1. Introduction

Turkey meat (

Meleagris gallopavo) is a product of constant and stable demand in North America, Europe, and some countries in Latin America. After chicken meat, it is the second-largest contributor to poultry meat production worldwide [

1]. However, consumption per capita varies among countries. It has been accepted that higher consumption of turkey meat is directly linked to socioeconomic status. Thus, consumption is higher in some countries with high economic situations than in developing ones. However, on some holidays and festivities, its consumption increases sharply in many Western countries. Nevertheless, rising living standards, the rapid pace of urbanization, the growing popularity of Western diets in Asia, and increased attention to lower fat intake have led to a significant increase in the production and consumption of turkey meat worldwide in recent years. For example, Mexico produced 157 thousand tons, and Germany produced 117 thousand tons in 2018. However, these countries were the largest importers of turkey meat that year. The Mexican national poultry census grew 2.1% in one year (2021-2022), closing at 541 million animals as follows: 163.3 million laying hens, 310 million broiler chickens per cycle, and 459 thousand turkeys per cycle [

2]

The incidence of coccidiosis in turkeys is high. However, lesions caused by these protozoa are less severe than in broiler chickens and laying hens. The majority of coccidia infections show subclinical features. An enteric process caused by lesions induced by the parasite’s replication in the gastrointestinal epithelium becomes evident in more clinically apparent cases. Coccidiosis reduces feed intake, diminishes digestibility, and causes poor absorption of nutrients. Rapid weight loss, shedding, and ruffled feathers become evident, affecting weight gain and productive variables [

3]. Severe diarrhea or at least wet stools with mucus may be present, and increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral diseases follows. Turkeys of all ages are susceptible to coccidial infection, but they develop a reasonable immune response when the outbreak occurs from 6-8 weeks of age onwards. Later, morbidity rises in weeks 8-9, but mortality is usually not very high [

4,

5].

Eimeria species linked to clinical cases do not present cross-immunity between them. Only four of the seven coccidia species in turkeys are considered pathogenic, i.e.,

E. adenoides,

E. dispersa,

E. gallopavonis y,

E.

meleagrimitis. As in broiler chickens, diagnosis is established by localizing the gastrointestinal tract's affected section based on the oocyst morphology, the incubation period, its pathogenicity, details of each coccidial life cycle, and absence of cross-species immunity, and host specificity [

6,

7,

8].

Coccidiosis in turkeys is usually controlled by ionophore drugs such as lasalocid and monensin. Diclazuril has been used during outbreaks. Ionophore derivatives are administered for up to 12 weeks, and resistance to these treatments has already been reported [

9,

10,

11]. An alternative that is being pondered in the world for turkey production is botanical products, mainly essential oils, colorants, and phenolic compounds [

12]. The mechanism of action of many herbal remedies has yet to be fully characterized. However, evaluations in various species, including pigs, dogs, chickens, and humans, have found that some of these substances may exert effects through one or more mechanisms, such as 1) disruption of the pathogens' cell membranes; 2) physicochemical modification of the cell surface and thus affecting the virulence of pathogens, 3) stimulating the immune system, specifically through the activation of lymphocytes, macrophages, and large granular - natural killer lymphocytes; 4) protecting the intestinal mucosa from pathogen colonization, and 5) promoting competitive exclusion in the intestinal lumen [

13,

14]. Among the products potentially beneficial for their anticoccidial activity are curcumin, which has been shown to induce apoptosis by means of the presence of precipitates on the sporozoite surface that affect its morphology, viability, and adhesion ability [

15], and black garlic and its derivatives as they inhibit oocysts sporulation. They have been linked to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and the anticoccidial potential of garlic is linked to its immunostimulatory activity. Garlic and its derivatives inhibit the sporulation of oocysts in vitro. The supplementation of garlic in coccidiosis-infected broilers improves weight gain and feed efficiency. It reduces fecal oocysts output, lesion score, and clinical signs postinfection [

16]. However, there are no data on its use in the production of turkeys. Another potentially helpful botanic product is sodium alginate [

17,

18,

19]. This material has broad applications in veterinary medicine, including as a pharmaceutical vehicle to increase the stability of active principles and as a polymer to allow sustained release. In poultry farming, alginates have been evaluated as probiotics and a pharmaceutical vehicle for antibacterial drugs because their gel-forming properties can provide a modified release pattern of active ingredients [

20,

21,

22]. It is compatible with the poultry's digestive tract, and it may be helpful for the control of coccidiosis in turkeys. Thus, this trial aimed to test the anticoccidial efficacy in turkeys of pharmaceutical preparations made with minced black garlic, powdered curcumin, or both coated with sodium alginate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical approval

The study design and animal handling complied with the Mexican regulations for using experimental animals as established by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the Mexican standards established in NOM-062-ZOO-1999 and CICUA-FMVZ-UNAM.

2.2. Groups and dosage

A total of 150 twelve-day-old male turkeys untreated with an antiparasitic drug were randomly distributed into 15 pens (10 turkeys per pen). Each group had two replicates. They were kept under the same temperature, ventilation, feeders, diet, drinkers, and health care activities for 42 days. Turkeys were kept outdoors in an "all-in, all-out" system with an indoor area of 4 poults/m². A feed with a built-in scale was used to weigh the amount of feed given to the poults each day, and food waste weight was recorded at the end of the day. Their body weight was recorded before they were fed with a commercial brand (Pavo Ganador®, Api-Aba, Mexico, without coccidiostats) for the starters phase (from hatching to 8 weeks old) (22% crude protein [C.P.] and 3015 kcal/k, M.E.); the growing phase (9 to 18 weeks old) (20% CP, 3180 kcal/k, M.E.) and the finishing phase (18 weeks old up to market weight) (19% CP and 3100 kcal/k, M.E.). The rations were based on yellow corn (Zea mays), 45% soybean paste, and sunflower oil, supplemented with amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Feed did not contain anticoccidial drugs. The treatments included the herbal remedies in alginate beads as dressing in an amount of 4% of their feed intake, as follows: control group (CTRL) received no treatment; group GAR: fed the same diet as CTRL group plus dried alginate beads containing minced black garlic (4%); group CUR incorporating powder Curcuma in dried alginate beads (4%); group, G.C., containing both minced garlic plus powder Curcuma (8%), also entrapped in dried alginate beads and group, G.A., containing only alginate. Treatments were incorporated into daily feed intake as dressing for six weeks. Turkeys were monitored to ensure that all animals were eating. Feeders that were appropriate for the number of turkeys in the pen were used to prevent larger or dominant poults from monopolizing the amount of feed. Daily evaluation of product and feed waste was carried out.

2.3. Preparation of the dried alginate beads

Fifty g of sodium alginate (Silverquim®, Mexico) are added to one liter of water until wholly suspended. Then, 100 g of powder

Curcuma (Entera®, Entera Pharma, Mexico) or 100 g of freeze-dried black garlic powder (RV-Organic®, RV-Organic, Mexico) are added and stirred for a further 60 min. The suspension is poured drop by drop employing a multiple injection system into a stirred solution of 0.2% calcium chloride (SILVERQUIM®, Mexico), where alginate beads are formed instantly. When the batch is finally processed, the beads are rinsed with bidistilled water and left to dry at room temperature for three days. Loss of active ingredients was determined with, U.V. visible spectroscopy and calculated as < 10 % for

Curcuma and < 8% for black garlic [

23,

24]. Hence, an approximate 85% inclusion rate of each herb in each dried alginate bead was established.

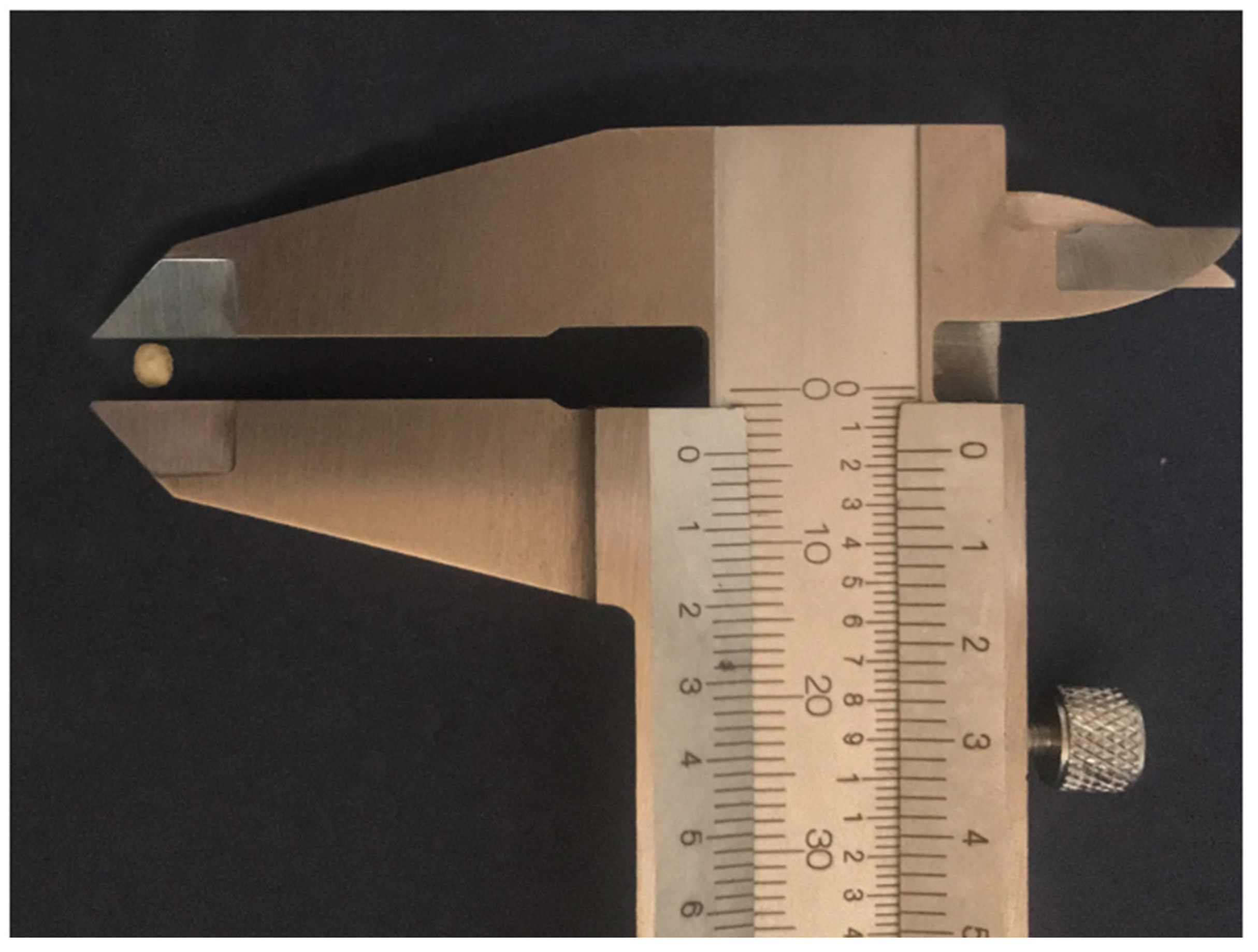

Figure 1 shows the alginate beads in their wet phase, and

Figure 2 shows the alginate beads once dried, as they were fed to the animals.

2.4. Parasitological analysis

Eimeria oocysts per gram of feces (OPG) were counted by McMaster’s coproparasitological analysis [

25]. Feces were collected from the floor on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. Approximately ten fresh fecal droppings were collected from each pen and combined into one sample per pen. The pens were sampled in a zig-zag fashion to randomize the sample collection, and samples that were dried or contaminated with litter or food were not collected. Species were determined by incubating isolated oocysts in Petri dishes in 5 mL of potassium dichromate for 48 h at 25–29 °C and 80% relative humidity. At the end of the incubation period, the oocysts were identified according to the essential taxonomic keys [

26]. One hundred oocysts were counted to determine the percentage of each species found.

2.5. Performance parameters

The following parameters were recorded weekly per pen: weight gain (W.G.), feed intake (F.I.), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) (FCR = feed consumed/weight gain).

2.6. Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, the ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to find differences between pens and treatments, and the Kruskal-Wallis and Tukey's tests were used to find differences between production performance using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 for Mac, and GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA (

www.graphpad.com).

3. Results

No statistical differences were found between repetitions of the same treatment (P< 0.5).

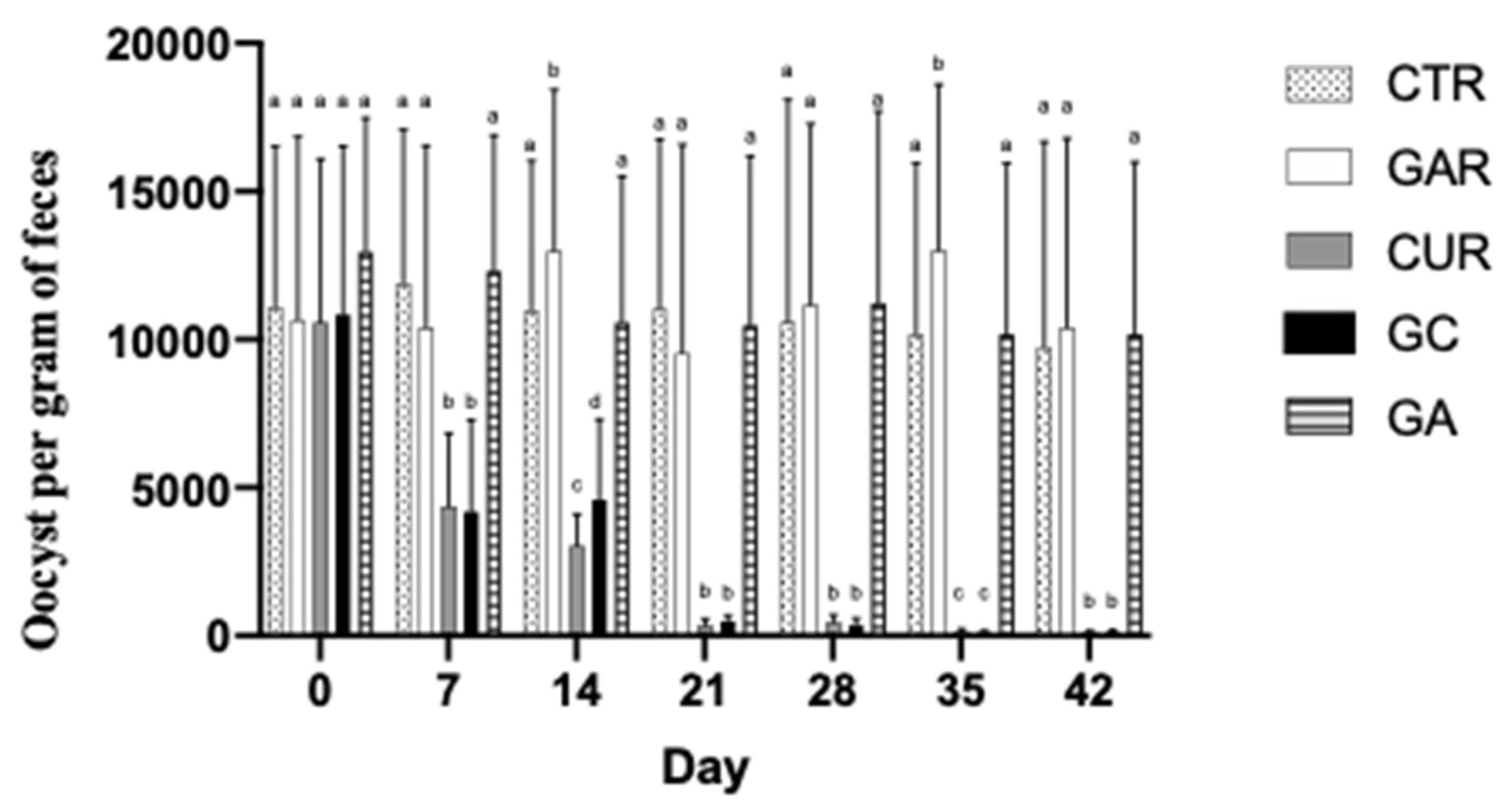

Figure 3 shows the decrease in oocysts in the groups, results recorded for the turkeys in group CUR and, G.C. significantly reduced OPG compared to the untreated controls turkeys (CTRL and, G.A.) and those that were fed only GAR. There is no statistical difference in groups CTRL and, G.A. the alginate alone did not present an anticoccidial effect. It behaved statistically like the control group. End-of-day alginate beads and feed waste in the CUR and, G.C. groups were confirmed to be almost null throughout the evaluation. In contrast, alginate bead wastage in the GAR group averaged 18% daily. This was taken as an indication that, even though the alginate masks the taste, turkeys rejected the taste of garlic.

Table 1 shows that the ingestion of Curcuma longa significantly reduces the shedding of the most pathogenic species of Eimeria, i.e., E. adenoids, E. gallopavonis, and, E. meleagrimitis.

No statistical differences were found between repetitions of the same treatment (P< 0.5) in productive parameters; the arithmetic means of the productive parameters recorded are presented in

Table 2. Weight gains and feed intake were similar between CTRL, GA, GAR, and CUR treatments; consequently, feed conversion ratios were also statistically indistinguishable among treatments, except for the, G.C. and, G.A. groups, as turkeys in this group gained more weight in a statistically significant manner (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Coccidiosis in turkeys (

Meleagris gallopavo) is a prevalent veterinary disease with a significant economic impact [

6,

11]. It has been pointed out that the severity of this disease is increasing in parallel to the intensification of turkey production worldwide [

5,

7]. With the emergence of pathogen resistance and the new international trends to reduce the use of drugs in livestock production and complying with consumers' demands, a reduction in the use of anticoccidial drugs has been attempted in some countries. Herbal remedies and their phytogenic bioactive principles are viable alternatives for controlling coccidiosis [

6]. However, rather than simply adding herbal remedies to the poultry feed, it is crucial to develop preparations whose pharmaceutical design allows optimal contact with the active ingredients available in herbal remedies and can endure longer shelf-life (Sumano et al., 2003). In recent years, advances in pharmaceutical technology have led to the development of economically viable drug/herbal preparations for poultry. For instance, oral drug formulations can be designed to modify a drug release and increase its bioavailability [

27] or extend an active principle's contact time with a given pathogen [

28]. Recent studies have found that chickens have a better-developed flavor ability than suspected. Therefore this feature will significantly impact their feeding behavior more than previously appreciated [

29,

30]. There are only a few studies in this regard on turkeys. However, in this trial, it became evident that the group dosed with garlic failed to eat all their food, suggesting a rejection of garlic, even as alginate-coated beads. In this context, alginate was included as a pharmaceutical excipient in the preparation assessed in this trial. Alginates are valuable vehicles for many pharmaceutical applications and possess antimicrobial and antiviral protection properties. They are biodegradable, biocompatible, and lack toxicity. Besides, alginates are reasonably inexpensive and can be used as a gelling vehicle to thicken, stabilize, and emulsify various drug preparations. Multiple studies have shown that it can coat or encapsulate active principles and natural substances for better drug delivery after oral administration [

31,

32,

33,

34].

Consequently, in the case of the herbal constituents utilized in this trial, it is safe to assume that the alginate employed acted as stabilizing agent, modifying the release of the active principles of the minced black garlic and turmeric powder. This pharmaceutical maneuver presumably enhanced the anticoccidial action of the active principles derived from the formula [

17]. It is also crucial to consider some manufacturing procedures if this herbal formulation is planned to be used in large production centers. The active principles of garlic are rapidly degraded by oxidation, and this makes it necessary to add other elements to the described combination, i.e., antioxidants (for example, butylated hydroxytoluene [BHT]), as well as other stabilizing elements and dispersant chemicals. Furthermore, stability studies of the proposed combination and quality control studies are needed to guarantee the clinical repeatability of this formula in a large-scale production scenario. Nevertheless, it is safe to stand out that the pharmaceutical association of garlic and powder

Curcuma with alginate and not only the herbal resources alone were responsible for the anticoccidial effects noted in this trial.

Our results comply well with knowledge accumulated for garlic and its secondary metabolites (propyl thiosulfinate [PTS] and propyl thiosulfinate oxide [PTSO]), whose intestinal immunity ability during experimental infections by

Eimeria acervulina has been demonstrated [

35,

36]. Also, in-vitro assays showed that both PTSO (67%) and PTS (33%) possess a dose-dependent killing ability against invasive,

E.

acervulina sporozoites. Garlic toxicity is negligible, and in dose-toxicity studies, it was found that 500 mg/kg body weight may induce a certain degree of liver damage. In contrast, lower doses have a well-defined hepatoprotective action. Hence, our findings agree with previous work that evaluated feed consumption by adding Curcuma for up to 42 days in broilers from the Ross line, which gained significantly more weight during the productive cycle [

37]. Another work reported that adding 0.02%, 0.03%, and 0.04% of powder Curcuma in feed caused significant weight gain increments, whether measured in the initiation or the growth period [

38]. Thus, apart from the anticoccidial efficacy observed with the herbal formulation, the added

Curcuma powder exhibited a nutritional role that became apparent through the productive parameters obtained. Curcuma powder is rich in minerals, vitamins, protein, and carbohydrates and can reduce oxidative stress in intestinal cells, limiting cell damage [

13,

39]. The turmeric plant is used in traditional medicine in humans. It is considered a phytoremedy for various diseases, i.e., respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatobiliary, and irritable bowel disease. Curcuma powder is non-mutagenic, non-carcinogenic, non-hepatotoxic, and does not possess known adverse effects [

40]. However, researchers' main difficulty in taking advantage of all these properties is determining and enhancing the intestinal absorption and contact time of its active principles, modulating its biotransformation, and controlling its rapid gastrointestinal clearance. However, it is crucial to consider that even natural compounds have been shown to generate resistance in the

Eimeria genus, and further studies should be carried out to characterize this problem for the presented herbal formulation. However, the herbal constituents utilized in this trial have been described by the absence of coccidial resistance development [

41,

42]. Further studies may also reveal if this herbal formula has immunomodulatory action and improves gut integrity, as suggested elsewhere [

43].

Finally, as pharmaceutical optimization of herbal remedies may maintain its efficacy for a more extended period [

44], it is necessary to carry out further studies to establish the optimal pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic ratios of the garlic,

Curcuma, alginate preparation here tested, i.e., minced garlic has been linked to a time-dependent ratio for optimal anticoccidial effect [

23].

5. Conclusions

This study shows that turkey poults that received minced garlic plus Curcuma powder prepared as dried alginate beads at a rate of 4% of their daily diet and for 42 days and administered as a feed-dressing showed a significant decrease in the excretion of oocysts per gram of feces, revealing a potentially useful anticoccidial activity. Treatment of turkey poults during this period did not reduce feed intake, weight gain, or feed conversion rate. Conversely, a clear trend to improve these parameters when using these plants included in dried alginate beads were identified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G. and H.S.; methodology, Y.A., L.G., H.S.; software, L.G. and H.S., validation, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; formal analysis, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; investigation, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; resources, H.S.; data curation, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing—review and editing, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; visualization, L.G., H.S. and Y.A.; supervision, L.G.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PAPIIT IT200322, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study design and animal handling complied with the Mexican regulations for using experimental animals as established by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the Mexican standards established in NOM-062-ZOO-1999 and CICUA-FMVZ-UNAM.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Gateway to poultry production and products. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/poultry-production-products/en/ (accessed on July 2023).

- UNA. Unión Nacional de Avicultores. Compendio de indicadores económicos del sector avícola. 2021. Available online: https://una.org.mx/indicadores-economicos/ (accessed on July 2023).

- Taylor, M.A.; Coop, R.L.; Wall, R. Veterinary parasitology; Willey-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fatoba, A.J.; Adeleke, M.A. Diagnosis and control of chicken coccidiosis: a recent update. J Parasit Dis. 2018, 42, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D. Coccidiosis in the turkey. Avian Pathol. 2008, 37, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrba, V.; Pakandl, M. Coccidia of turkey: from isolation, characterization and comparison to molecular phylogeny and molecular diagnostics. International journal for parasitology. 2014, 44, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoba, A.J.; Adeleke, M.A. Diagnosis and control of chicken coccidiosis: a recent update. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2018, 42, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D.; Rathinam, T. Focused review: the role of drug combinations for the control of coccidiosis in commercially reared chickens. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance. 2022, 18, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D. Milestones in avian coccidiosis research: a review. Poult Sci. 2014, 93, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlala, T.; Okpeku, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Understanding the interactions between Eimeria infection and gut microbiota, towards the control of chicken coccidiosis: a review. Parasite. 2021, 28, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shall, N.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Albaqami, N.M.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.E.; Swelum, A.A.; et al. Phytochemical control of poultry coccidiosis: a review. Poult Sci. 2022, 101, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemaiswarya, S.; Kruthiventi, A.K.; Doble, M. Synergism between natural products and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Phytomedicine. 2008, 15, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Hong, Y.H.; Kim, G.B.; Lee, S.H.; Lillehoj, E.P.; et al. Dietary Capsicum and Curcuma longa oleoresins increase intestinal microbiome and necrotic enteritis in three commercial broiler breeds. Res Vet Sci. 2015, 102, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Teng, P.Y.; Souza Dos Santos, T.; Gould, R.L.; Craig, S.W.; Lorraine Fuller, A.; et al. The effects of different doses of curcumin compound on growth performance, antioxidant status, and gut health of broiler chickens challenged with Eimeria species. Poult Sci. 2020, 99, 5936–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Biswas, K.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Banerjee, R.K. Turmeric and curcumin: Biological actions and medicinal applications. Current science. 2004, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Adjei-Mensah, B.; Atuahene, C.C. Avian coccidiosis and anticoccidial potential of garlic (Allium sativum, L.) in broiler production: a review. Journal of Applied Poultry Research. Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 2022, 100314. [Google Scholar]

- Shabkhiz, M.A.; Pirouzifard, M.K.; Pirsa, S.; Mahdavinia, G.R. Alginate hydrogel beads containing Thymus daenensis essential oils/Glycyrrhizic acid loaded in β-cyclodextrin. Investigation of structural, antioxidant/antimicrobial properties and release assessment. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2021, 344, 117738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppakundilograt, S.; Piboon, P.; Graisuwan, W.; Nuisin, R.; Kiatkamjornwong, S. Encapsulated eucalyptus oil in ionically cross-linked alginate microcapsules and its controlled release. Carbohydr Polym. 2015, 131, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamian, S.; Nourani, M.; Bakhshi, N. Formation and characterization of calcium alginate hydrogel beads filled with cumin seeds essential oil. Food Chemistry. 2021, 338, 128143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, J.; Yu, H.; Guo, Q.; Defelice, C.; Hernandez, M.; et al. Alginate-whey protein dry powder optimized for target delivery of essential oils to the intestine of chickens. Poult Sci. 2014, 93, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voo W-P, Ravindra, P. ; Tey B-T, Chan E-S. Comparison of alginate and pectin-based beads for production of poultry probiotic cells. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering. 2011, 111, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Garcia, J.; Chavez-Carbajal, A.; Segundo-Arizmendi, N.; Baron-Pichardo, M.G.; Mendoza-Elvira, S.E.; Hernandez-Baltazar, E.; et al. Efficacy of Salmonella bacteriophage S1 delivered and released by alginate beads in a chicken model of infection. Viruses. 2021, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshtinat, K.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A.; Hamidi, Z. Encapsulation of Iranian Garlic Oil with β-cyclodextrin: Optimization and its Characterization. 2017.

- Hazra, K.; Kumar, R.; Sarkar, B.K.; Chowdary, Y.A.; Devgan, M.; Ramaiah, M. UV-visible spectrophotometric estimation of curcumin in nanoformulation. International journal of pharmacognosy. 2015, 2, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa CJA, Jasso, V.C.; Liébano, H.E.; Martínez, L.P.; Rodríguez VRI, Zárate RJJ. Examen Coproparasitoscópico. In: Técnicas para el diagnóstico de parásitos con importancia en salud pública y veterinaria. AMPAVE-CONASA, editor. Mexico, D.F.: AMPAVE-CONASA; 2015. 517 p.

- Clarkson, M.J. The life history and pathogenicity of Eimeria meleagrimitis Tyzzer 1929, in the turkey poult. Parasitology. 1959, 49, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, O.L.; Sumano, L.H.; Zamora, Q.M. Administration of enrofloxacin and capsaicin to chickens to achieve higher maximal serum concentrations. Veterinary record. 2002, 150, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, B.; De Backer, P.; Remon, J.P. Drug administration to poultry. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002, 54, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, E.; Baldwin, M.W.; Klasing, K.C. The avian taste system: Potential implications in poultry nutrition. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2013, 180, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu H-X, Rajapaksha, P. ; Wang, Z.; Kramer, N.E.; Marshall, B.J. An update on the sense of taste in chickens: A better-developed system than previously appreciated. Journal of nutrition & food sciences. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Severino, P.; da Silva, C.F.; Andrade, L.N.; de Lima Oliveira, D.; Campos, J.; Souto, E.B. Alginate Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery and Targeting. Curr Pharm Des. 2019, 25, 1312–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From Food Industry to Biomedical Applications and Management of Metabolic Disorders. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; Tapia, G.; Gutierrez, E.; Sumano, H. Evaluation of a Tasteless Enrofloxacin Pharmaceutical Preparation for Cats. Naive Pooled-Sample Approach to Study Its Pharmacokinetics. Animals (Basel). 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, L.; Lechuga, T.; Marcos, X.; García-Guzmán, P.; Gutierrez, C.; Sumano, H. Comparative bioavailability of enrofloxacin in dogs when concealed in noncommercial morsels, either as a tablet or as enrofloxacin–alginate dried beads. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2021, 44, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderlich, F.; Al-Quraishy, S.; Steinbrenner, H.; Sies, H.; Dkhil, M.A. Towards identifying novel anti-Eimeria agents: trace elements, vitamins, and plant-based natural products. Parasitol Res. 2014, 113, 3547–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidiropoulou, E.; Skoufos, I.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Giannenas, I.; Bonos, E.; Aguiar-Martins, K.; et al. Anticoccidial Study of Oregano and Garlic Essential Oils and Effects on Growth Performance, Fecal Oocyst Output, and Intestinal Microbiota. Front Vet Sci. 2020, 7, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa Izurieta, M.F. Evaluación de diferentes niveles de Cúrcuma longa (Cúrcuma), como pigmetante natural en dietas a base de sorgo, para la implementación de pollos broiler. 2016.

- Llerena Lima, G.S. Efecto de tres niveles de harina de palillo (Curcuma longa, L.) en la pigmentación y comportamiento productivo de pollos Broiler en Pucallpa. 2016.

- Al-Rubaei, Z.M.; Mohammad, T.U.; Ali, L.K. Effects of local curcumin on oxidative stress and total antioxidant capacity in vivo study. Pak J Biol Sci. 2014, 17, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, S.; Chempakam, B. Toxicity prediction of compounds from turmeric (Curcuma longa L). Food Chem Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, S.; Tanveer, S.; Nawchoo, I.A.; Malik, T.A. Anticoccidial activity of Artemisia vestita (Anthemideae, Asteraceae) - a traditional herb growing in the Western Himalayas, Kashmir, India. Microb Pathog. 2017, 104, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, S.A.; Tersteeg-Zijderveld, M.H.; Jongerius-Gortemaker, B.G.; Vervelde, L.; Vernooij, J.C. In vitro inhibition of Eimeria tenella invasion of epithelial cells by phytochemicals. Vet Parasitol. 2013, 191, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.M.; Da Silva, A.S.; Biazus, A.H.; Reis, J.H.; Boiago, M.M.; Topazio, J.P.; et al. Feed addition of curcumin to laying hens showed anticoccidial effect and improved egg quality and animal health. Res Vet Sci. 2018, 118, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.K.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Lillehoj, E.P.; Bravo, D. Improved resistance to Eimeria acervulina infection in chickens due to dietary supplementation with garlic metabolites. Br J Nutr. 2013, 109, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).