Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“Being born and growing up as a girl in a developing society like Nigeria is almost like a curse due to contempt and ignominy treatment received from the family, the school and the society at large” [1].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

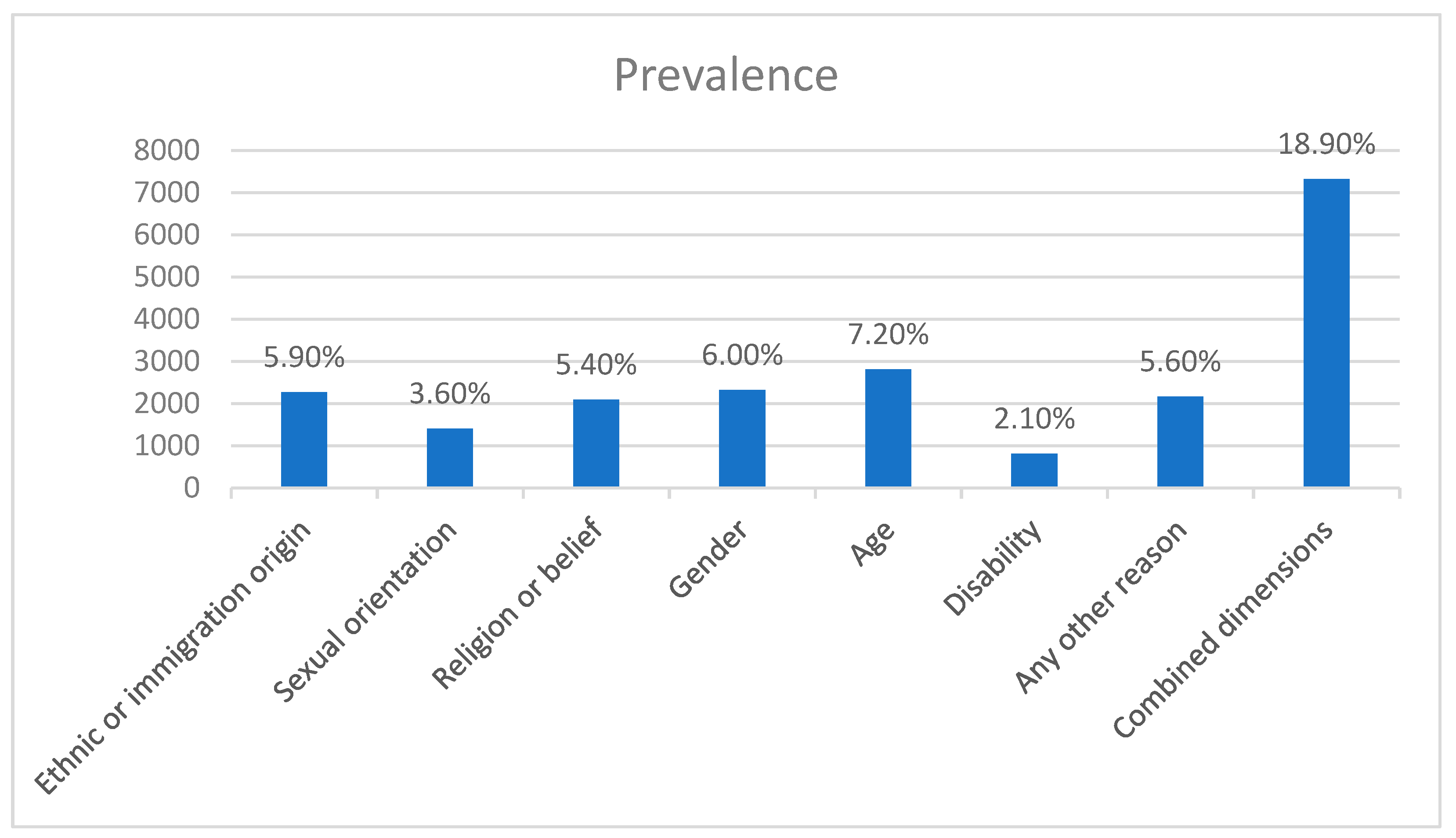

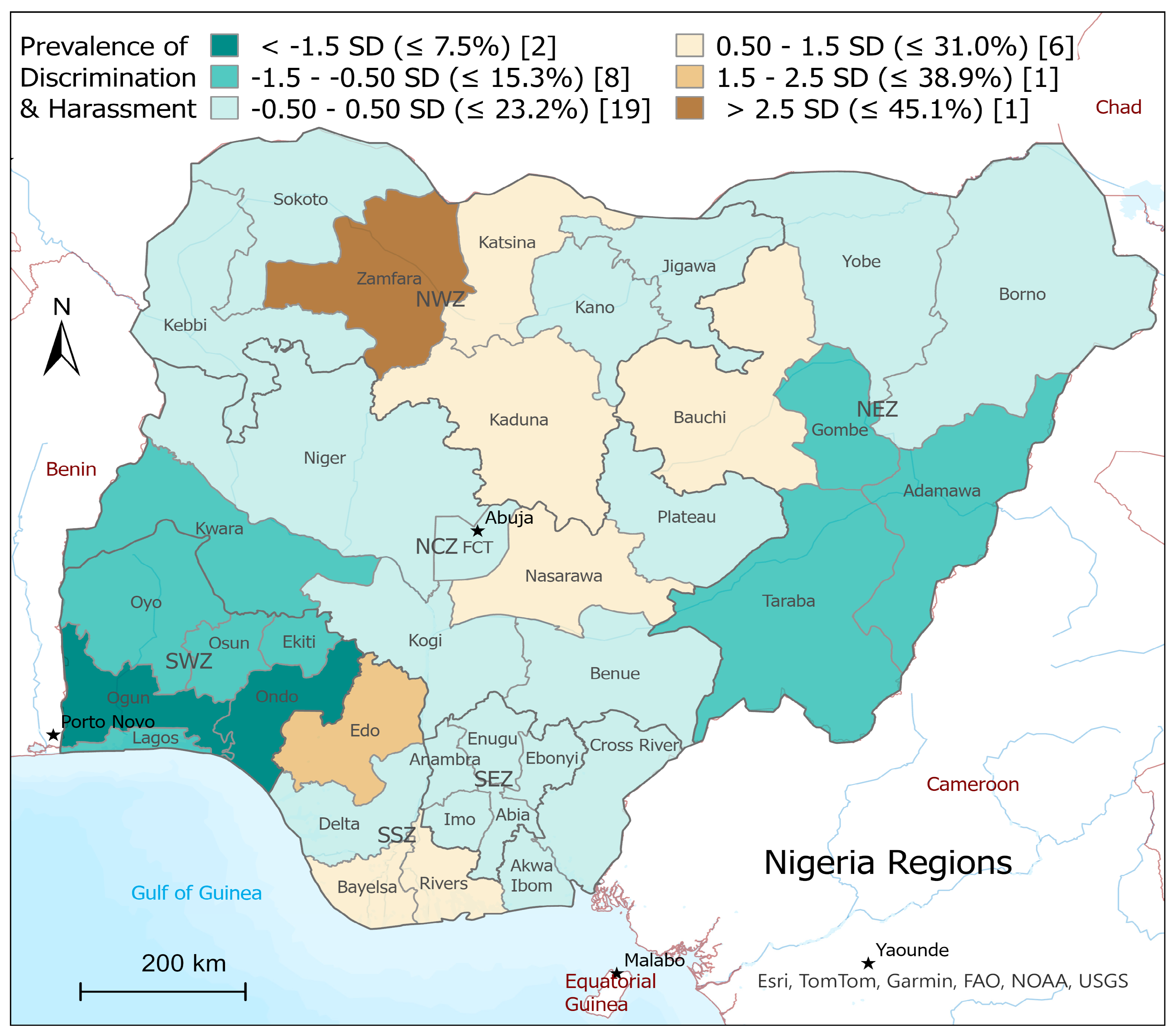

3.1. Prevalence and Sociodemographic Reasons for Discrimination and Harassment

3.2. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of Women

3.3. Chi-Square Analysis of Sociodemographic Characteristics of Discrimination and Harassment

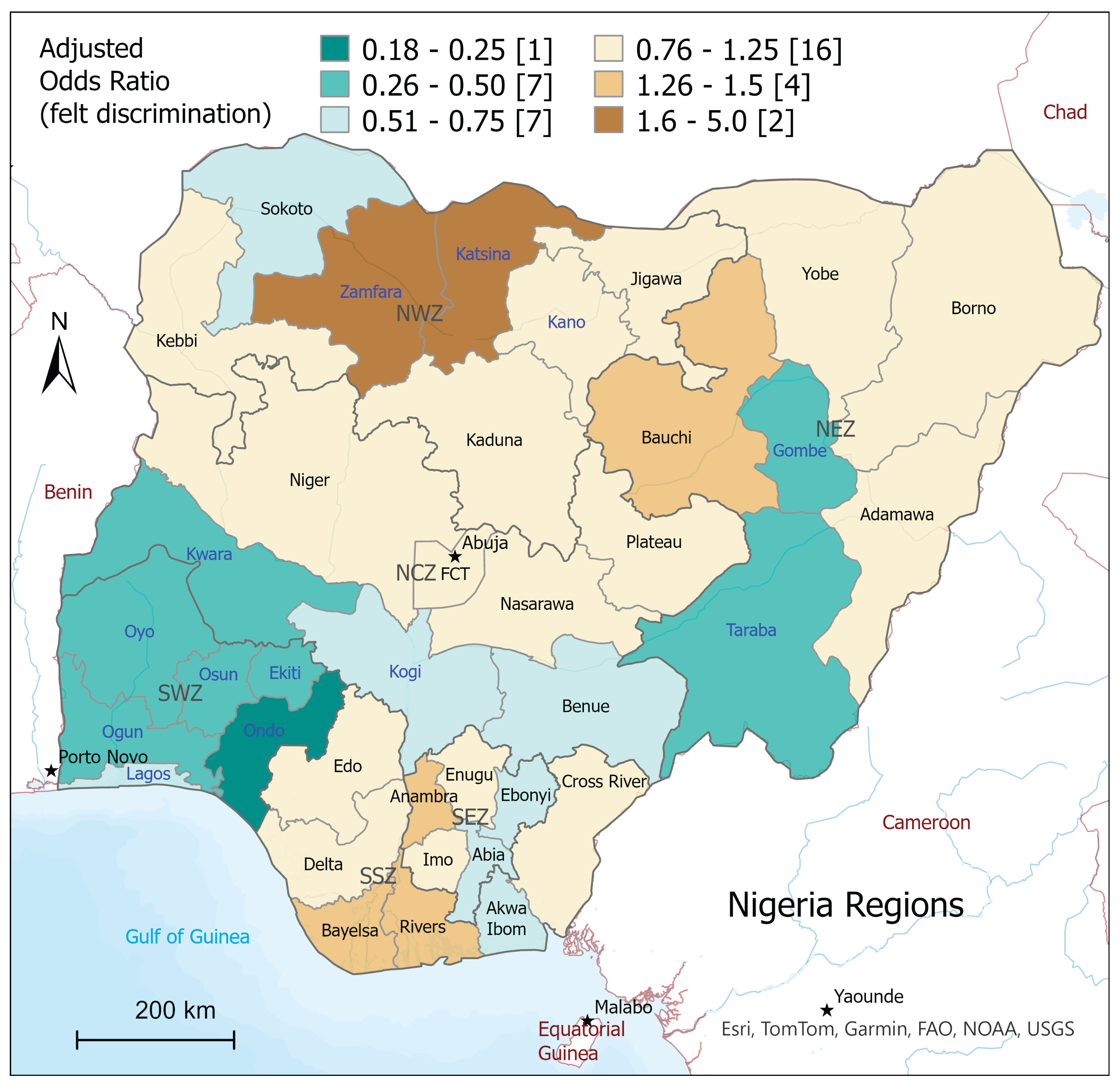

3.4. Predictors of Discrimination and Harassment Against Women in Nigeria

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alabi, T.; Bahah, M.; Alabi, S. The girl-child: A sociological view on the problems of girl-child education in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal 2014, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Soroosh, G. , Ninalowo, H., Hutchens, A., Khan, S. Nigeria country report, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, M.M. History of Nigeria. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History; 2024.

- Nnama-Okechukwu, C.U.; McLaughlin, H. Indigenous knowledge and social work education in Nigeria: made in Nigeria or made in the West? Social Work Education 2023, 42, 1476–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Gonzalez-Tamayo, L.A.; Olarewaju, A.D. An exploratory study on barriers and enablers for women leaders in higher education institutions in Mexico. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 2025, 53, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Okongwu, O.C. The need for a national legislation for the protection of women from workplace discrimination in Nigeria: Lessons from the existing UK legal framework. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 2024, 13582291251322180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. The value of the concept of discrimination in contexts of migration: the case of structural discrimination. Ethics & Global Politics 2024, 17, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.I.; Sultana, N.; Sultana, H. Prevalence and determinants of discrimination or harassment of women: Analysis of cross-sectional data from Bangladesh. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0302059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, V. The development of indirect discrimination law in India: Slow, uncertain, and unsteady. Indian Law Review 2024, 8, 306–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chua, T.C.; Saw, R.P.M.; Young, C.J. Discrimination, Bullying and Harassment in Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg 2018, 42, 3867–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis-Devis, J.; Pereira-Garcia, S.; Valencia-Peris, A.; Fuentes-Miguel, J.; Lopez-Canada, E.; Perez-Samaniego, V. Harassment Patterns and Risk Profile in Spanish Trans Persons. J Homosex 2017, 64, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.; Harcourt, P.; Harcourt, P. Prevalence and pattern of workplace violence and ethnic discrimination among workers in a tertiary institution in Southern Nigeria. Open Access Library Journal 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianakos, A.L.; Freischlag, J.A.; Mercurio, A.M.; Haring, R.S.; LaPorte, D.M.; Mulcahey, M.K.; Cannada, L.K.; Kennedy, J.G. Bullying, Discrimination, Harassment, Sexual Harassment, and the Fear of Retaliation During Surgical Residency Training: A Systematic Review. World J Surg 2022, 46, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. UNESCO launches the Global Alliance on Racism and Discriminations after the 4th edition of the Global Forum. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-launches-global-alliance-racism-and-discriminations-after-4th-edition-global-forum (accessed on April 22).

- World Justice, P. Discrimination is Getting Worse Globally. World Justice Project 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Senthilingam, M.; Mankarious, S.-G. Sexual harassment: How it stands around the globe. CNN, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bako, M.J.; Syed, J. Women’s marginalization in Nigeria and the way forward. Human Resource Development International 2018, 21, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olonade, O.Y.; Oyibode, B.O.; Idowu, B.O.; George, T.O.; Iwelumor, O.S.; Ozoya, M.I.; Egharevba, M.E.; Adetunde, C.O. Understanding gender issues in Nigeria: the imperative for sustainable development. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeliyi, T.; Oyewusi, L.; Epizitone, A.; Oyewusi, D. Analysing factors influencing women unemployment using a random forest model. Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences; Vol. 60, Issue Autumn/Winter 2022.

- Bakari, S.; Leach, F. Hijacking equal opportunity policies in a Nigerian college of education: The micropolitics of gender. In Proceedings of the Women's Studies International Forum; 2007; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, N. Experience of sexual harassment at work by female employees in a Nigerian work environment. Journal of Human Ecology 2010, 30, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para-Mallam, F.J. Promoting gender equality in the context of Nigerian cultural and religious expression: beyond increasing female access to education. Compare 2010, 40, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udu, E.A.; Uwadiegwu, A.; Eseni, J.N. Evaluating the enforcement of the rights of Women under the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 1979: The Nigerian experience. Beijing L. Rev. 2023, 14, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa, O.A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Frimpong, J.B.; Seidu, A.A.; Tessema, Z.T. Spatial distribution and predictors of intimate partner violence among women in Nigeria. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benebo, F.O.; Schumann, B.; Vaezghasemi, M. Intimate partner violence against women in Nigeria: a multilevel study investigating the effect of women's status and community norms. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okenwa-Emegwa, L.; Lawoko, S.; Jansson, B. Attitudes toward physical intimate partner violence against women in Nigeria. Sage Open 2016, 6, 2158244016667993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewunmi, A. The promotion of sexual equality and non-discrimination in the workplace: A Nigerian perspective. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 2013, 13, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aborisade, R.A. “At your service”: Sexual harassment of female bartenders and its acceptance as “norm” in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2022, 37, NP6557–NP6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L. Sexual Harassment Law in the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union: Discriminatory Wrongs and Dignitary Harms. Common Law World Review 2007, 36, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, S.; King, A. LGBT discrimination, harassment and violence in Germany, Portugal and the UK: A quantitative comparative approach. Current Sociology 2023, 71, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Sarker, M.M.R.; Chakma, S. Individual and community-level factors associated with discrimination among women aged 15-49 years in Bangladesh: Evidence based on multiple indicator cluster survey. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscigno, V.J. Discrimination, sexual harassment, and the impact of workplace power. Socius 2019, 5, 2378023119853894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Social Epidemiology of Perceived Discrimination in the United States: Role of Race, Educational Attainment, and Income. Int J Epidemiol Res 2020, 7, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnull, E.; Kanjilal, M.; Khasteganan, N. Safer Street 4: Violence against women and girls and the night-time economy in Telford and Wrekin. 2024.

- Bastomski, S.; Smith, P. Gender, fear, and public places: How negative encounters with strangers harm women. Sex Roles 2017, 76, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpin, J.; Papadopoulos, C.; Puthussery, S. The prevalence of domestic violence among pregnant women in Nigeria: a systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2020, 21, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- AMINU, T.; IBRAHIM, A. Instigators in Radicalisation of the Upsurge Trends of Armed Banditry in Zamfara State, 2019-2024. International Journal of Social Science Research and Anthropology 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

| Individual-level factors | ||

| Age | ||

| 15-24 | 14821 | 38.2 |

| 25-34 | 11264 | 29.0 |

| 35-49 | 12722 | 32.8 |

| Education | ||

| None | 10303 | 26.6 |

| Primary | 5300 | 13.7 |

| Junior secondary | 3386 | 8.7 |

| Senior secondary | 14164 | 36.5 |

| Higher/tertiary | 5647 | 14.6 |

| Missing/DK | 5 | 0.0 |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest | 6870 | 17.7 |

| Second | 7239 | 18.7 |

| Middle | 7562 | 19.5 |

| Fourth | 8308 | 21.4 |

| Richest | 8828 | 22.7 |

| Marital/Union status of woman | ||

| Currently married/in union | 23928 | 61.7 |

| Formerly married/in union | 2068 | 5.3 |

| Never married/in union | 12785 | 32.9 |

| Missing/DK | 24 | 0.1 |

| Ethnicity of household head | ||

| Hausa Igbo |

9891 | 25.5 |

| 6010 | 15.5 | |

| Fulani | 2520 | 6.5 |

| Kanuri | 748 | 1.9 |

| Ijaw | 658 | 1.7 |

| Tiv | 922 | 2.4 |

| Ibibio | 814 | 2.1 |

| Edo | 700 | 1.8 |

| Other | 9808 | 25.3 |

| Feeling safe at home alone after dark | ||

| Very safe | 10772 | 27.8 |

| Safe | 19639 | 50.6 |

| Unsafe | 6138 | 15.8 |

| Very unsafe | 1216 | 3.1 |

| Never alone after dark | 1035 | 2.7 |

| No response | 5 | 0.0 |

| Ever circumcised | ||

| Yes | 5863 | 15.1 |

| No | 15903 | 41.0 |

| DK | 1486 | 3.8 |

| No response | 11 | 0.0 |

| Missing System | 15543 | 40.1 |

| Able to get pregnant | ||

| Yes | 23058 | 59.4 |

| No | 3009 | 7.8 |

| DK | 1350 | 3.5 |

| No response | 148 | 0.4 |

| Missing system | 11241 | 29.0 |

| Estimation of overall happiness | ||

| Very happy | 16451 | 42.4 |

| Somewhat happy | 14215 | 36.6 |

| Neither happy nor unhappy | 5335 | 13.7 |

| Somewhat unhappy | 1913 | 4.9 |

| Very unhappy | 837 | 2.2 |

| No response | 55 | 0.1 |

| Community-level factors | ||

| Area | ||

| Urban | 17805 | 45.9 |

| Rural | 21001 | 54.1 |

| Region | ||

| Abia | 708 | 1.8 |

| Adamawa | 886 | 2.3 |

| Akwa Ibom | 885 | 2.3 |

| Anambra | 1259 | 3.2 |

| Bauchi | 1350 | 3.5 |

| Bayelsa | 462 | 1.2 |

| Benue | 1149 | 3.0 |

| Borno | 1027 | 2.6 |

| Cross River | 827 | 2.1 |

| Delta | 1036 | 2.7 |

| Ebonyi | 684 | 1.8 |

| Edo | 932 | 2.4 |

| Ekiti | 598 | 1.5 |

| Enugu | 944 | 2.4 |

| Gombe | 648 | 1.7 |

| Imo | 934 | 2.4 |

| Jigawa | 1064 | 2.7 |

| Kaduna | 1564 | 4.0 |

| Kano | 2592 | 6.7 |

| Katsina | 1608 | 4.1 |

| Kebbi | 897 | 2.3 |

| Kogi | 841 | 2.2 |

| Kwara | 620 | 1.6 |

| Lagos | 2824 | 7.3 |

| Nasarawa | 546 | 1.4 |

| Niger | 1217 | 3.1 |

| Ogun | 1194 | 3.1 |

| Ondo | 1032 | 2.7 |

| Osun | 828 | 2.1 |

| Oyo | 1428 | 3.7 |

| Plateau | 850 | 2.2 |

| Rivers | 1521 | 3.9 |

| Sokoto | 1094 | 2.8 |

| Taraba | 626 | 1.6 |

| Yobe | 574 | 1.5 |

| Zamfara | 923 | 2.4 |

| FCT | 636 | 1.6 |

| Variables | Discrimination and harassment | ||

| Yes [ n (%)] | No [ n (%)] | Χ2 value (p-value) | |

| Individual-level factors | |||

| Age | 39.047 (< 0.001) | ||

| 15-24 | 2970 (20.0%) | 11821 (80.0%) | |

| 25-34 | 2178 (19.4%) | 9063 (80.6%) | |

| 35-49 | 2173 (17.2%) | 10466 (82.8%) | |

| Education | 63.615 (< 0.001) | ||

| None | 2189 (21.3%) | 8106 (78.7%) | |

| Primary | 938 (17.8%) | 4336 (82.2%) | |

| Junior secondary | 613 (18.1%) | 2770 (81.9%) | |

| Senior secondary | 2649 (18.8%) | 11447 (81.2%) | |

| Higher/tertiary | 929 (16.5%) | 4689 (83.5%) | |

| Wealth index | 95.048 (<0.001) | ||

| Poorest | 1347 (19.6%) | 5516 (80.4%) | |

| Second | 1558 (21.5%) | 5676 (78.5%) | |

| Middle | 1491 (19.7%) | 6065 (80.3%) | |

| Fourth | 1541 (18.7) | 6702 (81.3%) | |

| Richest | 1383 (15.8%) | 7391 (84.2%) | |

| Marital/union status of woman | 32.422 (< 0.001) | ||

| Currently married/in union | 4303 (18.0%) | 19537 (82.0%) | |

| Formerly married/in union | 428 (20.9%) | 1621 (79.1%) | |

| Never married/in union | 2588 (20.3%) | 10170 (79.7%) | |

| Ethnicity of household head | 509.697 (< 0.001) | ||

| Hausa | 2158 (21.8%) | 7728 (78.2%) | |

| Igbo | 1177 (20.0%) | 4713 (80.0%) | |

| Yoruba | 667 (9.9%) | 6063 (90.1%) | |

| Kanuri | 139 (18.6%) | 609 (81.4%) | |

| Ijaw | 144 (21.9%) | 514 (78.1%) | |

| Tiv | 174 (18.9%) | 748 (81.1%) | |

| Ibibio | 157 (19.3%) | 657 (80.7%) | |

| Edo | 223 (31.9%) | 477 (68.1%) | |

| Other | 2003 (20.4%) | 7800 (79.6%) | |

| Fulani | 477 (18.9%) | 2042 (81.1%) | |

| Feeling safe at home alone after dark | 956.160 (< 0.001) | ||

| Very safe | 1649 (15.3%) | 9121 | |

| Safe | 3242 (16.6%) | 16267 (83.4%) | |

| Unsafe | 1724 (28.1%) | 4412 (71.9%) | |

| Very unsafe | 523 (43.0%) | 693 (57.0%) | |

| Never alone after dark | 183 (17.7%) | 852 (82.3%) | |

| Ever circumcised | 20.146 (< 0.001) | ||

| Yes | 1019 (17.4%) | 4826 (82.6%) | |

| No | 3183 (20.2%) | 12612 (79.8%) | |

| Able to get pregnant | 9.138 (0.003) | ||

| Yes | 4152 (18.0%) | 18856 (82.0%) | |

| No | 611 (20.3%) | 2397 (79.7%) | |

| Estimation of overall happiness | 545.138 (< 0.001) | ||

| Very happy | 2496 (15.2%) | 13946 (84.8%) | |

| Somewhat happy | 2652 (18.7%) | 11528 (81.3%) | |

| Neither happy nor unhappy | 1318 (25.1%) | 3937 (74.9%) | |

| Somewhat unhappy | 576 (30.1%) | 1336 (69.9%) | |

| Very unhappy | 274 (33.1%) | 553 (66.9%) | |

| Community-level factors | |||

| Area | 120.673 (< 0.001) | ||

| Urban | 2927 (16.5%) | 14761 (83.5%) | |

| Rural | 4394 (20.9%) | 16589 (79.1%) | |

| Region | 1512.709 (< 0.001) | ||

| Abia | 156 (22.0%) | 552 (78.0%) | |

| Adamawa | 123 (13.9%) | 762 (86.1%) | |

| Akwa Ibom | 148 (16.7%) | 737 (83.3%) | |

| Anambra | 248 (21.8%) | 892 (78.2%) | |

| Bauchi | 341 (25.3%) | 1009 (74.7%) | |

| Bayelsa | 133 (28.8%) | 329 (71.2%) | |

| Benue | 182 (15.8%) | 967 (84.2%) | |

| Borno | 208 (20.3%) | 817 (79.7%) | |

| Cross River | 191 (23.1%) | 636 (76.9%) | |

| Delta | 237 (22.9%) | 799 (77.1%) | |

| Ebonyi | 114 (16.7%) | 570 (83.3%) | |

| Edo | 315 (33.8%) | 616 (66.2%) | |

| Ekiti | 55 (9.2%) | 544 (90.8%) | |

| Enugu | 209 (22.1%) | 735 (77.9%) | |

| Gombe | 60 (9.3%) | 588 (90.7%) | |

| Imo | 185 (19.8%) | 748 (80.2%) | |

| Jigawa | 174 (16.4%) | 890 (83.6%) | |

| Kaduna | 404 (25.8%) | 1160 (74.2%) | |

| Kano | 379 (23.6%) | 1229 (76.4%) | |

| Katsina | 188 (21.0%) | 709 (79.0%) | |

| Kebbi | 138 (16.4%) | 701 (83.6%) | |

| Kogi | 74 (11.9%) | 546 (88.1%) | |

| Kwara | 276 (9.8%) | 2548 (90.2%) | |

| Lagos | 146 (26.7%) | 400 (73.3%) | |

| Nasarawa | 268 (22.1%) | 946 (77.9%) | |

| Niger | 83 (7.0%) | 1111 (93.0%) | |

| Ogun | 47 (4.6%) | 980 (95.4%) | |

| Ondo | 67 (8.1%) | 761 (91.9%) | |

| Osun | 143 (10.0%) | 1285 (90.0%) | |

| Oyo | 184 (21.7%) | 665 (78.3%) | |

| Plateau | 417 (27.4%) | 1104 (72.6%) | |

| Rivers | 193 (17.6%) | 901 (82.4%) | |

| Sokoto | 95 (15.2%) | 529 (84.8%) | |

| Taraba | 120 (20.9%) | 453 (79.1%) | |

| Yobe | 416 (45.1%) | 506 (54.9%) | |

| Zamfara | 136 (21.4%) | 500 (78.6%) | |

| FCT | 467 (18.0%) | 2125 (82.0%) | |

| Variables (with reference) | Odd ratio (OR) | 95% C.I. for OR | Sig. | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Individual-level factors | ||||

| Age (ref: 35-49 years old) | ||||

| 15-24 | 1.270 | 1.095 | 1.473 | 0.002 |

| 25-34 | 1.331 | 1.180 | 1.502 | <.001 |

| Education (ref: None) | ||||

| Primary | 0.825 | 0.687 | 0.990 | 0.038 |

| Junior secondary | 0.692 | 0.557 | 0.860 | 0.001 |

| Senior secondary | 0.753 | 0.633 | 0.897 | 0.001 |

| Higher/tertiary | 0.686 | 0.560 | 0.842 | <.001 |

| Wealth index (ref: Poorest) | ||||

| Second | 0.961 | 0.804 | 1.149 | 0.665 |

| Middle | 0.941 | 0.782 | 1.132 | 0.521 |

| Fourth | 0.950 | 0.777 | 1.162 | 0.616 |

| Richest | 0.943 | 0.756 | 1.176 | 0.602 |

| Marital/union status of woman (ref: Currently married/in union) | ||||

| Formerly married/in union | 0.998 | 0.828 | 1.203 | 0.985 |

| Never married/in union | 1.367 | 1.196 | 1.562 | <.001 |

| Ethnicity of household head (ref: Fulani) | ||||

| Hausa | 1.251 | 0.972 | 1.610 | 0.082 |

| Igbo | 1.390 | 0.976 | 1.981 | 0.068 |

| Yoruba | 1.477 | 1.035 | 2.109 | 0.032 |

| Kanuri | 0.523 | 0.331 | 0.826 | 0.005 |

| Ijaw | 0.982 | 0.620 | 1.555 | 0.937 |

| Tiv | 1.611 | 0.959 | 2.707 | 0.072 |

| Ibibio | 1.229 | 0.779 | 1.938 | 0.375 |

| Edo | 2.336 | 1.501 | 3.637 | <.001 |

| Other ethnicity | 1.335 | 1.006 | 1.772 | 0.045 |

| Feeling safe at home alone after dark (ref: Very safe) | ||||

| Safe | 0.959 | 0.856 | 1.074 | 0.467 |

| Unsafe | 1.739 | 1.496 | 2.021 | <.001 |

| Very unsafe | 2.120 | 1.554 | 2.891 | <.001 |

| Never alone after dark | 0.988 | 0.698 | 1.399 | 0.946 |

| Ever circumcised (ref: Yes) | ||||

| No | 0.949 | 0.843 | 1.068 | 0.385 |

| Able to get pregnant (ref: Yes) | ||||

| No | 1.202 | 1.040 | 1.388 | 0.013 |

| Estimation of overall happiness (ref: Very happy) | ||||

| Somewhat happy | 1.422 | 1.277 | 1.583 | <.001 |

| Neither happy nor unhappy | 1.799 | 1.561 | 2.074 | <.001 |

| Somewhat unhappy | 1.847 | 1.513 | 2.256 | <.001 |

| Very unhappy | 3.101 | 2.393 | 4.018 | <.001 |

| Community-level factors | ||||

| Area (ref: Urban) | ||||

| Rural | 1.140 | 1.006 | 1.292 | 0.040 |

| Region (ref: Kano) | ||||

| Abia | 0.745 | 0.481 | 1.154 | 0.188 |

| Adamawa | 0.843 | 0.551 | 1.289 | 0.431 |

| Akwa Ibom | 0.742 | 0.476 | 1.158 | 0.188 |

| Anambra | 1.400 | 0.927 | 2.115 | 0.109 |

| Bauchi | 1.350 | 0.976 | 1.868 | 0.070 |

| Bayelsa | 1.466 | 0.910 | 2.362 | 0.116 |

| Benue | 0.648 | 0.404 | 1.040 | 0.072 |

| Borno | 1.005 | 0.688 | 1.468 | 0.979 |

| Cross River | 0.916 | 0.626 | 1.339 | 0.649 |

| Delta | 1.193 | 0.845 | 1.684 | 0.316 |

| Ebonyi | 0.668 | 0.427 | 1.046 | 0.078 |

| Edo | 1.185 | 0.786 | 1.788 | 0.417 |

| Ekiti | 0.362 | 0.215 | 0.609 | <.001 |

| Enugu | 0.863 | 0.577 | 1.291 | 0.472 |

| FCT | 0.864 | 0.558 | 1.338 | 0.513 |

| Gombe | 0.450 | 0.263 | 0.770 | 0.004 |

| Imo | 0.943 | 0.621 | 1.430 | 0.781 |

| Jigawa | 0.791 | 0.430 | 1.455 | 0.451 |

| Kaduna | 0.977 | 0.720 | 1.324 | 0.880 |

| Katsina | 1.518 | 1.071 | 2.151 | 0.019 |

| Kebbi | 1.128 | 0.696 | 1.826 | 0.625 |

| Kogi | 0.507 | 0.290 | 0.886 | 0.017 |

| Kwara | 0.450 | 0.279 | 0.726 | 0.001 |

| Lagos | 0.505 | 0.349 | 0.730 | <.001 |

| Nasarawa | 0.851 | 0.558 | 1.300 | 0.456 |

| Niger | 1.080 | 0.746 | 1.563 | 0.684 |

| Ogun | 0.300 | 0.189 | 0.476 | <.001 |

| Ondo | 0.176 | 0.104 | 0.298 | <.001 |

| Osun | 0.335 | 0.213 | 0.528 | <.001 |

| Oyo | 0.492 | 0.321 | 0.753 | 0.001 |

| Plateau | 1.123 | 0.690 | 1.830 | 0.641 |

| Rivers | 1.318 | 0.947 | 1.833 | 0.102 |

| Sokoto | 0.628 | 0.344 | 1.144 | 0.129 |

| Taraba | 0.418 | 0.230 | 0.758 | 0.004 |

| Yobe | 0.994 | 0.599 | 1.647 | 0.980 |

| Zamfara | 5.045 | 3.072 | 8.288 | <.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).