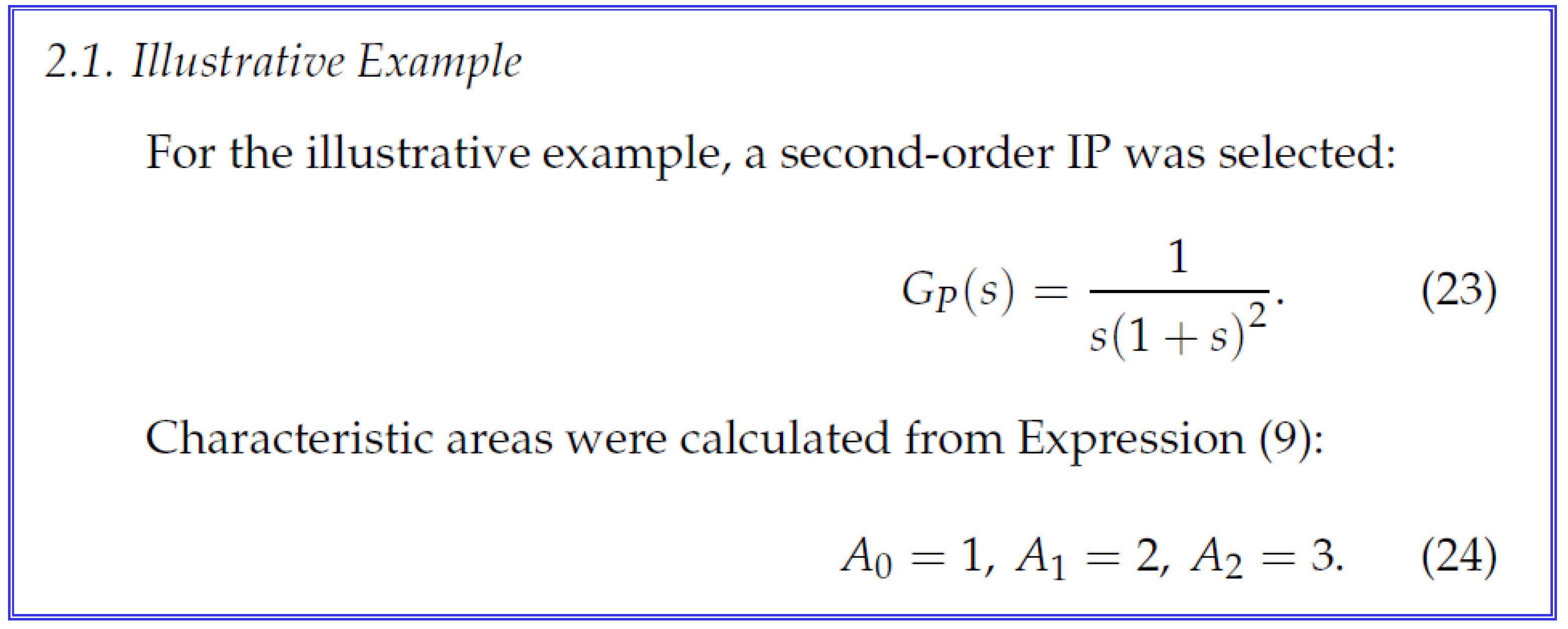

Application A

We will show that some optimization problems have no solution, although the calculation of the regulator for such objects can be carried out quite simply. We will also show that for these reasons the mathematical model of the object, which does not contain a pure delay link, is always insufficiently complete.

Let’s show this theoretically first. Let’s take a simple first-order link.

It is described by the following transfer function:

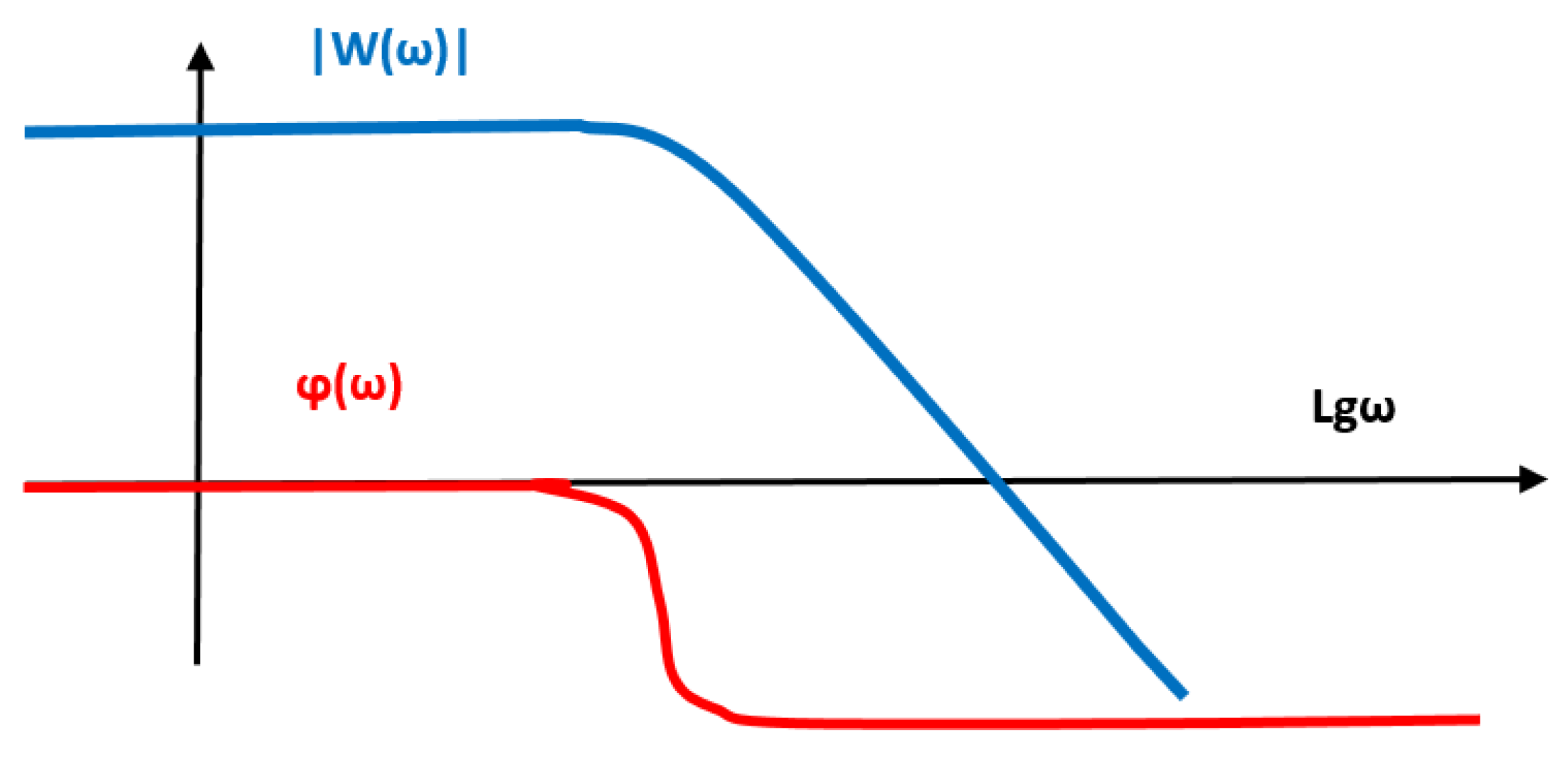

For this transfer function, the amplitude-frequency response and the phase -frequency response can be plotted as

Figure A1 shows.

The stability criterion of a loxked linear dynamic Nyquist-Mikhailov system requires that in the frequency range where the logarithmic amplitude-frequency function of the open circuit is greater than zero, the phase -frequency characteristic remains within the limits of not less than

, i.e. in absolute value it does not exceed.

On the graph shown in

Figure A1, the phase -frequency characteristic asymptotically tends to the value

. Thus, in the entire frequency range, including infinite frequencies, the phase-frequency characteristic does not exceed in absolute value even half the critical value. Consequently, for any arrangement of the amplitude-frequency characteristic, a system with such a phase-frequency characteristic will remain stable. With an increase in the gain of such a system, the amplitude-frequency characteristic will rise up along the ordinate axis. Since its right side is often an infinite beam with a constant slope

, then with an increase in the gain of the circuit, the operating frequency band of the system will proportionally increase, and the gain at each frequency will also proportionally increase. Such a system will become better and better with an increase in the gain, it will never become worse because the gain in it is increased in comparison with the previous value.

Thus, it turns out that the theoretical model of an object in the form of a transfer function (A1) has the following property: a system with such an object and a sequential proportional controller is better the greater the gain coefficient, and for this value there is no limit after which its increase would not give a positive effect, consisting in increasing the accuracy and expanding the band of the resulting system.

No real object with a proportional controller has such a property. With any real object, any controller, including a proportional one, or even a PID controller, always does not allow any coefficient or the overall transfer coefficient to be increased infinitely. Therefore, with any real object, there is an optimal value or at least some area of optimal values of the coefficients, such that not only a decrease in these coefficients, but also their increase will lead to deterioration of the system’s operation. This, as a rule, manifests itself in a violation of the stability of the system.

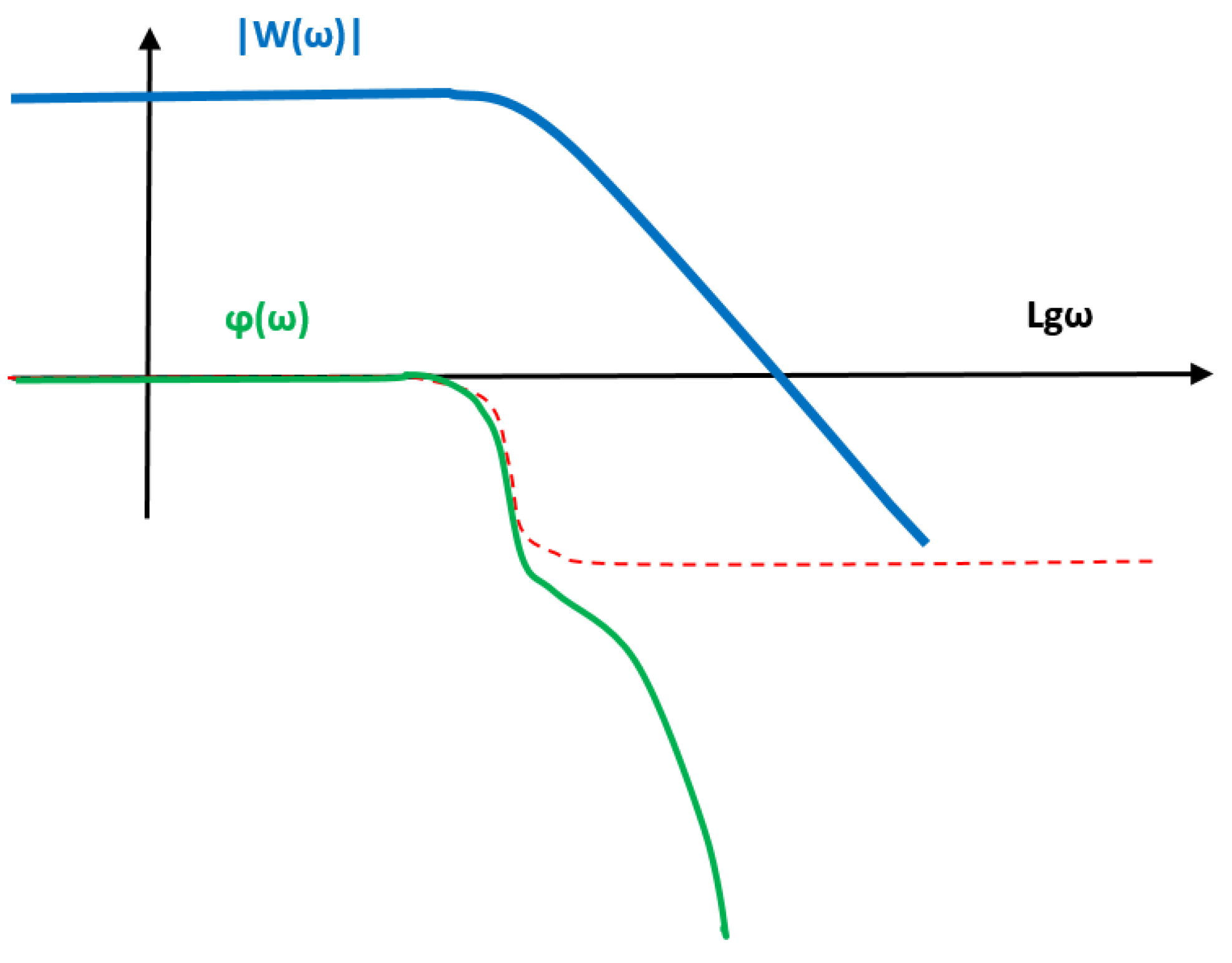

If we take into account the delay link in the object model, then the object model will be described by the following transfer function

In this case, the amplitude-frequency characteristic graph will not change, but the phase-frequency characteristic graph will change dramatically, as shown in the figure below, which will be fatal for the stability of the system. Both graphs together will look like

Figure A2.

For the situation in

Figure A2, the reasoning given on the basis of the situation in

Figure B1 is no longer applicable. The phase-frequency characteristic increases linearly with increasing frequency, and since the frequency axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale, the phase graph increases exponentially in magnitude with increasing frequency logarithm, while remaining negative. The phase delay value in absolute value reaches and exceeds the value

quite quickly with increasing frequency. The frequency at which the phase delay is equal to

is the limiting frequency to which the frequency band of the closed system can be expanded. It is possible to locally reduce the phase shift value by using differentiation, but this does not solve the problem radically; this limiting point will only shift slightly to the left along the frequency axis.

On this basis, it can be argued that mathematical results obtained for objects without taking into account the delay are abstract mathematical results. For this reason, no model of an object in which there is a delay link, even if the delay value is very small, will ever have the property discussed above. A system with a proportional controller will never be stable in the entire range of gain coefficients of this controller. The same can be said about an object with a delay relative to any type of controller.

If we consider the model of a second-order object without delay, then the above-mentioned property of maintaining stability with an arbitrarily large gain coefficient of the locked loop will take place for the case of a PID controller, since ideal derivation reduces the phase shift of the loop in absolute value by

, as a result of which the phase-frequency characteristic of a series-connected derivative link and a second-order object in the high-frequency region will be the same as shown in

Figure B1.

Thus, we see that there are problems that do not have an optimal solution, since for any specific solution it is always possible to specify a better solution that has a higher gain value. We also see that this situation takes place only in theory when using a simplified model that has no delay. In practice, any object has a delay due to the signal propagation in it. Even if we take the fastest of all known control objects today, for example, a microwave transistor, it also has a delay, since the electrical signal propagates in conductors (and in semiconductors too) at a speed that does not exceed the speed of light in a vacuum. Even if the dimensions of the waveguide in the transistor are only 1 cm, then in this case it will give a delay of 33 ps. Thus, we have no right to use mathematical models of controlled objects without a delay. And since analytical methods, as a rule, neglect the delay, they have no applied value. Apparently, the delay can be neglected only if the minimum phase frequency of the object model is a model of the third or higher order, and the delay value is so small that the delay begins to affect the actual value of the phase characteristic only starting from those frequencies at which this characteristic in absolute value already significantly exceeds the value . The publications we have reviewed, where the delay is neglected, as a rule, do not fall under this reservation.

The experimental proof of this is as follows. You can take a model of a first-order object (B1), then create a project for modeling and optimizing a proportional controller for it. The optimization will end with some solution, but you can easily verify that the reason for stopping the optimization procedure was that the modeled system reached the required value in one or two time sampling steps. If you then decrease the time sampling step, for example, by 20 times and continue the optimization procedure from the started value, a new value of the “optimal” coefficient of the proportional controller will be found, and with this new value the cost function will decrease significantly (approximately by 20 times). This can be done ad infinitum. Thus, the stop factor for the optimization problem is a delay in the modeled system by a value equal to several time sampling steps. We will not provide the results of modeling this problem, since they can easily be obtained by any user who doubts this, which will be more convincing evidence of the described situation.

The conclusion to be drawn from this section is as follows. As a rule, any mathematical model of any controlled object is known only approximately and only in a limited frequency band. Starting from some fairly high frequencies (in comparison with the frequencies characteristic of this object, where its transfer function changes most rapidly), a mathematical model of the object cannot be constructed based on experimental data, since in this frequency range there are simply no experimental data, or they are negligibly small in comparison with the measurement noise. Therefore, engineers create a mathematical model of the object based on the requirement that it should match its characteristics as accurately as possible with those obtained experimentally. Therefore, the task of matching the high-frequency properties of this model with its actual properties is simply not set.

However, the following paradox arises. In the absence of information on how the model behaves in the region of the highest frequencies, engineers refuse to make a clarifying addition, that is, they choose the simplest model of all the models that correspond to the experimental graphs of the object’s responses to test effects. But the simplest model is the most unrealistic, it corresponds to the truth to the least extent. Adding a low-pass filter with a very small time constant, as well as adding a delay link with a very small delay value, does not affect the response in the region of low and medium frequencies. Therefore, such an addition is not made. But the problem is that without such an addition, the object becomes unrealistically ideal, and the theory of control of such an object provides opportunities for expanding the frequency band and increasing accuracy much more than is the case in practice. It turns out that if we cannot measure the properties of the object in the region of these high frequencies, we, due to the simplification of the model, assume the best possible and even impossible properties. Whereas in fact, in the region that cannot be studied, we should assume the worst properties of all possible. In this case, our model, when used to design a regulator, would give the most reliable results in theory and numerical modeling, which are fully confirmed when these results are used in practice.

The simplest and, in our opinion, obligatory way to assume the worst properties of an object in the frequency range that has not been studied experimentally is to introduce a delay link into the object model by a value small enough that this delay does not manifest itself in any way when identifying the object model. This addition immediately turns the object into a realizable one that has all the necessary properties of a real object.

There is one additional motive for this approach. It is that if the designer erroneously assumed during modeling and optimization that the object delay is greater than it actually is, the calculated controller will work no worse than it did during modeling. If, however, during optimization the designer assumed that the delay is less than it actually is, then the system with the calculated controller will in practice be worse than it was during modeling, and it may even become unstable. At the very least, the overshoot in such a system will increase in comparison with the modeling results. An exception to this rule are systems using the Smith predictor: such systems, as modeling has shown, will lose their stability both if the actual objest delay is greater than assumed and if it is less than assumed. For this reason, systems using the Smith predictor are not robust and should simply not be used if a reliable automatic control system is needed.

Application B. On the use of fictitious models and correctness

Often reviewers write that to consider and illustrate control methods we take fictitious examples that in practice do not correspond to any applied tasks, and for this reason the article should be rejected, or the authors should take some example from real practice and solve it, and only in this case the article will be of any use.

Consider the article [

29]. This article discusses a method for designing controllers based on tabular methods, the authors of which are Ziegler and Nichols, Cohen and Coon, as well as Chien, Hrones and Reswick. These authors gave the names to the corresponding tabular methods, and the publications of these authors for 1942, 1953 and 1952, respectively, are given in the review part of this article. We have already discussed the reasons why we consider tabular methods obsolete and unacceptable. Nevertheless, examples with delay in the object model are used.

As examples, objects with transfer functions of the following type are selected:

This is exactly the model that is assumed in the methods of the indicated authors, so an example of how the original methods work or their modification to solve the problem of managing such an object is not interesting and not relevant.

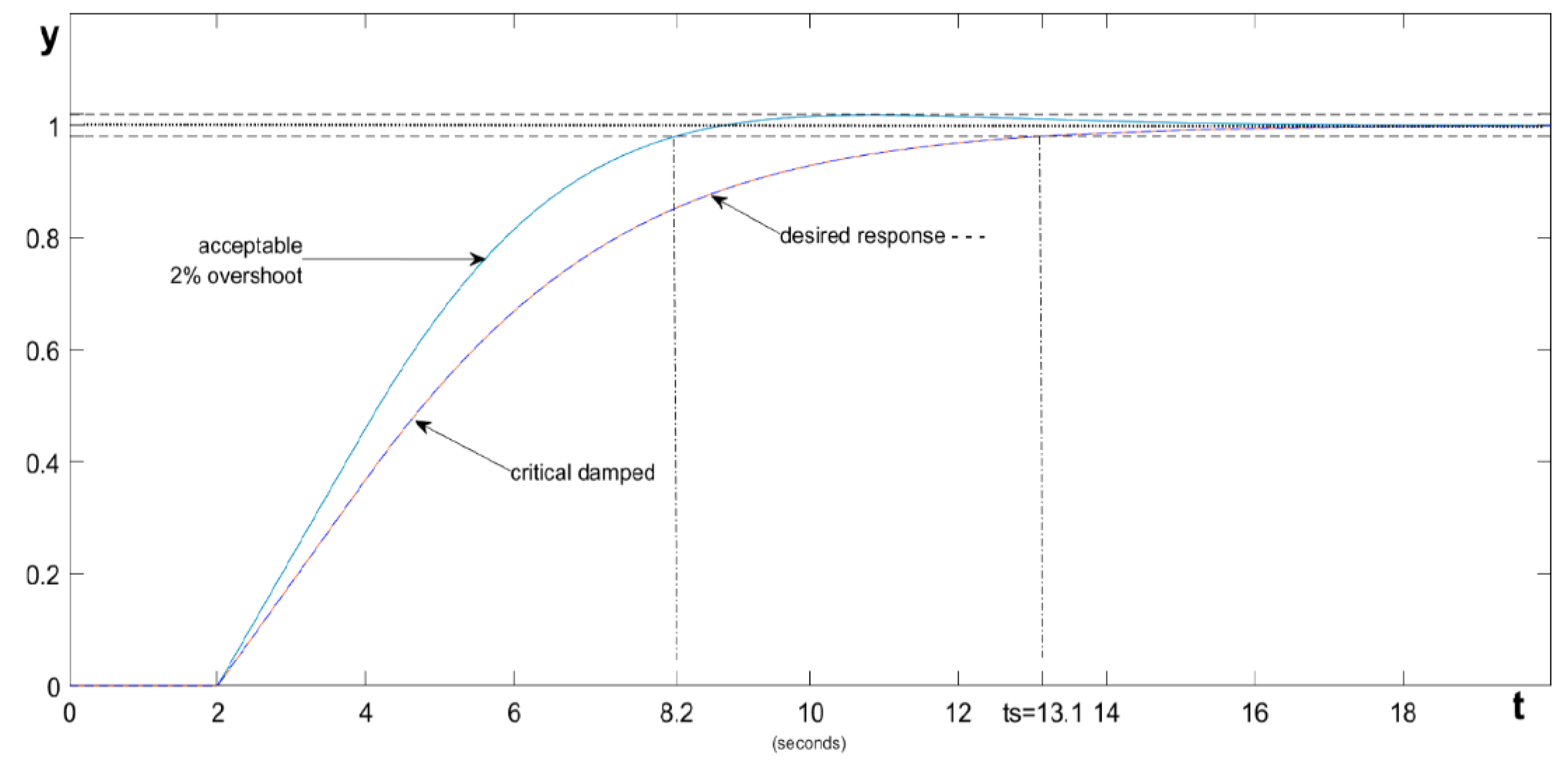

Author writes: “If we want to obtain a non-oscillatory response in the critical damped system in the shortest time possible, we have to calculate the PI controller settings based on (39) and (45), obtaining Ti = 4, Kp = 0.3679. When the model accurately reflects the object, the shortest settling time with the assumed time constant will be obtained when Kp1 = 0.4598. Then, the overshoot will remain less than 2% of the error band, and the settling time will be shortened to the estimated value of (46)”.

In this paper, the PI controller is represented by a relationship numbered as equation (6):

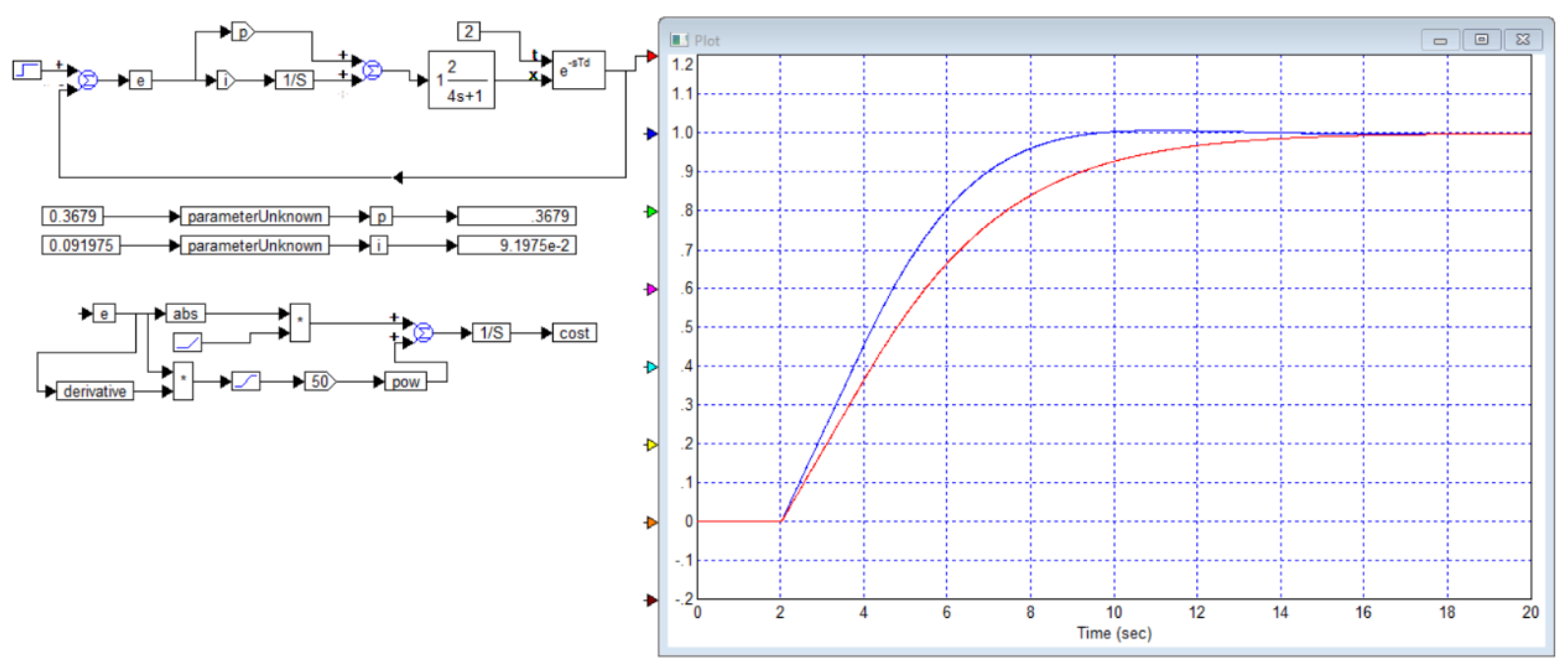

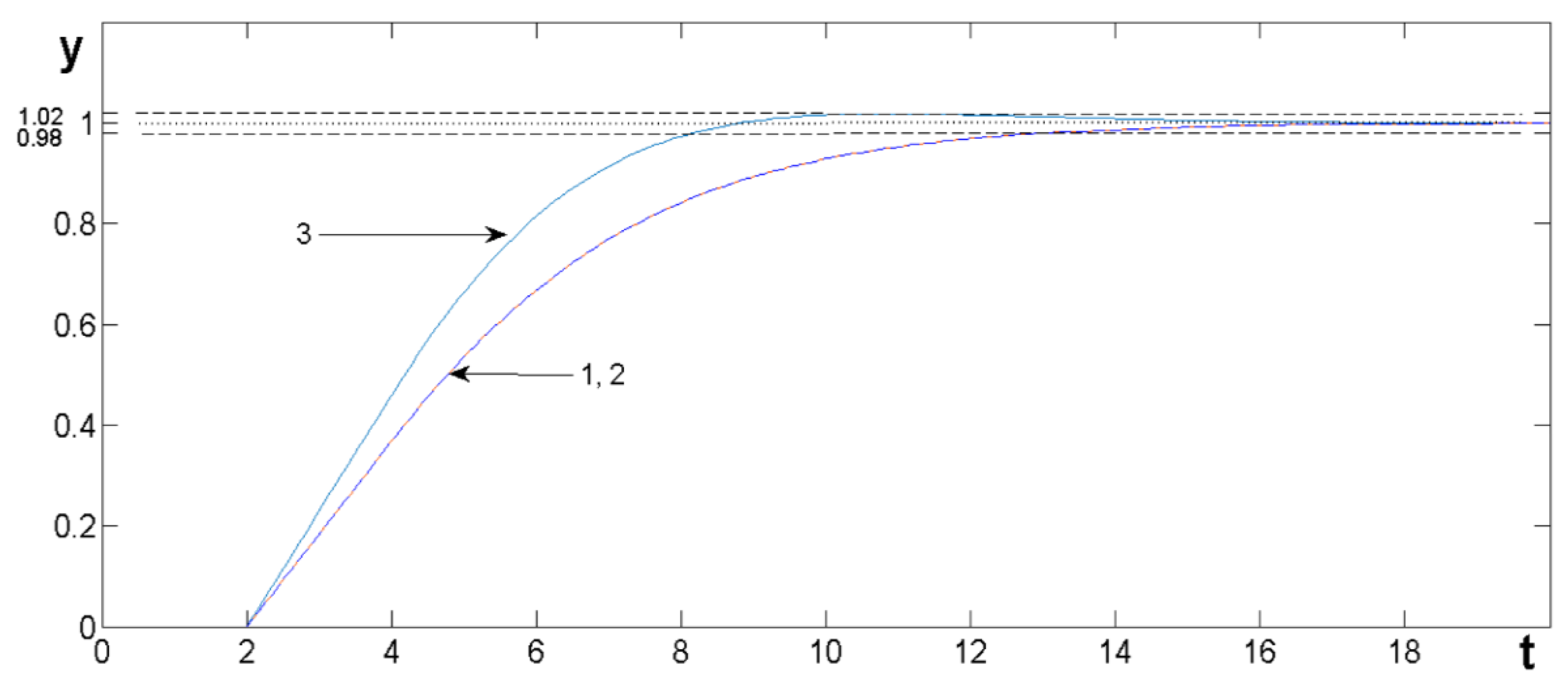

We draw the readers’ attention to the fact that in this case the model of the object is clearly fictitious, it is extremely simple, consists of a first-order filter and a delay link, and all the coefficients in this model are integers. Transient processes for the specified object (B1) and the PI controller calculated in this article (B2) are shown in

Figure B1.

Figure 1.

Graph from publication [

29] for a system consisting of an object with a transfer function of the form (B1) and a controller (B2).

Figure 1.

Graph from publication [

29] for a system consisting of an object with a transfer function of the form (B1) and a controller (B2).

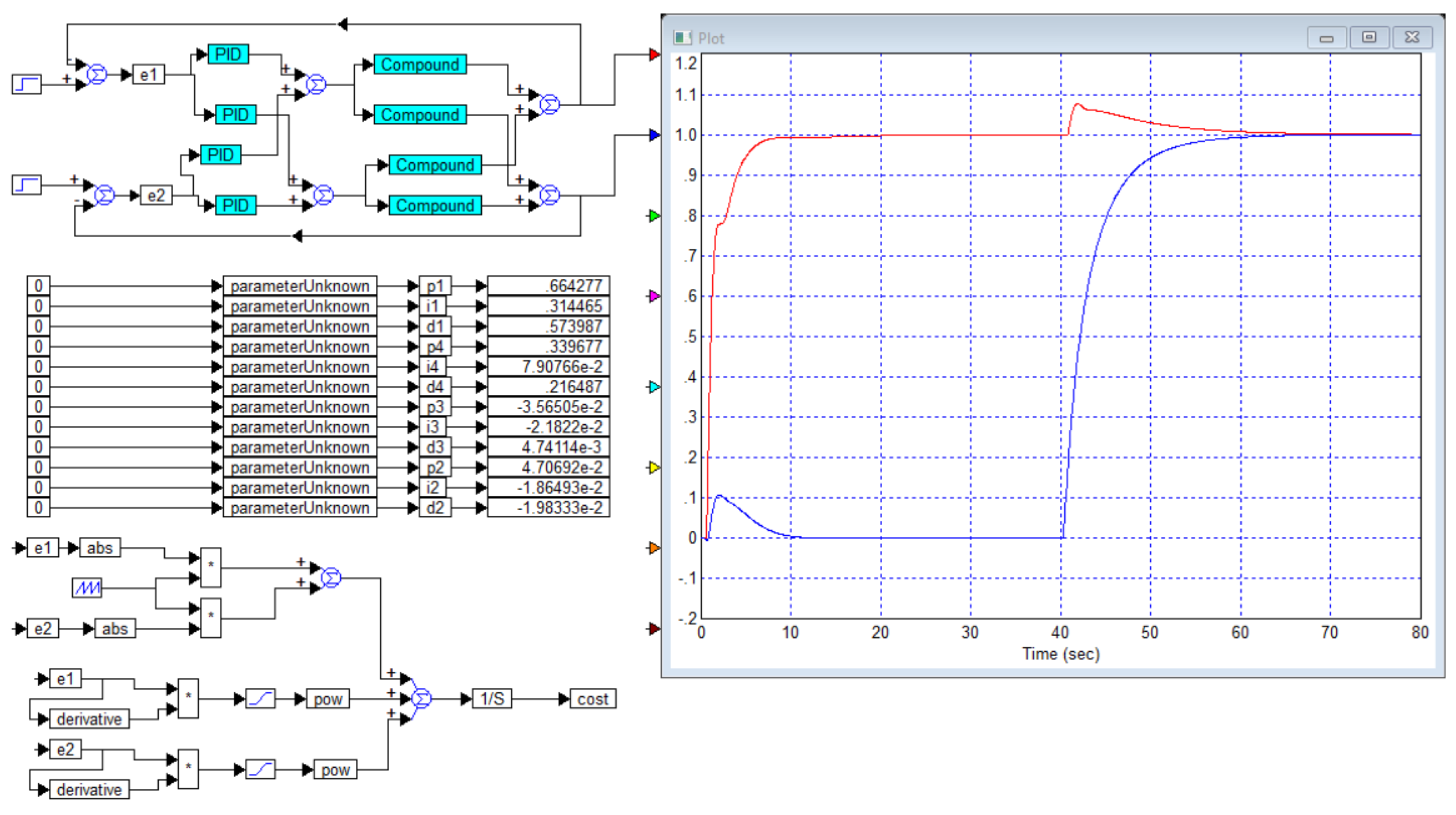

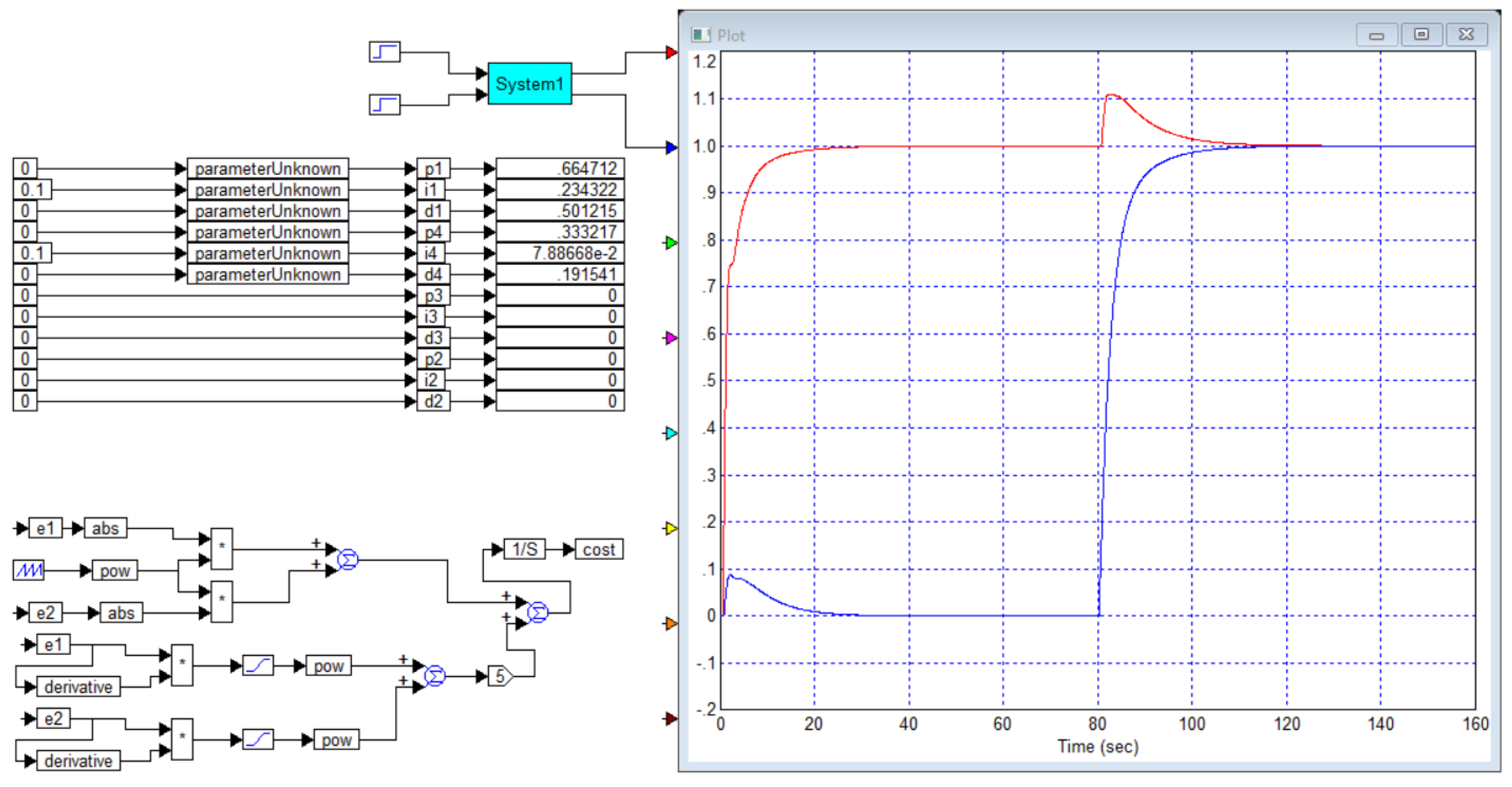

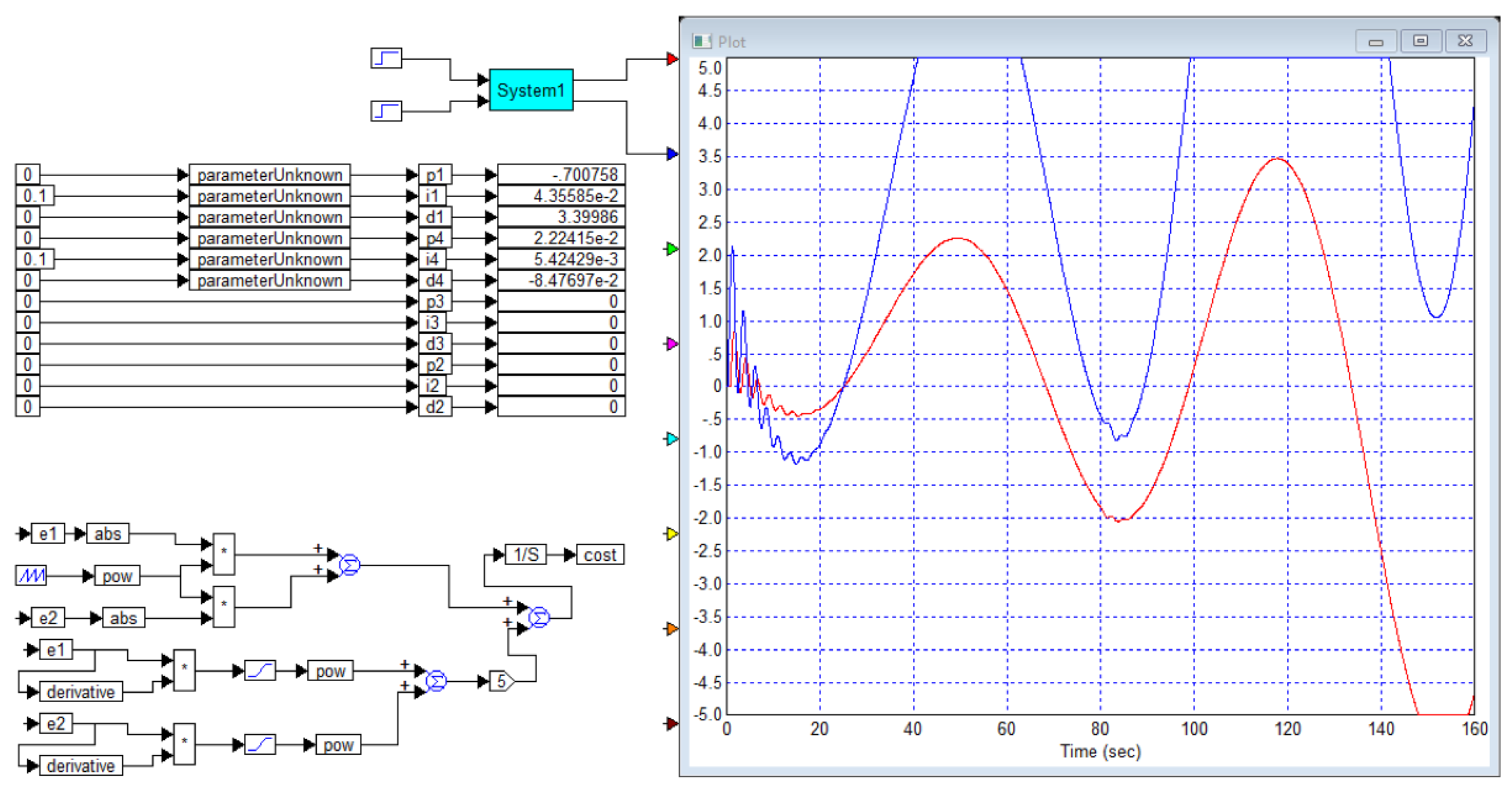

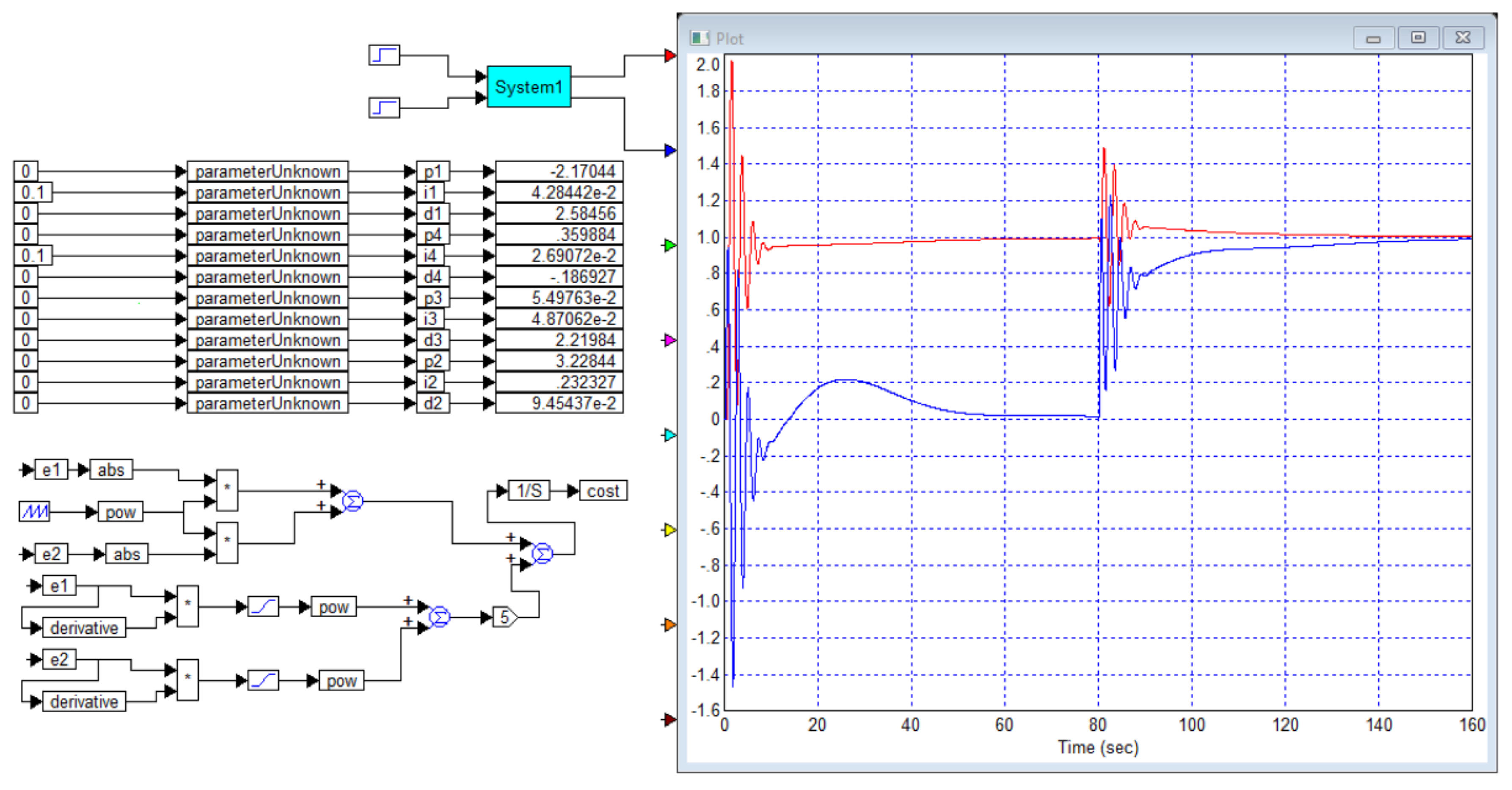

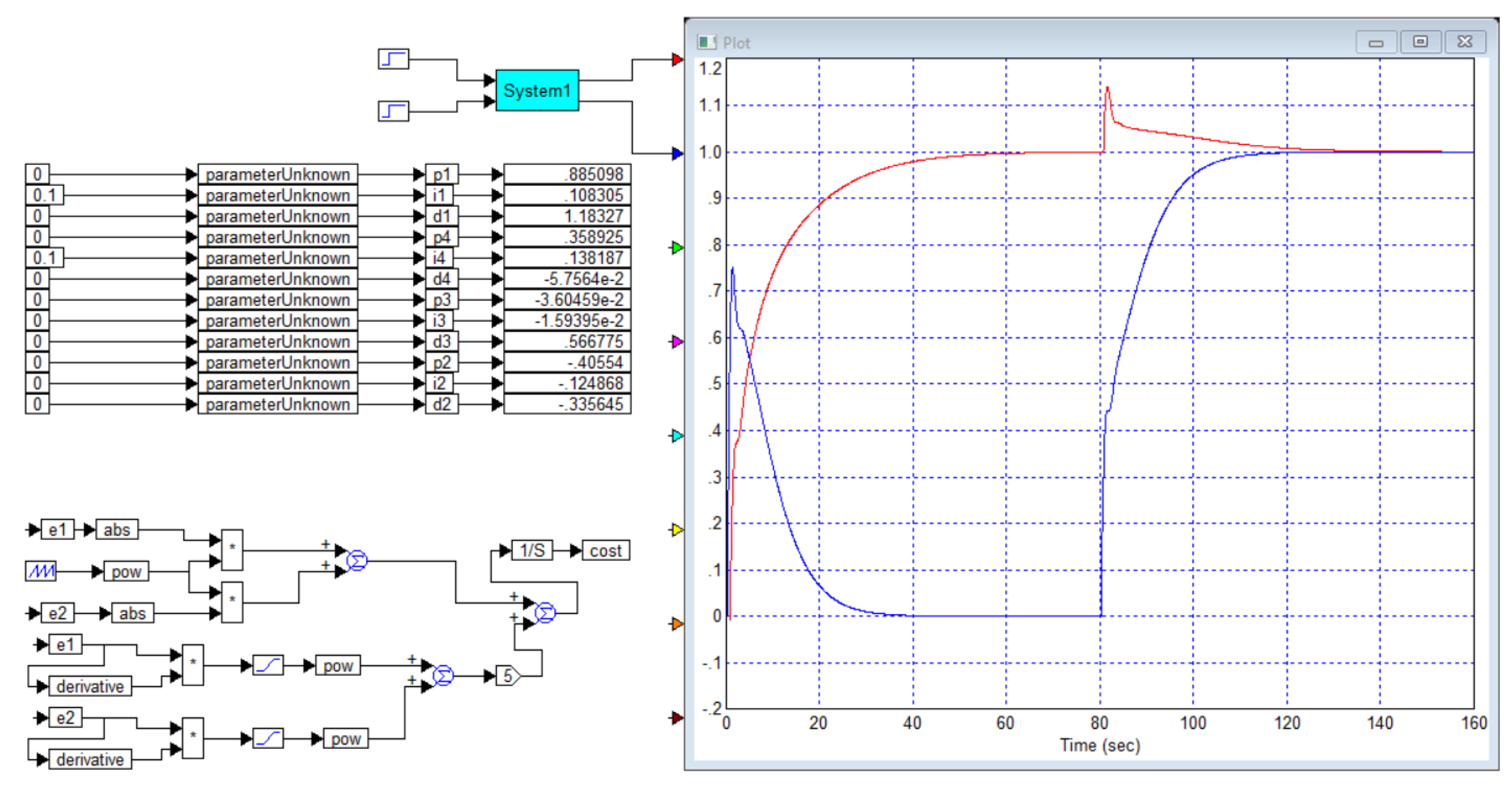

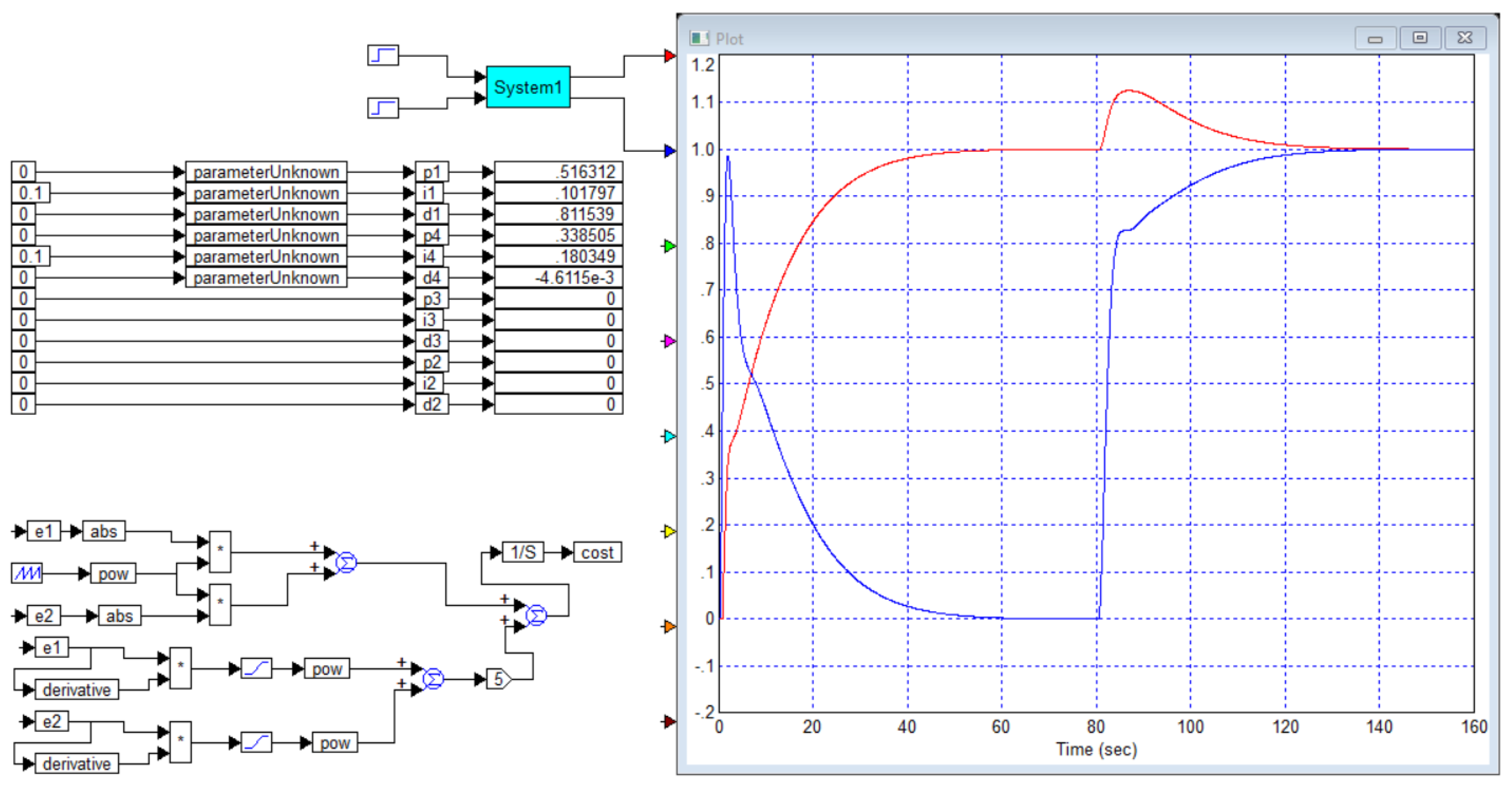

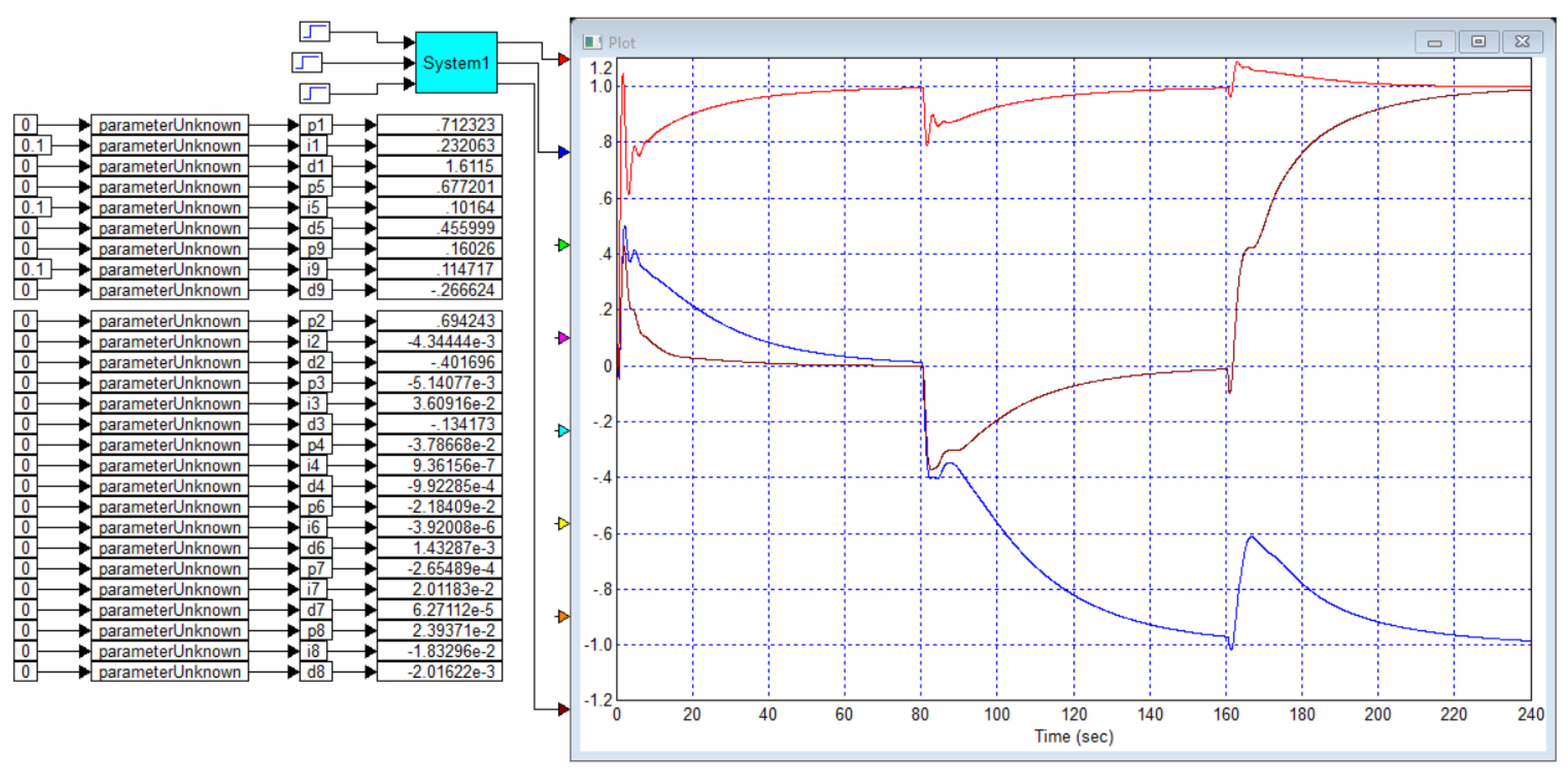

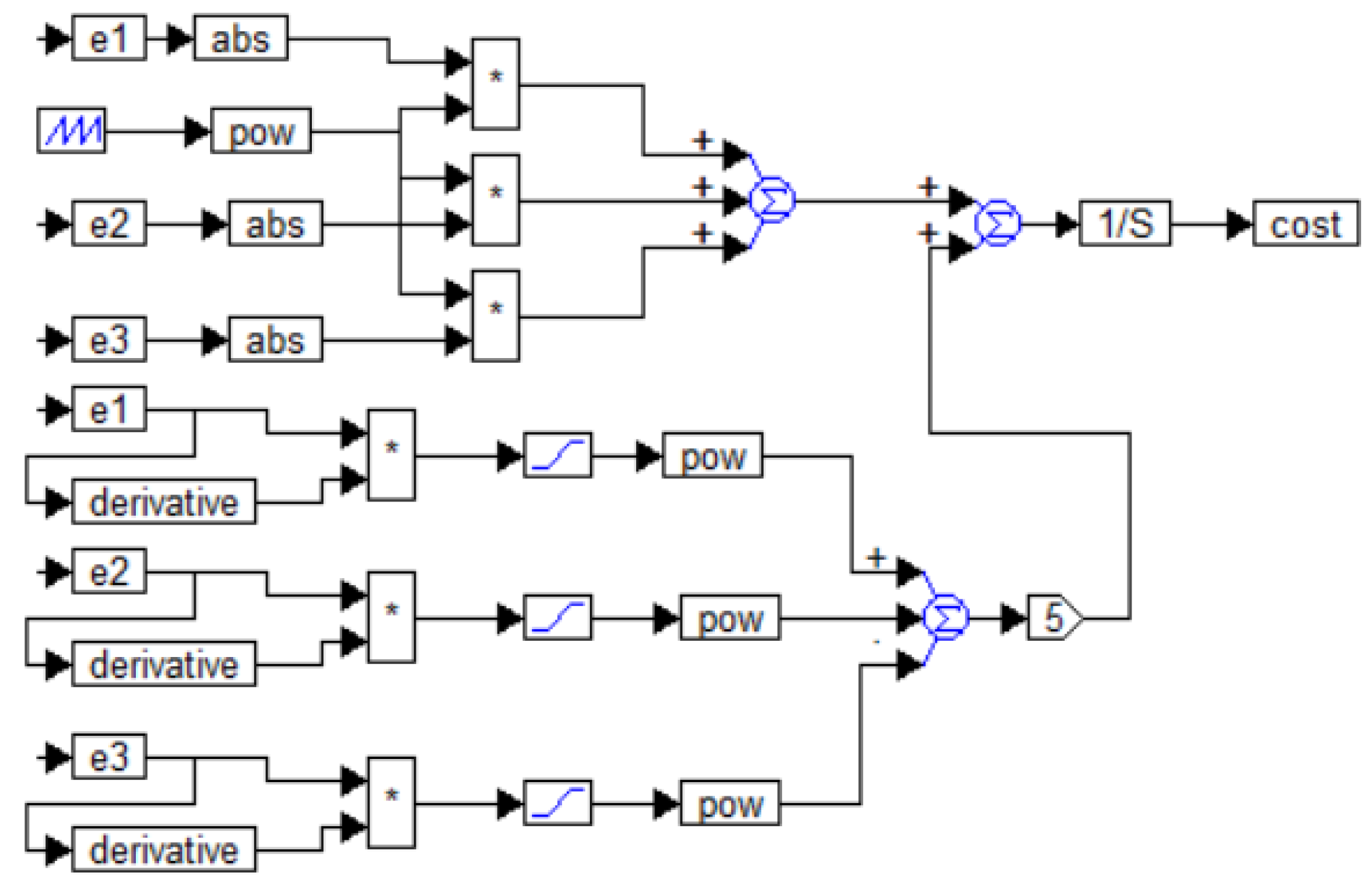

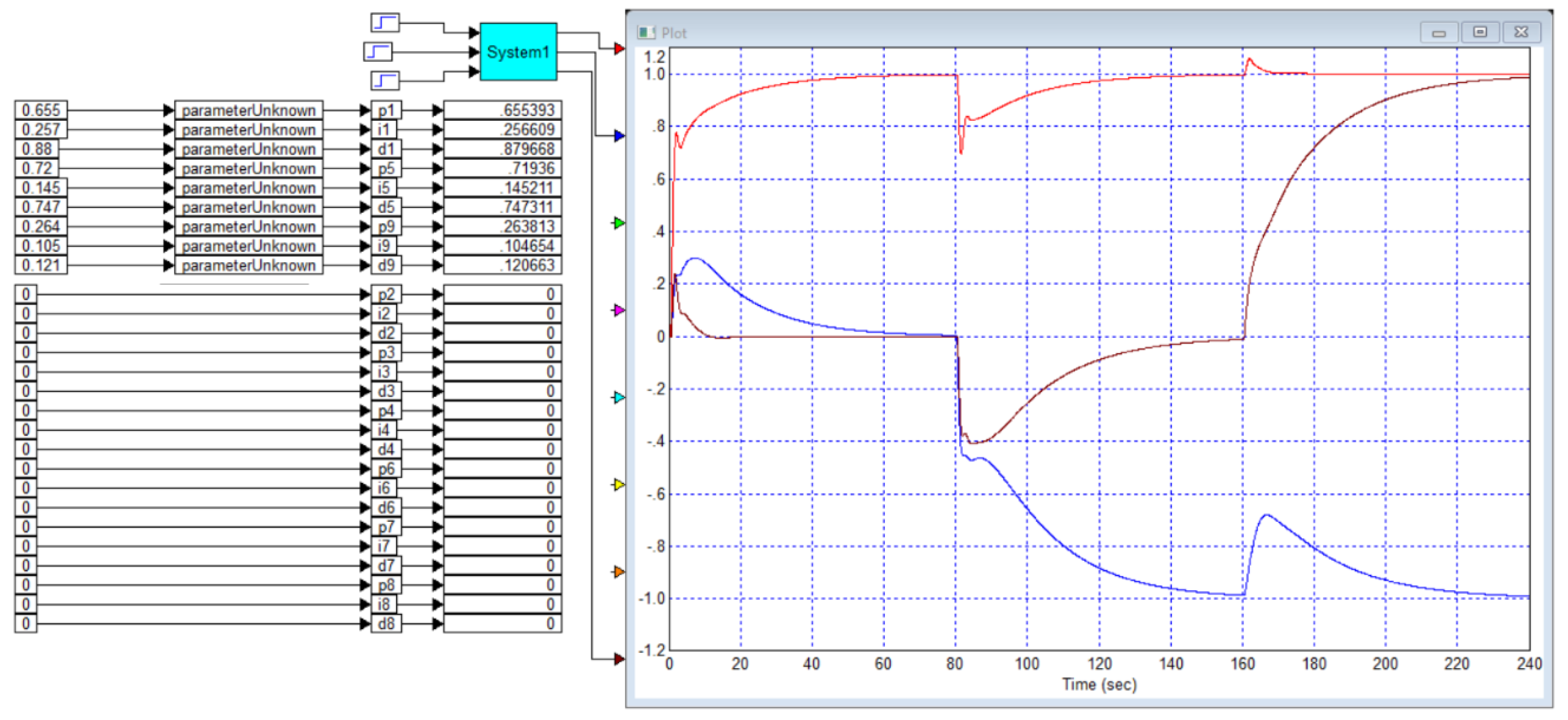

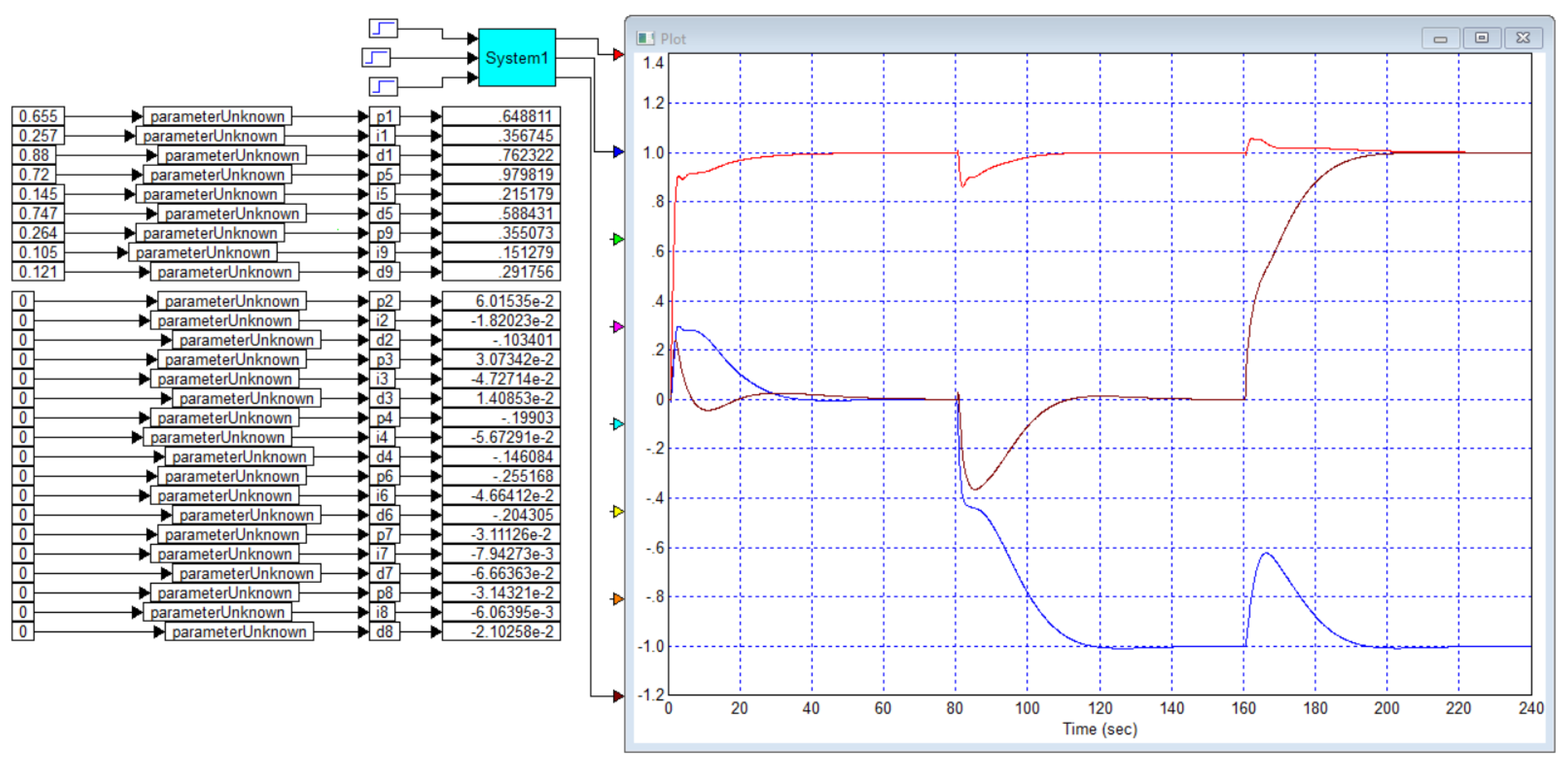

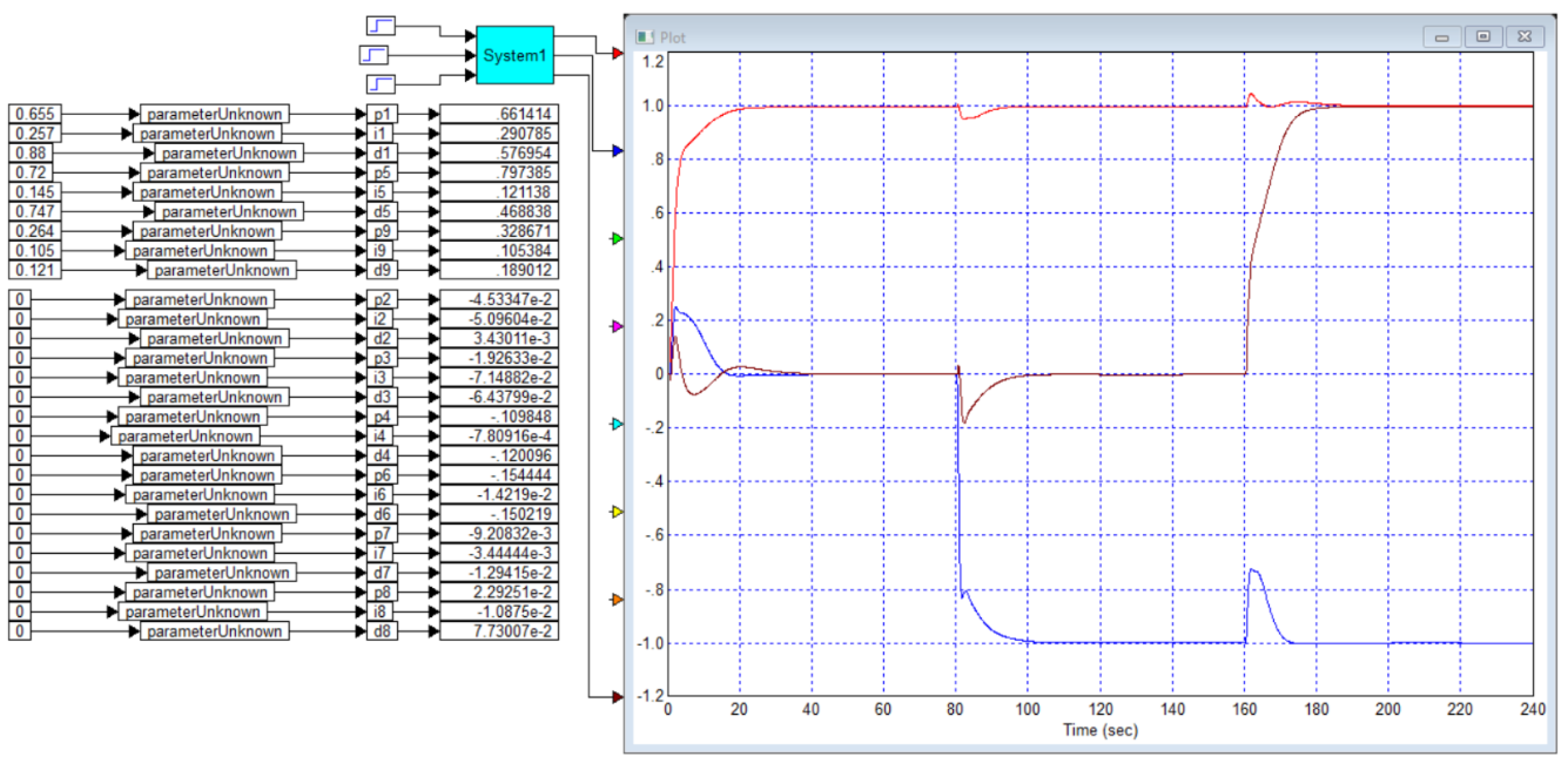

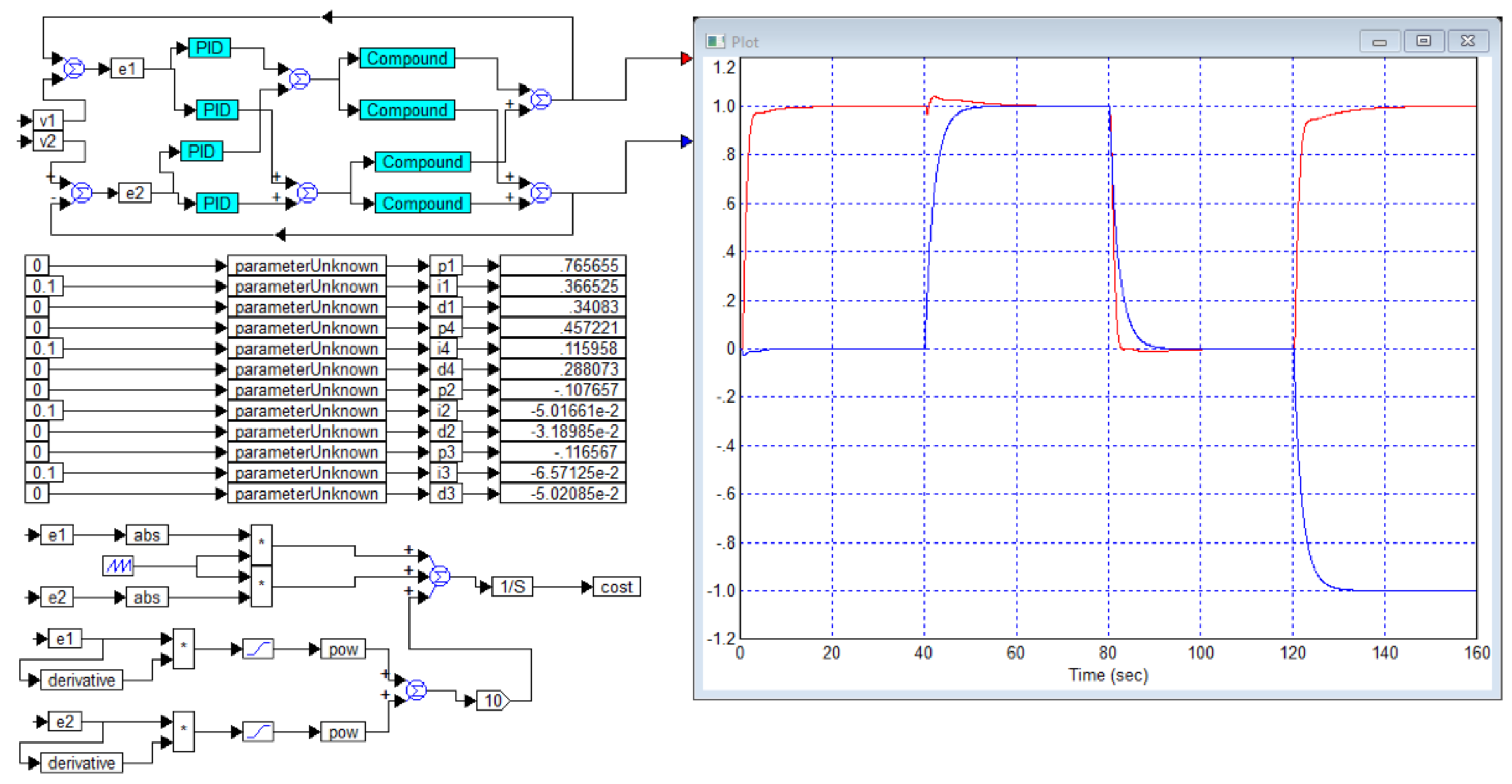

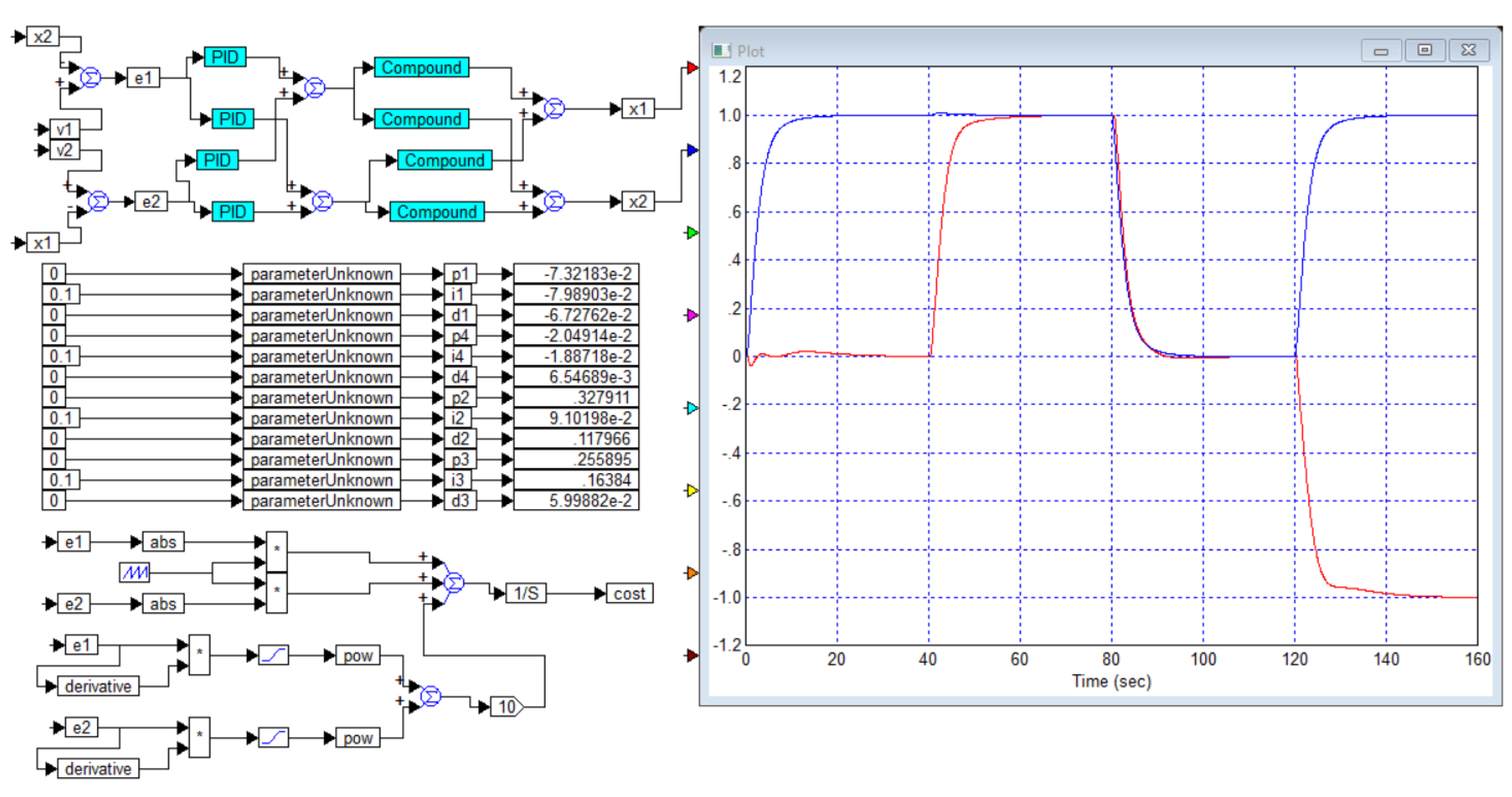

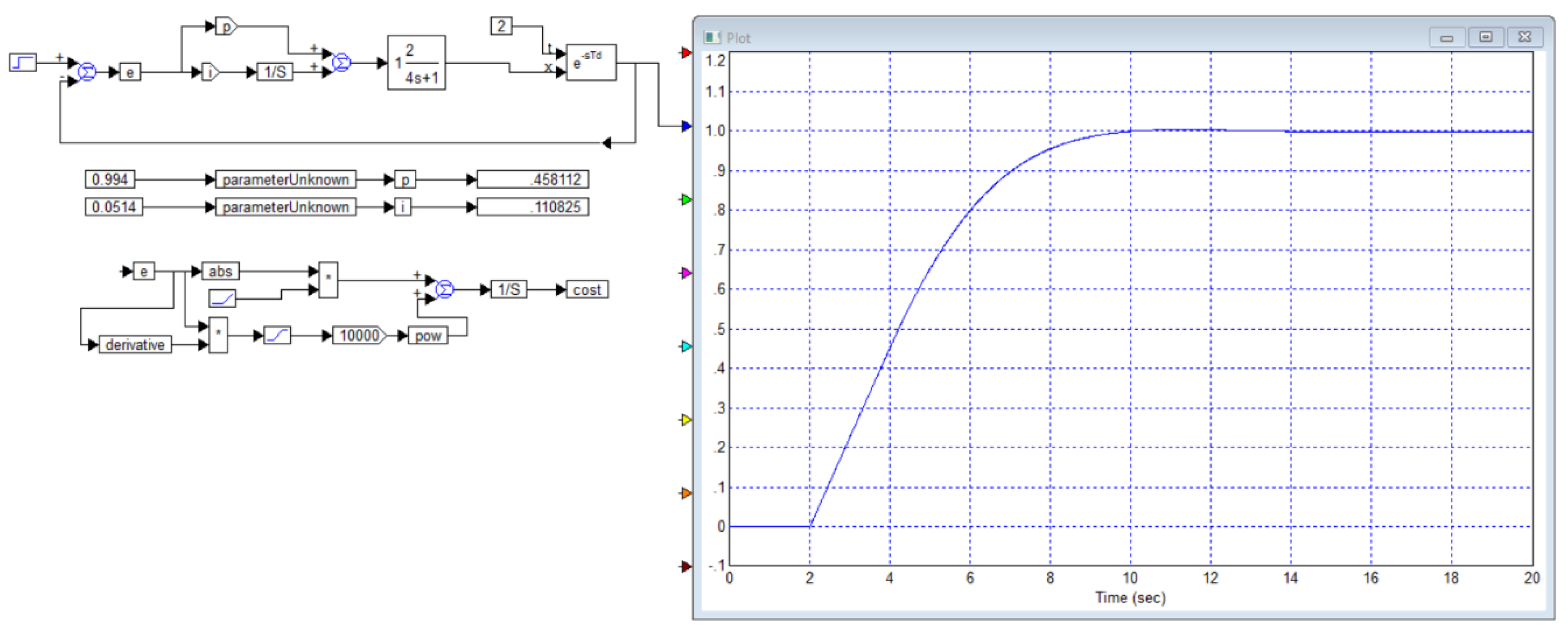

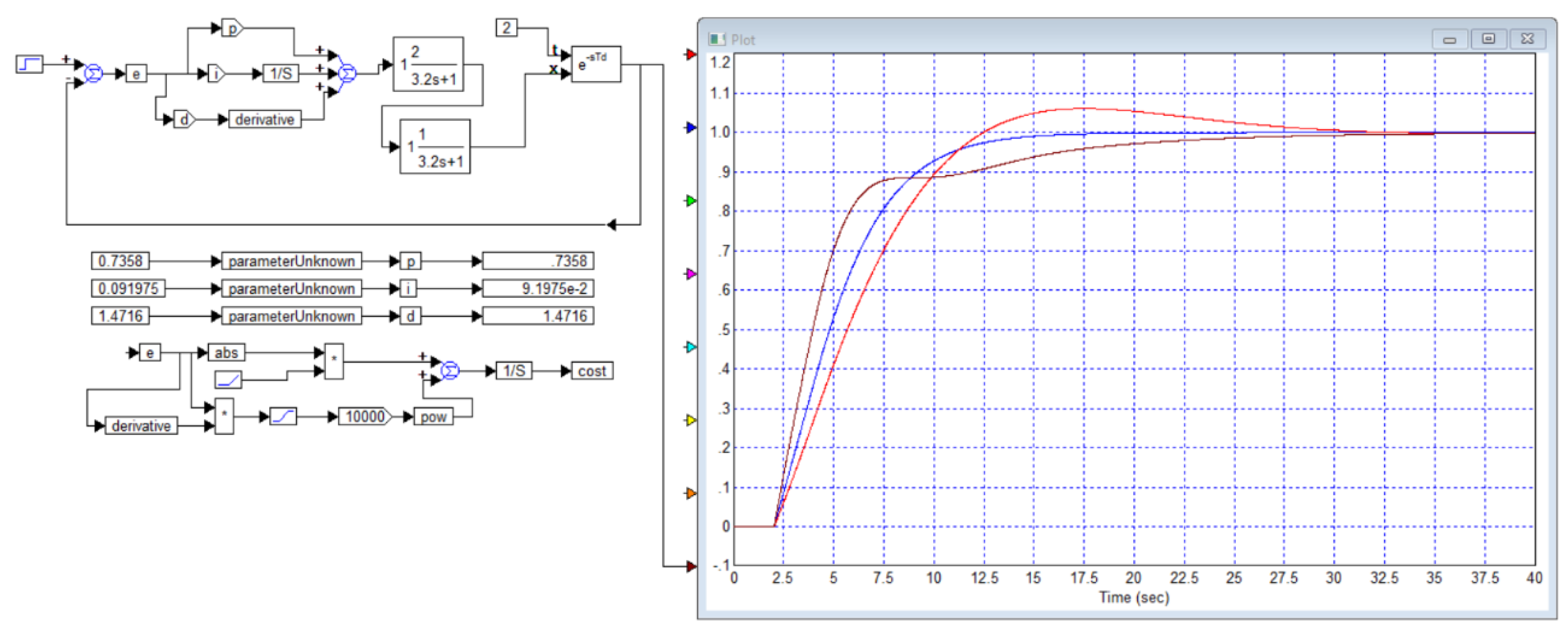

We have simulated this system, the results are shown in

Figure B2. We have also calculated a controller that provides maximum speed with no overshoot, the result is shown in

Figure B3.

Figure B2 confirms that our simulation results are consistent with the simulation results in [

29], so the graphs obtained can be trusted. However, in the paper, the transient process with 5% overshoot provides a response time of 8.2 seconds, while the process without overshoot can only be obtained with a response time of 15 seconds. Our optimization gives a result with a response time of 9 seconds with an overshoot of less than 1%, and if no overshoot is required, our result, as shown in

Figure B3, gives a response time of 10 seconds, which is 1.4 times better than the result in [

29].

Conclusion 1. The article [

29] presents a result which, in the opinion of its authors, is the best result with a PI controller that ensures the absence of overshoot. This statement is erroneous: we obtained a result with a better response speed by a factor of 1.4, with other PI controller coefficients.

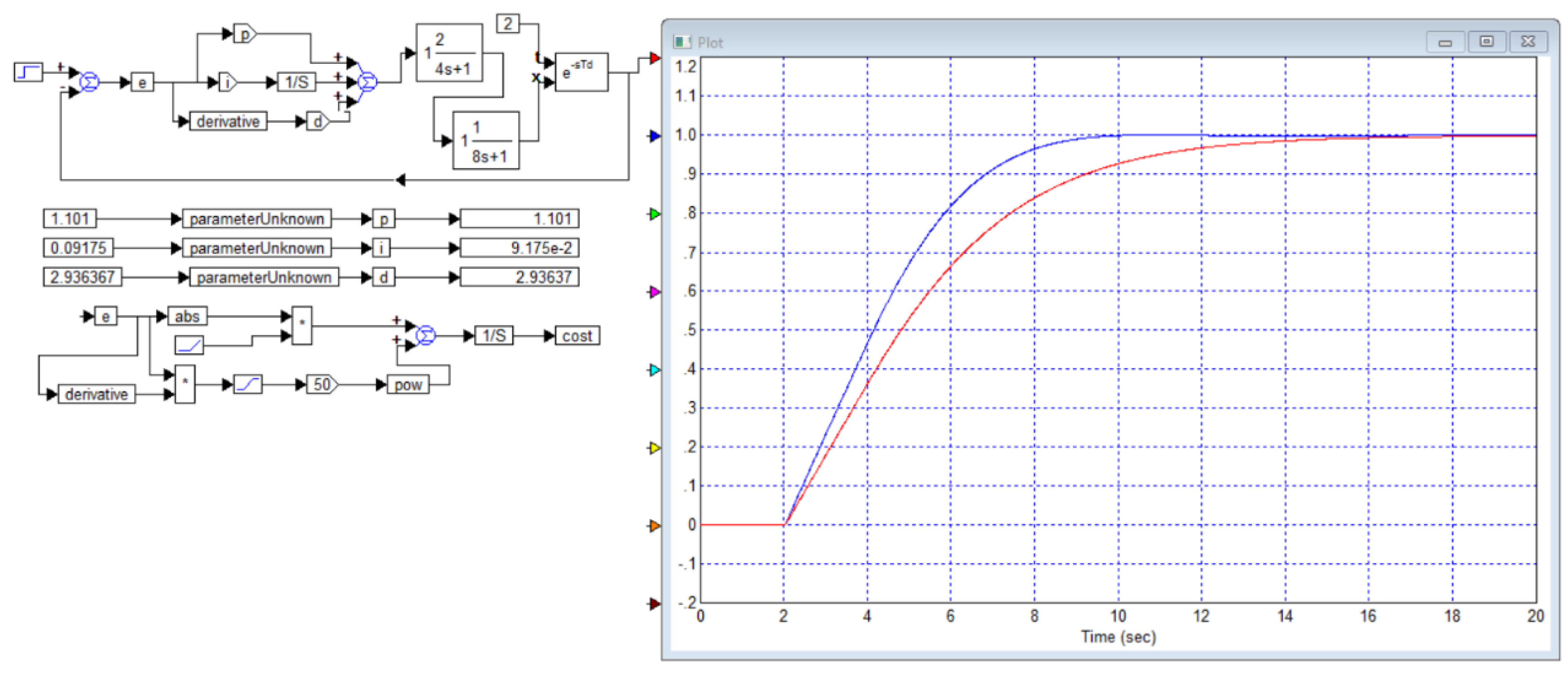

The next example in the same article considers the problem of controlling an object with a transfer function of the following type:

This is also obviously a fictitious example. For this object, a PID controller with the following parameters is calculated:

Kp = 1.101,

Ti = 12

s, Td = 2.667

s. The PID controller equation is not found in this publication. Apparently, the authors did not provide it due to carelessness, but from the equations for closed systems, one can conclude that it is assumed to be in the following form:

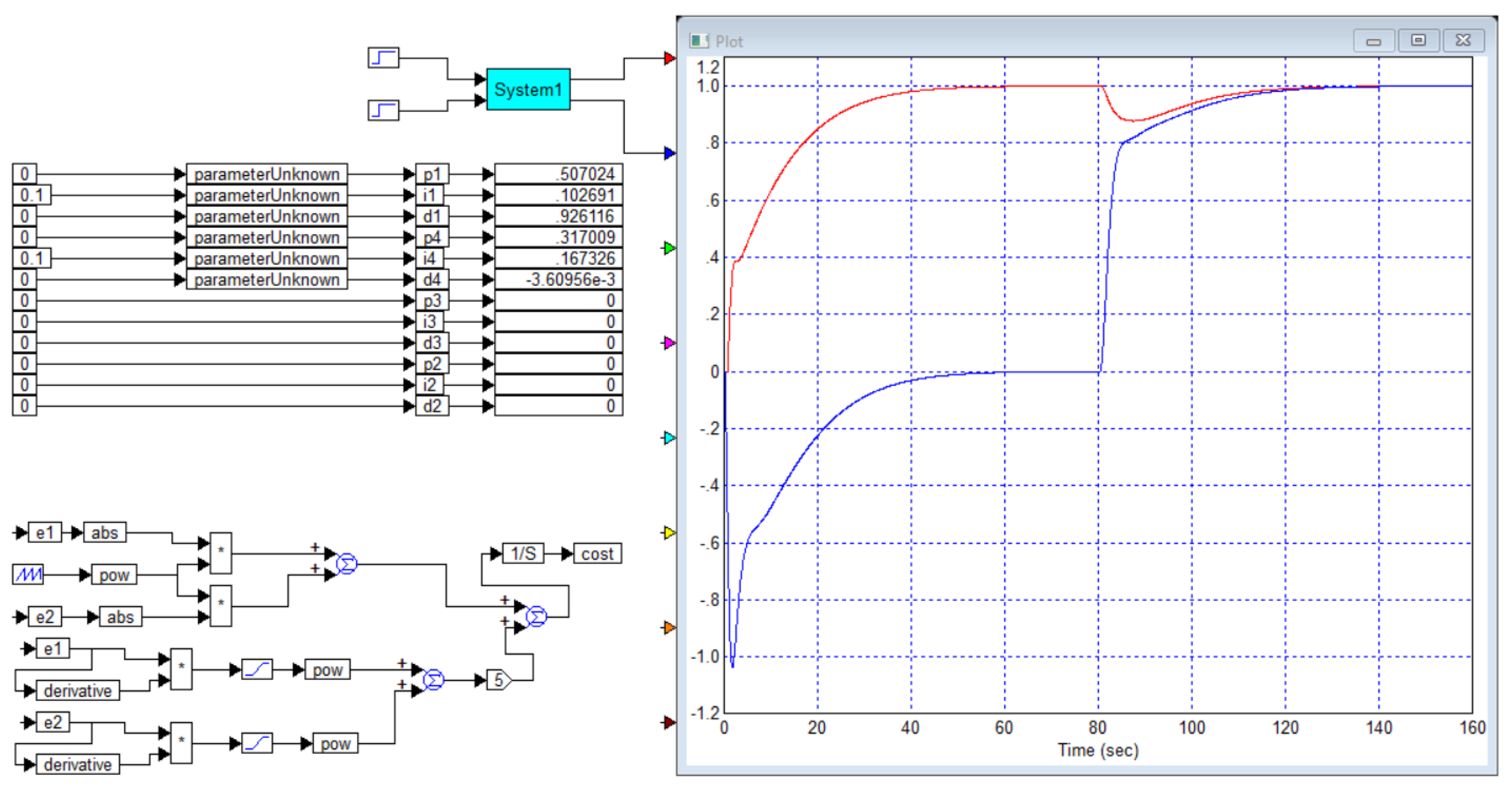

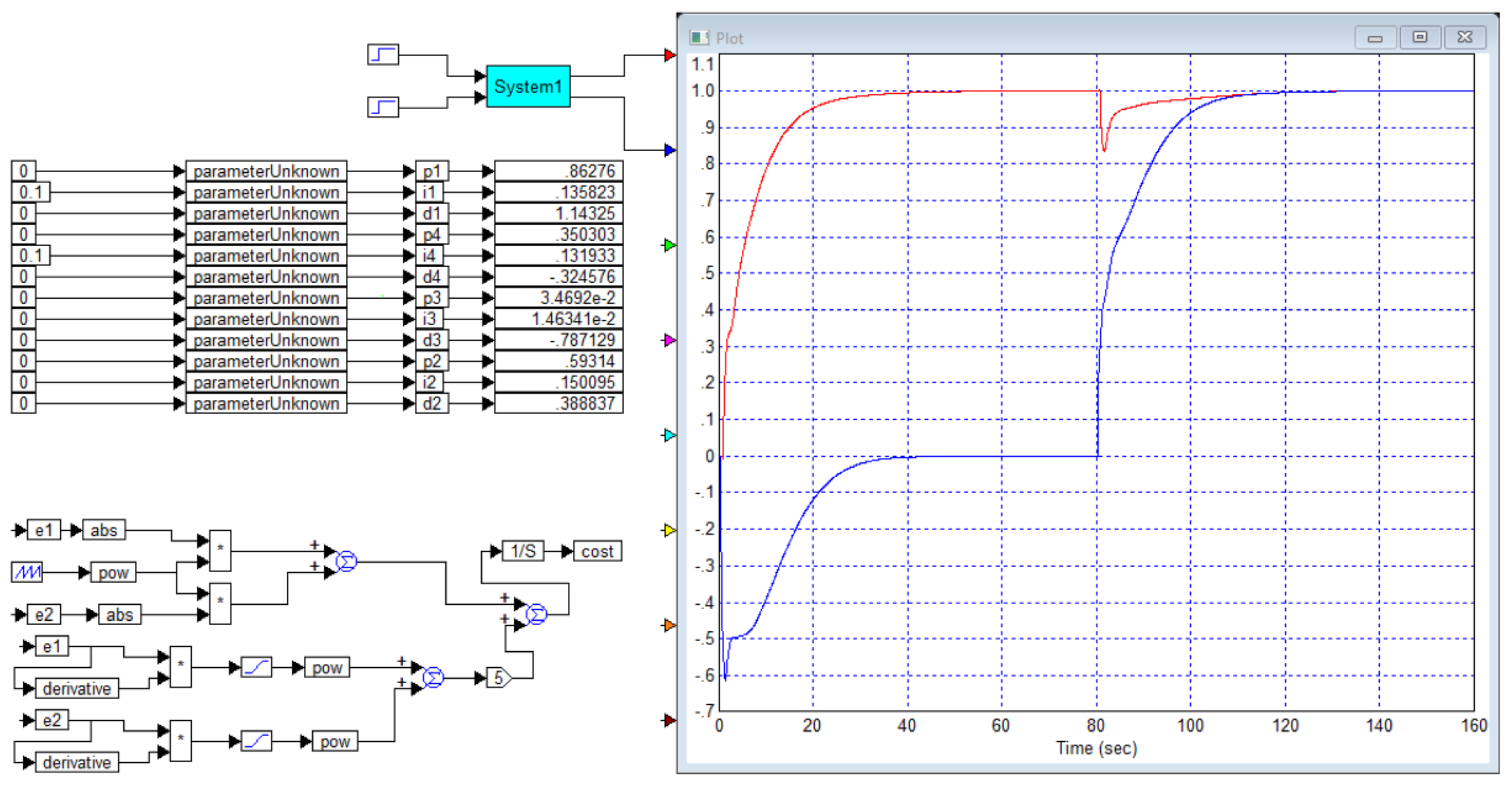

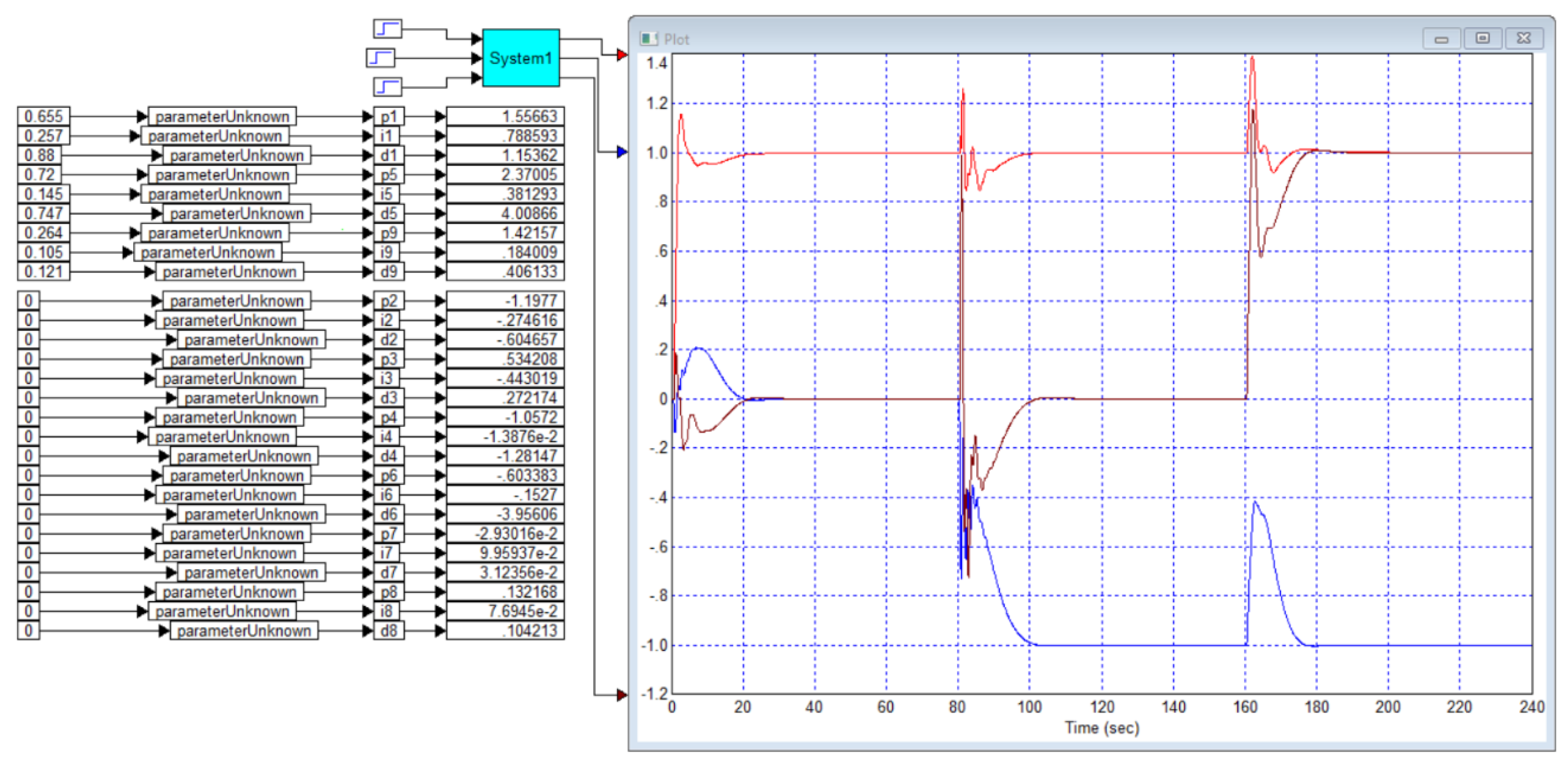

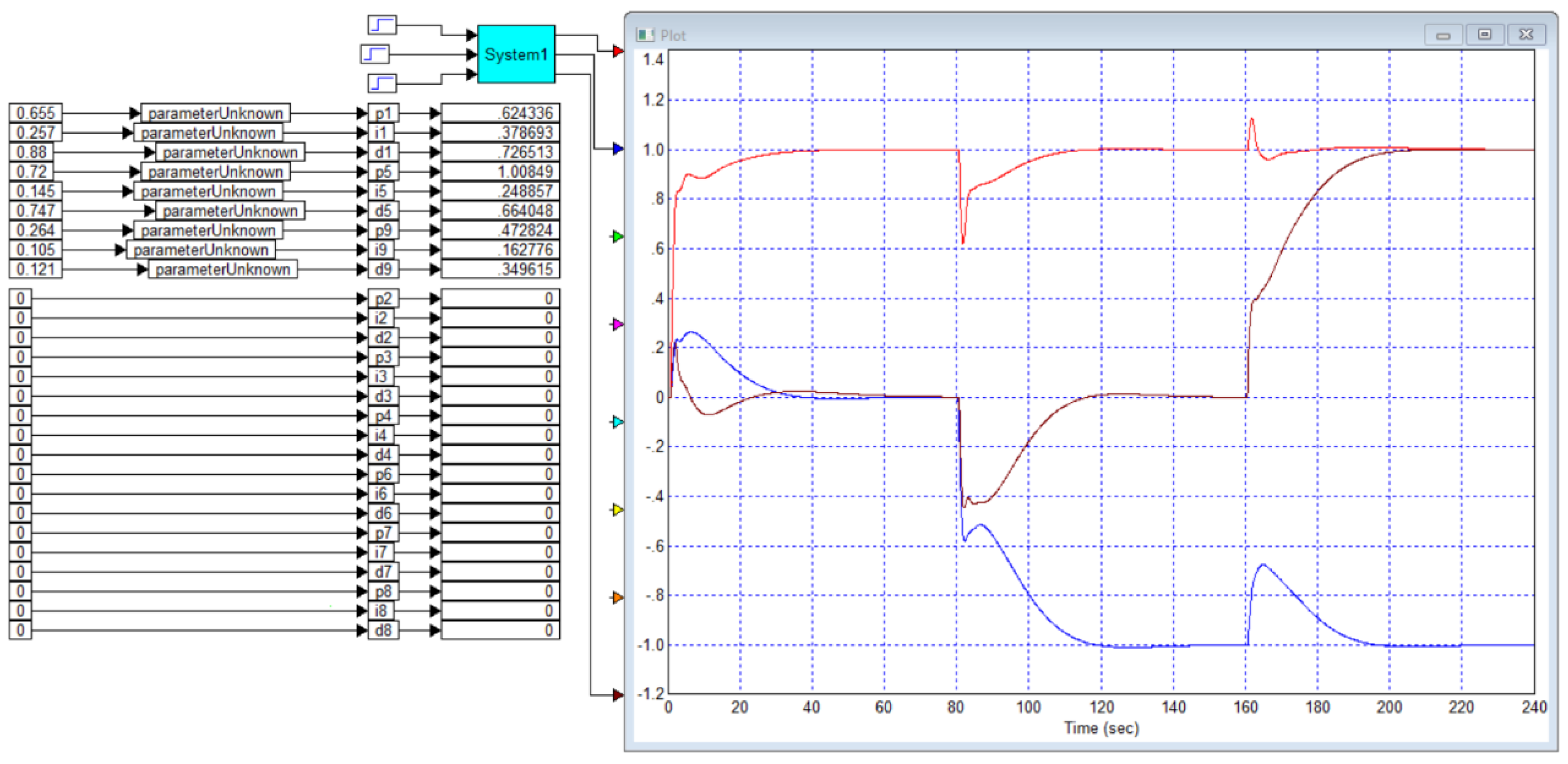

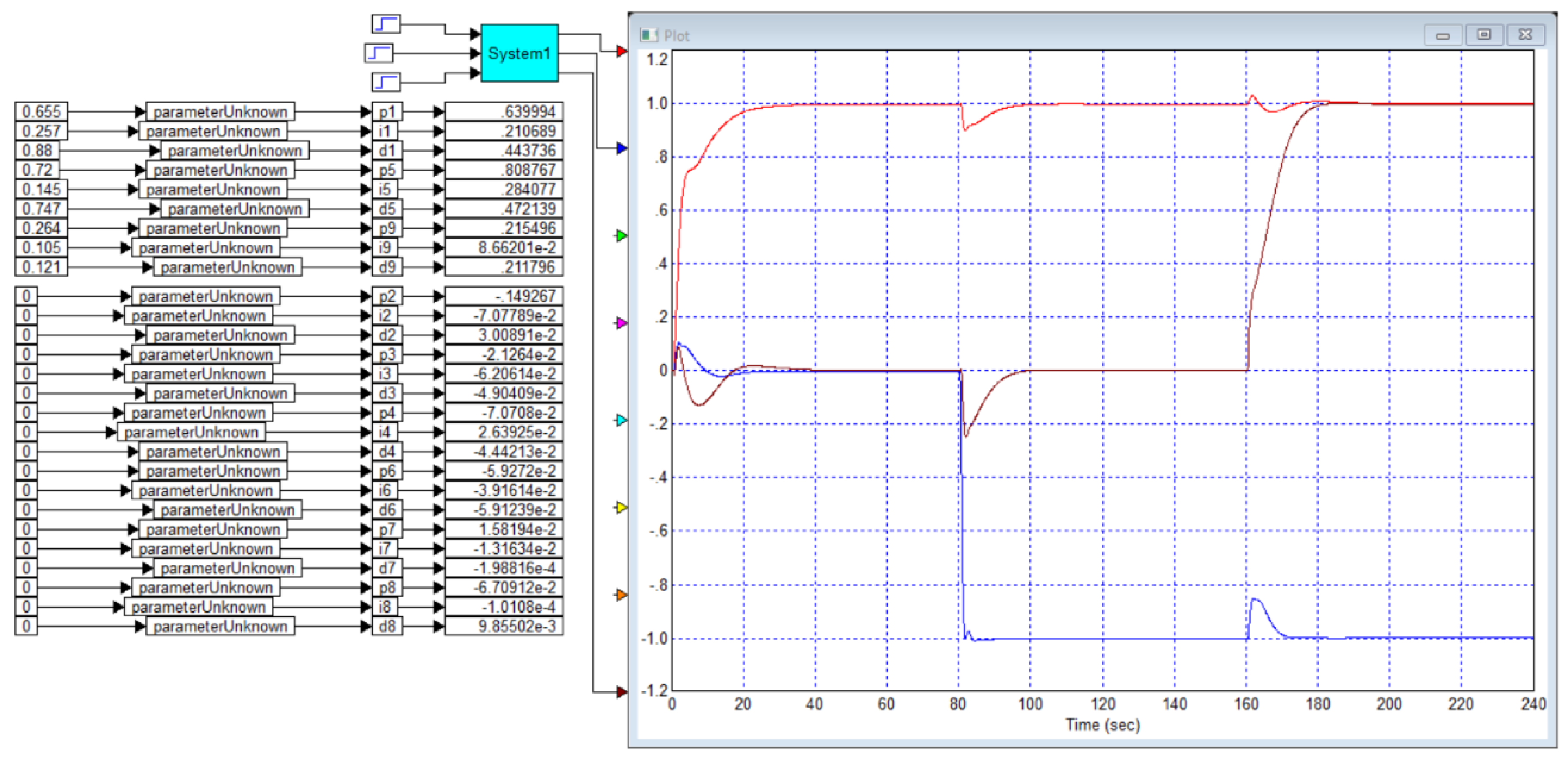

The paper also gives the transient process for the object and the controller for this case, which is shown in

Figure B2.

From

Figure B5 it is evident that the PID controller, which the authors of the article [

29] consider optimal for the object of example 2, i.e. for the object (B3), is far from optimal, since we obtained a PID controller for this object with which the duration of the transient process is 10 seconds versus 16 seconds with the controller from this article, and there is also no overshoot.

Conclusion 2. The article [

29] presents a result which, in the opinion of its authors, is the best result with a PID controller that ensures the absence of overshoot. This statement is erroneous: we obtained a result with a better response speed by 1.6 times, with other PID controller coefficients.

The third example differs from the second example in that the coefficient in the second bracket in the denominator is taken equal to the coefficient in the first bracket, because of which the object model takes the following form:

In the article [

29], a controller with the following parameters is calculated:

Kp = 0.7358,

Ti = 8

s, Td = 2

s and for this case, transient processes are given.

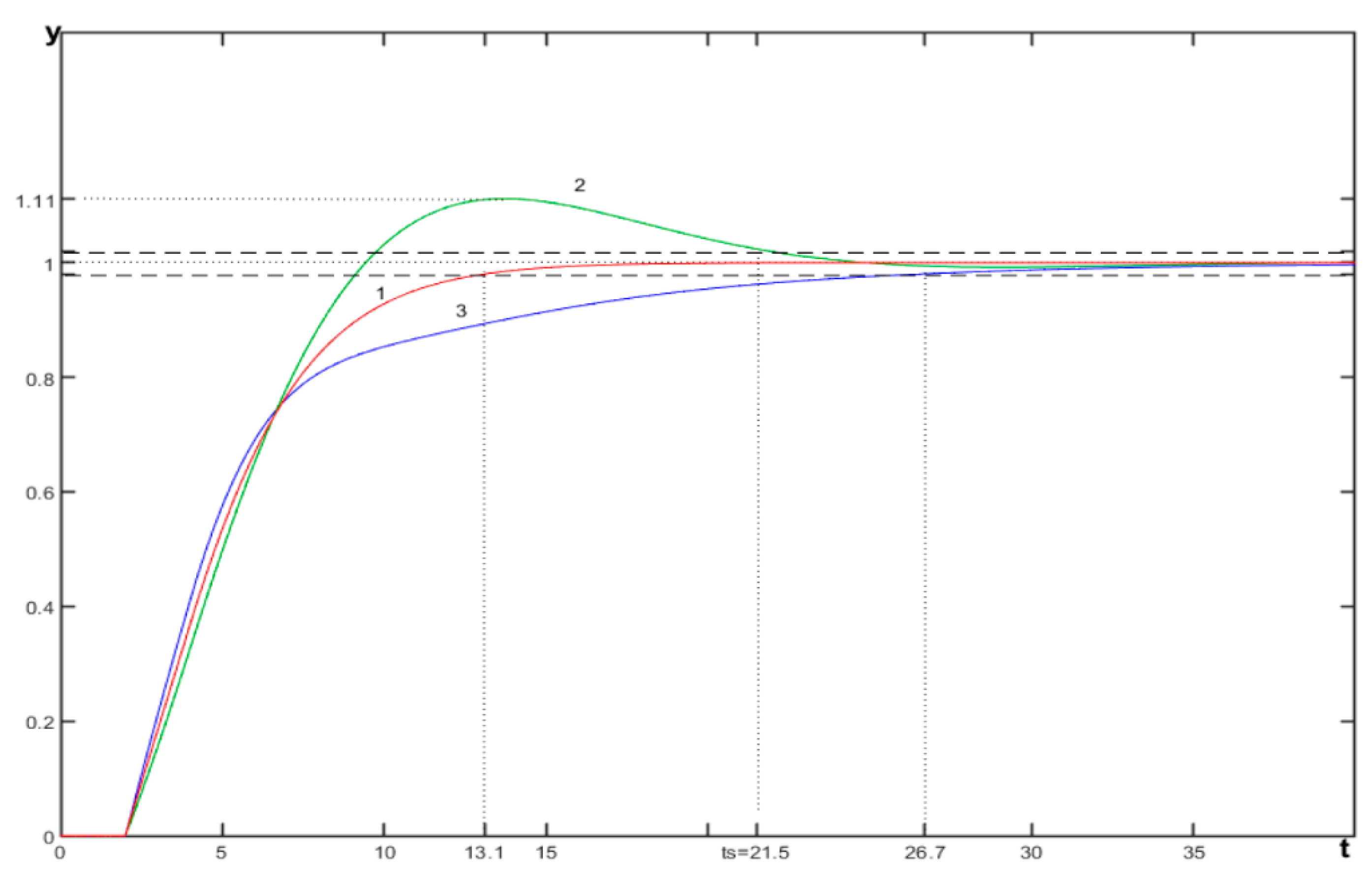

The authors of [

29] then provide graphs showing how the transient process will change if the time constant in the object model changes by 20% up or down. When the time constant of the object model increases by 20%, overshoot occurs to a value of 11%, and when the time constant of the object decreases, the zone

from the prescribed state changes from a value of 13.1 seconds to a value of 26.7 seconds. The corresponding graphs from this article [

29] are shown in

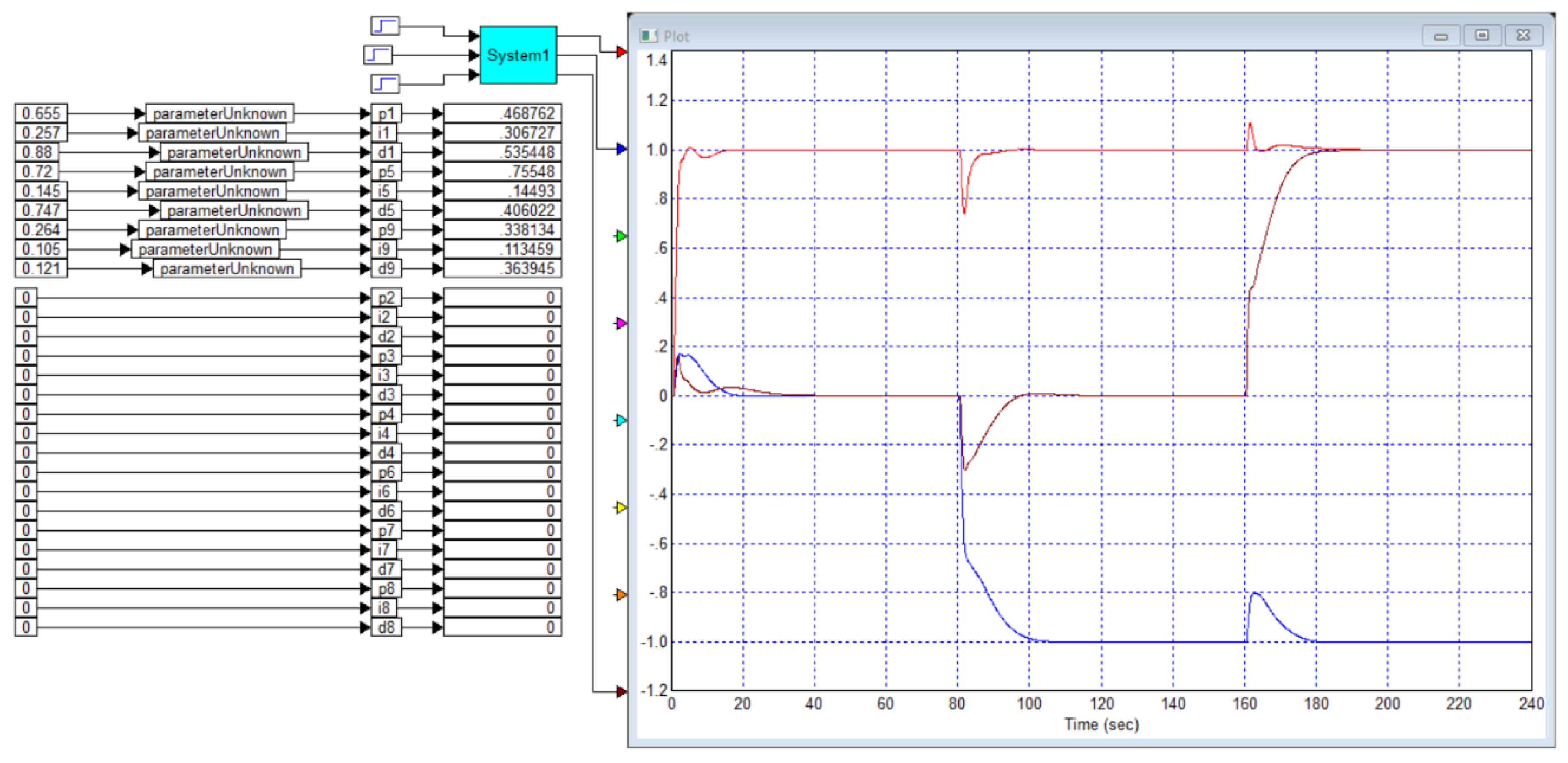

Figure B6. We simulated this system with the controller calculated in this article, the result is shown in

Figure B7.

Conclusion 3. The article [

29] presents a result that is refuted in some details by modeling. In particular, with an increased parameter, the overshoot is still less than stated in the article (7%, not 11%), but longer (it ends not after 25 seconds, but after 32 seconds). The processes also differ when this parameter is reduced. In addition, all three graphs are much more clearly inconsistent in the initial stage of the transient process: in the graphs from the article, they are very close to each other, and when modeled in the VisSim 5.0e software, these graphs diverge noticeably, and differ in the rate of increase.

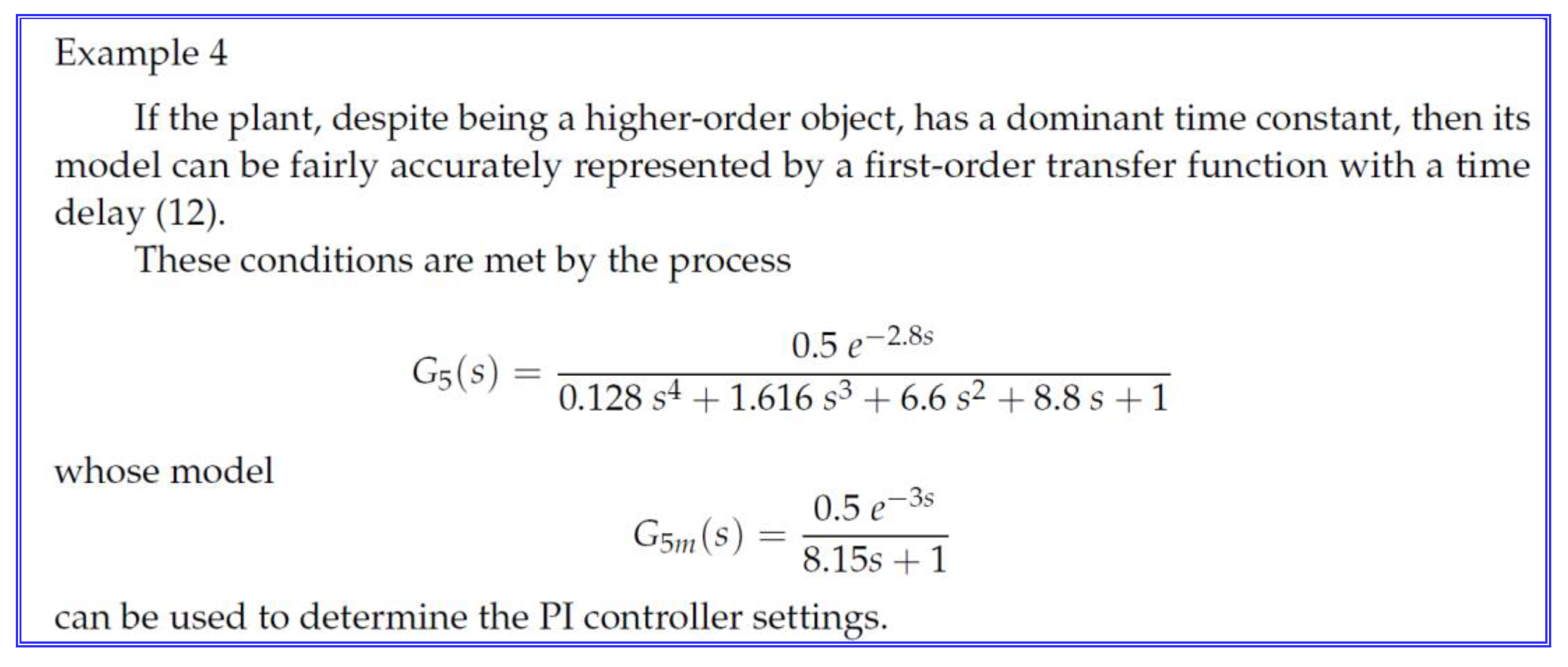

The most interesting thing in this article happens further with the fourth and fifth examples. The fourth example is that the authors propose to replace the complex model with a simpler one, as shown in the fragment given in

Figure B7.

Figure 7.

Fragment with the problem statement for example 4 from the publication [

29].

Figure 7.

Fragment with the problem statement for example 4 from the publication [

29].

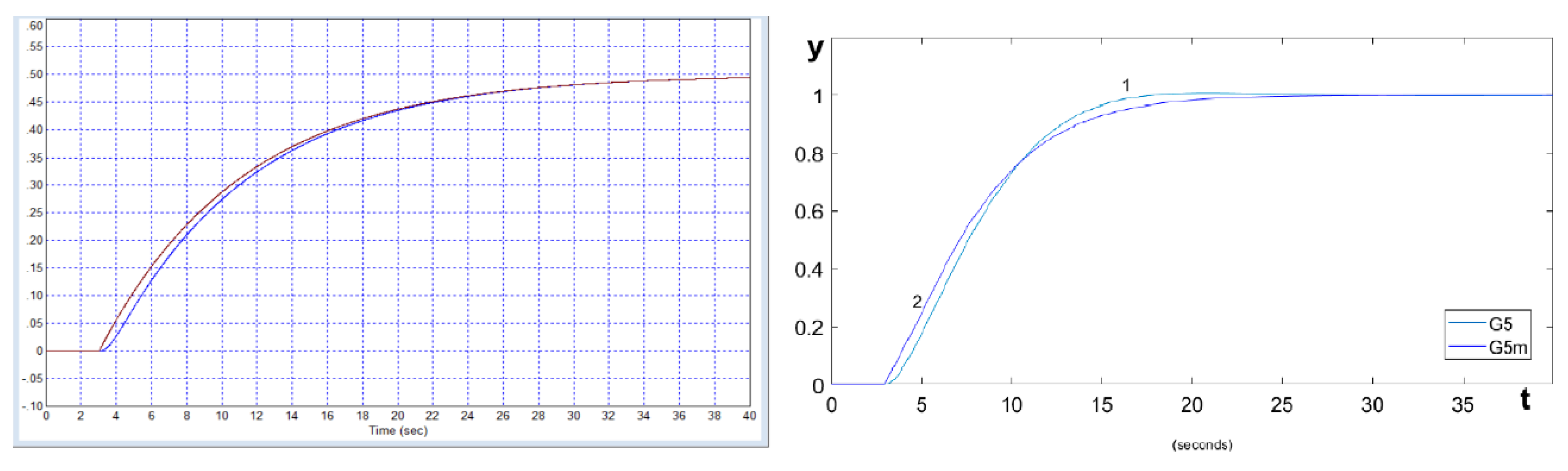

A natural question arises: to what extent is it permissible to replace a fourth-order model of an object with a first-order model? We believe that this is unacceptable if there are methods for using the exact model and if the exact model is known.

It is interesting that this article provides a comparison of the response graphs to a step jump of the object with the original transfer function and the model used for calculations. But this article does not contain a graph of the transient process in the resulting system, although the results of the PI controller calculation are provided. We will make up for this shortcoming. Firstly, the provided graphs of the comparison of transient processes are also unreliable. For comparison, we will provide these graphs side by side in

Figure B8.

We see that in reality the lines are smoother, the duration of the process for the exact and approximate models on the left is about 40 seconds (we obtained it), while in the article it is twice as less, about 20 seconds, also in our modeling the graph of the exact model is always lower than the graph of the simplified model, while in the article these graphs intersect. From the left graphs it is clear that within the framework of the model used it is possible to find a more accurate approximation, from the right graphs it does not follow.

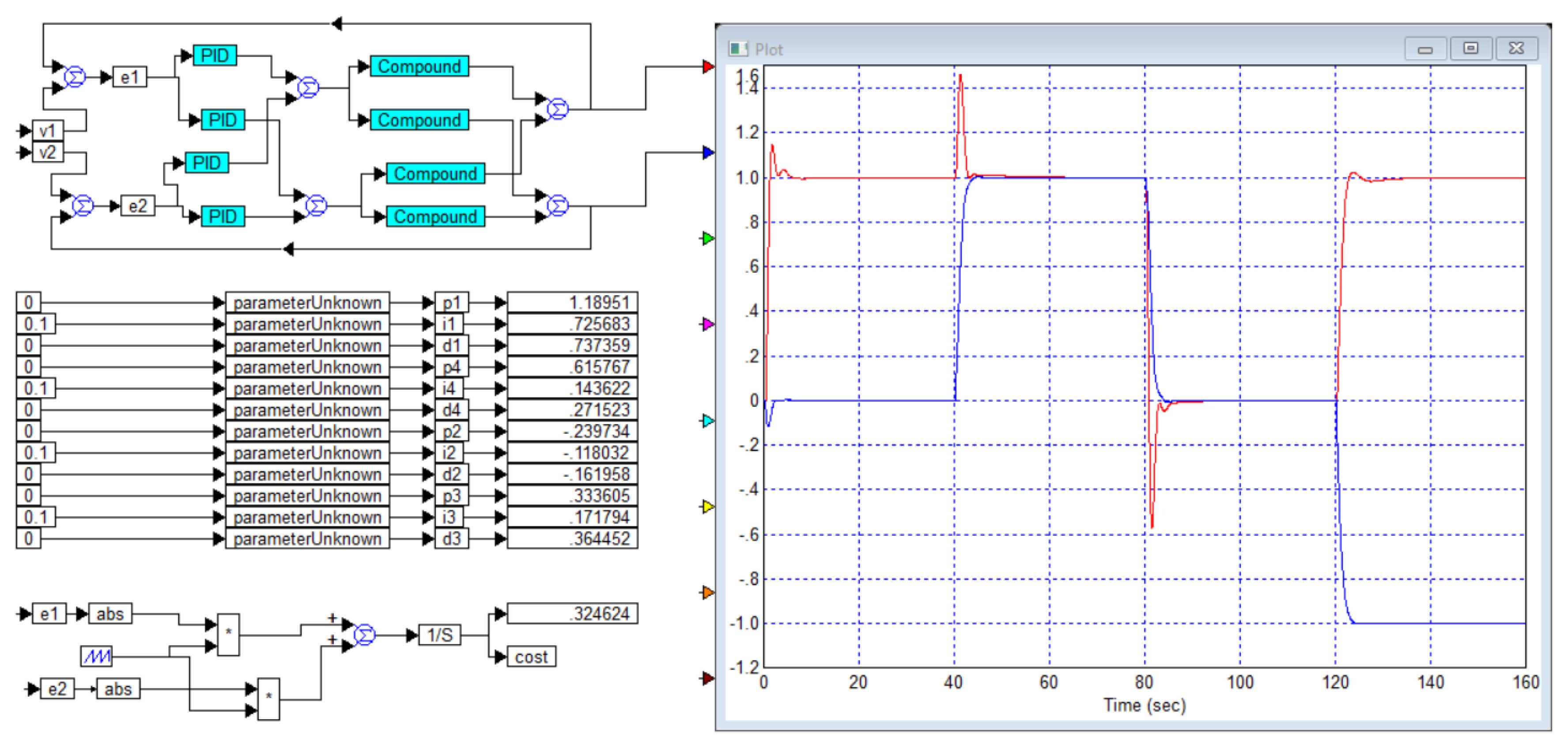

We believe that replacing the exact model with a simplified one is inappropriate for the reason that the authors of the article [

29] in all cases set the task of finding a controller that would not have overshoot in the system. We calculated the controller for the simplified model and then applied the results of this calculation to the exact model. As a result, we obtained a system in which overshoot is about 8%. The corresponding graphs are shown in

Figure B9.

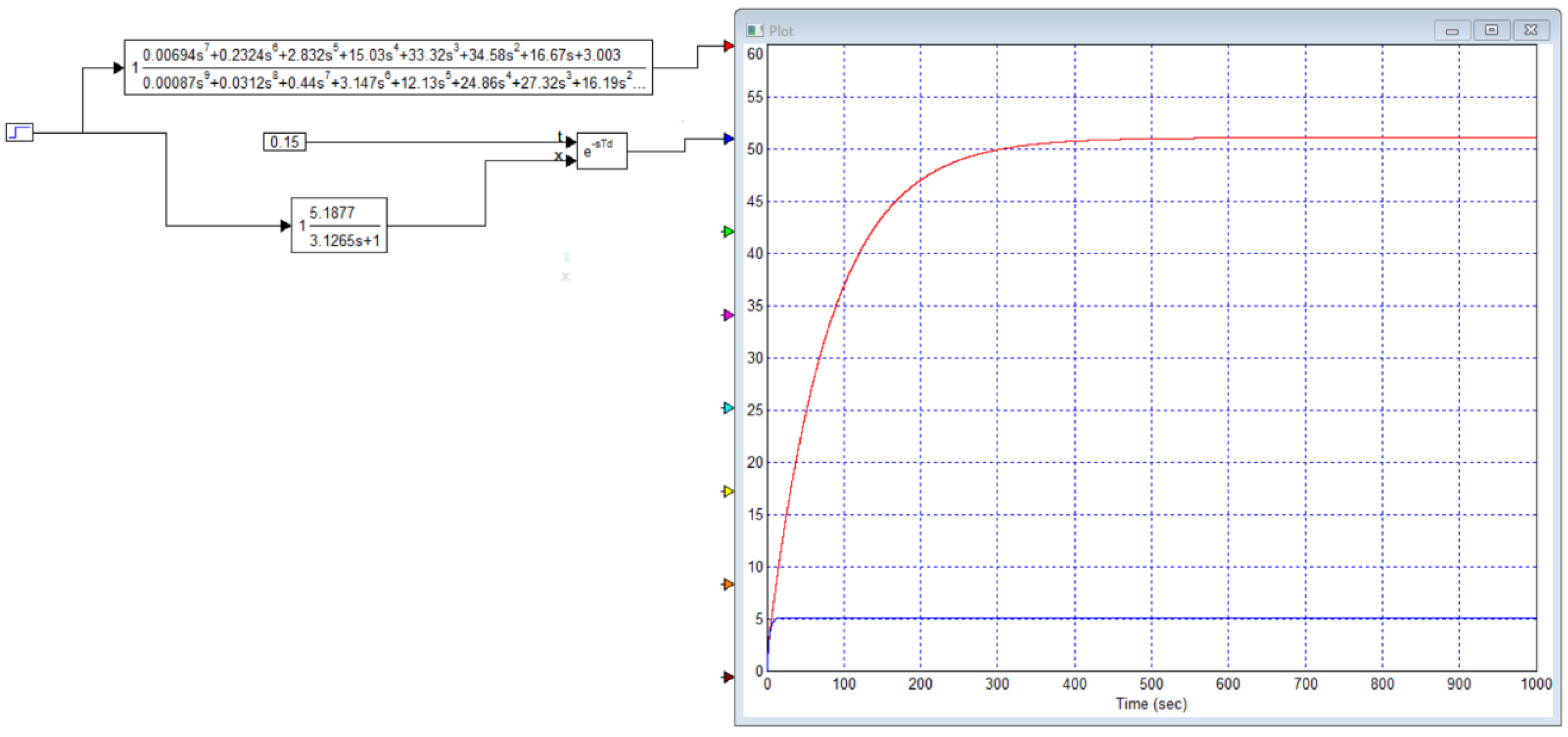

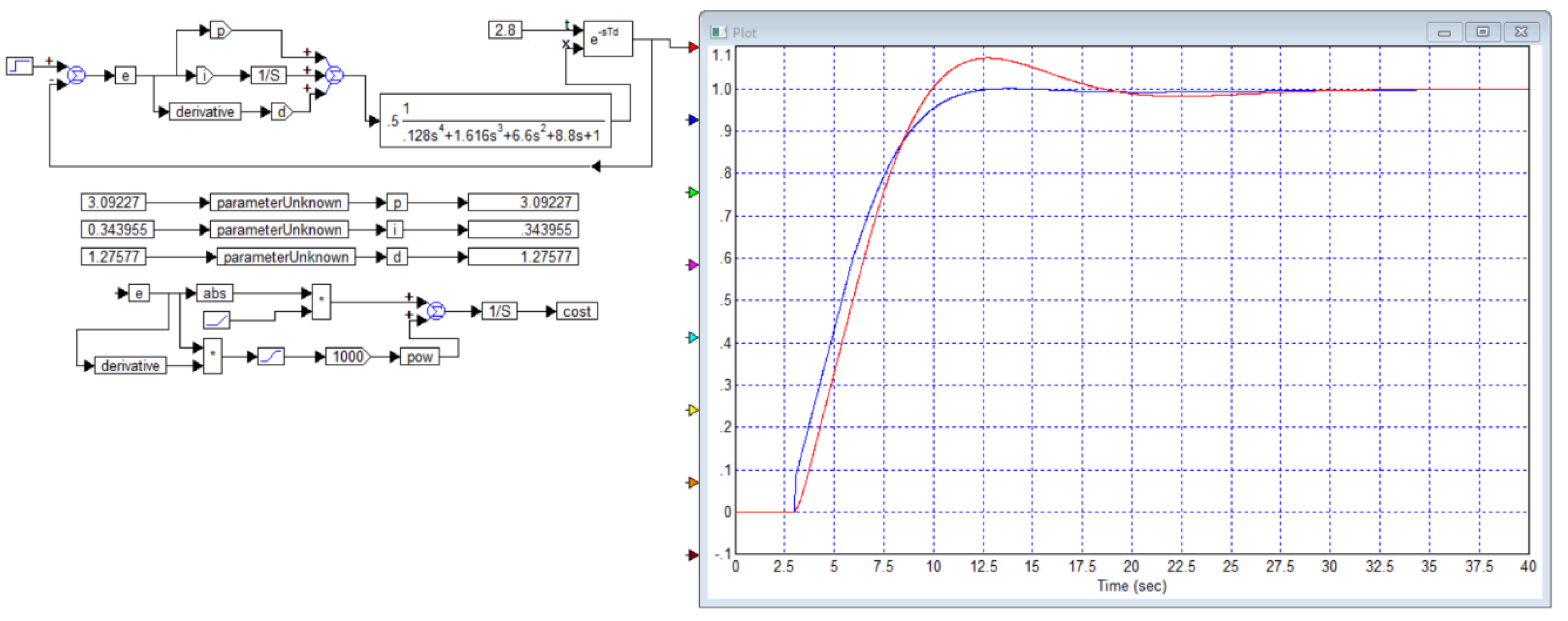

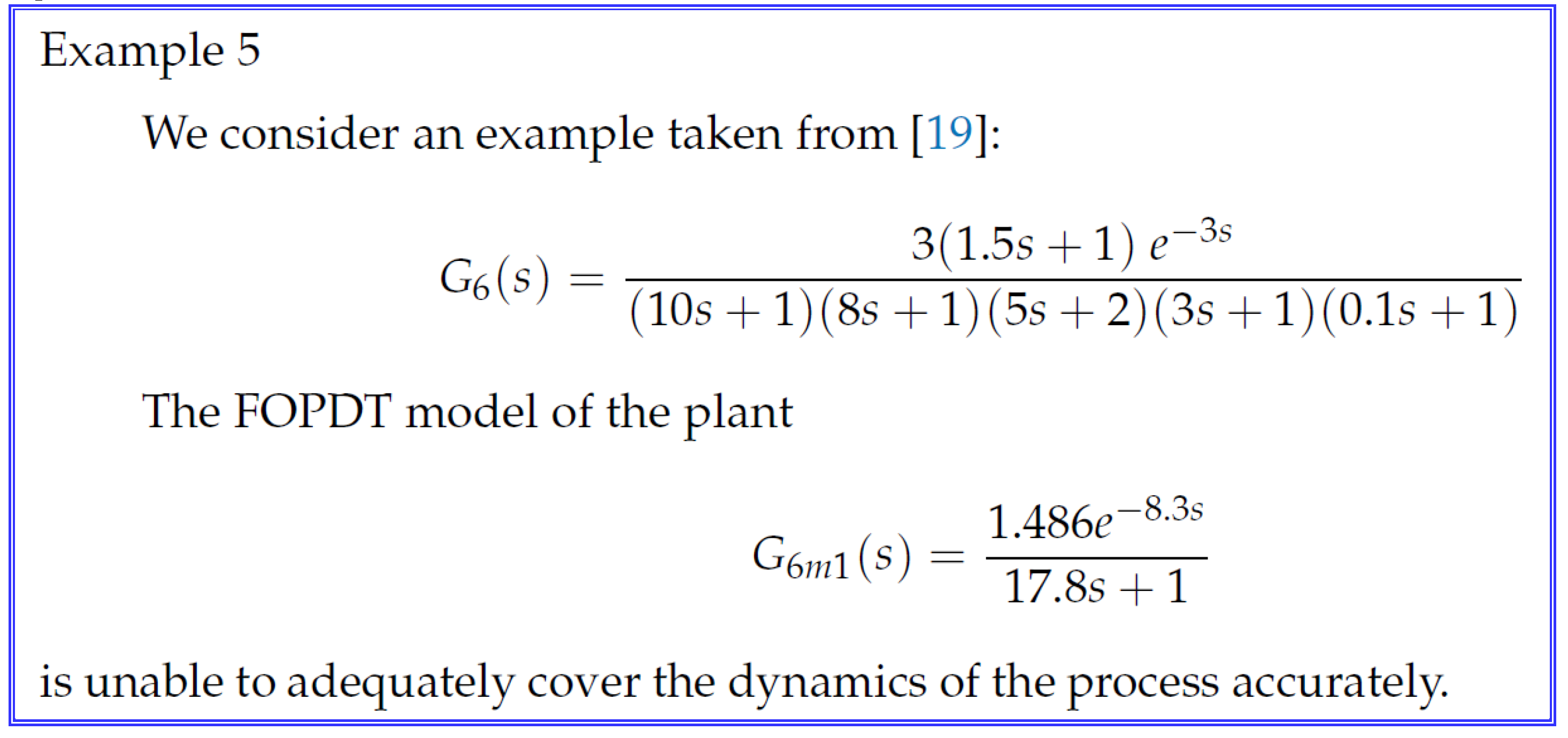

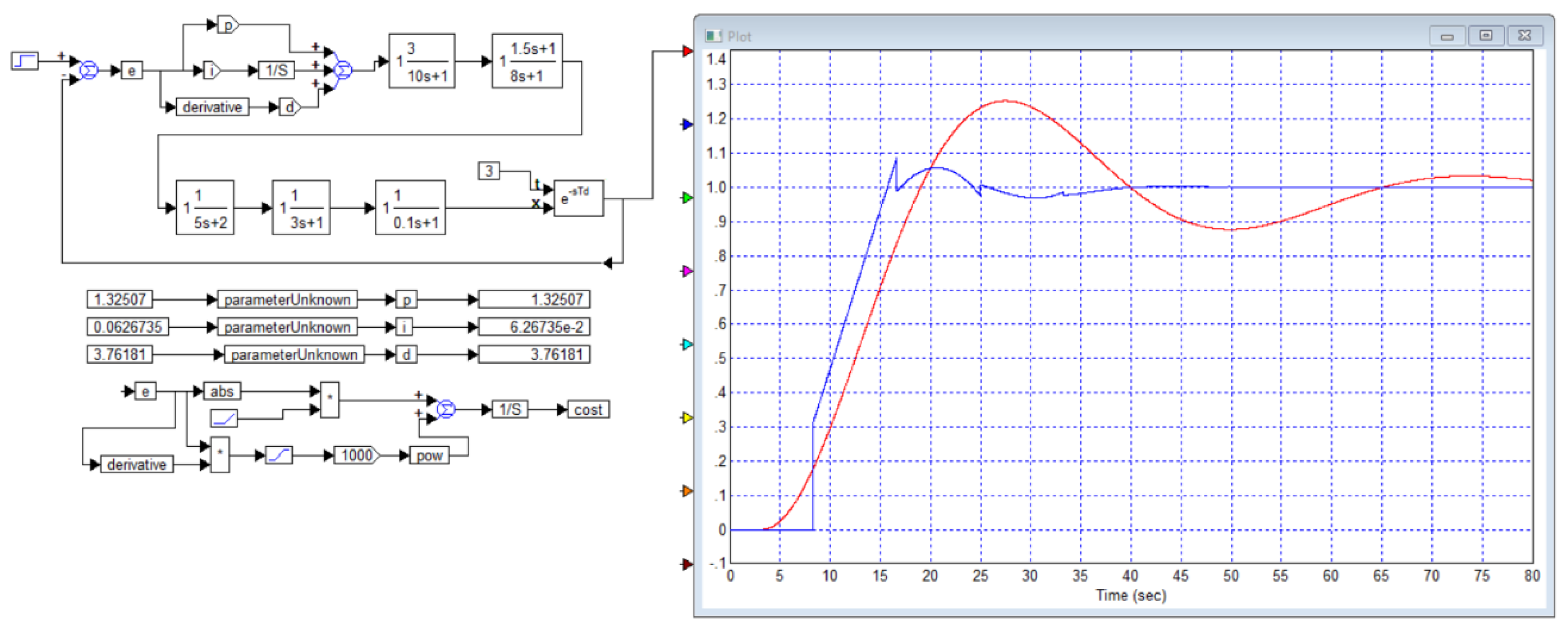

Finally, the fifth example is taken from another publication [

29], but judging by the model coefficients, this is also a fictitious example, and not an example taken from a practical problem, as shown in

Figure B10.

We insist that approximating a fifth-order plant with a first-order model does not make sense. To prove this thesis, we calculated the controller using a simplified model and applied the results of this calculation to a system with an plant described by an exact model. The result is shown in

Figure B11.

In this system, the overshoot is 25%, the transient process contains more than one oscillation wave. If the control problem was set without overshoot, then this example demonstrates that the problem is not solved. For comparison, we optimized the controller using an accurate model of the object. Figure B 12 shows the result. There is no overshoot in the system, the duration of the transient process is about 27 seconds. The article [

58] presents a transient process with a duration of about 35 seconds, and the method for obtaining these transient process graphs still raises great doubts.

Figure B13 shows the result of using the controller proposed in the article [

29] to control the object from example 5, for which this controller is proposed. It is clear that the result is deplorable: the overshoot is 43%. The duration of the process is 240 seconds.

Conclusion 4. In the article [

29], examples 4 and 5 present a method for calculating regulators using a simplified model of a complex object. This method is erroneous, since the calculation using a simplified model turns out to be unreliable (this statement is proven separately), and also for the reason that checking the functioning of the objects from these two examples with the regulators proposed in this article for these two examples shows that the transient processes in such systems differ greatly from the desired ones and differ from those given in this article.

Conclusion 5. The use of fictitious examples to demonstrate the operation of the method is acceptable, as it is used in other articles published by MDPI.

To avoid the impression that this conclusion was made based on a single article, we will give other examples. For example, in article [

60], the simplest fictitious models of objects are also used to test the ideas put forward, as shown in Figure B 14. We will also give an example of article [

61] and an illustrative example from it, shown as a fragment of the article in

Figure B15.

Of course, mistakes in other people’s articles do not give us grounds to make mistakes in our own articles. However, the development of science should be based not only on each author striving to publish his own articles as soon as possible and as many as possible, but also on these articles being read by specialists in the field to which each article pertains. In addition, if a specialist sees an obvious mistake, he has the right to be surprised, and if a journal or publishing house allows for feedback from readers, then it is highly desirable that the errors found by readers be corrected by the editors in agreement with the authors or at their request. Moreover, it seems to us that if the mistake is obvious, then the authors of the article should be interested in correcting it.

In the paper [

62], in equations (1) and (13), those factors that should be explicitly present as factors are moved so that they become part of the indices of the preceding quantities. Any specialist in this field will easily see this error. However, untrained readers will not realize that this is an error, and therefore will not understand what kind of relationship is given here. Of course, the reviewers should have seen this error.

In equation (1) it is written [

62];

As we can see, there are two typos here: first, what should be a factor has turned into an index at “K”, and second, in this fragment “d” should be an index, and “s” should be a factor, which looks slightly different in the original.

In equation (13) it is written [

62];

As we can see, two factors have turned into indices, and the index “I” (uppercase letter from “i”) in the second term has turned into “1” (a digit) or into “l” (lowercase letter from “L” if it is not written in italics). In addition, in the text, indices are repeatedly turned into factors, since they are written in the same register as the value itself. That is, the same values in the text are designated differently than in the formulas where these same values are used.

It is known that Albert Einstein also had typos in his early articles, but he always made sure that subsequent issues of these journals published corrections with apologies and corrected formulas [

63]. Apparently, modern authors should also take care to correct typos and errors in their articles.

In another paper [

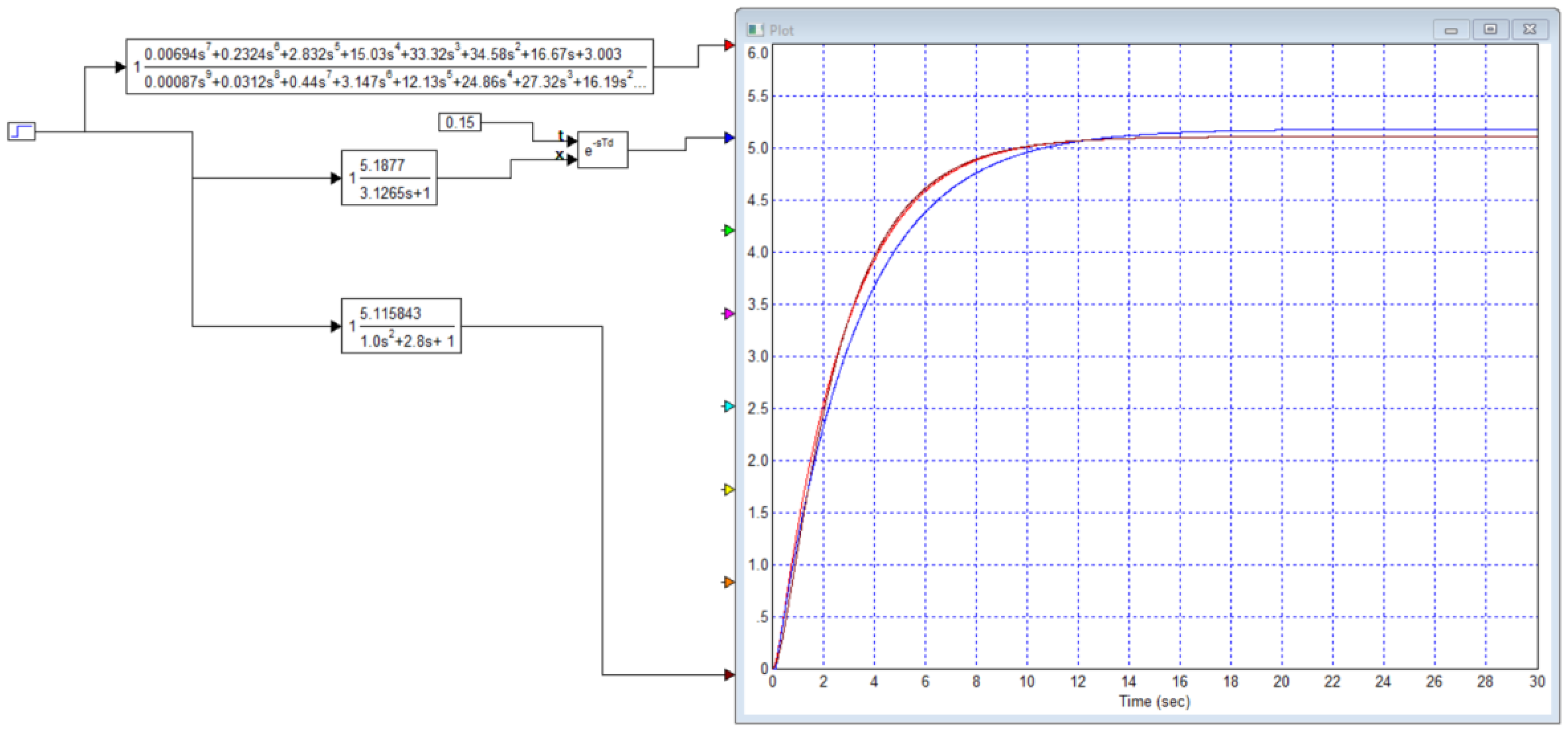

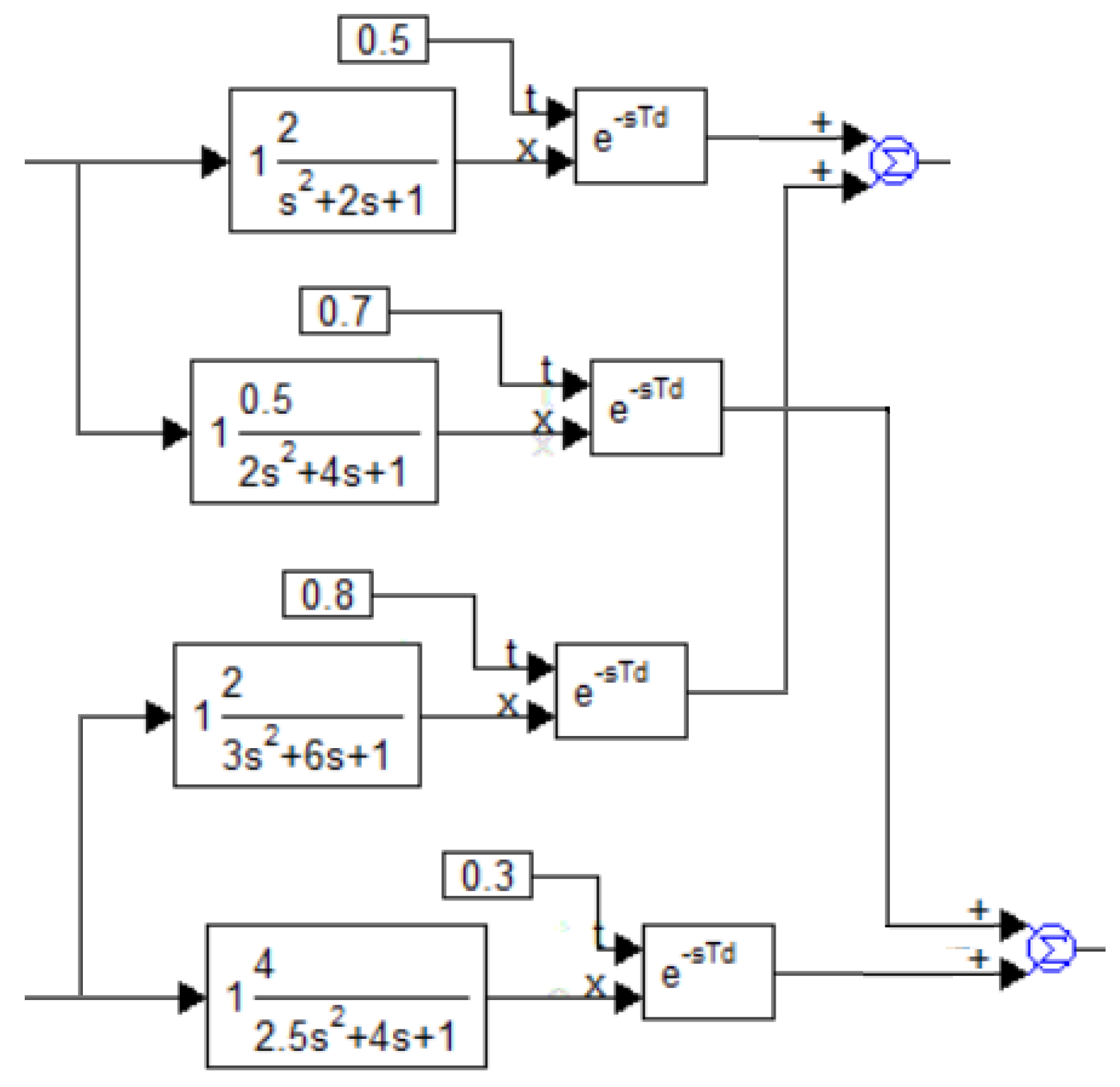

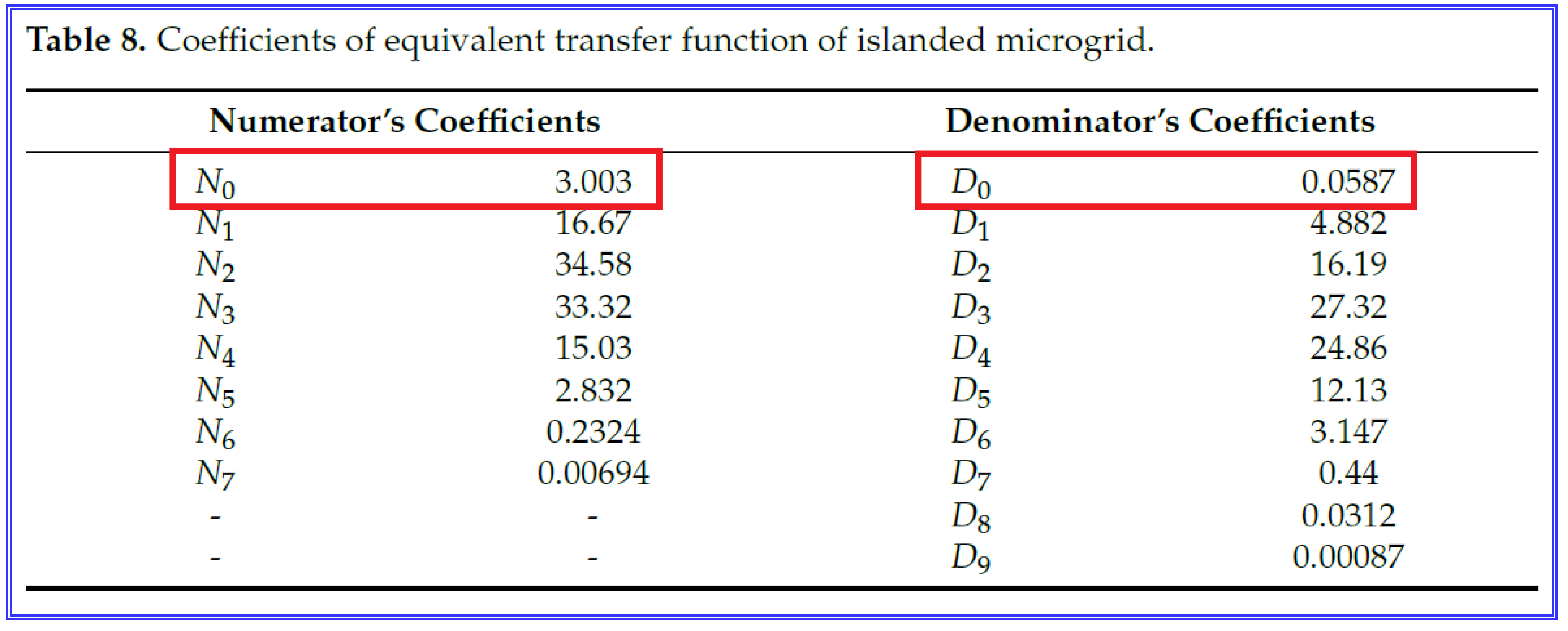

64] an approximation of a ninth-order link by a first-order link is proposed.

The ninth-order model is given by equation (22), and the coefficients of this equation are given in Table 8. Model (23) is proposed as an approximation. Relation (23) is given in the following form:

An exponent to a numerical power is a number, not a function. In this case, there should be a transfer function of the delay link, where the module of the exponent indicates the magnitude of the delay, but at the same time, the variable “

s” should be present in the exponent, since this is still a function, a model of the delay link, and not an ordinary number. Therefore, the following should be written:

In addition, it is quite obvious that the constant transfer coefficient of the model must coincide with the transfer coefficient of the link that is being modeled. The simplified model is represented by the relationship above, and the original mathematical model is designated as equation (23) and is represented by the following relationship:

In this case, Table 8 (numbering according to this article) gives the coefficients of this model, as shown in

Figure B16.

When

the ratio that the authors of the article [

64] wanted to approximate becomes a simple fraction:

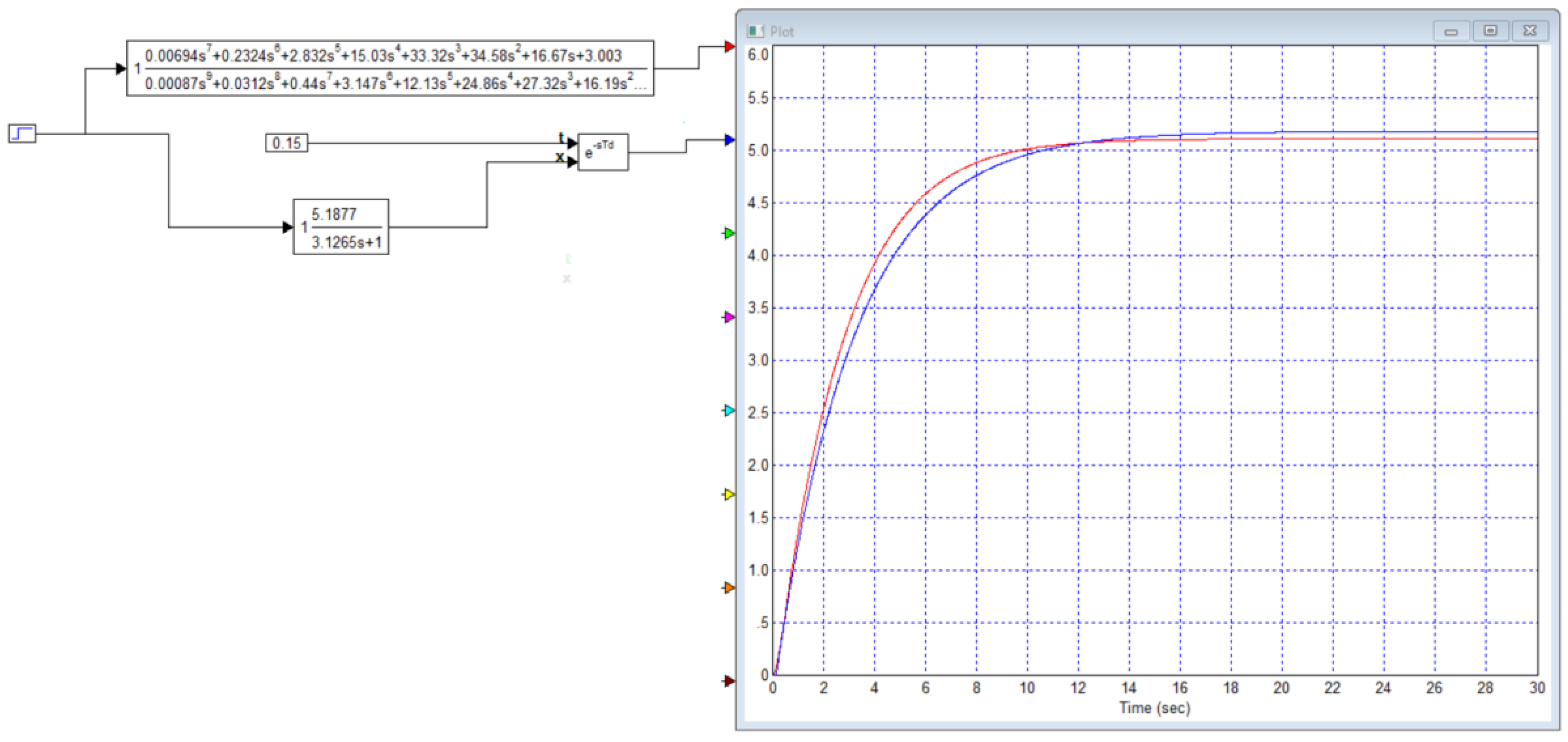

This is almost ten times more than it should be. So the coefficient in Table 8 should be at least ten times less, i.e. there is an extra zero after the decimal point. Obviously, it should be D0 = 0.587. However, even in this case, the coefficient should not be chosen equal to 5.1877, as stated in the article, but it should be equal to 5.11584327.

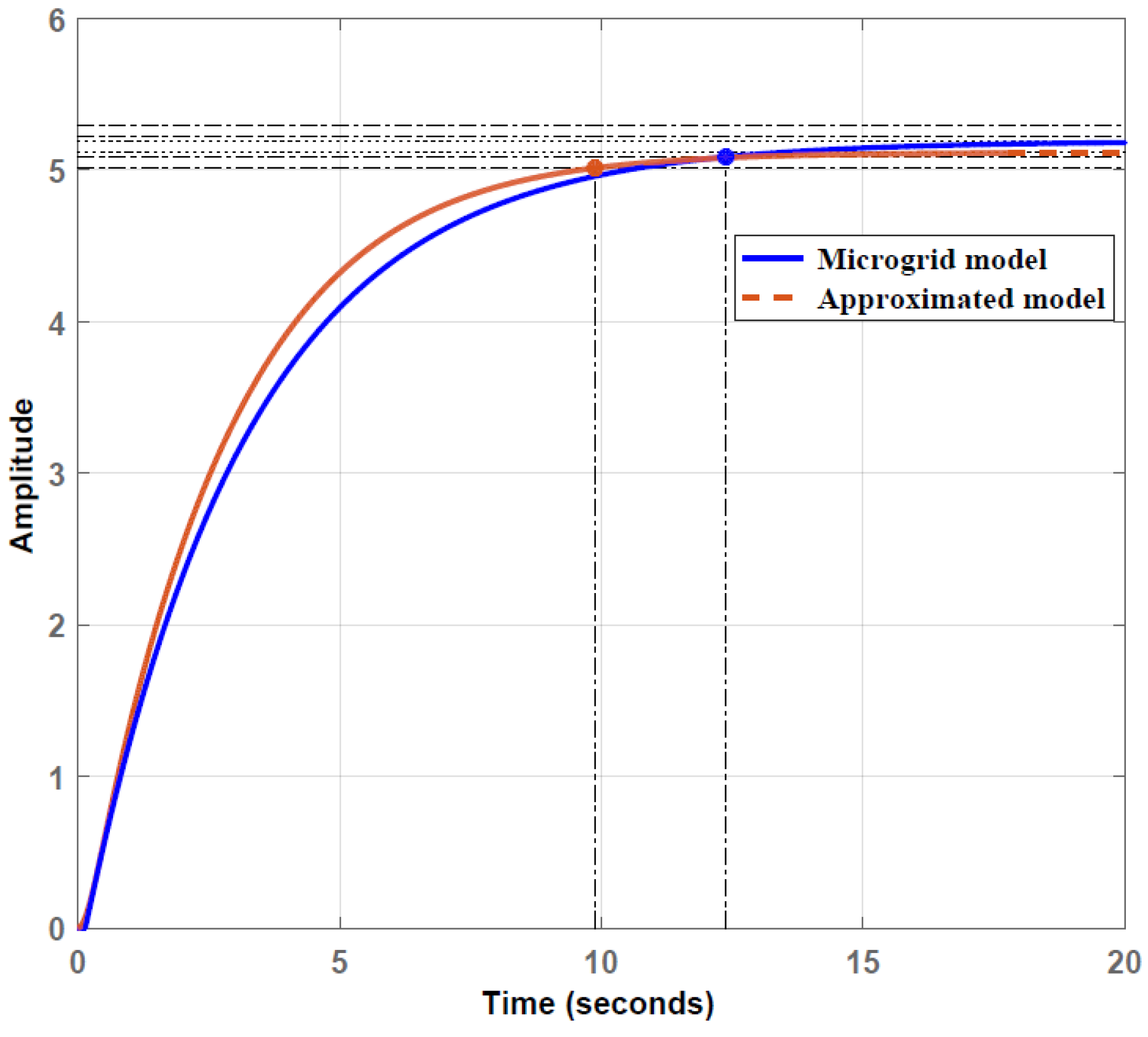

Accordingly,

Figure 7 in this article is a fake. This figure is shown in

Figure B17. This figure shows a surprisingly accurate match of the transient processes from the original exact model and from the proposed approximation for it. If we use the coefficients that are given in Table 8, then there will be no such match, but there will be a difference of about 10 times. There are still a number of shortcomings that can be pointed out in this article, but only the most obvious ones are listed here, which should have been noticed by absolutely any reviewer familiar with the field of knowledge for which this article is written. Our students know that checking the correctness of the model in the region of zero frequencies and in the region of infinite frequencies is a mandatory action when calculating regulators, and this is done in the mind, since it is very simple, you just need to divide one number by another.

In addition, the original model has a seventh-order polynomial in the numerator and a ninth-order polynomial in the denominator. In the high-frequency region, such a frequency characteristic of such a model tends to approach the asymptote corresponding to the second-order model. Therefore, it would be better to use a second-order model for approximation.

If scientific articles in high-ranking journals included in leading scientometric databases and having high impact factors at the level of Q1 – Q2 in these databases were not currently given such great importance in the entire global scientific community, then such typos and errors could be ignored.

We entered into correspondence with the publisher so that they would contact the authors of the article [

64] for clarification. The authors admitted that in Table 8, in the value for the quantity,

there is an extra zero after the decimal point. For some reason, the authors called this error a “typographical error”. The publication of an article does not include the typographical process, what the authors type on their computer is what will be published, so this is not a typographical error, but a typo made by the authors. However, no one is going to punish them for this typo, they are only asking them to correct this article! However, while admitting the error, they did not admit that it was made by them (although it could not be otherwise), indicating as the culprit a mysterious printing house employee who was not there, and at the same time did not promise to correct this typo, and did not correct it.

In text answer authors proposed such recognition: “In the exponent of the FOPDT model, the coefficient “s” should be present. I am sincerely regretting this minor typographical mistake. Hence, it is beyond any doubt that

Figure 7 is a fake. The same can easily be obtained with the values given above. However, I am sincerely regretting two minor typographical mistakes, one in the coefficient of s

0 in the numerator of (22), and another in the exponent of e in (23). I can understand that the minor typographical mistake in s

0 of the numerator of (22) is creating some problem in understanding. This coefficient should be taken as 0.587, in place of 0.0587”.

At the time of writing, an uncorrected version of the article remains on the site. If the authors admitted that “

Figure 7 is a fake,” why didn’t they correct the article? And why didn’t the editors of the journal make the corrections? If corrections had been made, we would not point out this misunderstanding. But if a scientific article can be edited to correct errors, or it can be provided with comments regarding errors, this should definitely be done if errors are present and even if they are acknowledged by the authors of the article.

With regard to checking the coincidence of the original characteristic with its model in the region of zero frequencies, that is, zero time, the authors responded with a strange phrase: “The value of K is chosen when the system is stabilized. This is the way to obtain the value of K. No one can run the simulation for infinite time». That is, the authors believe that in order to verify that the steady-state value of the transfer function in the zero-frequency region, in their opinion, it is necessary to run the simulation for an infinite time. Such an answer casts doubt on the competence of the authors, and this article was written by a team of four authors. It is surprising that each of the four authors should have read the article before agreeing to publish it in their own name, among other things. It is surprising that four authors and two reviewers did not notice these errors. But it is even more surprising that a team of four authors claims that in order to verify that the two transfer functions coincide in the zero-frequency region, it will be necessary to run the simulation for an infinite time, which no one can do.

Well then, we will do the work that no one else can do. Maybe we will be able to teach someone. First, let us recall that in order to find out what the transfer function of any link is in the zero frequency region, it is enough to substitute the value into it.

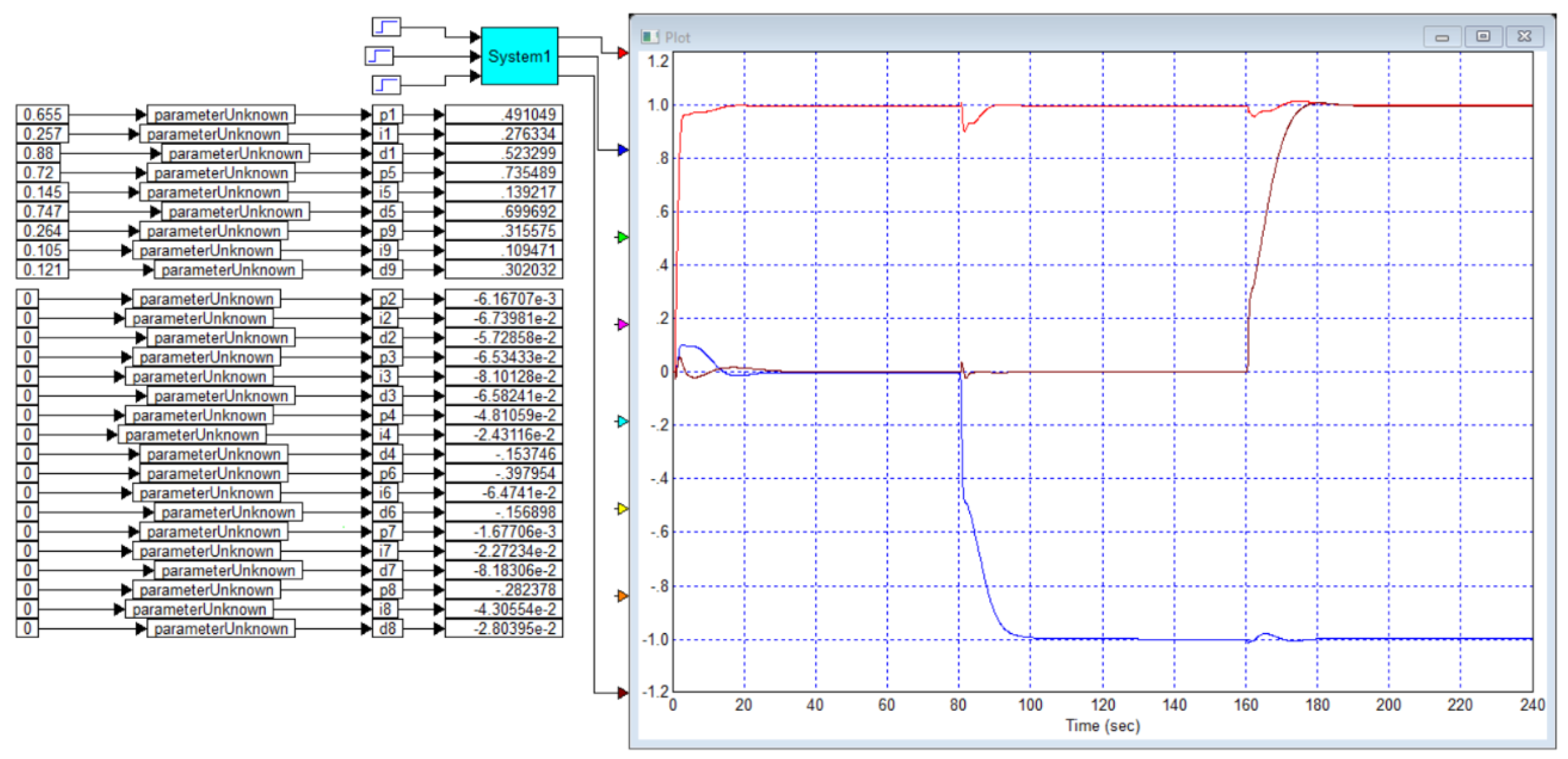

We have already done this above. We hope that dividing one number by another is not so difficult that there is no excuse for not doing it. Now, let us present the simulation result, as shown in Figure B 18. If the authors had used the coefficients from Table 8, they would have obtained a result from which it is quite obvious that the graphs do not match; they differ by approximately 10 times. After adjusting the specified coefficient, the simulation can be repeated. The result is shown in

Figure 19. This graph shows that simulating the process over a 30-second interval was enough to make sure that the static coefficients of the original transfer function and the model proposed for it do not significantly match.

Figure 18.

Graphs of the transient processes of the original transfer function and the model proposed for it from the publication [

64], the red line is the process at the output of the exact model, the blue line is the process at the output of the approximating model.

Figure 18.

Graphs of the transient processes of the original transfer function and the model proposed for it from the publication [

64], the red line is the process at the output of the exact model, the blue line is the process at the output of the approximating model.

Figure 19.

Transient process graphs of the corrected initial transfer function and the model proposed for it from the publication [

64], the red line is the process at the output of the exact model, the blue line is the process at the output of the approximating model: the discrepancy between the static coefficients is obvious; 30 seconds were enough for the simulation.

Figure 19.

Transient process graphs of the corrected initial transfer function and the model proposed for it from the publication [

64], the red line is the process at the output of the exact model, the blue line is the process at the output of the approximating model: the discrepancy between the static coefficients is obvious; 30 seconds were enough for the simulation.

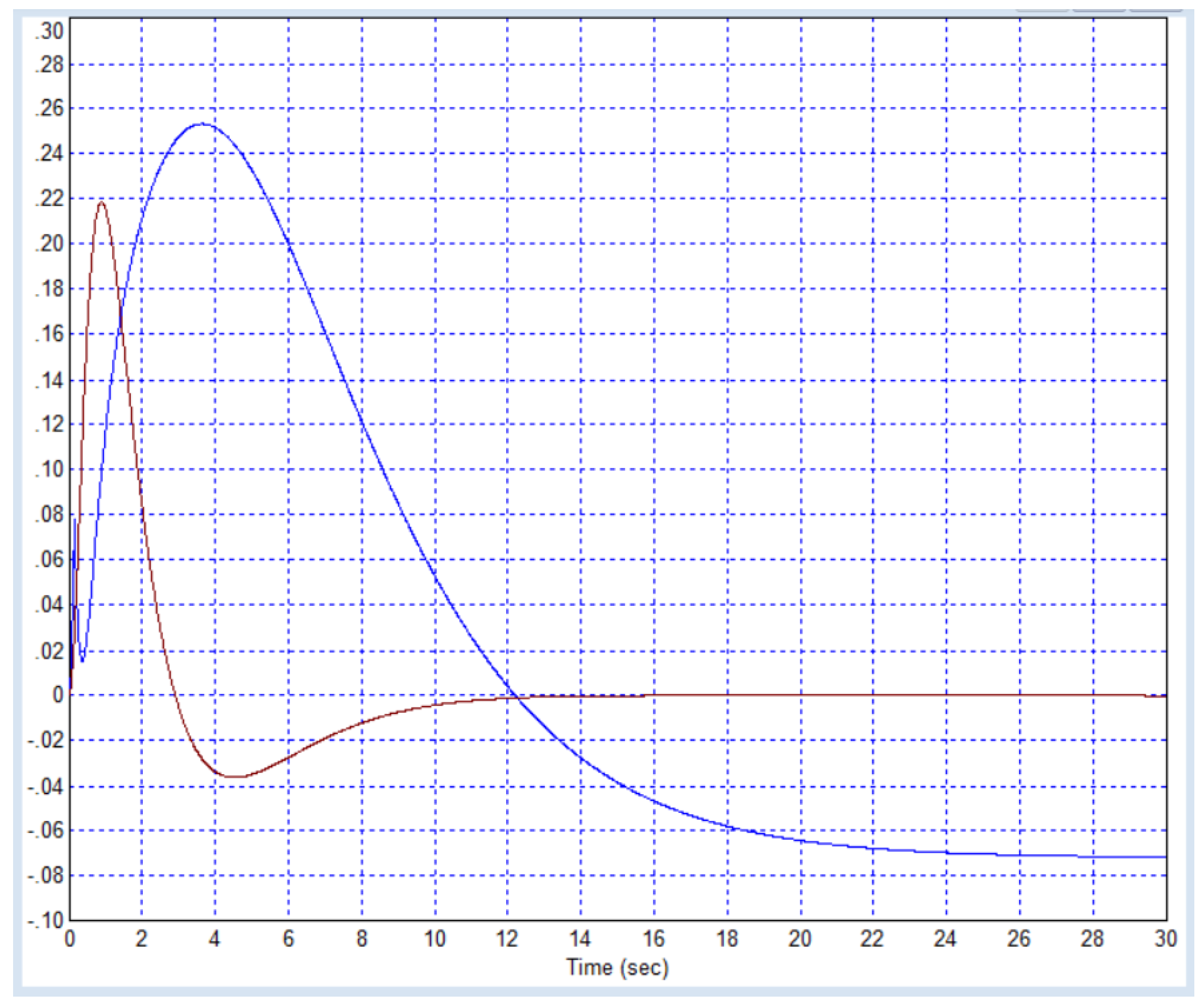

Figure 20.

Best approximation proposal: the red (exact) line is almost identical to the black one (our model proposal), and significantly different from the blue one (the approximation proposed in [

64].

Figure 20.

Best approximation proposal: the red (exact) line is almost identical to the black one (our model proposal), and significantly different from the blue one (the approximation proposed in [

64].

Figure 21.

Approximation error: blue line – approximation error proposed in the article, black line – approximation error obtained by manual selection based on the results of 15 tests (labor costs 10 minutes).

Figure 21.

Approximation error: blue line – approximation error proposed in the article, black line – approximation error obtained by manual selection based on the results of 15 tests (labor costs 10 minutes).

Conclusion 5. The method of numerical modeling and optimization is a simple and reliable tool, modeling with its help coincides with the results of reliable studies.

Conclusion 6. Numerical modeling allows us to identify errors in articles by other authors if they contain mathematical models of the object and the results of designing regulators.

Conclusion 7. In all cases, the controllers calculated using the numerical optimization method turn out to be better than the controllers published in the articles considered for the same objects.

Conclusion 8. The method of numerical optimization and numerical modeling is extremely easy to use, testing the main hypotheses takes little time, and the result is quite clear.

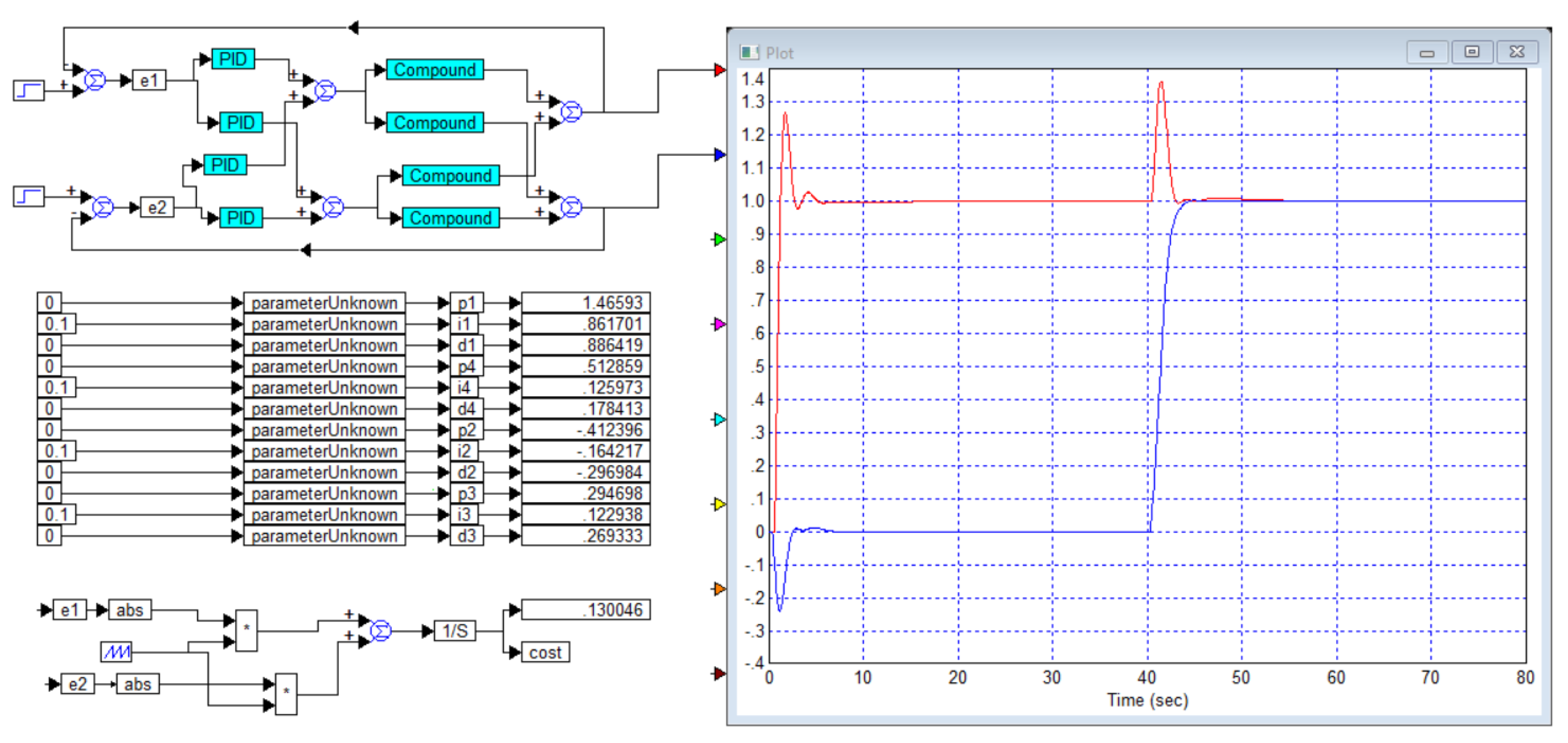

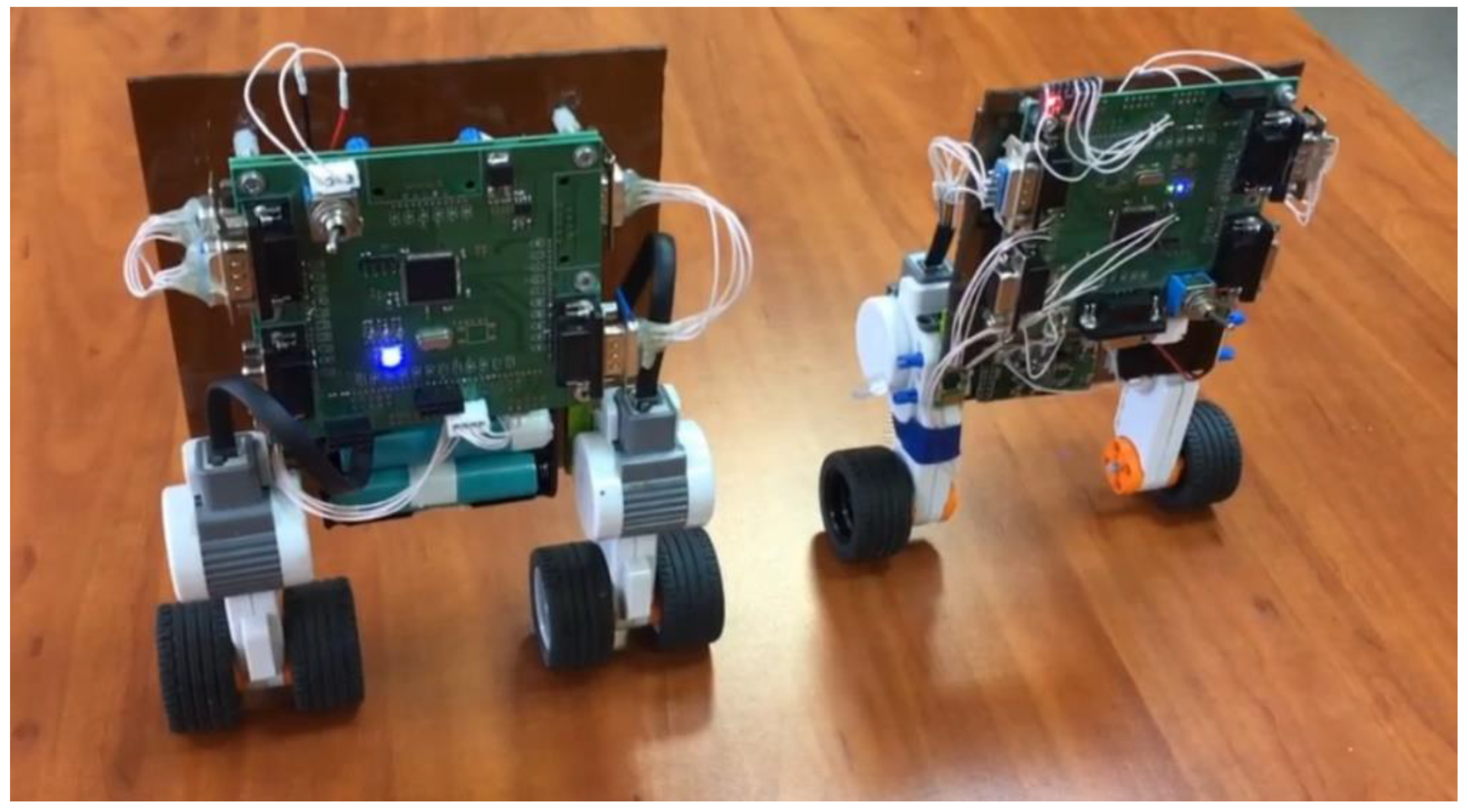

Numerical optimization has been used to calculate many controllers for practical and educational tasks. In particular, postgraduate student A. Yu. Ivoylov and senior lecturer V. G. Trubin designed and manufactured a compact balancing robot. The video at the link [

65] demonstrates the operation of two versions of this robot [

66,

67]. The robot on the left maintains balance, but makes some deviations around the equilibrium state. The robot on the right maintains balance without deviations, which is ensured by optimizing the PID controller under the supervision of one of the authors of this article.

Figure 22.

External view of two robots developed using the numerical optimization method of single-channel controllers [

65,

66,

67].

Figure 22.

External view of two robots developed using the numerical optimization method of single-channel controllers [

65,

66,

67].