Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

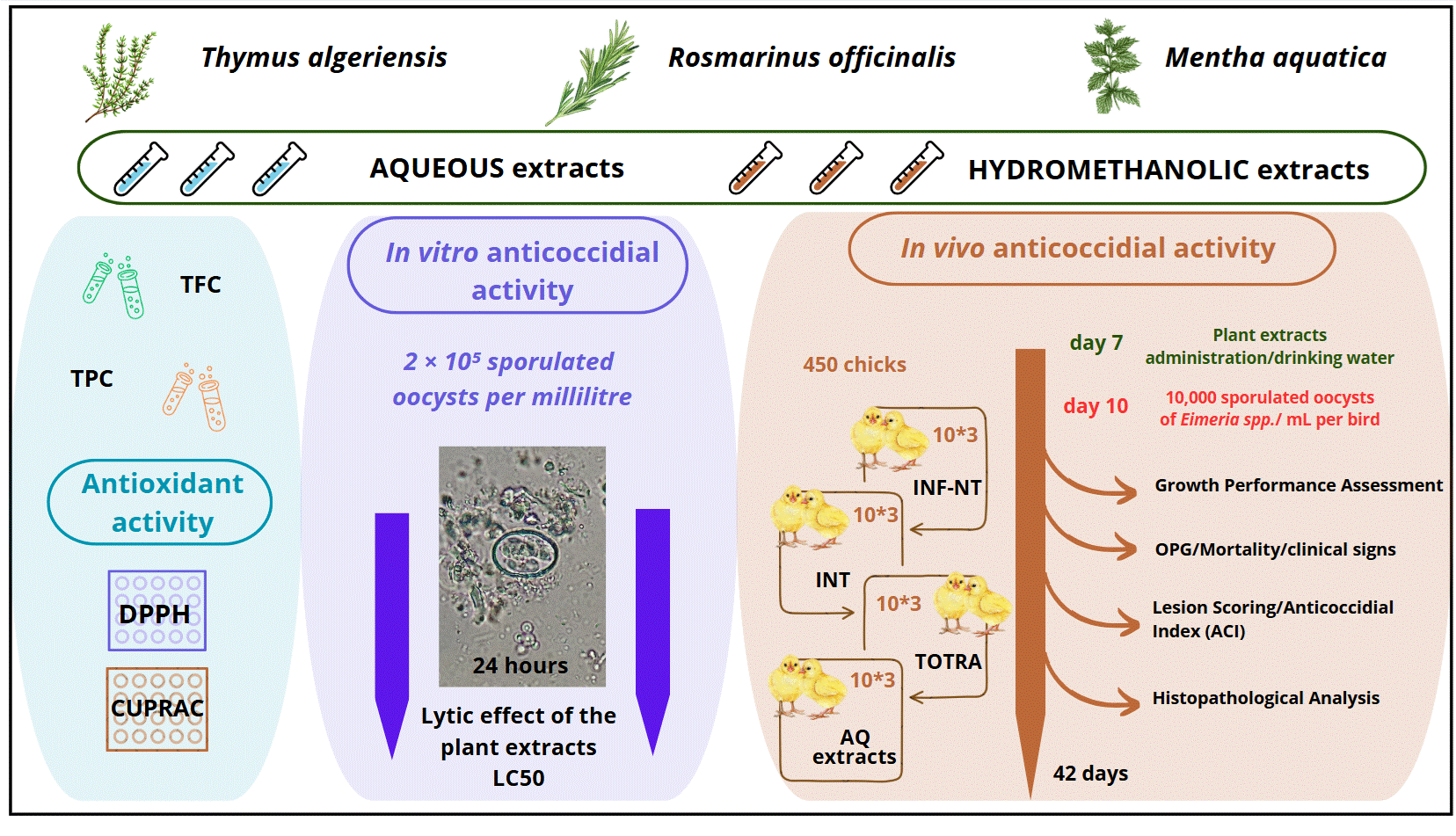

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Preparation

2.2. Total Polyphenol Content

2.3. Total Flavonoid Content

2.4. Antioxidant Activity

2.4.1. DPPH Assay

2.4.2. CUPRAC Assay

2.5. Anticoccidial Activity

2.5.1. Parasite Source

2.5.2. In Vitro Anticoccidial Activity

2.5.3. In Vivo Evaluation of Plant-Extract Efficacy Against Coccidiosis

- Farm characteristics and animal husbandry

- Safety dose assessment

- Experimental design

- Studied parameters

- 1.

- Growth Performance Assessment

- 2.

- Survival and Weight-Gain Indices

- 3.

- Oocyst Enumeration

- 4.

- Lesion Scoring

- 5.

- Anticoccidial Index (ACI)

- 6.

- Histopathological Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

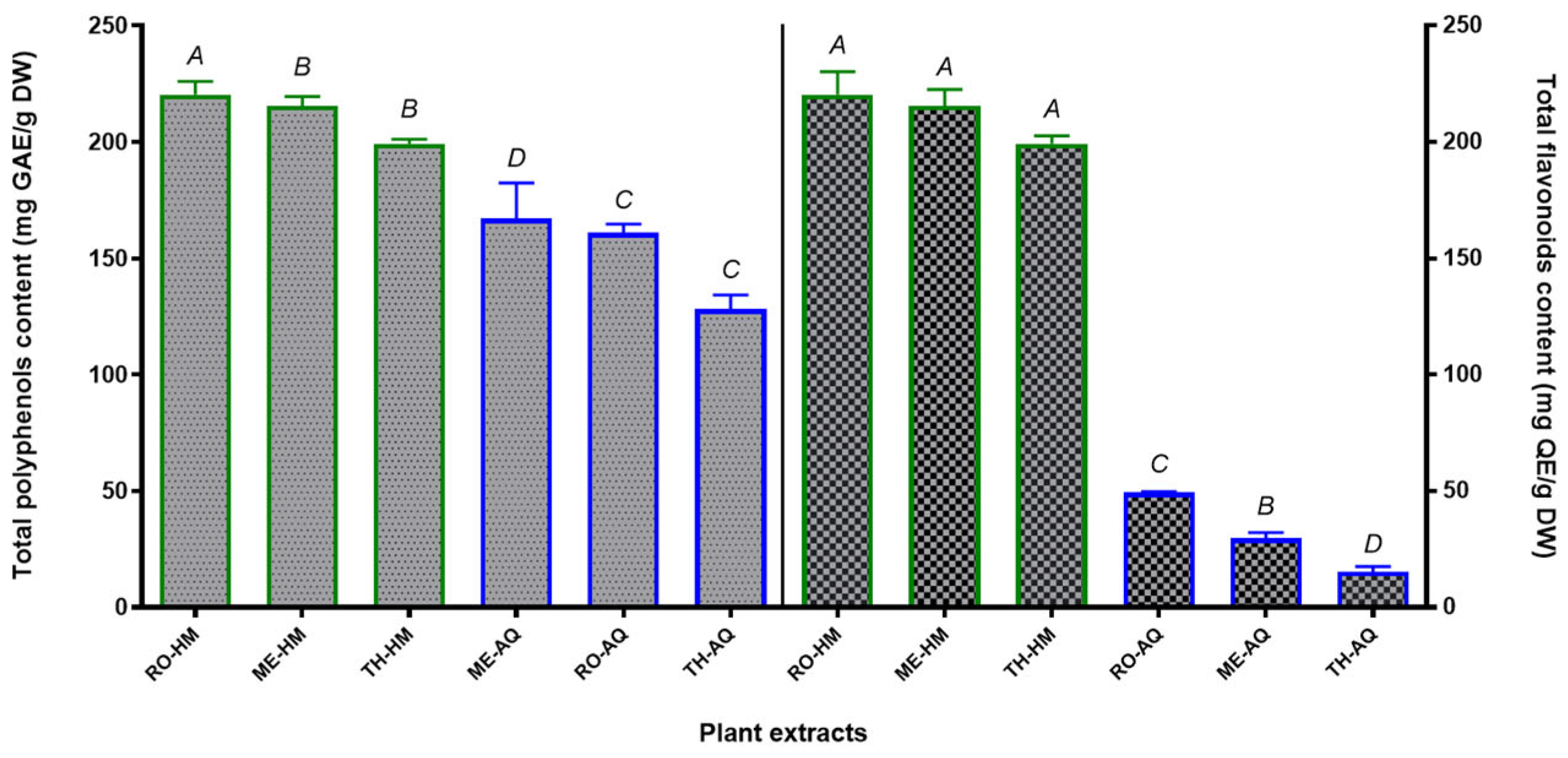

3.1. Polyphenols and Flavonoid Contents

3.2. Antioxidant Activity

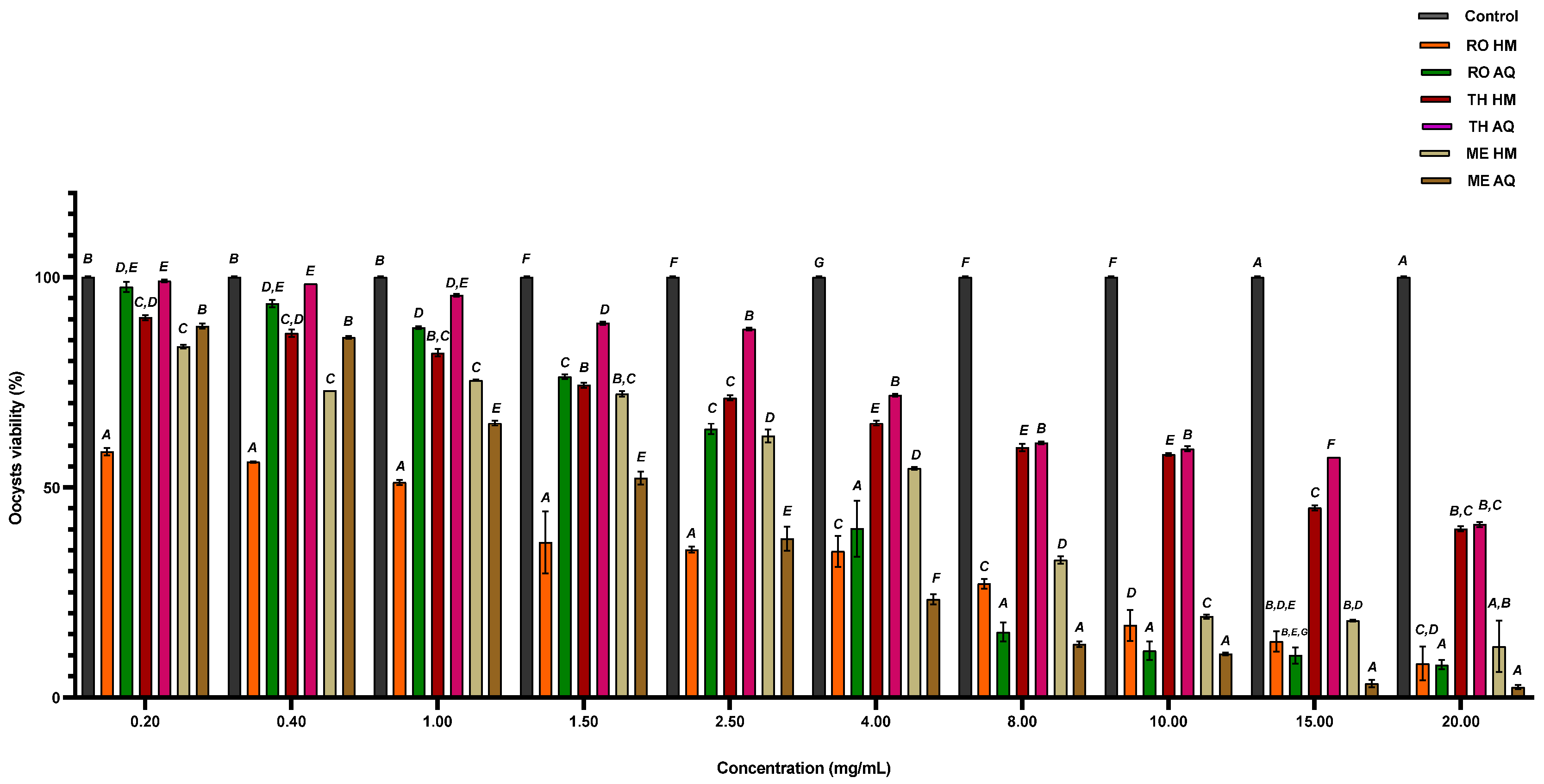

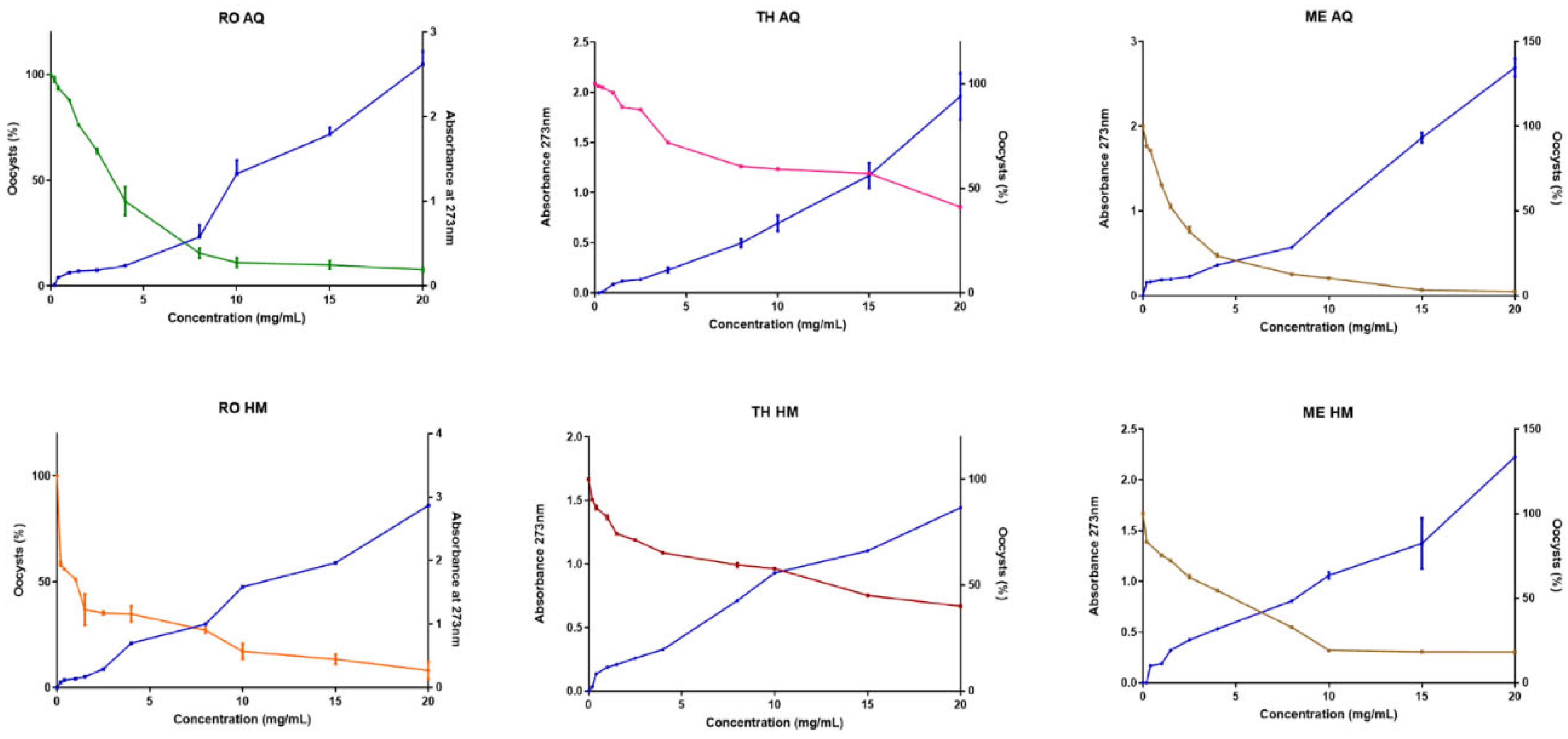

3.3. In Vitro Anticoccidial Activity

3.4. In Vivo Experimentation

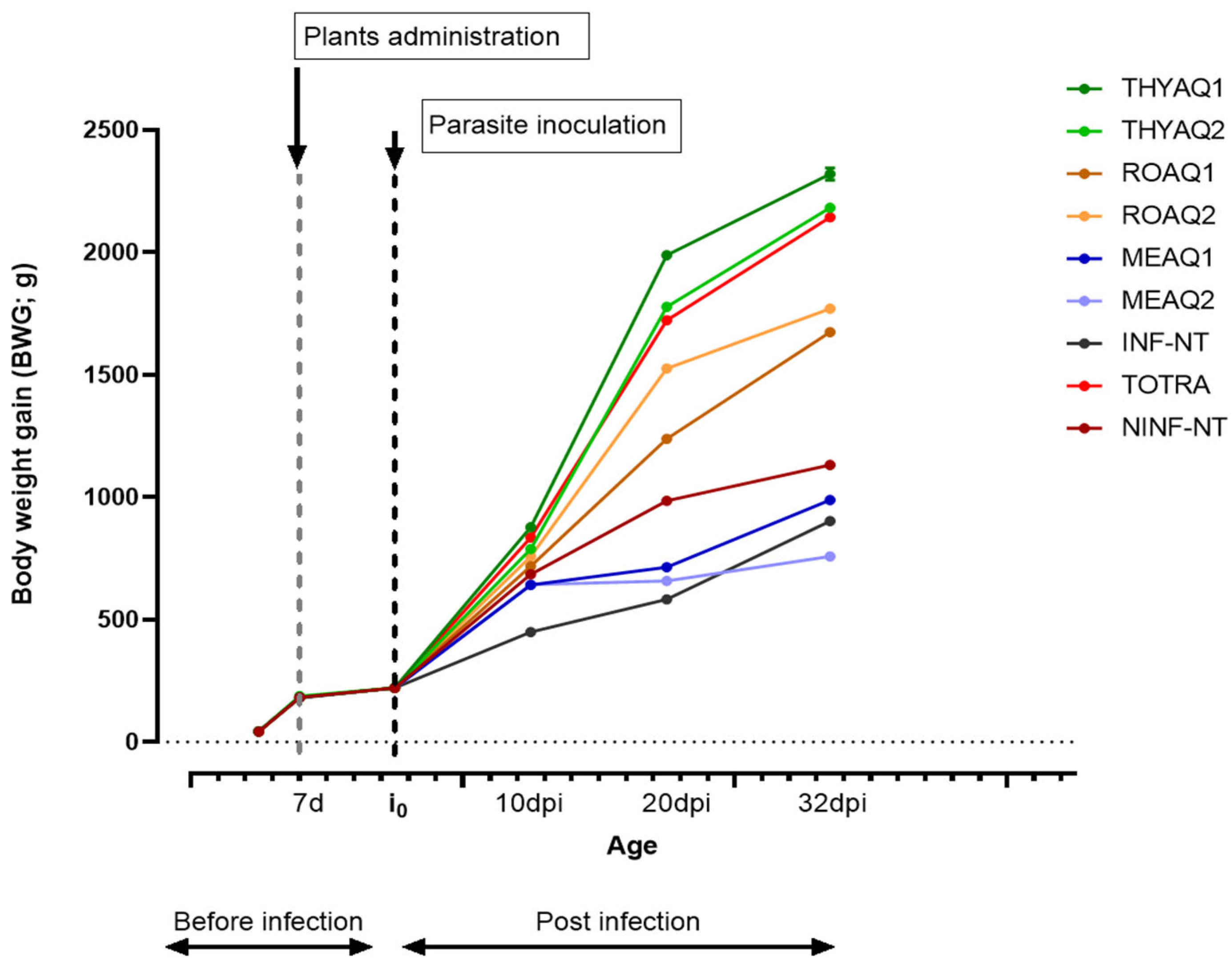

3.4.1. Growth Performance and Feed Efficiency

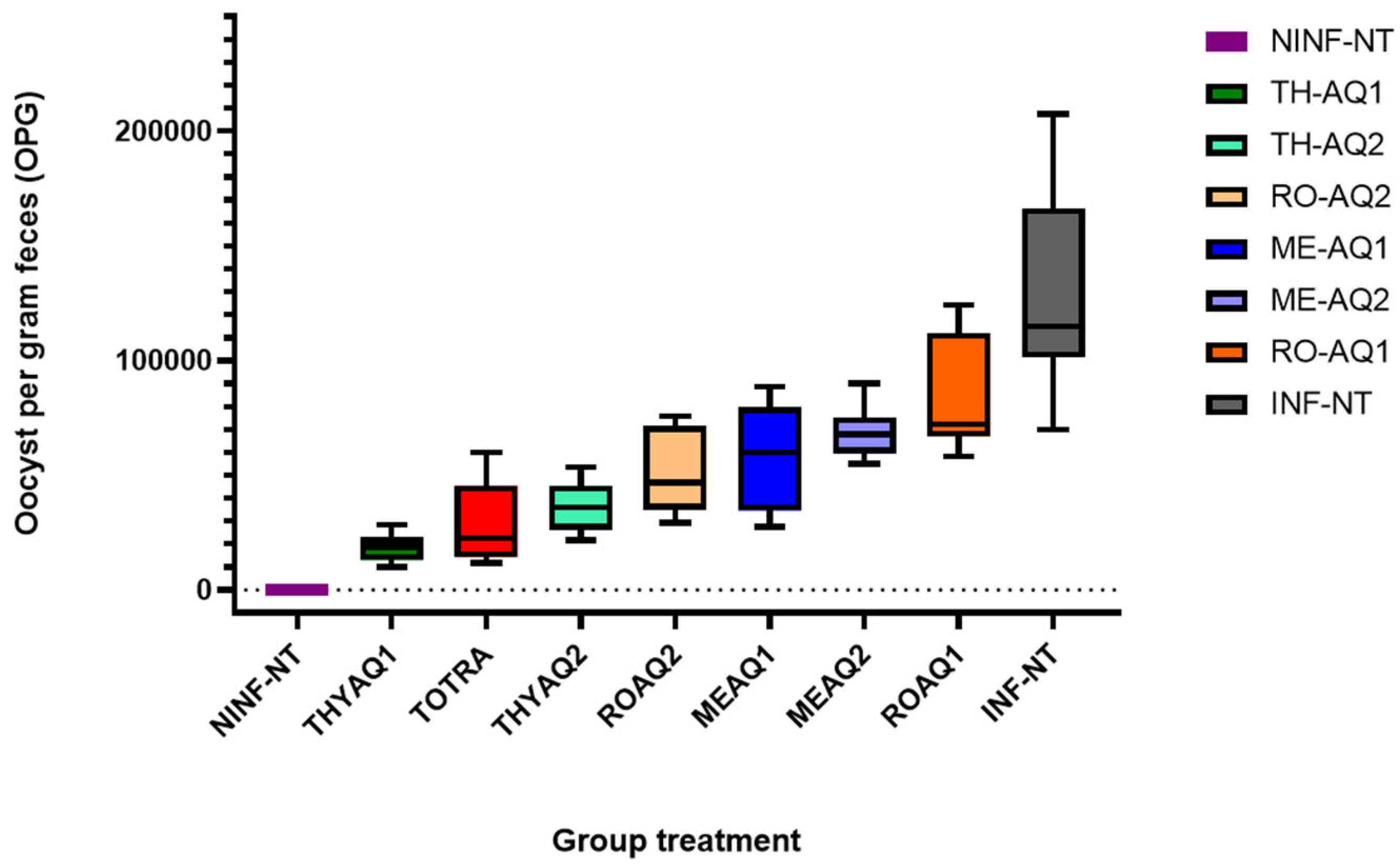

3.4.2. Clinical Protection, Lesion Scores and Anticoccidial Index

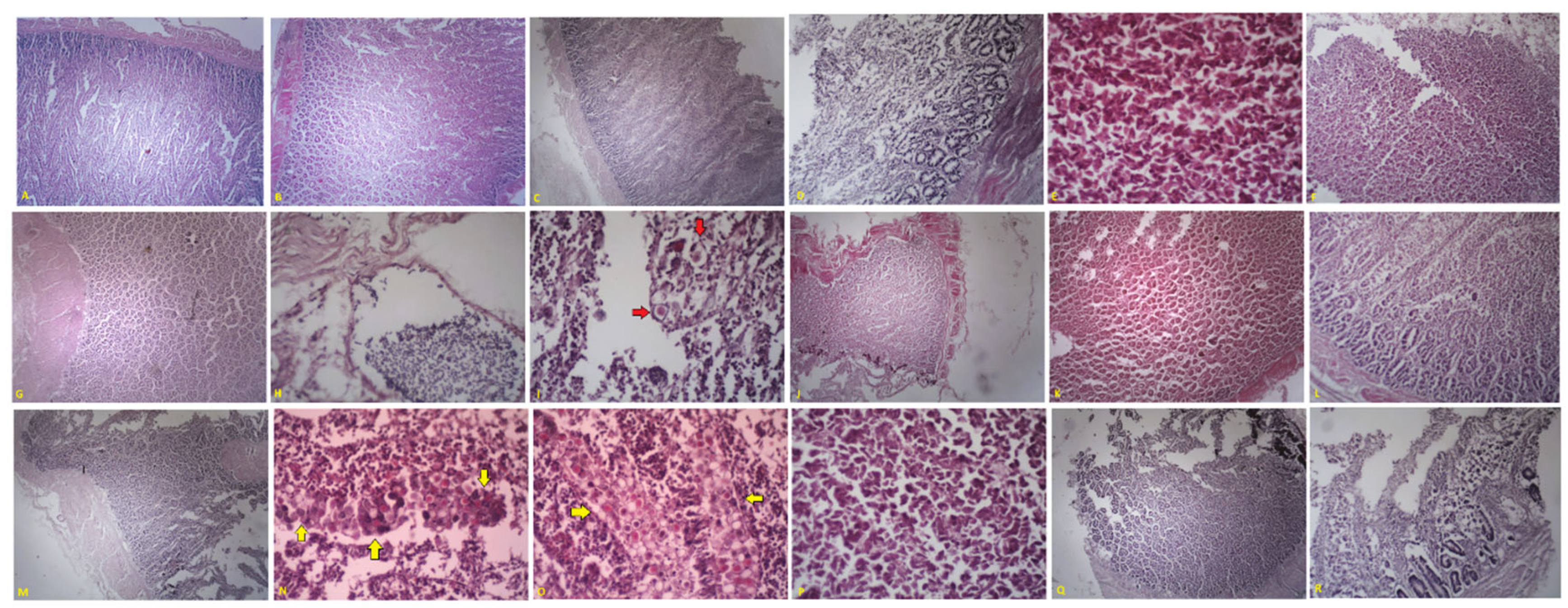

3.4.3. Intestinal Histopathology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, C.D.; Lister, S.A.; Gittins, J. Impact Assessment of the Reduction or Removal of Ionophores Used for Controlling Coccidiosis in the UK Broiler Industry. Veterinary Record 2011, 189, no. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.P.; Tomley, F.M. Securing Poultry Production from the Ever-Present Eimeria Challenge. Trends Parasitol 2014, 30, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa-Pineda, C.; Navarro-Ruíz, J.L.; López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Chicken Coccidiosis: From the Parasite Lifecycle to Control of the Disease. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 787653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attree, E.; Sanchez-Arsuaga, G.; Jones, M.; Xia, D.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Blake, D.; Tomley, F. Controlling the Causative Agents of Coccidiosis in Domestic Chickens; an Eye on the Past and Considerations for the Future. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience 2021, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, H.D. Coccidiosis in Egg Laying Poultry. Egg Innovations and Strategies for Improvements 2017, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha, M.J.; Srikanth, M.K. Occurrence of Caecal Coccidiosis in Poultry. Indian Veterinary Journal 2022, 99, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa-Pineda, C.; Navarro-Ruíz, J.L.; López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Chicken Coccidiosis: From the Parasite Lifecycle to Control of the Disease. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 787653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.P.; Knox, J.; Dehaeck, B.; Huntington, B.; Rathinam, T.; Ravipati, V.; Ayoade, S.; Gilbert, W.; Adebambo, A.O.; Jatau, I.D.; et al. Re-Calculating the Cost of Coccidiosis in Chickens. Vet Res 2020, 51, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, T.; Abbas, R.Z.; Imran, M.; Abbas, A.; Butt, A.; Aslam, S.; Ahmad, J. Vaccines against Chicken Coccidiosis with Particular Reference to Previous Decade: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Parasitol Res 2022, 121, 2749–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.P. Eimeria of Chickens: The Changing Face of an Old Foe. Avian Pathology 2025, 54, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avi, R.; Reperant, J.M.; Bussiere, F.I.; Silvestre, A.; Le Roux, J.F.; Moreaud, D.; Gonzalez, J. Coccidiosis in Domestic Chickens: A Review of Prevention and Control Strategies[La Coccidiose Chez Les Poulets Domestiques: Revue Sur Les Stratégies de Prévention et de Contrôle]. Inra Productions Animales 2023, 36, 7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, M.; Miska, K.B.; Antonio Casarin Penha Filho, R.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M.; López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J. Overview of Poultry Eimeria Life Cycle and Host-Parasite Interactions. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Salem, H.M.; Attia, M.M.; Yehia, N.; Abdelkader, A.H.; Mawgod, S.A.; Kamel, N.M.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Alsulami, M.N.; Ahmed, A.E.; et al. Alternatives to Antibiotics against Coccidiosis for Poultry Production: The Relationship between Immunity and Coccidiosis Management – a Comprehensive Review. Annals of Animal Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lu, M.; Lillehoj, H.S. Coccidiosis: Recent Progress in Host Immunity and Alternatives to Antibiotic Strategies. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, C.A.F.; Kumar, V.J.A.; Mathivathani, C. Prevalence of Avian Coccidiosis in India: A Review. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2024, 48, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avi, R.; Reperant, J.M.; Bussiere, F.I.; Silvestre, A.; Le Roux, J.F.; Moreaud, D.; Gonzalez, J. Coccidiosis in Domestic Chickens: A Review of Prevention and Control Strategies[La Coccidiose Chez Les Poulets Domestiques: Revue Sur Les Stratégies de Prévention et de Contrôle]. Inra Productions Animales 2023, 36, 7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Ahmed Laloui, H.; Kara, R.; Dems, M.A.; Cherb, N.; Klikha, A.; Blake, D.P. The Financial Cost of Coccidiosis in Algerian Chicken Production: A Major Challenge for the Poultry Sector. Avian Pathology 2024, 53, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbou-Iouknane, N.; Benbarek, H.; Ayad, A. Prevalence and Aetiology of Coccidiosis in Broiler Chickens in Bejaia Province, Algeria. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2018, 85, a1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemai, S.; Ayadi, O.; Khelifi, D.; Bellil, I.; Hide, G. Prevalence of Eimeria Species, Detected by ITS1-PCR, in Broiler Poultry Farms Located in Seven Provinces of Northeastern Algeria. Trop Anim Health Prod 2022, 54, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdelhak, A.C.; Derbak, H.; Titouah, H.; Aissanou, S.; Debbou-Iouknane, N.; Ayad, A. Epidemiological Survey on Post Mortem Coccidiosis in Broiler Chicken in Bejaia Province, Northern Algeria. Acta Parasitol 2024, 69, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, O.; Djemai, S.; Hide, G. Prevalence of Eimeria Species, Detected by ITS1-PCR Immobilized on FTA Cards, in Future Laying Hens and Breeding Hens in Six Provinces in Northeastern Algeria. Acta Parasitol 2024, 69, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, K.; Bachene, M.S.; Mustapha, O.; Hamdi, T.M. Prevalence of Coccidiosis in Broiler Chickens in Medea, Algeria. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2025, 118, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djemai, S.; Mekroud, A.; Jenkins, M.C. Evaluation of Ionophore Sensitivity of Eimeria Acervulina and Eimeria Maxima Isolated from the Algerian to Jijel Province Poultry Farms. Vet Parasitol 2016, 224, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, H.W.; Landman, W.J.M. Higher Incidence of Eimeria Spp. Field Isolates Sensitive for Diclazuril and Monensin Associated with the Use of Live Coccidiosis Vaccination with ParacoxTM-5 in Broiler Farms. Avian Dis 2006, 50, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ren, G.; Si, H.; Song, X.; Liu, X.; Suo, X.; Hu, D. Forward Genetic Analysis of Monensin and Diclazuril Resistance in Eimeria Tenella. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2023, 22, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Si, H.; Liu, X.; Suo, X.; Hu, D. Early Transcriptional Response to Monensin in Sensitive and Resistant Strains of Eimeria Tenella. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 934153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Dong, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.; Jia, L.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Q.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, B.; et al. Integrated Application of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Provides Insight into the Mechanism of Eimeria Tenella Resistance to Maduramycin. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2024, 24, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Huang, B.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, H.; Dong, H.; Han, H. Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Drug-Sensitive and Drug-Resistant Strains of Eimeria Tenella by RNA-Sequencing. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2020, 67, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Shen, J.; Wendlandt, S.; Feßler, A.T.; Wang, Y.; Kadlec, K.; Wu, C.-M. Plasmid-Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococci and Other Firmicutes. Microbiol Spectr 2014, 2, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Feßler, A.T.; Loncaric, I.; Wu, C.; Kadlec, K.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J. Antimicrobial Resistance among Staphylococci of Animal Origin. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ren, G.; Si, H.; Song, X.; Liu, X.; Suo, X.; Hu, D. Forward Genetic Analysis of Monensin and Diclazuril Resistance in Eimeria Tenella. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2023, 22, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Plummer, P.J. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Campylobacter. In Campylobacter: Third Edition; ASM Press, 2014; pp. 263–276 ISBN 9781683671442.

- Bukari, Z.; Emmanuel, T.; Woodward, J.; Ferguson, R.; Ezughara, M.; Darga, N.; Lopes, B.S. The Global Challenge of Campylobacter: Antimicrobial Resistance and Emerging Intervention Strategies. Trop Med Infect Dis 2025, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Chavarrias, V.; Ugarte-Ruiz, M.; Barcena, C.; Olarra, A.; Garcia, M.; Saez, J.L.; de Frutos, C.; Serrano, T.; Perez, I.; Moreno, M.A.; et al. Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance to Aminoglycosides and Macrolides in Campylobacter Coli and Campylobacter Jejuni From Healthy Livestock in Spain (2002–2018). Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 689262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attree, E.; Sanchez-Arsuaga, G.; Jones, M.; Xia, D.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Blake, D.; Tomley, F. Controlling the Causative Agents of Coccidiosis in Domestic Chickens; an Eye on the Past and Considerations for the Future. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience 2021, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Yu, Y.H.; Hua, K.F.; Chen, W.J.; Zaborski, D.; Dybus, A.; Hsiao, F.S.H.; Cheng, Y.H. Management and Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry — A Review. Anim Biosci 2024, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Al-Quraishy, S.; Maodaa, S.N.; Abdel-Gaber, R. In Vitro Studies for Antiparasitic Activities of Punica Granatum Extract. Microsc Res Tech 2023, 86, 1655–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitfella Lahlou, R.; Bounechada, M.; Mohammedi, A.; Silva, L.R.; Alves, G. Dietary Use of Rosmarinus Officinalis and Thymus Vulgaris as Anticoccidial Alternatives in Poultry. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2021, 273, 114826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, A.S.M. Phenolics of Botanical Origin for the Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry. Pak Vet J 2024, 44, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeil, H.; Mira, N.M.; El-Ashram, S.; Dkhil, M.A.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Kasem, S.M. Utilizing Coriander as a Natural Remedy for Combating Eimeria Papillata Infection and Oxidative Stress in Mice. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2025, 19, 2467478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomstrand, B.M.; Enemark, H.L.; Steinshamn, H.; Aasen, I.M.; Johanssen, J.R.E.; Athanasiadou, S.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Sørheim, K.M. Administration of Spruce Bark (Picea Abies) Extracts in Young Lambs Exhibits Anticoccidial Effects but Reduces Milk Intake and Body Weight Gain. Acta Vet Scand 2022, 64, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaniei, A.; Tohidi, E.; Vafaei, A. Efficacy of a Commercial Mixed Botanical Formula in Treatment and Control of Coccidiosis in Poultry[Djelotvornost Komercijalne Biljne Mješavine u Liječenju i Kontroli Kokcidioze Peradi]. Vet Arh 2022, 92, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.C.; Yang, C.Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Yang, C.W.; Li, W.Q.; Chung, C.Y.; Yang, M.T.; Kuo, T.F.; Lin, C.F.; Liang, C.L.; et al. Anti-Coccidial Properties and Mechanisms of an Edible Herb, Bidens Pilosa, and Its Active Compounds for Coccidiosis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felici, M.; Tugnoli, B.; De Hoest-Thompson, C.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E.; Marugan-Hernandez, V. Thyme, Oregano, and Garlic Essential Oils and Their Main Active Compounds Influence Eimeria Tenella Intracellular Development. Animals 2024, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshershaby, R.E.; Dkhil, M.A.; Dar, Y.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Delic, D.; Helal, I.B. Cassia Alata’s Dual Role in Modulating MUC2 Expression in Eimeria Papillata-Infected Jejunum and Assessing Its Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Microsc Res Tech 2024, 87, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Mansoor, M.; Ali, A.; Shahzad, H.; Rizwan-Ul-Haq; Awan, A. A.; Gul, J. Role of Herbal Immunomodulators in Control of Coccidiosis Disease. Pakistan Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research Series B: Biological Sciences 2017, 60, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.A.; Ebeid, T.A.; Abudabos, A.M. Effect of Dietary Phytogenics (Herbal Mixture) Supplementation on Growth Performance, Nutrient Utilization, Antioxidative Properties, and Immune Response in Broilers. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 14606–14613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.R.; Chen, Y.P.; Cheng, Y.F.; Qu, H.M.; Li, J.; Wen, C.; Zhou, Y.M. Effects of Dietary Phytosterols on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Status, and Meat Quality in Partridge Shank Chickens. Poult Sci 2019, 98, 3715–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, K.M.; Ahmed, H.A.; Ayoub, M.; Elsabagh, M. Evaluation of Digestarom and Thyme as Phytogenic Feed Additives for Broiler Chickens[Prüfung von Digestarom Und Thymian Als Phytogene Futterzusatzstoffe Bei Broilern]. European Poultry Science 2014, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, H.; Kermanshahi, H.; Golian, A.; Veldkamp, T. Metabolism and Nutrition: Effect of Thymol and Carvacrol Feed Supplementation on Performance, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, Fatty Acid Composition, Digestive Enzyme Activities, and Immune Response in Broiler Chickens. Poult Sci 2013, 92, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garadi, M.A.; Alhotan, R.A.; Hussein, E.O.; Qaid, M.M.; Suliman, G.M.; Al-Badwi, M.A.; Fazea, E.H.; Olarinre, I.O. Effects of a Natural Phytogenic Feed Additive on Broiler Performance, Carcass Traits, and Gut Health under Diets with Optimal and Reduced Energy and Amino Acid Density. Poult Sci 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amad, A.A.; Männer, K.; Wendler, K.R.; Neumann, K.; Zentek, J. Effects of a Phytogenic Feed Additive on Growth Performance and Ileal Nutrient Digestibility in Broiler Chickens. Poult Sci 2011, 90, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, K.; Hayat, Z.; Latif, H.R.A.; Tariq, Z.; Riaz, T.; Ullah, S.; Jamil, S.; Rehman, S.; Azam, M. Growth Performance and Gut Microbiota of Broilers Administered Different Levels of Mango Seed Kernel Extract. Revista Brasileira de Ciencia Avicola / Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science 2024, 26, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliego, A.B.; Tavakoli, M.; Khusro, A.; Seidavi, A.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Márquez-Molina, O.; Rene Rivas-Caceres, R. Beneficial and Adverse Effects of Medicinal Plants as Feed Supplements in Poultry Nutrition: A Review. Anim Biotechnol 2022, 33, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, G.R.; Syed, B.; Haldar, S.; Pender, C. Phytogenic Feed Additives as an Alternative to Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Broiler Chickens. Front Vet Sci 2015, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraternale, D.; Ricci, D. Essential Oils of Lamiaceae Family Plants as Antifungals. Biomolecules 2020, Vol. 10, Page 103 2020, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uritu, C.M.; Mihai, C.T.; Stanciu, G.D.; Dodi, G.; Alexa-Stratulat, T.; Luca, A.; Leon-Constantin, M.M.; Stefanescu, R.; Bild, V.; Melnic, S.; et al. Medicinal Plants of the Family Lamiaceae in Pain Therapy: A Review. Pain Res Manag 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekut, M.; Brkić, S.; Kladar, N.; Dragović, G.; Gavarić, N.; Božin, B. Potential of Selected Lamiaceae Plants in Anti(Retro)Viral Therapy. Pharmacol Res 2018, 133, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, A.; Duru, M.; analytical, N.M.-E. journal of; 2007, undefined Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Russula Delica Fr: An Edidle Wild Mushroom. researchgate.net 2007, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M. Antioxidant Determinations by the Use of a Stable Free Radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Esin Karademir, S.; Erçǧ, E. The Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity and Polyphenolic Content of Some Herbal Teas. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2006, 57, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, D.P.; McKenzie, M.E.C.N.-S. 6. C.C. 2007 Poultry Coccidiosis: Diagnostic and Testing Procedures; 3rd ed.; Blackwell Pub: Ames, Iowa, 2007; ISBN 978-0-8138-2202-0. [Google Scholar]

- MW REID; BW CALNEK; LR Mc DOUGALD Protozoa-Coccidiosis. In (783-814); Iowa State University Press: Aimes Iowa (USA), 1978; p. 949.

- Reperant JM. Taille Comparée Des Oocystes de Coccidies Du Poulet [Image]. ANSES – Laboratoire de Ploufragan-Plouzané; Ploufragan, 2018.

- Remmal, A.; Achahbar, S.; Bouddine, L.; Chami, N.; Chami, F. In Vitro Destruction of Eimeria Oocysts by Essential Oils. Vet Parasitol 2011, 182, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicines Agency, E. Adoption by the Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP) for Guideline on Quality Data Requirements for Applications for Biological Veterinary Medicinal Products Intended for Limited Markets; 2022.

- Medicines Agency, E. Guideline on Safety and Residue Data Requirements for Applications for Non-Immunological Veterinary Medicinal Products Intended for Limited Markets but Not Eligible for Authorisation under Article 23 of Regulation (EU) 2019/6; 2024.

- FDA CVM GFI #185 (VICH GL43) Target Animal Safety for Veterinary Pharmaceutical Products | FDA; 2009.

- Albretsen, J. Target Animal Safety for Veterinary Pharmaceutical Products. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Safety and Pharmacokinetic Assays 2024, 2515–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Piral, Q.; Naz, S.; Almutairi, M.H.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Ayasan, T.; Khan, R.U.; Losacco, C. Ameliorative Effect of Pomegranate Peel Powder on the Growth Indices, Oocysts Shedding, and Intestinal Health of Broilers under an Experimentally Induced Coccidiosis Condition. Animals 2023, Vol. 13, Page 3790 2023, 13, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Patiño, G.; Camacho-Rea, M.d.C.; Olvera-García, M.E.; Baltazar-Vázquez, J.C.; Gómez-Verduzco, G.; Téllez, G.; Labastida, A.; Ramírez-Pérez, A.H. Effect of an Alliaceae Encapsulated Extract on Growth Performance, Gut Health, and Intestinal Microbiota in Broiler Chickens Challenged with Eimeria Spp. Animals 2023, 13, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hascoët, A.S.; Torres-Celpa, P.; Riquelme-Neira, R.; Hidalgo-Olate, H. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Phytogenic Supplement (Alkaloids and Flavonoids) in the Control of Eimeria Spp. in Experimentally Challenged Broiler Chickens. Animals 2025, 15, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Văcaru-Opriş, I.; Dumitrescu, G.; Petculescu, L.; Marcu, A.; Nicula, M.; Dronca, D.; Kelciov, B. The Influence of Genetics on Economic Efficiency of Broiler Chickens Growth. 2013.

- Chauhan, S.; Singh, V.S.; Thakur, V. Effect of Calotropis Procera (Madar) and Amprolium Supplementation on Parasitological Parameters of Broilers during Mixed Eimeria Species Infection. Vet World 2017, 10, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, P.A.; Conway, D.P.; McKenzie, M.E.; Dayton, A.D.; Chapman, H.D.; Mathis, G.F.; Skinner, J.T.; Mundt, H.C.; Williams, R.B. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (WAAVP) Guidelines for Evaluating the Efficacy of Anticoccidial Drugs in Chickens and Turkeys. Vet Parasitol 2004, 121, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; parasitology, W.R.-E. ; 1970, undefined Anticoccidial Drugs: Lesion Scoring Techniques in Battery and Floor-Pen Experiments with Chickens. Elsevier 1970, 28, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. yun; Di, K. qian; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. fan; Xi, J. zhong; Wang, D.H.; Hao, E. ying; Xu, L. jun; Chen, H.; Zhou, R. yan Effect of Natural Garlic Essential Oil on Chickens with Artificially Infected Eimeria Tenella. ElsevierL Chang, K Di, J Xu, Y Chen, J Xi, DH Wang, E Hao, L Xu, H Chen, R ZhouVeterinary Parasitology, 2021•Elsevier 2021, 300. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Reid, W.M. Anticoccidial Drugs: Lesion Scoring Techniques in Battery and Floor-Pen Experiments with Chickens. Exp Parasitol 1970, 28, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. yun; Di, K. qian; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. fan; Xi, J. zhong; Wang, D.H.; Hao, E. ying; Xu, L. jun; Chen, H.; Zhou, R. yan Effect of Natural Garlic Essential Oil on Chickens with Artificially Infected Eimeria Tenella. Vet Parasitol 2021, 300, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Chand, N.; Naz, S.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Albeshr, M.F.; Losacco, C.; Khan, R.U. Response to Dietary Methionine and Organic Zinc in Broilers against Coccidia under Eimeria Tenella-Challenged Condition. Livest Sci 2023, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petreska Stanoeva, J.; Balshikevska, E.; Stefova, M.; Tusevski, O.; Simic, S.G. Comparison of the Effect of Acids in Solvent Mixtures for Extraction of Phenolic Compounds From Aronia Melanocarpa. Nat Prod Commun 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanoeva, J.P.; Stefova, M.; Bogdanov, J. Systematic HPLC/DAD/MS n Study on the Extraction Efficiency of Polyphenols from Black Goji: Citric and Ascorbic Acid as Alternative Acid Components in the Extraction Mixture. J Berry Res 2021, 11, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabana, R.; Silva, L.R.; Valentão, P.; Viturro, C.I.; Andrade, P.B. Effect of Different Extraction Methodologies on the Recovery of Bioactive Metabolites from Satureja Parvifolia (Phil.) Epling (Lamiaceae). Ind Crops Prod 2013, 48, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, R.A.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Bounechada, M.; Nunes, A.R.; Soeiro, P.; Alves, G.; Moreno, D.A.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Raposo, C.; Silvestre, S.; et al. Antioxidant, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties of Algerian Mentha Aquatica Extracts. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, B.; Anwar, F.; Ashraf, M. Effect of Extraction Solvent/Technique on the Antioxidant Activity of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts. Molecules 2009, 14, 2167–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheigh, C.I.; Yoo, S.Y.; Ko, M.J.; Chang, P.S.; Chung, M.S. Extraction Characteristics of Subcritical Water Depending on the Number of Hydroxyl Group in Flavonols. Food Chem 2015, 168, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.; Pandjaitan, N. Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Flavonoids from Spinach. J Food Sci 2008, 73 3, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Houda Lezoul, N.; Belkadi, M.; Habibi, F.; Guillén, F. Extraction Processes with Several Solvents on Total Bioactive Compounds in Different Organs of Three Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaiee, P.; Taghipour, A.; Vahdatkhoram, F.; Movagharnejad, K. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Mentha Aquatica: The Effects of Sonication Time, Temperature and Drying Method. Chemical Papers 2019, 73, 3067–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, A.; Rahmoune, C.; Boumendjel, M.; Aissi, O.; Messaoud, C. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Six Wild Mentha Species (Lamiaceae) from Northeast of Algeria. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2016, 6, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, H.; Stankov, S.; Petkova, N.; Dincheva, I.; Stoyanova, A.; Dogan, H. Evaluation of the Phytochemical Profile of Water Mint (Mentha Aquatica L.) from Bulgaria. AIP Conf Proc 2023, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, M.S.; De O Silva, A.M.; Carvalho, E.B.; Rivelli, D.P.; Barros, S.B.; Rogero, M.M.; Lottenberg, A.M.; Torres, R.P.; Mancini-Filho, J. Phenolic Compounds from Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) Attenuate Oxidative Stress and Reduce Blood Cholesterol Concentrations in Diet-Induced Hypercholesterolemic Rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2013, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souadia, A.; Djemoui, A.; Souli, L.; Haiouani, K.; Atoki, A.V.; Djemoui, D.; Messaoudi, M.; Hegazy, S.; Alsaeedi, H.; Barhoum, A. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Maximizing Total Phenolics, Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity in Thymus Algeriensis: Box-Behnken Experimental Design. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, B.E.C.; Heleno, S.A.; Bachari, K.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Compounds Characterization by LC-DAD- ESI/MSn and Bioactive Properties of Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. & Reut. and Ephedra Alata Decne. Food Research International 2019, 116, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tompkins, Y.H.; Choi, J.; Teng, P.Y.; Yamada, M.; Sugiyama, T.; Kim, W.K. Reduced Bone Formation and Increased Bone Resorption Drive Bone Loss in Eimeria Infected Broilers. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griss, L.G.; Galli, G.M.; Fracasso, M.; Silva, A.D.; Fortuoso, B.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Morch, V.M.; Boiago, M.M.; Gris, A.; Mendes, R.E.; et al. Oxidative Stress Linked to Changes of Cholinesterase and Adenosine Deaminase Activities in Experimentally Infected Chicken Chicks with Eimeria Spp. Parasitol Int 2019, 71, 11–17. Parasitol Int 2019, 71, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, A.F.A.; Schneiders, G.H.; Richter, J.N.; Foutz, J.C.; Milfort, M.C.; Fuller, A.L.; Yuan, J.; Rekaya, R.; Aggrey, S.E. Heat Stress Modulates the Disruptive Effects of Eimeria Maxima Infection on the Ileum Nutrient Digestibility, Molecular Transporters, and Tissue Morphology in Meat-Type Chickens. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0269131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel Total Antioxidant Capacity Index for Dietary Polyphenols and Vitamins C and E, Using Their Cupric Ion Reducing Capability in the Presence of Neocuproine: CUPRAC Method. J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT - Food Science and Technology 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, N.; Oberoi, H.S.; Sandhu, S.K.; Bhargav, V.K. Influence of Different Solvents in Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Vegetable Residues and Their Evaluation as Natural Sources of Antioxidants. J Food Sci Technol 2012, 51, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Jain, D.C.; Gupta, M.M.; Bhakuni, R.S.; Mishra, H.O.; Sharma, R.P. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatographic Analysis of Hepatoprotective Diterpenoids from Andrographis Paniculata. Phytochemical Analysis 2000, 11, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchi, C.; Binello, A.; Rubiolo, P. Determination of Phenolic Diterpene Antioxidants in Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) with Different Methods of Extraction and Analysis. Phytochemical Analysis 2000, 11, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, O.R.; Macias, R.I.R.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Cardoso, S.M. Hepatoprotection of Mentha Aquatica L., Lavandula Dentata L. and Leonurus Cardiaca L. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhtalab, E.; Nikokar, I.; Mojtahedi, A.; Shokri, R.; Karimian, P.; Mahdavi, E.; Faezi, S. Encapsulation of Mentha Aquatica Methanol Extract in Alginate Hydrogel Promotes Wound Healing in a Murine Model of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Burn Infection. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 280, 135920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megdiche-Ksouri, W.; Saada, M.; Soumaya, B.; Snoussi, M.; Zaouali, Y.; Ksouri, R. Potential Use of Wild Thymus Algeriensis and Thymus Capitatus as Source of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Agents. Journal of New Sciences 2015, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Righi, N.; Boumerfeg, S.; Fernandes, P.A.R.; Deghima, A.; Baali, F.; Coelho, E.; Cardoso, S.M.; Coimbra, M.A.; Baghiani, A. Thymus Algeriensis Bioss & Reut: Relationship of Phenolic Compounds Composition with in Vitro/in Vivo Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity. Food Research International 2020, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, O.; Fahima, A.; Hassani, A. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oil of Thymus Algeriensis Boiss, North Algeria. International Letters of Chemistry, Physics and Astronomy 2015, 59, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencharif-Betina, S.; Benhamed, N.; Benabdallah, A.; Bendif, H.; Benslama, A.; Negro, C.; Plavan, G.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; De Bellis, L. A Multi-Approach Study of Phytochemicals and Their Effects on Oxidative Stress and Enzymatic Activity of Essential Oil and Crude Extracts of Rosmarinus Officinalis. Separations 2023, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahunie, A. Effect of Rosmarinus Officinalis and Origanum Majorana Extracts on Stability of Sunflower Oil during Storage and Repeated Heating. Oil Crop Science 2024, 9, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doozakhdarreh, K.; Fatemeh, S.; Khorshidi, J.; Morshedloo, M.R. Essential Oil Content and Components, Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenol Content of Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) as Affected by Harvesting Time and Drying Method. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2022, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, S.S.; Pelvan, E.; Karadeniz, B. Optimization of Accelerated Solvent Extraction, Ultrasound Assisted and Supercritical Fluid Extraction to Obtain Carnosol, Carnosic Acid and Rosmarinic Acid from Rosemary. Sustain Chem Pharm 2024, 37, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camargo, A.P.; Mendiola, J.A.; Valdés, A.; Castro-Puyana, M.; García-Cañas, V.; Cifuentes, A.; Herrero, M.; Ibáñez, E. Supercritical Antisolvent Fractionation of Rosemary Extracts Obtained by Pressurized Liquid Extraction to Enhance Their Antiproliferative Activity. J Supercrit Fluids 2016, 107, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejenaru, L.E.; Biţă, A.; Mogoşanu, G.D.; Segneanu, A.-E.; Radu, A.; Ciocîlteu, M.V.; Bejenaru, C. Polyphenols Investigation and Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Activities of Rosmarinus Officinalis L. Species from Southwest Romania Flora. Molecules 2024, 29, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokbulut, I.; Karaman, Y.; Tursun, A.O. Chemical Composition Phenolic, Antioxidant, and Bio-Herbicidal Properties of the Essential Oil of Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.). Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus 2022, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D.; Rathinam, T. Focused Review: The Role of Drug Combinations for the Control of Coccidiosis in Commercially Reared Chickens. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2022, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.A.; Niepceron, A.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sedano, L.; Hehl, A.B.; Brossier, F.; Smith, N.C. Discovery of a Tyrosine-Rich Sporocyst Wall Protein in Eimeria Tenella. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushkin, G.G.; Motari, E.; Carpentieri, A.; Dubey, J.P.; Costello, C.E.; Robbins, P.W.; Samuelson, J. Evidence for a Structural Role for Acid-Fast Lipids in Oocyst Walls of Cryptosporidium, Toxoplasma, and Eimeria. mBio 2013, 4, e00387–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, K.; Sharman, P.A.; Walker, R.A.; Katrib, M.; de Souza, D.; McConville, M.J.; Wallach, M.G.; Belli, S.I.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Smith, N.C. Oocyst Wall Formation and Composition in Coccidian Parasites. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, W.M.; Abolhadid, S.M.; Moawad, A.; Abdelaty, A.S.; Moawad, U.K.; Shokier, K.A.M.; Shehata, O.; Gadelhaq, S.M. Thymol Efficacy against Coccidiosis in Pigeon (Columba Livia Domestica). Prev Vet Med 2020, 176, 104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shall, N.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Albaqami, N.M.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.E.; Swelum, A.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; AbuQamar, S.F.; et al. Phytochemical Control of Poultry Coccidiosis: A Review. Poult Sci 2021, 101, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felici, M.; Tugnoli, B.; Ghiselli, F.; Massi, P.; Tosi, G.; Fiorentini, L.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. In Vitro Anticoccidial Activity of Thymol, Carvacrol, and Saponins. Poult Sci 2020, 99, 5350–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitviriyanon, S.; Phanthong, P.; Lomarat, P.; Bunyapraphatsara, N.; Porntrakulpipat, S.; Paraksa, N. In Vitro Study of Anti-Coccidial Activity of Essential Oils from Indigenous Plants against Eimeria Tenella. Vet Parasitol 2016, 228, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelhaq, S.M.; Arafa, W.M.; Abolhadid, S.M. In Vitro Activity of Natural and Chemical Products on Sporulation of Eimeria Species Oocysts of Chickens. Vet Parasitol 2018, 251, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maodaa, S.N.; Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Qaid Hailan, W.A.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Alatawi, A.; Alawwad, S.A.; Al-Quraishy, S. In Vitro Sporulation, Oocysticidal Sporulation Inhibition of Eimeria Papillate and Cytotoxic Efficacy of Methanolic Extract of Thymus Daenensis Leaves. Indian J Anim Res 2024, 58, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, A. In Vitro Evaluation of Oocysticidal and Sporulation Inhibition Effects of Essential Oil of Orange (Citrus Sinensis) Against Eimeria Tenella. Journal of Animal Research 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dkhil, M.A. Anti-Coccidial, Anthelmintic and Antioxidant Activities of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum) Peel Extract. Parasitol Res 2013, 112, 2639–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulou, E.; Skoufos, I.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Giannenas, I.; Bonos, E.; Aguiar-Martins, K.; Lazari, D.; Blake, D.P.; Tzora, A. In Vitro Anticoccidial Study of Oregano and Garlic Essential Oils and Effects on Growth Performance, Fecal Oocyst Output, and Intestinal Microbiota in Vivo. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felici, M.; Tugnoli, B.; Ghiselli, F.; Baldo, D.; Ratti, C.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Investigating the Effects of Essential Oils and Pure Botanical Compounds against Eimeria Tenella in Vitro. Poult Sci 2023, 102, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.M.; Varga, E.; Coroian, M.; Nedișan, M.E.; Mircean, V.; Dumitrache, M.O.; Farczádi, L.; Fülöp, I.; Croitoru, M.D.; Fazakas, M.; et al. Efficacy of a Commercial Herbal Formula in Chicken Experimental Coccidiosis. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arczewska-Wlosek, A.; Swiatkiewicz, S.; Ognik, K.; Jozefiak, D. Effect of Dietary Crude Protein Level and Supplemental Herbal Extract Blend on Selected Blood Variables in Broiler Chickens Vaccinated against Coccidiosis. Animals 2018, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arczewska-Włosek, A.; Świątkiewicz, S.; Kowal, J.; Józefiak, D.; Długosz, J. The Effect of Increased Crude Protein Level and/or Dietary Supplementation with Herbal Extract Blend on the Performance of Chickens Vaccinated against Coccidiosis. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2017, 229, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.A.; Qureshi, N.A.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Alhewairini, S.S.; Saleem, A.; Zeb, A. Characterization and Bioactivities of M. Arvensis, V. Officinalis and P. Glabrum: In-Silico Modeling of V. Officinalis as a Potential Drug Source. Saudi J Biol Sci 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, S.; Shariatmadari, F.; Karimi Torshizi, M.A.; Ahmadi, H.; Scholey, D. Plectranthus Amboinicus and Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) Essential Oils Effects on Performance, Antioxidant Activity, Intestinal Health, Immune Response, and Plasma Biochemistry in Broiler Chickens. Food Sci Nutr 2023, 11, 3939–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlala, T.; Okpeku, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Understanding the Interactions between Eimeria Infection and Gut Microbiota, towards the Control of Chicken Coccidiosis: A Review. Parasite 2021, 28, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Elkhair, R.; Gaafar, K.; Helal, M.; Sameh, G. Bioactive Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Essential Oils Blend of Oregano, Thyme and Garlic Oils on Performance of Broilers Infected with Eimeria Species. Glob Vet 2014, 13, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Malekzadeh, M.; Shakouri, M.D.; Abdi Benamar, H. Effect of Thyme Species Extracts on Performance, Intestinal Morphometry, Nutrient Digestibility and Immune Response of Broilers. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg 2018, 24, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, O.; El-Sebai, A.; El-Motaal, S.A.; Khalifa, H.A. Experimental Trials to Assess the Immune Modulatory Influence of Thyme and Ginseng Oil on NDV-Vaccinated Broiler Chickens. Open Vet J 2024, 14, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.M.; Awad, A. Impact of Thyme Powder (Thymus Vulgaris L.) Supplementation on Gene Expression Profiles of Cytokines and Economic Efficiency of Broiler Diets. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 15816–15826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, E.A.; Aldhalmi, A.K.; Elolimy, A.A.; Madkour, M.; Elsherbeni, A.I.; Alqhtani, A.H.; Khan, I.M.; Swelum, A.A. Optimizing Broiler Performance, Carcass Traits, and Health: Evaluating Thyme and/or Garlic Powders as Natural Growth Promoters in Antibiotic-Free Diets. Poult Sci 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golshahi, A.; Shams Shargh, M.; Dastar, B.; Rahmatnejad, E. The Effect of Thymus Vulgaris Extract and Probiotic on Growth Performance, Blood Parameters, Intestinal Morphology, and Litter Quality of Broiler Chickens Fed Low-Protein Diets. Poult Sci 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, H.; Kermanshahi, H.; Golian, A.; Veldkamp, T. Effect of Thymol and Carvacrol Feed Supplementation on Performance, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, Fatty Acid Composition, Digestive Enzyme Activities, and Immune Response in Broiler Chickens. Poult Sci 2013, 92 8, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçin, S.; Eser, H.; Onbaşilar, İ.; Yalçin, S. Effects of Dried Thyme (Thymus Vulgaris L.) Leaves on Performance, Some Egg Quality Traits and Immunity in Laying Hens. Ankara Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi 2020, 67, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.M.; Awad, A. Impact of Thyme Powder (Thymus Vulgaris L.) Supplementation on Gene Expression Profiles of Cytokines and Economic Efficiency of Broiler Diets. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 15816–15826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkarimi, R.; Daneshyar, M.; Aghazadeh, A. Thyme (Thymus Vulgaris) Extract Consumption Darkens Liver, Lowers Blood Cholesterol, Proportional Liver and Abdominal Fat Weights in Broiler Chickens. Ital J Anim Sci 2011, 10, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Naz, S.; Nikousefat, Z.; Tufarelli, V.; Laudadio, V. Thymus Vulgaris: Alternative to Antibiotics in Poultry Feed. Worlds Poult Sci J 2012, 68, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami-Ahangaran, M.; Ahmadi-Dastgerdi, A.; Azizi, S.; Basiratpour, A.; Zokaei, M.; Derakhshan, M. Thymol and Carvacrol Supplementation in Poultry Health and Performance. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, G. Effect of Probiotics on the Performance and Intestinal Health of Broiler Chickens Infected with Eimeria Tenella. Vaccines 2022, Vol. 10, Page 97 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Hao, X.; Liu, K.; Liu, H. Protective Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum P8 on Growth Performance, Intestinal Health, and Microbiota in Eimeria-Infected Broilers. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 705758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Ashmawy, E.S.; Mourad, D.M.; Amin, S.A.; Khalfallah, E.K.M.; Mohamed, Z.S. Effect of Oregano Essential Oils and Probiotics Supplementation on Growth Performance, Immunity, Antioxidant Status, Intestinal Microbiota, and Gene Expression in Broilers Experimentally Infected with Eimeria. Livest Sci 2025, 291, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, R.A.; Samba, N.; Soeiro, P.; Alves, G.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Silva, L.R.; Silvestre, S.; Rodilla, J.; Ismael, M.I. Thymus Hirtus Willd. Ssp. Algeriensis Boiss. and Reut: A Comprehensive Review on Phytochemistry, Bioactivities, and Health-Enhancing Effects. Foods 2022, 11, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben El Hadj Ali, I.; Chaouachi, M.; Bahri, R.; Chaieb, I.; Boussaïd, M.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Allelopathic and Insecticidal Activities of Essential Oil of Thymus Algeriensis Boiss. et Reut. Ind Crops Prod 2015, 77, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalamkari, G.; Toghyani, M.; Landy, N.; Tavalaeian, E. Investigation the Effects Using Different Levels of Mentha Pulegium L. (Pennyroyal) in Comparison with an Antibiotic Growth Promoter on Performance, Carcass Traits and Immune Responses in Broiler Chickens. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012, 2, S1396–S1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Nanekarani, S. Effects of Feeding Mentha Pulegium L. as an Alternative to Antibiotics on Performance of Broilers. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 8, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ölmez, Μ.; Yörük, Μ. Effects of Dietary Pennyroyal (Mentha Pulegium L.) Dietary Supplementation on Performance, Carcass Quality, Biochemical Parameters and Duodenal Histomorphology of Broilers. Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society 2021, 72, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, B.; Movahhedkhah, S.; Seidavi, A.; Paz, E.; Laudadio, V.; Ayasan, T.; Mail, V.T. Effect of Pennyroyal (Mentha Pulegium L.) Extract on Performance, Blood Constitutes, Immunity Parameters and Intestinal Microflora in Broiler Chickens. Indian J Anim Sci 2021, 90, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.J. Impact of Adding Aqueous Extract of Mentha Pulegium and Lemon and Its Mixture to Drinking Water on Some Growth Performance and Intestine Organs of Broiler Chicken. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2023, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisawa, Y.; Kataoka, M.; Kitano, N.; Matsuzawa, T. Studies on Anticoccidial Agents. 10. Synthesis and Anticoccidial Activity of 5-Nitronicotinamide and Its Analogs. ACS PublicationsY Morisawa, M Kataoka, N Kitano, T MatsuzawaJournal of Medicinal Chemistry, 1977•ACS Publications 1977, 20, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Zuo, B.; Ding, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Du, A. Anticoccidial Evaluation of a Traditional Chinese Medicine—Brucea Javanica—in Broilers. Poult Sci 2016, 95, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, S.A.; Ghaniei, A.; Sadr, S.; Amiri, A.A.; Tavanaee Tamannaei, A.E.; Charbgoo, A.; Ghiassi, S.; Dianat, B. Anticoccidial Effects of Tannin-Based Herbal Formulation (Artemisia Annua, Quercus Infectoria, and Allium Sativum) against Coccidiosis in Broilers. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2023, 47, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavinasab, S.S.; Bozorgmehrifard, M.H.; Kiaei, S.M.M.; Rahbari, S.; Charkhkar, S. Comparison of the Effects of Herbal Compounds and Chemical Drugs for Control of Coccidiosis in Broiler Chickens. Bulg J Vet Med 2022, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, S.; Tanveer, S.; Nawchoo, I.A.; Malik, T.A. Anticoccidial Activity of Artemisia Vestita (Anthemideae, Asteraceae) - a Traditional Herb Growing in the Western Himalayas, Kashmir, India. Microb Pathog 2017, 104, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arczewska-Włosek, A.; Świątkiewicz, S. The Efficacy of Selected Feed Additives in the Prevention of Broiler Chicken Coccidiosis under Natural Exposure to Eimeria Spp. Annals of Animal Science 2015, 15, 725–735. Annals of Animal Science 2015, 15, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.; Györke, A.; Pop, I.; Friss, Z.; Bărburaș, D.; Andra; Toma-Naic; Zsuzsa; Kálmar; Virgínia; et al. Artemisia Annua Improves Chickens Performances but Has Little Anticoccidial Effect in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, L.K.; Campestrini, L.H.; Yamassaki, F.T.; Buzatti, A.; Maurer, J.B.B.; Baggio, S.F.Z.; Magalhães, P.M. de; Molento, M.B. Efeito anticoccidiano de extrato hidroalcoólico de Artemisia annua em camas de aves contaminadas com Eimeria sp. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 2015, 35, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Alsayeqh, A. Anticoccidial Efficacy of Citrus Sinensis Essential Oil in Broiler Chicken. The Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2022, 42, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Piral, Q.; Naz, S.; Almutairi, M.H.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Ayasan, T.; Khan, R.U.; Losacco, C. Ameliorative Effect of Pomegranate Peel Powder on the Growth Indices, Oocysts Shedding, and Intestinal Health of Broilers under an Experimentally Induced Coccidiosis Condition. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhotan, R.A.; Abudabos, A. Anticoccidial and Antioxidant Effects of Plants Derived Polyphenol in Broilers Exposed to Induced Coccidiosis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 14194–14199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maratea, K.A.; Miller, M.A. Abomasal Coccidiosis Associated with Proliferative Abomasitis in a Sheep. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2007, 19, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Liu, G.; White, D.L.; Kim, W.K. Graded Levels of Eimeria Infection Linearly Reduced the Growth Performance, Altered the Intestinal Health, and Delayed the Onset of Egg Production of Hy-Line W-36 Laying Hens When Infected at the Prelay Stage. Poult Sci 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneiders, G.H. Ontogeny of Intestinal Permeability in Chickens Infected with Eimeria Maxima: Implications for Intestinal Health. 2020.

- Chen, P.; Rehman, M.U.; He, Y.; Li, A.; Jian, F.; Zhang, L.; Huang, S. Exploring the Interplay between Eimeria Spp. Infection and the Host: Understanding the Dynamics of Gut Barrier Function. Vet Q 2025, 45, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, P.M.; Miska, K.B.; Jenkins, M.C.; Yan, X.; Proszkowiec-Weglarz, M. Effects of Eimeria Acervulina Infection on the Luminal and Mucosal Microbiota of the Cecum and Ileum in Broiler Chickens. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Tang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Suo, J.; Jia, Y.; El-Ashram, S.; et al. Influence of Eimeria Falciformis Infection on Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Pathways in Mice. Infect Immun 2018, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlala, T.; Okpeku, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Understanding the Interactions between Eimeria Infection and Gut Microbiota, towards the Control of Chicken Coccidiosis: A Review. Parasite 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, J.; Whitmore, M.A.; Tobin, I.; Kim, D.M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, G. Dynamic Response of the Intestinal Microbiome to Eimeria Maxima-Induced Coccidiosis in Chickens. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Liu, G.; White, D.L.; Kim, W.K. Graded Levels of Eimeria Infection Linearly Reduced the Growth Performance, Altered the Intestinal Health, and Delayed the Onset of Egg Production of Hy-Line W-36 Laying Hens When Infected at the Prelay Stage. Poult Sci 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Goo, D.; Sharma, M.K.; Ko, H.; Liu, G.; Paneru, D.; Choppa, V.S.R.; Lee, J.; Kim, W.K. Effects of Different Eimeria Inoculation Doses on Growth Performance, Daily Feed Intake, Gut Health, Gut Microbiota, Foot Pad Dermatitis, and Eimeria Gene Expression in Broilers Raised in Floor Pens for 35 Days. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.; Al-Tamimi, J.; Aljawdah, H.M.A.; Al-Quraishy, S. Pharmacological Effects of Grape Leaf Extract Reduce Eimeriosis-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Status Change, and Goblet Cell Response in the Jejunum of Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maodaa, S.; Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Alatawi, A.; Alawwad, S.; Alhomoud, D.; Al-Quraishy, S. Anticoccidial and Antioxidant Activities of an Ethanolic Extract of Teucrium Polium Leaves on Eimeria Papillate-Infected Mice. Vet Sci 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, M.A.A.; Dkhil, M.A.; Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Murshed, M.; Mares, M.; Al-Quraishy, S. Rumex Nervosus Leaf Extracts Enhance the Regulation of Goblet Cells and the Inflammatory Response during Infection of Chickens with Eimeria Tenella. J King Saud Univ Sci 2020, 32, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.Y.; Yang, Y.Q.; Liu, M.J.; Li, J.G.; Cui, Y.; Yin, S.J.; Tao, J.P. Artemisinin and Artemisia Annua Leaves Alleviate Eimeria Tenella Infection by Facilitating Apoptosis of Host Cells and Suppressing Inflammatory Response. Vet Parasitol 2018, 254, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthamilselvan, T.; Kuo, T.F.; Wu, Y.C.; Yang, W.C. Herbal Remedies for Coccidiosis Control: A Review of Plants, Compounds, and Anticoccidial Actions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Lee, Y.; Adetunji, A.O.; Omaliko, P.C.; Kang, H.W.; Fasina, Y.O. Use of Selected Plant Extracts in Controlling and Neutralizing Toxins and Sporozoites Associated with Necrotic Enteritis and Coccidiosis. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Hu, W.; Chen, T.; Guo, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, F. Anticoccidial Activity of Natural Plants Extracts Mixture against Eimeria Tenella: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Duan, J.; He, X.; Xie, K.; Song, Z. Effects of Dietary Water-Soluble Extract of Rosemary Supplementation on Growth Performance and Intestinal Health of Broilers Infected with Eimeria Tenella. J Anim Sci 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjitraresmi, A.; Moektiwardoyo, M.; Susilawati, Y.; Shiono, Y. Antimalarial Activity of Lamiaceae Family Plants: Review. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 2020, 11, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailén, M.; Illescas, C.; Quijada, M.; Martínez-Díaz, R.A.; Ochoa, E.; Gómez-Muñoz, M.T.; Navarro-Rocha, J.; González-Coloma, A. Anti-Trypanosomatidae Activity of Essential Oils and Their Main Components from Selected Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, M.S.P.; Reis, A.S. dos; Fidelis, Q.C. Antileishmanial Potential of Species from the Family Lamiaceae: Chemical and Biological Aspects of Non-Volatile Compounds. Acta Trop 2022, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felici, M.; Tugnoli, B.; De Hoest-Thompson, C.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E.; Marugan-Hernandez, V. Thyme, Oregano, and Garlic Essential Oils and Their Main Active Compounds Influence Eimeria Tenella Intracellular Development. Animals 2023, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plants | Geographic coordinates | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mentha aquatica | 36°10'49.1"N 4°36'43.6"E | AQ: 21.640 ± 1.619 |

| HM: 19.300 ± 0.080 | ||

| Rosmarinus officinalis | 36°11'00.4"N 4°25'53.7"E | AQ: 18.577 ± 3.696 |

| HM: 15.913 ± 4.110 | ||

| Thymus algeriensis | 36°10'49.1"N 4°36'43.6"E | AQ: 11.675 ± 0.625 |

| HM: 11.455 ± 0.010 |

| Category | Substance | Quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starter (1 to 21 days) | Grower (22 to 42 d) | ||

| Trace Elements | Iron | 5000 mg | 5000 mg |

| Copper | 1000 mg | 1000 mg | |

| Zinc | 5000 mg | 5000 mg | |

| Manganese | 7500 mg | 7500 mg | |

| Iodine | 150 mg | 150 mg | |

| Selenium | 20 mg | 20 mg | |

| Vitamins | Vitamin A | 15000 IU | 10000 IU |

| Vitamin D3 | 3000 IU | 2000 IU | |

| Vitamin E | 100 mg | 100 mg | |

| Vitamin K3 | 150 mg | 150 mg | |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) | 125 mg | 125 mg | |

| Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | 400 mg | 400mg | |

| Vitamin PP (Nicotinic acid) | 2500 mg | 2500 mg | |

| Vitamin B5 (Calcium pantothenate) | 825 mg | 825 mg | |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | 200 mg | 200 mg | |

| Vitamin H (Biotin) | 5 mg | 5 mg | |

| Vitamin B9 (Folic acid) | 55 mg | 55 mg | |

| Vitamin B12 (Cyanocobalamin) | 1.25 mg | 1.25mg | |

| Technical Parameters | Choline chloride | 30000 mg | 30000 mg |

| Crude ash | 12% | 8% | |

| Calcium | 1.20% | 1% | |

| Sodium | 0.20% | 0.25% | |

| Crude protein | 21.70% | 20% | |

| Methionine + Betaine | 180000 mg | 100000 mg | |

| Metabolisable energy | 2850 kcal/kg | 3100 kcal/kg | |

| Additional Nutrients | Lysine | 1.30% | 1.10% |

| Threonine | 0.80% | 0.75% | |

| Tryptophan | 0.20% | 0.20% | |

| Arginine | 1.30% | 1.20% | |

| Phosphorus | 0.50% | 0.45% | |

| Fat content | 3.50% | 5% | |

| Crude fiber | 4% | 4% | |

| Ingredients | Corn | 55% | 55% |

| Soybean | 25% | 0.25 | |

| Wheat Bran | 10% | 10% | |

| Group | Infection status | Treatment description | Parasite dosage1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (TH-AQ1) | Infected | Thymus algeriensis aqueous extract, 15 mL/L (1.5g/L) | 10000 |

| B (TH-AQ2) | Infected | Thymus algeriensis aqueous extract, 50 mL/L (5g/L) | 10000 |

| C (RO-AQ1) | Infected | Rosmarinus officinalis methanolic extract, 15 mL/L (1.5g/L) | 10000 |

| D (RO-AQ2) | Infected | Rosmarinus officinalis methanolic extract, 50 mL/L (5g/L) | 10000 |

| E (ME-AQ1) | Infected | Mentha aquatica methanolic extract, 15 mL/L (1.5g/L) | 10000 |

| F (ME-AQ2) | Infected | Mentha aquatica methanolic extract, 50 mL/L (5g/L) | 10000 |

| G (NINT) | Uninfected | Untreated (blank control) | - |

| H (INT) | Infected | Untreated (negative control) | 10000 |

| I (Toltrazuril) | Infected | Toltrazuril, 7 mg/kg BW for 5 days (positive control) | 10000 |

| Samples | Aqueous extracts | Hydromethanolic extracts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | TPC1 | TFC1 | TPC1 | TFC1 |

| Rosmarinus officinalis | 160.96 ± 6.55 | 49.26 ± 0.40 | 215.50 ± 17.19 | 33.26 ± 1.40 |

| Thymus algeriensis | 128.11 ± 10.56 | 15.20 ± 2.30 | 220.35 ± 5.92 | 28.05 ± 1.31 |

| Mentha aquatica | 167.139 ± 26.48 | 29.56 ± 2.58 | 199.26 ± 12.26 | 59.77 ± 4.07 |

| Extracts | Aqueous extracts* | Hydromethanolic extracts* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | CUPRAC | DPPH | CUPRAC | |

| Rosmarinus officinalis | 16.37 ± 0.01 | 18.80 ± 0.02 | 15.74 ± 0.69 | 14.50 ± 0.14 |

| Thymus algeriensis | 17.18 ± 0.09 | 15.65 ± 0.58 | 15.56 ± 0.63 | 11.72 ± 0.85 |

| Mentha aquatica | 12.79 ± 0.05 | 12.06 ± 0.60 | 10.19± 0.51 | 9.47 ± 0.19 |

| BHA | 5.73 ± 0.41 | 3.64 ± 0.19 | 5.73 ± 0.41 | 3.64 ± 0.19 |

| BHT | 22.32 ± 1.19 | 9.62 ± 0.87 | 22.32 ± 1.19 | 9.62 ± 0.87 |

| Plants extracts | Aqueous extracts* | Hydromethanolic extracts* |

|---|---|---|

| Rosmarinus officinalis | 699.11 ± 4.61 | 233.14 ± 3.56 |

| Thymus algeriensis | 3449.56 ± 2.53 | 2621.62 ± 2.90 |

| Mentha aquatica | 329.86 ± 2.78 | 967.11 ± 2.58 |

| Sulfaquinoxalin sodic trimethoprim | NA | |

| Toltrazuril | NA | |

| Extract | Slope ± SE (10-³ % mL/mg) | 95 % CI slope | Y-intercept ± SE (%) | R² | Sy.x | Equation | p (slope) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO-AQ | −24.07 ± 4.63 | −34.74 – −13.40 | 80.56 ± 8.35 | 0.772 | 19.03 | y = -4.814301x + 80.56027 | 0.0008 |

| TH-AQ | −14.24 ± 1.73 | −18.22 – −10.26 | 93.82 ± 3.12 | 0.895 | 7.10 | y = -2.848292x + 93.82187 | <0.0001 |

| ME-AQ | −20.11 ± 4.71 | −30.97 – −9.25 | 63.32 ± 8.50 | 0.695 | 19.36 | y = -4.022062x + 63.31536 | 0.0027 |

| RO-HM | −11.83 ± 1.84 | −16.08 – −7.58 | 48.63 ± 3.32 | 0.838 | 7.57 | y = -2.365649x + 48.63178 | 0.0002 |

| TH-HM | −11.70 ± 1.37 | −14.85 – −8.55 | 81.90 ± 2.47 | 0.902 | 5.62 | y = -2.340540x + 81.90387 | <0.0001 |

| ME-HM | −18.64 ± 2.39 | −24.14 – −13.14 | 73.66 ± 4.31 | 0.884 | 9.81 | y = -3.727003x + 73.66176 | <0.0001 |

| Period | TH-AQ1 | TH-AQ2 | RO-AQ1 | RO-AQ2 | ME-AQ1 | ME-AQ2 | NINF-NT | INF-NT | TOTRA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWG | 1d | 44.39 ± 7.60 | 43.37 ±5.51 | 43.38 ± 6.78 | 43.36 ± 7.20 | 43.35 ± 0.07 | 43.38 ± 0.06 | 42.66 ± 2.21 | 43.31 ± 0.58 | 43.14± 0.39 |

| 7dA | 182.72 ± 0.04 | 187.80 ± 6.98 | 183.76 ± 1.36 | 183.39 ± 0.52 | 182.67 ± 0.90 | 182.95 ± 0.09 | 182.68 ± 0.07 | 180.75 ± 6.14 | 182.58± 0.73 | |

| 10dB | 221.15 ± 1.25 | 221.15 ± 1.26 | 221.15 ± 1.27 | 221.15 ± 1.28 | 221.15 ± 1.29 | 221.15 ± 1.30 | 221.15 ± 1.31 | 221.15 ± 1.32 | 221.15± 1.33 | |

| 10d PI | 877.97 ± 3.25a | 788.35 ± 1.70b | 718.20 ± 3.84c | 757.82 ± 1.99d | 641.50 ± 8.00e | 643.38 ± 5.53e | 685.12 ± 1.25f | 448.75 ± 4.18g | 835.74± 1.25h | |

| 20d PI | 1987.74 ± 2.21a | 1777.37 ± 2.17b | 1237.94 ± 3.91c | 1525.97 ± 0.17d | 714.48 ± 2.57e | 658.59 ± 4.34f | 985.43 ± 1.67g | 583.02 ± 3.09h | 1722.06± 1.78i | |

| 32d PI | 2319.55 ± 43.56a | 2182.15 ± 2.52b | 1674.40 ± 0.75c | 1770.24 ± 7.93 | 987.97 ± 12.26e | 757.82 ± 1.99f | 1131.39 ± 5.41g | 902.17 ± 9.12h | 2143.27± 7.64i | |

| TWG | C | 656.82 ± 3.13a | 567.20 ± 1.53b | 497.05 ± 2.62c | 536.68 ± 2.38b | 421.02 ± 7.92d | 421.83 ± 4.62d | 463.98 ± 1.69e | 227.89 ± 2.89f | 614.59 ± 1.39g |

| D | 1109.77 ± 1.18a | 989.02 ± 3.14b | 519.74 ± 1.30c | 768.14 ± 1.59d | 72.32 ± 8.03e | 15.60 ± 7.46f | 300.30 ± 2.16g | 133.98 ± 5.87h | 886.32 ± 1.28i | |

| E | 331.81 ± 37.35b | 404.79 ± 0.91a | 436.46 ± 3.80a | 244.27 ± 6.37c | 273.49 ± 11.28c | 99.24 ± 5.17d | 145.96 ± 4.98e | 319.15 ± 5.36b | 421.20 ± 5.92a | |

| F | 2098.40 ± 35.05a | 1961.01 ± 2.29b | 1453.26 ± 1.57c | 1549.09 ± 7.00d | 766.82 ± 9.20e | 536.68 ± 2.38f | 910.24 ± 5.06g | 681.02 ± 8.46h | 1922.12 ± 7.09i | |

| ADG | C | 65.68 ± 0.31a | 56.72 ± 0.15b | 49.71 ± 0.26c | 53.67 ± 0.24d | 42.10 ± 0.79e | 42.18 ± 0.46e | 46.40 ± 0.17f | 22.79 ± 0.29g | 61.46± 0.14h |

| D | 110.98 ± 0.12a | 98.90 ± 0.31b | 51.97 ± 0.13c | 76.81 ± 0.16d | 7.23 ± 0.80e | 1.56 ± 0.75f | 30.03 ± 0.22g | 13.40 ± 0.59h | 88.63± 0.13i | |

| E | 27.65 ± 3.11a | 33.73 ± 0.08b | 36.37 ± 0.32b | 20.36 ± 0.53c | 22.79 ± 0.94d | 8.27 ± 0.43e | 12.16 ± 0.41f | 26.60 ± 0.45a | 35.10± 0.49b | |

| F | 65.58 ± 1.10b | 61.28 ± 0.07a | 45.41 ± 0.05c | 48.41 ± 0.22d | 23.96 ± 0.29e | 16.77 ± 0.07f | 28.45 ± 0.16g | 21.28 ± 0.26h | 60.07± 0.22a | |

| FI | C | 826.63 ± 15.39a | 901.86 ± 6.80a | 606.37 ± 3.87b | 658.34 ± 12.16b | 362.13 ± 11.35c | 293.58 ± 1.75d | 685.33 ± 16.15b | 130.37± 2.72e | 885.01± 5.16a |

| D | 1489.30 ± 12.76a | 1549.49 ± 19.63a | 751.89 ± 0.61c | 979.64 ± 11.49d | 69.38 ± 7.54b | 10.96 ± 5.24b | 489.49 ± 3.71e | 91.24± 4.00b | 1503.80± 5.65a | |

| E | 528.52 ± 58.92c | 659.76 ± 18.69a | 704.17 ± 7.80a | 354.97 ± 20.60d | 269.48 ± 11.24b | 98.05 ± 5.82e | 256.62 ± 14.76b | 260.75± 4.35b | 699.19± 20.46a | |

| F | 2933.52 ± 60.22d | 3128.91 ± 44.48a | 2073.32 ± 9.08b | 2041.83 ± 38.04b | 717.00 ± 10.86e | 426.78 ± 3.69c | 1475.83 ± 30.85f | 469.90± 5.38c | 3073.28± 30.07a | |

| FCR | C | 1.26 ± 0.03a | 1.59 ± 0.01c | 1.22 ± 0.01a | 1.23 ± 0.02a | 0.86 ± 0.02d | 0.70 ± 0.00e | 1.48 ± 0.03b | 0.57± 0.01f | 1.44± 0.01b |

| D | 1.34 ± 0.01b | 1.57 ± 0.02c | 1.45 ± 0.00d | 1.28 ± 0.01e | 0.96 ± 0.00f | 0.70 ± 0.00a | 1.63 ± 0.01g | 0.68± 0.00a | 1.70± 0.00h | |

| E | 1.59 ± 0.00a | 1.63 ± 0.05a | 1.61 ± 0.01a | 1.45 ± 0.05c | 0.99 ± 0.00b | 0.99 ± 0.01b | 1.76 ± 0.04d | 0.82± 0.00e | 1.66± 0.04f | |

| F | 1.40 ± 0.01a | 1.60 ± 0.02b | 1.43 ± 0.00a | 1.32 ± 0.02c | 0.94 ± 0.01d | 0.80 ± 0.00e | 1.62 ± 0.03b | 0.69± 0.00f | 1.60± 0.01b | |

| EPEF | - | 395.08 ± 6.06a | 325.63 ± 0.31b | 279.44 ± 0.10b | 319.79 ± 1.17c | 251.58 ± 2.55d | 226.90 ± 0.49e | 166.16 ± 0.65f | 311.31 ± 2.57g | 319.16 ± 0.93g |

| EBI | - | 469.10 ± 7.84a | 384.08 ± 0.45c | 318.32 ± 0.34b | 367.29 ± 1.66c | 179.40 ± 2.15d | 189.81 ± 0.84d | 175.45 ± 0.98d | 277.59 ± 3.45e | 375.68 ± 1.39c |

| Group | SR (%) | RWG rate (%) | Oocyst number x104 | Oocyst value | Lesion score | Lesion value | ACI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NINF-NT | 100 | 100 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| INF-NT | 90 | 74.818 | 10.639 | 100 | 2.85± 0.57 | 28.50± 5.71 | - |

| TH-AQ1 | 100 | 230.532 | 1.917 | 18.016 | 1.43± 0.52 | 14.33± 5.23 | 298.183 |

| TH-AQ2 | 100 | 287.951 | 3.722 | 34.987 | 1.08± 0.22 | 10.83± 2.24 | 342.130 |

| RO-AQ1 | 100 | 75.607 | 8.500 | 79.896 | 1.17± 0.73 | 11.67± 7.32 | 83.711 |

| RO-AQ2 | 100 | 170.184 | 5.111 | 48.042 | 2.18± 0.33 | 21.83± 3.31 | 200.309 |

| ME-AQ1 | 70 | 84.243 | 5.917 | 55.614 | 2.50± 0.00 | 25.00± 0.00 | 73.630 |

| ME-AQ2 | 90 | 58.960 | 7.139 | 67.102 | 2.65± 0.56 | 26.50± 5.61 | 55.358 |

| TOTRA | 100 | 211.166 | 3.194 | 30.026 | 1.75± 0.62 | 17.50± 6.21 | 263.639 |

| Group | Mean composite lesion score ± SD * | Segment(s) most affected † | Concise histological description | Parasite stages seen | Interpretation vs. mixed Eimeria challenge ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NINF-NT | 0.00 ± 0.00 | – | Long slender villi, orderly crypts, intact epithelium, minimal lamina propria cells. | None | True physiological baseline. Confirms sampling artefacts are negligible. |

| INF-NT | 2.85 ± 0.57 | Duo > Jej ≈ Ile > Cae | Massive villus loss, dilated crypts packed with necrotic debris, extensive coagulative necrosis, dense heterophil infiltrate. | Numerous schizonts, gamonts, and oocysts | Unrestricted replication of all challenge species: E. praecox (duodenum), E. maxima (jejunum), E. necatrix (mid-gut), E. tenella (caeca) etc. |

| TOTRA | 1.75 ± 0.62 | Jej > Duo | Slight villus blunting, crypts intact, continuous epithelium, sparse mononuclear infiltrate; parasites absent. | None | Near-complete protection, matching the broad anti-Eimeria spectrum of toltrazuril. |

| TH-AQ1 | 1.43 ± 0.52 | Duodenum | Largely intact architecture, mild lamina-propria infiltrate, very occasional vacuolated parasite residua. | Very rare | Best-performing plant extract, strong suppression of E. praecox/maxima and reasonable control of E. tenella. |

| TH-AQ2 | 1.08 ± 0.22 | Duo ≈ Jej | Blunted villi, moderate crypt hyperplasia, light mixed infiltrate, parasites extremely sparse. | Sporadic | Higher dose offers no meaningful histological gain over TH-AQ1—efficacy already near plateau. |

| RO-AQ1 | 1.17 ± 0.73 | Duo ≈ Jej | Marked villus loss, crypt destruction, focal necrosis, dense inflammation; many gamonts/oocysts. | Abundant gamonts and oocysts | Incomplete protection: only moderate impact on E. praecox/maxima; caeca relatively spared. |

| RO-AQ2 | 2.18 ± 0.33 | Duo > Jej ≈ Ile | Patchy villus absence, crypt hyperplasia, focal fibrin, parasites fewer than RO-AQ1. | Scattered gamonts | A higher dose lowers the parasite load somewhat, yet leaves moderate lesions, resulting in intermediate efficacy. |

| ME-AQ1 | 2.50 ± 0.00 | All segments (even) | Carpets of necrotic exfoliated enterocytes, partial crypt preservation, diffuse inflammation, and scattered parasites. | Moderate gamonts/oocysts | Variable, only partial protection, limited activity versus E. maxima and E. brunetti. |

| ME-AQ2 | 2.65 ± 0.56 | All, esp. Jej/Ile | Villus obliteration, “honey-comb” hyperplastic crypts, fibrino-purulent exudate, oocysts still numerous. | Numerous macrogamonts/oocysts | A higher dose fails to improve outcome; lesions approach INF-NT severity, explaining the poor ACI. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).