Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

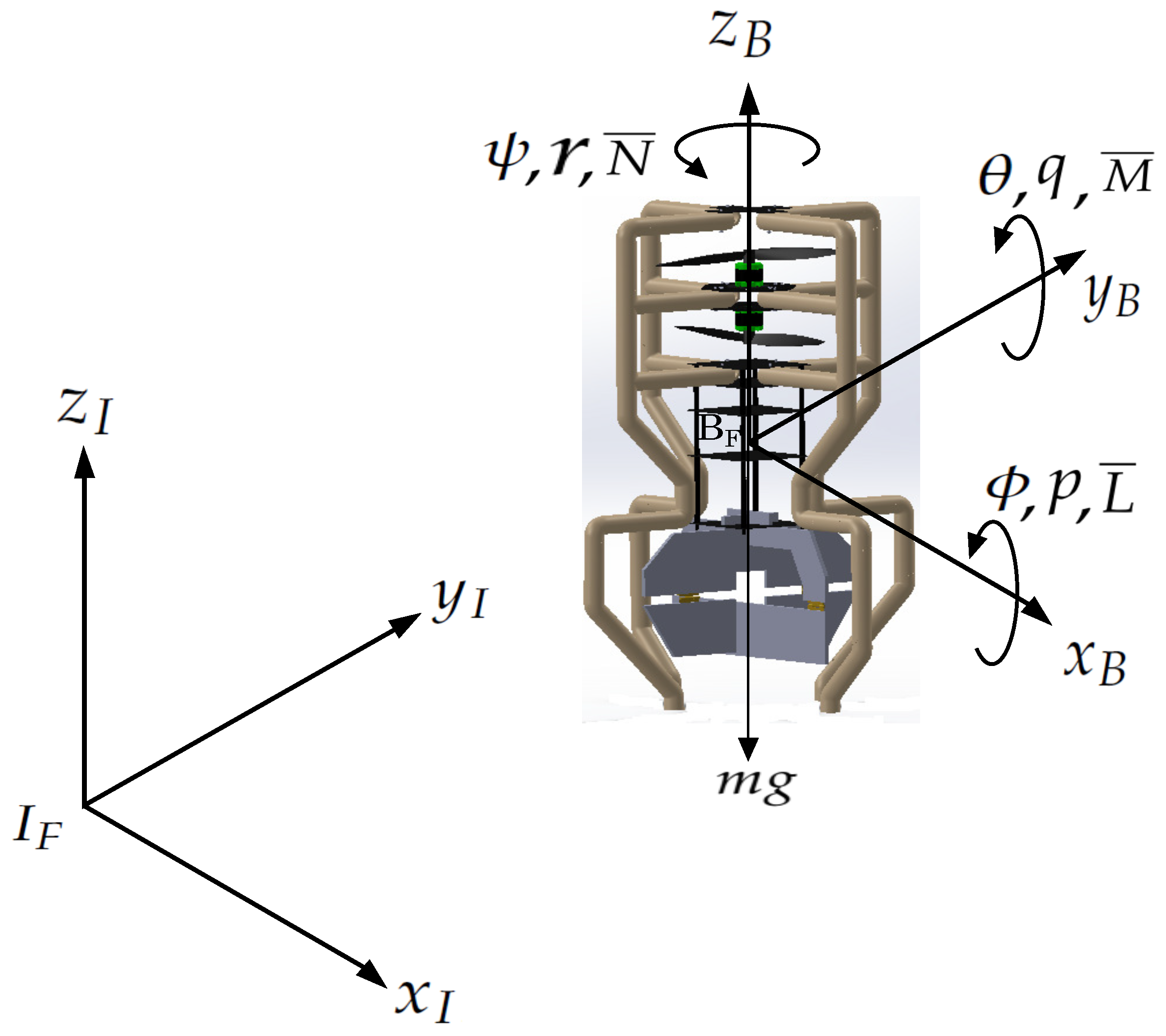

2. Coaxial-Rotor MAV Mathematical Model

2.1. Pitch Angle Response

3. Linear and Nonlinear Controllers Design

4. Simulation Results

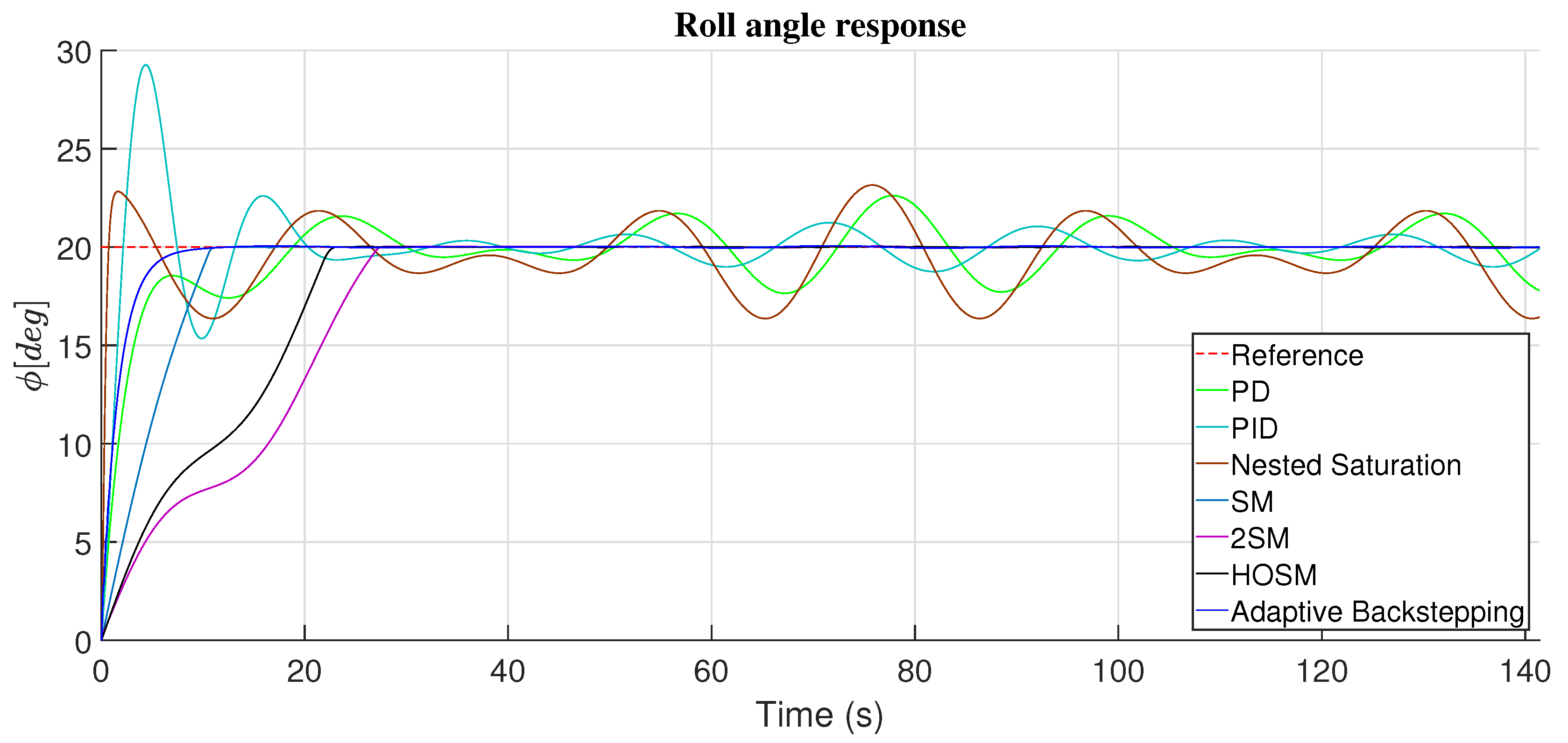

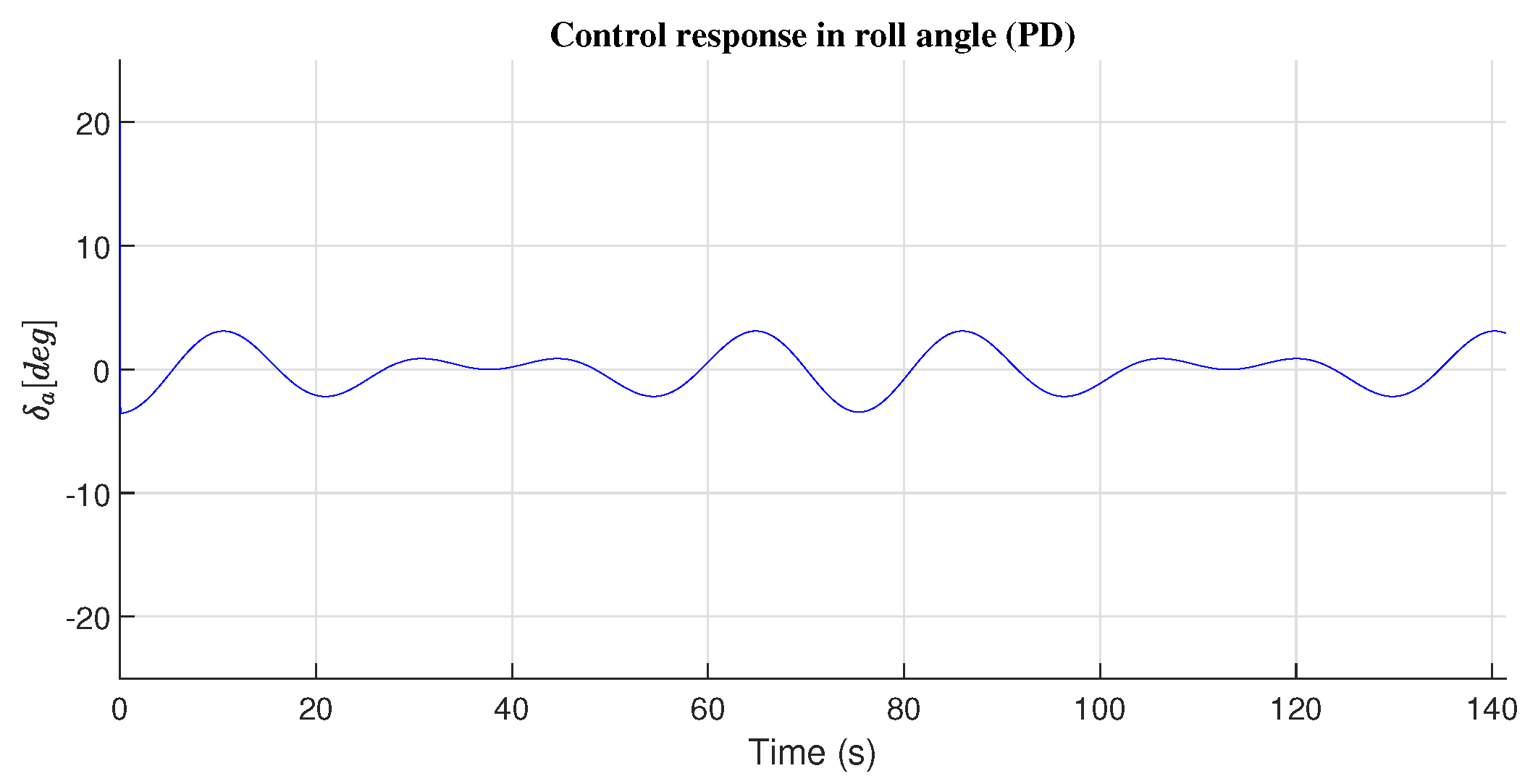

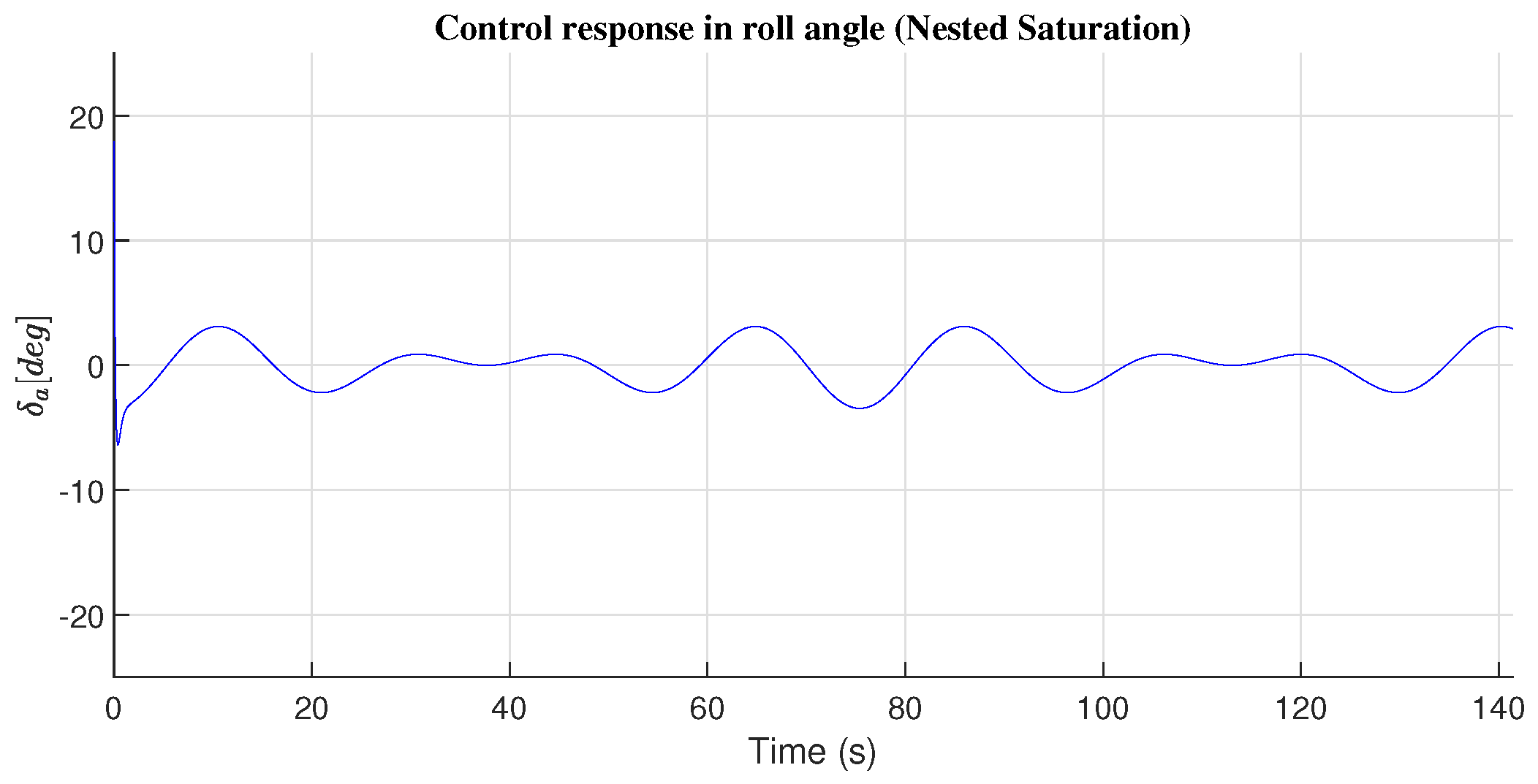

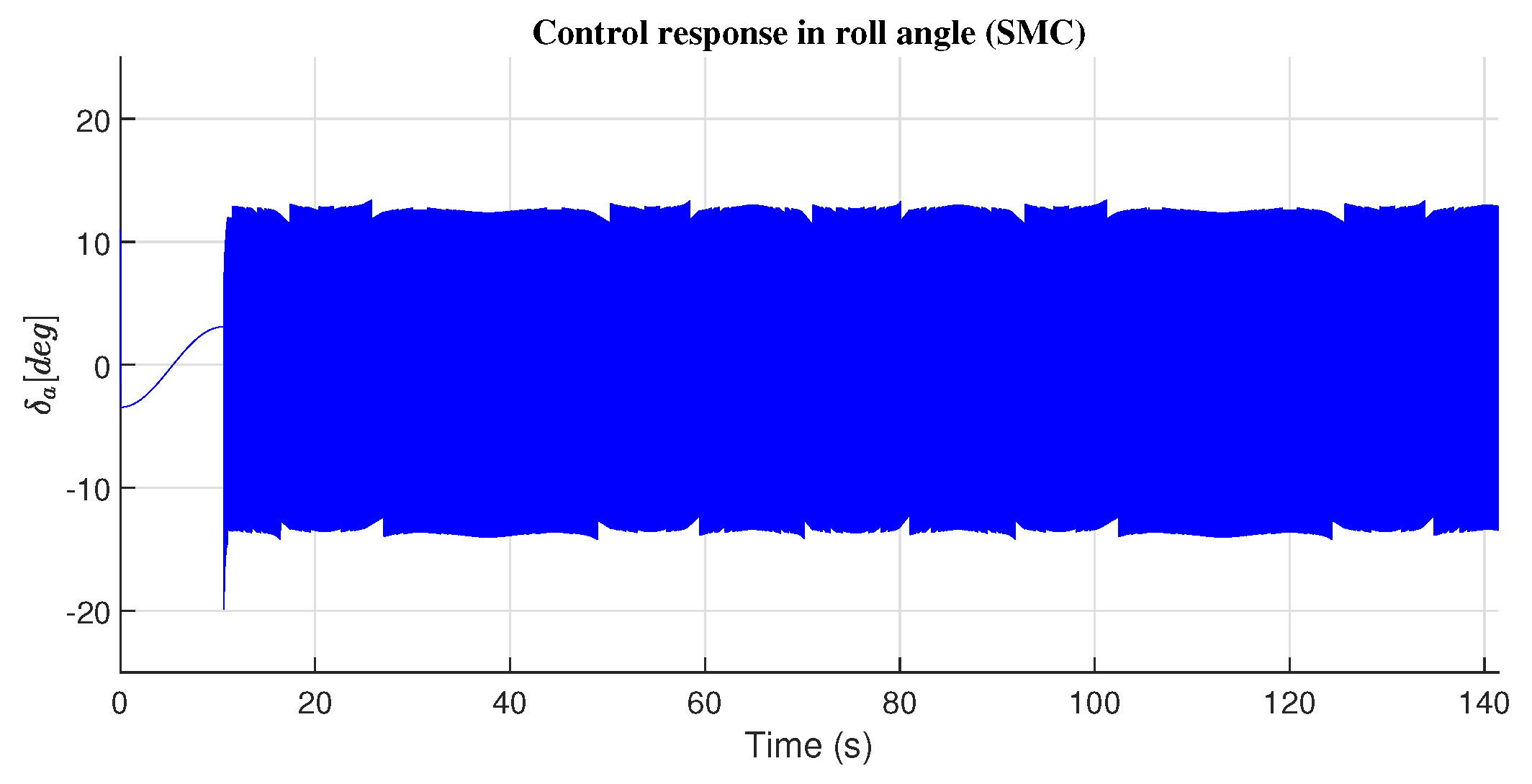

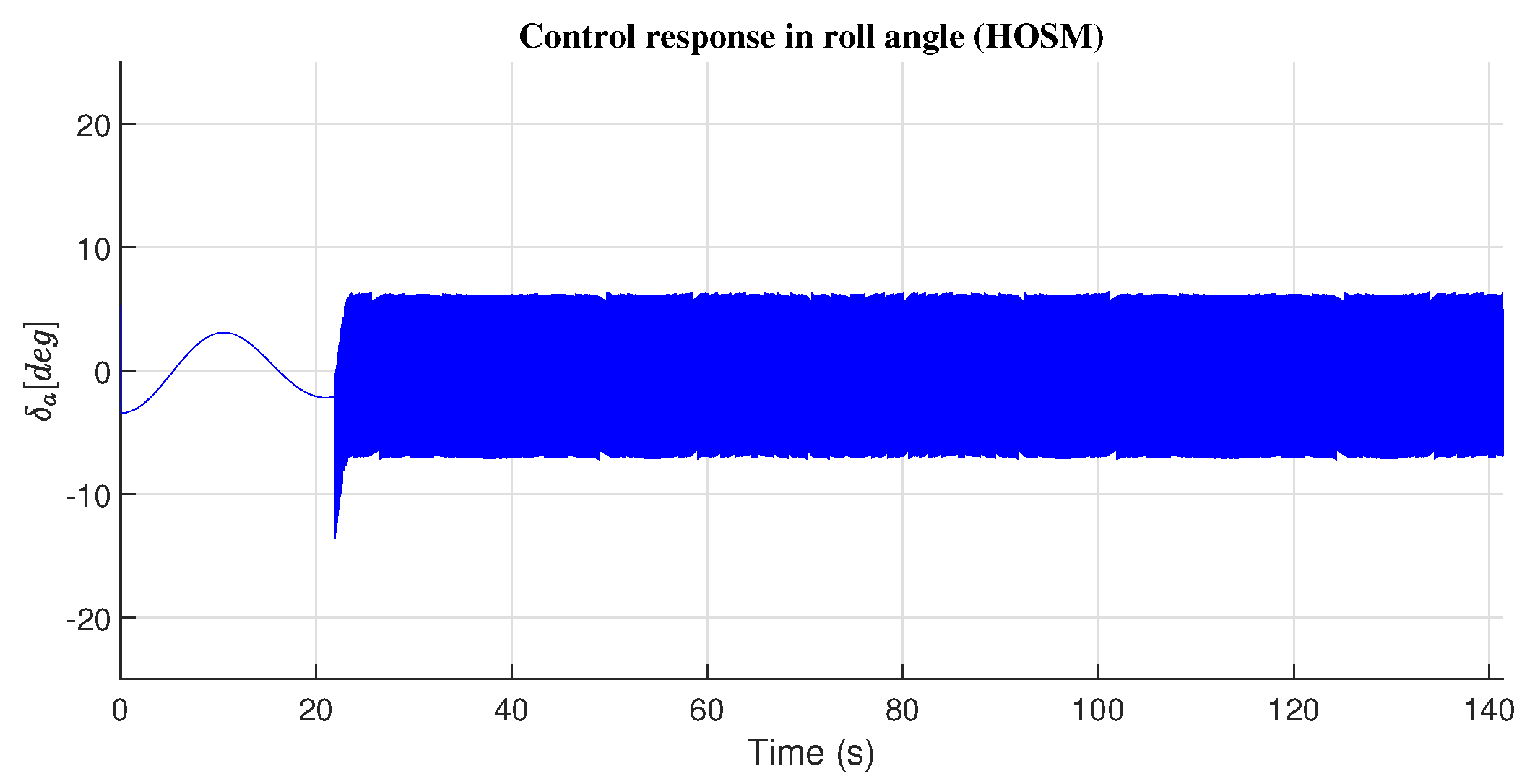

4.1. Roll Angle Response

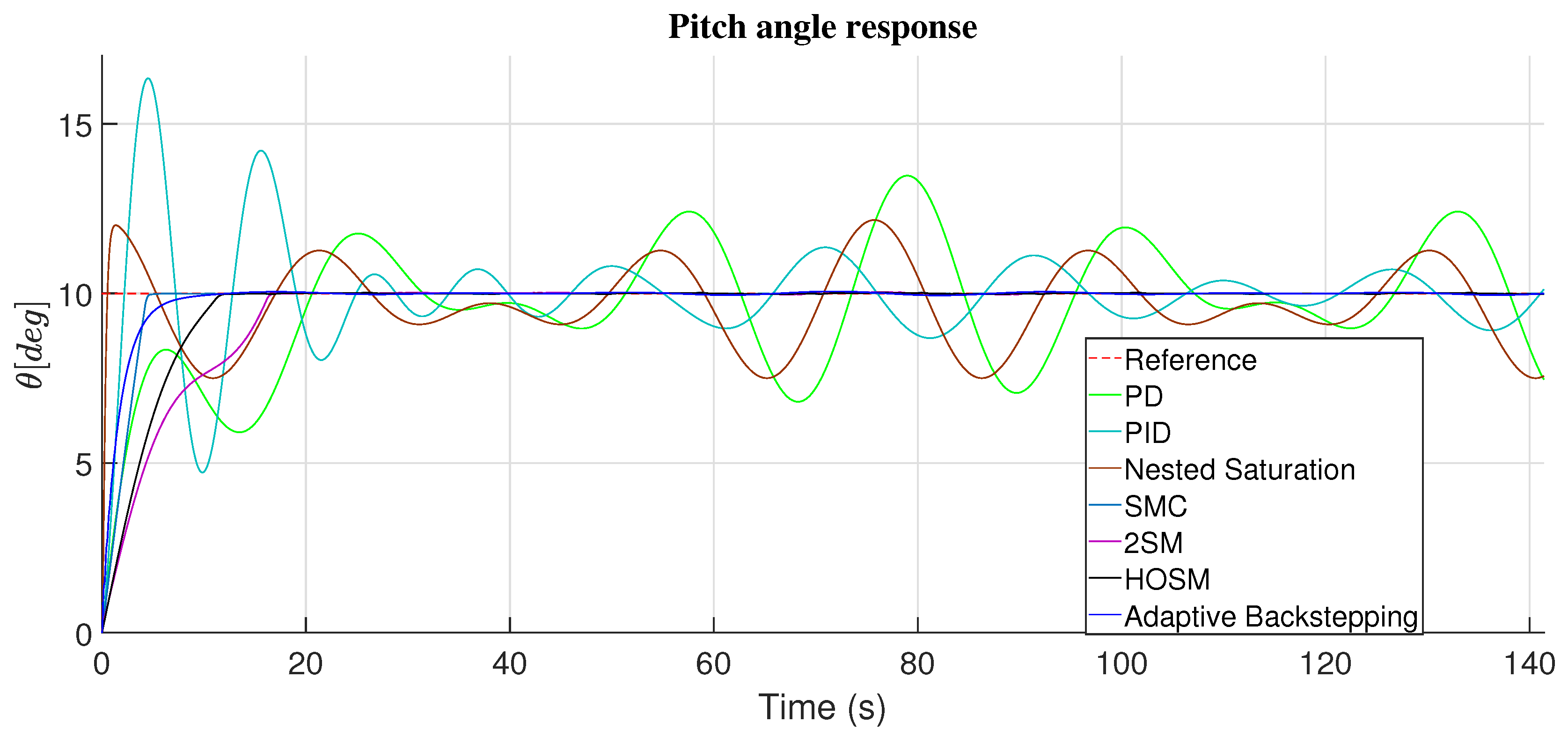

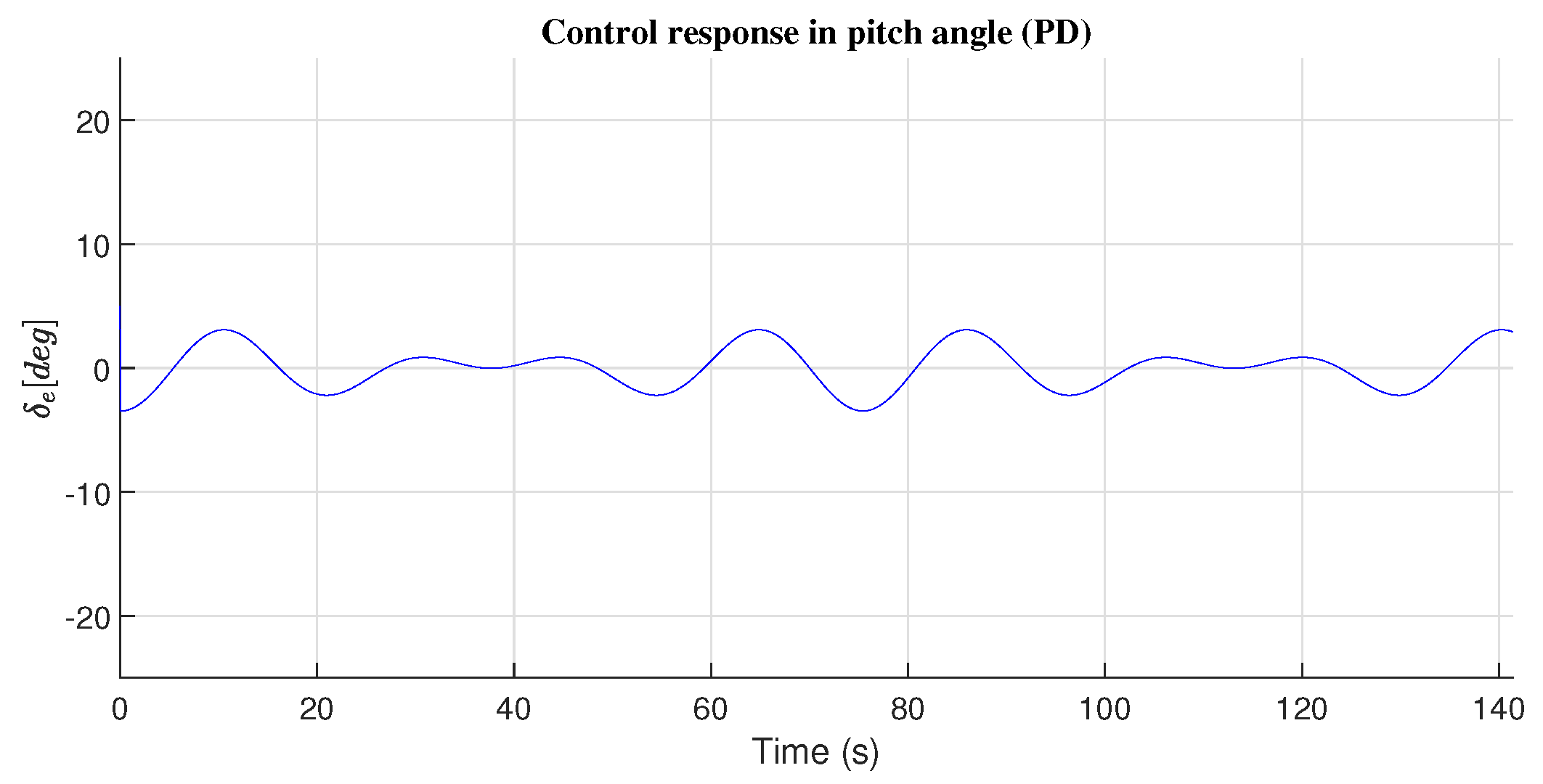

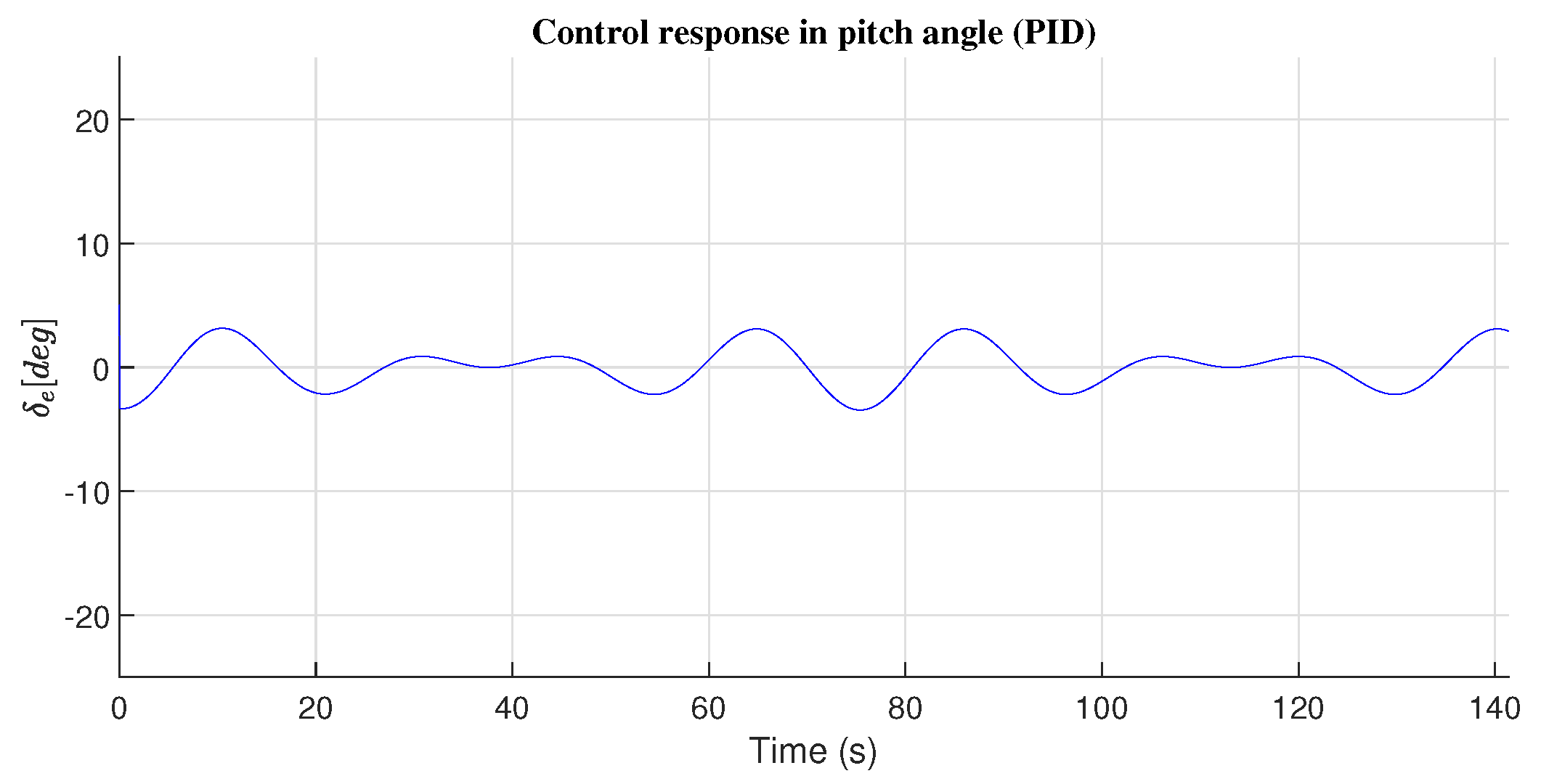

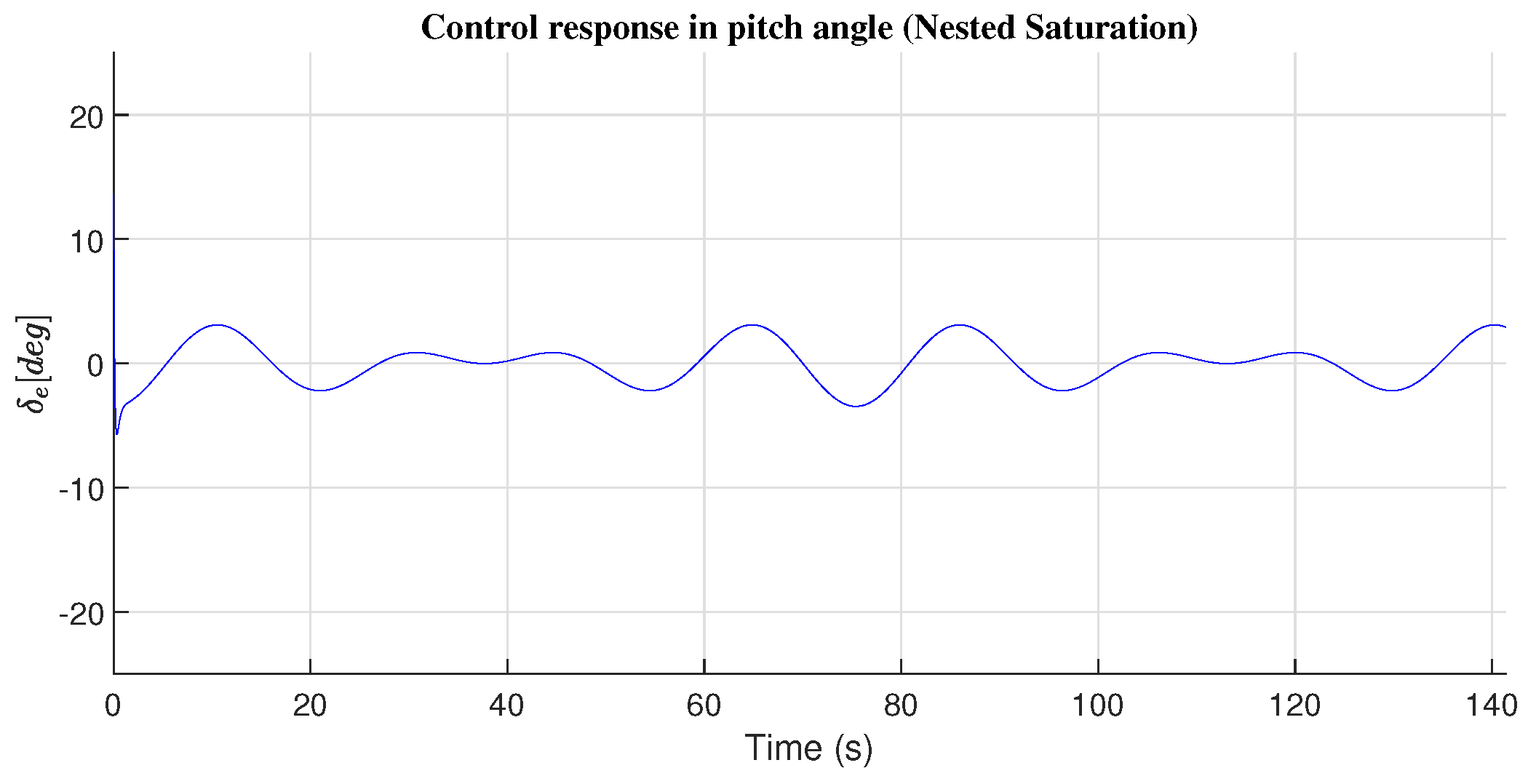

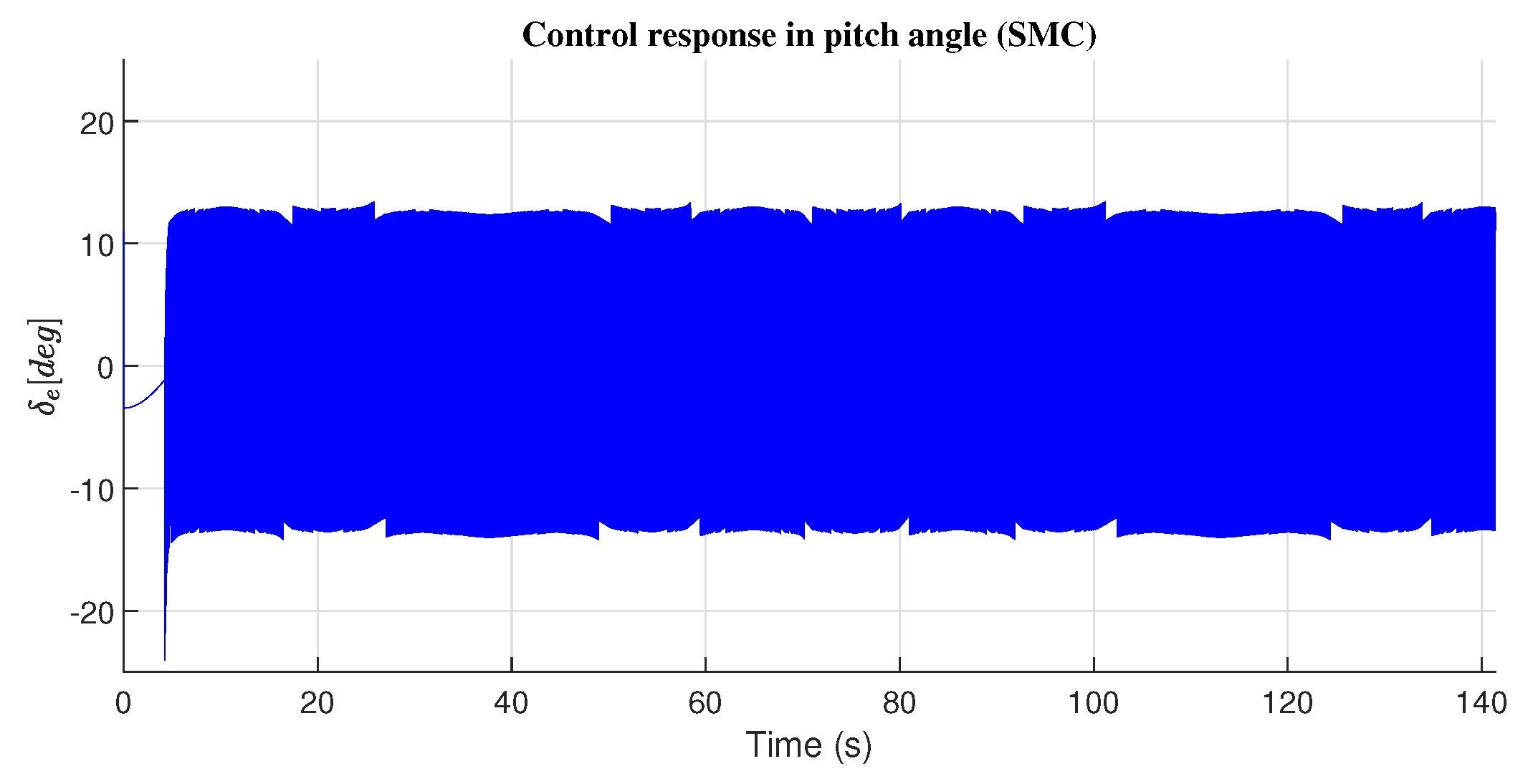

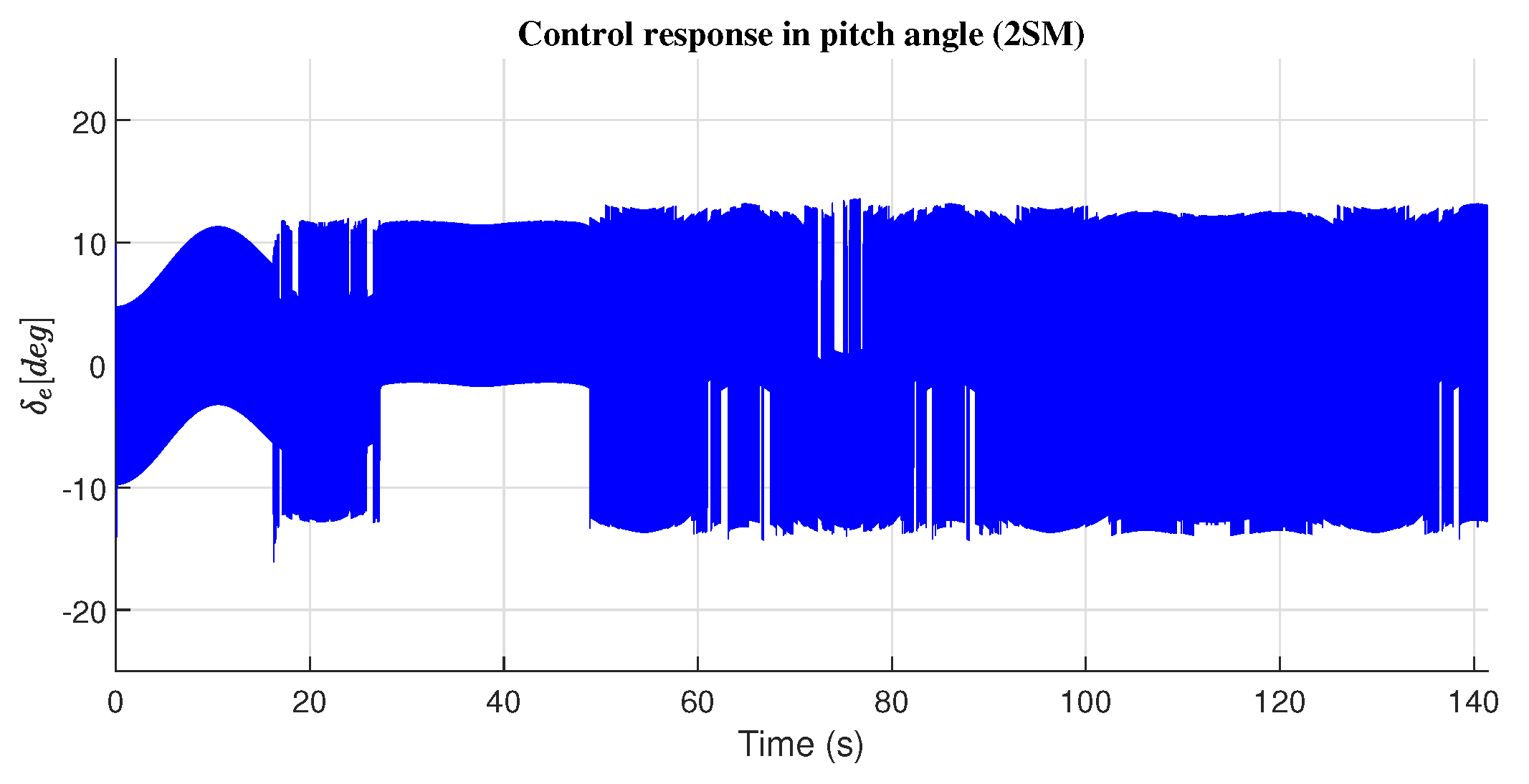

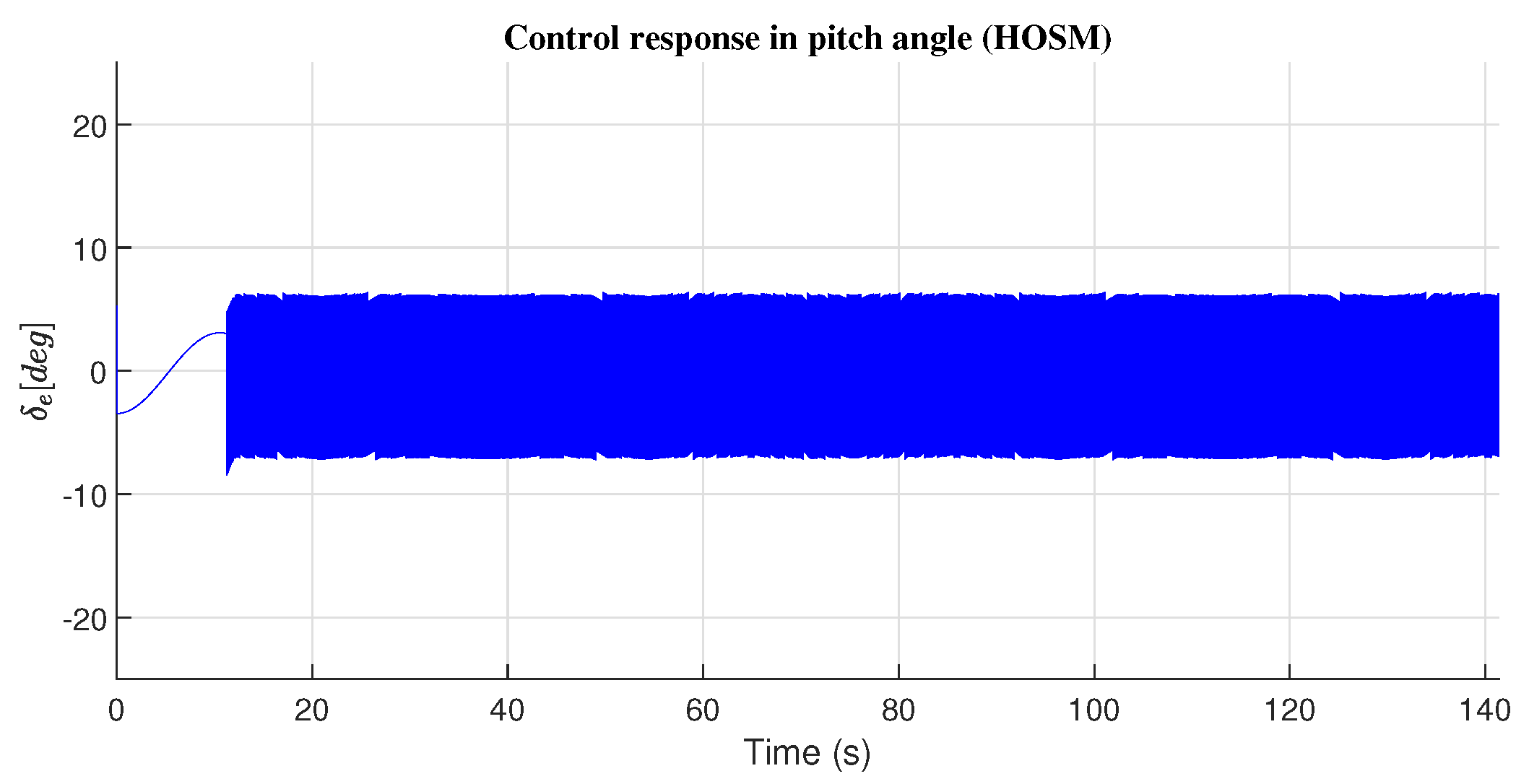

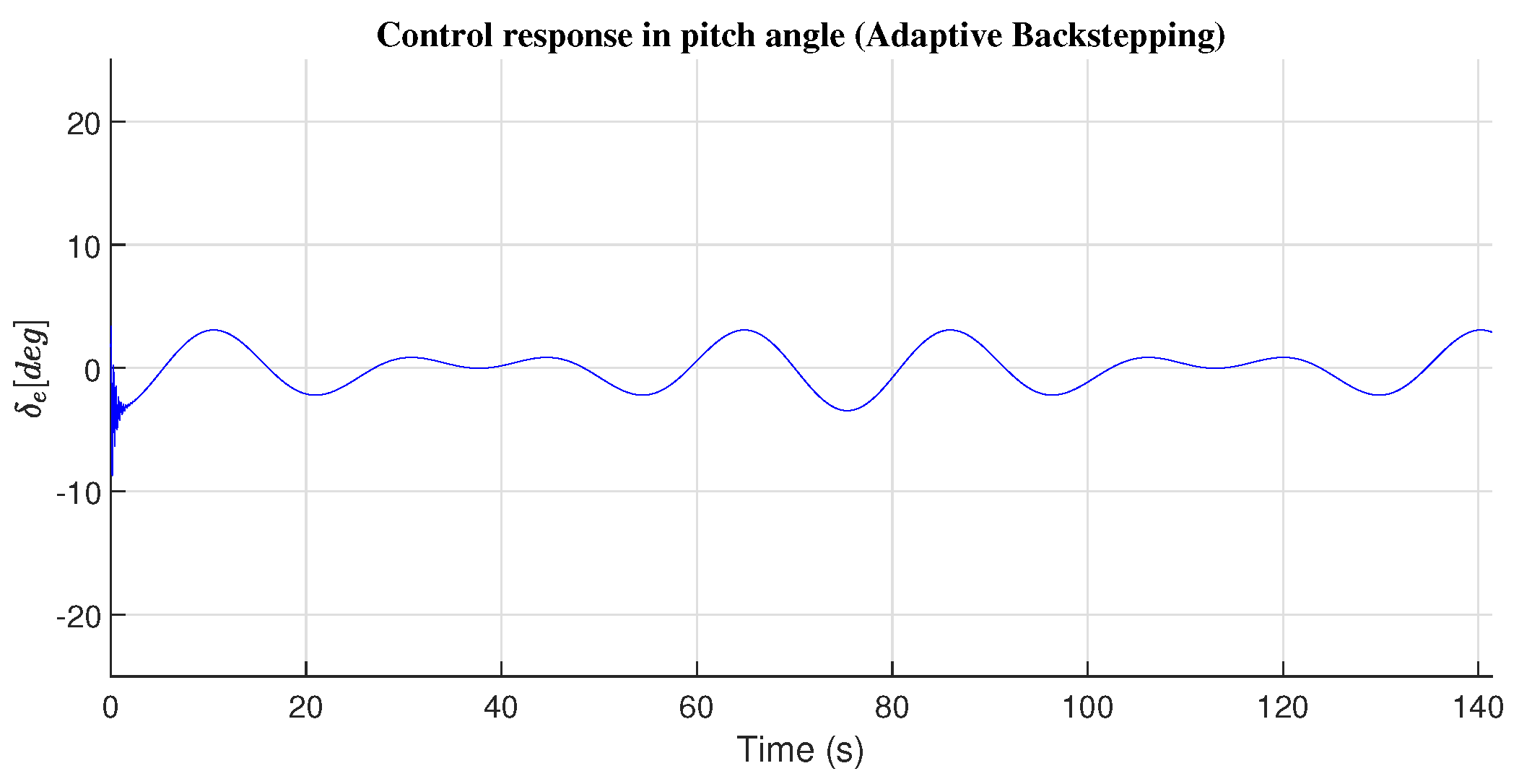

4.2. Pitch Angle Response

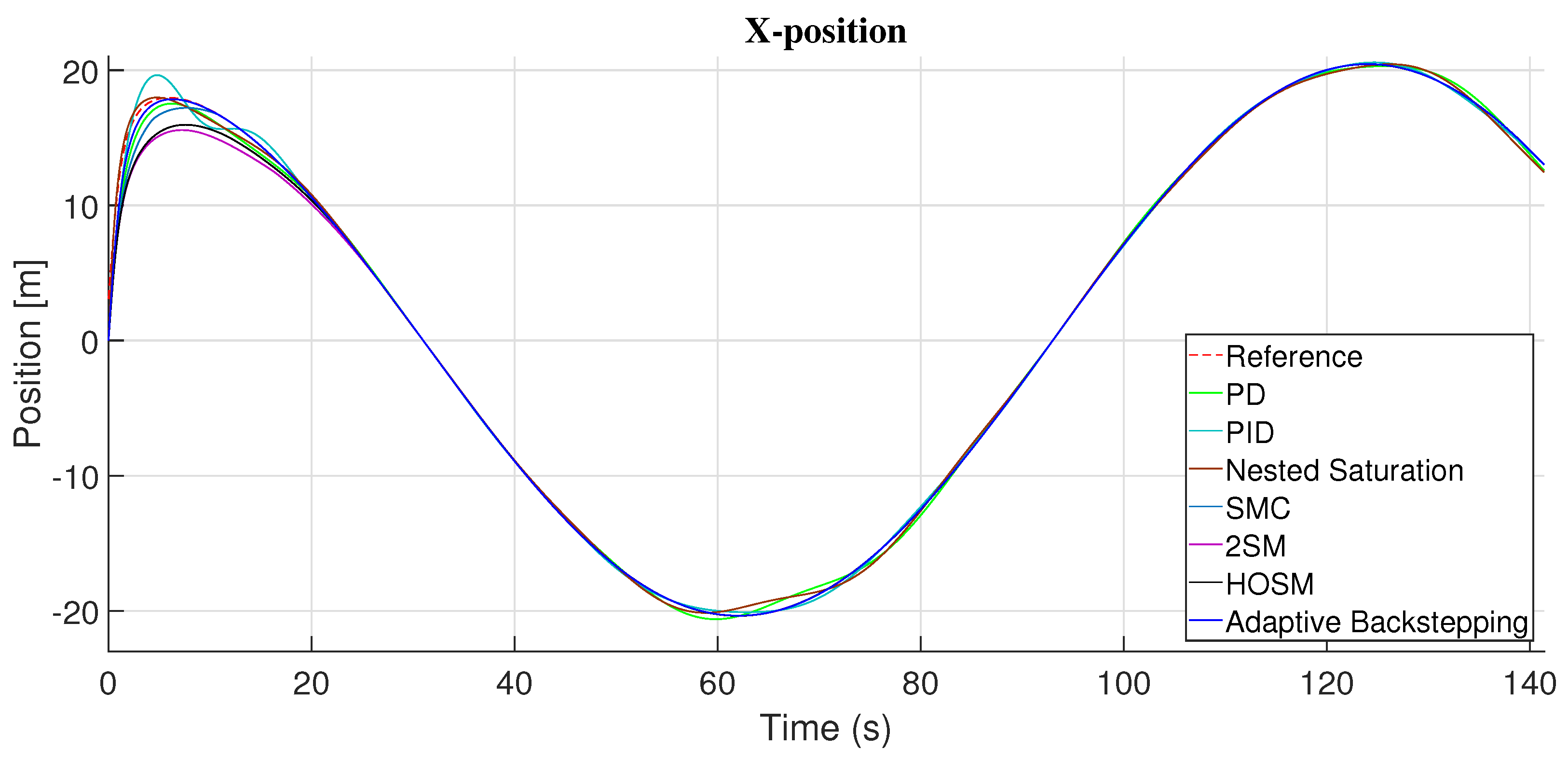

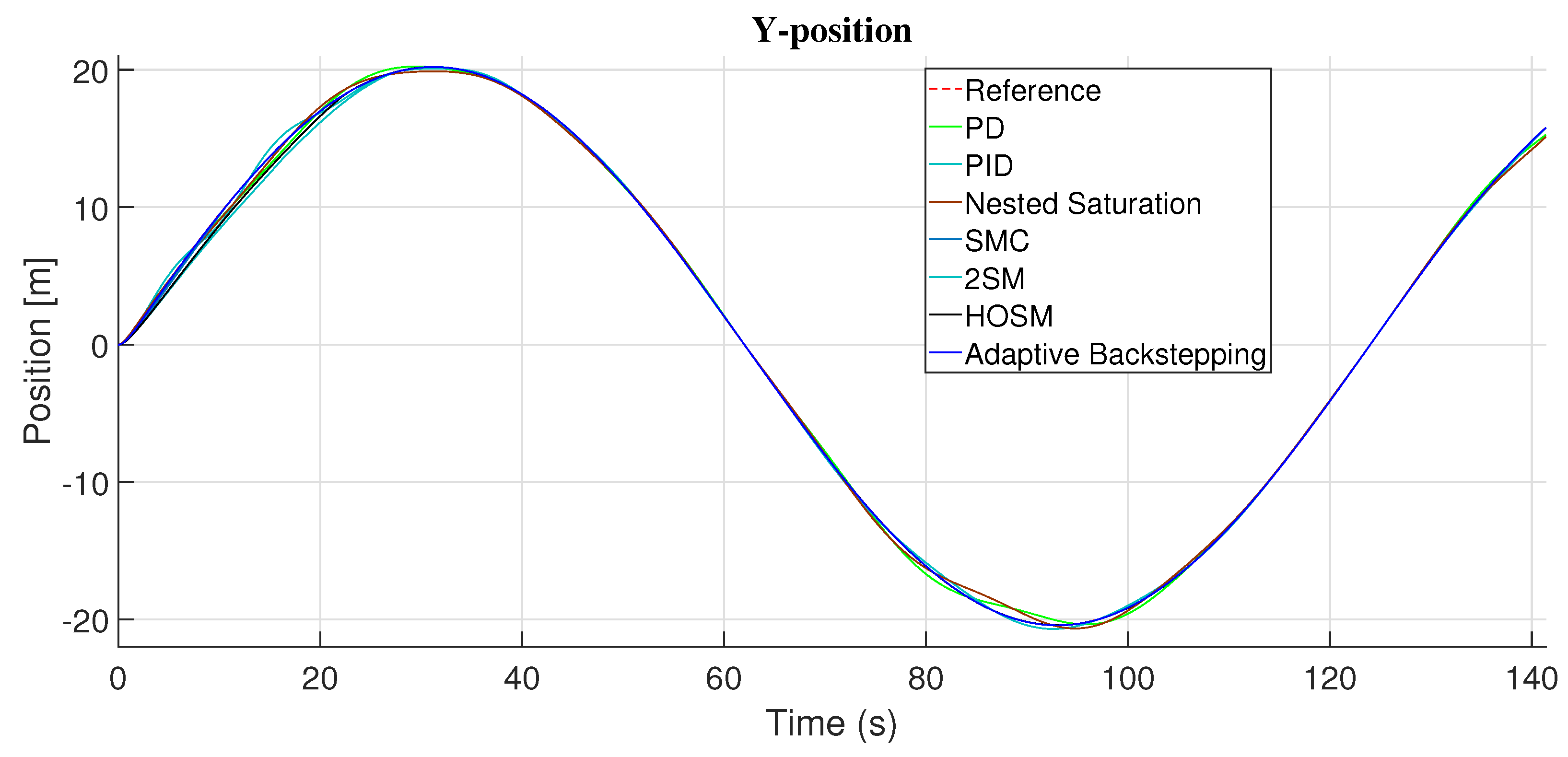

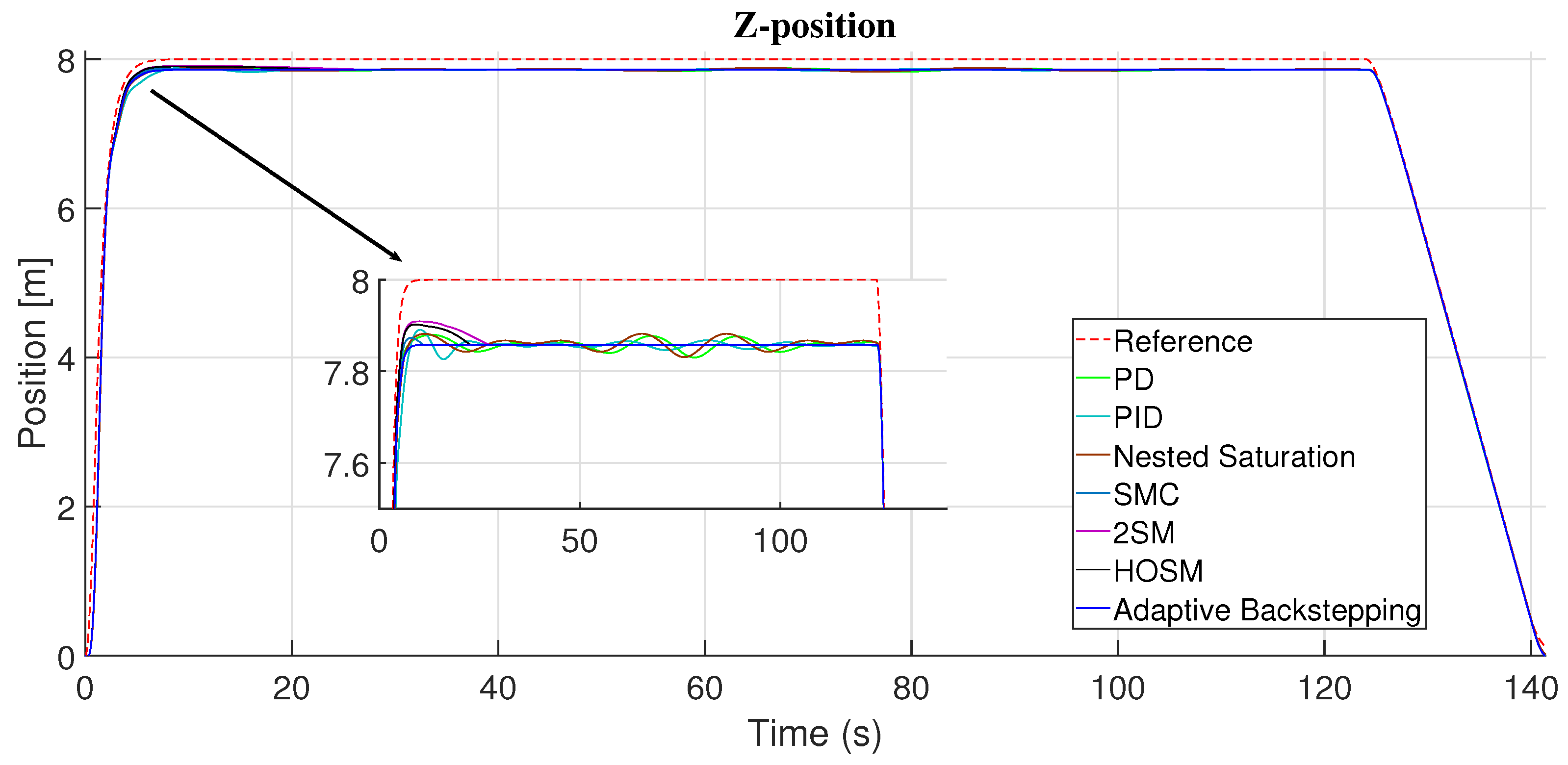

4.3. Trajectory Follow by the Coaxial-Rotor MAV

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAV | Mini Aerial Vehicle |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| SO(3) | Special Orthogonal Group in 3D |

| PD | Proportional-Derivative |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| 2SM | Second-order Sliding Mode |

| HOSM | High Order Sliding Mode |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Prior S.; Bell C. Empirical Measurements of Small Aerial Co-Axial Rotor Systems, Journal of Science and Innovation, Vol. 1, Issue. 1 pp. 1-18, 2011.

- Ramesh P.; Jeyan J. Hover Performance Analysis of Coaxial Mini Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Applications in Mountain Terrain, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University-Aviation, Vol. 26, Issue. 2 pp. 1-12, 2022.

- Li K.; Wei Y.; Wang W.; Deng H. Longitudinal Attitude Control Decoupling Algorithm Based on the Fuzzy Sliding Mode of a Coaxial-Rotor UAV, MDPI Electronics, Vol. 8, Issue. 1 pp. 1-16, 2019.

- Wei Y.; Chen H.; Li K.; Deng H.; Li D. Research on the Control Algorithm of Coaxial Rotor Aircraft based on Sliding Mode and PID, MDPI Electronics, Vol. 8, Issue. 12 pp. 1-19, 2019.

- Singh V.; Kanani A.; Panchal N.; Mathur H. Dynamic Analysis of Coaxial Rotor Systems, International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development, Vol. 10, Issue. 3 pp. 1-13, 2020.

- Wei Y.; Deng H.; Pan Z.; Li k.; Chen H. Research on a Combinatorial Control Method for Coaxial Rotor Aircraft Based on Sliding Mode, Elsevier Defence Technology, Vol. 18, pp. 280-292, 2022.

- Xu C.; Su C. Dynamic Observer-based H-infinity Robust Control for a Ducted Coaxial-rotor UAV, IET Control Theory and Applications, Vol. 16, pp. 1165-1181, 2022.

- Koehl A.; Rafaralahy H.; Boutayeb M.; Martinez B. Aerodynamic Modelling and Experimental Identification of a Coaxial-Rotor UAV, Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems, Vol. 68, pp. 53-68, 2020.

- Denton H.; Benedict M.; Kang H. Design, development, and flight testing of a tube-launched coaxial-rotor based micro air vehicle, International Journal of Micro Air Vehicles, Vol. 14, pp. 1-12, 2022.

- Chen L.; Xiao J.; Zheng Y.; Alagappan N.; Feroskhan M. Design, Modeling, and Control of a Coaxial Drone, IEEE Transactions on Robotics, Vol. 40, pp. 1650-1663, 2024.

- Xu J.; Hao Y.; Wang J.; Li L. The Control Algorithm and Experimentation of Coaxial Rotor Aircraft Trajectory Tracking Based on Backstepping Sliding Mode, MDPI Aerospace, Vol. 8, Issue. 11 pp. 1-17, 2021.

- Glida H.; Chelihi A.; Abdou L.; Sentouh C.; Perozzi G. Trajectory Tracking Control of a Coaxial Rotor Drone: Time-delay Estimation-based Optimal Model-free Fuzzy Logic Approach, ISA Transactions, Vol. 137, pp. 1-13, 2023.

- Goldstein H.; Poole C.; and Safko J. Classical Mechanics, Adison-Wesley, USA, 1983.

- Castillo P.; Lozano R.; Dzul A. Modelling and Control of Mini-Flying Machines, Ed. Springer, London, 2005.

- Garcia L.; Dzul A.; Lozano R.; Pégard A. Quad Rotorcraft Control:Vision-Based Hovering and Navigation, Ed. Springer-Verlag, London, 2013.

- O’Reilly O.M. Intermediate Dynamics for Engineers, Ed. Cambridge University Press, UK, 2020.

- Ardema M.D. Newton-Euler Dynamics, Ed. Springer, USA, 2005.

- Craig J.J. Introduction to Robotics Mechanics and Control, Ed. Pearson Education International, third edition, USA, 2005.

- Stengel R. F. Flight Dynamics, Princeton University Press, USA, 2004.

- Cook M. Flight Dynamics Principles, Ed. Elsevier,Second edition, 2007.

- Stevens B.; Lewis F.; Johnson E. Aircraft Control and Simulation, Ed. Jhon Wiley and Sons, third edition, USA, 2015.

- Mclean D. Automatic Flight Control Systems, Ed. Prentice hall International, USA, 1990.

- Espinoza-Fraire T.; Dzul A.; Parada R.; Sáenz A. Design of Control Laws and State Observers for Fixed-WIng UAVs: Simulation and Experimental Approaches, Ed. Elsevier, UK, 2023.

- Kelly R.; Santibañez V.; Loría L. Control of Robot Manipulators in Joint Space, Ed. Springer, USA, 2005.

- Ogata K. Modern Control Engineering, Ed. Prentice Hall, Fifth edition, New Jersey, 2009.

- Teel A. Global stabilization and restricted tracking for multiple integrators with bounded controls, Systems and Control Letters, Vol. 18, Issue 3, pp. 165-171, 1992.

- Khalil H. Nonlinear Systems, Prentice Hall, third Edition, USA, 1995.

- Shtessel Y.; Edwards C.; Fridman L.; Levant A.; Sliding Mode Control and Observation, Birkhäuser, New York, 2015.

- Levant A. Robust exact differentition via sliding mode technique, Automatica, Vol. 34, Issue 3, pp. 379-384, 1998.

- Levant A. Construction principles of 2-sliding mode design, Automatica, Vol. 43, Issue 4, pp. 576-586, 2007.

- Levant A. Higher-order sliding modes, differentiation and output-feedback control, International Journal of Control, Vol. 76, Issue 9-10, pp. 924-941 , 2003.

- Åström K.; Wittenmark B. Adaptive Control, Ed. Prentice Hall, 2nd Edition, 1994.

- Kristić M.; Kanellakopoulos I.; Kokotović P. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design, Ed. John Wiley and Sons, USA, 1995.

- Wang W.; Wen C.; Zhou J. Adaptive Backstepping Control of Uncertain Systems with Actuator Failures, Subsystem Interactions, and Nonsmooth Nonlinearities, Ed. CRC Press, UK, 2017.

| Roll Angle() | ||

|---|---|---|

| PD | 2.2186 | 1.6902 |

| PID | 2.1366 | 1.6902 |

| Nested Saturation | 1.9771 | 1.7372 |

| Sliding Mode | 2.9122 | 11.8892 |

| Second-order Sliding Mode | 4.9947 | 6.2838 |

| High-Order Sliding Mode | 4.4072 | 5.6993 |

| Adaptive Backstepping | 1.5271 | 1.7194 |

| Pitch Angle() | ||

|---|---|---|

| PD | 2.0078 | 1.6830 |

| PID | 2.6340 | 1.6826 |

| Nested Saturation | 1.2741 | 1.7097 |

| Sliding Mode | 0.9995 | 12.1660 |

| Second-order Sliding Mode | 1.5125 | 6.3147 |

| High-Order Sliding Mode | 1.3462 | 5.9203 |

| Adaptive Backstepping | 0.7598 | 1.6931 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).