Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 93B51

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theory

2.1. Aproach

2.3. Formulation of the Problem

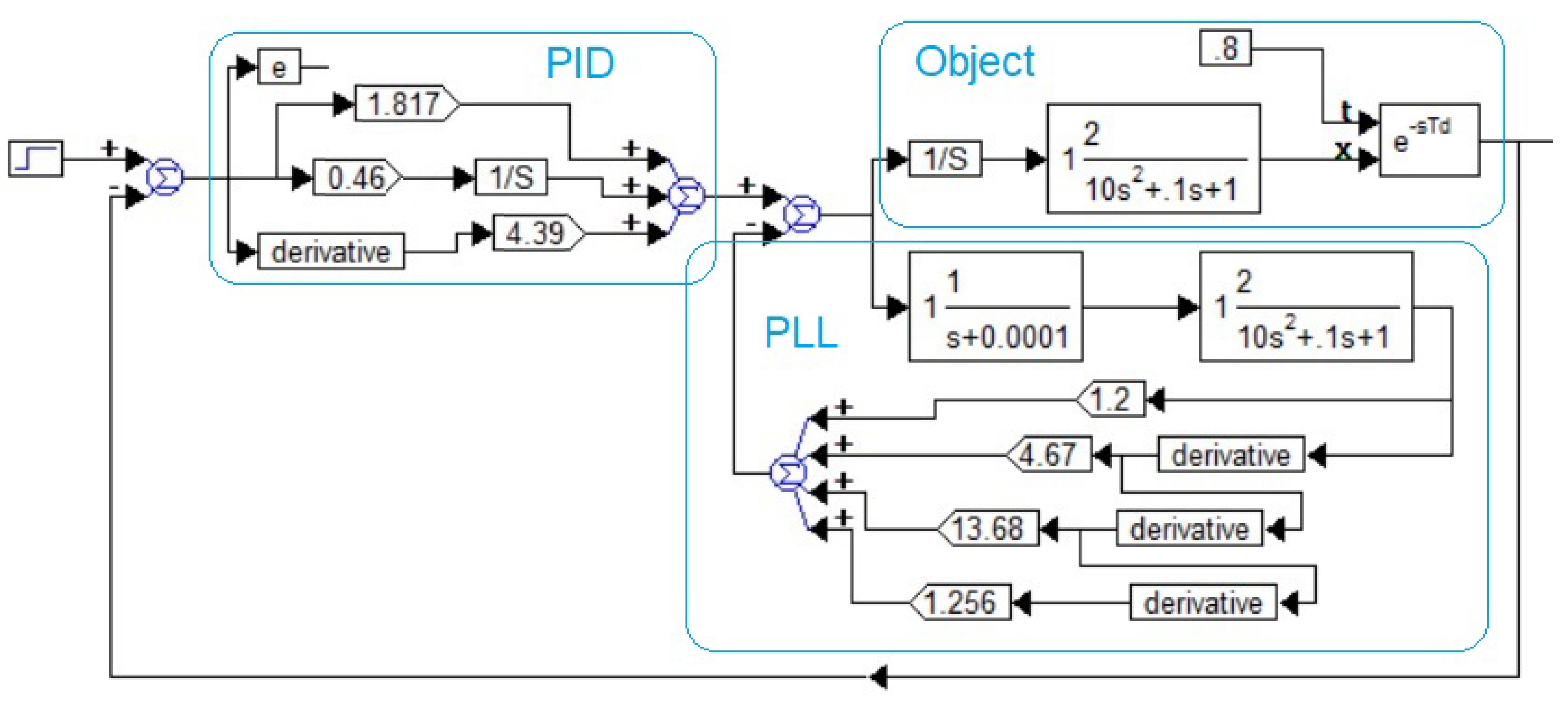

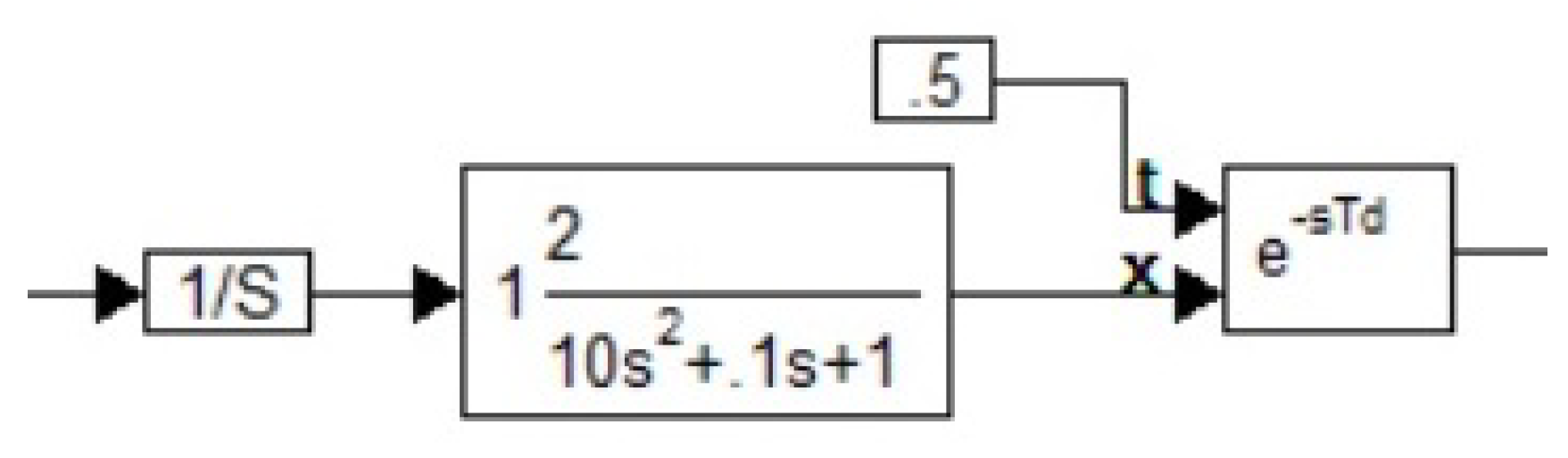

2.4. Method

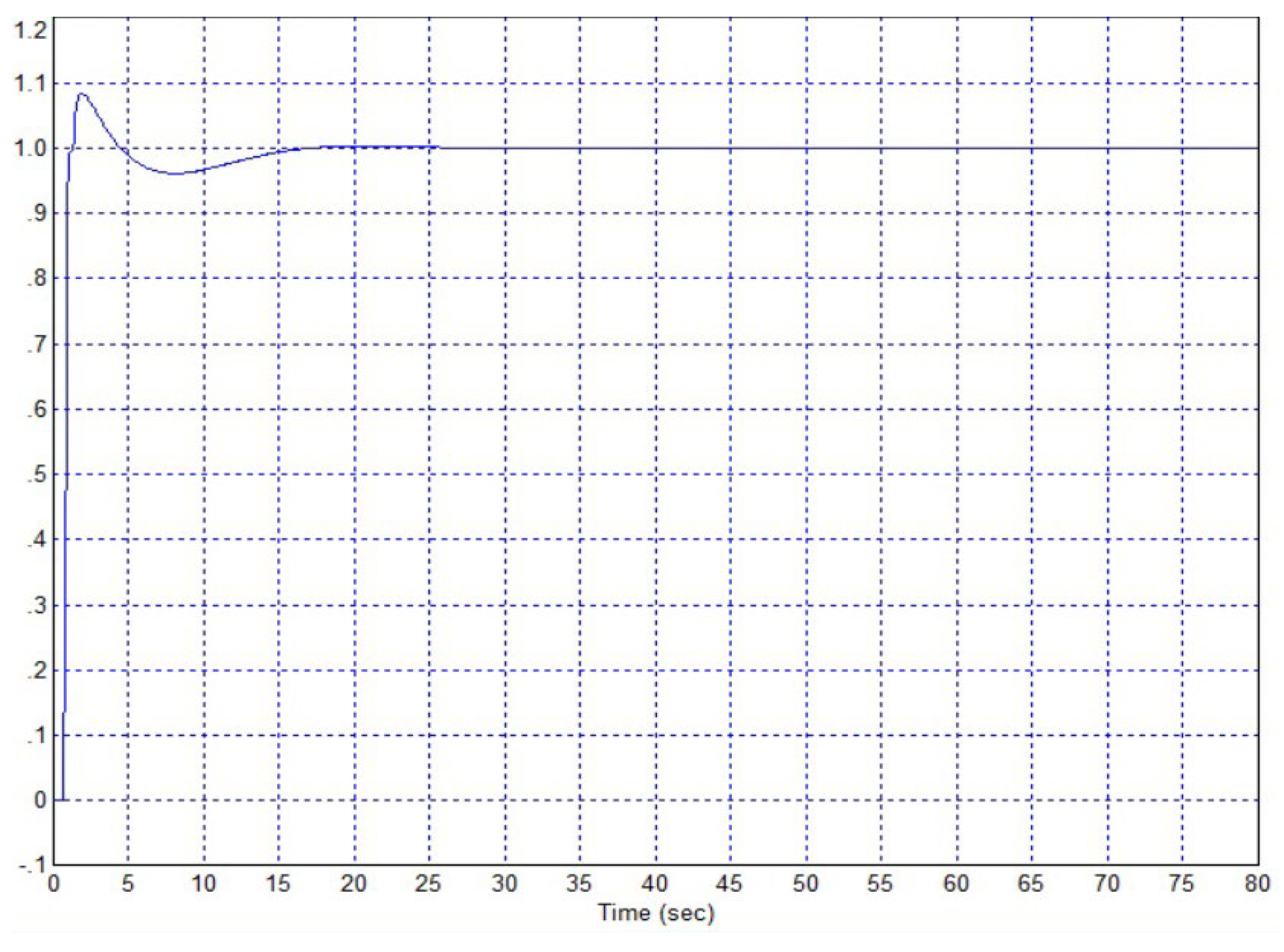

3. Results

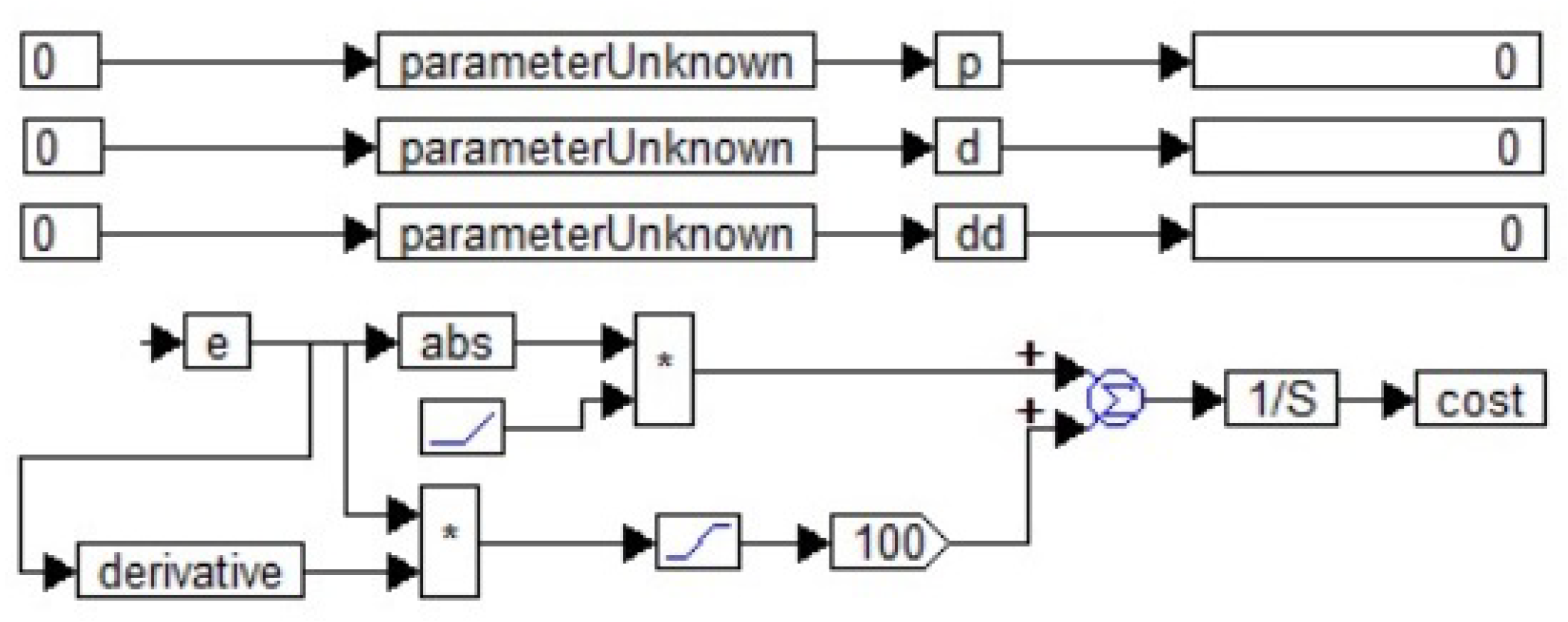

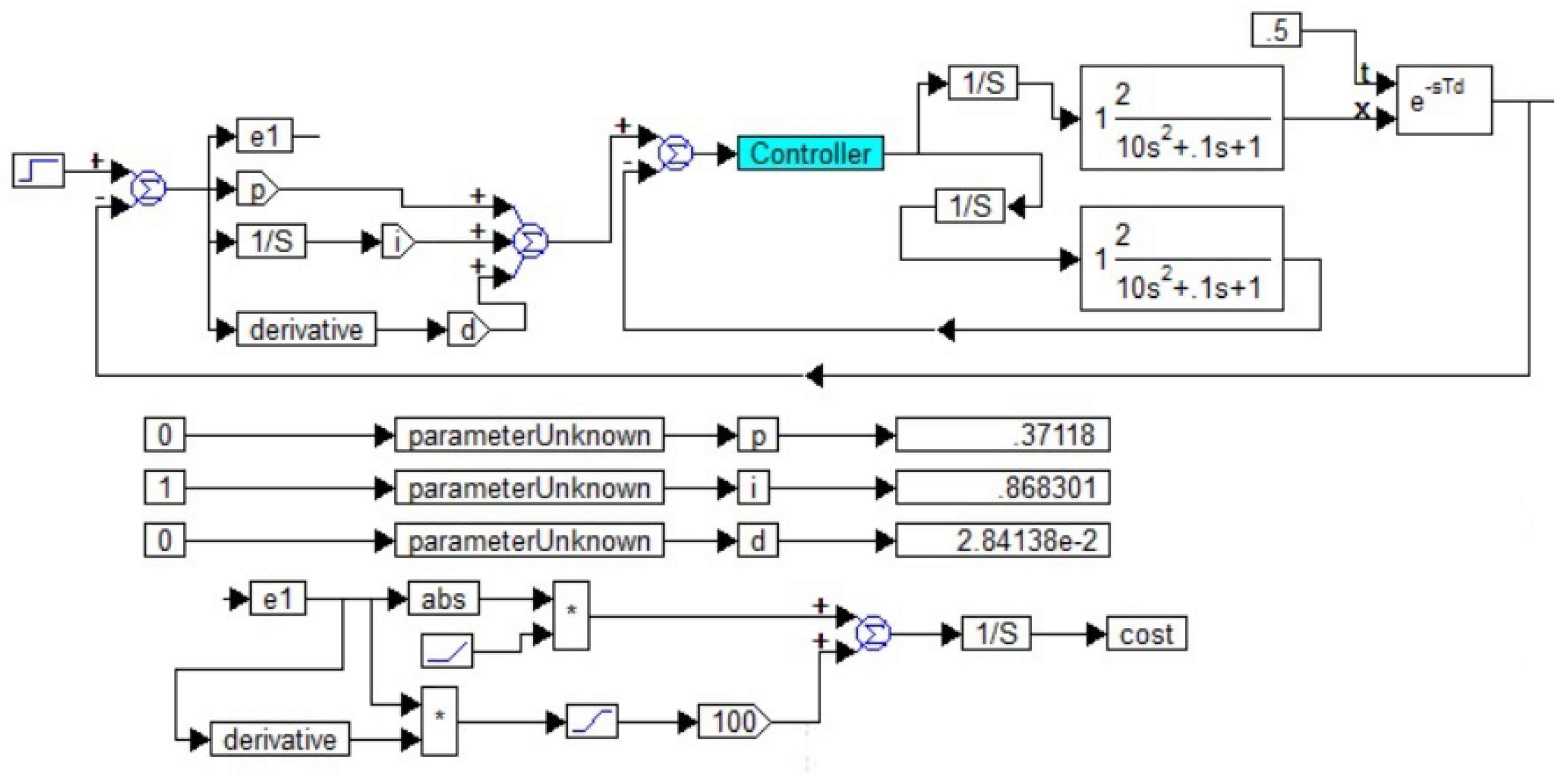

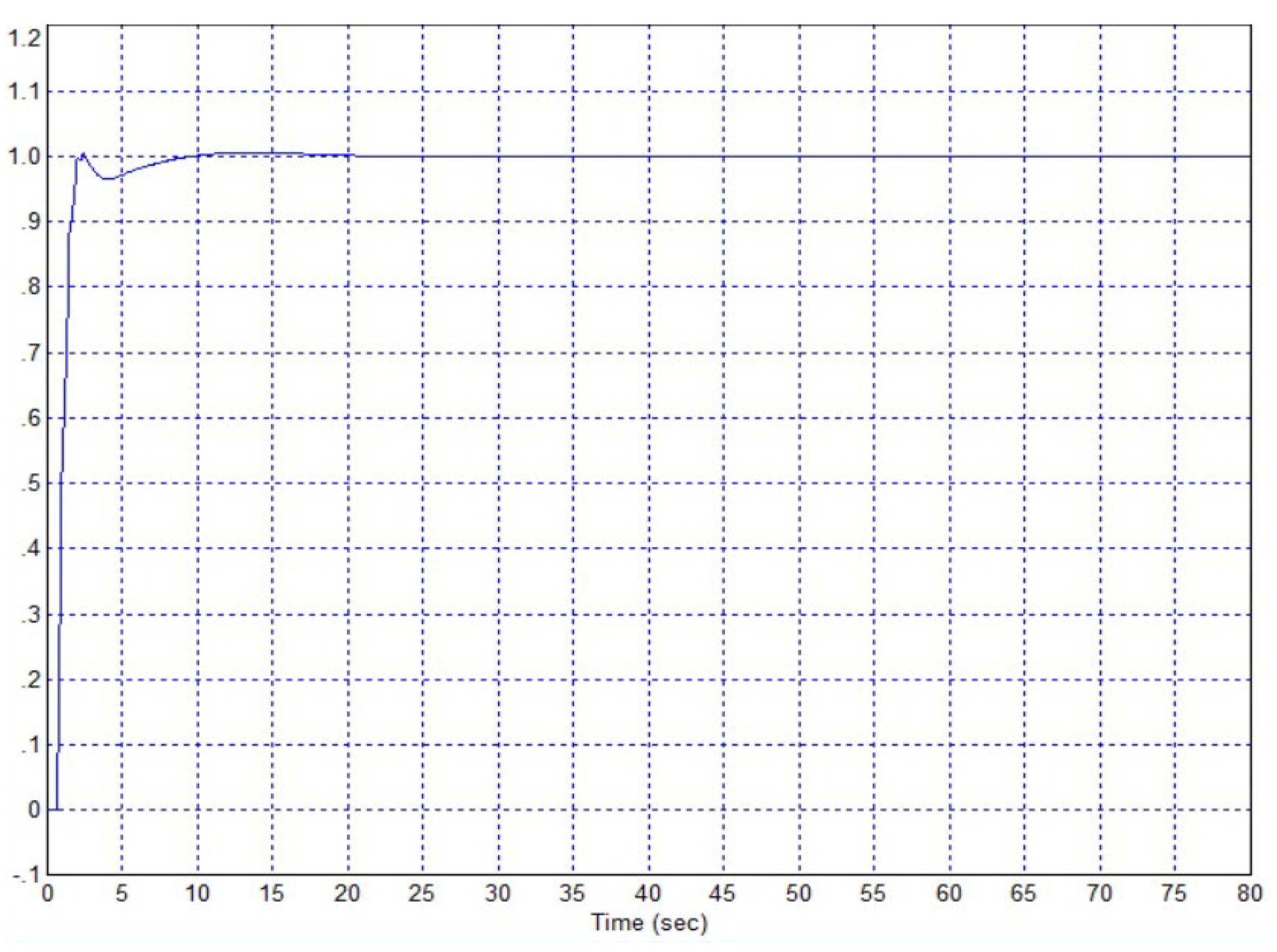

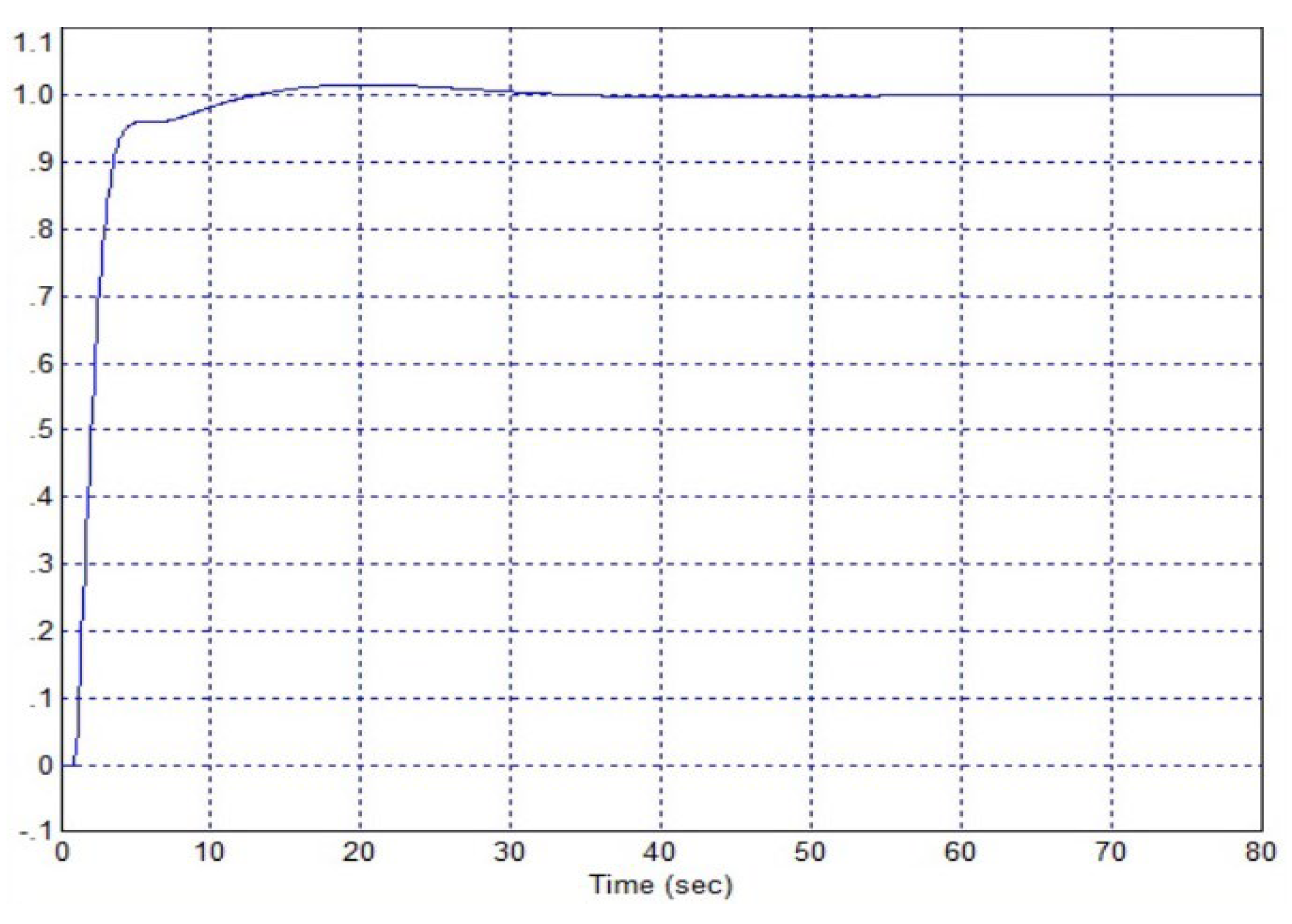

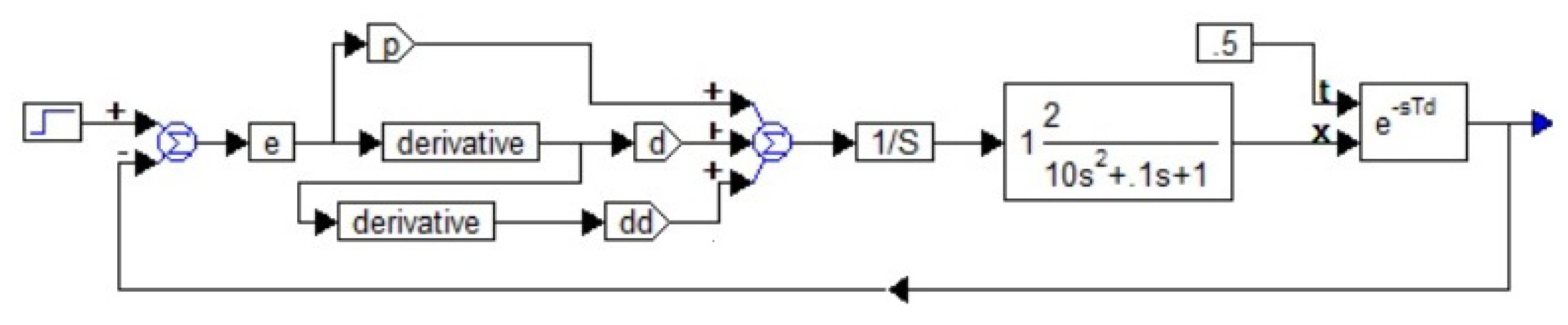

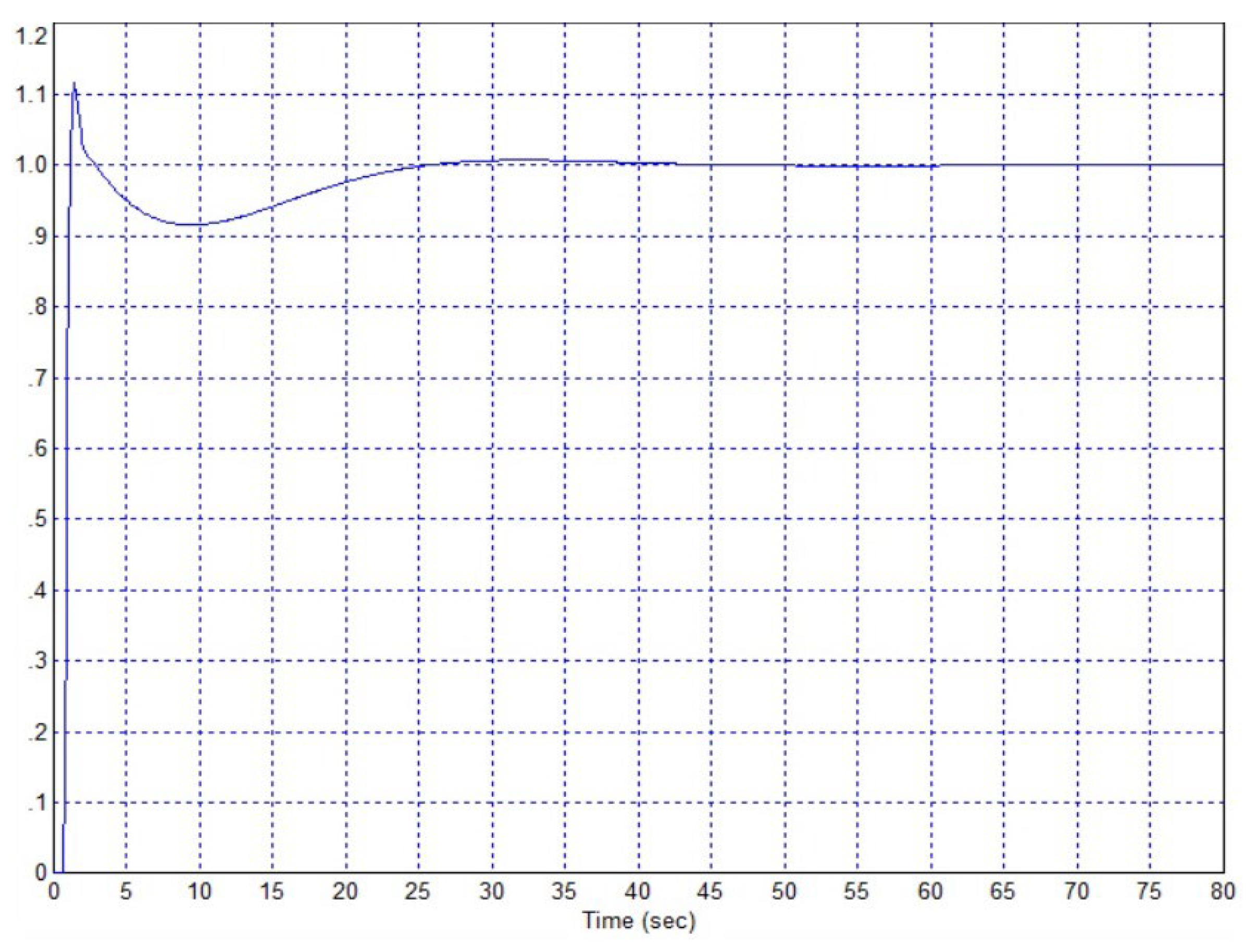

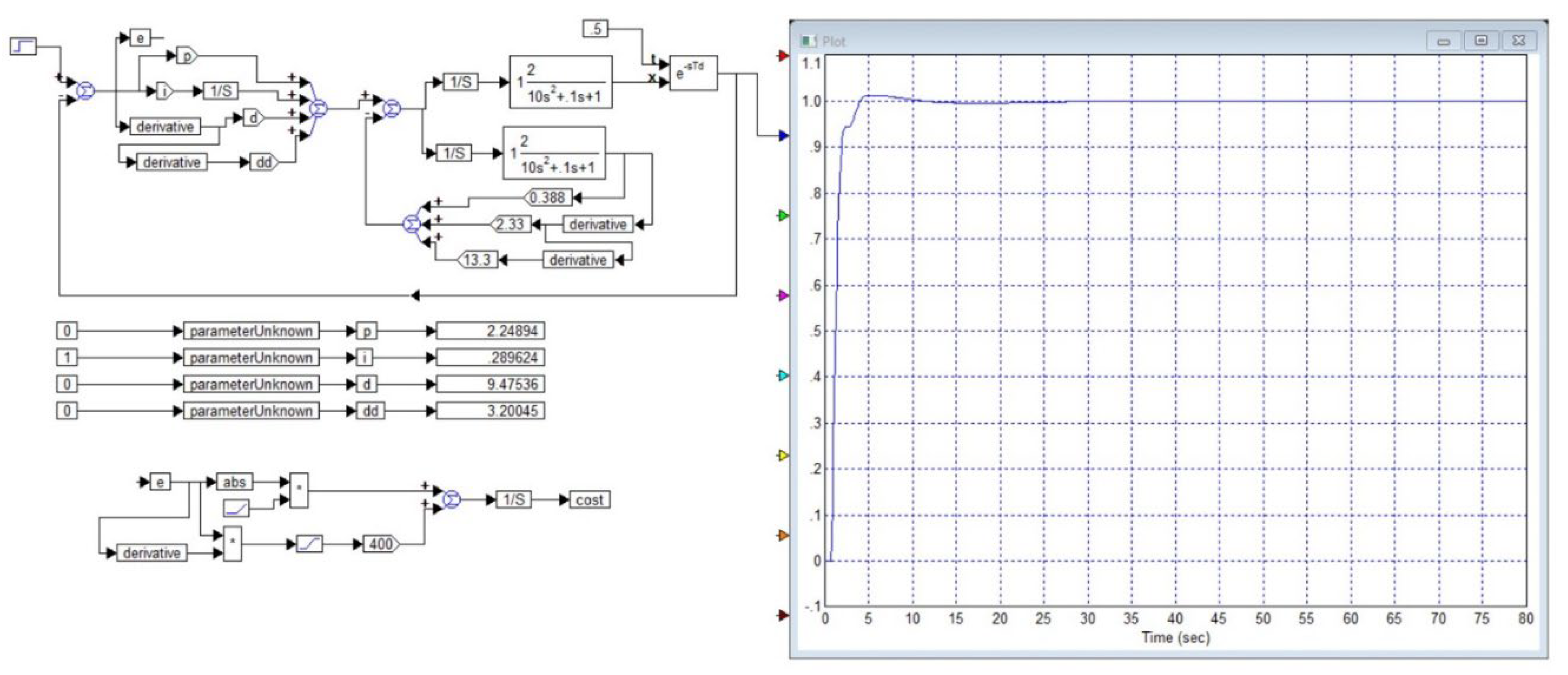

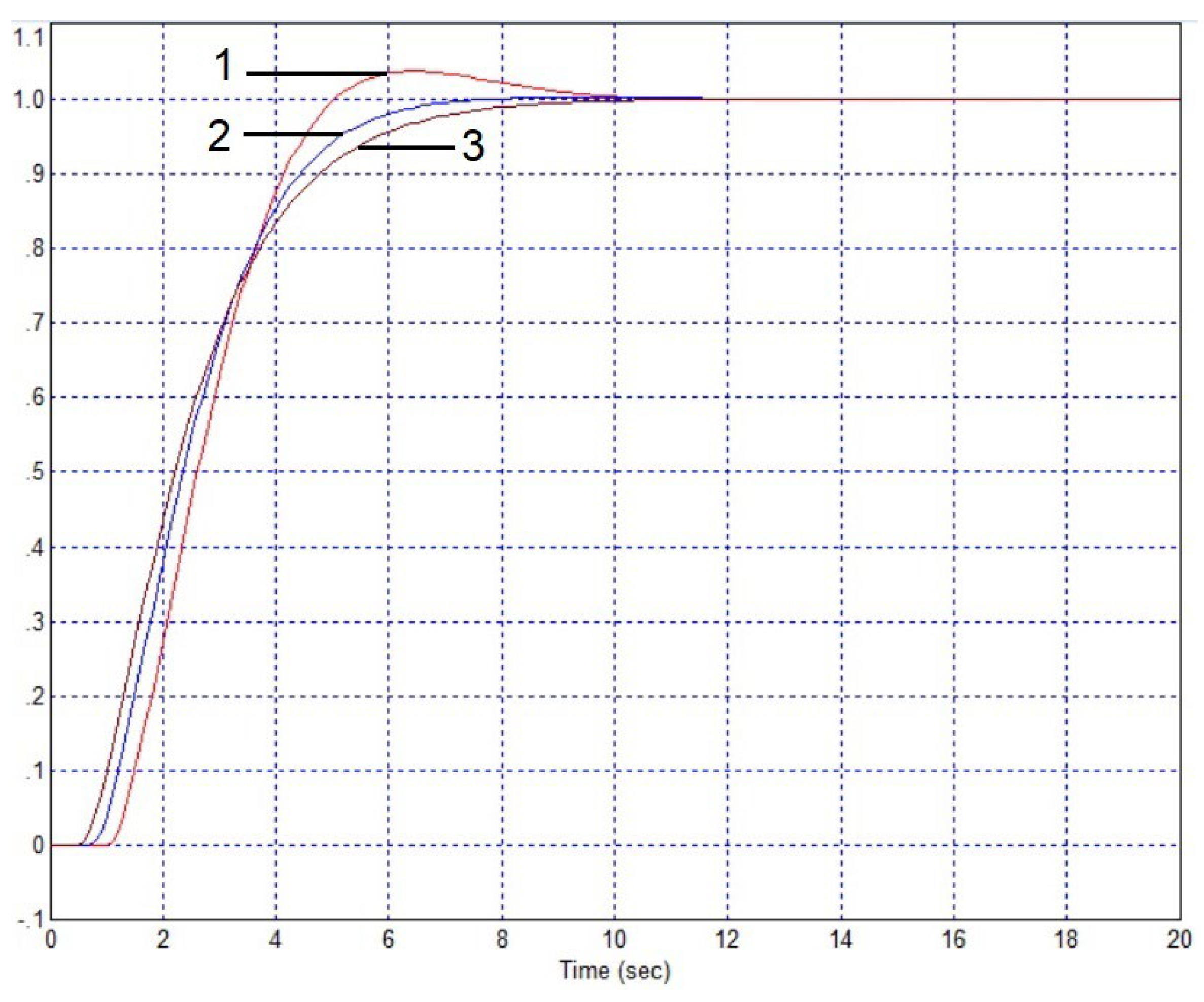

3.1. Results of the Firest Approach

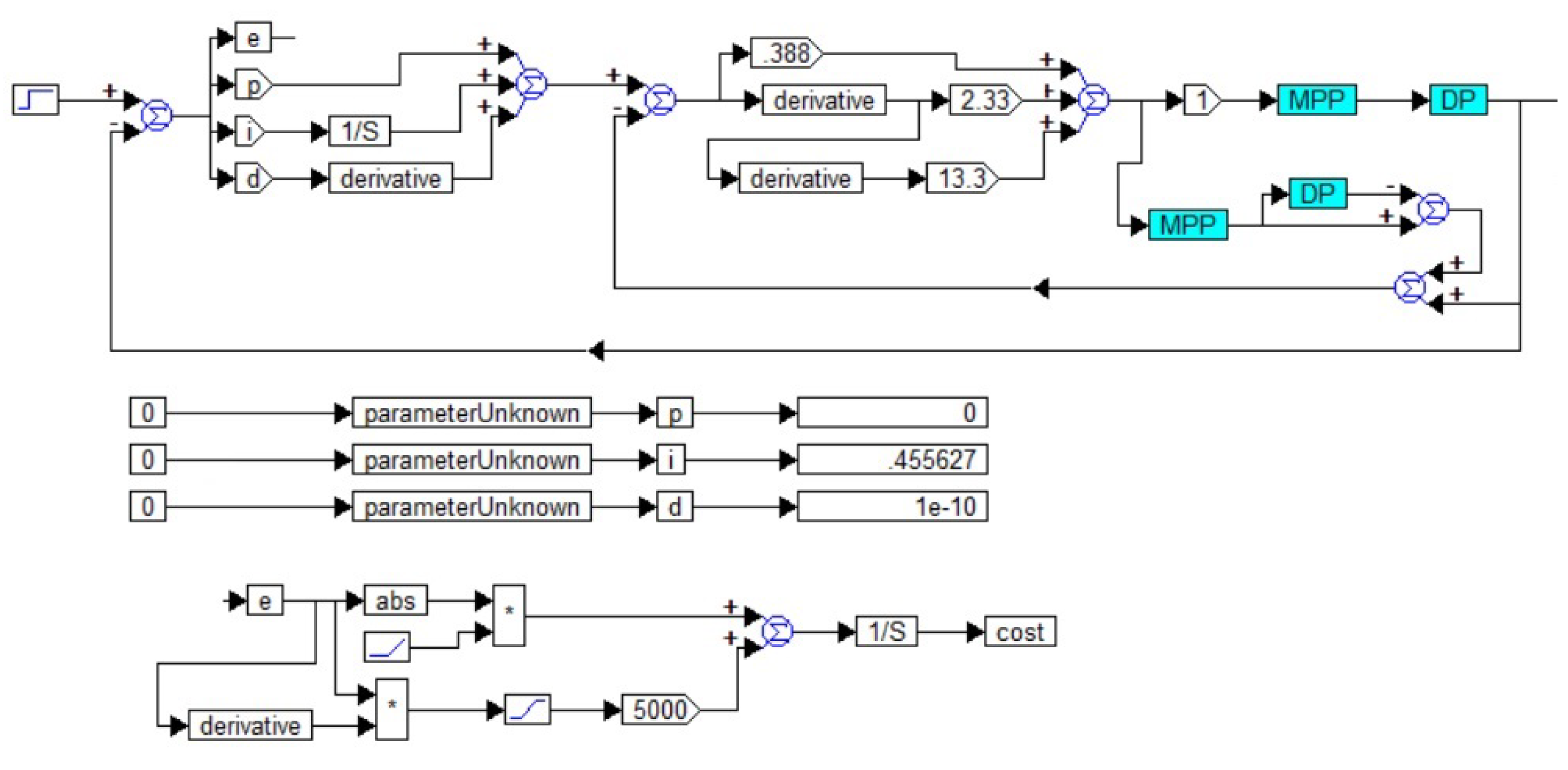

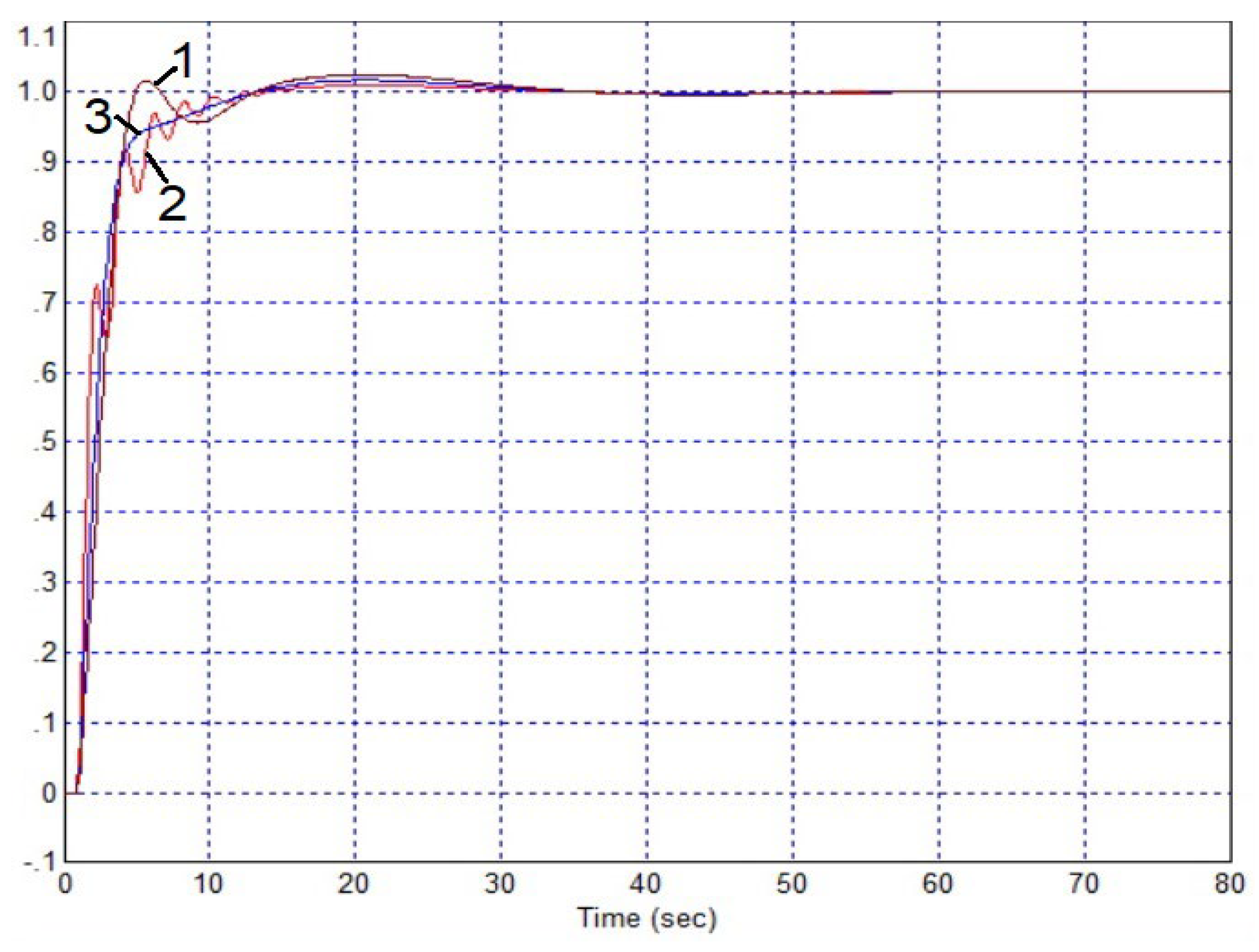

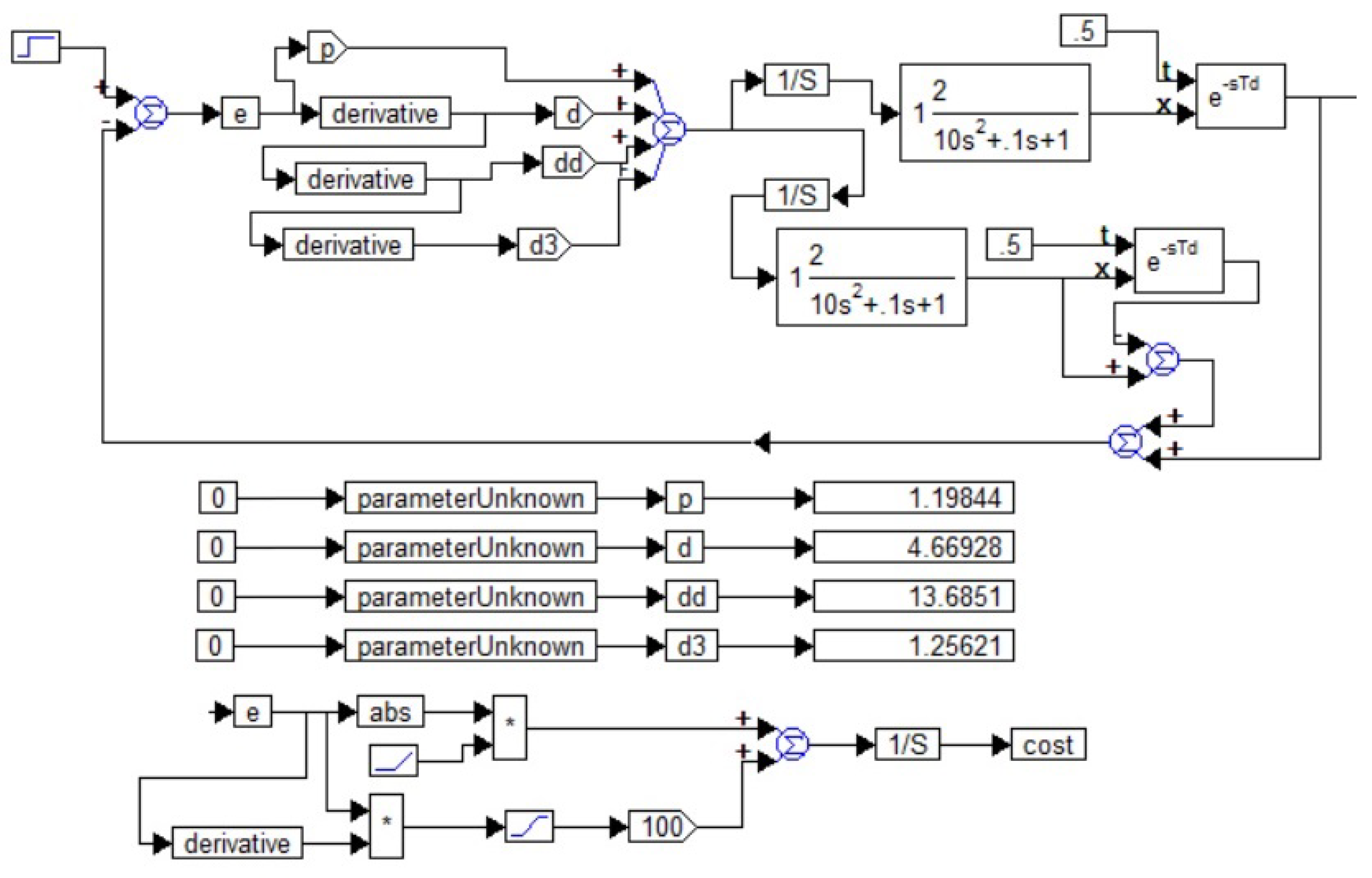

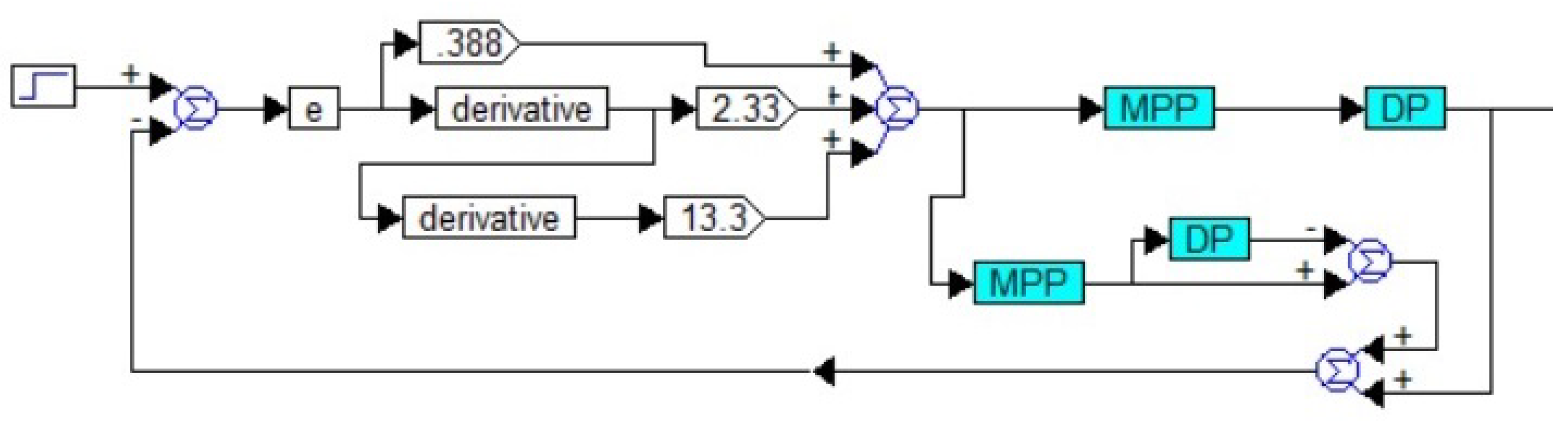

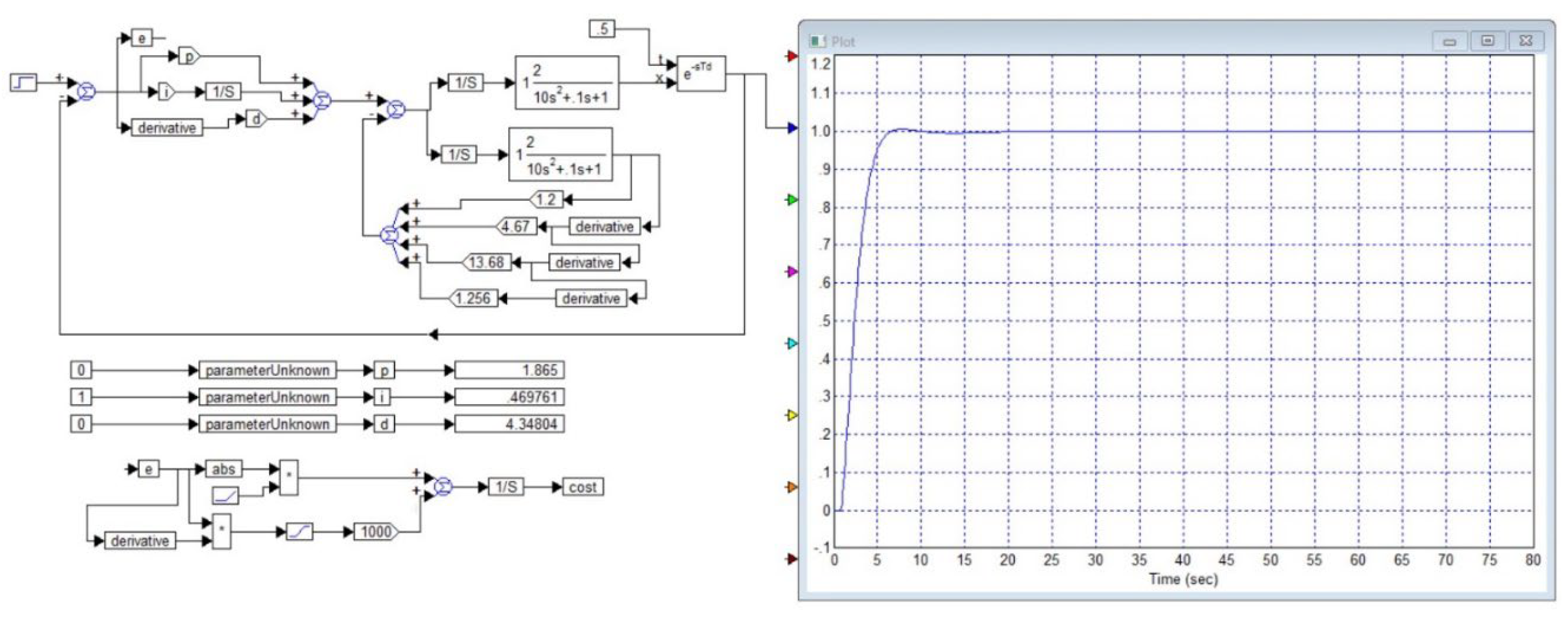

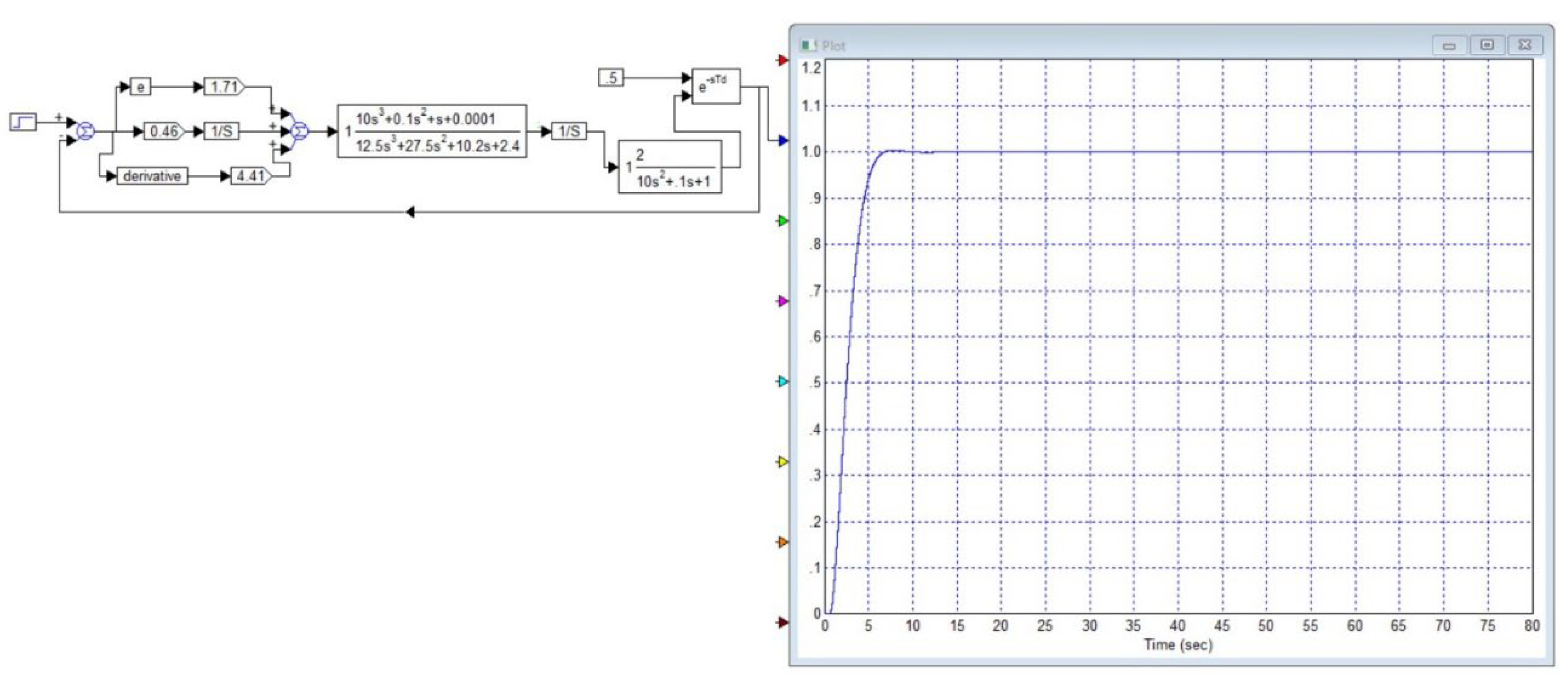

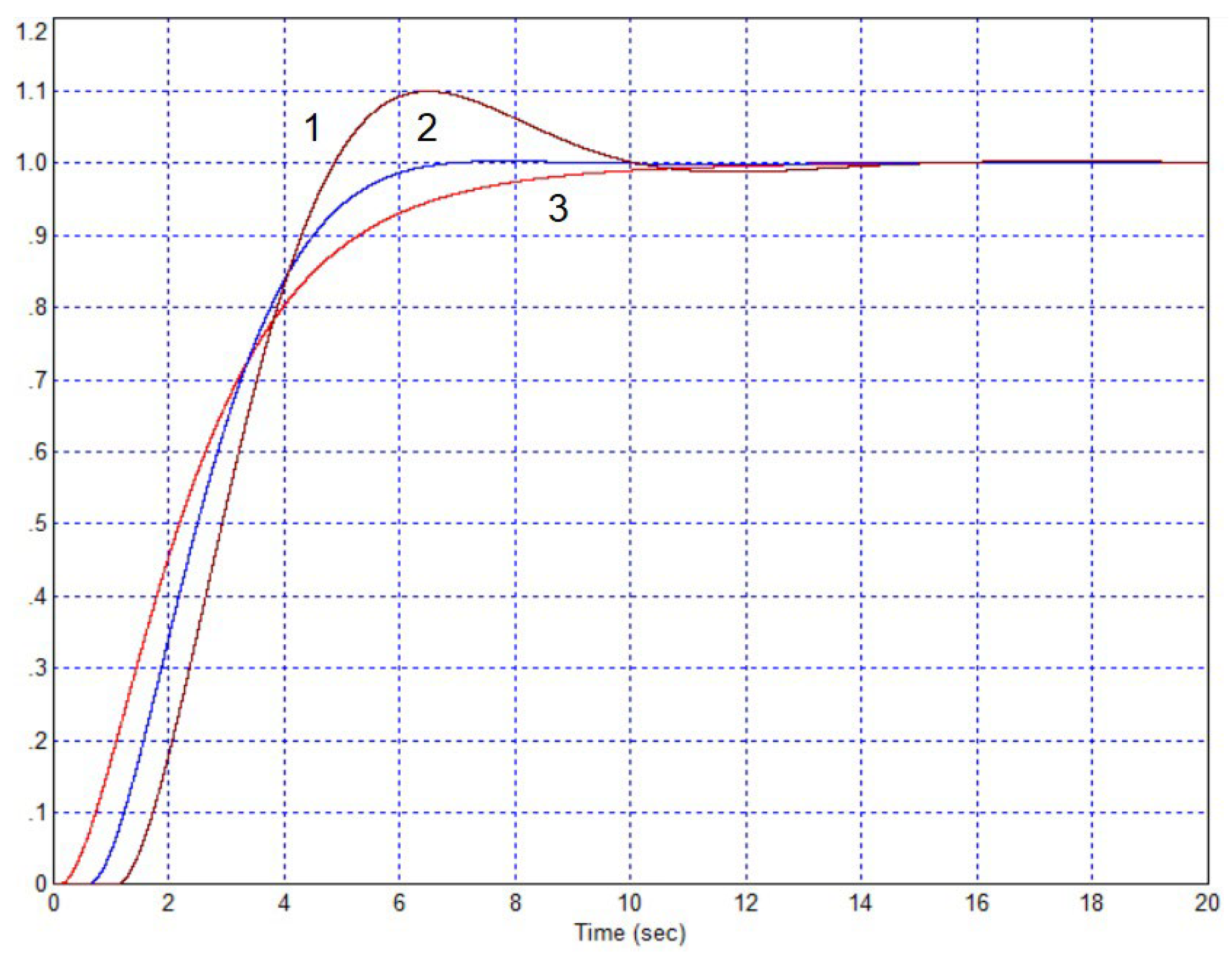

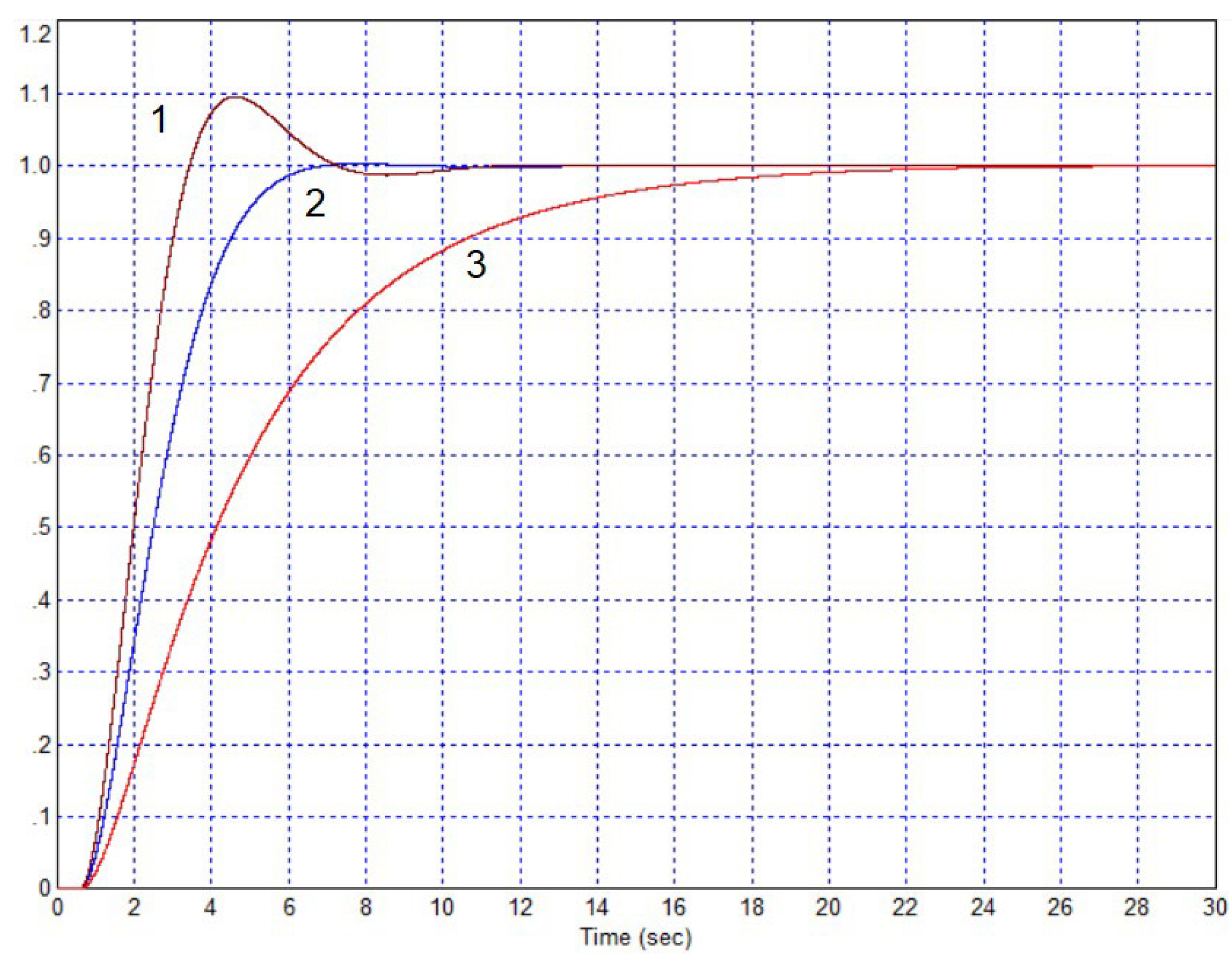

3.2. Applying Pseudo-Local Feedback

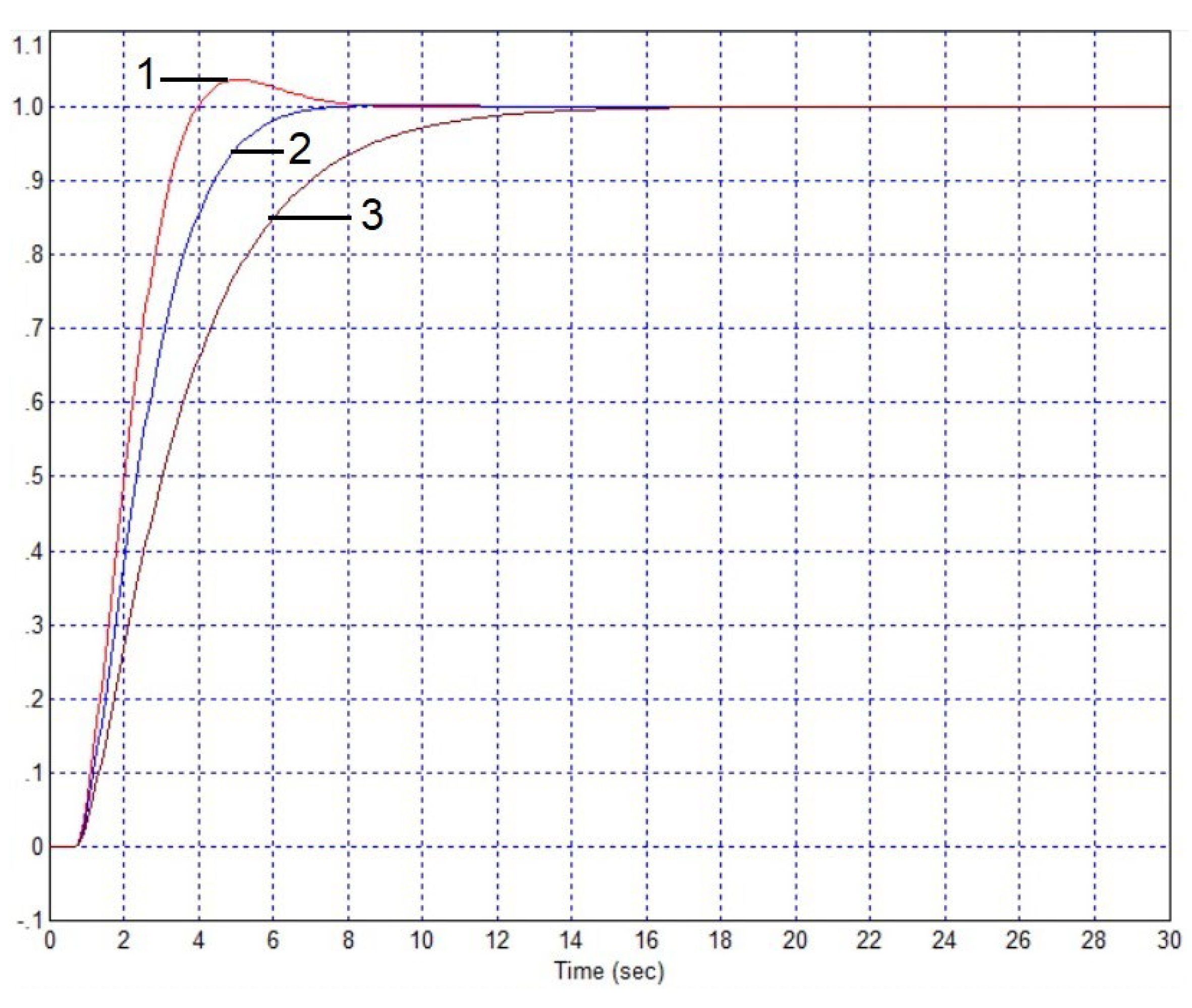

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- So, G.-B. Design of Linear PID Controller for Pure Integrating Systems with Time Delay Using Direct Synthesis Method. Processes 2022, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Su, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, F.; Yin, B. Online PID Tuning Strategy for Hydraulic Servo Control Systems via SAC-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning. Machines 2023, 11, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozański, K. Low Cost PID Controller for Student Digital Control Laboratory Based on Arduino or STM32 Modules. Electronics 2023, 12, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; He, T.; Zhu, G. Model-Assisted Online Optimization of Gain-Scheduled PID Control Using NSGA-II Iterative Genetic Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Xu, C.; Hao, L.; Yao, J.; Guo, R. Research on PID Parameter Tuning and Optimization Based on SAC-Auto for USV Path Following. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrančić, D.; Moura Oliveira, P.; Bisták, P.; Huba, M. Model-Free VRFT-Based Tuning Method for PID Controllers. Mathematics 2023, 11, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaa, M.Y.; Barambones, O.; Bencherif, A. A Novel Adaptive PID Controller Design for a PEM Fuel Cell Using Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum Enhanced by Whale Optimizer. Electronics 2022, 11, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; He, X.-L.; Gao, Z.-J. Adaptive PID Control and Its Application Based on a Double-Layer BP Neural Network. Processes 2021, 9, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz- Diaz, C.; del Muro-Cuéllar, B.; Duchén -Sánchez, G.; Márquez -Rubio, J. F.; Velasco-Villa, M. Observer-Based PID Control Strategy for the Stabilization of Delayed High Order Systems with up to Three Unstable Poles. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, O.; Campos, D.; Rico- Azagra, J.; Gil- Martinez, M.; Rojas, J.D.; Vilanova, R. Model-Based Optimization Approach for PID Control of Pitch–Roll UAV Orientation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božek, P.; Nikitin, Y. The Development of an Optimally-Tuned PID Control for the Actuator of a Transport Robot. Actuators 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zishan, F.; Akbari, E.; Montoya, O.D.; Giral-Ramírez, D.A.; Molina-Cabrera, A. Efficient PID Control Design for Frequency Regulation in an Independent Microgrid Based on the Hybrid PSO-GSA Algorithm. Electronics 2022, 11, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J.; Ruz, M.L.; Morilla, F.; Vázquez, F. Iterative Method for Tuning Multiloop PID Controllers Based on Single Loop Robustness Specifications in the Frequency Domain. Processes 2021, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, I.M.; Ababneh, O.Y.; Al-Nana, A.A.; Alshanti, W.G.; Alshorm, S.; Momani, S. A Numerical Implementation of Fractional-Order PID Controllers for Autonomous Vehicles. Axioms 2023, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İçmez, Y.; Can, M. S. Smith Predictor Controller Design Using the Direct Synthesis Method for Unstable Second-Order and Time-Delay Systems. Processes 2023, 11, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shirkhani, M.; Ahmed, E.M. Machine-Learning-Based Improved Smith Predictive Control for MIMO Processes. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskys, A. Switched-Delay Smith Predictor for the Control of Plants with Response-Delay Asymmetry. Sensors 2023, 23, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xin, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, X. Smith-Predictor-Based Design of Analytical PI-PD Control for Series Cascade Processes with Time Delay. Electronics 2023, 12, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huba, M.; Bistak, P.; Vrancic, D. 2DOF IMC and Smith-Predictor-Based Control for Stabilized Unstable First Order Time Delayed Plants. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, Y. Decoupling Adaptive Smith Prediction Model of Flatness Closed-Loop Control and Its Application. Processes 2020, 8, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Yu, M.; Xu, Y.; Ma, C.; Lai, H.; Chen, F.; Lin, H. An Improved PID Controller for the Compliant Constant-Force Actuator Based on BP Neural Network and Smith Predictor. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuong, V.L.; Vu, T.N.L.; Truong, N.T.N.; Jung, J. H. An Analytical Design of Simplified Decoupling Smith Predictors for Multivariable Processes. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Tan, W.; Hou, G. Tuning of PID/PIDD2 Controllers for Second-Order Oscillatory Systems with Time Delays. Electronics 2023, 12, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawwaz, M.A.; Bingi, K.; Ibrahim, R.; Devan, P.A.M.; Prusty, B.R. Design of PIDD αController for Robust Performance of Process Plants. Algorithm 2023, Algorithm 16 and Algorithm 437. [CrossRef]

- VA Zhmud. Inadmissible Extensions of Protected Provisions in the Field of Automation: on the Control of Objects with Non-Square Transfer Functions. Automatics & Software Engineering. 2022, No. 1 (39). P.129 – 142. (In Russian). http://jurnal.nips.ru/sites/default/files/AaSI-1-2022-11.pdf.

- VA Zhmud, AV Liapidevskiy. The Design of the Feedback Systems by Means of the Modeling and Optimization in the Program VisSim 5.6/6.0 // Proc. Of The 30th IASTED Conference on Modelling, Identification, and Control ~ AsiaMIC 2010 ~November 24 – 26, 2010 Phuket, Thailand. P. 27–32.

- Zhmud, V. Designing of complete multi-channel PD-regulators by numerical optimization with simulation / V. Zhmud, L. Dimitrov // International Siberian conference on control and communications (SIBCON–2015): proc., Omsk, 21–23 May, 2015. – Omsk: IEEE, 2015. – Art. 129 (6 p.). ISBN 978-1-4799-7102-2. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).