Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

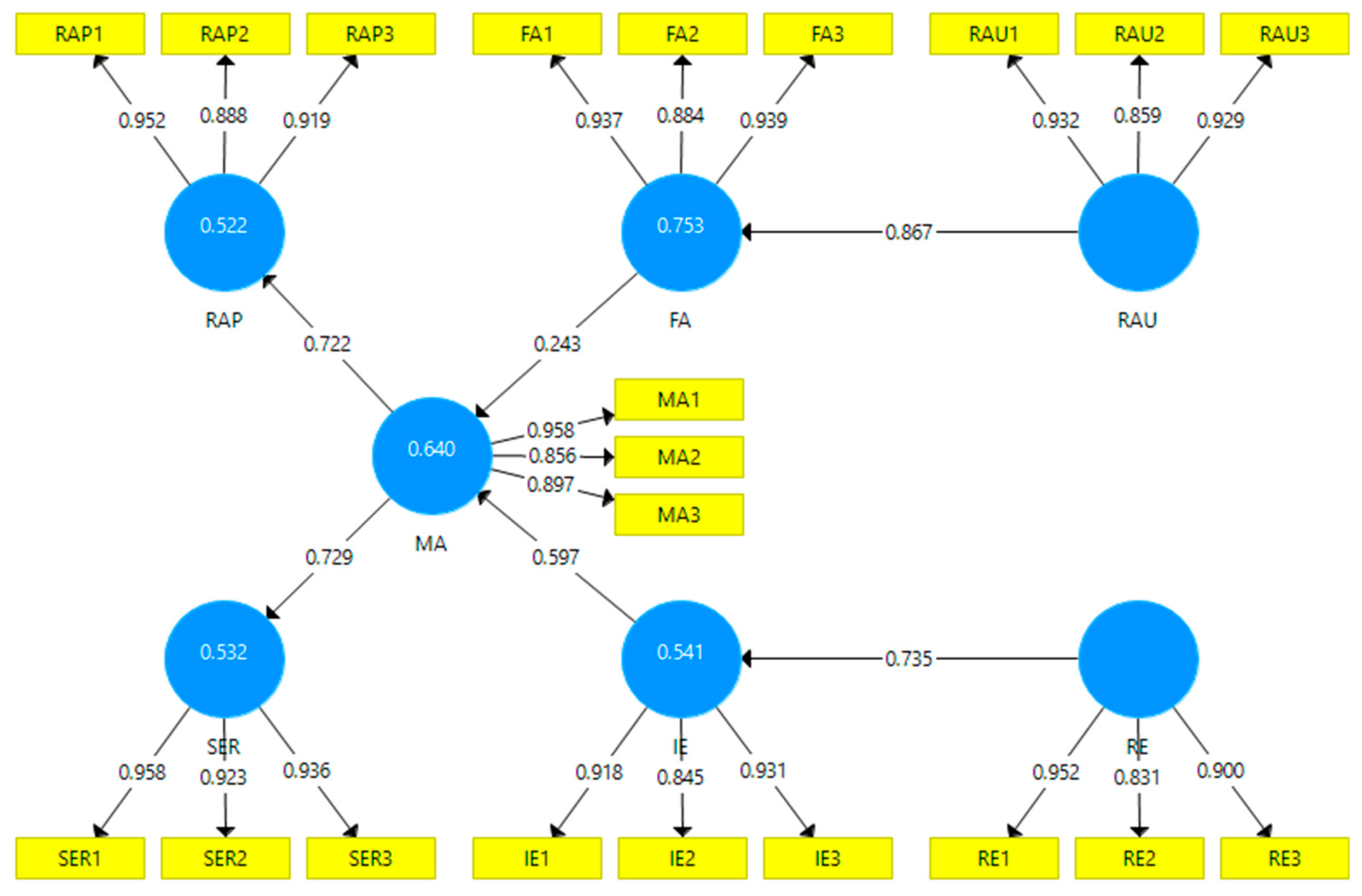

Augmented reality (AR) is revolutionising education by integrating virtual elements into physical environments, enhancing interactivity and participation in learning processes. This study analyses the impact of AR in higher education, examining its influence on ease of adoption, student interaction, academic motivation and educational sustainability. A quantitative and explanatory design was employed, applying structural equation modelling (SmartPLS) to a sample of 4,900 students from public and private universities. The results indicate that AR significantly improves the ease of adoption (β = 0.867), favouring its implementation. In addition, student interaction increases academic motivation (β = 0.597), impacting on perceived academic performance (β = 0.722) and educational sustainability (β = 0.729). These findings highlight the need to design effective learning experiences with AR to maximise their impact. However, challenges such as technological infrastructure, teacher training and equitable access must be addressed to ensure sustainable adoption. This study provides empirical evidence on the potential of AR to enhance motivation, learning and educational transformation. Future research should explore its effectiveness in diverse contexts to optimise pedagogical strategies and institutional policies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

| Type of variable | Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Question (Likert scale 1-7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous | Use of Augmented Reality (RAU) | RAU1 | I frequently use augmented reality tools during my classes. |

| RAU2 | I believe that augmented reality facilitates the learning of complex concepts. | ||

| RAU3 | Augmented reality tools are intuitive and easy to use. | ||

| Exogenous | Educational Relevance (RE) | RE1 | The content presented using augmented reality is aligned with the course objectives. |

| RE2 | Augmented reality has practical applications in my field of study. | ||

| RE3 | I believe that augmented reality improves the quality of the classes. | ||

| Endogenous Mediator | Ease of Adoption (FA) | FA1 | I find it easy to learn how to use augmented reality tools. |

| FA2 | Implementing augmented reality in the classroom does not require much time. | ||

| FA3 | I have the necessary resources to use augmented reality in my learning. | ||

| Endogenous Mediator | Student Interaction (IE) | IE1 | Augmented reality encourages collaboration between my classmates and me. |

| IE2 | Interaction with my classmates improves thanks to the use of augmented reality. | ||

| IE3 | Activities based on augmented reality promote greater participation in class. | ||

| Endogenous Mediator | Academic Motivation (MA) | MA1 | The use of augmented reality increases my interest in the subjects I study. |

| MA2 | I feel more motivated to learn when augmented reality is used in class. | ||

| MA3 | I prefer interactive learning methods, such as augmented reality, over traditional ones. | ||

| Endogenous Dependent | Perceived Academic Performance (RAP) | RAP1 | My understanding of concepts improves when I use augmented reality in my studies. |

| RAP2 | My academic performance benefits from using augmented reality tools. | ||

| RAP3 | I solve problems more easily when using augmented reality resources. | ||

| Endogenous Dependent | Educational Sustainability (SER) | SER1 | I believe that augmented reality should be implemented permanently in learning. |

| SER2 | The educational benefits of augmented reality justify its continued use in institutions. | ||

| SER3 | The implementation of augmented reality is viable in the long term in the educational context. |

2.3. Hypothesis Statement

- H1: The use of augmented reality (RAU) has a positive influence on the ease of adoption (FA) in teaching-learning processes.

- H2: Educational relevance (ER) has a positive effect on student interaction (SI) in educational environments that integrate augmented reality.

- H3: Student interaction (SI) has a positive impact on academic motivation (MA) in the context of the use of emerging technologies such as augmented reality.

- H4: Ease of adoption (FA) has a positive influence on academic motivation (MA) in the use of augmented reality in educational processes.

- H5: Academic motivation (AM) has a positive effect on perceived academic performance (PAR) and educational sustainability (ES) in educational institutions.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

2.5. Consideraciones Éticas

2.6. Data Availability Statement

3. Results

3.1. Reliability and Validity of the Construct

3.2. Explanatory Power of the Model

3.3. Discriminant Validity

3.4. Path Coefficients and Significance

3.5. Confidence Intervals

3.6. Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. H. Hadi et al., “Developing augmented reality-based learning media and users’ intention to use it for teaching accounting ethics,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 643–670, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Fombona-Pascual, J. Fombona, and R. Vicente, “Augmented Reality, a Review of a Way to Represent and Manipulate 3D Chemical Structures,” J Chem Inf Model, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 1863–1872, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Marín, B. E. Sampedro, J. M. Muñoz González, and E. M. Vega, “Primary Education and Augmented Reality. Other Form to Learn,” Cogent Education, vol. 9, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Shen, K. Xu, M. Sotiriadis, and Y. Wang, “Exploring the factors influencing the adoption and usage of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality applications in tourism education within the context of COVID-19 pandemic,” J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ, vol. 30, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y.-Y. Chou et al., “Effect of Digital Learning Using Augmented Reality with Multidimensional Concept Map in Elementary Science Course,” Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 383–393, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Karacan and M. Polat, “Predicting pre-service English language teachers’ intentions to use augmented reality,” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 139–153, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Markouzis, A. Baziakou, G. Fesakis, and A. Dimitracopoulou, “A Systematic Review on Augmented Reality Applications in Informal Learning Environments,” International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, vol. 14, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Christopoulos, N. Pellas, J. Kurczaba, and R. Macredie, “The effects of augmented reality-supported instruction in tertiary-level medical education,” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 307–325, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. González-Pérez and J. J. Marrero-Galván, “DEVELOPMENT OF A FORMATIVE SEQUENCE FOR PROSPECTIVE SCIENCE TEACHERS: THE CHALLENGE OF IMPROVING TEACHING WITH ANALOGIES THROUGH THE INTEGRATION OF INFOGRAPHICS AND AUGMENTED REALITY,” J Technol Sci Educ, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 159–177, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Hobbs and D. Holley, “A Radical Approach to Curriculum design: engaging Students Through Augmented Reality,” International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, vol. 14, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Lim, “Expanding Multimodal Artistic Expression and Appreciation Methods through Integrating Augmented Reality,” International Journal of Art and Design Education, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 562–576, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Erçağ and A. Yasakcı, “The Perception Scale for the 7E Model-Based Augmented Reality Enriched Computer Course (7EMAGBAÖ): Validity and Reliability Study,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Andrews, “Mind Power: Thought-controlled Augmented Reality for Basic Science Education,” Med Sci Educ, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1571–1573, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Drljević, I. Botički, and L.-H. Wong, “Investigating the different facets of student engagement during augmented reality use in primary school,” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 1361–1388, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Dutta, A. Mantri, and G. Singh, “Evaluating system usability of mobile augmented reality application for teaching Karnaugh-Maps,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 9, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Lampropoulos, E. Keramopoulos, K. Diamantaras, and G. Evangelidis, “Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Education: Public Perspectives, Sentiments, Attitudes, and Discourses,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 12, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Díaz, C. J. Álvarez-Gallego, I. Caro, and J. R. Portela, “Incorporating Augmented Reality Tools into an Educational Pilot Plant of Chemical Engineering,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 13, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Belda-Medina and J. R. Calvo-Ferrer, “Integrating augmented reality in language learning: pre-service teachers’ digital competence and attitudes through the TPACK framework,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 12123–12146, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Papakostas, C. Troussas, A. Krouska, and C. Sgouropoulou, “Exploring Users’ Behavioral Intention to Adopt Mobile Augmented Reality in Education through an Extended Technology Acceptance Model,” Int J Hum Comput Interact, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1294–1302, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Radu, J. Yuan, X. Huang, and B. Schneider, “Charting opportunities and guidelines for augmented reality in makerspaces through prototyping and co-design research,” Computers and Education: X Reality, vol. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Samala et al., “Global Publication Trends in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality for Learning: The Last Twenty-One Years,” International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 109–128, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Najmi, W. S. Alhalafawy, and M. Z. T. Zaki, “Developing a Sustainable Environment Based on Augmented Reality to Educate Adolescents about the Dangers of Electronic Gaming Addiction,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Fearn and J. Hook, “A SERVICE DESIGN THINKING APPROACH: WHAT ARE THE BARRIERS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF USING AUGMENTED REALITY FOR PRIMARY SCIENCE EDUCATION?,” J Technol Sci Educ, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 329–351, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Rueda Márquez de la Plata, P. A. Cruz Franco, and J. A. Ramos Sánchez, “Applications of Virtual and Augmented Reality Technology to Teaching and Research in Construction and Its Graphic Expression,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Taggart et al., “Virtual and augmented reality and pre-service teachers: Makers from muggles?,” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 1–16, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mena, O. Estrada-Molina, and E. Pérez-Calvo, “Teachers’ Professional Training through Augmented Reality: A Literature Review,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 13, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang and L. Tan, “The Conceptualisation of User-App Interactivity in Augmented Reality-Mediated Learning: Implications for Literacy Education,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Lampropoulos, E. Keramopoulos, K. Diamantaras, and G. Evangelidis, “Integrating Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Serious Games in Computer Science Education,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 13, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, “Interactive piano training using augmented reality and the Internet of Things,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 6373–6389, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ö. Anil and V. Batdi, “Use of augmented reality in science education: A mixed-methods research with the multi-complementary approach,” Educ Inf Technol (Dordr), vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 5147–5185, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Badriyah, M. Yusuf, and A. Efendi, “Augmented Reality as a Media for Distance Learning in the Digital Era: Contribution in Improving Critical Thinking Skills,” International Journal of Information and Education Technology, vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 1769–1775, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, F. Mahamid, and A. Mousa, “Augmented Reality-Based Learning: The Efficacy on Learner‘s Motivation and Reflective Thinking,” International Journal of Information and Education Technology, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 1051–1061, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yüzüak and H. Yiğit, “Augmented reality application in engineering education: N-Type MOSFET,” International Journal of Electrical Engineering and Education, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 245–257, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhao, Y. Ren, and K. S. L. Cheah, “Leading Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) in Education: Bibliometric and Content Analysis From the Web of Science (2018–2022),” Sage Open, vol. 13, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Hicks, C. H. Rinaudo, and R. Burch, “The Use of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Ergonomic Applications for Education, Aviation, and Maintenance,” Ergonomics in Design, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 23–31, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Widyaningsih et al., “Physical Education Learning Design with Augmented Reality for Special Needs Students,” International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 1070–1078, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, E. Yujin Kang, S. Yan, E. Louime, C. Hancock, and A. Hira, “Augmented Reality in A Sustainable Engineering Design Context: Understanding Students’ Collaboration and Negotiation Practices,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gokbulut and M. Durnali, “Professional skills training in developing digital materials through augmented and virtual reality applications,” Psychol Sch, vol. 60, no. 11, pp. 4267–4292, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Drljević, I. Botički, and L. H. Wong, “Observing student engagement during augmented reality learning in early primary school,” Journal of Computers in Education, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 181–213, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C.-C. Chen, X. Kang, X.-Z. Li, and J. Kang, “Design and Evaluation for Improving Lantern Culture Learning Experience with Augmented Reality,” Int J Hum Comput Interact, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1465–1478, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, W. Mao, Y. Hu, J. Wang, X. Wan, and H. Fang, “Does augmented reality help in industrial training? A comprehensive evaluation based on natural human behavior and knowledge retention,” Int J Ind Ergon, vol. 98, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Prasittichok, S. Jitprapaikulsarn, K. Sriprasertpap, and G.-J. Hwang, “Technological solutions to fostering students’ moral courage: an augmented reality-based contextual gaming approach,” Cogent Education, vol. 11, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. I. Ladykova, E. I. Sokolova, L. Y. Grebenshchikova, R. G. Sakhieva, N. I. Lapidus, and Y. V. Chereshneva, “Augmented reality in environmental education: A systematic review,” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, vol. 20, no. 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gießer, J. Schmitt, E. Lowenstein, C. Weber, V. Braun, and R. Bruck, “SkillsLab+ - A New Way to Teach Practical Medical Skills in an Augmented Reality Application With Haptic Feedback,” IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, vol. 17, pp. 2034–2047, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Gill et al., “Implementing Universal Design through augmented-reality game-based learning,” Computers and Education: X Reality, vol. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Lin and C. S. Ironsi, “Incorporating augmented reality into teaching marketing strategies: Perspectives from business education teachers and students,” International Journal of Management Education, vol. 22, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Rizki et al., “Cooperative model, digital game, and augmented reality-based learning to enhance students’ critical thinking skills and learning motivation,” Journal of Pedagogical Research, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 339–355, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Arztmann, J. L. Domínguez Alfaro, L. Hornstra, J. Jeuring, and L. Kester, “In-game performance: The role of students’ socio-economic status, self-efficacy and situational interest in an augmented reality game,” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 484–498, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tuta and L. Luić, “D-Learning: An Experimental Approach to Determining Student Learning Outcomes Using Augmented Reality (AR) Technology,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 14, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Harnal et al., “Bibliometric mapping of theme and trends of augmented reality in the field of education,” J Comput Assist Learn, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 824–847, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Mkwizu and R. Bordoloi, “Augmented reality for inclusive growth in education: the challenges,” Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 88–100, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Akinradewo, M. Hafez, C. Aigbavboa, A. Ebekozien, P. Adekunle, and O. Otasowie, “Innovating Built Environment Education to Achieve SDG 4: Key Drivers for Integrating Augmented Reality Technologies,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Nelson et al., “The effectiveness of learning media based on digital augmented reality (AR) technology on the learning outcomes of martial arts | La eficacia de los medios de aprendizaje basados en tecnología de realidad aumentada digital (AR) en los resultados del apren,” Retos, vol. 63, pp. 878–885, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Nikou, M. Perifanou, and A. A. Economides, “Exploring Teachers’ Competences to Integrate Augmented Reality in Education: Results from an International Study,” TechTrends, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 1208–1221, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Nikou, M. Perifanou, and A. A. Economides, “Development and validation of the teachers’ augmented reality competences (TARC) scale,” Journal of Computers in Education, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1041–1060, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Di Fuccio, J. Kic-Drgas, and J. Woźniak, “Co-created augmented reality app and its impact on the effectiveness of learning a foreign language and on cultural knowledge,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 11, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Del Moral-Pérez, N. López-Bouzas, and J. Castañeda-Fernández, “Transmedia skill derived from the process of converting films into educational games with augmented reality and artificial intelligence,” Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, vol. 13, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Stalheim and H. M. Somby, “An embodied perspective on an augmented reality game in school: pupil’s bodily experience toward learning,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 11, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yuniarti et al., “Augmented reality-based higher order thinking skills learning media: Enhancing learning performance through self-regulated learning, digital literacy, and critical thinking skills in vocational teacher education,” Eur J Educ, vol. 59, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Gill et al., “Enhancing learning in design for manufacturing and assembly: the effects of augmented reality and game-based learning on student’s intrinsic motivation,” Interactive Technology and Smart Education, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 61–80, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. V. Kulkarni and R. Harne, “ADOPTION AND USAGE OF AUGMENTED REALITY-BASED VIRTUAL LABORATORIES TOOL FOR ENGINEERING STUDIES,” Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, vol. 23, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Chen, P.-H. Lin, Y.-H. Lai, and C.-J. Liu, “Enhancing Education on Aurora Astronomy and Climate Science Awareness through Augmented Reality Technology and Mobile Learning,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lu, “The Impact of Augmented Reality on Motor Skills in Piano Education: Improving the Left-Hand Technique with AR Piano,” Int J Hum Comput Interact, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, X. Wang, B. Le, and L. Wang, “Why people use augmented reality in heritage museums: a socio-technical perspective,” Herit Sci, vol. 12, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Karelkhan and N. Uderbayeva, “The Effectiveness of Using Virtual and Augmented Reality Technologies for Teaching Computer Science in Schools,” International Journal of Information and Education Technology, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 1566–1573, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim et al., “Creating augmented reality-based experiences for aviation weather training: Challenges, opportunities, and design implications for 3D authoring,” Ergonomics, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 374–390, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Muttaqiin, R. Oktavia, Z. F. Luthfi, and Yulkifli, “Developing an Augmented Reality-Assisted Worksheet to Support the Digital Science Practicum,” European Journal of Educational Research, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 605–617, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Yanuarto, E. Suanto, I. Hapsari, and A. N. Khusnia, “How to Motivate Students Using Augmented Reality in The Mathematics Classroom? An Experimental Study,” Mathematics Teaching-Research Journal, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 191–212, 2024.

- Omarov, B. Omarov, Z. Azhibekova, and B. Omarov, “Applying an augmented reality game-based learning environment in physical education classes to enhance sports motivation | Aplicación de un entorno de aprendizaje basado en juegos de realidad aumentada en clases de educación física para potenciar la motiv,” Retos, vol. 60, pp. 269–278, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Fu et al., “Application of Handheld Augmented Reality in Nursing Education: A Scoping Review,” Nurse Educ, 2025. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 0.910 | 0.914 | 0.943 | 0.847 |

| IE | 0.880 | 0.883 | 0.926 | 0.808 |

| MA | 0.888 | 0.890 | 0.931 | 0.818 |

| RAP | 0.909 | 0.910 | 0.943 | 0.847 |

| RAU | 0.892 | 0.894 | 0.933 | 0.823 |

| RE | 0.876 | 0.892 | 0.924 | 0.803 |

| SER | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.957 | 0.882 |

| Variable | R Squared | R Squared-Fitted | f² (effect size) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 0.753 | 0.750 | 3.041 |

| IE | 0.541 | 0.536 | 1.176 |

| MA | 0.640 | 0.632 | 0.394 |

| RAP | 0.522 | 0.517 | 1.091 |

| SER | 0.532 | 0.527 | 1.137 |

| Variable | FA | IE | MA | RAP | RAU | RE | SER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 0.920 | ||||||

| IE | 0.775 | 0.899 | |||||

| MA | 0.706 | 0.785 | 0.905 | ||||

| RAP | 0.839 | 0.747 | 0.722 | 0.920 | |||

| RAU | 0.867 | 0.736 | 0.713 | 0.913 | 0.907 | ||

| RE | 0.832 | 0.735 | 0.737 | 0.908 | 0.891 | 0.896 | |

| SER | 0.848 | 0.748 | 0.729 | 0.899 | 0.897 | 0.962 | 0.939 |

| Relationship | Original sample | Sample average | Standard deviation | t-statistic | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA -> MA | 0.243 | 0.247 | 0.089 | 2.734 | 0.003 |

| IE -> MA | 0.597 | 0.594 | 0.084 | 7.086 | 0.001 |

| MA -> RAP | 0.722 | 0.721 | 0.044 | 16.351 | 0.001 |

| MA -> SER | 0.729 | 0.728 | 0.045 | 16.288 | 0.001 |

| RAU -> FA | 0.867 | 0.868 | 0.028 | 31.327 | 0.001 |

| RE -> IE | 0.735 | 0.735 | 0.042 | 17.405 | 0.001 |

| Relationship | Original Sample (O) | Sample Average (M) | 5.00% | 95.00% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA -> MA | 0.243 | 0.247 | 0.105 | 0.395 |

| IE -> MA | 0.597 | 0.594 | 0.454 | 0.722 |

| MA -> RAP | 0.722 | 0.721 | 0.641 | 0.790 |

| MA -> SER | 0.729 | 0.728 | 0.645 | 0.794 |

| RAU -> FA | 0.867 | 0.868 | 0.821 | 0.913 |

| RE -> IE | 0.735 | 0.735 | 0.663 | 0.803 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).