Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

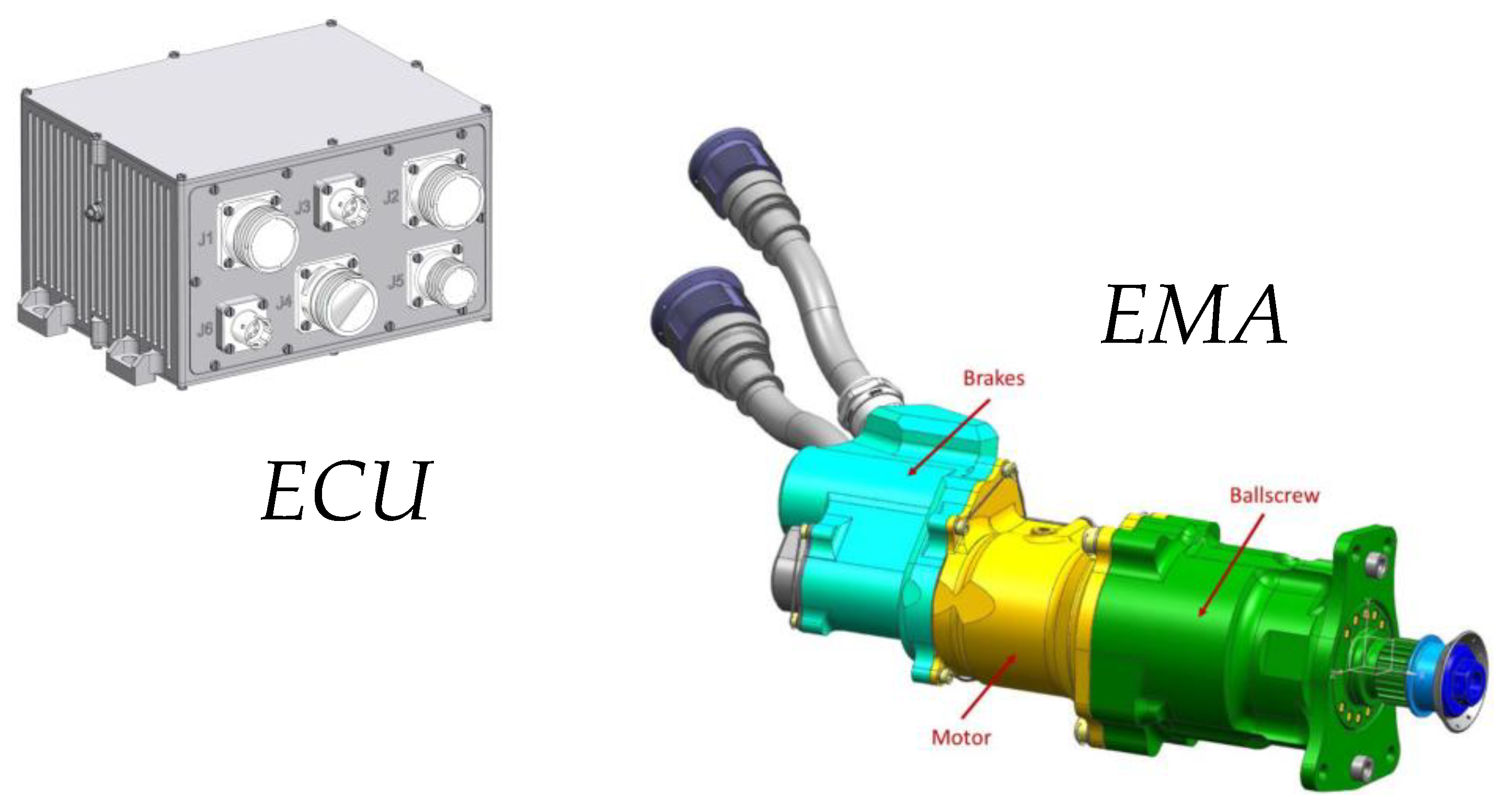

2.1. System Description

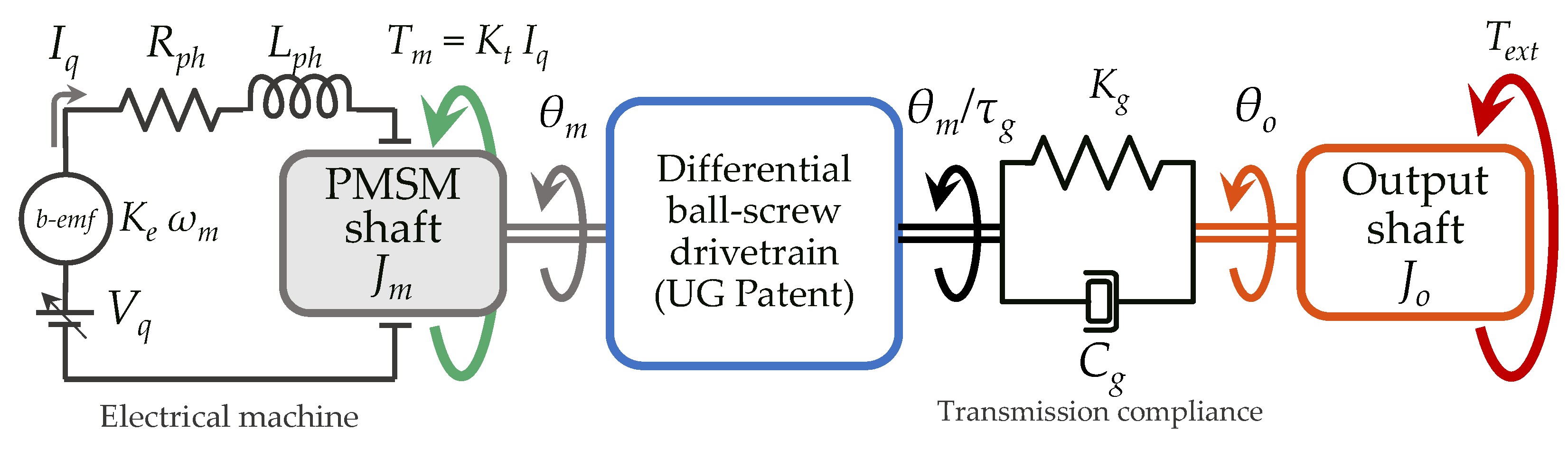

2.2. System Dynamics Modelling

- Three-phase Surface mounted Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (S-PMSM) current dynamics in the direct-quadrature (d-q) reference frame;

- UMBRAGROUP patented mechanical transmission based on a high transmission ratio differential ball-screw mechanism, including its internal stiffness and resonance;

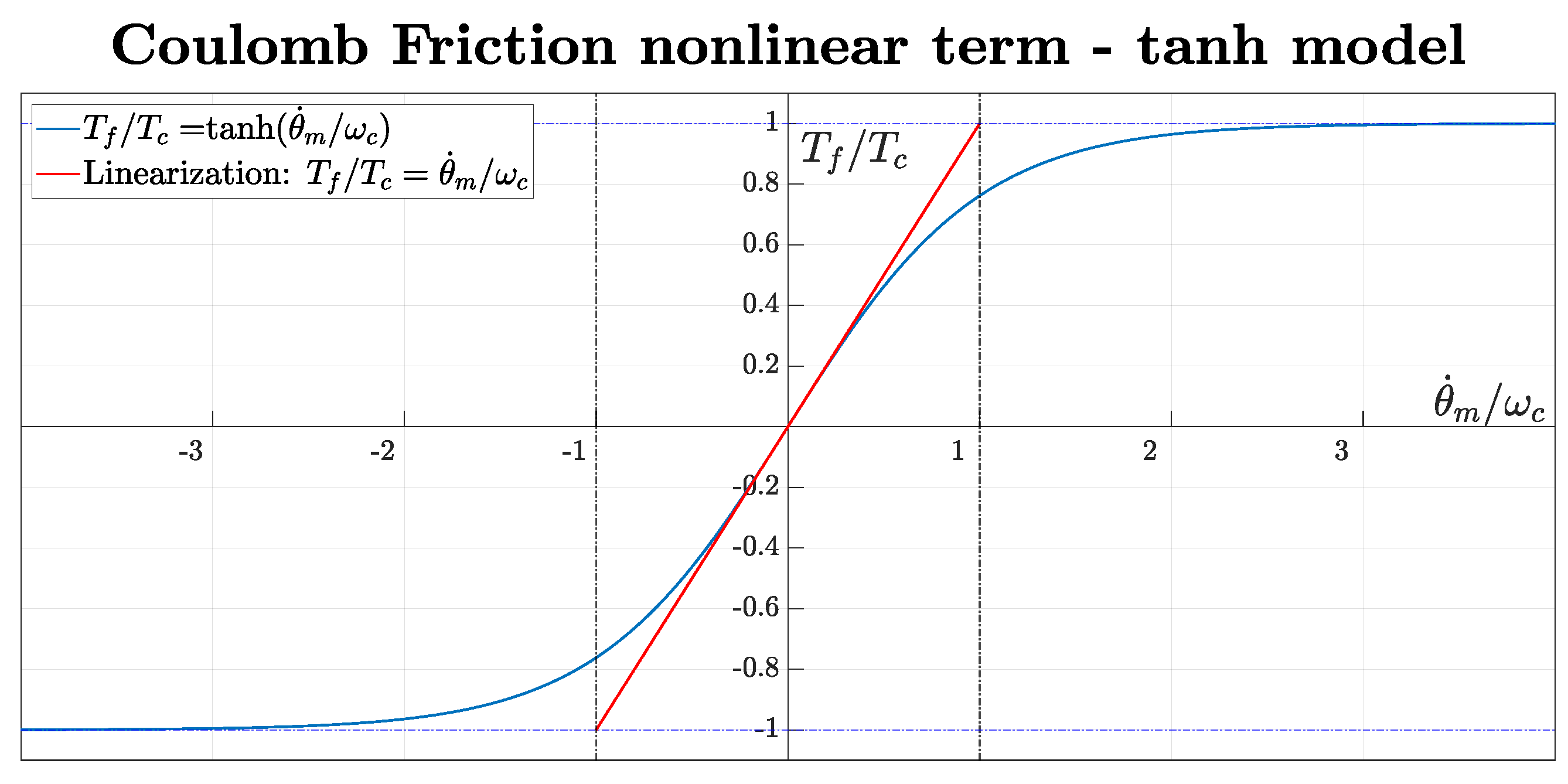

- Coulomb and viscous friction;

- Rotational dynamics of the output shaft, including the reference aircraft surface inertia and external load effects.

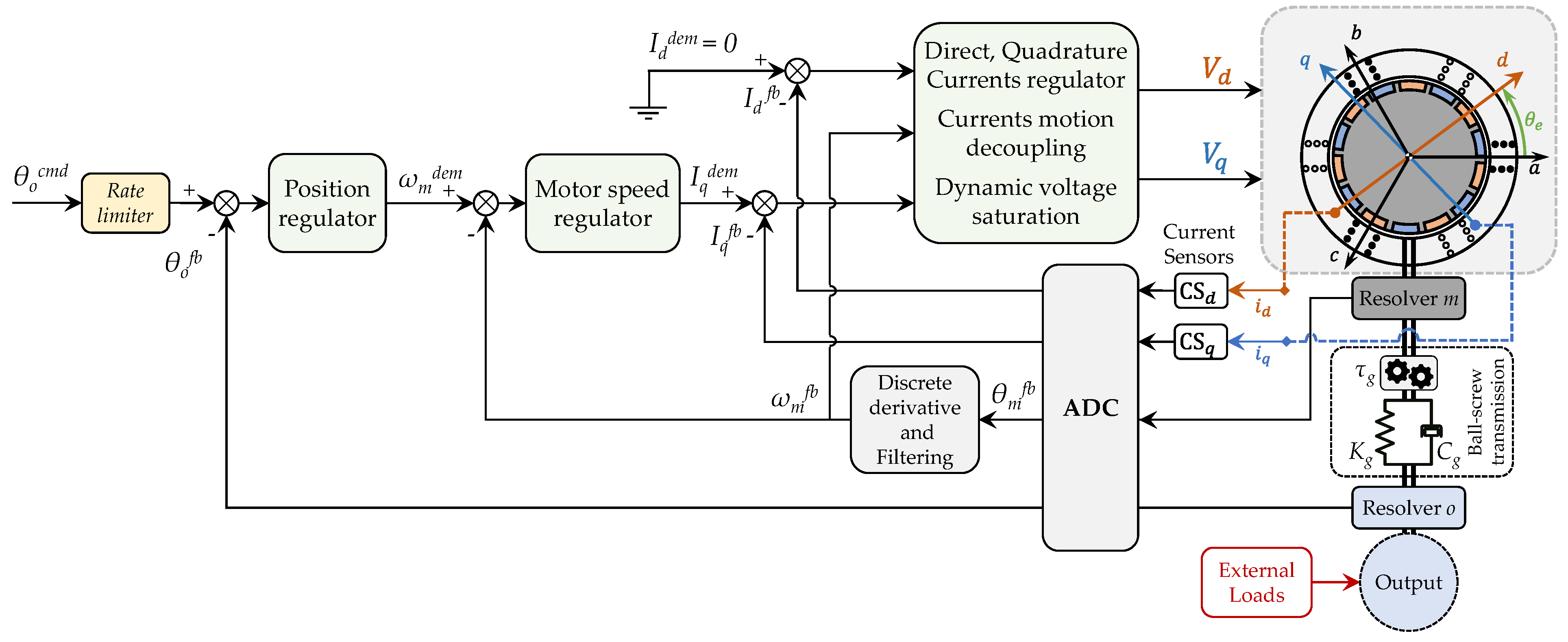

- Three nested control loops acting on motor direct and quadrature currents, motor speed, and output shaft position;

- Control nonlinearities (saturations, rate-limiter on position command);

- Sensors dynamics, latencies and resolution;

- Resolver sensors for motor and output shaft position feedback;

- Motor speed reconstruction from angular position;

- Hall-effect sensors for current measurement;

- Digital signal processing performed at 10 kHz.

2.2.1. Electro-Mechanical Section

2.2.2. Digital Electronics Section

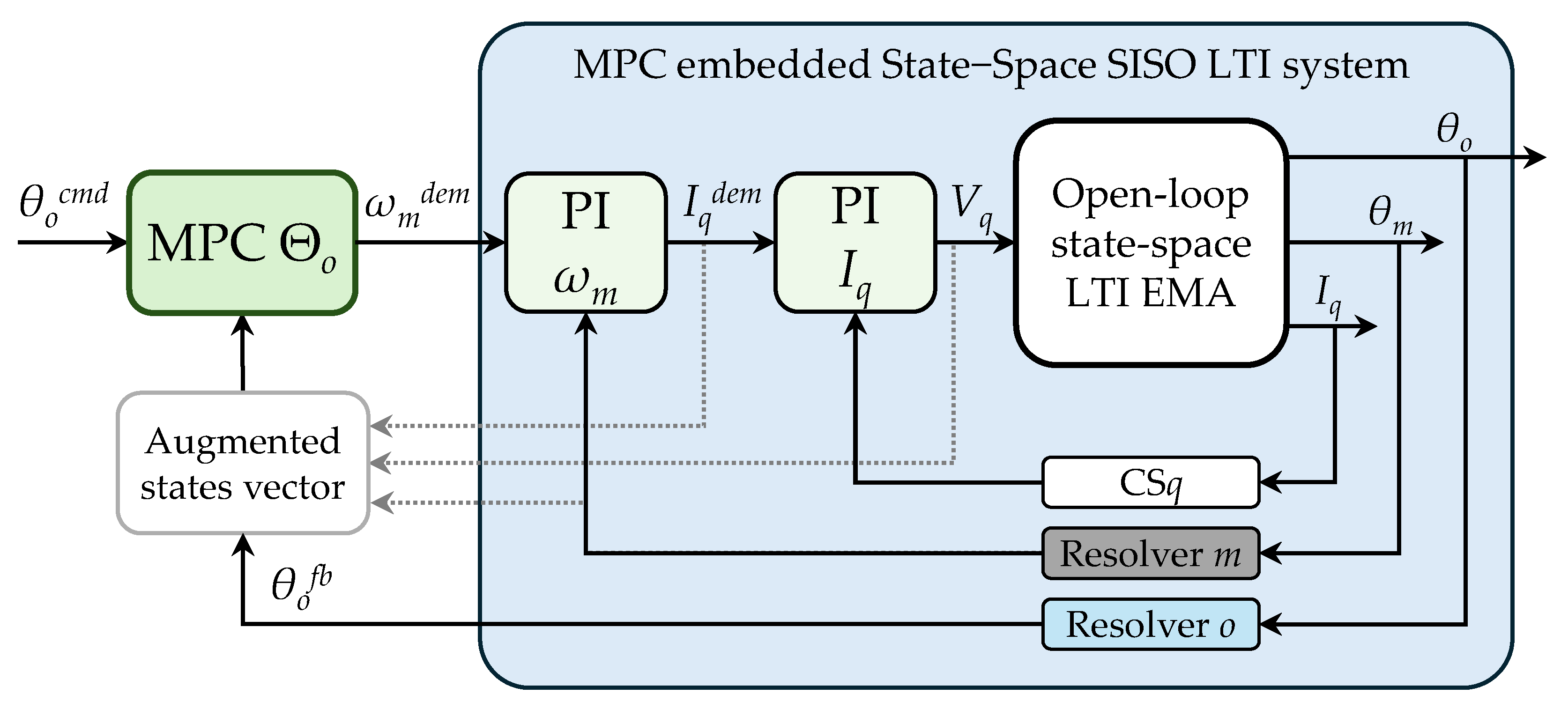

- Control laws: the EMA output position command is first rate-limited at the maximum output shaft speed ωomax, then compared to the resolver feedback. The position error is fed to the position regulator which generates a motor speed request. This is compared to the value derived from the motor resolver position feedback and fed to the motor speed regulator which outputs a quadrature current demand. The direct current instead has a fixed null reference to achieve Maximum Torque Per Ampere (MTPA) control for S-PMSM [36], assuming Ld = Lq = Lph. On the baseline design, position, speed and current regulators have a Proportional-Integral structure with saturation and anti-windup scheme. In the MPC-based control, only the position regulator is replaced with an MPC, maintaining the other control laws unchanged. Additionally, current regulator integrates the decoupling technique. By reformulating eq. (1), the relationships in (4) can be established, linking the voltages Vdreg, Vqreg, calculated by the current regulator, to their post-decoupling counterparts Vddec, Vqdec. This approach ensures that the current dynamics along the d-q axes remain unaffected by motor speed variations, leading to independent behaviour of the d and q currents. The equation (4) assumes that discrepancies between actual and measured values of currents and speed remain minimal, alongside with low variations in electrical constants, thus ensuring an effective decoupling. Finally, the voltages are dynamically saturated according to the constraint (5).

- Sensors processing: the rotor and output shaft positions are measured through resolver angular sensors, while d-q currents are acquired with Hall-effect current sensors. On the real EMA, each motor phase current is measured, then d-q currents are calculated in the digital control section via Clarke-Park transformation (6).

2.3. Conventional control Laws Optimization

- the proportional gain: KP;

- the zero of the integrator: zI.

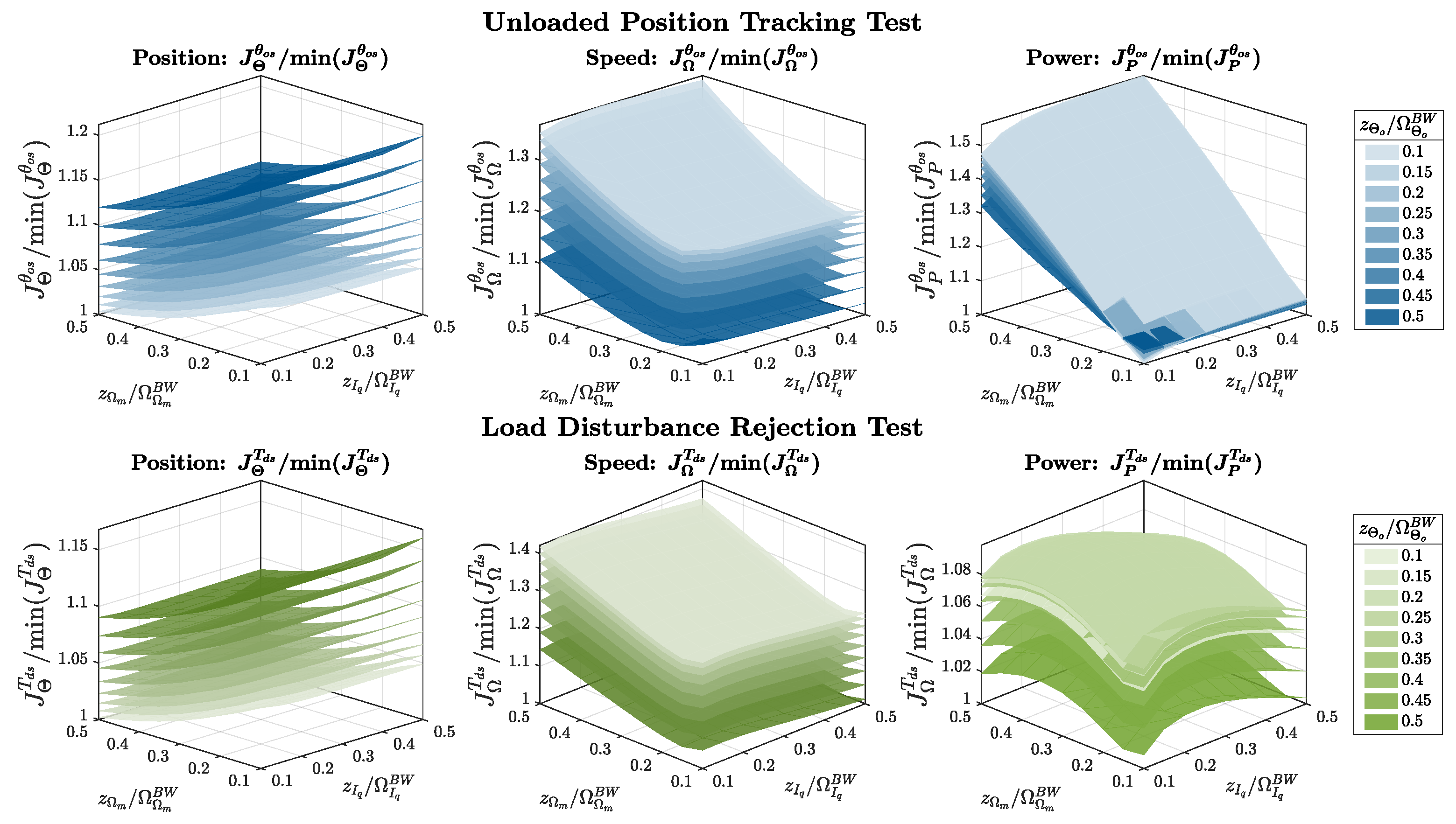

- Position tracking test: the commanded output position is a step of θos = 1 deg, with no external load applied. The cost function measures the squared tracking error between the output position and the reference command (9). Similarly, is linked to the deviation of the motor speed from the regulator reference (10). The cost function quantifies the normalized electric power absorption: since it includes the open-loop input voltage Vq, this metric reflects the required effort to achieve the desired tracking performance.

- Load disturbance rejection test: the position command is set to the equilibrium condition (i.e. θocmd = 0 deg) while an external torque step of Text = 1 Nm is applied. The three corresponding cost functions are analogously defined (12)-(14).

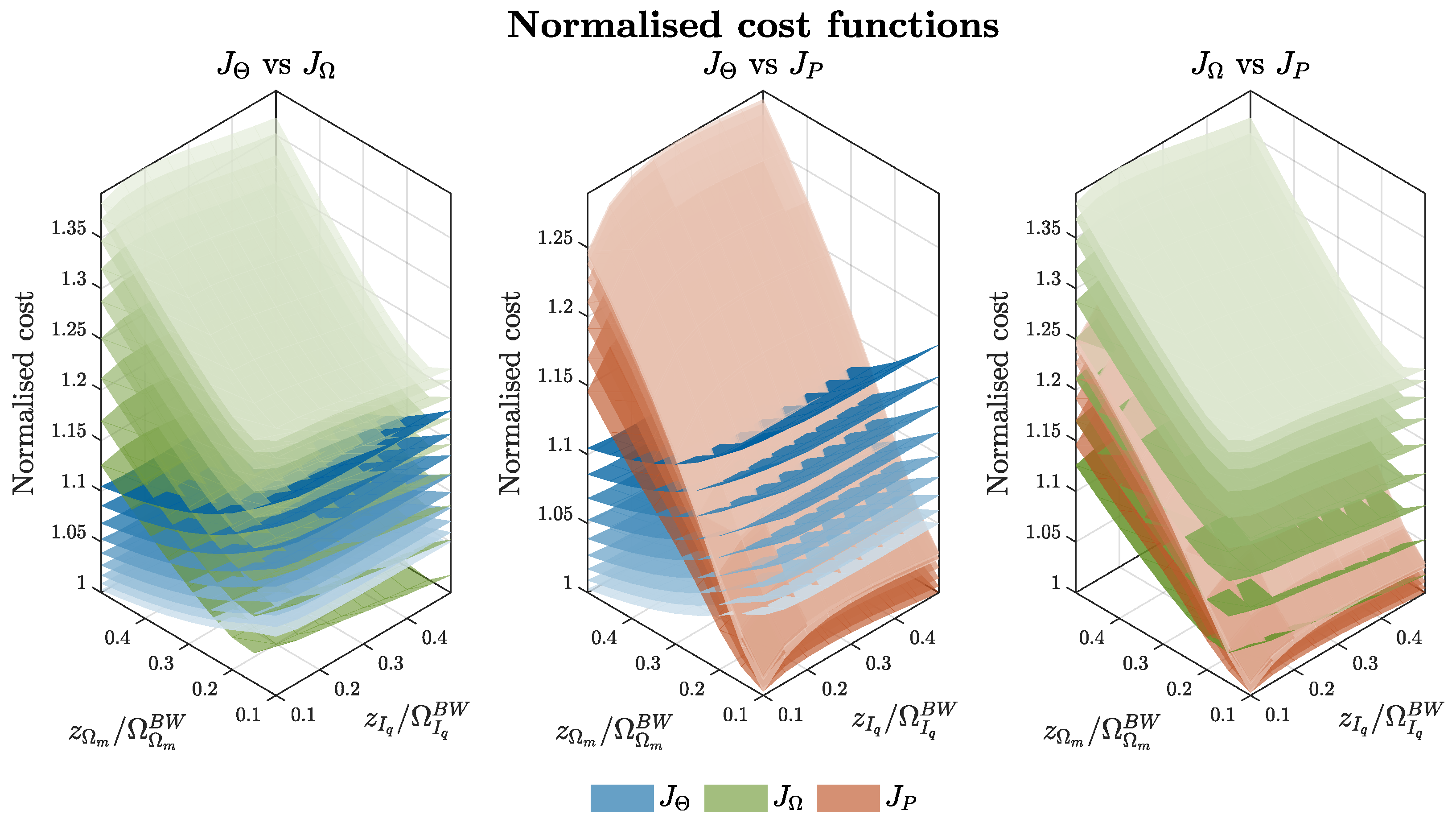

- Zeros placement variation: a common variation vector for zero placement is defined and applied equally across all control loops. The zeros location is varied as fractions of the respective closed-loop design bandwidths, within the range [0.1–0.5], to ensure a minimal impact of the zero on the bandwidth itself. Adopting a Monte Carlo-like optimization algorithm, a large number of zeros placement combinations are generated for the three nested control loops.

- Feed-forward design and stability verification: for each configuration, the feed-forward transfer function is constructed by cascading with the open-loop transfer function from its output to the EMA system output in the corresponding control loop. The proportional gain is then automatically calculated by enforcing that the cut-off frequency of the feed-forward transfer function matches the predefined closed-loop bandwidth. Stability margins are checked, and if they meet the required specifications, the state-space LTI closed-loop model of the EMA system is constructed.

- Time-domain simulation and cost functions evaluation: the position closed-loop EMA is simulated under position tracking and disturbance rejection tests; consequently, the values of the six cost functions are evaluated for each zeros configuration.

- Normalization of cost functions: for each cost function, the minimum value across all combinations is identified to allow its normalization. This ensures consistent comparison across metrics with different physical units and scales.

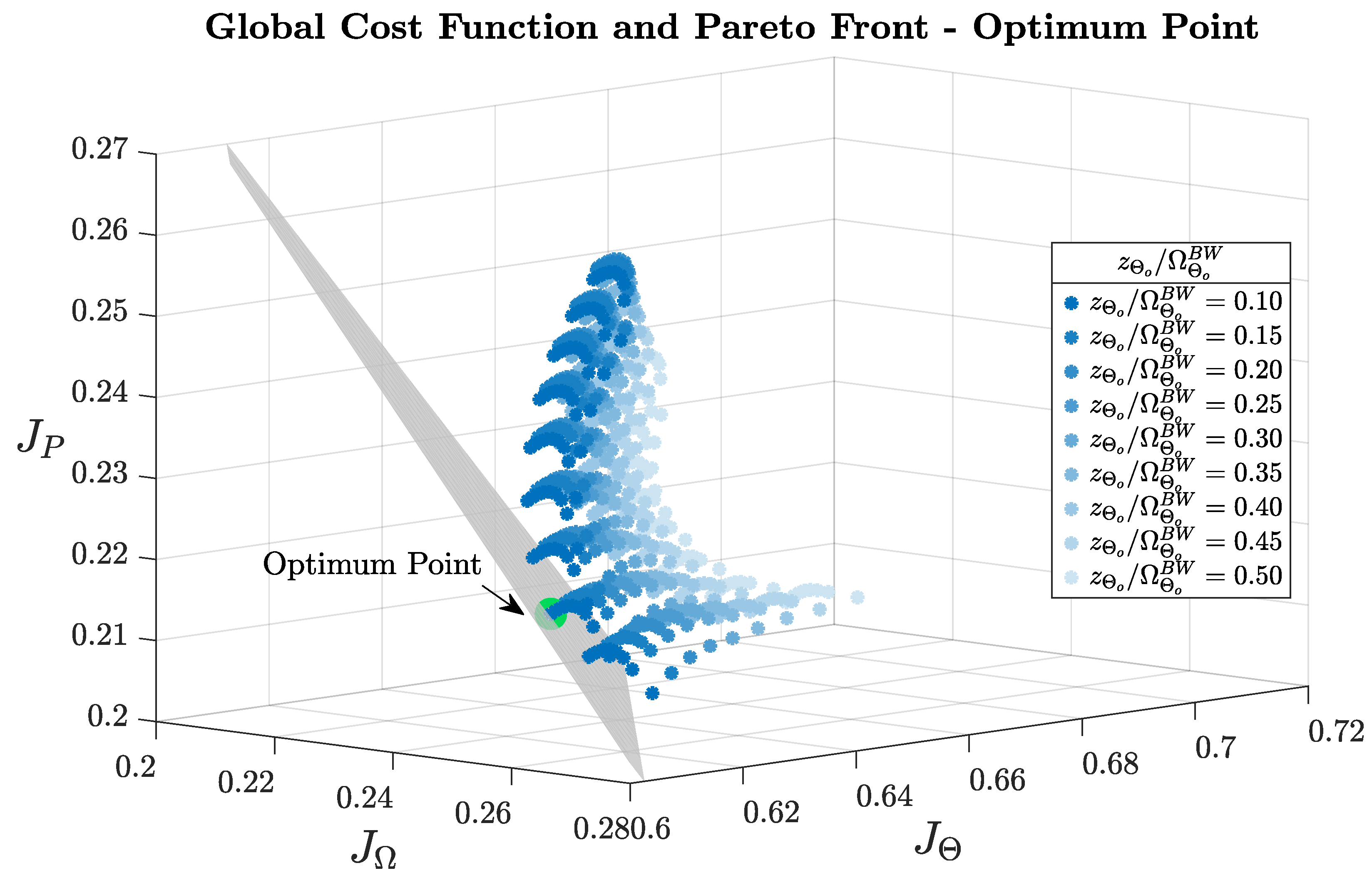

- Weight definition for multi-objectives cost function: given the focus on primary flight control applications, the optimization strategy prioritizes position tracking performance over secondary objectives. Accordingly, the weights associated with motor speed tracking and power consumption are fixed to small values (19); conversely, the weights associated with position tracking cost functions are allowed to vary within a discrete set of values (20) to be treated as tuneable parameters within the optimization process.

- 6.

- Computation of the global cost function: for each valid combination of zero placements and cost function weights, the global cost function Jw is evaluated according to (15).

- 7.

- Optimal design identification: the optimal controllers configuration is identified as the one that minimizes the global cost function, ensuring the best trade-off among the considered performance metrics.

2.4. Model Predictive Controller development

- Information on the current and previous states of the system;

- A mathematical model of the plant to predict its future evolution;

- An optimization criterion (typically a quadratic cost function).

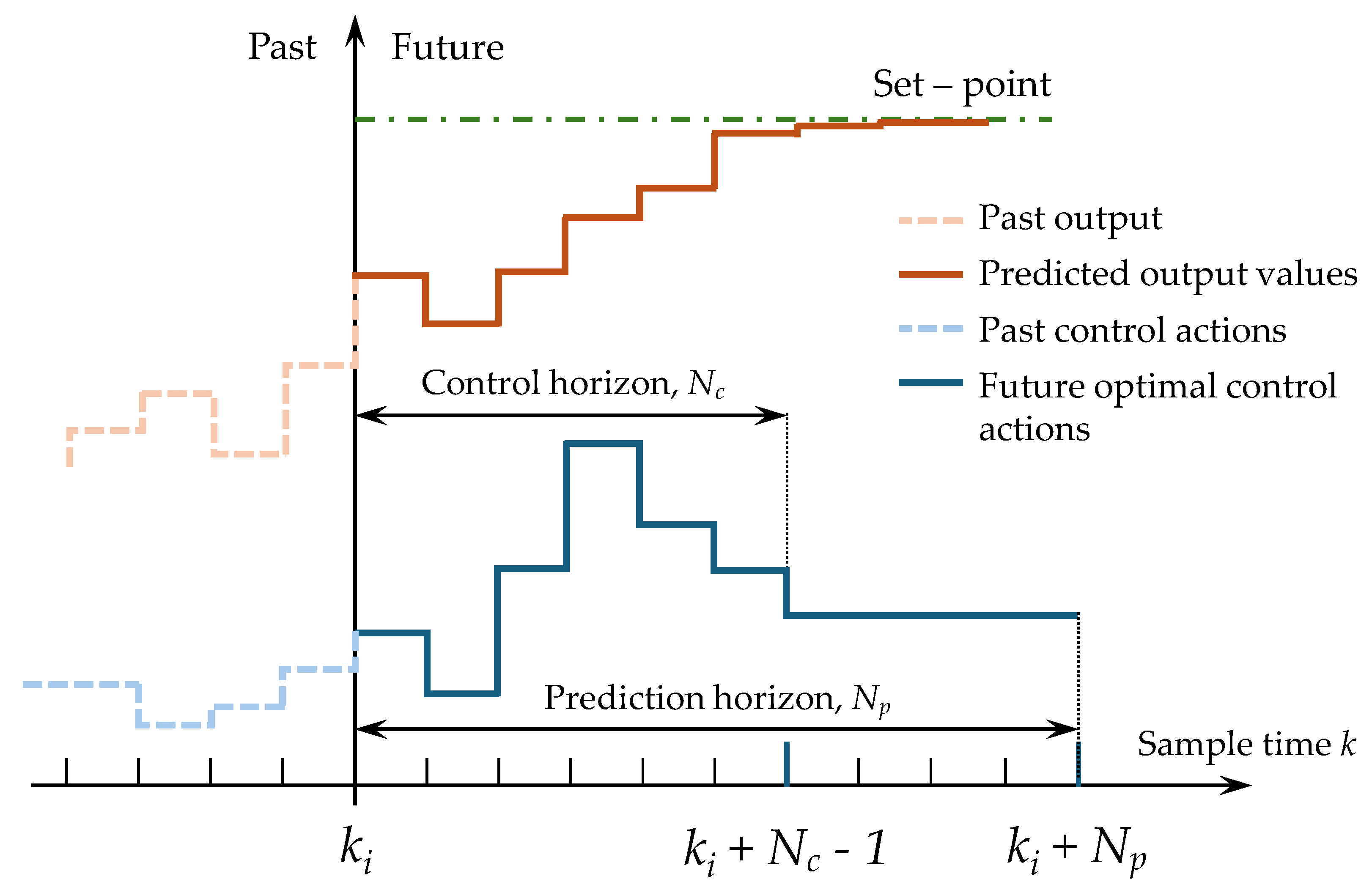

- Prediction Horizon (Np) defines the finite time span (in terms of discrete time steps k) over which the future system output is predicted, using the plant model and current state information. A longer prediction horizon allows the controller to capture a more comprehensive understanding of the system evolution, though increasing the complexity of the algorithm.

- Control Horizon (Nc) denotes the finite time window over which the future control inputs u(k) are optimized, i.e. for k=ki,…,ki+Nc-1, where ki is the initial time. Nc is constrained by computational costs and the need to balance predictive accuracy with real-time implementation. Thus, Nc is usually smaller than Np , and for k>ki+Nc-1 the control input is assumed to remain constant. The selection of an appropriate control horizon is crucial as it directly influences the controller ability to anticipate and regulate the system behaviour effectively.

- Receding Horizon control: a dynamic optimization framework enables the controller to adapt its control strategy in real-time by recalculating control inputs at each time step, based on the most recent state information, to enhance robustness against model inaccuracies and external perturbations and to maintain system stability. Mathematically, at time k, the MPC computes an optimal sequence of control actions over the full control horizon, however, only the first input u(k) is applied to the plant. At the next time step, the system state is updated, and a new optimization is performed.

2.4.1. Discrete-time LTI MPC formulation

2.4.2. Prediction Within One Optimization Window

2.4.3. Optimization Criterion

2.4.4. Model Predictive Position Controller Design

- a short control horizon (Nc = 5) proved sufficient, as longer values did not significantly improve performance;

- a long prediction horizon (Np = 500) was necessary to properly capture the system dynamics and generate effective control actions;

- Given the incremental nature of the MPC law, the input-weighting factor should remain small (rw = 10-3) to prevent over-smooth inputs, thereby preserving actuator responsiveness and ensuring adequate control authority.

2.5. Performance Comparison and Robustness Analysis

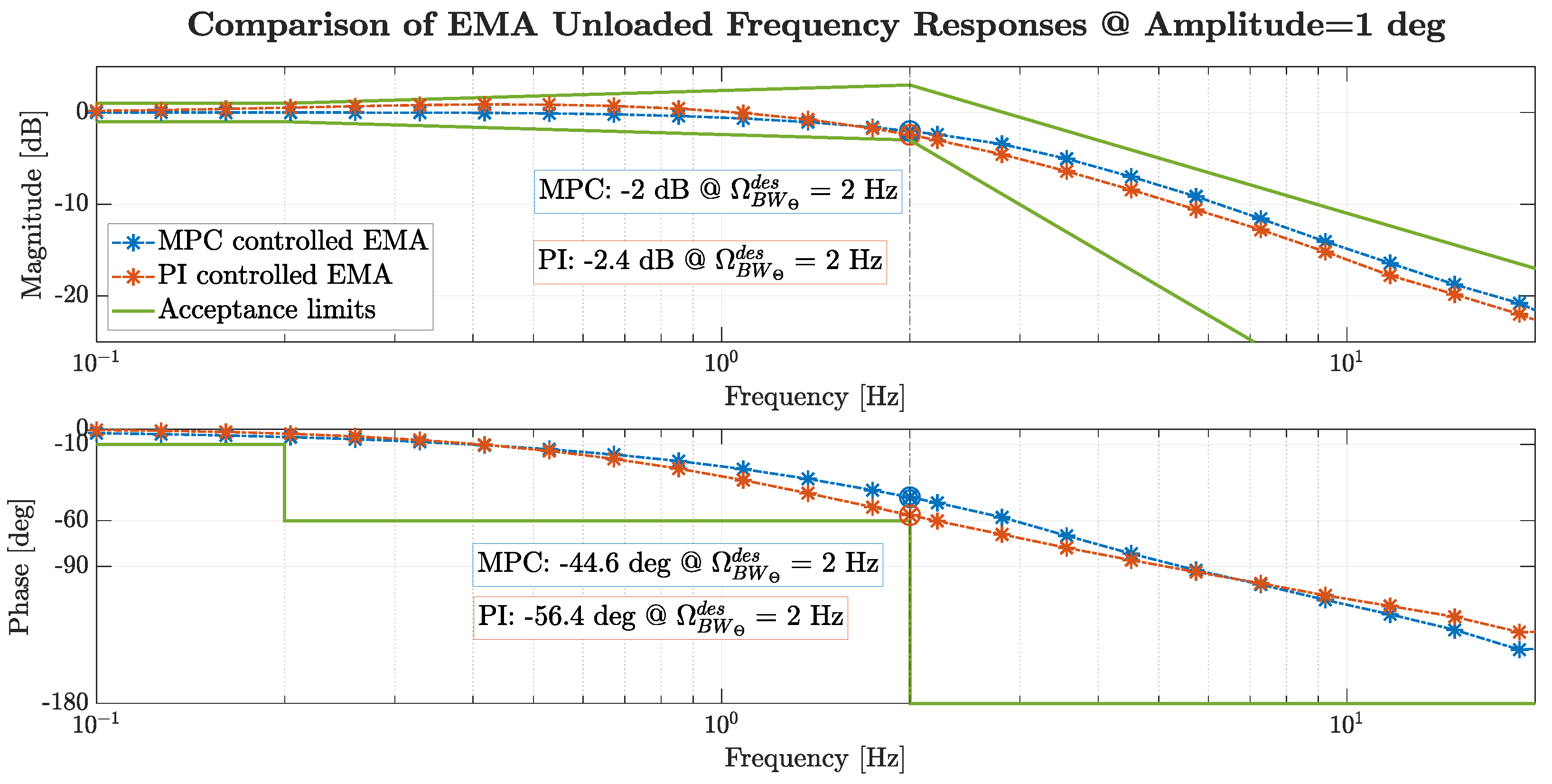

- The EMA unloaded position tracking response is assessed in the frequency domain with harmonic commands of 1 deg amplitude.

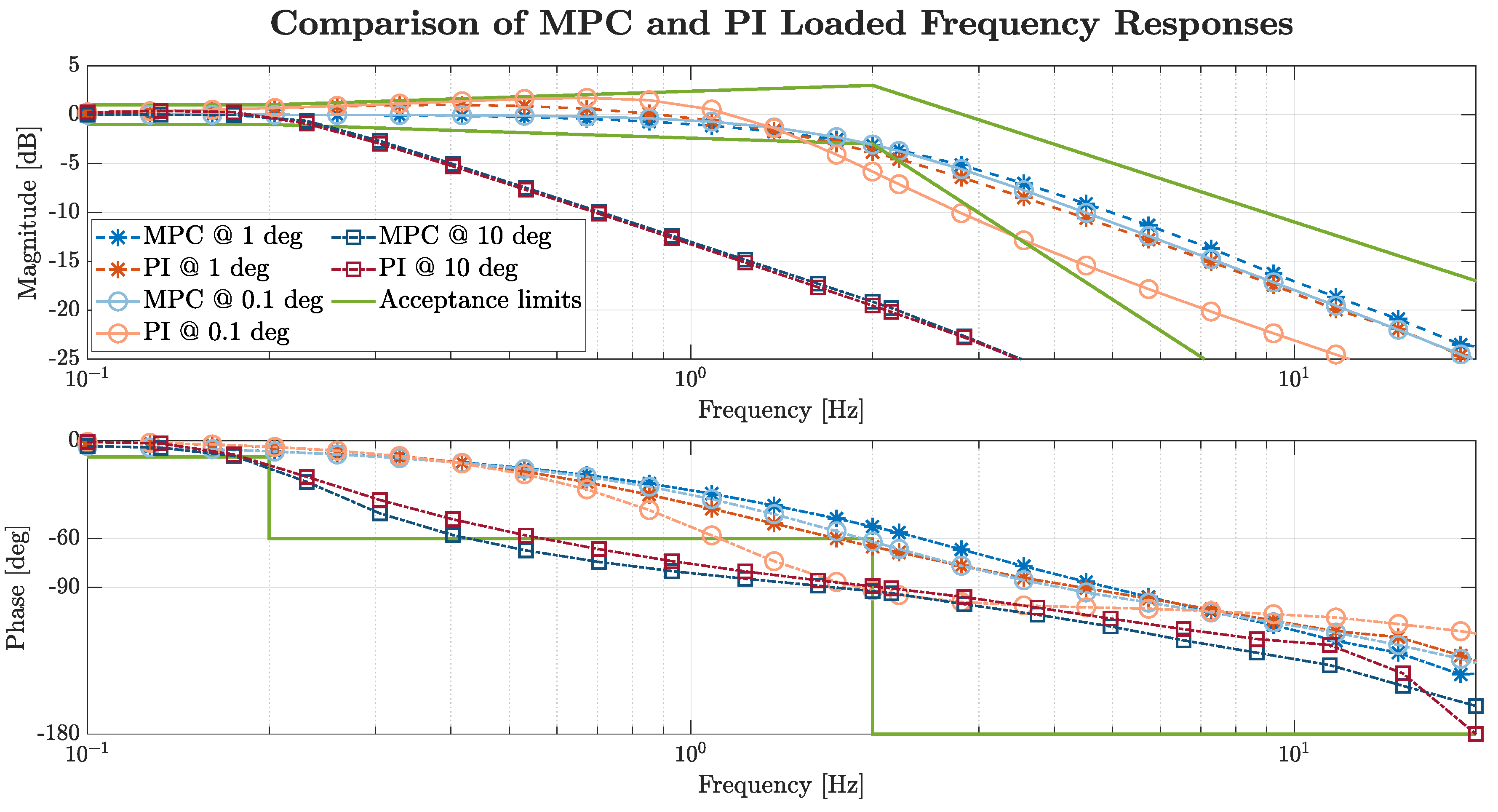

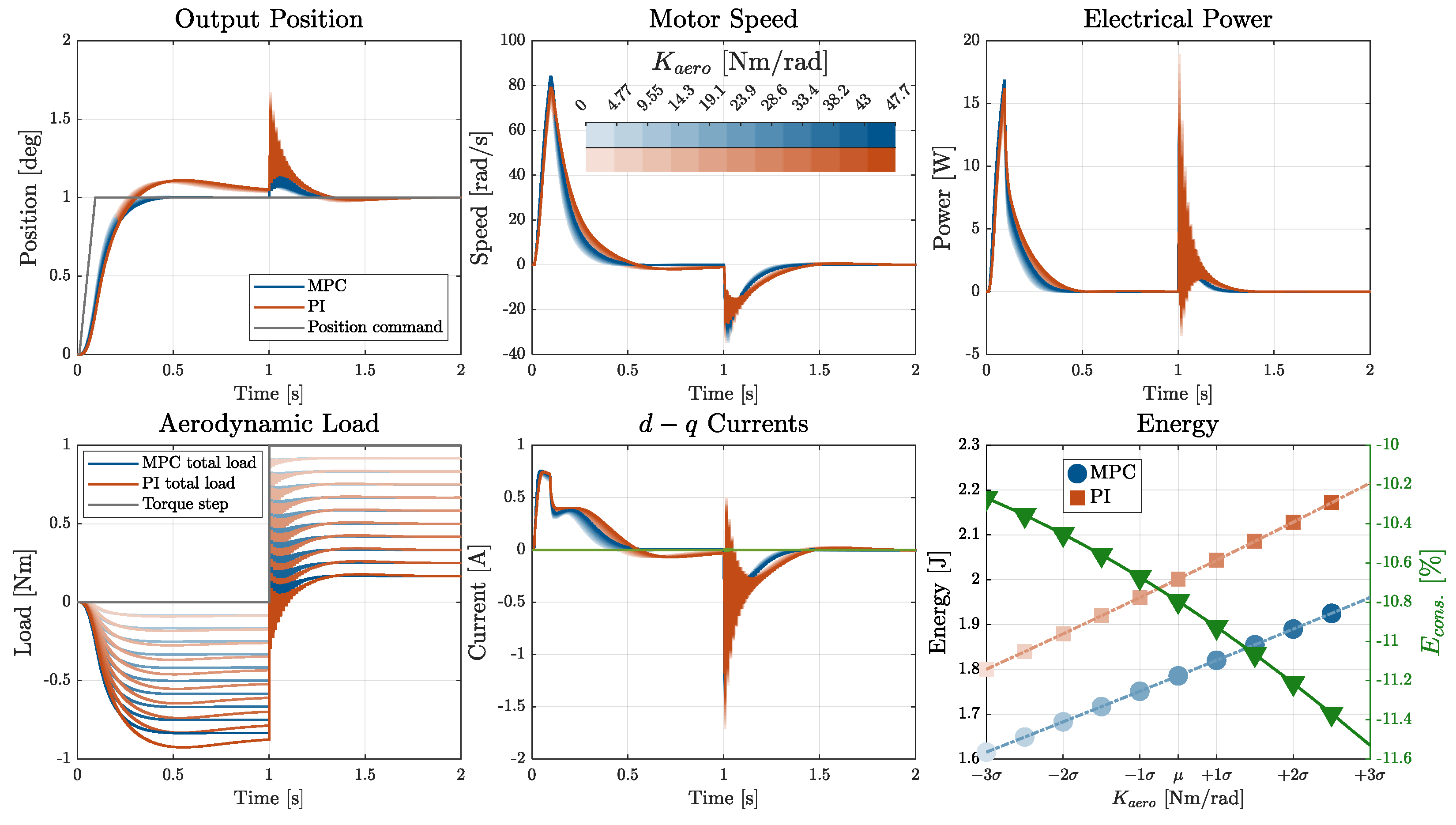

- In the loaded position tracking tests, aerodynamic actions on the control surface are modelled as an equivalent torsional spring with constant stiffness Kaero, acting on the EMA output shaft (43).

- 3.

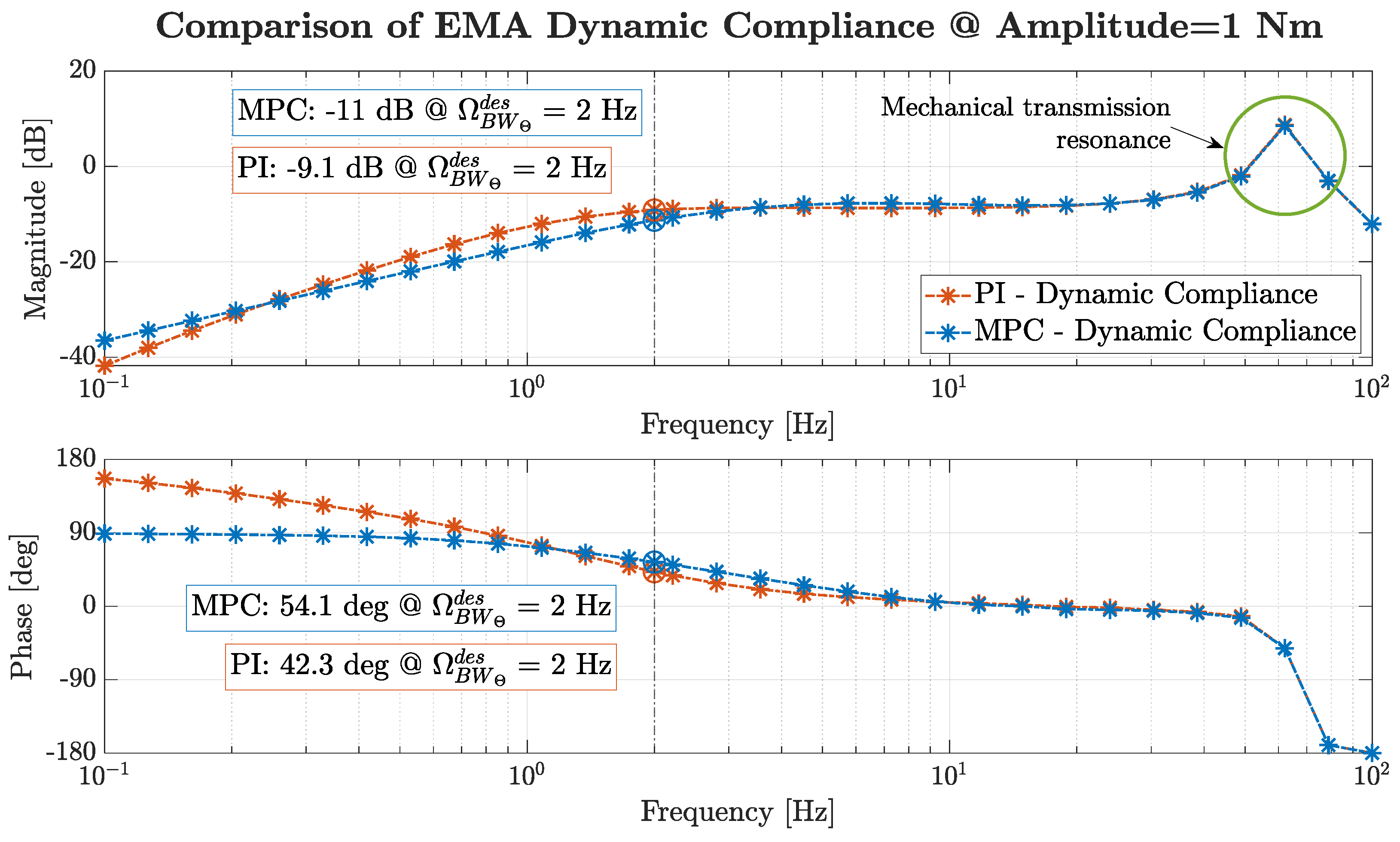

- The EMA dynamic compliance is derived imposing harmonic and step-like loads of 1 Nm amplitude.

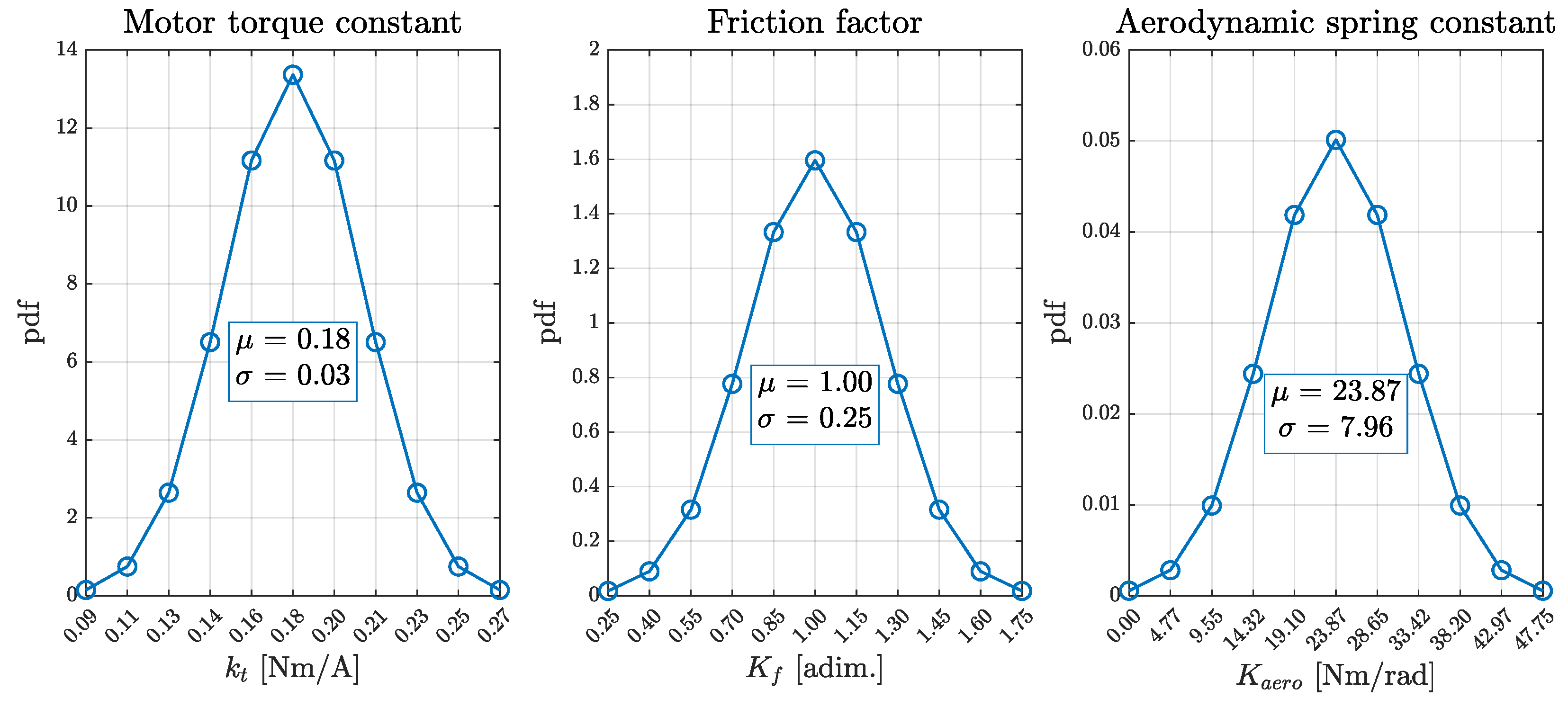

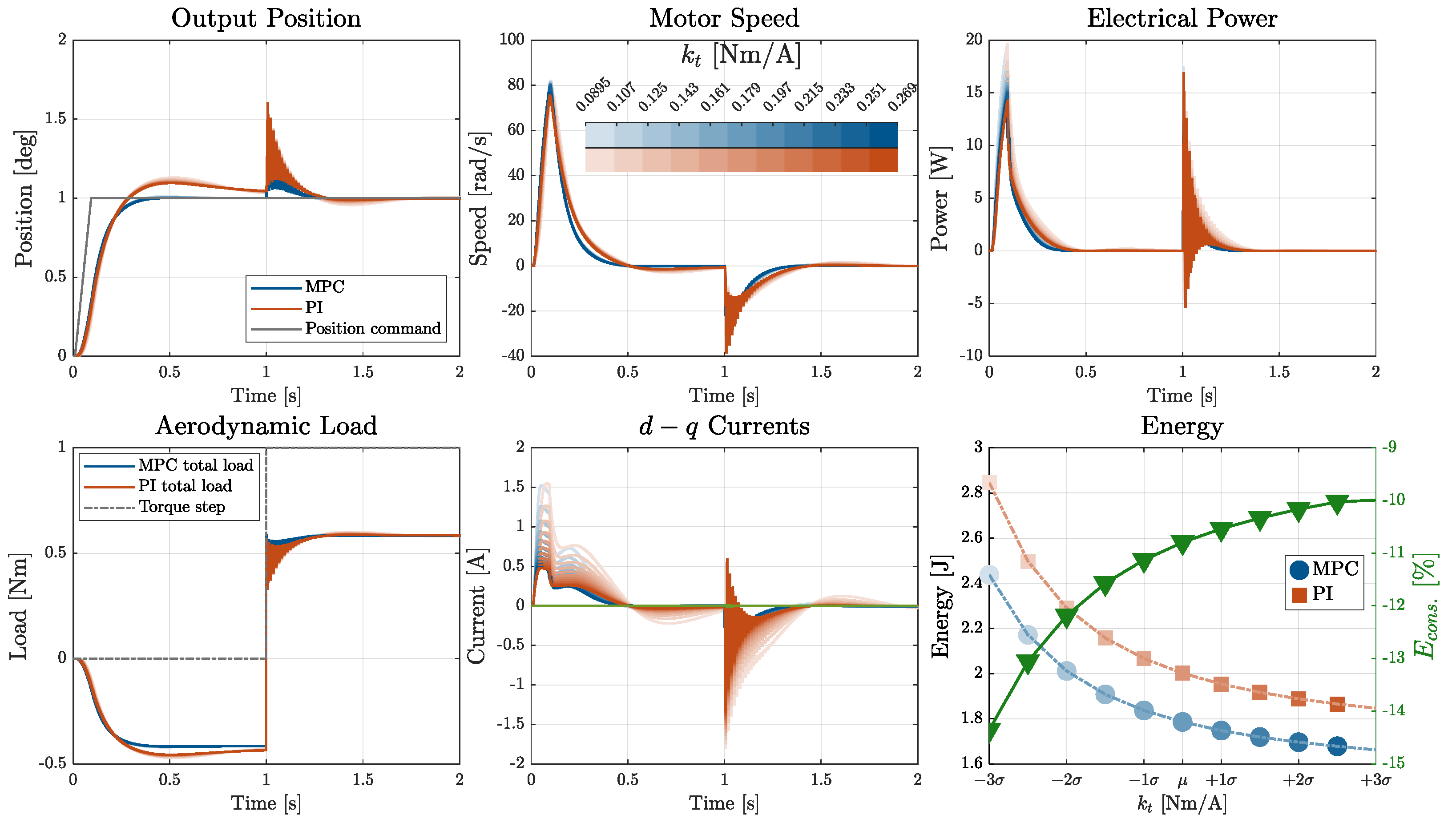

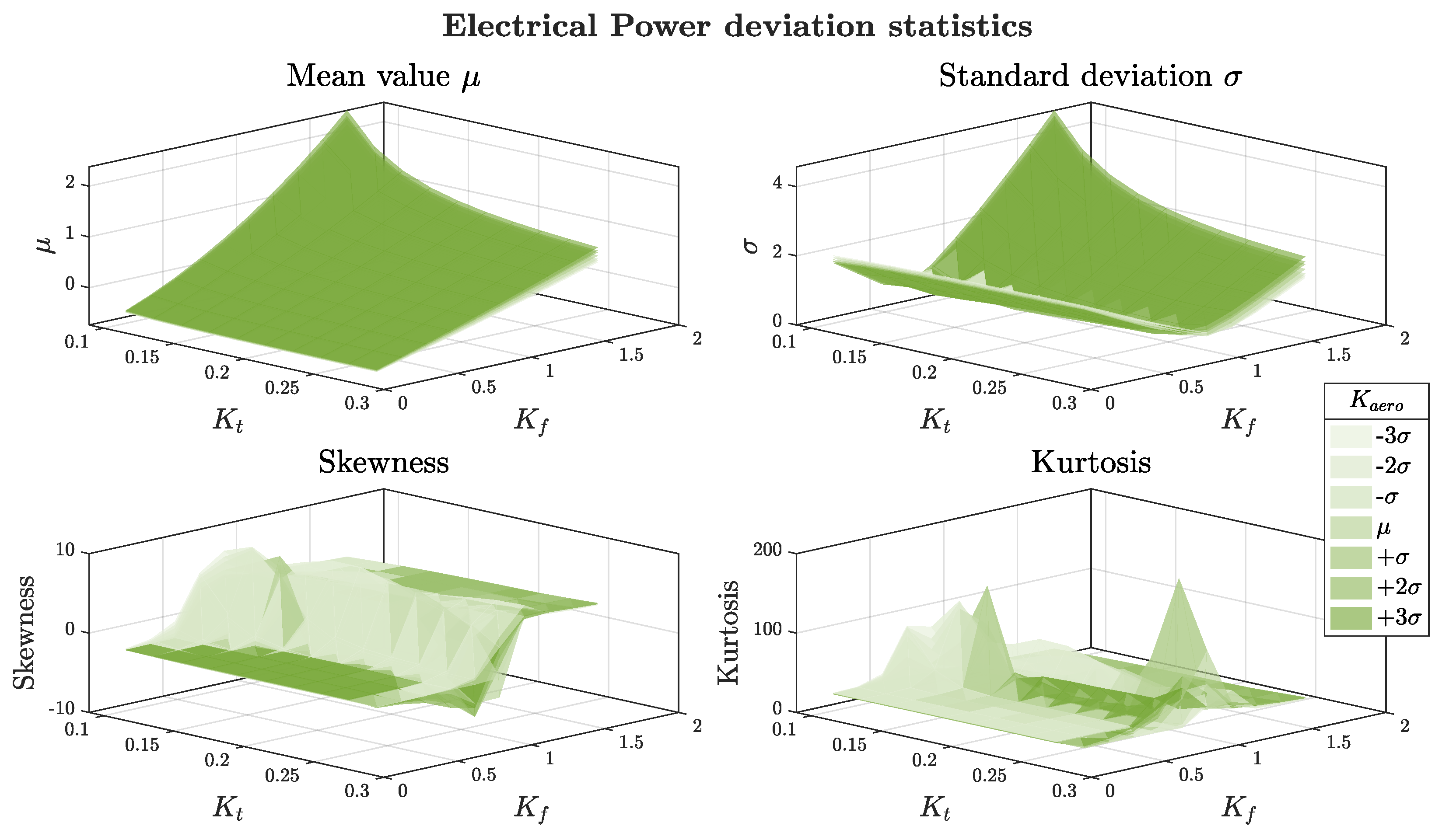

- PMSM torque constant kt ;

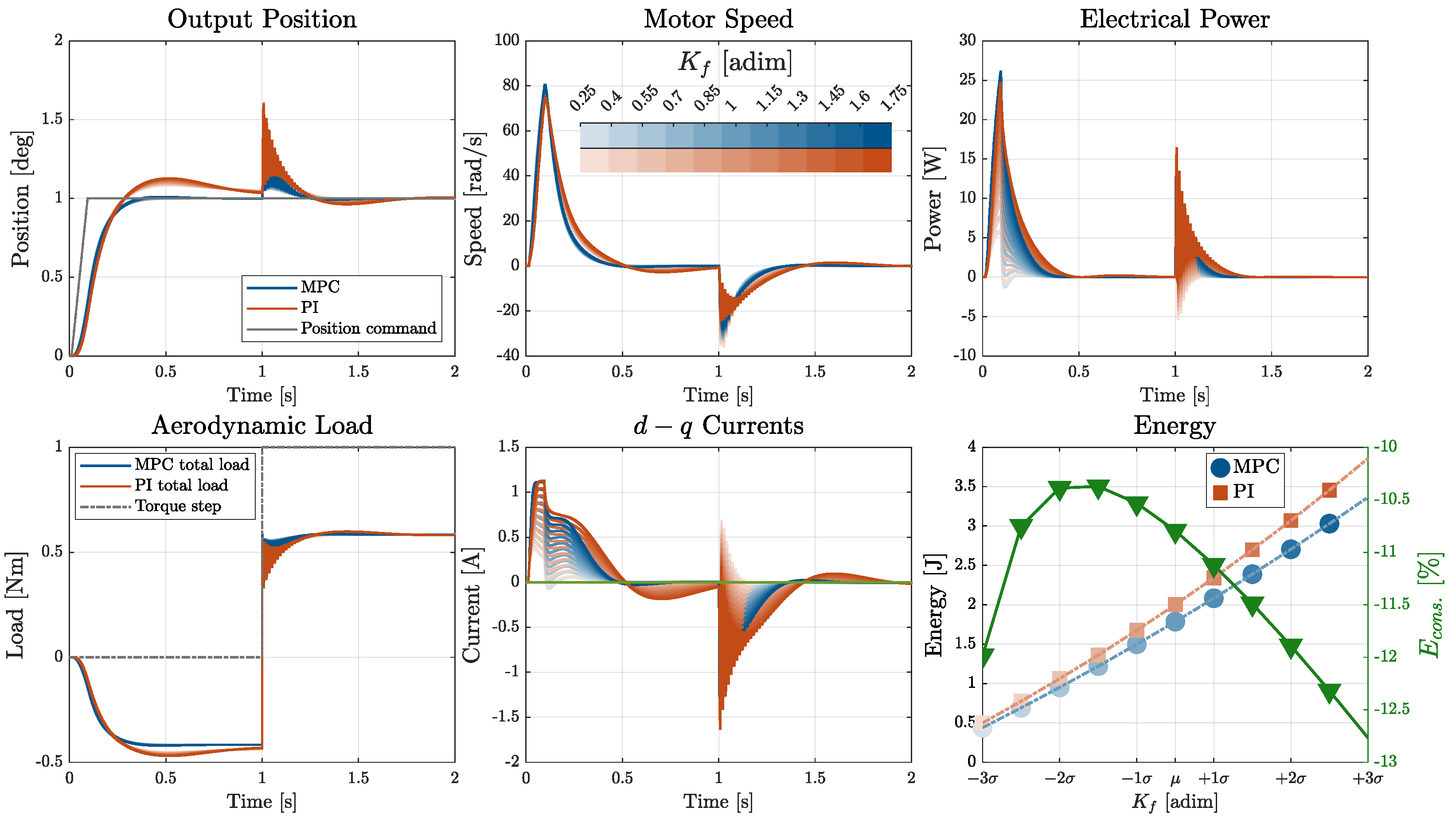

- friction torque multiplier Kf ;

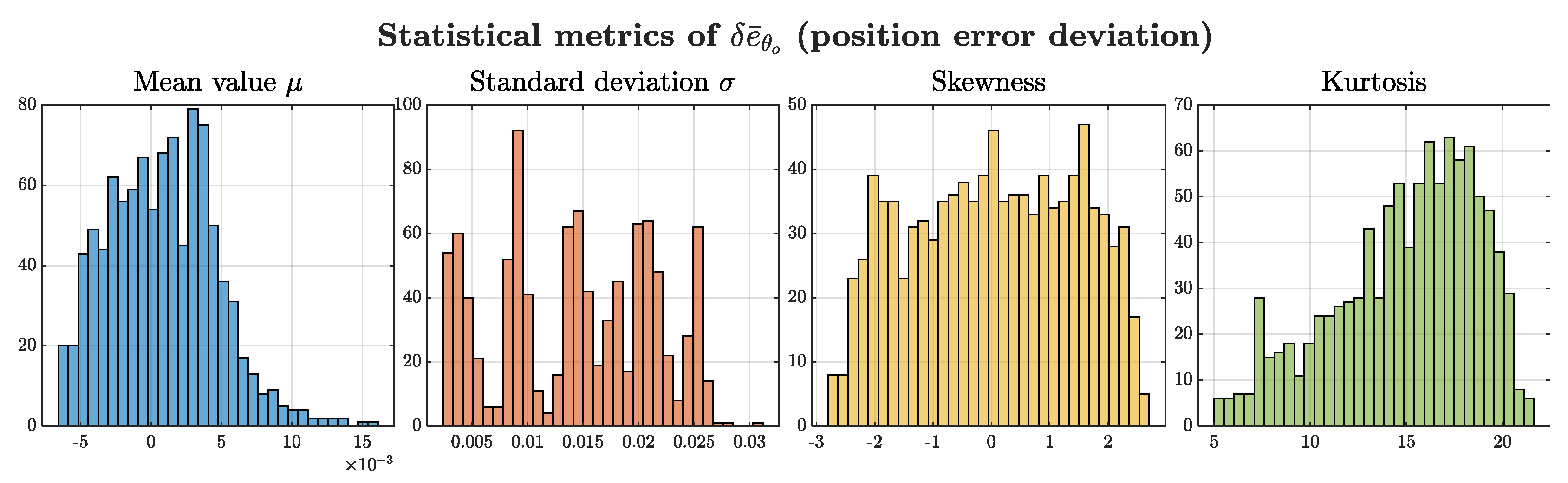

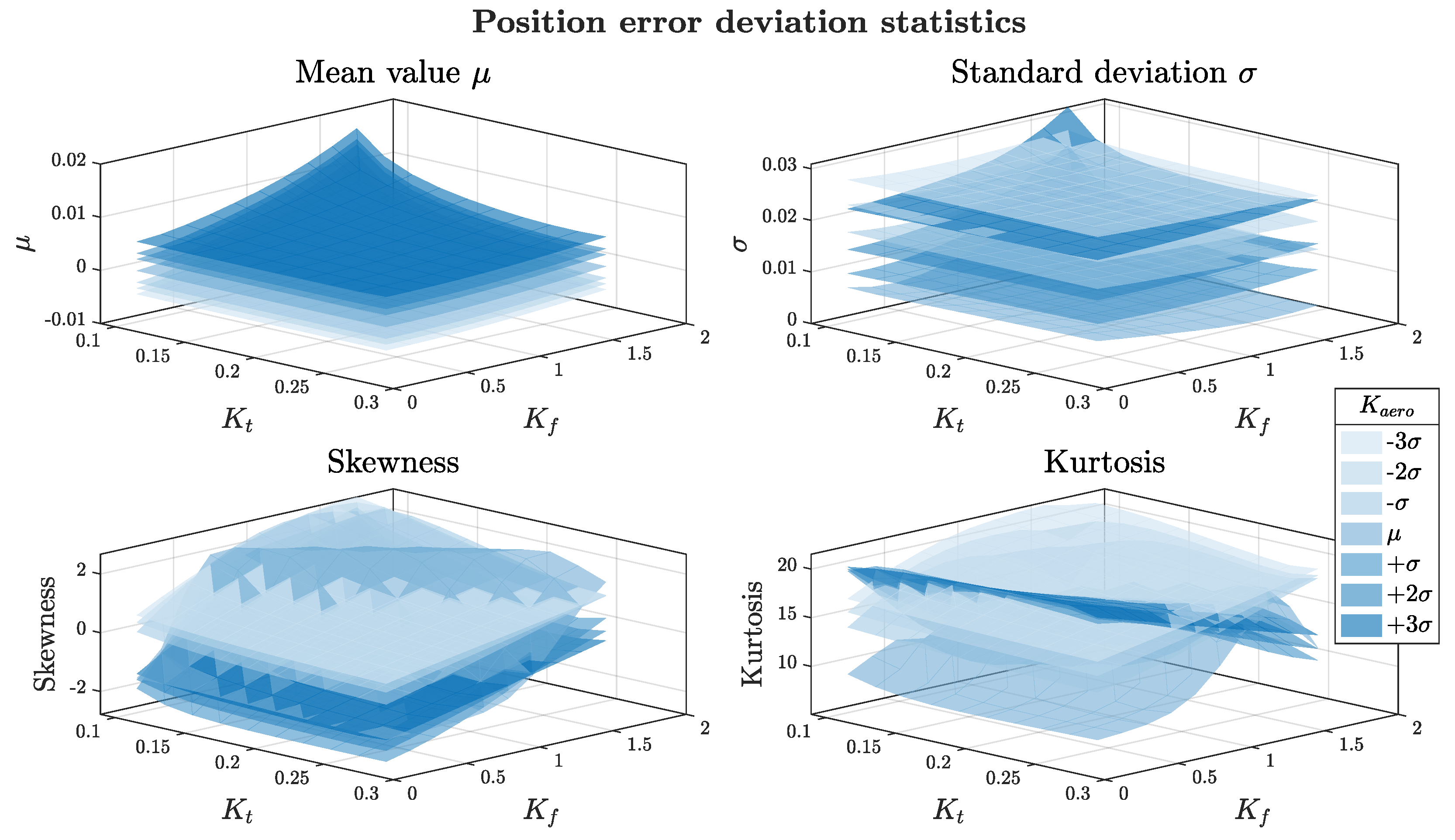

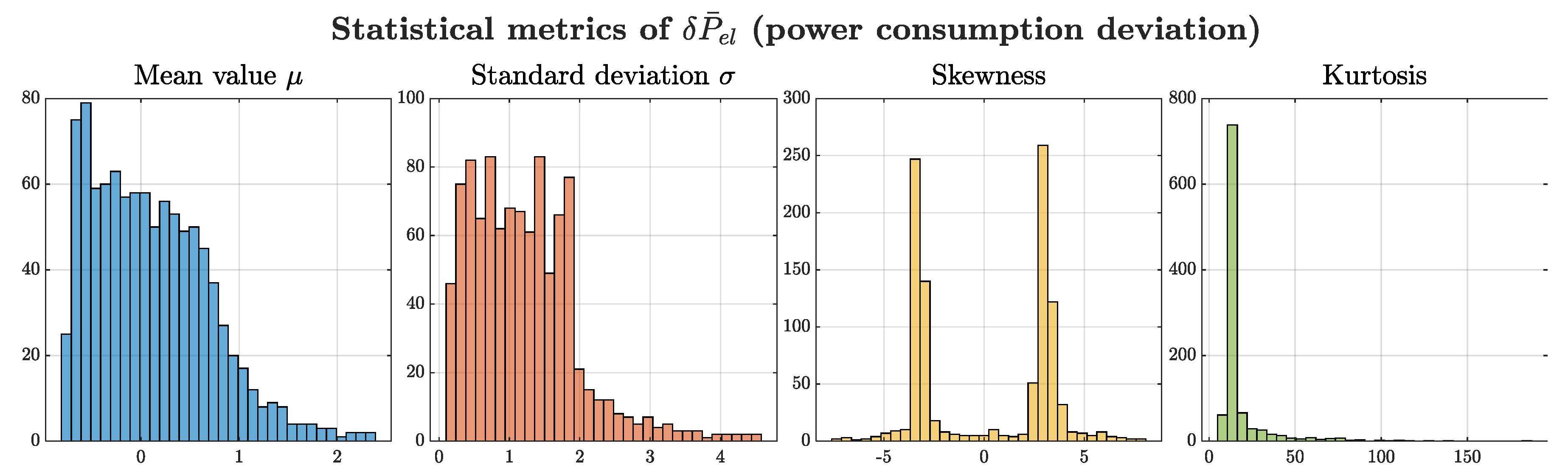

- equivalent aerodynamic spring load stiffness Kaero.

3. Results

3.1. Proportional-Integral Controllers Optimization

3.2. PI and MPC-Based Control Performance Comparison

3.2.1. Unloaded Position Tracking Tests

- At frequencies lower than 0.2 Hz the magnitude shall remain within ±1 dB, while the phase shall be higher than -10 deg.

- For frequencies between 0.2 Hz and 2 Hz, a linear increase in the magnitude is allowed till ±3 dB at the design bandwidth, whereas the phase shall remain above -60 deg.

- Beyond 2 Hz the magnitude is expected to decay with a slope between –20 dB/dec and –40 dB/dec, while the phase must be greater than -180 deg.

3.2.2. Loaded Position Tracking Tests

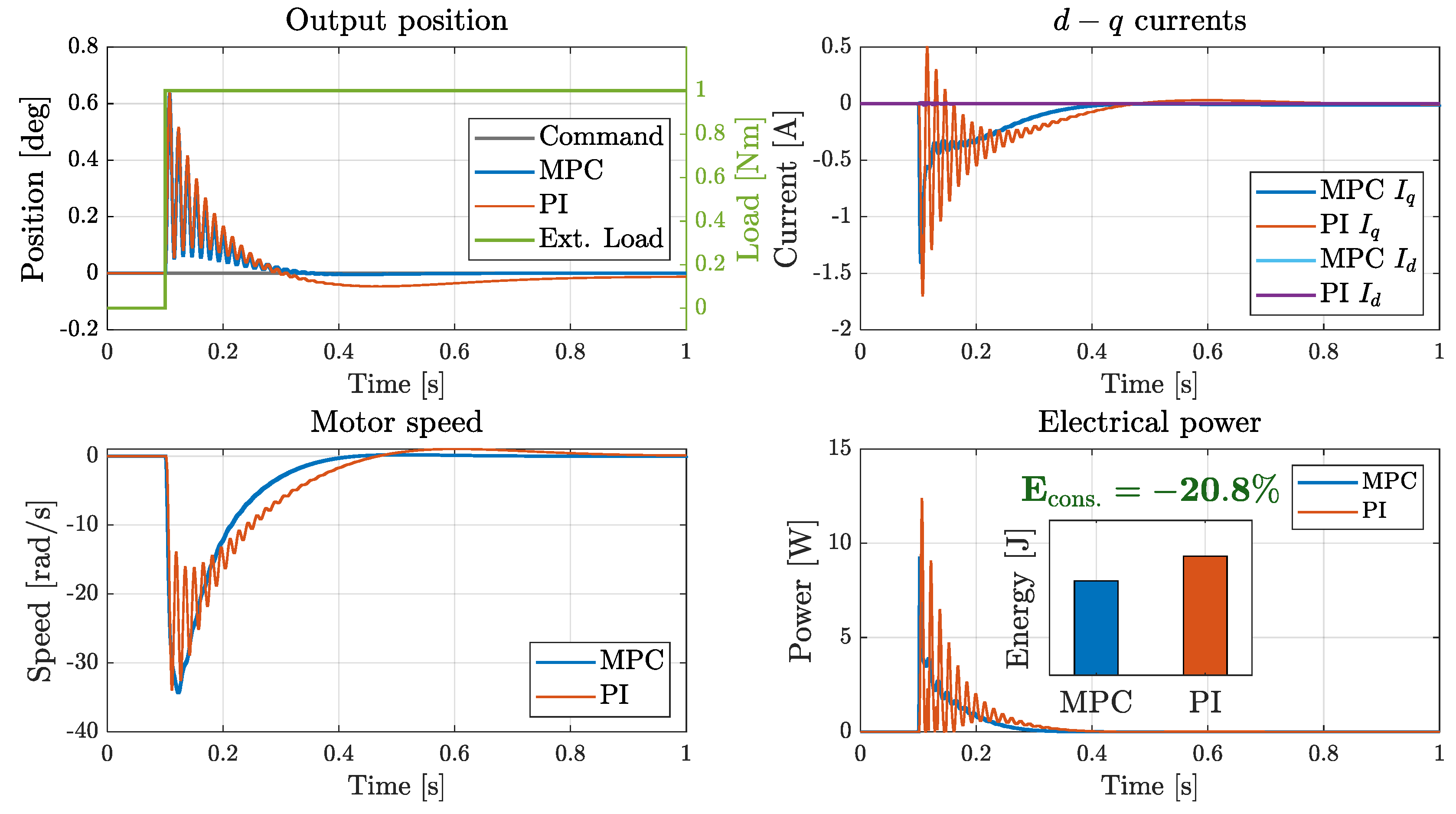

3.2.3. Load Disturbance Rejection Tests

3.3. Robustness Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarlioglu, B.; Morris, C.T. More Electric Aircraft: Review, Challenges, and Opportunities for Commercial Transport Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrific. 2015, 1, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buticchi, G.; Wheeler, P.; Boroyevich, D. The More-Electric Aircraft and Beyond. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.W.; Barrett, S.R.H.; Doyme, K.; Dray, L.; Gnadt, A.R.; Self, R.; O’Sullivan, A.; Synodinos, A.P.; Torija, A.J. Technological, economic and environmental prospects of all-electric aircraft. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Zhao, X.; Kyprianidis, K. A Review of Concepts, Benefits, and Challenges for Future Electrical Propulsion-Based Aircraft. Aerospace 2020, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannisson, J.; Asp, L.E.; Carlstedt, D.; Zenkert, D.; Johansen, M.; Carlson, J.; Willgert, M. Structural Batteries for Aeronautic Applications—State of the Art, Research Gaps and Technology Development Needs. Aerospace 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Barzkar, A.; Ghassemi, M. Electric Power Systems in More and All Electric Aircraft: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 169314–169332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savy, M. Control Surface Actuation for High Aspect Ratio Wings. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Aerospace Actuation Systems and Components, Toulouse, France, 25–28 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, M.; Di Domenico, G.; Pizzoni, L.; Borgarelli, N. Electromagnetic Design of a Fault-Tolerant Electromechanical Actuator for Landing Gear. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, Sorrento, Italy; pp. 677–682. [CrossRef]

- Salas, F. Electronics in Harsh Environment Reliability Update. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Aerospace Actuation Systems and Components, Toulouse, France, 25–28 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pispola, G.; Corradi, G.; Lavatelli, A.; Telteu, D. Advances in Mechanical Transmission Design for Flight Control EMAS. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Aerospace Actuation Systems and Components, Toulouse, France, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rito, G.; Galatolo, R.; Schettini, F. Experimental and simulation study of the dynamics of an electro-mechanical landing gear actuator. In Proceedings of the 30th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS), Daejeon, Korea, 25–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rito, G.; Kovel, R.; Nardeschi, M.; Borgarelli, N.; Luciano, B. Minimisation of Failure Transients in a Fail-Safe Electro-Mechanical Actuator Employed for the Flap Movables of a High-Speed Helicopter-Plane. Aerospace 2022, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rito, G.; Luciano, B.; Borgarelli, N.; Nardeschi, M. Model-Based Condition-Monitoring and Jamming-Tolerant Control of an Electro-Mechanical Flight Actuator with Differential Ball Screws. Actuators 2021, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rito, G.; Luciano, B.; Borgarelli, N.; Nardeschi, M. Health-Monitoring of a Jamming Tolerant Electro-Mechanical Actuator with Differential Ball Screws. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Aerospace, Italy, 22–24 June 2020. Available online:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgarelli, N.; D’Andrea, M.; Pizzoni, L.; Alfano, L.; Guidi, G.; Mare, J.-C. Electro-Mechanical Actuator for Morphing Winglet and Innovative Wingtip Surfaces. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Aerospace Actuation Systems and Components, Toulouse, France, 25–28 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maré, J.-C. Review and Analysis of the Reasons Delaying the Entry into Service of Power-by-Wire Actuators for High-Power Safety-Critical Applications. Actuators 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagetti, F.; Borgarelli, N.; Malleret, F.; Pelliccia, S. Fault-Tolerant Electric Actuation: A Condition to Make Electric Platforms Certifiable. In Proceedings of the Vertical Flight Society’s 80th Annual Forum & Technology Display, Montréal, Québec, Canada, 7–9 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barambones, O.; Cortajarena, J.A.; Alkorta, P. New Control Schemes for Actuators. Actuators 2024, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rito, G.; Kovel, R.; Luciano, B.; Salvi, F.; Nardeschi, M. Failure Transients Characterization for the Qualification of the Fail-Safe EMA Used for the Airbus RACER Flap Movables. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Aerospace Actuation Systems and Components, Toulouse, France, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings, J.B.; Mayne, D.Q.; Diehl, M. Model Predictive Control: Theory, Computation, and Design, 2nd ed.; Nob Hill Publishing: Madison, WI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, E.F.; Bordons, C. Model Predictive Control, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–408. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, U.; Prach, A.; Kocer, B.; Raković, S.V.; Kayacan, E.; Açıkmeşe, B. Model Predictive Control in Aerospace Systems: Current State and Opportunities. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2017, 40, 1541–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTCA. DO-178C: Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification; RTCA, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kopf, M.; Bullinger, E.; Giesseler, H.; Adden, S.; Findeisen, R. Model Predictive Control for Aircraft Load Alleviation: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 27–29 June 2018; pp. 2417–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, W.; Hencey, B.; Girard, A.R.; Kolmanovsky, I. Distributed Model Predictive Control for More Electric Aircraft Subsystems Operating at Multiple Time Scales. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 28, 2177–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegrenæs, Ø.; Gravdahl, J.; Tøndel, P. Spacecraft Attitude Control Using Explicit Model Predictive Control. Automatica 2005, 41, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, P.; Subbarao, K. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Aerospace 2017, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.A.; Keshmiri, S.S.; Stastny, T. Robust and Adaptive Nonlinear Model Predictive Controller for Unsteady and Highly Nonlinear Unmanned Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2015, 23, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Wang, L.; Rogers, E. Model Predictive Control of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. In Proceedings of the IECON 2011—37th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 7–10 November 2011; pp. 1928–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatola, S.; Pastorelli, M.A. Predictive Control of Permanent Magnets Synchronous Motors. Master’s Thesis, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cimini, G.; Bernardini, D.; Bemporad, A.; Levijoki, S. Online Model Predictive Torque Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, Seville, Spain, 17–19 March 2015; pp. 2308–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.D.S.; Hafni, A.E.; Kennel, R. Position Control of an Electromagnetic Actuator Using Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Predictive Control of Electrical Drives and Power Electronics, Pilsen, Czech Republic, 11–13 September 2017; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgarelli, N.; Pizzoni, L. Rotary Mechanical Screw Transmission; European Patent Office: EP4042039, 9 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Research and Development – European Commission, Clean Aviation, CleanSky2 Demonstrators, RACER Compound Helicopter. Available online: https://www.clean-aviation.

- Yao, H.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Xia, C. A Novel SVPWM Scheme for Field-Oriented Vector-Controlled PMSM Drive System Fed by Cascaded H-Bridge Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 8988–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sul, S. Control of Electric Machine Drive Systems, 1st ed.; Wiley-IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0470590799. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Model Predictive Control System Design and Implementation Using MATLAB, 1st ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, C. A quadratic programming procedure. Naval Res. Logist. 1957; 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quantity | Meaning | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jm | Motor shaft inertia | 4⋅10-5 | kgm2 |

| Jo | Output shaft inertia | 1⋅10-3 | kgm2 |

| Kg | Drivetrain torsional stiffness | 166.8 | Nm/rad |

| Cg | Drivetrain torsional damping (I° mode) | 0.0408 | Nms/rad |

| τg | Differential ball-screw gear ratio | 500 | [-] |

| Bm | Viscous friction coefficient | 0.0716 | Nms/rad |

| Tc | Coulomb friction torque | 3.42⋅10-4 | Nm |

| ωc | Coulomb velocity | 10.5 | rad/s |

| Tcmax | Maximum output torque | 25 | Nm |

| θomax | Maximum angular deflection | ±30 | deg |

| ωomax | Maximum output speed | 12 | deg/s |

| ωmmax | Maximum motor speed | 105 | rad/s |

| kt | Motor torque constant | 0.179 | Nm/A |

| Kaeroeq | Equivalent aerodynamic spring stiffness | 23.87 | Nm/rad |

| Iqmax | Maximum quadrature current | 4 | A |

| Rph | Phase resistance | 1.53 | Ω |

| Lph | Phase inductance | 15 | mH |

| nd | Number of pole pairs | 10 | [-] |

| VDCmax | Maximum BUS DC voltage | 36 | V |

| Sensor type | Bandwidth | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Resolver (m, o) | 200 | Hz |

| Hall-effect Current sensor (d, q) | 40.000 | Hz |

| Quantity | Meaning | Current loop | Speed loop | Position loop | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ωbw | Bandwidth | 200 · 2π | 20 · 2π | 2 · 2π | rad/s |

| φm | Phase margin | ≥ 45 | ≥ 45 | ≥ 45 | deg |

| Km | Gain margin | ≥ 6 | ≥ 6 | ≥ 6 | dB |

| Quantity | Meaning | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIq | Current loop proportional gain | 16.347 | V/A |

| zIq | Current loop integrator zero | 628.318 | rad/s |

| Kω | Motor speed loop proportional gain | 0.0294 | A s/rad |

| zω | Motor speed loop integrator zero | 18.850 | rad/s |

| Kθ | Output position loop proportional gain | 6085.21 | 1/s |

| zθ | Output position loop integrator zero | 1.256 | rad/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).