to collect quantitative data that could capture students’ perceptions of VIT implementation, classroom engagement, learning motivation, and English learning performance. This procedure ensured the reliability and authenticity of the data collected, laying a solid empirical foundation for subsequent structural modeling analysis.

3.2. Measurement Scale

The questionnaire evaluates multiple dimensions related to the use of virtual interactive technology in English learning environments. These include students' awareness and access to virtual tools (ADVI)(Monteiro & Ribeiro, 2020), the proficiency and instructional application of such technologies by teachers (TVIU) (Harmawati et al., 2024)and the broader school environment's support for virtual learning through equipment, training, and resources (CES)(L. Huang et al., 2022). It also measures students’ classroom participation and collaboration (SCPE) (Lin et al., 2024; Molotsı, 2020),their intrinsic motivation and commitment to learning English (SLM) (Fugate et al., 2004; Guo et al., 2021), and their actual English language performance and ability to integrate technology into their learning (UGELP) (Holmes, 2013; Portuguez-Castro & Santos Garduño, 2024). Each dimension is grounded in prior literature and assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree".

The questionnaire uses a Likert 5-point scale for measurement, ranging from "Strongly Agree" (5 points) to "Strongly Disagree" (1 point).

3.3. Data Collection and Sampling

The study adopted a two-phase survey approach comprising a pre-test and a formal survey. In August 2024, a pre-test was conducted to examine the scale's reliability and validity. Using SPSS software, the analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.937, a KMO value of 0.712, and a Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity with p < 0.001—indicating high internal consistency and construct validity.

The formal survey was conducted across multiple sessions with university students in Guangzhou who had experience using VIT in their English courses. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, and 416 valid responses were collected, resulting in an effective response rate of 92.44%. The demographic breakdown of respondents showed a balanced representation by gender (53.1% male, 46.9% female) and a majority in the 18–21 age group (56.7%). The distribution of local (52.2%) and non-local students (47.8%) also reflected a diverse and representative sample of the target population.

3.4. fsQCA Analytical Method

In addition to the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), this study employed fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to explore alternative causal pathways that lead to high levels of comprehensive English learning performance (UGELP). All six constructs (ADVI, TVIU, CES, SCPE, SLM, UGELP) were calibrated into fuzzy-set scores using the direct method. The 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of each variable were used as thresholds for full non-membership, crossover point, and full membership, respectively. Calibration and analysis were conducted using fsQCA 3.0 software.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics for all latent variables are shown in Table 1. The means of the six core constructs ranged from 3.20 to 3.38 (on a 5-point Likert scale), suggesting generally positive perceptions of virtual interaction technologies and student engagement. Standard deviations ranged from 0.77 to 0.81, indicating moderate variation across participants.

| Variable |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

| ADVI |

3.32 |

0.77 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

| TVIU |

3.27 |

0.78 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

| CES |

3.37 |

0.78 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

| SCPE |

3.38 |

0.81 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

| SLM |

3.20 |

0.78 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

| UGELP |

3.20 |

0.78 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

4.2. Measurement Modeling

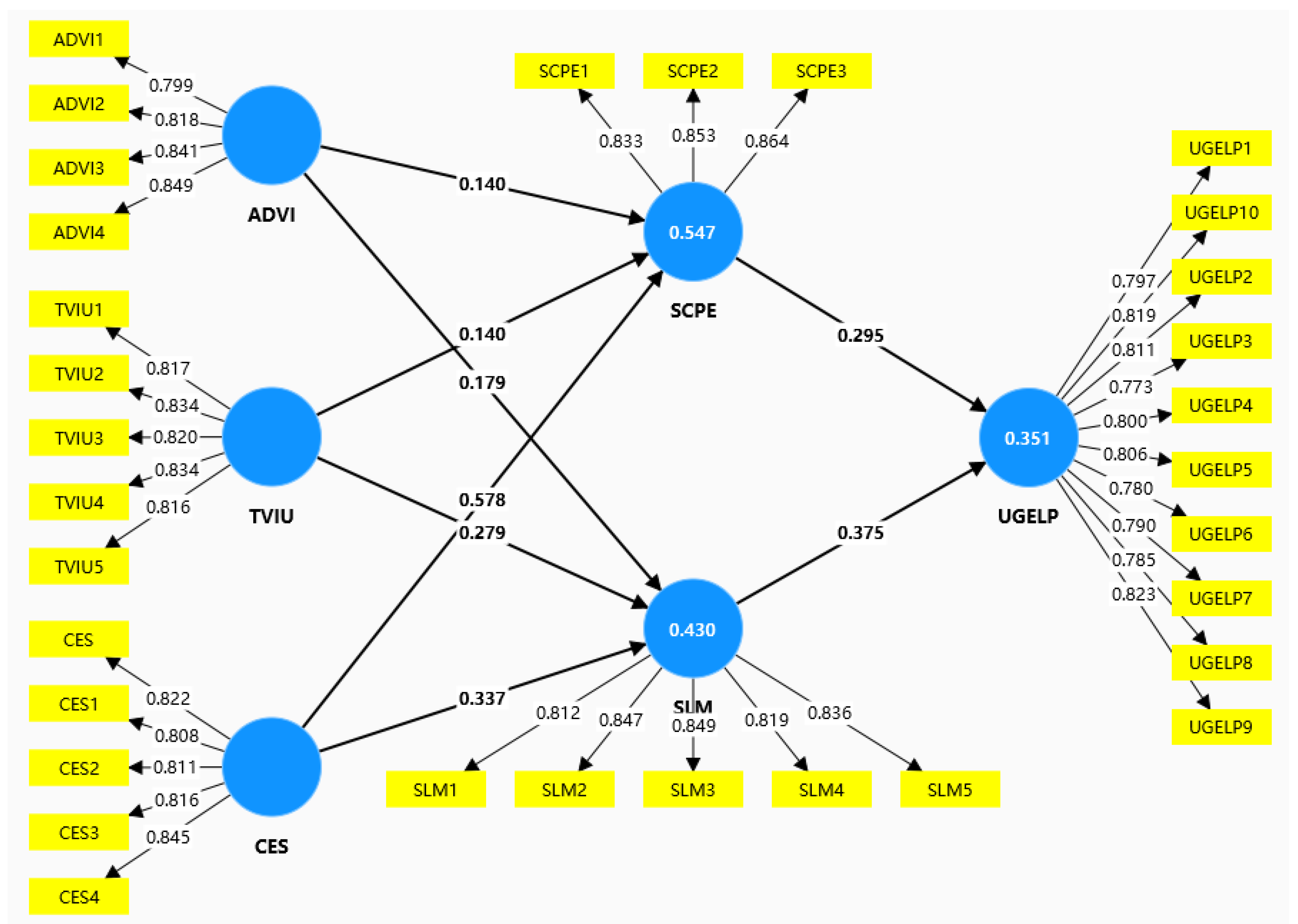

A two-step structural equation modeling analysis method was used based on a two-step approach. The first step utilizes SmartPLS 4.1 statistical software to carefully examine the measurement properties of the measurement model. In this process, Bootstraping was applied to converge after the 3rd iteration. The test results show that in terms of reliability, the ɑ coefficients of all the latent factors exceeded the criterion of 0.7, ranging from 0.808 to 0.937, indicating that the measurement model possesses good internal consistency. The constituent reliability (CR) index values were all above 0.8, with a minimum value of 0.883 and a maximum value of 0.942, indicating that the measurement model has a good level of internal consistency and constituent reliability. Regarding the convergent validity of the measurement model, the standardized loading values of the observed variables of each latent factor were all above 0.7, ranging from 0.808 to 0.938, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values of each latent factor were all greater than 0.5, with the minimum value of 0.638 and the maximum value of 0.722, which indicated that the measurement model had a strong convergent validity (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Convergent validity of measurement scales.

Table 1.

Convergent validity of measurement scales.

| Latent variable |

Entry |

Factor loading |

CR |

AVE |

Cronbach's Alpha |

| ADVI |

ADVI1 |

0.799 |

|

|

|

| ADVI2 |

0.818 |

|

|

|

| ADVI3 |

0.841 |

0.850 |

0.684 |

0.846 |

| ADVI4 |

0.849 |

|

|

|

| TVIU |

TVIU1 |

0.817 |

|

|

|

| TVIU2 |

0.834 |

|

|

|

| TVIU3 |

0.820 |

0.883 |

0.679 |

0.882 |

| TVIU4 |

0.834 |

|

|

|

| TVIU5 |

0.816 |

|

|

|

| CES |

CES1 |

0.808 |

|

|

|

| CES2 |

0.811 |

|

|

|

| CES3 |

0.816 |

0.879 |

0.673 |

0.879 |

| CES4 |

0.845 |

|

|

|

| CES5 |

0.822 |

|

|

|

| SCPE |

SCPE1 |

0.833 |

|

|

|

| SCPE2 |

0.853 |

0.808 |

0.722 |

0.808 |

| SCPE3 |

0.864 |

|

|

|

| SLM |

SLM1 |

0.812 |

|

|

|

| SLM2 |

0.847 |

|

|

|

| SLM3 |

0.849 |

0.889 |

0.693 |

0.889 |

| SLM4 |

0.819 |

|

|

|

| SLM5 |

0.836 |

|

|

|

| UGELP |

UGELP1 |

0.797 |

|

|

|

| UGELP2 |

0.819 |

|

|

|

| UGELP3 |

0.811 |

|

|

|

| UGELP4 |

0.773 |

|

|

|

| UGELP5 |

0.800 |

0.938 |

0.638 |

0.937 |

| UGELP6 |

0.806 |

|

|

|

| UGELP7 |

0.780 |

|

|

|

| UGELP8 |

0.790 |

|

|

|

| UGELP9 |

0.785 |

|

|

|

| UGELP10 |

0.823 |

|

|

|

For the assessment of discriminant validity, the judgment was based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion. By comparing the square root of the AVE values of each latent factor with the correlation coefficients between them and the other latent factors, it can be seen that the former is always greater than the latter (see Table 3). This result clearly confirms that the measurement model possesses good discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Discriminative validity of measurement scales.

Table 2.

Discriminative validity of measurement scales.

| Discriminant Validity |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. ADVI |

0.827 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. CES |

0.471 |

0.820 |

|

|

|

|

| 3. SCPE |

0.507 |

0.705 |

0.850 |

|

|

|

| 4. SLM |

0.526 |

0.544 |

0.557 |

0.832 |

|

|

| 5. TVIU |

0.678 |

0.441 |

0.489 |

0.548 |

0.824 |

|

| 6. UGELP |

0.700 |

0.442 |

0.504 |

0.540 |

0.745 |

0.798 |

4.3. Structural Model

When evaluating the fitness level of a structural model, the fitness level of a structural model generally requires an SRMR ≤ 0. 08,. In this study, the SRMR value we obtained was 0. 068, and this result indicates that our model reached the fitness level. By analyzing the path coefficients, we found that the application of virtual interactive technology had a significant positive impact on SCPE (β = 0.140, p < 0.1), which supports our first hypothesis (H1). Also, the application of virtual interactive technology significantly enhanced SLM (β = 0.179, p< 0.1), thus validating the second hypothesis (H2). Teachers' ability to utilize virtual interactive technology likewise had a significant positive effect on SCPE (β = 0.140, p < 0.01), which confirmed the third hypothesis (H3). This competency of teachers was also shown to significantly influence SLM (β = 0.279, p < 0.1), which is consistent with the fourth hypothesis (H4). Regarding CES, the study revealed that it had a significant positive effect on both SCPE (β = 0.578, p < 0.01) and motivation to learn (β = 0.337, p < 0.01), which supported the fifth (H5) and sixth hypotheses (H6), respectively. SCPE (β = 0.295, p < 0.01) and motivation to learn (β = 0.375, p < 0.01) both significantly contributed to their overall performance in the English classroom, and these two findings validated the seventh (H7) and eighth (H8) hypotheses, respectively, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Model path analysis results.

Table 3.

Model path analysis results.

| Hypothetical |

Pathway |

The coefficient β |

p-value |

95% confidence interval |

| H1 |

ADVI→SCPE |

0.140 |

0.003 |

[0.048,0.233] |

| H2 |

ADVI→SLM |

0.179 |

0.001 |

[0.071,0.284] |

| H3 |

TVIU→SCPE |

0.140 |

0.000 |

[0.048,0.230] |

| H4 |

TVIU→SLM |

0.279 |

0.000 |

[0.177.0.383] |

| H5 |

CES→SCPE |

0.578 |

0.000 |

[0.512,0.641] |

| H6 |

CES→SLM |

0.337 |

0.000 |

[0.245,0.421] |

| H7 |

SCPE→UGELP |

0.295 |

0.002 |

[0.204,0.384] |

| H8 |

SLM→UGELP |

0.375 |

0.000 |

[0.290,0.461] |

From the causality diagram of the research model (

Figure 2), it can be seen that the explanatory power of ADVI, TVIU, and CES is 54.7% for SCPE and 43.0% for SLM; and the explanatory power of SCPE and SLM for UGELP is 35.1%, which indicates that the explanatory power of the model is good. In addition, ADVI, TVIU, CES and other variables affect UGELP through the mediating variables SCPE and SLM, and the total effect values of each dimension are as follows: ADVI is 0. 020, TVIU is 0. 041, CES is 0. 589. The analysis reveals that CES is the factor with the highest effect value, which suggests that CES should be emphasized in the enhancement of UGELP; in terms of the mediating variable aspect, the effect value of SLM ( 0. 375) is larger than that of SCPE ( 0. 295), which indicates that students' overall performance in English classroom is more influenced by learning motivation.

4.4. Visual Model of SEM Pathways

Figure 2 illustrates the structural equation model used in this study, including all latent variables, their directional relationships, and standardized path coefficients. The model clearly presents the significant influences of virtual interactive technology application, teacher proficiency, and classroom environment on student engagement, motivation, and ultimately, English learning performance.

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Model with Standardized Coefficients (β).

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Model with Standardized Coefficients (β).

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Direct Effects

In the study of this paper, we used SEM to investigate how virtual interactive technology affects college students' engagement and their overall performance in the English classroom. Through modeling analysis, we obtained the direct effects among the variables, which revealed the causal relationships among the key variables such as ADVI, TVIU, CES, SCPE, and SLM. First, ADVI had a significant direct positive effect on SCPE (β = 0.140, p < 0.01). This result supports our hypothesis H1 that the application of virtual interactive technologies can enhance SCPE.The results suggest that students are more willing to actively participate in classroom activities when virtual reality and virtual simulation technologies are introduced into university English classrooms. By providing rich learning resources and realistic learning situations, these technologies effectively stimulate students' learning interest and initiative, which in turn enhances their classroom participation. Second, ADVI also significantly enhanced SLM (β = 0.179, p < 0.01), validating Hypothesis H2.These technologies enhanced students' motivation and sense of accomplishment by creating interactive and practical learning environments that enabled them to practice language in simulated real-life scenarios.TVIU likewise had a significant and direct positive effect on SCPE (β = 0.140, p < 0.01), confirming Hypothesis H3. Teachers' ability to skillfully manipulate virtual interactive technologies and effectively integrate them into their teaching has a direct impact on students' learning interest and engagement. Teachers with strong skills in the use of virtual interactive technologies are able to create a more active and interesting classroom atmosphere that stimulates student engagement. In addition, TVIU also significantly affected SLM (β = 0.279, p < 0.01), consistent with Hypothesis H4. Teachers' ability to use technology is not only related to the quality of teaching, but also can motivate students to learn and make them more willing to invest time and energy in learning. Regarding CES, our study found that it had a significant direct positive effect on both SCPE (β = 0.578, p < 0.01) and learning motivation (β = 0.337, p < 0.01), supporting hypotheses H5 and H6, respectively.A supportive classroom environment, including physical comfort and quietness, and the ease of use and stability of the virtual learning platform, enables students to be more focused on learning, increase motivation to participate in the classroom, and stimulate their learning motivation. Finally, both SCPE (β = 0.295, p < 0.01) and motivation to learn (β = 0.375, p < 0.01) significantly contributed to their overall performance in the English classroom, validating Hypotheses H7 and H8. Students' active participation and strong motivation to learn were the key factors that contributed to their excellent academic achievement and good overall performance.

5.2. Analysis of Mediating Effects

In order to explore the mediating role played by students' classroom participation and learning motivation between the degree of application of virtual interactive technology, teachers' ability to use virtual interactive technology, the degree of support in the classroom environment and the overall performance of college students in English classroom, based on the latest research results and experts' suggestions from domestic and international academics, PLS-SEM was chosen as an analytical tool to assess the indirect effect, direct effect and total effect among the variables (Leguina, 2015; WEN Z, 2014). Under the PLS-SEM framework, the Bootstrap-ping principle was used to analyze the mediating effects, which were further refined into five different types, and the specific classifications are detailed in

Table 5.

The data in Table 4 show that the application of virtual interactive technology further enhanced their interest in English learning by enhancing SCPE, with an indirect effect value of 0.325 (p<0.01), which reached the level of significance, indicating the existence of a mediating effect. Meanwhile, the direct effect value of virtual interactive technology on English learning interest was 0.189 (p<0.01), which also reached the significance level, indicating that classroom engagement played a partially mediating role between virtual interactive technology and students' English learning interest. Given that both the direct and indirect effects are positive, this mediating effect can be judged as an enhanced mediating effect. This result implies that virtual interactive technology not only stimulates students' interest in learning by directly providing rich learning resources and interactive contexts, but also indirectly promotes students' enthusiasm for English learning by increasing SCPE. Similarly, the indirect effect value of virtual interactive technology by increasing classroom engagement and thus affecting students' self-confidence in English learning is 0.312 (p<0.01), and the direct effect value is 0.120 (p<0.01), which confirms the partially mediating role of classroom engagement in the relationship between virtual interactive technology and students' self-confidence in English language learning, and that this mediating effect is also an enhancement one. This means that the application of virtual interactive technology not only directly enhances students' self-confidence, but also further strengthens their self-confidence by increasing the opportunities and quality of classroom interactions so that students can have more successful experiences in actual language practice.

Taken together, the mechanism of the influence of virtual interactive technology on college students' learning interest and self-confidence in English classroom not only includes the direct path, but also covers the indirect path through classroom participation as a mediating variable. On the one hand, the application of virtual interactive technology can directly stimulate students' learning interest and self-confidence and improve the interest and effectiveness of learning by providing an immersive learning experience and allowing students to practice language in a virtual environment. On the other hand, it reinforces the positive impact of virtual interactive technology on students' learning attitudes due to the enhanced mediating role of classroom engagement in this process. Specifically, when virtual interactive technology is effectively used in English language teaching, it not only directly promotes students' motivation, but also improves SCPE by increasing the frequency and quality of classroom interactions, thus indirectly boosting their learning interest and self-confidence. In addition, it was found that the application of virtual interactive technology also has a significant positive impact on students' general English proficiency, an impact that is partly realized through increasing SCPE and learning interest. Through virtual interactive technology, teachers can design more diversified and interactive teaching activities that allow students to practice their language skills in simulated real-life scenarios, and this practice not only improves students' language application skills, but also enhances their motivation and engagement in learning, creating a virtuous cycle that further promotes the overall development of students' English proficiency. In summary, this study not only verifies the direct and indirect effects of virtual interactive technology on college students' interest and self-confidence in English learning, but also reveals the important mediating role of classroom engagement in this process. These findings provide valuable references for educators, emphasize the importance of rationally applying virtual interactive technology in English teaching, and also provide new ideas and methods for improving students' classroom engagement and learning outcomes. Future research can further deepen the understanding of the role of virtual interactive technology in English language teaching by expanding the research perspective and considering more potential mediating variables.

Table 6.

Indirect, direct and total effects.

Table 6.

Indirect, direct and total effects.

| |

Direct effects |

Indirect effects |

Total effects |

Hypothesis testing |

| ADVI->SCPE->UGELP |

0.140** |

0.041** |

0.181** |

H9 support |

| ADVI->SLM->UGELP |

0.179** |

0.067** |

0.246** |

H10 support |

| TVIU->SCPE->UGELP |

0.140** |

0.041** |

0.181** |

H11 support |

| TVIU->SLM->UGELP |

0.279** |

0.104** |

0.383** |

H12 support |

| CES->SCPE->UGELP |

0.578** |

0.171** |

0.749** |

H13 support |

| CES->SLM->UGELP |

0.337** |

0.127** |

0.464** |

H14 support |

5.3. fsQCA Results and Configurations

Referred to

Table 7, The fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) results identified multiple configurations sufficient for achieving high undergraduate English learning performance (UGELP). These findings complement the SEM results by demonstrating that successful outcomes arise not from a single dominant predictor, but through multiple, equifinal causal pathways.Three high-coverage configurations emerged as particularly influential:

Pathway 1: High CES and High SLM → High UGELP

This configuration underscores the synergistic effect of a supportive classroom environment (CES) combined with strong intrinsic student motivation (SLM). Students who perceive their learning environment as supportive and simultaneously exhibit high self-motivation are more likely to achieve optimal English learning outcomes.

Pathway 2: High TVIU and High SCPE → High UGELP

This pathway highlights the importance of teacher proficiency in utilizing virtual instructional tools (TVIU) alongside active student participation (SCPE). Effective integration of technology by instructors fosters student engagement, thereby enhancing English learning performance.

Pathway 3: High ADVI, CES, and SCPE → High UGELP

This more complex configuration emphasizes the necessity of immersive digital environments (ADVI) combined with institutional support (CES) and student behavioral engagement (SCPE). High UGELP is achieved when students are digitally immersed, actively involved, and supported by robust classroom structures.

Each of these configurations demonstrated consistency scores exceeding 0.85 and raw coverage values above 0.70, indicating both robustness and relevance. The results reinforce the principle of causal complexity in educational contexts, suggesting that multiple combinations of technological and psychological factors can lead to successful English language learning. These insights highlight the utility of a configurational approach and the explanatory power of fsQCA in advancing research on educational technologies.

Table 8 summarizes the three configurational pathways identified through fsQCA that lead to high levels of undergraduate English learning performance (UGELP). Each configuration represents a distinct combination of causal conditions that are sufficient to produce the outcome.Configuration 1 demonstrates that a supportive classroom environment (CES) paired with high student learning motivation (SLM) is a key driver of performance, even without the explicit inclusion of teacher technology usage or digital tool exposure. Configuration 2 highlights the importance of teachers’ digital proficiency (TVIU) when paired with strong student engagement (SCPE), suggesting that active learning strategies are highly effective when guided by technologically capable instructors.Configuration 3 represents a comprehensive digital ecosystem: extensive use of virtual interaction technology (ADVI), institutional support (CES), and student engagement (SCPE) together lead to optimal outcomes.

All three solutions exhibit high consistency (≥ 0.85), indicating strong empirical reliability, and coverage above 0.70, showing that each configuration explains a substantial proportion of the high-performing cases. These results reinforce the idea that multiple pathways, rather than a single model, can support effective English language learning in digitally enhanced classrooms.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically explored the effects of virtual interactive technology on college students' English classroom engagement and overall performance through the PLS-SEM method. The findings reveal the significant role of virtual interactive technology in enhancing students' classroom engagement and learning motivation. The application of virtual interactive technology can not only provide rich learning resources and realistic learning situations to stimulate students' interest and initiative in learning, but also enhance students' language application ability by simulating real-life scenarios. In addition, teachers' proficiency in the use of virtual interactive technology also had a significant positive impact on SCPE and learning motivation. Teachers were able to create a more active and interesting classroom atmosphere through virtual interactive technology, which stimulated students' engagement and motivation.

CES is equally important in influencing students' classroom engagement and motivation to learn. A supportive classroom environment, including physical comfort and quietness, ease of use and stability of the virtual learning platform, etc., enables students to be more focused on their studies, increases their motivation to participate in the classroom, and stimulates their learning motivation. The study also found that SCPE and learning motivation played an important mediating role between the degree of application of virtual interactive technology, the teacher's ability to use virtual interactive technology, the degree of classroom environment support, and the overall performance of college students in English classes. Virtual interactive technology indirectly enhanced their interest and self-confidence in English learning by increasing SCPE.TVIU also indirectly enhanced their learning motivation by increasing SCPE.

7. Recommendations

7.2.1. Enhance the Application and Training of Virtual Interactive Technologies

In order to give full play to the potential of virtual interactive technologies in university English teaching, educational institutions should increase their investment in VR and ST technologies and provide more advanced tools and platforms. Schools should purchase high-quality virtual interactive devices and ensure that these devices can run stably to provide students with a smooth learning experience. In addition, schools should establish a specialized technical support team responsible for the maintenance and management of the equipment to ensure that teachers and students can use these technologies without barriers (Lee et al., 2022). At the same time, educational institutions should organize regular training on virtual interactive technologies to help teachers become proficient in the operation methods and application scenarios of these technologies. The training should cover the basic principles of virtual reality technologies, the use of common equipment, and the design and implementation of teaching activities to ensure that teachers can flexibly utilize these technologies in their daily teaching. Teachers should be trained to understand how to use virtual interactive technology to create realistic language learning situations and stimulate students' interest and initiative in learning. At the same time, schools can also invite external experts and technicians to conduct special lectures and workshops to share the latest research results and practical experience, helping teachers to broaden their horizons and improve their teaching standards. Through these measures, TVIU can be effectively improved so as to better serve students' English learning needs .

7.2.2. Building a Supportive Classroom Environment

A supportive classroom environment is an important guarantee for improving students' engagement and motivation in the classroom. To this end, schools should start from several aspects to improve the CES in a comprehensive way. firstly, schools should optimize the physical environment of the classroom to ensure that the classroom is reasonably laid out, well-lit, and at the right temperature to create a comfortable learning space for students. In addition, schools should provide a stable network environment to ensure the smooth operation of virtual interactive technology. Network speed and stability directly affect students' learning experience, so schools should invest in building a high-speed and stable campus network to avoid network problems affecting the teaching effect . Second, schools should provide teachers with training opportunities in virtual interactive technology to help them master new technologies and improve their teaching level. The training should include the basic operation of virtual interactive technology, the design of teaching activities, student assessment methods, etc., to ensure that teachers can skillfully utilize these technologies to create a positive classroom atmosphere. At the same time, schools should encourage teachers to try out new teaching methods and technologies and give them enough freedom and support so that they can continue to explore and innovate in their teaching practice. In addition, schools should provide students with a wealth of virtual interactive learning resources, including virtual laboratories, online interactive platforms, multimedia courseware, etc., to help students receive adequate learning support both inside and outside the classroom. Through these measures, CES can be effectively enhanced and a favorable environment conducive to learning can be created for students.

7.2.3. Strengthening Students' Motivation and Engagement

SLM and classroom engagement are key factors that affect their learning outcomes. In order to stimulate students' learning interest and initiative, teachers should adopt various strategies to enhance SLM and engagement. First, teachers should create rich learning contexts through virtual interactive technology so that students can practice language in simulated real-life scenarios. For example, teachers can use virtual reality technology to design virtual shopping, traveling and other situations, so that students can practice conversations in the virtual environment to improve their language application skills. This practical way of learning can stimulate students' interest and let them learn English in a pleasant atmosphere. Second, teachers should pay attention to the learning needs and characteristics of each student and provide personalized learning programs (Khoo et al., 2024). Virtual simulation technology can provide customized learning resources and exercises according to students' different learning levels and needs, helping students overcome difficulties and bottlenecks in learning. Teachers should communicate with students individually on a regular basis to understand their learning progress and difficulties and provide timely guidance and assistance. Third, teachers should encourage students to actively participate in classroom activities, such as group discussions, role-playing and project cooperation, to promote mutual learning and support among students through interaction and cooperation. Teachers can also stimulate students' motivation and initiative by setting clear learning objectives and reward mechanisms. For example, teachers can set up honorary awards such as weekly star and best group to recognize students who have outstanding performance in learning and enhance their sense of achievement and self-confidence. Through these measures, SLM and classroom engagement can be effectively increased to promote their overall development.

Although this study confirms that classroom engagement plays an important role as an enhancing mediator between virtual interactive technology and students' attitudes toward English learning, it cannot be ignored that there may be other potential mediating variables that have not been taken into account. For example, virtual interactive technology may affect students' perceived quality of the English learning environment, and changes in this perceived quality may, in turn, affect students' attitudes towards learning. In addition, students' personal attributes, such as learning styles and prior knowledge, may also play a mediating role in this process. Therefore, future studies may consider introducing more mediating variables to reveal more comprehensively how virtual interactive technologies affect college students' English learning behaviors and attitudes.

References

- Astin, A. W. (2014). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. In College student development and academic life (pp. 251-262). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior, 11-40. [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of educational research, 74(1), 59-109. [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14-38. [CrossRef]

- Furnari, S., Crilly, D., Misangyi, V., Greckhamer, T., Aguilera, R., & Fiss, P. (2020). Capturing causal complexity: A configurational theorizing process. Academy of Management Review. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Zhang, Y., Fan, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, Z., Li, B., & Chu, H. (2021). MAB_2355c Confers Macrolide Resistance in Mycobacterium abscessus by Ribosome Protection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 65(8). [CrossRef]

- Harmawati, F., Ilma, R., & Amrina, R. D. (2024). Voices Unheard: Teachers' Perspectives on Students' Speaking Challenges in the Classroom. The Art of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TATEFL), 5(2), 175-185. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L. (2013). Competing perspectives on graduate employability: possession, position or process? Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 538-554. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Wang, K., Li, S., & Guo, J. (2022). Using WeChat as an educational tool in MOOC-based flipped classroom: What can we learn from students' learning experience? Front Psychol, 13, 1098585. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Richter, E., Kleickmann, T., & Richter, D. (2022). Comparing video and virtual reality as tools for fostering interest and self-efficacy in classroom management: Results of a pre-registered experiment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(2), 467-488. [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y., & Abu Bakar, J. A. (2024). Comparing cognitive load in learning spatial ability: immersive learning environment vs. digital learning media. Discover Sustainability, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Kamaliasari, & Nurbianta. (2022). From the Classroom to the Living Room: Home-Based Learning to Improve Students’ Achievement in English Learning amid Pandemic. Journal of Pedagogy and Education Science, 1(01), 12-21. [CrossRef]

- Khoo, C., Sharma, S., Jefree, R. A., Chee, D., Koh, Z. N., Lee, E. X. Y., Loh, N.-H. W., Ashokka, B., Paranjothy, S. J. J. o. C., & Anesthesia, V. (2024). Self-directed virtual reality-based training versus traditional physician-led teaching for point-of-care cardiac ultrasound: A randomized controlled study.

- Kozorez, D. A., Shefieva, E., Simonova, O., Bessarabova, O., Kalugin, V. T., Yong, S., & Severina, N. (2022). Virtual simulators application in the foreign language studying as the factor of students motivating. SHS Web of Conferences, 137. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Woo, D., & Yu, S. J. A. S. (2022). Virtual reality metaverse system supplementing remote education methods: Based on aircraft maintenance simulation. 12(5), 2667.

- Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). In: Taylor & Francis.

- Lin, X. P., Li, B. B., Yao, Z. N., Yang, Z., & Zhang, M. (2024). The impact of virtual reality on student engagement in the classroom–a critical review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1360574. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Li, W., Zuo, M., Wang, F., Guo, Z., & Schwieter, J. W. (2022). Cross-task adaptation effects of bilingual language control on cognitive control: a dual-brain EEG examination of simultaneous production and comprehension. Cerebral Cortex, 32(15), 3224-3242. [CrossRef]

- Molotsı, A. (2020). The university staff experience of using a virtual learning environment as a platform for e-learning. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 3(2), 133-151. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A. M. V., & Ribeiro, P. N. d. S. (2020). Virtual Reality in English Vocabulary Teaching: An Exploratory Study on Affect in the Use of Technology. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 59(2), 1310-1338. [CrossRef]

- Nshimiyimana, E., & Ndayambaje, I. (2025). Enhancing Students' Understanding of Earth's Spatial Relationships Using Virtual Reality: A Case Study of Secondary Schools in Nyamasheke District, Rwanda. African Journal of Empirical Research, 6(1), 773-791. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X. (2023). Online Learning Environments, Learners’ Empowerment, and Learning Behavioral Engagement: The Mediating Role of Learning Motivation. Sage Open, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I. O., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. International Journal of Information Management, 58. [CrossRef]

- Portuguez-Castro, M., & Santos Garduño, H. J. E. S. (2024). Beyond Traditional Classrooms: Comparing Virtual Reality Applications and Their Influence on Students’ Motivation. 14(9), 963.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Schott, C., & Marshall, S. (2018). Virtual reality and situated experiential education: A conceptualization and exploratory trial. Journal of computer assisted learning, 34(6), 843-852. [CrossRef]

- WEN Z, Y. B. (2014). Mediation effect analysis: method and model development. 22(05), 731-745. https://next.cnki.net/middle/abstract?v=ufuULlVWCsO8iV9nI0AEaNF7RUAkZciCPpadcxHevSIYOLLlOXj6S4q2HBxfagGg8u5OH9vSJlFtalVDRhOePHfTWeyXh58x_K2iJnL3t8CaINTs3sI11vHltu0upQR6Fv2P56bG2Nakpf7-RYGtOWzDK1V_vPwc6EGW8uSPvKWljZgevU9nN0a6M0NgeyAd&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&scence=null.

- Yan, W., Lowell, V. L., & Yang, L. (2024). Developing English language learners’ speaking skills through applying a situated learning approach in VR-enhanced learning experiences. Virtual Reality, 28(4). [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C., Wang, H., Xu, H., Yao, W., Jiang, J., & Zhou, L. (2023). On the Application of Virtual Reality Technology in Smart Education. Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Video, Signal and Image Processing.

- Zhai, Q. (2023). Improvement of English Writing Skills through Online Interactive Platforms and Virtual Reality Technology. Academic Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 6(14), 74-80. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).